| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Latin America and the Caribbean

Chapter 6: Contemporary Latin America, Part V

1959 to 2014

This chapter is divided into seven parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| One More Overview | |

| Cuba: The Revolution Continues | |

| Venezuela's Democratic Interlude | |

| Brazil: The Death of the Middle Republic | |

| Weak Radicals and the Argentine Revolution | |

| Colombia: The National Front |

Part II

| Che! | |

| Democracy Breaks Down in Chile | |

| Peru: The Revolution from Above | |

| Mexico: The PRI Corporate State | |

| Meet the Duvaliers | |

| Honduras Goes From Military to Civilian Rule | |

| Ecuador: From Yellow Gold to Black Gold | |

| Tupamaros and Tyrants | |

| The Somoza Dynasty, Act Two |

Part III

| Paraguay: The Stronato | |

| Brazil: The Military Republic | |

| Bolivia: The Banzerato | |

| Red Star In the Caribbean | |

| The Perón Sequel and the "Dirty War" | |

| Panama: The Canal Becomes Truly Panamanian | |

| The Dominican Republic: The Balaguer Era | |

| The Guianas/Guyanas: South America’s Neglected Corner | |

Part IV

| The Salvadoran Civil War | |

| Belize: A Nation Under Construction | |

| The Guatemalan Civil War | |

| The Southernmost War | |

| Among the Islands | |

| Colombia: Land of Drug Lords and Guerrillas | |

| The Pinochet Dictatorship | |

| Peru: The Disastrous 1980s |

Part V

Part VI

| Brazil: The New Republic | |

| Cuba's "Special Period" | |

| Chileans Put Their Past Behind Them | |

| Colombia’s Fifty-Year War | |

| Uruguay Veers from the Right to the Left | |

| Daniel Ortega Returns | |

| Ecuador: Dollarization and a Lurch to the Left | |

| The Chavez Administration, Both Comedy and Tragedy |

Part VII

| Argentina: The New Millennium Crisis, and the Kirchner Partnership | |

| Guatemala Since the Peace Accords | |

| Can Paraguay Kick the Dictator Habit? | |

| Honduras: The Zelaya Affair | |

| Peru in the Twenty-First Century | |

| Bolivia: The Evo Morales Era | |

| The Mexican Drug War | |

| Puerto Rico: The Future 51st State? | |

| Conclusion |

The Switzerland of Central America

We only need one paragraph and two footnotes to cover Costa Rica in the period covered by this chapter. In effect, Costa Rican history ended in the 1950s; the social experiment started by José Figueres Ferrer (see Chapter 5) survived all its challenges, working successfully to this day.(115) Since the second term of Figueres ended in 1958, elections have proceeded on schedule every four years, with no president being re-elected to two consecutive terms. Figueres himself served once more, from 1970 to 1974. Most presidents have come from either the party of Figueres, the National Liberation Party, or from the center-right Social Christian Unity Party (a Christian Democratic party, founded in 1983). After Figueres, the most important president was Óscar Arias Sánchez (1986-90 and 2006-10), who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1987 for actively working to end the civil wars that afflicted Central America in the 1980s; for his second term, he mediated in the 2009 Honduran constitutional crisis.(116) Other interesting heads of state include Rafael Ángel Calderón Fournier (1990-94), the son of 1940s President Rafael Ángel Calderón Guardia; José Figueres Olsen (1994-98), the son of José Figueres Ferrer; and Laura Chinchilla (2010-14), the country’s first woman president. A new leftist party, the Citizens’ Action Party, entered the game after the twenty-first century began, and its candidate for 2014, Luis Guillermo Solís, became the first president from that party, because the National Liberation Party candidate dropped out of the race.

Nicaragua: The Contra War

The victors of Nicaragua’s civil war inherited a country in a mess. An estimated 50,000 had been killed, 150,000 were made refugees, and 600,000 were left homeless. The United Nations estimated that the war had done $480 million in damages. Other major problems included poverty, illiteracy, malnutrition, disease, and pesticide contamination. Lake Managua was considered dead from pollution, and widespread cutting down of the eastern forests had led to soil erosion. At this point most Nicaraguans accepted Sandinista rule, figuring that they just had to be better than the Somoza regime.

To get things done, the constitution was suspended, and congress was dissolved. The National Guard was replaced by the Sandinista People's Army, led by Humberto Ortega Saavedra, Daniel Ortega’s brother. The junta successfully launched health-care reforms and a much praised Literacy Crusade, which raised the literacy rate from less than 50% to 87% in just two years. Other organizations were formed to represent labor, peasants, and women.

Unfortunately the junta was rigged, in the Sandinistas’ favor. Two non-Sandinista members, Violeta Chamorro and Alfonso Robelo, resigned within a year, and the other two members were willing to let Daniel Ortega run the show. Once they controlled the government completely, the Sandinistas nationalized more than 300 businesses and passed the Agrarian Reform Law, to nationalize large tracts of land.(117)

Relations between the Sandinistas and the United States were never very good, because the Americans had backed the Somoza regime until the last months of the recently ended civil war. Thus, it was natural for them to look first to enemies of the US for assistance. Soon the Americans grew alarmed at the number of Cuban and Soviet advisors coming into Nicaragua. Soviet military aid allowed Nicaragua to build an army of 75,000, larger than the other armies of Central America put together; did it really need that many men to defend its borders? And there were allegations that the Sandinistas were providing arms to leftists in El Salvador. Jimmy Carter allowed aid to keep going to Nicaragua, so it would not become a total Soviet satellite like Cuba, but when Ronald Reagan succeeded him in January 1981, one of his first acts was to stop that aid. Next, Washington began aiding former National Guardsmen, so they could launch a new civil war against the Sandinistas. For these rebels, henceforth called the Contras, the Reagan administration also built bases in Honduras and Costa Rica, and spent millions on training and arms for them.(118)

To show the Sandinistas still had the hearts of the people, free elections were held in 1984. Daniel Ortega won with 67 percent of the vote, and most foreign observers (though not conservative Nicaraguan parties or the Reagan administration) certified that the election had been fair. But after receiving this mandate, Ortega became less tolerant of opposition, not more tolerant. He declared a state of emergency, shut down the press and instituted a military draft. Washington responded by giving Nicaragua the same treatment it gave to Cuba -- a full economic blockade, which included food and medicine.

For the rest of the 1980s, the Nicaraguan economy deteriorated, partially because of the war, partially because of the US embargo -- and partially because the Sandinistas diverted government spending to the military, until 50 percent of the budget was going towards defense. Congress had ordered an end to support for the Contras in 1982, but by doing it covertly, the Reagan administration was able to keep aid coming for five more years (the famous Iran-Contra scandal). Once the aid was cut off, the war ground down to a halt. By this time, the Soviet Union was coming undone (its disintegration was only a few years away), so aid to the Sandinistas was cut off, too. More than 60,000 soldiers -- roughly half from each side -- and 50,000 civilians were dead, and neither the Contras nor the Sandinistas had to resources to fight until they achieved victory.

This stalemate made the two sides willing to negotiate. In 1987 Costa Rican President Óscar Arias offered a peaceful solution, asking five Central American presidents to sign a treaty that would end the wars in El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua, and end all military aid from the US and USSR. Over the next year they all signed, Arias won the Nobel Peace prize for introducing the treaty, and though it took until 1993 for the fighting to end, peace did come to Central America. Ortega ended censorship of the press and agreed to allow free elections in 1990.

For those elections, fourteen parties formed the National Opposition Union (UNO); the only thing they had in common was that all wanted to vote the Sandinistas out of office. Aside from that, they could not put together a platform that would attract the voters, while the Sandinista campaign played the patriot card, portraying UNO members as pro-Somoza, tools of US foreign policy, and enemies of the Nicaraguan revolution. The UNO presidential candidate, Violeta Chamorro, promised to concentrate her attentions on peace and repairing the economy. Because the UNO looked weak, ABC News predicted a sixteen-point Sandinista victory, but instead, on Election Day (February 25, 1990), the FSLN lost by fourteen points; obviously the Nicaraguan people were exhausted by war and poverty. Equally surprising, Ortega stepped down, instead of holding on bitterly like so many other Communists have done.(119) During his last two months in office, Ortega and his followers in the National Assembly authorized the transfer of some lovely pieces of real estate -- houses, farms, businesses, and islands -- to outgoing Sandinistas, either for free or at deep discounts below the market value price. When Chamorro allowed them to keep these going-away presents, Nicaraguans called the giveaway La Piñata, and it immediately became the first scandal of the new administration. Finally, the US ended the embargo, since it had served its purpose.

