| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Concise History of Southeast Asia

Chapter 6: SOUTHEAST ASIA SINCE 1975

This chapter covers the following topics:

Brunei, Malaysia, and Singapore: Success Despite the Odds

Brunei

Brunei (pronounced Broon-eye) finally became independent on January 1, 1984, a generation after independence had come to all its neighbors. As expected, the state has done very well, sharing large oil revenues among a small population (409,000 as of 2013). The current per capita income is $40,301, putting it right alongside the developed nations; poverty and unemployment are practically nonexistent here. The sultan, Haji Hassanal Bolkiah, celebrated independence by building a $250 million royal palace, containing two gold-plated domes, 2,000 rooms, air-conditioned stables, and an 800-car garage. From 1987 to 1997 he was the richest man in the world, until Microsoft chairman Bill Gates replaced him in the top spot. But instead of spending the oil money on his own needs and desires, the sultan put most of it toward various building projects (new mosques, schools, bridges, etc.) for the people, plus free education and health care, all done with no income tax levied upon them. In 1996 he celebrated his 50th birthday by building an amusement park, with free admission for his subjects, and paid $17 million for Michael Jackson to perform a concert in a brand-new statium.(1)

Like the rest of Southeast Asia, the sultan lost a big chunk of his money in the Asian financial crisis of 1997. However, it was a bigger shock to him when he had accountants check on how much was lost; they also discovered that over the previous twelve years the sultan's youngest brother, Prince Jefri, had stolen $14.8 billion, an estimated one tenth of the country's total revenue, while serving as finance minister. Prince Jefri spent the money to buy Asprey (the Queen of England's jewelry-making company), a large art collection, 2,300 cars, eight private planes and a helicopter, a yacht named Tits, polo ponies, and several five-star hotels; he also used the money to lure beautiful women, including a former Miss USA, so he could sexually abuse them. When the sultan found out that his playboy brother was responsible for the biggest embezzlement of all time, Jefri fled to Europe, so he banned the prince from returning until he surrendered his assets to the state, which were sold in a 2001 auction to recover some of the losses. The prince came back in 2009, but by then Brunei had spent millions in court battles, its reputation as a Moslem country with a clean government was ruined, and Singapore replaced Brunei as Southeast Asia's richest country. I will let the reader speculate on how Hassanal and Jefri manage to get along these days; in July 2013 Hassanal opened the new Jefri Bolkiah Mosque, presumably named after his brother, in the town of Kampong Batong.

In 1998 the sultan’s son, Crown Prince Al-Muhtadee Billah, was proclaimed heir to the throne and six years later, the 30-year-old prince was married to 17-year-old Sarah Salleh. Whenever the prince succeeds his father, he will be the 30th ruler for this 500-year-old monarchy.

In February 2007, Brunei signed a pledge with Malaysia and Indonesia, in which all three nations promised to conserve/manage an 85,000-square-mile tract of Borneo rainforest, shared between them.

The sultan of Brunei is one of the last monarchs in the world with real power; most of the ministries are still run by his family. However, it doesn't look like the sultan wants to remain an absolute monarch. In November 2004 he amended the constitution to allow Parliament to meet for the first time in forty years. Even so, only one third of the seats in Parliament will be up for election; the sultan will choose who gets the rest. He was also widely praised in May 2005 when he fired four members of his cabinet, including an education minister who wanted to expand religious education, something many parents opposed. Outsiders state that technically, Brunei is still not free, but few citizens will protest because the country is wealthy; they feel that as long as the system works there is no need to fix it.

Malaysia

So far, Mahathir bin Muhammad has been the longest-lasting prime minister of Malaysia; he held the job for twenty-two years. From his predecessors he inherited the problem of tens of thousands of refugees, sailing to Malaysia from Vietnam. Since most of these "boat people" were ethnic Chinese, the Malay government threatened to shoot them on sight. Most of them ended up being held on small offshore islands until other nations agreed to take them in. In April 1989 the government stopped accepting Indochinese refugees.

Under Mahathir the economy continued its strong performance, growing by an average of 8 percent a year, with the only interruption occurring during the 1997 Asian currency crisis and the recession that followed. To raise the standard of living, Mahathir increased private ownership, launched the New Development Policy (NDP), and used high levels of foreign investment to promote trade, manufacturing, drilling for oil, tourism, computers, electronics, and science. He also gave Malaysia some outstanding landmarks, through several mega-building projects. The projects have raised the Petronas Twin Towers (these were the tallest buildings in the world for a decade, until the Taipei 101 and the Burj Khalifa surpassed them), Kuala Lumpur International Airport (KLIA), the North-South Expressway, the Sepang International Circuit, the Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC), the Bakun hydroelectric dam, and Putrajaya, a new city for the executive and judicial branches of the federal government.

At the same time, because he believed that the only democracy that would work in Malaysia is controlled democracy, Mahathir centralized power around the prime minister's position.(2) A 1983 constitutional conflict between him and the hereditary sultans led to a compromise that restricted the power of the sultans to the right to veto legislation. In 1987 the Mahathir government responded to the alleged threat of rising tensions between Malays and Chinese by invoking the Internal Security Act, arresting 106 people, and suspending four newspapers. Then during the currency crisis, Mahathir had a falling out with the deputy prime minister, Anwar Ibrahim, arguing over who was responsible for the crisis, and what to do about it. This led to Anwar being dismissed, arrested, convicted of corruption and sexual misconduct, and sent to prison in 1998. Opponents of the regime founded a new party, the People's Justice Party, led by Anwar's wife, Dr. Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, and though the party only won five seats in Parliament at the next election (1999), it remains an important faction in Malaysian politics today.

Mahathir bin Muhammad's career ended on an unexpectedly bad note. Two weeks before he retired as prime minister, he hosted a summit for the Organisation of the Islamic Conference (OIC) in Putrajaya, and said this:

"We [Muslims] are actually very strong, 1.3 billion people cannot be simply wiped out. The Europeans killed 6 million Jews out of 12 million [during the Holocaust]. But today the Jews rule the world by proxy. They get others to fight and die for them. They invented socialism, communism, human rights and democracy so that persecuting them would appear to be wrong so they may enjoy equal rights with others. With these they have now gained control of the most powerful countries. And they, this tiny community, have become a world power."

He went on to call Israel "the enemy allied with most powerful nations." This was shocking because Southeast Asia is not a place known for anti-Semitism. Until now, local Moslems had not given Israel or the Jews much attention, because their presence was insignificant; there have never been more than a few thousand Jews in the entire region. Predictably, Israel and Western nations called Mahathir's speech "gravely offensive," while Moslem leaders and politicians defended it.

Mahathir hand-picked his successor, Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, and Abdullah gained credibility in his own right by winning the March 2004 general election by a landslide. Although he smashed the opposition parties, he also freed Anwar Ibrahim, leading to hopes for a less authoritarian future. On the economic front, he promised no more grandiose projects, thereby scrapping plans for a new bridge between Malaysia and Singapore to replace the existing causeway. Although Abdullah won the next election, in 2008, the coalition led by the UMNO lost its two-thirds majority in Parliament, so in the following year he announced that he would step down. On April 3, 2009, Mohammad Najib Abdul Razak took his place, and has served as prime minister since then.

Until the 1970s, Malaysia was largely dependent on two industries, tin and rubber, so the economy did not grow as fast as it did for Brunei and Singapore. Still, because of the diversification mentioned above, Malaysia has come in a healthy third place for the region, and with a per capita income of $17,883, it is doing better than average by Third World standards. The Mahathir administration called its ultimate goal "Vision 2020," meaning that it wanted Malaysia to become a fully modern country by 2020, and the current leadership is proceeding on schedule towards that goal. We do not know yet, however, if Malaysia will acquire a First World political system (multi-party democracy, a free press, an independent judiciary and the restoration of civil and political liberties) to go with a First World economy. If it can pull that off and keep ethnic tensions to a minimum, it will definitely remain one of Southeast Asia's happiest places.

