| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 15: THE GREAT INTERMISSION

1919 to 1939

This chapter covers the following topics:

Disillusionment at Versailles

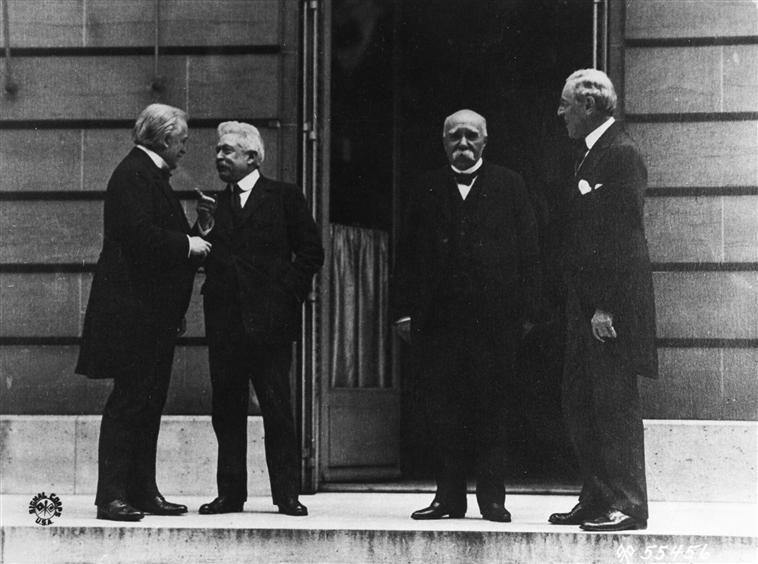

In January 1919 the Allied leaders met at Versailles, France, and the peace conference began. Although dozens of nations sent representatives, the conference was almost from the start dominated by four personalities: US President Woodrow Wilson, French Premier Georges Clemenceau, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando. And soon the meetings between the "Big Four" became a contest of willpower between Wilson and Clemenceau. Wilson, an idealist who believed in extending American values to the rest of the world, talked a lot about "peace without victory" and making the world safe for democracy; he came to Versailles with a fourteen-point plan for permanent peace and thought that the treaty they finally produced was too hard on Germany. Clemenceau, on the other hand, wanted to make the world safe for France; he had seen his country invaded by Germany twice during his long lifetime, and thought that the terms imposed were too soft. The final treaty included Wilson's fourteen points, but the rest of the document was more Clemenceau's doing. At one point Clemenceau accused Wilson of acting too much like a messiah, remarking dryly that his fourteen points were worse than the commandments God Almighty had given, because the good Lord only had ten!

The Big Four. From left to right: David Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, Georges Clemenceau, and Woodrow Wilson.

In mapping terms the biggest challenge facing the diplomats was carving up the defunct Austro-Hungarian empire. This understandably led to bickering among the successor states--Czechoslovakia, Poland, Austria, Hungary, Romania, Yugoslavia(1) and Italy. The Hungarians even tried fighting to regain Transylvania and Slovakia, which had been theirs before the war. Their resistance, however, was quickly broken by the Romanians, who occupied Budapest in August.(2) By October, apart from four sectors where the final line was to be determined by plebiscites, agreement had been reached on nearly all the new boundaries.

An important exception was the "Adriatic Question," which asked where the frontier would run between Italy and the new Yugoslavia. As soon as Austria-Hungary surrendered, the Allies sent troops to the eastern shore of the Adriatic, to act as peacekeepers. The British and Italians jointly occupied the northern third of this area; American soldiers, based in the town of Split, occupied the central third; the French occupied the southern third (the coast of Albania). When it came to drawing the future border, the Italians wanted all of Dalmatia because the Republic of Venice once had it, though hardly any Italians lived there now. And during World War I, the British and French, while trying to persuade Italy to join them, said Italy could have it; the 1915 Treaty of London put this down in writing. But the treaty did not carry any weight with President Wilson; as far as he was concerned, the line between Italian and Slavic-speaking communities was where the political line was going to be, and token concessions were all that Italy could expect. Sure enough, when the final border was drawn, the Italians got all of Istria and the Yugoslavs got all of Dalmatia except for the port of Zara, which went to Italy, while Fiume eventually became an independent "free city." (see the next section)

Where Wilson compromised his self-determination principle was in cases where physical geography mattered more than ethnic details. For example, he let the Italians have the watershed line in the Alps, because there were Italians living in the southern Tyrol; however, there were a quarter million Austrians in the area as well. And he agreed that the frontier between Czechoslovakia and Germany should follow the mountainous rim of Bohemia (the Sudetenland), though the two million Germans on the Czech side of the line were horrified at the idea. In the west, the population of Alsace-Lorraine was 87 percent German, but the Allies agreed that it should be given to France, because the French had wanted it back since the Germans took it from them in 1871.

The exceptions had one important feature in common: they allowed politicians in the defeated nations to argue that the Wilson doctrine operated in the Allies' favor. There were Germans in Czechoslovakia but no Czechs in Germany; there were Austrians in Italy but no Italians in Austria; the cession of Transylvania to Romania, with its mixed Hungarian-Romanian population, meant that there would be Hungarians in Romania but no Romanians in Hungary; the return of Alsace-Lorraine meant there would be Germans in France but no French in Germany. However, the most glaring infringement of the self-determination principle came when impoverished Austria asked to join Germany, and the Allies refused to allow the union. One can see the Allies' point of view--a defeated Germany could not be allowed to come out of the war bigger than before--but it did make some of the other things they said sound hypocritical.

The Germans, of course, pointed out this inconsistency. When they signed the Versailles Treaty, they said quite openly that they were doing so under duress. Indeed, the place chosen for the signing, the Hall of Mirrors, was an act of revenge; the previous war between Germany and France had ended in the same place. But really they didn't do too badly, particularly if you consider the kind of treaty they would have forced the Allies to sign had they won (remember Brest-Litovsk). Besides ceding Alsace-Lorraine to France, they had to hand over two largely Polish provinces to Poland (Posen & West Prussia); finally, two German ports on the Baltic, Danzig and Memel, were made into free cities. But the other territories that France and Poland asked for, Wilson put to plebiscites, with the result being that all of them except northern Schleswig and the tip of Silesia returned to Germany.(3)

Bulgaria's losses were proportionately about the same as Germany's: she had to return the southern Dobruja to Romania, give western Thrace to Greece, and make some small adjustments in Yugoslavia's favor. The Ottoman Empire got the same treatment as Austria-Hungary: it was completely dismembered. The Allies drew up for the Turks a treaty just as crushing as Versailles, the 1920 Treaty of Sevres, but it never went into effect. It was rewritten with Greek and Turkish blood (the Greco-Turkish War of 1921-22), with the end result being that Turkey lost its troublesome Arab provinces but conceded nothing else. The Turks recovered their strength with such astonishing speed that the Allies decided to leave them alone and let their first president, Mustafa Kemal, pursue his program to make Turkey a modern, Western republic.

The Free Cities

Danzig, Memel and Fiume were declared "free cities" because the negotiators couldn’t agree on who should own them, so basically they dodged the issue by postponing a settlement of these border disputes. Nowadays we would call this solution "kicking the can down the road," and it wasn’t very successful. With Danzig and Memel, the problem was that these were German seaports, but the new nations next to them, Poland and Lithuania respectively, had no seaports of their own, and a coastline so small that they barely had access to the sea. Lithuania annexed Memel (modern Klaipéda) in January 1923, while the Allies were distracted by their occupation of the Ruhr in Germany. Nevertheless, the Germans would demand Memel’s return at the end of the period covered by this chapter (see footnote #17). As for Danzig (modern Gdansk), it survived as an independent city until the beginning of World War II, but its status was constantly in dispute and this hurt German-Polish relations.

