| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Africa

Chapter 8: "WIND OF CHANGE", PART II

1914 to 1965

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| World War I | |

| Troubles in the Italian Empire | |

| The Beginnings of African Nationalism | |

| The Rif War and Maghreb Nationalism | |

| The Road to World War II Passed Through Ethiopia | |

| The Liberation of French Africa | |

| The See-Saw Struggle in North Africa | |

| Decolonization Begins | |

| North Africa Rejoins the Arab World |

Part II

| The Algerian War | |

| The Mau Mau Rebellion | |

| "The African Year": Independence Below the Sahara | |

| The Congo Crisis | |

| South Africa and Rhodesia: Segregation Forever | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

The Algerian War

Algeria was the most unhappy part of North Africa in the mid-twentieth century. There were a million Europeans living here by now, who passionately believed in Algérie Française (French Algeria), and they both scorned and feared the land's Moslem majority. The first sign that trouble was on the way came on May 8, 1945, the day World War II ended in Europe; in the town of Sétif, Algerian demonstrators attacked a crowd of Europeans celebrating V-E Day, killing more than a hundred of them. Savage reprisals followed, which killed thousands of natives and saw the bombing and destruction of villages that had not seen any acts of violence. All this served only to harden the attitudes of both the settlers (who were sometimes derisively called pieds noirs, meaning black feet) and the Algerians. In 1947 Algeria was given its own parliament, which in effect made it autonomous from France, but because membership was weighed heavily in favor of the settlers, it proved ineffective at defusing the situation. Many nationalists despaired of ever achieving equality in a French-run Algeria, and some of them took up guerrilla training for the war they now saw as inevitable.

The Algerian nationalists got the organization they needed in March 1954, when nine of them founded the FLN (Front de Libération Nationale). That summer they received news of France's humiliating defeat at the hands of Vietnamese communists (the siege and fall of Dienbienphu), and concluded that they, too, could beat the French. Accordingly, they launched their war for independence on November 1, 1954, with a series of bombings and raids all over Algeria. However the French army was ready for them, and because it was no longer tied down by a war in Southeast Asia, it responded with overwhelming force, so that the rebels only had firm control over Kabylia and Aurès, two remote mountain ranges which had been their original bases.

At first all advantages were with the French. They had the advantage in arms and technology, which allowed them to control the cities and move about freely in the daytime. Over the next two years they brought in reinforcements, until 400,000 French troops were stationed in Algeria. Paris also appointed a liberal governor for the colony, Jacques Soustelle, in the hope that the Algerians would be willing to end the war by talking peace with him. However, any plans Soustelle had for defusing the conflict were dashed on August 20, 1955, when 80 FLN guerrillas went to a suburb of Philippeville and killed 123 people, including women and children. The French responded by tracking down and killing as many as 12,000 Algerians in the region the guerrillas came from. Atrocities mounted on both sides; the FLN attacked not only Europeans, but also terrorized Algerians into supporting their cause; their tactic of cutting the throats of enemies became known as the "Kabyle smile." On the French side, the paratroopers defending Algiers found that the field generator for an electric telephone could also be connected to prisoners and used as a fiendish torture device. Soustelle himself gradually moved to the right in his views, now preferring armed confrontation to negotiation, and the colonists, who were suspicious when he first became governor, came to see him as their champion.

On the international scene, most foreigners sympathized with the FLN. Nasser supported them from the start, allowing the FLN to establish its political headquarters in Cairo (that's why France took part in the 1956 campaign to topple Nasser, along with the British and Israelis). Arms were smuggled to the rebels from Morocco and Tunisia, prompting the French to block the Algerian-Tunisian frontier with an electric fence and minefields, the Morice Line, in 1957. In October 1956 the French air force intercepted an airliner flying from Morocco to Tunis and forced it to land in Algiers. On that plane were five top-ranked members of the FLN, including the movement's leader, Ahmed Ben Bella. However, the arrest and imprisonment of these men did not kill the movement; instead, it raised the FLN's profile, got the United Nations to discuss the Algerian situation, and eventually attracted more outside support to FLN. France found itself winning the military war, but losing the political one.

The largest urban engagement of the war, the battle of Algiers, lasted from January to March of 1957, and ended in a French victory. Despite this, the French armed forces were no closer to winning, but it was considered unthinkable to quit the game; no French politician would admit that the only solution was to uproot the pieds noirs and give independence to Algeria. When Guy Mollet, a socialist prime minister, went to Algiers in 1956 to see the situation first-hand, angry colonists greeted him by throwing rotten tomatoes. And when oil was discovered in the southern Algerian desert in 1957, the French saw that as another reason to hold on at all costs.

Because the Fourth Republic had proven itself too weak to handle Algeria, settlers and right-wing soldiers joined forces to overthrow it. In May 1958 they set up a Committee of Public Safety in Algiers, and demanded that Charles de Gaulle be made the next prime minister; by this time many Frenchmen saw de Gaulle as the only person who could save French Algeria. De Gaulle, who had been waiting a decade for such a call, was given emergency powers to write a new constitution, an event which marks the end of France's Fourth Republic and the beginning of the Fifth. Meanwhile, the rebels set up a government-in-exile in Cairo, with Ferhat Abbas as prime minister.

It looked for a while that the old general would indeed win the war. The offensive he launched in Kabylia (Operation Binoculars, July 1958) was highly successful; afterwards 1.25 million Moslem villagers were relocated to "regroupment camps," and much of the countryside was devastated to keep supplies from getting to the FLN. But de Gaulle was also willing to think the unthinkable, and do something about it. He realized the war was unwinnable, so his real goal was to get out of Algeria with as few losses for France as possible. While he reassured conservatives by promising not to lose any battles, he pursued what he called the politique de l'artichoux ("artichoke policy"); step by step he stripped away the political power of right-wing generals, settlers and reactionary administrators, like leaves from an artichoke or cabbage. Then he proposed a referendum to give self-determination to the Algerians.

When the pieds noirs realized what was happening, they organized their own militia, the OAS (Organization de l'Armée Secrète), and vowed to fight to the death. In 1960 they launched a terror campaign in both Algeria and France, and even launched a mutiny against de Gaulle in 1961. However, de Gaulle persuaded most of the armies to remain loyal to him, and opened secret negotiations with the FLN. They finally agreed to a cease-fire, the Evian Accords, in March 1962. In July the referendum took place, and the vast majority of Algerians voted for independence. Most French citizens were willing to accept this result; by now OAS atrocities had killed the emotional attachment many of them had for Algeria.

Few wars for independence have seen as much nastiness on both sides; 500,000 of Algeria's nine million people were killed before it was over. The OAS tried to stay and fight on, figuring it could hold on to a piece of Algeria if Europeans made up the majority of its population. Instead, 80 percent of the pieds noirs emigrated by the end of 1962, rendering even this last-ditch effort impossible. Back in Algiers, Ahmed Ben Bella emerged as the leader of a one-party socialist state, and reprisals against pro-French Algerians began. Because of the bitter struggle Algeria had gone through to throw off European rule, Ben Bella would oppose anything that looked like neocolonialism in Africa, and he became one of the most vocal critics against the white-ruled governments in South Africa and Rhodesia.