Ecuador After the Juntas

Most Latin American countries have needed to undergo a social revolution, before they can successfully manage a democracy. With Ecuador, it happened in the 1970s. We noted previously that the juntas which ruled from 1972 to 1979 carried out the reforms that elected leaders would not or could not implement, and they ended four decades of on-and-off rule by an aging, demagogic president, José María Velasco Ibarra. Since 1979 there has not been any more military rule, but there has been plenty of political instability to keep things interesting; only after the twenty-first century began did it look like Ecuador got a handle on how a representative government works.

After the military got out of the way, land and tax reform came to a halt. However, the economy had grown impressively under the junta, thanks to the boom in oil wealth, and the new president, Jaime Roldós, took full advantage of that. Whereas the government did not manage the past "booms" in cacao and bananas, it had total control over how the oil and the money made from it would be used. And because Quito was the closest major city to the oilfields, it quickly grew from a sleepy community in the highlands to a modern urban center that could compete with Guayaquil in commerce. Roldós launched a five-year plan that called for investing $800 million in rural development, to bring 3 million acres of new land under cultivation and distribute almost 2 million acres to landless peasants. In terms of foreign policy, Roldós, like his civilian predecessors, sought greater independence from the United States, mainly by keeping friendly relations with socialist and communist countries, especially Cuba.

But Roldós did not get to see the results of his ambitious reform and development programs, because he was killed in a plane crash, along with his wife and the defense minister, on May 24, 1981. This led to conspiracy theories suggesting the crash was not an accident. Some Ecuadoreans thought the Peruvian government was responsible, because the crash happened near the Ecuador-Peru border, and the ongoing border dispute between the two countries had led to a bloody clash four months earlier. Others blamed the United States when Panamanian President Omar Torrijos died in a similar plane crash, later in the same year.

Whether the crash was an incident or an accident, Ecuador needed a caretaker president until the next election, and the vice president, Osvaldo Hurtado, stepped in to fill that role. He inherited lots of bad news, starting with a worldwide oil glut, which reduced prices and demand for oil and now sent Ecuador into a recession.(120) Worse than that, Ecuador had done large amounts of borrowing in the 1970s and early ‘80s, raising the foreign debt to US $7 billion by 1983. In effect, Ecuador spent its oil money before receiving it; the Ecuadorean government was confident that income from the oil wells would pay off what they were borrowing, and now the income was less than expected. Finally there was both a drought and severe flooding, caused by the El Niño effect on Pacific Ocean currents (see Chapter 1).

Hurtado dealt with the crisis by implementing austerity measures that were extremely unpopular, but succeeded in gaining help from the International Monetary Fund and the foreign business community in general. In return for a postponement on debt payments (just paying the interest on the foreign debt was costing more than 30 percent of Ecuador’s export earnings), Hurtado eliminated government subsidies for food, and devalued the country’s monetary unit, the Sucre; these measures caused high inflation, thus hurting the poor. The response of the working class was to launch four general strikes, but they backed down when it looked like the strikes would provoke a coup d'état.

For the 1984 elections the voters elected a conservative Guayaquil businessman, León Esteban Febres-Cordero Ribadeneyra, as the next president. Febres-Cordero chose to imitate the policies of the United States, since the US economy was growing strongly under the Reagan administration. This meant free-market reforms (what Americans called "Reaganomics"), a strong stand against drug production/distribution and terrorism, and good relations with the United States. Well, imitation has been called the most sincere form of flattery, and sure enough, when Febres-Cordero visited Washington in January 1986, Ronald Reagan praised him as "an articulate champion of free enterprise."

Unfortunately, oil prices underwent another slump in 1986, instead of recovering while Febres-Cordero was president, and a terrible earthquake in 1987 destroyed 25 miles of oil pipeline; not only did this hurt the economy by interrupting oil exports, but it also caused a disastrous oil spill. Furthermore, while Febres-Cordero’s activities may have been popular abroad, Ecuadoreans definitely did not like them. His opponents accused him of allowing an increase in human rights violations, including torture and extrajudicial killings.(121) And Febres-Cordero had trouble getting along with the other branches of the government; this showed in January 1987, when members of the air force kidnapped the president and held him for eleven hours, demanding the release of a general who had been imprisoned for leading two unsuccessful uprisings against the minister of defense.(122)

Because the voters felt that the policies of Febres-Cordero were helping the nation but not themselves, for the 1988 presidential election, two liberals, Rodrigo Borja Cevallos and Abdalá Bucaram, came in first and second place. Borja won, and while he claimed to be facing "the worst economic crisis" in Ecuador’s history, he made human rights protection his priority, and carried out limited reforms to open the country to more foreign trade. Borja’s administration also reached an agreement with "¡Alfaro Vive, Carajo!,"(123) a small leftist group that had conducted some raids and kidnappings in the 1980s; under the agreement the group renounced terrorism and became another political party. However, he could not get a handle on the continuing economic problems, and soon he faced opposition from both the right and his former supporters on the left; there was also a major Indian demonstration in 1990 (the "Inti Raymi Uprising") and a general strike in 1991.

The leftward political shift of 1988 was balanced with a rightward shift in 1992; this time the voters picked Sixto Durán Ballén, a former mayor of Quito who had run for president twice before (in 1979 and 1988). He campaigned on a program of state reconstruction and privatization, which turned out to mean laying off 120,000 of the government’s 400,000 employees and privatizing 160 state-run companies. With this came the bad-tasting medicine of another devaluation of the Sucre, and increases in energy prices (gasoline, electricity and natural gas) all around. Of course this was no popular than before, and led to the usual strikes. Then in 1995 the vice president, Alberto Dahik, was impeached on charges of making himself rich with public funds, and he fled the country. Dahik was considered the architect of the economic policies, and his fall from grace didn’t help the president; during his term in office, Durán’s popularity fell from 70 percent to less than 10 percent.

In foreign affairs Durán did better than average, though. He secured Ecuador’s membership in the World Trade Organization, a move which made the country’s exports more competitive. More important, from the Ecuadorean point of view, was a brief war with Peru in early 1995, called the Cenepa War. The issue here was the same one that had caused the 1941 war and the 1981 clash -- a boundary dispute. This should have been settled by the 1942 Rio Protocol, but part of the border ran through an unpopulated, barely explored area for forty-nine miles, following the ridge of the nearest mountain range, the Cordillera del Cóndor. And not only was the region remote; the jungle here was so thick that surveyors never went in to demarcate exactly where the border was. Ecuador thought the border ran a little bit east of where the Peruvians put it, which gave Ecuador access to the headwaters of the Cenepa River. So the two sides went ahead and built outposts where they thought the border belonged.

Clashes were avoided until the end of 1994, when Peru discovered Ecuadorean outposts that it considered too far east, and ordered their removal; Ecuador responded by moving troops and aircraft into the Cenepa valley. Peru mobilized as well, but the troops and aircraft they brought in turned out to be insufficient to expel the Ecuadoreans. In four weeks of fighting, no territory changed hands, but Peru suffered 480 killed and wounded, while Ecuador suffered just 127 casualties. Thus, the Ecuadorean armed forces felt vindicated, because in the previous conflicts the Peruvians did better than they did. Even so, both sides claimed victory when the four nations that acted as guarantors of the Rio Protocol (Argentina, Brazil, Chile and the US) persuaded them to sign a cease-fire accord. By May Ecuador and Peru had removed their troops from the Cenepa valley, and negotiations began. The negotiations eventually led to the signing of a peace treaty in October 1998 (the Brasilia Presidential Act), and a formal demarcation of the Ecuador-Peru border in May 1999. One of the longest territorial disputes in the western hemisphere had at last been settled.

Abdalá Jaime Bucaram Ortiz is proof that in a democracy, the voters don’t always elect the best person for the job. The mayor of Guayaquil, he ran for president in 1988 and 1992, before suddenly winning on his third try, in 1996. I say "suddenly" because it was never clear how he did it. For one thing, he sported a toothbrush mustache that was sure to remind everyone of Adolf Hitler. For another, he called himself El Loco ("the Madman"), and lived up to that nickname.

