| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Latin America and the Caribbean

Chapter 6: Contemporary Latin America, Part II

1959 to 2014

This chapter is divided into seven parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| One More Overview | |

| Cuba: The Revolution Continues | |

| Venezuela's Democratic Interlude | |

| Brazil: The Death of the Middle Republic | |

| Weak Radicals and the Argentine Revolution | |

| Colombia: The National Front |

Part II

Part III

| Paraguay: The Stronato | |

| Brazil: The Military Republic | |

| Bolivia: The Banzerato | |

| Red Star In the Caribbean | |

| The Perón Sequel and the "Dirty War" | |

| Panama: The Canal Becomes Truly Panamanian | |

| The Dominican Republic: The Balaguer Era | |

| The Guianas/Guyanas: South America’s Neglected Corner | |

Part IV

| The Salvadoran Civil War | |

| Belize: A Nation Under Construction | |

| The Guatemalan Civil War | |

| The Southernmost War | |

| Among the Islands | |

| Colombia: Land of Drug Lords and Guerrillas | |

| The Pinochet Dictatorship | |

| Peru: The Disastrous 1980s |

Part V

| The Switzerland of Central America | |

| Nicaragua: The Contra War | |

| Ecuador After the Juntas | |

| Chasing Noriega | |

| Argentina’s New Democracy | |

| Hugo's Night in the Museum | |

| Democracy Comes to Bolivia (at Last) | |

| Haiti: Beggar of the Americas | |

| Peru: The Fujimori Decade |

Part VI

| Brazil: The New Republic | |

| Cuba's "Special Period" | |

| Chileans Put Their Past Behind Them | |

| Colombia’s Fifty-Year War | |

| Uruguay Veers from the Right to the Left | |

| Daniel Ortega Returns | |

| Ecuador: Dollarization and a Lurch to the Left | |

| The Chavez Administration, Both Comedy and Tragedy |

Part VII

| Argentina: The New Millennium Crisis, and the Kirchner Partnership | |

| Guatemala Since the Peace Accords | |

| Can Paraguay Kick the Dictator Habit? | |

| Honduras: The Zelaya Affair | |

| Peru in the Twenty-First Century | |

| Bolivia: The Evo Morales Era | |

| The Mexican Drug War | |

| Puerto Rico: The Future 51st State? | |

| Conclusion |

Che!

Immediately after the revolution’s triumph, Raúl Castro and Ernesto "Che" Guevara were given the job of eliminating the revolution’s enemies who were still in Cuba. Raúl became the Minister of Armed Forces; he held that position for the next forty-nine years (1959-2008), and got started by ordering the shooting of at least 100 soldiers who had served under Batista. For five months in 1959, Che Guevara commanded La Cabaña, the huge eighteenth-century fortress in Havana where he imprisoned, tried and executed those considered to be traitors, informants, war criminals, and members of Batista’s secret police. Estimates of the number of victims killed at La Cabaña range from 55 to 105; most of them were probably guilty, but still the military tribunals, pardons and firing squads were conducted without respect for due process, not a good sign. Since Che was the doctor of the revolution before 1959, it is obvious that he had become a hardened man by now; he was a true believer in communism and if the only way to defend it was through the use of summary/collective trials and the death penalty, no argument could persuade him to do otherwise. While the international community was outraged, Che and the Castro brothers claimed they were just carrying out the people’s will.(25)

After the La Cabaña assignment, Che Guevara served as head of the Ministry of Industry and head of the Cuban Bank. But a desk job wasn’t for him, even when it was a senior post in the government. Consequently, whenever he got the chance, he took long trips abroad, acting as an ambassador of Cuba’s revolution (see footnote #12). By 1965, he had even gotten tired of this, so he went abroad again, to start his own communist revolution somewhere. He didn’t announce where he was going, but simply disappeared, leading to incorrect rumors that he was having trouble getting along with Fidel Castro.

The first place that Che chose for a new revolution was the Congo. Here the Western nations weren’t very popular, and political chaos ruled -- an environment where communists usually thrived. Che’s Congo adventure is covered in Chapter 8 of my African history. It was a miserable failure. The faction he chose to support in the Congo civil war was not ready to make the jump from tribalism to communism, and he could not work well with the faction’s leader, Laurent Désiré Kabila. Within a few months he decided he wasn’t going to succeed in Africa, and escaped before his enemies could kill him.

Back in Cuba, Che got the idea to start a communist revolution in his native Argentina, but Fidel and the others persuaded him to try Bolivia instead. After all, Bolivia had experienced a revolution in 1952, which was so successful that even the United States endorsed it. The Bolivian National Revolution had petered out by the end of the 1950s, but because it had plowed the ground of Bolivian society, it shouldn’t be difficult to start another one, right? Accordingly, Che traveled to Argentina and sneaked into Bolivia from there. Because he knew others were watching him, like the CIA, he resorted to a disguise; he shaved off his beard and part of the hair on top of his head to make it look like he had male pattern baldness, dyed the rest of his hair grey, and passed himself off as a middle-aged businessman from Uruguay.

Che got off to a better start in Bolivia than he had in the Congo. In the forests of eastern Bolivia, he organized a small guerrilla force of Cubans and Bolivians called Ñancahuazú Guerrilla, or Ejército de Liberación Nacional de Bolivia (ELN). Working their way toward the mountains, they scored two successful ambushes of Bolivian army patrols in early 1967, but failed to win over the Bolivian opposition groups that already existed, including the local Communist Party; some of them tipped off the authorities about the ELN’s movements. Even communication was difficult, because the guerrillas had learned the Quechua language beforehand, in order to talk with Bolivian peasants, but the lowland peasants really speak a Tupi-Guarani language. When Che realized that the locals were turning against him, he wrote in his diary, "Talking to these peasants is like taking to statues. They do not give us any help. Worse still, many of them are turning into informants." As a result, the next two ambushes were carried out by the army, and most of the guerrillas were killed.

By October Che had twenty of his original fifty men left, was almost out of supplies, and the Bolivian government posted a reward of $4,000 (definitely a lot of money for poor Bolivians) for information leading to his capture. Directed by Félix Rodríguez, a Cuban exile turned CIA agent, and a local informant, 1,800 soldiers surrounded the ravine where the remaining guerrillas were camped, and they wounded and captured Che. They took him to the village of La Higuera and interrogated him, but because his guerrilla force had been eliminated, he had little information to give, so on orders from Bolivian President René Barrientos, Che was shot the next day (October 9, 1967), and buried in the nearby town of Vallegrande.(26)

In 1997 Che’s remains were dug up, identified, and sent to Cuba for reburial. Still, because of his martyrdom, the present-day residents of La Higuera and Vallegrande venerate him, sell souvenirs featuring his picture (see below), and call him "St. Ernesto," as if they expect him to be canonized someday. And this isn’t the only place where he has become a pop-culture hero.

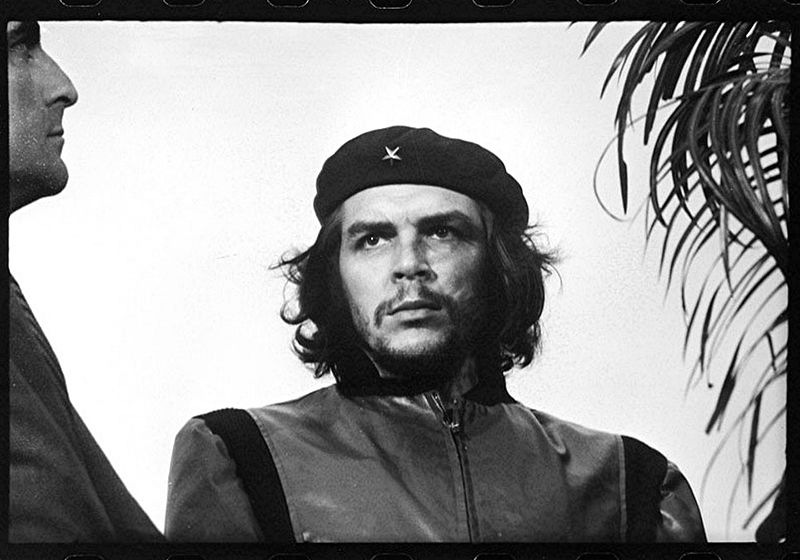

Here is Che Guevara’s most famous photograph, Guerrillero Heroico, taken in March 1960. Because many people think he looks cool, his face has been cropped from this image, and can be found on T-shirts and posters around the world. It is ironic that capitalists are making money off this famous enemy of capitalism, and that those who wear his shirt do not realize he was one of the greatest losers of the twentieth century. Indeed, it’s a safe bet that the less somebody knows about Che, the more likely they will be attracted to his shirts and posters. My favorite political humor website, The People’s Cube, has an online store called Che-Mart, which offers T-shirts and buttons with pictures that make fun of Che’s popularity, like this one:

Speaking of silly ads, here is Lydia Guevara, Che’s granddaughter (1985-). In 2009 the group PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) found out she was a vegetarian, and got her to pose for a picture wearing some strategically placed carrots and a revolutionary beret, with the caption "Join the Vegetarian Revolution." Who jumped the shark here, the Communists or the environmentalists?

