| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A General History of the Middle East

Chapter 17: THE MOTHER OF ALL TROUBLE SPOTS: IRAN AND IRAQ SINCE 1948

This chapter covers the following topics:

The Mossadegh Affair

Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi inherited an Iran that was dirt poor, despite the efforts his father had made to modernize it. "It is no joy," the new Shah said, "to be the king of a nation of beggars." This was because of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, and its smaller American counterpart; both of them paid a small royalty for the right to pump Iranian petroleum, and kept most of the profits for themselves. In 1948, for example, AIOC earned $56 million from the oil it extracted and refined, while the Iranian government earned $20 million. Iran's poverty was so serious that the Shah delayed his coronation until 1967.

As early as the 1930s, some members of the Majlis (Iranian parliament) argued that nationalizing the oil industry would solve this problem and end foreign control over Iran's economy. Once the 1946 Azerbaijan crisis was over, those who favored oil nationalization became a major political movement, the National Front, led by Mohammed Mossadegh (1880-1967). By 1950 they had a widespread organization across the country, and were organizing mass political rallies. The Shah and some conservatives, however, opposed nationalization, because they felt it would do permanent damage to their relations with the West. In an effort to stop the move toward nationalization, the Shah appointed a military officer, Ali Razmara, as prime minister in 1950.

Not too long earlier, American oil companies negotiated a deal with another oil-producing country, Venezuela, that split the profits 50-50, and now Aramco and Saudi Arabia were discussing the same idea. This prompted AIOC to offer a 50-50 profit split, but the Majlis, led by Mossadegh, rejected it in December 1950. Mossadegh and his allies now wanted nothing less than complete nationalization. Only later did they realize that they were painting themselves into a corner; the stakes were now so high that anything besides a complete victory would look like a failure.(1)

Only four days after the prime minister asserted that nationalization was impractical, he was assassinated (March 7, 1951). Then the Majlis unanimously passed a bill nationalizing the AIOC, and took the unprecedented step of appointing Mossadegh as the next prime minister. Since the Shah wasn't confident that he could keep his throne, he reluctantly accepted both Mossadegh and the nationalization bill.

Britain simply refused to recognize Iran's right to run its oil industry. Refusing to cooperate with Mossadegh, Britain moved cruisers into the Persian Gulf, and blockaded oil exports from Iran. Most foreign countries, including the United States, complied because they didn't want to offend Britain. Financial organizations discouraged investment in Iran, oil production stopped because nobody would buy it, and the Iranians couldn't even sell the oil they had in storage. Britain thought that Iran's urgent need for money would cause Mossadegh to back down in a matter of weeks, but instead the crisis had the opposite effect: nationalistic pride persuaded the Iranian clergy, and most of the people, to throw their support behind Mossadegh.

Despite popular sympathy for the regime, the financial crisis got worse, and fearing the loss of Majlis backing, Mossadegh asked for, and got, the power to rule by decree like a dictator (August 1952). Because of this move, his followers began to desert him, and over the next year he resorted to methods like press censorship to silence the critics. He also started looking for support from the Iranian Communist Party (the Tudeh), a move that was sure to delight the Soviet Union and alarm the United States. Many Americans had favored the nationalists, viewing British attempts to keep Iranian oil money as a form of colonialism, but now the prospect of Iran turning communist persuaded them to listen to the Shah instead.

In mid-1953 Mossadegh held an election, and 99.93 percent of the voters gave him the power to dissolve the Majlis; previously only the Shah was allowed to do that. On August 12, Mossadegh announced that he would dissolve the Majlis; the Shah responded by sending him a message declaring that he was fired, and that General Fazlollah Zahedi would take his place. Mossadegh rejected the dismissal, and publicly announced that the Shah had tried to overthrow him. Riots broke out in the streets of Tehran, with people pulling down statues of the Shah, and troops rushed to Mossadegh's defense. The Shah and his wife fled abroad, while Zahedi went into the provinces, to organize those soldiers who remained loyal.

They weren't gone for long, though, for the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was working with conservative politicians and military officers to bring down the Mossadegh government. On August 19, a mob led by Zahedi's agents boiled out of the Tehran Bazaar, shouting "Long live the Shah"; loyalist troops and tanks quickly defeated their opponents and recaptured the capital. On August 22, four days after he had left, the Shah returned in triumph. Mossadegh was arrested, charged with treason, imprisoned for three years, and then kept under house arrest for the rest of his life. One year later the Shah reached an agreement with Britain that shared oil profits between Iran and a collection of British, Dutch, French, and U.S. oil companies; this increased Iran's income, but kept production levels and prices under foreign control. Even more welcome was a gift of $45 million in economic aid from the United States. For the rest of his career, the Shah maintained close ties with the United States, letting the world know that he was the strongest and most dependable ally of the West in the Middle East.

The Shah.

The White Revolution

During the first part of his reign, the Shah usually stayed out of politics. However, he had nearly lost everything in 1953, so after that, it was "No more Mr. Nice Guy!" From then on he was obsessed with strengthening both the Iranian state and his rule. He built up the military until it was the strongest in the Persian Gulf region, arguing that these armed forces were needed to stop the expansion of both communism and radical Arabism. To keep him friendly, the United States followed a simple policy: it gave or sold to the Shah everything he wanted. His army used American-made equipment, and was trained by American advisors. Later on, when dissent grew, he used American help to create an elite miniature army as his secret police force, the Sazeman-e Etala'at va Amniyate Khasvar, SAVAK for short.

His land reform program, which took away surplus land from the landlords and gave it to 10 percent of the peasants, was very popular, so in January 1963 announced a more comprehensive plan, which he called the "White Revolution," the idea being to prevent a Red, or Communist, revolution from originating at the grass roots level. This plan called for more land reforms, universal education, and gave women the right to vote and run for office. The mosques lost some of their holdings in the redistribution of land, and the clergy wouldn't consider equality for women, so now the Shah began to stir up some very serious opposition. The middle class expanded, but much of the urban growth resulted from poor villagers seeking city jobs, causing slums to mushroom on the outskirts of the cities. Government policy focused on the creation of modern industrial facilities, but neglected the development of social services. At the same time, economic success caused the Shah to grow less tolerant of dissent. Newspapers, for example, were not allowed to use red ink, because red symbolized communism. By the mid-1970s, it was well known that SAVAK was torturing dissidents, and that began to overshadow the regime's positive accomplishments.

Meanwhile, the Shah continued his reforms, now adding pride in the ancient Persian heritage. In 1971 he spent $120 million on a lavish parade at the ruins of ancient Persepolis, celebrating 2,500 years of Iranian civilization, and invited foreign dignitaries to attend. Looking back, this spectacle was the high point of his reign--after that his overconfidence and his ruthless suppression of all opposition led to his downfall. In 1975 he introduced the Family Protection Law, which gave women the right to divorce their husbands and the right to challenge a husband's divorce action; again the clergy saw this as an attempt to destroy Islam. Then in 1976 he replaced the Islamic calendar with an Imperial calendar, which counted years from the coronation of Cyrus the Great (see Chapters 4 & 5). Around the same time he started to modernize the shrine of the eighth Imam at Mashhad; even moderate members of the clergy saw the tearing up of the holy place with bulldozers as a terrible desecration, and bombings and vandalism put some of the bulldozers out of action.

