| The Xenophile Historian |

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 5: Pax Americana, Part IV

1933 to 2008

This paper is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| First, an Explanation of the Title | |

| The New Deal | |

| New Deal II | |

| Getting Out of the Depression--The Hard Way | |

| The Gathering Storm | |

| Pearl Harbor | |

| World War II |

Part II

| The Country Boy From Missouri | |

| Enter the Cold War | |

| China, Korea, and the Pumpkin Papers | |

| "I Like Ike" | |

| Life in the 1950s |

Part III

| The "New Frontier" | |

| Who Really Killed JFK? | |

| The "Great Society" | |

| Nixon Returns | |

| "All the President's Men" |

Part IV

| Years of "Malaise" | |

| The Reagan Renaissance | |

| George Bush the Elder | |

| Clintonism | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part V

| The Clinton Scandals | |

| Islamism on the Move | |

| The Battle of the Ballots | |

| George Bush the Younger | |

| Angry Democrats, Drifting Republicans | |

| Modern American Demographics | |

Years of "Malaise"

Gerald Ford got along with nearly everybody, making him the one who could heal the nation after Watergate, but otherwise he had no outstanding abilities. As a political moderate, he didn't rock too many boats, either. He had been a football star at the University of Michigan in the 1930s, and like Kennedy and Nixon, served as a navy officer during World War II. In 1948 he ran for the House seat representing Grand Rapids, MI, and held it for the next twenty-five years, until he became vice president. From 1964 onward he was the House Minority Leader as well, but remarkably, during his whole tenure in Congress, he never wrote a piece of major legislation, preferring instead to arrange compromises on the bills introduced by others.

Democrats like to believe that Republicans aren't too bright, and they made jokes about Ford for that reason. It didn't help that an old knee injury from his football days caused him to frequently stumble, especially when somebody was standing nearby with a camera. Comedian David Steinberg compared Ford with a ventriloquist's dummy ("He looks and talks like he just fell off Edgar Bergen's lap"), while Chevy Chase made himself the star of Saturday Night Live by doing Gerald Ford impersonations. Ford also had the misfortune of being president when the Vietnam War finally ended. By the beginning of 1975, the Communists had stopped paying even lip service to the cease-fire. Last-ditch efforts to send aid to Cambodia and South Vietnam were rejected by Congress, and in April 1975 both Phnom Penh and Saigon fell to Communist offensives. Those who believed in the "Domino Theory" saw their fears confirmed a few days later when the Communists seized power in Laos, thereby bringing all of Indochina under Communist rule. For the Americans, the last scenes of the war were humiliating ones, with Americans and a few lucky Vietnamese being evacuated from the roof of the US embassy by helicopter. The North Vietnamese then set up reeducation camps for their newly conquered subjects, while the Khmer Rouge simply killed theirs in the notorious "killing fields"; American Leftists spent the rest of the 1970s denying that these atrocities were actually happening. If the author's generation is accused of not talking much about the Vietnam War, there's a good reason; it was the first war that the United States lost. On the other hand, Ford had the good luck of being president for the nation's 200th birthday, the Bicentennial, in 1976 (see below).

Vietnam and Watergate left much of the American public disgusted with politics as usual. Moreover, President Ford was saddled with a poor economy and the unpopular act of pardoning Nixon. Thus, voters were eager for fresh faces. The 1974 elections gave them some, with many new (mostly Democratic) members elected to Congress. For the 1976 presidential election, three prominent Democrats had run the last time around: George Wallace, Washington Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson, and Sargent Shriver. Hubert Humphrey also hinted that he would run one more time, though in the end he chose not to do so. However, you could guess from the general mood that the winner would be somebody who didn't work in the District of Columbia. The "outsider" candidates were former Georgia Governor Jimmy (James Earl) Carter, and two California governors, Ronald Reagan and his successor, Jerry Brown. Reagan challenged Ford for the Republican nomination by telling Republican voters that it is no sin to turn out a weak incumbent.

Jimmy Carter was virtually unknown on the national scene, and he used that to his advantage, since it made him appear free of Washington corruption. He also used his humble background as a peanut farmer and a former naval officer the same way. By entering every primary and caucus except West Virginia (where a favorite son, Senator Robert Byrd, had claimed all the delegates for himself), Carter made sure he was always making headlines somewhere. Sure enough, he won the first caucus, in Iowa, and then others started to pay attention. After that, throughout the primary campaign he knocked off his Democratic opponents one by one. Although he did not win every primary, he was always in the lead with delegates, and while Jerry Brown and Idaho Senator Frank Church gave him a challenge toward the end, both of them entered the race too late to catch up with Carter.

Jimmy Carter.

Carter had no trouble winning on the first ballot at the Democratic convention. The Republican primary campaign, however, was stormier than expected. At first Ford won key states like New Hampshire, Florida and Illinois, and it looked like the Republican convention would be a blowout for him. Then the campaign reached more conservative states like North Carolina and Texas, and Reagan won enough of those to close in on Ford's lead. Ford did get a first-ballot nomination at the Republican convention, but it was so close that the uncommitted delegates could have decided it either way, so during the summer Ford and Reagan scrambled to get the support of uncommitted delegates, giving the red carpet treatment to those folks. Afterwards, Ford dropped Nelson Rockefeller, who had been a reluctant supporter of his administration, and nominated Kansas Senator Bob Dole as a new running mate.

For the fall campaign, Ford had the advantage of incumbency--no incumbent president had been voted out of office in forty-four years--and he used that by looking presidential at various events, like the celebrations of the US Bicentennial. Meanwhile, Carter won over Southern conservatives by portraying himself as a more authentic Southerner than previous Southern presidents like Truman and LBJ, and let them know that he was a born-again Southern Baptist, too. The campaign turned less on issues than on personalities--and on embarrassing gaffes. Carter had some explaining to do when he gave an interview to Playboy Magazine, while at the second debate, Ford declared that the Soviet Union did not dominate eastern Europe, despite thirty years of evidence to the contrary.(70) On Election Night, the result was close, and an east-west split, instead of the more common north-south one. Ford won every state in the West except Hawaii and Texas; while Carter won every state in the South except Virginia (this made him the last Democratic candidate to carry more than half of the South). What decided the election was the Northeast, where Carter won just enough votes to put him over the top.

Jimmy Carter was full of good intentions, and unlike George Wallace, he represented the post-segregation "New South." However, he did not have the experience that most presidents have by the time they get elected, so his administration showed that the White House is no place for on-the-job training.(71) His promise in 1976, to give the nation a government "as good as the American people," would be seen as cruel joke before he was through. His first act after taking office was to grant a blanket pardon to everyone who had dodged the draft during the Vietnam War, thereby settling a issue that had been contested for the past few years. However, he was unable to do anything about the economic and energy problems he had inherited from the "Nixon-Ford administration." For his first speech on energy, he encouraged conservation by wearing a cardigan sweater for his first televised speech on energy, and called the energy crisis the "moral equivalent of war"; never mind that the American people were tired of any kind of war, and didn't like being preached at. For the economy, he simply repeated what his predecessors had tried--more price controls and more government programs.(72) The good news is that he began to deregulate some key industries to increase competition, especially trucking and the airlines, and Paul Volker, his appointment to head the Federal Reserve Board, would succeed in reducing inflation, but not until after Carter left office.

In foreign policy, Carter scored three noteworthy successes: Panama, China and the Middle East. In Chapter 4 we saw how the United States acquired the land where the Panama Canal was dug; Theodore Roosevelt's heavy-handed methods, though successful, had hurt relations between the US and its southern neighbors. To mend those fences, Carter negotiated a treaty with the Panamanians in 1977, that promised to give the Canal to Panama on the last day of 1999. The treaty was unpopular with most Americans, because Panama was ruled by a left-wing dictator at the time, Omar Torrijos, so Carter had to twist several arms to get it ratified by Congress. Late in the 1980s, another Panamanian dictator, Manuel Noriega, threatened to derail the treaty with his anti-American behavior, but he was quickly deposed by a US invasion, and the Canal changed ownership on schedule.

