| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Latin America and the Caribbean

Chapter 3: A New World No More, Part III

1650 to 1830

This chapter is divided into three parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| A Hollow Empire | |

| The Jesuit Experiment | |

| Caribbean Contention, Part 1 | |

| The Golden Age of Piracy | |

| Famous Pirates | |

| The Darien Scheme and the South Sea Bubble | |

| Caribbean Contention, Part 2 | |

| The Settlement of Mexico's Northern Frontier | |

| The Seven Years War and the American Revolution In Latin America |

Part II

| Growing Trouble between Spain And Her Colonies | |

| Brazil: Movement Inland, and to the South | |

| The Haitian Revolution | |

| The Liberation of Latin America Begins | |

| Bolívar and San Martin | |

| The Haitian Monarchy |

Part III

Bolívar's Campaigns

Simón Bolívar did not stay on Curacao for long. Before 1812 was over he sailed to Cartagena, where he would launch his “Admirable Campaign” (Campaña Admirable). Like Caracas, Cartagena had declared independence from Spain, but control over New Granada was divided between the Cartagena nationalists and another group based in Bogota, so the royalist general Monteverde was planning to invade New Granada next. Because of that, Cartagena welcomed Bolívar and immediately put him in charge of the 750 soldiers they had.

Before he began marching, Bolívar showed what he had learned from Venezuela's First Republic, by writing the Cartagena Manifesto. Here he presented the ideology he would follow for the rest of his life. As he put it, "Not the Spaniards, but our own disunity had led us back into slavery. A strong central government could have changed everything." Because South Americans had no experience with democracy, a representative government could not work; it would take a dictator, a “terrible power” as he called it, to drive out the Spanish forces, and bring freedom and happiness. Likewise, tolerance and observance of human rights had made North America's revolution a success, but that didn't mean they would work the same way here. From that point on, Bolívar would be another Napoleon as well as another George Washington.

Bolívar started the campaign by taking two royalist cities in what is now northeast Colombia: Ocaña (captured January 28, 1813) and Cúcuta (February 28). Now across the Andes, he marched rapidly into Venezuela. On the way many poor Venezuelans joined him, enlarging the army's size to 2,500 men, because the Spanish government imposed on the country had already proven itself crueler than the republicans had been.

There were no “rules of war” in this conflict; both sides tried to outdo one another when it came to atrocities. One Spanish general collected the ears of republicans, and encouraged his men to wear such trophies like feathers on their hats. On the other side, Bolívar, unlike Miranda, was willing to ruin Venezuela to free it. As he advanced he issued his Decree of War Unto Death, which announced he would treat Europeans and Creoles differently: "Spaniards and Canarians [people from the Canary Islands], count on death, even if indifferent, if you do not actively work in favor of the independence of America. Americans, count on life, even if guilty."

This time, however, Bolívar had everything his way. The royalists were isolated in small groups, which he defeated one by one, and he reached Caracas on August 6. White-clad girls led his horse through the streets, while the crowd shouted, "Long live our Liberator!" Bolívar liked this so much that he gave himself the title of El Libertador, and always used it after that.

Taking over a country is one thing; administering it is another, and often tougher. Bolívar found this out as dictator of Venezuela's Second Republic. The economy was in a mess, the land was war-ravaged and depopulated. Worst of all, from Bolívar's point of view, the country was not united. Most of the land to the east had been cleared of Spaniards by another nationalist group, and its young leader, Santiago Marino, did not want to share power with Bolívar.

Marino's refusal to cooperate meant that the Second Republic would be as short-lived as the First, because both he and Bolívar had a terrible new enemy to the south. We saw in Chapter 2 that central Venezuela has an inhospitable tropical grassland called the Llanos (also spelled Ilanos); it was one of the harder areas to explore in South America. Here grass grew as tall as a man and cattle ran free. It was also the current home of Jose Tomas Boves, a pilot in the Spanish merchant marine who had been exiled to the Llanos for smuggling. He had joined Monteverde's army when the general took Calabozo, the town where he was staying, in May 1812, and in January 1813 he was put in command of Calabozo. In that position he recruited soldiers from the mixed-race cowboys of the region, the Ilaneros. Officially Boves was a royalist, but he ignored the orders of royalist generals and paid no attention to the 1812 constitution that was now supposed to be the law of the land. Likewise his men were not interested in politics; what motivated them was the opportunity to pillage republican towns and villages. Armed only with knives, lances, and lassos, the Ilaneros burned, looted, and raped, leaving a trail of devastation wherever they went. Boves was the cruelest of all; he would order the dismemberment of children, or force men and women to walk barefoot on broken glass. Because most of the Ilaneros were not white, this was the kind of race war that the Spanish government had promised to protect its white colonists from; now it was being used against them.

Bolívar responded to this mindless brutality by ordering the execution of 800 royalist prisoners, including the ill and wounded, in the spring of 1814, because he feared they might rebel. This did not help his cause, nor did it stop Boves. Short of armaments and totally demoralized, the republicans abandoned Caracas to the Ilaneros in July, less than a year after Bolívar had triumphantly entered the city. Twenty thousand civilians fled eastward, many to die along the way, while Bolívar returned to Cartagena.

Boves was killed in battle at the end of 1814, but Bolívar and the republicans did not get much relief, because once again events in Europe decided what happened in the Americas. This time peace broke out. The Napoleonic Wars ended; Napoleon went into exile; Ferdinand VII returned to the throne of Spain. Ferdinand was determined to turn back the clock to make Spain just like it had been before the 1808 French invasion, and that included solving what he called the “American problem.” Accordingly, he sent 11,000 men across the Atlantic in the spring of 1815, under the command of General Pablo Morillo. After they occupied Caracas, they sailed on to Cartagena, besieged that port and took it in December; most of Cartagena's inhabitants starved to death before the siege ended. Finally Bogota fell to them in May 1816.

This was the lowest point for Bolívar's career and the Latin American revolution. Bolívar was now a refugee again, this time in Jamaica. With the reconquest of Chile, Venezuela and New Granada, and the suppression of Hidalgo's revolt in Mexico (see below), it looked like Spain had beaten the rebels one more time. Four-fifths of Spain's American empire was back under Spanish rule; only the states around the Rio de la Plata were still free.

Bolívar stayed in Jamaica for six months, where he wrote another manifesto calling for strong central government, the Jamaica Letter. Then he went to Haiti(44), where he joined other revolutionaries and prepared for another campaign. This campaign, the Expedition of Los Cayos, consisted of five raids on the Venezuelan coast, between March and December of 1816. It was an expensive venture that gained nothing, so when Bolívar returned to Haiti for the last time he came up with a new strategy.

The most important thing he realized was that any campaign that began with an attack on the Venezuelan coast was doomed to fail; his homeland was too well defended, and it was too easy for Spain to send troops there. Bolívar now decided to save Caracas for last, and follow the path of least resistance. For a home base, he would build it somewhere in the interior, and live off the Llanos like Boves had done. The easiest way to go inland was to head upstream on the Orinoco River; here the royalists were not strong because the course of that huge river went through swamps, jungles and Llanos. Bolívar did that in 1817, and found the base he was looking for at Angostura. This town of 6,000 people was the richest community on the Orinoco, and is located at the river's narrowest crossing point (about one mile wide); today it is called Ciudad Bolívar. Angostura had just been captured by Manuel Piar, a mulatto general who came originally from Curacao, and had fought both English invaders on his home island and the royalists in Venezuela.

Early Paraguay: Marxism Before Marx

Bernardo de Velasco did not last long after he secured Paraguay's independence. He was already unpopular because he had run away from the battle of Paraguarí, though the Paraguayans went on to win without him. Concerned that the officers leading his army were a threat to his rule, he disbanded most of the army after it stopped General Belgrano's invasion, sending home the soldiers without paying them for eight months of service. Then the Asuncion junta sent a request to Brazil for Portuguese soldiers, because Belgrano was camped just across the border and it looked like he might come back. For the officers this was too much; the uprising they launched compelled the junta to declare independence from everybody on May 17, 1811, and to depose Velasco.

