| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Africa

Chapter 9: THE INDEPENDENCE ERA, PART II

1965 to 2005

This chapter is divided into three parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| Independence: Tying Up the Loose Ends | |

| Civil War in the Ex-Portuguese Empire | |

| Who Owns the Western Sahara? | |

| One-Man Rule: | |

| North Africa Takes a Military Road | |

Part II

| Nigeria: The Great Underachiever | |

| The Horn of Africa: Horn of Famine | |

| Southern Africa: The Fall of Apartheid | |

| Rwanda, Burundi, and the Congo: Still the Dark Heart of Africa | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part III

| The Island at the End of the World | |

| America's Stepchild and Her Anarchic Neighbors | |

| The Islamist Menace | |

| Starting Over Again With the African Union | |

| Modern African Demographics | |

| The Challenges Facing Modern Africa |

Nigeria: The Great Underachiever

Nigeria was Africa's most promising new nation in the early 1960s. It had Africa's largest population (43 million people at independence), a rich heritage from several ancient cultures, and the largest oil reserves south of the Sahara (discovered in 1958).(18) Finally, the transition to independence went more smoothly than that of other large African states, especially the Congo. Still, when it came to living up to expectations, Nigeria failed dismally.

The Moslem north had more people than the Christian south, so it was supposed to dominate the government, but the mostly Catholic Igbo were the best educated tribe, so even before independence they held the largest share of government/administrative jobs, and did not want to give up this advantage. In January 1966, a group of Igbo officers revolted, assassinated Prime Minister Balewa and the political leaders of the Northern and Western Regions, and put their commander, Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi, in charge of the country. Ironsi immediately imposed martial law, but that did not keep northerners from massacring hundreds of Igbos, and driving thousands more out of non-Igbo areas (among the refugees was President Azikiwe, who now became an advisor for the Igbo-led government of the Eastern Region). In July some northern officers staged a counter coup in Lagos, killing Ironsi and replacing him with Lieutenant Colonel Yakubu Gowon. Gowon tried to defuse the crisis by overhauling the federal government, but because his plan included dividing the Eastern Region into three smaller states, the local military governor, Lieutenant Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, declared independence for the east as the Republic of Biafra, on May 30, 1967.

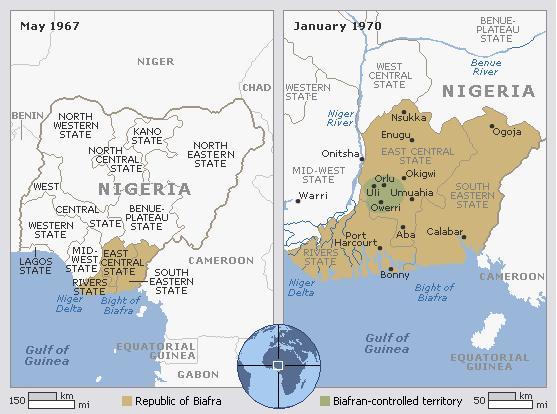

Biafra, at the beginning and end of the war.

A Biafran soldier.

Nigerian forces made the first move, capturing the university town of Nsukka in July 1967. Gowon promised that a "short, surgical strike" would end the rebellion quickly, but the war that followed was nothing like that; it lasted two and a half years, and next to the wars in Sudan and the Congo, it was the bloodiest in Africa's recent history. For a start, both sides had outside support: the United States, Soviet Union, United Kingdom and OAU supported Nigeria's central government, while Tanzania, the Ivory Coast, Portugal, South Africa, and the Roman Catholic Church backed Biafra. In addition, most of Nigeria's oilfields were on the southeast coast, meaning that the Biafrans had more money. A Biafran counteroffensive in August conquered the Mid-Western Region, and was within 80 miles of Lagos when government forces turned it back. After that, it was purely a war of attrition. In October, the Nigerians captured Enugu, the Biafran capital; in May 1968 they completed the conquest of the oil-rich coast. Biafra was now cut off by land and sea, but it could still receive foreign aid by air, so it continued to resist until it was ground out of existence; frightful images of starving Biafran children became a common sight in foreign news stories.

The end came on January 12, 1970, when Biafra surrendered, two days after Ojukwu had gone into exile in the Ivory Coast. Between one and two million Nigerians and Biafrans had died, mostly from starvation, so it was a bit of a surprise that threatened reprisals and massacres did not happen. Instead, Gowon simply carried out the restructuring plan he had announced before the war, dividing Nigeria's four states into twelve smaller ones, to make it more difficult for future rebellions to succeed. He also made a real effort to reintegrate the Igbo back into Nigerian society. Long after Gowon's presidency ended, the last step in that process occurred on May 29, 2000, when President Olusegun Obasanjo commuted to retirement the dismissal of all soldiers who fought on Biafra's side during the Nigerian civil war.

Yakubu Gowon may have won the war, but he couldn't win the peace that followed. Though the economy grew rapidly in the early 1970s, most of the new wealth remained in the hands of a few people. In addition there were high prices, shortages of key commodities, and corruption; the ports were so inefficient that tankers had to wait offshore for months to load a cargo of oil. At the end of the war, Gowon had promised a return to civilian rule by 1976, but in 1974 he changed his mind and announced that because Nigeria was in such a mess, he would have to stay on indefinitely. This was unacceptable even to his fellow officers, and in July 1975 Gowon was thrown out in a coup led by one of them, Brigadier General Murtala Muhammed. In the areas where Gowon had not acted, Muhammed moved quickly; he replaced corrupt and incompetent state governors and civil servants, and announced a timetable to restore civilian rule by October 1, 1979. For the more distant future, he announced he would create still more states and build a new capital, Abuja, in the center of the country, to replace Lagos.

Muhammed was very popular because of these reforms, but he didn't get to rule for long; he was assassinated in February 1976, during an unsuccessful coup attempt. His government remained in power, though, and his chief of staff, Lieutenant General Olusegun Obasanjo, took charge and continued right where Muhammed left off. This meant modernizing and making the armed forces more efficient, and investing oil revenues back into the economy, instead of just spending them. Obasanjo also created seven new states in 1976, and his successors continued that process, until by 1996 Nigeria had 36 states. A year later he convened a constitutional convention that recommended replacing the British-style parliamentary system with an American-style presidential system, with separate executive and legislative branches. To prevent the election of candidates that only appealed to one tribe, it was required that the president and vice president win at least 25 percent of the vote, in at least two-thirds of the 19 states. The new constitution took effect in 1979, beginning Nigeria's Second Republic.

Unfortunately, the Second Republic was even shorter-lived than the first. When elections were held for it in 1979, only the National Party of Nigeria (NPN) received votes from several parts of the country. Its candidate, Alhaji Shehu Shagari, won the required 25 percent of the vote in 12 states, and that provoked a constitutional crisis: two-thirds of nineteen is not a whole number, but 12 2/3, so did Shagari need to carry twelve or thirteen states to win the election? The federal election commission ruled that twelve states were enough, leaving suspicions that the election was not entirely fair. After the new administration was in office, it launched several programs to strengthen the economy, but they were too expensive and impractical to achieve much, and attracted more corruption. Then in 1982 the price of oil collapsed, leaving the government unable to pay its bills or import essential goods. The response was to expel more than a million unskilled foreigners, most of them from Ghana; the government claimed that they committed crimes and took jobs away from Nigerians. Things didn't get better after the NPN won the elections of 1983, so on the last day of the year the military came back, replacing Shagari with Major General Muhammadu Buhari in a bloodless coup.

Buhari was popular at first, but this faded quickly as he imposed severe economic and political restrictions on the country. This got to the point that when he was overthrown in August 1985 by another general, Ibrahim Babangida, most were glad to see him go. Babangida voided several of Buhari's decrees, encouraged public debate on the economy, and loosened government controls. The economy began to recover when he declared a fifteen-month "economic emergency," allowing him to cut the pay of the military, police, government workers, and several private-sector workers. Imports of rice, corn and wheat were banned, removing another big expense. Negotiations were conducted with the International Monetary Fund, but Babangida decided not to accept an IMF loan because the round of austerity measures the IMF demanded in return were very unpopular. In 1991 he began moving the government to Abuja, since the new capital was now nearly complete.