The thing about Abdalá Bucaram was that he saw politics as just a day job. What he really wanted was to become a pop star, sort of a latter-day Elvis Presley, as he showed in this rendition of "Jailhouse Rock":

Personally, I think his Haitian counterpart, Michel Martelly, has more talent. For one thing, Martelly became a star before he became president.

While he was president, Bucaram made his own demo CD, "A Madman in Love," and gave away copies of it to other heads of state at the 1996 Ibero-American Summit in Chile. And if that doesn’t sound goofy enough, he invited Lorena Bobbitt, the woman who became famous for mutilating her husband, to lunch in Quito, and gave her one of the CDs as well.

Fortunately, El Loco only lasted in office for six months; he did not have time to start a war or commit atrocities, the way other madmen with power have done. What he managed to do was put Ecuador in the poorhouse, when he wasn’t busy entertaining. During the election campaign Bucaram had promised cheap public housing, lower food prices and free medicine, and with Ecuador’s previous economic crises, you know the country couldn’t afford that. Moreover, the political allies Bucaram filled the cabinet with only made matters worse. Before long, people were accusing Bucaram of embezzling millions.(124)

By February 1997 the country was fed up with Bucaram, and the people began to protest. Congress impeached and deposed him on grounds of "mental incapacity"; his vice president, Rosalía Arteaga, became Ecuador’s first female president for only two days, before Congress put its leader, Fabián Alarcón, in the top spot, and (illegally) requested that the army back Alarcón. In May the people of Ecuador called for a National Assembly to reform the Constitution and the government, so Alarcón held the presidency until a new constitution was passed and new elections could be held, both in 1998. As for Bucaram, he avoided standing trial for corruption by seeking asylum in Panama. He came back in 2005, after the corruption charges were dropped, stayed in Guayaquil for two and half weeks, and then took off for Panama again when the charges against him were reinstated.

Chasing Noriega

Omar Torrijos did not live to see the Panama Canal handed over; he was killed in an airplane crash on July 31, 1981. His place was taken by the chief of staff, Colonel Florencio Florez Aguilar. Florez allowed the president to be more than just a figurehead, but he was not as popular as Torrijos, either with the junta or with the people. It also did not help that the current president was anti-American, and he used his strengthened position to accuse the United States of hundreds of technical violations in the implementation of the Canal treaties. In March 1982, Florez completed twenty-six years of military service, and because he was now at retirement age, his associates forced him to step down. The next military strongman to take charge, General Rubén Darío Paredes, was widely seen as the person Torrijos would have wanted as his successor. Because of growing unrest and the inability of the political parties to work together, Paredes sacked the president and most of the cabinet the following July. In December 1982, Manuel Noriega (see the previous section on Panama) became chief of staff of the National Guard, making him the number two man under Paredes.

Torrijos had introduced a new constitution in 1972, and in 1983 some amendments were added to it which established rules on how the National Guard could act in politics. One amendment banned participation in elections by active Guard members, so Paredes resigned from the Guard that year in order to run for president in the next election. However, this also made the Guard’s commander in chief, Manuel Noriega, the most powerful man in the country. Noriega subsequently reorganized the National Guard, renaming it the Panama Defense Forces (FDP), forced out the current president, and made sure that Arnulfo Arias, who was running for president one more time, would not win. When the election took place in May 1984, there were numerous allegations of fraud as the votes were being counted, and at least one violent clash between supporters of the candidates. The final results announced put Paredes in third place, and Arias in a close second place, behind the candidate the FDP wanted, Nicolás Ardito Barletta Vallarino, a former vice president of the World Bank. The United States questioned whether this was how the voting really went, but because Ardito Barletta was an economist, not a military man, Washington decided that his victory was a step in the right direction.

Panama needed an economist running the show because it had a debt of $3.7 billion, the highest per capita debt of any country at this time. The International Monetary Fund was willing to refinance the debt if Panama tightened its belt and controlled spending, but the tax increase and the budget cuts Ardito Barletta announced to achieve this caused so many protests and strikes that he had to cancel some of them ten days later. In August 1985 Noriega declared the country was "totally anarchic and out of control," accused Ardito Barletta of running an incompetent government, and forced him to resign. The vice president, Eric Arturo Delvalle, took Ardito Barletta’s place.

Afterwards, some suggested that Noriega pushed Ardito Barletta out because the president intended to investigate the murder of Dr. Hugo Spadafora Franco, a former guerrilla fighter and a well-known critic of the Panamanian military. In the summer of 1985, Spadafora announced he had evidence showing Noriega involved in the sale of narcotics and illegal arms. Soon after that, his headless corpse was found in a mail bag, a few miles across the border in Costa Rica. Even worse, there were signs on Spadafora’s body that he had been tortured, before his killers sawed his head off.

If Noriega was trying to cover up dirty deeds, it only worked for the short run. He had cooperated with the United States in supporting the Contra rebels in Nicaragua (the "Iran-Contra" affair), but the Reagan administration was waging a "war on drugs" as well as a Cold War against communism. Noriega became an embarrassment to the United States when more evidence emerged of him working with the Colombian drug cartels, murdering opponents and rigging elections. When President Eric Arturo Devalle tried to dismiss Noriega in February 1988, the general had him deposed, the way he had removed Ardito Barletta. The US responded by indicting Noriega on charges of drug trafficking, imposing economic sanctions on Panama, ending a preferential trade agreement, freezing Panamanian assets in US banks and refusing to pay canal fees. New elections were held in May 1989, which offered Guillermo Endara as the heir of Arnulfo Arias (Arias had died the year before). Election observers, which included former US president Jimmy Carter, reported that Endara beat Noriega’s candidate by a 3-1 margin, so Noriega just declared the election invalid. Then Endara and his two vice presidential candidates, Guillermo Ford and Ricardo Arias Calderón, were beaten up, and the attack was filmed on a TV camera and broadcast abroad. That, and two failed coup attempts in 1988 and 1989, caused the Noriega regime to become more repressive.

In December 1989, Noriega dispensed with having front men in the presidency, and had the legislature declare him president. The first thing he did after that was give a speech where he banged a sword on a podium and declared war on the United States. What a foolish thing to do! Not only was the United States near the peak of its strength as a superpower, but as we noted, the US was more likely to intervene with force in the 1980s than in the decades before and afterwards. Five days later (December 20, 1989), the United States attacked Panama City with aircraft, tanks, and 26,000 troops. The purpose of the invasion was to get Noriega and install Guillermo Endara as the rightful president; officially this was called "Operation Just Cause," while the mainstream media, hostile to the Reagan and Bush administrations, nicknamed it "Operation Just ‘cuz." Estimates of the number of Panamanians killed range from 500 to 7,000, depending on who you believe.

Swearing in Endara was the easy part; Noriega took refuge in the Vatican embassy for ten days, until persuaded to give himself up. While the Americans had the embassy surrounded, they resorted to a psychological tactic that any teenager will recognize; they wore down Noriega’s nerves by playing loud rock music outside.(125) When Noriega surrendered, he was promptly flown to Miami, FL, put on trial for multiple drug-related charges, and sentenced to a forty-year prison sentence. However, he was released in 2007 for good behavior, and then extradited to France and Panama to answer to more charges. He spent the rest of his life in the custody of those countries. The last time he made news was in 2014, by suing the maker of the video game "Call of Duty: Black Ops II", for using him as a character in the game without his permission -- as one of the villains, of course.

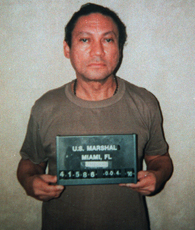

Manuel Noriega in American custody.

Endara had his work cut out for him, even with the United States restoring diplomatic relations and giving a generous aid package. Panama’s reputation and its economy was a mess; Panama City had been severely damaged by the invasion and by the wave of looting that followed. Endara did not lead effectively, his popularity dropped like a rock, and he was not elected again after his term ended in 1994.

There have been five presidents since 1994. The next president after Endara, Ernesto Pérez Balladares (1994-99), came from the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD), the party the military has supported, so he kept reminding the voters that he was the heir of Torrijos, but not the heir of Noriega. There would be no more military strongmen ruling in the name of a civilian government.