The Mau Mau Rebellion

After World War II the British realized that they would have to let go of their African colonies someday, so they followed the same procedure that had worked for Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. First they set up legislative councils to directly govern the colonies; then the governors and chiefs appointed Africans to serve in those councils; finally, when enough Africans had experience in self-government, free elections would be permitted to determine each colony's future. In West Africa this posed no problem; the tropical climate was so hostile to Europeans that none wanted to live there permanently, meaning that the local governments couldn't be managed by non-Africans for long. On the other hand, the East African colonies had seen little nationalist activity to this point, so London thought they would not be ready for independence for at least 20 years; the general opinion was that Africans are "and must be, for a long time yet, wards in trust."(17) As a result, Europeans were free to move in and settle on the best lands in Kenya, Tanganyika and Rhodesia, causing tensions to increase, rather than decrease. This was especially the case in Kenya, where so many whites set up farms around Nairobi, that the area became known as the White Highlands. The tribe displaced, the Kikuyu, was forced to share 2,000 square miles of land between 1.25 million people, while 12,000 square miles went to a mere 30,000 whites. For many natives, the only jobs available were as tenant workers on European-owned farms. Overcrowded and impoverished, the Kikuyu had a ready grievance, and in Jomo Kenyatta (1894?-1978) they found an eloquent leader.

Kenyatta was a thoroughly Western-educated African; he had spent seventeen years in England, married and divorced an English wife there, and even played an African chief in the movie Sanders in the River. Still, he had belonged to a nationalist group, the Kikuyu Central Association, in the 1930s, and because it had been banned during the war as a subversive movement, he joined another, the Kenya African Union (KAU), when he returned to Africa in 1946; one year later he became its president. Still, the British were not overly concerned with the Kikuyu, because they were not one of "the martial races," as they liked to call tribes with a warrior tradition. Instead, they were worried that an independent, majority-ruled Kenya would be unfair to the Europeans, so they were against setting up any form of government that guaranteed "one man, one vote." In May 1951 the British Colonial Secretary, James Griffith, visited Kenya, listened to the demands of the KAU, and then proposed a legislature which would give 14 representatives to the 30,000 Europeans, six representatives for 100,000 Asian (mostly Indian) immigrants, one representative for 24,000 Arabs, and five representatives for the five million Africans; in addition the African representatives would be appointed by the government, not elected. To any African nationalist, this was simply unacceptable.

By this time, many Kikuyus had decided to take matters into their own hands. To win the support of the masses, tribal leaders encouraged them to take an oath that promised their total commitment; breaking this oath meant ostracism from the tribe, in addition to other penalties. Then they held mass meetings to rally more support to the cause; more than 25,000 gathered for one meeting in the town of Nyeri, in July 1951. Rumors appeared, largely spread by the white settlers, that the tribal activity was led by a secret society called the Mau Mau, and that their oaths involved cannibalism, necrophilia, bestiality, and the drinking of blood. How much of this was true is questionable; in fact, it is not even clear that an organization by that name existed.(18) Nevertheless, when acts of violence broke out in October 1951, aimed mainly at white farmers and Africans loyal to the British, it was enough to make the government outlaw the Mau Mau and declare a state of emergency.

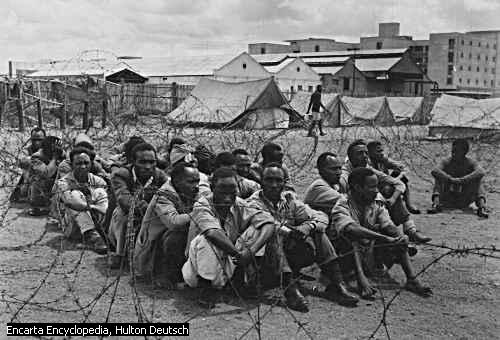

Kenyatta was arrested and charged with leading the uprising; though he strongly denied this, he spent the rest of the 1950s in prison or under house arrest. As British troops moved in to restore order, they attracted international attention all out of proportion to the size of the rebellion; most of the Mau Maus were poorly armed and organized. 92 Europeans and 1,920 Africans were killed by them, while the British army in turn killed 11,500 Mau Maus and their supporters. 90,000 Africans were also processed through detention camps to find Mau Mau members and others who had taken tribal oaths; all of Nairobi was emptied for this purpose at one point. For their prisoners, the interrogators announced a form of "counter-magic"--a new oath that would free the subjects from the Mau Mau oath. However, the Kikuyu didn't really believe there was a cure for their oaths, so many Mau Maus took it willingly to get released. Eventually the Mau Maus were confined to Mt. Kenya and the Aberdare forest, and these areas were taken in 1956, ending the rebellion.

Captured Mau Mau suspects in detention.

Though the Mau Maus were defeated, it came at too high a price; the British had spent £60 million and committed 50,000 soldiers. Realizing that it would cost as much, if not more, to keep the whites in charge of the colony, they now saw Kenyatta as the best hope for the future. When independence finally came in 1963, Kenyatta was the logical choice to become president; by this time he was sixty-nine years old, so his subjects reverently called him mzee, "the grand old man." Despite his long period of imprisonment, he acted remarkably generous, promising he would do nothing to harm the whites. Though some Europeans left after independence, there wasn't a mass exodus like Algeria had, so Kenya started off as one of Africa's most stable and successful nations.

"The African Year": Independence Below the Sahara

As we noted before, everyone expected the Europeans to stay in Black Africa much longer than they had stayed in North Africa, but once the light of nationalism caught on below the Sahara, it produced a rapidly spreading brush fire that nobody could stop. As we noted before, West Africa had fewer European residents than other parts of the continent, so independence came to that region quickest and with the least amount of pain. Leading the way was the Gold Coast, Britain's richest and most developed colony in West Africa. The one who got the Gold Coast moving was Kwame Nkrumah (1909-72), so it would be appropriate to step back a few years and look at his early life.

The son of a goldsmith in a small village on the Gold Coast, Nkrumah managed to get an education when his mother sent him to a Catholic missionary school in another village. There he did so well that he became an untrained elementary school teacher, and then went on to Achimota College, near Accra. Graduating at the head of his class, Nkrumah then taught at several Catholic schools, and considered becoming a priest, but now his ambitions were too big to stop there. In 1935 he got the opportunity he was seeking, when a rich uncle and the aforementioned Dr. Azikiwe arranged for him to go to the United States. He studied first at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, where his class voted him "most interesting," then at Lincoln Theological Seminary, and finally at the University of Pennsylvania. During these years he also did a lot of reading on the side; his favorite book was The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey (by Marcus Garvey, see footnote #4), and he was also heavily influenced by the three most famous communist writers--Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin. When he sailed from the United States in 1945, he looked back at the Statue of Liberty and said, "You have opened my eyes to the true meaning of liberty. I should never rest until I have carried your message to Africa."

In London, Nkrumah meant to study law, but he got involved with a Marxist group instead. In 1947 he returned to his homeland, and found it in turmoil. To quell riots, the British had just introduced a constitution that gave a majority of seats in the Gold Coast legislature to Africans, but to those wanting independence, it wasn't enough. Opposing it was a nationalist party called the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), and it asked Nkrumah to become the party's general secretary. The UGCC was made up of chiefs, lawyers, businessmen and rich farmers--men inexperienced in politics--who so far had not accomplished much, so they hoped that with Nkrumah in charge, they would do a better job of getting their message to Africans that weren't Western-educated, and that he would give the party the organization it needed. That he did, and more; the following year saw violent demonstrations, and the British arrested six UGCC leaders, including Nkrumah. Then the British set up an all-African committee to rewrite the constitution, and because Nkrumah's colleagues were having second thoughts about using violence to achieve independence, they were invited to join the committee, but Nkrumah wasn't invited. Deciding that the UGCC was too conservative and timid, Nkrumah left it to found his own party, the Convention Peoples Party (CPP).