While Babangida was overseeing economic recovery, he did not allow political parties, and kept shuffling key officers around to make sure they didn't stay in one place long enough to gain much support. There also were concerns that he was biased, favoring northern interests too much. He managed to survive coup attempts in 1986 and 1990, and other tensions within the country increased, especially between Christians and Moslems. Consequently Babangida decided he couldn't stick around indefinitely, and in 1989 he announced a new constitution that was basically the 1979 one with some minor changes. Then he made political activity legal again, but only allowed two parties: the National Republican Convention (NRC), which was described as "a little to the right," and the Social Democratic (SDP), which was "a little to the left." Local and legislative elections were held on schedule, but the presidential election was delayed until June 1993, because fraud was such a problem that no results could be trusted. When the election finally took place, the winner was the SDP candidate, a wealthy Yoruba publisher named Moshood Abiola. However, Babangida refused to let Abiola take office, citing several pending lawsuits as reason enough to annul the election. Riots broke out across the country, killing more than a hundred, compelling Babangida to hand over power to an interim government led by Ernest Shonekan, a nonpartisan businessman. Shonekan didn't even get a chance to do better than his predecessors; he was forced to resign in November 1993 by the defense minister, Sani Abacha. Abacha outlawed political activity yet another time, and replaced all civilian government officials at the national and state levels with military men, turning the country into a police state.

Nigeria had already seen more than its share of bad leaders, but Abacha managed to be the most unlikeable of all. He rarely traveled abroad, because no foreign government wanted anything to do with him. Neither left-wing nor right-wing, his only ideology was personal gain; in the first year after his reign ended, $770 million in missing state funds was recovered from former underlings, friends and relatives; it is believed that he embezzled nearly $3 billion altogether. When Abacha wasn't busy making himself richer, he was sharing the loot with cronies--most of them from the Fulani and Hausa tribes--and jailing and executing dissidents. Among those locked up were former general and president Obasanjo, former vice president Shehu Musa Yar'Adua (who died in prison in December 1997), and the 1993 president-elect, Moshood Abiola. Because the 1993 election was Nigeria's fairest yet, annulling it caused the outside world to impose sanctions on Nigeria, and from 1993 to 1999 the United States refused to allow Nigerian planes to land at American airports.(19)

Abacha's most notorious act of repression involved the Ogoni, a small tribe that lived right on the oilfields. Foreign oil companies had pumped out billions of dollars worth of petroleum, polluting Ogoni land in the process, but the Ogoni were no richer than before. In late 1994 Abacha set up a special tribunal to try Ken Saro-Wiwa, a well-known Ogoni author and environmental activist, and fourteen other Ogoni, on charges that they had been involved in the murder of four Ogoni politicians earlier in the year. They were convicted, and although there were international calls for their release, nine of the defendants, including Saro-Wiwa, were hanged in November 1995. Because of this act and others like it, Great Britain suspended Nigeria's membership in the Commonwealth of Nations, a rare punishment indeed.

Abacha finally got around to announcing a return to civilian rule in his October 1, 1995 Independence Day speech; there he promised to do it by 1998. He lifted the ban on political activity, but among the new parties formed, only five were given permission to run in elections. For the October 1998 presidential election, Abacha was expected to win easily, because all five legal parties had nominated him as their candidate. Instead, he died suddenly of a heart attack in June. His successor, Major General Abdulsalam Abubakar, pledged to carry out the elections as soon as possible. Moshood Abiola probably would have won this election, just as he had apparently won the election of 1993, but before he was released from prison, he also died of a heart attack; suspiciously, the heart attack happened during an interview with the United States ambassador (July 1998).

Unlike the previous dictators, Abubakar didn't play games concerning when he might step down. He released the political prisoners of Abacha that were still alive, curbed the worst of the human rights abuses, and made sure the elections on the local, state and national level took place only a few months later than originally planned (December 1998-February 1999). In the last round of voting, nine parties ran candidates for president, and former president Olusegun Obasanjo, now a civilian, was elected to serve again. By May of 1999, the transition to civilian rule was complete. There probably wasn't anything else Abubakar could have done, because the military had ruled Nigeria for 29 of the past 33 years, and wrecked the country in the process. Nigeria should have been blessed by its immense oil reserves, but somehow the oil money simply disappeared (General Babangida reportedly "lost" $12 billion of it while he was in charge, and never could explain where it went). Nigeria's international reputation was in the dumps as well. You could say that the dictators, from Gowon to Abacha, had sucked the country dry, and the only job left for Abubakar was to throw away the skeleton.

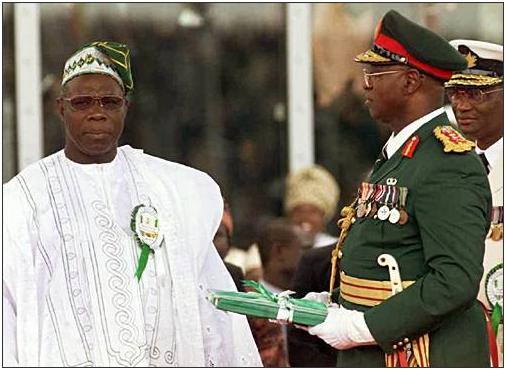

The end of military rule in Nigeria. Here, on May 29, 1999, military president Abdulsalam Abubakar (right), handed over the flag and constitution of Nigeria to democratically elected president Olusegun Obasanjo.

Obasanjo's second presidency began with plenty of good will for him; though a Christian from the Yoruba tribe, he was widely admired by both Christian and Moslem Nigerians because he had returned the government to civilian rule twenty years earlier, and more recently he had been an opponent of the Abacha dictatorship. The British Commonwealth lifted its suspension of Nigeria's membership, and other nations removed the sanctions they had imposed. Still, he faced many problems, such as a collapsed economy, dysfunctional bureaucracy, and military officers who wanted a reward for going away quietly. He moved quickly to retire the officers who held political positions, established a blue-ribbon panel to investigate human rights violations, and restored freedom of the press. For the first time it also looks like Nigeria's federalism is going to work, because the states and their governors are more visible, and the state capitals frequently argue with Abuja over resource allocation.

Many of Nigeria's problems stem from chronic poverty; when one can't make enough money to live through legal means, many will turn to crime. For that reason, Nigeria has one of the highest crime rates in the world, with 94 murders and 1,256 thefts for every 100,000 people per year (1999 figures). For tourists, Lagos can actually be more dangerous than notorious havens of violence like Beirut or Baghdad. And even if you never go to Nigeria, you can still be at risk; Nigerian-based organized crime syndicates are currently active in sixty countries, and they are always looking for new victims to swindle through letters and e-mails offering get-rich-quick schemes (the so-called 419 scam, more about it on my Netiquette page).

Another big problem for Nigeria is ethnic turmoil; mistreatment of women is still commonplace (this includes the practice of female genital mutilation), and intertribal rivalries and violence between Christians and Moslems kill more than a thousand every year. Much of the religious strife is caused by Islamic fundamentalism, which has encouraged several northern Nigerian states to impose Shari'a (Islamic law) on both Moslem and non-Moslem subjects. Sometimes this has led to Islamic courts sentencing women to death by stoning, for having children out of wedlock, a judgment called barbaric by the rest of the world. One of the worst episodes of violence occurred in 2002, just before the Miss World beauty pageant was scheduled to be held in Abuja. Abuja seemed like a good location at the time, because a Nigerian contestant had won the pageant in 2001. Instead, chaos broke out when a local newspaper suggested that if the Prophet Mohammed had been there to watch the pageant, he probably would have chosen to marry one of the contestants, though they are older than the women he preferred (a reference to his youngest wife, Aisha, see Chapter 9 of my Near Eastern history). The government of the state of Zamfara immediately pronounced a death sentence on the reporter who made that remark; angry rioters protesting the pageant left more than 200 people dead; the pageant itself was hastily moved to London.

Obasanjo was reelected to another term in 2003. Other candidates who ran included former military leader Muhammadu Buhari, and Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu, the former Biafran leader. They accused Obasanjo of electoral fraud when they lost, but Obasanjo's margin of victory was so huge that stuffing the ballot box for any candidate would not have made much of a difference. At any rate, it was the first time that a civilian government in Nigeria had successfully conducted an election. Obasanjo's previous four years had been largely ineffective, but after the 2003 election he began to get results from the economy; the deregulation of fuel prices, and the privatization of the country's four oil refineries, caused the GDP to rise strongly in 2004. In 2005 he also served as chairman of the African Union. Still this amount of progress is a drop in the bucket for a country with more than 100 million people, sixty percent of which live below the poverty line, and the increasing polarization of the country's Christian and Moslem communities could someday lead to another civil war. Therefore it looks like Obasanjo will need all the time he can get, if he's going to leave Nigeria any better off than it has been for the past forty years.(20)

President Obasanjo enjoys a lighthearted moment with US President Bush (in Paris, 2003).