The Shah led the way in quadrupling the price of OPEC oil in 1973, but the United States did not protest; on the contrary, Americans were grateful that the Shah kept Iranian oil flowing, when Saudi Arabia launched an oil embargo a few months later. Much of the money came back to the United States anyway, in the form of arms purchases. From 1972 to 1976 the Shah spent $10 billion on American planes, tanks and other weapons; he was the American military-industrial complex's best customer. Nor was that all--these sophisticated gadgets needed skilled technicians to operate and maintain them, meaning that the Shah had to hire nearly twenty-five thousand Americans. Now he was ready to face any threat--except Iranians with rocks and bricks.

What the Shah did not realize was that the people listened more to the voices of the mullahs (clergymen) than to his own decrees and broadcasts. The most vocal opponent among the mullahs was the leading Shiite scholar, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (1902-1989). Originally his last name was Mostafavi, but he later changed it to Khomeini in honor of Khomein, his birthplace. He was only five months old when his father, a senior town cleric, was murdered by highwaymen, so his mother and an elder brother brought him up. At the age of six he started studying theology, and continued to do so for most of his life, finally reaching the top rank of ayatollah ("gift of God") in the 1950s. From the holy city of Qum, Khomeini began to criticize the government as early as 1941. His speeches led to his arrest in 1963, and that caused three days of rioting in many cities; by the time order was restored, 600 had been killed and 2,000 injured. Fearing that Khomeini would become a martyr if he were executed or imprisoned, the Shah exiled him to Turkey in 1964. Khomeini settled in another Shiite holy city, An Najaf in Iraq, and over the next 14 years he kept in touch with his followers by smuggling cassette tapes of his sermons back into Iran. In October 1977 his eldest son was killed, probably by SAVAK agents, so a few months later Khomeini moved again, this time to Paris, France. By now many Iranians viewed him as a legendary figure, the "hidden Imam" who would one day return to lead the Shiite faithful.

Iraq Breaks With the West

In 1948, all of the Arab world except Syria and Lebanon was either under British and French domination, or ruled by conservative monarchies. The strongest and most pro-Western monarchy was in Iraq; there Nuri Said continued to run the country because the crown prince was a minor. As in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Iran, oil revenues grew steadily, especially after Iraq and the Iraq Petroleum Company signed new agreements in 1950 and 1951. Then in 1952, an even more favorable arrangement gave Iraq 50 percent of the profits, instead of a flat royalty for every ton of oil extracted. Instead of simply spending the oil money, the government prudently allocated 70 percent of it to the National Development Board, a bureau established in 1950 to improve the economy, help with flood control and irrigation, and generally repair the damage done to ancient Mesopotamia by centuries of war and neglect. The first parliamentary elections based on direct suffrage took place in January 1953, establishing a constitutional monarchy, and King Faisal II formally assumed the throne on May 2, 1953, his 18th birthday.

The other reason why the Arabs got along with the West at this stage was because the United States had not yet meddled much in Middle East affairs. That began to change when Nasser took charge in Egypt. Britain and the United States grew increasingly alarmed when Nasser refused to side with them against communist expansion, and then began accepting aid from the Soviet Union. As we noted in the previous chapter, American policy makers at the time did not think it was possible to be neutral in the struggle between capitalism and communism, and Egypt held a commanding position in the Arab world with its population and central location, so if it fell to communism, the other Arab nations were likely to follow. And while the Soviet Union had failed to get anything from its meddling in Turkish and Iranian affairs in the late 1940s, it was still interested in the Persian Gulf oilfields and the prospect of gaining a warm-water port, so further attempts to spread Soviet influence into the Middle East were likely.

Accordingly, in 1954 the U.S. government agreed to extend military aid to Iraq. One year later, Iraq concluded the Baghdad Pact, a mutual-security treaty with Turkey. This quickly transformed itself into a Middle Eastern defense system; Britain, Iran and Pakistan joined during the next few months, and the United States agreed to provide arms to all five member states. Since Turkey was a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and Pakistan was in the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), all three of those anticommunist alliances were now linked together. Other Arab countries, especially Jordan and Syria, were invited to join, though none of them did.

This development was furiously denounced by Nasser. Any country that belonged to the Baghdad Pact would remain in the Western orbit, so Egypt thought the organization's purpose was to contain Nasserism as well as communism. Cairo's "Voice of the Arabs" radio station convinced many listeners that cooperation with the West would perpetuate colonialism, while it broadcast anti-colonial messages to black Africa (a Swahili-language program, geared toward the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya, got the British really mad), and threatened any other Arab states that might consider joining the Baghdad Pact.

In February 1958, following a conference between King Faisal II and his cousin, King Hussein of Jordan, Iraq and Jordan were united. The new union, named the Arab Union of Jordan and Iraq, was meant to give the Hashemites enough strength to oppose Nasser's United Arab Republic (U.A.R.), the union of Egypt and Syria that was formed at the same time. The constitution of the newly formed federation was proclaimed simultaneously in Baghdad and Amman on March 19, and in May Nuri Said was named premier of the Arab Union.

The Arab Union, however, was doomed from the start, because many of its citizens regarded Nuri Said's presence as a humiliation. He had never failed to toe the British line, and his dependence on British arms and support caused seething resentment. As a result, the Arab Union fell apart when it was first put to the test. Nuri Said decided to help the Christians in the 1958 Lebanon crisis, and ordered two of his officers, General Abdul Karim Kassem and Colonel Abdul Salam Aref, to lead their troops into Jordan. No doubt the plan was to invade Syria and destroy the United Arab Republic. Instead, Kassem and Aref turned against their master, seizing power in Baghdad on July 14, 1958. Nuri Said, King Faisal, and his uncle the prince-regent, were all killed in a bloody coup, and an Iraqi republic was declared.

Although both Nasser and General Kassem were anti-Western, this didn't mean there was any love between them; the old Egyptian-Mesopotamian rivalry for control of the Middle East prevented Arab unity from becoming a reality. Colonel Aref wanted Iraq to join the United Arab Republic, and Kassem responded by arresting and imprisoning Aref in December. Then came an unsuccessful revolt by pro-Nasser Arabs in Mosul (February 1959), and Kassem allied himself with Iraqi communists. As a result, whenever Nasser visited Syria, he was sure to make a speech attacking both Kassem and the Iraqi communists; this caused a partial cooling of Egypt's relations with the Soviet Union. In March 1959 Iraq withdrew from the Baghdad Pact, which was then renamed the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO).(2)

Kassem's biggest problem did not come from abroad, but from near-constant internal unrest. This was because Iraq contains several ethnic groups: Shiite Arabs in the south (the so-called Marsh Arabs, who live a lifestyle resembling that of the ancient Sumerians), Sunni Arabs in the middle, Kurds and a few Assyrian Christians in the north. The Shiites are the largest group--currently they make up about 65 percent of the population--but ever since the Ottoman Empire conquered Iraq, power has been concentrated in the hands of the Sunnis. The Kurds are Sunnis but not Arabs--they are a mountain-dwelling Indo-European tribe, related to the Iranians. They are spread over a large part of the ancient Fertile Crescent, in lands that now belong to Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria; numbering approximately 26 million, they are the largest ethnic group in the world without a country. Attempts were made after both World Wars to create an independent Kurdistan, but none of the countries in the area would give up land for that purpose. Turkey put down Kurdish revolts in 1925 and 1945, and a Marxist group, the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), has been fighting the Turkish government since 1984. Since 1958 Kurdish nationalists have also been in an on-and-off war against Baghdad.