For organizing a series of strikes that nearly brought the Gold Coast economy to a standstill, Nkrumah was imprisoned again in 1950. The same year saw a new constitution go into effect; it provided an all-African Legislative Assembly, and had eight of the eleven cabinet members chosen from the Assembly, with the governor appointing the other three. Nkrumah denounced it as another imperialist fraud, and offered instead the slogan "Self-Government Now." Nevertheless, the new constitution worked in his favor. When elections were held in 1951 to fill the seats in the Assembly, the CPP won most of them; Nkrumah, though he had to campaign from a prison cell, won the seat representing central Accra by a landslide. The British governor, Sir Charles Arden-Clarke, had an abrupt change of heart; he released Nkrumah and invited him to lead the new government. Nkrumah agreed, and promised to abandon his "Self-Government Now" campaign if there was real progress toward independence. After that Nkrumah and Arden-Clarke gave each other their full cooperation, until independence came on May 6, 1957. As prime minister of the new state, Nkrumah wanted to erase memories of the imperialist past, so he renamed the Gold Coast after a glorious kingdom that once existed in medieval West Africa--Ghana (see Chapter 5).

Kwame Nkrumah.

For a while after World War II, France thought it was business as usual in Africa; there was a revolt in Madagascar (1947-48), but it was put down as easily as previous uprisings. This time the Malagasy rebels didn't even have guns; instead, they tried a form of magic, chanting "Rano, Rano" ("Water, Water") when they saw enemy soldiers, thinking this would turn bullets into water! Needless to say, it didn't work.

As in Algeria, the French did not really expect their colonies to become completely independent. Instead, they hoped they would want to remain part of France if it meant an improved life for Africans. Several high-ranking members of the Free French government met in Brazzaville in 1944, to draw up a plan for administering the colonies after the war. They called for a French union, in which the colonies would have seats in the National Assembly in Paris, but not self-government. This never went into effect, though, because the wars in Indochina and Algeria got in the way. When Charles de Gaulle became president in 1958, he proposed a French version of the British Commonwealth, the French Community, of which each colony would be an autonomous member, with self-government at home but retaining economic and military ties with France. Then he told the African colonies to choose whether or not they wanted to join the French Community. Most went with the plan; only Guinea, led by Ahmed Sekou Touré (a great-grandson of the Samori Touré who had opposed the French conquest of West Africa) chose full independence. What de Gaulle didn't say was that independence would come with a price; he immediately canceled all French financial aid to Guinea, and over the next two weeks, 4,000 teachers, lawyers, doctors, and civil servants got out. They took paperwork, generators, and even telephones with them, leaving Guinea devoid of an infrastructure.

If de Gaulle was trying to teach Guinea a lesson, it had the opposite effect. Sekou Touré immediately became a hero to Africans, Ghana provided a £10 million loan to keep Guinea's infant economy from collapsing, and the Soviet Union promised more aid. The other colonies started having second thoughts about staying with France, and de Gaulle realized that he would have to fight a third colonial war to keep West and central Africa. Thus, the idea of a league of French-speaking nations died before it became a reality.

By this time, both the rulers of France and Great Britain realized that Ghana and Guinea were not unique; soon every African colony would be demanding independence, and saying no to them would only cause trouble. Kwame Nkrumah explained it thusly before Ghana became independent, when critics warned him that Africa wasn't ready to stand on its own: "We prefer self-government with danger to servitude in tranquility." Even the Belgians, who had expected to stay in the Congo forever, now suddenly decided to pull out. Harold Macmillan, the British prime minister, spoke about this trend in his famous "Wind of Change" speech, which he gave to the South African parliament at Cape Town in 1960, in the hope that South Africa would stop getting in the way of progress:

"We have seen the awakening of national consciousness in peoples who have for centuries lived in dependence upon some other power. Fifteen years ago this movement spread through Asia. Many countries there of different races and civilizations pressed their claim to an independent life. Today the same thing is happening in Africa and the most striking of all the impressions I have formed since I left London a month ago is of the strength of this African national consciousness. The wind of change is blowing through this continent, and whether we like it or not this growth of national consciousness is a political fact, and our national policies must take account of it."

1960 is sometimes called the "African Year," because that was the year when nationalism hit the jackpot; seventeen new African nations were born in that year. Most of them were former French colonies; in one stroke France chose to liquidate its entire empire below the Sahara, except for French Somaliland and the Comoros. French West Africa was broken into eight component territories: Senegal, Mauritania(19), Mali(20), Niger, Upper Volta, Ivory Coast, Togo and Dahomey. Likewise, French Equatorial Africa was split into five states: Chad, the Central African Republic, Cameroon(21), the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon. In addition to that, three of modern Africa's largest countries were turned loose; the British released Nigeria, the Belgians released their part of the Congo(22), and the French released Madagascar, which promptly renamed itself the Malagasy Republic. Finally, Italian Somaliland became independent five days after British Somaliland, and the two merged to form Somalia.

Nigeria was a special case because of its huge population, and because there was more than one major tribe: the Fulani and Hausa in the north, the Yoruba in the west, and the Igbo (also spelled Ibo) in the east. Only a federal government was likely to work under these circumstances, so while the British began preparing Nigeria for independence in 1951, the same year as for Ghana, the transition process took three more years to complete. The result was a dominion state like Canada, where the constitution loosely held together three states (called simply the Northern, Eastern and Western Regions); Queen Elizabeth II was the ultimate head of state, Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, a Hausa, was elected to be the first prime minister, and Nnamdi Azikiwe, who was an Igbo, became governor-general. The Yoruba were represented by Chief Obafemi Awolowo, who became the opposition leader. Even so, this carefully worked out compromise didn't satisfy everybody; bitter disputes arose over the accuracy of the 1962 and 1963 censuses. In October 1963, Nigeria altered its relationship with the United Kingdom by proclaiming itself a federal republic. The Queen was removed from the hierarchy, and Azikiwe became Nigeria's first president. The easternmost part of the Western Region was detached to become a fourth state, the Mid-Western Region, because its ethnic makeup wasn't Yoruba. Matters got worse when Awolowo's party, the AG, was maneuvered out of power in the Western Region and replaced by another Yoruba party that was more conservative and pro-government, the NNDP. Soon, Awolowo would be imprisoned on questionable treason charges; this was the first step in the slide toward Nigeria's civil war in the next chapter.

As the 1960s began, the "wind of change" spread to East Africa, where the British were no longer trying to make sure their colonies remained under white minority rule. 1961 saw Britain grant independence to Sierra Leone, Tanganyika (where nationalist leader Julius Nyerere and the governor had prepared the country for independence in only three years), and the British Cameroons. The latter were two strips of territory between Nigeria and Cameroon that had been awarded to Britain after World War I, so a plebiscite was held; the northern piece voted to join Nigeria, and the southern piece joined Cameroon. In 1962 the British withdrew from Uganda, and the Belgians pulled out of Ruanda-Urundi, which then split to become Rwanda and Burundi(23). Then Britain gave up Kenya and Zanzibar in 1963, Zambia and Malawi in 1964, and Gambia in 1965. These transitions went smoothly at first, until Zanzibar became independent. The British had left Zanzibar's Arab sultan in charge, though the island's population was mostly African; in January 1964, just four weeks after independence, a communist-inspired revolutionary group seized power, forcing the sultan (and most of his Arab and Indian subjects) to flee. Within days army mutinies broke out in Tanganyika, Uganda, and Kenya, led by younger army officers who wanted to give their own countries more radical governments. All three countries had to swallow their pride and ask the British to send troops, disarm the rebels and restore order. The long-term effect of this was that in April 1964 Zanzibar asked to join Tanganyika, forming a union called Tanzania; unlike other attempts to unite Africa, this one worked, and today there's no reason to believe the Tanzanian union won't last. Another effect was that Nyerere stopped acting like a moderate and began to pursue socialist policies, when forced to choose sides in the Cold War, for instance, he picked China for his closest non-African ally.