Balladares was succeeded by Mireya Moscoso (1999-2004), the widow of Arnulfo Arias and Panama’s first woman president. The transfer of the Panama Canal from US to Panamanian rule (briefly threatened while Noriega was making trouble), and the closing of the US military bases, occurred without a hitch on Moscoso’s watch. However, she also promised to create new jobs, and strengthen social programs for child development, education, crime reduction, and general welfare. Though she spent money like water on any program that looked like it would help the country (the most controversial expense was $10 million to bring the Miss Universe pageant to Panama), she failed to deliver on those promises, and most Panamanians remained poor.

After Moscoso the PRD got another turn in the hot seat, and Martin Torrijos, the son of Omar Torrijos, served as president (2004-09). The main event of his term was the introduction of a proposal to widen the Panama Canal, so it can handle larger ships; the voters passed it with a 78 percent "Yes" vote. A successful businessman, Ricardo Martinelli (2009-14), came after the younger Torrijos, and he was in turn followed by his vice president, Juan Carlos Varela.

Whatever else you can say about twenty-first-century Panama, it looks calmer than it was in the twentieth century. Now that Panama has the Canal and its sovereignty, not to mention a government that obeys the rule of law, for the first time in history, it has the chance to become a free, prosperous nation. We will see in this century if Panama becomes another Costa Rica.

Argentina’s New Democracy

On October 30, 1983, Argentinians went to the polls to elect a new government, and international observers declared the elections fair and honest. The voters elected Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín, the Radical Civic Union candidate, to a six-year term as president, giving him 52% of the vote.

Alfonsín promised to bring the perpetrators of the Dirty War to justice, and for that purpose he created the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons. Early in his term he did convict General Vadela and other high-ranking junta officials for kidnapping, torture and homicide, but when the government attempted to also try junior officers, there were too many of them,(126) and those officers launched uprisings in different parts of the country. In fact, Alfonsín couldn’t get along with the military very well, and they pressured him into passing two laws that stopped the investigations by the end of 1986: the Ley de la Obediencia Debida (Law of Due Obedience), which allowed lower-ranking officers to use the defense that they were following orders; and the Punto Final (Stopping Point), which granted amnesty to everyone charged with crimes committed before December 10, 1983, the day Alfonsín’s presidency began. There would be no more prosecutions until June 2005, when all the amnesty laws were overturned.(127)

When it came to foreign policy Alfonsín did better. We have already mentioned the 1984 "Treaty of Peace and Friendship" signed with Chile, and in 1985 he signed an agreement with Brazilian President José Sarney, promising close economic cooperation between South America’s two largest countries. This officially ended the old rivalry between Argentina and Brazil, and paved the way for the formation of Mercosur, South America’s Common Market, in the 1990s.

There also were promising signs in politics back home; large voter turnouts in the mid-term elections of 1985 and 1987, and a reduction of corruption among office holders, were signs that this time Argentina’s democracy would survive. However, the administration failed to solve the economic problems it inherited from its predecessors.(128) That, and the end of the prosecution of Dirty War criminals, which the population had overwhelmingly supported, undermined confidence in the Alfonsín government. For the 1989 presidential elections, the voters turned away from the Radical Civic Union and elected the Peronista candidate, Carlos Saúl Menem.(129) By this time Alfonsín was so unpopular that he decided to resign five months before his term was due to end, handing over power to the president-elect early.

Carlos Menem’s presidency lasted a full decade, from 1989 to 1999.(130) Whereas Alfonsín moved cautiously, Menem was a decisive leader, launching major changes in Argentina and its political system. An admirer of Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Augusto Pinochet, Menem pushed free-market reform: privatizing many of the industries Perón had nationalized (he came from Perón’s party, remember!), and pegging the peso to the US dollar, which gave a false sense of stability. When Congress was deadlocked on his proposed reforms, he would issue "emergency decrees" to enact them. In 1994 he reached an agreement with the opposition Radical Party, which allowed him to amend the constitution so he could run for re-election. Then in the next year he won a three-way race to secure a second term.

At the same time, however, government corruption ran wild. As part of the privatization program, Menem sold YPF (the national oil company), the national telephone company, the postal service and Aerolíneas Argentinas (the country’s largest airline) to foreign companies, and much of the profit could not be accounted for. He also attempted to run for a third term in 1999, until his action was ruled unconstitutional. The winner of that year’s election, a Radical named Fernando de la Rúa, got elected through an alliance of the Radical Civic Union and Frepaso, a new third party. Even so, it says something that all three major parties in the 1999 race supported continuing Menem’s free-market economic policies.

More scandals popped up after Menem left office. In 2001 he married Cecilia Bolocco, a former Miss Universe from Chile (this was controversial because she was 36 years old at the time, and he was 71). The same year saw him charged with illegally selling arms to Croatia and Ecuador, and he was placed under house arrest for five months, until the charges were dropped. The next day Menem announced he would run for president again in 2003, but dropped out after the first round when the polls showed him in second place, behind Santa Cruz Governor Néstor Kirchner. More charges have been leveled against Menem since then, but because of his status as a former senator, and because of his advancing age, the only sentence imposed on him was more time under house arrest.

Hugo’s Night in the Museum

Venezuela had two very prominent characters in the period covered by this chapter. We saw the first one already, Rómulo Betancourt, and now we have come to the other one, Hugo Chavez. The story of how Hugo became famous is a comedy of errors that is too good to ignore, so permit me to digress from the narrative to cover the beginning of his political career.

Hugo Rafael Chávez Frías was of mixed ancestry (European, African, and Native American rolled together), and born to a poor family; his father was a schoolteacher. Because there weren’t too many opportunities for a youngster like Hugo, he joined the army at the age of seventeen. There he found the break he needed to get ahead; he enrolled in and graduated from the Venezuelan Academy of Military Sciences, attended college afterwards but did not earn a degree, and over the course of the 1970s and 80s, rose quickly through the officers’ ranks. During this time, he also developed his own populist ideology, which he called "Bolivarianism," after his hero Simón Bolívar (see Chapter 3, footnote #62).

For a pet, Hugo Chavez had an Amazon parrot that was appropriately named Simón Bolívar. I found this interesting because I also have an Amazon parrot, albeit a different species. Unfortunately I couldn’t find out how he got the parrot to wear a little red beret, Mini-Me fashion. When Chavez died, somebody gave the parrot a Twitter account, at https://twitter.com/Chavezparrot.

In February 1992, Hugo Chavez was not famous; he was just a thirty-seven-year-old lieutenant colonel. Nevertheless, he had dreams of being much more important than that, and tried to gain power in Venezuela’s old-fashioned way -- through a coup. The coup plotters (which included some generals who outranked Chavez) had the support of five military units, just ten percent of the armed forces, but they figured that if they moved fast enough, the rest of the troops and those civilians dissatisfied with the government would join them. The plan was to have each rebel army unit seize control of a city, with Chavez commanding the unit that went for Caracas. In the capital, Chavez would make the military history museum his base of operations, capture President Carlos Andrés Pérez (and hopefully the generals who did not support the coup), broadcast the rebellion, and wait for the rest of Caracas to come around to him.

The first sign that things were not going as planned came when Chavez and his followers entered Caracas; the soldiers in the city already knew something was going on and shot at them. Nevertheless, they continued to the museum, where Chavez told the museum guards that they were reinforcements, and the guards actually believed it! The second problem was worse; the communication equipment Chavez was going to use for his broadcasts never arrived at the museum. The rebels did not even have access to telephones, so Chavez spent the night locked in the museum during his own coup, with no idea what was happening outside. You can think of it as a real-life version of the movie "Night at the Museum," except that we have no report of the exhibits coming to life and attacking the intruders.

Meanwhile outside of Caracas, the rebel units had captured the other cities assigned to them. But the president got away, and because they did not catch him, the coup was doomed to fail. Chavez only found out about this the next morning, when President Pérez announced in a speech that there had been an unsuccessful uprising the night before, and surrounded the museum with troops that had remained loyal. Ordered to give himself up, Chavez did so, after asking if he could announce his surrender on TV, so the other rebels would know about it and be persuaded to surrender peacefully, of course.

In his surrender speech, Chavez, still wearing his uniform and unashamed at losing, told the whole nation that he had only failed "por ahora" -- for now. He had to go to jail, but in the long run he came out the winner, for he had gotten his proverbial fifteen minutes of fame. An anti-corruption hero, who did not come from the white upper class, had been born.