The Horn of Africa: Horn of Famine

Ethiopia & Eritrea

In Chapter 8, we saw Haile Selassie as a war hero, and a founder of the OAU. For one group of foreigners, he even became a messiah. These were the Jamaican followers of Marcus Garvey, the black nationalist leader. Before he left for the United States in 1916, Garvey told them, "Look to Africa where a Black King shall be crowned; he shall be your redeemer." They viewed the coronation of Haile Selassie as a fulfillment of this prophecy, and called themselves Rastafarians, using Selassie's pre-coronation name. When Haile Selassie visited Jamaica in 1966, a hundred thousand Rastafarians mobbed the airport, smoking marijuana and playing drums, to greet the emperor. He had no idea what was going on, and refused to leave his plane for an hour, until persuaded that this crowd was friendly. Still, he was disturbed enough to tell the Ethiopian archbishop about the affair after he got home, and the archbishop sent a team of missionaries to Jamaica, in the hope of converting Rastafarians back to Christianity.

Rita Marley became a Rastafarian after seeing Haile Selassie, and her enthusiasm drew her husband, the famous reggae singer Bob Marley, into the faith that he later publicized. Today's Rastafarians still believe that the Second Coming of Jesus was fulfilled by Haile Selassie, though he remained a Coptic Christian all his life, and died decades ago under humiliating circumstances.

Despite his success on the world scene, Haile Selassie's monarchy looked out of date by the 1960s. While the rest of Africa changed rapidly, Ethiopia stood still, and as the emperor grew older, he lost touch with his people. Much of the time he traveled abroad, maintaining Ethiopia's good image with the rest of the world, but at home his people were dirt poor, and only 7 percent of them could read.

Another ongoing problem was Ethiopia's non-Amhara subjects, especially the Eritreans in the north, the Somalis in the east, and the Oromo in the south. In Chapter 8 we noted that most government jobs, and ownership over much of the land, were reserved for Christian members of the Amhara clans, even in predominantly Moslem areas like Eritrea and the Ogaden. The Eritreans revolted in 1961 because they were supposed to be autonomous, but Ethiopia wouldn't let them have a say in how they should be governed. At first, there was only one group fighting for Eritrea's independence, the Cairo-based Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF). It failed to make much headway against the Ethiopian government, and a massive Ethiopian invasion in 1967 drove 7,000 Eritreans across the border into Sudan, thereby raising tensions between Addis Ababa and Khartoum. In 1970 one faction of the ELF broke away and founded another rebel force, the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF); it soon became more important, fielding ten thousand guerrilla fighters. In the early 1970s Ethiopia still had the advantage, because the ELF and EPLF were more interested in fighting each other, but even after the government put all of Eritrea under martial law (December 1970) it could not stamp out the rebellion. In 1964 Ethiopia and Somalia briefly clashed over the Ogaden; they agreed to a truce along the border, but new hostilities would break out from time to time. As for the Oromo, their grievance was that they were the largest tribe in Ethiopia, but the dominant Amhara would not share power with them.

The drought of the Sahel also began to afflict Ethiopia in 1972, leading to an economic crisis. Haile Selassie did nothing to relieve the resulting famine, and may not have even known about it; the government kept him busy with festivities surrounding his 80th birthday. It became clear that the government was failing, because the emperor was failing, too. He had so much control over the government--and Ethiopian society--that little got done when he was abroad: "Most Ethiopians thought in terms of personalities, not ideology, and out of long habit still looked to Haile Selassie as the initiator of change, the source of status and privilege, and the arbiter of demands for resources and attention among competing groups."(21) It was time for a change, and because many members of the Oromo tribe had joined the military when other avenues of advancement had been denied to them, Oromo officers would lead the way here. In January 1974, the army garrison at Nagalle, a desert town near the southern border, mutinied because of appalling living conditions, and again the government failed to make an effective response. A group of officers in Addis Ababa decided to take matters into their own hands, forming the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Services (Derg in Amharic, also spelled Dergue). In September 1974 they deposed Haile Selassie, placed him under house arrest, set up a provisional military administrative council to rule in his place, and abolished the monarchy which had lasted for more than a thousand years.

Haile Selassie, at the end of his reign.

The world did not give much attention to the fall of Ethiopia's last emperor: it seemed like just another Third World coup, and because its nearest neighbor, Somalia, was both hostile and a Soviet satellite, Ethiopia was expected to remain pro-Western. However, the Derg had other plans. The new rulers had Marxist leanings, and though the Derg was not a communist party per se, that did not keep them from launching a communist-style revolution. First they announced that the Provisional Council would be a permanent government, and a bloody purge followed, in which 59 members of the royal family, and ministers and generals of the imperial regime, were executed. Meanwhile, all banks were nationalized, and then industry, rural land, and finally urban land and housing. In August 1975 the Derg announced that Haile Selassie had died during a prostate operation; rumors persist, however, that he was smothered with a pillow.(22)

The revolutionaries soon lost control of what they had started. 60,000 young radical students were sent into the countryside to motivate and radicalize the peasants, a move very similar to what China did with the Red Guard in the 1960s. Ambassadors from communist countries, especially China, Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, warned that reckless behavior was endangering what had started as a promising situation. Peasant uprisings broke out, and an anti-Derg movement appeared, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Party (EPRP). The EPRP began a guerrilla war known as the "White Terror," and the Derg responded with a "Red Terror"; an estimated 100,000 people were killed or disappeared in 1977 and 1978, as a result of this conflict. 1977 also saw the revolution turn against itself, the way so many others have; several high-ranking members were purged, including the Derg's chairman, General Teferi Benti, and Lt. Col. Mengistu Haile Mariam, who may have been the real mastermind behind the revolution, became the new number one.

By now the revolution was in serious trouble, and not just because of the EPRP. Much of Eritrea had come under rebel control by 1977. In the northwest, the Tigrean People's Liberation Front (TGLF) launched a rebellion in 1976, to establish a separate state in the region of Gondar, Ethiopia's ancient capital; it was soon joined by a monarchist party, the Ethiopian Democratic Union (EDU). Somalia invaded the Ogaden in July 1977, to help the Somali separatists, and quickly conquered the whole region except for the towns of Harar and Dire Dawa. And to top all this off there was no more military aid coming in, because the Western powers, especially the United States, had broken off diplomatic relations by now.

Mengistu's last hope was the USSR, and after he made a trip to Moscow in February 1977 he got the assistance he needed--on the Soviet Union's terms. With the Soviet arms came Cuban advisors and soldiers, since they had been so useful in Angola, and they managed to halt the Somali advance. The Soviets couldn't burn both ends of the East African candle, and they probably expected it when Somalia expelled its Russian and Cuban advisors in November, and ordered the closing of the Soviet naval base at Berbera. Then Somalia normalized relations with the United States, but this was the time of the Carter presidency, which didn't want any part in the brush wars of the Third World, so no Western aid came to offset the loss of Soviet aid. In early 1978 Mengistu took back the Ogaden; by the end of the year he had also crushed the EPRP, and the EDU broke up when it was on the verge of capturing Gondar. Then he turned against the All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement (MEISON), a Marxist group that had supported him to this point, fearing that its members were more loyal to their party than to the Derg. After that the USSR built up Mengistu's armed forces until he had the second largest army in sub-Saharan Africa, and a significant navy and air force as well.(23)

As Mengistu gained the upper hand against his opponents, he declared communism the official ideology of the state, and in 1984 he created a Marxist-Leninist party, the Worker's Party of Ethiopia (WPE), to serve as the country's legal political party. In 1987 he completed a Soviet-style constitution, and it abolished the Derg, though several Derg members remained in the elected national assembly that took its place; this assembly elected Mengistu as Ethiopia's first president.