Fiume (modern Rijeka) deserves special treatment, because it became the site of the most bizarre social experiment of the early twentieth century. The city’s population was 46.9% Italian, but there were also a significant number of Croats, Hungarians, Slovenes and Germans, and for most of medieval and modern history it had been ruled by whoever ruled Austria, so the Allies didn’t know what to do with it. The treaty of Versailles assigned it to Yugoslavia (see footnote #1), but the Allies also considered letting it remain as Austria’s last seaport, after nearby Trieste was handed to Italy; US President Wilson even thought about making it the headquarters of his new League of Nations. Meanwhile, Italy claimed the city, because during World War I, more than 1 million Italians had been killed, but as we already saw, Italy had gained only a small amount of territory in compensation.(4)

Into this situation stepped Gabriele D’Annunzio, a free-spirited poet who also happened to be the most charismatic person in Italy. How charismatic was he? Italians already loved D’Annunzio for the poems and novels he had written, so he stopped traffic wherever people recognized him. He could make soldiers and even naval vessels do what he said, using no weapon but his voice. Women risked their marriages, families and careers for a chance to have an affair with him. Casanova was an amateur compared to D’Annunzio.

Anyway, D’Annunzio had joined the Italian army during World War I, though he was already more than fifty years old, and because of his magnetic personality, he was allowed to serve. He became a war hero in 1918, when, as a fighter pilot, he led nine planes in an air raid over Vienna, where they dropped propaganda leaflets on the Austrian capital. On September 12, 1919, he led an irregular force of 2,600 soldiers to seize Fiume, and offered it to Italy. The Italian government refused, choosing instead to go with the decisions of the other Allied nations, and ordered a blockade of the city. Therefore D’Annunzio declared Fiume the "Italian Regency of Carnaro," with himself in charge of it, and proceeded to draw up a constitution. This constitution established a "corporatist state," with nine corporations running different sectors of the economy, and a tenth corporation to rule the others. However, it also declared music as the city-state’s ideology, calling music a "religious and social institution."

And that’s not all. D’Annunzio ruled by combining anarchist, democratic, and proto-fascist ideas. Every morning he read poetry and manifestos from his balcony, and every evening he threw a concert, followed by fireworks. The city came to resemble a hippie commune, fifty years before the hippie movement, where all lifestyles were permitted, so long as nobody got hurt: e.g., recreational drug use, free love, nudism and homosexuality were all widely practiced. Women could vote here, before they got the right to vote in the United States and most of Europe. In addition, non-western religions like Buddhism and Theosophy had followers here.

If all this doesn’t sound wild enough, there was an outbreak of bubonic plague at one point, but fortunately it was stopped before too many people were infected. Because of the blockade on Fiume, the city resorted to piracy to get the supplies it needed; this included raids on trucks and trains, as well as the taking of ships that is normally associated with pirates. To the embarrassment of the Italian government, some ships, like the destroyer Espero, actually mutinied and offered their services to D’Annunzio. When it came to foreign policy, D’Annunzio proposed setting up an alternative to the League of Nations, an international organization for oppressed peoples fighting imperialism, especially the Irish and various separatist groups in the Balkans.

Unfortunately for D’Annunzio, even a person like him couldn’t single-handedly keep a city independent forever. In November 1920, representatives of Italy and Yugoslavia signed the Treaty of Rapallo, which declared Fiume a free city belonging to neither of them. D’Annunzio responded by declaring war on Italy itself. The Italian navy went to Fiume, and when the first ships arrived, D’Annunzio persuaded them not to attack the city simply by speaking from his balcony, but they came back in late December 1920, and bombarded the city from December 24 to 28, only taking time off to observe Christmas on the 25th. Around 50 were killed in the siege, and D’Annunzio surrendered after he asked for, and got, a full pardon for himself and his men. Rome agreed to this amnesty because D’Annunzio wasn’t really an enemy; he had been promoting Italian nationalism all along.

D’Annunzio bought a luxurious villa in Lombardy, and spent the rest of his life there, writing more poems, and still enjoying the companionship of many women, until his death in 1938. He turned down offers from both the Fascist and Communist parties to join them, and after Mussolini took over (see below) this dictator reportedly paid more than one bribe to D’Annunzio, to keep him from getting back into politics. As for Fiume, the early 1920s saw one government after another rise and fall in that city. Then Mussolini decided to annex Fiume, and this was put in writing with the Treaty of Rome, in January 1924. Thus, Fiume was an Italian city until World War II. Upon the war’s end it went to Yugoslavia, which gave it the present-day name of Rijeka; today it belongs to Croatia.

The Irish Free State

One final postwar change had nothing to do with World War I: the independence of most of Ireland (the Irish Free State, or Eire). The Irish republic was born out of a liberation struggle that had been going on for centuries, with the Irish usually making little headway against the hated British oppressor. The seventy years after the Potato Famine saw the rise of several nationalist movements, both Protestant and Catholic; the most important of these was Sinn Fein (Ourselves Alone), founded by the journalist Arthur Griffith in 1905.

By 1914 much of the Irish population was in a serious state of unrest, and they probably would have launched a full-scale rebellion at that time if the Great War had not erupted on the Continent. For a time many put aside their anti-British feelings; 200,000 Irish enlisted in the British army, and 25,000 of them died in the war. The extremists, however, saw Germany as a lesser evil, and to them the war was an opportunity to change the balance of power on the Emerald Isle in favor of the Irish. They began their revolt on Easter Monday of 1916; many of them felt they had no chance of defeating the British, but they participated because they thought their blood sacrifice would bring the rest of the Irish over to their side. Sure enough, by Saturday the uprising was put down, at a cost of 64 rebel lives, 130 British soldiers, and about 300 civilians. Then the British played into nationalist hands by immediately shooting fifteen rebel leaders, thereby killing whatever sympathy they had among the folks in Dublin.

Bad news from the war front prompted Britain to order the conscription of all able-bodied Irishmen in 1917; previously all Irish soldiers had been volunteers. This caused widespread protest and the signing of anti-conscription pledges, forcing London to back down. When general elections were held in December 1918, they showed how much things had changed: Sinn Fein won 73 of the 106 Irish seats in Parliament. Even more amazing was the fact that 34 Sinn Fein candidates were in jail, having been imprisoned for their part in the 1917 protests. Among those who won was a remarkable figure named Eamon de Valera (1882-1975). He had been the last commander to surrender during the 1916 Easter uprising, but unlike his comrades, his death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, due to his American birth (he was born in New York City, to a Spanish father and an Irish mother). Two months after the election, he made his escape, using a key baked in a cake by his friends, and began a fundraising tour in the United States.

Back in Ireland, 1919 began with Sinn Fein setting up its own parliament, the Dáil Éireann, in Dublin, with de Valera as the first president. Britain saw this as an illegal act, and open fighting broke out between the IRA (Irish Republican Army, Sinn Fein's military wing) and auxiliary British soldiers, called the "Black and Tans" because they wore uniforms with a color combination that did not match. This time, war-weariness and Woodrow Wilson's idealism put Britain in a mood to recognize Ireland's right to self-rule. Near the end of 1920, de Valera returned to represent the Dáil in negotiations. The following year saw three quarters of Ireland granted Dominion status within the British Commonwealth, with the IRA leader, Michael Collins, as chairman of the provisional government; meanwhile, the Protestants set up another parliament in Belfast to counterbalance the Dáil.

London felt compelled to hold onto six counties in the northeast corner of Ireland, centered around Belfast. Whereas the rest of Ireland was almost totally Catholic, three centuries of Scottish immigration and missionary activity had converted most of Ulster's inhabitants to Protestantism, and they preferred British rule to becoming a minority in a Catholic country. Until now Catholic nationalists had ignored the wishes of the Protestants, causing much resentment in the north. At first the six counties were given the option of staying with the new Irish Free State or rejoining the United Kingdom; all of them voted to go with the UK.