You could also make the case that Pérez fared worse than Chavez after the coup. There was a second coup attempt later in the same year, led by junior air-force officers. This coup was bloodier, and featured an air battle over Caracas, with war planes flying between the skyscrapers. The presidential palace was bombed and partially destroyed, and more than 100 people were killed, compared with about 20 deaths in the first coup. Then in 1993, Pérez was accused of embezzling presidential campaign funds, impeached and removed from office. Two caretakers filled out the remainder of his term, and then the voters again re-elected somebody who had been there before -- Rafael Caldera. Caldera was now seventy-eight years old, but he won a second term for the same reason that Pérez did; the voters hoped his experience could bring back the good old days.

No such luck. Banco Latino, the second largest bank in the country, failed right at the beginning of the term, and the collapse of the bank caused a chain reaction that brought down ten more banks. Before returning to the presidential palace, Caldera promised he would not accept help from the IMF, the way Pérez had, but in 1994 he felt compelled to take it anyway; that meant devaluing Venezuela’s monetary unit, the Bolívar, by more than 70 percent, and increasing fuel prices by 800 percent. The economic crisis continued for all of Caldera’s second term. More people fell below the poverty line, drug trafficking and crime increased, and Colombian guerrillas spilled across the frontier into Venezuela’s western provinces.(131)

Caldera had also promised to pardon those involved in the first 1992 coup attempt, including Chavez, and he did so in 1994. No longer in the army (and no longer a nobody), Chavez organized a socialist political party with himself in charge of it, and the former coup plotters as the charter members; he named it the MVR, the Fifth Republic Movement.(132) By the time the 1998 elections rolled around, the per capita gross domestic product had fallen to the same level where it was in 1963, down a third from its 1978 peak. The establishment political parties were thoroughly discredited by their inability to solve the economic crisis, and those who saw Chavez on television in 1992 never forgot him, so the electorate turned to him in droves, electing him president with 56 percent of the vote -- a solid rejection of business-as-usual politics.

Democracy Comes to Bolivia (at Last)

Hernán Siles Zuazo was clearly the Bolivian people’s choice for president when democracy was restored in 1982, but good will was the only asset he had for rescuing the economy. Figuratively speaking, over the past eighteen years the military had sucked the country dry, and when they could no longer play that game, they threw away the skeleton. To pay the bills in a time of budget deficits, the government printed more and more money, with the same results as when Germany’s Weimar Republic tried it; inflation kicked in, shooting as high as 24,000 percent. In most of the country, barter replaced money; the price of tin fell 60 percent as well, ruining the mining industry. And to top it off, the government got on the bad side of the United States by establishing diplomatic relations with Cuba, and criticizing Washington’s Latin American policy.

By 1985, labor unrest had been added to the mix, and realizing that he was not likely to serve a whole term in office, Siles Zuazo cut it short by holding presidential and congressional elections one year early. In the presidential race, the top two candidates were former strongmen: Hugo Banzer Suárez and Víctor Paz Estenssoro. Because Paz Estenssoro’s record was less tainted, and a decade further in the past, he won a fourth term, and against the odds, he completed it (1985-89).

Unlike Siles Zuazo, the aged Paz Estenssoro had a plan for the economy. This was the age of Reaganomics, so by issuing Decree 21060, he enacted a package of free market policies like what had recently worked in the United States. For Bolivia it was very strong medicine, the kind that will either kill or cure the patient: government spending was slashed, price subsidies were ended, 30,000 miners employed by state-owned companies were laid off, and the peso was allowed to float against the US dollar. In addition there was a wage freeze, a tenfold increase in the price of gasoline, and labor unions were suppressed. While the high unemployment caused much suffering, in other ways the policy was a success. Most amazing was how it cut inflation; within a few weeks the rate was reduced to almost zero, and by the end of the 1980s it was still in the 6-15 percent range. When not busy with the economy, Paz Estenssoro built roads (with Japanese aid) in the jungles of northeastern Bolivia, to open it up to logging and to encourage settlement of an area that had previously been underpopulated and ignored, compared with the mountains.

Thanks to the military staying out of politics, human rights were no longer a problem in Bolivia, so the 1989 presidential election was somewhat dull, compared with previous ones. This time nobody won the first round, so the election was thrown to Congress again, and they picked the candidate who came in third place, Jaime Paz Zamora (Paz Estenssoro’s nephew and Siles Zuazo’s vice president). There was some concern among Bolivians that Paz Zamora would try something extreme, because he came from a Marxist background, but by now he had learned to stick with what worked, so he followed a center-left course and kept most of his uncle’s policies. Overall the assessment is that Paz Zamora muddled through; his term managed to be both uneventful and successful.

Paz Zamora was succeeded by a businessman named Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada y Sánchez de Bustamante, "Goni" for short. The son of a political refugee, he spent most of his childhood in the US city of Chicago, which also gave him the nickname of "El Gringo," because he spoke Spanish with an English accent. He first ran for president in 1989, as the MNR candidate, but he had to wait until his second try, in 1993, before winning. During his first term in office (1993-97), Sánchez de Lozada pursued both economic and social reform aggressively. On the social front, he amended the constitution to specify that Bolivia was a multi-ethnic state, thereby guaranteeing equal rights for the country’s large Indian population. However, his capitalización (capitalization) program was the most unusual (and most controversial) policy; this called for the privatization of public enterprises such as oil, telecomunication and electric companies, with 49 percent of the shares in those companies going to foreign investors, because the Bolivians themselves did not have money to invest. Opponents of the plan caused frequent labor disturbances from 1994 to 1996. Even the establishment of a Spanish-managed private pension plan, which gave US $248 to each Bolivian pensioner in the first year, could not restore the administration’s popularity.

Sánchez de Lozada was president during the first term of Bill Clinton’s presidency in the United States, and since Clinton was nicknamed the "Comeback Kid," it is appropriate that the next Bolivian president was Bolivia’s comeback kid -- the former dictator Hugo Banzer Suárez. In 1997 the voters rejected the MNR’s social engineering; 22.2% voted for Banzer, vs. 18.2% for the MNR candidate, and Congress ruled that was good enough. Thus, Banzer became the first caudillo in recent Latin American history to transition into a democracy, by winning a free election.

By now Banzer was seventy-one years old, so his administration was a kinder, gentler one, compared with his tyranny in the 1970s.(133) The main event of his term was the so-called "Cochabamba Water War" of January-April 2000. As part of the previously mentioned privatization program, the water utility of Cochabamba, Bolivia’s third largest city, was auctioned to a firm named Aguas del Tunari. This was a consortium made up of several companies, some of them Bolivian, but the controlling interest (55% of ownership) came from a British company, which was in turn controlled by Bechtel, the big US-based engineering corporation. Once it had the water works, the firm doubled water rates, to pay for the construction of a new dam. This led to demonstrations all over the province, the blockading of a highway for several weeks, and violence; one seventeen-year-old boy was killed and 175 injuries were reported. The government declared a state of siege and put Cochabamba under martial law. Protests continued for ninety days, until officials of Aguas del Tunari fled, after the government said it could not guarantee their safety; then the government announced they had abandoned the water works, and declared the contract void.(134)

A 1996 amendment to the constitution had increased the length of the president’s term in office from four to five years. Hugo Banzer did not get to enjoy the extra year, though, and you know he would have wanted to. Diagnosed with lung cancer, he had to resign in August 2001, right at the end of the fourth year in his term. He died the following May, and his vice president, Jorge Quiroga, finished out the term. With the 2002 election, "Goni" Sánchez de Lozada won a second term by securing 22.5% of the vote, narrowly edging out Evo Morales of the Movement for Socialism (20.9%), Manfred Reyes Villa of the New Republican Force (20.9%), and former president Paz Zamora (16.3%).

We saw how Sánchez de Lozada had a difficult time selling his economic policies during his first term, and they were even less popular in his second term. This involved steep tax hikes and the exploitation of natural gas by foreign companies, from a huge gas deposit recently discovered in southern Bolivia. The IMF approved the policies, but the population, encouraged by recent demonstrations (especially the Cochabamba Water War), launched another wave of protests and blockades, which are sometimes called the "Bolivian Gas War." The police had to lock down the city of La Paz for several days; again clashes with the police and army led to sixty deaths and more injuries. Unable to placate the masses, Sánchez de Lozada resigned and fled the country in October 2003. He settled in Miami, Florida, where he has lived in comfortable exile since then (after all, the United States had been his second home early in life). Bolivia has called for him to be extradited so he can stand trial for crimes he was accused of; so far Uncle Sam has refused to hand him over, because he hasn’t broken any US laws.

