| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Latin America and the Caribbean

Chapter 6: Contemporary Latin America, Part III

1959 to 2014

This chapter is divided into seven parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| One More Overview | |

| Cuba: The Revolution Continues | |

| Venezuela's Democratic Interlude | |

| Brazil: The Death of the Middle Republic | |

| Weak Radicals and the Argentine Revolution | |

| Colombia: The National Front |

Part II

| Che! | |

| Democracy Breaks Down in Chile | |

| Peru: The Revolution from Above | |

| Mexico: The PRI Corporate State | |

| Meet the Duvaliers | |

| Honduras Goes From Military to Civilian Rule | |

| Ecuador: From Yellow Gold to Black Gold | |

| Tupamaros and Tyrants | |

| The Somoza Dynasty, Act Two |

Part III

Part IV

| The Salvadoran Civil War | |

| Belize: A Nation Under Construction | |

| The Guatemalan Civil War | |

| The Southernmost War | |

| Among the Islands | |

| Colombia: Land of Drug Lords and Guerrillas | |

| The Pinochet Dictatorship | |

| Peru: The Disastrous 1980s |

Part V

| The Switzerland of Central America | |

| Nicaragua: The Contra War | |

| Ecuador After the Juntas | |

| Chasing Noriega | |

| Argentina’s New Democracy | |

| Hugo's Night in the Museum | |

| Democracy Comes to Bolivia (at Last) | |

| Haiti: Beggar of the Americas | |

| Peru: The Fujimori Decade |

Part VI

| Brazil: The New Republic | |

| Cuba's "Special Period" | |

| Chileans Put Their Past Behind Them | |

| Colombia’s Fifty-Year War | |

| Uruguay Veers from the Right to the Left | |

| Daniel Ortega Returns | |

| Ecuador: Dollarization and a Lurch to the Left | |

| The Chavez Administration, Both Comedy and Tragedy |

Part VII

| Argentina: The New Millennium Crisis, and the Kirchner Partnership | |

| Guatemala Since the Peace Accords | |

| Can Paraguay Kick the Dictator Habit? | |

| Honduras: The Zelaya Affair | |

| Peru in the Twenty-First Century | |

| Bolivia: The Evo Morales Era | |

| The Mexican Drug War | |

| Puerto Rico: The Future 51st State? | |

| Conclusion |

Paraguay: The Stronato

We noted earlier in this work that German immigrants came to South America in the late nineteenth/early twentieth century, but otherwise we did not mention them because they did not have much of an effect on the countries they settled in until after World War II. Like other Europeans they were attracted to the temperate climate in the nations south of the Tropic of Capricorn (see Chapter 5, footnote #32). Today there are more than 3 million people of German ancestry in Argentina (7.5% of the population), another 3 million in Brazil, 500,000 in Chile, 375,000 in Bolivia, 290,000 in Paraguay, 180,000 in Peru, and 50,000 in Uruguay. After arrival they kept in contact with the old country and founded German nationalist groups; in 1931 Paraguayan Germans founded the first National Socialist (Nazi) Party outside of Germany. After the war, three of the most popular destinations for Nazis fleeing the Allies were Argentina(49), Brazil and Paraguay, because of the aforementioned climate, the opportunity to disappear into the local Aryan communities, and because those countries had governments that at least looked fascist. The three most famous Nazis to escape to South America were Adolf Eichmann, Klaus Barbie and Josef Mengele.(50)

Alfredo Stroessner Matiauda (1912-2006), like most Paraguayans, was a Mestizo, the son of a German immigrant and a Guarani woman. He joined the army when he was sixteen, and over the next two decades he became a hero in the Chaco War, and Higinio Moríñigo’s most important general in the Paraguayan Civil War. When he took over in a bloody coup that killed at least 50, many expected Stroessner to be a short-lived caretaker leader, like his immediate predecessors; for one thing, he did not lead an important faction of the Colorado Party. Instead, Stroessner proved to have political as well as military skills; his thirty-five-year reign (1954-89), sometimes called the Stronato, is a record among South American dictators. He lasted as long as he did because unlike the Nazis, he did not make war with Paraguay’s neighbors, only committing acts of violence against enemies inside the country. Although Paraguay has not had any external enemies since the end of the Chaco War, the military was kept large to deal with internal ones.

The other key to Stroessner’s longevity was a strategy that we have seen plenty of already -- heavy use of repression and terror. Immediately after coming to power, he declared the country to be in a state of siege, allowing him to rule by martial law. The 1940 constitution only allowed a state of siege for three months, so Stroessner renewed it whenever those three months were up. Consequently, he kept the state of siege going in most of the country until 1970 and in Asunción until 1987. As you might expect, during this time enemies of Stroessner (both real and imagined) were harassed, tortured, and "disappeared," elections were rigged, and corruption was both normal and expected. One of Stroessner’s favorite tactics was to decorate the countryside by having dissidents thrown out of airplanes without parachutes.

Stroessner had quite a few opponents when he got started; the economy wasn’t getting any better, and nobody liked the economic austerity measures he imposed. Among the officers who were his chief rivals, one retired early on, another died of natural causes, and a third who got his support from Argentina lost it when Juan Perón was deposed in September 1955; that certainly made Stroessner’s job easier. On the other hand, the new Argentine government did not like Stroessner because he got along with Perón (you may remember that Asunción was Perón’s first stop when he went into exile), and punished Paraguay by canceling a trade agreement.

This Paraguayan postage stamp, issued right before Perón fell from power, shows Stroessner (left) with Perón (right).

Stroessner won an election to a second term in 1958, and unhappy members of the Liberal and Febrerista Parties responded by launching a guerrilla war. Argentina and Venezuela gave aid to the rebels, because both of those countries had recently gotten rid of their caudillos; so did Cuba, after Castro took over. Thus, 1958 and early 1959 saw waves of terror and counter-terror in Paraguay. Then in April 1959 Stroessner briefly yielded to pressure, and tried to take the wind out of the opposition by reforming the army and the Colorado Party. In a two-month period we can call the "Paraguayan Spring," he lifted the state of siege, allowed exiles to return, stopped censoring the press, freed political prisoners, and promised to rewrite the 1940 constitution.

Alas, this promising turnaround brought anarchy. When a student riot erupted in downtown Asunción over a bus fare increase, leaving nearly a hundred injured, Stroessner resumed the state of siege and dissolved Congress. Naturally the guerrilla war resumed, too, but this time Stroessner had the upper hand from the start. By now he had total control over the Colorado Party, thanks to the purges that got rid of the factions that didn’t want him running it; moreover, he was now receiving military aid from the United States (at this stage in the Cold War, Uncle Sam hadn’t met an anti-Communist he didn’t like). Most of all, the economy was finally starting to get better, and when right-wing military coups in Brazil (1964) and Argentina (1966) installed governments like Stroessner’s, the pressure on Paraguay from the outside world eased off. By the mid-1960s, the Liberals and the Febreristas were exhausted, and because they were no longer a threat to his rule, Stroessner allowed them to return, giving them and the newly formed Christian Democratic Party a few seats in Congress, to make them think they had power.

Because of the poor relations with Argentina mentioned above, Paraguay cultivated closer ties with Argentina’s old rival, Brazil. In 1956 Brazil and Paraguay agreed to build roads and a bridge over the Parana River, and Brazil granted duty-free use of Atlantic ports; this broke Paraguay’s traditional dependence on Argentina for access to the outside world. Then when Brazil built the Itaipu Dam on the Parana, it caused an economic boom in Paraguay; the dam created thousands of construction jobs, and Brazil shared the electricity generated by the dam with Paraguay. During the years when the Itaipu Dam was under construction (1973-82), Paraguay’s gross domestic product grew by more than eight percent a year.

Unfortunately, the economic boom was followed by a slump, after the dam was finished. Discontented, now-unemployed workers demanded reform, and many left the country to find jobs; it has been estimated that during the 1980s, as many as 60 percent of Paraguayans may have been living abroad. Back at home, the completion of the dam encouraged between 300,000 and 350,000 Brazilians to come across the border and settle in eastern Paraguay. Consequently Portuguese was the most widely spoken language in the eastern border region, and Brazilian money was accepted as legal tender. If any Paraguayans were worried about losing that part of the country to Brazil, I wouldn’t blame them!