Now that Ethiopia was a confirmed communist state, in the mold of the Soviet Union, everything quickly went downhill. Mengistu had never defeated the Eritrean or Tigrean rebels (eight Derg-sponsored offensives in Eritrea between 1978 and 1986 had all failed), and the previously mentioned droughts continued to hamper agricultural production. The famine was really bad between 1984 and 1986, when an estimated one million Ethiopians starved to death. Because the famine hit the war-ravaged northern regions the hardest, the government relocated 600,000 northerners to the south, but this didn't help much, and the government's distrust of foreigners made it difficult for the West to send in food and medical supplies.(24)

Meanwhile, the separatist factions resumed their offensives. The TGLF conquered all of Tigre and began raiding neighboring provinces. In 1988 the EPLF captured Afabet, the headquarters of the Ethiopian army in northeastern Eritrea, and the Soviet Union announced that it would no longer support the Ethiopian government. Officially the Soviets claimed they were dissatisfied with Ethiopia's economic and political development, but in truth the USSR was now bankrupt, and would soon collapse; whatever the reason, it sealed Mengistu's fate. In 1989 the TGLF merged with some other opponents of the regime to create a more universal movement, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPDRF), and later in the same year Mengistu agreed to peace talks with both the EPDRF and the EPLF. However, this did not keep the rebels from fighting--and winning; the EPLF captured Massawa in 1990 and Asmara in 1991, completing its conquest of Eritrea. As for the EPDRF, it marched on Addis Ababa in 1991. The Ethiopian army lost its will to fight, and 50 leaders of the government fled the country; Mengistu found refuge in Zimbabwe, and still lives there, in a mansion provided by Robert Mugabe.

The EPRDF now joined several smaller groups to form a transitional government, led by the former leader of the TGLF, Meles Zenawi (1954-). Following a referendum, Eritrea became independent in 1993, with EPLF leader Isaias Afwerki as its first president. In 1994 Ethiopian voters elected a Constituent Assembly to write a new constitution; in 1995 a new legislature, the Council of People's Representatives, was elected, and Zenawi became the prime minister.

Not everyone is happy with these arrangements. Some members of the Oromo and Amhara tribes consider Ethiopia's present-day government to be no more legitimate than the communist one it replaced. In the Ogaden, Somali rebels made another bid for independence, resulting in some battles between Ethiopia and Somalia in 1996. And while Ethiopia and Eritrea were on cordial terms when they parted, they fought a war from 1998 to 2002, because the border between them is not precisely defined. Currently 4,000 UN peacekeeping troops stand between the two countries, and will probably stay there until both sides accept a final border ruling; the war also created yet another landmine-infested zone for Africa. Despite all this, Zenawi was reelected in 2000. It looks like stability has come to Ethiopia, which is more than you can say for neighboring Somalia.

Somalia

Things were never again the same for Mohamed Siad Barre, after he lost the Ogaden War of 1977-78. For most of the 1970s he had been popular, because it looked like he would modernize Somalia and achieve the dream of unifying the Somali people (see Chapter 8, footnote #23); when it became clear that "Greater Somalia" wasn't going to happen, organized opposition began to appear, to which Siad Barre responded with jailings, torture, and summary executions of dissidents, coupled with the collective punishment of their clans. His new Western allies were reluctant to support him as well, because Somalia had no freedom of expression, and military aid was likely to be used against Ethiopia; the aid they sent was always much less than what Siad Barre asked for.

In 1982, Somali dissidents backed by the Ethiopian army and air force invaded central Somalia. Siad Barre immediately called for help, and the United States increased the amount of military and economic aid from $45 to $80 million. Somalia managed to defeat the invasion, but most of the American aid was used to repress domestic opponents. In 1984 Somalia buried the hatchet with another neighbor it hadn't gotten along with, by signing a treaty with Kenya that permanently renounced Somalia's claim to Kenyan territory. Around the same time, Somalia also normalized relations with South Africa, and did the same with Libya in early 1985 (Libya had favored Ethiopia during the Ogaden War); Siad Barre's situation at home was getting more critical every year, to the point that he would now accept arms from anybody.

Siad Barre also kept control in the early 1980s by filling available government positions with members of his own clan, the Mareehaan. In May 1986, he was severely injured in an auto accident; although he had diabetes, he recovered enough after a month to go back to work. During his recuperation, however, his four top-ranking generals competed with the president's brother, son and senior wife to grab as much power as possible. The rest of 1986 saw purges of officers who weren't considered absolutely loyal, which weakened the ministries they worked in as well, and those officers who remained started plundering the treasury.

Siad Barre's reign of terror was mainly directed against three clans, the Majeerteen, the Isaaq and the Hawiye. They revolted when they saw themselves shut out of the government, but the government won most of the battles until the crisis of 1986. After that Siad Barre was openly at war with much of the nation; Somali planes bombed cities in rebel-held areas, and government troops massacred opponents in the neighborhood of Mogadishu. The United States cut off aid in 1989, and the army dissolved into small groups loyal to their commanding officers or to clan leaders. By 1990, Siad Barre controlled little besides Mogadishu. In the capital's main stadium, a demonstration against the president on July 6, 1990 turned into a riot, and Siad Barre's bodyguard opened fire on the demonstrators, killing 65. A week later, Siad Barre put on trial several members of the Manifesto Group, 114 signers of a petition that called for elections and human rights. 46 were sentenced to death, but during the trial more demonstrators surrounded the court; everyday activity in Mogadishu stopped, and Siad Barre got nervous enough to drop the charges against the accused. As the city celebrated this political victory, Siad Barre moved into a military bunker near the airport to save himself, should the people come after him. Then the clans opposing the government formed a united front and marched on Mogadishu. Siad Barre fled the country in January 1991; four years later he died in exile in Nigeria.

Siad Barre had led a brutal regime for more than twenty years, but at least it was a regime; nothing resembling a government could be set up after he left. Only their dislike for Siad Barre had united the opposition. In the northwest, the territory that had once been British Somaliland declared its independence, calling itself the Republic of Somaliland. Two warlords in Mogadishu were proclaimed president, Mohammed Ali Mahdi and Mohammed Farah Aidid, so gun battles broke out between their followers. In the rest of the country, authority above the local level simply disappeared. With the landscape rendered desolate by the drought, patrolled by gangs of ragtag militias made up largely of drug-addicted kids (the drug of choice is a hallucinogenic plant named qat), driving pickup trucks jury-rigged with guns stolen from more professional armies, Somalia came to look like a real-life version of the post-nuclear Australia portrayed in the "Mad Max" movies. 50,000 were killed in fighting between factions over the rest of 1991 and 1992, while a devastating famine claimed 300,000 more lives. Even sailing off the Somali coast became a risky proposition; pirates appeared in that part of the Indian Ocean for the first time in centuries.

The first food sent by the United Nations was simply confiscated by soldiers, never reaching the starving folks it was intended for. In response to this, the UN launched Operation Restore Hope; nearly 30,000 peacekeeping troops, led by the United States, arrived in Somalia in December 1992 to guard the next shipments of humanitarian aid, and to protect ports, airports and roads. A lot of lives were saved in the relief effort that followed, but the bully-boys were hostile to these armed newcomers, and intended to undo anything accomplished. When the UN realized this, "mission creep" set in, and the assignment of the peacekeepers changed from feeding the hungry to restoring order. A proposal was floated to reintegrate Somalia through a transitional government, with eighteen autonomous regions under a federal authority. Most of the warlords went along with this plan, and the peacekeepers began to disarm their militias. Mohammed Farah Aidid, however, would not comply, and June his force killed 24 Pakistani troops inspecting a weapons storage site. Now the Americans, backed by helicopters, swept through the city to arrest Aidid, but whenever they torched a building or broke into it, he wasn't there. This led to the battle of Mogadishu on October 3, 1993, in which between 500 and 1,000 Somalis, 18 Americans and one Malaysian were killed. Two MH-60 Black Hawk helicopters were shot down, and the body of one of the Americans was dragged through the streets. CNN got pictures of all this, and the outcry was so great that the United States decided to cut and run; the last Americans left Somalia in March 1994, and the rest of the peacekeepers were withdrawn by early 1995.(25)

Back in Mogadishu, Aidid died from gunshot wounds suffered in a 1996 battle. Paradoxically, his son, Hussein Mohammed Aidid, had lived in the United States since 1979; now a US citizen and a Marine, he was a veteran of Operation Desert Storm, and actually went on the recent mission to Somalia, because he was almost the only Marine who spoke Somali. The younger Aidid had to resign from the US Marine Corps to assume leadership of his father's militia. In 1997 he gave up his claim to the presidency by signing the Cairo Declaration. Then from 2005 to 2008 he held three positions in the Transitional Federal Government (Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of the Interior, and Minister of Public Works and Housing), before defecting to Eritrea.