Predictably, nobody really wanted to divide Ireland into two states, one of them a British province. The result was a new Irish conflict, this time pitting the moderate nationalists, who had grudgingly accepted the deal, against radicals who wanted nothing less than the whole island. The Irish Civil War lasted from April 1922 to April 1923; among its 700 casualties was Michael Collins. De Valera supported the radicals, but in June 1922 new elections put a pro-treaty majority in control of the Dáil, taking away political support for the radical cause. Eventually the moderates got the upper hand, and de Valera called on the anti-treaty militants to surrender. IRA bombings and ambushes continued throughout the 1920s, but because popular support declined, the remaining radicals turned to the north, rather than Dublin, for support and leadership. The inability of all sides to find a solution to Ireland's partition is the direct cause of the violence that occurred later in the twentieth century, as the British army, police and their "Orangemen" sympathizers battled Catholic extremists in Northern Ireland.

The Ex-Monarchs

The most important thing to remember about World War I is that it brought an end to the old game of monarchs playing politics. Four of Europe's most powerful dynasties--the Hohenzollerns, the Hapsburgs, the Ottomans and the Romanovs--were brought down because of this conflict. In all four cases the last emperor went into exile, and there was no throne for his heir. A fifth head of state, Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria, was also forced to abdicate, but his family did not lose the throne right away.

Among the deposed monarchs, Kaiser Wilhelm II did the best; he lived fairly comfortably in exile at Doorn, Holland, where he grew a beard and spent his spare time chopping wood. He was even allowed to keep the family jewels, which included the Hohenzollern crown. In 1940 a new German army crushed the Low Countries and France, and he wrote Adolf Hitler a letter, thanking him for succeeding where he had failed. He felt vindicated when he died a year later, at the age of 82.

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia lived under house arrest for sixteen months, and was transferred from city to city by the Bolsheviks, due to the country's instability during the two 1917 revolutions and the Russian Civil War. When it looked like his final home, Yekaterinburg in the Ural mts., would be captured by anti-Bolshevik forces, local Bolsheviks had the ex-tsar and his family shot (July 1918).

Mohammed VI of the Ottomans got insult as well as injury. The last Turkish sultan had been on the throne for only four months when the Allies took Constantinople. In 1922 he was ousted by Mustafa Kemal; then he tried--and failed--to make himself king of western Arabia after its ruler (the Hashemite sharif of Mecca) was expelled by the Saudis. He died in 1926 at the Italian resort of San Remo.

The Hapsburgs suffered a very similar fate. Karl I tried to hedge his bets; on the day World War I ended, he announced that he would let the Austrian people decide what kind of leadership they wanted for themselves. Then he retired to his private Austrian estates, but instead of voting on whether or not to restore the monarchy, the new Austrian government passed the Hapsburg Law, which ordered that all members of the Hapsburg family either get out of Austria or renounce their claims to the throne. Refusing to formally abdicate, Karl then moved to Switzerland. In 1921 he tried twice to seize power in Hungary, which was now ruled by Miklós Horthy, the last admiral of the Austro-Hungarian Navy. However, Horthy refused to support him, so both attempts failed. The humilated ex-experor was handed over to the Allies, and a British ship took him to the Atlantic island of Madeira, where he died of severe pneumonia a year later, and was buried. As for the last empress, Karl's widow Zita, she lived in seclusion until her death in 1989. In 2004 Pope John Paul II ordered the beatification of Karl I, because his personal life was very pious, but present-day Austria still doesn't want him back, so in the royal Hapsburg crypt under Vienna, the copper coffin with Karl's name on it is likely to remain empty for years to come.

Bulgaria's Tsar Ferdinand moved to Coburg, Germany after abdicating, to stay out of the way of his son and heir, Boris III. Even so, he lived long enough to see the loss of everything that mattered to him. Boris died in the middle of World War II (1943), and was succeeded by Ferdinand's second son, Simeon II. Three years later, the communists took over in Bulgaria; they deposed Simeon, and executed Kiril, Ferdinand's youngest son; then Ferdinand in turn died in 1948. His last request was to be buried in Bulgaria, but with the communists in the way, he was given a temporary grave in Coburg instead. He is still there now; nobody got around to moving him after the Cold War ended.

From Idealism to Upheaval

The Europe created by the Versailles treaty had a lot of medium-sized countries where the prewar empires had once stood: Finland, Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Turkey. Wilson called them the real winners of the war, since most of them chose democratic governments for themselves, but others wondered if this was really a good thing for the stability of Europe. Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia formed an alliance in 1921, called the "Little Entente," to prevent any restoration of Hapsburg power in central Europe. However, none of the new nations could contribute much to defend even its own frontiers, so the responsibility for maintaining peace fell--you guessed it--on the major powers.

Whether they would keep the peace was a good question. Wilson thought the US should lead the way in peace, but the US Senate was tired of Europe; the American soldiers were promptly called home, and the Senate refused to have anything to do with what came out of Versailles. And what was going on in Russia, now called the Soviet Union, made that country so unpredictable that the less the West had to do with it, the better. So the task of keeping Germany in line--a Germany that had been irritated but not crippled by its territorial losses--fell entirely on France and Britain. Could they do it?

The French thought not. After losing a whole generation on the battlefields of Flanders and northern France, they thought that the only way they could cope was to use the advantage of the moment to disable Germany permanently. At Clemenceau's insistence, special clauses were inserted into the Versailles treaty limiting the German army to 100,000 men (seven divisions); other sections of the treaty limited the navy to a few surface ships no larger than cruisers and abolished the air force altogether. And to make sure they would be only used defensively, the army was not allowed to station any troops in the Rhine valley or west of it (the Rhineland). Finally, the German economy was loaded with such a burden of reparations that it was hoped that it would be twenty years before any German could afford to think of guns or glory again.(5)

The British, unlike the French, were vaguely aware that punishing the new, peaceful and democratic Weimar Republic for the sins of the Second Reich could backfire on them. And the more the Germans had to be mad about, the more likely they were to turn to extremist groups. There were plenty of these running around, ranging from communists to ultra-rightist bullies in uniforms. Among the latter was the DAP, the German Worker's Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei). Founded in January 1919, the DAP, as you might guess from the name, promoted issues important to the working class, but unlike other labor parties, it was also anti-Marxist and anti-Semitic. In the 1920s it would change its name to the National Socialist German Workers Party, better known as the Nazis, and then its rise to power in the early 1930s would produce a tyrant without a match in the whole sorry history of inhumanity--Adolf Hitler.

Born in Austria to a customs officer in 1889, Hitler was a never-do-well who originally wanted to become a great artist. He was rejected twice by Vienna's Academy of Fine Arts, leading history buffs to wonder if today's world would be a better place, had the art school given Hitler a chance. I mean, the paintings we have from Hitler aren't very good, but compared to the works of other twentieth-century artists, they don't look bad, either. It only makes sense if the Vienna Academy had higher standards than the art schools of today (e.g., one modern artist who was accepted by the art schools used elephant dung in his pictures!). Another factor in Hitler's upbringing was that while trying to make it in Vienna, he lived in the city's slums, where he was surrounded by non-Germans -- especially Jews.

During his years in Vienna, Hitler drifted from one job to another, took an interest in German nationalism, and decided that the future of the German people lay with the kaiser's empire, not with the feeble Hapsburg monarchy and the multi-ethnic Austrian state. In 1913 he moved to Munich; one year later World War I broke out, and he became a corporal in the German army. Serving on the Western Front, he suffered a leg wound in 1916, was gassed in 1918, and was awarded the Iron Cross for carrying one of his superiors to safety (see also Chapter 14, footnote #10). The war ended with Hitler guarding Russian prisoners in a P.O.W. camp on the Austrian border. After Germany's defeat, there followed for Hitler "terrible days and even worse nights . . . my hatred rose against the originators of this deed."

