| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Concise History of Southeast Asia

Chapter 4: NATIONALISM TRIUMPHANT

1941 to 1957

This chapter covers the following topics:

Japan Strikes

The outbreak of World War II in Europe presented Japan with the opportunity to make enormous gains. When France and the Netherlands fell to Nazi Germany in the spring of 1940, their Southeast Asian colonies were left unprotected. The British colonies were hardly better off, since Britain was fighting for its life at home. The fourth colonial power in the region, the United States, was at peace, so the U.S. armed forces in the Philippines were unprepared for anything that might happen there. In short, none of these countries could keep their Southeast Asian colonies from falling into Japanese hands; they were just too far away.

Japan began to act in August 1940 by moving into the northern half of French Indochina (Laos and North Vietnam). The Vichy French government, powerless to resist, acknowledged that Japan was the supreme power in Asia. The Japanese occupied the French military bases and redirected Indochina's raw materials toward Tokyo, but they left the French administration intact. In the summer of 1941 the rest of Indochina was occupied, except for a few pieces of Cambodia and Laos, which were given to Thailand. The United States protested Japanese expansion, and Japan prepared for war.

Malaya and Singapore

Ten army divisions were assigned the task of conquering Southeast Asia. Compared with the hundreds of German and Soviet divisions on the Russian front, this seems like a piddling force, but with the element of surprise, they would be enough. The Japanese strategy called for a series of lightning strikes upon multiple targets on December 7 & 8, 1941. Within hours of the "day of infamy" at Pearl Harbor, other Japanese air strikes were being launched against Malaya, Hong Kong, Guam, the Philippines, Wake and Midway Islands. Thailand put up a token resistance for a few hours, and then declared itself a member of the Axis. This did not have the expected effect, though, because a rival of Thai Premier Phibun Songgram, Pridi Phanomyong, declared himself to be on the side of the Allies, forming an anti-Japanese political party called the Free Thai. The Thai embassy in Washington recognized the Free Thai as the legitimate government of Thailand; so did the United States, which simply ignored Phibun's declaration of war against the U.S. Meanwhile Japanese troops passed through Thailand to the Burmese frontier, more troops were transported by boat from China to landing spots on both sides of the Thai-Malay border, and still more troops landed on Luzon in the northern Philippines. Another force landed at Davao City on Mindanao, not to conquer the big southern island, but to secure an advance base on the way to Indonesia.

The Japanese offensives proceeded with a speed and rate of success that astonished everybody, including the Japanese themselves. Britain was expecting trouble before the fighting started and had moved the Royal Navy's two mightiest battleships, the HMS Prince of Wales and the HMS Repulse, to Singapore. Past experience had told them that capital ships were the key to controlling the sea, and whoever controlled the sea would eventually win on land as well. When these ships left Singapore with four destroyer escorts to engage the Japanese ships transporting troops to Malaya, the commanding admiral had followed all the rules of the book--but the book was out of date. Japanese torpedo-bombers sank both battleships in two and a half hours. With that, a new rule was written for naval warfare: "Even the greatest warships are vulnerable to attacks from the air if they do not have planes of their own to protect them."

On land, the Malay peninsula was taken with almost no resistance; the two Indian divisions that had guarded Malaya's frontier didn't last long, and neither did the British and the Australian division that were sent in as reinforcements. In fact, the Japanese advanced to Singapore so quickly that they outran their supplies of food, fuel, and ammunition.

With its 15-inch guns facing the sea, Singapore was considered an impregnable fortress. On the last day of January, the British blew up the causeway linking Singapore to the mainland; they thought they were now safe because the Malayan side of the Strait of Johore was covered with jungle and swamps, and the Japanese could not get their tanks and artillery through that. Instead, the Japanese attacked with only footsoldiers, going through the jungle with bicycles and crossing the strait with inflatable boats. With no tanks and few planes of their own, and realizing that their big guns were pointing in the wrong direction, the British were too shocked to fight to the end, and when the city reservoirs were captured, civilian suffering became intolerable. On February 15, 1942, 130,000 British soldiers surrendered to 30,000 Japanese; it was the worst defeat in British history.

The British commander, Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, carries the Union Jack at the surrender of Singapore.

The Philippines, Act 1

At first the Japanese had an easy time of it in the Philippines as well, but unlike other Westerners, the Americans had not worn out their welcome, so there was a genuine fondness for them among the Filipinos. When the attack on Luzon came, the American commander, General Douglas MacArthur, was taken completely by surprise. Most of the American planes were destroyed on the ground in the first attack. Landing on the northern and southeastern ends of the island, they converged on Manila. The invaders were surprisingly few--two divisions divided between eight beaches, of which the largest force was regiment-sized--and they faced eleven divisions of American and Filipino troops. However, the Japanese had more planes, and their troops had better training and equipment, so wherever they met the defenders, they pushed them back. On December 23 MacArthur abandoned Manila, and the Japanese entered the city on January 2, 1942. The Americans and Filipinos withdrew to the Bataan peninsula, at the entrance to Manila Bay, and to the nearby island of Corregidor. As long as these places remained in Allied hands, the Japanese could not use Manila's superb harbor for shipping. It looked like the campaign had reached its mopping up phase, so the Japanese High Command pulled out one of the two divisions on Luzon and sent it to Java, to speed up the conquest of Indonesia.

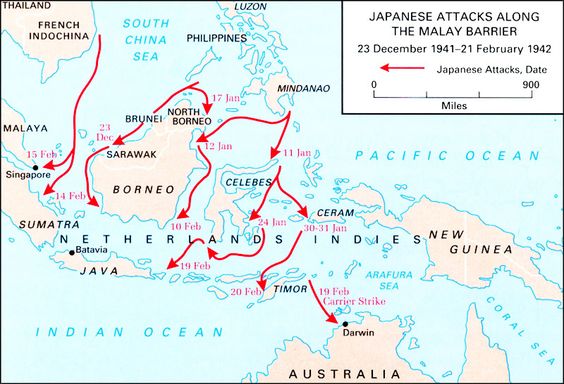

Java

Speaking of Indonesia, the Allies knew these resource-rich islands would be the next target, if they could not stop the Japanese in Malaya or the Philippines. In mid-December 1941 they occupied the Portuguese half of Timor, to keep it out of Japanese hands as well (Portugal was a neutral nation for all of World War II). Then on January 11, 1942, the Japanese arrived, with troop landings on Borneo and Sulawesi. Because more than a year had gone by since the fall of the Netherlands, there were virtually no troops or defenses on the northern layer of islands: Borneo, Sulawesi, and the Moluccas. But then, most of the population was on the southern layer of islands; the first landings on Sumatra, Java, Bali and Timor were made in mid-February. By the beginning of March there were at least a division of troops on each end of Java. The Allies scraped up all the cruisers and destroyers they could find to defend the archipelago, but they were sunk in a three-day battle in the Java Sea (February 27-March 1). With the surrender of Java on March 8, all of the Dutch East Indies (and Portuguese Timor) passed under Japanese occupation.

The Retreat Through Burma

Burma was also on the list of places the Japanese wanted. It was another resource-rich territory (rubies, teakwood, rice and oil), but the Japanese were chiefly interested in it as a buffer zone for the rest of their Southeast Asian holdings. It also had China's last supply line from the outside world, the Burma Road. The two Japanese divisions on the Thai-Burmese frontier waited until mid-January before entering Burma, to make sure they would not be needed in Malaya. Their advance was slowed down by jungles and the size of the territory that was to be occupied, but once again the Japanese won every battle. Opposing them was one Indian division which they outflanked and demolished; then they took Yangon on March 8. The rest of the British force began a very long retreat northward. It was probably the most diverse Allied army at this point in the war: one British, one Burmese, and one Indian division, plus several Chinese units with the combined strength of one more division. Together they tried to build a defensive line in central Burma, between Prome and Toungoo, but the Japanese brought in reinforcements--one division from Malaya and a newly raised division from Japan; at the end of March they forced the Allies to retreat again. By early May the Japanese had overrun central Burma and cut the Burma Road. The Chinese withdrew toward China's Yunnan province, and the last British and Indian soldiers escaped into India, just ahead of the monsoon season as well as the Japanese. India itself was threatened afterwards, when Japanese forces took the Andaman Islands and bombed Sri Lanka, but then the Japanese suddenly turned eastward and sent their ships to the Coral Sea, leaving India in Allied hands.