Paraguay has been the most unlucky of nations, when it comes to government. For 178 years after its declaration of independence, every one of its leaders was tyrannical and/or incompetent. However, modern Paraguayans often make an exception for their first head of state, José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia (1766-1840). Francia was definitely a different sort of dictator, presumably because he did not have a military background, and had enough redeeming qualities for some historians to consider him Paraguay's best ruler. To start with, he was not a corrupt man, and used his power to enrich the state, not himself; we'll talk more about that below. He was also a hundred years ahead of his time, establishing a communist-style state before Karl Marx was even born.

At the time of independence, only a few Paraguayans could read, and fewer had the skills in finance and administration that a modern government needs--the Spanish rulers and the Jesuits didn't bother to teach them. One of those who did learn these skills was Francia; he studied theology at the nearest university, in Cordoba, Argentina. Rumors suggested that his Brazilian-born father was a mulatto, but that did not keep him from winning a coveted chair of theology at the Seminary of San Carlos in Asunción in 1790. He could not stay as a teacher though, because of his radical political views--he was a fan of both the Enlightenment and the French Revolution--so he studied law and became an activist lawyer instead. Defending the rights of people from the lower classes was more suited to his tastes, and by 1809 he had become head of the Asunción cabildo, or town council; when Paraguay declared independence two years later, Francia joined the ruling junta.

As it turned out, Francia may have been the only man in the country with the diplomatic, financial, and administrative skills needed to run it. At the end of 1811, he grew concerned about the role military officers were playing in the junta, so he showed who was more important by resigning. From the modest home he retired to, Francia told the commoners who visited him that the revolution had been hijacked; instead of a Spanish-dominated government, they now had a Creole-dominated one, and the country was in danger of invasion from either Argentina or Portuguese Brazil. When the junta learned that the Argentine nationalists were sending a diplomat, Nicolás de Herrera, to Asunción, it panicked because none of its members knew how to negotiate with him. Then they remembered Francia and invited him to come back, as the junta member in charge of foreign policy, and Francia accepted, on condition that he be given half of the army and half of the army's munitions as well. The junta agreed, so now Francia was the most powerful man in the government.

When Herrera arrived in May 1813, he was not allowed to do anything important. Though he stayed until an elected Paraguayan congress met at the end of September, he was not allowed to attend that, either. The congress, Paraguay's equivalent of a constitutional convention, was quite remarkable, for whereas the governments in other parts of Spanish America were Creole-dominated, many of the 1,100 Paraguayan delegates represented the poor, mixed-race majority. Following Francia's foreign policy, the congress rejected all proposals to unite with Argentina. For Paraguay's government they established a republic, with Francia as its first consul. This may sound like a step toward democracy, but in practice it was the beginning of a dictatorship dominated by Francia. Every four months Francia was expected to trade places with the second consul, Fulgencio Yegros, but Yegros was a figurehead without ambitions, picked to represent the Creole-dominated military; Francia's power outweighed that of Yegros because Francia had the support of the Indians and Mestizos. In 1816 Francia had another congress proclaim him dictator for life.

For the rest of his life, Francia was known as El Supremo Dictador (The Supreme Dictator) in Spanish, and Caraí Guazú (Great Lord) in Guarani. Anyone who did not give him the respect he felt he deserved was immediately executed. Instead of delegating the nation's responsibilities to a cabinet of ministers, he ruled by himself. No state decision, even the smallest ones, could be made without Francia's approval. People were arrested without charge and disappeared without trial. Those who were accused of plotting against Francia were sent to a torture chamber called the "Chamber of Truth," and every year about 400 of those prisoners ended up in a detention camp, where they were shackled in dungeons and denied medical care and even the use of sanitary facilities. He even had all dogs shot, simply because he didn't like them. After a failed assassination attempt in 1820, El Supremo had everything he ate and drank checked for poison, did not let anyone get closer than six paces, and slept in a different bed every night.

Francia had a special grudge against the aristocracy, because of their racist attitude toward the Indians and Mestizos, and perhaps because they had used accusations of “impure blood” to discriminate against him. To get even, he imposed incredibly high marriage taxes that kept whites from marrying other whites. Whites could marry Indians without paying the taxes, though, and when he saw how this eliminated racial conflict in the country, Francia made mixed marriages mandatory.(45) In 1821 he summoned all 300 of Paraguay's Peninsulares to Asunción's main square, where he accused them of treason, had them arrested, and locked them up in jail for 18 months. Francia released them only after they agreed to pay an enormous fine of 150,000 pesos (about 75 percent of the annual state budget at the time), an amount so large that it broke their control over the Paraguayan economy.

Speaking of the economy, under Francia it was run not on capitalism, but on confiscation; the case where he squeezed 150,000 pesos from the Peninsulares is the best example. In the name of preserving independence, Francia imposed an isolationist policy so strict that foreign trade stopped, except for a few state-approved transactions. Anyone who was caught trying to leave the country was executed; foreigners who got in had to stay for the rest of their lives, and they were lucky if the state did not confiscate everything they had. These confiscations allowed the state to run on a low tax rate, and made the government the nation's largest landowner.

The most famous victim of Francia's foreign policy was José Gervasio Artigas, "the father of Uruguay." For twenty years Artigas had resisted every outside attempt to rule the Banda Oriental district, whether the outsiders were Portuguese, Spaniards, or the Porteńos of Buenos Aires. It looked like the Buenos Aires junta had made Artigas a partner, when in 1815 it agreed to give autonomy to the district, with Artigas in charge of it. But the Portuguese invasion that took place a year later (see below) was more than Artigas could handle, so he fled to Paraguay. Francia granted him refugee status, but otherwise treated him like any other foreigner and refused to let him leave. Thus the nationalist was stuck in Paraguay; by the time of Francia's death, Artigas was too old to go home. Artigas lived another ten years after that, reaching the age of eighty-six; when he sensed that his time was up, he asked to be mounted on a horse, so that in true gaucho fashion, he would die in the saddle.

Francia hated the Church as much as he hated the aristocracy. He resented how for centuries the Catholic Church had taught the Indians to submit to both the pope and the king of Spain. In response he closed the country's only seminary (the same one where he had once been a teacher), and divided the land it owned between 875 families. In addition he banned religious orders, forced monks and priests to swear loyalty to the state, abolished the practice of clerical immunity in civil courts, confiscated more church property, and put church finances under state control. After a while he did not want to see any form of social distinction, so in the name of creating a classless society he banned fiestas, too.

Francia was as hard on his own family as he was on his subjects. He never cared much for marriage (all seven of his children were illegitimate), and when his sister got married without his permission, he had both the husband and the priest who performed the wedding shot. The sister simply disappeared, which may or may not mean she was shot, too. Every day he would draw just two pesos from the treasury to cover his family's expenses. Of course this wasn't enough to keep the family fed, so his eldest daughter became a prostitute to earn the rest of what they needed. When Francia found out, he legalized prostitution, declared it an honorable profession, and decreed that all "women of the night" should wear gold hair combs. This gave them the nickname of peinetas de oro, humiliated another Spanish fashion, and will probably get Francia nominated for the title of "worst father," if such a contest is ever held.(46)

Over the Andes

While Simón Bolívar was establishing himself at Angostura, Jose de San Martin was moving out of Mendoza. San Martin had spent two years there, preparing to cross the southern Andes, which he understandably felt would be the most difficult part of his campaign. To make sure his “Army of the Andes” had enough arms, ammunition and uniforms, he built an arsenal, powder factory and textile mill at Mendoza. The women of Mendoza helped by donating their jewels. He also recruited and trained new soldiers, until he had 4,000 troops and 1,400 auxiliaries.

Many of San Martin's recruits were refugees from Chile, who fled east after Spain's victory at Santiago. The most important among them was Bernardo O'Higgins. His father, Ambrosio O'Higgins, was born in Ireland, and though he wasn't a full-blooded member of the caste, he had risen from being a merchant-adventurer, ultimately becoming viceroy of Peru in the 1790s.(47) The younger O'Higgins became a revolutionary when he met Miranda in London. When Chile revolted, he became commander in chief of its army, and was defeated for the same reason that Bolívar had failed to hold onto Caracas – he and his fellow nationalist officers were disunited when the Spaniards returned. San Martin put him in charge of the Chilean soldiers in his army; this proved to be a wise choice.