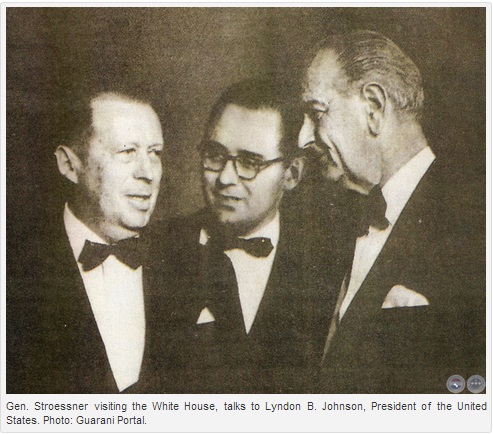

Stroessner’s other friend in foreign places was the United States. First and foremost, the Yankees wanted their allies to fight communism, and that suited Stroessner just fine. During his 1958 tour of Latin America, US Vice President Richard M. Nixon made a stop at Asunción, and Nixon praised Stroessner for making Paraguay the most anti-communist nation in the world. From 1947 to 1977, the United States supplied arms to Paraguay, and gave Paraguayan officers training in counterintelligence and counterinsurgency operations. In return, Paraguay voted the same way as the United States at meetings of the United Nations (UN) and the Organization of American States (OAS), and Stroessner once remarked that the US ambassador was so important to Paraguay, he might as well be another member of his cabinet. Relations hit a bump when John F. Kennedy was president; Kennedy threatened to cut off aid if progress on democracy and land reform wasn’t made. However, Kennedy’s successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, was another determined anti-communist, so under LBJ relations improved again (see the above picture). Thus, Stroessner was an enthusiastic participant in Operation Condor, South America’s anti-communist military campaign in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Finally, when Jimmy Carter became the US president, he promoted a foreign policy that emphasized human rights, causing relations with Paraguay to sour for the rest of the Stronato.

And not only the US government grew critical of Stroessner. From the late 1960s onward, the Catholic Church criticized Stroessner for the torture and disappearances of political prisoners, and for staying in office too long. Stroessner’s response was like that of other Paraguayan leaders who did not get along with the Church; he closed Roman Catholic publications and newspapers, expelled non-Paraguayan priests, and interfered with the Church’s activities among the poor. In 1980 the OAS joined those calling for reform, when it condemned human rights violations in Paraguay, calling them "an affront to the hemisphere's conscience." Finally, international groups charged the Paraguayan military with killing 30 peasants and arresting 300 more, after the peasants had protested against encroachments on their land by government officials.

When Stroessner’s counterpart in Nicaragua, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, was thrown out by the Sandinistas in 1979, Stroessner took him in. Only one year later, though, assassins managed to kill Somoza with a bazooka. This is exactly what is not supposed to happen under a military dictatorship, and it was a sign that Stroessner’s regime was starting to crumble, definitely a bad omen.

For the 1988 presidential election, Stroessner allowed opposition candidates to run against him, only to have the police and members of the Colorado Party harass them; they also were not allowed air time in the media. After the voting, Stroessner was declared the winner with 89 percent of the vote. It may have looked like business as usual for the Stronato, but it was also the last hurrah for the aging dictator. On February 3, 1989, six months after being sworn in for an eighth term, Stroessner was toppled in a military coup headed by General Andrés Rodríguez. The fallen strongman fled to Brazil, where he lived in exile until his death in 2006.

Brazil: The Military Republic

The military took over in Brazil because an authoritarian solution was needed when the civilian government broke down. It held on from 1964 to 1985 because no civilian politician could be found who was acceptable to all factions of the armed forces. Marshal Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco became the junta’s first president, serving the remainder of ex-president João Goulart’s term (1964-67).

Castelo Branco showed the regime was not going to try anything radically different from what had been tried already, when instead of appointing military officers to fill every government position, he had a group of non-political civilians, led by a former ambassador to the USA, introduce a strict economic program, that called for austerity and deflation. Moreover, Brazil’s junta was not as brutal as its counterparts in Chile and Argentina; there weren’t right-wing death squads roaming around, for instance. This probably stems from the Portuguese/Brazilian character we noted previously in this work, the same willingness to settle differences that made previous Brazilian conflicts less bloody than those in other parts of Latin America. It also caused some wags who were not familiar with this attitude to remark that "Brazil couldn’t even organize a dictatorship properly." Still, Castelo Branco dissolved all existing political parties, replaced them with an official presidential party and a legal opposition party, recessed and purged Congress, removed objectionable state governors, and ruled in an arbitrary manner. When his term ended in 1967, he refused to serve for another one.

Whereas Castelo Branco tried to keep a small amount of democracy, the next two presidents were determined hardliners, who regarded politicians as scoundrels and were willing to stay for however long it would take to (1) stamp out communism and other left-wing movements, and (2) turn Brazil into one of the world’s major powers. Marshal Artur da Costa e Silva ruled from 1967 until his death in 1969. He introduced draconian laws; the Lei de Segurança Nacional (National Security Law) of 1967 made political dissidents fair game to be tortured, murdered or -- perhaps worse -- thrown into Brazilian jails. This was followed up a year later with a very unpopular censorship law, the Ato Institutional 5 (AI-5). In response, Brazil’s students held a mass demonstration in Rio de Janeiro against the dictatorship, called the Passeata dos cem mil (March of the 100,000), in June 1968. The Catholic Church, which had supported the 1964 coup, also became an opponent of the government; Liberation Theology had persuaded many clergy to switch sides.

When Costa e Silva died suddenly, the military did not even bother to hold a rigged election; the senior officers simply got together and picked the next president, General Emílio Garrastazú Médici (1969-74). Cut from the same cloth as Costa e Silva, Médici showed the world that one did not need popular support, a political party, or an ideology, to rule a country.(51) His regime oversaw the darkest days of the dictatorship; there were acts of terrorism and kidnappings in the cities (among those kidnapped was the US ambassador), and a guerrilla uprising based in northern Goiás. The government responded with spying on political opponents, dirty tricks, torture, and "disappearings." All this hurt relations with the United States, whose leaders had expected democracy to return as the menace of communism faded.

Costa e Silva and Médici reaped the rewards of Castelo Branco’s belt-tightening, enjoying an "economic miracle" that lasted through the late 1960s/early 1970s; the economy grew by 10-12% each year. Moreover, industrial development, financed by large foreign loans, reached the point that the country could earn more from manufactured goods than it did from coffee. For the first time in history, Brazil’s economy was not dependent on a single commodity; that persistent Latin American problem had been solved. Even after the whopping increase in world oil prices in 1973, Brazil still managed a growth rate between 4 and 7 percent a year. This, and Brazil’s victory in the World Cup(52) soccer match of 1970, generated enough confidence to start construction on some colossal projects: the 2,500-mile-long Trans-Amazonian Highway, which went from the Atlantic almost all the way to Peru; the great Itaipu Dam on the Paraguayan border; the Rio-Niterói Bridge across the entrance to Rio de Janeiro’s harbor; and the Ilha do Fundão campus for Rio de Janeiro Federal University.

By 1973 the guerrillas had been defeated, as much by the economic miracle (people do not revolt when they can see their lives getting better) as by the government’s repressive tactics. But at the same time there had not been land reform in the countryside, so millions of peasants moved to the cities, adding enormous favelas (slums) to the urban landscape. And because it looked like the combination of authoritarian rule and free-market capitalism would bring about full industrialization and great-power status, Brazil’s success encouraged officers in Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, and Uruguay to seize power in their countries.

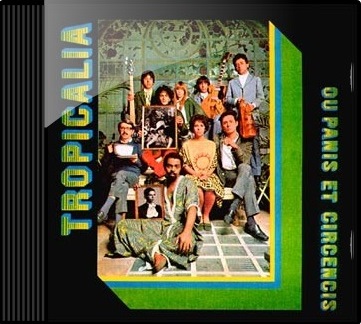

The period of the Military Republic was also a culturally brilliant time -- largely in response to the junta’s suppression of free speech. The founders of modern Brazilian music -- Gilberto Gil, Caettano Veloso, Tom Zé, Os Mutantes and Gal Costa -- all got started in the 1960s. In 1968 they worked together on an album named Tropicália ou Panis et Circensis (Tropical Bread and Circuses), which set the pattern for a new genre of music called Tropicália, mixing tradition with innovative song styles and criticizing the coup of 1964. At first the government tolerated this movement, because liberal opponents of the regime didn’t like it, but then turned against it when it decided the music encouraged anarchy and violence, forcing the artists to flee to Europe. Also important at this time was Fernando Henrique Cardoso, a left-wing sociologist from the University of São Paulo, and a best-selling author; he ended up spending time in exile (1968-78), but went on to become a future president after his return.(53)

The Tropicália album cover.