One problem that most of the new nations faced was a lack of development; most of what infrastructure existed had been created to connect each former colony with the mother country, but not with its neighbors. Sylvanus Olympio, the first president of Togo, explained it this way:

"The effect of the policy of the colonial powers has been the economic isolation of peoples who live side by side, in some instances within a few miles of each other, while directing the flow of resources to the metropolitan countries. For example, although I can call Paris from my office telephone here in Lome, I cannot place a call to Lagos in Nigeria only 250 miles away. Again, while it takes a short time to send an air-mail letter to Paris it takes several days for the same letter to reach Accra, a mere 132 miles away. Railways rarely connect at international boundaries. Roads have been constructed from the coast inland but very few join economic centers of trade. The productive central regions of Togo, Dahomey and Ghana are as remote from each other as if they were separate continents."

Another challenge was one of language; most African countries contain many tribes, and thus, the people use many languages. To understand each other, the citizens of any given country usually had to keep on using the language of their former colonial masters, rather than play favorites by using the language of one tribe. Thus, European languages, especially French and English, remained widely used after the colonial era ended. If the predominant religion was Islam, Arabic would be used, too. In this regard, the nations on the Indian Ocean were the luckiest, because their lingua franca didn't come from the white man; Swahili had been understood over a wide area for centuries, so they could use that instead.

After independence came, there was talk of an international organization to encourage cooperation between African states. Nkrumah thought this would be the first step toward creating a United States of Africa, but this was too much for most other heads of state, who didn't want to give up the sovereignty they had so recently won. Instead, they experimented with economic unions, an African "common market." Along that line, Nkrumah got Guinea, Mali, Morocco, Algeria and Egypt to join with Ghana in committing themselves to socialism in January 1961; this became known as the Casablanca Group. Four months later, the other former French colonies, Ethiopia, Somalia, Nigeria and Liberia formed the Monrovia Group, mainly to present a moderate alternative to the Casablanca Group's radical vision. During the Congo civil war, these groups backed opposing sides, with the Monrovia group behind the United Nations and Kasavubu, and the Casablanca Group supporting Lumumba's party. Still other organizations were tried, but none of them lasted very long. Finally in early 1963, the two main coalitions talked about resolving their differences. They succeeded, and out of this came the Organization of African Unity (OAU), which had its first meeting in Addis Ababa on May 25, 1963.

Early on, the OAU endorsed the idea that no nation's borders should be changed. The frontiers of Africa had been drawn to suit Europeans, not Africans, but the continent had enough problems without worrying about wars between its constituent states. The typical state created by colonial-era frontiers was larger than the land held by any tribe, so several states ended up containing tribes which did not get along; Rwanda, Nigeria and Sudan are the best examples of this mishap. On the other hand, some tribes got split by political boundaries. Examples of these include the Ewe, who ended up in both Togo and Ghana, due to the division of German Togoland between the French and the British, and the Somalis, who currently have parts of their tribe in four countries.(24) But when Africans looked at post-independence conflicts in places like the Congo, they had to conclude this was the safest course of action.

The Congo Crisis

If any part of Africa was unprepared for independence when it came, it was the Belgian Congo. After independence, it had more problems than any other African state. We last looked at this huge territory in Chapter 7, when Belgium's King Leopold II was milking it for whatever profit he could get. The Belgian government took over the colony from the king in 1908, but terribly little was done to develop it over the next fifty years. Brussels treated the Africans like children, disciplining them when they misbehaved, and encouraging them to work for European-owned farms and mines, rather than following traditional means of making a living. They were not taught modern technical or administrative skills, lest they get the idea that they could run their own country. Although enough primary schools were built to teach literacy to almost half the population, there were only 16 people with college degrees and 196 high school graduates when independence came in 1960, out of 14 million people.

In 1955, Antoine van Bilsen, a Belgian professor, published a paper entitled Thirty-Year Plan for the Political Emancipation of Belgian Africa. He thought independence was thirty years away because no political elite had yet formed in either the Congo or Ruanda-Urundi, and these colonies were at least a generation behind the British and French ones in terms of development. Belgian authorities denounced him as a dangerous revolutionary, because they had no intention of leaving at all; most Belgians accepted the plan because it meant they could stay for thirty more years; African nationalists disliked it for the same reason that the Belgians liked it. But as it turned out, the Belgians would cut the Congo loose before anyone expected, including the nationalists.

In August 1958 Charles de Gaulle visited Brazzaville, just across the Congo River from Leopoldville, to announce to French Equatorial Africa his plan for autonomy within the French Community (see the previous section). Those in Leopoldville who heard about it began demanding independence, and this led to a major riot in January 1959. Order was restored in less than a week, but then the Belgian government looked at the rest of the Congo and Ruanda-Urundi, and saw tensions rising everywhere. This caused the authorities to abruptly change their minds about staying; if a war on the scale of the Algerian one broke out while they were there, it would be too much for a little country like Belgium to handle. At the beginning of 1960, several Congolese politicians were summoned to a "round table conference" in Belgium. They went expecting to hear the announcement of a five-year transition period, followed by independence, and were prepared to haggle with the Belgians over the details. Instead, they were simply told that independence would come in less than six months, on June 30, 1960. This wasn't enough time to form political parties on a national scale, or to train Congolese in the details of administration; it wasn't even enough time for the politicians to learn how to get along with each other.

Elections were held in May to form a Congolese government. Forty parties participated, so nobody won a majority. Most political parties at this stage were tribal-based; the typical voter belonged the same party that his tribe belonged to. The only politician who had more than a local following was Patrice-Emery Lumumba (1925-61), a former postal worker from Stanleyville who headed the radical Congolese National Movement. After lengthy negotiations, Lumumba and his chief rival, Joseph Kasavubu (1913?-69), the top politician in Leopoldville, formed a coalition government, in which Kasavubu would be president, and Lumumba would be prime minister. Then things started going wrong. Even the independence ceremonies were a disaster, promising a bad future for Belgian-Congolese relations; Belgium's King Baudouin delivered a patronizing speech, to which Lumumba responded with a diatribe against Belgian colonial excesses, declaring, "We are no longer your monkeys."

Within a week of independence, the Congo descended into chaos. The initial spark came from the military--because there were so few Congolese officers, the government decided to keep some white officers around until they could train their replacements. On July 5, a unit in Leopoldville mutinied after hearing from a Belgian general that he wouldn't promote Africans to the officer ranks right away; "things won't change just because of independence" was how he put it. African troops went on a rampage against Belgian officers and their families, Kasavubu and Lumumba tried to defuse the situation by promoting African officers as quickly as possible, and Belgium flew in more troops--quite against the government's wishes--to protect the 100,000 Europeans still living in the Congo. As law and order disappeared, everyone with a grudge seemed to come forth to settle it; Africans attacked not only Europeans, but also Africans from tribes they did not like. Virtually all remaining Europeans fled, leaving the new country without administrators, and white-collar workers in general.