Democracy Breaks Down in Chile

Chile established a government in 1925 (the "Presidential Republic") that lasted nearly half a century, so it was still going strong as the period covered by this chapter began. However, its failure and the awful aftermath would show the world that nobody’s perfect. For two whole decades, In the 1970s and 80s, Chile had one of the worst-behaved governments in Latin America, after having one of the best-behaved for a century and a half.

Jorge Alessandri Rodríguez, the president who served from 1958 to 1964, managed to cut the inflation rate from 39 percent in 1959 to 8 percent in 1961, no small achievement in a part of the world where high inflation is so common. But a slump in copper prices meant Chile’s profits would not grow, and an attempt to persuade the mining companies to do a larger share of their refining within Chile’s borders was denounced by the leftist parties as not being the "nationalization" of the companies they had in mind. And with most copper, nitrate and iodine production in foreign hands, this mattered. In 1960 the three largest Chilean mines, owned by the Anaconda and Kennecott companies, generated 11 percent of the GNP, 50 percent of the country’s exports, and 20 percent of the government’s revenue. Of course most of what the companies earned from those mines did not stay in Chile. In 1962 Alessandri addressed the problem of land inequality by passing a law calling for the expropriation of underused land from large estates. Conservatives fiercely opposed this act, but again leftists said it was no good enough for them.

The two chief candidates that ran against Alessandri in 1958 -- Eduardo Frei Montalva for the Christian Democrats and Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens of the Marxists -- both ran again in the 1964 election. Conservative and moderate political groups grew very concerned when they saw the conservative candidate trailing in third place, behind the other two. This was the third time Allende had run for president, and he had gotten more votes with each election. To keep the voters from putting Allende over the top, everybody who opposed Allende rallied behind Frei, the safe alternative, so Frei won by 56%-39%.

The strong majority from the election convinced the Christian Democrats that they had a mandate to put their plan into action. They called it a "Revolution in Liberty," and announced their goal was to find a third way to prosperity and social justice, avoiding the worst excesses of both free-market capitalism and communism. This also meant income redistribution, state intervention in the economy, and land and tax reforms would be carried out to a further degree than Chile had ever tried before. What they did not count on was rivalry between the political center and the left. While both factions agreed that the power and wealth of the great landowners needed to be reduced to a more manageable level, neither could get it done by itself, nor were they willing to work together. Consequently Frei found the reform programs he launched running into increasing opposition; on the one hand conservatives said he was doing too much; on the other hand leftists said Frei wasn’t doing enough, while calling the Christian Democrats tools of US imperialism and the Vatican (this was before Liberation Theology got popular, remember). At the end of his term, Frei could say he had been successful by the standards of Chilean politics, but he had not fully met his party's ambitious goals.

As the 1970 election approached, a mood of crisis spread across Chile. Peasants and workers were making more money, but the economy could not provide the goods and services they were now demanding. On the political front, the Christian Democrats split into center-right and center-left subfactions, while the radicals, Socialists and Communists were still united in a coalition called Popular Unity, led by Salvador Allende. At one point Allende said that the goal of his government would be to "change the constitution by constitutional means," so many thought that a leftist victory would end the parliamentary system as they knew it (they were right, but did not realize how long the after-effects would last). To complete the picture, the right nominated former president Alessandri again, and refused to cooperate with the Christian Democratic candidate, Radomiro Tomic, because he was too liberal for them. When the votes were in, Allende and Popular Unity got 36 percent, Alessandri got 35 percent, and Tomic got 28 percent. Because nobody had a majority, the three-way race was thrown to Congress, which after weeks of wheeling and dealing, chose Allende.

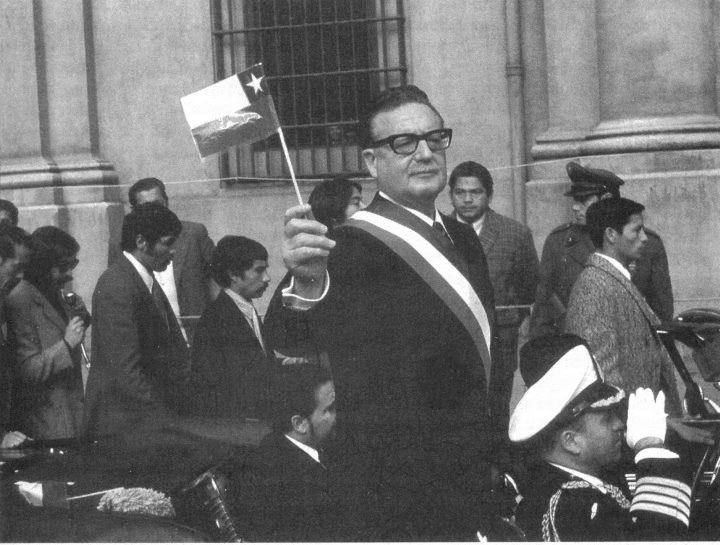

Salvador Allende. To any Texans reading this, I don’t know why the flags of Chile and Texas look alike!

With this being the Cold War era, Allende’s election sent shock waves to the United States. Now it looked like Chile would become the second Communist nation in Latin America, after Cuba. Washington and various right-wing groups tried to persuade Congress to choose Alessandri instead of Allende, or coax the military into staging a coup d'état; all efforts failed. One military faction attempted to kidnap the army commander in chief, General René Schneider Chereau, and frame the deed to make it look like Allende did it. Instead the general pulled a gun to defend himself, and was fatally shot; his assassination was the first major political killing in Chile since Diego Portales in 1837. The plot also backfired by leaving the rest of the troops so shocked that they would allow Allende to take office without any more trouble.

Allende’s presidency lasted three years (1970-73); the first year went great, but the other two were disasters. During the first year, Chile experienced 12% industrial growth, and reduced inflation and unemployment. Popular Unity taught that the country’s main enemies were "parasitic capitalists," both foreign and domestic, so once they were in power, their plan was to socialize the economy. This meant breaking up the great landed estates, wage increases, and price controls. Most important of all was nationalizing the assets of the big US mining companies, and this was accomplished with ease because most Chileans were in favor of it.

Next, Popular Unity nationalized the banks and other mineral resources besides copper. Here they ran into opposition, for despite winning the election, the leftists never enjoyed a majority of Chilean support, either from the public or from the government outside the executive branch. In Congress, they could only get legislation passed by partnering with the Christian Democrats, something they preferred not to do. The judiciary and the treasury opposed the leftist program completely; so did the military, the Catholic Church, and most of the news media and radio stations. Even the leftists could not stay united; Popular Unity split into moderate and radical factions over the question of whether Allende was doing enough.

While the various factions debated, the Chilean economy came undone because the growth surge of the first year was unsustainable and now demand outstripped supply. With the land in less experienced hands after it was taken from the major landholders, food production decreased. A chain of bad events followed: the economy shrank in more than one sector, credit dried up, deficit spending snowballed, new investments and foreign money became scarce, inflation shot out of control, shortages appeared in price-controlled commodities like rice, beans, sugar, and flour, and a black market sprang up to meet the need caused by the shortages. Chile could not try the austerity measures used by other financially strapped nations in the modern world, such as raising taxes, cutting spending or borrowing more money from abroad; Congress and the voters would not stand for it.

