| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Latin America and the Caribbean

Chapter 6: Contemporary Latin America, Part IV

1959 to 2014

This chapter is divided into seven parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| One More Overview | |

| Cuba: The Revolution Continues | |

| Venezuela's Democratic Interlude | |

| Brazil: The Death of the Middle Republic | |

| Weak Radicals and the Argentine Revolution | |

| Colombia: The National Front |

Part II

| Che! | |

| Democracy Breaks Down in Chile | |

| Peru: The Revolution from Above | |

| Mexico: The PRI Corporate State | |

| Meet the Duvaliers | |

| Honduras Goes From Military to Civilian Rule | |

| Ecuador: From Yellow Gold to Black Gold | |

| Tupamaros and Tyrants | |

| The Somoza Dynasty, Act Two |

Part III

| Paraguay: The Stronato | |

| Brazil: The Military Republic | |

| Bolivia: The Banzerato | |

| Red Star In the Caribbean | |

| The Perón Sequel and the "Dirty War" | |

| Panama: The Canal Becomes Truly Panamanian | |

| The Dominican Republic: The Balaguer Era | |

| The Guianas/Guyanas: South America’s Neglected Corner | |

Part IV

Part V

| The Switzerland of Central America | |

| Nicaragua: The Contra War | |

| Ecuador After the Juntas | |

| Chasing Noriega | |

| Argentina’s New Democracy | |

| Hugo's Night in the Museum | |

| Democracy Comes to Bolivia (at Last) | |

| Haiti: Beggar of the Americas | |

| Peru: The Fujimori Decade |

Part VI

| Brazil: The New Republic | |

| Cuba's "Special Period" | |

| Chileans Put Their Past Behind Them | |

| Colombia’s Fifty-Year War | |

| Uruguay Veers from the Right to the Left | |

| Daniel Ortega Returns | |

| Ecuador: Dollarization and a Lurch to the Left | |

| The Chavez Administration, Both Comedy and Tragedy |

Part VII

| Argentina: The New Millennium Crisis, and the Kirchner Partnership | |

| Guatemala Since the Peace Accords | |

| Can Paraguay Kick the Dictator Habit? | |

| Honduras: The Zelaya Affair | |

| Peru in the Twenty-First Century | |

| Bolivia: The Evo Morales Era | |

| The Mexican Drug War | |

| Puerto Rico: The Future 51st State? | |

| Conclusion |

The Salvadoran Civil War

The last time this narrative looked at El Salvador, it was a typical Central American "Banana Republic" (see Chapter 5, footnote #1 for a definition of that term), and not changing very fast. Since 1931 the military had been in charge, though the last two heads of state in the 1950s, Óscar Osorio and José María Lemus, belonged to a political party that called itself "democratic" (the Revolutionary Party of Democratic Unification). After Lemus was overthrown in a bloodless coup (October 1960), two juntas and one provisional government quickly followed. Then in mid-1962 the military organized a new party, the Party of National Conciliation (more recently called the National Coalition Party). The next four presidents were officers who belonged to that party: Julio Adalberto Rivera Carballo (1962-67), Fidel Sánchez Hernández (1967-72), Arturo Armando Molina (1972-77), and Carlos Humberto Romero (1977-79).(79)

One interesting event from this period was a short war with Honduras (July 14-18, 1969). As the most densely populated country in Central America, El Salvador was running out of living space, so its excess people had been sneaking across the border and settling on Honduran land. By 1969 there were 300,000 Salvadorans living illegally in Honduras, making up one fifth of that country’s population. Relations between the two countries got so bad that when their soccer teams played each other, in one of the qualifying rounds for the 1970 World Cup, fights broke out between the fans. On the day that El Salvador won the third and last game, it accused Honduras of crimes against Salvadorans, and broke diplomatic relations, giving this conflict its name of the "Football War." Two weeks later, the Salvadoran army and air force invaded Honduras. After four days, however, the Salvadoran offensive petered out, the Honduran air force gained control of the air, and El Salvador agreed to a cease-fire introduced by an emergency session of the OAS. In August El Salvador began withdrawing its forces, but the issues which caused the fight were never addressed, so the two sides refused to sign a peace treaty until 1992.(80)

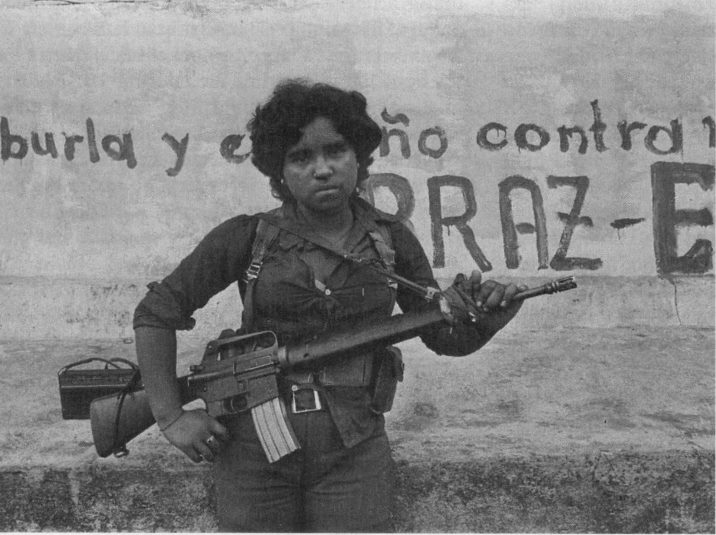

The economy was still dependent on one crop, coffee, so El Salvador’s fortunes were greatly affected by changes in coffee prices. Most of the people were undernourished, because the wealthy landowners planted so many acres with coffee trees that there wasn’t much land left for growing foodstuffs. Consequently the poor state of the economy caused the regime to unravel in the 1970s. Events surrounding the 1972 election (see footnote #79) convinced many that the military would never allow a peaceful transition to democracy, and that armed insurrection was the only way to achieve change. Leftist guerrilla activity increased steadily after that. With the overthrow of the Somoza regime in neighboring Nicaragua, the Sandinistas began providing military aid to five Salvadoran guerrilla groups. On the other side of the political aisle, rightist vigilante death squads entered the conflict, kidnapping and killing those they did not like.

On October 15, 1979, some reform-minded officers and civilians got together to overthrow General Carlos Humberto Romero. However, both the extreme right and the extreme left found reasons to disagree with the new junta. While the United States decided to support the government (as in other parts or Latin America, Uncle Sam tended to favor the side that stood for law and order), Cuba and other Communist nations encouraged the guerrillas to merge into one movement, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). Finally, the poorly trained Salvadoran Armed Forces (ESAF) also engaged in torture and indiscriminate killings.

On March 24, 1980, Óscar A Romero, the country’s outspoken archbishop, was assassinated while saying mass in a cancer hospital. One of the rightist death squads was probably responsible; they detested clergy who talked about reform and social justice (that sounded too much like Liberation Theology). Take your pick; either the 1979 coup or the archbishop’s murder marks the beginning of the all-out civil war in El Salvador.

Another atrocity that made international headlines in 1980 was the rape and murder of four nuns from the Maryknoll Mission, a US-based Catholic order known for doing humanitarian work. President Jimmy Carter cut off military aid to the Salvadoran government, but when Ronald Reagan succeeded him a few months later, he saw the situation differently. The Reagan administration noted that the Salvadoran military was losing against the Sandinista-backed guerrillas, and decided it was more important to keep El Salvador from becoming another Nicaragua. During the Reagan years, US aid generously flowed to the military, reaching as high as $500 million a year. Unfortunately the military did not get the upper hand against the guerrillas, though it destroyed villages in an effort to flush them out (e.g., more than 750 women and children were killed in the 1981 El Mozote massacre).

José Napoleón Duarte, the Christian Democratic Party leader, joined the junta in March 1980, and became the acting president in November. While he was in charge, the junta introduced a land reform program, nationalized the banks and the marketing of coffee and sugar, and allowed political parties to act with more freedom than they had in the past. Elections were held in March 1982, and the newly elected assembly picked Alvaro Magana to be the next president. Then a new constitution was written in the following year, which promised to enforce human rights more strongly, and added labor rights laws.