On February 8, 1963, Kassem was overthrown and shot by a group of officers, most of them members of the Baath Party. Abdul Salam Aref became president, and relations with the Western world improved. Relations also improved with Egypt, and since another group of Baathists had just taken control of Syria, there were now, from Nasser's point of view, five "liberated Arab states": Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and the newly independent Algeria. Even so, this success did not allow Arab unity; later in the year Egypt, Syria and Iraq held talks to create a second United Arab Republic, and they quickly turned into a clash of personalities between Nasser and the Baathists, making agreement impossible. In November 1963 Aref staged another coup, this time expelling the Baath members of his government.

In April 1966 Aref was killed in a helicopter crash, along with two cabinet ministers. His brother, General Abdul Rahman Aref, became the next president, crushed the opposition, and won an indefinite extension of his term in office in 1967. However, the second Aref regime was no more stable than the ones that preceded it, and in July 1968 it was ousted by a Baathist-led junta. Major General Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr was appointed head of the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), but from the start the most visible leader of the council was the vice president, Saddam Hussein (1937-2006). What made the Baath more successful this time was a determination to stay in power, and a more clannish organization: the dominant faction's members all came from Tikrit, a Sunni Arab town on the upper Tigris. In fact Bakr and Hussein were distant relatives, and the defense minister, General Adnan Khayr Allah Talfah, was a cousin of Hussein. As time went on, the RCC and the cabinet was filled with relatives and in-laws of theirs, while the most sensitive military posts went to other Tikritis.

Less than two months after the formation of the Bakr government, a coalition of pro-Nasser elements, Aref supporters, and conservative officers attempted another coup. This event provided the rationale for numerous purges directed by Bakr and Hussein over the next five years; through a series of sham trials, executions, assassinations, and intimidations, the party ruthlessly eliminated anyone suspected of challenging Baath rule. Afterwards the RCC amended the constitution to give the president greater power, and put down roots in Iraqi society by establishing a complex network of grass-roots and intelligence-gathering organizations. Finally, the party established its own militia, the elite Republican Guard, which in 1978 was reported to number close to 50,000 men.

In foreign affairs, Baath-ruled Iraq was hostile to the West and friendly with the Soviet Union. It also maintained Iraq's reputation as the Arab state that would never accept any sort of agreement with Israel. When Jordan expelled the PLO in September 1970, Iraq protested, but its 12,000 troops in Jordan, which had been stationed there since the 1967 war, did nothing; the only outcome was a temporary closing of the border between Jordan and Iraq. Baghdad sent troops and materiel to Syria during the 1973 war, and later denounced the cease-fire that ended that conflict, as well as the disengagements negotiated by Egypt and Syria with Israel in 1974 and 1975.

More serious than any of these disputes, however, were the ones Iraq had with Iran and its own Kurdish community. In 1969, Iran renounced the 1937 treaty which had set the border between them, declaring that Iraq had not fulfilled its treaty obligations. The two countries began to dispute ownership of the Shatt al-Arab, the 100-mile-long waterway formed by the union of the Tigris and the Euphrates; then Iraq aided anti-Shah dissidents, while the Shah renewed support for Kurdish rebels.

As for the Kurdish problem, it looked like it was over when the RCC and the Kurdish leader, Mustafa al-Barzani, agreed to a fifteen-article peace plan in 1970. Barzani's force of 15,000 Kurdish troops were enrolled in the Iraqi army, becoming a border patrol called the Pesh Merga, meaning "Those Who Face Death," and the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) was granted official recognition as the legitimate representative of the Kurdish people. The plan, however, did not resolve the legal status of the area under Kurdish control, and it unraveled in 1974; after a Baath attempt to assassinate Barzani and his son Idris failed, full-scale fighting broke out. Previously, the Kurds had gotten aid from the Soviet Union, but now that the Soviets were helping Iraq, Barzani turned to the Shah of Iran for assistance. Iraqi forces succeeded in pushing the Kurds back to a mountainous strip of territory along the Iranian border, but as long as the Shah gave them military supplies and protected them with Iranian artillery, the Kurdish rebels could hold out indefinitely.

Saddam Hussein resolved this stalemate unexpectedly quickly. In Algiers on March 6, 1975, where the leaders of the OPEC nations were holding a grand conference, he met with the Shah and signed an agreement that restored good relations with Iran, recognized Iran's claim to part of the Shatt al-Arab, and dropped all Iraqi claims to Iranian Khuzestan and to Iranian-held islands in the Gulf. In return, the Shah agreed to prevent subversive elements from crossing the border, meaning an end to Iranian assistance for the Kurds. Almost immediately after the signing of the Algiers Agreement, Iraqi forces went on the offensive against the Pesh Merga; within two weeks, it was all over. Under an amnesty plan, about 70 percent of the Pesh Merga surrendered to the Iraqis. The rest either tried to continue the fight in the hills of Kurdistan, or crossed into Iran to join the civilian refugees (this included Barzani, who died in exile not long after that).

Baghdad also resorted to a "final solution" that would have looked familiar to the kings of ancient Assyria and Babylon; he relocated many Kurds from the Kurdish heartland in the north, introduced Arabs to take their place, and razed all Kurdish villages along a 1,300 kilometer stretch of the border with Iran. Because of this brutal behavior, the Kurds began new attacks, but this time their resistance was strongly hindered by a split. In June 1975, Jalal Talabani formed the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), an organization that was urban-based and more leftist than the tribally-based KDP. Meanwhile, Barzani's sons, Idris and Masud, took control of the KDP; in October 1979, Masud was elected KDP chairman. Although both groups called for more guerrilla warfare against the Baath, they spent almost as much time fighting each other.

The years between 1975 and 1980 were the best time for Iraq in recent history. There was no political opposition to the Baath, the Kurdish rebellion had been crushed for the time being, large new oil reserves were discovered near Baghdad, and the sudden increase of oil prices in 1973 and 1979 brought tremendous wealth. Since Iraq had successfully nationalized the oil industry in the early 1970s, after agreeing to compensate the Iraq Petroleum Company, it no longer had to share the oil money with foreigners. The government used these funds for a state-sponsored industrial modernization program, which distributed both wealth and land, allowed greater social mobility, and improved education and health care. However, it also tied the Iraqi people more closely to the ruling party, by increasing the income of many who had previously opposed the central government. In foreign affairs, Iraq began to take a leading role in the Arab world. In 1975 Iraq established diplomatic relations with Sultan Qabus of Oman and extended several loans to him, while in 1978 it sharply cut back its support for the Marxist regime in South Yemen, a move which improved relations with Saudi Arabia and North Yemen. Most important of all was Iraq's assumption of leadership among the "rejectionist" states, those who opposed the Camp David treaty signed by Egypt and Israel, and punished Egypt for it with sanctions.

The Iranian Revolution

Iran in the late 1970s experienced increasing unrest, accompanied by high unemployment and inflation. By now, the Shah's opposition included not only the clergy, but also former associates of the deposed Mossadegh, members of the middle class who wanted to see true democracy, and anybody else who disliked the growing oppression. In 1977 all of these groups, which had distrusted each other previously, began working together. From the Western point of view, demonstrating students were the most visible opponents of the regime, but they didn't have anyone as charismatic as Khomeini, so 1978 saw the Ayatollah emerge as the leader of the movement whose slogan was "Down with the Shah!"

Ayatollah Khomeini.

The Shah began to lose control of the country in January 1978, when a Tehran newspaper published a letter that directly attacked Khomeini, accusing him of conspiring with the Communists against the Shah. This sparked a pro-Khomeini demonstration in Qum, which quickly turned into a riot, and the police put it down savagely, killing about seventy people. From exile, Khomeini called upon his followers to commemorate the victims on the 40th day after their deaths, in accordance with Iranian mourning customs. In February they held services at mosques throughout the country, and in Tabriz they produced another riot, leading to more deaths. Thus began a vicious cycle; every forty days saw nationwide mourning services, some of which turned violent, more bloodshed resulted each time, and the people grew angrier.

