| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Latin America and the Caribbean

Chapter 5: Uncle Sam's Backyard, Part I

1889 to 1959

This chapter is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| Uruguay's Welfare State | |

| The United States Occupation of Haiti | |

| Argentina: The Radicals In the Saddle | |

| The Mexican Revolution, Phase 2: Moderates vs. Radicals | |

| Independent Cuba: The Early Years | |

| Guatemala: A Cultured Brute and a Napoleon | |

| Brazil: The Old Republic | |

| Honduras: La Republica de los Bananas | |

| Chile: Parliamentary and Presidential Republics |

Part III

| Ecuador: The Leftover Country | |

| The Mexican Revolution, Phase 3: Coming Full Circle | |

| The Dominican Dictator | |

| The Chaco War | |

| El Salvador: The Coffee Republic | |

| Uruguay: The Terra Era | |

| The Somoza Dynasty, Act One | |

| Panama: The Bisected Protectorate |

Part IV

| The Infamous Decade | |

| Getúlio Vargas and the Estado Nôvo | |

| Colombia: "The Revolution On the March" | |

| The Battle of the River Plate | |

| Bolivia: Contending Ideologies | |

| Cuba: Batista's First Reign | |

| Venezuela In Transition | |

| The Rise of Juan Perón | |

| Haiti: Elections and Coups | |

| Peru: APRA vs. the Army | |

| Paraguay: The Rise of the Colorados | |

| Costa Rica: The Unarmed Democracy | |

| "There's No Place Like Uruguay" | |

| The Bolivian National Revolution |

Part V

| Cuba: The Auténticos and the Second Batistato | |

| Puerto Rico: "Candy-Coated Colonialism?" | |

| The Ten Years of Spring | |

| After the Mahogany Rush | |

| Getúlio Vargas, Back for an Encore | |

| The Perón Decade | |

| La Violencia | |

| Venezuela: Back In the Barracks | |

| A Word on the Guianas | |

| The Cuban Revolution |

The Big Picture

We will begin this chapter by summarizing three trends that were important in all of Latin America in the late nineteenth/early twentieth century: growing trade with the rest of the world, the rise of US domination over this region, and the first social revolutions.

Latin America's Role in the World Trade Network

The first trend began in the middle of Chapter 4; we saw that by 1870, the worst of the political chaos following independence was over, and this attracted foreigners with money to invest. They built railroads, started industries, and otherwise sought to make money by connecting Latin American foodstuffs and raw materials with the world economy. From this came sixty years of almost interrupted growth, ending in 1930.

Exports at this stage fell into three categories: temperate zone products, tropical zone products, and minerals. Temperate zone products are European-style meat, grains and produce, from the southernmost part of South America, the "Southern Cone" (see footnote #32). Tropical zone products, which include sugar and coffee, come from anywhere else in the region; in Central America, the dependence of local economies on one or two fruits has led to the derisive term "Banana Republic," used to describe third-world countries with poor economies and corrupt governments.(1) Because most of Latin America's mountains run along the Pacific coast, most of the region's minerals come from there; add to that petroleum from places like Venezuela.

In most of Latin America caudillismo had not yet ended; the dictators just changed their tactics to cope with a changing world. The military continued to act like a branch of the government in many countries, and caudillos like Mexico's Porfirio Diaz learned it was worth the effort to make friends with businessmen, especially foreign businessmen. A caudillo with access to foreign money could make his friends rich and win over at least some of his enemies.

Naturally, foreign investors wanted to protect their money by putting it in places with stable governments. They didn't care much whether a head of state was elected, or whether he had seized power and was using force to keep the peace--what they wanted the most were no uncertainties. For that reason, they were attracted to Argentina, Brazil and Chile at the beginning of this period, for it looked like those countries had solved their political problems.(2) After 1900, the appearance of stable, democratic rule in Colombia, Costa Rica and Uruguay would attract investors for the same reason. Still, the caudillos knew that most of the investors came from societies that respected the rule of law, so they tried to look good by putting on a show of complying with their own laws. The best example is how they prolonged their rule; in the twentieth century they were more likely to do it by amending the constitution, instead of running roughshod over their opponents like the constitution didn't exist.

The first interruption in this economic "golden age" came with World War I. Trade between Latin America and Europe dropped to a trickle, because travel across the Atlantic was no longer safe, and much commercial shipping was diverted to transport military cargoes. Foreign investment in Latin America, which had reached $8 billion by 1913, stopped for the duration of the war; Germany lost its investments completely. The war also helped to increase US influence in the region, because North Americans could still safely do business with Latin Americans.(3) After the war there was a partial recovery of the trading network, though the Germans didn't come back, being tied down with the problems of the Weimar Republic.

No World War I battles were fought in the Americas(4), so from a Latin American standpoint, the Great Depression was worse. It started with the crash of the New York stock market in 1929, and by 1930 the resulting collapse in commerce was felt worldwide, in every country the United States traded with/invested in. The lopsided nature of Latin American economies, heavy on exports of commodities with hardly any manufacturing, proved to be a liability under these conditions. The buyers of Latin American commodities were not able or willing to make purchases on the scale they did before 1930. And if Latin Americans wanted something they did not make themselves, their chances of getting it were slim and none. Then when World War II came, Latin Americans were back in the situation they had during World War I; the only major power they could easily trade with was the United States. Because of those challenges, Latin America was under pressure between 1930 and 1945, to diversify the economy of each nation and develop the previously neglected manufacturing sector.

Enter the United States

For more than a century the United States has regarded Latin America as its own backyard, hence the title for this chapter. In the period covered by this chapter, US influence/control over the region was near-total, as much as could be possible without sending the US armed forces south to conquer everything. To the average US citizen, Latin America was comfortably familiar, compared with the Old World, a place to make money or to go on vacations. Trips to Latin American cities like Havana, Mexico City and Rio de Janeiro were seen as only a little more adventurous than a trip to a US territory like Hawaii or Puerto Rico. With Cuba and Panama, Americans had so many investments and other interests that they might as well have owned those countries.

The nineteenth century was the age of Queen Victoria, when the British Empire was at its peak, so this time is also called the British century. It seemed that "the Empire on Which the Sun Never Sets" was involved everywhere in the world in those days, and in Chapter 4 we saw how Great Britain replaced Spain and Portugal as the most active foreign power in Latin America. But in the last years of the nineteenth century, a new kid came into town--the United States.

The US was in existence when the nations "south of the border" became independent, but aside from issuing the Monroe Doctrine, it wasn't very active in the region. For most of the nineteenth century, the Yankees stayed within the borders of the United States(5), practicing what video gamers call the 4 "Xs": "explore, expand, exploit, and exterminate (in the case of the Indians)." When they weren't doing that, they were debating issues like slavery and states' rights.

By 1890, for all practical purposes, the Yankees were done. 1890 was the year of the Wounded Knee Massacre, the last important battle of the Indian wars; after that, surviving "Native Americans" were confined to reservations. The slaves had been freed a quarter century earlier, and while the territories of the American West had not yet been completely settled and turned into states, everyone knew it was only a matter of time. Many Americans looked abroad for new frontiers to tame, and the nearest place which fit that description was Latin America. Thus, as the nineteenth century drew to a close, American adventurers, merchants, missionaries, and military men, each group with different motivations, all went forth. This also was the time when industrial output caused the United States to pull ahead of Britain, in terms of wealth and military strength. Just as the nineteenth century was the British century, so the twentieth century would be the American century. The Americans were no longer enemies of the British, but their activity was about to give the British a "run for their money," so to speak. Even before 1900, the US had replaced Britain as the best customer for Brazilian products.

The late nineteenth century was a time when the European colonial powers raced to occupy as much land in Africa and Asia as possible. Before they actually took over, they divided those continents into "spheres of influence," marking where each nation could act freely, without interference from the others. Great Britain, for instance, declared a sphere of influence over India and the lands surrounding it, while France proclaimed one over most of North and West Africa, and the Netherlands proclaimed theirs over Indonesia. In the 1890s, Japan avoided becoming a colony by entering the game as a new colonial power.

The United States refused to play the "sphere of influence" game in the Old World (e.g., the 1899 Open Door Policy was a declaration that nobody could do it with China), and the only time Americans rushed to grab an Old World colony was during the Spanish-American War, when they took the Philippines from Spain. On the other hand, the Monroe Doctrine had given Americans the idea that their sphere of influence was in the western hemisphere, and they were moved to act when they saw Europeans meddling there. We saw an early example in the 1860s, when first European debt collectors, then European troops, invaded Mexico and the Dominican Republic; Americans could not do anything about it during the US Civil War, but once the war ended they threatened to throw the Europeans out by force if they did not leave. Now in the closing years of the century, the European debt collectors were back, meaning Europeans were going to get involved in Latin American affairs again if somebody didn't beat them to it.