Singapore

The way Singapore both survived and grew under Lee Kuan Yew is one of the success stories of the modern era. To deal with the problems his city-state faced, Lee increased his own power and that of the People's Action party (PAP). A master politician, Lee smashed the opposition every time elections were held, effectively making Singapore a one-party state. From 1968 to 1981, the PAP held all seats in Parliament. As time went on, he took an increasing interest in managing even the smallest details of daily life. In 1971 he closed two newspapers, charging that communist Chinese agents bribed the editors. To limit congestion he taxed everyone who owned cars, as well as parents who had more than two children. The "Speak Mandarin" campaign of 1979 attempted to get Singapore's Chinese population to speak Mandarin only, though most of them came originally from the provinces of south China, where other dialects besides Mandarin are spoken. In 1992 Lee Kuan Yew's successors outlawed gum, declaring it a public nuisance to clean up, especially in the train stations.(4)

You have been warned.

Most recently, in 2019 the government announced it was banning ads for packaged drinks with a high sugar content, in an attempt to reduce cases of diabetes and obesity in its aging population.

Of course there have been abuses when so much power is concentrated in the hands of one person. Foreign organizations like Amnesty International occasionally accuse the PAP of imprisoning or torturing dissidents. Drug pushers are punished by hanging, and the 1994 caning of an American teenager for spray-painting cars got worldwide attention. But like the citizens of Brunei, most Singaporeans do not object, because in return they have been given unprecedented prosperity. When Singapore became independent in 1965, the per capita income was less than $320, making it a typical Third World country with an uncertain future; now it is $50,087, the fourteenth highest in the world. This has marked Singapore as one of the "Four Asian Dragons" (the others are South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong) that did very well by imitating Japan's modern, free-market economy. The 2011 Index of Economic Freedom ranked Singapore as the second freest economy in the world, right after Hong Kong, and the Corruption Perceptions Index routinely ranks Singapore as one of the world's least corrupt countries.

To offset all this success, the Singaporean government has one failure--it cannot manage love. In the late 1940s and 1950s, Singapore had its own baby boom, with population growing at a rate up to 4.4% a year. After independence came, the government responded to this with family planning programs. The fertility rate fell immediately, and in 1975 it dropped below the replacement level, meaning there were now fewer births than deaths. Although Singapore is the second most crowded place in the modern world, a shrinking population is cause for alarm, when the surrounding countries are bigger, not always friendly--and their populations are growing. Deciding that it was all right for smart, wealthy people to have as many kids as they wanted, Lee Kuan Yew offered the government's services to help educated women find educated husbands, and ads were placed in overseas newspapers, offering inducements to professionals who immigrate. One year later (1984) he set up a government agency, the Social Development Unit (now called the Social Development Network), to promote dating. The Social Development Unit has offered tea dances, wine tasting, cooking classes, cruises, screenings of romantic movies, and advice to lonely hearts; it even published tips on where and how to have sex in cars! Finally, the government tried cold cash, offering $6,000 to $18,000 for each child born. None of it worked, thanks to Singapore's work ethnic; students are so busy with their studies, and adults are so preoccupied with making money, that they have little time and energy left for romance and babies. In the first thirty years after the agency's founding, about 30,000 couples got married after meeting at state-arranged events; that's 1,000 weddings a year in a population of 5.3 million, not impressive. Needless to say, foreigners found it silly that the Singaporean government is playing the role of matchmaker, though other developed countries will have to face the problem of dreadfully low birthrates very soon--if they aren't in trouble already.

The main industry, as always, is commerce, because Singapore is situated right on the world's busiest shipping lane. But the fortunes of commercial states rise and fall with those of their trading partners, so in the 1980s Singapore diversified its economy by building an oil refinery and factories; tourism and banking have also been encouraged. This farsightedness paid off when the Asian currency crisis struck a decade later; Singapore suffered far less than its neighbors did.

After years of hinting he would quit, Lee Kuan Yew stepped down in 1990, choosing Goh Chok Tong as the second prime minister. One of Goh's first acts was to add an amendment to the constitution that gave some power to a Singaporean president. Besides serving as head of state, the president's jobs were to control the treasury and choose key civil service appointments. Officially this was a safety measure; by splitting power between two people at the top, it would be less likely for a "rogue government" to take over from the PAP and spend the country's cash reserves. The PAP candidate for president, Ong Teng Cheong, expected only token opposition but won with just 60% of the vote, nearly a dead heat by Singaporean standards (August 1993). Running against him was the former head of the Post Office Savings Bank (POSB), who had to be persuaded by the PAP to stand in the election. The votes he garnered were not only protest votes against the PAP, but also a "thank you" message from the common people, because he had protected their savings by maintaining the savings account interest rates during economic downturns.

Singapore watchers expected Ong to be a party loyalist, who would not make waves. Instead, he chose to be an activist, taking his job seriously. Almost immediately, Ong, Goh and Lee (who stuck around as a "senior minister" until he retired in 2011) argued about what the president could and could not do, in a rare show of disunity. Then personal problems doomed Ong to a one-term presidency. His wife died of cancer in 1998, and though he recovered from lymphoma in the same year, the PAP used these ailments as an excuse to announce that it would support somebody else in the 1999 elections. The presidents since Ong have given the PAP far less trouble.

While Goh Chok Tong was at the helm, Singapore went through the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the 2003 SARS epidemic, and foiled plots by Jemaah Islamiyah, the terrorist group that bombed Bali in 2002. He was succeeded by Lee Hsien Loong, son of Lee Kuan Yew, in 2004. Changes/events so far under the younger Lee's administration include the legalization of casino gambling, the reestablishment of the Singapore Grand Prix in 2008, and the hosting of the 2010 Summer Youth Olympics. Two elections have been held since Lee took over, in 2006 and 2011. In 2006 the PAP won 82 of the 84 parliamentary seats and 66% of the votes, but in 2011 it lost one of those seats and its portion of votes dropped to 60%; those who remember how the PAP performed in the past have called the second election a defeat! Time will tell if this is a step in the loosening of the PAP's grip on Singapore's government.

Burma/Myanmar Rejoins the Community of Nations

In 1981 the seventy-one-year-old Ne Win stepped down as president, and was succeeded by a like-minded general, San Yu. However, he retained most of his power by staying on as party chief, which let him singlehandedly ruin the economy with one more trick. The astrologers he trusted had told him that nine was his lucky number, so he issued new denominations of the Burmese monetary unit, the kyat, in 45 and 90-kyat bills, because those numbers are divisible by nine, and ordered four other denominations (25, 35, 75 and 100 notes) taken out of circulation. Ne Win thought this move would let him live to be more than 90 years old, but because he did not allow the exchange of old currency for new currency, everyone in Burma found that 60 percent of their cash had instantly become worthless. As you might expect, this enraged the whole country, and riots broke out in Rangoon and Mandalay. Though the government restored order, and the Burmese media said little about the unrest, the protesters remained angry, and kept each other informed by word of mouth, so more unrest followed.

After ten months Ne Win decided the game was up for him, so in July 1988 he resigned as head of the BSPP, appointed police chief Sein Lwin as his successor, and legalized political parties. Led by the students, the people exploded in a wave of pro-democracy demonstrations. Today this is called the 8888 Uprising, because a general strike and the most important demonstrations took place on August 8, 1988.

Sein Lwin was so unpopular that he resigned after only three weeks; a lawyer named Maung Maung took his place. That took the wind out of the demonstrations, but they continued, because the BSPP promised multiparty elections, but it did not resign so an interim (and presumably impartial) government could oversee the elections. Meanwhile, Aung San Suu Kyi (1945-), the daughter of the national hero, Aung San, made a speech in front of half a million people at the Shwe Dagon, Rangoon's enormous bell-shaped golden pagoda, calling for a non-violent revolution. This instantly made her the leader of the opposition movement, soon to be called the National League for Democracy (NLD); foreigners saw her as another Corazon Aquino, the leader of the 1986 non-violent revolution in the Philippines (see below). Unfortunately for the movement, the protests grew violent again, with frequent clashes between students and soldiers, so on September 18 the military took matters into its own hands. A junta called the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), led by General Saw Maung, killed more than a thousand dissidents in the first week of its rule, abolished the BSPP and the 1974 constitution, and declared martial law. By the end of September, there were around three thousand estimated deaths, one thousand of them in the capital. It was also estimated that by 1989, six thousand NLD supporters had been held in custody, while another ten thousand fled to areas controlled by ethnic minorities in revolt, and joined their armies.