The Army of the Andes began its march in January 1817. They used four separate passes to get through the Andes, in an area 500 miles across. The passes went as high as 12,000 feet, and despite all the planning, it was still a tough journey, less than half of their 9,000 mules and only a third of the 1,600 horses survived the journey. But they escaped the worst danger – no Spanish force tried to attack them before they reached Chile. San Martin had sent agents ahead to spread false rumors about what he was doing, so the Spaniards were taken completely by surprise when he showed up on the other side of the mountains. Here San Martin's army reassembled at exactly the place and time where they had planned to do so, and routed the Spanish army at the battle of Chacabuco (February 12); three days later they entered Santiago in triumph.

Of course San Martin would have to secure the Chilean capital to make sure his victory would not be undone, so he and the army marched around in central Chile for the next year. They advanced south as far as Concepcion, and won a critical battle at Maipú in early 1818. San Martin put O'Higgins in charge of Chile's government, taking nothing from the country for himself. The last step on his campaign was conquer Peru, so he began preparing for that. Here the most important point was that the army would have to travel by boat, because the barren Atacama Desert made it impossible to march from Santiago to Lima without suffering heavy losses. O'Higgins managed to create the navy they needed by buying a few ships from Britain and the United States; then he hired mercenary crews for them, and captured some Spanish ships as well. A brilliant British admiral, Lord Cochrane, was made commander of the navy when he came to Chile in 1819.

In August 1820 San Martin's fleet – eight warships and sixteen transports – finally left Valparaiso for Peru. It was more than just preparations that made him wait so long before attacking – San Martin was also counting on diplomacy to help him win. Despite his success to date, San Martin's army was smaller than the Spanish force defending Lima, and because Lima was the hub of the Spanish Empire in South America, he expected a tough fight for it. He thought that if he avoided hitting Peru hard and fast, a local uprising would do most of the work for him, but that didn't happen, so the fleet continued up the coast as far as the Paracas peninsula, where it came ashore and took the town of Pisco. When he got to Lima he still didn't attack the city, but partially surrounded it.

At the beginning of July 1821, San Martin met with the viceroy of Peru, José de la Serna e Hinojosa. Because the Peruvians were not ready for a republic, he proposed creating a constitutional monarchy in Peru, run by a European monarch to be appointed later, but Serna claimed he did not have the power to create a monarchy, or even to declare independence.(48) However, the viceroy's position was getting precarious, due to Simón Bolívar's victories; any troops sent from Spain were more likely to go to New Granada than to Peru. On July 8, 1821, la Serna simply abandoned Lima, taking his army into the Andes to gather reinforcements. San Martin marched in the next day, declared Lima independent of Spain, and gave himself the title of “Protector of Peruvian Freedom.”

San Martin proclaiming Peruvian independence in Lima, on July 28, 1821. To the crowd he said, "... From this moment on, Peru is free and independent, by the general will of the people and the justice of its cause that God defends. Long live the homeland! Long live freedom! Long live our independence!"

But San Martin could not declare the job finished while a royalist army was camped in the resource-rich mountains. His army was still weaker, so he would need help to take it on, but he had a hard time getting Peruvian recruits from Lima's population. The Peruvians soon resented having San Martin in charge because he was a foreigner to them, while many of his republican followers were alienated by his proposal of a monarchy for Peru, thinking that he wanted to crown himself king. On the banks of the Rio de la Plata, civil war broke out between Buenos Aires and the troops in the provinces; when the latter won the first battle of Cepeda (1820), the unstable central government collapsed. No Argentine ruler would support San Martin after that, because he had marched on Lima without their permission. This left him only one source of aid: the army of Simón Bolívar, who was now in Ecuador. Both Bolívar and San Martin wanted the Ecuadorean port of Guayaquil, so that decided matters. "I shall meet the Liberator of Colombia," San Martin announced, and in 1822 he hurried north, instead of engaging the royalist army in his backyard.

Gran Colombia

Before Simón Bolívar could begin his next campaign, he had to show the other rebel commanders who was boss. A government was set up at Angostura, but the republicans could not agree on who was in charge of it; leadership descended in a triumvirate of three commanders whose names changed frequently. More serious than the instability was the threat from Manuel Piar. Besides independence from Spain, Piar's ultimate goal was more rights for the Mestizo population, and because Piar was not white, he could persuade the masses of slaves and free Pardos to join his army.(49) When he began plotting with other high-ranking officers who opposed Bolívar's leadership, Bolívar had him arrested and charged with insubordination, desertion and conspiring against the government. A court-martial upheld these charges, and to the amazement of many, Piar was executed. There is a strange story which asserts that Bolívar chose to go to his office, instead of witnessing the execution, and when he heard the shots of the firing squad from there, said in tears, "He derramado mi sangre" (I have spilled my blood). After that, however, Bolívar claimed that he had saved the country: “Never was there a death more useful, more political, and at the same time more deserved.” That example brought the other generals in line. Santiago Marino, for one, was even more guilty of insubordination than Piar had been, so he came to Angostura and swore allegiance, dropping the idea that he would be an independent leader.

To tame the Llanos, Bolívar found a new ally in Jose Antonio Paez Herrera (1790-1873), the local strongman who had replaced Boves. An illiterate Creole, Paez had been attacked by four highwaymen in 1807, when he was just a teenager; he used a pistol and a saber to kill one assailant and drive off the rest. Fearing both revenge and the law, he then fled to the Llanos, where he became a genius at guerrilla warfare. Like Boves, he was a violent man, who claimed to have killed seventy men with his own hands. However, he also had epilepsy and was likely to suffer a seizure during battle, so he had a huge black manservant, known simply as El Primo Negro, to carry him off when that happened. Paez and Bolívar got along well from a start, and as one of Bolívar's generals, Paez never lost a battle.

More aid to Bolívar came from an unexpected source – across the Atlantic. We saw earlier that the British government was not willing to support Bolívar. However, many private British citizens were willing. Now that the Napoleonic Wars were over, thousands of British ex-soldiers were either unemployed, or bored with a peaceful life at home; British merchants also had tons of surplus war materiel to sell, which Bolívar's London agent, Lopez Mendez, gladly bought. Bolívar had always admired Britain for its democracy, industry, and first-rate armed forces, so he was happy to recruit a private army of 5,000 English, Scots and Irish. These mercenaries were not dressed for war in the tropics (the age of British warriors wearing pith helmets in Africa was still several decades away), nor did many of them know what they were getting into, so a lot of them soon deserted or died of disease. However, those that survived stayed with Bolívar for the rest of his campaigns, giving him and his cause everything they had; most of them never saw the British Isles again, either.(50)

Like Jose de San Martin, Bolívar spent two years preparing for his next campaign, once he had a secure base. He also marched over the Andes, but in this case, he didn't decide on this course until he was ready to move out. In February 1819, a congress of elected representatives met at Angostura, and there Bolívar delivered a speech that proposed a constitution for Venezuela. The speech was so impressive that his rival Marino claimed Bolívar "could have convinced stones of the necessity of his victory." However, the constitution he wanted would not be as democratic as the US one; because he still considered unity to be more important than freedom, his version of the senate would have members chosen by heredity, not elections, like the House of Lords in London. He also announced that he would unite New Granada with Venezuela to form a state called Gran Colombia. Not only did he convince the congress to approve his ideas, one day later it elected him president of the Third Venezuelan Republic as well. In May he met with his generals and proposed that this time they should invade New Granada, because he and Paez were still getting nowhere when it came to clearing the royalists out of northern Venezuela.

The generals agreed with Bolívar. Once they went forth, they first encountered Spanish soldiers at Gamarra Ranch, about 15 miles from the town of Achaguas (March 27, 1819). They brushed aside this obstacle easily enough, and spent April foraging in western Venezuela, only to find out when they resumed their march that this was the worst time of the year to attempt an Andes crossing. The rainy season began in May; soon the Orinoco and all its tributaries were overflowing, causing serious hardship before the army of 3,000 men even reached the foothills of the mountains. Bolívar's Irish-born aide-de-camp, Daniel Florencio O'Leary, wrote that "For seven days we marched in water up to our waists." Cowhide boats had to be made on the spot to transport heavy equipment and those soldiers who could not swim.