Even when they looked victorious, the hardliners were unable to cast Brazilian society in the form they desired. There was too much opposition from the population and even from some of their colleagues. In addition, foreign opinion disapproved of what they were doing, especially the United States. During the Cold War era, if you were against communism, you needed to get along with the United States, because it was the strongest anti-communist nation, but Washington also proclaimed itself the champion of freedom, meaning its allies could no longer claim they were defending democracy while they were destroying it. To preserve the appearance of being pro-freedom, and to keep on Washington’s good side, Brazil’s military strongmen knew they had better not develop a cult of personality, the way the Duvaliers had done in Haiti, and instead of ruling for life, each general-president was required to hand over the reins of power to someone else after holding the top spot for no more than five years.

When Médici's term in the presidency ran out, he was succeeded by Ernesto Geisel (1974-79), a retired general and the former president of Petrobras, the Brazilian oil company. At first civilians thought Geisel’s rule would be more of the same. What they didn’t know was that there had been intense maneuvering behind the scenes, with the moderate officers in favor of Geisel and the hardliners against him. Thus, when Médici accepted Geisel as his replacement, it was a victory for the moderates; now that the political chaos was behind them, the hardliners were no longer needed.

Geisel had two goals for his presidency: (1) ease restrictions on the country in a way that would steer it toward democratic rule, and (2) keep the high economic growth rates while minimizing the effects of high oil prices. He called his political program distensão, a gradual relaxation of authoritarian rule, at the end of which, the military would retain enough power to prevent the worst excesses of civilian rule. As he put it, this would be "the maximum of development possible with the minimum of indispensable security." For the economy, the government borrowed billions of dollars to pay for oil subsidies, and more infrastructure investments -- highways, telecommunications, dams, mines, and factories. This was an unstable way to run an economy; borrowing lots of money during a time of rapid growth caused inflation, which only got worse when wages went up to match rising prices. Against the objections of those who did not want to see foreign companies in Brazil, Geisel invited them to come explore for oil. Meanwhile the United States objected to the human rights abuses that it still saw, and an agreement Brazil reached with West Germany to build nuclear reactors; the latter went against US wishes to keep nuclear technology from spreading to countries that didn’t have it already. Figuring that the United States just didn’t understand Brazil’s situation, Geisel renounced the military alliance with the United States in April 1977.

Geisel’s distensão program did not produce the results he wanted. When he allowed free legislative elections in 1974, the opposition won big, not the junta-sponsored party, and in 1978 he had to deal with labor strikes from the São Paulo car industry, the first strikes since 1964.(54) Nevertheless, he stuck to this course; he allowed the return of exiles, restored habeas corpus, and repealed the extraordinary powers decreed by his predecessors. In March 1979 his term ended, and his right-hand man, General João Baptista Figueiredo (1979-85) became the last military president.

Figueiredo said at the outset that he took over the presidency more out of a sense of duty than political ambition. Under him, distensão was renamed abertura ("opening toward democracy"), and he signed a general amnesty into law that pardoned all political prisoners and exiles; the hardliners reacted to this with a series of terrorist bombings. An April 1981 bombing confirmed that members of the military were behind the terrorist acts, but Figueiredo showed he was too weak to punish the guilty. This, and the growing problems of inflation and the national debt, made Figueiredo unpopular, and strengthened the public's resolve to end military rule.

Economic matters took center stage in the early 1980s. By now inflation was galloping along at more than 100 percent a year. In 1982 international interest rates rose so high that Brazil could no longer make interest payments on its foreign debt, the largest in the world at this date ($87 billion). Ten years after the economic miracle, Brazil’s leaders found themselves presiding over the worst financial mess in the country’s history. The IMF imposed a painful austerity program, which required that Brazil hold down wages to fight inflation. While this was good for the economy as a whole, it wasn’t good for the people.(55) Figueiredo's administration stressed exports--food, natural resources, automobiles, arms, clothing, shoes, and electricity--and expanded petroleum exploration to raise more revenue for debt payments. In 1983 the GDP grew by 5.4 percent, which normally is a good thing, but because of inflation and the failure of political leadership, few noticed. In addition, Figueiredo's heart condition made him go to the United States for bypass surgery, meaning that for much of his time in office after that, he was not in control of the situation.

During the second half of the Figueiredo administration, it seemed like the military was eager to relinquish power, because the solutions for Brazil’s problems that it tried were not working very well. Still, it did not want to give all power to the people too quickly. In 1982 elections were held for local, state and legislative positions; the opposition got more votes than the Democratic Social Party (PDS), the junta’s choice, but with the president controlling both the federal budget and the funds going to the states, the military was still the group ultimately in charge.

Likewise, when the government decided to allow a presidential election in January 1985, it insisted on an indirect election, where the Electoral College would do all the voting. Most of the electors were members of the PDS, so the government-approved candidate, Paulo Salim Maluf, was expected to win. Instead, disputes caused a split in the PDS, and a group of electors went over to the opposition candidate, Tancredo Neves, allowing Neves to win 480-180. This upset also made the election and the new government legitimate in the eyes of the world, because nobody could claim the military rigged the vote when it did not go the way they wanted. The armed forces had to accept the result, for to do otherwise would jeopardize the foreign help they were seeking to tackle the debt problem.

Neves definitely had enough experience to be president; he had been prime minister, minister of finance, and minister of justice and interior affairs under the Goulart presidency, more than twenty years earlier. And under the Military Republic he had governed the state of Minas Gerais. But he was also seventy-four years old, and suffering from an abdominal ailment; during the 1984 election campaign he was too busy to get treatment for it. In the days leading up to the inauguration his health deteriorated so rapidly that he never took office; instead he was rushed to the hospital and his vice presidential candidate, José Sarney, was sworn in. One month later Neves died, so Sarney filled the presidency for all of Neves’ term, from 1985 to 1990. As it had been with the regime changes of 1822, 1889, 1930, 1946, and 1964, the change of government in 1985 proved to be a more difficult challenge than expected.

Bolivia: The Banzerato

Since independence, Bolivia has been the poorest country in South America, and the least stable; at times it seemed that Bolivia changed governments as often as most of us change underwear!(56) We won’t go into the causes of those problems, or cover too many details of the troubles that followed; we did that in the previous chapters already.(57) It did look like Bolivia was breaking out of the vicious cycle of poverty and tyranny, when Ángel Víctor Paz Estenssoro founded the Nationalist Revolutionary Movement (MNR) in 1941, and launched a social revolution in 1952. That revolution was less bloody than the revolutions in Mexico and Cuba, and also less permanent. By the end of the 1950s, the revolution was over (a political scientist, James Malloy, called it "the Uncompleted Revolution"), and a new elite, namely the MNR, was in charge.

The second president after the revolution was Hernán Siles Zuazo, Paz Estenssoro’s chief associate in the MNR. When Siles’ term ended in 1960, Paz Estenssoro ran again, and was elected again. Though he and the MNR still had the backing of the miners, peasants and the United States, they could not raise the country’s standard of living or make any part of the economy more productive. There was also the question of what to do with the miners’ and workers’ militias. They had been so useful in defending the revolution from a military counter-coup that most of them were allowed to keep their weapons, but now they were likely to support the MNR’s radicals, led by vice president Juan Lechín (see Chapter 5, footnote #73), not the MNR coalition as a whole. Paz Estenssoro, on the other hand, felt that the newly rebuilt and re-equipped armed forces were now more trustworthy than the militias; moreover, he was under pressure from the United States to use the military against any communist uprising that might develop. Thus, the next few years saw violence and dissent, with the former revolutionary president becoming increasingly autocratic, and working with the military to keep a lid on the unrest.