Meanwhile, the United States was frustrated because it was bogged down in a Southeast Asian war that was going nowhere. This made Washington determined to stop the spread of communism wherever it could. In the case of Chile, the appearance of Cuban arms and KGB advisors from the Soviet Union confirmed Washington’s worst fears. Although the Nixon administration wasn’t openly hostile toward the Chilean government, it wasn’t friendly either, and made Allende’s job harder in little ways, like ending financial assistance and blocking loans. We don’t know for sure if the CIA was plotting to oust Allende before 1973, but it is worth noting that US military aid to Chile increased during this time, and we saw above that the military was one institution that did not like the government’s activities. Officers keeping track of where the money was coming from might have taken this as a hint.

The opposition held hope that if it won two thirds of the seats in the March 1973 Congressional elections, it would have enough votes to impeach Allende. That didn’t happen, and with the economy in a tailspin, the nation saw mass demonstrations, strikes in various professions, violence between government supporters and opponents, and widespread rural unrest. There was a failed military coup in June 1973, and both the economy and the government were paralyzed for the next three months.

The military acted again on September 11, 1973, and this time the coup was successful. What happened to Allende was never clear; the armed forces reported that Allende shot himself, while liberals to this day insist that soldiers shot him. The leader of the coup, General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte, installed a junta in place of the previous government, with himself in charge of it, and immediately began reversing Allende’s policies. In Chile’s three-way political struggle, the rIght had proved stronger and more determined, than either the middle (the Christian Democrats) or the left.

A scene from the 1973 Chilean coup; tanks and soldiers take up positions around the presidential palace, before bombarding it.

Peru: The Revolution from Above

Peru had a stratified, segregated society as the period covered by this chapter began. The whites (who ran the country, of course), were a small minority in Lima; most of the others living on the coast were Mestizo, while the population in the highland and Amazon regions came overwhelmingly from native tribes. This gave Peru a schizophrenic identity, because Peruvians wanted to express both their Spanish and their Inca heritage. Thus, you can see a statue of Francisco Pizarro, the conqueror of the Incas and the founder of Lima, among the government buildings in the capital. However, Pizarro is also one of history’s villains, so Peruvians matched that statue by raising a 115-foot-high statue of Pachacuti, the conquering Inca king (see Chapter 1), near Cuzco. Since the Lima elite discriminated against nonwhites, the vast majority of Peruvians were forced to live in poverty, though the land is rich in resources.(27) Antonio Raimondi, an Italian naturalist who visited Peru in the 1850s, described the nation as "a beggar sitting on a gold bench." Since the 1960s there has been a demographic shift, as job-seeking Mestizos and Indians have moved to Lima, forming huge shantytown suburbs and blurring the ethnic differences that once existed.

The 1962 presidential election was a race between three familiar faces: Fernando Belaúnde Terry, the founder of the Popular Action Party (AP); Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA); and Manuel Odría, the dictator who had ruled from 1948 to 1956. The results were extremely close; Haya de la Torre ended up ahead of Belaúnde by less than 14,000 votes, and nobody got one third of the total vote, which meant that Congress was now required by the constitution to pick the next president. Before this could happen, Haya de la Torre made a deal with Odría. He knew that because APRA and the military were old enemies, the military would not let him win, so his next plan was to make Odría president of a coalition government that included APRA. But the military did not want Haya de la Torre in the government even if he shared power with someone else, so they staged a coup and installed a junta that would rule until new elections could be arranged. Those elections took place in 1963, and this time, by making an alliance with the Christian Democrats, Belaúnde won by a five percent margin.

Belaúnde had gotten elected because he ran a populist campaign; e.g., he would go to villages in the Andes, tell the natives that if they worked as hard as their Inca ancestors they could be glorious again, and declared that peasants without land had the right to own it. However, this was the 1960s, and as in other parts of Latin America, communist guerrilla movements sprang up, inspired by the success of the Cuban Revolution. Belaúnde tried to head them off with three projects: an agrarian reform law, a project to colonize the tree-covered eastern slopes of the Andes (the montaña), and a highway following the edge of the jungle, running all the way from the northern to the southern border of the country. But many of the communists were former Apristas who did not like seeing how APRA had gone from being a left-wing to a right-wing party, and Belaúnde’s proposals were not radical enough for them, either.

As a former architect and urban planner, Belaúnde believed that best solutions for problems were technical ones. He liked to compare how well-managed the Inca Empire was, with its excellent roads and irrigation system, and told Peruvians they could do that again: "The Inca society had many defects, but in those days the Indians were not hungry. The Spanish conquistadors failed to conserve this achievement. I will try to re-establish it." For the economy, he wanted to build it up with improved irrigation, transportation, housing and education.(28) The communists, by contrast, wanted to tear down the existing society, instead of making it better. When they formed the first guerrilla movement in Peru, the Revolutionary Left Movement (MIR), Belaúnde (with the support of APRA) ordered the armed forces to crush it, and they did so by 1965. A potentially more serious threat arose when the peasants, not satisfied with the agrarian reform law (it had so many loopholes in it that not much land actually changed hands), decided to do it themselves. From 1963 onward, invading peasants seized land in the central and southern highlands. In the past they only took land that wasn’t being used by the current owners, but now they occupied cultivated land as well, justifying it by saying they had paid for it with several generations of unpaid or poorly paid labor. Militant peasant unions also appeared, and workers in Lima and Callao launched strikes.

The armed forces were called out to recover the land taken by the peasants, and they gave the peasants the same treatment they gave to the guerrillas. One estimate stated that the campaign against the peasants left 8,000 dead, 3,500 imprisoned, and 19,000 homeless, with 14,000 hectares of land burned in the process. By 1966 the peasant invasion was over, but economic problems kept Belaúnde from finishing his term. The worst of these was an old dispute with the International Petroleum Company (IPC), a subsidiary of the US-based Standard Oil, over the La Brea y Pariñas oilfields in northern Peru. The Peruvian government claimed that the IPC owed almost $700 million in unpaid taxes and fines, for drilling and pumping oil from the fields over the past forty years. When the two sides signed an agreement to settle the dispute, the IPC returned the nearly exhausted oilfields in exchange for a cancellation of the payments owed; the IPC also received a concession to drill in the Amazon region and was allowed to keep a refinery. Everyone with nationalist feelings, from the armed forces to Catholic clergymen, denounced the agreement. The military, under General Juan Velasco Alvarado, decided the government was incapable of fixing the country’s problems and had sold out national interests, so in October 1968 it seized the presidential palace, exiled Belaúnde, and installed a junta that began an unexpected and unprecedented series of reforms.

Those reforms were unexpected because traditionally in Latin American society, the military sided with the upper class. From Cuba, Fidel Castro said that what the military did in Peru was as startling "as if a fire had started in the firehouse."(29) But in Peru most of the officers, including General Velasco himself, came from middle and lower-class backgrounds, and while fighting the guerrillas, they came to believe that no victory would be permanent unless something was done to pull the masses out of poverty and develop the country’s infrastructure. Most amazing of all, much of the reform program resembled the 1931 program of APRA, which the army had once opposed.

The first thing the Velasco junta did was nationalize all of the IPC’s assets in Peru, including the refinery mentioned above. Then it broke up the large plantations along the coast, which had been off-limits in previous land reform programs. By 1975 half of all arable land had been transferred to more than 350,000 families, or one fourth of the rural population. Item number three on the agenda was gaining control over foreign-dominated enterprises; at the time of the 1968 coup, three-quarters of mining, one-half of manufacturing, two-thirds of the commercial banking system, and one-third of the fishing industry were under direct foreign control. Finally, Peru displayed a more assertive foreign policy; in 1969 it became one of the charter members of the Andean Pact, along with Bolivia, Colombia and Ecuador; in the 1970s it set forth a claim to everything in the Pacific within 200 miles of its shores.(30)

The first phase of the military revolution ended in 1975 with an economic crisis, brought on by rising oil prices, falling prices for exported Peruvian commodities like copper, and unmanageable debts (Velasco had borrowed heavily from foreign banks to pay for the reforms). In addition, because it was a "revolution from above," the junta accepted little input from below; instead Velasco acted more and more like an autocratic dictator. The result was an overly bureaucratic, authoritarian state, and the military commanders decided that Velasco, who was now terminally ill, could no longer carry out his duties; on August 29, 1975 they deposed him, and his prime minister, General Francisco Morales Bermúdez Cerrutti, became the new Number One.