Since his job prospects were poor, Hitler stayed in the army after the war by joining the Bavarian Army's Intelligence/Propaganda section. In September 1919 this unit sent Hitler to investigate the DAP, by attending one of their meetings. The meeting was held in the back of a beer hall, and about twenty-five people attended (no word on how many came just for the beer). The party founders, a locksmith named Anton Drexler and a journalist named Karl Harrer, were a pair of losers who did not have the skills to lead, nor did they have the resources to put their ideas into action. After listening to the dull discussion for a while, Hitler decided this group was going nowhere, and got ready to leave, when another guest stood up and began making the case that Germany had no future as long as it was dominated by Prussians, so Bavaria should break away and join Austria in a new south German state. Well, Hitler had left Austria because his views were exactly the opposite, so he walked right to the front of the hall and gave an impassioned fifteen-minute speech, arguing that instead of leaving Germans divided between Germany and Austria, they should all be united in a pan-German superstate. Impressed by this oratory, Drexler gave Hitler a pamphlet called My Political Awakening, which explained the DAP's platform, and invited Hitler to join. The next time Hitler had a sleepless night, he read the pamphlet, decided their ideas were very much like his own, and joined the party he was supposed to be spying on. He was the DAP's 55th member (later he claimed he was the 7th member, to give the impression he was with them from the start). In 1921 he became Der Führer--the leader. And that is how a small band of beer-guzzling bigots began marching down a path that would eventually set fire to the world, killing millions.

Because of Germany's economic troubles in the early 1920s (see below), the DAP/Nazis grew quickly; by 1923 they could claim more than 50,000 members. They had a brief moment of glory in the same year, when General Erich Ludendorff joined them and they attempted to seize power in Bavaria (the so-called Beer Hall Putsch). If this coup had succeeded, it would have been followed by a march on Berlin, to take over the whole country. Instead, it failed badly, and the Nazi leaders were charged with treason. In Hitler's case, he got a remarkably lenient sentence -- five years in prison, of which he only served six months before being paroled. During that time, a steady stream of supporters visited him, bringing gifts, and he spent the rest of his time writing down his personal philosophy in a book, which he called Mein Kampf ("My Struggle"). Later on, in the 1930s, that book became the Nazi Bible. By the time Hitler got out of jail, Germany was starting to recover from both the war and the reparations, and the Nazis did so poorly during the next few years that few people took them seriously. Even in 1928, their best year before the Great Depression, they couldn't claim a membership of more than 100,000 or win more 3 percent of the vote; the latter only gave them a dozen of the 491 seats in the German parliament, the Reichstag.(6)

Even so, the next time a crisis hit Germany, Hitler would be ready.

The Rise of Mussolini

The march from the idealists of the early 1920s to the dictators of the 30s was led not by the Nazis but by the equivalent party in Italy, the Fascisti. The postwar Italians felt shortchanged; they got Italia Irridenta as part of the Versailles treaty, but they felt they deserved more--like Albania, Dalmatia and part of Turkey--because they had lost so many young men. In addition, Italy suffered social and economic damage from inflation (the lira fell to one-third of its prewar value) and disrupted trade patterns. Returning soldiers couldn't find jobs, making them targets for extremist political parties. In some cities residents refused to pay their rent, in protest over poor living conditions. In the countryside, peasants took land from landlords. Everywhere food was hard to find. In the four years after the war, five premiers came and went, either because of their incompetence or because they couldn't solve the problems they faced. The situation favored the appearance of "a man on a white horse." Such a man was Benito Mussolini (1883-1945).

Mussolini got his start as a left-wing political activist. Although he became the editor of the influential socialist newspaper Avanti! ("Forward") in 1912, he was inconsistent in his views and soon displayed his opportunism and pragmatism.(7) When the Italian Socialist party called for neutrality in World War I, Mussolini supported intervention. Party officials removed Avanti! from his control and expelled him from the party. He then put out his own paper, Il Popolo d'Italia ("The People of Italy"), and organized like-minded former leftists into bands called Fascisti, a name derived from the Latin fasces, the bundle of rods bound around an axe that was carried by bodyguards in ancient Rome. During the war, Mussolini volunteered for the army, saw active service at the front, and suffered a wound. When he returned to civilian life, he gave the Fascisti black-shirted uniforms and reorganized them into the fasci di combattimento ("fighting groups") to attract war veterans and try to gain control of Italy.

In the 1919 elections, the Socialists capitalized on widespread unemployment and hardship to become the strongest party. The extreme-right parties did not win a single seat in the Chamber of Deputies. Even so, the Socialists lacked effective leadership and failed to take advantage of their victory. Meanwhile Mussolini's goons beat up opponents, forced castor oil ("Fascist medicine") down their throats, broke strikes, and disrupted opposition meetings--while the government did nothing. When new elections were held in 1921, extreme right-wing politicians still failed to do well, although thirty-five Fascists, Mussolini among them, gained seats. Failing to succeed through the existing system, Mussolini established the National Fascist party in November.

The 1922 government was as ineffective as its predecessors, and frustration with its incompetence fueled the Fascist rise. The trade unions called a general strike to protest the rise of Fascism, but Mussolini's forces smashed their efforts. In October, after a huge rally in Naples, 50,000 Fascists swarmed into Rome; soon after that King Victor Emmanuel III invited Mussolini to form a new government, and granted him dictatorial powers to bring stability to the country. The Fascists remained a minority in Italy, but once they had the central government they packed it with party members and allies, and turned Italy into a one-party state. Thus the October "March on Rome" began Mussolini's reign.

Fascism, like Nazism, emphasized submission to the state, and built a cult of personality around Il Duce, "the leader." Mussolini asserted that "life for the Fascist is a continuous, ceaseless fight," and "struggle is at the origin of all things."(8) Other than statements of this type and his economic theories, it is difficult to figure out exactly what Mussolini intended Fascism to be, beyond being nationalistic, anticommunist, antidemocratic, expansionist, and statist; for example, he preferred not to meddle in private industry, so long as it worked toward his goal of economic self-sufficiency. He encouraged a high birth rate, but noted that individuals were significant only because they were part of the state. Children were indoctrinated "to believe, to obey, and to fight."

Once Italy was firmly under his control, Mussolini started to make threatening gestures at small countries abroad. He also talked constantly about restoring the Roman Empire. "We have a right to empire," the twentieth-century Caesar said, "as a fertile nation which has the pride and will to propagate its race over the face of the earth, a virile people in the strict sense of the word." His first step in that direction was to rename the Mediterranean Mare Nostrum ("Our Sea"). This should have been more alarming than it was, but the world had gotten used to seeing Italians dress up in gaudy costumes and shout slogans.(9)

Yikes! You're not looking at a supervillain's lair; this really is what Mussolini's headquarters looked like.

Beneath the talk of struggles and the trappings of grandeur was the reality of Italy. Mussolini was not as brutal as Joseph Stalin or Adolf Hitler, and his fascism was a far milder form of totalitarianism than what Russia and Germany produced. The Italian people were too laid back to carry out the worst features of dictatorship. There was no class destruction or anti-Semitic persecution in Italy.

Like other dictators, Mussolini had some positive achievements after taking over, such as slum clearance, rural modernization, and campaigns against illiteracy and malaria. The trains ran on time--something no other Italian leader could accomplish--and the omnipresent Mafia was temporarily dispersed, with many of its more notable figures fleeing to the United States. However, these were more than outweighed by the invasion of Ethiopia, excessive military spending, and special benefits to large landowners and industrialists.

The Scourge of the Depression

Every country in Europe had economic problems in the immediate postwar years, but for two, Germany and the USSR, the difficulties were crippling. In the Soviet Union the cumulative effects of World War I, two revolutions, a devastating civil war, and two miserable harvests (1920 and 1921) had emptied the cities and depopulated the countryside. Things were so bad that if the country was given anything in the way of breathing space, life had to get better. Lenin, sensing this, decided to let nature take its course. His program, the New Economic Policy (NEP), and the Five-Year Plans of his successor, Joseph Stalin, are covered in more detail in my Russian history.