The first sign that the game had changed came in 1895, when Britain disputed the border between Venezuela and British Guiana. The current border, the "Schomburgk Line," had been drawn by a German explorer in 1835. However, the British thought the Orinoco River should be that boundary (which would have given them half of Venezuela), while Venezuela thought the Essequibo River was a fair boundary (which would have given them about 60 percent of British Guiana). Because Venezuela could not take on the British Empire, it called on the United States to decide the matter. The US organized an international tribunal, which had two members representing Britain, and two members representing Venezuela (the latter were chosen by the United States, one of them was former US President Benjamin Harrison). The border they unanimously agreed on remained at the Schomburgk Line, with two slight adjustments in Venezuela's favor (the 1897 Treaty of Washington). During the affair, the US Secretary of State, Richard Olney, made it clear that whatever the ruling, the will of the United States would prevail:

"Today the United States is practically sovereign on this continent, and its fiat is law upon the subjects to which it confines its interposition."(6)

It probably goes without saying that the British accepted third party arbitration because they did not want a serious confrontation with the United States. There are probably three other reasons why they chose not to start a war over this: most British citizens did not know they had a territorial dispute in this part of the world; when they found out, they were dismayed to learn that the United States sympathized with the other side; and the upcoming war in South Africa was more important to British interests. Likewise, Latin Americans were happy that the United States stood up for them, though the border settlement did not give Venezuela what it wanted. The dispute was considered settled until Venezuela revived it in 1962, four years before British Guiana became independent Guyana.

The Treaty of Washington was still being ratified when the United States took an even bolder action--its invasion of the last Spanish colonies, especially Cuba, during the Spanish-American War (see below). The Americans were motivated to intervene because of US economic interests in Cuba, and concerns for human rights on the island. Another factor, not often mentioned, was that the United States was developing a new strategic picture of what the Caribbean should look like. Although the Panama Canal had not been dug yet, many Americans expected it would happen soon, and after it was finished the United States would have to control it. And controlling/defending the Canal would be easier if the United States also controlled the territories surrounding it, what US Senator Henry Cabot Lodge called the "outworks."

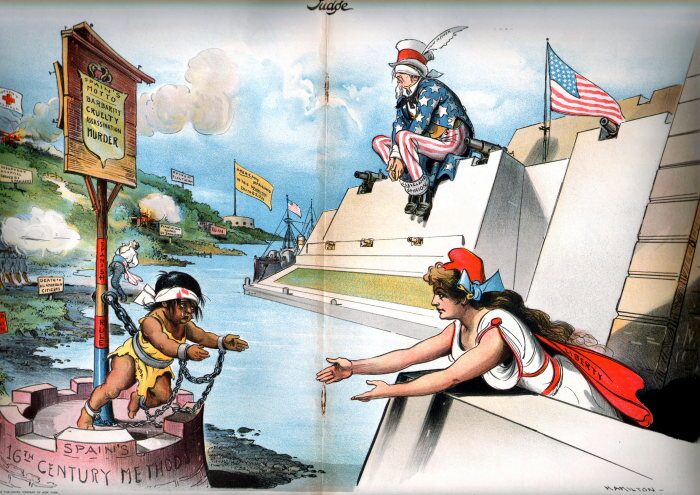

The success of the US ventures in Cuba and Panama encouraged more like them. In a 1904 speech to Congress, President Theodore Roosevelt announced that henceforth, US Latin American policy would be proactive, not reactive. Chronic misrule or the lack of rule in any country called for the most advanced countries to intervene, and in the western hemisphere the United States was the country best suited for doing that, especially to resolve conflicts between Europeans and Latin Americans. This authorization of the United States to act as a regional policeman would be called the "Roosevelt Corollary" to the Monroe Doctrine.

This cartoon shows the Roosevelt Corollary in action.

The Roosevelt Corollary was an extension of Roosevelt's philosophy, act first and think about it later. At the time this was called using the "Big Stick," from Roosevelt's favorite motto ("Speak softly and carry a big stick."). From 1904 to 1933, the United States found several reasons to intervene in the nearest Caribbean and Latin American countries, from assuming control of custom houses for the purpose of collecting debts, to outright invasions for the purpose of restoring order or protecting a threatened US interest. More than once the United States sent troops into Cuba, Mexico, Panama, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua; with the latter three a US-run occupation government was set up for a few years, until that country was straightened out politically and economically. In the cases of the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua, the occupation had tragic results, because the Americans created a new police force in each country, and after they left, the chief of police took charge, becoming a notorious dictator.

Latin Americans hated the Roosevelt Corollary; they saw it as an excuse for their great northern neighbor to barge in and do whatever he pleased, acting like the proverbial bull in a china shop. Three nations were offended more than the rest: Mexico, Colombia and Argentina. The Mexicans still felt bad about losing half their territory to the United States in the 1840s, and resented the more recent US raids on Veracruz and their northwestern states; Colombians were upset at the United States for taking Panama away from them. Argentina was doing so well at the beginning of this period that the Argentines saw themselves as South America's most important country, the "Colossus of the South," so they opposed US policy on principle, figuring that it was their job to keep the North American bully in his place.

Latin America showed its disapproval of the United States when it entered World War I, and urged Latin America to do the same. While no Latin American nation joined the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey), trade with the Americans and the British was not enough to get all of them to join the Allies, either:

- Declared war on the Central Powers: Brazil, Costa Rica, Cuba, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama.

- Broke diplomatic relations with the Central Powers (but did not declare war): Bolivia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Peru, Uruguay.

- Stayed Neutral: Argentina, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Mexico, Paraguay, Venezuela.

World War II left the nations of Europe too weak to hold onto their colonial empires, and because there were active nationalists in several colonies (e.g., India), those empires disintegrated after the war. At first all the action was in Africa and Asia; Europe's colonial powers did not begin to turn their remaining Caribbean colonies loose until the 1960s. Nevertheless, Americans knew that nations like Great Britain and France would not threaten them in the western hemisphere anymore.

But this did not mean they could take Latin America for granted. In 1948, at the latest inter-American conference (held in Bogotá), US General George C. Marshall got the Latin American delegates to promise their cooperation in fighting the newest enemy of the United States, communism. Later in the same year the Organization of American States (OAS) was founded, as a more permanent forum for discussions between the United States and its neighbors. The official stated mission of the OAS was to promote cooperation between its member states, but during the Cold War years it also functioned as a US-Latin American anti-communist alliance.(8)

Sure enough, communists appeared in Latin America during the Cold War, and one of their stated goals was to fight US imperialism, so communism became especially attractive to those with anti-American sentiments. Their activity justified the OAS's existence. In the 1950s, communists and related left-wing groups were busiest in Guatemala, British Guiana, and Cuba; they would spread to other countries in the region later.

A New Kind of Revolution

We noted earlier in this work that Latin American society was basically conservative in the nineteenth century, and so were its revolutions. When a coup or revolution took place, little changed besides the names of those in charge; personalities were more important than political parties. Except for special events like the emancipation of slaves, the ordinary's person's life stayed the same. The closest thing to class warfare was the struggle for independence (see Chapter 3), because European-born whites (Peninsulares) fought on one side and American-born whites (Creoles) fought on the other side; aside from their places of birth, both held most of the land and money, and both had the same outlook on the world.

After independence, the social structure did not change until the economy did, through trends like industrialization. With that came new classes, a merchant/business class and a working class, and new ideas, new ideologies. These people were not locked into tradition; for them the old way of running things would not do. From the most successful nations they learned that they should have equality in law, free elections, universal education and universal suffrage. After the twentieth century began, land redistribution, minimum wages, and some kind of government-guaranteed insurance were added to the wish lists of reformers. And because this was also the age of rising nationalism, many reformers wanted to end the control or influence that foreigners had over their nation's economy (often they called it "neo-colonialism").

When reformers could not get what they wanted peacefully, they became revolutionaries, and sought to impose their ideas by force. There were two ways to do this. One way was a bit traditional; they found a caudillo who agreed with them, and backed his bid for power. Two of the best examples of dictators who would champion the causes of their subjects were Juan Perón of Argentina, and Getúlio Vargas of Brazil. The other way was a "social revolution": all-out warfare between social classes, where the revolutionaries supported one class in its efforts to impose its will on the other classes. Social revolutions happened in Europe during the nineteenth century, and all over the Old World in the twentieth. In Latin America, the twentieth century was half over before they became commonplace. Among the early social revolutions, the three biggest were the Mexican Revolution (1910-20), the Bolivian National Revolution (1952), and the Cuban Revolution (1953-59). Because the Cuban Revolution also installed a government that would become a major challenge to the United States and the Monroe Doctrine, this chapter will end with Fidel Castro's triumph, leaving all of his long dictatorship for the final chapter of this work.