Bermúdez was a more conservative leader than Velasco. Instead of continuing the revolution, he imposed a strict austerity program to stop the recent inflation surge. This meant sharp reductions in government investments in state enterprises, steep increases in consumer prices, a 44 percent devaluation of the sol, and the end of the agrarian reform program. Though he threw in a wage increase of 10 to 14 percent, public opinion turned against his administration, and military rule in general, so Bermúdez also prepared the country for a return to democracy.

The main goals Bermúdez wanted for the transition were that it would proceed smoothly without strife, and that when it took over, the civilian regime would continue his conservative policies. He got his wishes on both. A constituent assembly was elected in 1978 to write a new constitution; they ended up producing a document that looked a lot like the 1933 constitution, except that it also gave illiterates the right to vote.(31) When presidential elections were held in 1980, former president Belaúnde, who looked like a martyr after his ouster in 1968, was re-elected to a five-year term.

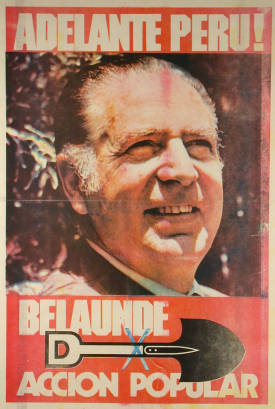

A 1980 campaign poster for Belaúnde. From Wikimedia Commons.

Mexico: The PRI Corporate State

This chapter won’t have as much to say about Mexico as the previous chapters of this work did, because recent Mexican history hasn’t been as violent. First of all, Mexico was blessed in that it got its social revolution over with so early, in the second and third decades of the twentieth century. Second, its big Gringo neighbor to the north has acted as a stabilizing influence, because a stable, prosperous Mexico is in the best interests of the United States. This makes Mexico a special case, as Latin American nations go. Even so, changes continued to take place under the surface, while those in power actively tried to prevent them. And the current drug war means that present-day Mexico is hardly a quiet place.

We saw in Chapter 5 that after the Mexican Revolution ended, the survivors set up a one-party democracy, run by the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). The PRI started out with some genuinely radical social policies, especially under President Lázaro Cárdenas, but under the first generation of PRI rule, the revolutionaries transformed themselves into reactionaries. Because it was almost impossible to remove a PRI politician who wasn’t doing his job, they steadily became more corrupt, less efficient, less tolerant of dissent, and more self-seeking. Each PRI president was elected, served out his six-year term, and was predictably succeeded by another PRI president. Because the political machine worked so smoothly, for most of the presidents in the half-century after Cárdenas, we’ll only mention their names and the dates they were in office:

- Manuel Ávila Camacho, 1940-46

- Miguel Alemán Valdés, 1946-52

- Adolfo Ruiz Cortines, 1952-58

- Adolfo López Mateos, 1958-64

- Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, 1964-70

- Luis Echeverría Alvarez, 1970-76

- José López Portillo, 1976-82

- Miguel de la Madrid Hurtado, 1982-88

- Increased enrollment in primary schools, meaning the population had become more educated.

- High tariffs on imported goods, which encouraged manufacturing at home.

- Public investment in agriculture, energy, and transportation.

Third, the improved standard of living allowed demographics to take off. Mexico’s population ballooned from 13.6 million in 1900, to 38.7 million in 1960, and to 120.8 million in 2012.(32) In terms of population, this made Mexico the third largest country in the western hemisphere (after the United States and Brazil), and the largest Spanish-speaking country in the world. In the 1960s, the annual population growth rate was a wild 3.5%; since then it has leveled off to 0.99 percent.

Fourth, as demand for Mexico’s oil reserves increased, the economy became dependent upon oil production to make ends meet. This meant that in the 1970s and 80s, rising and falling oil prices determined whether Mexico would experience feast or famine, just as they did for Venezuela and Ecuador. Fortunately, Mexico diversified its industries after that, to reduce oil’s critical importance.

By the 1960s, the PRI was doing what it could to make elections go in its favor, and gaining indirect control over corporations. Because of that, the government could not be called a true democracy, but because it was still open to influences from below, it wasn’t a dictatorship, either. Still, the system left many dissatisfied, especially those who felt the PRI should go back to land reform, social equality and keeping foreign companies out of the country.

Mexico City hosted the Summer Olympic Games in October 1968, and Mexico understandably wanted to promote a good image of itself to the world at that time. But 1968 was also a year that saw widespread student protests against "the establishment" in many nations, and Mexico was no exception. When student protests erupted in the Tlatelolco neighborhood of Mexico City, troops shot an estimated 400 protesters dead (October 2, 1968). In the minds of many Mexicans, the PRI lost its right to rule with the Tlatelolco Massacre. From then on the party depended increasingly on fraud to win elections, as rival parties appeared; the most important new parties were the pro-business National Action Party (PAN) and the left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD).

The main reason why the PRI remained comfortably in control after this was because the economy did well for a few more years. But inflation meant the peso had been considerably devalued at home, while the official exchange rate remained at 12.5 pesos to 1 US dollar, what it had been since 1954. Mexican exports now became too expensive on the world market, and two devaluations of the peso in 1976 were not enough to correct this. The discovery that the oil reserves in the Gulf of Mexico were much larger than previously thought saved the day for then-president José López Portillo; he was able to pay old bills, but the new windfall caused the rate of inflation to soar, and it also encouraged more spending and borrowing. The spend-and-borrow game had to stop in 1982, when US interest rates peaked at more than 20 percent. Inflation reached 100 percent that year, the foreign debt reached $85.5 billion, and Mexico became the first of several Latin American nations in the late 20th/early 21st century to suffer from a debt crisis.(33)

Mexico suspended interest payments on its debt, so when Miguel de la Madrid became president a few months later, he had his work cut out for him. To refinance the debt, he accepted a strong austerity package from the IMF that required price hikes across the board, the lifting of price controls and subsidies on consumer items, and another devaluing of the peso; the latter raised the cost of imports and reduced real wages. And because these measures were not going to be popular, the government tried blaming its problems on the corruption of the previous administration. Although De la Madrid got inflation under control by 1987, for the rest of the twentieth century, Mexicans expected a recession and devaluation at the end of each president’s term.

Another crisis was not caused by economics, but by the magnitude 8.1 earthquake that struck central Mexico on September 19, 1985. The quake’s epicenter was in the Pacific, about 350 miles from Mexico City. Nevertheless, because of the strength of the tremor, and because Mexico City is built on the unsteady foundation of a dry lake bed, the capital was severely damaged. The number of deaths from the earthquake is disputed, with estimates ranging from 10,000 to 40,000. The public was already mad at the government because of the economy, and the poor job it did handling earthquake relief efforts made them angrier. For the first time in fifty years, the PRI began to face serious electoral challenges (e.g., this was the first time a state governor from another party was elected).

The ruling party barely held onto its monopoly with the 1988 election. The PRI candidate, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, was a Harvard-educated graduate like De la Madrid, and he came out ahead after a mysterious computer failure interrupted the vote counting (see Chapter 5, footnote #55). The opposition parties all claimed Salinas won through "electoral alchemy," and staged street demonstrations to protest his inauguration.

During the Salinas presidency, drug trafficking grew so rapidly that many thought Salinas or some other senior PRI members had their hand in the drug trade, but this was never proven. For the legal economy, Salinas took steps to privatize state-run industries, and in 1990 concluded a plan with US banks to service Mexico’s debt on more favorable terms.(34) His biggest success was the negotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and US President George H. W. Bush. This agreement eliminated all tariffs between the three nations, creating a common market in North America. Mexico could grow crops and manufacture goods at a much lower cost than the other two nations could, so Mexico got the best part of the deal; trade with the US and Canada tripled afterwards, and some foreign corporations built factories south of the border to take advantage of lower prices.

At the end of his term in 1994, Salinas spent nearly all of Mexico’s foreign-exchange cash reserves, in the form of bonds, to raise the value of the peso. Instead it caused another devaluation and a recession when Mexico could not sell them all; this slump is now called the "December Mistake."