All this progress failed to satisfy the FMLN, which continued its guerrilla war against the relatively moderate government. Rightists, however, gave the government a chance, and formed a party called the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) to compete politically. In the 1984 election, Duarte beat ARENA’s founder, Roberto D’Aubuisson, to become president again; he was El Salvador’s first freely elected president in more than fifty years. The next time elections were held, in 1989, the results were completely reversed; the ARENA candidate, a wealthy businessman named Alfedo Cristiani, was the winner. This marked the first time in El Salvador’s history that power passed peacefully between two freely elected civilian leaders from different parties. Nevertheless, the guerrilla campaign against the government continued all through this period; to suffocate the economy, the FMLN blew up bridges, cut power lines, destroyed coffee crops and killed livestock. In retaliation, the death squads targeted trade unionists and others who supported the agrarian reform proposed by the Christian Democrats.

Though the death squads were on Cristiani’s side, he could see that the war was unlikely to end in a right-wing victory, so as soon as he became president, he called for peace talks with the guerrillas. Negotiations began in September 1989, but ended abruptly when the FMLN launched a bloody, nationwide offensive in November. New talks commenced in April 1990 when the United Nations, at the request of all Central American presidents, got involved as the mediator between the factions. It took nearly a year and a half to reach an agreement, and then it was to accelerate the negotiating sessions, by having them at UN headquarters in New York City.

Finally on January 16, 1992, the government and the guerrillas signed the Chapultepec Peace Accords in Mexico City. The cease-fire that followed lasted for the rest of the year without being broken, allowing all sides to declare that the civil war was over. The FMLN demobilized its military force and transformed itself into an opposition party, while the government agreed to various reforms. The reforms mainly involved land distribution (which actually worked), abolishing most of the police forces, demobilizing three-fourths of the armed forces, purging those officers accused of human rights violations and corruption, and teaching the remaining soldiers to act professional and stay out of politics.

The war had killed an estimated 75,000 people, and 300,000 fled abroad to escape it. Not all of them returned after the war’s end; more than 2 million Salvadorans live abroad today, and the amount they send home to their relatives every year is estimated at over $2 billion. Like the Dominican Republic, El Salvador’s largest source of income is now remittances from its citizens abroad. There is some concern that this is hurting the country’s work ethic; because work on the farms is so hard and pays so little, today’s Salvadorans may feel that it is better to receive a check, even a small one, from a family member in a richer country. Recently El Salvador had to hire temporary workers from Honduras and Nicaragua to harvest the coffee and sugar cane crops, though quite a few Salvadorans are unemployed or underemployed.

After Cristiani, the next three presidents all came from the ARENA party: Armando Calderón Sol (1994-99), Francisco Guillermo Flores Perez (1999-2004), and Elias Antonio Saca González (2004-09). The FMLN were successful in getting their candidates elected on the local and presidential levels (e.g., they first won San Salvador’s mayoral election in 1997), but they weren’t as well organized on the national level; hence the ARENA victories. The 2004 election also saw the elimination of the Christian Democrats and two minor parties, because they failed to get the 3% vote required by electoral law to maintain their registration as parties.

By the time of the 2009 presidential election, the FMLN got its act together; its candidate, a former journalist named Carlos Mauricio Funes Cartagena, was elected president. Then in 2014 the FMLN won again, electing the vice president, Salvador Sánchez Cerén, to the top spot. This means the transition from dictatorship to democracy in El Salvador is complete; never before has the country had a leftist government, and it is hard to think of a guerrilla movement anywhere that made the transition from armed fighters to peaceful politicians as successfully as the FMLN has done. In the future, observers will be watching to see if El Salvador continues to alternate between conservative or liberal parties, or if it will get stuck with one party, as is the case with some other Latin American nations (e.g., the PRI in Mexico, or the Colorados in Paraguay).

Belize: A Nation Under Construction

Belize is the youngest nation on the American mainland (see footnote #74), and in all of the Americas, only two tiny Caribbean island nations (Antigua & Barbuda and St. Kitts & Nevis) are younger. Independence from Great Britain came because Belizean nationalists showed more patience than resistance. The British were ready to grant independence to what they called British Honduras as early as 1961, but two obstacles got in the way.

The first was Hurricane Hattie, which whacked Belize City with 140 MPH winds on October 31, 1961. It wasn’t the worst hurricane to strike Belize (a 1931 storm killed 2,500 people), thanks to advance warnings that allowed the city’s residents to escape. Even so, Hattie killed 307 and did $60 million in damage. Because most of the buildings and houses in the capital were made of wood, 75 percent of them were destroyed. George Cadle Price, a co-founder of the People’s United Party (PUP), had been elected just a month earlier, as the first prime minister; you could say his first test at handling a crisis came very quickly. While he got aid from London to rebuild Belize City, he and the new government decided that in the future the capital should not be on the coast, to make it safe from other hurricanes. The site chosen for the new capital was fifty-one miles inland, and named Belmopan because it was at the junction of the Mopan and Belize Rivers. With additional funding from London, construction began in 1967, and the first neighborhood was completed in 1970. Still, some parts of the government did not move from Belize City to Belmopan until 1984, and some parts of the new city were not finished until 2000.(81)

The other obstacle was Guatemala. We saw in Chapter 4 that Guatemala felt it had inherited Spain’s claim on the British enclave to the east, and though it signed a treaty establishing the Guatemala-British Honduras frontier in 1859, successive Guatemalan governments never saw that as the last word on the matter. When the Guatemalans wanted to irritate others, they would publish maps showing Belize as a Guatemalan province. The British understandably said no to Guatemalan demands, because Guatemala’s caudillos weren’t doing a good job managing the territory they already had, and George Price rejected any proposal that would make British Honduras an "associated state" of Guatemala; the only kind of association he would accept is membership in the British Commonwealth of Nations. Negotiations over the matter only succeeded in creating a demilitarized zone, within one mile of the border on each side. However, Guatemala’s leaders were never confident enough to move in and take the territory, the way Nicaragua had done with the Mosquito Coast in 1894.

By 1964, British Honduras was almost completely self-governing; Britain only retained control over defense, foreign affairs and internal security. In 1973 the territory’s name was changed from the colonial-sounding British Honduras, to the more popular name of Belize. Guatemala insisted that its territorial claim be resolved, now that it looked like the British would really leave. Because Belize has always been underpopulated, it could only support a force of 700 troops -- hardly enough to defend against a Guatemalan invasion -- so Britain decided it would have to keep a garrison stationed there after independence.(82)

The dispute was settled when both sides looked for international support. Between 1975 and 1981, Belizean leaders went to organizations like the United Nations, the British Commonwealth, the Organization of American States, and the Nonaligned Movement, pleading for them to support the Belize’s right to exist as a sovereign state. They all pledged their support, and so did several individual nations (e.g. Mexico, Panama, Cuba, and Nicaragua). Finding no one else on its side, Guatemala had to back down. With the danger to Belize fading, the UN passed a resolution in November 1980, calling for the independence of Belize, and Britain granted it on September 21, 1981.

So what did Belize have, now that it was on its own? A tract of land the size of Massachusetts, flat in the north with some low mountains in the south. Most of the terrain was a tropical rainforest, and we already noted, it was underpopulated. Since the first Europeans arrived, Belize had made a living by exporting one commodity: first dyewood, then hardwoods, and then sugar. A slump in sugar prices during the 1980s forced the country to try other ways of making money, like growing more bananas and citrus fruits.

However, the biggest success came not from exports, but by encouraging an import: tourists. The local rainforest, the Maya ruins, and the offshore coral reefs made Belize an ideal place for ecotourism. The number of tourists who came rose from 140,000 in 1988 to 250,000 in 2006, rivaling the number of permanent residents. By the end of the twentieth century, tourism had replaced commodity exports as Belize’s most important source of income, and more than 40 percent of the country had been turned into national parks, or received some other form of protection. In addition, low taxes, a low cost of living, and use of the English language made Belize an attractive place for North Americans to retire, and a tax shelter for investors. Nevertheless, the country still has a major problem with high unemployment, citizens involved in the Latin American drug trade, and street crime in Belize City.

So far Belize has had four prime ministers, and the government has regularly alternated between the PUP and the United Democratic Party (UDP), a center-right political party founded in 1973. At the time of independence, George Price had been in charge for twenty years, but he and the PUP were turned out by the first post-independence election, in 1984. Sir Manuel Esquivel became prime minister, and ruled until the 1989 elections, when Price returned to power. During Price’s second administration, Guatemala’s president formally recognized Belize as an independent nation (1992).(83) Because of this, Britain withdrew most of its troops by 1994; the only British soldiers in Belize today are there to train Belizean troops.