With Juan Lechín leading the left wing of the party, and Siles Zuazo leading the right wing, Paz Estenssoro came to believe that the party would only stay together as long as he remained the ultimate authority in the middle. For that reason, when the 1964 election drew close, he amended the constitution to allow himself to run for a consecutive term. Here he stepped too far, for many upper-class Bolivians were now tired of him and wanted to see someone else -- like one of themselves -- become president for a change. And he showed that the old revolutionary had become a reactionary when he chose the commander of the air force, General René Barrientos Ortuño, for his running mate. Paz Estenssoro won a third term because the military and the peasants continued to support him, but the other factions either voted for another candidate or abstained from the election completely. Three months after the term started, in November 1964, military turned against the MNR and ousted it in a coup, led by Barrientos and the army commander, General Alfredo Ovando. Paz Estenssoro went into exile again, and the MNR made sure it would not stage a quick comeback by splitting three ways; Siles turned his faction into the Revolutionary Nationalist Leftwing Movement (MNRI), and Lechín formed the Revolutionary Party of the Nationalist Left (PRIN). The military, having gone back to its old habits, now began another eighteen years of rule.

At first Barrientos and Ovando proclaimed a junta with themselves as co-presidents, but Barrientos was clearly the more popular of the two. When Ovando realized this, he proposed letting Barrientos be the sole president, if Ovando could be commander in chief of the armed forces, and Barrientos said it’s a deal. To the people, Barrientos reassured them that the military had not come to destroy the 1952 revolution, but to save it from leaders gone astray.

The common people liked Barrientos because he spoke the Quechua language fluently, and they found him very approachable. This charisma allowed him to win over the support of the peasant unions, which he used as a check against labor unrest in the mines. He was also remembered for an incident in 1960 when fifteen members of the air force did a skydiving exercise and three parachutes did not open, causing those wearing them to fall to their deaths in front of a crowd. As air force commander, Barrientos was seen as responsible, and he responded by going on his own skydive, using one of the parachutes that failed to open the first time. This daredevil act proved that only bad luck was to blame -- the equipment and training were fine -- and it endeared him to those who saw him put both his life and reputation on the line.

Rising tin prices in the mid-1960s, exports of oil and natural gas, and foreign investment, allowed the economy to grow for the first time in more than a decade. Barrientos formed his own political party, the center-right Popular Christian Movement (MPC), and legitimized his rule by winning the presidential election of 1966. In October 1967 the army defeated the attempt by Ernesto "Che" Guevara to start another revolution, this time among the peasants in the Bolivian countryside. The capture and killing of Guevara briefly gave the Bolivian government some good press in the Free World(58), but then more internal unrest followed, and Barrientos spent much of his time after that traveling to remote villages, so he could meet the peasants and hear their grievances in person. It was on one of those trips that he was killed in a helicopter crash in 1969.

During the next two years, Bolivia was governed by three presidents (one of them General Ovando), and two juntas; none of them were strong rulers. The last of them, Juan José Torres González, started to lead the country in a leftist direction, by calling a "People’s Assembly," a congress where people were represented according to their jobs (e.g., miners, teachers, peasants, etc.) instead of where they lived; he also restored Juan Lechín as a labor leader, heading the Bolivian Workers’ Union (COB). One of those who opposed these moves was Colonel Hugo Banzer Suárez, a highly respected officer who tried several times to overthrow Torres; in August 1971 he finally succeeded. Apparently the United States and Brazil supported the bloody coup which Banzer used to seize power, but it is not clear if they gave him anything besides funds and advice. Torres fled to Argentina, where in 1976 he was kidnapped and shot; Argentina’s right-wing death squads are thought to have been responsible, making Torres one of the highest-ranked victims of Operation Condor.

Banzer ruled for seven years (1971-78), a marathon by Bolivian standards. Order was his highest priority; he hated the protests and political disunity that had characterized the 1960s. Therefore it was only natural for him to ban left-wing political parties, suspend the COB, and close the universities. A lot of Bolivians, both conservatives and liberals, agreed with him at this stage, so the first three years of Banzer’s dictatorship (now called the Banzerato) were the "good" part of it. Unprecedented economic growth came with stability; there were great increases in the production and export of oil, natural gas, tin and cotton. But even then the government couldn’t do without acts of brutal repression; it suppressed a general strike by force in 1972, and when a sudden increase in food prices in 1974 prompted peasants to set up roadblocks in the Cochabamba Valley, the military cleared the roads with a massacre. Human rights groups have estimated that Banzer's regime arrested 3,000 political opponents, killed 200, and tortured 2,000, while others just disappeared.

The coalition of military and civilian personnel that Banzer used for his base of support was never united, and some factions tried to overthrow the rest of the government. Since this was precisely what Banzer did not want, in November 1974 he dismissed all civilians, declaring that henceforth Bolivia would be ruled by the military alone. Not a good move; the government began facing serious problems after that. The economic surge ended, with lower cotton prices causing reduced production of that commodity, and the mines ran at a loss, though mineral prices remained high. Opposition increased, and the regime came under pressure to hold elections, which had last taken place in 1966.

The United States joined those calling for elections after Jimmy Carter became the US president in 1977. At first Banzer announced there would be elections in 1980, but labor unrest grew so bad that he soon moved the date up to 1978. Since the constitution did not allow a sitting president to be re-elected, Banzer picked General Juan Pereda Asbún as his candidate. The polls showed former president Siles Zuazo in the lead, but Pereda won, and the National Electoral Court annulled the elections because of massive fraud from the Pereda camp. Suspecting that Banzer had allowed the elections to fail in order to stay in power, Pereda deposed him in a coup, using the "might makes right" argument to justify taking over since he could not deny that electoral fraud had been committed in his name. While Pereda did promise new elections, that did not secure his position, and four months later he was ousted by another general, David Padilla, who was both embarrassed by events over the past year and suspicious that Pereda did not really intend to call elections. Padilla promised he would only be president until new elections could be held, and they would take place as soon as possible.

It was not an easy road to democracy. The 1979 election failed to produce a winner after multiple ballots; none of the eight candidates could get a majority of votes, nor could Congress break the deadlock. Nevertheless, Padilla stepped down immediately after the 1979 election; at least he was a man of his word. To fill the gap, two acting presidents briefly held office; one of them, Lidia Gueiler Tejada, was Bolivia’s first woman president (November 1979-July 1980). Gueiler arranged another election, no doubt hoping that the third time would be the charm. The still-popular Siles Zuazo won, but before he could be sworn in, General Luis García Meza Tejada (Lidia Gueiler Tejada’s cousin) staged a bloody coup, which drove Siles into exile.

A firm reactionary, García Meza’s goal was to establish an anti-communist government modeled after the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, which would last for the rest of the twentieth century. That may sound bad enough by itself, but there’s more. García Meza had the backing of cocaine traffickers and even a Nazi on the run; Klaus Barbie, the notorious Gestapo officer nicknamed the "Butcher of Lyon," reportedly recruited a mercenary unit, The Newlyweds of Death, so that Bolivia’s rulers could run their regime neo-Nazi style. A wave of arrests, torture and disappearances followed; the only reason García Meza’s regime wasn’t as brutal as Banzer’s was because it only lasted for one year.

The involvement of the cocaine dealers showed how cocaine production and smuggling was becoming a big business in Bolivia, for the same reasons that it was growing in Peru. Cocaine exports reportedly totaled US $850 million during the year that García Meza ruled, twice the value of the country’s legal exports. This also isolated Bolivia diplomatically; e.g., we have seen how the United States preferred right-wing governments, but García Meza’s human rights abuses and drug ties were so blatant that even the Reagan administration wanted nothing to do with him.

García Meza used "coca dollars," money skimmed off the drug trade, to buy the silence and support of other military officers, but they could see how he was mismanaging the economy and giving Bolivia a bad name, so a rebellion among the officers forced him to resign in 1981. He went abroad to play it safe, and was tried in absentia for the crimes of genocide, human rights abuses, treason and armed insurrection. In 1995 he was extradited from Brazil to begin serving a 30-year prison sentence; while incarcerated, he wrote an unapologetic autobiography with the title Yo Dictador ("I the Dictator"). Klaus Barbie also lost his protection from the Bolivian government, and was eventually extradited to France, where he died in prison.