After the flooded rivers came the mountains. For the men of the Llanos, this part of the journey was worse. Rocks cut their boots to ribbons, leaving the army mostly barefoot when it reached the other side. The path Bolívar chose climbed to the Paramo de Pisba, a bleak plateau more than 13,000 feet above sea level. This was the hardest course he could have taken, and Bolívar's enemies thought it was impossible to go that way during the rainy season; they were nearly right. Cold weather, lack of oxygen, fatigue and mishaps on the slopes killed all the horses and cattle, and more than half of the men.(51)

Fortunately the survivors got an enthusiastic welcome from the peasants on the Colombian side of the Andes, when they arrived in early July. The peasants gave them fresh food, clothing, horses and mules. Many joined Bolívar's army willingly, but others were forced to join at gunpoint. Either way, the army's strength was restored, and when it encountered the Spaniards, the latter were taken completely by surprise. The critical battle was fought on August 5, 1819; here 2,000 republican soldiers clashed with 3,000 royalists on a bridge over the Boyaca River. The battle only lasted about two hours and claimed few casualties, but 1,600 royalists were captured, and that was enough to decide the destiny of South America. Five days later, Bolívar made his triumphal march into Bogota, which welcomed him with a flower-strewn procession.

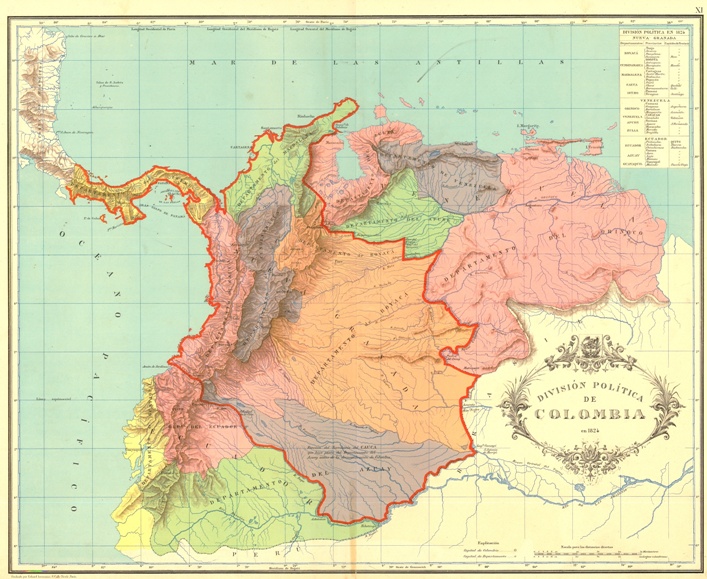

The last viceroy of New Granada fled to Cartagena, which in turn fell to the republicans in 1821. Bolívar did not lead that campaign, though. Instead, as soon as he was done celebrating in Bogota, the Liberator hurried back to Angostura to plan what to do next; he appointed one of his generals, Francisco de Paula Santander, as his vice president over New Granada. In Angostura, on December 17, 1819, the Venezuelan parliament approved his ultimate dream, by proclaiming the establishment of Gran Colombia (at the time, they called it the Republic of Colombia). This nation held all the land belonging to the Viceroyalty of New Granada: modern-day Colombia, Ecuador, Panama(52) and Venezuela. There were still Spanish troops in all four of those provinces, but the momentum was now with Bolívar, so it no longer looked like they could stay. Not only was Bolívar winning the battles, but a barracks mutiny in Spain itself (see the next section) had destroyed the confidence of the Spanish government. Now that Spain's soldiers had made it clear they did not want to fight for a reactionary regime, few of them would be crossing the Atlantic to crush the Latin American revolutions.(53)

Gran Colombia in 1824. The red line marks the borders of New Granada (today's Colombia) after Venezuela and Ecuador broke away. Click on the map to see it full size (opens in a separate window).

Bolívar's opponent on the battlefield, General Morillo, now received new orders: enforce the 1812 constitution in the areas where Spain was still in control, and negotiate with Bolívar. When they met, Morillo expected somebody more impressive, after five years of fighting; the general exclaimed, “That little man in the blue coat and campaign hat sitting on a mule! That is Bolívar?” Bolívar soon won him over, though. After the meeting, they were no longer enemies; they slept that night in the same room, and parted like brothers the next day. This was perhaps Bolívar's most amazing victory – he had overcome a general without using violence. As for Morillo, he asked to be relieved of his command and returned to Europe.

The two sides agreed to a six-month truce in November 1820. At the end of five months, though, the strength of Bolívar's army had grown to 7,000 men, so the republicans resumed hostilities. They were also confident enough to make another attempt at Venezuela's coastal plain. After winning a key battle at Carabobo (June 24, 1821), Bolívar entered Caracas in triumph for the last time.

One more Spanish fleet attempted to land royalist troops in 1823; it was defeated in Lake Maracaibo. There was also some mopping up to do before all of Venezuela was free, but Bolívar now turned his attention to another province--Ecuador. Ever since the suppression of the 1809 Quito uprising, Ecuador had been firmly under Spanish rule, but now the news of the spreading revolution encouraged the port of Guayaquil to declare independence on October 9, 1820. Bolívar could not leave Venezuela immediately, so he sent his best general, Antonio Josè de Sucre, to begin the campaign. Then in the fall of 1821, he headed south to join Sucre. At the Colombian town of Cúcuta, he stopped just long enough to meet the newly organized Congress of New Granada, and accept from them the presidency of that country; again he chose General Santander as his vice president.

Sucre managed to conquer most of Ecuador without Bolívar's help. The royalists defeated him in the Andes on September 12, 1821 (the second battle of Huachi). After that Sucre moved into the highlands south of Quito instead, which cut off the royalists from the Spanish army in Peru. The royalists made their stand on the slopes of Pichincha, a volcano just outside Quito; when the republicans won that battle (May 24, 1822), there was nothing to stop them from entering Quito the next day. However, what Bolívar really wanted was Guayaquil, the best port on the Pacific coast between Lima and Panama City; he was determined to see Guayaquil become part of his state, not part of Peru. There was also a personal matter; Bolívar was jealous of the success of Jose de San Martin; he was not thrilled to learn that another liberator had driven the Spaniards out of Chile and Lima. Now the man he considered his greatest rival was headed to Guayaquil, too.

The First Mexican Empire

Mexico and Central America were reluctant participants in the Latin American wars for independence. Unlike the Spanish part of South America, in 1810 the white population north of Panama was not ready to break with Spain, even when Spain was under French occupation. Instead of political activity, during the eighteenth century there had been several messianic movements in Mexico; many of them involved sightings of the Virgin Mary, and many called for political autonomy. Therefore it was a priest, not a secular politician, who found a way to turn such visions into action.

Mexico's independence movement began in a village, not a major city. This village was Dolores (modern Dolores Hidalgo), and the one who started it was a local priest, Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. Normally clergymen are expected to support the current establishment, but Hidalgo was not from a noble family; he was the son of a farmer, and he had already earned the disapproval of his superiors by reading Rousseau and the other French philosophes, so his sympathies were with the poorer (mostly Indian) members of his congregation. In September 1810 he roused them with a call to take back the land that the Spaniards took from them nearly three centuries earlier. After this speech, the so-called grito de Dolores, he led a group of peasants, marching under the emblem of the Virgin of Guadelupe. They advanced twenty miles to the town of San Miguel el Grande (modern San Miguel de Allende), where they met a sympathetic Creole general, Ignacio Allende, and his 1,000 soldiers joined them. Three victories over the next three months caused the army to swell to 60,000; next on their agenda was Mexico City.

It was at this point that Hidalgo's campaign fell apart, for he had very few people of European ancestry among his followers, and the whites in Mexico City were positively terrified that an army of Indians might decide their future. Creoles and Peninsulares hastily put together a royalist army of 30,000, led by a veteran officer named Felix Maria Calleja. This was strong enough to make Hidalgo and Allende turn back, when they reached the outskirts of Mexico City. From that point onward, the initiative was with Calleja, and he inflicted defeats on the revolutionaries at Acapulco (November 1810) and near Guadalajara (January 1811). Hidalgo was captured in March 1811, and shot in July, along with Allende.(54)

Hidalgo's cause lived on, though. Leadership of it was taken up by Jose Maria Morelos, another combination priest/general. He gave the movement better military and political leadership, and campaigned all over central Mexico, but in late 1815 he was captured and executed as well. His successor was a mulatto officer, Vicente Guerrero, who managed to keep the rebellion alive in Oaxaca and surrounding areas, because he was from southern Mexico.