With the 1993 election, the two parties switched places again; Esquivel and the UDP were now at the helm for the second time. Then in 1998, the PUP won by a landslide. Price had retired by this time, so Said Musa, the son of a Palestinian immigrant, became the country’s third prime minister. Musa promised that his priority would be to improve conditions in the south, which is less developed and less accessible than the north.

Musa was re-elected in 2003, but by now the PUP was vulnerable. The party was accused of various kinds of corruption: missing pension funds, the selling of public lands -- and bribery. Accusers declared that PUP never met a greased palm it wouldn’t shake, while supporters said the same was true of politicians from other parties. Consequently the 2008 election was noisier than previous one, and when the PUP went down in defeat, Musa announced his retirement. Dean Oliver Barrow of the UDP has been prime minister since 2008. Incidentally, he is also the first black prime minister; his predecessors were all white.

Currently Belize faces economic and demographic challenges. Because of a shortage of jobs at home, one third of Belizeans, especially Creoles, now live and work abroad. Meanwhile, refugees from Guatemala and Honduras continue to move in, seeking to escape poverty. Because of that, census data since 1991 shows that Mestizos have become the largest ethnic group, so while English may still be the official language, there are probably more Spanish speakers than English speakers. This means that in the twenty-first century, Belize will probably look more like the rest of Central America and less like the English-speaking islands of the Caribbean. And the success of the previously mentioned tourism industry is a sign of a promising future for a land that used to be a pirate haven and a forgotten, jungle-covered coast.

The Guatemalan Civil War

When we looked at Guatemala in the previous chapter, it had established a democracy in 1944, only to see it overthrown by a CIA-backed coup ten years later, when the government became pro-Communist. That solved Washington’s problem -- a Communist threat in Central America -- but for Guatemala it was the beginning of a time of troubles that lasted a full forty-two years. The leader of the coup, Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, became president afterwards, and ruled for three years. Castillo was in turn assassinated by a palace guard, and eight months later, General Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes was elected as his replacement (1958).

Ydígoras was no barrel of laughs. A senior CIA chief said he is "known to be a moody, almost schizophrenic individual" who "regularly disregards the advice of his Cabinet and other close associates." A group of junior military officers found him too autocratic and too pro-American, and launched a revolt in 1960. It failed, so the officers went into hiding, and called upon the Castro regime in Cuba for help. They became the nucleus of four left-wing guerrilla movements that would fight the government in a thirty-six-year civil war (1960-96): the Guerrilla Army of the Poor (EGP), the Revolutionary Organization of Armed People (ORPA), the Rebel Armed Forces (FAR), and the Guatemalan Labor Party (PGT). In 1982 the four groups merged into one, the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (URNG).

On the other side of the political aisle, the guerrillas were matched by extreme right-wing groups of self-appointed vigilantes, with names like the Secret Anti-Communist Army (ESA), the White Hand, "National Organized Action Movement," "Eye for an Eye," and "Jaguar of Justice." Whatever these death squads were called, they tortured and murdered students, professionals, and peasants suspected of involvement in leftist activities. Because they did the government’s dirty work, they were tolerated and received clandestine military support.

Ydígoras was ousted in a 1963 coup led by his defense minister, Colonel Enrique Peralta Azurdia, because it looked like Juan José Arévalo, the former left-wing president, was going to win the upcoming elections. Peralta held the top spot for three years, and then allowed elections, which were won by another left-of-center civilian, Julio César Méndez Montenegro. He was the country’s only civilian president between 1954 and 1986.

Méndez was allowed to serve a complete four-year term (1966-70), but as a military puppet. During this time the civil war really took off, starting with the army launching a counterinsurgency campaign that broke up the guerrilla movements in the countryside. The guerrillas responded by making Guatemala City the target for most of their attacks, carrying out a steady string of assassinations, including the US Ambassador, John Gordon Mein(84), and the West German ambassador, Karl von Spreti. After the presidency of Méndez ended, three military governments ruled over the next twelve years (1970-82).(85)

On March 7, 1982, General Angel Anibal Guevara, the hand-picked candidate of outgoing President and General Romeo Lucas Garcia, won a presidential election that was denounced as fraudulent by both conservatives and liberals. Two weeks later, another group of junior army officers staged a coup to prevent him from taking office. They set up a three-man junta, led by a retired general, José Efraín Ríos Montt, to negotiate the departure of Lucas and Guevara. This junta annulled the 1965 constitution, dissolved Congress, and suspended political parties and elections; in June Ríos Montt dismissed his associates and began to rule alone, as "President of the Republic."

Ríos Montt is the most controversial figure in recent Guatemalan history, in part because he is a born-again Evangelical Protestant. In 1978 he left the Catholic Church to join the Church of the Word, a California-based Pentecostal group that had been active in Guatemala since the 1976 earthquake (see the previous footnote), and was an ordained lay pastor by the time of the 1982 coup.(86) In his inaugural address, he declared he had become president because of the will of God.(87) Consequently he could count TV evangelists like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson among his friends. However, he also showed that a dictator who read the Good Book was still a dictator.

Guerrillas and leftists denounced the new head of state, calling him "Ayatollah Ríos Montt." The government used a combination of military actions and economic reforms against the guerrillas, in a program Ríos Montt called frijoles y fusiles (beans and rifles). Much of the rural population was conscripted into civilian defense patrols (PACs), working alongside the army. In theory participation was voluntary, but caught in the crossfire, most peasants found that their only choices to join the PACs or the guerrillas. Because of the polarization, they were damned if they supported one side and damned if they supported the other. Over the following year, the army and the PACs succeeded in taking back nearly all rebel-held territory, reducing the guerrillas to hit-and-run raids. Guatemalans called this offensive la escoba (the broom), because it made a clean sweep of the country.

Success came at a dreadful cost; estimates of the number killed ranged from 15,000 to 70,000, while 100,000 became refugees. Those fighting on the government’s side usually did not know who the rebels were, but they knew they received their support from poor, rural, indigenous villages, so the government razed 400 Indian villages as part of its strategy. On July 18, 1982, The New York Times quoted Ríos Montt saying as much to an Indian audience: "If you are with us, we'll feed you; if not, we'll kill you." After his presidency, when Ríos Montt was on trial for war crimes, he testified that he did not know who was responsible for the civilian deaths. Whether or not this is true, the period when Ríos Montt was in charge was the most violent phase of the civil war.(88)

On August 8, 1983, Ríos Montt was removed in a coup led by his Minister of Defense, General Oscar Humberto Mejia Victores. Mejia explained that "religious fanatics" were abusing their positions in the government; he claimed "official corruption" was a problem, too. Ríos Montt went on to found a political party, the Guatemalan Republican Front (FRG), and was eventually elected President of Congress. More than one country wanted to try him for leading a genocidal war during his presidency, but he was immune from prosecution while running Congress. His accusers finally got their chance in 2013, when he was charged with ordering the deaths of at least 1,771 Ixil Maya, put on trial, convicted, and sentenced to 80 years in prison. Ríos Montt appealed the conviction, and a new trial is scheduled to begin in January 2015.

At first human rights abuses continued under Mejia, an estimated 100 murders and 40 abductions a month. The survivors of la escoba were relocated to newly build model villages called polos de desarollo (poles of development), which like the "new villages" built during the Malayan Emergency of the 1950s, had army camps nearby to keep the guerrillas out. Soon the Reagan administration decided it couldn’t take the bloodshed anymore, and Washington cut off military aid to Guatemala.

I’m not sure if the aid cutoff decided it for him, but General Mejia committed his presidency to a guided restoration of democracy. In July 1984 a constituent assembly was elected to draft a new constitution. They got their work done at the end of May 1985, and the constitution went into effect immediately. Marco Vinicio Cerezo Arévalo, the candidate of the Christian Democracy Party, won the presidential election that followed with almost 70% of the vote, and took office on January 14, 1986.

Cerezo announced at the beginning of his presidency that the top two priorities would be ending the civil war and establishing the rule of law. For the first half of his term, things went well; the economy was stable and violence decreased. Some dissatisfied military personnel made two coup attempts in May 1988 and May 1989, but most of the military stayed loyal, allowing the government to survive. However, the news wasn’t so good for the last two years. 1989 and 1990 saw a poor economy, strikes, protest marches, and criticism of the government for not investigating or prosecuting cases of human rights violations. Finally, the government was unable deal with infant mortality, illiteracy, deficient health and social services -- issues which were sure to generate popular discontent. Because of that and the continued violence, when Cerezo’s term ended, many people wondered if any real progress had been made.