In keeping with the constitution, Sánchez de Lozada’s vice president, Carlos Diego Mesa Gisbert, automatically became the next president. Before he was picked to be a running mate in 2002, Mesa was a widely respected journalist and one of Bolivia’s foremost historians. He held on for twenty months, while enduring the same pressures that Sánchez de Lozada had faced. At first he said that the government needed to have more control over the foreign gas companies, and most Bolivians agreed with him. But then in March 2005, rising fuel prices stirred up the protests again, and this time they accused Mesa of giving US corporations what they wanted. As tens of thousands of poor Bolivians took to the streets, Mesa declared he was unable to govern the country, and offered his resignation to Congress. It was unanimously rejected, and Congress promised to give him more support. Nothing got better after that, though, and three months later he offered his resignation again; this time (June 2005) it was unanimously accepted. The chief justice of the Supreme Court, Eduardo Rodríguez Veltzé, was fourth in line of succession, and he filled the presidency for seven months, just long enough to call new elections and then step down when the winner, Evo Morales, was inaugurated (January 2006).

Haiti: Beggar of the Americas

In 1984 Ernest Preeg, the outgoing US ambassador to Haiti, wrote this in his final report on Haiti: "It can honestly be said that the Jean-Claude Duvalier presidency is the longest period of violence-free stability in the nation's history." That statement summarized the US attitude regarding Haiti before the 1985-86 revolution, and it correctly predicted that after the Duvalier regime, any government would be less stable, by comparison. A series of provisional governments followed until 1991, and a new constitution was ratified in 1987. Elections were originally scheduled for November 1987, but had to be cancelled after troops massacred between 30 and 300 voters on Election Day. When another election was held in 1988, most of the candidates from last time boycotted it, and voter turnout was only 4 percent. They might as well have not bothered; the winner, Leslie Manigat, was overthrown by the military three months later, General Henri Namphy took over again, and more massacres followed over the next two years. Meanwhile, the US Agency for International Development (USAID) encouraged US corporations to invest in Haiti, calling it a great place to find cheap labor. They came all right, and paid their workers so little that the presence of the factories hardly raised the standard of living (e.g., at a "model" clothing factory, the highest-paid workers only received $1.47 a day, and after paying for transportation, breakfast and lunch, they only got to take half that amount home).

The next presidential election, held in December 1990, pitted Marc Bazin, a World Bank official, against Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a charismatic Catholic priest influenced by Liberation Theology. Bazin was the favorite of business interests and the United States, but instead Aristide won with 67% of the vote. Though international observers called the election honest and fair, Aristide lasted in office for less than eight months, because the upper class was alarmed at his radical populist policies and the violent behavior of his supporters. In September 1991 the military threw him out in a coup and a mulatto general, Raoul Cédras, took charge.(135) Aristide escaped with the help of US, French and Venezuelan diplomats, and went into exile for the next three years. Back in Haiti, a crackdown on Aristide supporters killed between 3,000 and 5,000 people, and more Haitians tried to leave by boat, going either to surrounding Caribbean islands or to Florida. The U.S. Coast Guard rescued a total of 41,342 Haitians at sea in 1991 and 1992, more than the number of rescued boat people from all of the previous ten years.(136)

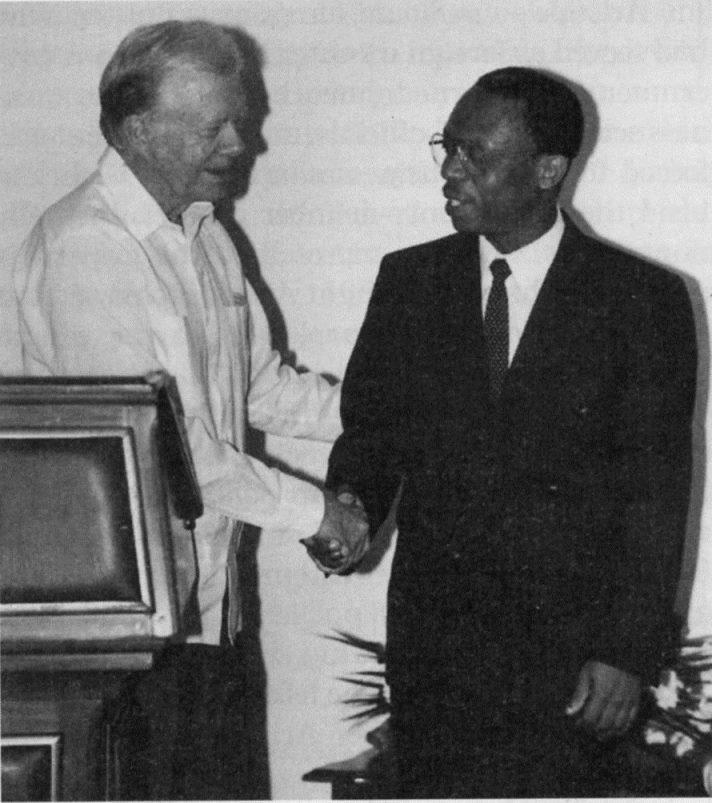

During the three years of military rule (1991-94), outside organizations like the OAS and the UN tried to restore an elected civilian government, and all initiatives failed. The military refused to get out of the way, though the economy was collapsing and the infrastructure was stagnating. When a human rights monitoring group was expelled from the country in July 1994, the UN passed United Nations Security Council Resolution 940, which authorized the use of all necessary means to remove Haiti's military leadership and put the previous constitutionally elected government back in power. The United States took the lead here, assembling a multinational force in case an invasion was necessary, and sending a negotiating team ahead of the troops, led by former president Jimmy Carter, to try peaceful persuasion once more. Because the multinational force was already on the way, General Cédras agreed to step aside; on September 19, 1994, the vanguard of a 21,000-member peacekeeping force landed in Haiti. The result was the opposite of what had happened with the previous coup; Cédras and two other leading generals went into exile with their families, while Aristide and his government returned on October 15. To prevent any more coups, Aristide disbanded the Haitian army, too.

Jimmy Carter with Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

The authorities held local and parliamentary elections in June 1995, which were won by a pro-Aristide coalition called the Lavalas Political Organization (OPL). Aristide’s term was due to end in February 1996, and because he was not allowed to serve two terms in a row, he let his first prime minister, René-Garcia Preval, run for president. Preval won 88 percent of the vote, and his inauguration was Haiti's first transition between two democratically elected presidents, in nearly two hundred years since independence.

After the election, Aristide broke with the OPL and formed a separate political party, the Lavalas Family (FL), while the OPL renamed itself the Struggling People’s Organization. This quickly led to gridlock between the former allies. The government refused to recognize the results of an election for several legislative seats in 1996, and when the prime minister resigned in June 1997, it took a year and a half to find a replacement that the legislature could accept. Consequently Preval was too busy to organize the elections that were supposed to take place in 1998. His answer to that was dismiss the entire Chamber of Deputies and all but nine members of the Senate in January 1999, because their terms had expired, and he and his prime minister ruled by decree for the rest of the year.

The next time legislative elections were held (May 2000), the FL won most of the seats. Charges of fraud went forth, because in eight Senate races the winner did not get a majority of the votes, and was seated without the special run-off election required when that happens. Foreign nations and the OAS threatened to cut off aid, and the opposition (now called the Democratic Convergence) boycotted the elections in November for the president and the remaining nine senators. Without the opposition parties, Aristide coasted back into office with more than 90% of the votes, and FL Party candidates swept all the Senate races. Because Aristide was still the Haitian leader the US and UN liked best, the last of the peacekeeping force that had been in Haiti since 1994 was withdrawn at the end of the Preval administration.