In August, nearly four hundred people were burned to death in a movie theater, in the Persian Gulf port of Abadan; it never was clear whether the blaze had been started by Moslem extremists, who view cinemas as sinful places, or by agents of the Shah seeking to discredit the clergy. Because the army couldn't be everywhere at once, the Shah felt compelled to declare martial law in September. This move only escalated tensions. Twenty thousand dissidents assembled in Tehran to protest the law, and when they refuse to disperse, the Shah's soldiers fired into the crowd, killing more than a hundred. The enraged crowd went on a rampage throughout the capital, with soldiers and helicopters in pursuit. By the end of the day, the massacre had left hundreds dead and thousands wounded. Then employees in various industries and offices began striking to protest martial law, and within six weeks a general strike had paralyzed the economy, including the vital oil sector.

All this time the United States continued to back the Shah. President Jimmy Carter had criticized the Shah's human rights record, but he also saw the besieged monarch as the Middle East's best hope. Until the end of 1978, Washington was certain that the Shah could handle the situation. This made the United States appear as an enemy of Islam, and soon Khomeini and his followers called America the "Great Satan"; consequently, whatever government came after the Shah was likely to be anti-Western.

Because brute force had failed to restore order, the Shah offered compromises, like free elections. Nobody believed him, because in calmer times he had refused to make any concessions. Then he arrested two of his closest associates, General Nematollah Nasiri, the head of the dreaded SAVAK, and Prime Minister Amir Abbas Hoveida. This wasn't taken seriously either, because both had been around the Shah for too long; Nasiri was the one who had delivered the dismissal message to Mossadegh in 1953, while Hoveida had been prime minister for the past fourteen years. Moreover, these arrests disturbed the other loyal henchmen. In November the Shah appointed a military government, but it couldn't make the strikers go back to work, so at the end of December he chose one of his opponents, Shapur Bakhtiar (1915-91), the leader of the National Front Party, to be the prime minister of a new civilian government.

Bakhtiar's revolutionary credentials were immediately voided by his promotion. He had trouble forming a cabinet, because nobody wanted to be seen as associated with the Shah. However, he did release some political prisoners and even disbanded SAVAK. Meanwhile, Khomeini picked Dr. Mehdi Bazargan (Mossadegh's former oil minister) to be his own prime minister. Then he doomed the Bakhtiar government by saying, "Obedience to the Bakhtiar regime is obedience to Satan." When the Bakhtiar government officially took charge, one hundred thousand demonstrators rallied against it. The Shah had played his last card, and he was now sick with cancer, so he packed his bags, announcing that he was going on an extended vacation. On January 16, 1979, the royal family flew out of the country, this time never to return. Back in Tehran, Pahlavi's people celebrated the end of the dictatorship, and waited for Khomeini to establish another dictatorship.

On February 1, Khomeini flew to Tehran in triumph. This revolution, like every other, was decided by which side the armed forces backed, and ten days after Khomeini's return, the army and the revolutionaries worked together to launch a coup. Bakhtiar was forced to flee to Paris, where he was eventually assassinated; Khomeini, using Bazargan as his front man, now ruled Iran.

One of the first things Khomeini did was end Iran's good relations with Israel. When Yasir Arafat came to visit on February 18, the Iranian government closed down the Israeli embassy and gave it to the PLO; Arafat immediately declared that the Iranian revolution had turned the balance of power in the Middle East "upside down." The same day saw the beginning of Khomeini's idea of justice: four generals, including Nasiri, were executed by firing squad. Then the new regime took away the rights of women, forcing them to wear the ancient, baggy chador, instead of Western-style dress, and even outlawed the playing of music.

In March, the Ayatollah moved to his former headquarters at Qum, where he made this vow:

"I will devote the remaining one or two years of my life to reshaping Iran in the image of Mohammed . . . by the purge of every vestige of Western culture from the land. We will amend the newspapers. We will amend the radio, the television, the cinemas-all of these should follow the Islamic pattern.

"What the nation wants is an Islamic republic. Not just a republic, not a democratic republic, not a democratic Islamic republic. Just an Islamic republic. Do not use the word 'democratic.' That is Western and we do not want it."

Not long after that, Khomeini held a national referendum, by non-secret ballot, and faced with either an Islamic republic or a return of the Shah, the Iranian voters overwhelmingly endorsed Khomeini's program. Part of this included making Khomeini the spiritual leader for life, with powers beyond those of any elected officials. Now Khomeini had the mandate to cleanse Iranian society--and to spread Islamic revolutionary influence abroad.

Although the Shah committed his share of atrocities, one should remember that he never killed his chief opponents, Mossadegh and Khomeini. It was a different story, however, for Khomeini and his followers; they called for the death of the Shah's entire family, and the death of anyone who was important under the old regime. Under them, trials consisted of only judges, accusers and defendants, and the judges kept their identities secret to protect themselves. Executions usually followed the trials without much delay, and even then, Khomeini thought it was a sign of Western sickness to try criminals, instead of simply killing them. Former Prime Minister Hoveida was shot on April 7, after a midnight trial held in prison. By May, the revolutionary councils had executed 200 accused SAVAK agents, other officials of the Shah, royalist members of the military, newspapermen, and even businessmen. Then, when the councils ran out of obvious enemies, they went after those they had ignored previously. Death sentences were put on anyone Moslem fundamentalists didn't like: Baha'is, Jews, homosexuals, and women accused of adultery. Sometimes they didn't shoot or hang the condemned, but buried them up to their chests and stoned them to death, thus bringing back another ancient Islamic custom.

In August, the human rights group Amnesty International estimated that the body count had reached 1,000-1,200. By this time, a number of groups formerly allied with Khomeini, both religious and leftist, had begun to resist the regime, feeling that the revolution had gone far enough. In response, the Ayatollah added them to his list of enemies, and continued to speak of holy war against the United States. Like other dictators, he was promoting unity by concentrating Iranian attention on an outside opponent, and soon the wanderings of the Shah gave him a splendid opportunity to humiliate America.

The Hostage Crisis

Long before he went into exile, the Shah had deposited more than a billion dollars in banks outside Iran, and had billions more in investments, including real estate. Thus, he had plenty of money, but was a man without a country. The royal family traveled first to Egypt, then to Morocco, then to the Bahamas, and then to Cuernavaca, Mexico. There the Shah became seriously ill, with advanced jaundice as well as cancer, requiring treatment which was unavailable in Mexico. The Iranian foreign minister warned that letting the Shah into the United States was asking for trouble, but President Carter and several other high-ranking Americans felt that compassion for a sick friend was more important, so they allowed him to be hospitalized in New York.

On November 4, 1979, two weeks after the Shah entered the United States, an angry Iranian mob broke into the US embassy in Tehran and seized more than a hundred people inside, sixty-five of them Americans. The non-Americans were immediately released, but for the freedom of the Americans, the militants demanded that the Shah be returned to Iran for trial and execution.