The next president, Jorge Serrano Elías, was another Evangelical Christian, like Ríos Montt. He was elected in 1990 after two ballots were held. However, his Solidarity Action Party (MAS) only won 18 of the 116 seats in Congress, forcing him to form a coalition with two larger parties, the Christian Democrats and the National Union of the Center (UCN). As president, he made some tough decisions: replace a number of senior officers; persuade the whole military to accept civilian leadership; negotiate with the URNG guerrillas; and recognize Belize as an independent, sovereign state (a very unpopular move). He also had some success in reducing inflation and ending the recent recession. But then in May the peace talks broke down, and Serrano overstepped his bounds later in the same month; suddenly he dissolved Congress and the Supreme Court, supposedly to fight corruption. This was an illegal move; all of Guatemalan society, the army, and international pressure quickly made their disapproval felt. Seeing everyone against him, Serrano fled the country; he now resides in Panama. Congress subsequently removed Serrano’s vice president, who had assumed the role of acting president, and elected Ramiro de León Carpio, the country’s human rights ombudsman and an outspoken critic of the army’s heavy-handed tactics, as president to complete Serrano’s term.

De León was not a politician and didn’t have a political party, but his record of what he did before becoming president meant he came into office with much good will. However, he did agree with Serrano that corruption in Congress and the Supreme Court was a problem, and ordered every member of those two bodies to resign. There was resistance, of course, until popular pressure and an agreement brokered by the Catholic Church between the president and Congress was approved by popular referendum. Congress stepped down, and a new Congress was elected in August 1994. Meanwhile, de León revived the peace talks, and the government signed agreements with the guerrillas on human rights, the resettlement of displaced persons, historical clarification, and indigenous rights, over the course of 1994 and 1995.

1996 began with general elections for the president, Congress and various local offices. Almost twenty parties competed in the first round of voting, and for the presidential race in the second round, National Advancement Party (PAN) candidate Álvaro Arzú, the former mayor of Guatemala City, beat Alfonso Portillo of the Guatemalan Republican Front (FRG), by a margin of just over 2% of the vote. It was Arzú’s administration that concluded the peace talks, and on December 29, 1996, the government and the URNG signed "A Firm and Lasting Peace Agreement" at the National Palace in Guatemala City, ending the civil war at last.

It is now estimated that during the thirty-six-year civil war, 200,000 Guatemalans were killed, a million lost their homes, and unknown thousands just disappeared. Left-wing guerrillas and right-wing death squads were responsible for some of the summary executions, forced disappearances, and torture of noncombatants, but the vast majority of human rights violations were carried out by the military and their PACs. What’s more, most of the victims were Maya civilians, leading to the accusations of genocide on the government’s part. The investigations of the atrocities were carried out by the Historical Clarification Commission (CEH), a truth and reconciliation commission set up in 1994, and the Archbishop's Office for Human Rights (ODHAG). The CEH estimated that government forces committed 93% of the violations; while ODHAG estimated they committed 80%. Because of all this, the peace accords addressed the resettlement of displaced people, the rights of indigenous tribes and women, health care, education and other basic social services, and the abolition of obligatory military service. Not all of these provisions have been fulfilled yet.

|

|

The most recent conventional war involving a Latin American nation (as opposed to all the guerrilla wars covered in this chapter), was the ten-week war in 1982 between Argentina and Britain. They fought over an archipelago in the southernmost part of the Atlantic, what Britain calls the Falkland Islands and Argentina calls las Islas Malvinas; icy, remote South Georgia Island, 800 miles to the southeast, was part of the dispute as well. Because the islands are located between latitudes 51° and 55° S., and no wars have been fought in Antarctica yet, this is the southernmost war in history.(89)

Britain claimed the islands through squatter’s rights -- they had settled and ruled the islands without interruption for nearly a century and a half (see Chapter 3). Argentina’s claim is a bit more complicated; the islands are on the South American continental shelf, and Spain was the last country to rule them before its South American colonies declared independence, so it seemed natural to Argentinians that any South American land that used to belong to the mother country ought to belong to a South American nation.

Argentina brought up the issue of the disputed islands more than once in the mid-twentieth century; usually the result was a round of discussions at an international organization like the United Nations that failed to settle anything. And that was where matters stood until the military took over in Buenos Aires. General Jorge Rafael Videla relinquished power on the fifth anniversary of that coup, in 1981, and was replaced with a junta made up of Army General Leopoldo Galtieri (who became the acting president), Air Force Brigadier General Basilio Lami Dozo, and Admiral Jorge Anaya. Dictators have long known that a foreign war can rally a nation’s population behind its rulers (e.g., Benito Mussolini invaded Ethiopia to get Italians thinking about something besides the Great Depression), and the junta faced worker discontent and a poor state of the economy, so almost immediately they began planning to invade the Falklands. Galtieri and company also thought conquering the disputed islands wouldn’t be very tough, for the following reasons:

- Britain had given away most of its empire since World War II ended, so how badly would it fight to keep the Falklands?

- To reach the Falklands, Britain had a lot farther to go than Argentina did -- almost 8,000 miles.

- The British economy hadn’t been doing very well in the 1970s, either.

- Galtieri got along with the Reagan administration, which led him to believe that the United States would not get involved.(90)

- The rest of Latin America was rooting for Argentina, except for Chile (because of the Beagle Channel dispute).

Phase 1: the Argentine attack.

What the junta didn’t figure into the equation was the determination of the current British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher; she wasn't called the "Iron Lady" for nothing. Instead of rolling over and surrendering, she dispatched a naval task force to retake the islands. It was the biggest concentration of ships, aircraft and men Britain had available, and since it only had two aircraft carriers, it was also the absolute bare minimum force needed to do the job. For example, when the fleet started out, one of the carriers, the HMS Invincible, was the flagship, but because she was barely seaworthy and couldn’t keep up with the other ships, the other carrier, the much older HMS Hermes, took over as flagship before they reached the islands. In addition, no tanks were brought, because it was thought they were unsuitable for the terrain of the Falklands and South Georgia, and Argentina always had more airplanes and men on the scene then Britain did. However, the troops occupying the islands were not Argentina’s best; the junta sent its best troops to the Andes, because it feared Chile might take advantage of the war to attack Argentina. The troops the British ended up facing were poorly trained, hungry, and freezing, because it was now autumn in the southern hemisphere. Thus, Britain showed the world that the British Empire may only be a shadow of its former self, but it still had first-class fighting men.(91)

