| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Africa

Chapter 9: THE INDEPENDENCE ERA, PART I

1965 to 2005

This chapter is divided into three parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| Independence: Tying Up the Loose Ends | |

| Civil War in the Ex-Portuguese Empire | |

| Who Owns the Western Sahara? | |

| One-Man Rule: | |

| North Africa Takes a Military Road | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part II

| Nigeria: The Great Underachiever | |

| The Horn of Africa: Horn of Famine | |

| Southern Africa: The Fall of Apartheid | |

| Rwanda, Burundi, and the Congo: Still the Dark Heart of Africa |

Part III

| The Island at the End of the World | |

| America's Stepchild and Her Anarchic Neighbors | |

| The Islamist Menace | |

| Starting Over Again With the African Union | |

| Modern African Demographics | |

| The Challenges Facing Modern Africa |

Independence: Tying Up the Loose Ends

In the previous chapter, we saw how 70 percent of Africa won its independence. Independence came to most of the remaining 30 percent more easily, and can be covered relatively quickly here. In the case of Bechuanaland, Basutoland and Swaziland, it was simply a matter of Britain terminating their protectorates. Bechuanaland and Basutoland became independent in 1966, and changed their names to Botswana and Lesotho respectively; Swaziland became independent in 1968, and changed its name to eSwatini in 2018 (see also Footnote #56). Although all of them were neighbors to South Africa and Rhodesia, they could not oppose apartheid except to say they disliked it, because they were entirely surrounded by white-ruled states.

In the Indian Ocean, Britain quietly let go of Mauritius in 1968, and the Seychelles in 1976. France granted independence to most of the Comoros in 1975, except for the Christian island of Mayotte, which voted to remain with France rather than become part of a Moslem state.(1) France let go of French Somaliland in 1977, which unexpectedly chose to become the independent city-state of Djibouti, rather than join Somalia. On the Atlantic coast, Spain merged the two colonies of Spanish Guinea (Fernando Póo and Rio Muni), and turned them loose in 1968, as a new nation called Equatorial Guinea. That left the five Portuguese colonies, the Spanish Sahara, and Southwest Africa, which we'll deal with in separate sections because they require special treatment.

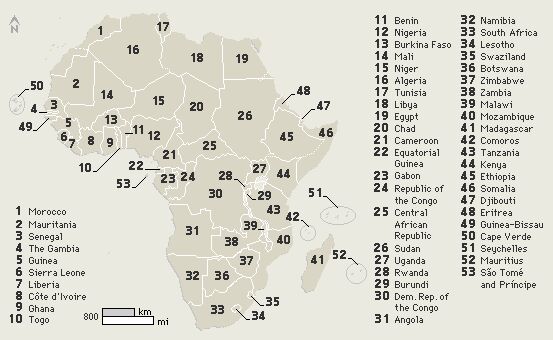

Here again, for your benefit, is the map of Africa that was posted in Chapter 1, so you can keep track of where all 53 countries are (54 if you count the Western Sahara).

Civil War in the Ex-Portuguese Empire

We haven't looked much at the Portuguese Empire since Chapter 6 of this work, and indeed, it survived until the second half of the twentieth century precisely because it did not get much attention. The Portuguese, like the Belgians before 1960, declared they would never give up their colonies, and while a fascist dictator, António de Oliveira Salazar, was in charge, neither local unrest nor outside pressure had much effect on Portuguese policy. Furthermore, Portugal lacked industry at home, so Salazar saw the colonies as Portugal's best chance for prosperity. Consequently he encouraged Portugal's surplus population to move to Africa, where they could strengthen Lisbon's grip and develop the colonies. By 1970 there were 400,000 white settlers in Angola, and nearly 200,000 in Mozambique, out of a total population of 5,588,000 and 9,395,000 respectively.

When independence came to the British, French and Belgian colonies, Portugal would not even grant autonomy. This prompted the local nationalists to take matters into their own hands. In February 1961, a Marxist group, the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), launched riots in Luanda; they were soon joined by a more moderate faction, the Union of the Peoples of Angola (UPA), in the countryside. The government savagely suppressed the rebellion, killing an estimated 20,000 Africans. Those rebels who survived moved east, and found refuge across the border; the UPA got support from the newly independent Congo, while the MPLA established bases in Zambia after that country became independent. In 1966, the UPA split into two pro-western factions: the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA), led by Holden Roberto, the original leader of the UPA, and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), led by Jonas Savimbi. Each of the new factions got most of their support from a particular tribe: FNLA from the Bakongo, UNITA from the Ovimbundu. They also took aid from any foreign power that would give it, including China, South Africa, and (briefly in 1975) the United States. As for the MPLA, it was concentrated in the cities on the west coast, and backed mainly by the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, uprisings against Portuguese rule broke out in Portuguese Guinea and Mozambique in 1962. The nationalist movement in Guinea was the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC)(2), led by Amilcar Cabral; the nationalist movement in Mozambique was the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), led by Eduardo Mondlane. Fortunately, each territory had only one faction fighting for independence, so their struggles were more straightforward than the one in Angola. Another similarity was that the founders of both the Guinean and Mozambican movements were killed before the war ended in a nationalist triumph. In all cases it was a prolonged struggle, because guerrilla fighters living off the land have to spend a lot of time filling their basic needs, rather than going for military or political objectives.

Still, time was on their side. By 1970, the year of Salazar's death, two thirds of Portugal's African empire was in rebel hands, and half of Portugal's national budget was being spent on the armed forces in Africa. Young Portuguese officers saw the wars as no-win situations, and resented the inefficiency of the bureaucracy in Lisbon. In 1974, they staged a coup that toppled Salazar's successor, and installed a leftist regime that was committed to rapidly dismantling the Portuguese Empire. By the end of the year, it granted independence to Portuguese Guinea, henceforth known as Guinea-Bissau because there were already two other countries named Guinea. The Portuguese pulled out of their other African colonies (Mozambique, the Cape Verde Islands, São Tomé & Príncipe, and Angola) in 1975, and 90 percent of the white settlers quickly followed, most of them going either to Portugal or South Africa.(3)

The main political conflict in the world between 1945 and 1990 was the struggle between capitalism and communism, and each new nation was expected to choose sides in the Cold War. Many Africans went with the Soviet Union or China, because they wanted nothing to do with their ex-masters, and all of the former colonial powers were now in the Western (read anticommunist) bloc. Across Africa, the general tendency was that the harder the struggle for independence, the more likely the nationalists would embrace communism. This was the case in Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique, where the new leaders immediately declared themselves Marxists after independence. It wasn't so clear in Angola, though. Attempts to unite the three Angolan factions in a coalition government failed, and they turned against each other on the day of independence. The MPLA seized control of Luanda, allowing its leader, Agostinho Neto, to appear as the rightful president to the world at large, while the FNLA and UNITA set up their own government in the southern city of Huambo (formerly Nova Lisboa)(4). The Soviet Union rushed in arms and Cuban soldiers to support the MPLA; the Cuban force eventually numbered more than 12,500 men, with armored vehicles, artillery, and aircraft supporting it. The other factions also sought aid, but they had a harder time getting it, because few nations wanted to be on the same side as South Africa. Thus, in late 1975 and early 1976, the MPLA got the upper hand, winning every battle and driving its rivals away from the cities; it only stopped when the South African army crossed the border to protect the new dam on the Cunene River.

Guerrilla wars don't end quickly, and the FNLA managed to hold out in the bush until 1984. UNITA did somewhat better; now that Angola had become a hot front in the Cold War, US aid resumed, and South African aid continued, allowing Jonas Savimbi to hold an area as large as Pennsylvania in the southeast. In response, the MPLA declared Angola one of the frontline states against apartheid, and began supporting the South West Africa People's Organization (SWAPO), a Marxist group fighting for the independence of Southwest Africa. The two-front conflict went on until 1988, when South Africa, Angola and Cuba signed an agreement that promised independence to Southwest Africa (henceforth called Namibia) and an end to Cuba and South Africa's involvement in the Angolan war.