One of the junta's first acts after taking over was to order foreigners to use Burmese-language names for all geographical locations; consequently Burma became Myanmar, and Rangoon became Yangon. However, the NLD insists on using the old name of Burma, and so do many foreign news organizations, even now.

Like Corazon Aquino and Pakistan's Benazir Bhutto, Aung San Suu Kyi was not interested in politics until her family connections pushed her into the limelight. She is politically sharp, and greatly admired, but the obstacles facing her and the NLD have been great. In July 1989 she was put under house arrest along with 42 other NLD leaders, and the army launched a campaign of intimidation. The SLORC did everything it could do to steal the promised election, which took place in May 1990, but the NLD won anyway, capturing 80% of the seats. The government simply refused to step down, its only excuse being that election results as lopsided as the 1990 ones cannot be accepted by the country's non-Burmese minorities. In 1991 Aung San Suu Kyi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, but the government kept her from knowing it until her British husband told her on a visit two weeks later.

International disapproval and economic failure caused Saw Maung to resign in April 1992; he was succeeded by General Than Shwe, who has ruled since then. Former prime minister U Nu was released from prison, and in September martial law was lifted, though Aung San Suu Kyi was not released until August 1995.

The SLORC reconvened its constitutional convention in late 1995, after a three-year delay. Aung San Suu Kyi's NLD party boycotted it because it talked about the army's role in government, instead of democratic principles. Tensions between the SLORC and the NLD heightened in May 1996 when the SLORC arrested more than 200 delegates before they could attend an NLD party congress. Another crackdown occurred in May 1997; the SLORC arrested more NLD members and detained Aung San Suu Kyi in her car for six days, to prevent a meeting intended to commemorate the 1990 elections. When the SLORC realized that its double-dealing with the NLD was preventing good relations with the rest of the world, the SLORC dissolved itself and set up the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) in its place (November 1997), but the only thing that changed was the junta's name. Because reports of human rights abuses still came out, the United States and European Union tightened sanctions against Burma.

The outside world saw Aung San Suu Kyi as Burma's best hope. but the military regime disagreed. Whenever the NLD made gains at the polls, she was placed under house arrest again. Her most recent detention ended in 2011; by that time, she had been confined by the junta for fifteen of the past twenty-one years. For long periods she was not allowed to see her husband and two children. She probably could have left the country to join her family at any time (the government made such an offer), but like Benigno Aquino in the Philippines, she would not have been allowed to return if she did so. In 1999 her husband was denied a visa, though he was sick with cancer; he died three weeks after that, at his home in Oxford. Because she has plunged back into political campaigning immediately after each spell of incarceration ended, she has recently been nicknamed the "Titanium Orchid."

Aung San Suu Kyi, making a speech in 2011. From Wikimedia Commons.

The junta's relations with the Buddhist Sangha (brotherhood of monks) have been uneasy, because pongyis (monks) played a role in the 1988 rebellion and even helped administer the town of Mandalay. Some monks have protested military rule by refusing to accept alms from military households. The junta responded by pressing the Sangha authorities to discipline the young monks. Relations with ethnic insurgents on the borders have been more skillfully handled. General Khin Nyunt negotiated separate cease-fire agreements first with the small hill tribes and then with the Kachin, adopting their armed forces as an autonomous militia and offering economic development aid along with tolerance of their border trading activities (including opium). The Karens gradually lost the informal support that Thailand had given their independence movement, allowing the Myanmar Army to take the main Karen base at Mannerplaw in early 1995. By the end of 1995, the Karen National Union asked to begin peace talks with the Myanmar government. However, active fighting continues between rebel units and the Myanmar military. The major opium warlord, Khun Sa, faced with a U.S. drug indictment and reduced business connections through Thailand, remained in control of a key section of the eastern Shan state until December 1995, when Myanmar troops marched into his base of Homong; Khun retired to Yangon.

By 2007, about twenty-five different ethnic groups had signed ceasefire agreements with the military government. This means the country is now more stable than it has been at any other time since independence. The minorities still fighting against the government are the Karens, the Shans (the most serious clash with the Shans was the Kokang Incident, in 2009), and the Rohingya, a Moslem group in Rakhine (formerly Arakan). The Rohingya have small armed groups in response to the vicious persecution they have suffered at the hands of Burma's Buddhist majority. But whereas a Moslem group in revolt is usually bad news for their non-Moslem neighbors (Thailand and the Philippines are the nearest examples), in Burma the Moslems have gotten the worst of it; the local government has closed Islamic schools, it doesn't let Rohingya marry without official permission, and it does not allow them to have more than two children. Violence reached new levels with a series of riots in 2012, which saw the burning of houses belonging to both Moslems and Buddhists. Since 1991, when the SLORC began settling Buddhists in Rakhine, some 270,000 Rohingyas have fled across the border, mostly to Bangladesh but also to Malaysia and Indonesia. No country wants to accept or help these refugees, though, causing an Australian correspondent to ask, "Are Rohingya the world's most unwanted people?"

In 2002, Aye Zaw Win, the son-in-law of old Ne Win, tried and failed to overthrow the junta. Aye Zaw Win and his three sons were tried for treason, convicted, sentenced to death, and then their sentences were communted to life imprisonment; all four were locked up, the last time anyone heard from them. Ne Win and his daughter were put under house arrest, and Ne Win died eight months later, at the age of 91. It looks like he was right about the dolphin blood and the number nine after all!

In 2005 the government reconvened the National Convention, in another attempt to write a constitution. However, major pro-democracy organisations and parties, including the NLD, were barred from participating, so the convention adjourned a year later without accomplishing anything. Then in 2008, twenty years after the previous constitution had been abolished, the government announced a new constitution, the third since independence. It was approved in a public referendum, and the military promised a "discipline-flourishing democracy" would soon follow, but the opposition sees it as a tool for continuing military control of the country, because a number of seats in both legislative houses are reserved for military delegates.

The Burmese government surprised everyone at 6:37 AM on November 6, 2005, when it announced that it was moving from Yangon to Pyinmana, a logging town almost 200 miles to the north, roughly halfway between Yangon and Mandalay. The decision was made so suddenly that some top officials only got two two days’ notice to pack their bags; those who wanted to quit were not allowed to do so. Immediately government workers, along with their families and equipment, began to be hauled on barely useable roads, to a location that did not have electricity or running water yet. While they stayed in Pyinmana, a new permanent capital, named Naypyidaw ("Abode of Kings"), was built on a vacant lot nearby. Because capitals are also expected to have something to look at, Naypyidaw was given a full-sized replica of the Shwe Dagon, and a monument featuring statues of Burma's three greatest kings (Anawrahta, Bayinnaung and Alaungpaya). Construction was supposed to be finished in 2012, but pictures taken since then show that Naypyidaw is still mostly deserted; the main residents visible are street sweepers working on super-wide but empty highways.

Previously, Pyinmana's only claim to fame is that it was the base of the Burma National Army, during World War II. The government's official explanation for the move was that Yangon was too crowded. However, many Burmese believe that General Than Shwe was listening to the government astrologers, and they warned him that if a foreign power invaded the country, it would start with an amphibious landing at Yangon. Indeed, the astrologers picked the exact minute for the government's announcement of the move. There may also be a more practical reason; the new location puts the government closer to the provinces containing the most troublesome minorities. Then in another break with the recent past, the government adopted a new flag in 2010 that is yellow, green and red (the same colors as the World War II flag), replacing the two red, white and blue flags that had been used since independence.

There were more anti-government protests in 2007, when the junta removed fuel subsidies without warning, causing the prices of oil and natural gas to rise suddenly. As in 1988, monks led the protests, until a renewed government crackdown stopped them; independent sources reported, through pictures and accounts, 30 to 40 monks and 50 to 70 civilians killed, and 200 beaten.