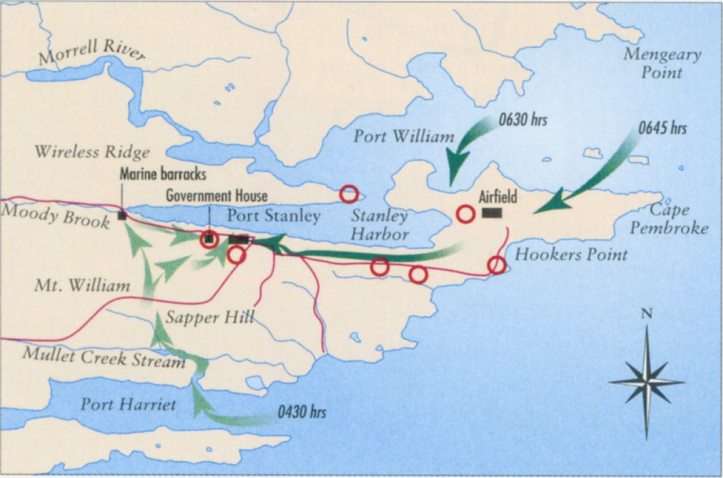

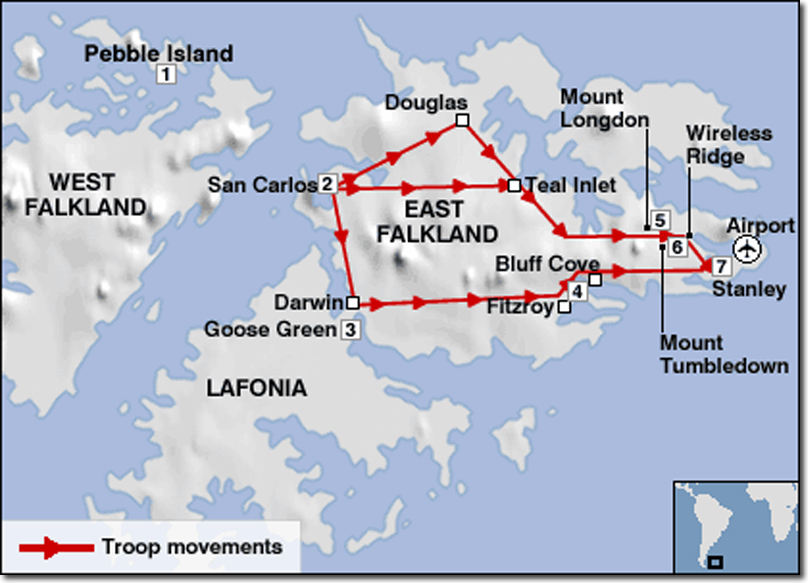

On April 25, part of the task force arrived at South Georgia, and though the weather had gotten very bad, they took back the island in an almost bloodless campaign. The rest of the force spread out around East Falkland, since nearly all of the inhabitants lived there.(92) The first three weeks of May saw air and sea battles, as the British looked for a suitable place to land. In these duels the score was even; the British sank a cruiser, the General Belgrano, and the Argentinians in turn sank two destroyers, the Sheffield and the Coventry.(93)

The ground phase of the war began on May 21, when British forces beat off fierce air attacks and landed at San Carlos Bay, on the west side of East Falkland. Once they secured a bridgehead, they split into three columns and fanned across the island in an eastward direction, toward Port Stanley.

Phase 2: the British counterattack.

One of the columns headed for the nearest Argentine position, Goose Green, located at the island’s narrowest point. However, victory wasn’t a sure thing, and the BBC almost ruined the whole campaign by announcing in a news broadcast that the British Marines were planning to take Goose Green. Naturally the Marine commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Jones, was furious about losing the element of surprise, and threatened to sue the BBC, but the Marines did not have an alternate plan, so they went ahead and attacked Goose Green anyway.

Incredibly, they succeeded. The Argentinians let their guard down; they thought the British would not be stupid enough to attack right where the BBC said they were going to attack, so they expected the Marines to go for a different target. In the battle that followed, seventeen British soldiers were killed, including Lieutenant-Colonel Jones, and forty-seven Argentinian soldiers were killed (May 28). Victory at Goose Green probably decided the rest of the war in Britain’s favor. After that it was just a matter of surrounding Port Stanley and the occupying Argentine army in it. That army’s commander, Mario Menendez, surrendered on June 14, 1982, and it was all over.

Here come the winners. Anybody got a flagpole handy?

Britain’s total victory discredited the Argentine junta so badly that it was compelled to step down and let democracy return to the country in 1983.(94) However, the dispute is by no means resolved, because neither side has conceded any ground on it. In March 2013 a referendum was held on whether the English-speaking Falkland Islanders wanted to remain under British rule, and only three of them voted no. In response, Argentine President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner tweeted, "An English territory more than 12,000 km away [from the U.K.]? The idea is not even worthy of a kindergarten of three-year-olds." A few weeks later, the discovery of major offshore petroleum deposits upped the stakes; now the Islanders can expect a rich future if Argentina will allow Britain to drill. On the Argentine side, the nation still wants the Malvinas as much as ever, though with a leftist civilian government in power, the hope is that they will get the islands through a diplomatic settlement, not another war.(95)

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

The British Empire enjoyed a spectacular run in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when it was known as the "Empire on Which the Sun Never Sets," but today only bits of it remain.(96) As powerful as it was at its peak, the British Empire did not go down fighting like the Assyrian Empire, nor did it suffer a long period of decline like the Roman Empire; the British Empire gave itself away. After the British granted independence to India in 1947, the pressure to quit their other colonies became irresistible. They spent the rest of the 1940s and 50s pulling out of colonies in Asia and Africa, but eventually they would consider turning their New World colonies loose as well.

Before 1962 there were only three independent nations in the Caribbean: Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba. Today there are thirteen.(97) Most of the islands in question haven’t been mentioned in this narrative since Chapter 3, because they were small, lazy colonies, where not much had happened since the days when European merchants, warships and pirates competed to gain control over as much of the region’s sugar production as possible. The problem with letting the islands go was that most of them did not have viable economies. They had few (if any) natural resources, not enough people for a commerce-oriented community like Hong Kong or Singapore, and a serious shortage of land. However, Jamaica has rich bauxite deposits, and enough land for agriculture, so for a while the plan was to create a single state for all of the British-ruled islands. This proposal, called the West Indian Federation, was set up in 1958, and it would have allowed Britain to unload the responsibility for the smaller islands onto the largest one, Jamaica. But it would not do to let Jamaica dominate the Federation, so the Federation capital was placed at Port-of-Spain, on Trinidad. Consequently the Jamaicans did not like the Federation idea, and in 1961 they voted to withdraw from the Federation. One year later the Federation was declared a failure and dissolved.

Next, the British briefly tried a second, smaller federation. Guyana was seen as a possible replacement for Jamaica, but it refused to join the Federation, so this union also failed. Then London decided to grant independence to those islands that had enough people and resources for a fighting chance at prosperity, and keep Britain’s responsibility over the rest.(98) Jamaica was already well on the way to independence; a local lawyer, Norman Manley, founded the People’s National Party (PNP) in 1938, and won universal suffrage for the island in 1944; the island had been self-governing, with Manley as the chief minister, since 1955.(99) Therefore Jamaica went first, becoming independent in 1962. The others were freed in the following order:

- Trinidad & Tobago = 1962

- Barbados = 1966

- Bahamas = 1973

- Grenada = 1974

- Dominica = 1978

- St. Lucia = 1979

- St. Vincent & the Grenadines = 1979

- Antigua & Barbuda = 1981

- St. Kitts & Nevis = 1983

Bermuda, the Bahamas, and Dominica

|

|

|

Bermuda has done a splendid job of promoting itself; it now has a per capita income of $86,000, meaning the typical Bermudan is richer than the typical US citizen. Among independent Caribbean nations, the Bahamas is the most successful; it has a per capita income of $32,000, the third highest for the whole western hemisphere, after the United States and Canada. They did it by taking advantage of their location, just southeast of Florida; the Bahamas replaced Cuba as the nearest resort for tourists from the North American mainland. However, we have seen countries dependent on one product or industry undergo serious economic swings, so the Bahamas only prospers when the United States prospers. As Bahamians put it, "When America sneezes, the Bahamas catches a cold."

Dominica started out under Eugenia Charles, the first female prime minister in Caribbean history (appropriate, since Margaret Thatcher was prime minister of the mother country at this time).

Grenada

Grenada had the most troubled time of any island covered in this section, going through a decade of turbulence following independence. The first prime minister, Sir Eric Gairy, had a reputation for eccentric behavior; the outside world got a sample of it in when he called on the United Nations to set up a unit to investigate UFOs, and suggested proclaiming 1978 "the Year of the UFO." When he learned that a Marxist-Leninist party, the New Jewel Movement, was plotting against him, Gairy sought advice, and training for his police and soldiers, from the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile -- not a good way to win friends and influence people! The New Jewel Movement predictably responded by turning to the Castro regime in Cuba for assistance. In 1979, while Gairy was away from the island, the New Jewel Movement seized Grenada’s radio station, and with the support of the army, the rest of the country. Following the coup (the only coup in any ex-British-ruled territory of the western hemisphere), the Movement’s leader, Maurice Bishop, became the next prime minister, suspended the constitution, and ruled by decree for the next four years.

The new government established close ties with communist countries, especially Cuba and the Soviet Union. Cuban doctors, teachers and technicians arrived to build up Grenada’s infrastructure. The United States disapproved, and grew especially concerned about a 10,000-foot runway the Cubans were building; the Reagan administration believed it would not be used for airliners, as Maurice Bishop asserted, but for large cargo transport airplanes from the Soviet air force. Still, despite all the assistance, Bishop tried to keep Grenada a nonaligned country. The United States feared Grenada was turning into another Cuba or Nicaragua, and soon got a reason to do something about it.