Reconciliation between the Angolan factions, however, was tougher, for Savimbi proved to be a sore loser. The two sides agreed to a cease-fire so that elections could take place in 1992, but when the vote went to the MPLA leader, José Eduardo dos Santos (Neto had died in 1979), Savimbi rejected the results as fraudulent, and resumed the war. A second peace agreement, the Lusaka Protocol, was signed in November 1994, and it promised a UN peacekeeping force and eventual integration of UNITA troops into the Angolan army, but dos Santos and Savimbi only participated in it halfheartedly, until a new round of fighting began in 1998. This round lasted until Savimbi was killed in a 2002 battle, and only then did the UNITA demobilize, becoming merely an opposition party. At the time of this writing, Angola is dealing with an epidemic of the deadly Marburg virus, minefields(5), the usual humanitarian crises caused by long wars, and a secessionist movement, the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC), which has tried since 1963 to create an independent state in the bit of Angola on the north bank of the Congo River.

Mozambique's first president, Samora Machel, declared that his country, like Angola, would be on the front line in the struggle against apartheid, and supported black liberation movements in Rhodesia and South Africa; in fact, FRELIMO allowed the use of its camps for this purpose even while it was fighting the Portuguese. South Africa retaliated by sponsoring an anticommunist guerrilla movement, RENAMO (from Resistência Nacional Mocambiçana), which began attacking targets within Mozambique in 1980. Soon the government had lost control over much of the country; travel was only safe by air; a bankrupt economy and RENAMO terror tactics also did much to drive the people over to RENAMO's side. By 1984, Machel was compelled to sign the Nkomati Accord, in which Mozambique agreed to stop supporting the African National Congress and pursue policies that weren't so Marxist. In return South Africa agreed to cut off its support of RENAMO, but it did not keep this promise, so the war continued. Then in 1986, Machel died in a plane crash, and his foreign minister, Joachim Chissano, became the next president.

The war finally began to wind down in 1990; by this time apartheid was crumbling in South Africa, and the end of the Cold War caused support for RENAMO to dry up everywhere. The government introduced a new constitution that rejected Marxism-Leninism, established Mozambique as a multiparty democracy, and guaranteed basic freedoms. Elections were held in 1994, and again in 1999; FRELIMO narrowly won each time, and RENAMO, to the relief of many, eventually accepted these results.

In 1995, Mozambique joined the British Commonwealth of Nations, becoming the only member that was never part of the British Empire.(6) Officially, this was permitted because all of Mozambique's neighbors are Commonwealth members, and they wanted to reward Mozambique "in recognition of Mozambique's unique historical relationship with the Commonwealth in the struggle against the apartheid regime of the old South Africa." (Cynics have said Mozambique might as well join, because its economy is so dependent on present-day South Africa that it is practically a South African protectorate.) The heads of the other Commonwealth states made it clear that Mozambique's admission was a special case, and it should not be seen as setting a precedent.

President Chissano was reelected in 1999, but then in 2001 he declared he would not run again, and criticized leaders who stay in office for more than two terms; some saw this as a reference to Zambia's Frederick Chiluba, who was considering (but chose not to run for) a third term, and Zimbabwe's Robert Mugabe, then in his fourth term. Sure enough, when the next election took place in 2004, Armando Guebuza ran (and won) as the new FRELIMO candidate.

Guinea-Bissau has suffered several bouts of political instability, including a civil war that displaced much of the population (1998-99). The first president, Luis de Almeida Cabral, was overthrown in a 1980 coup, led by Prime Minister João Bernardo Vieira. Vieira made his seizure of power legitimate by winning an election in 1984, and was reelected in 1989 and 1994, but when he dismissed the army chief of staff, General Ansumane Mane, in 1998, part of the army revolted, and it managed to bring down the government a year later. Mane chose Malan Bacai Sanha, the speaker of the National People's Assembly, as acting president; however, when elections were held, Kumba Yalá of the Party of Social Renovation was the winner. Yalá had two major tasks, restoring democracy and helping the country recover from the recent civil war, but these problems went unsolved because he could not get along with either his prime minister or the legislature. He was deposed in a bloodless coup by General Veríssimo Correia Seabra in September 2003, who accused Yalá of violating the constitution. General Seabra was in turn killed in a 2004 mutiny, and the prime minister, Carlos Gomes Júnior, declared that the mutineers were former UN peacekeepers, who had just returned from Liberia and were angry because they had not been paid. New presidential elections are scheduled for early 2006. Only time will tell if this is the last military upheaval; judging from Guinea-Bissau's track record (and that of neighboring countries), the author expects there will be more before the history of West Africa is over.

Who Owns the Western Sahara?

The Spanish-occupied portion of the Sahara was far from appealing, even to desert nomads (a 2004 estimate put the population at just 267,405). The only thing that makes the territory worth having is that it contains the world's richest phosphate deposits, and Spain didn't get around to mining them until the early 1970s. After the rest of North Africa became independent, some nationalists in the Spanish Sahara called on Spain to set them free, and the three neighboring countries (Algeria, Mauritania and Morocco) all put forth claims to the area. Spain ignored all this because, like Portugal under Salazar, it was governed by a fascist dictatorship. As a result, Morocco's King Hassan II chose to act with an attention-getting spectacle; on November 6, 1975, 300,000 Moroccan civilians crossed the border. The campaign was named "the Green March," after the holy color of Islam, because the Moroccans were unarmed and carried copies of the Koran. They advanced about six miles into the Spanish Sahara, and sat down when they reached the barbed wire and machine guns that made up Spain's first line of defense. The standoff went on for a week, until Spain gave in; by this time the Spanish dictator, Francisco Franco, was dying, and with a difficult transition of power expected in Madrid, an international crisis was the last thing Spain needed. The Spanish government agreed to give up the Spanish Sahara, and the Moroccans triumphantly went home; though largely forgotten today, the Green March was one of the most successful nonviolent demonstrations in history.

Three months later (February 1976), Spain pulled out, as promised; Morocco immediately annexed two thirds of the Western (ex-Spanish) Sahara, and Mauritania took the rest. Algeria protested this partition; not only was there nothing left for Algeria, but socialist Algeria had a hard time getting along with conservative Morocco in the first place (they had fought an inconclusive border war in 1963-64 and clashed again on the same spot in 1967). Now the Algerians began supporting a guerrilla movement, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia el Hamra and Río de Oro (Polisario for short). Proclaiming the independence of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, and raiding both Morocco and Mauritania, Polisario made things so hot for the Mauritanians that they gave up their portion of the Western Sahara in 1979; Morocco has controlled the whole territory since then.

The war continued for twelve more years. Few outside governments recognized Morocco's annexation, and Polisario became a member of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1982 (Morocco protested by resigning). However, most advantages were with Morocco, which sharply restricted Polisario's ability to attack by surrounding the Western Sahara with a wall of sand and rock, 9 feet high and almost 2,000 miles long. Finally, a UN-sponsored truce went into effect in 1991. Elections on whether or not the Western Sahara would become independent were supposed to come next, but they have been repeatedly delayed because it isn't clear how many eligible voters are in the territory; Morocco has relocated some of its citizens south of the pre-1976 frontier, and many--perhaps most--of the region's original inhabitants have moved out, to the refugee camps at Algeria's Tindouf oasis.(7)

Spain is gone from the Sahara, but there may be Spanish-Moroccan disputes in the future, because Spain still controls the ports of Ceuta and Melilla. Tensions increased after Muhammad VI succeeded his father Hassan II in 1999, because Morocco wouldn't permit Spanish trawlers to fish in its waters, and Spain wanted Morocco to do something about the illegal immigrants who enter Europe by crossing the Straits of Gibraltar every day(8). Finally, the Spanish people have adopted the Western Saharan refugees, regularly sending them care packages and inviting them to take vacations in Spain, as if to atone for their politicians abandoning them without a struggle. In July 2002 Spain and Morocco squabbled over a rocky island the size of a soccer field, whose only inhabitants are a few goats; the place is called Perejil in Spanish and Leila in Arabic (both mean parsley, because wild parsley grows there). A group of Moroccan soldiers seized the island, planted the Moroccan flag, and offered it as a present to King Muhammad, who was celebrating his wedding at the time. Spain responded by sending two frigates, three patrol boats, a helicopter, and special ground troops--a huge force by 21st-century European standards--to retake the worthless rock. Nobody was killed in the "War of Parsley Point," and the whole affair ended because it was too silly for anyone to take seriously.

One-Man Rule: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

The Good

The colonial powers did not have time to properly train Africans in self-government before they released their colonies, so the new states did not set up Western-style democracies. Instead, they chose a variant of the absolute monarchies that characterized Africa before the Europeans arrived. Government through a hereditary king was no longer fashionable, so the only countries that tried it were those that already had established dynasties: Libya, Ethiopia, Morocco, Lesotho and Swaziland.(9) The rest had been Westernized enough to embrace the idea of a "popular government," so there the rule was to set up a president for life and claim he had the support of the population. In most cases the first president was whoever had been the leading nationalist before independence, and his party became the only political party in the state within a few years.