The official PRI candidate to succeed Salinas, Luis Donaldo Colosio, was assassinated at a campaign stop in Tijuana. His replacement was the ex-minister of Education, Ernesto Zedillo Ponce de León. Because of the assassination, and because he was elected with less than 50 percent of the vote, Zedillo got the message that it was time for political reform. He established the Federal Electoral Institute, an organization run by ordinary citizens (not party officials) to oversee elections and make sure they are conducted legally and impartially; the new system allowed several non-PRI mayors and state governors to get elected. That, combined with the privatization program launched by Salinas, undermined the PRI-built corporate state during Zedillo’s term (1994-2000). For the recession he inherited from Salinas, he got a bailout from the United States, in the form of $50 billion in loan guarantees. Fortunately this stabilized the peso, and because the economy enjoyed good years from 1996 onward, Mexico was able to pay back its US Treasury loans in 1997, ahead of schedule.

Another problem which had been handed down to Zedillo was a rebellion in the southern state of Chiapas. We saw previously that Chiapas was a disputed territory when Mexico and Guatemala went their separate ways, until General Santa Anna annexed it for Mexico (Chapter 4, footnote #4). Chiapas had only prospered when the Maya civilization had cities there; more recently, its population was still mostly Maya and it was a neglected and oppressed region, the poorest state in all Mexico. Because the state was off the beaten path, censuses have shown as much as 37 percent of the population speaking native languages only. The 1917 constitution called for land reform all over the country, but somehow Chiapas had been forgotten, so most local farmers only owned small plots of land. What outraged them now was the signing of NAFTA; they believed that the agreement would put them out of business, by driving the prices of coffee and corn so low that only large landowners could continue to turn a profit.

On January 1, 1994, the day NAFTA went into effect, armed rebels, calling themselves the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN), boiled out of the Lacandon jungle.(35) They occupied seven highland towns, where in the tradition of other revolutions, they ransacked government offices, destroyed land deeds, and freed 179 prisoners. The government responded with troops, tanks and aircraft, and after 12 days of gun battles, the EZLN was driven into the mountains.

However, the government chose to negotiate with the rebels after that, not destroy them; perhaps it felt the people of Chiapas had a genuine grievance. Over the course of 1995, meetings were held at a secret location in the jungle with the EZLN leader, who was only known by his nom de guerre, Subcomandante Marcos. A tentative agreement was reached in 1996, which promised to redistribute illegal large landholdings to poor peasants, begin a public works program, and prohibit discrimination against the Indians. In the meantime the locals were allowed to organize their villages into thirty-two autonomous municipalities, which they run by themselves. While the municipalities and their residents are still poor, you can say they are better off because they have much more control over their lives.

Since the twenty-first century began, the situation in Chiapas has been gridlocked. Because both sides are armed, there have been violent incidents from time to time, and so far the government has not complied with the terms of the 1996 agreement. In 2001 the Zapatistas marched to Mexico City and let Congress know they still had unmet demands, but instead Congress passed an indigenous rights law that was quite different from the anti-discrimination law in the agreement, and not as strong.

By then the PRI was no longer in power, and the more conservative National Action Party (PAN) just ignored the EZLN. Vicente Fox had campaigned on two promises -- he would solve the conflict with the Zapatistas within 15 minutes, and give the country an economic growth rate of 7% -- but his actions after becoming president showed he only considered the second promise very important. Both the PRI and PAN since 2000 have put Chiapas on the back burner, treating the EZLN like a local rival party.

Meet the Duvaliers

For those of you who read Chapter 3, if you thought King Henri Christophe was a hoot, wait until you hear about François "Papa Doc" Duvalier. His rise to the presidency marked the beginning of the worst period in Haitian history since independence; it lasted for two generations.

The 1957 election between François Duvalier and Louis Déjoie may have been the quietest, most honest election Haiti ever saw. Running on a populist, black nationalist platform, Duvalier won with three quarters of the vote. Because he had been a doctor before going into politics, he was also known by the nickname "Papa Doc." The first thing he did as president was to put forth his own constitution, Haiti’s twentieth constitution so far. In 1958 the army tried to oust him in a coup, and Duvalier responded by creating two new armed forces to counterbalance the army’s power. The first was the already existing Presidential Guard, which he turned into an elite corps loyal to him alone. The second was a secret police, the dreaded Tonton Macoute (Creole for "Bogeyman"), which wasn’t as well armed as the army or the Presidential Guard, but was enlarged until by 1961, it had twice as many men as the army. To get foreign aid from the United States, Duvalier announced he was anti-Communist, and when the aid money arrived, he kept most of it for himself.

François "Papa Doc" Duvalier.

In a nationalist move, Duvalier expelled foreign-born bishops from Haiti, causing the Catholic Church to excommunicate him. This didn’t faze him; in place of Catholicism, Duvalier promoted the voodoo religion and a cult of personality. He announced he was a voodoo priest, and the physical manifestation of Baron Samedi ("Lord Saturday"), the voodoo spirit of death. One propaganda poster showed Duvalier sitting while Jesus stood beside him, with His hand on Papa Doc’s shoulder, indicating that God and Jesus were on his side. Later he rewrote the Lord’s Prayer to be about him, and made the people recite it:

"Our Doc, who art in the National Palace for life, hallowed by Thy name by present and future generations. Thy will be done in Port-au-Prince as it is in the provinces. Give us this day our new Haiti and forgive not the trespasses of those anti-patriots who daily spit upon our country..."

So far Papa Doc does not sound too different from the Dominican Republic’s tyrant, Rafael Trujillo. But on May 24, 1959, he had a heart attack, probably caused by an insulin overdose (he suffered from both diabetes and heart disease at the time). The heart attack put him in a coma for nine hours, and probably caused brain damage, because after he regained consciousness, he wasn’t just a dictator; he was now a crazy dictator. While he was incapacitated, the head of the Tonton Macoute, Clement Barbot, was the acting president, so Duvalier accused Barbot of trying to replace him and had Barbot arrested. While Barbot may have been loyal before this incident, his imprisonment turned him into a rebel, for after Duvalier released him in April 1963, he plotted to kidnap the president’s children. The plot failed, and when Barbot could not be found, Papa Doc heard a rumor that Barbot had turned himself into a large black dog. This caused him to order every black dog in Haiti killed, until Barbot was captured and executed in July.(36)

The Haitian constitution, like the present-day Mexican constitution, allowed the president to have just one six-year term in office. Nevertheless, Duvalier decided to run for re-election in 1961, though he had two years left in his term. Even by the standards of Latin American dictatorships, Duvalier went out of his way to stuff the ballot box. He was the only candidate allowed to run, and the vote total announced was Duvalier = 1,320,748, Others = 0. Nobody doubted the election had been rigged, and on May 13, 1961, The New York Times commented that "Latin America has witnessed many fraudulent elections -- but none will have been more outrageous than the one which has just taken place in Haiti."(37) Haiti’s relations with the United States and the Dominican Republic deteriorated after that, because neither could believe the election results, and the United States realized that the aid money it had sent wasn’t going to strengthen the country. In 1964 Duvalier decided he had violated his own constitution enough, and wrote another one that legalized his activities and declared him president-for-life, the eighth in Haitian history to this point.

The rest of Duvalier’s reign was somewhat calmer; a war scare with the Dominican Republic was averted, the United States let up pressure when it decided Duvalier was better than the Communists in Cuba, and the country survived several damaging hurricanes that swept across it. For the Haitian people, however, it was a reign of terror; an estimated 30,000 Haitians were killed while Duvalier was in charge. In a way he oppressed himself, too; after three coup attempts he rarely showed himself outside the presidential palace. In January 1971, he sensed his health was failing and ordered the National Assembly to change the constitution so that his son, nineteen-year-old Jean-Claude Duvalier, could succeed him. He did it just in time; three months later Papa Doc died of natural causes. The spells cast by the voodoo priest were not broken by his death; whereas foreigners predicted revolts, there was mourning and orderly behavior at Duvalier’s funeral. He bequeathed a country without a heart or a hope to Jean-Claude Duvalier, henceforth known as "Baby Doc," who now became Haiti’s ninth president-for-life.