By this time the war was over in Europe, so Calleja retired a year later (1816). His replacement as viceroy came straight from Europe, and for four years the viceroy presided over a country that was mostly pacified, if not unified. The white community continued to be devoutly Catholic, loyal to the crown, and didn't care about Mexico's other ethnic groups.

Suddenly, the movement for independence got support from an unexpected source--the conservatives. Spain's restored king, Ferdinand VII, was too conservative for most of his people. He rejected the liberal constitution that had been imposed on Spain in 1812, and turned against the liberals who had supported him against Napoleon. But while most people wanted to restore the Bourbon dynasty to the thrones of France and Spain; too much had happened over the past quarter century to go back to the old way of doing things. In 1820, a group of soldiers in Cadiz, Spain, were about to be shipped across the Atlantic, to help put down the rebellions in South America. Instead, they chose to mutiny, and their leader announced that he was doing it because he supported the 1812 constitution. Because of that announcement, the mutiny quickly spread to soldiers in other parts of Spain, and in no time the king was forced to reinstate the constitution, to avoid being toppled in a liberal revolution.

The current viceroy in Mexico, Juan Ruiz de Apodaca, responded by implementing an abridged version of the 1812 constitution. This failed to win over those who wanted reform or revolution, and it alienated the conservatives, who now feared that Europe's liberal contagion would spread to them. When he sent a royalist officer, Colonel Augustin de Iturbide, to put down the rebellion in the south, Iturbide went over to the rebels instead. To the rebel leader Guerrero, he presented the Plan of Iguala, which offered what he called the “Three Guarantees”:

- Mexico would become an independent monarchy, ruled either by King Ferdinand or another prince from the Bourbon family.

- The Creoles and Peninsulares would have equal rights and powers in Mexico.

- The Roman Catholic Church would remain the state religion.

The new state started out with awesome potential, more than any other ex-Spanish colony. To start with, it was more than twice of the size of present-day Mexico. An expedition to Guatemala and El Salvador in 1822 conquered that region before it could declare independence. Now Mexico had landholdings that included all of Central America except Belize and Panama, and a northern border at latitude 42° N., which gave Mexico the future states of California, Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Texas, with part of Colorado and Wyoming thrown in.(55) In addition, Mexico had half the population and half the wealth of Spanish America. So why did the Yankee republic go on to become a superpower, while Mexico didn't? Mainly because of bad government south of the border, and that started with Iturbide, who we saw was a reactionary. He allowed the establishment of an independent Mexican congress, but when he saw congress taking his power away, he decided it was time to crown the promised monarch, and he did not look very far to find one.(56) On May 18, 1822, he ordered his men to march through Mexico City in support of him. As hoped, many civilians joined the soldiers on the way, and when they all reached Iturbide's home, they shouted, “Long live Agustín I, Emperor of Mexico!” Iturbide gracefully acted like it was a surprise, and one day later, the congress proclaimed Iturbide a constitutional emperor. The following July, Mexico City had the dubious honor of watching Iturbide's coronation.

Iturbide's reign was mercifully short. In August 1822, Iturbide and the last Spanish viceroy, Juan O'Donojú, signed the Treaty of Cordoba, which recognized both Mexican independence and the Three Guarantees. Then opposition to Iturbide came out of the woodwork. He faced serious economic problems when he canceled several colonial-era taxes, to increase his popularity, but insisted on a large and very-well-paid army and an extravagant salary for himself. When he tried to fix this by imposing a 40 percent property tax on the elite, his base of support turned against him, and because many members of congress wanted to see a republic instead of a monarchy, he closed congress and started arresting the opposition. Then the army turned against him, when the money needed to pay the troops ran out.

The most important rebel opposing the emperor was Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna Pérez de Lebrón, the leader of the Veracruz Garrison (we'll just call him Santa Anna after this). In February 1823 he began to march on Mexico City. Iturbide went out to meet him an March, and abdicated when he realized that almost nobody was on his side. He went into exile, first in Italy and then in Britain, came back in early 1824 when he thought there were calls for his return, but within five days he was arrested by the governor of Tamaulipas (the state where he landed), tried and shot. Meanwhile, Santa Anna entered Mexico City without resistance, and set up a republic in place of the empire. During the next year and a half the central government saw six presidents rise and fall, including the former rebel leaders Guerrero and Victoria. To the south, Central America declared independence in July 1823.

Iturbide's opponents only stayed united for about four years. Conservatives still felt that a monarchy was the best political solution for Mexico; both they and European-born whites were accused of favoring a return of Spanish rule. A conservative rebellion was defeated, and then a liberal coup in 1828 overturned the latest election results. Vicente Guerrero became the next president, and the first thing he did was order all Spaniards still living in the republic to leave. Spain's King Ferdinand responded by trying to reconquer Mexico; in 1829 a Spanish force sailed from Havana and landed at the Gulf Coast port of Tampico. Like Napoleon's force in Haiti, these troops quickly fell ill from tropical diseases, and then Santa Anna arrived on the scene with a Mexican army to throw them back into the sea. Santa Anna became the hero of the hour not only because he stopped the invasion, but also because he did it with only weapons and funds from his home state of Veracruz (President Guerrero gave him no support because he feared that Santa Anna could be as dangerous as the Spaniards). Then in 1830 Guerrero was in turn toppled by another coup, this one led by a conservative, Anastasio Bustamante. When Guerrero revolted against the new regime, he was captured and executed; this would poison relations between the political factions, leading to more unrest during the next decade.

Brazil: Independent By Accident

Brazil became independent not so much from a revolution as from a divorce, the separation of the king of Portugal from his son. Since 1788, the Portuguese Empire had been jointly ruled by Dom Joao (John VI) and his mother, Maria I. Although John was twenty-one years old at the beginning of his reign, and thus old enough to rule on his own, he was weak-willed and dominated by both his mother and by his wife, Charlotte of Spain; he did not even take the title of king while his mother was alive, calling himself the Prince of Brazil and the Prince Regent instead. What made this a bad arrangement was that the queen mother was barking mad, and everyone knew it; visitors to her palace complained of the terrible screams they heard.(57) Fortunately, having a dysfunctional royal family was all right as long as nothing else was happening in the empire; unfortunately, Portugal's long peace would end in Maria's lifetime.

Portugal had been an ally of Britain since the fourteenth century, and that did not sit well with Napoleon Bonaparte; in April 1801 he persuaded Spain to invade Portugal. This brief conflict is sometimes called the War of the Oranges because after the key battle, the Spanish commander picked two oranges and sent them to the queen of Spain, with a romantic note that said, “I lack everything, but with nothing I will go to Lisbon.” For Spain it was a walkover; in June Prince John and Spanish representatives signed the Treaty of Bajadoz, which called for giving the disputed border town of Olivença to Spain, the closing of Portugal's ports to British ships, the payment of indemnities to Spain and France, and the surrender of the South American lands north of Brazil to France. But Portugal did not stay subdued; after the famous battle of Trafalgar (1805), relations with Britain were restored. Napoleon would not stand for any violation of his economic blockade of Britain (the “Continental System”), so in 1807 he invaded and conquered Portugal. On November 29, 1807, one day before the French entered Lisbon, the Portuguese royal family and court, about 2,000 people in all, escaped in fifteen ships, escorted by British warships.

They decided to go to the largest colony of the Portuguese Empire--Brazil. The convoy reached the port of Bahia on January 22, 1808, and continued on to Rio de Janeiro, arriving on March 7. It had been an extremely uncomfortable voyage for everyone, especially the queen mother. Once there they hastily transformed Rio from a provincial capital into an imperial one, building printing presses, a national bank, a royal treasury, a library, medical schools and military academies. Also important, most of the restrictive laws that had channeled trade to Portugal were removed; now Brazil was free to trade with other countries, especially the United Kingdom. This was the only time in history that an Old World nation was ruled from the New World, and residents of Rio de Janeiro rejoiced at the sudden change in their status. In 1816 the Portuguese even took advantage of the current anarchy in the Spanish colonies, by conquering the disputed Banda Oriental province in the far south, and renaming it Cisplatina (“This Side of the Plata River”).