The rest of the 1990s saw further splits. In 1998 the area north and east of Mogadishu declared itself the independent state of Puntland; the name comes from the idea that the land the ancient Egyptians called "Punt" was here (see Chapter 2, footnote #17). Then in 1999, the area south and west of Mogadishu declared independence as Jubaland, deriving its name from the Juba River. Like Somaliland, none of these states has yet received diplomatic recognition from any foreign government. Of all three quasi-states, Somaliland is the most stable; it has seen two presidents so far (Mohammed Ibrahim Egal, 1993-2002, and Dahir Riyale Kahin, 2002-present), and was largely unaffected by both the recent civil war and the UN intervention, both of which were concentrated in the south.

From 1997 onwards, the main clan leaders made arrangements for a super-conference, in which hundreds of rival clan members would hammer out a new government. Fighting between the factions delayed the conference several times. The conference finally took place in Djibouti, lasting for five months in 2000. The participants at the conference elected a Transitional National Government (TNG), with a legislature and a president. However, it failed to accomplish much else before it expired in 2003. It didn't even control all of Mogadishu; the 2004 elections to create a second TNG had to be held in a stadium in Nairobi, and the legislature still meets in the Kenyan capital.

At the time of this writing, Somalia is less chaotic than it was in the last years of the twentieth century, but not by much. The TNG has not yet found a way to reintegrate Puntland, Jubaland and Somaliland under its rule. It seemed like Somalia was coming back together when Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, the president of Puntland, was elected president of the TNG in 2004, but as soon as he moved to Mogadishu, Puntland chose another president to take his place. In much of the former Somalia, anarcho-capitalism seems to be the rule; private companies are popping up to provide the services that governments normally provide elsewhere. Ironically, that may be why there is less violence these days; the various militias have found employment as security agencies, and everybody agrees it would be better not to fight than to do anything that would prompt the UN or African Union to send another peacekeeping force. Under those circumstances, attempts to put Somalia back together could make trouble, rather than reduce it; one observer remarked that "state-building and peace-building are two separate, and, in some respects, mutually antagonistic enterprises in Somalia."(26)

Southern Africa: The Fall of Apartheid

Rhodesia/Zimbabwe

When last we looked at southern Africa, South Africa and Rhodesia were governed by regimes that practiced a harsh white-supremacy policy. They were able to get away with this, despite near universal condemnation, because they had jobs black Africans needed, resources the industrialized nations wanted, and defense in depth: most of the surrounding lands were either white-ruled colonies (Southwest Africa/Namibia, Angola, and Mozambique) or British protectorates (Bechuanaland/Botswana, Basutoland/Lesotho, and Swaziland). Nobody in the region was strong enough to challenge South Africa, and only Tanzania and Zambia were willing to confront Rhodesia head-on. From bases in Zambia, the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), launched guerrilla raids into Rhodesia as early as 1964, but most of these ended in disaster; the Rhodesians had little trouble defending their frontier along the Zambezi River, and could count on the South Africans to back them up. When another black nationalist movement formed, the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), it chose to build its bases in Mozambique, where it would be difficult for Rhodesia to retaliate without the permission of Portugal; ZANU could also share training facilities in Zambia and Tanzania with FRELIMO, Mozambique's nationalist movement. At the end of 1971 ZAPU and ZANU began to coordinate their attacks, turning up the heat on Ian Smith's regime.(27)

When Angola and Mozambique became independent in 1975, both promptly joined the "frontline states" opposing white rule, and the scales began to tip against South Africa and Rhodesia. Botswana also declared itself a frontline state (though it could only provide verbal support), Angola provided additional bases for SWAPO, and ZAPU and ZANU merged their forces into one liberation army, the "Patriotic Front"; Rhodesia thus found itself surrounded by enemies on three sides. White Rhodesians were leaving the country in large enough numbers that even Ian Smith could see time was running out for his government, so when South Africa prompted him to negotiate a compromise, he did so with three moderate black leaders, all clergymen--a Methodist bishop, Abel Muzorewa, Rev. Ndabaningi Sithole, and Rev. Jeremiah Chirau. At the end of 1978 they agreed to a new constitution that allowed limited majority rule and safeguards for whites; Muzorewa was elected prime minister, and the country's name was changed to Zimbabwe-Rhodesia. However, the Patriotic Front, which demanded all or nothing where the government was concerned, refused to take part in the elections, and it called Muzorewa a puppet of the whites. Nor was the new state any more popular abroad than its predecessor. In 1980 the Rhodesian government accepted British and American mediation to produce a more acceptable government, and Rhodesia briefly became a British colony again, until new elections could be for majority rule, this time with no strings attached.

South Africa had leaned on Smith because it decided that it could live with a black government next door, if it was a moderate one like Botswana's. Instead, all the previous years of white intransigence made sure this wouldn't happen. When the elections were held in March 1980, most blacks voted for their tribe's candidate for prime minister, and Robert Mugabe won by a landslide. Zimbabwe-Rhodesia became simply Zimbabwe, and in 1982 the capital's name was changed from Salisbury to Harare.

Robert Mugabe.

Mugabe governed cautiously at first. He felt it was payback time, and that Zimbabwe should have an all-black society, but he couldn't discriminate too much against the whites as long as South Africa was under white rule. South Africa threatened to destabilize his regime because he supported the African National Congress (ANC) and Mozambique's government; Mugabe would have preferred to ship Zimbabwean exports through Mozambique, but the civil war between FRELIMO and RENAMO meant he couldn't do without South Africa completely. Also, he had been forced by the 1980 agreement to share power; his rival Joshua Nkomo became vice president, due to his second place showing in the 1980 elections, and 20 of Parliament's 100 seats had been reserved for whites, coloreds and Asians. An uprising broke out in Matabeleland in 1982, because Ndebele dissidents questioned the validity of those elections; at least 20,000 were killed in the massacres that followed, and Nkomo and other ZAPU party members were expelled from the government. After that Mugabe made several moves to centralize power under himself. In 1986 he amended the constitution to eliminate the "non-black only" seats; in 1987 he combined the two offices of president and prime minister(28); in 1988 he and Nkomo agreed to merge ZAPU and ZANU into one party, called ZANU-PF. The new super-party won 82 percent of the vote in the 1995 legislative elections, and Mugabe was reelected president in 1996, running unopposed after two opposition candidates withdrew, protesting that the election rules were unfair.

Zimbabwe's economy did eventually tank, but South Africa was not responsible; Mugabe did it all by himself. By this time most of Zimbabwe's whites were long gone--those remaining amounted to 1 percent of the population--but they still owned at least half of the farmland. In 1997 Mugabe announced that he would not tolerate this any longer; 1,500 white-owned farms would be seized without compensation and given to blacks who owned little or no land. Strong protests by white farmers and the international community, combined with a national strike, persuaded Mugabe to back down. He brought up the issue again in February 2000 with a constitutional referendum that would have allowed Mugabe to run for another term as president, and allowed the government to seize white-owned farms without compensation. Voters rejected the referendum, but he went ahead and acted as if it had been passed anyway. Soon squads of armed goons, with government approval, were chasing whites away from their farms. Those farmers who did not run away were arrested, and sometimes even killed; employees of the farmers simply lost their jobs. However, the redistribution of land was neither fair nor productive. London's Daily Telegraph reported in May 2002 that vast tracts of land were "handed out to President Mugabe's closest allies, including 10 cabinet ministers, seven MP's [members of Parliament] and his brother-in-law." Most of these folks didn't know anything about farm management, so irrigation and planting nearly stopped, and yields dropped 90% from previous levels. There was a drought in southern Africa in the late 1990s, but Zimbabwe saw no recovery after the rains came back. Instead, Mugabe used the famine to get rid of as many political opponents as possible, the way Joseph Stalin did with a Ukrainian famine in the 1930s. Nor could people buy imported food; hyperinflation made much of it unaffordable, and Harare officials either prevented emergency shipments of food from entering the country, or made sure that only card-carrying ZANU-PF members got it.

A Zimbabwean half-million-dollar bill. When the author first saw this picture (January 2008), that amount of money was worth twelve U.S. cents.