In Myanmar, punk rock is not dead. The country's isolation delayed its discovery of this genre until 1993, when a young man named Ko Nyan found a music magazine in a trash can at the British embassy and read an article about the Sex Pistols, fifteen years after the death of Sid Vicious. The article changed his life, and Ko Nyan singlehandedly introduced the punk culture to Yangon. There among a small portion of the city's residents, it has survived to this day, in spite of (and because of) the junta's attempts to suppress it with jail sentences. It's no coincidence that the leading Burmese punk band, Rebel Riot, got started immediately after the 2007 protests. Because Burmese society since the 1960s has seen the military opposed by everybody else, this National Geographic photo of two teenagers, a punk with a monk, is not as strange as it looks; you could say everyone feels rage against the machine!

On 3 May 2008, Cyclone Nargis swept across the Irrawaddy delta, with winds up to 135 mph. This was the worst natural disaster in Burmese history; outsiders estimated that more than 130,000 people died or went missing and damage to the nation's infrastructure, which included whole villages and farms getting wiped out, totalled $10 billion. Because the rescue and relief effort was more than the government could handle, it allowed foreign agencies to help, but its isolationist tendencies made the crisis worse, by downplaying how bad the devastation really was, and delaying the entry of planes bringing medicine, food, and other supplies.(5)

We saw in the previous chapter that under Ne Win, Burma got along with nobody and was damn proud of it. However, Ne Win's successors gradually realized that it was a bad policy, in a world where all other nations are interdependent. In the mid-1990s, the length of time foreigners were allowed to stay in the country was increased, from one week to one month. More substantial reforms came after the government learned its lesson from the 2008 cyclone. Aung San Suu Kyi and 200 other prisoners were released and/or pardoned, a National Human Rights Commission was established, and labor unions and strikes were legalized. When special elections were held in 2012 to fill 45 vacant seats in the 440-member lower house, the NLD ran candidates for 44 seats, and won 43 of them; this time the winners, including Aung San Suu Kyi, were allowed to take office.

So far the Burmese government's new attitude appears to have paid off. In 2011 Secretary of State Hillary Clinton became the first senior US official to visit Burma, and President Barack Obama paid a visit in 2012. Since 2010 the outside world's economic sanctions have been eased, so the once-depressed economy is now growing at an estimated rate of 5.5% a year. ASEAN has agreed to let Burma host the organization's meetings in 2014. The next important test will come with the next elections, currently scheduled for 2015. If the opposition wins, and the junta steps aside for the winners, we will know for sure that a new era has begun for this ancient land.

Cambodia: The Killing Fields

Communist regimes are expected to behave in a brutal manner, but nobody expected the holocaust that the Khmer Rouge inflicted upon Cambodia. It began with the total evacuation of Phnom Penh after the capital was taken on April 17, 1975. Every man, woman and child was ordered out into the countryside. Nobody was exempt, not even those too old or sick to walk on their own. Overnight, every city in the land became a ghost town. Thousands died on the forced marches to the farms or public works projects they were assigned to. Once they reached their destinations, they were made to work as slaves for 12-15 hours a day. During the next four years an estimated two million Cambodians perished, either by malnutrition(6), disease, exhaustion--or by the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge, who executed anyone without a second thought.

The purpose of all this was a diabolical social experiment. The Khmer Rouge's ultimate goal was to create an agrarian utopia, where everybody was a peasant. From their point of view every element of civilization from the pre-1975 era must be eliminated, so a new, more perfect society could be built. Cities were useless--empty them! Schools don't teach students how to grow rice, so close them. Trade is evil, so abolish all markets. Abolish money. Abolish the postal system, to keep out evil foreign influences. Abolish private transportation and land ownership. Abolish Buddhism and marriage, so the people will work harder, eat less, and produce fewer children. Destroy contaminating foreign inventions, like TV sets and air conditioners. Turn the National Library into a pig sty. Destroy contaminated people: former enemy soldiers, teachers, physicians, ethnic minorities like the Vietnamese and Chams (see Chapter 2), anyone who wore glasses or spoke a foreign language . . .

There was even a rumor that the ancient ruins of Angkor had been torn down by the overzealous Khmer Rouge; fortunately that turned out to be false.(7) To symbolize the start of a new age, the Khmer Rouge proclaimed 1975 Year Zero, renamed the country "Democratic Kampuchea," and proclaimed the start of a new community that would be cleansed of "all sorts of depraved cultures and social blemishes."

Norodom Sihanouk took his time, waiting several months before coming home to Cambodia. When he arrived, he was so appalled at what the Khmer Rouge had done that he quickly returned to China. When he visited a second time in 1976, he was placed under house arrest, where he remained until January 1979. He was far more visible than his communist partners, but he never had much influence over them. With Sihanouk's arrest, a senior member of the Khmer Rouge, Khieu Samphan, became the second president of Democratic Kampuchea, and held that job for the rest of the time the Khmer Rouge ruled Cambodia, but it turned out he was a front man, too. The real leader was a figure named Pol Pot, of whom so little was known that in 1978 a team of visiting Yugoslav reporters asked, "Comrade Pol Pot, who are you?" We saw him in the previous chapter when he was Saloth Sar, and he had covered up his past so successfully that even his own family did not recognize him. Though he revealed himself only gradually, from the start it was always Pol Pot's orders that were being carried out. Unlike other dictators, Pol Pot did not pull any absurd stunts; today he is only remembered for the ghastly slaughter while he was in charge.

Pol Pot in 1977, when the outside world first heard of him.

Pol Pot seemed invincible, but his reign of terror fell victim to the rivalry between Chinese and Russian communists. The Khmer Rouge had always been allied with China, preferring Maoism over Leninism, while the Vietnamese communists joined the Soviet Bloc after the Second Indochina War ended. Before long the Khmer Rouge began persecuting Vietnamese living in Cambodia; Pol Pot also had thousands of his own people (most of them rival party members) tortured to death, calling them "Khmer bodies with Vietnamese minds."

A third Indochina war began in late 1977, started by a border dispute between Cambodia and Vietnam. The Vietnamese launched a massive invasion during the last days of 1978. On January 7, 1979, Pol Pot and his associates abandoned Phnom Penh, and a pro-Vietnamese regime, led by Heng Samrin, was installed there. The new government called itself the KNUFNS, or the Kampuchean National United Front for National Salvation. The Khmer Rouge fled into the jungle, and eventually they went across the border to the refugee camps in Thailand, accompanied by hundreds of thousands of civilians.

Few nations welcomed the change in Phnom Penh; most denounced Heng Samrin and his premier, Hun Sen, as Vietnamese puppets. Only Laos, Vietnam, and the Soviet Union recognized the new regime, and a Khmer Rouge delegate continued to occupy Cambodia's seat in the United Nations. By the end of 1979, the whole country was in danger of starving to death. Agriculture had been totally mismanaged, and the transportation network was in ruins. The United Nations sent in food along with trucks and river barges to transport it. Gradually the famine ended, and life in Cambodia began to recover. The traditional religion and culture were restored, schools were reopened, and Phnom Penh is now full of busy people again, though most streets and buildings still show the scars of war and years of neglect. Bright colored clothing replaced the black pajamas worn by everyone during the Pol Pot years.

A civil war soon replaced the Vietnamese-Cambodian war. 35,000 Khmer Rouge rebels took on the 170,000 Vietnamese troops that supported the Phnom Penh regime. In the early 1980s two more rebel movements appeared: the 15,000-man anticommunist Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KNLF), led by a former Lon Nol supporter, Son Sann; and a neutral faction with 9,000 members led by Prince Sihanouk, the National Union for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful, and Cooperative Cambodia (FUNCINPEC). In 1982 Sihanouk, Son Sann and the Khmer Rouge formed an anti-Vietnamese alliance, and started launching successful hit-and-run attacks against the Vietnamese. The Vietnamese found themselves receiving the same kind of treatment they had dished out against the Americans. When the number of casualties exceeded 50,000, the Vietnamese decided that was enough; they withdrew from Cambodia in 1988-89.