The Philippines, Act 2

By the time the Japanese finished conquering Burma, the fighting was over in the Philippines as well. Transferring a Japanese division from the Philippines to Java in the middle of the campaign was a good strategic move, but it meant that the single division left on Luzon was so badly outnumbered that it could not push into the Bataan peninsula by itself. The American and Filipino defenders made excellent use of the local mountains, jungles and swamps, and General MacArthur became the biggest American war hero to date. Consequently the US government decided MacArthur was too valuable to be left in a place where he might be killed or captured, and President Roosevelt ordered him to escape. On March 12, MacArthur and his family rode PT boats to Mindanao, and then flew by plane to Australia. From Australia he broadcast a radio message back to the Philippines that promised, "I shall return," and then he took charge of the American and Australian forces being assembled to defend the southwest Pacific.

As successful as the defense of Bataan had been, the final outcome was never in doubt, because the United States could not get reinforcements or supplies in; the defenders now suffered from hunger, sickness, and a shortage of everything. The Japanese, by contrast, brought in reinforcements to build up their strength to three divisions. They finally broke through the defenses in early April, and the Bataan garrison surrendered on April 9. 76,000 defenders were taken prisoner, and led away on a 65-mile hike that became one of the war's most notorious incidents, the Bataan Death March. Corregidor was a heavily fortified island, so it held out another twenty-seven days, ultimately flying the white flag on May 6. The central and southern islands of the Philippines, mostly ignored while both sides were concentrating their attention on Luzon, formally surrendered to Japan on May 10. That ended organized resistance, but some Americans and Filipinos took to the mountains, from which they launched guerrilla raids from time to time.

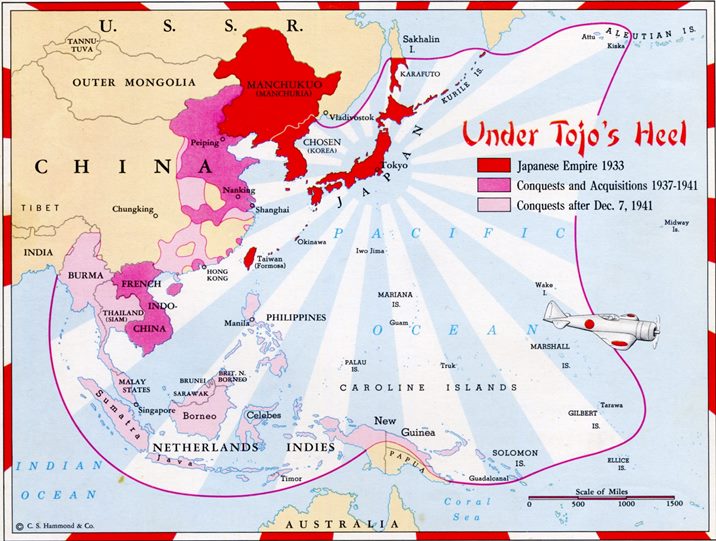

For the Americans and Filipinos, defeat was not as humiliating as it had been for the British at Singapore, because they had fought back for as long as humanly possible. The Japanese had expected to conquer the Philippines in two months, but it had taken them five months to gain control over the archipelago. Overall the Southeast Asian campaigns had gone well for the Japanese. They had lost 25,000 men, a small casualty count for the size of the area they had fought in, and no ship larger than a destroyer had been sunk. Only in the Philippines had their movements not been completed ahead of schedule. Aside from Thailand, which had become a vassal state, all of Southeast Asia was now ruled by one government.

The Japanese Empire, 1933 to 1944.

Life Under the Japanese

At first, many Southeast Asians welcomed the Japanese conquest, seeing it as liberation from Western rule. Japanese propaganda tried to get their support, using slogans like "Asia for the Asiatics," and the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere." Japan also followed a selective approach when dealing with specific ethnic groups. In Burma and Thailand, for example, the Japanese made sure that the natives knew they were devout Buddhists. To Java went Japanese converts to Islam, who encouraged study of the Koran, denounced the Dutch as heretics, and referred to Emperor Hirohito as "caliph." In Thailand, Malaya and Java, the invaders became the enemy of the exploitative Chinese. The Protestant Karens in Burma were visited by Japanese posing as fellow Protestant Christians, while Catholic Japanese tried to win the support of Filipinos. Where Indian communities existed, the Japanese announced that they favored independence for India, and a pro-Japanese Indian nationalist, Subhas Chandra Bose, organized the India National Army, to use when the Japanese invasion of India got underway.

These tactics did not produce the desired results, because more than a few natives realized that they were not truly free, but only changing their masters. One nationalist who was not fooled, Vietnam's Ho Chi Minh, said that driving out the West with Japanese help was like chasing the tiger out of the front door of a house by letting a wolf in the back! Another was the leader of the Thirty Thakins, General Aung San, who began plotting to rid Burma of the Japanese as soon as the British were gone.

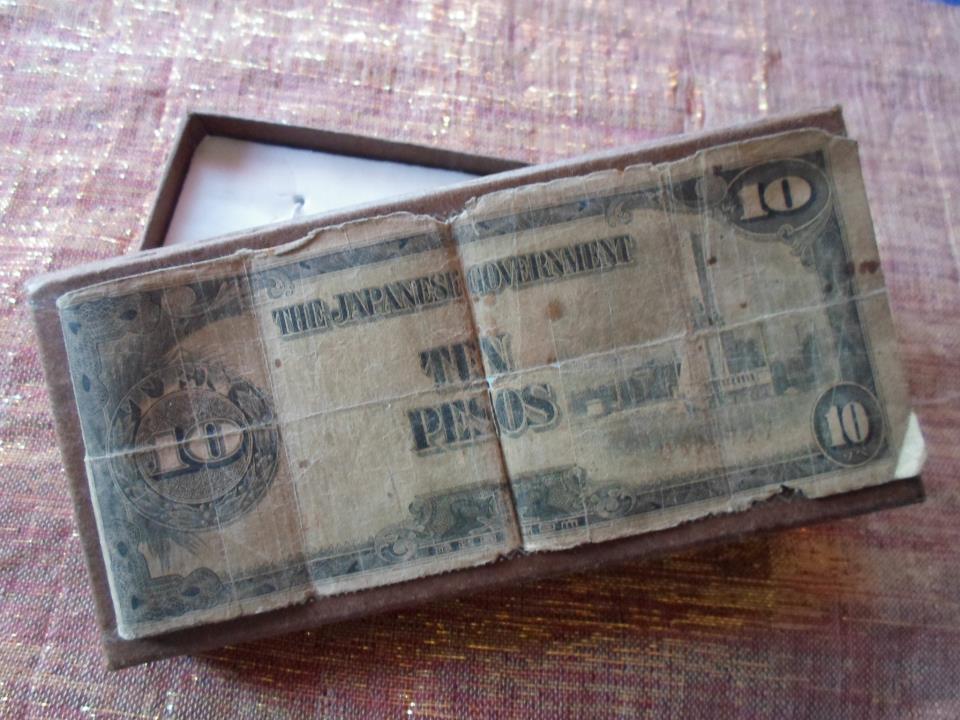

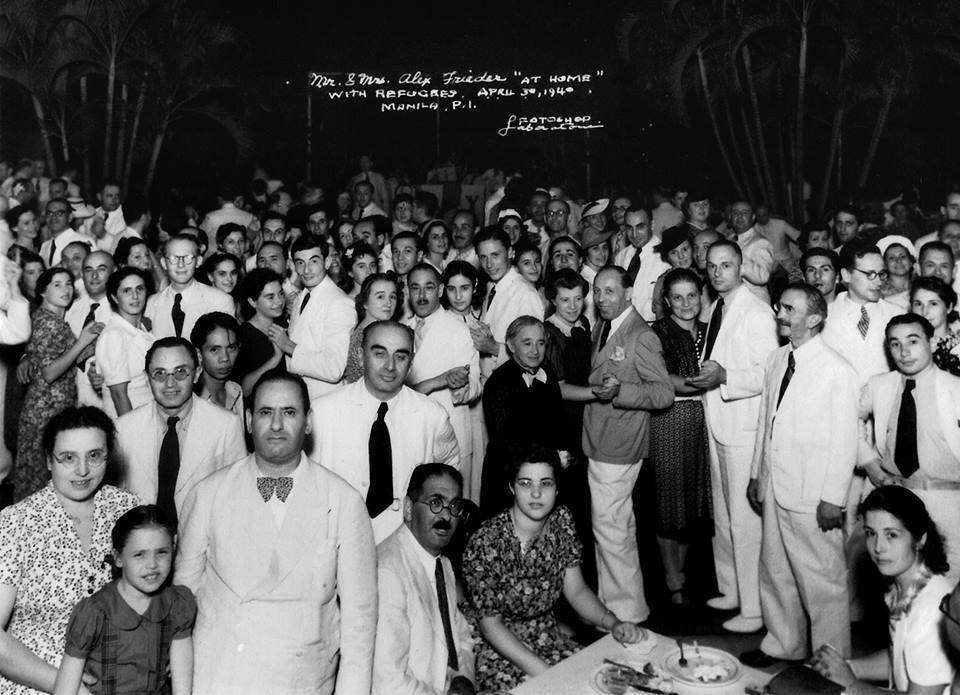

The Japanese promised to give their new subjects modern technology, industrial development, and an end to Western imperialism--in short, an equal share in the fruits of the empire. Actually, the Japanese postponed these projects indefinitely, and continued the colonial economy and plantation system set up by the West. Food and raw materials were diverted to supporting the war effort, natives were conscripted into forced labor battalions, and the local economies went from bad to worse. Even Thailand suffered from economic hardship, though officially it was independent from Japanese rule. To keep up with inflation, the Japanese printed more paper money, but that only made the problem worse; in the Philippines, the wartime currency became so worthless that Filipinos scornfully called it "Mickey Mouse money" (see below).