Germany's problem was finances. The kaiser's government had spent money at a crazy rate because reparations from the Allies were expected to cover the deficit. Now the boot was on the other foot; the Allies presented the Germans with bills to pay, at a time when the treasury was empty. There was nothing left to do except print more paper money and to borrow from abroad to pay the reparations. This sounds straightforward enough, but the social cost was very high; hyperinflation devalued the German mark until it took 4.2 trillion marks to equal one dollar, and the entire middle class was driven into poverty. Nor did the Allies give the Germans any slack; a delay in just one payment brought a French occupation of the Ruhr that paralyzed German industry in 1923-24. In the late 1920s Germany finally recovered to its prewar level of production, but of course, the Allies hadn't waited in the meantime. In automobiles, for example, Germany had once led the world; now her industry was just turning out 90,000 per year while Britain and France each manufactured about 200,000 per year.

The figures listed in the previous sentence are significant; even more so is the difference between Europe and the United States. American industry had several advantages at this point: its factories were newer, they were switched over to wartime production for only two years (1917-18), and none of them were close enough to the war zone to get damaged. Whereas Europeans listed the numbers of manufactured cars by the hundred thousand, the Americans measured theirs by the million; e.g., four million in 1928 and five million in 1929. Indeed, because of this and because the nations of Europe owed the United States money after World War I, the economy of Europe had effectively come under the US economy's control. The Americans loaned money to Germany, for example, so that Germany could pay its debts to Britain and France, which allowed the Allies to make payments on their debts to the United States. Under this system, European prosperity depended on American prosperity.

Then in October 1929 the American system collapsed suddenly, without warning. A downturn in the business cycle caught the New York stock market at a time when most of its stocks were greatly overvalued, resulting in a crash in prices. As the fortunes of businesses and investors were wiped out overnight, the collapse of the stock market spread to the banking world and international commerce. The flow of raw materials and manufactured goods came to a halt, factories closed, and bread lines grew longer in every city. By the early 1930s there were twenty-five million unemployed in the United States and, because the advanced nations were all interdependent economically, three million unemployed in Britain and six million jobless in Germany.

This was one more blow than Germany's social structure could stand. In the 1932 elections the Nazis took 38 percent of the vote and increased their number of seats in the Reichstag to 230, becoming the largest single party. General Paul von Hindenburg, now president of the republic, had once remarked that Hitler was only fit to be postmaster general, where he could lick stamps with Hindenburg's picture on them. Now in this moment of social and economic crisis, the new generation of army leaders talked him around. In January 1933 Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor; that marked the end of the Weimar Republic and the beginning of the Third Reich.

One month later the Reichstag went up in flames. Hitler immediately blamed the communists for this arson, and bullied parliament members into granting dictatorial powers to deal with the emergency; the Nazis arrested 4,000 communists in the days that followed. One of those arrested was Georgi Dimitrov, the future communist leader of Bulgaria; at his trial he turned the tables and made the president of the Reichstag, Hermann Göring, look like the guilty party, and for that splendid defense, he was acquitted. In August 1934 Hindenburg died, leaving Hitler the undisputed master of Germany. He solved the unemployment problem by starting an immense rearmament program, one so successful that for Germany the depression was over by 1935. He also dropped clear hints as to what all this rearmament was for; he intended to obtain for the Germans an empire, with resources and Lebensraum (living space) on a continental scale.

In Nazi Germany, the closest thing to a worship service was one of the official rallies at Nuremberg.

War Games in Ethiopia and Spain

The Great Depression caused many nations to embrace strong leaders(10), and because of this, war clouds started to gather again. The first aggressive move came in 1931, with Japan attacking China in the Far East, seizing Manchuria. Italy saw its gross national product rise 33 percent during the 1920s, only to lose it all when the Depression struck; now the old problems of inadequate natural resources, unfavorable balance of trade, and expanding population made the country vulnerable to economic disaster. By 1933 the number of unemployed Italians reached one million, and Mussolini decided that a foreign adventure would take everyone's minds off the troubles at home. In December 1934 there was a shooting incident between Ethiopians and Italians, and in the following October, Mussolini sent his legions into Ethiopia. This time they did better than they had in 1896, using planes and mustard gas against barefoot native soldiers who tried to resist with rifles and obsolete cannon.

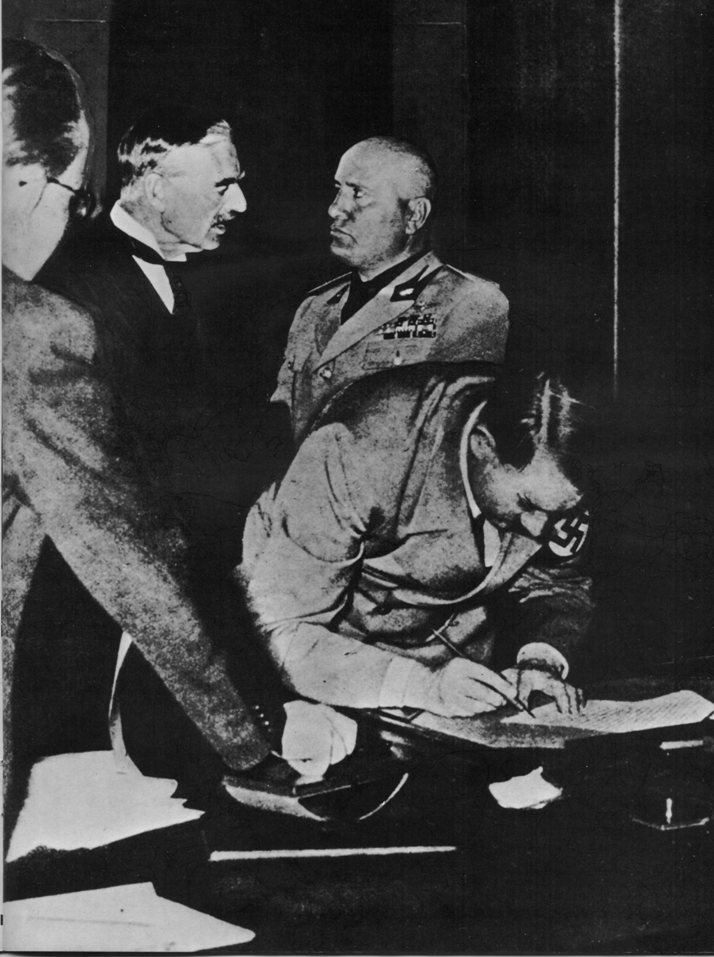

Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie made a dramatic appeal for help at the League of Nations. The League was unconvinced by Italy's shameless argument that Ethiopia was the aggressor, and voted to prohibit shipment of certain goods to Italy and to deny it credit. Mussolini couldn't understand why foreigners would side with "barbarian Negroes," rather than with the motherland of civilization. However, the effect of the sanctions was minor because those items a modern army needs the most--coal, steel and oil--were not included in the list of prohibited articles. France and Britain gave only lukewarm support to the sanctions because they did not want to alienate Italy, while nonmembers of the League like the United States largely ignored the prohibitions. The whole sorry story ended in July 1936, when Mussolini triumphed and sanctions were removed. Haile Selassie, now an emperor without a country, went to live in Britain, the first of several royal exiles who would be forced there in the upcoming war. The same year saw Mussolini and Hitler form an alliance, which they called the "Rome-Berlin Axis"; they chose that name because they expected to see the rest of Europe revolve around them. After that Italy's future was tied with Germany's.

Mussolini with Hitler.