Carter granted diplomatic recognition to Red China in 1979, thereby completing the process of normalization with that huge country, making possible all the trade between China and the West that exists today.(73) By this time Mao Zedong had been succeeded by moderates who were more interested in economic growth than ideology, like Deng Xiaoping, so there was some hope that China would become more like the United States in respecting freedom, too. Unfortunately, the promising movement in that direction came to an abrupt halt a decade later, with the bloody suppression of the 1989 pro-democracy demonstrations in Tiananmen Square.

In the Middle East, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat broke the current stalemate between war and peace by visiting Israel. Carter encouraged this trend, and hosted a summit meeting at Camp David in Maryland between Sadat and Israel's Menachem Begin. The result was the first (and still the most successful) peace treaty between Israel and the Arabs, signed at the White House in March 1979.(74)

Carter also tried to reach an agreement with the Soviet Union, called SALT II, because it followed up on the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks held between Nixon and Leonid Brezhnev. However, while the Soviet Union talked peace, it was also sharpening its sword, building more missiles instead of reducing the number, and working to spread communism to new places like Angola, Ethiopia, and Afghanistan. In eastern Europe, the Soviets deployed medium-range SS-20 missiles, which raised new fears among Western commanders because they would be harder to track than long-range ICBMs. By the time of the Carter presidency it was obvious that the USSR wasn't keeping most of the agreements it had made, so Congress, though it was Democratic-controlled, refused to ratify the agreement. At the end of 1979 the Red Army, encouraged by the Iranian Revolution (see below) and the breakup of CENTO (the Middle East equivalent of NATO), invaded Afghanistan, replaced the current Afghan leader with one more obedient to Moscow, and began fighting a Moslem rebellion that had sprung up there. Carter already had all he could handle with Iran, so the only things he did to punish the Soviets were to introduce some trade sanctions, and boycott the 1980 Summer Olympics, which were held in Moscow. We'll come back to the Afghanistan conflict later in this chapter, because it is still one of the world's big hot spots today.

Elsewhere, Carter declared that henceforth, the United States would emphasize more human rights and less realpolitik. Previously, in order to fight communism, the United States had allied itself with several unsavory monarchs, dictators, and presidents-for-life, as if being anticommunist covered a multitude of sins. Besides South Vietnam, examples of right-wing, pro-American tyrants included those in Chile (Augusto Pinochet), Greece (Georgios Papadopoulos), Iran (Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi), Nicaragua (Anastasio Somoza), Pakistan (Muhammad Zia-ul Haq), the Philippines (Ferdinand Marcos), Saudi Arabia (the Saudi royal family), South Africa (Balthazar John Vorster), and South Korea (Park Chung Hee). Now Carter told those rulers to shape up, if they wanted to continue receiving US aid and arms. But it is one thing to speak idealism; it is far more difficult to make it work. Two cases in particular caused problems that the United States is still dealing with, thirty years later.

One of them was right in the USA's Central American backyard. The Somoza family had ruled Nicaragua for two generations, and in the late 1970s it faced a rebel movement, the Sandinistas. In 1979 Carter announced the US would no longer support the Somoza regime, citing human rights concerns, and Somoza fled the country. However, the Sandinistas turned out to be Marxists, so Nicaragua now joined Cuba as the second communist state in the western hemisphere. Carter and the US found out the hard way that when you replace one dictator with another, the result is not an improvement, because the new dictator is likely to be less friendly to the United States, and more brutal to his subjects. The Sandinistas weren't as ruthless as Fidel Castro (their leader, Daniel Ortega, stepped down after losing an election in 1990), but because Soviet aid to them is a violation of the Monroe Doctrine, US leaders, especially Reagan, found them an embarrassment. In fact, Ortega is back in charge now, having been elected again in 2006.

The other case, Iran, was far worse; it brought down Carter's presidency, and Iran is an ongoing threat to today's world. The Shah had been one of the most dependable pro-Western allies in the Middle East: strongly anticommunist, but more progressive than the Arab kings and sheiks around the Persian Gulf. He also got along well with Israel, and was a great customer of American-made military equipment. As the 1970s went on, however, stories of imprisonment and torture at the hands of SAVAK, the Iranian secret police, leaked out, and these dispelled the good image the Shah had previously. When opposition to the Shah turned into a full-scale revolution, Carter withdrew US support, and in January 1979 the Shah left Iran. His main opponent, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, returned from exile, set up a theocracy that was called an "Islamic republic," began supporting Islam-based terrorism around the world, and declared that henceforth, Iran would be the enemy of both the "Great Satan" (the United States) and the "Little Satan" (Israel). For the US, this meant another round of rising gas prices, and cars waiting in long lines at gas stations. But that was only the beginning. When the Shah came to the United States later in the year to be treated for cancer, Iranian militants seized the US embassy in Tehran, holding it and its personnel hostage and demanding that the Shah be handed over to them.

Carter failed to show a strong hand in the Iranian hostage crisis; first he said he would not negotiate with the kidnappers, but later did so anyway; and instead of standing firm, he changed his position more than once. He also promised not to use force to rescue the hostages, so when he later had to admit that a commando rescue team had crashed in the Iranian desert, instead of going on to the embassy, it was especially humiliating. Iran was delighted at all the attention it was getting, so it played the crisis to the limit; most of the hostages were held for a total of 444 days. They were finally released on the morning of January 20, 1981, in the last hours of Carter's presidency, because the Iranians knew they could not manipulate Reagan so easily.

At times during Carter's term, it seemed that nothing could go right. To combat inflation, the Federal Reserve raised the prime interest rate to an all-time high, from 11% in 1979 to 20% in 1981 and finally 21.5% in June 1982. Some economists wondered out loud how long the United States could survive such a burden. In 1979 there was a strange incident where Carter went fishing in Georgia and a rabbit swam up to his boat, hissing; Carter knocked it away with an oar. Though he won the confrontation and the rabbit was probably rabid, or otherwise sick, Republicans were quick to point out that Carter was the only president a rabbit would attack. Also in 1979 came his most important speech. During the second energy crisis, he declared that Americans were suffering from a "crisis of confidence," due to the JFK assassination, Vietnam and Watergate, and that Americans weren't doing enough to change their energy-consuming habits. Although he didn't use the word "malaise," this came to be known as the "Malaise Speech." It gave him a brief boost in the polls for speaking honestly, but after that Republicans accused him of saying that something was wrong with the American people. Three days after the speech, Carter asked his entire Cabinet to resign, and five members did. For the rest of Carter's time in the White House, his message was one of pessimism, while the Republicans in turn showed themselves as optimists.(75)

In the 1960s, Arthur Okun, an advisor to President Johnson, invented the Misery Index, a simple way to measure public discontent. By adding the annual inflation rate and the current percentage of unemployed workers, it calculates that the higher the result, the more unhappy Americans will be, and various economic and social costs, from government expenditures to the number of crimes and suicides, will rise with the index. Calculations start with 1948, perhaps because before that time, deflation was more common than inflation. The lowest misery index rating was 2.97%, in July 1953, and the highest was 21.98%, in June 1980. Here is how it averaged out under each president:

| President | Years in Office | Average Misery Index |

| Truman | 1948-1953 | 7.88 |

| Eisenhower | 1953-1961 | 6.26 |

| Kennedy | 1961-1963 | 7.14 |

| Johnson | 1963-1969 | 6.77 |

| Nixon | 1969-1974 | 10.57 |

| Ford | 1974-1977 | 16.00 |

| Carter | 1977-1981 | 16.26 |

| Reagan | 1981-1989 | 12.19 |

| Bush the Elder | 1989-1993 | 10.68 |

| Clinton | 1993-2001 | 7.80 |

| Bush the Younger | 2001-2009 | 8.10 |

| Obama | 2009-2017 | 8.83 |

| Trump (first term) | 2017-2021 | 6.91 |

| Biden | 2021-February 2024 | 10.16 |

When he was running for president, Carter frequently mentioned the Misery Index. In the summer of 1976 it stood at 13.57%, and Carter said that no man who gave the country a misery index that high has the right to even ask to be president. However, it climbed even higher under his watch, to the all-time high of 21.98%. No wonder Carter wasn't reelected.