In October 1983 some hardline Marxists in the army decided that Bishop wasn’t radical enough to lead a revolution, and arrested him. Over the next few days, when Bishop tried to regain power, soldiers executed him and seven associates, including cabinet members. The army then announced martial law and a four-day curfew, under which anyone leaving home without their approval could be shot on sight. The governor general of Grenada and the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (see footnote #98) both asked for US intervention, and nine days later a joint US-Caribbean force landed on Grenada. The invasion, called "Operation Urgent Fury," was carried out with minimal bloodshed; U.S. citizens were evacuated, and order was restored. The United Nations and several foreign governments condemned the action, though the pre-1979 constitution was restored and US troops withdrew by the end of 1983. The governor general directly administered Grenada until free and fair elections were held in December 1984; here the New National Party (NNP) won 14 out of 15 parliamentary seats in free and fair elections, and Herbert Blaize became the new prime minister.

The NNP remained the ruling party until Blaize died in 1989. Five of its members left the party in 1986-87 and became the official opposition party, calling themselves the National Democratic Congress (NDC). It put together a ten-seat coalition following the March 1990 elections, so one of its members, Nicholas Brathwaite, was appointed prime minister next.

Following this, the NNP went on a winning streak. In the 1995 elections, the NNP won eight seats and formed a government led by Dr. Keith Mitchell. With the next election, in 1999, the NPP captured all 15 seats, obviously eliminating the need for a coalition. It won for a third time in 2003, meaning that Mitchell served for a total of thirteen years, making him the longest-lasting prime minister so far (1995-2008). The NDC won for a change in 2008, under Tillman Thomas, and then in 2013 the NNP won all 15 seats again, so Keith Mitchell `returned as prime minister.

Jamaica

To the rest of the world Jamaica is the land of reggae, Rastafarians, and ganja; on a funny note, it is also the tropical country that once entered a bobsled team in the Winter Olympics. The first prime minister after independence was Alexander Bustamante (see footnote #99). Feeling his most important work was finished, Norman Manley served as leader of the loyal opposition until his death in 1969. His son Michael Manley took charge of the PNP, and was elected the first PNP prime minister in 1972.

Whereas the elder Manley’s agenda was liberation, especially for Jamaica’s black majority, the younger Manley wanted to advance socialism. He started by raising taxes to pay for increased social services, which caused businesses and investors to get out of the country, at a time when Jamaica could not afford to see them go.(100) During the 1976 election, political violence was bad enough to declare a state of emergency, but Manley won re-election easily and continued his program.

As with Grenada under Maurice Bishop, the United States objected to Jamaica’s normalization of relations with Cuba, and the other things Manley was doing. The CIA even considered removing him from office. Fortunately it didn’t come to that. Though 800 were killed in violence tied to the 1980 election, Manley was defeated and the JLP candidate, Edward Seaga, took over. Seaga broke ties with Cuba and got along great with Ronald Reagan, who ruled at the same time on the mainland; for example, Jamaican troops took part in the 1983 Grenadan invasion.

The PNP and Manley learned their lessons; after 1980 they behaved much more moderately. Manley was elected prime minister again in 1989, and this time his agenda was mainstream. He retired due to deteriorating health in 1992, and was succeeded by Percival James Patterson -- who also came from the PNP and was Jamaica’s first black prime minister.

Patterson ruled through thick and through thin until he resigned in 2006.(101) Since then, there have been three prime ministers: Portia Simpson-Miller (PNP and Jamaica’s first female prime minister, 2006-07), Bruce Golding (JLP, 2007-11), Andrew Holness (JLP, 2011-12), and Portia Simpson-Miller again (2012-). Currently, Jamaicans are most concerned about the high rate of violent, gang-related crime, illiteracy, and the effects of deforestation and land development on the environment. Still as their upbeat music suggests, they are optimistic about the future; they live on an island that many outsiders see as a tropical paradise, and the problems they went through in the past were much worse than what they are going through now.

St. Kitts & Nevis

St. Kitts and Nevis probably shouldn’t have gone off together, because they have argued since then over which island got the better deal in their co-dominion. Indeed, Anguilla was united with them for a while in the late 1960s, and the relationship was really rocky until Anguilla left to become a crown colony of Britain. With the capital and nearly three-fourths of the people on St. Kitts, it looks like that island won the argument, so in 1998 Nevis voted in a referendum on whether to secede. 62 percent of Nevisians wanted to leave, but a two-thirds majority was needed for secession, so the marriage of the two islands continues for the time being.

The Netherlands and French Antilles

|

|

The Dutch and French have kept all their territories in the Caribbean. Unlike Indonesia, Vietnam and Algeria, they did not fight and lose wars over these colonies. The local residents know they will lose more than they will gain if they become independent, so there have been no nationalist movements here yet.

The six Dutch islands are Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, Sint Maarten(102), Sint Eustatius, and Saba. They are located in two groups: the "ABC group" of Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao is close to the South American mainland, while the "SSS group" of Sint Maarten, Sint Eustatius and Saba is 500-560 miles to the northeast, near the northern end of the Leeward Islands. In 1954 the Dutch government organized them all under one government, the Netherlands Antilles. The idea was to make them a separate kingdom under the Dutch crown, but the islanders never fully accepted the arrangement; for a start, the wide spread between the two groups of islands meant they did not see themselves as one state. Aruba seceded from the union in 1986, becoming an autonomous territory, but still with the Netherlands flag flying over it. Referendums were subsequently held on the other islands to see how they felt, and they failed to reach an agreement on anything (the choices were closer ties with Amsterdam, keeping the Netherlands Antilles, autonomy, or independence), so the Netherlands Antilles was dissolved in 2010. Now the arrangement is that Curaçao and Sint Maarten are also autonomous, while Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba (sometimes called the "BES group") make up a single Dutch province.

The French Antilles (also called the French West Indies) are the following seven territories in the Leeward Islands: Guadeloupe, Martinique, Saint Martin, Saint Barthélemy, Les Saintes, Marie-Galante, and La Désirade. Of these, Guadeloupe is divided between two overseas départements or regions of France (named Basse-Terre and Grande-Terre), while Martinique is a third département. Les Saintes, Marie-Galante, and La Désirade are all dependencies of Guadeloupe, so from an administrative standpoint, they are part of the Guadeloupe départements. Saint Martin and Saint Barthélemy also used to be dependencies, but since they are not as close to Guadeloupe as the others, they were detached in 2007, and are now administered by the French government separately, as "overseas collectivities."

Colombia: Land of Drug Lords and Guerrillas

From 1974 onward, Colombia had a competitive democracy again, not a restricted one. The first president of the post-National Front period was a liberal, López Michelsen (1974-78), and he had to deal with severe inflation and unemployment, in addition to the guerrilla insurgencies. This was caused by the quadrupling of world oil prices in 1973-74, at a time when Colombia was not producing enough oil to meet domestic demand.(103) By 1982, Colombia was experiencing its worst recession in fifty years, which of course fueled further social unrest.

Meanwhile, the profits from illegal marijuana and cocaine production were growing. Skyrocketing prices caused by US demand, antidrug efforts by the authorities, and the high cost of smuggling narcotics into the United States, made drugs a big money-making item. Colombia was in a good position to take advantage of this, because its geographic location gave it ready access to both the Pacific and Gulf coasts of the United States. At first the Colombian drug producers concentrated on growing marijuana, but in the 1970s they discovered that because cocaine was cheaper than heroin or opium, they could make even greater profits by manufacturing and smuggling cocaine. Then in the mid-1980s, the price of cocaine fell to the point that it became profitable to make crack, so that was added to the drug-pusher’s portfolio for still more profits.

While all this "narcocapitalism" created jobs and a foreign exchange surplus, the money contributed to inflation, and because it came in through the black market, it put a large part of the national economy beyond the control of the government and law-abiding citizens. And that income did not help the country beyond the short run, because the drug lords used most of it for conspicuous consumption instead of productive investment. Finally, when enough drug money came into the country, it became a corrupting influence; those who had drug money could either bribe officials with it, or hire hit men (sicarios) to threaten/assassinate judges and politicians who did not cooperate with them.

By declaring a state of economic emergency, López Michelsen was able to pass the unpopular economic austerity measures that were needed, without legislative action. He was succeeded by another Liberal president, Julio César Turbay Ayala (1978-82), who turned his attention to fighting the guerrillas. The armed forces and paramilitary forces succeeded in crippling the M-19 and ELN, to the point that by the end of his term, Turbay could end the state of siege that had been declared over the country, on and off, for most of the past thirty years. However, his anti-insurgent policy became highly controversial, when accusations emerged of human rights abuses against suspects and captured guerrillas.