Many Black African presidents were capable leaders, who ruled their countries for more than a decade. In that category I would include Ahmadou Ahidjo (Cameroon, 1960-82), Hassan Gouled Aptidon (Djibouti, 1977-99), Paul Biya (also Cameroon, 1982-present), Hastings Kamuzu Banda (Malawi, 1964-94), Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Ivory Coast, 1960-93), Moktar Ould Daddah (Mauritania, 1960-78), Sir Dawda K. Jawara (Gambia, 1965-94), Kenneth Kaunda (Zambia, 1964-91), Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya, 1963-78), Seretse Khama (Botswana, 1966-80), Quett Ketumile Joni Masire (also Botswana, 1980-98), Sam Nujoma (Namibia, 1990-2005), Julius Nyerere (Tanzania, 1961-85), Albert René (Seychelles, 1976-2004), Léopold Sédar Senghor (Senegal, 1960-81), and Abdou Diouf (also Senegal, 1982-2000).

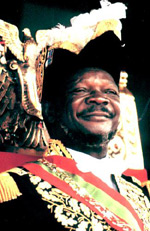

Jomo Kenyatta liked to wear the trappings of traditional African royalty, like the fly whisk and the leopard-skin hat and mantle shown here. He was probably the only leader in modern times who could do that without being seen as a despot. Compare his picture with those of Jean-Bedel Bokassa and Mobutu Sese Seko, later in this chapter.

If you haven't heard of the above leaders, it is probably because the good news has been overshadowed by the bad. Countries where things are going right, like Gabon, never appear in the news. Félix Houphouët-Boigny was an ideological moderate, who made the Ivory Coast the most stable and successful country in West Africa during his 33 years at the helm, by avoiding rash experiments and maintaining the economic ties with France that had existed before independence. However, the country went to pieces after his death, and today he is chiefly remembered for his building projects; he moved the capital from Abidjan to his hometown of Yamoussoukro, and built one of the world's largest churches, Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro. Senghor was probably the most admired African statesman of all; he wrote poetry in French, and was also a philosopher, promoting the idea that all black people are part of one culture, whether they live in Africa or not (he called this concept négritude).

Among these figures, the best example of a benevolent dictator would have been Hastings Banda. The most conservative of the new leaders, Banda micro-managed his subjects, treating the citizens of Malawi as if they were his own children. For example, he introduced a dress code that did not allow women to wear trousers or bare their thighs, and outlawed long hair for men. The most amusing case of censorship came in the early 1980s, when he banned the Simon & Garfunkel song "Cecilia" from the radio; the verses reminded him too much of the bad relationship he was having with his mistress, also named Cecilia ("Cecilia/I'm down on my knees/I'm begging you please to come home"). As a result, television programs were not broadcast in Malawi until the early 1990s. Most of the time, the only legal political party was Banda's Malawi Congress Party (MCP), and he persecuted one religious group, the Jehovah's Witnesses, because they wouldn't accept MCP membership cards (JWs stay out of politics everywhere). When opposition parties were finally allowed to run in the 1994 elections, the voters retired Banda and replaced him with a former cabinet member, Bakili Muluzi. Finally, Banda was unique in being the only Black African leader to have cordial relations with Rhodesia, South Africa and Mozambique, while all three countries were under white rule; in fact, he became the first Black African leader to visit South Africa (1971), and died in a South African hospital in 1997, at the age of 101.

The problem with one-man rule is the lack of checks and balances. When the leaders are good, they are very good, but when they are bad, they are horrid. Such a system has no orderly way of transferring power from one person to another, so changes of leadership are often violent. As a result, in the half-century from 1955 to 2005, Africa saw 187 coups and 26 major conflicts. Indeed, some of the leaders listed above wouldn't be classified as "good" on another continent. Julius Nyerere, for instance, was fond of economic planning on a scale that anyone from the Soviet Union would recognize; his rural collectivization destroyed agricultural output and traditional tribal life, and today, decades after his reign ended, Tanzania is still in the poorhouse. Nevertheless, he ended up in the "good" category here because so many African leaders were worse; at least he didn't make himself rich in the process, and he didn't even take a pension from the government after he retired. Kenneth Kaunda was popular because he was the first Black African head of state to oppose white rule in Rhodesia, but after Rhodesia became Zimbabwe, his increasingly autocratic rule and Zambia's stagnant economy turned the people against him, until they voted him out of office.

The Bad

Absolute power corrupts absolutely, as the saying goes, and in our lifetime Africa has given us plenty of examples. Most of the African leaders in this section came from a military background; if a strong civilian leader did not emerge right after independence, the army usually staged a coup and put one of its officers in charge, with results similar to what happened when juntas governed Latin America. In Togo, for instance, President Olympio had been assassinated in 1963, and the coup that followed did not produce an effective government, so the army chief of staff, Lieutenant Colonel Gnassingbé Eyadéma, staged a second coup and took over in 1967. Though he came under pressure to form a new civilian government, Eyadéma always managed to change the rules to avoid stepping down, and rigged the elections to make sure he would always win. His 38-year reign finally ended in 2005, when he suffered a heart attack and died while being flown to Europe for treatment, but Togo is no closer to seeing democracy--the country's generals immediately swore an oath of loyalty to Fauré Gnassingbé, Eyadéma's son, who became the "acting president." On the other hand, there's Omar Bongo of Gabon, who also became president in 1967 and ruled until his death in 2009; he managed to make Gabon one of the richest countries in Africa (and himself one of the world's richest men at the same time).(10)

There are so many bad examples in the list of African heads of state that we won't be able to discuss all of them here. Some, like Zaire's Mobutu Sese Seko and Zimbabwe's Robert Mugabe, deserve special treatment and will be covered later in this chapter. Ironically, the two nationalists who led the way to independence, Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah and Guinea's Ahmed Sekou Touré, also led the way to corruption. In Ghana, living standards fell and Nkrumah failed to accomplish everything he set out to do, so his rule grew increasingly authoritarian. As early as 1957, he had the CPP-controlled Parliament pass the Deportation Act, which made it legal for the government to expel any foreigners it viewed as a threat to the nation. This was followed by the Preventive Detention Act in 1958, which allowed the government to detain anyone for up to five years without a trial. These acts forced many of Nkrumah's opponents into exile, and he wrote, "Even a system based on social justice may need backing by emergency measures of a totalitarian kind." An ambitious, expensive hydroelectric project on the Volta River was successful, but he was accused of economic mismanagement while working on it; then he dismissed the supreme court and began pronouncing judgments himself. Finally, he alienated the West by trying to secure aid from communist countries, especially the USSR, and he launched a personality cult that encouraged his supporters to call him Osagyefo ("redeemer" or "warrior"). Two unsuccessful assassination attempts made him paranoid, and in 1964, after a referendum that gave him a suspicious 93 percent approval rating, he declared the CPP the only legal political party. With that, Nkrumah overstepped his bounds. While he was visiting China in 1966, an army unit based in Kumasi marched on Accra and overthrew the government. Nkrumah fled to Guinea, where Guinean president Sekou Touré, who owed him a favor, made him an honorary co-president for the rest of his life.

After Nkrumah's ouster, the children of Ghana play on one of his toppled statues.

The main characteristic of Sekou Touré's administration was mismanagement. In November 1965, he accused the French of being behind some recent assassination attempts against him, and broke off relations with France. Then he managed to alienate several of the neighboring countries--Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Niger and Senegal--and bankrupted the state with ill-planned economic ventures. After Sekou Touré died in 1984, it was also revealed that he was responsible for human rights abuses, and Colonel Lansana Conté, Guinea's head of state since then, has largely devoted himself to undoing Sekou Touré's mistakes, though at times it seems that all he can do is keep the situation in Guinea from getting any worse than it was when he took over.