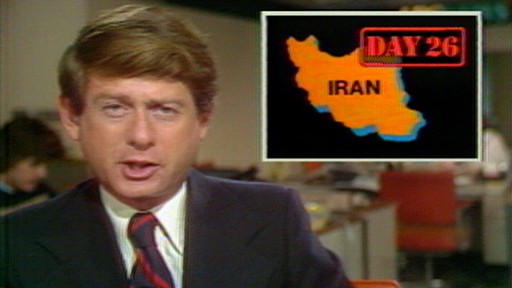

It now appears that the kidnappers only expected to be there 3-5 days before the army or police threw them out; that was the case when the US embassy was briefly captured by another mob in February. Instead, Prime Minister Bazargan resigned, Khomeini approved of their actions, and camera crews encouraged them by filming their activities outside the embassy. Thus, the terrorists, who the Iranian government and press simply called "students," found their action growing beyond their expectations and their ability to control it. Even better for them, the whole United States became hostage to the situation. Every evening on TV, the American media counted the number of days since the crisis began, and showed anti-American demonstrations full of mobs shouting "Death to the Shah!" "Death to America!" "Death to Carter!" Sometimes the militants also burned effigies of Carter, burned the American flag (or used it to carry the trash as they took it out), and paraded the blindfolded hostages outside. President Carter ordered the freezing of Iranian assets in the United States, and the US stopped buying Iranian oil. However, Carter also said that he would use negotiations, rather than military force, to free the hostages, so the militants in the embassy had little to fear.

Ted Koppel counting the days.

Two weeks after the crisis started, the militants released five women and eight black men. This move was both racist and sexist, as they claimed the ones they freed came from the oppressed parts of American society. In February 1980 the Canadian government closed its embassy in Tehran, and brought out with its staff six Americans who had been hiding in the ambassador's house since the crisis started.(3) In July 1980 a vice consul named Richard Queen came down with an illness his kidnappers couldn't diagnose (it turned out to be multiple sclerosis), so they released him too. For the remaining fifty-one Americans, though, it became a grueling 444-day ordeal, full of abuse, torture, beatings and mock executions.

Negotiations got nowhere. First, the Americans weren't really sure who had the most influence in Iran; should they talk with the government, the clergy, or the "students?" Second, nobody in Iran was in a hurry to end the crisis, so it continued even after the 1980 elections chose a moderate, Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, as president. On the first day of 1980 the UN secretary general, Kurt Waldheim, flew to Tehran to work out a solution, but Khomeini refused to meet with him, so he left empty-handed on January 7. As long as the crisis went on, the "students," and Iran as a whole, had the world's attention, and an audience to listen to whatever they had to say. For them it was the next best thing to money in the bank.

That attention was only momentarily diverted by events happening elsewhere, like the Soviet invasion of neighboring Afghanistan. The event that Moslems found most frightening came in late November 1979. On the traditional Islamic calendar, this marked the beginning of the year 1400, and using that turn-of-the-century date, a group of nearly five hundred fanatics captured the Grand Mosque in Mecca, along with three hundred hostages. These gunmen, trained by Cuba and South Yemen and financed by Libya, were from a Moslem extremist sect that opposed the Saudi government; they claimed that their leader, a student named Mohammed al-Quraishi, was the Mahdi. The Saudi response was merciless; a few days later they retook the mosque, killing three hundred fanatics; those who survived were later beheaded.

Although the insurgents in Saudi Arabia were admirers of Khomeini, as far as Iran was concerned, the Grand Mosque affair was an act of revenge by the "Great Satan." Treatment of the US hostages got worse as a result. A Pakistani mob felt the same way, and it burned the US embassy in Pakistan to the ground. Two American servicemen were killed in the fire, and the other fifty people in the embassy only survived because they managed to find an escape hatch.

Carter vacillated in his handling of the situation, regularly backing down from positions where he had previously said the US would stand firm. One of the first was when he abandoned his demand that there would be no negotiations until the hostages were released. This constant shifting only served to keep the crisis in the limelight. Finally in April 1980, he broke diplomatic relations with Iran. Later in the same month, the Iranian government allowed two Red Cross representatives to meet with the prisoners, but not to interview them privately; one newspaper at the time pointed out that the Shah had allowed the Red Cross to interview his prisoners.

On April 25, 1980, Carter announced that the US had attempted an unsuccessful rescue mission. Six C-130 cargo planes and eight Sikorsky RH-53D "Sea Stallion" helicopters had been sent to an abandoned SAVAK airstrip in the Dasht-i-Kavir, the salt desert of northeast Iran. The planes arrived safely, but the helicopters ran into trouble almost as soon as they had taken off from the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz, in the Arabian Sea. One was quickly forced by rotor problems to land in the desert; its crew was picked up by another helicopter. The others encountered sandstorms, and because they lacked dust filters, one suffered instrument failure and had to return to the Nimitz. A third suffered from partial hydraulic failure and thus was no longer fit to fly after it landed at the SAVAK base. This left five choppers, and because the commanders felt a minimum of six was needed for success, the order came down to abort the mission. Then the fiasco turned into a tragedy; with visibility now zero because of the dust, one of the helicopters took off and crashed into a plane, killing eight servicemen. The survivors escaped, but the political damage had been done. Western allies of the US resented that they had not been informed of the mission before it began; Iranians celebrated this humiliation inflicted upon the United States. Despite five months of deadlock, Carter had been doing well in the polls since the hostage crisis started, as Americans rallied behind him. If the mission had succeeded, it could have guaranteed Carter's reelection; now that it failed, his popularity fell steadily. To prevent a second rescue attempt, Iran removed the hostages from the embassy and scattered them in hiding places outside Tehran.

Meanwhile, the person who had started this whole unpleasant business left the United States, when he recovered enough to move again. The Shah went to Panama, then back to Egypt. In Cairo he had more surgery, but died anyway on July 27, 1980. His death did not bring freedom for the hostages, but anger because Iran had lost its chance for revenge. Now the Iranian press perversely declared that Carter had killed the Shah to speed up the hostages' release.(4)

However, when fall arrived, the hostages became more of a burden than a benefit to the Iranians. In September Iraq renounced the 1975 treaty and invaded southwest Iran, giving the Iranians a more immediate enemy than the United States. Some of the students left Tehran to go to the front lines, where they eventually died. In November US elections replaced Jimmy Carter with Ronald Reagan, and though Reagan never spelled out exactly what he would do to free the hostages, everyone expected him to take a tougher stand than Carter did. And the long blackouts in Tehran, coupled with shortages of food and kerosene, showed that the US sanctions were starting to hurt.

Because of this, the Iranian government replaced its original demand with financial ones: the return of the Shah's wealth from American banks, the cancellation of financial claims against Iran, the ending of the freeze on Iranian assets in the United States, and a promise that America would not interfere in Iranian affairs. Negotiations resumed in September, first with West Germany, and later with Algeria, as the go-between. Iran first called for a payment of $24 billion from the frozen assets, and eventually settled for $7.9 billion. Tehran definitely wanted the crisis to end before it would have to deal with Reagan, but it kept the hostages long enough for one more humiliation. They were finally released on January 20, 1981, just hours before Reagan took office; this meant that when Carter got to meet with them, he was an ex-president, his presidency brought down by Iran.

Once the Americans were gone, the Iranian government turned against its own again. President Bani-Sadr, like Bakhtiar, ran afoul of Khomeini and fled to France in July 1981. His successor, Mohammed Ali Raja'i, was a firm follower of the ayatollahs, but two months later he was killed by a bomb planted by anti-Khomeini Mujahideen. In 1982 Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, the foreign minister during the hostage crisis, was accused of plotting to assassinate Khomeini, and executed by firing squad. Like the leaders of previous revolutions (e.g., the French Revolution, the Bolshevik Revolution), the ayatollahs felt a reign of terror was necessary to unite the country behind them, so they could face an outside threat, in this case Iraq.