Turbay’s successor was a Conservative, Belisario Betancur Cuartas (1982-86), and he felt confident enough to propose a political solution to the guerrilla problem. This was a cease-fire agreement called the National Dialogue, signed in 1984 with the FARC, EPL, and M-19. The terms of the cease-fire allowed the guerrillas to keep their weapons; the FARC went so far as to establish its own political party, the Patriotic Union (UP). In return for an end to the fighting, the government would carry out a land reform program; pass legislation to improve education, housing and public health; and allow more popular participation in local elections. Alas, the agreement only held up for a year. On November 6, 1985, the M-19 stormed Colombia’s Supreme Court building, the Palace of Justice, and held the Supreme Court justices hostage, with the intention of putting President Betancur on trial. The military retook the building by force, and in the battle, more than a hundred died, including most of the guerrillas and eleven justices. Both sides blamed each other for this incident.

By this time, the drug mafia had grown powerful enough to challenge both the government and the guerrillas. They formed two cartels, based in Medellín and Cali, which became vast international networks, dedicated to growing coca leaf (still largely done in Peru and Bolivia), bringing it to Colombian laboratories to refine into cocaine, and then delivering it to the United States. Soon Colombia was producing between 70 and 90 percent of the world’s cocaine. In December 1981 two drug lords founded a paramilitary group called "Death to Kidnappers" (Muerte a Secuestradores, or MAS), to retaliate against guerilla groups that had financed themselves by kidnapping drug traffickers and holding them for ransom. And they didn’t stop there; groups like MAS became right-wing death squads, going after left-wing politicians, students, and anyone else they suspected of being guerrilla sympathizers. Sometimes they simply killed off the young people in villages that supported the FARC or ELN -- to get rid of the next generation of fighters. When the drug cartels murdered Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara Bonilla in 1984, President Betancur made them his main enemy; declaring a "war without quarter." He went so far as authorize the extradition of thirteen drug traffickers that were wanted in the United States, something he had opposed previously because he felt only Colombia had the right to put them on trial.

The foremost kingpin in the drug trade was the head of the Medellín cartel, Pablo Emilio Escobar Gavíria (1949-93, Pablo Escobar for short). As a kid he started off by stealing tombstones, sandblasting the words off them, and selling them to unscrupulous Panamanians; later he moved up to stealing cars. But in the 1970s he switched to dealing in cocaine, and after that, the sky was the limit. In the 1980s Escobar had so much money and power that he held a seat in Congress, and he made himself popular in Medellín by building schools, stadiums, churches and public housing projects for the poor.(104) And that was only the beginning; he also owned real estate all over Colombia, a private army, a private zoo -- and could order the murder of anyone, anywhere. At the cartel’s height, in 1989, it was smuggling half a billion dollars’ worth of dope into the United States each day. Escobar’s net worth has been estimated anywhere from $3 billion to $30 billion, making him the richest, and one of the most powerful criminals of all time.

To get an idea of what your expenses are like when you have money on that mind-boggling scale, listen to what his brother, Roberto Escobar, said about it: "Pablo was earning so much that each year we would write off 10% of the money because the rats would eat it in storage or it would be damaged by water or lost." Roberto then added that the cartel spent up to $2,500 every month just on rubber bands to "hold the money together."

Because of the government’s campaign against the drug trade, the cartel bosses disappeared from public life and made a remarkable proposal to President Betancur. For immunity from both prosecution and extradition, they offered to invest in national development programs, and even pay off Colombia's entire foreign debt, about $13 billion at the time. The government turned down this and other offers, so now the country saw a three-way war between the cocaine mafia, the guerrillas and the government. This was the situation Betancur passed on to the next president, Virgilio Barco Vargas (1986-90).

Barco tried the same strategy that Betancur had tried at first: make a deal with the guerrillas, while hitting the paramilitary groups and drug traffickers hard. In 1988 he offered the guerrillas a three-step peace plan, which would work as follows:

- The guerrillas would declare themselves in favor of peace and stop terrorist activities.

- The government and the guerrillas would negotiate terms that would allow the guerrillas to return to normal life. The government would provide food, medical services and housing to those guerrillas who needed them at this stage.

- The guerrillas would be allowed to propose reforms to Congress, and participate in elections. The president would issue a general pardon for them if the peace process got this far.

The drug lords did not go away quietly. They couldn’t, really, because the government rejected their offers to end acts of violence and drug-related activities, in exchange for amnesty. In November 1989, a bomb exploded on an Avianca jet flying from Bogotá to Cali, killing all 107 people onboard; in December sixty-two people were killed when a driver on a suicide mission detonated roughly half a ton of dynamite outside the Bogotá headquarters of the Department of Administrative Security; in early 1990 two more presidential candidates were assassinated, those of the UP and the M-19 parties.

The election of another Liberal candidate, César Gaviria Trujillo, as the next president (1990-94), brought a new wave of hope. By this time the 1886 constitution was considered outdated, so the elections also produced a Constituent Assembly of Colombia; they wrote a new constitution, and it took effect in 1991. Also, the government was doing well enough in the drug war(105) that the drug lords were suing for peace terms. After lengthy negotiations, which included passing a constitutional amendment to ban the extradition of Colombians, Escobar and the other cartel bosses surrendered in 1991, bringing an end to the narcoterrorism.(106)

Unfortunately, getting rid of Escobar and the Medellín cartel did not end the drug problem. While the military concentrated on hunting one man and persecuting one cartel, the other cartels rose to fill the resulting void. The Cali cartel did particularly well until 1997, when government crackdowns began to hurt its profits, too.(107) Also, the drug lords diversified into growing opium and selling heroin, and the foreign demand for narcotics never declined. Finally, because the Cold War was over, the guerrilla groups could no longer count of receiving aid from communists abroad, so they went into the drug business to keep on financing their rebellion.

The Pinochet Dictatorship

It is not clear how much of a role the CIA played in Salvador Allende’s downfall, aside from the agency giving $8 million to his democratic opponents between 1970 and 1973. The mainstream media has certainly played it up, though, as one of the worst examples of US meddling in foreign governments in recent history. Soviet propaganda has played it that way, too. According to Vasili Mitrokhin, a former KGB agent, and the historian Christopher Andrew, the KGB and the Cuban Intelligence Directorate launched a campaign known as Operation Toucan to discredit the Pinochet regime. In 1976, the first year of the operation, for instance, it made sure The New York Times published 66 articles on the dismal human rights record of Chile, compared with just 4 articles on the Khmer Rouge holocaust in Cambodia, and 3 articles on human rights violations in Cuba.(108)

The worst years of the Pinochet regime came near the beginning. Not only was the inflation rate at its highest (it took until 1977 to get it below 100 percent a year), but there were more crimes against humanity, as the armed forces stamped out Marxism and the many enemies it saw within Chile’s borders; those enemies included nearly anyone who used to belong to the Popular Unity coalition. Twenty years later, the Rettig Report listed 2,279 politically motivated killings, many of them at the hand of DINA, the secret police. Another 29,000 are believed to have been imprisoned and tortured, while 30,000 left the country. Finally, unions, strikes and collective bargaining were all banned for a few years.

In one case, the Pinochet regime showed that fleeing abroad did not guarantee safety. In September 1976 secret police agents went to Washington, D.C., where Orlando Letelier, the former ambassador to the United States under Allende, was living in exile; they blew up the car containing Letelier and an American friend, Ronni Moffitt. The United States threatened strong action if the agents were not handed over so they could stand trial. Instead of being extradited, the assassins were tried in Chile -- and acquitted.

At first Augusto Pinochet was vague about how long he would run the show; in 1974 he said the junta might remain in power for "ten, fifteen, twenty or even twenty-five more years." The Republican Nixon and Ford presidencies were willing to overlook some sins of the Chilean regime, because most South American governments were behaving this way at the time, and this was the era of Operation Condor, but when Jimmy Carter became president, pressure was put on Chile to take human rights seriously. In response, Pinochet held a plebiscite at the beginning of 1978 to ask Chileans if they approved of him ruling over them. The voting was rigged and the junta didn’t even bother to hide the fact; for example, the ballots were printed to show a Chilean flag over the spot where somebody would mark the ballot to vote "yes," and a black square marking the spot to vote "no." The government reported 75% voted yes, and then told critics to hush for the next two years. Another plebiscite, held in 1980, approved a new constitution and appointed Pinochet president for an eight-year term.