On February 6, 2001, one day before Aristide was sworn in, the Democratic Convergence named Gerard Gourgue, a lawyer and human rights activist, as the symbolic president of their "alternative government." The two sides tried negotiating an end to the political stalemate, with the OAS and other groups overseeing the talks, but in July 2001 they stopped meeting without reaching an agreement. A series of attacks by gunmen on the police stations and the National Palace in Port-au-Prince followed in late 2001; pro-government groups retaliated by attacking the homes of opposition leaders, killing one of them. In addition to the gridlock, growing violence and human rights abuses, senior members of the Aristide government were accused of drug trafficking, like the military regimes had done in the late 1980s and early 90s.

Anti-Aristide uprisings broke out in Port-au-Prince in January 2004. One month later, the rebels captured the cities of Gonaïves and Cap-Haïtien. A team of diplomats offered a proposal to let Aristide remain in office, but shorn of most of his powers, for the rest of his term; Aristide accepted the plan but the opposition rejected it. At the end of February, rebel forces marched on Port-au-Prince, and Aristide left Haiti; he and his wife flew on a US airplane to the Central African Republic. Afterwards Aristide insisted that he had been kidnapped, in a US-managed coup, while the US State Department reported that he had resigned from office. Neither side presented a convincing case, so we don’t know for sure who is telling the correct story.

Back in Haiti, the presidency was taken over by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Boniface Alexandre. He served the remainder of Aristide’s term (2004-2006), and because of deadly clashes between the police and Aristide supporters, he requested a second UN peacekeeping force, which was promptly dispatched. When elections were held in February 2006, René-Garcia Preval, now the most popular candidate among the poorest voters, won a second term. Though his administration was rocked by demonstrations against rising food prices, and more FL demonstrations, Preval remained in office long enough to complete his term (2006-11), which we have seen is no small accomplishment in Haiti.

But all the aforementioned problems became minor when Haiti suffered the worst natural disaster in the history of the western hemisphere. On January 12, 2010, a devastating magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Port-au-Prince. Because Haiti could not afford to build sturdy buildings, the whole capital city was leveled.(137) Estimates of the death toll ranged from 100,000 to 220,000, with a few claiming 300,000; thousands more starved, and infectious disease epidemics added to the misery. Most of the dead could not be identified before they were buried in mass graves, while other victims may have been washed out to sea, meaning it is impossible to know for sure who died and who survived.

In January 2011, after twenty-five years in exile, Jean-Claude Duvalier returned to Haiti. He claimed he was back to help the country rebuild after the earthquake: "I'm not here for politics. I'm here for the reconstruction of Haiti." But while there was a welcoming crowd for him at the airport, the population hadn’t called for Baby Doc to come back. It appears more likely that he was trying to claim $4 million in a frozen Swiss bank account, which the Haitian government refused to return to Duvalier, claiming the money was of "criminal origin." Two days later, he was arrested and charged with corruption, theft, and misappropriation of funds committed during his dictatorship.

Duvalier was not held for long. Following his release, he roamed Port-au-Prince freely, attended government ceremonies, and ate meals with friends in fancy restaurants. He never did jail time, or experienced anything harsher than house arrest. And boy, did the wheels of justice grind slowly for him; he did not appear for a court hearing until February 28, 2013. To the surprise of many, Duvalier did testify about his rule before an investigating judge, and in 2014 another judge overturned an earlier court decision, ruling that Duvalier could face crimes against humanity charges. But nature caught up with Baby Doc before the prosecutors did; on October 4, 2014 he died of a heart attack.

In April 2011, Michel Martelly was elected president. Previously Martelly was a singer; since 1989 he has recorded forty-one albums (both live and in studios), using the stage name "Sweet Micky" (see the video below). From 2004 to 2007 he lived in West Palm Beach, Florida, to escape ugly politics at home. Because we are in the middle of his term, it is too early to tell if he will do better than the generals and politicians who ran Haiti in the past, but he will certainly be different. And after the Duvalier tyranny, it’s a safe bet he won’t do worse!

The 2010 earthquake left Haiti in need of complete rebuilding, physically as well as politically; it requires an "extreme makeover" on a national scale. Almost no infrastructure or economy remained after the earthquake; a democratic government existed, but it hadn’t worked very well, because so far the Haitians have had minimal experience in governing themselves without a strong leader. When one considers that Haiti is the second oldest country in the western hemisphere, after the United States, one realizes it is also the unluckiest nation in the hemisphere. The rest of the world has helped generously in the rebuilding effort, but of course it will be years to come before the job is finished.

At the end of a novel, movie or TV show, the author will answer all remaining questions, and tie up the loose ends, unless he or she is planning to make a sequel. In real life a story doesn’t end that neatly, and because the Haiti story isn’t over yet, you’ll have to come back at a later date to find out if the Haitians finally achieve their rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Expect me to write about it if I compose any future chapters for this work.

Peru: The Fujimori Decade

Alberto Fujimori became president on July 28, 1990, a date which also happened to be Peru’s independence day (see Chapter 3) and his birthday. Fujimori valued his independence, too, and refused to make any deals with the major political parties that might hinder his ability to act; for the same reason, he ignored the advisors who helped him get elected and consulted internationally respected specialists. And though he may not have been a politician before running for president, he quickly learned how to be one -- by not keeping his campaign promise on the economy.

To end the hyperinflation and satisfy the demands of foreigners with money to lend/invest, Fujimori enacted the same draconian austerity program that Vargas Llosa had proposed. It worked (inflation was brought down from 7,649% in 1990 to 139% in 1991), but it cost Peruvians so dearly that it came to be called the "Fujishock." To give one example, the price of gasoline shot up 3,000%. Real wages fell, jobs were eliminated, and about 5 million Peruvians were pushed below the poverty line, raising the number living in extreme poverty to 13 million, or 60% of the population. Many only survived only by earning a living in the "under the table" economy (something illegal like the coca trade, or anything where the government could not track the income, and thus could not tax it). Infant mortality rose, too; it was reported that each year, disease and malnutrition took the lives of 60,000 babies less than one year old, and 75,000 children under the age of five.

It would be unfair to blame all of this on Fujimori. When he moved on to other challenges besides inflation, he found that because he lacked a majority in Congress, he could not get his legislation through that body. Moreover, most Peruvians (68 percent, according to a 1990 poll) felt that the Shining Light (SL) movement was the nation’s most serious problem.(138) In the SL’s core territory, the Ayacucho region, government authority was non-existent. By the end of 1992, it was estimated that the SL had killed 28,809 people and caused $22 billion in property damage. And with more than half the population living in "emergency military zones," where the police and armed forces could operate without being responsible to the central government, they may have wondered who the real enemy was; we noted previously that the police and army committed quite a few atrocities as well.

By now the SL had become one of the world’s most brutal terrorist organizations. They claimed to be fighting for the peasants, like the Chinese Communist Party did after Mao Zedong became its leader, but most of their members were highly indoctrinated, poor, Mestizo teenagers from shantytowns; the SL leadership was white, middle-class, and university-educated.(139) And instead of recruiting peasants into their ranks, they ended up driving a lot of peasants from rural areas into the cities, or even out of the country.

The SL insurgency, obstructionism in Congress, and his falling poll ratings all must have been factors when Fujimori decided to do something really drastic. On April 5, 1992, he suspended the 1979 constitution, dissolved Congress, and dismissed other government agencies that might have interfered with his activities. In their place he installed a new agency called the Government of National Emergency and Reconstruction. With his position now secure, Fujimori revised the constitution to make the government more up-to-date, called for new congressional elections; and went to work on the economy, selling all 200 state-owned companies that were losing money, and making Peru attractive to investors again.

We saw this kind of coup, an autogolpe (coup from within), pulled twenty-two years earlier, by Ecuadorean president Velasco.(140) Fujimori got away with it because Peruvians had seen caudillos before; many felt that a temporary suspension of freedom would be needed to get rid of the guerrillas. Indeed, most criticism of this move came from abroad; e.g., the United States suspended all military and economic aid, while other nations and lending institutions cancelled planned loans.(141) And for better or for worse, Fujimori had shown by now that he was very efficient.