And now let's resume the narrative . . .

"Cuba Libre!"

Since the beginning of Chapter 2, Spain has been one of the most important players in this narrative. Now we are going to see the Spaniards for the last time.

In Chapter 4, we saw that the residents of Cuba and Puerto Rico did not develop a sense of nationalism until the 1860s, long after the mainland colonies had won their independence. Consequently they experienced a corrupt, inept colonial government at its worst. When nationalists did appear, they launched two rebellions, the Ten Years' War (1868-1878) and the Little War (1879-1880). Although these were bigger than previous uprisings, Spain still managed to put them down. The only thing settled by the rebellions was that Spain was persuaded to do away with slavery. Because the nationalists were incompletely satisfied, it was inevitable they would come back for a rematch.

Another factor was the proximity of the United States. Only ninety miles of water separate Havana from the nearest US city, Key West, so it made sense for Cuban refugees to go to Florida.(9) Revolutionaries also came to the US mainland to recruit soldier-adventurers, raise money, and acquire arms and ammunition; to smuggle people and supplies back into Cuba, they would use small boats, and land them on the east side of the island (most of the patrolling Spanish ships and men were on the west side, near Havana).

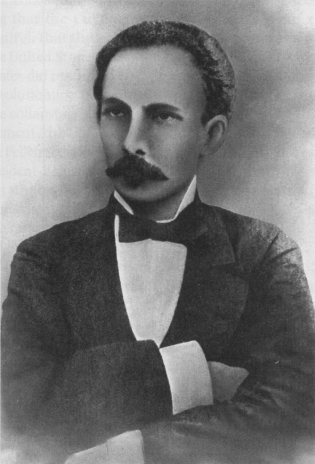

The most important revolutionary was José Martí--a poet and journalist that Cubans later proclaimed their national hero. In his prolific writings, Martí voiced the desire of Cubans for a nation of their own, and warned against getting absorbed into the US, even if the Americans were helpful to the nationalist cause. Spain exiled him for criticizing the Spanish government and stirring up opposition to it, and he moved to the United States in 1881, supporting himself by writing and making speeches. When Spain imposed new taxes and canceled a trade pact between Cuba and the United States, it impoverished the Cubans so badly that Martí saw his opportunity. In 1895 he returned, landed near the southeastern port of Santiago, and declared the independent Republic of Cuba, while two of his generals, Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo, led the guerrilla army in a campaign that captured the east half of the island and invaded the west. Martí was killed in a skirmish just a month later, and Maceo was killed in an 1896 battle, but the revolutionaries found another capable general, Juan Rius Rivera, to replace Maceo.

|

|

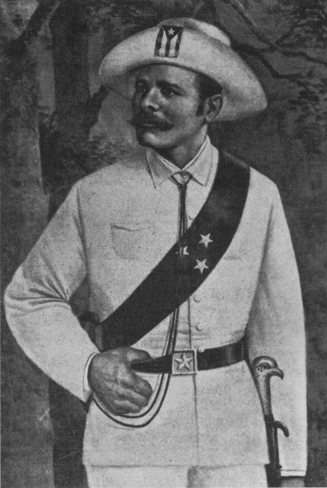

| Antonio Maceo. | José Martí. |

|

|

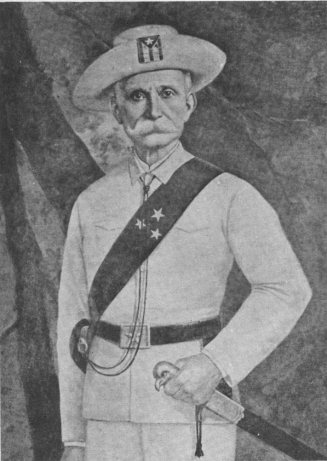

| Máximo Gómez. | Valeriano Weyler. |

The rebel offensive bogged down in 1896 when the Spanish government replaced its first military commander, Martínez Campos, with Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, who soon became known as El Carnicero ("The Butcher"). In order to deprive the revolutionaries of the rural support on which they depended, Weyler instituted a brutal program called "reconcentration"; as many as 400,000 Cubans (one fourth the island's population) were forced into camps in the towns and cities, where half of them died of starvation and disease.

As the war went on, Americans grew increasingly concerned. They had acquired a sweet tooth for Cuban sugar, and the war was ruining Cuba's sugar industry--which threatened American investments and property. Moreover, this was the age of yellow journalism; William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer's New York World were competing to see who could sell the most newspapers. They enraged the American public with stories and pictures of the war, which were not always properly researched. As one World reporter put it: "Blood on the roadsides, blood in the fields, blood on the doorsteps, blood, blood, blood. Is there no nation wise enough, brave enough, and strong enough to restore peace in this blood-smitten land?" When those newspapers found that Cuban blood was a great way to get readers, they poured it out with every edition.

US President Grover Cleveland ignored calls for American intervention, but in 1897 he was succeeded by William McKinley, and the pressure to do something about Cuba grew so great that Washington issued an ultimatum to Spain: if Spain did not end the war, either by winning or by negotiating a settlement, the Americans would end it. Spain chose to negotiate; it recalled General Weyler, offered home rule to Cuba, and ended reconcentration.

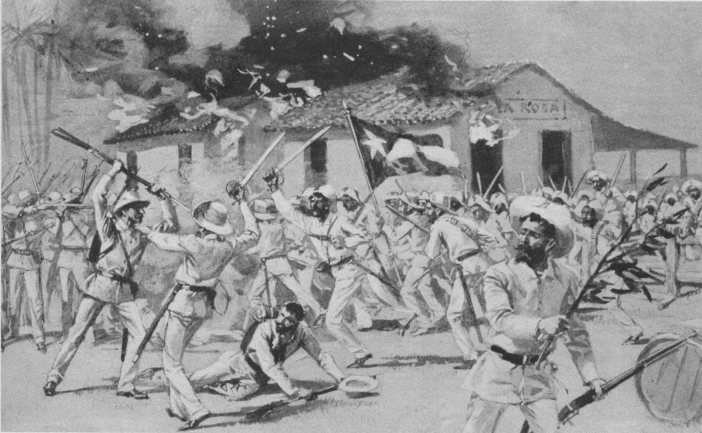

A scene from the battle of La Rosa, where revolutionaries shouting "Cuba Libre!" charged loyalist volunteers.

At that point, in early 1898, an American battleship, the USS Maine, sailed into Havana's harbor to guard US citizens and their property in the capital. Three weeks later, the Maine suddenly blew up. Today we believe the explosion was an accident, and Spain denied any wrongdoing, but back then American feelings toward Spain were so bad that everybody assumed it was a Spanish atrocity. Although the Spanish and American governments did not want war, the American people did, having been whipped into a frenzy by the yellow journalist press. The course of the Spanish-American War has already been covered in the North American history series on this website, so click on the link if you're not familiar with the details. For now I will say it was a cakewalk for the Yankees; they occupied Cuba, Puerto Rico and Guam in just ten weeks, and sank the Spanish Pacific Squadron in the Philippines, so with that, the Spanish Empire ceased to exist.

Costa Rica: King Banana

In the previous chapter, we saw Costa Rica strike it rich by growing coffee in the country's Central Valley, and how an American entrepreneur, Minor Keith, constructed a railroad from the Central Valley to the Caribbean coast, to make exporting coffee easier. However, building the railroad through mountains, jungle and swamp cost way too much, in both money and lives. In the 1870s, Keith had planted banana trees near the tracks as cheap food for his workers. By the time the railroad was finished, in 1890, Keith was desperate to recover what he had spent, so he shipped a cargo of bananas to New Orleans. Bananas had not been popular outside of the tropics previously.(10)

Keith thought he was starting a new venture on the side, because after all, coffee was king in Costa Rica, but what a happy accident this was! Once they discovered the fruit, Americans loved it. Keith then shipped bananas to other US ports, starting with Mobile, Alabama. Outside of the Central Valley, banana plantations replaced jungles. In 1897 he bought 50% of the shares in a company that grew bananas in Panama; in 1899 he merged his company with Andrew Preston's Boston Fruit Company to form the United Fruit Company (UFC).

A few years later, bananas led to the invention of a new fashion, popularized by Carmen Miranda.

This marked the beginning of the United Fruit Company's story. To the world it would give the first examples of two new concepts: the multi-national corporation and the banana republic (see footnote #1). In less than ten years, bananas replaced coffee as Costa Rica's primary export. By taking over more than twenty competitors, the United Fruit Company acquired a near monopoly, bringing in 80 percent of the bananas consumed by the United States, and becoming the largest employer in Central America and the Caribbean.