Wherever there was resistance, either real or imagined, the Japanese secret police, the Kempeitai, responded savagely, making life for conquered peoples as miserable as its German counterpart, the Gestapo, did.(1) Gradually resistance to Japanese rule arose in the form of guerrilla movements. In 1943 the Japanese tried to stop the growing unrest with political moves, granting "independence" to puppet regimes in the Philippines (under Jose Laurel) and in Burma (under Ba Maw), but this move fooled no one and attracted little popular support.

The most successful guerrillas were communist-inspired. When the war began Southeast Asia's communists took the Marxist view and tried to ignore it, claiming that it was a war between imperialists that did not concern them. That point of view changed in 1940-41, first because of Japan's alliance with Germany, followed by Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union. Now the war became a struggle to defend communism, and communists everywhere declared war against the Axis powers, becoming as antifascist as any freedom-loving American or Briton. In 1941 Ho Chi Minh returned to Vietnam after 30 years of self-imposed exile and set up his headquarters in a series of limestone caves north of Hanoi. His guerrilla army, the Viet Minh, offered membership to anyone who was both anti-French and anti-Japanese, though it was communist-controlled from the start. By early 1945 he was doing so well in anti-Japanese activities that the American wartime secret service, the O.S.S., smuggled supplies to him. Other communist guerilla movements included the People's Anti-Japanese Army (Hukbalahap) in the northern Philippines, the White Flag Army in Burma, and a Chinese movement called the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese army.

The Forgotten War in Burma

The Burma campaign affected, and was affected by, what went on in China and India, so the Allies called this war zone CBI, the "China-Burma-India Theater." Still it was at the bottom of everyone's priority list except for the soldiers who fought there, so it saw little activity for a year and a half, from May 1942 to November 1943. Another reason for this was the terrain involved; British general William Slim called it "some of the world's worst country, breeding the world's worst diseases, and having for half the year at least the world's worst climate." There was also a widespread belief that the Japanese were invincible in the jungle, because their troops lived off the land very effectively. In the winter of 1942-43, the British made a limited attempt to recover the Arakan coast, but it bogged down after advancing 75 miles, suffering 2,500 casualties before the force pulled back to India. More successful was a major guerrilla campaign waged behind enemy lines in early 1943 (the "Chindit War"), led by an eccentric British general, Orde C. Wingate. All this time China was kept from collapsing by a constant convoy of supply planes, which flew over a spur of the eastern Himalayas nicknamed "the Hump." In November 1943 a limited offensive to recover northern Burma began, led by the American general Joseph "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell. Despite Japanese resistance and abominable conditions, Stilwell's force reached Myitkyina, the main city of northern Burma, in six months, and took it after a three-month siege (May-August 1944). In the path cut by Stilwell's men, a new road, the Ledo Road, was built to replace the Burma Road.

Meanwhile the long-expected Japanese invasion of India had begun. The main force tried to capture Imphal, an important Allied stronghold near the Burma-Assam border. Another Japanese force moved northwards, to cut off the supply lines to China and Stilwell, while the Indian National Army accompanied a small Japanese force moving into Bengal from Arakan. Once Imphal and the surrounding objectives were taken, Bengal and Assam would come under Japanese control, providing the population base for later Indian campaigns.

The siege of Imphal began on March 8, 1944. Imphal was surrounded completely but managed to hold out with the help of an Allied airlift that brought in supplies and reinforcements. The northern offensive got as far as Kohima on April 4, but here Allied resistance also did not break, though the town was turned into a charnel house of ruin during the two-week battle before the Japanese were finally turned back. On the Arakan front the Indian National Army failed to start an anti-British uprising, partly because the Allied troops they engaged were not Indian, but from British colonies in Africa. With the beginning of monsoon season Japanese lines of communication and support disintegrated. In July the last Japanese forces retreated from India, and in October the Allied reconquest of central and southern Burma began.

The Liberation of the Philippines

MacArthur's entire strategy for winning the war centered on keeping his promise to the Filipinos. Events began to favor him in the summer of 1942, when Japanese offensives to the south and east were stopped at New Guinea, the Coral Sea, Guadalcanal, and Midway Island. It took two years of brutal jungle warfare (July 1942-July 1944) to clear the Japanese from his first objective, New Guinea. At this point the navy proposed bypassing the Philippines and landing on Taiwan, which was three hundred miles closer to Japan itself. MacArthur, appalled, warned that America had "a great national obligation to discharge" by liberating the Filipinos, which was in fact identical to his own obligation. When President Roosevelt summoned him and his naval counterpart, Admiral Chester Nimitz, to a conference in Honolulu, MacArthur won over Roosevelt to his plan. On September 15, 1944, he made his next step by landing on Morotai, the northernmost of the Moluccas. Meanwhile Allied bombers hit targets ranging from the Philippines to the Ryukyu Islands, destroying most of Japan's air force in the process.

The Philippine campaign began in earnest on October 20 with a massive landing on the island of Leyte, involving some seven hundred warships and transports, two hundred thousand troops, and two million tons of supplies for the first month alone. Four hours after the assault began, MacArthur staged the most famous scene of his career when he waded ashore with Philippine President Sergio Osmena (Osmena's predecessor, Manuel Quezon, had died of tuberculosis two months earlier).

Once MacArthur was on Leyte, the Japanese went for a showdown. The Japanese army had thirteen divisions in the Philippines at this point and was confident it could drive the Americans back into the sea. The navy, however, came up with a more complex strategy to make the most of the most of the few ships and planes it had left; it deserves to be explained in detail. After the Americans took the Marianas Islands in the summer of 1944, the surviving Japanese ships split according to class; the battleships and cruisers were now anchored near Singapore and Borneo, where there was enough oil to keep them running, while the carriers had returned to Japan in the hope that the planes they had lost could be replaced. Japan's naval chief for the area, Admiral Soemu Toyoda, decided to reunite these groups in the Philippines. The carriers still did not have planes, but carrier-obsessed American pilots didn't know that, so the carriers could serve as decoys to distract them. Thus the carriers, commanded by Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, were used to lure away the protective fleet of Admiral William Halsey, which was covering the Americans on Leyte. Next, Toyoda ordered his big-gunned ships at Singapore and Borneo to converge on Leyte and annihilate the nearly naked American support flotilla. The battleships and cruisers traveled in two groups, threading their way through the central Philippines to reach Leyte Gulf. Admiral Shoji Nishimura led two battleships, a cruiser and four destroyers that approached Leyte from the south, while Admiral Takeo Kurita approached from the north with the main force, six battleships and seven cruisers.

The battle of Leyte Gulf was the largest naval battle in recent history. The first part of Toyoda's plan worked perfectly; the Americans spotted all three groups by October 24 and Halsey, diverted, steamed northward to take the carrier bait. As Kurita got close he lost two cruisers to submarines and a battleship to the planes from Halsey's carriers, leading Halsey to mistakenly think that he had knocked out Kurita's whole task force. Consequently Halsey left the San Bernardino Strait unguarded, allowing Kurita's other ten ships to enter Leyte Gulf. What made this really bad was that the commander of the support ships still in Leyte Gulf, Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, thought Halsey was still protecting him and the troops against enemies from the north. Kinkaid sent most of his own armed ships to Surigao Strait, between Leyte and Mindanao, where they ambushed and sank Nishimura's ships in the middle of the night, only to get calls for help the next morning from the ships at the Leyte beachhead; they were now under attack from Kurita's force.