Mugabe ran for president in 2002, again ignoring the rejection of his referendum. He won, and many saw the election as unfair; the U.S. State Department described the election as "marred by disenfranchisement of urban voters, violent intimidation against opposition supporters, intimidation of the independent press and the judiciary and other irregularities." Despite acts of violence in anti-Mugabe areas, his opponent, a trade union leader named Morgan Tsvangirai, managed to get 40 percent of the vote, leading some to wonder if he could have won in a free election. Since then, pressure on his regime has increased, and Mugabe has responded by increasing the pressure on his own people. In 2002 Zimbabwe was suspended from the British Commonwealth, and Zimbabwe quit the organization shortly after that. Individual Western nations like the United States and Australia imposed travel and economic sanctions on Zimbabwe; a March 2003 EU-African summit meeting was postponed indefinitely because the African participants insisted that Mugabe be invited and Britain refused to attend if he came. In June 2005 Mugabe launched "Operation Restore Order," a campaign against the urban poor that bulldozed shacks, workshops, market stalls, churches and a mosque in Harare. At least 700,000 were left homeless, and they called this action "Zimbabwe's tsunami," comparing it with the tidal wave that struck the countries around the Indian Ocean in December 2004. Later in the same year, the International Monetary Fund began discussing the expulsion of Zimbabwe from that organization, because Zimbabwe owes it $295 million and rarely makes a payment on it.

Ravaged by disease and starvation, with 70 percent of its population unemployed, Zimbabwe, once the second richest country in Africa, is now running on empty. The title of a Wall Street Journal story, dated December 24, 2003, neatly summarized the situation: "Once a Breadbasket, Now Zimbabwe Can't Feed Itself." Zimbabweans routinely sneak across the border into Mozambique to buy what they cannot get at home, which is almost everything (a few years ago the refugee traffic went the other way, with Mozambicans fleeing into Zimbabwe). Travel agencies advise tourists visiting Victoria Falls to approach that marvel from the Zambian side of the Zambezi River. The aged Mugabe has become what he once fought: a tyrant. He managed to keep himself in charge by blaming his problems on enemies abroad, especially white enemies. The African Union faced its first test in what to do about Zimbabwe, but African leaders refused to even criticize Mugabe, because they still view him as a freedom fighter; about the only prominent African who has spoken up is a Nobel laureate, former Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Most of the criticism he did get came from George W. Bush and Tony Blair, so Mugabe found new friends among their enemies; he was a prominent guest of France in 2003, and the United Nations gave Zimbabwe a seat on the Human Rights Commission, along with other enemies of democracy like Libya, Cuba, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria and Vietnam. With Zimbabwe's economy in the toilet, Mugabe gave his foreign friends the only gift he could afford--wild animals such as elephants, rhinos, giraffes, zebras, and hyenas--even when sending the animals abroad meant certain death to them. Alas, the moral to the Zimbabwe story is that liberty on an empty stomach is worthless.(29)

South Africa

South Africa's hardline president, Hendrik Verwoerd, was assassinated in 1966--ironically, the killer was a white who thought Verwoerd's racial policies were too liberal. He was succeeded by Balthazar Johannes Vorster, who was just as intransigent. In the same year, the question of what to do with Namibia came up again. The last of the old League of Nations mandates, it had been under South African rule for more than forty years at this point. South Africa had refused to give it up when Europe and the United Nations pressured it to do so; now the UN General Assembly voted to declare South Africa's rule over the territory illegal. Another nationalist organization formed to force the South Africans out, the South-West Africa People's Organization (SWAPO). Like ZAPU, it started by staging attacks from bases in Zambia, but they were weak and ineffective at this stage.

The transformation of Rhodesia into Zimbabwe meant that South Africa was now alone against the world, but South Africans had been expecting this day for a long time. They didn't really have to worry about an invasion from outside, because their armed forces were excellent and well-equipped, and their mineral and agricultural output was too important to the world economy to risk its loss in a war. The biggest danger to apartheid came from subversive elements within South Africa's borders, so the country built up the best police and intelligence service in the noncommunist world. At home, the ruling National Party also maintained a conservative social policy; most vices, such as gambling, pornography and racy movies, were banned completely. Most businesses, especially cinemas and liquor stores, had to close from Saturday afternoon to Sunday morning, so that the Sabbath would remain a holy time, and while abortion and sex education were legal, heavy restrictions sharply limited the practice of both. Television was not introduced until 1976, because it was considered immoral.

Abroad, South Africa would try to make a deal with any African country that was willing to listen, such as Malawi, and backed counterrevolutionary movements in the frontline states (e.g, UNITA in Angola, RENAMO in Mozambique).(30) Even Mugabe had to tone down his Marxist rhetoric and policies for much of the 1980s, because Zimbabwe's economy still depended on South Africa.

South Africa had one more advantage not often seen in modern, Westernized states--it was quite willing to dispose of those it considered dangerous, even if it meant putting down demonstrations with a heavy loss of life. We saw this with the Sharpeville massacre in 1960. It happened again at Soweto, a huge black settlement near Johannesburg that formed when several older townships merged together. In 1974 the government had issued the Afrikaans Medium Decree, which forced all schools to use the Afrikaans language when teaching mathematics, social sciences, geography and history to blacks at the secondary school level. The reasoning was that an African student might some day work for a white boss who spoke only Afrikaans or English, so it would be a good idea to teach him both languages. Blacks, however, didn't feel this way; English may be useful almost anywhere, but only their oppressors spoke Afrikaans. Students in Soweto stopped going to school to protest the Afrikaans policy, and when they held a mass rally on June 16, 1976, police responded by using bullets against rock-throwing children. More riots broke out in other parts of South Africa, and by the time the police restored order, 575 people had been killed.

Some enemies of apartheid fell victim to "death in custody." The chief example of that was Steve Biko (1946-77), a medical student who had founded the Black Consciousness Movement. This group patterned itself after the civil rights movement of the United States, and Biko wanted to repeat in South Africa what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. had achieved. But while the movement may have been non-violent, the authorities could only tolerate it for so long. In 1977 they arrested Biko and beat him until he went into a coma; he died three days later. This led to an international outcry, and further radicalized black South African students, whose slogan was now "liberation before education."

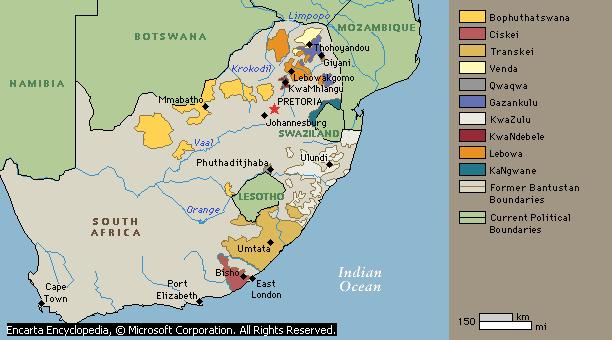

Meanwhile, Vorster and Pieter W. Botha, who succeeded him in 1978, carried out apartheid's program of resettling as many blacks as possible in ten "Bantustans," or tribal homelands. The homeland of the Xhosa tribe, Transkei, was declared independent in 1976. Soon all the Bantustans were self-governing; by 1981 independence had been granted to three more: Bophuthatswana, Venda and Ciskei. As we noted in Chapters 7 and 8, the homelands were not economically viable, lacking cities and industry, and the lands of most were unconnected tracts scattered across white-ruled areas. No foreign government recognized the Bantustans, and outside condemnation combined with internal unrest to halt the program after 1981; in 1994 the Bantustans were all reabsorbed into South Africa.(31)

The Bantustans.

During the 1980s, international pressure steadily mounted on South Africa. The United Nations voted in 1974 to suspend South Africa's membership in the General Assembly, and a call went forth for investors to "divest" their funds from companies that did business with that country. By the mid-1980s this was hurting South Africa's once impervious economy, forcing a devaluation of the rand, the country's monetary unit. In addition, there was violence from blacks who wanted to see apartheid ended now, and counter-violence from a number of white-run neo-Nazi groups, who thought Botha had already gone too far. Finally, there were demographic factors: AIDS began to take its toll, especially among miners and other migrant workers, and the low white birthrate meant that the European portion of South Africa's population had shrunk, from 22 percent in the early twentieth century to 16 percent, a dangerous situation for an elite that wanted to keep all the power and wealth for itself. Under these circumstances, Botha warned that the time had come for change, and that white South Africans would have to "adapt or die." In 1983 he transformed Parliament into a tricameral body that had three separate chambers: one for whites, one for Asians, and one for coloreds. Then a series of reforms did away with the unpopular aspects of petty apartheid, such as the passbook laws and the laws against interracial marriage. However, Botha couldn't bring himself to do much that would improve the lives of the black majority. The fact that blacks were excluded from the new Parliament caused more than three fourths of colored and Asian voters to boycott the 1984 legislative elections. Incidents of violence increased, leading to 2,000 deaths and 20,000 arrests; a state of emergency was declared in 1985, which lasted until 1990.