The Butcher of Baghdad

Officially, Iraq was supposed to be a socialist republic, like most of the Arab states that didn't have a monarch leading the government. However, from 1968 to 2003 it was ruled by one man, Saddam Hussein al-Tikriti, and the closest branch of his own clan. The last time we looked at Iraq, we covered Saddam's activities as vice president. Since he is by far the most important figure in recent Iraqi history, let us look at the rest of Hussein's biography before we continue the narrative.

We already noted that Saddam Hussein was born in the Tigris town of Tikrit. Like many other future dictators, he came from a dysfunctional family. His father went away when he was only a few months old. The official story from Baghdad asserts that the elder Hussein died, but other versions say he deserted Saddam's mother, who soon remarried. His stepfather, Ibrahim Hassan, was cruel to the boy, abusing him physically and mentally, making him work long hours in the fields, and refusing to let him go to school.

Saddam probably would have grown up as just another landless peasant, if he hadn't developed a burning ambition for power, and the will to get it by the most ruthless means possible. At the age of ten, he was packed off to Baghdad, where he would live with his uncle, Khayr Allah Talfah, a participant in the pro-axis coup of 1941 and the father of his future defense minister. As a teenager he tried to enter Baghdad's Military Academy--the path of social advancement Nasser had taken in Egypt--but failed, so in 1956, when he was nineteen, Saddam got involved in revolutionary politics, by joining the Baath Party. One year later he carried out his first political assassination, killing a communist from Tikrit who was a prominent supporter of General Abdul Karim Kassem.

In 1959, he was involved in an attempt to assassinate Kassem himself. Iraqi propaganda describes Saddam at this point as a fearless and effective commando leader, who stitched his own bullet wounds up with his own hand, and covered for his wounded colleagues. As usual, there is another, less glamorous version of the story, which says that he played a very minor role and was hardly injured at all. Whatever version is true, the result was the same; the assassination failed and Hussein fled to Egypt. He stayed there until the Baath seized power in 1963. During the nine months of the first Baath administration, Saddam got a prolonged taste of political violence, and obviously liked it. He became an interrogator and torturer at the infamous "Palace of the End," a former palace in Baghdad which was now converted into a torture chamber. When the Baathists were overthrown in 1964, Saddam was jailed, but managed to escape sometime in 1966. By this time he was a leading member of the Baath Party, guaranteeing for him a place in the Revolutionary Command Council, when the Baath returned to power in 1968.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, poor health and family tragedies hindered President Bakr's ability to work, so he began to turn over power to Saddam Hussein. Soon the party bureaus, the intelligence mechanisms, and even ministers who, according to the constitution, should have reported to Bakr, reported to Saddam instead. Saddam was less inclined than Bakr to share power, viewing the cabinet and the RCC as rubber stamps.

In early 1979 Bakr attempted to end the long-standing feud with Syria's Hafez al-Assad, with an agreement that promised to unite the two Baathist states. If such a union had gone into effect, Assad and Bakr would have shared power, demoting Saddam Hussein to the number three spot. Moreover, some Baathists were talking about electing a replacement for the ailing Bakr, rather than just appointing one. Saddam would have none of these things, so the time for him to take over was now.

He did it by staging his own version of a Stalinist purge. On July 16, 1979, Bakr announced his resignation from the presidency on health grounds. Saddam Hussein put him under house arrest, stripped him of his titles, and took those titles for himself: president of the republic, secretary general of the Baath Party Regional Command, chairman of the RCC, and commander in chief of the armed forces. Later on, it was revealed that Saddam had forced Bakr to resign, and subsequently poisoned him.

A few days later, Saddam invited all RCC members and hundreds of other high-ranking party members to a conference hall in Baghdad. He had a video camera running in the back of the hall, to record the event for the whole nation to see. Wearing his military uniform, he walked slowly to the podium, looking weighted down by sadness. There had been a betrayal, he announced, a Syrian plot. Then Saddam took a seat, and Muhyi Abd al-Hussein Mashhadi, the previous secretary-general of the Command Council, appeared from behind a curtain to confess that he was one of the traitors involved in the failed putsch. He had been secretly arrested and tortured days before; now he spilled out dates, times, and places where the plotters had met. Then he started naming the plotters, and armed guards grabbed the accused and removed them from the hall. When one man shouted that he was innocent, Saddam shouted back, "Itla! Itla!" ("Get out! Get out!"). Once the last of sixty "traitors" was gone, Saddam again took the podium and wiped tears from his eyes, as he repeated the names of those who had betrayed him. Some in the audience, too, were crying, but eventually, one by one, they rose and began clapping. The session ended with cheers and laughter. These 300 "leaders" left the hall shaken, grateful to have avoided the fate of their colleagues.

Weeks later, after secret trials, Saddam had the mouths of the accused taped shut so that they could utter no troublesome last words before their firing squads. Mashhadi's performance didn't spare him; he, too, was executed. By August, more than 400 had been accused of conspiracies and shot, including government officials, military officers, and people turned in by ordinary citizens, who responded to a hotline phone number broadcast on Iraqi TV. Some Council members claimed that Saddam ordered members of the party's inner circle to participate in this bloodbath, turning them into accomplices. Then he covered the walls of Baghdad with 20-foot-high posters of himself, the first example of megalomaniac art that characterized Baath-ruled Iraq.(5) He was 42, absolute master of a country full of petrodollars, and ready to become the leader of the Arabs. There seemed to be nothing he couldn't do.

Saddam Hussein.

The Iran-Iraq War

Saddam Hussein's overconfidence at the beginning of his presidency must have been the main reason why he chose to risk everything in a war with Iran. Another was the mutual dislike Saddam and Ayatollah Khomeini had for one another. Khomeini resented his 1978 expulsion from Iraq, while Saddam saw Iran's Islamic revolution as a dangerous threat to his own secular government. Moreover, it now appears that Saddam was a reluctant signer of the 1975 Algiers agreement; once the Shah was gone he considered it void. Finally, Iran's armed forces were in a shambles after the revolution, with many of its officers dead and its American-made arsenal running short on spare parts, so he must have figured that if he was going to win, it would be now or never.

Iran-Iraq relations deteriorated rapidly in 1980. In April the Iraqi foreign minister, Tariq Aziz, escaped an assassination attempt by Ad Dawah, an Iranian-backed group. The Iraqis immediately rounded up members and supporters of Ad Dawah, and deported to Iran thousands of Iranian-born Shiites; that summer Saddam Hussein ordered the executions of the presumed Ad Dawah leader, Ayatollah Sayyid Muhammad Baqr as-Sadr, and his sister. On September 2, border skirmishes began along the Iran-Iraq frontier, with an exchange of artillery fire by both sides. Saddam Hussein renounced the Algiers agreement on September 17, claiming that Iran had failed to act in good faith, and declared that the entire Shatt al Arab would return to Iraqi sovereignty. In other words, the main reason for the war was a dispute over a 100-yard-wide stretch of river.

Iraq launched a full-scale invasion on September 22, 1980. While one Iraqi mechanized infantry division created a diversion on the central frontier, by overwhelming the border garrison at Qasr-e Shirin and later capturing Mehran, the main force of five divisions invaded the southwestern province of Khuzestan,(6) an area rich in oil and containing an Arab population. Meanwhile, air raids by Iraqi MIG-23s and MIG-21s tried (but failed) to destroy the Iranian air force on the ground. By November the ground units had advanced from the Shatt al Arab to the Karun River, captured the city of Khorramshahr, and put both Abadan and Ahvaz under siege.