The situation got much more complicated when secessionist movements kicked in. Moise Tshombe (1919-1969), the leader of the southernmost province of Katanga, declared independence from the rest of the Congo on July 11. Katanga had most of the Congo's mineral wealth (especially copper, uranium and cobalt), and 60 percent of the country's income came from these resources, so it was an area the Congo could not afford to lose. Meanwhile, the southwestern province of Kasai, a source of diamonds, also seceded, calling itself the "Independent Mining State of Kasai." Kasavubu and Lumumba now appealed to the United Nations for help, and a peacekeeping force, personally led by UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld, arrived to replace the Belgians and restore order.

The UN force was mostly made up of Africans, sprinkled with a few Swedes and Irishmen, so unlike the Belgian intervention, nobody could call the UN's involvement an act of imperialism. Between the departure of the Belgians and the arrival of the UN, the central government managed to retake Kasai, forcing its separatist leader, Albert Kalonji, into exile. But then the Security Council ruled that no UN forces could be used to affect the outcome of any conflict, so Tshombe allowed them to enter Katanga, using them as a buffer between himself and the Congo government. Disappointed that the UN would not help him recover Katanga, Lumumba then turned to the Soviet Union for aid. This convinced Westerners that Lumumba was a communist sympathizer, and both the Belgians and US President Eisenhower decided that Lumumba must go, before the Soviets could use him to establish a communist base in Africa. With their encouragement, President Kasavubu turned against Lumumba and dismissed him in early September. Lumumba refused to step down and dismissed Kasavubu. To break the deadlock, the army's chief of staff, Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu (1930-97), seized control of the government. He kept Kasavubu as president, but had Parliament transfer most presidential powers to himself, and placed Lumumba under house arrest; the Czech advisors sent by the Soviet Union were expelled. The UN decided to continue recognizing Lumumba as the rightful leader of the Congo, though it did him little good.

In December 1960 Antoine Gizenga, a former deputy minister under Lumumba, proclaimed himself prime minister at Stanleyville. Because he was one of Lumumba's supporters, most communist and Arab nations, as well as Nkrumah's Ghana, recognized his government, rather than the one of Kasavubu and Mobutu. When he heard the news, Lumumba escaped in a visiting diplomat's car from the Leopoldville residence where he was being held, and made his way toward Stanleyville. Mobutu's troops followed, and they caught up with him as he was trying to find a way across the impassable Sankuru River. Back in Leopoldville he was shown beaten and humiliated to journalists and diplomats, taken to Mobutu's villa, and beaten again before television cameras--but the Belgians and Americans wanted a more permanent ending to the affair. The Belgian minister for African affairs contacted Moise Tshombe, Lumumba's worst enemy, and told him he must accept Lumumba immediately. After a moment's hesitation Tshombe agreed, and Lumumba was flown to Elizabethville, the capital of Katanga, in January 1961.

Lumumba was beaten again on the flight, and driven by Katangese soldiers commanded by Belgians to Villa Brouwe, where he was tortured some more while Tshombe and his cabinet decided what to do with him. Later that night Tshombe and the soldiers took Lumumba and two other members of his government into the bush, and brought them before a large tree, where three firing squads were waiting. The morning after the executions, a senior Belgian policeman told Katanga's interior minister to get rid of the evidence: "You destroy them, you make them disappear. How you do it doesn't interest me." A few days later, Belgian Police Commissioner Gerard Soete and his brother dug the corpses from shallow graves, hacked them to pieces, dissolved them with sulfuric acid and finally burned them. When Lumumba's death was officially announced in February, it was reported that he had escaped and was murdered by angry villagers. Not many believed this story, and riots occurred in many parts of the world; the Belgian embassy was burned down in Cairo, and the USSR accused Hammarskjöld of being involved in Lumumba's death.(25)

In February 1961, Mobutu allowed Kasavubu to form a new provisional government. There were now four Congolese factions: Kasavubu's government in the west, Gizenga's government in the east, and the two breakaway provinces of Katanga and Kasai (Kalonji had returned to Kasai and reestablished control). Then the UN Security Council gave authorization to use force to prevent civil war in the Congo, and ordered all foreign military personnel to leave, unless they were under UN command. This was bad news for Katanga, which largely depended on white mercenaries (led by "Mad Mike" Hoare, a famous Irish adventurer) and now found itself up against the UN as well as the Kasavubu government. Negotiations among the leaders of the factions to replace the central government with a confederation of Congolese states began in March, and when Tshombe withdrew his cooperation in April, he was arrested by Kasavubu and charged with treason. He won his release in June by promising to dismiss all foreign advisors and troops in Katanga, but as soon as he got back to Elizabethville he reneged on his agreement and declared independence again.

The UN force in the Congo launched a limited but successful military action against Tshombe's forces in September. UN Secretary General Hammarskjöld then flew to the scene to meet with Tshombe, hoping to establish a cease-fire, only to have his plane crash in Northern Rhodesia, killing everyone on board. A second UN offensive, launched in December, was defeated because the Katangese had control of the air (no planes backed up the UN forces at this stage). Meanwhile to the north, Gizenga joined the central government as a vice prime minister when Kasavubu's new prime minister, Cyrille Adoula, promised to follow the policies of Lumumba, but Gizenga was dismissed in January 1962 after refusing to go to Leopoldville to face secession charges.

For much of 1962, Adoula and Tshombe tried to negotiate a settlement that would keep Katanga in the Congo. They failed to reach an agreement, in part because Tshombe's armed forces were melting away--international pressure forced Belgium to remove its officers from Katanga. Fearing that time was running out, Tshombe began harassment attacks against the UN. However, his troops went too far when they shot down a UN helicopter in December; this time the UN force had Swedish Saab jets, and the UN counterattack destroyed the Katangese air force on the ground. Then Katanga's army crumbled as the UN ground forces moved in to take Elizabethville. Tshombe was forced to surrender in January 1963, after receiving a promise of amnesty for himself and his followers. He went into exile in May, while Hoare and his mercenaries were rounded up and deported. Then a UN offensive in the northeast captured Stanleyville, destroying Gizenga's faction. For the first time since 1960, the former Belgian Congo was united under one government.

It would not last. In September, Adoula dissolved Parliament, and several members of Lumumba's party turned against him. The most important of these rebels, Laurent-Désiré Kabila (1939?-2001) and Christopher Gbenye, fled to the eastern border of the country and launched new uprisings. Another revolt, led by Pierre Mulele, Lumumba's education minister, broke out at the town of Kikwit, about 250 miles east of Leopoldville, in January 1964. Worst of all for Kasavubu, the UN had to withdraw from the Congo. Always operating on a budget that put it near bankruptcy, it had gone broke on the Congo operations; France and the USSR had refused to make any contributions, while the contributions of the USA and Britain led some to suspect they were using the UN to install a pro-Western government. Without the UN, President Kasavubu did not have the military force needed to keep Katanga from breaking off again. As a result, when Adoula resigned in June 1964, Kasavubu made Tshombe the next prime minister; the only way to keep the country united was to bring Katanga's separatists into the central government on their own terms. To strengthen the army, Tshombe brought back "Mad Mike" Hoare to recruit more mercenaries, and negotiated with US President Johnson for some T-28 armed trainers and B-26K light bombers, flown by exiled Cuban pilots working for the CIA.