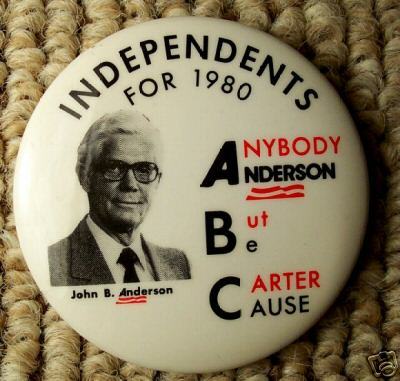

By 1980, the combination of "stagflation," high unemployment, high interest rates, high energy prices, Iran, and Jimmy Carter's lack of accomplishments convinced many voters that he was incompetent; one of the year's slogans was, "ABC: Anyone But Carter!" Still, few Democrats were willing to run against him. The only ones who presented a challenge were Massachusetts Senator Teddy Kennedy and California Governor Jerry Brown. Kennedy had stayed out of the 1972 and 1976 campaigns, because people couldn't think of him without also thinking of Chappaquiddick, but in 1979 he decided that this was his best chance to win, so he threw his hat into the ring. Polls taken in the fall of 1979 showed him running well ahead of Carter in popularity, until the Iranian hostage crisis began; that caused the public to return to the president for the time being (the "rally 'round the flag" effect). Among the primaries and caucuses of early 1980, Carter won thirty-seven to Kennedy's twelve, but Kennedy waited until the Democratic convention to concede. As for Brown, few voters took him seriously, and he only won the Michigan primary. For the Republicans, eight candidates ran, but because of his close second-place finish in 1976, Ronald Reagan was the favorite from the start. The only Republican besides Reagan to win any primaries was Gerald Ford's CIA director, George Herbert Walker Bush, so Reagan had no trouble getting the GOP nomination. Then in a move to unify the party, Reagan chose Bush as his vice-presidential candidate. The only Republican who didn't accept these results was the candidate who came in third place, Illinois Representative John B. Anderson. Consequently, after the conventions Anderson ran as an independent, offering himself as a liberal alternative to Reagan.

A John Anderson campaign button.

As 1980 continued, the news did not get any better. Many Americans tuned out altogether; those who remember 1980 will tell you that people were more interested in knowing "Who shot J.R.?", than who would win the election. A Carter speech that called for halting inflation through economic self-discipline was dismissed as "More Mush from the Wimp" by a Boston Globe editorial.(76) The Iranian hostage crisis dragged on for so long that it caused a backlash, driving Americans away from Carter, instead of to him. To counter Reagan's optimism and Anderson's new ideas, Carter portrayed himself as the only one of the three with experience at handling a dangerous world. When that didn't work, he increasingly resorted to negative campaigning, trying to paint Reagan as a reactionary who would turn the clock back on civil rights and probably start a war; Carter also refused to recognize Anderson as a legitimate candidate. When the first debate of the campaign came up, Anderson was invited to attend, and Carter acted downright petty by refusing to show up; thus, the debate ended in a draw because Reagan and Anderson spent more time criticizing Carter than each other. For the second debate, Carter insisted that he would not appear on the same stage as Anderson, while Reagan insisted that Anderson be allowed in. Eventually Reagan gave in, Anderson was excluded, and the second debate was held just one week before Election Day. This time the result was a blowout victory for Reagan. When Carter attacked Reagan's record as governor, Reagan responded with a cheerful reprimand: "There you go again." For his closing statement, Reagan asked the voters a question that was both simple and devastating: "Are you better off now than you were four years ago?"

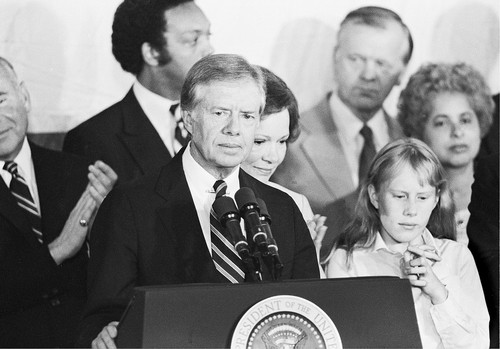

Whereas 1932 saw a Republican incumbent toppled in a landslide, the results for the 1980 presidential election were just the reverse; the Democratic incumbent (Carter) only carried only six states and the District of Columbia. The voters also handed over the Senate to the Republicans, the first time the GOP had gained control over either house of Congress in nearly thirty years. Before 1980 non-conservatives saw Reagan as another Goldwater, too extreme and too ignorant to be trusted with the White House. Now, Reagan offered the nation a chance at a new beginning; that and Carter's ineptness had made Reagan acceptable to a majority of the American people. For those reasons, we consider the 1980 election transformational, in that it broke the Democratic majority that had existed since the Depression.

Carter's concession speech, Election Night 1980.

After 1980, conservatives expressed the view that Carter was the worst president the United States ever had; a few liberals agreed, though they were quick to point out that they thought the worst thing Carter did was give them Ronald Reagan. Calling himself "involuntarily retired," Carter grew bitter, and the big toothy grin that had been Carter's trademark in 1976 was no longer seen very much. For most of the 1980s, he stayed out of the limelight; his main activity was to promote Habitat For Humanity, a charity dedicated to building homes for people who otherwise couldn't afford them.(77) In 1994 Carter went to North Korea and worked out a peace agreement with the northern strongman, Kim Il Sung; at the time it looked like Carter was on a private mission, but he really went as Bill Clinton's special agent. Eight years later, however, the agreement fell apart when Kim Il Sung's successor, Kim Jong Il, announced he would not honor it, and resumed North Korea's nuclear program. When not busy with North Korea, the former human rights advocate met with enemies of the US like Yasser Arafat, Fidel Castro(78), Syria's Hafez al-Assad, and Venezuela's Hugo Chavez, as if his motto now was "I never met a dictator I didn't like." He claimed that all of the above leaders "have at times been misunderstood, ridiculed and totally condemned by the American public," in part because they didn't have Anglo-Saxon names!

After 2000, Carter became a vocal critic of US foreign policy, denouncing George W. Bush and the Israelis at every opportunity.(79) In the past, most presidents had gone easy on their successors (Theodore Roosevelt was the main exception to this rule), so Carter's bad-mouthing was seen by some as an effort to undermine the United States. For that he earned the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002; a member of the Nobel Committee, which was also hostile to Bush, freely admitted that he gave Carter the prize for political reasons, not for anything he had done to promote peace. In 2004 Carter said in an MSNBC interview that he thought the American Revolution was "unnecessary," and that it could have been avoided if Britain's Parliament had been more sensitive to the grievances of its colonial subjects (compare this with Chapter 2, footnote #29). This makes folks like the author wonder why he ran for president in the first place, if he would have preferred being a "prime minister" or "governor-general." Then in 2009, when large numbers of people started criticizing Obama's policies, Carter topped it off by suggesting that racism was the real reason for their dissent; even the Obama White House rejected that charge. Still, because Carter lived to see the Biden presidency, he must have ended his life knowing that he wasn't the worst president after all.

The Reagan Renaissance

Ronald Wilson Reagan was a different kind of president. The main difference was that he was the only real conservative in the period covered by this chapter. The other Republican chief executives (Eisenhower, Nixon, Ford and both Bushes) were more moderate than conservative, while the Democrats have not produced a conservative president since Grover Cleveland. Born in Illinois, Reagan got his start after college as a Des Moines sportscaster. In 1937 he followed the Chicago Cubs to a game in California, took a screen test while he was there, and won a seven-year contract with Warner Brothers Studios. During the next twenty years he played in fifty-three films, most of them so-called "B pictures," where the producers made filler material, unimpressive films to go alongside the feature presentation. As Reagan later joked, the producers "didn't want them good, they wanted them Thursday." He didn't try hard to land starring roles for himself, but managed to get one in "Knute Rockne - All American," where he played the football player George Gipp, earning him the nickname of "the Gipper." His favorite movie and his best part, though, was "Kings Row," a drama about young people growing up in a small Southern town in the 1890s. In the most memorable scene, a crazed surgeon needlessly amputated the legs of Reagan's character, to keep him away from his daughter, and when Reagan woke up to find his legs missing, he cried out, "Where's the rest of me?" That line would become the title of his 1965 autobiography, because by then Reagan had decided there was more to life than acting. In 1937 he also enlisted in the army's cavalry division, and thus was called to active duty after the United States entered World War II. Nearsightedness kept him from serving overseas, but his skills as an actor allowed him to make several training films (compare this with footnote #13), and he rose to the rank of captain by the war's end.