Unfortunately for Costa Rica, most of the profits were exported along with the bananas; that hadn't been the case with coffee. When the UFC brought in black migrant workers from Jamaica, it changed Costa Rica's ethnic makeup and provoked racial tensions. The UFC controlled its workers with a combination of paternal behavior and violence; Latin Americans called it El pulpo, the octopus, because it had its tentacles in the economy and the government. The UFC owned huge tracts of land, much of the transportation & communication infrastructure, and plenty of bureaucrats; throughout Central America it supported repressive dictators, and was probably behind more than one coup that installed them.

But when it came to dictators, Costa Rica was the exception to the rule. Already in the nineteenth century, the country was moving away from the caudillo pattern that characterized so much of Latin America. By the early twentieth century, it had enacted social reforms like free public education, a guaranteed minimum wage and child protection laws.

The first major challenge to Costa Rica's democracy came in 1917, when General José Federico Alberto de Jesús Tinoco Granados and his brother seized power in a coup, and tried to crush all opposition with a repressive military dictatorship. At first he won some support from the upper classes because he cancelled the austerity measures introduced by the previous president, Alfredo González. Although he declared war on Germany in May 1918, his government never won recognition from the Uinted States. In the summer of 1919, popular sentiment turned against Tinoco, and quickly increased, led by schoolteachers and students. When his brother was assassinated in August, Tinoco got the message, resigned, and went into exile in Europe.

The War of a Thousand Days

Colombia has been more committed to keeping the democratic tradition alive than any other South American country; that's why it only experienced two coups in the nineteenth century (see Chapter 4). But that doesn't mean the country was at peace the whole time. Nor did political disorder cease, when a new constitution was adopted in 1886. Instead, under the long presidency of Rafael Núñez, both the Conservative and Liberal Parties split into moderate and extremist factions. Núñez mainly succeeded in keeping a lid on the discord between these groups; as if to show this, the extremist Liberal faction staged a revolt after he left office (1895). It failed, though, and the Conservatives maintained their grip on the presidency.(11)

In 1898 Manuel Antonio Sanclemente, another Conservative, was elected president. But Sanclemente was too ill to run the country, so many of his duties were passed to his vice president, José Manuel Marroquín. The arrangement didn't work out because the world price of coffee fell at the same time; this reduced customs revenues, and the government went bankrupt. Declaring that the latest elections had been fraudulent, the Liberals launched a civil war in 1899, which we call the War of a Thousand Days.

With Venezuelan support, the Liberals were winning at first, until they suffered a crippling defeat at the hands of a larger Conservative force (the battle of Palonegro, May 26, 1900). After that, the Liberals could no longer maintain a conventional army, and used guerrilla tactics for the rest of the war. But this didn't mean the Conservatives had an easy time of it. When money was really tight, the Conservatives tried to pay their army with "tickets," which the troops refused to accept. On July 31, 1900, the moderate faction of the Conservative Party ousted Sanclemente in a coup, thinking that if Marroquin was the official president instead of the acting one, he would seek a political solution to the war. To their surprise, Marroquin adopted a hardline and refused to negotiate a settlement.

The war continued for two more years after that. Most of the fighting was in Panama and along the Caribbean coast, though every part of Colombia saw battles at one time or another. To outsiders this part of the war must have seemed pointless; each side was interested in little besides killing as many enemies as possible. At the end of it, the Liberals conceded defeat and both sides signed a treaty on a US battleship, the Wisconsin (November 20, 1902). The war had killed more than a hundred thousand Colombians and left the country devastated. Because of the war, Colombia was too weak to prevent Panama from breaking away as a separate nation in 1903 (see below), meaning that the country would soon be humiliated, too.

The First US Occupation

It took until December 1898 for the last Spanish troops to leave Cuba, and for Spain to sign the treaty ending the war, so US administration of the island officially began on January 1, 1899; the first governor was General John R. Brooke. Even before the United States declared war on Spain, Americans decided that the Cuban revolutionary movement was legitimate, so they would not occupy Cuba permanently. Still, they wanted an independent Cuba to be friendly, which in those days also meant compliant. In turn, leaders of the Cuban revolution like General Calixto Garcia did not resist American troops, the way Emilio Aguinaldo did in the Philippines. Indeed, Tomás Estrada Palma, José Martí's successor, dissolved the Cuban Revolutionary Party a few days after the treaty was signed, claiming that all the objectives the party had been fighting for were met. Later in the same year, General Leonard Wood, the former commander of the Rough Riders, succeeded Brooke as governor. Wood used the US Army in a public health campaign to fight diseases like yellow fever, and the mosquitoes that carried the diseases; he also organized an education system to build primary schools in Cuba.

While everyone agreed that political independence should be granted before the Americans wore out their welcome, nobody said anything about economic independence. Once order had been established and the work of repairing the island from decades of war began, American capital poured in. The wars certainly left a vacuum for them to fill, as shown by the number of sugar mills; there were 2,000 of them in 1860, but only 200 in 1899. By 1902, American companies controlled 80% of Cuba's ore exports, 40% of sugar production, and owned most of the cigarette factories. The growth of American-owned sugar plantations was so quick that by 1905, nearly 10 percent of the island belonged to US citizens. A 350-mile railroad was built, linking Santiago in the east with existing railroads in central Cuba.

When the time came for elections, besides electing mayors and other officials, it was necessary to elect delegates for a constitutional convention. But Governor Wood favored the upper class, which he called the "better class"; this included Spaniards who had not left the island and conservatives who had been against independence. To give them the advantage, he restricted voting rights to literate men over the age of 21, who owned property worth more than $250. Only former members of the revolutionary army were exempt from these requirements. This reduced the number of voters from 418,000 men to 151,000; all women and most black Cubans were excluded. Elihu Root, the US Secretary of War, liked the last result; he wrote that limited suffrage kept out "so great a proportion of the elements which have brought ruin to Haiti and San [sic] Domingo." Predictably, the first elections, held in 1900, produced politicians and a constitution that were conservative and pro-American. The most controversial part of the constitution was the Platt Amendment, which was adopted in 1901 after several months of debate and intense US pressure.(12) This amendment made Cuba a US satellite state in the following ways:

- Cuba would not transfer Cuban land to any power other than the United States.

- The United States had the right to intervene in Cuban affairs or occupy Cuba when the US authorities considered that the life, properties and rights of US citizens were in danger.

- Cuba was prohibited from negotiating treaties with any country other than the United States "which will impair or to impair the independence of Cuba."

- Cuba was prohibited to "permit any foreign power or powers to obtain lodgement in or control over any portion" of Cuba.

- The Isle of Pines would not be considered part of Cuba until the title to it was adjusted in a future treaty (that happened in 1925).

- The United States could buy or lease land needed for naval bases or coaling stations.

Presidential elections were held on the last day of 1901. At first the two candidates were Tomás Estrada Palma and General Bartolomé Masó, but Masó accused the United States of favoritism and withdrew from the race, allowing Palma to win without opposition. Palma had been president once before--of the Cuban government-in-exile, during the Ten Years War. Now he was in his sixties, and for the past twenty-five years he had been living in the United States, as a US citizen, so he had to return to Cuba before he could take office. His term began on May 20, 1902, and that marked the end of the US occupation.

Mt. Pelée Kills St. Pierre

While the Americans were turning Cuba loose, the worst volcanic disaster of the twentieth century struck in the Caribbean, on the French-ruled island of Martinique. Mt. Pelée, the volcano on the north side of Martinique, had shown it was active by erupting in the past, but those were minor eruptions, not big enough to prevent the nearby building of Martinique's largest town, St. Pierre. When more minor eruptions and earthquakes occurred in early 1902, the island government told everyone St. Pierre was safe, and urged the residents to stay so they could vote in the elections scheduled for May 11; the governor even sent troops to the road going between St. Pierre and Fort-de-France, to turn back refugees trying to escape to the latter town. The election never happened, because the big eruption came on May 8, 1902; a pyroclastic flow (a large black cloud of superheated gas, ash and rock) rolled straight down the mountain at more than 100 miles per hour, destroying every building in St. Pierre in just one minute. A second eruption on May 20 wiped out what was left, including the two thousand rescue workers who had arrived by that time. St. Pierre has not recovered since then; whereas the population was an estimated 28,000-30,000 right before the May 8 eruption, the community on that spot today has only 4,544 people (2004 census).