The new soldiers and planes were needed because of the Simba (Swahili for Lion) rebellion, led by Gaston Soumialot. The Simbas were tribesmen motivated by the belief that they had become invincible. Witch doctors would cut scars on the faces and chests of Simba recruits, sprinkle "magic dust" in the wounds, place animal skins on them, close their eyes and fire guns in the air--and then they would tell the recruits that the guns had been aimed at them, but they had no effect. Now they thought they could not be killed as long as they followed the Simba code, by staying loyal, keeping themselves pure, and avoiding uninitiated folks like whites and educated blacks. When the Simbas marched on Stanleyville in August 1964, their reputation went ahead of them; 1,500 Congolese soldiers fled, leaving behind armored vehicles and mortars, after they had been scared by forty Simba warriors, led by witch doctors waving palm branches! Approximately 1,650 Europeans who were unlucky enough to be in the city were captured and held hostage.

The next few weeks saw the Simba rebellion spread rapidly, until it engulfed a third of the country. Discipline broke down, and the youth gangs put in charge of rebel-controlled areas behaved with cruelty, massacring possibly 10,000 Westerners and Westernized Africans. The only place where government troops stood their ground was in the eastern town of Bukavu, where they had air support (afterwards the Simba leader blamed his defeat on American atomic bombs!). In September a government counteroffensive began at Lisala, the point farthest down the Congo River reached by the Simbas. The combined force of Katangese, mercenaries and American planes was completely successful, and they went on to take the next town, Bumba. Instantly Simba morale collapsed, because it was proven that they can die; their magic failed to protect them from armored vehicles and warplanes. A second Simba attack on Bukavu failed disastrously, and government forces began advancing up the Congo River toward Stanleyville. When they got to Stanleyville in November, Belgian paratroopers recaptured the city and rescued the hostages. After that it was a mopping up operation; by the end of March 1965, both Mulele's revolt and the Simbas were all but crushed.(26)

Many Africans found it humiliating that the Congo government depended on white soldiers to stay in power; letting the Belgians intervene was an act of colonialism, from their point of view. Still, this didn't prevent anti-government factions from accepting white help when they needed it. Accordingly, Cuba sent Che Guevara, the famous Latin American guerrilla leader, with a team of Cuban revolutionaries, in April 1965. He had a dream of leading a continent-wide revolution--the continent where it happened didn't really matter--and thought that in a place as anarchic as the Congo, he could do it by delivering men and arms to Kabila. Since the western shore of Lake Tanganyika was still in rebel hands, his first plan was to turn that area into a training ground for new fighters. He traveled heavily disguised, with stops in Algeria and Tanzania, but the CIA knew he had gone to Africa. So did Egypt's President Nasser, who told Guevara not to go, warning that he could become "another Tarzan." American military advisors working with the Congolese army were able to monitor Guevara's communications, arrange an ambush against the rebels and Cubans whenever they tried to attack, and keep supplies and reinforcements from getting to them.

An absentee leader, Kabila was in Cairo and Dar es Salam, meeting with important foreigners like China's Zhou Enlai, so Che Guevara was largely on his own. This was not a good thing, because the Cubans and the Congolese didn't even share a common language, making it impossible to communicate most of the time. In June a letter arrived from Kabila with an assignment--he wanted the Cuban advisors and their trainees to attack Bendera, the site of a hydroelectric plant and a barracks containing 300 of Tshombe's soldiers and 100 of Hoare's mercenaries. It failed miserably and predictably; of the 160 men Guevara had available, sixty deserted before the attack began, and most of the rest never fired a shot. Four Cubans were killed and their papers and diaries were captured, revealing to the other side that Cubans were now involved in the Congo.

Kabila finally showed up in the war zone in July. By then Guevara was growing disillusioned. He had found out the hard way that Africa was not like Latin America. Whereas Guevara thought he was fighting "Yankee imperialism," most of the Congolese on his side were leftists in name only, claiming to follow Lumumba, but more interested in women and drinking than in ideology. As for the leaders, Kabila no longer got along with Soumialot or Gbenye, so it was difficult to present a united front against the enemy. Finally, Guevara was disgusted by the native reliance on magic and mystical customs, which didn't make any sense to him. The Congolese just didn't seem to be revolutionary material. Nevertheless, he stayed until November, when, ill and humiliated, he withdrew to Tanzania.

By that time, the civil war winding down. The principal African backer of Che Guevara and the rebels, Algeria, dropped out in June 1965, when Ahmed Ben Bella was ousted by a coup. Then in October Kasavubu dismissed Tshombe, who was clearly a liability; too many Africans saw him as the white man's stooge.(27) With Tshombe gone, his mercenaries had to leave, too, which removed the main reason why African states had opposed the central government; support for the rebels quickly dried up. However, Kasavubu didn't get a chance to enjoy his victory; on November 25 Mobutu, now a general, staged a second coup that removed him. This time, instead of using a front man, Mobutu installed himself as president, remaining firmly in control of the country for the next 32 years.

South Africa and Rhodesia: Segregation Forever

While most of sub-Saharan Africa saw political power turned over to the black man during the course of this chapter, the southernmost part of the continent proceeded in the opposite direction. The dominant political party of South Africa in the early twentieth century, the South Africa Party (SAP), was led by former Boer War veterans like Louis Botha and Jan Christian Smuts, but it mainly represented English-speaking whites, meaning that it emphasized good relations with Britain and tried to ignore the race issue. In 1914 General James Hertzog founded the National Party (NP) to promote Afrikaner interests, like putting the Afrikaans language on an equal footing with English. Despite this challenge, Botha ran the country until his death in 1919, whereupon he was succeeded by Smuts. For the next thirty years Smuts was South Africa's most prominent statesman. He made South Africa look respectable as long as he was in charge, was a good friend of Winston Churchill during World War II, and he made sure that South Africa would become a charter member of the United Nations after the war. However, he couldn't think of a solution to South Africa's racial imbalance, and preferred to postpone a resolution until a new generation took over.

In 1921 leaders of the country's gold-mining industry decided to replace white labor with black labor, figuring that they could get away with paying black workers less. This caused white miners to revolt in March 1922 and seize control of the Rand (the Rand Revolt). Prime Minister Smuts declared martial law and used the military to put down the revolt, but then in 1924 the miners teamed up with the NP to defeat Smuts in that year's election. Hertzog now took over, ruling until 1934, when the Great Depression forced him to form a coalition with Smuts, merging the NP and SAP to create the United Party. This coalition promoted white interests in general at the expense of the Africans; now the ultimate goal was to create two South African states, one white and one black, both part of the Union of South Africa, but the blacks would only have political rights in their own state.(28) One consequence of this policy was the passage of the Natives Representation Act in 1936, which took away the right of blacks to vote in the Cape Province, but increased the amount of land they could own from 7 to 13 percent of the country.

South Africa's white supremacist policy worked for as long as it did because it depended on black labor, and though typically blacks were only paid an eighth as much as whites, they still earned more money than they would have gotten in most other places. Because these jobs weren't located in or near the land assigned to Africans, they continued to live in large slums (the townships) around the white-ruled cities, though it meant a denial of rights and a requirement by law to carry passbooks, as if they were immigrant workers. In the years before 1948, a peaceful transition to a government for all races was possible, but nobody tried it because the white voters feared what might happen if they lost their status as a privileged minority. Consequently they tended to elect politicians with the most extremist racial views, figuring that this was the only way to keep South African society the way it was.