The younger Duvalier came to power with considerable goodwill, from both inside and outside Haiti. The Haitian upper class thought it could regain some of its political influence, now that Papa Doc was gone. At the private Catholic school Jean-Claude Duvalier attended, he reportedly wasn’t a very good student, but his teachers gave him passing grades anyway to avoid the wrath of the first family.(38) And because Baby Doc was such a youthful leader, he didn’t find his duties very interesting, so he attended ceremonial functions, lived a playboy lifestyle the rest of the time, and left most of the decision making to his mother, Simone Ovid Duvalier. The United States resumed sending the aid it had suspended a decade earlier. Others, including most of the Haitian people, simply saw Baby Doc as less scary than his father (he wasn’t into voodoo, anyway), and thus hoped he would be an improvement.

Because Baby Doc did not micromanage the government, he was less brutal than Papa Doc, but was more corrupt. His kleptocracy stole hundreds of millions of dollars from government accounts, especially the tobacco monopoly, and put them into as a slush fund for which no balance sheets were kept. Meanwhile, most of his subjects lived in wretched poverty, and suffered from hunger and malnutrition. Under Papa Doc, the per capita income was a mere $70 per year; Haiti had become the poorest country in the western hemisphere.(39) The country and its tourism industry were hit hard by epidemics of swine flu in the late 1970s, and AIDS in the 1980s. Duvalier talked about making reforms in the economy and public health, but because of all the thefts from the national treasury, the public services, already minimal to start with, deteriorated under Baby Doc’s rule.

It was a public relations disaster for Duvalier when he married Michèle Bennett Pasquet, a mulatto divorcée, in 1980. She had a bad background; Papa Doc had jailed her father, Ernest Bennett, for bad debts and shady financial deals,(40) and her first husband, Alix Pasquet, was the son of an officer who had tried to overthrow Papa Doc. Even worse, the idea that the president was marrying someone from the light-skinned mulatto elite made it look like he was abandoning the blacks that his father had worked to make friends with. The wedding is estimated to have cost $5 million, including imported champagne, flowers and fireworks; it was broadcast live on television to make sure the whole impoverished nation saw it. After the ceremony, Michèle ordered her portly husband to go on a diet. From then on, discontent rose steadily in the alienated population.

For the Duvalier regime, the beginning of the end came in March 1983, when Pope John Paul II paid a visit, noted the extreme economic inequality between the elite and the masses, and said, "Something must change here." Open revolt broke out in the fall of 1985, starting in the city of Gonaïves, with riots in the streets and raids on food-distribution warehouses. Jean-Claude tried to defuse tensions by cutting staple food prices by 10 percent, closing independent radio stations, changing personnel in the cabinet, and sending police/army units to restore order, but instead the unrest spread across the country. Two army officers, Lieutenant General Henri Namphy and Colonel Williams Regala, saw the army as the organization that could lead an orderly transition to another form of government, so instead of backing the Duvaliers, they brought the army over to the other side.

By January 1986, the violence in Haiti’s streets got so bad that the outside world could not fail to notice it, and US President Ronald Reagan put pressure on Duvalier to resign and get out of Haiti. Using representatives of the Jamaican government as go-betweens, the US government made arrangements to help the Duvalier family leave, and provided an Air Force plane for their departure, but refused to let them come to the United States. Duvalier accepted at first, then changed his mind and decided to stay, until an increase in violence and a cutoff of US aid convinced him the game was up. On February 7, 1986, Jean-Claude and Michèle Duvalier left on the American plane. Because the United States would not have them, they went to France, though the French government would not grant them asylum status. They ended up staying in France for the next quarter century, continuing their extravagant lifestyle at first, but after their divorce in 1993, Baby Doc lost most of his fortune and was forced to live more modestly.

Honduras Goes From Military to Civilian Rule

The humorist Will Rogers once said that American tourists will first go to London to watch the changing of the guard (at Buckingham Palace), and then they will go to Paris to watch the changing of the government. In his day, the part about Paris would have been true for Honduras, too. We saw in Chapters 4 and 5 how it seemed that Honduras wanted to hold the record for the most coups, and the most military governments.

Still, at the beginning of the period covered by this chapter, it looked like Honduras was outgrowing the caudillo phase that has been so common in the development of Latin American countries. The military had stepped aside to allow a civilian government in 1957, and the Liberal Party won the elections that followed; Dr. Ramón Villeda Morales was elected president. While Villeda served his term, the military began to transform itself into a professional, apolitical institution; for example, the newly created military academy graduated its first class in 1960. But then they suddenly showed that things weren’t changing that quickly; in October 1963, ten days before the next presidential election, conservative officers ousted Villeda in a bloody coup.

The mastermind behind the coup was Colonel Oswaldo Enrique López Arellano, a member of the 1957 junta. He suspended elections for two years, then ran in them, won, and served an official six-year term as president (1965-71). During that time he paid little attention to laws and bureaucratic procedures, and ran several businesses on the side. His administration also saw a brief border war with El Salvador in July 1969, sometimes called the Football War because it happened right after a particularly intense soccer game between the two countries.

When his term ran out, Oswaldo López stepped aside to allow civilian elections, and the winner was Ramón Ernesto Cruz Uclés, who had been a presidential candidate in 1963. Cruz proved unable to manage the government, so after just eighteen months, Oswaldo López staged another coup to reinstall himself. This wasn’t an improvement, though; during the next decade (1972-82) Honduras saw nine military heads of state, all of them corrupt and not very competent. The second time around, Oswaldo López tried a more progressive policy that included land reform, but in 1975 allegations surfaced that he had taken a $1.25 million bribe from the United Brands Company (formerly the United Fruit Company), and he was ousted in a coup; the United Brands CEO, Eli Black, committed suicide by jumping from the 44th floor of his New York City office at the same time.(41) Because the famous Watergate scandal was still fresh in everyone’s mind when this scandal happened, it is sometimes called "Bananagate."

The 1975 coup was led by a fellow general, Juan Alberto Melgar Castro, and he ruled for three years (1975-78). He and the general who followed him, Policarpo Juan Paz García (1978-82), get credit for building the current infrastructure and telecommunications system in Honduras, which made foreign trade easier and stimulated economic growth. The coup which Paz García used to oust Melgar Castro was financed by Juan Ramón Matta-Ballesteros, a local drug lord who had ties with both the Colombian Medellín cartel and the Mexican Guadalajara cartel. Central American politics was probably a factor as well, because Paz García was a fan of the dictator next door, Nicaragua’s Anastasio Somoza Debayle, while Melgar Castro wasn’t. The Paz regime was known for more corruption and repression than its predecessors, and it made Honduras a major point on the drug trade route, between Colombia and the United States. When the US Drug Enforcement Administration set up an office in Tegucigalpa in 1981, its resident agent "rapidly came to the accurate conclusion that the entire Honduran government was deeply involved in the drug trade."(42)

The downfall of the Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua and the civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala convinced the Honduran military that they couldn’t go on playing the "Banana Republic" game forever. For that reason, Paz García allowed the election of a constituent assembly in April 1980 and a presidential election in November 1981. 1982 saw a new constitution go into effect and the elected president, Roberto Suazo Córdova, took office. The age of military rule in Honduras was at last over.

Ecuador: From Yellow Gold to Black Gold

Camilo Ponce Enríquez, the president of Ecuador from 1956 to 1960, was remarkably fair and balanced as Latin American leaders go; he included several members of other political parties in his cabinet. Thus, the country remained calm for most of his term, though falling banana prices meant the economy was getting worse. He got elected with some help from his predecessor, José María Velasco Ibarra, but the "National Personification" did not remain his friend for long. When rising unemployment sparked some riots in 1959, the populist Velasco saw his opportunity to run again, and in the next election he had no trouble getting elected to a fourth term.

Having Velasco as president virtually guaranteed political instability, crises, and military intervention; so much for the idea that Ecuador finally had a stable democracy. Ponce was so angry over Velasco's vicious campaign attacks on his government that he resigned on his last day in office, so he would not have to attend the inauguration of his successor. And it seemed that Velasco wanted to make foreign enemies, too; in his inaugural address, Velasco renounced the hated 1942 Rio Protocol, which was practically a declaration of war with Peru. Finally, because Cuba was getting away with challenging the United States, Velasco did likewise, by making anti-American speeches and appointing leftists to government jobs.