When Italy's Mt. Vesuvius famously erupted in the first century, quite a few people in the area managed to escape, but Mt. Pelée's first major eruption left only two survivors. One, a young shoemaker named Léon Compere-Léandre, was badly burned in his house, but because he was in better-than-average health, managed to run out of town and stay alive. The other was a prison inmate, Ludger Sylbaris (Louis-Auguste Cyparis in some texts), who had been put in solitary confinement for getting into a barfight or street brawl the night before the big eruption. His poorly ventilated cell was the only real underground shelter in town, and that saved his life, though he suffered burns as well. Four days later, rescuers heard him crying for help, and got him out of the ruined prison. Sylbaris was subsequently pardoned and went on to join the Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus, becoming the first black man to star in that show, as "the man who lived through Doomsday."

or "I'm Dreaming of a Wide Isthmus"

The Caribbean was not the only theater of the Spanish-American War; US ships also went to the Philippines to defeat the Spanish squadron at Manila. Because it took weeks to transfer ships between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the war reminded Americans how convenient it would be, if they had a direct connection between the oceans that was closer than the Straits of Magellan. By the end of the nineteenth century, proposals to dig such a canal had narrowed to two locations, either across Nicaragua or across Panama. The route for a Nicaraguan canal was 170 miles, compared with less than fifty miles at Panama's narrowest point, but Nicaragua was high and dry by comparison, and the country's rivers and lakes meant engineers would not have to dig all the way across to create a canal. After the French effort to dig a canal across Panama failed in the 1880s (see Chapter 4), American opinion favored the Nicaraguan route.

It was the chief engineer of the defunct French company, Philippe Bunau-Varilla, who singlehandedly persuaded the Americans to go for the Panamanian route, by offering to sell them the rights to dig a canal there (he was trying to recover some of his company's losses). The leader of the US Republican Party, Mark Hanna, liked the proposal so much that he made it a campaign promise in the presidential election of 1900; Congress and the next US president, Theodore Roosevelt, agreed to do it in 1902, paying $40 million to the stockholders of the French company. Then, because the British Navy still ruled the waves, the Americans got the British to sign a treaty promising not to interfere with US efforts to dig the canal.

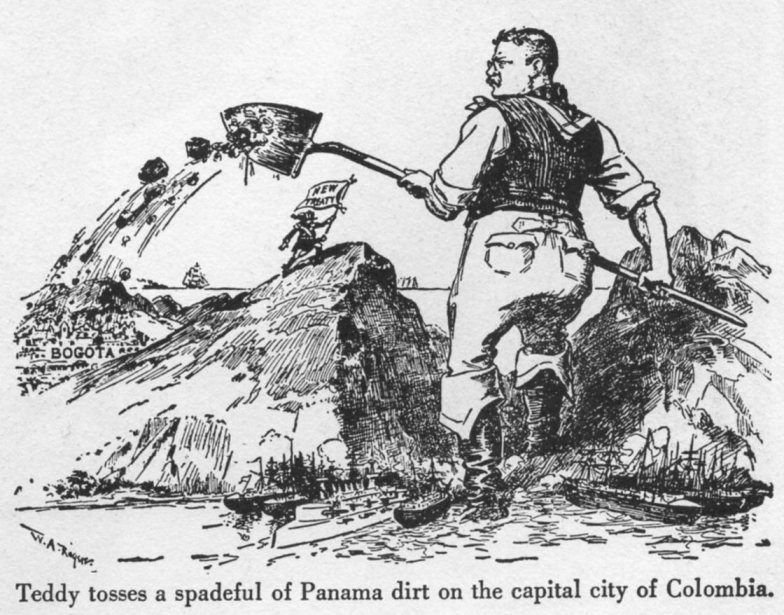

The territory in question belonged to Colombia, and because of the War of a Thousand Days, the Americans waited until they had everyone else's approval before asking the Colombian government what it thought of a US-dug canal across the isthmus. Their offer to Bogotá was this: in return for a 100-year lease on a 10-kilometer-wide strip across the isthmus, the US would pay $10 million up front and $250,000 each year. Colombian diplomats agreed to those terms, what we call the Hay-Herrán Treaty, in January 1903, but the Colombian Senate rejected them.(13)

At this point Roosevelt thought it might take a war to get Bogotá to see things his way--he would at least have to send US troops to occupy the isthmus and protect the workers digging the canal--but there was another option. Though they had been under Colombian rule since declaring independence from Spain in 1821, some residents of the isthmus never really saw themselves as Colombians. Their feeling was reinforced by geography; an impenetrable jungle, the Darien Gap, separated Panama City and Colón from the rest of Colombia (see Chapter 3). Indeed, the only way Colombians could go to Panama was by sea. In the nineteenth century there had been a few Panamanian revolts (the most recent, in 1885, devastated Colón), but the Colombian armed forces put each one down within a year. After the 1886 Colombian constitution put Panama under direct rule of the central government, the US consul general reported that three-quarters of Panamanians wanted independence, and would revolt if they could get arms and be sure of freedom from US intervention. Now, because Colombia's recent civil war had turned Panama into a battleground, anti-Colombian resentment was particularly high.

In July 1903, eight Panamanians, taking advantage of US interest in Panama and Bogotá's rejection of the Hay-Herrán Treaty, created a revolutionary junta, led by José Augustin Arango, an attorney for the Panama Railroad Company. They might not have gotten any further than previous revolutionaries (and I probably would not have even mentioned them), if the French lobbyist, Philippe Bunau-Varilla, had not gone into action. From a suite in the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City, Bunau-Varilla encouraged the Panama City fire department to rise up against Colombia. While in the hotel, he also wrote the Panamanian declaration of independence and designed the Panamanian flag, though he had not been in Panama for seventeen years and would never go back there again. An American gunboat, the USS Nashville, immediately sailed to Colón, where a force of 474 Colombian soldiers had landed and was preparing to cross the isthmus and crush the rebellion. A small party of troops disembarked from the Nashville, and with the support of the American superintendent of the Panama Railroad, kept the Colombians from taking the train to Panama City.(14)

President Roosevelt recognized the Panamanian junta as the country's first government on November 6, 1903. For being the midwife in delivering Panama's independence, Bunau-Varilla was made the first Panamanian ambassador to the United States. In that position, he negotiated with US Secretary of State John Hay, and the result, the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, gave the US even more generous terms than the Hay-Herrán Treaty did; among other things, the lease would be permanent, not for a hundred years, the width of the canal zone would be increased from ten kilometers to ten miles, and the US would have the right to intervene in Panamanian affairs. The Panamanians may have felt Bunau-Varilla was acting too hastily, but because they did not see any alternative to those terms, they ratified the treaty, and so did the US Senate. As for Colombia, it did not recognize Panama as an independent nation until 1921, when the US paid Colombia $25 million in "compensation."

The US canal builders learned from the mistakes of the French. A few years earlier, scientists figured out that malaria and yellow fever were carried by mosquitoes, so the first task on the agenda was to eradicate the mosquitoes in the Canal Zone. Colonel William Crawford Gorgas was put in charge of health and sanitation, and his work crew spent two years making sure the Americans would not suffer as much from disease as the French did. A clean water supply and sewers were provided to the cities, buildings got screens and fumigation, standing water was drained or sprayed with oil; churches even had to replace their holy water, because mosquitoes bred in it. At one point the colonel in charge of the digging, George Washington Goethals, told Gorgas that every mosquito killed was costing the United States $10, and Gorgas replied, "I know, Colonel, but what if one of those ten-dollar mosquitoes were to bite you?" Malaria and yellow fever were wiped out; Gorgas is credited with saving at least 71,000 lives and some 40 million days of sickness.

Next came the actual digging. The paths in the earth left by French shovels would be used, but instead of a sea-level canal, it was decided by this time that a canal with locks, going over the central ridge instead of through it, would suffer fewer mudslide accidents. In the process of doing this, a dam was built on the Atlantic/Caribbean side of the ridge, to create Gatun Lake, and the Culebra Cut (also called Gaillard Cut) was carved through the continental divide. Three sets of locks were built on the Atlantic end of Gatun Lake, and another three sets went up on the Pacific end of Culebra Cut. For most of the twentieth century, Panama's chief source of revenue would come from the tolls charged on ships using the locks.(15) The first ship went through the canal on August 15, 1914, and the whole project was declared complete in 1921. While the French effort to dig the Canal is one of the greatest tragedies in the history of engineering, the American effort is one of engineering's greatest triumphs (if you don't count this mistake).

Peru: The Aristocratic Republic

After the War of the Pacific, Peru experienced political chaos for the rest of the nineteenth century, like what it went through in the first years after independence. During the war, one Peruvian general, Miguel Iglesias Pino de Arce, fought the Chilean occupation from northern Peru, while another general, Andrés Avelino Cáceres Dorregaray, fought from the Andes. It was Miguel Iglesias who signed the Treaty of Ancón by representing Peru at the war's end, he automatically became the first president after the occupation. Miguel Iglesias was in a hurry to get the Chileans out because he felt that if they stayed long enough, Peru would become a colony of Chile, but most of his subjects felt that he had accepted too many concessions to do it. Those who did not accept his leadership waged a guerrilla war, in and around Lima, until he resigned in December 1885. The country was ruled by a junta under Antonio Arenas for the next six months, when Cáceres was elected president.