By 1981 a decade of corruption and misrule had left the military demoralized and discredited. Many officers wanted a return to democracy, since they had proven the military could not do a good job managing the country. Two more soldier presidents came and went; then a general strike in September 1982 threatened to become a civil war, and the military realized it was time to get out, election or no election. Because another election would have cost too much, they simply accepted the results of the 1980 election; the elected Congress convened two years late, and Siles Zuazo returned from exile to begin his second term as president on October 10, 1982.

Red Star In the Caribbean

While the political events covered in the previous sections on Cuba were happening, the leaders of the revolution tried to diversify agriculture and industrialize the economy, using socialist methods. A four-year plan was drawn up to achieve these goals through central planning; workers were expected to be motivated by "moral incentives," not material benefits. Unfortunately the revolutionaries were inexperienced in economic matters, so they realized too late that they were making mistakes. Other factors that limited production were the US embargo, which made many parts and supplies unavailable, and the loss of skilled workers, who were in the first wave of refugees fleeing to the United States. And because income was redistributed to the working class, pay raises caused Cubans to demand more food, especially meat, and consumer goods, leading to shortages and rationing because the Cuban economy did not produce enough to meet those demands. The industrialization program was put off indefinitely in 1963, because carrying out its plans proved too difficult. In the agricultural sector, there were excellent sugar harvests for 1960 and 1961, but because much of the cane was not replanted when it grew too old to produce, the sugar harvest of 1962 was the worst since 1955, and crops during the next few years did not fare much better. Also, much of the farm equipment and sugar mills were damaged, and manpower was badly organized.

Because of these failures, a new economic plan was implemented in 1963: concentrate efforts on increasing sugar production, with the goal of producing a ten-million-ton harvest by 1970. If they pulled it off, Cuba would be the world’s largest sugar producer, and the money made from selling that sugar would finance industrial development. But the farms were too underdeveloped to achieve this. The best harvest of the 1960s was 8.5 million tons of sugar; to get that much the revolutionaries almost ruined the sugar industry, and the cane cutters who moved to the cities to take advantage of new jobs had to be brought back for the harvest (which disrupted the urban part of the economy). Finally, private farmers who still owned land were not motivated to grow much sugar cane if they felt the state was going to take their land. By 1969 the revolutionaries realized that they weren’t going to turn the average Cuban into a "new socialist man" anytime soon -- he would not work harder if all he got was recognition that he was a good Marxist -- so in 1969 they introduced material incentives to go with the moral ones.

As in other Communist countries, economic gains were achieved with considerable suffering from the population. Prison camps were established to hold those accused of having "bourgeois" and "counter-revolutionary" values, where they would be "re-educated" and subjected to forced labor. Besides dissidents, those held included homosexuals, unemployed workers (unemployment reappeared in 1970, and was dealt with by passing an anti-loafing law), and starting in the 1980s, those infected with AIDS. The human rights watch group Freedom House regularly lists Cuba as the only country in the western hemisphere that is not even partially free. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, Cuba is one of the worst persecutors of journalists, second only to China in the number of reporters locked up.

Naturally, the poverty and lack of freedom led to widespread discontent. Even when better times seemed to be on the way, the government did not ease up on the political controls or permanent rationing. Hundreds of thousands of upper- and middle-class Cubans responded by fleeing abroad; most of them settled in Miami, Florida, making Miami the first city in the eastern United States with a population that was more than 50% Latino. By 1993, some 1.2 million Cubans (about 10% of the current population) had left the island.(59) They used airplanes when allowed to do so, otherwise they traveled by water, crossing the strait between Cuba and Florida in small boats and rafts. Between 30,000 and 80,000 Cubans are estimated to have died at sea, trying to make the crossing. Those who could claim dual Spanish-Cuban citizenship emigrated to Spain instead. Castro allowed all these folks to go because it was a painless way to get rid of potential opposition to the government, and because he no longer feared an invasion from the outside world. The largest surge in refugees came in 1980; it started when 11,000 Cubans stormed the Peruvian embassy in Havana, demanding asylum. To defuse the situation, the government opened the port of Mariel, and for the next six months it did not stop any boats from leaving there; Castro also emptied the prisons and mental institutions, in effect ridding the country of all its misfits. By the time the Mariel Boatlift was over, 125,000 Cubans had made the crossing to Florida (see also this footnote in my North American history).

A fun bit of Photoshop work, showing Fidel Castro as a refugee.

Cuba never lost interest in spreading its revolution abroad, even after Che Guevara’s attempts to do it resulted in his death. It supported the Sandinista movement in Nicaragua, which imitated the Cuban revolutionaries well enough to bring down the Somoza dictatorship in 1979. However, Africa was the continent that saw the most Cuban activity. Besides Che’s involvement in the Congo, Cuba supported liberation movements or leftist governments in Algeria, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, and ten other African nations. Cuba was especially active in the Angolan Civil War (1975-88), and the Ethiopian-Somali war (1977-78), committing thousands of soldiers to those conflicts. At that stage, the Cubans played a role for the Soviet Union that was very similar to the role Nepal’s Gurkhas have played for Britain.(60) For other parts of the Third World, Cuba sent 16,000 doctors, teachers, construction engineers, agronomists, economists and other specialists, in a Cuban version of the Peace Corps.(61) This civilian aid brought much-needed money to Cuba from countries that could afford to pay, and was given free to those countries that couldn’t pay.

The Perón Sequel and the "Dirty War"

When the military decided to let the Peronistas back into Argentine politics, they must have been hoping that the other political parties would join together to keep the Peronistas from winning. Instead, the Peronista candidate, Dr. Hector Campora, was elected president, and Juan Perón’s followers also secured strong majorities in both houses of Congress. Campora was just a stand-in for Perón, and everybody knew it; in July 1973, two months after taking office, Campora resigned, forcing new elections. By this time all the restrictions that had been placed on Perón were gone, and he was back in the country, so he ran for president again, won a resounding victory, and began his new term in October, with his third wife, Maria Estela Isabel Martinez de Perón, as vice president.

You probably know that most movie sequels are not as good as the original movies they are based on, and likewise, anyone who expected Perón’s second presidency to be like the first was in for a disappointment. At first the economy got a major boost from high world market prices for beef and grain, but that ended when Argentina got hit by the shock of rising oil prices. And with Perón now seventy-eight years old, he was only half the man he used to be. Furthermore, Evita was no longer around to inspire the crowds, and Isabel was no substitute. Perón spent much of his term being ill, and on July 1, 1974, not quite nine months after taking office, a heart attack finished him off.

Isabel Perón promptly moved into her husband’s job, though she did not have the political skills for it. In fact, the only thing she had going for her was her last name. The next two years saw the GDP shrink, and inflation rose again. There were also intraparty struggles between right-wing and left-wing Peronistas, and still more terrorism, especially from the Montoneros and the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (People’s Revolutionary Army, or ERP, a Marxist-Leninist movement).

Isabel’s closest advisor was José López Rega, the minister of social welfare, leader of the right-wing Peronistas, and a virtual prime minister after Perón’s death. Ms. Perón and López Rega shared a common interest in all manner of occult practices; he also supported dissident Catholic groups. His solution to the guerrilla problem was to fight fire with fire; he created a death squad called the Triple A (Alianza Argentina Anticomunista), to go after the revolutionary groups, especially communist ones. Lopez Rega was forced to resign in 1975, when it was discovered he was killing his enemies. By then, though, his AAA had succeeded in driving the Montoneros underground. Isabel quickly appointed him ambassador to Spain, figuring that someone like him would be safest in a Fascist country (the dictatorship of Francisco Franco was in its last months).

On March 24, 1976, the commander of the army, General Jorge Rafael Vadela, seized power in a bloodless coup. The junta which ruled Argentina for the next seven years called its plan for the country the National Reorganization Process, but arguably it was the most violent government in Argentine history. Vadela’s top priority was to crush the guerrillas and restore order, and in what was later called the "Dirty War" (Guerra Sucia), security forces went around arresting, torturing, raping and killing anyone on their hit list; this included not only guerrillas but also political dissidents, trade unionists, students, journalists, Marxists, left-wing Peronistas, and alleged sympathizers of the other groups. Consequently Argentina became the main battleground of "Operation Condor," the CIA-backed war against communists in South America.