Arthur Wellesley, the future Duke of Wellington, landed a British army in Portugal in 1808, to begin the task of chasing the French out of both Portugal and Spain. He liberated Lisbon in the same year, but it was not considered safe for the Portuguese royal family to return, so they stayed in Brazil for the rest of the Napoleonic Wars. Even after Napoleon fell at Waterloo, the Prince Regent wasn't in a hurry to go back; one year later (1816) the queen mother died, and the Prince Regent finally proclaimed himself King John VI.

Part of the reason why the royal family vacillated was because the calls for them to return to Portugal were matched by equally loud calls to stay put. Because Brazil had far more resources than Portugal, it made sense to have the empire's capital in Brazil, and many Brazilians liked the new arrangement; they weren't really in charge now, but having the court in Rio let them think they were running the show. But note that I said “many Brazilians,” and not “all Brazilians.” A lot of colonists at this point did not see themselves as Brazilians, as much as they saw themselves as residents of whatever province they came from. Those in the outlying provinces were beginning to resent the way Rio de Janeiro dominated the rest of Brazil. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, tensions were rising, too; Portugal needed to be rebuilt after all the damage it had suffered in the Napoleonic Wars, and the king wasn't there to oversee this work. John tried to head off trouble in 1815 by changing the official name of the empire to the “United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves,” meaning that henceforth Brazil would no longer be a colony, but have equal status with the mother country. It didn't work; in 1817 a revolt broke out in the province of Pernambuco, and it took three months to put it down. This was matched across the ocean by a mutiny of Portuguese troops in Oporto (August 1820), very much like the Spanish uprising in Cadiz, eight months earlier. The troops demanded that the king return to Portugal, and set up an elected parliament called the Cortes; this would effectively make the Portuguese king a constitutional monarch. To keep his throne in Portugal, the king would have to go back, so he gave in to the demands and returned, in April 1821. To maintain the balancing act on both sides of the Atlantic, he put his twenty-two-year-old son Dom Pedro in charge of Brazil, and left him with these words, “Since they want a king of their own, it had better be you.”

The stage was set for a three-sided struggle, with the Cortes of Portugal on one side, and Dom Pedro and Rio de Janeiro on the second side. For the third faction, juntas seized power in several Brazilian provinces to challenge the authority of Rio, Lisbon, or both. Then in August 1821, to keep Dom Pedro from leading Brazil to independence, the Cortes ordered him to return to Portugal. To everyone in Brazil, this was taken as a sign that Brazil would be returned to its pre-1807 status, as a colony of Portugal. The result was a nearly unanimous protest against the order; maybe cities like Sao Paolo and Bahia didn't want to take a back seat to Rio, but they liked the idea of knuckling under to Lisbon even less. Dom Pedro agreed with the Brazilians, and on January 9, 1822, he announced he would not leave: “As it is for the good of all and for the nation’s general happiness, I am ready: Tell the people that I will stay.” The Lisbon government had provoked precisely what it feared the most.

Before the month was over, Dom Pedro formed a new government, with José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva as the chief minister. Because Bonifácio was older and a good source of advice, he and Dom Pedro became the best of friends. In February the local garrison of 2,000 Portuguese troops rioted, and was surrounded by 10,000 Brazilians; Dom Pedro fired their commanding general and politely ordered them to go back to Portugal. To satisfy liberals who might have preferred a republic, Dom Pedro decreed in June that he would allow elections for a constituent assembly. Then on August 25 he left for Sao Paolo, to make sure that Brazil's second largest city was on his side. He left Bonifácio in charge of the government in Rio, but while he was away, the Cortes annulled all acts from the Bonifácio cabinet and removed its political power. When he heard the news, Dom Pedro turned to his entourage and said, “Friends, the Portuguese Cortes want to enslave and pursue us. From today on our relations are broken. No ties unite us anymore.” He removed the blue and white armband that showed his loyalty to Portugal and continued: “Armbands off, soldiers. Hail to the independence, to freedom and to the separation of Brazil.” Then he drew his sword and shouted, “For my blood, my honor, my God, I swear to give Brazil freedom. Independence or death!” Because this dramatic event happened on the banks of the Ipiranga River, it is now called the “cry of Ipiranga.”

Dom Pedro and his followers reached Sao Paolo on September 7, 1822, and that was where he officially declared the independence of Brazil. He seemed to be a reluctant leader, though; once he offered to step down if John VI came to Brazil again (he probably felt he was in rebellion against the Cortes, but not against his father). In Sao Paolo he also accepted the idea from liberals that he should be a constitutional emperor, rather than a king. So on December 1, after he returned to Rio, he was crowned Emperor Pedro I.

The coronation of Pedro I.

The main task left was to get rid of the Portuguese troops still in the ex-colony. There were a series of small battles in the following year, mostly in Bahia, Cisplatina, Rio de Janeiro and on the Amazon River. For the naval battles, Brazil got help from Britain's Admiral Cochrane, now that he was done helping the Spanish colonies win their freedom. There were some acts of sabotage from Portuguese citizens who served in the British navy, until they were replaced by Brazilians and foreign mercenaries. On land, the Portuguese soldiers were on the defensive, after they failed to win over those Brazilians who might have preferred Lisbon to Pedro I. By November 1823, the last of them had been rounded up. Estimates of those killed in action on both sides range from 5,700 to 6,200, meaning that Brazil's war for independence was almost bloodless, compared with the other wars for independence in the western hemisphere.

The reason for the small number of deaths was the easy-going Portuguese attitude; people of Portuguese ancestry found it easier to reach a compromise than those of Spanish ancestry did. It also meant that Pedro I would succeed in keeping the Portuguese-speaking provinces together long enough to form a single permanent, Brazilian state, instead of seeing each province go off in a separate direction, the way the Spanish colonies had. In May 1824 the United States became the first foreign nation to recognize Brazil, and Portugal did the same in 1825. The Brazilian emperor had accomplished everything for Portuguese America that Bolívar wanted to do for Spanish America, and he did it with astonishing ease.

Unlike most of its Spanish-speaking neighbors, Brazil had experienced administrators, political stability, freedom of speech, a bicameral legislator that had been created by a free election, respect for civil rights and vibrant economic growth. Despite this great start, the new nation had its share of problems. One was the relationship between native-born Brazilians and those citizens who had moved from Portugal since 1807, which resembled the rivalry in the Spanish colonies between the Creoles and Peninsulares. Like the Peninsulares, the new arrivals felt they should have the lion's share of the power and privileges.

Another problem was the emperor himself, who proved to be incompetent as the 1820s dragged on. In 1823 José Bonifácio de Andrada and the constituent assembly produced a constitution which limited the powers of the emperor and his Portuguese advisors, arguing that the people will only accept an emperor if they see in writing what the emperor can and cannot do. At first Pedro dissolved the assembly and exiled Bonifácio, but then in 1824 he decided they were right and accepted the constitution; that would be the law of the land for the next sixty-five years. When John VI died in 1826, Pedro succeeded to the Portuguese throne, only to find out that he couldn't be king of Portugal and stay in Brazil at the same time.(58) After two months of trying to keep the crown for himself, he gave it to his daughter, Maria II, but that didn't work, either; in 1828 his younger brother Miguel seized power in Portugal.

Meanwhile to the south, there was the Argentina-Brazil War. Brazilian troops could not keep a firm grip on the non-Portuguese Cisplatina province, and in 1825 a group of revolutionaries, known as the Thirty-Three Easterners, boarded two boats in a suburb of Buenos Aires, crossed the Uruguay River, slipped past the Brazilian navy, landed on the east bank, planted a flag with blue, white and red horizontal bars, marched to the nearest city, Montevideo, and established a provisional government. Later in the same year, at the town of La Florida, a congress of delegates representing the local population declared independence from Brazil. Brazil declared war, as one might expect, and United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata sent troops to help the rebels, with the intention of annexing the territory if it got the opportunity. 1826 and 1827 saw a series of battles that were inconclusive, and mostly small (see footnote #49); the largest battle, Ituzaingó, was against two armies that each had between 7,000 and 9,000 men. Then in 1828 the British intervened, because the war was hurting trade in the Rio de la Plata region, and they helped Brazil and Argentina to negotiate the 1828 Treaty of Montevideo, which declared that neither of them would get the disputed province; instead it would become the independent republic of Uruguay. That wasn't the end of the story, though, because two political parties quickly formed in Uruguay, one pro-Argentine and the other pro-Brazilian; we'll get back to them in the next chapter.