Besides an assortment of "soft targets" (unarmed ships), Kinkaid had six escort carriers and seven destroyers left at the beachhead. Kurita managed to sink one carrier and three destroyers; it looked like the rest were doomed as well. But the American planes had more firepower than the Japanese ships, so the Japanese, lacking air cover of their own, in turn lost three cruisers. If Kurita had pressed his advantage, he probably would have succeeded in wiping out the American fleet, at the cost of most of his own ships and men. Indeed, before the battle, the Japanese admirals were thinking that they would not survive what they were planning, and decided that if they took enough Americans with them, their sacrifice would be worth it. Instead, however, Kurita suddenly turned around and retreated back the way he came. Exhausted and confused from lack of sleep, Kurita had mistakenly concluded from intercepted radio messages that Halsey was coming back to get him. In fact, Halsey was far away, still chasing Ozawa's carriers. Because of lack of coordination among the Japanese task forces, and because Kurita did not want to die tired, Toyoda's decoy plan had worked to snatch a defeat from the jaws of victory.

Bushido, the old samurai code of ethics, teaches that an honorable death is more important than a good life, so there were still plenty of Japanese willing to commit suicide for the emperor. The fighters they had left were loaded with explosives for one-way suicide missions. These flying bombs were called kamikaze, or "divine wind," after the typhoons that saved Japan from Kublai Khan's invasions in the thirteenth century. The navy called for volunteers to crash the kamikaze into Allied ships, and got an enthusiastic response. They first saw action in the battle of Leyte Gulf, where a kamikaze sank one of Admiral Kinkaid's carriers, meaning they could be as effective as the guns of a battleship. For the rest of the war, gunners on American ships were on the lookout for kamikaze pilots, and they managed to shoot down four fifths of them before they hit their targets.

The debacle in Leyte Gulf destroyed half of Japan's naval tonnage, but on land the Japanese army was far from finished. Heavy fighting continued on Leyte for the rest of 1944, and resistance did not end until late March 1945. Meanwhile MacArthur had begun landing troops on the nearby islands of Samar and Mindoro. The invasion of the main island, Luzon, began on January 9, 1945. Once the beachhead was secured, the Americans made a beeline for Manila, arriving there at the beginning of February. Manila had escaped damage when the Japanese took it three years earlier; this time the city was not so lucky. The Japanese army commander, General Tomoyuki Yamashita, wanted to spare Manila's civilian population from the ravages of war, but the naval troops in the city were not willing to leave without a fight. The result was a month of bloody house-to-house and hand-to-hand fighting, interrupted by artillery duels, fires that sept through bamboo neighborhoods, and more Japanese atrocities. By the time it was all over (March 4, 1945), there was scarcely a house or building left standing in the city.

The Last Acts of World War II

By the end of 1944, even the most ardent militarist in Tokyo knew that Japan had lost the war. Desperate strategies were developed to postpone the inevitable invasion of Japan itself. We mentioned one already, the kamikaze. Japanese soldiers were ordered to sell their lives as dearly as possible, to gain time for their countrymen back on the home islands. Consequently, the last battles of the war were often the toughest for the Allies to fight.

With the taking of Manila and the clearing of Manila Bay, America had control of the most important parts of the Philippines. But MacArthur was not willing to rest until every square inch of American soil was liberated, so the task of rooting out the Japanese from the rest of the archipelago continued. Yamashita's troops were short on supplies and equipment, without air or sea cover; they were isolated not only from Japan but from their comrades on other islands. Their morale was slipping, but they were resolved to contest every piece of ground for as long as it was humanly possible. The mopping-up campaign went on for the rest of the war, and about a fourth of Yamashita's original 450,000-man army lived to see the war's end.

Late in 1944 the headquarters of Japan's Southeast Asian armed forces was moved from Manila to Saigon. By this time native opinion in most areas was clearly favoring an Allied victory. Furthermore, now that France had been liberated by the Allies, it seemed likely that the French government in Indochina would go over to the Allies at the earliest opportunity. In March 1945 the Japanese tried solving both problems by removing the French and replacing them with native-run governments, led by the current monarchs of each country: Norodom Sihanouk (Cambodia), Sisavang Vong (Laos), and Bao Dai (Vietnam). The royal family of Laos immediately split in two, forming anti-French and anti-Japanese factions; their dispute was not resolved before the French returned in 1946. Independence was also promised to the Indonesian nationalists, but no date was set there.

In the spring of 1945, the Japanese retreat from Burma turned into a rout. Mandalay was liberated on March 20, but Rangoon remained in Japanese hands until the first rains of the monsoon season. That could have been a disaster, leaving the Allied armies with the same supply problems that Japan had in India, but the Burmese nationalists saved the day. General Aung San renamed his Burma National Army the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL), defected to the Allied camp, and together they liberated Rangoon on May 3.

The last Southeast Asian campaign of the war involved three joint American-Australian landings on Borneo in June-July 1945. Most Allied leaders expected the war to last until the end of 1946, so plans were drawn up to conquer the rest of the region. The campaigns on the drawing board included proposals to retake Singapore, an amphibious assault on Vietnam or Java, and an invasion to neutralize Thailand. The eventual goal of all this was to drive the Japanese out of China and provide bases for the final invasion of Japan. However, the Pacific fleets of Admiral Nimitz got to Japan first, and the dropping of the first atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki made all other campaigns unnecessary. When Japan surrendered on August 14, 1945, more than 70 percent of Southeast Asia's territory was still under Japanese occupation.

Nationalism Unleashed

World War II permanently changed the relationship between the peoples of Southeast Asia and their colonial masters. First of all, the myth of the white man's invincibility had been shattered by Japan's rapid advances during the early months of the war. Also, the Japanese had encouraged the growth of nationalism, using it as a tool to turn native opinion in favor of the Axis. Those nationalist leaders who had been imprisoned or exiled by the West were set free, and often used to recruit native, pro-Japanese armies. In Indonesia the Japanese introduced a simplified Malay language, Bahasa Indonesia, to replace the 250 languages and dialects used in the archipelago previously. All over the region Southeast Asians started to see themselves as true modern nations, rather than a mixture of rival religions, languages, cultures and races. Finally, the devastation caused by the war gave many Southeast Asians a great desire to be left alone; they were no longer willing to be used as a pawn in the conflicts between empires. When the Allies returned to their colonies of the prewar era, they found all sorts of social unrest waiting for them.

The four colonial powers reacted to the changed situation in different ways. America had promised independence to the Philippines before the war, and now Britain's new Labor government announced that it would let the British colonies go, if it could do so without losing face. The French and Dutch, on the other hand, acted as if nothing had happened since 1940. Both of them still believed that Western technology and skill were superior to any local army or political movement. As for the current wave of unrest, that was seen as an aberration that could be dealt with quickly; after all, the prewar nationalist movements had been effectively suppressed, hadn't they? This shortsightedness would lead to new wars in French Indochina and the Dutch East Indies, and the humiliating expulsion of the Europeans from both. And while America and Britain willingly got out of the territories they had, there was even trouble there, as we will see.

The Indonesian War of Independence

Sukarno was expecting the Japanese to grant Indonesian independence before World War II ended, so he was taken by surprise when Japan surrendered first. On August 17, 1945, he proclaimed the independence of the Republic of Indonesia, with himself as president and Muhammed Hatta as vice-president. The Dutch were willing to negotiate a new future for the Indies, but complete independence was more than they were willing to give. Sukarno and Hatta replied that they could not take back their independence declaration, and that the only thing worth talking about was the speedy liquidation or removal of everything the Dutch owned in the islands. This impasse made war inevitable.

The first skirmishes were directed against the Japanese troops that occupied Java in August 1945. The surrender terms imposed on Japan required that her troops in occupied areas maintain order until the arrival of Allied units. In September British forces arrived to disarm and replace the Japanese, and the task of holding the Indies went to them. They fought the first big battle of the war at Surabaya in November 1945, expelling the nationalists from that east Javan city. This battle was also the last time that Indian soldiers saw combat while serving in the British army. There was some apprehension among the British that the Indians might refuse to fire on fellow Asians, since they also wanted independence from the West. The Indian soldiers, however, had seen enough attacks and excesses from the Indonesians to remain loyal to their commanders.

Gradually the Dutch returned to take back the islands they had owned for centuries. It didn't take long for them to realize that reconquering the archipelago would be no easy task, since the Indonesian nationalist army was much larger than their own; the current poverty of the war-ravaged Netherlands did not make it any easier. The Dutch did have some factors in their favor, though. Most of the Indonesians had little or no military experience; their morale and discipline were less than reliable. Often individual militants would commit atrocities that embarrassed Sukarno in his negotiations. The Indonesians also had a problem with infighting between the communist, socialist, moderate, and Islamic factions within their movement. Because of this, the Dutch concluded that they could win the war by keeping the natives divided.