Getting the Vietnamese out did not end the fighting, so in 1991 the four remaining factions--the Phnom Penh government and the three factions trying to topple it--met in Paris and agreed to a truce. The UN got involved and sent 22,000 soldiers, police and civilian workers to occupy the country and save Cambodia from itself. They promised to do the following in just a year and a half: stop the war, repatriate the 350,000 refugees now living in Thailand, and set up a market economy and democracy in a country that was not familiar with either. The UN had never attempted a project so ambitious before.

The biggest problem for the UN was that the killers of the killing fields--the Khmer Rouge--remained on the prowl. Unlike the other factions, they refused to disarm or allow UN peacekeepers into the zones they controlled, and began attacking UN workers or taking them hostage. Despite this, and despite threats that the Khmer Rouge would disrupt elections, UN personnel registered 90% of the civilians to vote, and after convincing them that their ballots would be secret, got a big enough turnout to proclaim the election results acceptable.

When the voting took place in May 1993, Prince Sihanouk, still the perennial favorite, emerged the winner. Second place went to Sihanouk's second son, Norodom Ranariddh. However, Hun Sen's CPP (the Cambodian People's Party) gained control of several provinces, and they threatened to secede if they weren't given a share in the new government. At first Sihanouk set up a transitional government that included only his own faction, but just hours later he pulled another of his famous flip-flops and invited Ranariddh to serve as prime minister and Hun Sen as defense minister. In September a new constitution was adopted restoring the pre-1970 monarchy; the refugees began to return, and the UN peacekeepers withdrew.

This arrangement proved an unstable one. In November 1995 Prince Norodom Sirivudh, secretary general of FUNCINPEC and Sihanouk's half-brother, was accused of plotting to have Hun Sen assassinated; Sirivudh was exiled to France. In March 1996 Ranariddh threatened to withdraw FUNCINPEC from the coalition, thus forcing a national election, unless Hun Sen and the CPP agreed to an equal power-sharing arrangement at the district level. Hun Sen threatened to call out the military, which was dominated by CPP loyalists, if an attempt was made to deprive him of power. By mid-1997 the government was effectively paralyzed, with elected officials not having met for months. In July, when Ranariddh was out of the country, Hun Sen staged a bloody coup and took control of the whole government.(8)

The Khmer Rouge lost ground no matter who was in charge in Phnom Penh. Sensing that their association with Pol Pot was the cause, they brought an ailing Pol Pot out in the open and staged a show trial in 1997. After accusing him of capital crimes and subjecting him to rounds of name-calling, Khmer Rouge leaders sentenced the ex-strongman to life under house arrest. The following spring saw a major government offensive on the Khmer Rouge headquarters at Anlong Veng, near the Thai border; here Ta Mok, the last military leader of the Khmer Rouge, was captured. At this point it looked like Pol Pot would be captured and extradited to the UN, to stand trial for the crimes of his regime. Instead, Pol Pot's guards reported that he had died of a heart attack, and cremated the body before any outsiders could perform an autopsy, leading some to suspect he had been smothered to prevent him from testifying against his former comrades.

By the end of 1998 two other senior Khmer Rouge members, Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea, defected to the CPP; what remained of the Khmer Rouge organization dissolved itself in 1999. In 2004 the Cambodian government and the United Nations agreed to establish a tribunal to try Khmer Rouge mass murderers for the atrocities they committed; those trials began in 2008. However, Hun Sen has opposed holding too many trials, saying he wants to avoid political instability.

Sihanouk left Cambodia again in January 2004, to be treated for cancer, diabetes and hypertension, first in North Korea, then in China. This time his condition did not improve, so in October he abdicated, and spent most of his final years abroad. He died in October 2012, two weeks before his 90th birthday, in Beijing. Back home his eldest son, Norodom Sihamoni, was chosen as the next king by a special nine-member throne council, and enthroned after he received the endorsements of Hun Sen and Ranariddh.

An old territorial dispute was revived in 2008 when the UN organization UNESCO listed the ancient Preah Vihear temple (see Chapter 5, footnote #6) as a world heritage site. For reasons unclear, when the border between Cambodia and Thailand was demarcated in the early twentieth century, the temple ended up on the Cambodian side of the line. However the Thais, who call the temple Phra Viharn, said the border should follow the watershed line of the nearest mountains, which would give the temple to them. In 1962 the dispute was referred to the World Court at The Hague, which ruled in favor of Cambodia, and that was the last word until UNESCO's declaration. The argument over the ruins has gotten so heated that soldiers armed with artillery clashed in 2011, causing damage to the site. The two nations are still willing to talk, though.

Cambodia today is still in a state of recovery. Since 2000 the GDP has grown at 7.7% a year, one of the world's fastest rates, but because Cambodians were dirt poor to begin with, both they and the country still have quite a way to go, before they catch up with any developed countries. The nation's infrastructure had to be built from scratch, because it was completely nonexistent under the Khmer Rouge. The population has grown to 15 million, more than twice what it was before 1975, but 50 percent of them are under the age of 22; many older Cambodians are poorly educated, and maimed or ill (both physically and mentally) from the wars. And decades of fighting left millions of land mines scattered across the country, promising to kill and wound civilians for years to come.(9) As the owner of Southeast Asia's most fertile farmland, Cambodia has the potential to prosper greatly, like it did in the past. Tourism is also becoming a major source of income, as foreigners come to visit Phnom Penh, the ruins of Angkor, the beaches of Sihanoukville--and Anlong Veng.(10) Now that Cambodia's neighbors, especially Thailand and Vietnam, are more interested in cooperation than domination, there is hope that good times will return.

Indonesia: The Suharto Era, And A New Beginning

Suharto in 1966.

Suharto dedicated himself to rebuilding the country and reversing many of Sukarno's policies. Relations were normalized with Malaysia, and Indonesia rejoined the UN. Whereas Sukarno was flamboyant and left-leaning, Suharto was pro-Western and quiet, only appearing in the Western media when he met with more visible heads of state (one example was his hosting of the 1994 G-7 Conference, the annual meeting of leaders from the USA, Canada, Japan, and the four richest nations of Europe). A government organization known as the Joint Secretariat of Functional Groups, or Golkar, became the country's main political party. The Moslem political parties were lumped into one group called the United Development Party, and five non-Moslem parties, including the PNI, were amalgamated to form the Indonesian Democratic Party. This arrangement allowed Suharto to easily win reelection every five years.

Whatever else can be said about Suharto's Indonesia, it was more stable than Sukarno's. Revolutionary fervor became a thing of the past, while the largest oil reserves east of the Persian Gulf allowed the economy to grow at a steady rate of 6% a year, about twice the rate of population growth. However, all was not well in the business sector. In 1975 the state-owned oil company, Pertamina, defaulted on paying loans worth $10.5 billion, and the crisis threatened to bring down the whole economy. It took the dismissal of Pertamina's corrupt director, project cancellations, renegotiation of loans, help from the West and rising oil prices to save the situation. When oil prices stagnated in the early 1980s, Suharto introduced a policy of greater openness (keterbukaan), promoting foreign investment in Indonesia and greater integration of Indonesia into the world economy. He also introduced reforms across a wide range of sectors to cut production costs and improve the competitiveness of Indonesian exports.

The boom in oil and rice production (the latter was caused by new strains of rice introduced in the "Green Revolution") during the Suharto years raised the gross domestic product and reduced starvation among the poor, but otherwise only about 10 percent of workers earned enough to enjoy the benefits of growth. Most of the wealth ended up in the hands of the president's family and friends, a kleptocracy very much like what the Marcos family ran in the Philippines. Suharto's six children amassed huge holdings in industries like airlines, petroleum, banking, automobiles, etc., estimated at between $6 and $30 billion in value. Foreign companies that did business in Indonesia often had to hire junior members of the Suharto clan as "consultants" to grease the wheels. The economic inequalities were exacerbated by the growth of the population to 210 million, despite a relatively successful family-planning program in Java. This made Indonesia the world's fourth most populous country; by itself, Java has more people than most nations. Largely because of the crowding and poverty, rioting occurred in several Indonesian towns in the 1990s.