The last item offended conservatives, and they rallied behind the vice president, Carlos Julio Arosemena Monroy. Because the vice president also ran the Chamber of Deputies, the government was soon polarized between the president and Congress. At one point, in October 1961, the two sides had a gun battle in the Chamber; fortunately no one was injured. The same month saw the government introduced new sales taxes, to raise badly needed funds, and this caused a general strike and several riots. Blaming the vice president for the unrest, Velasco ordered his arrest, a move which his opponents saw as unconstitutional. In November 1961, only fourteen months after Velasco’s term began, the military removed him from office and replaced him with Arosemena.

To mend relations with the United States, Arosemena named a cabinet that included both liberals and conservatives and quickly sent former President Galo Plaza on a goodwill trip to Washington. However, he also maintained diplomatic relations with Cuba, at a time when the US was calling on all its allies to break relations with the Castro regime. This caused political opponents to call him a dangerous communist, and part of the military went into rebellion against Arosemena, until he broke relations with Cuba (April 1962). After that, Arosemena did not have much support, or the self-confidence to be an effective leader; he reportedly did a lot of drinking during his last year in office. When the military decided to depose Arosemena in July 1963, nobody opposed the move.

This time, instead of installing a new president, the military put a four-man junta in charge. They felt that if they did not carry out some basic social and economic reforms, the trouble would start over again; both Velasco and Arosemena had promised reforms, but failed to deliver. Also, because recent governments had a left-wing tendency, the junta offset that by being strongly anticommunist. In November 1965, the junta member representing the air force had to be dismissed and arrested because of insubordination, so the junta was a three-man team after that.

In 1964 the junta passed an agrarian reform bill that was not very successful. It abolished the huasipungo, Ecuador’s serf-like labor system that dated back to colonial times, expropriated church lands and inefficient haciendas, but only gave land to a fraction of the landless peasants. Worse than that, it also opened up untitled land that had traditionally been occupied by Indian tribes, to settlement and exploitation by outsiders. And income from the country’s main product, bananas, continued to fall; nobody could keep that from causing a major economic crisis. When taxes were raised on imports, the powerful Guayaquil Chamber of Commerce called for a general strike; disgruntled students and labor unions were happy to join them. At the end of March 1966, after a bloody attack on the Central University of Quito only made the military reformers even less popular than they were already, they gave up and stepped down.

To fill the power vacuum, a small group of civilian leaders named Clemente Yerovi Indaburu, a non-partisan banana grower who had served as minister of economy under Galo Plaza, to be the provisional president. They went on to elect a constituent assembly, which drafted a new constitution in October and elected another provisional president, Otto Arosemena Gómez, a cousin of Carlos Julio. He ran the show for twenty months while the constitution went into effect, and then elections for a real president were held in June 1968. Five candidates ran, so in a field that crowded, the winner pulled it off with just a third of the votes. Incredibly, it was Velasco; he was seventy-five years old, it had been thirty-four years since his first victory, and the voters knew he was better as a candidate than as president; nevertheless they elected him for the fifth time.

Velasco’s new political party, the National Velasquista Federation, did not hold a majority in either house of Congress, and he failed to build a coalition with other parties to make up the difference, so his fifth term saw mostly gridlock. Cabinet members were changed very often, in an effort to form a government he could work with, and he couldn’t even get along with his vice president. Finally, his big-spending habits weren’t appropriate for the current economy, but he threw money at the country’s problems anyway. Because he couldn’t get things done by the rules of democracy, on June 22, 1970, he dismissed Congress and the Supreme Court and declared himself a dictator, El Jéfe Supremo. This move is sometimes called an autogolpe (self-seizure of power) because it wasn’t a conventional military coup; he took over all by himself.

Velasco used the dictatorship to decree the economic measures that were essential, but too unpopular for a democracy to pass. This meant devaluing the monetary unit, the Sucre, and raising taxes, especially import tariffs. And because he could not resist baiting the United States again, he dismissed US military advisors, and revived the "tuna war" of the 1950s, by ordering the seizure of US fishing boats caught less than 200 nautical miles from Ecuadorean territory (see Chapter 5, footnote #50).

In 1971 Velasco proposed a plebiscite to ask if the people wanted to replace the 1967 constitution, which he argued made the president too weak to be effective. In its place he wanted to bring back the constitution he had helped write in 1946. But civil unrest from those who opposed his style of rule had gotten so bad that he was forced to cancel the plebiscite. Indeed, he only got as far as he did with the autogolpe and the dictatorship because the military had approved of what he was doing. However, the worsening situation and the frequent shuffle of leaders in the high command eventually changed their minds. But what caused them to oust Velasco was something you’d think would be good for the country -- oil money.

In 1964 geologists had starting looking for oil in Ecuador, and in 1967 they found it in the Oriente region (see Chapter 5, footnote #47). For the first time in history, the eastern jungle had the country’s most important resource.(43) By 1972 the revenue coming in from "black gold" was about to surpass what Ecuador earned from "yellow gold" (bananas). The problem was that the candidate everyone expected to win the 1972 presidential election was Assad Bucaram Elmhalim, a former street peddler of Lebanese descent who had become extremely popular as the mayor of Guayaquil. Both the military and businessmen saw Bucaram as a dangerous and unpredictable man; they did not want him to be president, and they did not want him to get his hands on the petrodollars that the new oil wells were about to produce. Velasco did not like him either, and had deported him to Panama, meaning he was running for president from exile. Still, the military could not risk having Bucaram win. In February 1972, four months before the date of the election, the military deposed Velasco and sent him into exile once more.(44) A three-man junta, led by the Army chief of staff, General Guillermo Rodríguez Lara, took his place, and like the military regimes running Peru and Brazil, it gave no promise of restoring civilian rule any time soon.

The new junta called itself "nationalist and revolutionary," but like the previous military regime, "reactionary" would have been a better description. Former president Otto Arosemena and several other politicians were tried for corrupt behavior in how they granted oil concessions during the 1960s. Also charged with corruption were several members of the latest Velasco regime, supporters of Bucaram, drug dealers, legitimate importers and customs officials. On a positive note, it launched the Ecuadorian State Petroleum Corporation (Corporación Estatal Petrolera Ecuatoriana, or CEPE), to exploit the country’s oil reserves, renegotiated the terms of the agreements made with the international oil companies, to give Ecuador a better deal, and persuaded the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to admit Ecuador as a member in 1973.

Alas, oil production did not solve Ecuador’s economic problems. Because the price of Ecuadorean oil was high, compared with that from other countries, there weren’t as many buyers as expected, while imports, encouraged by a low-tariff policy imposed to control inflation, increased rapidly. The government tried to get a handle on the imports by decreeing a 60 percent duty on imported luxury items in August 1975. Needless to say, among those who depended on the sale of imports, like the Quito and Guayaquil Chambers of Commerce, this went over like a lead balloon. In response, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff launched a bloody coup against Rodríguez Lara in September. It failed, but a second coup in January 1976 succeeded in toppling the general; Rodríguez Lara was replaced by a triumvirate, where the commanders of the army, navy and air force shared power.

The first thing this three-man team decided was that since military rule had not worked much better than civilian rule, they might as well give the government back to civilians. Among other things, the September 1975 coup showed that the armed forces were not in unity on what must be done. They made plans to hold a referendum on two proposed constitutions, and presidential elections in February 1978, but the aforementioned lack of unity spread to the junta, and caused one delay after another. When the referendum took place, in January 1978, the voters could choose between the constitution of 1946 and a progressive, newly drafted charter; they went with the new one. For the presidential election, five candidates ran, and the only way the junta got involved was to prohibit Bucaram from running again. However, the candidate from Bucaram’s party, Jaime Roldós Aguilera, came in first place with 27 percent of the vote. The law required a runoff between Roldós and the second-place candidate, Sixto Durán Ballén. But problems in organizing the election and counting the votes led to serious doubts about whether the runoff would be fair; the Supreme Electoral Tribunal was completely reorganized to resolve that issue. There were also questions about whether the government had anything to do with the murder of a third-place candidate, a populist named Abdón Calderón Múñoz. In the end the runoff did not happen until nine months after the first round of voting.