From 1977 onward, the junta embarked on activities that were more constructive than destructive. Gradually it permitted more freedom of assembly, freedom of speech, and trade union activity. Most remarkable was its economic policy; the junta overturned decades of state involvement in the economy, in favor of a laissez-faire free market that encouraged private investment.(109) Tariffs, government welfare programs and deficit spending were all slashed. Because of it, the economy grew rapidly from 1976 to 1981. The technocrats who designed the economy were trained by University of Chicago professors, and were called the "Chicago Boys" for that reason. Also involved was the famous economist Milton Friedman, who had this to say about Chile’s turnaround:

"The really extraordinary thing about the Chilean case was that a military government followed the opposite of military policies. The military is distinguished from the ordinary economy by the fact that it's a top-down organization. The general tells the colonel, the colonel tells the captain, and so on down, whereas a market is a bottom-up organization. The customer goes into the store and tells the retailer what he wants; the retailer sends it back up the line to the manufacturer and so on. So the basic organizational principles in the military are almost the opposite of the basic organizational principles of a free market and a free society. And the really remarkable thing about Chile is that the military adopted the free-market arrangements instead of the military arrangements."(110)

The dictatorship was at its peak when the new constitution went into effect in 1981; at that point the economy was doing splendidly, and the junta’s opponents were defeated. But in 1982 the bill caught up with the party; world interest rates got very high, meaning that Chile would not be able to make payments on the money borrowed in recent years. This led to a financial meltdown, which led to high unemployment. The government had to reverse its economic policy; it nationalized the two largest banks to keep the credit crunch from getting even worse. Critics of the previously mentioned "Chicago Boys" referred to this shift in gears as "the Chicago way to socialism."(111) A series of anti-Pinochet demonstrations spread from organized labor to the middle class to the shantytowns surrounding the cities.

One of the demonstrations. Here young Chileans in Santiago demand democracy and jobs for unemployed copper miners.

The economy recovered over the course of the mid to late 1980s, allowing a resumption of the free market experiment. But even when Chile was the most prosperous nation on the continent, Pinochet was never a popular ruler. The people had always wanted a true democracy, not the authoritarian style of government that Pinochet liked to call a "protected democracy." Consequently, as life got better, the political parties regained their voices and strength. Moreover, the junta came to look out of place as all neighboring countries switched to civilian-run democracy. A military dictatorship may have been the norm for Latin America in the early 1970s, but by the end of the 80s even Paraguay had gotten rid of its tyrant, for crying out loud!

The government promised another plebiscite for 1988, when Pinochet’s term as president ran out. As in 1980, they put forth one candidate, telling the people to vote yes or no on him, and that candidate was Pinochet. This time, however, the vote was 54.5% no. With another term denied, the only thing left for Pinochet to do was begin the transition to democracy. Another election was held in December 1989, to elect a president and a two-chamber Congress. This time the winner of the presidential race, a Christian Democrat named Patricio Aylwin Azócar, was backed by a coalition of seventeen political parties, and secured 55% of the vote, so there was no denying he was the peoples’ choice.

Peru: The Disastrous 1980s

People tend to become more conservative as they get older, and Fernando Belaúnde displayed that trend; we have already seen him as a liberal in the 1950s, and a moderate in the 1960s. Now we shall see him as a conservative. For his second turn as president, instead of pursuing reform, he made privatization of state-run businesses his priority, in the hope that the revenue generated would increase exports and help pay down the national debt. No such luck; more than one El Nino year struck, causing the usual natural disasters (see Chapter 1, footnote #10), and there was a sharp plunge in international commodity prices, wiping out the profit that should have come from exports. Production fell, inflation and unemployment surged, the government had to borrow more money to make ends meet, and the minister of finance declared that the country had entered an economic crisis that was worse than even the Great Depression. Outside the cities, rising infant mortality, falling life expectancy, famine and the lack of jobs filled the people with discontent. They expressed their anger by joining two new guerrilla movements: the Maoist Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso, or SL), founded at Ayacucho in 1980; and the pro-Cuban Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru, or MRTA), founded in Lima in 1982.

Belaúnde first ignored the guerrillas, and then tried to crack down on them with the police. When both approaches failed, he reluctantly turned to the army to put down the rebels. But because they were based in the Andes, the SL were extremely difficult to uproot, while human rights violations by the army resulted in strong criticism of the Belaúnde government from abroad, and drove more recruits to the SL. On the country’s northern border, Peruvian armed forces marked the thirty-ninth anniversary of the signing of the 1942 Protocol of Rio de Janeiro by clashing with the troops of Ecuador for five days (1981); this did nothing to resolve the border dispute between the two nations, though.

Some Peruvians saw growing more coca as a solution to financial hardship, now that there was widespread demand in North America and Europe for the refined version of it: cocaine. Thus, as if Belaúnde didn’t have enough to deal with, there was also a steep increase in drug trafficking during his presidency (the growing of coca for anything but local consumption had been outlawed in 1978). The Colombian drug cartels bought the harvest to process and smuggle it to drug users; the guerrillas also supported the drug trade, defending the growers from the state and from drug traffickers who demanded too much, in exchange for a "tax" skimmed off the profits (e.g., the SL collected as much as US $30 million a year in this fashion).

At the end of his term 1985, Belaúnde had little to show for it, except that even with human rights violations harming his record, freedom and the parliamentary process had survived. He was admired by Peruvians from all walks of life for restoring democracy, albeit in an imperfect form; moreover, he was the first elected president in forty years to serve a complete term. He was now in his seventies, but instead of retiring, he went to Congress as an honorary "senator for life." When he died in 2002, he received the grandest funeral in Peru’s history; I don’t think even the Inca emperors got that kind of a send-off!

With the 1985 election, APRA won the presidency for the first time. APRA’s candidate, a thirty-six-year-old lawyer named Alan Gabriel Ludwig García Pérez, secured 45 percent of the vote, while the Marxist United Left Party (Izquierda Unida, or IU) came in second place with 23 percent; Belaúnde's party was so discredited by the events of the past five years that it only got 6 percent. Because nobody won a majority, there should have been a runoff between the top two vote-getters, but the IU candidate dropped out, stating that he did not want to prolong political uncertainty in a time of crisis; this allowed García to win by default. It also helped that APRA won a majority of the seats in Congress, making sure that there would be no gridlock to keep García from getting legislation passed.

Alan García had no political experience, but his youth (some called him a Peruvian John F. Kennedy) inspired some hope for the future. So did his public speaking skills; he liked to entertain crowds with weekly speeches on the balcony of the presidential palace, which were called balconazos. He also pleased the public by cutting taxes, raising wages and freezing prices. Finally, he announced in his inaugural address that when handling Peru’s $13+ billion foreign debt, he would go directly to the creditor banks, not the IMF, and that he would limit interest payments to 10 percent of Peru’s export earnings, or $400 million. As he put it, "Peru has one overwhelming creditor, its own people." Unfortunately the economy could not afford these activities, and under García the state of the economy went from bad to worse.

The most visible symptom of financial insolvency was inflation, which became hyperinflation from 1988 onward. In 1990 the inflation rate reached 7,649%, and over the course of García’s term (July 1985-July 1990), prices rose a total of 2,200,200%. The government tried to keep up by changing the currency more than once. In 1985, right when García became president, the sol (sun) was replaced with the Inti (named after the Incan sun-god), at an exchange rate of 1,000 soles = 1 Inti. Then in 1991, the nuevo sol (new sun) replaced the Inti; by then a new sol was valued at one billion old soles. Because of the hyperinflation, the country’s per capita income fell to US $720, and the GDP plummeted by 20%. And in an environment of economic chaos, the guerrillas flourished. García tried to crush the SL and MRTA with military force, the way Belaúnde had -- and got the same dismal results.(112)García stopped holding balconazos before the end of his term, a sure sign that both he and the people were no longer in a good mood. APRA was so disgraced that in the 1990 election, it could only come in third place. The two candidates who made it to the runoff round were Mario Vargas Llosa and Alberto Fujimori. Vargas Llosa ran as the nominee of a center-right coalition called the Democratic Front, formed by a merger of the old AP and Christian Democrat parties. He had name recognition and a lot of good press coming into the race, since he was Peru’s most celebrated novelist. However, he was only interested in the European part of his heritage, which rubbed non-white Peruvians the wrong way; they saw him as too aloof, too cultured and too privileged. What's more, he promised an economic "shock treatment" program that was likely to send more Peruvians into poverty before it got results.