The Dutch won the first battles they took part in, driving the nationalists out of key Javan cities like Batavia and Bandung. Sukarno was forced to move his headquarters to Yogyakarta, where it remained for the rest of the war. As the same time, however, the Dutch came under international pressure to negotiate some kind of peace agreement before the last British forces were withdrawn. The result was the Linggadjati Agreement, completed in November 1946 and signed the following March. It called for the creation of three states, known collectively as the United States of Indonesia. One of the states would be Java, Sumatra and Madura, ruled by Sukarno's republican government. Borneo would become the second state, while the rest of the islands would form a third, with the capital on Bali.(2) Dutch property rights would be protected, and Sukarno's forces would have the responsibility of keeping the peace in their territory. The three states would be loosely tied to the Netherlands in a commonwealth-type relationship, with the Dutch crown as the ultimate head of state over all of them. The Dutch claimed that the system was designed to give fair treatment to the peoples of the outer islands, since they would resent being part of a Javan-dominated state. There was some truth to this, but the real reason was to quarantine Sukarno's revolution, confining it to the three islands where it already existed and thereby keeping the less politically developed outer islands safe from infection. If the plan worked right, the Dutch would keep some power over the islands indefinitely.

The Linggadjati Agreement lasted for four months. When the Indonesians failed to control lawlessness in republican territory, the Dutch saw an excuse to intervene. In July 1947 the Dutch invaded, capturing two thirds of Java and the richest sections of Sumatra. But the campaign solved nothing. Indonesian units continued to roam throughout the countryside and never ceased partisan warfare. More important was the effect on the rest of the world. Batavia called the operation a "police action," but it was denounced abroad as colonialist aggression. The fledgling United Nations called for a cease-fire and more negotiations, and the two sides met on the U.S. destroyer Renville. In January 1948 they came up with a new agreement that was much like the first one, except that this time the areas conquered by the Dutch would get to vote on whether or not they wanted to join Sukarno's republic. Of course this agreement was no more viable than the Linggadjati one; from the beginning both sides prepared for more conflict. The Dutch placed friendly regimes in the areas they controlled, and blockaded what remained of the republic.

Pressure on the republic increased from the inside as well. In February 1948 22,000 Indonesian troops were moved from mostly Dutch-held western Java to republican central Java. A number of Moslem guerrillas, however, remained behind, united under the leadership of a local mystic, S. M. Kartosuwirjo. Feeling betrayed by the republic, Kartosuwirjo proclaimed himself imam or head of a new state called Darul Islam (from the Arabic dar al-Islam, meaning the land or world of Islam). In May he raised the banner of revolt against both the Dutch and the republic. Since the Dutch were the main enemy, the republicans had to ignore this Far Eastern ayatollah for the time being; the fundamentalists in the republican army were wishing him luck anyway. After independence Darul Islam became no different from a crime wave of banditry, extortion and terrorism on a grand scale. As a regional rebellion it survived until Kartosuwirjo was captured and executed in 1962.

In 1948 Sukarno looked for help from sympathetic foreign governments, and he found it, thanks to bad planning on the part of the communists. The Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) tried to gain control of the revolution by recruiting members of other parties, hungry victims of the Dutch blockade, and irregular soldiers to their cause. In September 1948 they launched a coup against Sukarno in the central Javan city of Madiun, and failed miserably. No peasant uprising was touched off; the military, which at first seemed to waver between Sukarno and the PKI, mostly sided with the republicans. In a matter of days, the Madiun rebels were driven into the mountains, to be captured or killed later.

The Madiun rebellion could not have come at a better time, from Sukarno's point of view. Before this time many foreigners feared that the Indonesian struggle for independence was coming under communist domination. Since the Cold War was now fully underway, the Dutch played this up, claiming that in Indonesia the choice was not simply between Dutch and native rule, but also between democracy and communism. What happened at Madiun cleansed Sukarno of the red taint; by crushing the PKI he now became a legitimate moderate nationalist in the eyes of Westerners. After this foreign opinion, particularly that of the United States, tended to favor the republicans.

The third and last round of fighting in the war broke out in December 1948. Sensing that time was running out for them, the Dutch launched a lightning attack on Yogyakarta that captured the republican capital and most of its leaders, including Sukarno. By the end of the year all major republican towns were in Dutch hands. The only area still completely controlled by the nationalists was Acheh, in northwest Sumatra; the Dutch still remembered the Acheh War (see Chapter 3), and felt it was wise to stay out of there. The whole campaign looked like an easy victory, but it turned out to be a political catastrophe. The Indonesian public gave next to no cooperation, the captive republican leaders refused to call on their forces to quit fighting, and guerrillas continued to harass Dutch units at every opportunity. World opinion was outraged by the Dutch action. The UN Security Council demanded an immediate cease-fire and the release of the republicans. Even more important was the pressure from the United States, which threatened to cut off all postwar economic aid to the Netherlands unless the Dutch negotiated in good faith with their subjects. The diplomatic blackmail succeeded. By July 1949 Yogyakarta was back in republican hands, and negotiations began in The Hague one month later. On December 27, 1949, independence came to the Republic of the United States of Indonesia (RUSI).

The agreement that ended nearly three and a half centuries of Dutch rule did have some concessions in it, though. The multi-state system favored by the Dutch was preserved, as well as several agreements that promoted Dutch-Indonesian cooperation. Two thirds of Indonesia's foreign trade remained under the control of Dutch businesses. And the Netherlands got to keep the western half of New Guinea. The Dutch gave three arguments for why the Papuans, the stone age tribes living on New Guinea, should remain under Dutch rule: (1) they were not Malays, but belonged to the Melanesian race; (2) as new converts to Christianity, the Papuans did not want to become part of a Moslem state; (3) they were not yet ready to govern themselves. All of these statements were true, but because the political mood in the late 1940s and 50s favored nationalism, most outsiders saw them as excuses for the Dutch to hold onto one piece of their Asian colonial empire.

Despite the favorable start, the agreement remained intact for only eight months. Sukarno was so popular all around that most of the smaller federal states dissolved themselves into the republic. The Christian, pro-Dutch island of Amboina tried to proclaim an independent South Moluccan state, which was crushed by Sukarno's troops (1950-52). In August 1950 the entire government of the RUSI was declared unworkable, swept away, and replaced by a unitary regime, the Republic of Indonesia, with Batavia, now renamed Jakarta, as the capital. The Dutch-Indonesian unity under the Netherlands crown never became a reality. And the New Guinea question would be reactivated by Dutch-Indonesian quarreling a decade later.

The Karen Revolt and Other Burmese Problems

Aung San was by far the most popular man in Burma in 1945. He got along well with Sir Hubert Rance, the British general who was appointed governor after the liberation of Rangoon, but when World War II ended, Rance retired and was replaced with an unsympathetic civilian, Reginald Dorman-Smith. The new governor remembered that Aung San had supported the Axis for most of the war, and had him arrested. Burmese workers went on strike immediately, and prepared for rebellion, but cooler heads in London defused the explosive situation. Rance was brought back to be governor again, and he formed a new cabinet that included Aung San and six other members of the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League (AFPFL). Aung San insisted that the British grant nothing less than complete independence, and discussions for a peaceful transfer of power began. In December 1946 Prime Minister Clement Attlee invited Aung San to London, and one month later they signed an agreement that gave Aung San everything he wanted.

Not everyone in Burma approved of the agreement. The communists in the AFPFL, who rejected any negotiations with the West, declared that the terms were not good enough, broke with Aung San, and went underground. They reappeared a year later as two guerrilla movements, the Stalinist White Flags and the Trotskyite Red Flags. And the ethnic minorities, who make up a third of Burma's population, were less than thrilled with the idea of independence. Many of them, particularly the Karens, did well under the British, and even those groups who didn't thought British rule would be better than Burmese domination. Four minorities--the Karens, Shans, Kachins and Chins--demanded independent states of their own. Aung San had a series of meetings with the chiefs of the Shans, Kachins and Chins; he persuaded them to give the Burmese government a ten-year trial before seceding. The diplomacy worked. The minorities were granted autonomous status within the union, and 79 of the 255 seats in the Constituent Assembly were reserved for non-Burmese. When elections were held in April 1947 to create the government of independent Burma, the AFPFL won an overwhelming victory, putting 248 representatives into the Assembly.

Aung San still had to make a deal with the Karens, the largest and hardest minority to please. He never got the chance to do it. On July 19, 1947, two gunmen broke into a cabinet meeting and murdered Aung San along with seven of his ministers. He was only 32 years old. The perpetrator was a political rival, former prime minister U Saw, who may have been hoping that with Aung San out of the way, the British would turn to him to lead the country. The crime, however, was poorly planned; the hit men were traced to his house by the police, everyone involved was arrested, and after a sensational trial U Saw and his accomplices went to the gallows. The president of the Constituent Assembly, Thakin Nu (known as U Nu from now on), was sworn in as prime minister.