Iranian resistance was disorganized, but unexpectedly stiff. Old soldiers from the imperial army were reinstated, the purge trials of officers ended, and President Bani-Sadr authorized the release of pilots who had been imprisoned on charges of being loyal to the Shah. Furthermore, the Iranian army recruited at least 100,000 volunteers, and sent approximately 200,000 soldiers to the front by the end of November 1980. These were ideologically committed troops (some members even carried their own shrouds because they expected martyrdom), motivated by zealous revolutionary guards, and they fought bravely despite inadequate armor support. One Iraqi major in the Khorramshahr area commented that his men were fighting against "fanatics." Meanwhile the United Nations tried unsuccessfully to stop the fighting with a cease-fire; nobody abroad wanted to see two of the biggest oil producers destroy each other's oil wells, refineries and ports.

Details from the war zone were hard to come by. Both sides exaggerated the number of casualties they inflicted, while minimizing their own losses. Iranian and Iraqi reports cancelled each other out as well; when Iraq attacked, Iran denied that Iraq had any success, and vice versa. As it became clear that neither side would win an easy victory, some outside nations started choosing sides. The first third party to declare himself was Jordan's King Hussein; before 1980 was over, he announced that his Red Sea port at Aqaba would be open to Iraqi shipping, and that he would send arms to Iraq if needed. Likewise, most of the Western nations, including the United States, considered Iraq's dictatorship a lesser evil than Iran's theocracy, and began to provide covert aid to Iraq. Saddam Hussein had loosened ties with the Soviet Union in 1979, feeling that he didn't need to toe the Soviet line, but the Soviets were still willing to send arms to Iraq, especially after 1982, because Iran had outlawed the Tudeh Party and executed its leaders. When the tide of war turned against Iraq, most of the other Arabs gave Baghdad their support, viewing Iraq as their first line of defense against an aggressive new Persian empire; even Egypt sent aid, despite its pariah status. Iran had a harder time finding friends, but eventually both Syria and Libya backed it: Syria because its Baathists still disliked their Iraqi counterparts, Libya because Muammar el-Gaddafi found Iran's combination of Islam and anti-Zionism more to his liking. The United Nations tried several times to negotiate a settlement, but both sides simply ignored the UN Security Council resolutions.

Iran launched several counterattacks in 1981; these "human wave" assaults were poorly equipped and carelessly planned, so they failed to recover much ground, but Iraq was put on the defensive for the whole year. On the Iranian home front, a guerilla group called the Peoples' Mujahideen launched a campaign of bombings and shootings in the streets of Tehran and Isfahan, and the ayatollahs responded with another bloodbath when they got the upper hand against these rebels. By the first anniversary of the war, Western analysts estimated that Iran had lost $100 billion in oil income, while Iraq had lost $50 billion. It was the bloodiest war in modern Middle Eastern history, and also the longest, when one considers that the Arab-Israeli conflict involved on-and-off-fighting, rather than constant battles. Moreover, neither side got the "fifth column" support it expected from oppressed brethren on the other side of the border; Iran's three million Khuzestan Arabs did not go over to Iraq, while Iraq's Shiite community did not rise up in revolt against Baghdad.

Israel saw both Iran and Iraq as equally dangerous to its existence, and on June 7, 1981, the Israelis made a daring raid that may have kept the war from getting a lot worse. Iraq was building the Osirak nuclear facility near Baghdad, with French assistance, and intelligence agencies believed that Iraq would use the reactor to produce fuel for nuclear weapons. Israel decided to take out the reactor before it went "hot," so as not to endanger the surrounding community. The target was more than 600 miles from Israel, at the maximum range for Israel's F-15 and F-16 fighters, so every detail of the mission was planned meticulously; the planes were even fueled on the runway, because the amount burned in maneuvering on the taxiways could keep them from having enough fuel to return. Flying low to evade Arab radar, the fighters eventually reached their target, a dome gleaming in the late afternoon sunlight. Enemy defenses were caught by surprise, and they opened fire too late. In one minute and twenty seconds, the reactor lay in ruins.

Needless to say, the world condemned Israel for this air strike. However, we have also seen Saddam Hussein work tirelessly to get weapons of mass destruction, both nuclear and non-nuclear. If he ever succeeds in building or buying an atomic bomb, does anyone doubt his willingness to use it? When a United Nations coalition went to war against Iraq, almost ten years later, some of the soldiers in it must have thanked Israel for making their job easier.

1982 saw the Iranians pursue the initiative they had gained a year earlier. In March Tehran launched Operation Undeniable Victory, which penetrated Iraq's "impenetrable" lines, split Iraq's forces in Khuzestan, and destroyed a large part of three Iraqi divisions. By May they had regained Khorramshahr. Saddam Hussein began looking for a way out of the war, and ordered a withdrawal to the international borders, believing that would make Iran agree to a cease-fire. Instead Iran refused; Khomeini's terms for peace called for Saddam's overthrow and the payment of huge reparations. Then in July came a second Iranian offensive, Operation Ramadan, which brought the Iraqi port of Basra within range of Iranian artillery.

In these offensives Iran again used "human wave" attacks: hordes of eager but poorly trained recruits, ranging in age from only nine to more than fifty. Often they were sent ahead of the regular troops to clear minefields; the children were armed with only Korans and a plastic key to guarantee entry into Paradise if they got killed. As you might expect, they suffered very heavy casualties whenever they met superior Iraqi firepower, but their numbers allowed Iran to recover some territory before the Iraqis could repulse them. Three more "human wave" offensives took place in 1983; this time the Iraqis managed to hold them back, by preparing new defensive strong points and by flooding lowland areas (the so-called "killing zones"). Both sides also experienced difficulties in effectively utilizing their armor.

By 1984, Iran and Iraq were locked into a war of attrition, the likes of which had not been seen since World War I. Both sides heavily fortified their front lines, until they had made movement almost impossible. They even dug in their tanks and used them as defensive artillery pieces, rather than as instruments for offensive maneuvering. Both sides frequently abandoned heavy equipment in the battle zone because they lacked the skilled personnel needed to repair it, and the two armies suffered from little coordination. Soldiers failed to display much initiative, and difficult decisions, which should have had immediate attention, were referred to generals in the capitals instead.

Because Iran had three times as many people, the war of attrition suited the Iranians well, and Khomeini continued to reject offers to negotiate a settlement, figuring that the longer the war dragged on, the better chance he would have of winning. However, few leaders achieve victory by mutual destruction. Meanwhile Iraq looked for ways to use its diplomatic and technical advantages. In February 1984 Iraq began to use chemical weapons; as in World War I, this increased the suffering for the other side, but failed to bring a victory. On the economic front Iraq increased oil production from 600,000 barrels per day (1982) to an amount nearly equal to Iran's daily production of 2,500,000 barrels.(7) In 1985 Iraq began launching air attacks against civilian and industrial targets, rather than just military ones; between August and November, Iraqi planes struck Kharg Island, Iran's main oil port, forty-four times, in an effort to destroy its installations. Finally, the Iraqis were fighting on their home ground, while Iranian morale was beginning to slip; in March 1984, an East European reporter watching a "human wave" claimed that he "saw tens of thousands of children, roped together in groups of about twenty to prevent the fainthearted from deserting, make such an attack."

Iran captured Al Faw, Iraq's southernmost port, in February 1986. Then three offensives were launched against Basra in 1987, all of them failing after suffering heavy losses. In the north, Iranian forces surrounded the garrison at Mawat, with the help of Kurdish rebels, thereby threatening the Kirkuk oilfields. The Iraqis responded with more chemical weapons when they retook Halabjah, a Kurdish town in northeastern Iraq, in March 1988; about 5,000 Kurds were gassed.