South Africa reached an important turning point with the 1948 elections. The NP won a majority of seats, though not a majority of votes; Daniel Malan, a hardline Afrikaner, became the new prime minister, while Smuts and the United Party were relegated to the opposition. Now that they controlled the entire government, the Afrikaners put into action their program to keep the country's races separate and unequal--forever. Called apartheid, Afrikaans for "separateness,"(29) it made South Africa's racial discrimination a formal policy, the most important part of the law of the land.

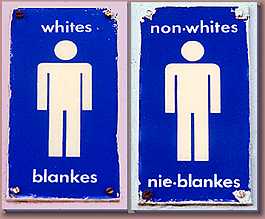

First, the government classified all South Africans into four racial categories: white, black, colored (mixed ancestry) or Asian. Then it stripped the nonwhite groups of all political and economic rights, and specified what neighborhoods they could live in, and what jobs they were allowed to have. Finally, various segregation laws were enacted to keep the races from mingling together. The end result was a society that looked very much like the southeastern United States in the "Jim Crow" era (1877-1965). Interracial marriage, sex and even most casual contact were forbidden. Hospitals, trains, busses, park benches, swimming pools, libraries, stadiums, beaches, movie theaters, and restaurants were all segregated, and the ones labeled "white only" were usually in better condition. Nonwhite schools were expected to give their students inferior educations, so that they would only be qualified for inferior jobs, and learn to accept working at them.

In South Africa, restrooms were segregated by race as well as by gender.

Of course there was opposition to these measures, but the government was more than willing to deal with it, no matter what the cost in lives or what world opinion might say. In 1952 the African National Congress and the South African Indian Congress (a political group for Asians) launched a civil disobedience campaign, which they called the Defiance Against Unjust Laws Campaign; the government passed emergency legislation to give itself dictatorial powers, and arrested 8,000. When opponents of apartheid drafted the Freedom Charter in 1955, which called for majority rule and equal rights for all races, 156 were arrested and charged with treason. They were all acquitted later, but it took six years to get them out of jail, during which time they couldn't take part in opposition activities. The most violent confrontation occurred in the village of Sharpeville, where on March 21, 1960, policemen broke up a demonstration against the passbook laws by shooting into the crowd, killing 69 and wounding 178.

To make it harder to oppose the regime, South Africa's intelligence service became the most efficient in the non-communist world. Even the definition of communism was expanded to mean any struggle for political, economic, or social change, giving the government an excuse for still more repressive measures during the Cold War years. The ANC responded by forming a military faction, the Umkhonto we Sizwe (Zulu for "Spear of the Nation") to carry out armed resistance. This led to the arrest of the ANC's most visible leader, Nelson Mandela, in 1962, and his sentencing to life in prison. In 1963 a law was passed making it legal to detain someone for up to ninety days without a trial, for interrogation purposes--for enemies of the government this detention could be renewed indefinitely.

Prime Minister Malan had two very similar successors, Johannes G. Strijdom (1954-58) and Hendrik F. Verwoerd (1958-66). Both of them were just as uncompromising when it came to supporting apartheid, and because the NP continued to gain parliamentary seats with each election, they felt they were moving in the right direction. In 1960, Verwoerd declared the country a republic, with himself as president, rather than prime minister, to reduce Great Britain's ability to criticize South Africa; one year later South Africa pulled out of the British Commonwealth for the same reason.

Because they were Christians who took their religion seriously, some Afrikaners had misgivings about the apartheid system; they wanted to stay in power without looking like they were denying even basic human rights to the blacks. Accordingly, in 1959 Verwoerd introduced a final solution to the racial problem, which he called the Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act. South Africa would prepare a decolonization plan of its own, in which the tribal homelands would be organized into ten "Bantustans" and prepared for independence; all blacks who wanted more freedom simply had to move to the Bantustans. The truth of the matter, though, was that the Bantustans would never be able to stand on their own. Not only did they have the country's poorest land, most were divided into several pieces, so that the residents would have to depend on South Africa's good will simply to travel from one part of a Bantustan to another. And because 13 percent of the land wasn't enough to support 75 percent of South Africa's population, most Africans would have to stay where they were--as cheap labor for white-run industries.

As long as South Africa's economy was healthy, with a GDP as high as the rest of the continent put together, apartheid looked like it was good for business. The rest of the world couldn't ignore South Africa's mineral resources, which included most of the world's platinum and chromium, and nearly one half of the gold and manganese, topped off by the famous South African diamond mines. Foreign investment in South African industry and the Johannesburg stock market continued to rise steadily until the Sharpeville massacre. And the nearest countries found their ability to act limited, because many of their citizens worked at South African jobs. Nearly every nation criticized South African policy, but without effective economic sanctions, nothing seemed capable of moving the implacable, self-righteous Afrikaner leadership.

On the other side of the Limpopo River, a similar system was established in Southern Rhodesia. When the charter of the British South Africa Company expired in 1923, Britain allowed the colony's European settlers to vote on whether or not they wanted to join South Africa. They voted no, so Southern Rhodesia got its own local government instead. At the same time, copper was discovered in Northern Rhodesia, so the next few years saw industrial development in both colonies.

After World War II, many white immigrants moved to this part of Africa. Before long, Sir Godfrey Huggins, the leader of Southern Rhodesia, and Sir Roy Welensky, his Northern Rhodesian counterpart, proposed that the two Rhodesias and Nyasaland be joined in a single federation. They argued that the three colonies had become interdependent; Nyasaland supplied labor to both Rhodesias, while Southern Rhodesia supplied manufactured goods and food. Together they formed a powerful economic unit, second only to South Africa on the continent. However, Africans were not yet trained to manage a modern economy and government, so Europeans would have to be in charge of everything. London agreed, and the white-run Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was set up in 1953.

During the next ten years, the clashing forces of settler intransigence and African nationalism tore the new federation apart. Nearly all the benefits of rapid economic growth went to the Europeans; in 1961, it was estimated that the average annual income of a wage-earning European was £1,209, while for a wage-earning African it was only £87. Government spending was even more unequal, with the Federation's 220,000 whites receiving 25 times as much per capita in educational spending as the 15 million blacks, to give one example. Africans began to demand a bigger piece of the pie, both economically and politically, but the politicians in charge of the Federation and South Rhodesian Parliaments refused to yield. Huggins wrote in 1956 that "Political control must remain in the hands of civilized people, which for the foreseeable future means the Europeans." Welensky was even more blatant; he didn't see the Federation as a partnership between equals, but something like the relationship between a rider and a horse, with the African as the horse! In 1959, a series of riots, strikes and demonstrations broke out, leading to states of emergency being declared in Nyasaland and Southern Rhodesia.

The settlers insisted that a handful of extremists were responsible for the unrest; just lock them up and all would be well again. London wasn't convinced, and a commission sent to investigate the situation found out that "partnership was a sham." By this time, the British were no longer interested in enforcing white minority rule, after their experience in places like Kenya, so the Federation Constitution was rewritten in 1960 to give each colony more African representation in its government, and the right to secede from the Federation. As a result, Africans gained control of the local government in Nyasaland in 1961, and Northern Rhodesia in 1963. Neither of those colonies had a significant European population, and the nationalist leaders that emerged in each (Dr. Hastings Kamuzu Banda in Nyasaland, Kenneth Kaunda in Northern Rhodesia) announced they would leave the Federation at the earliest opportunity. Britain got the message, and the Federation was officially dissolved on the last day of 1963. Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia both gained independence a year later, under new names: Nyasaland became Malawi, and Northern Rhodesia became Zambia.