Aung San's death deprived Burma of its most capable leader, but nobody allowed that to delay independence. The Union Jack was hauled down on January 4, 1948, a date that had been picked by astrologers as being the best to ensure a good future for the new nation. One wonders what would have happened had an unlucky date been picked, since Burma almost disintegrated in the months that followed. Opponents of the U Nu regime rose up everywhere, starting with the two communist factions. The People's Volunteer Organization (PVO), a militia of World War II veterans, turned against the government and allied itself with the communists, who promised a utopia that was more to their liking. The Karens formed the Karen National Defense organization (KNDO), and set out to create an independent Karen state. Another minority, the Mons, also revolted. Finally there was a Moslem rebel movement, the Mujahadin, which tried to break off the Arakan region and join it to the nearest Moslem state, East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). Later on in his autobiography U Nu would summarize this period by quoting the British proverb "trouble never comes singly."

The darkest days for the government occurred during February-April 1949. At that point the whole southeastern quarter of the country was in Karen-Mon hands. The PVO and the communists together controlled most of the Irrawaddy valley, including Mandalay, the second largest city. Rangoon's defense was left to units composed of Kachin and Chin troops, a part of the PVO that remained loyal, and to the Fourth Burma Rifles, commanded by another former Thakin, General Ne Win. But the insurgents were never able to coordinate their attacks, and gradually the determination of U Nu and Ne Win turned the tide in favor of the government. Mandalay was recovered, the communists and PVO were worn down until they disbanded, and the Karens were pushed back across the Salween river. One reason for the government's victory was U Nu's strict neutral foreign policy. He took almost no foreign aid, and refused to ask the United States, Soviet Union, or any other foreign government for assistance of any kind. Fortunately for him, no foreign power supported his enemies. Today's Burmese like to point to Vietnam and Cambodia as examples of the kind of devastation superpower involvement can produce.

Just when it looked like the worst was over, the Chinese civil war spilled across the northern border. At the end of 1949 Mao Zedong's communists conquered southern China, and 12,000 of Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalists escaped into Burma. They occupied part of the Shan plateau and used it as a base to make raids back into China. The Burmese army tried, but never could, dislodge the Nationalists. Finally U Nu took his case to the United Nations. 6,000 Nationalist Chinese were airlifted to Taiwan in 1954. The rest chose to stay, living out the rest of their lives as drug lords, growing opium in what would soon be called the "Golden Triangle," an ill-defined area where the hilly jungles of Burma, Thailand, and Laos meet.

Eventually order returned to most of Burma, but not all of it. The Mujahadin continued to resist until 1961. A new Burmese Communist Party was organized in China in 1967. And the Karen revolt never ended. Periodically the Burmese government has offered land and/or amnesty to insurgents who give themselves up, but 5,000 Karen guerrillas still struggle against Rangoon today.

The Hukbalahap Rebellion

Delayed by World War II, independence finally came to the Philippines on July 4, 1946, exactly one year after the original agreed-on date. That marked the end of the islands' long colonial history, a period jokingly described by Filipinos as "three centuries in a Spanish convent followed by half a century in Hollywood." Like Burma, the Philippines was heavily damaged by the war, and not really prepared to stand on its own. Most of the people were on the verge of starvation. The landlord upper class had protected its interests during the war by collaborating with the Japanese; the guerrillas who supported the Allies were mostly peasants with nothing to lose but their lives. The collaborators were so numerous that they were never all tracked down; some of them got portions of the U.S. aid that was sent to rebuild the country. Even the two sons of the president, Sergio Osmena, were quislings. Since Osmena could not punish an entire social class without creating chaos, he was prepared to forgive and forget. So was General MacArthur, who gave a clean political bill to a personal friend who had been a double agent, Manuel Roxas. MacArthur couldn't get along with Osmena anyway, so he scheduled elections for April 1946. Roxas organized a second political party, the Liberal Party, and ran against Osmena and his party, the Nationalists. From the Filipino point of view, anybody MacArthur liked was good enough for them. As a result, Roxas was president on the day of independence.

Because the country was in a shambles, Roxas had to ask for U.S. aid on terms that were highly favorable to the Americans. The United States remained the main trading partner of the Philippines, and American businessmen enjoyed the same rights as Filipinos when investing in the country. The largest U.S. Naval base outside of American territory (Subic Bay) and a major Air Force base (Clark AFB) were allowed by treaty to remain on Luzon; both served as important advance bases for U.S. forces on their way to Vietnam. In return the Philippines got more than $1 billion in aid, and was allowed to export to the United States for years without tariffs. This meant that American influence remained as strong as it was before independence, and Americans did not miss having the Philippines as a U.S. territory.

When the war ended many Filipinos were afraid of the Hukbalahap guerrillas, who had fought the Japanese in central Luzon. Aware that the mood in America was deeply anticommunist, they denounced the Hukbalahaps (Huks for short) as dangerous communists. Most of the Huks, though, were impoverished peasants who did not even know what communism was; the Huk leader, Luis Taruc, appears to have been the only real Marxist in the entire movement. During the 1946 elections the Huks teamed up with other leftists to form a coalition they called the Democratic Alliance. Six of them, including Taruc, won seats in the national legislature. Roxas refused to let the Alliance members serve in office, and Taruc, appalled by the injustice of Philippine society, returned to the countryside to proclaim an uprising against the government.

Roxas promised to crush the rebels in sixty days, but he misjudged badly. His troops caused widespread destruction, and terrorized the peasants until they were driven into the ranks of the Huks. Roxas died in 1948 without finding a solution, and under his successor, Elpidio Quirino, the problem simply got worse. Meanwhile, Taruc copied the practices of Mao Zedong's guerrillas in China, and set up his own government to dispense land and justice to the people in his area. At the movement's height, it numbered about 67,000 guerrillas, and it received food, lodging, intelligence and communications from a network of two million peasants.

The situation turned around in 1950 when the defense secretary resigned and was replaced by Ramon Magsaysay. A remarkable figure in Philippine politics, Magsaysay came from a middle-class family, rather than from the elite that produced all the leaders before and after him. An unashamed populist who preferred the company of ordinary citizens, Magsaysay alone knew what the feelings of the people really were. As defense secretary he straightened out the armed forces by purging incompetents, breaking up officer cliques, improving morale and rewarding achievers. For the peasants he provided banks, clinics, courts and lawyers to represent them in claims against landowners. Most importantly, he promised farms to the rebels who surrendered. Sure enough, he beat the Huks at their own game. Gradually the guerrillas gave themselves up and went to claim the lands promised them. Taruc surrendered to a young newspaper reporter, Benigno S. Aquino, in 1954, and the rebellion was declared over a few years later.

Magsaysay's success and the influence of several Americans, including Edward Lansdale, an Air Force officer who worked for the CIA, helped him get elected president in 1953. He campaigned under the slogan "Magsaysay is my guy," and reveled in his American connections. Being called an "Amboy" (America's boy) would have ruined a Third World politician anywhere else, but here, where Americans were seen as big brothers, it caused him to win by a landslide. Once in office he tried to finish the reforms he started, only to get bogged down when the bureaucracy opposed his plans. In 1957 he was killed in a plane crash; most of his work, including the land reform, was never completed. The economic problems that he tried to solve would return to haunt his successors, and eventually the rebels would come back under new names. As for the reporter who brought in Taruc, he would use the scoop of a lifetime to run for public office. By 1970 Aquino was not only a senator but the most popular man in the country.

Thailand: Between Hot and Cold Wars

By 1944, the course of World War II had not only turned against Japan, but also against the strongman of Thailand, Phibun Songgram. In July the National Assembly turned down Phibun's proposal to build a grand new capital city and forced his resignation as prime minister. The anti-Japanese Free Thai underground took control of Bangkok. It could not, however, quit the Axis while Japanese soldiers were on the border. Neither could Phibun be tried as a war criminal, since he still had enough troops on his side to stage a coup if he felt like it. The Free Thai leader, Pridi Phanomyong, was forced to bide his time for the rest of the war. When Japan surrendered, he promptly voided Thailand's declaration of war against the Allies.

After the war Pridi returned northern Malaya and Burma's Shan Plateau to Britain; these territories had been given to Thailand by the Japanese as a reward for joining the Axis. He also made it clear to everyone that Thailand had been a reluctant partner of Japan, forced to join because the alternative would have been a Japanese invasion. He stressed that the Thai people had long been friends of the West, particularly the United States, and that the war declaration was illegal because Pridi and the king's regents had never signed it. The United States, which had no strategic interests on the Southeast Asian mainland (yet), was quite willing to forgive and forget. The other Allied powers, however, put a long list of demands upon Thailand, and threatened to keep Thailand from joining the United Nations if the demands were not met. France wanted the return of the disputed Cambodian and Laotian territories; the USSR wanted the Communist Party legalized in Thailand; Britain wanted favorable trade agreements, the right to station British troops on Thai soil indefinitely, and 1.5 million tons of free rice. Strong US pressure in Thailand's favor forced the British to drop their demands, except for the rice, which was sold instead of given away.