Domestically, Pedro was accused of mismanaging the economy; the national debt and prices went up, while the value of money went down. The production of tobacco, leather, cocoa, cotton, and even coffee declined, too. On top of all that there were reports of the emperor chasing women and having more than one illegitimate child, which shocked even Brazilians who tolerated such affairs. Gradually all this bad news prompted conservatives and the army to distance themselves from the emperor, leading to his abdication in 1831.

All Roads End At Ayacucho

Jose de San Martin reached Guayaquil on July 26, 1822. However, Simón Bolívar beat him there, and had annexed the port to Ecuador thirteen days earlier; he was not in the mood to grant concessions. The two men met privately for two days. What they discussed was not recorded, but it's a safe bet that one of the topics was who would rule South America. They probably could have shared rule, due to San Martin's temperament. Always the more practical of the two, San Martin had shunned glory; in Buenos Aires he was willing to take a secondary position, under men he overshadowed.

Bolívar meets San Martin.

But it was not to be, no agreement was reached between them. In fact, their talks caused San Martin to get out of politics--and South America--completely. A ball was held in their honor after the meetings; while Bolívar had a great time, San Martin looked depressed. At 1 AM San Martin called his aides, told them he could not stand the noise any longer, quietly slipped out, went to his ship (which already had his luggage on board), and sailed south. In Lima he found a revolution had occurred while he was away, so he resigned his supreme command and left the country. When asked why he did this, all San Martin said was, “I am tired of being called a tyrant.” He went to Europe, and came back in 1829, but was so disgusted at the state of anarchy in Argentina that he refused to step off the boat, and went to Europe again. There he lived to a ripe old age, dying in Boulogne, France in 1850.

San Martin's departure meant that Bolívar would have to finish the job of clearing the royalist troops out of Peru, and he would have to do it without help. San Martin's army had dissolved after their leader resigned; Admiral Cochrane had taken his fleet to harass Spanish shipping elsewhere, now that he was no longer needed around Peru. South of Peru, Chile was in turmoil. Bernardo O'Higgins had earned praise by defeating royalists and building schools, but while he was a pleasant man, he was also an incompetent politician. Like Bolívar, O'Higgins thought he could create an ideal society through the use of strong government, in effect forcing the people to be free. “If they will not become happy by their own efforts,” he once said, “they shall be made happy by force, by God they shall be happy.”

To make everyone happy, O'Higgins abolished titles of nobility, confiscated royalist land, and reformed the tax system to pay for his improvements on the infrastructure. But at the same time he managed to offend everybody; he alienated liberals and provincials with his authoritarianism, conservatives and the church with his liberalism, and landowners with his proposals for more land reform. In addition, he continued to support San Martin's campaign in Peru, because he felt that Chile would not be safe until the Spaniards had been cleared out of all neighboring lands, while his opponents thought that Chile could not afford to fight a foreign war. In October 1822 he proposed a constitution that would give him virtually dictatorial powers for ten years, and that was the last straw; one year later the army forced O'Higgins to abdicate and flee to Peru, where he lived embittered until his death in 1842.

The rest of the 1820s saw a series of generals trying to impose order on a disunited country. A military expedition succeeded in capturing the Chiloé islands, which were under royalist control until 1825, but otherwise the Chileans were too busy fighting each other to participate in the Latin American revolution anymore. Two new factions arose, the liberal Pipiolos and conservative Pelucones, which absorbed the followers of O'Higgins and his rivals. From 1823 to 1827 the presidency was usually in the hands of Ramón Freire, the general who liberated Chiloé and the leader of the Pipiolos. Freire's main achievement was the abolition of slavery in 1823, long before slavery was abolished in most of North and South America. However, from May 1827 onward, the presidency alternated between Freire and his former vice president, Francisco Antonio Pinto; Pinto and Freire each ruled for part of 1828 and 1829. Thinking that Chile's federal system was responsible for the current troubles, Pinto replaced it with a unitary government in August 1828. But the constitution he accepted to go with the government angered both federalists and liberals. Then, like O'Higgins, Pinto managed to turn everyone else against him; aristocrats were offended when he abolished the practice of bequeathing estates to the landowner's eldest son (primogeniture), while the Church was offended by anticlericalism. By 1829 the country was in a state of civil war. This went on until the battle of Lircay (April 17, 1830), in which the conservatives triumphed and Freire, like O'Higgins, went into exile in Peru.

Meanwhile to the north, Bolívar began his Peruvian campaign by sailing to Lima in August 1823. He found Peru's political and military condition in as bad shape as Chile's, and wrote, “The country is afflicted by a moral pestilence.” One Peruvian president, José de la Riva Agüero, had been accused of treason by another, José Bernardo de Tagle, and was exiled to Chile. In addition, there were two powerful, undefeated Spanish armies, currently based near Cuzco; fourteen thousand soldiers under General Jerónimo Valdez, and six thousand soldiers under General José de Canterac. By February 1824, when a desperate parliament officially appointed Bolívar dictator of Peru, he found that the republic controlled only one coastal province.

Bolívar and General Sucre went to work raising a new army, and in June 1824, when they had a force of nearly 10,000, they were ready to move into the Andes. In August they defeated the Spanish cavalry at the battle of Junin, and it looked like the war's ultimate victory would soon follow. However, the republicans were interrupted first; when Bolívar was at the gates of Cuzco, he received an order from the Colombian parliament to resign from his command. Bolívar never found out who was responsible, but he suspected Vice President Santander had gotten jealous of him; he withdrew to Lima to take out more loans for the war effort, and to receive a unit of 4,000 men sent by General Paez from Venezuela (they would arrive after Ayacucho).

Sucre led the army by himself to the site of the final showdown, which appropriately had the Indian name of Ayacucho – the Corner of the Dead (December 9, 1824). Estimates of the number of troops involved on both sides range from 12,686 to 17,810. 1,800 royalists were killed and 700 wounded, compared with 370 republicans killed and 609 wounded. The royalists lost almost all of their veterans, meaning they could not continue the fight after the battle, and Viceroy la Serna was among the wounded, so the second in command, José de Canterac, surrendered what was left of the royalist army.

There were still Spanish soldiers garrisoned in Upper Peru, but after Ayacucho the will to fight was gone. Sucre advanced into Upper Peru, and after one more battle (at Tumusla, April 2, 1825), those Spaniards surrendered to him. All that remained were some royalist soldiers besieged in the fortresses at Callao, Peru; they held out until 1826. The liberation of Latin America's mainland was complete; except for the islands Spain still held in the Caribbean, the story of the Spanish Empire in the New World had ended.

In August 1825, Upper Peru declared its independence, first calling itself Republica Bolívar, and then simply Bolivia, with Sucre as the first president. Bolívar was flattered to have a country named after him, of course, but he would have preferred to see Bolivia remain part of Peru. Then when he arrived in La Paz, the outpouring of love from the crowds toward him was so touching that he decided independence for Bolivia wasn't a bad idea after all. In October, he and Sucre climbed Mt. Potosi (see Chapter 2, footnote #39), and placed the flags of Gran Colombia, Peru, Chile, and Argentina on the summit, a symbolic gesture to show that the war against Spain had been won. To his staff Bolívar announced, “In fifteen years of continuous and terrific strife, we have destroyed the edifice that tyranny erected during three centuries of usurpation and uninterrupted violence.”

Now that the military struggle was over, Bolívar faced an administrative struggle, to set up efficient, stable governments in the countries he had freed. He was now ruler over the lands that would become the present-day nations of Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela and Panama, and was very influential in Bolivia as well. He wanted them to unite to form a great nation, just as the thirteen English-speaking colonies that revolted against Britain in North America had merged to create the United States. But this was a struggle that could not be won by fighting battles or writing manifestoes--even speeches could only help so much--so it was a struggle the Liberator would ultimately lose.