Usually when the soldiers took over, they promised to get out of the way when it was safe for civilian rule to return, but this promise was not always kept. In Ghana they did step down in 1969, and a scholar named Kofi Busia was elected prime minister. Busia tried a conservative approach, but he could not revive Ghana's stagnating economy. This became a financial crisis when the price of cacao plummeted in 1971, and his response, raising prices and interest rates while devaluing the currency, caused high inflation. In January 1972 the military intervened again, with Colonel Ignatius Acheampong replacing Busia. Acheampong banned political activity and set up an economic planning council, but all this did was add political instability to the economic mess that already existed. In 1978, the ruling military council forced Acheampong to resign, and promoted General Frederick W. Akuffo; then less than a year later Akuffo was also thrown out. His successor, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings, had a number of officers arrested and executed for corruption, including Acheampong and Akuffo. He seemed to think this was all that was needed to put Ghana's house in order; in September 1979 he stepped down and allowed the formation of a third civilian government, led by Hilla Limann. But the economy still did not get better, so on the last day of 1981, Rawlings came back in his second coup.

By this time, jobs in Nigeria provided a major source of income for Ghana, and when the Nigerian government expelled a million Ghanaian workers in 1983, Rawlings abandoned his more radical economic ideas and negotiated a structural adjustment plan with the IMF. This time the belt-tightening worked, so Rawlings tried political reforms, introduced a new constitution in 1992, and had himself elected president in the same year. Thus, by the time US President Bill Clinton visited in 1998, he could claim that Ghana had launched a "new African renaissance." Rawlings was reelected in 1996, but was not allowed a third term, so in 2000 the opposition party beat Rawlings' vice president and its candidate, John Kufuor, became the next president. This marked one of the few times in recent African history when political power changed hands peacefully, through elections.

Among the "bad" leaders, the most competent may have been Daniel Arap Moi, who ruled Kenya from Kenyatta's death in 1978 until 2002. Moi had none of the qualities that made Kenyatta an admired statesman, and the economy that grew nicely under Kenyatta deteriorated under his rule, but Moi had the decency to step down, rather than violate the part of the constitution that kept him from running for another term. In the 1990s, refugees from conflicts in neighboring countries, especially Somalia, helped to destabilize Kenya's outlying provinces.

In much of West Africa, however, it seemed that the government couldn't even give its citizens peace, let alone prosperity. A typical example, at least before 1990, was Dahomey (renamed Benin in 1975). Dahomey/Benin's first president, Hubert Maga, was ousted in 1963, and four coups followed over the next six years, until a three-member presidential commission, which included former president Maga, suspended the constitution (1970). They were in turn deposed in 1972 by an army major, Mathieu Kérékou, who ran a military government and tried to turn the country into a Marxist-Leninist state. As with the other countries that tried communism in the twentieth century, it didn't work here, even when Kérékou put forth a new constitution that made the People's Revolutionary Party of Benin the only legal political party. Finally in 1989, he realized that Benin wasn't getting anywhere, so he renounced Marxism-Leninism, adopted yet another constitution, and permitted the country's first free elections in thirty years (1990). To his surprise, he was defeated by the prime minister, Nicéphore Soglo. Soglo used austerity measures and a dose of capitalism to improve the economy, but it didn't happen fast enough to maintain his popularity; in the next two elections (1996 and 2001), the voters returned Kérékou to power.

In addition to manmade problems, a natural disaster made the lives of West Africans miserable. Late in the 1960s, the worst drought of the twentieth century struck the Sahel, turning most of that corridor of grassland into desert. For the whole 1970s and part of the '80s, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso experienced their version of the "Dust Bowl" that once afflicted the Great Plains of the United States. Livestock died, crops failed, locust swarms ate the plants that were left, and the people starved. Even the Tuareg suffered; though they are used to desert conditions, those in the Sahel countries migrated to Algeria and Libya for the duration of the drought, where conditions were no worse than normal. Much of the drought was caused by the southward expansion of the Sahara Desert, a process that we noted in Chapter 1 (e.g., Timbuktu is now in the middle of the desert, rather than on the edge, and only the Niger River allows Timbuktu's inhabitants to stay). Africa has gradually been getting drier since the ice age; even Lake Chad may dry up some day. Still, overgrazing and other bad practices of land management can speed up the desertification process, and it doesn't look like the zone which was home to medieval Africa's greatest kingdoms (see Chapter 5) will ever regain the fertility it once had.

An all-too-common scene from the Sahel, during its fifteen-year drought.

Mali's first president, Modibo Keita, tried to combine Islam with Marxism, but in doing so he mismanaged the country's finances so badly that in 1967 he had to agree to French supervision of the economy. Naturally, this offended those who didn't want to return to anything resembling colonialism, so in 1968 Keita was thrown out by a 14-member military committee and replaced by Lieutenant Moussa Traoré. Traoré ruled by decree until 1976, when he allowed a political party to form, the Democratic Union of the Malian People, but then he delayed elections until 1979, when he won with 99 percent of the vote; he also was easily re-elected in 1985. This heavy-handed rule led to anti-government demonstrations, four coup attempts, numerous cabinet shuffles, and two border wars with Burkina Faso (the Agacher Strip Wars, 1974 and 1985), topped off with the devastation inflicted by the Sahel drought, which left Mali one of the world's poorest countries.

Pressure from Mali's creditors and the IMF forced a restructuring of the economy, allowing free marketing of grains and the privatization of unprofitable government-run corporations. Still, there was growing dissatisfaction with one-party rule, and a suspicion that those at the highest levels of government were not complying with the IMF-imposed plan. Four days of rioting broke out in 1991, which ended with Traoré's removal in a coup. Later on it was discovered that Traoré, in the best tradition of Third World tyrants, had transferred $1 billion to Swiss bank accounts during his 23-year reign. The military promised to return the country to democratic rule as soon as possible, and sure enough, elections were held in early 1992 to establish Mali's third republic. Alpha Oumar Konaré, leader of the Alliance for Democracy in Mali, became the country's first democratically elected president.

The main events of the Konaré administration were a Tuareg rebellion in the north (1990-95, the Tuareg wanted more autonomy from the governments of Mali, Niger and Algeria), and the trials of former president Moussa Traoré. Traoré was sentenced to death in 1993, for his role in the deaths of protesters a few years earlier, and got another death sentence in 1999 after being convicted of embezzlement. In both cases Konaré commuted the sentence to life imprisonment, and finally pardoned Traoré in 2002. Konaré was reelected in 1997, despite charges of fraud that persisted even after former U.S. President Jimmy Carter came to Mali to mediate between the government and the opposition. For the 2002 presidential election, 24 candidates ran, and Amadou Toumani Touré, the leader of the 1991 coup, was the winner, after two rounds of voting.

Niger alternated between stable one-man rule and periods of political upheaval. The first president, Hamani Diori, got off to a smooth start; he was elected just before independence, and reelected in 1965 and 1970. However, the Sahel drought was too much for him; the military accused Diori of mishandling the famine and threw him out in 1974 coup. The head of the supreme military council, Lieutenant Colonel Seyni Kountché, made economic recovery his top priority, and as time went by, his confidence increased enough to let him return most of the cabinet posts to civilians, but a drop in the price of uranium, Niger's most valuable resource, erased most of the economy's gains. Kountché died in 1987, and the next president was his cousin and the army chief of staff, Ali Seybou.

Seybou tried to bring back civilian rule, but under a single-party system. A wave of strikes and demonstrations in 1990 changed his mind in a hurry, so he legalized opposition parties, and a constitutional conference in 1991 replaced him with a transitional government. Meanwhile to the north, the Tuaregs revolted, desiring the same sort of autonomous or independent Tuareg state that the Tuaregs of Mali wanted (1990-95). A new constitution for a multiparty government was ratified, and the elections held in early 1993 were won by a nine-party coalition, headed by Mahamane Ousmane. The political honeymoon didn't last, though; a no-confidence vote in the National Assembly dismissed the cabinet, President Ousmane called for new elections in January 1995, and a coalition of four opposition parties gained control of the National Assembly. For a year after that, Ousmane and Prime Minister Hama Amadou could not get along, and the government was deadlocked. Then in January 1996, Colonel Ibrahim Bare Mainassara ended the logjam by seizing power, arresting Ousmane and Amadou, and banning all political parties. Moving faster than previous military leaders, Mainassara then drafted a constitution for a fourth republic, had it ratified, removed the ban on political parties, and got himself elected president in July, beating four other candidates, including Ousmane.

Many were suspicious about Mainassara's victory at the polls, and he never was able to win much support; in April 1999 he was assassinated by his guards. Another transitional government and another constitution went into effect, resulting in the creation of Niger's fifth republic by the end of the year. A civilian, Tandja Mamadou, was elected president, but judging from the previous track record, we're going to have to watch for many years before it will be safe to say that Niger has solved its political problems.