In 1989, Botha suffered a stroke and had to resign; the next president, Frederik Willem de Klerk, was willing to make the hard decisions that his predecessors kept putting off. At his opening address to parliament in February 1990, de Klerk announced that he would repeal discriminatory laws and lift the ban on the ANC, the Communist Party, and other anti-apartheid groups. In addition, he allowed large demonstrations in Cape Town and Johannesburg, met with black leaders like Desmond Tutu, and released Nelson Mandela from prison, 27 years after he had been locked up under a life sentence.

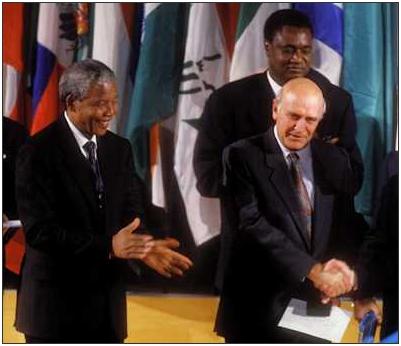

For working together to end apartheid, both Nelson Mandela (left) and F. W. de Klerk (right) received the Nobel Peace prize in 1993.

A long and difficult negotiation period followed Mandela's release, in which all parties concerned discussed what post-apartheid South Africa would look like. The NP was an unwilling participant in these talks, since it meant getting rid of the NP's ideology, and for much of the time it tried to insert a minority veto, or anything else that would prevent rule by "one man, one vote." Whenever progress ground to a halt, the ANC staged strikes and nonviolent protests. In the end it took a special commission, the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA), to reach a compromise between the NP and the ANC. On November 13, 1993, both sides agreed to free elections that would establish a coalition government for a nonracial, nonsexist, unified, and democratic South Africa.

When these elections took place (April 27, 1994), they were arguably the most important in modern African history. The ANC won an impressive 62.7 percent of the vote, a little less than the two-thirds majority that would have given it the power to amend the constitution without the approval of other parties. The NP got 20 percent, more than expected because colored and Asian voters who feared ANC domination went with that party. Only two other parties won the 5 percent minimum needed to be represented in the government: the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), a Zulu nationalist movement led by Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, and the Freedom Front, a coalition of white extremist groups. The ANC also came out ahead in seven of the nine new provinces that had been created to replace the four oversized provinces that existed previously; the only two the ANC didn't win were the Western Cape province, where the NP won, and KwaZulu-Natal, the IFP's home. Nelson Mandela was elected president, de Klerk became one of the two vice presidents, and Thabo Mbeki, an ANC associate, became the other vice president.

A meeting of two former rebels turned statesmen: South Africa's Nelson Mandela (left) and Uganda's Yoweri Museveni (right).

Following the elections, South Africa rejoined the British Commonwealth of Nations (June 1994). Mandela had his work cut out for him; he needed to restructure the economy so that all ethnic groups would benefit under the new South Africa. There was also the need to uncover the full story of the crimes committed in the name of apartheid, and to promote healing from the pre-1994 era, without further polarizing society. To do this, the government created the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which met from 1996 to 1999. Here victims told their stories and perpetrators confessed their crimes, with possible amnesty to the latter. Those who did not appear before the commission would be prosecuted if their guilt could be proven. Activities of the ANC as well as the government were investigated, and in the end the commission condemned actions from all the country's major political organizations. Desmond Tutu presided over the sessions (he had to retire from his position in the clergy to give the commission his full attention), and explained their purpose thusly: "Without forgiveness there is no future, but without confession there can be no forgiveness." Still, many people wanted those found guilty to pay reparations, and while some soldiers, police, and ordinary citizens confessed their crimes, most of those who gave the orders did not show up to testify; the latter included former President Botha, due to his age and poor health.

In 1996 Mandela announced he would retire when his term as president expired, and one year later Thabo Mbeki took his place as head of the ANC. The next time elections were held, in June 1999, the ANC again won easily and Mbeki became South Africa's second black president. Though not admired worldwide like Mandela, Mbeki proved to be an accomplished politician. In 2003, Mbeki maneuvered the ANC to a two-thirds majority in parliament; in the April 2004 parliamentary elections the ANC won almost 70 percent of the seats, ensuring that Mbeki would be reelected as president.(32)

South Africa dropped off the world's radar screen when apartheid disappeared; the country hasn't attracted much attention since 1994. But while the outside world may think South Africa's story concluded with a happy ending, there are serious problems with unemployment, poverty, AIDS and crime. Mbeki invited criticism during his first term for keeping silent about the heavyhanded behavior of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe, and for denying any connection between AIDS and the HIV virus. Nonpolitical crimes also jumped dramatically; one report declared that violent crime increased 33 percent between 1994 and 2001.(33) According to 2002 figures, South Africa has the world's highest murder rate, 114.8 murders per 100,000 people.(34) In response, Mbeki accused his critics of racism, and published his own statistics which showed a much lower crime rate.

Meanwhile, South Africa's whites are leaving the country; the South African High Commission in London thinks there may be 1.4 million South Africans in Britain. They are not likely to return if they believe South Africa is no longer their country. Other whites have moved into private, gated communities, where they have little contact with blacks.(35) Although the whites have lost political power, they still control the economy and most of the media; if the country is to prosper, the blacks must have access to better jobs, but that also means many whites will lose their jobs, which is likely to cause trouble, at least in the short run. If there is a moral to the history of southern Africa, it may be that in this part of the world, blacks and whites can't live with each other, but they can't live without each other, either!

Southwest Africa/Namibia

While dismantling apartheid, de Klerk also ended the impasse on Namibia. For most of the 1970s and 1980s South Africa refused to get out of the former mandate, mainly because a black guerrilla army had triumphed in Zimbabwe, and South Africa didn't want to see the same thing happen here. They said a withdrawal from Namibia should be linked to a withdrawal of the Cubans from Angola, and because Angola was one of the hot battlegrounds of the Cold War; the United States agreed. Finally there was a controversy over Walvis Bay, the only deep-water port on Namibia's coast; it had never been part of German Southwest Africa, so the South Africans were reluctant to give it up. The UN put forward more than one plan for independence, but something always got in the way. Then in December 1988, Angola, Cuba and South Africa signed an agreement in New York that resolved their differences. Tragically, the UN commissioner who was supposed to oversee the signing ceremony, Bernt Carlsson, could not attend; he was one of the passengers killed on Pan Am Flight 103 (see the section on Libya). The South African delegation, led by Foreign Minister Roelof "Pik" Botha, very nearly suffered the same fate, but their booking on 103 was cancelled at the last minute and they took Pan Am Flight 101 instead.

A transitional period followed, and elections were held in November 1989; SWAPO won 57 percent of the vote, despite heavy funding from the South African government to seven anti-SWAPO parties. Independence finally came on March 12, 1990, with SWAPO's leader, Sam Nujoma, sworn in as the first president of Namibia.

As a guerrilla leader, Nujoma had been a Marxist; after becoming president he encouraged a healthy, growing economy and respected human rights. Whites still owned a disproportionate share of Namibian land, and Nujoma wanted to see most of it eventually transferred to nonwhites, but unlike Mugabe, he wasn't going to disrupt the economy to do it. South Africa handed over Walvis Bay to Namibia in 1994, after three years of negotiations, and Nujoma was reelected later in the same year. Namibia's constitution only allowed two terms, so Nujoma amended it to permit a third, and ran for it in 1999. He seemed to have lost interest in serving during his third term, though, because instead of amending the constitution again, he groomed Hifikepunye Pohamba to run as the SWAPO candidate in 2004. He was seventy-five years old by this time, but longevity seems to run in his family; his mother, Mpingana Helvi Kondombolo, was reportedly alive and more than a century old in 2004. Whatever the reason for Nujoma's retirement, Pohamba became the country's second president in March 2005.