Many expected that the next step would be for Britain to grant independence to Southern Rhodesia (now called simply Rhodesia), once a majority-rule government was established. Instead, the white minority acted first. A new leadership, more extreme than its predecessors, came to power, announcing that its goal was independence without surrendering power to the blacks. To anyone who cared to listen, they pointed out that while their state on the surface resembled South Africa, it didn't have racism codified to the degree that apartheid was. Furthermore, in 1961 the blacks were given fifteen of the sixty-five seats in Parliament, and they could have more if enough whites joined them to provide the two-thirds majority needed to change the Constitution. As far as they were concerned, those concessions were enough, and they were appalled when Britain insisted on more progress toward majority rule. After all attempts to negotiate a compromise failed, Prime Minister Ian Smith declared Rhodesia an independent state on November 11, 1965. In a twisted view of what liberty meant, the first paragraph of his declaration deliberately sounded like the 1776 Declaration of Independence that created the United States:

"Whereas in the course of human affairs history has shown it may become necessary for a people to resolve the political affiliations which have connected them with another people and to assume among other nations the separate and equal status to which they are entitled . . ."

Smith finished by exclaiming "God Save the Queen!" as if he was still a loyal British citizen. For each of the next thirteen years, on the anniversary of the declaration, he would commemorate it by ringing a replica of the American Liberty Bell.

This was an embarrassing situation for the British, with Rhodesia's English-speaking settlers still claiming to be "British," but refusing to take orders from London. Nobody wanted to use military force against them, so Britain opted for economic sanctions. The UN agreed that a total blockade would bring down Rhodesia in a matter of weeks, and together they persuaded the rest of the world not to give diplomatic recognition to Ian Smith's regime.

In practice, though, it didn't work (sanctions rarely work, as the world has found out the hard way). Three of Rhodesia's neighbors also had white leadership--South Africa and Portuguese-ruled Angola and Mozambique--and they were quite willing to let vital supplies get to Rhodesia through their ports, and for Rhodesian exports to go out the same way. When the British tried to stop shipments of oil from going to Rhodesia by way of Beira, Mozambique, for example, South Africa let the oil pass through its territory instead, and even the world's superpowers didn't want to slap a blockade on South Africa. As time went by, white Rhodesians grew more intransigent. Liberal whites emigrated, taking the so-called "chicken run," while white farmers with a hardline attitude moved in from South Africa, seeking new opportunities. Thus, Rhodesia's 250,000 Europeans succeeded in imposing their will on six million Africans, at least for the short run, and Rhodesia joined the bloc of states in southern Africa that resisted the "wind of change." They couldn't defy the world forever, but getting them to realize this would take years, not weeks or months.

This is the End of Chapter 8.

FOOTNOTES

17. Kenyatta, Jomo, Facing Mount Kenya, London, 1938, pg. xxi.

18. The origin of the name "Mau Mau" is just as mysterious. Some think it was made up by Europeans overhearing Kikuyus talking; others have suggested it was a Swahili acronym for Mzungu Aende Ulaya, Mwafrika Apate Uhuru -- "Let the white man go back abroad so the African can get his independence." Because the raiders usually attacked at night, and in small numbers, they never were easy to identify.

19. The capital of French West Africa was Dakar, in Senegal. When the French decided to break the colony up, they needed to choose a capital for each of the pieces. Mauritania, however, had no cities, so they picked the fishing village of Nouakchott, and like Alexander the Great did with Alexandria, they built the capital city from scratch. By the time independence arrived, Nouakchott had grown to 15,000 people; since then, a high birthrate and migrations from the countryside have swelled the population to an estimated 2 million.

20. In 1959, Senegal merged with Mali (then called French Sudan) to form the Mali Federation. They were still together when independence came in June 1960, but two months later, Senegal withdrew because of political disagreements. As it turned out, the Senegalese have more in common with a former British colony, Gambia, so those two countries might come together some day, in a union called Senegambia.

21. A pro-communist party, the Cameroonian People's Union, tried to seize control of Cameroon in 1956. Four years later, the French showed how anxious they were to leave, by granting independence while pro-communist and anti-communist forces were still fighting. It took until 1963 for Cameroon's first president, Ahmadou Ahidjo, to suppress the uprising.

22. Cartographers sometimes name each part of the Congo after its capital; thus, the former French Congo becomes Congo-Brazzaville, while the former Belgian Congo is either Congo-Leopoldville or Congo-Kinshasa, depending on what time period you're talking about. It was easier from 1971 to 1997, when the ex-Belgian Congo was called Zaire.

23. Rwanda was ruled by the Hutu tribe, and Burundi by the Tutsi. It became necessary to give them separate countries because Hutu riots had forced the last Tutsi king of Rwanda to flee in 1959. However, that wouldn't prevent the worst bloodbath in recent history, as we'll see in the final chapter of this work.

24. Shortly before independence came to Togo, Nkrumah proposed reuniting the Ewe tribe by making Togo part of Ghana. Olympio wanted nothing to do with the idea.

The flag of Somalia has a single star on a light blue field. The five points on that star represent the five places where Somalis live: Italian, British and French Somaliland, the Ogaden Desert in Ethiopia, and Kenya. Since 1960, Somalia's boundaries have only encompassed the first two communities; it would probably take a war to get the other three.

25. The full story of Lumumba's overthrow wasn't revealed until forty years later; most of the details posted here came from http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/correspondent/974745.stm. Lumumba became a martyr among leftists, because he was only 35 years old, and because the United States apparently ordered his assassination. A CIA agent showed up in Leopoldville with a tube of poisoned toothpaste, but he never got a chance to plant it in Lumumba's bathroom. The Russians remembered him by building Patrice Lumumba University in Moscow; during the Soviet era roughly 10,000 students went there, nearly three fourths of them from the Third World. It also got a reputation as a training ground for terrorists and revolutionaries, like Cuba's Carlos the Jackal. The school is still in operation today, but since the Soviet Union's collapse it has been renamed the People's Friendship University of Russia (PFU), and now the students are mostly Russian; the only foreigners are those who can pay with the cash modern Russia needs so badly.

26. Congolese soldiers of all factions usually ran away if they thought they were losing a battle, because even in the mid-twentieth century, some tribes in the region practiced ritual cannibalism, eating the heart of a slain enemy to gain his strength. Nobody wanted to fight to the end if it meant becoming dinner! One CIA pilot was reportedly captured, killed and eaten after his plane was shot down.

27. After his dismissal, Tshombe fled to Spain. The Congo sentenced him to death in absentia, and in 1967 he was hijacked in his private plane and taken to Algeria. He died there two years later, while awaiting extradition.

28. As you can see, Hertzog was one of the founders of apartheid, but he was more honest about it than other white politicians. He admitted that the only reason for separating the races was the fear that someday the whites would be overwhelmed by the country's black majority: "The European is severe and hard on the Native because he is afraid of him. It is the old instinct of self-preservation. And the immediate outcome of this is that so little has been done in the direction of helping the Native to advance."

29. Appropriately, the correct pronunciation is "apart-hate."

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Africa

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|