Chad went straight from colonialism to dictatorship, without a period of democracy in-between. Almost immediately after independence, President François Tombalbaye began putting restrictions on Chad's political system; in 1962 he banned all opposition parties. Worse than that, Chad was divided by the Sahara into a Moslem north and a Christian-animist couth, and being a southerner, Tombalbaye discriminated in favor of the south. The northern response was to stage riots, starting in November 1965, which soon grew into a full-scale rebellion; by the end of the decade, Sudan and Libya were giving aid to the rebels. Tombalbaye was forced to call on the French, and France said it would give military assistance--if Chad carried out real political reforms. He agreed, and released the country's political prisoners, but the next time elections were held (1969), Tombalbaye's name was still the only one on the ballot. Things went downhill from there; the Sahel drought put severe strains on everybody, and the French withdrew their troops in 1971, when a lull in the fighting convinced them that the rebellion was as good as over.

Instead, the fighting flared up again, and a border war with Libya was added to the civil war, when Tombalbaye discovered that Muammar el-Gaddafi was behind an unsuccessful 1971 coup; Libya occupied the northernmost part of Chad, the Aozou strip, because it is an area believed to be rich with uranium and oil (1972). Now Tombalbaye's method of rule grew both brutal and bizarre. He arrested more than a thousand political prisoners, including members of his own party; the party members were accused of using black magic against him in what was called the "Black Sheep Plot," because the alleged magic involved animal sacrifices. Then he announced a program to make the country more African, setting an example by changing the name of the capital, Fort-Lamy, to N'Djamena (see footnote #4), and his own first name from François to Ngarta. Finally, he ordered that all non-Moslem males in the south between the ages of sixteen and fifty undergo yondo, a series of initiation rites, in order to be eligible for promotions in the civil service and the military. Yondo rituals were so tough that not everyone survived (Tombalbaye had facial scars from his own experience with it), and because only Tombalbaye's tribe, which was still pagan, practiced it, Chad's Christians were offended. In April 1975 the army killed Tombalbaye in a coup, after he had started arresting officers.

Unfortunately, the Tombalbaye dictatorship was only the beginning of Chad's woes. His successor, General Félix Malloum, was unable to get the upper hand in the war, though in 1978 he tried to include more northerners in the government. The highest-ranking of those northerners, Prime Minister Hissène Habré, quickly launched a revolt of his own, and forces loyal to him took N'Djamena in February 1979, ousting Malloum. By now there were eleven factions fighting in Chad, so the OAU intervened. A series of international conferences led to a transitional government in November; another northerner, Goukouni Oueddei, became the new president, Colonel Kamougue, a southerner, became the vice president, and Habré became the defense minister.

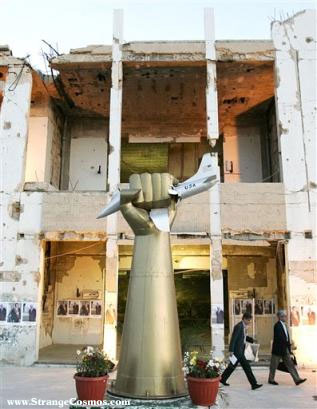

However, this coalition only lasted for two months, due to a falling out between the northerners; Oueddei was pro-Libyan and Habré was pro-Western. Habré launched a new revolt in January 1980, with the backing of Sudan and Egypt, while Libya sent forces to aid Oueddei. Oueddei won the first round, forcing Habré to flee the country, and then at Oueddei's request, the Libyans withdrew to the Aozou strip. It was a rash decision; Habré returned, renewed his offensive, and captured N'Djamena again in June 1982. Oueddei fled to the north, where he set up a rival government (FROLINAT), France and the OAU sent a peacekeeping force to stabilize the south (which meant keeping Habré in power), and Habré tried to exterminate the tribes that were hostile to him. The fighting went on until September 1984, when a cease-fire agreement called for all foreign troops to leave Chad. France and the OAU countries complied and withdrew, but Libya continued to occupy the northern third of the country. Big mistake; Libya's insistence on holding Chadian territory persuaded FROLINAT to switch sides, and together Oueddei and Habré drove the Libyans out by 1987. In 1994 the International Court of Justice ruled that the Aozou strip belonged to Chad, ending Libya's reason to intervene here.

It is estimated that Habré killed 40,000 during his eight-year rule, mostly members of the Sara, Hadjerai and Zaghawa tribes. For this reason, the population and the military no longer wanted him around after the civil war ended, and in 1990 he was ousted by a Libyan-backed insurgent movement, led by General Idriss Deby. Habré managed to kill 300 more political prisoners on his last day in office, and then he fled to Senegal. He tried to make a comeback in 1992, but French and Chadian troops drove him out again. In 2000 the Senegalese put Habré under house arrest, and the government of Chad wants to put him on trial for his atrocities, but so far Senegal has refused to hand him over, reasoning that he did not commit any crimes in Senegal, and besides, no one is in danger as long as Habré stays where he is.

Not everyone in the country was prepared to accept Deby as the new president. The early 1990s saw widespread political and ethnic unrest, as a number of factions sprang up to oppose Deby: the Movement for Democracy and Development (MDD), the National Revival Committee for Peace and Democracy (CSNPD), the Chadian National Front (FNT), the Western Armed Forces (FAO), the Armed Forces for a Federal Republic (FARF) and the Democratic Front for Renewal (FDR). Talks between Deby and the opposition groups did not come to any conclusion, but Deby went ahead with his plan for a new constitution and elections anyway, and got himself elected president in June 1996. Legislative elections followed in January 1997, and international observers noted serious irregularities in both elections. Even so, order finally began to come to Chad; gradually Deby was able to make deals with some of the opposing factions, and use government soldiers to defeat the rest. By 1998 only the Chadian Movement for Justice and Democracy (MDJT) remained, and it was crushed in 2002. The next elections (May 2001) saw Deby reelected easily, with 63 percent of the vote; Chad has been peaceful since then, though democratic reforms have a long way to go before the current oligarchy of northerners shares power with anyone else.(11)

Of all the countries covered in this section, Upper Volta/Burkina Faso was the least stable politically. Upper Volta's first president, Maurice Yaméogo, ran a one-party state for six years after independence, until labor strikes, followed by an army coup, brought down his government (1966). The army chief of staff, General Sangoulé Lamizana, then introduced an austerity program to halt the deterioration of the economy. He led a strictly military government at first, then a mixed military-civilian regime, after he introduced a new constitution in 1970. The plan was for a complete transition back to civilian rule over a four-year period, but the Sahel drought threw the economy off schedule, so Lamizana ruled as a dictator until 1978, when parliamentary rule returned and he was elected president.

That wasn't the end of the matter, though, for a second coup threw him out in 1980; two more coups followed in 1982 and 1983. The result of this instability was that Thomas Sankara, a charismatic Marxist, came to power. He formed the National Council for the Revolution (CNR), an organization whose membership was mostly secret while it existed, except for himself as the president; two smaller Marxist-Leninist groups were also under its umbrella. On August 3, 1984, the first anniversary of the latest coup, Sankara introduced a new flag and national anthem, and changed the country's name to Burkina Faso, meaning "the country of honorable people" (see footnote #4), Upper Volta was obviously a name coined by European geographers). However, many resented the belt-tightening he imposed on the economy, and the government's repressive measures; he also alienated the chiefs of the country's largest tribe, the Mossi, by trying to take away their power. In 1987, Sankara was killed in another coup led by his chief adviser, Blaise Compaoré.

Compaoré abolished the CNR and introduced a more conservative ruling party, the Popular Front (FP). He also suspended the previous socialist policies, which he called "deviations" from the original goals of the 1983 revolution, and introduced limited democratic reforms, which included a new constitution. There was some opposition from leftists, however, who didn't want to have non-leftists represented in the government. On September 18, 1989, while Compaoré was returning from a trip to Asia, two of his associates, Capt. Henri Zongo and Maj. Jean-Baptiste Boukary Lengani, were accused of plotting to overthrow the Popular Front, arrested and executed on the same night; thirty more civilian and miltary opponents of the regime were arrested in December. That seemed to do the trick, where restoring order was concerned; Compaoré ran for president without opposition in 1991, and was reelected easily in 1998, though the second election, and the legislative one of 2002, allowed other parties besides the National Front to participate. Even so, what we know about African politics won't let us call Compaoré's regime a success, at least not just yet. The ancient Greek statesman Solon taught that you can't judge whether a man has had a good life until it is over, and likewise we'll have to wait until Compaoré's successor takes charge before we can declare that Burkina Faso's political problems have finally been solved.