Conservatives hoped that the extra campaigning time would allow Durán to pull ahead of Roldós -- they saw a vote for Roldós as a vote for Bucaram. Instead, Roldós got an unquestionable majority, 68.5 percent of the vote. As you might expect, the junta would have preferred having someone else win, but international pressure and the size of Roldós’ overwhelming victory forced them to accept the results. Still, they let the winner and his running mate, Osvaldo Hurtado, take office with conditions. First, they asked for (and got) the right to name the minister of defense and the representatives to the boards of directors of major state corporations. Second, because Roldós campaigned on the slogan of "we will not forgive, we will not forget," they let him know they would not allow any investigation of human rights abuses under military governments. Roldós agreed to those terms and became president three months after the second round of voting, on August 10, 1979.

Tupamaros and Tyrants

A happy place in the early twentieth century, Uruguay was in a deep blue funk as the 1950s ended. The problem was that world demand for Uruguayan products like meat and wool had fallen, causing inflation, mass unemployment, and a steep decline in the standard of living. That resulted in student militancy and labor unrest.

The National (Blanco) Party had been out of power for nearly a century when it was elected in 1958 to deal with the declining economy. Not only did it fail to do its job, but factions in the party became visible after the death of the Blanco leader, Dr. Luis Alberto de Herrera, in 1959. From 1959 to 1967, eight Blanco governments came and went. By 1962 inflation was running at 35 percent, which was a record for Uruguay at this time. The Blancos did win that year’s election, but their margin of victory was much smaller (24,000 votes ahead of the Colorado Party, compared with a 120,000-vote lead in 1958). Then in 1964 came the death of another important leader, Luis Batlle Berres, ensuring that the Colorado Party would also be in less capable hands. Finally, two important movements got started in the early 1960s. In 1964 workers formed Uruguay’s version of the AFL-CIO, a supersized labor union called the National Convention of Workers (CNT). In the northern part of the country, Raúl Antonaccio Sendic, the head of the sugarcane workers, formed an urban guerrilla organization, the National Liberation Movement-Tupamaros (MLN-T), in 1962.

In the previous chapter, we saw Uruguay adopt a Swiss-style colegiado, where executive power went not to a president, but to a nine-member council. Individuals from both major parties blamed this system for the government’s inability to get things done. In the 1966 elections, three constitutional amendments were introduced to replace the council with an elected president who served a five-year term. Both the Colorados and the Blancos supported the amendments, and a new constitution was written in 1967 that incorporated the changes. Finally, three new agencies were created that modern governments consider essential: the Office of Planning and Budget, the Social Welfare Bank, and the Central Bank of Uruguay.

Predictably, the voters also turned out the Blanco government in 1966, voting to bring back the Colorados. Oscar Gestido, a retired army general who had also successfully run the State Railways Administration, became the new president. But inflation continued to get worse, and Gestido died in December 1967. His vice president and successor, Jorge Pacheco Areco, was the former director of the newspaper El Día, but otherwise people didn’t know much about him. Nevertheless, he would make some fateful decisions that have affected Uruguay ever since.

The first decision came just one week after taking office; Pacheco issued a decree banning all leftist groups and left-wing publications, because he believed they were subverting the constitution and promoting armed struggle. Then in June 1968, he declared a wage and price freeze, because inflation had reached the nightmarish rate of 183 percent. Students and the CNT protested these policies, and the government put down their demonstrations and strikes by force. The constitution allowed the declaration of a state of siege, in order to use extra security measures during times of extraordinary unrest, so Pacheco had the country under a state of siege for nearly all his term as president. His justification was the growing threat from the Tupamaros.

Unlike most guerrilla movements, which tend to do better in the countryside (where they are harder to locate and catch), the Tupamaros specialized in urban warfare, so Montevideo became their base of operations. At first they acted like twentieth-century Robin Hoods, robbing banks and delivering food and money to poor neighborhoods. Before long they expanded their operations to include political kidnappings and attacks on security forces. By the end of the 1960s they were killing their enemies outright. In September 1971 more than 100 Tupamaros escaped from prison, and Pacheco responded by putting the army in charge of crushing all guerrilla activity.(45)

A truce between the government and the Tupamaros (October 1971-April 1972) permitted elections in November 1971. The main issue was a constitutional amendment allowing a second term for the president; Pacheco’s supporters favored the amendment, of course. It was voted down, but Pacheco got the next best thing; the candidate he picked to succeed him won the election. That was Juan María Bordaberry Arocena of the Colorado Party, who crossed the finish line with a lead of 10,000 votes, after the vote count was mysteriously halted and resumed. Also important was the fact that a number of minor parties -- from Christian Democrats to Communists -- got started in the 1960s, and this was the first election in which they challenged the two major parties, securing between them twenty percent of the votes. The most important newcomer was the Broad Front (Frente Amplio or FA in Spanish), a coalition of more than a dozen leftist parties that formed in 1971; it would become a majr player from the 1990s onward.

Overall Bordaberry continued Pacheco’s policies. In April 1972, when the Tupamaros were at their peak, he declared a state of "internal war" and suspended all civil liberties, first for thirty days and then for a year. By giving the armed forces and the police all the resources and funding they needed, they were able to defeat the Tupamaros; by the end of 1972, those Tupamaros left alive were either in prison or in exile. But after that victory, the crisis was not declared over. The military was tired of civilian rule, which had gone on in Uruguay for the past seventy years; now the military wanted to take over and show everyone it could do better.

The military made its move in February 1973, when Bordaberry picked a civilian, not a military officer, to be the next minister of national defense. With the air force backing it up, the army issued two communiqués proposing the political, social, and economic measures it wanted. Within a matter of days the navy joined the other two services as well. Bordaberry agreed to give the military a role in decision making, and they created an advisory body called the National Security Council; its members included the commanders of the army, navy and air force, plus the ministers of national defense, the interior, and foreign affairs.

The one obstacle keeping the National Security Council from running the country was the General Assembly, which was investigating charges of torture committed by the military. On June 27, 1973, Bordaberry dissolved the General Assembly, and gave the armed forces and the police the green light to do whatever was needed to restore peace and order. In effect this was a legalized coup; henceforth Bordaberry would be just a figurehead. The new dictatorship’s first targets were the CNT, which had just called for a strike in the factories, and student unrest in the university.

Imitating the dictatorship in neighboring Brazil, the military regime sent thousands to jail on charges of political crimes, while others died or disappeared. Many were tortured; government workers were fired if they were not seen as loyal; freedoms of the press and assembly were restricted. According to Amnesty International, in 1976 Uruguay had more political prisoners per capita than any other nation -- one out of every 500 citizens. By 1980 and one in every 500 had received a sentence of six years or longer. Between 300,000 and 400,000 Uruguayans, about 10 percent of the population, went into exile.

In 1976 Bordaberry submitted a proposal calling for the elimination of all political parties and the establishment of a permanent dictatorship with himself in charge of it. Instead, the military forced him to resign. The head of the Council of State, Alberto Demichelli Lizaso, ruled for three months, and then was replaced with Aparicio Méndez Manfredini, a former health minister. Aparicio Méndez used to belong to the National Party, but he got along so well with both civilians and the military that he was allowed to be president for five years (1976-81).

The military government announced its own political proposal in 1977. Over the next few years, they would purge the National Party and the Colorado Party, and hold national elections that would feature just one candidate accepted by both parties. A charter that gave the military virtual veto power over all government policy was drawn up, and in 1980 the armed forces decided to turn it into a new constitution by submitting it a plebiscite. Instead their plan backfired; the electorate voted against the proposed constitution 57-43, proving that at least Uruguay’s elections were free.

Voters turned against the government not only because it was oppressive, but also because it could not keep the economy running smoothly for long. The regime’s leaders had been hoping a strong economic performance would legitimize their rule and justify whatever else they did. With both the General Assembly and the unions gone, the military and its civilian allies saw an opportunity to rebuild a free-market economy the way they liked it. This meant lifting restrictions on the exchange rate (so that the peso could be freely converted to and from other currencies); opening branches of foreign banks; reducing tariffs, promoting more exports and more trade with Argentina and Brazil; and less regulation of farms and ranches, since Uruguay was still basically an agricultural state. Strict control of wages -- and spending on social services -- succeeded in cutting inflation to 20 percent by 1982.