Several parts of Indonesia have faced severe political unrest since the 1970s. In 1974 a coup toppled the dictatorship running Portugal; the new government decided to give away Portugal's colonial empire, and withdrew from East Timor in the following year. The Frente Revolucionária do Timor Leste Independente (FRETILIN), a leftist group, took control of the capital, Dili, and promptly declared independence. To Jakarta this looked too much like communism coming back to Indonesia, so the army invaded East Timor in December(11). Portugal and the UN condemned Indonesia's invasion, but Indonesia later annexed the area as its 24th province. Human rights groups claimed the Indonesian army may have killed more than 100,000 people, about one sixth of the population, during the annexation. Then in 1991, Indonesian troops fired on a crowd gathered at the Santa Cruz Cemetery in Dili to commemorate the killing of an independence activist. Because the shooting was captured on film, it provoked international condemnation, and the embarrassed Indonesian government admitted to 19 dead, though it is more likely that 270 were massacred. In 1996 Bishop Carlos Ximenes Belo and Jose Ramos Horta, two Timorese dissidents, were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to resolve the conflict. Other separatist guerrillas included the Free Papua Movement in Irian Jaya (western New Guinea) and the National Liberation Front Aceh Sumatra in Sumatra's Acheh region; the Suharto regime treated them brutally as well. In all three cases religion was part of the reason for dissent; East Timor and New Guinea are Christian, while Acheh still prefers radical Islam over the moderate Islam of Java.

Suharto's most visible opponents were not separatists on the outer islands, but closer to home: Moslem groups that never accepted government control, and university students alienated by the government's corruption and human rights violations. In 1978 students launched demonstrations, prompting the government to restrict activity on college campuses and press freedoms. In the early 1990s many dissidents turned to Megawati Sukarnoputri, daughter of the late Sukarno. The government arranged to have her removed as chairperson of the Indonesian Democratic Party in 1996, keeping her from running in the next election, and protesters rioted in Jakarta. Although Sukarnoputri did not enjoy widespread support, she was the first figure in a generation to challenge the incumbent president.

In the early and mid-1990s, Asian officials boasted that they had created a self-perpetuating Pan-Asiatic prosperity zone. According to them, a dynamic economy in one Pacific rim country would stimulate the rest; Japanese savings became investments in the surrounding nations, which were in turn used to export goods to the West, especially the United States. There may have been some truth to this, but such a network also caused massive inflation, collapsed currencies and widespread bankruptcies when one member faltered, in this case Thailand in July 1997.

Of all the countries affected by Thailand's currency woes, Indonesia was hit the hardest. The economy imploded; thirty years of economic gains were wiped out in a few months, and the GDP dropped 15%. The monetary unit, the rupiah, was already one of the world's most devalued currencies; now it went into free fall, dropping in value from 2,300 rupiah per dollar to as low as 17,000 rupiah per dollar (February 1998). The International Monetary Fund put together a foreign aid package totaling $38 billion, one of the largest ever. In return for the emergency aid, Suharto had to agree to major structural reform, a realistic budget for the upcoming year, and to cut back on crony deals. Those turned out to be promises he couldn't keep, as his family stood to lose under any sort of austerity program. An ailing bank controlled by his son was shut down, and it quickly reopened under a new name. In January 1998 he announced a good-times budget that called for a 32 percent increase in spending, and an end to special tax breaks for family-owned businesses, but he still would not close them down. However, he did end government subsidies that kept down the price of oil and foodstuffs like rice, guaranteeing that the poor would have to shoulder the cost of reform. In one year the number of Indonesians living below the poverty line jumped from 20 million to 100 million (almost half the population).

Suharto was now 76 years old, and talked about retirement, but instead he ran for a sixth term in early 1998. Predictably, he won, and then he acted as if nothing had changed. Caught between skyrocketing prices and tumbling wages, people took to the streets in protest. 230 were killed when a ransacked shopping mall caught on fire, and an estimated 500 more died in other riot-related violence. Chief among the victims were members of the Chinese community, always scapegoats when something goes wrong in Southeast Asia.(12)

After the riots ended it was revealed that army had incited them, so that when the inevitable shooting of students happened, Suharto could claim he was saving the country again. But this time even the soldiers supporting the president could see that he was part of the problem, not part of the solution; they simply stood by and watched when rioters threw things at the villas and offices of Suharto's hated children and associates. In May they compelled Suharto, now a president only in his palace, to resign; vice-president Bacharuddin Jusuf Habibie took his place. Habibie was hardly a change; Suharto had adopted him at the age of 13, when his father died, so he was really Suharto's stepson.

"B. J." Habibie turned out to be a caretaker leader. Students demanded immediate elections and the abolition of military appointees to parliament, and when these demands were ignored, they marched on parliament. Meanwhile, Moslems burned churches in Jakarta, and Christians in the eastern islands retaliated by attacking mosques, leading to Christian-Moslem violence in West Timor, Maluku and Borneo; the three separatist regions of East Timor, Irian Jaya and Acheh saw more unrest as well. Consequently, in early 1999 Habibie backed down and allowed elections for both East Timor and the country as a whole. The national election showed that Golkar had lost its teeth; instead of getting at least 70 percent of the vote, as it always did under Suharto, it pulled in just over 20 percent. Megawati Sukarnoputri's Indonesian Democratic Party came in first place, but it had a third of the votes, not a majority. The other parties put together a large enough coalition to keep her from becoming president, so on October 20, 1999, the coalition's candidate, Abdurrahman Wahid, was sworn in as president, and Megawati was sworn in as vice president.

Wahid lasted a bit longer than Habibie, but was even less effective. His attempts to reform the government, clean out corruption, and put Suharto on trial were prevented by those who had much to lose from such actions. Likewise, efforts to bring peace to the most troubled areas got nowhere. Finally, Wahid's health was deteriorating, so in July 2001, he stepped down and Megawati Sukarnoputri was sworn in as the country's first woman president.

Meanwhile on Timor, pro-Indonesian militias, with at least the moral support of the Indonesian army, tried to intimidate the voters, but still 78.5% of East Timor's residents voted for independence. Before the celebrations were done, though, the militias launched a campaign of terror that killed up to 2,000 civilians, displaced much of the population, and burned and looted buildings. But unlike the massacres of 1975 and 1991, the outside world intervened; three weeks later a UN peacekeeping force, led by Australia, arrived to restore order and make it possible for the island's refugees to return. The UN set up the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) to oversee the transition, and East Timor officially became independent on May 20, 2002.

Although stability returned after Megawati became president, otherwise she proved to be an example of the Peter Principle, having risen to her level of incompetence. By following a "Don't rock the boat" policy, she allowed corruption, human rights abuses and military abuses to continue. In addition, the international "War On Terror" spilled over into Indonesia after the twenty-first century began, with Al Qaeda backing Jemaah Islamiyah. an Islamist group that claims to be the successor of Darul Islam (see Chapter 4) and fights to establish a Moslem fundamentalist state over all of Southeast Asia. Jemaah Islamiyah's worst terrorist attack was the Bali bombing of 2002, which killed 202 people, 4/5 of them European and Australian tourists. The group is thought to have also pulled off a second Bali bombing in 2005, and attacks on hotels and the Australian embassy in Jakarta (2003, 2004, and 2009). As a result, foreigners have been reluctant to visit or invest in Indonesia, giving the government one more reason to crack down on terrorist cells in the country.

Because of the problems mentioned in the previous paragraph, when Indonesia's first direct presidential election took place in October 2004, Megawati lost to Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (1949-), "SBY" for short. Yudhoyono was already well-known, having served as a reform-minded general under Suharto, and as Coordinating Minister of Political and Security Affairs under Wahid and Megawati.

The defining moment of SBY's presidency came on December 26, 2004, when a magnitude 9.0 earthquake hit the Bay of Bengal. The resulting tsunami swept across the Indian Ocean, striking the coastlines of Asia and Africa. In the Pacific, tsunamis happen often enough that an early warning system has been set up, but the Indian Ocean has no such thing, so everybody was taken by surprise. As many as 230,000 may have been drowned in that disaster; because the epicenter of the earthquake was just west of Sumatra, 70 percent of the casualties were Indonesian, especially around the port of Bandar Aceh. The United Nations sent in rescue and relief efforts, but the efforts of four nations working together (the United States, Japan, Australia and India) were quicker and more effective. And because the hardest hit area was Acheh, the tsunami put the Acheh separatist movement out of business; in 2005 the rebels negotiated a peace settlement with the government. They may have seen the tsunami as evidence that Allah wasn't on their side after all.