A lot of the victims were never accounted for, but simply disappeared (and are presumed dead). Before the 1976 coup, the AAA had reportedly killed 1,500 leftists, while estimates of those killed and "disappeared" between 1976 and 1983 range from 9,089 to 30,000. The guerrillas in turn killed some 6,000 soldiers, police and civilians.

It seemed at times that the internal conflict wasn’t enough to satisfy the junta’s appetite for a fight, because they also revived an old territorial dispute with Chile. This was the Beagle Channel Dispute, which involved three small islands (Picton, Lennox and Nueva) in the Beagle Channel, on the south side of Tierra del Fuego. This was supposedly settled in Chile’s favor when an 1881 treaty defined the Argentine-Chilean border, but in 1904 Argentina questioned where the border was actually supposed to run, laying claim to the three islands. Maybe Ushuaia wasn’t far enough south for the Argentinians (see Chapter 2, footnote #19). That was where the issue stood until Chile and Argentina agreed to submit the Beagle Channel issue to international arbitration, and in 1977 that court ruled the islands belonged to Chile, too. One year later General Vadela declared the arbitration null and launched an invasion of the islands, Operation Soberania. It ended a few hours later, before the forces of the two sides met, because Pope John Paul II intervened and offered to mediate the dispute. Both countries agreed to let the Vatican decide, and again the ruling was that the islands belonged to Chile. Naturally Chile accepted this result and Argentina rejected it, but other events made sure it would stick. In 1984, after Argentina lost the Falklands War (see the next section) and its junta was gone, the two countries signed a treaty of peace and friendship that officially ended the dispute.

Panama: The Canal Becomes Truly Panamanian

As noted in the previous chapter, the people of Panama were not happy with their twentieth century status, and it is easy to understand why. How would you feel if a foreign power owned your country’s most important asset (namely the Panama Canal), and their ownership of that asset split your country in two? Within the Canal Zone lived 40,000 US citizens (mostly troops with their families) and 7,500 Panamanians. In addition, Panama depended on the United States for its defense, and much of its commerce. Finally, the nationalization of the Suez Canal by Egypt made Panamanians hopeful that they could take control over the Canal Zone, leading to considerable unrest in the nearby cities. By 1960, Panama’s leadership feared that because of student and labor riots, it would soon have a revolution on its hands, until the United States announced that it would allow the Panama flag to fly in the Canal Zone. Thus, Ernesto de la Guardia, the last president from the National Patriotic Coalition (CPN), became the first postwar president to finish a four-year term in office. He was succeeded by two presidents from the National Liberal Party, Roberto Francisco Chiari Remón (1960-64) and Marco Aurelio Robles (1964-68).

Having the Panama flag in the Canal Zone did not defuse tensions for long. The US Department of State wanted the flag there, but the armed forces didn’t, so for a while they compromised by flying the Panama flag in just one location, next to an American flag. The US government subsequently agreed to allow the Panama flag in more spots, but many US citizens in the Canal Zone refused to raise any flag besides the Stars & Stripes. In January 1964 a group of nearly 200 Panamanians marched into the Canal Zone with their flag, the flag was torn in the fight that followed, and thousands more Panamanians stormed the border fence, causing a riot that lasted for three days, killed 27, injured 500, and did more than US$2 million in property damage.(62) US-Panamanian relations were temporarily severed, and bad feelings smoldered for most of the year, until US President Johnson announced he would consider plans to dig a sea-level canal like the one the French had tried in the 1880s(63), and negotiate a new treaty for the existing canal.

The 1968 election saw the return of an erratic but familiar face: Arnulfo Arias, who had been elected in 1940 and 1949. Military coups kept Arias from finishing his term the other times, and his third presidency was even shorter, lasting only ten days. One of the first things he did upon taking office was announce that he would change the leadership of the National Guard, so the Guard acted before he could, forcing Arias, eight of his ministers and twenty-four members of the National Assembly to flee to the Canal Zone. While another president was appointed the official head of state, real power was now concentrated in a junta led by a National Guard general, Omar Efraín Torrijos Herrera.

Unlike most of the military dictators mentioned in this work, Torrijos got along with the Democrats in Washington, but not the Republicans.(64) This was because his political leanings were left of center; e.g., he got along well with Cuba, launched social and economic programs, and redistributed 700,000 hectares of farmland to poor families. Yet while he was corrupt and no friend of democracy (at the same time he fought a guerrilla movement that was trying to bring back Arnulfo Arias), he endeared himself with the poor, who had been neglected by previous Panamanian leaders; sometimes he called his style of rule a "dictatorship with a heart." And unlike the rulers of Cuba and Nicaragua, Torrijos knew when to stop; he was always careful to say he was a populist, not a Marxist.

Today Torrijos is chiefly remembered as the man who got the Panama Canal from the Americans. However, he took over near the end of the Johnson presidency, and Johnson’s Republican successors weren’t willing to give up the Canal, because they still saw it as vital to US security.(65) Negotiations did take place during the Nixon and Ford administrations, discussing issues like paying more rent to Panama, and when (or even if) US rule over the Canal Zone would end, but they failed to reached agreement on anything important. For Torrijos, results had to wait until another Democrat, Jimmy Carter, came to the White House. Carter showed that Panama was one of his priorities when he put Sol Linowitz, the former US ambassador to the OAS, on the US negotiating team, and rather than insist on a perpetual military presence in the region, he let it be known he would accept a promise to keep the Canal open and neutral after Panama took control of it. In the summer of 1977, both sides reached agreement, and Torrijos flew to Washington to sign two new treaties with Carter, one for the Canal, the other to define the future role of the US military in Panama. The first treaty voided all previous agreements concerning the Canal, and announced the Canal would come under Panamanian rule on December 31, 1999.

Of course the Canal treaty would only go into effect if the US Senate ratified it. Selling the treaty would be an uphill battle; probably less than half of the American people at the time supported it. What the United States did not know was that Torrijos had another plan, which he would implement if Carter failed to get two thirds of the senators to vote for the treaty. The idea behind the plan was simply that if Panama could not have the Canal, no one else would have it, either. Called Huele a Quemado ("I can smell burning"), the plan would have Panamanian soldiers infiltrate the Canal Zone, sabotage the locks, the Gatun Lake Dam, and the locomotives used to pull ships through the locks, and render the Canal inoperable. The operation would have been led by the chief of staff for intelligence, Colonel Manuel Antonio Noriega Moreno; we’ll be hearing more from him soon. Torrijos knew the Americans in such a case would probably take back the Canal in a few days, but then they would be stuck in another jungle war against a communist guerrilla movement, much like the war the US had so recently fought -- and lost -- in Vietnam. Fortunately, Torrijos did not have to resort to this "Plan B." Carter was more successful here than he would be with the economy and Iran; he made enough deals with senators to get the votes he needed to pass both treaties. And with the transfer of the Canal scheduled for twenty-two years in the future, the United States would forget the whole business; when the transfer actually took place, most Americans did not notice (they were paying more attention to the Y2K crisis).

The Dominican Republic: The Balaguer Era

When the period covered by this chapter began, El Jefe, Rafael L. Trujillo, had been running the Dominican Republic for almost thirty years. Like other right-wing dictators in Latin America, he got as far as he did with the support of Washington, but over the years he committed many harsh acts and some stupid ones, and they all added up. By the late 1950s the Eisenhower administration was tired of him, and regarded him the same way as Fulgencio Batista -- a Third World leader who had outlasted his usefulness. Trujillo reacted by going rogue; he started sending hit men against perceived enemies abroad. Understandably, he saw Rómulo Betancourt, the new president of Venezuela, as the biggest threat of all, because Betancourt hated tyranny with a Jeffersonian passion. In June 1960, agents of Trujillo tried to assassinate Betancourt by detonating a bomb as his car went by. The blast killed Betancourt’s chief of security, seriously injured his driver, and badly burned Betancourt’s hands, but he survived, and photos showed the results to an outraged world. The OAS imposed sanctions against the Dominican Republic because of this atrocity, while the US closed its embassy and withdrew its ambassador. At the time, Trujillo’s brother Hector was acting as president, so the dictator, thinking the outside world would be more sympathetic if somebody besides a relative held that job, asked Hector to resign and elevated the vice president, Joaquín Antonio Balaguer Ricardo, to take his place.