When Reagan first appeared in this chapter (footnote #34), we noted he was a liberal Democrat, like so many other folks in Hollywood. Well, his views changed from liberal to conservative after the investigation of communism in the film industry; as the saying puts it, "A conservative is a liberal who got mugged the night before." Another factor was his success; successful people tend to be more conservative than unsuccessful folks. In the late 1950s he moved to television, getting hired as the host of "General Electric Theater." Because television had replaced movies as the most popular entertainment medium, this part earned him more than he ever made in the movies: about $125,000 a year, or $1 million in 2008 dollars. By the time of the 1964 election he was a Republican, and he announced his entry into politics with a pro-Goldwater speech, "A Time for Choosing." His last acting part was hosting a TV western, "Death Valley Days," in 1964 and 1965. In 1966 he ran for governor of California, won by a million votes, and did well enough to get reelected in 1970.

Ronald Reagan.

From the start, Reagan let it be known that his administration would not allow the current "malaise" situation to continue; at his first inaugural address, he declared, "Government is not the solution to our problems; government is the problem."(80) His first priority was to restore the military, which was in bad shape as the 1980s began, by giving it a massive increase in the defense budget. He also restored the program to build the B-1 bomber, which had been scrapped by Carter. For his domestic policy, Reagan favored laissez-faire capitalism, which under him was known as "Reaganomics." To stimulate non-government spending, he cut the highest federal income tax rate from 70 to 28 percent. The high interest rates imposed by the Federal Reserve Board caused a serious recession early in Reagan's first term, but they succeeded in bringing down inflation, too. Stable prices and the tax cuts created new jobs at the same time, and produced a period of prosperity that lasted from 1983 to 1989, which now is sometimes called "The Seven Fat Years." Likewise, the removal of price controls on oil ended the oil shortages of the 1970s, and kept the price of energy stable for most of the next two decades.

The intelligentsia of American society could not understand Reagan's success. It did not make sense to them that a second-rate actor could also be a first-rate politician, outwitting them to win two elections for governor and two for president. Nor did they believe that he could accomplish more with common sense than they could accomplish with all their learning. He just seemed too sincere and simple to them; nobody doubted what he believed or wanted. On the other hand, he was popular among ordinary Americans for exactly the same reasons; his FDR-like appeal to them caused the media to call him the "Great Communicator." They also liked his optimism, and his sense of humor. For example, two months after becoming president, he and his press secretary, James Brady, were shot by John W. Hinckley, a deranged young man who thought this act would win the love of his favorite actress, Jodie Foster. Brady was left paralyzed for life, while the bullet that hit Reagan missed his heart by an inch. When he reached the operating room, Reagan joked, "I hope you're all Republicans!" and one of the surgeons replied, "Today, Mr. President, we're all Republicans." Fortunately he made a rapid and complete recovery after the bullet was removed.

In the summer of 1981, Reagan got a challenge from the Professional Air Traffic Controller's Union (PATCO). The nation's air traffic controllers felt they were overworked in a very stressful job, and went on strike, though it was against the law for government employees to do so. The strike threatened to paralyze the nation's economy, and Reagan announced that those air traffic controllers who did not return to work would be fired. Though it took quite a while to train enough new air traffic controllers to replace the old ones, Reagan stood firm, and PATCO went out of business.

The air traffic controllers' strike was a symbol of the bureaucracy Reagan had promised to fight, but he wasn't able to accomplish as much in the battles over government growth and spending. While liberals warned of Draconian cuts in everything but the armed forces, in the end they did not happen; he never threatened to shut down the government by vetoing a budget, the way Clinton would do. Moreover, he never cut Social Security, though senior citizens had been led to believe he would, and spending on social services grew until it was a bigger portion of the budget than defense spending. Nor did he undo the Great Society or the New Deal; he just limited their worst effects. It took until his second term for Reagan to gain control over the growing budget deficit, and he did it by signing the Tax Reform Act, which raised taxes by getting rid of some loopholes and tax credits. When it came to the budget, and the social issues that he and the "Religious Right" supported (e.g., see footnotes #60 and #82), Reagan may have been too easygoing.

In foreign policy, Reagan learned that the US must choose its fights. He stayed out of the 1982 war between Britain and Argentina over the Falkland Islands, but then committed American soldiers as part of the UN multinational peacekeeping force, which went to Lebanon to end that country's civil war. The following year saw the troops come under attack from some of the first suicide bombers, who crashed trucks full of explosives into foreign-owned buildings. The worst attack hit the US Marines Barracks, killing 241 servicemen. Instead of retaliating, Reagan ordered the rest of the American force to withdraw in 1984. When retaliation did come, it was in 1986, as American warplanes bombed Libya, one of the biggest sponsors of international terrorism. However, the United States did much better in the Caribbean, where American troops landed on Grenada to depose the communist government there, before it turned that island into another Cuba (1983).(81)

Bringing down the Soviet Union was Reagan's greatest accomplishment, and he did it without firing a shot. At a 1983 speech to evangelical Christians in Orlando, FL, Reagan made it clear that he would not appease the Soviets, when he called the USSR an "Evil Empire." The shooting down of a Korean airliner by Soviet warplanes later in the same year helped to confirm what Reagan had said; he called the act a "massacre" which went against the world's moral principles. In Afghanistan he provided arms and training to Moslem rebels (the Mujahideen) fighting Soviet occupation, turning that country into a Russian version of Vietnam. On the European front he deployed Pershing II missiles in West Germany, as a counterweight to the recently deployed Soviet SS-20 missiles, ignoring widespread protests by peace demonstrators in Europe as he did so. Great Britain had also recently elected a strong-willed conservative prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, and in her Reagan had the ally he needed to resist Soviet expansion in Europe.

Early in the Cold War, there had been talk of stopping nuclear missiles by intercepting them with anti-ballistic missiles (ABMs). That ended with the signing in 1972 of a treaty that banned ABMs, and nobody had a defense against nuclear weapons after that. Then in 1983 the United States launched a program to develop a network of ground and space-based lasers, guided by the latest software, to shoot down enemy missiles. Supporters of the program called it the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), while detractors, thinking of the "Evil Empire" speech, dubbed it "Star Wars," as if they believed Reagan had been watching too many science fiction movies. It seemed barely possible that American scientists could pull it off, and the United States had the resources and finances to give it a try. That was the most important point of the SDI, whether or not it worked; the USSR did not have either the technology or the money to build anything matching it. The Soviets supported a first-rate army and air force with an economy far inferior to that of the United States, so that whereas Western leaders could debate on whether their budgets should spend more on guns or butter, for the Soviets, the "guns" argument won almost every time. What's more, in the generation since the space age began, the Soviet had lost their edge in research. Their greatest scientists, like Andrei Sakharov and Yuri Orlov, later became dissidents, letting the world know about the abuses of their regime, and because Moscow didn't want to use them anymore, they weren't in their labs to follow up on past achievements like the hydrogen bomb and Sputnik I. Finally, there was concern that if the Americans succeeded in building the lasers, they might someday be used in an offensive capacity, as first-strike weapons in space. By out-researching, out-building and out-spending the Soviets (call it a modern-day form of potlatching), Reagan speeded up the collapse of the Soviet Union that would come under his successor.

If you thought Reagan's landslide was big in 1980, it was even bigger when he ran for re-election in 1984. As the election process began, almost everything was going his way; the nation's morale was restored, the armed forces had been rebuilt, inflation had been tamed, and the economy was booming. Only two trends did not favor the Republicans. First, there was runaway federal spending; the national debt first went above the $1 trillion mark in Reagan's first term, and the annual budget deficit was at an all-time high, approaching $200 billion in 1984. Second, Cold War tensions were at their highest in twenty years, because during Reagan's first term, there had been no summit meetings between the USA and USSR, to discuss nuclear disarmament or anything else they might disagree on. However, nature was to blame here, because the Soviet leaders, Leonid Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, were senior citizens who did not surprise anybody when they died. Reagan was the oldest president in American history (he was 69 when elected, and completed his second term just before his 78th birthday), but he looked youthful and vigorous compared to his Soviet counterparts.