Since his coronation in 1935, King Ananda Mahidol Rama VIII had spent most of his time attending school in Switzerland. In December 1945 the 20-year-old monarch returned to Bangkok and took on his royal duties. One month later elections were held to form a postwar government. Pridi was sworn in as prime minister in March, and a new constitution went into effect in May. Pridi was now at the height of his career, but his success was short-lived. On June 9, 1946, the young king was found murdered in his bed. The perpetrator of this crime was never caught, but many at this time believed Pridi to be responsible, since he had often disagreed with the king's father during the 1930s. The public outcry was so great that Pridi resigned and went into exile. A year of chaos followed, ending in November 1947 when a coup brought Phibun back to power. Meanwhile the late king's eighteen-year-old brother, Bhumibol Adulyadej, was crowned King Rama IX; like his predecessor, he stayed in Switzerland until he was old enough to rule (November 1951).

Phibun's second government did away with Pridi's socialist ideas and allowed a free market economy to run unchecked. At the same time he imposed martial law to get rid of his civilian opponents. He did this because his position was not entirely secure. Three times during his rule there were violent coup attempts against him, led by rival officers. The Cold War also made him nervous, and with good reason, since Chinese and Vietnamese communists were encouraging the Malay community in the southern provinces and various minority tribes to revolt against Bangkok. Every time an incident involving communists took place in Asia, Phibun responded by improving his ties with the United States. A few thousand Thai troops fought alongside the Americans in Korea and Vietnam, and Bangkok became the headquarters of SEATO.

Phibun tried to be a benevolent dictator by improving the schools and public health facilities. In 1955 he came back from a trip to the West with a sudden desire to turn Thailand into a real Western-style democracy. Perhaps he wanted to be loved by his people, rather than feared by them. Whatever the reason, he held new elections in early 1957, and his party won by a narrow margin. Phibun's opponents accused him of fraud, vote rigging, tampering, and coercion. Phibun declared a state of emergency to restore order but could not keep his generals from turning against him. In September they staged a bloodless coup that toppled Phibun and forced him to flee the country; a rival general, Sarit Thanarat, took his place. Twenty-five years had brought enormous social and economic change, but politically the kingdom seemed stuck in 1932.

The First Indochina War

Indochina was also in a mess when World War II ended. The French administration that had originally governed the land was destroyed; the Japanese were defeated and waiting to go home. The native monarchs who had gained independence for their lands in March 1945 were hoping they could keep it when the victorious Allies arrived. In northern Vietnam, the Viet Minh controlled seven provinces, while a famine caused by Japanese mismanagement killed one fifth of Tonkin's population. Saigon saw fighting for control of the city between the Viet Minh, Trotskyites, Cao Dai, Hoa Hao, and a local mafia called the Binh Xuyen. Ho Chi Minh, the Viet Minh leader, went to Hanoi and declared what he called the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. Bao Dai, the emperor, knew he was less popular than Ho Chi Minh; to avoid being on the losing side of a revolution, he abdicated and became an advisor to Ho. Later on he got tired of that and moved to Hong Kong, where he became known as "the nightclub emperor."

Ho hoped for support from the Allied powers, particularly the US, to keep the French out of his new state. But at the Potsdam conference, one month before Japan's surrender, the Allies had decided to return all of Indochina to the French. To disarm and remove the Japanese, Chinese troops were sent in to occupy the part of Indochina north of the 16th parallel, while British troops performed the same task in the south. The British commander, Major General Douglas Gracey, was only supposed to deal with the Japanese, but he did everything he could to help the French by hitting the Indochinese nationalists hard, fast, and continually. The Chinese had little reason to like the French, so they left Ho Chi Minh and his government alone. Instead, the Chinese army descended on Hanoi like a horde of human locusts, stealing food, soap, light bulbs, and anything else that might be remotely valuable. Even Ho was glad to see the Chinese go home when the French returned in February 1946.

The infant nationalist movements of Laos and Cambodia could not resist the French, so they surrendered in early 1946, placated by promises of autonomy in the near future. Likewise, the French had no trouble regaining control over southern Vietnam, after what the British had done. Ho Chi Minh, however, still demanded complete independence, but his guerrillas were in no shape to fight after the Chinese occupation of the north. He quickly negotiated an agreement that made Vietnam an independent state within the French Union, the new government France was setting up over its colonies. A lot of questions were left unanswered, like the fate of French economic interests within Vietnam, how much independence Vietnam would actually receive, and whether or not Cochin China would be a part of it.(3) In May Ho went to Paris to negotiate these issues; during the next four months he gave away so many concessions that he told his bodyguards afterwards, "I've just signed my death warrant."

Despite all this, peace could not last. Few expected it to, and it would have been difficult for France to keep its part of the bargain anyway, since the government of the Fourth Republic changed its prime minsters frequently. The French military commander on the spot, General Etienne Valluy, secretly proposed a coup d'etat against Ho, while the leader of the Viet Minh soldiers, Vo Nguyen Giap, began to prepare for a showdown. It came in November 1946 when skirmishing between French and Viet Minh customs agents in the port of Haiphong grew into a full-scale battle. The Viet Minh were driven out of Haiphong when French ships and airplanes bombarded the city, causing frightful casualties. In December the Viet Minh made a surprise attack on the French garrison in Hanoi. Valluy remarked, "If those gooks want a fight, they'll get it," and the First Indochina War began.

For the next three years both sides enlarged their forces and jockeyed for position, with no clear advantage for either. In both the north and the south the French held onto the cities, while the Viet Minh roamed at will in the countryside. From the start the French had superior weaponry, but there was no visible enemy to fight, since the Viet Minh could disappear at will into the jungle. When the odds were against the Viet Minh, they simply merged into the population, becoming indistinguishable from everyday peasants. Giap made his share of mistakes, though; when his troops captured modern Japanese and French rifles and machine guns, he got the idea that this was all that was needed to fight and win a conventional war. As a result, the French won most of the early battles.

1949 saw two events that changed the course of the war, the return of Bao Dai and the victory of communism in China. By this time the French realized that they were going to need the support of a friendly Vietnamese leader to check the growing influence of the Viet Minh. The most obvious noncommunist among the Vietnamese was Bao Dai, so the ex-emperor was lured from his self-imposed exile in Hong Kong and offered his throne. Bao Dai demanded Vietnam's independence as the price for his cooperation. France agreed to grant it, but retained control over Vietnam's army, finances and foreign affairs. As a result, most Vietnamese did not take the Bao Dai regime seriously. The United States did, though, and that was the beginning of America's long involvement in Vietnam.

Up to this time Ho Chi Minh had respected the United States, because it was strong, free, and most of all, anticolonialist. In 1946 he said he wished Vietnam had been an American colony like the Philippines rather than a French one, because America would have given Vietnam its freedom by now. Since Ho was always a nationalist first, friendly diplomatic moves at this point might have persuaded him to become a neutral communist, like Yugoslavia's Tito. But the United States was not about to do anything that would alienate the French, who were a badly needed part of the new North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Furthermore, by this time the Cold War was fully underway, and most Americans felt that communism had to be stopped somewhere before it engulfed the whole world. In the days of McCarthyism even a pliable playboy looked better than a Marxist, so in January 1950 formal recognition was given to Bao Dai's government. When the Korean War began a few months later, Indochina was seen as a second front in the same conflict, so US military aid began flowing to support Bao Dai and the French. Because the war was bankrupting France, US aid increased every year, until by 1954 America was paying 80% of the French military bill in Indochina.

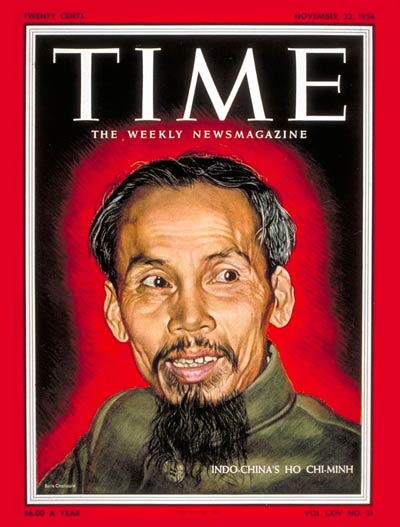

Ho Chi Minh, on a 1954 Time Magazine cover. The picture was based on a photograph taken in the late 1940s.

In 1949 France gave Laos and Cambodia limited self-government within the French movement. Most local nationalists accepted the new arrangement, but one Laotian prince, Souvanouvong, refused to trust the French. In 1950 he met with Ho Chi Minh and organized a Laotian communist movement, the Pathet Lao. At the same time a nationalist group called the Khmer Serei (Free Khmer) organized an army in the Cambodian jungle, committed to driving the French from Cambodia.