However, the failed assassination attempt on Betancourt did not persuade Trujillo to stop making trouble abroad. In Rome, Pope John XXIII also suggested that it was time for the Dominican Republic to get new leadership, and the churches in the Dominican Republic added a prayer during mass for "all those who are suffering in the prisons of the country and their afflicted families." Naturally Trujillo saw this as an insult, but instead of using brute force, he first tried ridicule, then black magic. For the ridicule, he sent out a thousand fake invitations to a reception hosted by Archbishop Lino Zanini; then after the guests arrived, prostitutes came out to dance and sing obscene songs, while Trujillo's men dropped stink bombs in the place. Meanwhile Trujillo tried to mock the pope, by calling him "Juan Pedejo" (John the Jerk). Surprise! Those tactics did not turn the people against the Church. For his next trick (literally), he recruited a one-armed sorceror named Rodolfo Paradas Veloz, and appointed him ambassador to the Vatican. This fellow supposedly had the power to curse people with bad luck, and Trujillo thought he could kill the pope if he got close enough to him. Well, the sorceror did meet with the pope (photographs of the meeting exist), but nothing bad happened to His Holiness. Apparently the pope's supernatural powers were stronger, and unlike the sorceror, he had two good hands! And judging from what happened in the following year, you could say that the black magic bounced off the pope and hit Trujillo instead.

In November 1960 Trujillo offended everyone in the country who wasn’t offended already, by ordering the assassination of the Mirabal sisters, three women who were known anti-Trujillo activists.(66) Six months later, on May 30, 1961, Trujillo’s blue Chevrolet was ambushed on a road in the countryside, by seven soldiers who shot and killed him.(67) But the soldiers failed to seize power from the Trujillo family, who over the next six months hunted down and executed all but two of them.(68) Still, the international sanctions continued, and the people, having no memory of the poverty and instability that afflicted the country before the Trujillo era, began demanding freedom and a more equal redistribution of wealth. Trujillo’s son Ramfis and two of the late dictator’s brothers argued over how much freedom they could allow; then in November, when it looked like the country would descend into civil war between conservatives and liberals, the rest of the Trujillos went into exile. The sanctions were lifted in January 1962, but by then the situation for Balaguer had become so precarious that he resigned in the same month. Don’t worry -- he’ll be back!

A caretaker government ruled for the rest of 1962, and then Juan Bosch, a scholar and poet who had founded the opposition Partido Revolucionario Dominicano (Dominican Revolutionary Party, or PRD), during the Trujillo years, was elected president. However he was a leftist, and his platform -- which called for land redistribution, nationalizing some foreign holdings, and bringing the military under civilian control -- led to fears among the military, the Catholic Church and the upper class that the Dominican Republic would soon go the way of Cuba. In September 1963 Colonel Elias Wessin threw out Bosch in a coup, replacing him with a three-man junta; Bosch went into exile on nearby Puerto Rico. Unfortunately, even the armed forces could not restore order; in April 1965 there was another coup; this time the National Palace was taken by officers called the Constitutionalists, who wanted Bosch back. Conservative officers, calling themselves the Loyalists, struck back with tanks and aircraft against Santo Domingo, and requested US military intervention.

For the second time, the Yankees occupied the Dominican Republic; officially the troops were there to protect US citizens and to evacuate all foreign nationals. The first US forces arrived at the end of April 1965, and eventually President Johnson committed 23,000 troops to "Operation Power Pack." Because they still controlled Congress, the Constitutionalists elected the second coup leader, Colonel Francisco Caamaño, as their president, while US officials swore in General Imbert (see the previous footnote) as president of the "Government of National Reconstruction." In the second half of May Imbert eliminated most pockets of Constiutionalist resistance through "Operation Lipieza" (Cleanup), the OAS brought in peacekeeping troops from its member nations, and the last fighting ended on the last day of August. Total casualties amounted to 44 Americans, six Brazilians, five Paraguayans and 6,000-10,000 Dominicans.

New elections were held in June 1966, and Joaquin Balaguer, now head of the Social Christian Reformist Party (PRSC), regained the presidency. After that order returned, the American troops left the country by September, and a new constitution was signed in November. This would be Balaguer’s second and longest term, lasting for twelve years (1966-78).

Balaguer inherited a nation beaten down by decades of misrule, to the point that if those in charge just behaved themselves, life had to get better. He did that by ordering the construction of buildings like schools, hospitals, dams and roads. As the former right-hand man of Trujillo, it was natural for Balaguer to rule in an authoritarian way. Balaguer sometimes seized control of opposition newspapers, and his opponents were sometimes imprisoned or killed, but overall, he abused his power far less than Trujillo had. For the 1970 election he had no trouble winning another term because the opposition was fragmented, and when he changed the election rules in 1974, the opposition refused to take part in the campaign, allowing him to get re-elected again.

Balaguer did not meddle with local businesses and invited foreign investment, so the sugar industry prospered and tourism boomed under his administration. This led to an excellent economic growth rate; e.g., the GDP grew by an average of 9.4 percent every year between 1970 and 1975. The drawback to this growth was that economic growth also caused inflation, the new wealth was concentrated in the hands of a few new millionaires, and everyone else just got poorer. Those poor who demanded that something be done about this were called communists and treated as enemies of the state. But Balaguer could not keep a lid on the discontent forever, as the 1978 election showed. When election returns showed the PRD candidate, a rancher named Antonio Guzmán Fernández, clearly in the lead, Balaguer ordered the military to storm the election center, stop the vote counting, and destroy the ballot boxes; then he declared himself the winner. US President Jimmy Carter refused to accept Balaguer's claim, and by threatening to cut off foreign aid, he got Balaguer to back down. This was the first time in the Dominican Republic that power between presidents had been transferred peacefully, by ballots instead of by bullets.

As Guzmán was sworn in, the country went into a recession. Sugar prices declined, oil prices rose, and unemployment and inflation remained high. Many Dominicans escaped these problems by emigrating to the United States; their favorite destination was New York, where they could join the large Puerto Rican community there.(69) Meanwhile in Santo Domingo, Guzmán had some good ideas for improving the economy, but Congress, largely filled with members of Balaguer’s party, kept him from implementing most of them.(70) By 1982 he was so frustrated that he committed suicide, shooting himself in the head just forty-three days before his term ended.

In the 1982 election Balaguer ran again, and lost to the PRD candidate again; the PRD also gained a majority in both houses of Congress. The next president, José Salvador Omar Jorge Blanco, did not do much better than Guzmán; the economic austerity program he introduced, with the approval of the International Monetary Fund, caused sharp price increases, leading to riots that caused several deaths (April 1984). When the 1986 election came around the voters, instead of giving the PRD a third chance, voted in the ever-running Balaguer, though he was now eighty years old and nearly blind from glaucoma. After Jorge Blanco’s term ended, he was accused of illegal purchases of equipment for the armed forces, but was allowed to leave for the United States to be treated for a heart condition.

The third time around, Balaguer ran a somewhat more tolerant administration, and tried to stimulate the economy through a public works construction program. His most impressive project was the Faro a Colón (Columbus Lighthouse), a $200 million, ten-story cross-shaped building that serves as a museum to Christopher Columbus, a mausoleum for his remains (see Chapter 2, footnote #10), and a lighthouse; the lighthouse part of the monument drains Santo Domingo of electricity when it is turned on. The whole thing was completed in time for the 500-year anniversary of the discovery of the New World, in 1992. In the style of the Trujillo era, the Faro a Colón and other projects got a lot of publicity from the government-controlled media, and lavish ribbon-cutting ceremonies. But despite Balaguer’s efforts, inflation continued to be a problem, the value of the peso tumbled, there were problems in delivering basic utilities (water, transportation, and as noted, electricity), and a paralyzing nationwide strike took place in June 1989.

The 1990 election was a rematch from the 1960s: Juan Bosch vs. Joaquin Balaguer. Balaguer won by a slim margin of 22,000 votes, out of 1.9 million cast. Some suspected fraud, but the charges were not serious enough for a recount or investigation.