Under those conditions, a Republican victory was the most likely conclusion. But neither major party was going to skip an election, so for 1984, eight Democrats ran. Only three of them won any primaries: Walter F. Mondale (Jimmy Carter's vice president), Colorado Senator Gary Hart, and the Rev. Jesse Jackson. Mondale represented traditional "New Deal" liberalism, while Hart appealed to younger, "Yuppie" voters, and Jackson generated interest because he was a well-known black activist. Because he had a lead in delegates and endorsements from the start, Mondale won the nomination, but Hart came in close enough that it had to be decided at the convention. Traditionally conventions were also the place where vice presidential candidates were picked, but Mondale ended this tradition by choosing the first woman veep, Rep. Geraldine Ferraro of New York, one month earlier.(82) Otherwise he toed the liberal line perfectly, to the point that he promised to raise taxes if elected. He reasoned that whoever won the election was going to have to raise taxes to balance the budget, so he might as well be honest about it, but as you might expect, that didn't go over well with the voters. In November the result was very much like what had happened the last time the Democrats nominated a doctrinaire liberal (McGovern); Reagan won 49 states easily. Even traditional Democratic strongholds like Massachusetts went for Reagan; the only places where Mondale came out ahead were in the District of Columbia, which always votes Democratic, and his home state of Minnesota.(83)

In March 1985, the Soviet Union finally got a secretary-general who was young enough to get things done. This was 54-year-old Mikhail Gorbachev. Gorbachev assumed a leadership role in the Politburo even before he succeeded Chernenko; Margaret Thatcher met him during this time, and the "Iron Lady" was impressed, declaring, "I like Mr. Gorbachev; I can do business with him." Acting on that recommendation, Reagan met with Gorbachev in November 1985, in Geneva, Switzerland. They got along well enough at the first meeting, but at the second, held a year later in Reykjavik, Iceland, sharp differences arose between the two sides, prompting Reagan to walk out on Gorbachev. On a visit to Germany in 1987, Reagan stood before the Berlin Wall and threw Gorbachev a challenge: "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!" At the time, it seemed far-fetched that the Cold War could end so soon, but indeed the wall came down, just two and a half years later.

Despite the rift at Reykjavik, both sides kept talking; Reagan and Gorbachev met twice in 1987, at Washington, D.C., and at Moscow. By this time, Gorbachev was desperate to find a way to cut defense spending, so the breakthrough came here: at the White House they signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, which eliminated all short and medium-range nuclear missiles. Gorbachev now turned his attention to getting the Red Army out of Afghanistan, and solving his country's domestic problems before they tore the USSR apart.

For Nicaragua, Reagan followed a similar approach to Afghanistan; the United States armed a rebel movement, the Contras, that was now fighting the Sandinistas. However, many Democrats in Congress had an attitude that can be described as "anti-anti-communist," and they eventually banned funding for the Contras. The Reagan administration found a way around this, though, in the ongoing Persian Gulf War between Iran and Iraq. When the war had first broken out, the feeling was that Saddam Hussein's secular dictatorship wasn't quite as bad as Ayatollah Khomeini's religious dictatorship. But as time went on, the US decided that it didn't want Iraq to win too easily, and an effort was made to improve relations with Iran, so that the Iranians could help free six Americans being held hostage in Lebanon. In 1985 members of the National Security Council, led by Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, began covertly selling surplus weapons to a moderate Iranian faction, with some help from Israel. Then the profits from those sales went to the Contras.

Word of this arrangement broke out late in 1986, and the press called the "Iran-Contra Affair" the worst scandal of the 1980s. Reagan denied knowledge of the affair, except that he had authorized the sale of some arms to Israel that went to Iran instead. He authorized the creation of a special commission to investigate, led by Texas Senator John Tower. A special independent counsel, Lawrence Walsh, was also appointed to investigate, while the International Court of Justice ruled that the US had broken international law by interfering in Nicaragua's affairs.

In the first week after the scandal was reported, Reagan's popularity dropped from 67 to 46 percent, the fastest decline any president has ever suffered in the polls. Oliver North and his commanding officer, Admiral John Poindexter, were indicted and convicted on several counts of conspiracy, lying to Congress, obstruction of justice, and altering/destroying documents pertinent to the investigation, but those convictions were later overturned. Moreover, no evidence ever turned up of Reagan being involved. Consequently the public lost interest in Iran-Contra before the media did, and Reagan's enemies did not bring down the administration with a second Watergate. Walsh continued his investigations until 1993, but the only additional indictment he brought up was for Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger, and a pardon of Weinberger by President Bush in 1992 kept him from going to trial. Nowadays Iran-Contra can be seen as a neat diplomatic trick, because it weakened three enemies of the United States: Iran and Iraq were bled white in an eight-year-long conflict that resembled World War I, and the Sandinistas were worn down to the point that they tried to prove they were still popular by holding free elections--which they lost.

George Bush the Elder

The political atmosphere in 1988 was a lot like it was in 1984; the nation's economy and foreign policy were still strong, and most voters did not see Iran-Contra as a big deal. In fact, an attempt to pin Iran-Contra on Vice President Bush backfired, when CBS news anchor Dan Rather asked Bush what his role was in the affair, and Bush came out the winner in the heated verbal exchange that followed.

Reagan was not allowed to run again, so both major parties put forth several candidates for the 1988 presidential election. The only Republican candidate as conservative as Reagan was TV evangelist Pat Robertson, but they all promised to act like Reagan if elected. Because the Reagan influence was so strong, his endorsement of Bush made him the voters' first choice, and eventually the nominee. On the other side of the aisle, the Democrats needed someone who was not an obvious New Dealer, or too far to the left to be electable. None of their eight choices looked very promising, and one of them was Colorado Representative Pat Schroeder, so some observers called the candidates "Snow White and the Seven Dwarves." Schroeder dropped out before the first primary, while Colorado Senator Gary Hart and Delaware Senator Joe Biden fell to scandals during the primary campaign. Jesse Jackson also ran again; in fact, he did better this time than in 1984. In the end the Democrats chose the technocratic governor from Massachusetts, Michael S. Dukakis.(84)

The media immediately asked questions about Bush's running mate, Indiana Senator John Danforth "Dan" Quayle. Some wondered if Quayle was a draft dodger, because he had served in the National Guard twenty years earlier, instead of going to Vietnam; others asked if he had the experience to be so close to the president. But because the momentum was with the Republicans, all Bush and his supporters had to do was portray Dukakis as just another Massachusetts liberal.(85) There was a famous photo of Dukakis riding in a tank, wearing a helmet, and most observers who knew Dukakis said it just made him look silly. Eventually Dukakis admitted that he was a liberal, but quickly pointed out that he was a liberal in the tradition of FDR, Truman and JFK. The most memorable quotes from the campaign came at the vice presidential debate, when Dan Quayle compared himself to former president Kennedy: "I have as much experience as Jack Kennedy did when he sought the presidency," In response his opponent, Texas Senator Lloyd Bentsen, said, "Senator, I served with Jack Kennedy. I knew Jack Kennedy. Jack Kennedy was a friend of mine. Senator, you're no Jack Kennedy." This encouraged liberals to make fun of Quayle for the next four years (see Chapter 3, footnote #14), but Bush won the presidential debates and stayed well ahead in the polls. The final score was that Bush won the popular vote 53-45, and carried forty out of fifty states.