The Falklands Dispute Begins

In 1820, storm damage forced the privateer Heroína to take shelter in the Falkland Islands. The ship's captain, David Jewett, raised the flag of the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata and claimed the islands for that new nation. Buenos Aires didn't know it had a claim to the islands until nearly a year later, when Jewett's declaration was published. To colonize the place, the Argentines sent Luis Vernet, a merchant from the German port of Hamburg, in 1828, telling him that he was now governor of East Falkland, and if he could establish a colony there within three years, it would be tax-exempt. However, Vernet knew that the British had a claim to the islands, too, so he also sought permission from them to found a colony. The British agreed, but since he was getting a better deal from the Argentines, the colony he set up, at Puerto Soledad (the name was soon changed to Puerto Luis), was declared an Argentine one.

Britain protested, and so did the United States when Vernet banned fishing and seal hunting by all other nations in Falkland waters. After Vernet seized some American fishing boats, the American corvette USS Lexington destroyed the Puerto Luis settlement in 1831. Vernet left the islands, and Buenos Aires sent a new governor, Major Esteban Mestivier, but when he arrived his soldiers mutinied and killed him. One month later (December 1832), two British ships dropped anchor at Port Egmont, repaired the fort, and fixed a notice of possession on it. On January 2, 1833, they arrived at Puerto Luis and demanded that the Argentine flag be replaced with the British one. The Argentine commander, Lt. Col. José María Pinedo, found himself in a hopeless position; not only did the British ships have more troops, but 80 percent of his own force was made up of British mercenaries, which he could not trust in the event of a fight. Thus, Pinedo left, and a British governor arrived in 1834. Since then, except for a brief period of Argentine rule in 1982, the Falklands have been a British colony.

The Shattered Dream

Bolívar greatly enjoyed his sojourn in Bolivia. He acted as an elder statesman to the new republic, giving advice to its leaders on various subjects, from agriculture and commerce to hygiene and the raising of llamas. To set up an education program, he called in his old tutor, Simon Rodriguez.(59) He also wrote the Bolivian constitution, which he considered his greatest contribution. This was a highly personal document; it guaranteed human rights and abolished slavery, but it also put a president for life in charge of the state, and he could appoint his successor. Bolívar did this because he wasn't thrilled with democracy anymore, and felt that elections “produce only anarchy.” It never went into effect in Bolivia, because Bolívar had to leave after he finished it, but he persuaded Peru to adopt it, and urged Gran Colombia to do the same. At one point he wildly claimed, “Everyone will consider this constitution as the ark of the covenant,” but to those who did not support him, it reminded them more of the golden calf.

Now that all of South and Central America were free (except for a few non-Latino enclaves like Belize and the Guianas), Bolívar's next dream was to enroll all those new countries into a league of nations. Like the recently established Holy Alliance in Europe, and the future Organization of American States, this league would settle disputes between its members and provide a common defense; he also wanted it to abolish racial discrimination. Bolívar decided to hold the league's first meeting in Panama, and invited all the former Spanish colonies, Brazil, Britain and the United States to send delegates.

So how did the “Congress of 1826” go? Not too good! Once they became independent, most of the new nations were only interested in their own problems, and did not care about the problems of their neighbors. Not every nation sent delegates; some sent their delegates too late to attend the meeting; the United States representative died on the way. The only nations that took part in the meeting were Mexico, Central America, Gran Colombia, and Peru. Bolívar was not there, which shows that even he gave up thinking that the resolutions passed by the congress were important.

Bolívar could not stay in Bolivia, because he was technically the head of state for both Peru and Gran Colombia, so in 1826 he went back the way he came, going first to Lima, and then heading north to Bogota. By the time he arrived, relations between Vice President Santander and General Paez had gotten so bad that Paez launched a revolt from Venezuela. Santander had refused to send men and supplies while Bolívar was campaigning in Peru, so Bolívar took the side of Paez, dismissed Santander and granted a general amnesty to the Venezuelan rebels. But that only alienated the New Granadans, so Bolívar called for a constitutional convention in April 1828. The delegates met for two months, but when it looked like they would produce a constitution for a loose, federal state, instead of the centralized one that Bolívar preferred, Bolívar's delegates walked out, making it impossible for the remaining delegates to finish. Then Bolívar made himself dictator of Gran Colombia--but only as a temporary measure, until order could be restored and the new constitution established. Liberals saw it differently, though, because Bolívar talked about imposing “inexorable laws.” His enemies burned him in effigy in the streets, and the nation was on the brink of civil war as long as he was in charge. In September 1828, Santander engineered a plot against Bolívar's life, and when it failed, he resigned and went into exile.(60)

Meanwhile in Lima, the New Granadan troops Bolívar had left behind mutinied against their Venezuelan officers, shipped the officers to Guayaquil on a chartered vessel, and went home. Next, the Peruvian politicians spontaneously rejected both Bolívar and his constitution, and set up a new republic that promised a new constitution by 1833. A Peruvian general, Agustín Gamarra, even invaded Bolivia to throw out General Sucre. And as if that was not enough insult and injury, Peru invaded Ecuador, because of a dispute over where Peru's northern border actually ran (the Gran Colombia-Peru War, 1828-29). The Peruvian navy captured and nearly destroyed Guayaquil, but Sucre, now in charge of the Gran Colombian army, successfully defended Ecuador against Peru's land invasion, so the war ended as a stalemate, with the Peruvian-Ecuadorian border unchanged. Even so, General Paez took advantage of the situation to declare Venezuela independent of Gran Colombia, with himself as its first president. Bolívar's dream of a Latin American superstate was fading fast.

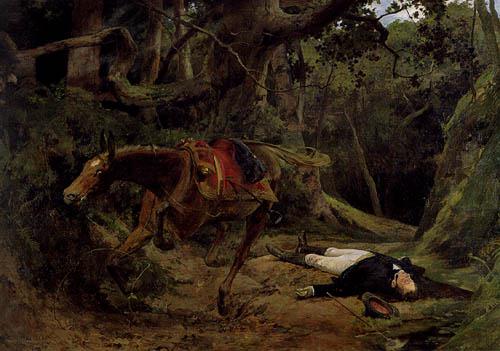

After that, Bolívar remained in power for another year and a half. During that time, his popularity declined and his health deteriorated. New Granada's generals and politicians came to see him as a liability, while liberals still feared he would become a tyrant. In April 1830, ill from tuberculosis and exhausted, Bolívar resigned, and decided to retire to Europe, the way San Martin had done. He and his entourage moved slowly toward New Granada's northern coast. On the way they received two more pieces of very bad news. The first was that some Ecuadorian officials met in Quito and declared Ecuador's independence, thereby dissolving the union of Gran Colombia.(61) The second was that Sucre had been murdered on a mountain road in southern Colombia. Sucre's killer or killers were never caught, but it is thought that Sucre was assassinated because he was likely to become the heir of Bolívar, and a lot of people didn't want that by now.

The death of Sucre.

Bolívar's despair at the failure of his life's work shows in his last political statement. One month before his death he wrote, “America is ungovernable. Those who serve the revolution plow the sea. The only thing to do in America is to emigrate.” But he was denied even the opportunity to leave. Although a ship carrying most of his belongings was sent ahead to France, he only got as far as the coastal town of Santa Marta before he died on December 17, 1830, at the age of forty-seven. On his deathbed, Bolívar asked General O'Leary to burn all of his writings, letters, and speeches, but O'Leary disobeyed the order, so the extensive archive of what Bolívar wrote during his life is still available. In fact, shortly before her death in 1856, Manuela Sáenz (see footnote #60) gave O'Leary her own letters from Bolívar, too. Bolívar was initially buried under the local cathedral, but twelve years later, when the Venezuelans were no longer mad at El Libertador, Paez arranged to have his body moved to Caracas and reburied in his native land.

The peoples of Latin America had kicked out their European masters, only to find out that they had not solved their problems. In place of European-born whites, American-born whites now ran the show, seizing the land that had previously belonged to the European-born, and usually managing it the same way, in the form of huge plantations; previously promised land reforms were often forgotten. Nonwhites, especially the Indians, were no freer than before, though most of them were now officially citizens of a republic. All of the new nations, at one time or another, had leaders who felt they should be more than just presidents. Usually that meant military dictators, known as caudillos; those strongmen will dominate the narrative for the rest of this work. The most disturbing part was that many of them drew their inspiration from Bolívar, arguing that like him, they believed their countries needed a head of state who served for life.(62)

Latin Americans also continued to be exploited by the Old World, only now it was done indirectly. For those who worked in mines and on farms, the physical chains of slavery were replaced by the economic chains of debt and obligation.