Though Hitler held the gas pedal to the floor on his war machine, it wasn't up to battle strength yet, and it was an unexpected flare-up in Spain that gave Nazism its first test of arms. Spain had become a republic in 1931, when a popular rebellion forced King Alfonso XIII to flee. However, Spanish society was stuck in the eighteenth century, and the Republicans did such a bad job of pulling it into the twentieth century that they alienated the army, the Church and the upper class. Francisco Franco, a right-wing Spanish general, launched a revolt in July 1936, and found plenty of popular support. His 55,000 Moorish troops seized Spanish Morocco, and he called on mainland army garrisons to join him; virtually all of them did. Germany and Italy quickly rushed in tanks, planes, and 85,000 men to help the Falange (Spanish Fascists); four months later Franco controlled half of the country.(11)

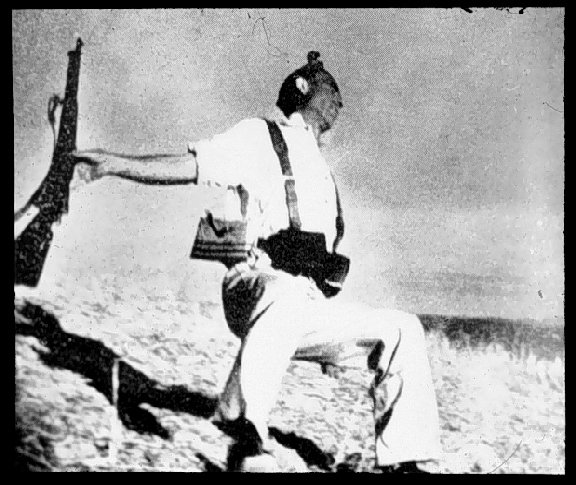

The Spanish Civil War at its midpoint, 1937.

Joseph Stalin felt duty-bound to support the Loyalist government, which included the small Communist Party of Spain in its coalition, but from his point of view a Loyalist victory could be the worst outcome, because a communist-dominated Spain would provoke the Western nations into forming an anti-Soviet alliance. He ended up supporting the Loyalists with Soviet military equipment, but only halfheartedly, hoping to drag out the war for as long as possible instead of winning it. Of course the Loyalists, who were fighting for their lives, felt differently, so along with the aid came a number of Soviet secret police agents. Instead of going after the native pro-Franco elements, they hunted down and assassinated Stalin's enemies among the leftists, especially those from the Trotskyite Worker's Party of Marxist Unity (POUM in Spanish), whose members outnumbered the pro-Stalin communists. The loyalist government was not communist when the civil war began, but gradually it became so as time went on. Aid to the Loyalists slowed down Franco's advance, but it was always too little, too late. During 1937 Franco completed the conquest of the north(12) and west; the last Loyalist attempts to turn back the Fascist tide ended in November 1938 when Stalin stopped sending aid (he chose to cut his losses because Germany and Japan now looked more threatening). Franco followed this up immediately, by driving down the Ebro valley to the Mediterranean, dividing Catalonia from the rest of Loyalist-held Spain. Four months later he captured Madrid, bringing him complete victory. By then half a million Spaniards had died; most of the dead were victims of the mass executions that both sides indulged in (the "Red Terror" of the Loyalists vs. the "White Terror" of the Nationalists), rather than casualties from front-line fighting.(13)

Few photographs have expressed the real meaning of war as effectively as this one, showing a Loyalist soldier the instant he was shot.

Losing the Spanish Civil War was a blow to Soviet prestige, but it had a silver lining. Stalin had an excellent opportunity to test his new hardware, and he was paid handsomely for it ($500 million in Spanish gold). He destroyed the most powerful base of support for his archenemy, Leon Trotsky. Finally, he got his first warning that the western nations would rather appease Fascism than ally with the USSR to stop it (he learned this from the refusal of Britain and France to participate in the war); the next warnings to this effect would come very soon, and too close to the Soviet Union for comfort.

As with Spain, Portugal's first attempt to rule without a king failed, because that country had gone from a monarchy to a republic too quickly. Fifteen years of chaos followed the elections of 1911. During this time, Portugal had eight presidents and 44 cabinets, and suffered through twenty revolutions and coups. In May 1926, General António de Fragoso Carmona seized power, dissolved the parliament, suspended the constitution and began to rule without an ideological program. Carmona followed this up by running for president in 1928, in an election where he was the only candidate. After winning he appointed António de Oliveira Salazar (1889-1970), a professor of economics at the University of Coimbra, as minister of finance. Salazar was given extraordinary powers to put Portuguese finances on a sound basis.

Salazar did so well in his job that he became the most powerful man in Portugal. Profoundly religious, he restored much of the power of the church. In 1930 he founded the União Nacional (National Union) Party; he became prime minister and dictator in 1932 and helped to write a new constitution in 1933. Portugal was now an authoritarian state with a planned economy and no tolerance for opposition, calling itself the Estado Novo (New State).

Suddenly, It Became Hitler's Austria

Beyond Spain, Hitler continued to push for war as hard and as fast as he could. In March 1936 he revived the Luftwaffe, or German Air Force, and brought back compulsory military service. In June he renounced the construction limits put on the navy by the Versailles treaty and offered in its place a new treaty that limited Germany's naval tonnage to 35% of Britain's, a move which would still give him a fleet rivaling France's. Hitler also did something even more daring; on March 7 he sent troops into the demilitarized Rhineland, in clear violation of the treaty. It was a stunning gamble. France could have easily driven the Germans back across the Rhine at this point. But Hitler shrewdly guessed that France and Britain were either too preoccupied with other matters(14) or too timid to attack him for marching into German territory. Both hesitated, and the best opportunity to take out the Nazis was forever lost. The pacifist governments in London and Paris refused to believe that Hitler was really preparing for war; they preferred to think that he was just undoing the worst injustices of Versailles. As the London Times explained it, Hitler had done nothing more than go "into his own back garden." The world would pay with millions of lives a few years later for failing to stop Hitler when it could. And in Germany the Nazis now sang: "Today Germany is ours; tomorrow the world."

Europe in the 1930s, showing the territories seized by Germany and Italy before World War II began.

From the start of his political career Hitler had called for an Anschluss, or union, between Germany and Austria. In Englebert Dollfuss, however, the Austrians had a 4-foot-11 leader who passionately believed in independence. One afternoon in July 1934 armed Nazis stormed into his office and assassinated the brave little chancellor. They failed to seize the government, though, and Kurt von Schusnigg replaced Dollfuss.(15)

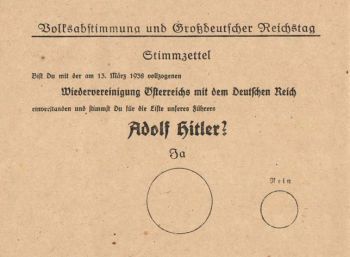

In February 1938 Hitler declared that he was no longer going to tolerate the separation of Austria from Germany, so Schusnigg announced a March 13 plebiscite to decide the matter. Hitler wanted no part in this, so by using a series of threats, he persuaded the Austrian government to let German troops into the country, the day before the voting took place. The results of the plebiscite would have been more convincing if they had been less than the 99.75% Yes vote that the Nazi press later announced, but the British and French knew that many Austrians wanted Anschluss, so they had the excuse they needed for doing nothing. After all, they had already done nothing about Hitler's violations of the Versailles Treaty.

One of the ballots used for voting on the Anschluss. Those in favor of union marked the circle under the word Ja, and those opposed marked the circle under the word Nein. You don't see any bias, do you?

The Munich Agreement

Czechoslovakia was a different case. In September 1938 Hitler declared that another thing he wouldn't tolerate any longer was Czech "mistreatment" of the Sudeten German community in Bohemia, and it was difficult to see how a general European war could be avoided. The Czechs had a modern army of twenty-five divisions, and if the German army crossed the border, the Czechs would fight. The French and Russians had promised their full support if that happened; Poland and Britain probably would have joined the anti-German coalition, too.