George Herbert Walker Bush had one of the most impressive resumes you'll see anywhere. His father, Prescott Bush, was a Connecticut senator from 1952 to 1963. George was seventeen years old at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, and he postponed college to join the Navy, becoming the nation's youngest naval pilot and flying fifty-eight combat missions during World War II. After the war he went through an accelerated program at Yale University, graduating in two and a half years instead of four. Then for more than a decade, he founded and managed oil companies in west Texas, eventually becoming a millionaire before his interests turned to politics. He lost his first bid, running for a Texas Senate seat in 1964, but tried for a House seat in 1966 and won it, becoming the first Republican to represent Houston in Congress. He tried to become a senator again in 1970, only to be defeated by the previously mentioned Lloyd Bentsen. By that time, however, Bush had caught the eye of President Nixon; Nixon appointed him UN ambassador in 1971, and asked him to become chairman of the Republican Party in 1973. Gerald Ford found similar work for him, first as a special US envoy to China, then as CIA director. During the Carter years, he was chairman of the Executive Committee of the First International Bank in Houston, a part-time professor at Rice University, and director of the Council on Foreign Relations. Then there was his first run for the presidency in 1980, which landed him the vice presidential position under Reagan. Finally, Bush was the first vice president since Martin Van Buren to move into the top spot immediately after the president he had served under.

Despite all that experience, Bush did a rather poor job as president; the best thing you can say about him is that Michael Dukakis would have done worse, if elected. The main reason for his failing was that he wasn't a Reagan-type conservative, but a classic example of a "country club Republican," out of touch with ordinary Americans. Back in 1980 he had opposed Reagan's economic plan, calling it "voodoo economics." He faithfully toed the Republican Party line during his eight years as vice president, but once he became president, he showed he hadn't really changed his moderate position on the issues. At the beginning of his term, he promised a "kinder, gentler America," as if the Reagan years had left the country leaner and meaner.(86) Worse, he felt he needed to get along better with the Democrats than Reagan did, so instead of sticking to his convictions, he compromised on economic and civil rights issues. The efforts he made to be liked by the Democrats resulted in him not being liked very much by the Republicans.

During his term in office, Bush had several happy events handed to him on a silver platter, but he proved too inept to take advantage of them. In 1989 he presided over the fall of communism in eastern Europe, bringing the Cold War to a triumphant close. Also in 1989, he sent US troops into Panama to remove the local strongman, Manuel Noriega, after Noriega declared war on the United States, and brought him back to Miami to face charges of drug trafficking. One year later, Iraq occupied Kuwait, and the United States led the United Nations coalition that liberated the Kuwaitis. That campaign was both swift and brilliant; in the aftermath of the Gulf War, he had an approval rating of 91 percent in public opinion polls, the highest of any president in recent history. That, and the end of the Cold War, encouraged Bush to back the UN more strongly than Reagan had, and he talked openly of creating a "New World Order."

Elsewhere in the Middle East, negotiations between the Israelis and the Palestinians were finally showing some progress. Then on Christmas Day of 1991, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Uncle Sam never looked so strong; the United States was the world's last superpower, or as the French foreign minister called it, a "hyperpower." But Bush didn't use the occasion to discredit communism by explaining why it failed; instead folks talked about enjoying a "peace dividend," now that both parties agreed that it was safe to cut defense spending.(87) With the outside world less threatening, the attitude of many Americans was to forget about foreign policy--the area in which Bush was strongest.

However, the story wasn't so rosy on the domestic front. The economy had slipped into a recession in 1990, because of the collapse of the nation's savings & loan associations, a rise in oil prices during the Persian Gulf crisis, and the failure of several important foreign economies, especially those of Germany and Japan. This led to decreased revenues for the federal government, at a time when spending was increasing. At his acceptance speech in 1988, Bush made his most important promise; he told Republicans to "Read my lips, no new taxes!" But he did not keep it; to help balance the budget, he eventually agreed with congressional Democrats to introduce tax increases. This alienated the Republicans' conservative base, and caused enough conservative defections to make sure that in the 1992 presidential election, Bush would not get reelected.

Still, for 1992 Bush secured the GOP nomination easily enough. His only Republican opponents were Patrick J. Buchanan, a former CNN commentator and member of the White House Staff under Nixon and Reagan; and David Duke, a former Ku Klux Klansman and congressman from Louisiana. Both Buchanan and Duke were so far to the right that even some conservatives thought they were too much.

Among the Democrats, there were several viable candidates: New York Governor Mario Cuomo, Former Massachusetts Senator Paul Tsongas, Tennessee Senator Albert H. Gore Jr., Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton, Iowa Senator Tom Harkin, Nebraska Senator Bob Kerrey, Former California Governor Jerry Brown, and others. Cuomo and Gore chose not to run, and among the rest, there was no clear favorite at first, until Clinton won the "Super Tuesday" primaries in March. By portraying himself as a centrist, "New Democrat," Clinton convinced Democratic voters that he was the most electable choice they had (what a change, see footnote #84!). Then at the Democratic convention he practiced a typical party-uniting move and picked a rival, Tennessee Senator Al Gore, to be his running mate.

For most of spring, Clinton was running third place in the polls. A lot of voters were disgusted with a system where little changed, whether Democrats or Republicans controlled Washington; they were also concerned with runaway federal spending. A Texas billionaire, H. Ross Perot, capitalized on this by creating a third party, the Reform Party, ran as its first presidential candidate, and promoted a platform that was thoroughly populist. He read voter sentiments correctly, and soon he was running neck-and-neck with Bush in the polls; some saw him as the first independent/third party candidate with a chance of winning, since Theodore Roosevelt ran in 1912. However, Perot, like many successful businessmen, had a mercurial personality, and his behavior as a candidate was bizarre, to say the least. In July he dropped out of the race, without giving a clear reason why. Nevertheless, his supporters managed to get his name on the ballot in all fifty states, so in October he renewed his campaign. To explain his previous action, Perot claimed that he had heard the Bush campaign was going to publish altered photos from his daughter's wedding, that made his daughter look like a lesbian. Whatever his reason for quitting, the thrill was gone, and voters felt betrayed; he generated far less enthusiasm after returning. The most sensible explanation for Perot's actions was that he had a grudge against Bush, so any result that kept Bush from winning was a victory for him.(88)

With Perot eliminated as a serious contender, most of the media jumped behind Clinton, pumping up his campaign so big that it could have been floated as a balloon in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day parade! One week after the Democratic convention, Clinton was 24 points ahead of Bush in the polls, compared with 25 points behind in June. However, some serious character flaws emerged as well. During the primaries, a reporter named Gennifer Flowers claimed to have had a twelve-year affair with Clinton (he didn't admit to the affair until 1997, when he no longer had to worry about it hurting him in any elections). Allegations also surfaced that he had written letters and used the help of Senator William Fullbright to get himself excused from military service during the Vietnam War; that technically made him a draft dodger. Finally, he admitted to smoking marijuana during his college years, though he claimed he didn't inhale. None of this, though, was enough to disqualify Clinton in the minds of the voters.(89) Most voters let the economy decide for them (the best-known Democratic slogan was, "It's the economy, stupid"), and because it was a three-way race, Clinton managed to win with a plurality instead of a majority, getting just 43% of the popular vote (vs. 37.4% for Bush and 18.9% for Perot).

The new president's original name was William Jefferson Blythe III. Though his birthplace was an Arkansas town named Hope, his life must have looked hopeless at first. He was born out of wedlock, three months after his father, a traveling salesman, died in a traffic accident. When he was four years old, his mother married Roger Clinton, and they moved to the town of Hot Springs; later William took his stepfather's name, becoming William Jefferson Blythe Clinton--Bill Clinton for short. On at least one occasion Bill had to stop his stepfather, who was an alcoholic, from beating his mother. At the same time he was an overachiever at school, perhaps because it kept him away from trouble at home. In high school he ran in so many elections that he was nicknamed "Vote Clinton" and banned from future campaigning, like the radio listener who wins too many contests from a radio station.

A meeting with John F. Kennedy at the White House in 1963 persuaded Clinton to become just like him. After graduating from Georgetown University, he won a Rhodes Scholarship and went to Oxford in England. There he protested the Vietnam War, which makes him the only ex-hippie to become president (so far), and he even managed to visit Moscow as a tourist, something few Americans were allowed to do at the time.(90) Upon returning to the United States, he went to Yale (where he met his future wife, Hillary Rodham), and finished his schooling with a law degree from Yale. Then he went back to Arkansas to launch his political career; unless you count the short stints he had as a lawyer, he never held a private-sector job in his life.