Order began to return under the two terms of Cáceres (1886-90, 1894-95). He began by crushing the Ancash Uprising, an Indian rebellion in the highlands, led by a former ally, the varayoc (chief) Pedro Pablo Atusparía.(16) However, the new government was broke, and the country needed repairs from wartime damage; Cáceres could not fix those problems by defeating somebody. Instead, he negotiated the Grace Contract with a group of British bondholders (1888). This was a very controversial agreement, which canceled Peru's foreign debt in return for the right to operate the country's railroads for sixty-six years; it also granted a guano concession. Critics accused the president of selling off the country's best assets for a very low price, but in the long run it worked in Peru's favor; the debt was gone, the British expanded the rail network at a time when Peru could not afford to do so, and increasing silver production allowed a favorable balance of trade.

The next president was a crony of Cáceres, Colonel Remigio Morales Bermúdez. He died in office four months before the end of his term, so Cáceres ran again in 1894, and won amid accusations of fraud. His accusers launched uprisings throughout the country, and seven months later José Nicolás de Piérola, who had been president from 1879 to 1881, organized guerrillas to occupy Lima itself.(17) Realizing that everyone was against him, Cáceres resigned and was replaced by an interim junta.

The period from 1895 to 1914 is called the Aristocratic Republic, because most of Peru's presidents during this time came from the social elite. Before 1895 was over, elections were held, and Piérola won a second term (1895-99). Under Piérola and his successor, Eduardo López de Romaña (1899-1903), the Civilista Party, a political party that existed before the War of the Pacific, reorganized itself and revived its anti-military, pro-export platform. The Civilistas did a good enough job of pulling themselves together that they won the 1903 election and ran the country until 1914. Whichever group was in charge, this was a time of rapid growth, especially in sugar, cotton, and mining exports.

However, the Civilistas suffered a serious split in the 1912 election. The official Civilist candidate for president was Antero Aspíllaga, but he wasn't accepted by a faction of the party, which accused him of being a Chilean-born Peruvian unfit for office. They rallied behind Guillermo Enrique Billinghurst Angulo, a former vice president and mayor of Lima. Billinghurst organized a general strike to block the election, and force his own election by Congress. But after becoming president, Billinghurst could not get along with Congress, and Congress tried to impeach him in 1914. Billinghurst threatened to arm the workers and forcibly dissolve Congress, but before he could, the army staged a coup, under Colonel Oscar Raimundo Benavides.

The coup marked the beginning of an alliance between the military and the oligarchy, which lasted until 1968. Unlike previous periods of military rule, coup leaders like Benavides were more professional, less eager to run the country for personal gain. One year after seizing power, he arranged elections to establish a new civilian government.

The first rule of Benavides coincided with the beginning of World War I in Europe. As with other Latin American countries, the war put serious strains on the economy, and that led to social unrest. Trade was cut off while the war went on, and when trade was resumed, there was a round of inflation and strikes. In addition, radical new ideologies came into the country from the recent Mexican and Russian revolutions.

This chaos led to the downfall of the Civilista Party, through a former member. Augusto B. Leguía y Salcedo had been president from 1908 to 1912, but left the party afterwards. Small but energetic (he stood 4' 11" and weighed no more than 100 lbs.), he ran again as an independent in 1919, promising reforms that appealed to the new middle and working classes. When he sensed that the Civilistas weren't going to let him win, he became president by staging a coup.

Leguía's second presidency, the longest in Peruvian history, is called the oncenio ("eleven-year rule," 1919-30). In 1920 he replaced the 1860 constitution with a new one that was more liberal, provided more civil guarantees, and enhanced the power of the state to carry out reforms. After passing the new constitution, however, Leguía ignored it most of the time, not surprising when you recall how he became president.

After a brief, postwar recession, a wave of foreign loans and investment came into Peru. This allowed Leguía to replace the Civilista oligarchy with a wealthy middle class that prospered from jobs in the expanding government bureaucracy. The government grew because of Leguía's public works program, which founded hospitals and banks, built drainage systems around the cities, and remodeled the Government Palace.

Leguía also settled two border disputes, with Colombia and Chile. The dispute with Colombia was caused by the same thing that made Brazil and Bolivia quarrel over another part of the Amazon basin at the beginning of the century: the jungle shared by Peru, Ecuador and Colombia contained rubber trees. With the United States acting as mediator, Peru and Colombia signed the Treaty of Salomón-Lozano in 1922, which established the Putumayo River (a tributary of the Amazon) as the official border, except for the town of Leticia, which was assigned to Colombia, though it is on the Peruvian side of the river. The agreement with Chile, the Tacna-Arica Compromise of 1929, took care of unfinished business from the War of the Pacific, by ruling who owned the provinces in the treaty's name. Both treaties were bitterly criticized by those who thought Peru should not have given up anything.(18)

As the 1920s went on, Leguía became more authoritarian. He cracked down on labor and student activism, exiled political opponents, purged them from Congress, and amended the constitution so that he could run, unopposed, for reelection in 1924 and 1929. The game for him ended when the Great Depression arrived; foreign investments dried up, meaning he could no longer spend money the way he had before. The military overthrew Leguía in 1930, and he was still in their custody when he died in 1932.

Venezuela: The Tyrant of the Andes

We saw in Chapters 3 and 4 that Venezuela suffered more damage from the wars of independence than any other Latin American country. As much as one fourth of Venezuela's population may have died in the wars, because Simón Bolívar fought most of his battles there. And then after independence, Venezuela did not become a real democracy, but was ruled by caudillos for most of the nineteenth century; the first civilian president, Juan Pablo Rojas Paúl, only took charge in 1888. His successor, Raimundo Andueza Palacio, was another civilian who served a two-year term (1890-92), and he made a critical mistake by not relying on the caudillos for support, so when he tried to have his term lengthened, one of his predecessors, Joaquín Crespo, led the revolution against him and took over.

Crespo's second presidency was a colorless dictatorship that lasted for six years (1892-98), with him fighting to hold on most of the time. In the process, he passed a new constitution that increased the president's term to four years, got himself re-elected in 1894, quarreled with Britain over the border with British Guiana (see the beginning of this chapter), and saddled the nation with new debts. But when the results of the 1898 election were disputed, leading to an uprising, Crespo marched forth to put it down, and was killed in battle. A year and a half later, José Cipriano Castro Ruiz, a caudillo who had been exiled to Colombia when Crespo took over, returned with a private army, marched on Caracas and seized the vacant presidency, ruling from 1899 to 1908.(19)

Cipriano Castro was "probably the worst of Venezuela's many dictators," as the historian Edwin Lieuwen put it. US Secretary of State Elihu Root called him "a crazy brute," and his disastrous reign saw rebellions, the murder or exile of his opponents, his own extravagant living, and trouble with European navies. Because he refused to pay Venezuela's debts, British, German and Italian ships blockaded Venezuelan seaports in 1902. Cipriano Castro thought the United States would invoke the Monroe Doctrine and come to his rescue, but instead the Americans held back, after the European creditors promised not to occupy any Venezuelan territory. But when a naval bombardment and a blockade lasting several months produced no results, the US pressured both sides to reach a compromise.

Cipriano Castro picked another fight in 1908, this time with the Netherlands, by expelling the Dutch ambassador. Three Dutch warships retaliated by capturing two Venezuelan ships and blockading Venezuela's ports again. The so-called "Dutch-Venezuela War" ended not because of a battle or diplomacy, but because of Cipriano Castro's health. At this point he was so ill that he went to Europe for treatment, and while he was away his chief military aide, Juan Vicente Gómez Chacón, took this opportunity to overthrow the dictator and put himself in the top spot.

Juan Vicente Gómez was Venezuela's most successful and the longest lasting dictator. Born in 1857, he was a Mestizo with hardly any education, and had been a cattle hand and a landowner before entering politics. He never married, but had more than a hundred children, and provided for all of them.(20) When he wasn't president, he filled the post of Minister of War, with a compliant puppet in the presidential seat. In a similar manner he controlled the other branches of government; the parliament acted as a rubber stamp, drafting and promoting six constitutions to suit his whims, and the judiciary enforced his will in the courts. He also had many titles and nicknames; Congress proclaimed him El Benemérito (the Meritorious One), while opponents either called him El Bagre (the Catfish, referring to his moustache) or "the Tyrant of the Andes." In several ways he resembled Mexico's Porfirio Diaz; like Diaz, he used the army to destroy organized opposition, and a secret police threw thousands of opponents into prison, where death by starvation or torture was commonplace.

Juan Vicente Gómez.