Or so everyone thought. At the last moment, Neville Chamberlain, the British prime minister, made a personal intervention. He possessed in full the loathing and fear of war which characterized the British and French in the inter-war period. He recognized that Germany had genuine grievances and persuaded himself that if these were met a repeat of the 1914-18 catastrophe could be avoided. Quoting his personal motto, "Peace at any price," he flew to Munich and persuaded a reluctant Hitler into calling off his attack in return for the Sudetenland. The French were relieved to let Chamberlain defuse tensions; the Russians said nothing and the Czechs, knowing that they couldn't fight alone, bit their lips and signed the agreement.(16)

Munich, 1938. Chamberlain talks with Mussolini while Hitler signs.

It was a terrible decision. If Chamberlain was right and Hitler's ambitions were now satisfied, the crisis was over. But if Hitler wanted more than a pan-German state, the West would have to fight without a great military advantage. Czechoslovakia's defensive frontier--both mountains and fortifications--had been given away and without it the Czech army was worthless. Moreover, the Allied understanding, that the Soviet Union would cooperate with the West in containing the expansion of Nazi Germany, had been destroyed. As Winston Churchill, the opposition leader in Parliament, pointed out, "You had your choice between war and shame -- you chose shame but you will get war."

Looking back with hindsight, it now appears that it would have been better in this case to give war a chance. The German army, the Wehrmacht, was still not ready to take on an opponent who could fight back; the troops at this stage were inexperienced and poorly equipped, while the all-important tanks had not been built yet. Indeed, the German chief of the general staff, Ludwig Beck, resigned in protest, because he thought Fall Grün (Operation Green), the plan for the invasion of Czechoslovakia, would start a war that Germany could not win. On the other side, if the war had happened, the Czechs would have done most of the fighting, because the only potential ally they shared a border with was Poland. Even so, Germany's opponents could have caused diversions on other fronts, like a French counter-attack across the Rhine, and their overwhelming numbers would have worn the Germans down in a few months. Thus, World War II would have been over before anyone could give it a name. Compared with the devastating war that happened in real life, the conflict over Czechoslovakia would be the military equivalent of what park rangers call a "controlled burn," a small fire that burns available fuel before it can cause a larger one. The end result? The Nazis would be discredited before they could launch the Blitzkrieg or the Holocaust (Hitler would probably be thrown out in a coup); the European phase of World War II would be remembered as a petty war, no more important than those in the Balkans before World War I; millions of Europeans that died between 1939 and 1945 would live instead; the Soviet Union would not get an opportunity to impose communism on the other nations of Eastern Europe. If the Americans went to war in the 1940s, they would only fight the Japanese, since the war in the Pacific was caused by events that had nothing to do with Europe. And a lot of authors, film makers and game designers, not to mention The History Channel, would need to find another subject for their works.

Anyway, when he returned to London, Chamberlain waved the Munich Agreement in front of a cheering crowd, and told them he had brought "peace in our time" (see the above picture). But the agreement only lasted for five and a half months, before Hitler had the rest of Czechoslovakia as well. First Hitler encouraged the Slovaks to declare independence from Prague; then he bullied the Czech government into asking for German intervention "to prevent a civil war"; finally the Germans moved in, annexed what was left of Bohemia and Moravia, and turned Slovakia into a German satellite (March 15, 1939). The scheme was clever--Germany could still claim that everything it did was legal--but it was also transparent. No one had any doubt that a madman was now on the loose.(17)

The Maginot Line

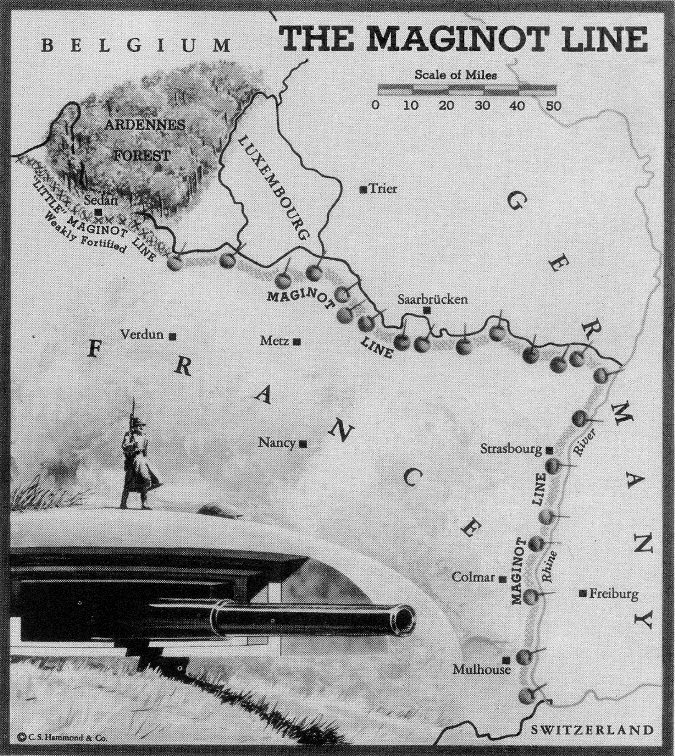

As he left Munich, the French premier, Edouard Daladier, knew that war had been averted, by violating France's promise to protect Czechoslovakia; now he'd have to forget about the network of alliances France had so carefully built to contain Germany. But if Frenchmen did not have the will to fight for another nation, they were willing to defend their home soil, and most Frenchmen thought that France was impregnable. The most ambitious line of defense since the Great Wall of China, the Maginot Line, had been built squarely in Hitler's way. France had no English Channel to stop invasions, so in 1929 the French war minister, Andre Maginot, began to create the best possible substitute: a series of gigantic pillboxes and other fortifications stretching along the border from Switzerland to Belgium, at a cost of $500 million.

It was impressive indeed. Each ten-kilometer unit of the line was staffed by 1,100 men, sported up to seventeen pillboxes housing heavy artillery, and was powered by generators strong enough to provide electricity for a town of 10,000. In front of the pillboxes ran barriers of barbed wire, tank traps, and machine gun nests; the rear was protected by anti-aircraft guns and underground hangars. Beneath the guns ran an anthill of tunnels, going as much as twelve stories underground. Into these tunnels went everything the French thought might be useful, from generators and ammunition dumps to hospitals, dormitories, and movie theaters. The ventilation intakes which brought air into the tunnels forced the air through two hundred feet of pebbles and charcoal filters the size of a bass drum, to screen out any poison gas that might come in from outside, and the interior air pressure could be raised as an additional line of defense against chemical agents.

But it only took one look at a map of Europe (see above) to find the Maginot Line's fatal weakness. The part of the line guarding Sedan and the Ardennes Forest was not as strongly fortified as the rest. You would think Andre Maginot would have given this area more attention, because the most important battle of the Franco-Prussian War had been fought at Sedan, but now the French did not believe Hitler would dare to send his tanks through that kind of terrain. Furthermore, the line stopped here; the 175 miles between the Ardennes and the Channel were left open, because British and Belgian soldiers were expected to defend that part of the frontier. Anyone could go around the Maginot Line easily; unless Hitler and his generals obligingly used their troops in a direct frontal assault, the whole construction with its eastward-pointing guns would be useless. One French general, a tank commander named Charles de Gaulle, saw this clearly. He pleaded for more planes and tanks to match Germany's fast-moving mechanized power. But his superiors put all their faith in the Maginot Line. Paying no attention to what strategy the Germans might be planning, France confidently prepared to fight World War I all over again.(18)

This is the End of Chapter 15.