Rwanda, Burundi, and the Congo: Still the Dark Heart of Africa

When the Cold War ended, a writer named Francis Fukuyama wrote a book called "The End of History," which claimed that with the defeat of capitalism's last opponent, political and ideological history were over, and that henceforth historical events would mainly have to do with economics. Of course he spoke too soon, as you will see when you read "The Islamist Menace", later in this chapter. And whenever the rest of the world gets dull and complacent, some horrifying news story from Africa comes along to wake us up again. Most often those stories come from one of the four equatorial nations covered in this section.

We will look at the Republic of the Congo (also known as Congo-Brazzaville) first, since its history is the shortest, and not intertwined with the other nations. This Congo has never been managed very well, and every time the government destabilized, a more radical one took its place. The first president, a former Catholic priest named Fulbert Youlou, was deposed in 1963, when labor unions and rival political parties launched a three-day uprising. The military briefly stepped in and installed another civilian government, which wrote a new constitution and elected Alphonse Massamba-Débat as president. He improved Congolese relations with the communist world, especially China, but for the armed forces this wasn't good enough; in August 1968 Capt. Marien Ngouabi led a coup that toppled Massamba-Débat and put himself in power. Under Ngouabi's rule, Congo became Africa's first communist state (Ethiopia, Mozambique and Angola waited until the mid-1970s to try communism); in 1970 he renamed the country the People's Republic of the Congo.

Ngouabi was assassinated in 1977. Among the alleged killers was Pascal Lissouba, a former prime minister under Alphonse Massamba-Débat; he was sentenced to life imprisonment, which was later changed to exile, and Lissouba stayed abroad until 1991. Other conspirators were tried, convicted and executed, but it was never clear why they did it; the Congo remained under one-party Marxist rule. An eleven-member committee of officers took charge, led by Col. (later Gen.) Joachim Yhombi-Opango. Two years later Yhombi-Opango was accused of corruption and deviation from party directives, removed from office, stripped of all powers and rank, and placed under house arrest until 1984. In his place the committee promoted Vice President and Defense Minister Col. Denis Sassou-Nguesso, who was subsequently elected president and reelected in 1984 and 1989.

Sassou-Nguesso signed a treaty of friendship and cooperation with the Soviet Union in 1981, but time was running out for his Marxist-Leninist partners. He had second thoughts following the USSR's collapse. A national conference followed, which changed the country's name back to the Republic of the Congo, replaced the flag and national anthem, and legalized opposition parties (1991-92). The country saw its first multiparty elections in August 1992; Pascal Lissouba came back from exile and defeated Sassou-Nguesso to become the new president.

However, the elections didn't mean that anyone would live happily ever after; this is Equatorial Africa, for crying out loud! Lissouba was accused of discriminating against Sassou-Nguesso's tribe, the Mbochi, and because the legislative elections of 1993 only gave a slim majority to Lissouba's party, the results were disputed, leading to rounds of violent unrest in 1993 and early 1994. In June 1997, one month before the next scheduled presidential elections, government troops surrounded Sassou-Nguesso's compound in Brazzaville. Sassou-Nguesso ordered troops loyal to him to resist, and the result was a four-month civil war that killed 10,000 and destroyed much of Brazzaville. Outside intervention decided the winner; Angolan troops invaded in October on the side of Sassou-Nguesso, driving Lissouba into exile again.

A number of militias still opposed the Sassou regime, and 1998 and 1999 saw negotiations between the factions, mediated by President Omar Bongo of Gabon. They eventually signed a peace accord that gave amnesty to most of Sassou-Nguesso's opponents, except for Lissouba and his prime minister, Bernard Kolelas; the latter two were tried and convicted in absentia for treason and war crimes. A new constitution was approved by the voters in 2002, and Sassou-Nguesso was elected to a seven-year term in the same year; he faced no significant opposition because Lissouba and Kolelas were outside the country, and thus kept from running by residency laws.

In Rwanda and Burundi, the chief problem was the ongoing antagonism between the Hutu and the Tutsi. When we first saw these tribes, in Chapter 6, they had different origins: the Tutsi were of Nilotic origin and the Hutu were Bantus. The Hutu were usually in the majority, but the Tutsi were the ones in charge. Centuries of living together, however, blurred the differences between the tribes, and there were enough cases of people switching tribes that by the twentieth century, the terms "Hutu" and "Tutsi" became labels of one's profession and social class, rather than labels of one's racial identity. Laurent Nkongoli, a Rwandan politician, explained it by saying that frequently "you can't tell us apart, we can't tell us apart."

Even when Belgium ruled both countries, there had been large-scale violence. Rioting had driven the last Tutsi king out of Rwanda in 1959, and over the next year between 20,000 and 100,000 Tutsis were killed, and another 200,000 fled the country; this allowed Hutu nationalists to make sure that Rwanda would become a Hutu republic, with Grégoire Kayibanda as president, when independence arrived in 1962. Another massacre took place in 1963, after some Tutsis returned as a rebel army and staged an unsuccessful takeover attempt. At this point Bertrand Russell, the Western philosopher, called the Tutsi massacres the worst event in human history since the Jewish Holocaust in World War II, but by and large the world did not pay attention. The tribal rivalry also meant that the two countries wouldn't take the same side in the Cold War; Rwanda aligned itself with the United States, while Burundi chose to go with China.

Burundi, unlike Rwanda, kept its Tutsi monarch, and launched acts of repression against its Hutus in retaliation for what happened in Rwanda, causing thousands of Hutus to flee the other way. However, both tribes were represented in Burundi's government. In 1966 the king, Mwami Mwambutsa IV, was deposed by his son, Mwami Ntare V; four months later the prime minister, Captain Michel Micombero, in turn abolished the monarchy and declared himself president. Ntare went into exile, but came back in April 1972, along with several thousand Hutu refugees. Having been promised safe passage, he expected a peaceful meeting with the man who threw him out; instead Micombero arrested, judged and executed the former king as soon as he stepped off the airplane. What a homecoming! What happened next is called the Burundian Civil War in history texts, but it was really a massacre of at least 100,000 Hutus, and another mass expulsion.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (also known as Congo-Leopoldville or Congo-Kinshasa), peace did not come right away when Joseph Mobutu took over in 1965. Local insurrections continued, and the loyalty of Katanga remained in question. In 1967 he dismissed the white mercenaries that the government had used during the civil war of the early 1960s, but instead of seeking employment elsewhere, the mercenaries occupied Stanleyville and Bukavu, with the help of Katangan rebels. The Congolese government declared a state of emergency, retook those cities, and eventually drove the mercenaries and their allies across the eastern border into Rwanda. Finally in 1968, the last internal rebellion was put down and its leader was executed. To signify that a new era had begun, Mobutu then embarked on a campaign to change all European names in the country; Leopoldville became Kinshasa, Stanleyville became Kisangani, and Elizabethville became Lubumbashi. In 1971 he changed the country's name to Zaire(36), the Congo River was renamed the Zaire River, and Katanga became Shaba, so that people would stop thinking of it as a center for rebellion. Finally he changed his own name to Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga ("the earthy, the peppery, all-powerful warrior who, by his endurance and will to win, goes from contest to contest leaving fire in his wake"--Mobutu Sese Seko for short), and advised all citizens to choose African names of their own.

Mobutu Sese Seko.

For the next twenty-five years, Zaire was relatively peaceful, except in 1977 and 1978, when Katangan rebels, based in Angola, staged two attacks on Kolwezi, the copper-producing center of Shaba/Katanga. Mobutu was able to defeat both invasions, with the help of US military aid and Belgian paratroopers. At first the return of peace brought impressive economic growth (6-7% a year in the early 1970s), but then Mobutu's policy of Africanization led him to do something you wouldn't expect from somebody who was supposed to be anti-communist; Mobutu nationalized all foreign-owned industry and grabbed small businesses belonging to Greek, Portuguese and Pakistani immigrants. These spoils were handed over to "sons of the country," which of course meant Mobutu's cronies, especially those from his own tribe, the Ngbanda. As with Robert Mugabe's confiscation of farms in Zimbabwe, the new owners were incompetent, and after 1973 the Zairean economy entered a decline from which it never recovered. Equally bad, this set a precedent for corruption that marked the rest of Mobutu's career.