Clinton's first run for public office was for the third congressional seat of Arkansas, which he lost (1974). Two years later, though, he won his next election to become the state's Attorney General, and then in 1978 he was elected governor. At this point he was only thirty-two years old, making him the youngest governor in the nation; some called him the "Boy Wonder." However, his first term wasn't a big success. Cuban refugees from the Mariel boatlift (see footnote #78) were detained at Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, and some of them escaped. That, and the introduction of an unpopular motor vehicle tax, raised such a big stink that Clinton was defeated by a Republican challenger in 1980. Afterwards, Clinton joked that he was now the youngest ex-governor in US history, and he spent the next two years working at a friend's law firm, while preparing his re-election campaign. His comeback succeeded, as you might expect from someone later called the "Comeback Kid," and he remained governor for the next decade (1982-1992), until he made his presidential bid.

Clinton showed some unusual priorities after becoming president. Whereas George Bush had been the "foreign policy president," Clinton showed little interest in foreign policy during his first year in office. When a president chooses who will be in his Cabinet, the position of Secretary of State is usually one of the first to be filled, but for Clinton it was one of the last. Nor did he act first to fix the economy, despite all his talk about it during the 1992 campaign. Instead, his first goal after taking office was a social issue: getting gays into the military. Previously, homosexuals were considered a security risk, and usually dishonorably discharged from the armed forces when discovered. Clinton's action on this issue got him criticism from the left, (which thought he wasn't doing enough to keep his campaign promise on gay rights), and from the right (which preferred to keep the current policy). He ended up settling for a compromise called the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy; service members would still not be allowed to reveal that they were gay, lesbian or bisexual, but they would not be investigated just because their superiors heard rumors of their sexual orientation.(91)

Though most liberals saw this as a setback, they got over it quickly, because they felt Clinton was one of them. Especially Hollywood; Clinton loved Hollywood, and Hollywood loved him. At least once he made sure a major speech would not be given on Oscar Night, Hollywood's biggest TV event of the year. On a visit to Los Angeles in 1993, he tied up traffic at LAX International Airport, shutting down two runways for more than an hour so that Christophe, a hair stylist for the movie stars, could give him a $200 haircut on Air Force One. The silliest part of the incident was how the White House Chief of Staff, George Stephanopoulos, defended it: "The president has to get his hair cut like everybody else."

Clinton called himself a centrist and a "New Democrat" because it had been thirty years since the Kennedy presidency, so the Democrats most voters remembered were failed liberals: e.g., Johnson, McGovern, Carter, Mondale and Dukakis.(92) However, as president his actions were anything but centrist. For example, his first appointment to the Supreme Court, Ruth Bader-Ginzburg, was one of the most liberal justices the Court has ever seen. In 1992 he promised a tax cut to the middle class, but even before taking office, he went back on that promise, stating that the government couldn't afford it during a recession. And despite the class warfare talk that the Democrats are known for, Clinton raised taxes on everybody; the per capita tax burden on Americans rose from $4,153 to $5,225, a 25.8 percent increase, during his first term. To give two examples of that, a four-cent-per-gallon gasoline tax affected all who could drive, and his Social Security tax increase hit 5.5 million retirees. Some of the taxes were retroactive, meaning they covered activities/events that happened before 1993.

Raising taxes and choosing people with left-of-center political opinions are two signs of liberal behavior. Two other signs are increasing spending, especially on social services ("I feel your pain"), and expanding government activity. Clinton did both of these as well, though he did not pursue them as aggressively as FDR and LBJ had. To encourage civic education and public service, he launched Americorps, a program that worked like the Peace Corps, but stayed within the borders of the United States. Americorps activities ranged from public education, to funding various clubs for boys and girls, to cleaning up polluted areas. This is certainly useful, but Americorps was also a redundant organization, because it absorbed VISTA, an older, smaller government program that did the same thing. Moreover, it claimed that its members were "volunteers," when they were typically paid wages of $7 to $9 per hour. On the other hand, another initiative of the Clinton years was so dumb that only intellectuals believed it would work--the introduction of "Midnight Basketball" to curb inner-city crime and drug use among young people.

There was also Clinton's approach to affirmative action, the government hiring policy that discriminates in favor of "under represented groups or individuals with disabilities," meaning that a healthy white male would not be hired if somebody else who was equally qualified applied for the job. Because there had been some abuses in the policy since it was first introduced in the 1960s, Clinton said, "Mend it, but don't end it." In practice, though, he didn't mend affirmative action, but let it continue to run unchecked, even when it violated common sense. For example, the Food and Drug Administration's "Equal Employment Opportunity Handbook" stated that for filling that agency's jobs, skills like "knowledge of rules of grammar" and "ability to spell accurately" would be de-emphasized if they made it difficult to hire a sufficiently diverse group of people. Strangest of all was the response of the US Forest Service, when told it needed to hire more female firefighters. The first job announcement after that said, "Only unqualified applicants may apply," and it was later corrected to read, "Only applicants who do not meet [job requirement] standards will be considered." Despite this, some critical firefighting positions were not filled because they did not get enough applicants, qualified or unqualified.

One member of the White House staff was unelected and responsible to no one: Hillary Clinton. Because she was the dominant partner in the Clinton marriage, some observers suggested she was the real president, not her husband. Her special project was to create a government-run health care system, something liberals had been dreaming of for most of the twentieth century. Because 1/7 of the nation's economy was tied into doctors, nurses, hospitals, pharmacies, etc., and this was expected to grow as the population's median age rose (see "The Grey Generation" later in this work), nationalizing health care would be no trivial task. When Hillary and her staff got done, their health care reform plan ("Hillarycare") required 1,342 pages to be explained; if enacted, it would create 33 agencies and 200 regional alliances, add $70 billion to the federal budget deficit--and take away the patient's right to choose his doctor. The $70 billion cost was far less that what Barack Obama's health care plan would cost, fifteen years later, but in 1994, this was too much, even for a Democrat-controlled Congress, which voted against it without hesitation. Afterwards, Hillary blamed the failure on a "vast right-wing conspiracy," but otherwise she kept a lower profile for the next five years.

Meanwhile in the Republican camp, Richard Nixon died, and Ronald Reagan was diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease (both in 1994). The former actor responded by writing a letter to the American people, announcing that it was time to ride off into the sunset:

"I have recently been told that I am one of the millions of Americans who will be afflicted with Alzheimer's Disease. . . . At the moment I feel just fine. I intend to live the remainder of the years God gives me on this earth doing the things I have always done. . . . I now begin the journey that will lead me into the sunset of my life. I know that for America there will always be a bright dawn ahead. Thank you, my friends. May God always bless you."

True to character, some liberals cruelly suggested that Reagan had been suffering from the disease much earlier, when he was president. Although he lived ten more years, eventually reaching the age of 93, he never again appeared in public after writing that letter.(93)

Throughout both the Bush years and the early part of the Clinton years, American voters had grown increasingly angry with Congress; that was part of the reason why Ross Perot had been so popular in 1992. The problem was that senators and representatives had given themselves entrenched positions. The nation's Founding Fathers envisioned that members of the federal government would act like Cincinnatus, the famous Roman who ruled the Roman Republic reluctantly when called, and then went back to private life when he was no longer needed. Instead, by the late twentieth century, Congress was full of career politicians, who like Clinton, had never worked in the private sector. Once they got elected to Capitol Hill, the typical congressman could stay as long as he liked; many seats were uncontested from one election to the next, turnover was less frequent than it had been in the old Soviet Politburo, and a congressman was only likely to get voted out of office if he became a national embarrassment. In addition, Congress usually had a majority of its members coming from one party--the Democrats. Except for a six-year period in the early 1980s when the Republicans had the Senate, the Democrats controlled both houses of Congress straight from 1954 to 1994.