Because SBY did well in his first term, he was re-elected in 2009. However, corruption remains a serious problem, more acts of terrorism could happen, and while the military no longer acts like it is the most important branch of government, it is still very influential. Even now, with Suharto dead and gone, attempts to bring corrupt officials to justice rarely result in convictions, sometimes because of the possibility that a crackdown would implacate members of the present-day government as accomplices. But no one ever said a 35-year-old, multibillion dollar corruption syndicate would be easy to uproot.

Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono visiting the White House. US-Indonesian relations were close during the Obama administration, because Barack Obama grew up in Indonesia, under the name Barry Soetoro. This picture is from Wikimedia Commons.

East Timor Since 1999: The New Kid On The Block

As a new nation, East Timor is trying to find its place in the modern world. Unlike other Southeast Asian states, it does not have a tradition of an ancient monarchy, or even of local chiefs, in its heritage. In a nutshell, East Timor's history began five hundred years ago when Portugal discovered it, and then not much else happened until the second half of the twentieth century.

Xanana Gusmão, the head of FRETILIN's military wing, became the first president, and Mari Alkatiri, the longtime leader of the party, became prime minister. They found themselves in charge of one of the world's poorest countries; with no local industries or job openings, East Timor would be dependent on foreign aid for the forseeable future. Poverty was one reason for a student riot in December 2002; before it was over, five students was killed, the prime minister's house and a supermarket were set on fire, and shops were looted.

There is hope for long-term improvement, though, because petroleum and natural gas deposits have been discovered in the Timor Sea. The main obstacle to extracting the oil and gas is a dispute with Australia over where the border runs between them, which would determine who owns the deposits. Another potential resource is coffee, which is starting to be grown in the hills of Timor. Finally, there is tourism; East Timor get 1,500 tourists a year, though the country could handle a lot more.

East Timor joined the United Nations in September 2002, four months after independence. The UN peacekeeping force was steadily downsized, so when a new crisis broke out in 2006, it was too small to help the government restore order. This time it was a rally turned into a riot, in support of 600 soldiers that had been dismissed for deserting their barracks; twenty-eight people were killed and over 20,000 fled their homes. The distribution of oil funds and the poor organization of the Timorese army and police may have been factors starting the violence as well. Australia, Portugal, New Zealand, and Malaysia sent troops to help stop the violence. Afterwards, pressure from President Gusmão and a majority of FRETILIN party members compelled Prime Minister Alkatiri to resign, because he had been accused of lying about distributing weapons to civilians, and ordering a hit squad to threaten and kill his opponents.

All this must have given Gusmão too many headaches, because he did not run for a second term in the 2007 elections. José Ramos-Horta was elected instead, and he turned around and appointed Gusmão as the next prime minister. On February 11, 2008, renegade soldiers tried to assassinate the president and prime minister in two separate attacks; their apparent leader, Alfredo Reinado, died in the gunfire. Gusmão wasn't hit, but President Ramos-Horta was critically injured from shots in the stomach, and had to be sent to a hospital in Australia for treatment. Nevertheless, he was able to complete his term.

In recent news, East Timor applied to join the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in 2011, but at the time of this writing has not yet been accepted(13). When his term ended May 2012, President Ramos-Horta was succeeded by the commander of the armed forces, José Maria Vasconcelos, better known as Taur Matan Ruak ("Two Sharp Eyes"), the nom de guerre he adopted during the struggle for independence. At the end of 2012, the last UN troops (from New Zealand) were pulled out of the country.

Laos: Feeling Good--And That's All

We saw in the previous chapter that unlike the communists in Cambodia and Vietnam, the Pathet Lao (called the Lao People's Revolutionary Party after 1975) used politics more than military force to seize power. Once they had abolished the 600-year-old Laotian monarchy, they instituted the same sort of hardline policies that were practiced in Vietnam. Though Prince Souvanouvong was now the president, he was also a figurehead; real power went to the premier, Kaysone Phomvihane. Private trade was banned, the few existing factories were nationalized, livestock was confiscated, and young people were even required to get permission from party cadres before falling in love. More than 40,000 royalist military officers and other "enemies of the state" were banished to a jungle gulag of "reeducation camps." Without US military aid and trade with Thailand, the economy tanked, and what the Soviet Bloc gave was not enough to replace the loss; a badly planned attempt to collectivise agriculture only made things worse. 400,000 people (nearly 14% of the population) fled the country, many of them ending up in Thai refugee camps. This included virtually all the educated class, setting Lao development back at least a generation.

The government also had to deal with anticommunist guerrillas (mostly Hmong tribesmen) roaming the countryside, so Soviet advisors and Vietnamese soldiers were sent in. Because relations with China were poor during this time, there are reports that China gave aid and training to Hmong resistance forces in Yunnan, the nearest Chinese province. Repeated counterattacks (which may have used poison gas, if CIA reports are correct) broke rebel resistance; most of the Hmong guerrillas and one third of the tribe eventually defected to Thailand. Up to 100,000 rebels may have been killed altogether. By 2007, the Hmong revolt was effectively suppressed.

Laotian refugees found the Thai government unwilling to give them Thai citizenship, though there are more ethnic Lao on the Khorat plateau than in Laos itself. Those that went to Western countries like the United States found it difficult to adapt to the very different culture they found there. This was especially the case with the Hmong; instead of becoming stereotypical "rags-to-riches" Asian immigrants, they ended up as a burden on society, living on welfare checks indefinitely. For that reason today's dissidents rarely run away, expecting life to get better if they stay home. Those Laotians who can afford exit visas find it relatively easy to apply for and receive one.

The turning point came in 1979 when Premier Kaysone declared a dramatic change of course. He made private farming and trade legal again, called for a more efficient price structure and an increase in wages, and ordered a 60% devaluation of the monetary unit, the kip. He declared, "It is inappropriate, indeed stupid, for any party to implement a policy of forbidding people to exchange goods or carry out trading. Such a policy is suicidal." This was followed up with a more comprehensive reform package in 1986, called the "New Economic Mechanism."

Laos became the first communist country to mix capitalist and socialist practices in the form Mikhail Gorbachev would call "Perestroika" a few years later. Economic improvement was slow in coming, though, because for most of the 1980s, Vietnam was the only country that traded with Laos much. Trade with China had been cut off in 1979 to protest the brief China-Vietnam war, and was not fully reinstated until 1989. Relations with Thailand were strained as long as there were Vietnamese soldiers in Cambodia and Laos, due to clashes between Thais and Vietnamese along the Cambodian border. But as the situation improved for Laos in the 1990s, it made more diplomatic overtures to other countries, and Thailand replaced Vietnam as the principal trading partner, because the Thais have a strong economy and unlike the Chinese and Vietnamese, they share a common religion and similar language with the people of Laos. This may explain why the supposedly godless communists running Laos are no longer trying to restrict the activities of Buddhist monks.(14) In 1995, the United States announced a lifting of its ban on aid.

There was a setback with the Asian economic crisis of 1997. The collapse of the Thai baht led to inflation of the kip, because Thai and Laotian currencies were now tied together by trade. The inflation led to several protests, which the government put down with the same zeal that Burma's military leaders showed in suppressing their own dissidents. Laos learned two lessons from the crisis: that free-market capitalism can be unstable at times, and that China and Vietnam were still their real friends, because they provided loans and advice to get through hard times. Fortunately the crisis did not affect Laos for long. Because of that, common household items like spray paint, light bulbs and vitamins were easy to get in Vientiane before they became available in Hanoi. There also has not been any starvation, because 80 percent of the people are still farmers, and they have always grown enough food for their own needs, trading by barter when they don't have money.