And the Ugly

Finally, modern Africa has seen three really awful dictators who behaved like reincarnations of Nero or Caligula: Jean-Bedel Bokassa of the Central African Republic, Francisco Macías Nguema of Equatorial Guinea, and Idi Amin Dada of Uganda. We will also cover the Comoros, Africa's most ungovernable nation, in this section; to include the Comoros and the three worst tyrants in the previous section would be an insult to those who were merely "bad."

On the first day of 1966, David Dacko, the first president of the Central African Republic, was overthrown in a coup led by his cousin, Colonel Jean-Bedel Bokassa. Bokassa abolished the constitution and began ruling by decree. He built roads, a university and a sports stadium, things his backward, impoverished nation didn't have before, but he also led a brutal, draconian regime, where torture was commonplace and he was said to have taken part in some of the beatings. Still, this wasn't enough for him, so on December 4, 1976, he declared himself emperor Bokassa I, and for the rest of the time he was in charge, the Central African Republic was known as the Central African Empire. Exactly one year later, he staged a lavish coronation. The ceremony cost $22 million, which his country couldn't afford, so the French paid the bill(12); although he invited 2,500 foreign guests, only 600 came, and none of them were heads of state. He explained the no-shows by saying "They were jealous of me because I had an empire and they didn’t."

|

|

Whether he was a colonel, president or an emperor, Bokassa had a thing for Napoleonic fashions.

Bokassa lasted as long as he did because the French propped up his regime with military and financial aid. In return, Bokassa frequently let French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing go on hunting safaris in Africa, gave him gifts of diamonds, and supplied France with the uranium it needed for its nuclear weapons program. Still, his manner of rule became too odious for even the French to stand. The last straw came in early 1979 when he ordered schoolchildren to wear expensive school uniforms made in his own factory, sparking widespread protests; students were arrested, and as many as a hundred were killed. Consequently, when former president Dacko staged a counter coup in September to put himself back in power, the French supported him, rather than Bokassa.

Dacko's second presidency wasn't better than his first, and in 1981 he was ousted in a second coup, this one led by General André Kolingba. Military leaders thus led the Central African Republic until 1993, and after a decade of civilian rule, they took over one more time in 2003. As for Bokassa, he went into exile, but returned unexpectedly in 1986, was tried on murder charges, sentenced to life imprisonment in solitary confinement, and pardoned in 1993, three years before his death. After the pardon he declared himself an Apostle of Christ, prompting his former subjects to nickname him "the 13th Apostle."

Bokassa's golden toilet. How's that for a royal flush?

When Spain turned Equatorial Guinea loose, it had the best health care, the lowest death rate and the second highest per capita income in all of sub-Saharan Africa. Francisco Macías Nguema, the first president, changed that in a hurry. Right after he was elected, he declared himself president for life, and turned the country into a prison camp, the "Auschwitz of Africa." Outside observers called him "The Prince of Fear" and compared him to Cambodia's Pol Pot. Over the next eleven years, an estimated 100,000 refugees fled the country (more than one third of the population at the time), 40,000 were sentenced to forced labor, and 50,000 were killed. Among the latter were several officials, including the pre-independence prime minister and a vice president, and the best-known event of his reign was a mass execution; on Christmas Day 1975, 150 opponents were shot in a stadium, while loudspeakers blared the popular song "Those Were The Days My Friend." When one of his victims was the governor of the Central Bank, Macías Nguema hid the national treasury in his jungle hut. Conditions grew so bad that even his wife ran away, and to keep more people from fleeing, he banned fishing, and ordered all fishing boats destroyed.

Macías Nguema had a phobia against education, having failed Spain's civil service exams during the colonial era; eventually he even outlawed the use of the word "intellectual." A militant atheist, he tried to stamp out organized religion, and promoted a cult of personality in its place that gave him titles like the "Unique Miracle." In 1978 he changed the national motto so that it said: "There is no other God than Macías Nguema." The higher power that he did believe in was magic, because he was the son of a witch doctor. Once he shut down several hospitals because he figured the people only needed traditional medicine, and another time he banned the use of lubricants in the capital city's power plant, claiming that he could keep it generating electricity with his magic powers. You can probably guess how that worked in both cases (hint: not too good!).

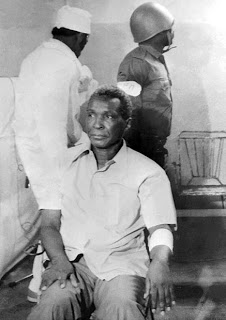

Macías Nguema after his downfall.

In 1979, Macías Nguema was overthrown in a coup led by his nephew, Lieutenant Colonel Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo. A few weeks later he was tried for treason and shot; the execution had to be done by hired Moroccan soldiers, because even after Macías Nguema had been ousted, Guineans believed he had magic powers to make himself invulnerable. Obiang Nguema didn't get rid of his uncle because of concern for human rights, but because he expected to become the next victim if he didn't act. He has ruled Equatorial Guinea since then, keeping in power through a round of ballot box stuffing called an election every few years; in the most recent voting (December 2002), he ran unopposed after all other candidates dropped out to protest electoral irregularities. Obiang Nguema also seems to be taking on some of the characteristics of the first Nguema--in July 2003 the state radio station called him "the God of Equatorial Guinea" and declared that he had the right to "decide to kill without having to give anyone an account and without going to hell"--but so far he has been very careful not to look or act outrageous (which is why you probably haven't heard of him before reading this).

In terms of square miles Uganda is a small nation, but it still has a big ethnic problem within its borders. There are so many tribes living there that Uganda's state-run radio was at one point broadcasting in twenty-four different languages, and these tribes have members in the Congo, Kenya, Rwanda, Sudan and Tanzania, insuring that any conflict in the neighboring states would draw Uganda into it. In addition, the country was divided by religion, with different tribes being Protestant, Catholic, or Moslem, and a large Indian minority was distrusted by the black majority. The kabaka or king of the Buganda tribe was too powerful to ignore, so before independence came in 1962 the leader of the Uganda Peoples Congress (UPC), Milton Obote, worked out a deal that made Uganda a constitutional monarchy, with the current kabaka, Edward Mutesa II (better known to his supporters as "King Freddie"), as head of state, but most of the government's power went to Obote, who now became prime minister.

This arrangement worked until 1966, when Obote suddenly arrested some cabinet members who had tried to force him out of office, and turned against the kabaka, who he claimed was part of the plot. The Ugandan army defeated the kabaka's security force, in a battle that killed some 400 people, and King Freddie fled to exile in England. Then Obote suspended the constitution, declared Uganda a republic with himself as president, and adopted a new constitution that centralized power under the president and abolished the four tribal monarchies. He was thus able to rule as a dictator, but his actions had unwittingly sown the seeds for his own downfall, and they destabilized the country enough to allow all the trouble that occurred in the 1970s and 80s. The man who led the attack on King Freddie's palace had just been appointed army chief of staff a month earlier, Idi Amin Dada (1925?-2003). A former heavyweight boxing champion, Amin came from a small Moslem tribe and only had two years of schooling; he managed to climb to the top in the armed forces because nobody saw him as a threat. However, he already had a reputation for brutality; in the 1950s he had served in the British army, and during the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya, he had gotten information from detainees by threatening castration--and sometimes performing it. Then in 1961, troops under Amin's command massacred Turkana tribesmen, who had come across the border from Kenya to steal cattle. British authorities later discovered that victims of this operation had been tortured, beaten to death, and sometimes buried alive, but because independence was only a few months away, they decided against court-martialing Amin, and merely called him "overzealous." Ten years later, while Obote was flying back from a British Commonwealth conference in Singapore, Amin launched a coup that put him in power.

Unlike other military leaders who take over in a time of crisis, Amin never said a word about letting civilian rule return; instead he just ruled by decree. Simply being president wasn't good enough, either, so he added a number of other titles, which included "President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Idi Amin, VC, DSO, MC, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Sea, and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular," "Big Daddy," and even "King of Scotland." In 1972 he started receiving aid from another head of state known for eccentric behavior, Libya's Muammar el-Gaddafi, which motivated him to expel all Israelis and align Uganda with the Arab world(13); he also took aid from the Soviet Union. Later in the same year, he expelled Uganda's entire Indian community. The 50,000 Indians controlled most of the country's commerce, and this move made Amin popular in the short run, especially among those who took over the Indian-run businesses, but it also resulted in economic collapse.