FOOTNOTES

1. Serbia had emerged from the war more than doubled in size, having acquired Montenegro, Banat (see Chapter 16, footnote #9), Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia, so it required a new name. Because the Serbs were the only group among the southern Slavs with a king, the nation would be a monarchy run by them. At first it was called the "Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes" but in 1929 this was simplified to Yugoslavia, which means the land of the southern Slavs. The Slovenes and Croats weren't really thrilled about becoming part of a Serb-dominated state, but the country was too war-ravaged for them to do anything about it at this time. Later on the Great Depression would keep them quiet. The Croats succeeded in expressing their independence briefly during World War II, but because they chose the wrong side, communism clamped down on them for another two generations afterwards (1944-91).

2. This petty war incidentally disposed of Europe's second communist government, the five-month-old dictatorship of Bela Kun.

3. The voting along the German-Polish frontier was completed by 1922. The French insisted on a fifteen-year delay in the area they tried to claim, the Saarland, but when the vote finally came in 1935 the Saar chose to stay German.

Another area the Allies put to the vote was the Danish-populated part of Schleswig; this was something Bismarck had promised in 1865, but never got around to doing. The voting took place in 1920 and resulted in northern Schleswig returning to Denmark.

4. One of the Italian soldiers that made it through the war was Angelo Giuseppi Roncalli, who served in the medical corps as a stretcher-bearer and a chaplain. Before the war he had been ordained a priest, and forty years after the war, he became Pope John XXIII, one of the best-loved popes of the twentieth century.

5. The French got full revenge at this point for the indemnity they had paid at the end of the Franco-Prussian war; they presented Germany with a bill for Ł6.85 billion. According to the leading economist of the time, John Maynard Keynes, the most Germany could pay was Ł2 billion.

One Frenchman who saw that the Treaty of Versailles would bring future trouble was Marshal Ferdinand Foch. He correctly predicted, "This is not peace. It is an armistice for twenty years."

6. The brown-shirted paramilitary force that gave muscle to the Nazi movement was known as the S.A. (from Sturm Abteilungen, meaning Storm Troopers). After Hitler took command of the party, the toughest and most trustworthy of these were given black uniforms and enrolled in his elite bodyguard, the S.S. (Schutzstaffel).

By 1934 the S.A. was two million strong, many times larger than the army and a threat to everybody. Hitler made sure that it would not seize power by using the S.S. to kill its leader, Ernst Roehm, and the more independent-minded S.A. officers in a coup he later called the "Night of the Long Knives."

7. He was consistent on one thing--he believed that action mattered more than ideology, and that using force was always justified.

8. Mussolini, Fascism, pgs. 35-38.

9. One person who definitely did not approve of Mussolini was Violet Gibson, the Anglo-Irish daughter of the 1st Lord Ashbourne. Ireland's struggle for independence had made Gibson an Irish nationalist, so she took a liberal stand on other issues as well, meaning that she saw Mussolini's dictatorship as moving in the wrong direction. One day in 1926, while Mussolini was the star of a parade in Rome, Gibson fired three shots at him, but he only suffered a minor wound to the nose. The police took her away before the angry mob tore her to pieces, and because Mussolini was very popular at that point, everyone, including Mussolini himself, decided that she must be insane, and she must have worked alone. Gibson was never charged with a crime, put on trial, or imprisoned, but the result was the same; she was deported and confined to a mental asylum in England until she died in 1956.

10. Besides Mussolini, Stalin, Hitler and Franco, there was Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey, and Chiang Kai-shek in China, while the United States elected Franklin Roosevelt, the first (and so far only) president-for-life America has produced. After World War II began Winston Churchill (of Britain) and Hideki Tojo (of Japan) joined the list.

11. Capt. Gonzalo de Aguilera, Franco's press liaison, blamed the whole war on "the introduction of modern drainage. Prior to this, the riffraff had been killed by various useful diseases; now they survived and, of course, were above themselves . . . Had we no sewers in Madrid, Barcelona and Bilbao, all these Red leaders would have died in their infancy instead of exciting the rabble and causing good Spanish blood to flow. When the war is over, we should destroy the sewers."

12. The brutal bombing of a Basque town by German airplanes prompted an angry Pablo Picasso to paint one of his most celebrated murals, Guernica (see below).

Later on, when the Germans occupied France, the Gestapo, Germany's secret police, came to search Picasso's Paris apartment, and they found a photograph of Guernica. One officer asked, "Did you do that?" and Picasso answered, "No, you did."

13. In addition to the USSR, the Republican Loyalists got some help from international communists who sent in units of volunteers from abroad, like the Lincoln Brigade from the United States. Another American active in Spain at the time was the famous author Ernest Hemingway, who served as a war correspondent in 1937 and 1938 and gathered the material to write For Whom the Bell Tolls, a novel which would be nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. Finally, one more participant you may have heard of was George Orwell. Orwell joined POUM, the Trotskyite faction, survived a shot in the neck by a fascist sniper, and as soon as he recovered, Orwell had to disguise himself and flee the country, because all POUM members had been accused of treason, and were now being hunted down by the Stalinists. Thus, the future author of Animal Farm and 1984 had good reason to hate both fascism and Stalinism.

14. England's King Edward VIII, for example. The prime minister and the Church of England refused to let him marry a divorced American woman, Wallis Warfield Simpson. Forced to choose between duty and love, he abdicated in December 1936, and the couple lived out their lives as private citizens. His brother took his place, ruling as George VI until 1952, when he was in turn succeeded by his eldest daughter, Elizabeth II.

What interests us about Edward is that he got along with Nazi Germany, both before and after his abdication. This has led some to believe that if he had remained king, he would have kept Britain from joining the Allies when World War II began, and he might have even joined the Axis. Across the Atlantic, the United States Army and Navy drew up a plan in the late 1920s and early 30s for a war with the British Empire, if the US and UK did not remain friends. The scenario, called War Plan Red, imagined an invasion of Canada as the main theater of the war, with possible attempts to take overseas islands of strategic value as well. The Canadians in turn came up with a plan named Defense Scheme #1, which declared that in the event of a US invasion, the Canadians would stage counter-invasions of the Pacific coast and the Great Plains until British forces could arrive and save the day, the way they had in 1775 and 1812. Imagine how different World War II would have been, if any of this had happened!

15. Hitler and Mussolini did not get along very well when they first met in 1934. Mussolini thought Hitler dressed shabby and talked too much, while Hitler wasn't impressed to see the laundry of Italian sailors hanging from the lines of their ships. The murder of Dollfuss prompted Mussolini to send 50,000 troops into Austria, promising to safeguard Austrian independence against the "Prussians." He changed his mind after the formation of the Axis. When Hitler brought up the Anschluss issue again in 1938, Mussolini did not get in the way. Delighted, the Führer said, "I shall stick with him whatever may happen." It was one of the few promises Hitler actually kept.

16. To make it appear that the Czechs weren't simply knuckling under to Hitler, Mussolini and the French premier, Edouard Daladier, also attended the meeting, though about all they did was pose for photos with Hitler and Chamberlain. The Czechs were also made to give up some other areas that contained ethnic minorities. The Poles got the town of Teschen, and three other disputed enclaves along the Polish frontier, which Czechoslovakia had seized in 1919, while Poland was busy dealing with enemies to the east (the Ukrainians and Bolsheviks). The Hungarians took Ruthenia, Czechoslovakia's easternmost province, and a thin strip of Slovakian territory that was largely Magyar.

17. Hitler forced the Lithuanians to return the port of Memel to Germany in March. In April Mussolini annexed Albania, turning the Adriatic into an Italian lake. Zog I, the king of Albania, fled into exile with his family, and never returned. His son Leka was only three days old when forced to leave; he came back in the 1990s, but the Albanians refused to let him become king.

18. The Germans had their own set of fortifications on the western frontier, which they called the Siegfried Line, but it was more propaganda than concrete. When Germany invaded Poland in 1939 (see the next chapter), there were 23 second-rate German divisions on the line, facing 110 Allied (mostly French) divisions. Bad memories of failed offenses from World War I caused the Allies to hold back until the Germans were ready to strike.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Europe

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|