In 1986 Souvanouvong stepped down as president for reasons of poor health. He was succeeded first by Phoumi Vongvichit, who had been the Pathet Lao's chief negotiator during the war years. Premier Kaysone took his place in 1991, then died a year later and was replaced by the finance minister, Nouhak Phoumsavane; General Khamtai Siphandon, the Pathet Lao's military commander, moved up to replace Nouhak as premier. Nouhak was already 82 years old when he became number one, but because he was in good health for his age, he held the top spot until 1998. Khamtai followed him as president, then in 2006 he was succeeded by the current leader, Lieutenant General Choummaly Sayasone. Choummaly is also a senior citizen (he turned 77 in 2013); nothing is known of his activities before he joined the party's central committee in 1982, so he may be the first Laotian communist leader who was not a senior Pathet Lao member during the long war against the French, royalists, rightists, South Vietnamese and Americans. In 1991 a new constitution was approved that removed all references to socialism but kept Laos a one-party state.

As the twenty-first century began, Laos remained very backward and pastoral. Vientiane (population 750,000) is the only city with more than 50,000 people; the rest are more like American suburbs. We saw in the previous chapter that Laos had strategic value during the Indochina Wars, for its location in the middle of mainland Southeast Asia, but since peace arrived, the country has been off the beaten path. In addition, Laos is one of the two landlocked countries in the Far East (the other is Mongolia), always a hindrance to transportation and commerce. Per capita income reached $1,303 in 2012, up from $90 in 1983, but still extremely low by world standards (it makes Laos richer than Burma and Cambodia, anyway). The main reason why there aren't more calls to raise the standard of living is because the typical Laotian has never known wealth, and is content with his or her lot in life. This laid-back optimism is known as sabai di, literally meaning "feel good." The same easygoing attitude allows them to accept Vietnamese control of their defense and foreign policy; while the Soviet Union existed, this made Laos the satellite of a Soviet satellite.

With no organized opposition, and the continued support of Vietnam, the position of the Lao People's Revolutionary Party looks secure. Nowadays the party is Marxist/Leninist in name only, a dictatorship whose main goal is to perpetuate its total control of the government. There are also increasing concerns about corruption; far too much of the country’s limited resources go to a small elite, who pay little or no taxes. The country enjoyed a milestone when the Asia-Europe Summit was held there in November 2012; this was the largest international conference Laos has hosted so far. But just one month later Sombath Somphone, an American-educated humanitarian, disappeared, and his family posted a blog (Sombath.org) and video that showed him being abducted, presumably by the government. This has hurt the international standing of Laos, and raised questions on whether the Laotian regime is willing to observe the rule of law and human rights. Finally, dictatorships lose their legitimacy when the lives of the people don't improve. We saw it happen with Ne Win in Burma, and Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines; someday the Laotian people could reach even the limits of their patience. Care will be needed to maintain power and keep the country together when that happens. It remains to be seen whether the party will be resourceful enough to meet future challenges.

This flag may be more appropriate than the official one.

The Philippines: People Power

In 1980, Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino suffered a heart attack. Imelda Marcos persuaded him to go abroad for the bypass surgery he needed; a move that exiled him, though he did get better. He and his family spent the next three years in Boston, a time which his wife Corazon later called the happiest period of their lives. But soon he realized he was getting nothing done in America and decided to go back, concluding that, "If I stay here, I'll just be another forgotten politician in exile." Imelda and many others warned that he would be in danger, but he returned anyway, only to be shot dead as he stepped off the airplane in Manila. Another man, presumably the gunman who fired the fatal shot, was killed at once by the nearest soldiers.

It is unlikely that Ferdinand Marcos himself ordered the assassination, since the now-ailing president was recovering from a kidney transplant at the time, but his cronies were certainly in a position to do it. That is what most Filipinos believed, while Marcos tried to put the blame on the communists. Fabian Ver and 25 other soldiers were indicted, but when the long trial ended in December 1985, all the defendants were acquitted. Despite years of investigations, the truth has never emerged concerning who actually planned the shootings, and perhaps it never will.

Nothing affects the Filipinos as much as martyrdom. More than one million people attended Ninoy's funeral procession; he was hailed as another Jose Rizal; some even called his death a "crucifixion," to be followed by a "resurrection" in the eyes of the people. Opposition to the Marcos regime, always fragmented before, united around Corazon ("Cory"), who had been an apolitical housewife until now. The movement came to be known as Lakas ng Bayan ("People Power"), with the color yellow as its symbol.

To show he was still in control, Marcos called for a snap election in February 1986, one year before his current term in office was due to end. Normally he would have won easily, given his control over the electoral process, the media, and his opponent's lack of experience. But Corazon Aquino got the help she needed to run an effective campaign. A seasoned politician, Salvador Laurel, ran as her vice-presidential candidate; the leader of the Philippine Catholic Church, Cardinal Jaime Sin, advised her every step of the way; most of all, the campaign was closely watched by the rest of the world. When Marcos tried to steal the election, Western television broadcast scenes of thugs stealing ballot boxes or bullying voters. When nobody could agree on who won, both candidates claimed victory, and Marcos and Aquino took the oath of office in different parts of Manila on the same day.

The stage was set for a showdown, with Marcos and the military against Cory and most of the civilian population. The critical turning point came when two Marcos loyalists, General Fidel Ramos and Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile, barricaded themselves in an army camp and declared themselves for Aquino. As other soldiers defected to them, tanks were brought out to crush the rebellion. Violence was averted, however, by an event that many saw as a miracle. Thousands of Aquino supporters, led by members of the clergy, blocked the streets with their bodies; the tank drivers chose to join the opposition rather than massacre unarmed civilians. Marcos turned to the United States for help, and was provided with a plane to escape. The entire first family flew away to Honolulu, where the ex-president lingered on a life support machine until he died three and a half years later. Back in Manila, looters broke into Malacanang Palace, to discover what their taxes had been used for; the palace was full of merchandise from Imelda's shopping, including 3,000 pairs of shoes.

A sample of Imelda's shoe collection.

Cory soon learned that throwing out Marcos was just the first step in rebuilding the nation. The economy stopped tumbling, but recovery was hindered by the birthrate of the population, which is doubling every 25 years. And the problem of corruption continued; in 1988, for example, it consumed $2.5 billion, or one third of the national budget. Cory herself was above suspicion, but she was accused of being so sincere that she didn't realize the people around her were insincere. The tales of corruption sounded a lot like what went on before 1965, as if the upper-class families displaced by Marcos wanted to make up for twenty years of lost time: smuggling, kickbacks on government contracts, fake licenses, payoffs to cops, etc.(15)

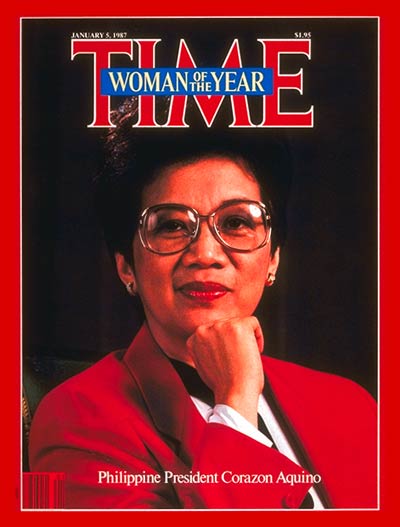

Because of the People Power Revolution, Time Magazine declared Corazon Aquino "Woman of the Year" for 1986.

Marcos was the best recruiter the rebels had. During the years of martial law the New People's Army grew from a few hundred members to about 25,000. They made a grave error, however, when they boycotted the 1986 elections. After Marcos left individual rebels started deserting, giving the Aquino government the upper hand in the struggle. On Mindanao the NPA gained a new enemy in the form of two anticommunist vigilante groups: Alsa Masa ("Up With the Masses"), which single-handedly cleaned the NPA out of Davao City, and the Tadtad ("Chop"), a bizarre cult of cannibals that believed beheading communists was their purpose in life. By 1993 internal feuds, defections, and government military drives had made the NPA a marginal force in most provinces, but guerrilla movements in this part of the world tend to last for generations, so even now the government is talking peace with the last of them.