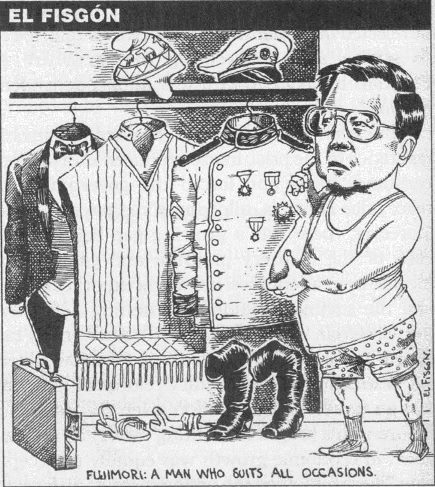

In this cartoon, Fujimori discovers that whether he is dressed as president, private citizen or dictator, he can still promote free-market capitalism.

The SL and MRTA welcomed the autogolpe and Fujimori’s political reforms at first, thinking that they would make the government more oppressive and drive more Peruvians into their ranks. But the expected oppression did not materialize, and with the police and soldiers now re-armed, a new offensive was launched against the guerrillas. In addition, the SL became the enemy of the poor when it infiltrated the shantytowns of Lima and tried to take over the local organizations (e.g., neighborhood committees, soup kitchens, and various church groups) by force. They lost friends and alienated more people by murdering ten civic leaders, including María Elena Moyano, the beloved deputy mayor of Villa El Salvador (a shantytown with 350,000 people), and by detonating deadly truck bombs in Miraflores, another Lima neighborhood. By the end of 1992, the leaders of both the SL and the MRTA had been captured; that went a long way towards breaking the ability of those organizations to fight.

Fujimori went through a very public divorce in 1994. His wife, Susana Higuchi, revealed information about their relationship that embarrassed him considerably, called him a "tyrant," and threatened to run against him in next year’s presidential election. Once she was gone, Fujimori promoted his daughter, Keiko Fujimori, to the office of first lady, though she was only nineteen years old. This made her the youngest first lady in Latin American history, and allowed her to launch a political career of her own after the twenty-first century began.

However, Fujimori got in far worse trouble because of the behavior of his most trusted advisor. This was Vladimiro Montesinos Torres, the chief of Peru’s National Intelligence Service. Montesinos certainly had a shady past; in 1976, when he held the rank of captain, he had been expelled from the army for selling military secrets to the United States (they were details on the Soviet-arms Peru bought, see footnote #30), and spent a year in prison for that act. After getting out, he earned a degree in criminal law and made his fortune by defending and representing drug traffickers. During the 1990 election he got a faction of the armed forces to back Fujimori; that faction became Fujimori’s main base of support, and Montesinos became Fujimori’s right-hand-man for making that arrangement. Afterwards, several members of the armed forces accused Montesinos of having too much influence over their promotions. Some observers have compared him with infamous advisors in the past, like Lucius Sejanus of first-century Rome or Russia’s Rasputin.

Still, it would be a few more years before the dirty dealings of Montesinos were revealed. In the mid-1990s most things were going Fujimori’s way. In March 1993 the administration of the new US president, Bill Clinton, decided that Peru’s human rights record had improved enough to resume financial assistance in fighting the guerrillas and the drug trade. For the previous year, inflation was down to 56.7 percent, the lowest since the 1970s. The budget was balanced and the foreign debt was under control. Finally, Fujimori avoided looking like a caudillo, though he had the power of one; for example, he visited shantytowns and rural squatter settlements every week, something most dictators dislike doing. For those reasons, his approval rating was now always above 60 percent, and when presidential elections were held in 1995, he easily beat his opponent, former UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, without the need to rig the results.

Originally, Fujimori had predicted he would finish off the SL before his first term was over. But in one aspect fighting a guerrilla force is like fighting cancer; sometimes you cannot be sure you got it all. For the Peruvian guerrillas, their last gasp came in December 1996, when members of the MRTA attacked the Japanese ambassador’s residence during a party and took hundreds of hostages. While most of the hostages were soon released, seventy-two men were held until April 1997, when military commandos stormed the embassy. In the battle that followed, all fifteen hostage takers, one hostage and two commandos were killed. Technically this was a victory for the government, but later it was discovered that at least eight of the kidnappers had been shot after they surrendered, on orders from Vladimiro Montesinos.

When I wrote about US history, I noted that almost every president of the United States who served for two terms did not do as well during the second term as he did during the first. It was a similar story for Fujimori; he seemed to lose his competence after 1997. For a start, the people felt that the war against the SL and MRTA was over, so Fujimori did not need to act like a dictator anymore. His popularity fell, and when the 2000 election arrived, he ran for a third term, though his own constitution did not permit it. He defeated his opponent, Alejandro Toledo, and allegations of vote fraud broke out. Then just weeks after the new term began, videos began to surface that showed Montesinos committing various crimes: bribing an opposition senator to support Fujimori, paying a radio station to not broadcast any ads or programs from opposition parties, drug smuggling, vote tampering, embezzlement and arms trafficking.

The uproar over the "Vladi-videos" was so bad that Fujimori announced there would be new elections in April 2001, and this time he would not run. In November 2000, he went to Brunei to attend a conference of Pacific Rim nations, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Forum. While there, he decided it would not be safe to return to Peru, so when he left the conference, he went to Japan instead. From the safety of his ancestral homeland, he faxed his resignation to Lima. Congress refused to accept it; they voted him out of office after declaring him "morally disabled," and installed a caretaker president in his place. Seeing which way the winds were blowing, Montesinos fled Peru too, seeking asylum in Panama.

This is the end of Part V. Click here to go to Part VI.

FOOTNOTES

115. In the mid-1950s, the Costan Rican government survived a brief border war with Nicaragua because the United States intervened. Another brief invasion occurred more recently, because the border between the two countries is disputed around the San Juan River. One day in November 2010 a Nicaraguan army unit crossed the border, advanced almost two miles into Costa Rican territory, cut down a protected forest, took down a Costa Rican flag and replaced it with a Nicaraguan one, cleaned out the river, and dumped the sediment they dredged from the river on its Costa Rican side. Obviously the troops did not think they were trespassing; the Costa Rican flag should have warned them they were off-course! Afterwards the Nicaraguan commander, Eden Pastora, blamed the mistake on Google Maps. Sure enough, the mighty search engine’s map put the border 3,000 meters east of where it really is (Nicaragua and Costa Rica agree on where the border is located, they just disagree on where it should be.). Now if Pastora had used Bing.com, which has a correct map for the region, or if he had used old-fashioned paper maps, this whole embarrassing incident probably wouldn’t have happened.

116. While these acts would have marked Arias as a statesman in any country, let the record show that even statesmen aren’t perfect. During the 2006 election, he caused some controversy by calling himself an "eagle" and his opponents "snails." When another candidate, Ottón Solís, challenged him to a debate, Arias turned him down by saying, "Eagles live on high and see from on high, and don’t bother to watch what the snails are doing." Then in 2010, as his second term drew to a close, he seemed eager to get the credit for finishing as many building projects as possible, instead of leaving them to his successor, Laura Chinchilla. At that time, he participated in ribbon-cutting ceremonies for the new National Stadium, an expansion of Juan Santamaria International Airport (see Chapter 4, footnote #33), and a complex of "new presidential offices." A ribbon-cutting is supposed to mean the project is ready for use, but the stadium was only 75% completed, and the addition to the airport was 82% completed. The office complex was a bare plot of land where construction had not started; the Legislative Assembly had not even bought the land yet!

117. The Sandinistas were not as popular on the east coast of Nicaragua as they were in the west, in part because after Nicaragua annexed the "Mosquito Coast" in the late nineteenth century, this region remained as neglected as it had been in colonial times. The black, mulatto and Indian minorities living here were as likely to speak English as Spanish, were often Protestant instead of Catholic, and poorer than the Latino majority. This ethnic divide is still causing problems for Nicaragua today.

118. President Reagan once called the Contras "the moral equivalent of our founding fathers."

119. However, Humberto Ortega remained in command of the army until 1995.

120. Ecuador’s dependence on oil money means the country has suffered badly whenever world oil prices dropped, most recently in the second half of 2008.

121. The current administration of Rafael Correa has appointed a special commission to investigate the human rights violations of his predecessors, and because Correa is a leftist, while Febres-Cordero was a conservative, he takes special interest in the allegations of what happened during the Febres-Cordero administration.

122. Congress had already passed a bill that called for amnesty for the general, but Febres-Cordero refused to sign it. After the kidnapping incident, though, he pardoned the general.

123. The odd name meant "Alfaro Lives, Dammit!", and referred to Eloy Alfaro, the former president who was murdered in 1911.