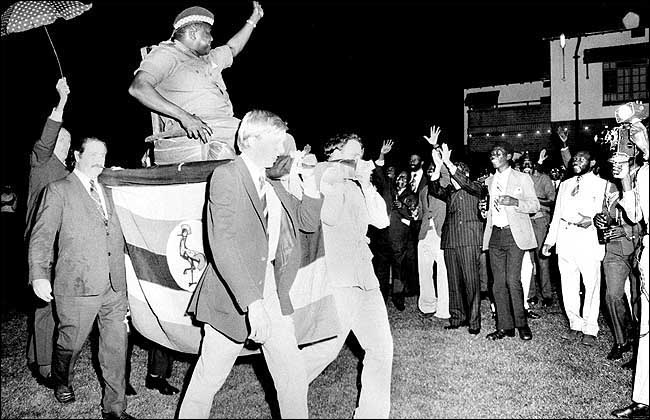

It's a wonder the Organization of African Unity survived its 1975 session, when Uganda was the host country. Idi Amin had his 280-lb. frame carried to the meetings in a sedan chair held by four Englishmen, while a Swede held an umbrella over him, imitating the servants who used to shade African chiefs/kings from the sun. This gave a new meaning to the term "the white man's burden."

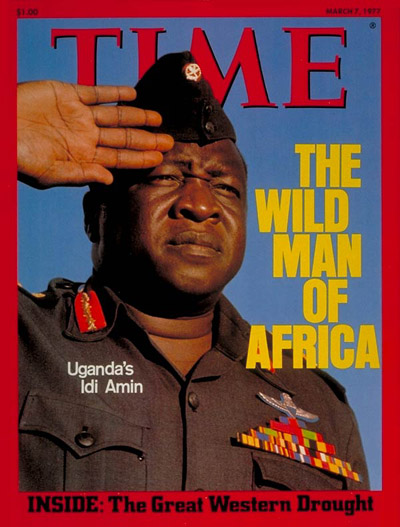

And here is how the Western Media viewed Idi Amin. From a 1977 issue of Time Magazine, courtesy of Wikipedia.

Amin would have been good for laughs if he hadn't been so bloodthirsty at the same time. Estimates of the number of people killed by his regime range from 100,000 to 500,000. Among the victims were soldiers loyal to Obote, members of the Acholi and Langi (two tribes that supported Obote), several cabinet ministers, the chief justice, two American journalists who came to investigate the killings, and Archbishop Janani Luwum, the head of Uganda's Anglican church. Amin reported that the archbishop had died in an automobile accident, but little effort was made to cover up the other murders; often bodies were simply thrown to crocodiles in the Nile River. Amin even claimed to have eaten some of his victims, and there was a report that he kept human body parts in a freezer.

Amin never got along with Julius Nyerere, and in October 1978 he ordered the army to invade Tanzania, hoping to grab a disputed province and distract the people from a worsening situation at home. Instead, Nyerere turned back the attack, and six months later his counter-invasion captured Kampala and toppled the Amin government. With the Tanzanians came two army units made up of Ugandans that had gone into exile during the Amin years; one was led by Obote, and the other was under a guerrilla leader named Yoweri Museveni. Amin, taking four wives and thirty children with him, fled first to Libya, and then to Saudi Arabia, where he spent the rest of his life. Back in Uganda, the looting by Tanzanians and rebel Ugandans in the occupied area caused as much damage to the local economy as Amin's policies had over the previous eight years.

Uganda now entered a state of near-anarchy; four leaders rose and fell over the next twenty months, until elections could be held. When they did take place (December 1980), Obote and the UPC won, but Museveni rejected these results and assembled a new guerrilla force called the National Resistance Army (NRA). Obote responded with a savage campaign to stamp out the rebellion, which included torture and corruption; his security force racked up one of the worst human rights records ever, exceeding even the worst years of the Amin regime. In 1985 an Acholi brigade, complaining that Acholi soldiers always had to fight on the front lines while Obote's other followers stayed safely behind, staged a coup, throwing Obote out a second time. However, the coup leader, General Tito Okello, could only get a fraction of the army behind him, so he began negotiations with the NRA in Nairobi, but in the end the battlefield decided the matter; the NRA marched into Kampala in January 1986, Okello's forces fled north into Sudan, and Museveni became the next president.

Whatever else you can say about Museveni, he brought back stability; he has outlasted all other Ugandan leaders, anyway. He did it by dissolving all political parties, and invited those who used to belong to them to join the government at any level, including the cabinet. The reason for this, as he put it, was because the old parties tended to form around a specific tribe or religious group, and thus helped divide the country; the new system would allow a more fair representation for everybody. Then he tried to grow the economy by diversifying it and adopting a market-oriented strategy.

In foreign affairs, the previously mentioned problem of tribes split between Uganda and other countries encouraged Museveni to act aggressively in the affairs of his neighbors. There was a brief border war with Kenya in the late 1980s, and Uganda also supported Christian rebels in southern Sudan; in return, the Moslem Sudanese government sponsored the Lord's Resistance Army, a fundamentalist Christian guerrilla force, in northern Uganda (There's an example of politics making strange bedfellows for you!). 1990 saw Uganda create a rebel Rwandan army, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), and twice Ugandan forces joined rebel movements in the eastern Congo, first to aid Laurent Kabila, and then to oppose him (1996-97 and 1998-2003).

All things considered, Uganda has made considerable progress in undoing the bad reputation it got under Amin and Obote. Museveni gave the country an army that respects the rights of civilians in peaceful areas, disciplined economic management, and honest democratic elections in a nonparty framework. However, there's still corruption; recently Museveni did away with term limits so that he can stay in charge as long as he wants. Therefore, Uganda still has a long way to go.

The three islands that make up the Comoros nation, Njazidja (also called Grande Comore), Nzwani (Anjouan) and Mwali (Mohéli) are chiefly known for the coelacanth, a strange fish that evolutionists see as the ancestor of all land vertebrates. They also have attractive beaches, but tourists don't beat a path to the Comoros, the way they do for the Seychelles. This is because the Comoros have undergone no less than nineteen coups, both successful and unsuccessful, in the thirty years since independence. And when these islands didn't have coups, they had secession movements; I won't say the Comoros are disintegrating, because they never really had anything to disintegrate from.

The main cause of the instability is the most famous mercenary of the late twentieth century, "Colonel" Bob Denard (1929-2007). Originally a vacuum cleaner salesman named Gilbert Bourgeaud, he joined the French army and saw action in Indochina and Morocco before striking out on his own in the early 1960s. As a mercenary, Denard fought in Zimbabwe, Yemen, Iran, Nigeria, Benin, Gabon, Angola, and Zaire. Usually he had the quiet backing of the French secret services, because he was involved in former French colonies, where they wanted to keep some influence, and because he was fighting communists most of the time. Thus, Denard was directly or indirectly responsible for much of the bloodshed in Africa's conflicts of the 1960s and 70s.

Denard showed up in the Comoros in 1974; by this time he was 45 years old, a good retirement age for a military man. Whatever he was there for, his presence made sure that independence would not come peacefully. A year later, he took part in the coup that quickly deposed the first president, Ahmed Abdulla, and replaced him with a radical left-wing nationalist, Ali Soilih. Soilih tried to set up a secular government for the Comoros, rather than the Islamic theocracy that some inhabitants favored, but while doing this, he went insane. During the next three years he burned all government records, put a 15-year-old in charge of the police department, and when a witch doctor predicted that he would be killed by a white man with a black dog, he killed every black dog on the island of Njazidja. Gangs of teenage thugs roamed the country freely to drink, rape and loot. Worst of all, from France's point of view, Soilih was also strongly anti-French.

In 1978, some Comoran businessmen raised about $6 million to hire somebody to get rid of Soilih. They found Denard more than willing to do the dirty job, because Soilih had not paid him all of the millions promised when Denard had installed him in the first place. With the money he bought a rusty old freighter, recruited some old companions from the Congo, slipped past the French secret agents who had discovered the plot, and landed at Moroni, the nation's capital, in the middle of the night. They found Soilih in the bedroom of his palace with three naked, barely pubescent girls, popping pills, smoking hashish, and watching a pornographic movie. Denard immediately killed the mad tyrant with his submachine gun, and the next morning drove through the streets of Moroni, with Soilih's body draped on top of his jeep, while the citizens cheered and called him their savior and king.