Gómez justified his rule with blatant racism. He explained that because nonwhite Venezuelans were a primitive race living in a primitive economy, they were not temperamentally suited for democracy. What they wanted most was for order to be maintained, so they actually preferred a harsh dictatorship; he called this doctrine "Democratic Caesarism." Likewise, only technologically superior foreigners could build a more advanced economy, and strong authoritarian rule was the only way to provide the stability needed for them to do that.

The secret to the success of the Gómez regime was a great economy and plain luck. Coffee sales and prices rose tremendously, but we have already seen other Latin American nations like Colombia benefit from that. What really put Venezuela on the map was the discovery of oil, at Lake Maracaibo in 1918. Timing helped; the end of World War I made it safe to sell oil to other countries, and Mexico stopped exporting oil while its own revolution raged. Ten years later, Venezuela was the world's number two oil producer, after the United States, and the number one oil exporter. Gómez used petrodollars to pay off all of Venezuela's foreign debt, and most of the internal debt, by 1930. But oil is a mixed blessing; most of the countries that have petroleum as a resource have grown corrupt off it, and Venezuela is no exception. Almost no oil money made it to ordinary Venezuelans; Gómez, his friends, the army and the oil companies got most of it. Moreover, the ability to make a quick profit from oil caused the rest of the economy to be neglected, especially agriculture. The number of jobs declined, and prices rose, and the country chose to import food and everything else it needed from abroad, as long as it could afford it.

Because Gómez never cared much for education, it was natural that the biggest source of opposition to the regime would appear at the Central University of Venezuela, in Caracas. There in February 1928, three students were arrested for making anti-government speeches. Other students showed their solidarity by challenging the dictator to jail them as well; Gómez said okay and arrested 200 of them. The demonstration which followed showed that civil disobedience didn't work on Gómez. Police dispersed the demonstrators by shooting them, killing and wounding many. Then the rebels stormed the presidential palace, which they managed to occupy briefly before the army took it back. Gómez closed the university, and put many of the students to work on road gangs, while other activists went to prison. Some members of the movement, like Rómulo Betancourt, Rafael Caldena Rodríguez, and Raúl Leoni, escaped into exile; they were called "the Generation of 1928" and would become Venezuela's leaders at a later date. As for Gómez, he remained master of the state until he died from natural causes, in 1935.

Colombia: The Conservative Republic

The devastation that resulted from the War of a Thousand Days discredited the extremist factions of the political parties. The moderates who assumed power in each party had similar economic interests, and believed they needed to learn to live together, for the good of the country. For the first time in Colombian history, the Liberals and the Conservatives deliberately shared power; Conservatives still controlled the government, but they were willing to include some Liberals in the Cabinet. This move insured that the Liberals would not have the grievance that caused so much violence in the past.

Nobody in Colombia was more committed to recovery and reform than Rafael Reyes Prieto, the president from 1904 to 1909. He introduced the policy of making the Liberals partners; his mottos were "peace, harmony and work" and "less politics and more administration." However, like the reformers of the nineteenth century, he had to rule like a dictator to get things done, changing the constitution more than once. This included strengthening executive power, and when Congress could not work because it lacked a quorum, Reyes dissolved it and set up a General Constitutional Assembly, with members who were appointed instead of elected, to approve his decrees and pass constitutional amendments.(21)

Despite his dictatorial methods, the policies of Reyes had much support. New railroads and highways were built, the monetary system was stabilized by going back to the gold standard, and export agriculture was encouraged. A protectionist trade policy helped industry to grow; this was the first time the Colombian government had intervened in the country's economic activity. In 1907 Colombia and Brazil signed the Vásquez Cobo-Martins Treaty (also called the Treaty of Bogotá), which established a defined border between the two countries; by agreeing to this, Colombia gave up its claim to the part of the Amazon jungle where the Uaupés River flows into the Rio Negro, and also gave up its claim to the town of Tabatingas.

Reyes believed that the best way to insure economic growth would be to normalize relations with the United States, because the United States was a great customer of Colombian coffee, and a treaty would attract North American investors. He introduced a treaty to that effect, which would recognize the loss of Panama in return for an indemnity. Unfortunately, he misread the mood of the people, who were still furious at what the US had done in Panama. In June 1909, elections were held to re-establish Congress, and the coalition of moderate Liberals and moderate Conservatives that won refused to ratify the treaty. Seeing that the majority was against him, Reyes resigned one month later and left the country. A treaty recognizing Panama's independence wasn't accepted until after tempers had cooled, in 1921.

The moderate coalition mentioned in the previous paragraph was called the Republican Union, and one of its founders, Carlos Eugenio Restrepo, was the next elected president (1910-14). He and his Conservative successors continued the formula of making the Liberals partners, and together they agreed to reforms that made Columbia look more like a western European country: weaken the power of the president, increase the power of Congress, more minority representation, direct election of the president, and the abolition of the death penalty. However, you could say the country was still an oligarchic republic, because voting rights were restricted to ten percent of the male population.

You probably didn't find the aforementioned political reforms very exciting, and during this time, economic and social developments were stormy by comparison. The rapid increase in coffee exports paid for diversification of the economy(22), and the growth of industry.(23) And Reyes was right about investors coming after the approval of a treaty with the United States; by 1929 investors had poured $400 million into Colombia, of which $280 million came from the US.

Peasants moved to the cities to take advantage of the new jobs, forming a working class for Colombia. They quickly learned to unionize, and the unions introduced European revolutionary ideas like socialism. Colombia's first major labor strikes occurred in 1918. Meanwhile, there was a shortage of agricultural workers, because so many had left the farms; those remaining petitioned for higher wages, and the shortage caused the government to start importing food in 1928. That was part of the reason for a really bad strike against the United Fruit Company in the same year, which the military ended by killing thousands of banana workers. A young lawyer, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán Ayala, criticized the rough handling of the strike, and because he was a great orator, that made him the chief spokesman for the working class.

As in most of the world, the "dance of the millions" ended with the onset of the Great Depression. The Conservative government couldn't cope with the problems the Depression brought, especially unemployment, and there was serious unrest from peasants and workers outraged over the United Fruit Company massacre. As you might expect, that led to the fall of the Conservatives, after forty-four years of rule. With the 1930 elections, the oligarchs united behind the Liberal candidate, Enrique Alfredo Olaya Herrera, to keep the followers of radical ideologies from taking over. Olaya was elected president, and the Liberal Party would be in charge for the rest of the Depression and World War II years.(24)

The Mexican Revolution, Phase 1: Conservatives vs. Liberals

The Mexican Revolution was the bloodiest conflict in Latin America since the War of the Triple Alliance nearly destroyed Paraguay. It lasted for a whole decade, and between one and two million were killed, meaning that almost one in eight Mexicans may have lost their lives by 1920. And it wasn't as clear-cut as the World Wars being fought in Europe, where one side had a different ideology from the other side. After the conservatives were pushed out, the liberals formed factions that fought among themselves in a kaleidoscope of shifting alliances. In each phase of the revolution, no quarter was given or expected. The end result was that a radical government took over, turned conservative to hold onto the gains it had made, and ran the country for the rest of the twentieth century.

|

|

| Francisco Madero. | Victoriano Huerta. |

|

|

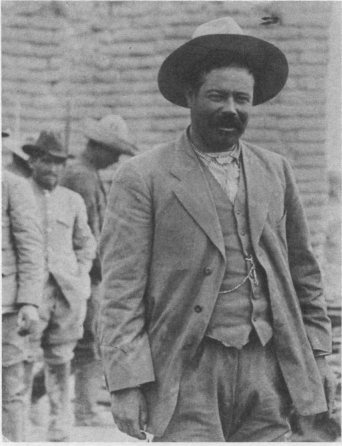

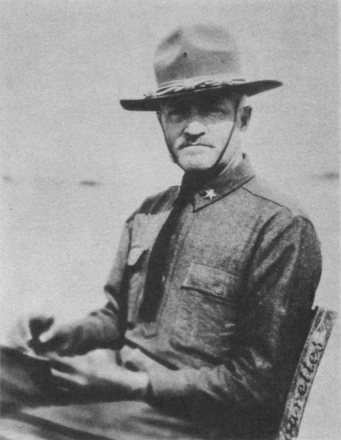

| Francisco "Pancho" Villa. | General John "Black Jack" Pershing. |

When we finished Chapter 4, Mexico was in the middle of the long reign of Porfirio Diaz (1876-1911). By ending the previous age of strife, and by making huge concessions to European and US-owned businesses, Diaz had prepared the way for rapid growth. Modern factories, telegraph and telephone lines, railroads and banks were introduced to Mexico. Oil was discovered just in time to take advantage of the world switching from coal to oil as its main source of power; petroleum exports rose from ten thousand barrels in 1901 to thirteen million in 1911.