For the election of 1994, Balaguer played the race card; he frequently mentioned the Haitian ancestry of his opponent, José Francisco Peña, and predicted that Peña would try to unite the country with Haiti if elected. The mean-spirited campaign appeared to work, because Balaguer claimed on Election Day that he had won by only 30,000 votes. However, this time allegations that the election had been stolen were more credible; for one thing, it was discovered that the names of 200,000 people had been removed from the lists of voters. Amid threats of a general strike, and pressure from the US, Balaguer agreed to a compromise: he would cut his term short to two years, and he would not be a candidate in the 1996 election.

Balaguer's vice president, Jacinto Peynado, ran as the official party candidate in the 1996 election and got just 15 percent of the vote. That eliminated him from the race, because only the candidates that came in first and second place qualified for the runoff. The top two vote-getters were José Francisco Peña, who was running again, and the candidate from the centrist Dominican Liberation Party (PLD), a forty-two-year-old lawyer named Leonel Antonio Fernández Reyna. Balaguer and his old rival Bosch both threw their support behind Fernández, to keep Peña from winning. Fernández won, and then tried to implement too much change too quickly. In a purge that shocked the nation, Fernández "retired" two dozen generals, tried to have the defense minister submit to questioning by the civilian attorney general, and then fired the defense minister on a charge of insubordination -- all in one week. His four-year term (1996-2000) also saw strong economic growth and an end to the Dominican Republic’s status of partial isolationism, which had now been going on for more than six decades. In addition, there were promising reductions in the rates of inflation, unemployment and illiteracy. The main problems left to tackle were the chronic poverty and corruption.

Balaguer ran for the ninth time in 2000, but because he was obviously too old and ailing, he received a mere 23 percent of the vote, meaning he would not go to the runoff, either. Indeed, it was only Balaguer’s death two years later, at the age of 95, that kept him from running once more after that. He had been on the Dominican Republic’s political scene for more than forty years, longer than even Trujillo. The winner in 2000 was the PRD candidate, a former tobacco farmer named Rafael Hipólito Mejía Domínguez.

Mejía’s presidency is controversial today, due the financial disaster that occurred during his term, and his response to it. The first thing he did after taking office was to cut spending and raise fuel prices -- not exactly what he had promised during the election. Then came the September 11 terrorist attacks on the United States(71), and because of the recession that followed on the mainland, the tourist industry suffered a slump, and Dominicans living in the US had less money to send back (see footnote #69). Most upsetting of all were the electricity shortages and the failures of three major banks. Mejía acted in time to keep account holders in those banks from losing their money, but the resulting increase in the national debt devalued the peso, so the exchange rate went from 16 pesos = 1 US dollar to 60 = 1 dollar. Since then, the peso has never recovered to its previous value, and usually trades around 40 to the dollar today. On the other hand, Mejía introduced a Social Security-type pension (the first for the country). Finally, he got both houses of Congress to amend the constitution so that the president could run immediately for re-election after serving a term, but because he wasn’t re-elected, he wasn’t the first to take advantage of this change. For 2004, the voters chose to give Leonel Fernández another chance.

The second time around, Fernández oversaw the economy’s recovery, allowing him to easily win the next election in 2008. Other issues, however, were left unsolved, like corruption, tensions with Haiti, and an unpopular patronage system that has stuck around from the days of Trujillo and Balaguer. As a local sociologist, José Oviedo, explained it, "The country trusts him with the economy, but he does not seem to pay that much attention to social issues."(72) In 2012 Fernández was succeeded by another president from the PLD, Danilo Medina Sánchez. During the next few years we will see if Medina can keep the gains made by Fernández, and tackle the unfinished business left by all his predecessors.

The Guianas/Guyanas: South America’s Neglected Corner

|

|

|

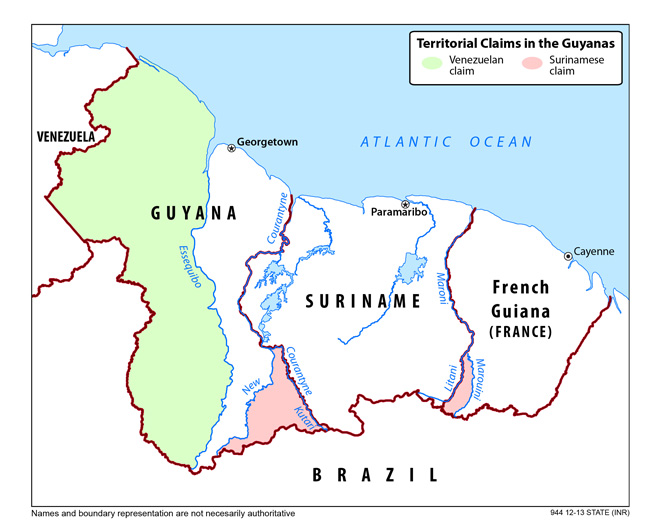

So far in this narrative we have barely mentioned the part of South America between the mouths of the Orinoco and Amazon Rivers, and alas, we do not have much more to say about it now. The lands we used to call the Guianas (now usually spelled Guyanas, except for the French part), were bypassed by the two Iberian powers; Spain and Portugal weren’t sure which side of the 1494 Tordesillas treaty line the land was on, and they were only interested in the place when they thought El Dorado might be found there. Also the region was isolated physically from the rest of South America, by the Amazon jungle and the Guiana Highlands.(73)

When France, the Netherlands and England entered the empire-building game around 1600, none of them were strong enough to take away Spanish colonies, so they settled for colonies in places that Spain and Portugal had not settled already, hence their outposts in the Guianas. The population of the region is mostly black and (Asiatic) Indian; they are called Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese respectively. The languages spoken here are those of the mother countries, plus Guyanese Creole, Hindi, Javanese and some Native American dialects -- but almost nobody speaks Spanish or Portuguese. Consequently, from a demographic and political standpoint, this region should be seen as part of the Caribbean, though it is on the mainland.

Even today, the region is underpopulated. Three quarters of the US states, including West Virginia and Nebraska, have more people than the combined population of the Guianas (800,000 in Guyana, 600,000 in Suriname, and a quarter million in French Guiana). You don’t get many news stories from places that don’t have many people. Indeed, in the author’s lifetime, the only event in the Guianas that made international headlines was the 1978 Jonestown Massacre (see below).

French Guiana

A new era began for French Guiana in 1964 when French President Charles de Gaulle announced that France would build its space center in the town of Kourou. Rocket science decided that location; it is a known fact that rockets launched from near the equator need less fuel to go into orbit than rockets launched from high latitudes. That is why the United States chose to build its main space center at Cape Canaveral in Florida. Kourou does even better, with a latitude of only 5° N. A wave of scientists, engineers, technicians, service people and security forces came to the new Guiana Space Center, modernizing Kourou and giving a boost to the local economy. Since the Space Center was completed in 1968, it has served as the launching pad for the European Space Agency.

Because of the low population, French Guiana has never had an economy strong enough to stand on its own. Some food is grown in the gardens of Hmong refugees from Laos, who were resettled here in the 1970s, but most consumer goods and energy have to be imported. The other industries are timber, fishing, and a bit of tourism and mining (for gold). Cynics have suggested that France discourages the development of any business besides that, to keep the colony from demanding independence. Over the years, Paris has also provided billions in subsidies, which allow a comfortable lifestyle in coastal communities like Cayenne and Kourou, anyway, while the villages and Indian and Maroon tribes in the interior remain dirt poor. Calls for autonomy began to be heard in the last decades of the twentieth century, leading to violent protests in 1996, 1997 and 2000. Still, it is estimated that only a small portion of French Guiana’s population, perhaps five percent, wants complete independence; the rest don’t want to lose those subsidies from the French government.(74)

Guyana

Because they have more people, the other two Guianas are further along politically. Both had self-government by the end of the 1950s; we saw in the previous chapter how the British grew alarmed when it looked like the Guyanese would choose communism for themselves. By the time they gave self-government another chance, in 1957, the colony was polarized between the Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese.(75) This has been one of the two facts of Guyanese politics since independence; the other is the tendency for strong leaders to dominate each faction. The first strong leaders were Linden Forbes Burnham (1923-85) for the Afro-Guyanese, and Cheddi Jagan (1918-97) for the Indo-Guyanese. Indeed, Jagan would have become the first independent prime minister if Britain hadn’t delayed both autonomy and independence; it was his party, the People's Progressive Party (PPP), which won both the 1953 and 1957 elections.