Ahmed Abdulla returned to become president of the Comoros for a second time. However, Bob Denard, who headed the 500-man presidential guard, was the real ruler. In this job he wore many hats; because he looked after French interests in the area, the French supported him until 1981, when François Mitterrand became president of France. South Africa also gave him money, in return for permission to set up a secret listening station in the islands, which was used to spy on ANC bases in Tanzania and Zambia, and to watch the war between FRELIMO and RENAMO in Mozambique. Finally, Denard smuggled arms to Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War, and set up a local company that specialized in construction and security, SOGECOM; to do that he became a citizen of the Comoros, taking for himself the Arabic name of Said Mustapha Mahdjoub.

This arrangement lasted for a decade before it went sour. As the 1980s drew to a close, South Africa changed its mind about supporting a mercenary leader, and so did President Abdulla. In November 1989, Denard learned that Abdulla was about to arrest him on charges of corruption, so he launched a third coup, murdering the president before the president could get him. Two days later, he and the presidential guard removed the provisional president that had succeeded Abdulla, and seized control of the government. Massive public demonstrations followed, and boycotts from the rest of the world; France and South Africa put so much pressure on the Comoros that Denard and his mercenaries left the islands by the end of 1989.

The next president, Said Mohamed Djohar, had a stormy administration; there was an impeachment attempt against him in 1991 and a coup attempt in 1992. In September 1995 Denard came back to play the role of kingmaker once more. He took over the Comoros again in his fourth coup, but France would have none of this, and a week later a force of 600 French commandos invaded the islands. Denard had set up several heavy machine guns before the French arrived, but remarkably, the affair ended without violence; Denard ordered his 33 mercenaries and 300 native soldiers not to fight; he surrendered and was taken to France, where he eventually spent ten months in jail. Djofar returned from exile, but when presidential elections were held in March 1996, the first in the country's history since independence, the winner was Mohamed Taki Abdulkarim, a member of the civilian government that Denard had tried to set up five months earlier.

Taki wrote a new constitution based on Islam that increased the authority of the president, only to see his popularity drop like a stone. In 1997 the islands of Nzwani and Mwali declared their independence, meaning that each of the four islands in the Comoros now had a separate government (remember French-ruled Mayotte). Dozens of troops from Njazidja were killed in a failed attempt to reconquer Nzwani. Then in 1998 Taki died of a heart attack, and his successor allowed the OAU to act as the moderator at a series of reunification talks, in which representatives of all three islands took part. In April 1999 they reached an agreement on setting up a loose federation, but the Nzwani delegation refused to sign it, saying it had to consult its people. This caused anti-Nzwani riots to break out on Njazidja, prompting the army to take over in a bloodless coup. The new Comoran leader, Colonel Azali Assoumani, promised to follow the OAU agreement and return the country to civilian rule; he managed to hold onto power, despite several subsequent coup attempts. At this point, his rule was only over the islands of Njazidja and Mwali, but Nzwani's government collapsed in August 1999, forcing its first president, 80-year-old Foundi Abdallah Ibrahim, to resign. Three coups took place on Nzwani in 2001, but whoever was in charge always favored negotiations for reunification. At the end of the year a new constitution was approved by all three islands in a national referendum. This time the constitution allowed each island to have a president, and specified that the presidency of the whole nation would rotate among them; Njazidja's president Azali got his turn first, in April 2002. Such a system of rotating leadership is inherently unstable, and usually breaks down after a while (e.g., Yugoslavia in the 1980s is a recent example), so we'll watch and see how long it can last in the Comoros.

North Africa Takes a Military Road

Tunisia & Egypt

North of the Sahara, democracy was never popular; it seemed too much a part of Western culture for Moslems to accept. Indeed, Tunisia is the only country in this region that has produced civilian leaders comparable to the ones below the Sahara. So far Tunisia has had two presidents: Habib Bourguiba from 1956 to 1987, and Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, who assumed the presidency after Bourguiba was declared senile. Bourguiba was successful because he presented himself as the moderate alternative, appealing to those Arabs who thought Nasser was too radical. Ben Ali freed political prisoners, and eased restrictions on the press; then he changed the name of Bourguiba's Destour Socialist Party to the Democratic Constitutional Rally Party, and encouraged opposition parties to join it. These moves allowed him to win each election with more than 90 percent of the vote, but international human rights groups have criticized his administration for repressing Islamic fundamentalist parties.(14)

Besides democracy, the available choices for governments in North Africa are monarchy, military dictatorship, and Islamic theocracy. Only Morocco has succeeded with monarchy, and to everyone but Moslem fundamentalists, the prospect of theocracy is downright scary (see "The Islamist Menace." section). That leaves governments run by military men, and the one who set the example for the rest was Gamel Abdel Nasser. After the Suez crisis of 1956, Nasser had the overwhelming support of his people, not to mention that of many Arabs elsewhere, but he also overextended Egypt's resources and abilities, as the disastrous Six Day War showed; he lost the Sinai peninsula to Israel (1967), and the Suez Canal was closed for the next eight years.

Nasser was succeeded in 1970 by one of his officer companions, Anwar el-Sadat. Sadat launched his own war against Israel in 1973, and while he gained a political victory by surprising the Israelis, the Egyptians got the worst of the fighting again. Consequently Sadat switched priorities, and promoted peace after that, signing disengagement agreements with Israel in 1974 and 1975, becoming the first Arab leader to visit Israel in 1977, and signing a treaty that got the Sinai back (1979). However, most of the Arab world was bitterly opposed to any compromise with the "Zionist entity"; they denounced these agreements, and the Islamic fundamentalist movement in Egypt, the Moslem Brotherhood, succeeded in assassinating Sadat in 1981.

At the time of this writing, Sadat's vice-president and heir, Hosni Mubarak, has been in charge of Egypt for nearly as long as Nasser and Sadat put together. He does it by keeping a lower profile; like a turkey during hunting season, he seems to figure that as long as he keeps his head hidden behind a log, nobody will try to shoot it off! Whereas Nasser promoted Egyptian nationalism and "Arab Socialism," and Sadat had his peace initiatives, Mubarak doesn't offer any ideology to justify his rule; all he does is remind everyone that he's better than the alternatives. Thus, while he allows elections every six years, he is only presidential candidate on the ballot each time.

Algeria

Some Algerians didn't think Ahmed Ben Bella, the FLN leader, was qualified to become Algeria's first president, because he spent three-fourths of the war for independence in prison. Still, he came into office with considerable charisma and popularity--and spent that good will quickly. The constitution passed in 1963 gave him almost unlimited power, checked only by a two-thirds majority vote from the National Assembly, so he ruled autocratically, and neglected domestic affairs while promoting Algeria's image abroad. In 1965 the defense minister, Colonel Houari Boumedienne, felt that Ben Bella had gone too far, and deposed him in a bloodless coup.

Boumedienne saw his coup as an "historic rectification" for Algeria. He dissolved the National Assembly, replaced the 1963 constitution, disbanded the militia, and replaced Ben Bellas's Political Bureau with his own 26-member Council of the Revolution; thus, the army replaced the FLN as the country's most powerful political force. Like Ben Bella, Boumedienne was committed to building a socialist state, but his rule was more traditional and less flamboyant; he was reportedly the first Algerian leader who spoke Arabic better than French. Land that had been abandoned by Europeans was appropriated and turned into state-run farms, though Algeria still had to import food to meet its needs. More successful was the nationalization of French-controlled oil fields; Algeria had so many problems to deal with at the time of independence that the oil industry had to be left in French hands until 1971. The nationalization came just in time for Algeria to profit from the OPEC oil price increases of the 1970s.

Boumedienne died in 1978, and another officer, Colonel Chadli Benjedid, took his place. More moderate than his predecessors, Benjedid allowed the privatization of farmland, released and pardoned Ben Bella, and in general relaxed the strict controls Boumedienne had put on Algerian life. He also put Algeria back in the world's spotlight briefly, by acting as the go-between when the United States negotiated to end the 444-day hostage crisis in Iran (see Chapter 17 of my Middle Eastern history). However, a series of economic crises beyond his control struck in the 1980s, making an already bad situation worse: increased unemployment, shortages of consumer goods like cooking oil, semolina, coffee, and tea, etc. Worst of all was a severe drop in oil prices in 1986, which nearly wiped out the country's main source of income.