Under those conditions, a "culture of corruption" set in. The early 1990s saw reports of congressmen abusing the bank and the post office they set up for themselves in the Capitol; e.g., writing bad checks and expecting taxpayers to cover the cost. The House Minority Leader, Newt Gingrich (R-GA), took advantage of voter discontent by introducing the "Contract With America," a ten-point program that the Republicans promised to bring to the floor of Congress, if elected. This resulted in one of the biggest upsets in the history of congressional elections; the 1994 election saw the Republicans gain fifty-four House and eight Senate seats, giving them control of both houses. Most dramatic were the results in the House of Representatives: thirty-four members, all Democrats, were rejected by the voters, including the speaker, Tom Foley.

Newt Gingrich kept his promise and had the "Contract With America" voted on during the first 100 days of the next Congress. Only three of the provisions became law; two more were passed but vetoed by President Clinton. However, the Republicans now got to control Congress for most of the next twelve years (1994-2006). They also gave Clinton some headaches, as you might expect. For a start, they forced him to sign a welfare reform bill, after he had vetoed the first two reform bills that landed on his desk. Also, Clinton's previous budgets had predicted deficits exceeding $200 billion a year, going on well after his presidency ended, but now he was forced to make deals with the Republican Congress that eventually balanced the budget. In fact, he had a budget surplus for his last two years in office, the only time that has happened since the 1960s.(94) But that was all Congress could accomplish as long as Gingrich was speaker. While the Republicans concentrated their attention on Clinton's multiple character flaws, they let his policies slip by, giving the impression that what Clinton did was not as objectionable as how he behaved.(95) Nowadays the Republican-controlled Congress looks like a missed opportunity, because it did not make a case for limited government under Clinton, and under George W. Bush it would spend money even more irresponsibly than the Democrats had done.

For someone who wrote "I loathe the military" in a letter during his college days, Bill Clinton had to use the military astonishingly often. Because the defense budget had been cut (the post-Cold War "peace dividend"), the armed forces were stretched to the limit during the Clinton years. Clinton sent them on overseas missions no less than forty-four times during his eight years as president. By contrast, the presidents before Clinton did the opposite, dispatching the military only eight times in the previous forty-five years. Moreover, because the servicemen did not receive pay increases at this time, many of them were forced to ask for food stamps to help make ends meet, thus creating a new social class--the military poor. And except for the air raids in the former Yugoslavia and the 1998 retaliatory strikes on Iraq, Sudan and Afghanistan, the armed forces did not perform its traditional function of killing people and breaking things; more often it was doing tasks expected of the UN, either keeping armed factions separated or feeding the hungry in a glorified "meals on wheels" program. As former Air Force lieutenant colonel Buzz Patterson wrote in his book Reckless Disregard, "The [role of the] American soldier changed from homeland defender to nomadic peacekeeper."(96)

Clinton inherited two of his foreign entanglements (Somalia and Iraq) from Bush, but he didn't handle them as well as Bush did. In December 1992, Bush committed American soldiers to a UN relief mission for Somalia, which was currently suffering from anarchy and starvation. He may not have planned to do any more than feed starving Somalis, inasmuch as his term in office ended one month later, but Clinton decided that some nation-building would be needed for the mission to succeed. The result was that American soldiers swept through Mogadishu, trying to catch the toughest Somali warlord, and the Somalis ambushed them in the notorious "Black Hawk Down" incident, killing eighteen US Marines and destroying two helicopters; in the end it took four Pakistani tanks and twenty-four Malaysian armored personnel carriers to rescue the rest of the troops. Rather than endure another Vietnam-type "quagmire," the US force withdrew shortly after that. As for Iraq, it was an unresolved stalemate, where Saddam Hussein's dictatorship was wounded but still dangerous; all Clinton did there was enforce no-fly zones over two-thirds of Iraq, keeping a lid on the situation until he could bequeath it to his successor.

It was in the Balkans where Clinton's foreign policy caused the most trouble. For just over seventy years Yugoslavia, a multiethnic state, had managed to keep itself from breaking up, first when it was a Serbian-dominated monarchy, then as a Communist confederacy under Josip Broz Tito. Tito's successors couldn't play the balancing game as well, though, and in the late eighties, two events--the rise of a Serb hardliner, Slobodan Milosevich, and the fall of communism in all neighboring countries--convinced Yugoslavia's non-Serbs that it was time to quit the federation. One by one the Slovenes, Croats, Bosnian Moslems, and Macedonians declared independence from Belgrade, and because there were Serbs living in Croatia and Bosnia, Milosevich launched a new round of Balkan wars to keep as much of those states as possible.(97)

The United States had no economic or military interests in the Balkans; it was pictures and reports of Serb atrocities (remember the previous footnote about "CNN diplomacy") that persuaded Clinton to intervene on the side of Milosevich's opponents. Alas, there were no "good guys" in this situation. Milosevich needed to go because he was leader of the last Communist government in Europe, but the biographies of the other leaders showed they weren't much of an improvement. Bosnia's Alia Izetbegovic had been a member of the Handschar, the Moslem division of the SS, during World War II, and while Croatia's Franjo Tudjman was a pro-Allied partisan in that war, the government he set up in Zagreb looked a lot like the Fascist regime he once fought. When the Serbs attacked and captured Bosnian cities that had been declared "safe zones" by the UN, Clinton gave the go-ahead for US planes to join NATO in a series of surgical air strikes that broke the Serbian advance (August 1995). Then in the spring of 1999, NATO responded to reports of Serb atrocities in Kosovo with a bombing campaign that continued until the Serbs gave up. In both cases ground troops were not committed until the fighting was over, so for Americans the Yugoslav Wars were bloodless. One American pilot, Scott O'Grady, was shot down by Bosnian Serbs, but he managed to hide for six days until rescued by US Marines.(98) The ground troops just served as a peacekeeping force, this time well into the first decade of the twenty-first century.

The evidence for Serb atrocities in Croatia and Bosnia was plain to see (Serbian artillery had fired on the safe zones, and "ethnic cleansing" had taken place on Serb-captured land), but after the war ended, similar evidence could not be found in Kosovo. While estimates of the number of Albanians massacred by the Serbs ranged from 100,000 to 400,000, no mass graves were discovered like those the Serbs dug elsewhere, so it now appears that casualties during the Kosovo phase of the war may have been as low as 2,500. Even worse, during the course of the war, veteran Mujahideen came from the Middle East and Afghanistan to fight alongside Bosnian Moslems and Kosovar Albanians. At the time this did not generate much concern, because most Americans had not yet realized that militant Islam had replaced communism as the chief enemy of the United States. But this meant that after the war, Bosnia and Kosovo joined Albania and Turkey as bases for Islamic activity in Europe.(99) Because the Serbs had been on the same side as the Americans in both World Wars, it now looks like the United States did the Serbs dirty.

This is the end of Part IV. Click here to go to Part V.

FOOTNOTES

70. The televised presidential debates, which made such a difference in the 1960 election, were not repeated in 1964, 1968 or 1972. Carter revived them for 1976, and they have been held every four years since then, usually in a format of three debates between the presidential candidates, and one between the vice presidential candidates. They seldom have much effect in changing the minds of the voters, though.

71. "Jimmy Carter as president is like Truman Capote marrying Dolly Parton. The job is too big for him."--Rich Little

72. Carter created a new Cabinet seat, the Department of Energy, and broke up the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, to form the Department of Education and the Department of Health and Human Services.

73. On the other hand, normalization of relations with China put the former US ally, Taiwan, in a state of limbo. Few nations wanted to deal openly with the island where Chiang Kai-shek's successors ruled, out of fear that this might antagonize Mainland China, but Taiwan was also too rich to ignore.

74. For some reason, every president from Nixon onward felt it was his duty to bring peace to the Middle East. But this is the world's most war-ravaged region, and any Bible scholar can tell you the roots of the conflict go back nearly four thousand years, to the rivalry between the sons of Abraham. This means the problem isn't likely to be solved in one four-year term, or even two, but they try nonetheless. In Carter's case, the Camp David treaty was followed by talks to normalize relations between Israel and Jordan, and between the Israelis and Palestinian Arabs. No visible progress would be made, though, for another decade.

75. The first Space Shuttle mission was launched on April 12, 1981. Coming less than three months after Carter's term ended, the flight was a relief for quite a few Americans, because it had been six years since the last manned space flight, and this one showed that the federal government could still do something right.