In December 1949 Mao Zedong triumphed in China, giving Ho Chi Minh a major ally at his back. Using modern artillery supplied from China, Giap now launched a new offensive. The French forts in Tonkin, often made of nothing more than palm logs and cement, were blown apart with alarming ease. By the fall of 1950 everything north of Hanoi was under Viet Minh control. In January 1951 the overconfident Giap threw 22,000 men against 10,000 French in the Red River delta. In the resulting battle 6,000 Viet Minh were killed and 8,000 were wounded, many by the bombs and napalm of the French Air Force. The French also had an excellent new commander, General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny. Once the Viet Minh were driven off, de Lattre constructed an array of defenses so elaborate that many called it a new Maginot Line. It succeeded in keeping Hanoi, Haiphong, and the Red River delta in French hands for the rest of the war, but at the cost of tying down more than half of the French army. De Lattre died of cancer less than a year after taking command, and his successors were never able to keep the initiative for long.

France granted complete independence to Laos in 1953. This did not satisfy the Pathet Lao radicals, who now raised the banner of revolt against both the Laotian government and the French. With Viet Minh help, the Pathet Lao gained control of two northeastern provinces (Phongsali and San Nua). The next 22 years would see a curious on-and-off struggle between princes for control of the government, a family quarrel on a national scale.

When Norodom Sihanouk was placed on the throne of Cambodia in 1941, he was expected to be a pliable leader, since he was only 18 years old at the time. After he grew up, however, he turned out to have more backbone than his Vietnamese and Laotian counterparts did. Late in 1953 he acted and won freedom for his country. In the theatrical manner that soon became his trademark, the young monarch went into exile swearing not to return until France quit Cambodia. The French could not endure the embarrassment of the situation, especially since the Cambodians were likely to rise up in revolt unless they got their king back. In November France yielded, and Sihanouk returned to Phnom Penh as the triumphant liberator of a fully sovereign kingdom.

One of General de Lattre's successors, General Henri Navarre, tried to win the war by transforming it into the dirtiest kind of conflict--war by attrition. His idea was to place an impregnable outpost in the heart of Viet Minh territory, and slaughter the Viet Minh as they made futile attempts to retake it. If all worked as planned the Viet Minh would be forced to call off their campaigns in the Red River delta and Laos as well. It was the same type of strategy that had been used at Verdun in World War I.

The site picked for the battle was Dienbienphu, a remote village on the Laotian border. In 1953 Navarre captured the village and started to build defenses around it. The valley in which Dienbienphu lay was vulnerable to heavy artillery fire, but Navarre believed (wrongly) that the Viet Minh had only light guns. Worse than that, he did not use any troops to occupy the high ground surrounding the valley; that alone ought to tell you that trouble is on the way. Finally, the vegetation around the valley was so dense that the enemy could not be attacked or even seen from the air. Even the strategic plan was cloudy; the local commander wanted Dienbienphu to serve as a base for anticommunist guerrillas, which had been used successfully in Tonkin already.

French soldiers in the trenches at Dienbienphu.

Giap took the bait, but he was fully prepared when he did so. For months he moved in men, supplies, and disassembled heavy equipment by bicycle under the jungle's cover. His army developed the art of tunneling to new levels of refinement, burrowing closer to the French lines every night. Howitzers and anti-aircraft guns were dragged through the tunnels to fire point-blank at the French defenses and airfield. When the siege began (March 13, 1954), the Viet Minh outnumbered the French by more than five to one. The French artillery commander at Dienbienphu, once confident that he could locate and destroy any Viet Minh gun before it fired three shots, was so upset over the situation that he blew himself up with a grenade on the third day of the battle; of course this did not help the morale of those left behind.

For 55 days the French perimeter was relentlessly reduced. The only way to bring in supplies was by parachute drops, now that the airfield was under attack. When the French officer in charge of aerial resupply ordered the planes to make their drops from 8,000 feet, instead of 2,000 feet, to keep them out of anti-aircraft gun range, a lot of crates missed the drop zone, and fell into the hands of the Viet Minh. Meanwhile the defensive outposts were captured one by one. French casualties reached grisly levels--8,000 dead, 12,000 wounded. Viet Minh losses were even higher, but they, unlike the French, were temperamentally suited for this type of warfare. Ho Chi Minh was aware of this early in the war when he told a French visitor: "You can kill ten of my men for every one I kill of yours. But even at those odds, you will lose and I will win." By April the French knew that only direct intervention by a major outside power could save Dienbienphu, but the United States was not yet willing to send troops to Vietnam; that would come a decade later.(4)

The Dienbienphu command post and its last defenders were overrun on May 7, 1954. For a long time France had been sick of the war; now the French were ready for peace at any price. On the following morning nine delegations met in Geneva, Switzerland, to plan Indochina's future. When they finished in July a cease-fire agreement was drawn up that gave independence to all of Indochina, with no strings attached. Laos was declared a neutral state, with a coalition government made up of both Pathet Lao and Royalist members. Vietnam was divided at the 17th parallel, into a communist north and an anticommunist south. For three hundred days people were allowed to move freely across the border, also called the demilitarized zone or DMZ. More than 100,000 Viet Minh guerrillas moved north, while 900,000 northern civilians (mostly Catholics who did not see a bright future under communism) migrated to the south. Elections to reunify the country were promised for July 1956. But in the long run the cease-fire accomplished little beyond the removal of the French. It depended on a political settlement to last, which never really happened. The peace it produced was merely an intermission between two Indochina wars.(5)

The Malayan Emergency

Because Malaya's colonial history was different from that of other Southeast Asian states, the path it followed to independence was different as well. The reasons for this were mentioned in Chapter 3: no nationalist movement before World War II, and the separation of Malaya's people into self-contained Malay, Chinese and Indian communities that did not get along very well. The Chinese and Indians, with their older, more sophisticated civilizations, looked down on the Malays, and the Malays resented the wealth of the Chinese and Indian newcomers. The Malays first became interested in politics in 1943, when the Japanese gave Malaya's four northern sultanates to Thailand. After the war the British had no trouble reestablishing control over the whole peninsula, but maintaining control was another matter entirely. The first (and most surprising) challenge came from the Malays; a second and far more dangerous challenge came from the Chinese communists.

The British had always felt it was unfair for the Malays to treat non-Malays like second-class citizens, so they overhauled the colonial government in April 1946. Political power was taken away from the nine sultans, and the entire peninsula was placed under the direct rule of King George VI. The new state created, the Malayan Union, included the nine sultanates plus Malacca and Penang, while Singapore remained a separate crown colony. Union citizenship and equal rights were offered to the Indians and Chinese. The sultans, however, resented being put out to pasture. Chinese and Indian apathy joined with Malay hostility to kill the scheme in less than two years.

When ceremonies were held to celebrate the birth of the Malayan Union, none of the sultans came. Then some Malay aristocrats formed a political party to oppose the Union, calling it the United Malays National Organization, or UMNO. It quickly became a full-blown nationalist movement. Alarmed that they had alienated a people that had long been cooperative and friendly, the British backed down. In February 1948 the Union was replaced with another government, the Federation of Malaya. Under this system the sultans regained their former powers, and the special privileges of the Malays were reaffirmed. Two concessions were made to the British, though: Kuala Lumpur remained the administrative capital, and a few non-Malays were granted full citizenship.

Once the Malays were satisfied, the Chinese communists raised the banner of rebellion. The communists were experienced in guerrilla warfare, having fought the Japanese in World War II. Now they called themselves the "Malayan Races Liberation Army," their goals being the expulsion of all Westerners and the establishment of a communist Malayan state. They started with a campaign of terrorism. Rubber trees were slashed; mining equipment was destroyed; transportation was disrupted. Malay policemen, European businessmen, and Chinese with progovernment sympathies became the targets of assassination squads. Because communist guerrillas were winning in China at the same time, the communists in Malaya thought they would win if they tried the same strategy.

But what worked in China was not going to work in Malaya. To begin with, the numbers were against the communists. The guerrillas never numbered more than 7,000; opposing them was an army of 40,000, a police force of 67,000, and a Home Guard of 350,000. To help the Malays, the British brought in Scots highlanders, English riflemen, and fearless Gurkhas from Nepal. While they took part in what they called "jungle bashing," 525 million leaflets were dropped into communist areas. Informers were paid huge sums, and a price was put (both literally and figuratively) on the heads of the guerrillas. Equally helpful was the fact that the guerrillas were almost all Chinese, making the task of identifying and separating them from the rest of the population relatively simple. The Malays and Indians could be counted on to be loyal during the period the British called "The Emergency"; victory would be certain if Britain gained the favor of the Chinese community as well.