But all this caused resentment among Mexicans who saw Diaz playing favorites with foreigners. Though Diaz was a Mestizo, meaning he had mixed ancestry, he believed the country would do best if white people were in charge of everything; hence the business concessions. Some Mexicans wrote that the foreign businesses were behaving like the conquerors of a defeated nation. To them the biggest offenders were the Gringos from north of the border. By 1910, there were 75,000 US citizens living in Mexico (most of them would leave after the Revolution began), and one fourth of Mexico's land was controlled by them. William Randolph Hearst (see the first section on Cuba in this chapter) once said about that, "I really don't see what it is to prevent us from owning all of Mexico, and running it to suit ourselves." Mexicans also noted that foreigners like Mexico's small Chinese community were getting ahead, while most Mexicans stayed poor. Thus, at this time, Mexicans coined the saying, "Mexico, mother of foreigners and stepmother of Mexicans."

Diaz stuck around too long. His iron-handed rule was no longer needed, but he did not set up the government so somebody else could run it. The stability he brought came at a cost--political opposition and a free press were not allowed. Young intellectuals protested against the dictatorship; Indian peasants, who were treated like slaves, began to attack their landlords; crop failures between 1907 and 1910 caused a steep rise in the price of corn and beans. And it just so happened that 1910 was also the centennial of the grito de Dolores, the event that started Mexico's war for independence.

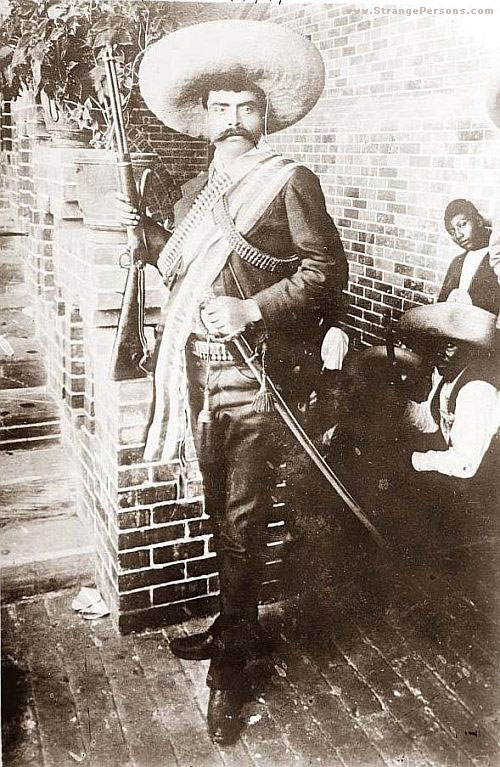

At first Diaz said he would retire and allow free elections in 1910, but when election time drew close, the eighty-year-old strongman changed his mind and ran once more. Francisco Madero, a wealthy land and business owner from the state of Coahuila, announced he would run against Diaz. When it looked like Madero would win, Diaz had him thrown in jail until election day, and then claimed he had won by yet another landslide. Once Madero was released, he fled to Texas, proclaimed himself the rightful president, and urged Mexicans to join him. Madero's first revolt got nowhere, forcing him to go to Texas again, but the second time he went to Chihuahua and joined forces with two local revolutionary leaders, a mule driver named Pascual Orozco and a former bandit named Francisco "Pancho" Villa.(25) Together they captured the border city of Ciudad Juarez in May 1911, giving them a solid base of support. More revolts sprang up in other parts of the country; the most serious revolt, in the southern state of Morelos, was led by Emiliano Zapata and featured the local Indians trying to take back their ancestral lands, under the cry "¡Tierra y libertad!" (Land and freedom!).

Emiliano Zapata.

By now even the United States had grown tired of Porfirio Diaz, and switched its support to Madero. Because of that, mobs in the streets, and the danger that Zapata might march on Mexico City, Diaz got the message; he resigned and went into exile, dying in Paris in 1915. That was the end of Diaz, but only the beginning of this story. Because Diaz had kept the lid on dissent for so long, and Mexican liberals finally got their chance to make the political and social changes they wanted, to match the economic changes caused by industrialization, Mexico would experience Latin America's first truly social revolution.

New elections were held in October 1911, and this time they really were clean. Madero won big, but he wasn't tough enough to make the other factions accept his victory. The liberals were now divided between moderates like Madero, who thought reform should come from the ballot box, and radicals like Zapata, who preferred, quick, violent solutions. Madero sent federal troops to disband Zapata's forces, failed to dislodge them, and the Zapatista movement was born. On top of that, factory workers organized themselves into unions and called for strikes, and Madero alienated the United States by introducing a tax on oil production.

There was one faction that could maintain order in this chaotic situation--the military. When General Victoriano Huerta realized this, he launched a coup that overthrew Madero (1913); a few days later, Madero and his vice president were assassinated while in custody. Huerta then declared himself provisional president and formed a coalition that included former Diaz supporters (they thought they had found a worthy heir to Diaz). US businessmen, who had $1.5 billion invested in Mexico, also welcomed Huerta, thinking the new regime meant the trouble was over. But Huerta was a reactionary, so his rise to power caused the revolutionaries to (temporaily) unite against him. The anti-Huerta coalition, called the Constitutionalists, was led by Venustiano Carranza (a former Madero supporter) in Coahuila, Pancho Villa in Chihuahua, and Zapata in the south. In the northwest, Colonel Álvaro Obregón held Sonora for Carranza. The US government did not like Huerta either, because this was the age when aggressive reformers ("Progressives") dominated Washington, and chief among them was the new president, Woodrow Wilson. Also concerned that Huerta would grant privileges to British and German investors, hurting US business, Wilson refused to recognize the Huerta regime.

The current poor relations between Mexico and the United States led to the "Tampico Affair." Mexico's budding oil industry had attracted quite a few Gringos to the ports of Tampico and Veracruz, and US naval ships followed to ensure their safety. In early 1914, nine American sailors at Tampico entered an off-limits area to load an oil cargo, and were arrested. The whole thing was a misunderstanding, caused because the Americans and Mexicans did not speak each other's languages, and the sailors were quickly released, but the captain of their ship demanded a formal apology and a twenty-one gun salute to the US flag. Huerta sent a letter of apology to President Wilson, but asking a foreigner for a twenty-one gun salute was clearly over the top, so he did not give that. Wilson responded by sending the US navy into the Gulf, and when he heard that a German ship was headed for Veracruz with arms for the Huerta regime, he forgot about Tampico and ordered the fleet to take Veracruz instead. Casualties were light; most of those killed were Mexican cadets, who bravely chose to fight back from the naval academy instead of evacuate the city with Huerta's troops. Still, all Mexicans were enraged--in the past, foreign invasions of Mexico had always begun with a landing in the Veracruz area. Even Venustiano Carranza, the most pro-American faction leader, demanded that the Yankees leave immediately. To defuse the crisis, Wilson accepted an offer from Argentina, Brazil and Chile (the "ABC coalition") to mediate the dispute; talks began at Niagara Falls, Canada in May 1914, and the last US troops withdrew from Veracruz the following November.

By this time, Huerta was history, which was what Wilson had really wanted. In the south, the Zapatistas took back Morelos, which they had lost to Huerta in 1913, captured the states of Guerrero and Puebla, and it looked like Mexico City would be their next target. In the north, the other factions advanced rapidly towards Mexico City. Obregón, who turned out to be a military genius, advanced down the Pacific coast all the way to Guadalajara; Carranza took Monterey and Tampico in the east, and was about to take Veracruz when the Yankees got there first.(26) Pancho Villa's advance mattered the most; he overran Durango, defeated a federal army at the battle of Zacatecas (June 23, 1914), and captured that silver-rich town.(27) This was the biggest battle of the Revolution, leaving 7,000 soldiers dead and 5,000 wounded. The loss of Zacatecas convinced Huerta that he could not win, so he resigned the presidency and went into exile on July 15.(28) Behind him, Obregón's troops entered Mexico City (August 15), and Carranza proclaimed himself president six days later.

This is the end of Part I. Click here to go to Part II.

FOOTNOTES

1. Today's Latin American heads of state are better behaved because they are concerned about their image on the world scene, so technically there are no banana republics in the region anymore. However, several African countries are in bad enough shape to fit the description; so are Myanmar and Laos in Southeast Asia. The Banana Republic clothing company got its name from the original owners, who gave their stores an exotic theme.

2. It wasn't true, all those countries saw trouble in the late twentieth century. We will look at their woes in the next chapter.

3. The main exception to the rule was Cuba. It was already in the US orbit completely when World War I began, and because Europe no longer produced sugar to compete with Cuban sugar, the war years were good years for that island. The same thing happened again in World War II. Go to the Cuban sections of this chapter for details.