Nothing about the war frightened outsiders as much as the danger it posed to the world's oil-driven economy. At this time, approximately 70 percent of Japanese, 50 percent of West European, and 7 percent of American oil imports, came from the Persian Gulf. As early as May 1981, Iraq warned that tankers approaching Iranian ports did so at their own risk. However, civilian shipping was largely left alone until March 1984, when an Iraqi aircraft fired an Exocet missile at a Greek tanker near Kharg Island. Iran retaliated by shelling an Indian freighter in April, and a "tanker war" began. Attacks on neutral ships increased, until Kuwait called for help from nations outside the Persian Gulf zone. Both the United States and the Soviet Union responded, sending naval vessels into the Gulf to escort the Kuwaitis; sometimes the Americans went so far as to "reflag" Kuwaiti tankers, placing an American flag and American crewmen aboard. There was an incident when an Iraqi missile struck the USS Stark, killing thirty-seven Americans, but the US blamed Iran for escalating the war.

The last phase of the war began with a new Iraqi offensive, launched in April 1988. In a thirty-six-hour battle, Iraqi Republican Guard and regular Army units recaptured the Al Faw peninsula. This time the Iraqis combined their forces intelligently, supporting ground units with heliborne and amphibious landings, attacking with fighters, and using more chemical weapons. The next three operations followed a similar pattern; two cleared out the Iranians from the neighborhood of Basra, while the third penetrated deep into northern Iran, capturing huge amounts of armor and artillery. They also began a "War of the Cities," launching 190 missiles at Iranian cities. Because the missiles were not guided, they caused little destruction, but they had a strong psychological effect, boosting Iraqi morale while causing almost 30 percent of Tehran's population to flee the city. The threat that the missiles would have posed if they had carried chemical or biological warheads was enough to make Iran accept a cease-fire on Iraq's terms, and the war ended on August 20, 1988. Ayatollah Khomeini declared that the decision to make peace was forced on him by his colleagues, and it was "more deadly for me than taking poison."

Casualty figures are highly uncertain, though estimates suggest that Iraq suffered 375,000 casualties, while Iranian losses were at least 300,000 killed and 500,000 wounded; the war's financial cost was $500 billion. Virtually none of the issues which caused the war were resolved. The UN-arranged cease-fire merely put an end to the fighting, leaving two isolated states to pursue an arms race, with relations between them as cold as ever.

Iraqnophobia

Because Iraq had successfully defended itself against all Iranian attacks, its army--numbering more than a million men with an arsenal of chemical weapons, extended range Scud missiles, and assisted by a large air force--was now the fourth largest in the world, and the premier armed force in the Middle East. To make this the premier armed force everywhere, Saddam Hussein continued to pursue his nuclear program, and experimented with more weapons of mass destruction. This earned him a cover story in a 1990 issue of US News and World Report as "The Most Dangerous Man In The World." In the same year, news reports surfaced that Iraq was building a "supergun" on its western border, which would be used to fire over Jordan and hit targets in Israel.

Though he did not gain any territory for Iraq, Saddam Hussein declared that he had won a great victory. During the war, when defeat looked likely, he transferred some of his command duties to his generals, and considered democratic reforms like legal opposition parties, a free press, and a private economy. However, he went back to his old habits after the war. He used poison gas to put down a Kurdish uprising, called himself a modern-day version of both Nebuchadnezzar and Saladin(8), and went so far as to claim he was a physical descendant of Mohammed, through the Prophet's daughter Fatima and her husband Ali; the latter caused him to address Jordan's King Hussein as "cousin," though the compliment was not returned. To the other Arab states, he demanded that they cancel Iraq's massive $80 billion foreign debt, because he had singlehandedly saved them all from Iran's Islamic revolution.

This combination of restored confidence and financial troubles caused Saddam to start bullying the small Persian Gulf states. In early 1990 he declared that Kuwait and the U.A.E. were exporting too much oil, and that Iraq was losing a billion dollars a month because of it. Then he claimed that Kuwait was drilling its oil wells diagonally under the Kuwaiti-Iraqi border, so that the oil Kuwait pumped out was really Iraqi oil! While this went on he massed troops along the southern border, but the world was still shocked by his next move; on August 2, 1990, Iraqi forces moved in and occupied Kuwait. In previous years, Iraq had argued that Kuwait really belonged to Iraq, because both had been part of the same province under the Ottoman Empire, so now Saddam annexed Kuwait as Iraq's nineteenth province. The emir of Kuwait, Sheikh Jaber al-Ahmad al-Sabah, fled to Saudi Arabia, and so did two-thirds of the population during the next six months. It was the first international crisis of the post-Cold War era, and the first time one member of the United Nations had completely conquered another member.

The One-Hundred-Hour War

Apparently Saddam Hussein expected the world to recognize his annexation of Kuwait without fighting over it. First he claimed that Iraq was a liberator, acting on behalf of those Kuwaiti democrats who opposed the ruling monarchy. Other nations didn't buy this, and according to those Kuwaitis still in the country, the Iraqi occupation force didn't act anything like "liberators." The Arab League immediately condemned the Iraqi invasion, and the United Nations Security Council imposed an economic embargo that prohibited nearly all trade with Iraq.

Whether or not Iraq planned to conquer any nation besides Kuwait, its armed forces were a standing threat to everybody in the Persian Gulf region, especially Saudi Arabia, which had the largest oil reserves but not enough men to defend them. Within days a frightened King Fahd invited foreign troops into Saudi Arabia, because it now looked like he would be the next target. Here the United States led the way in forming a UN coalition against Iraq, which eventually included units from twenty-nine countries, mostly from the US and Europe, but also Arabs from Syria and Egypt. The equipment brought by the Americans--planes, artillery, missiles, tanks, and other armored vehicles--was decades more advanced than what Iraq had, and the Americans didn't hide these weapons; they wanted Saddam to understand exactly what he was up against. Saddam found himself isolated; the Soviet Union stayed out of the affair, although the USSR protested America's behavior toward its client state. Only Jordan, the PLO, and popular demonstrations from various parts of the Moslem world gave support to the "new Saladin."

Looking back, we can see that Saddam Hussein was a successful dictator but a lousy general. A pre-emptive invasion of Saudi Arabia would have given him control over most of the Persian Gulf's oil supply, put the UN coalition at a great disadvantage, and even if he lost it would have taken much longer for the coalition to get to Iraq. Instead he just sat there for five months, while a force of 600,000 soldiers (2/3 of them American) assembled in Saudi Arabia, a maneuver which the Americans called "Operation Desert Shield." He didn't think they would have much of a chance against his own veteran soldiers, especially the elite Republican Guard, and predicted that any showdown would become "the mother of all battles," with the coalition giving up as soon as it suffered real casualties. To deter coalition attacks, he arrested the foreigners still in Iraq, and tried to use them as "human shields." This didn't work, and outside pressure persuaded him to release the last of the foreign hostages by December. Then he suggested that he might get out of Kuwait if Israel got out of the territories it took in 1967, but this linkage only had much appeal for those Arabs who weren't in the coalition already. To his generals he proposed capturing American soldiers and using them as hostages, by tying them to Iraqi tanks, without explaining how the Iraqis could get close enough to the Americans to capture anybody.

At the end of November, the United Nations Security Council set a deadline: if the Iraqis did not leave Kuwait by January 15, 1991, force would be used to make them leave. Neither Iraq or the United States would back down, so the deadline passed, and the coalition forces launched their attacks on January 17. "Operation Desert Shield" became "Operation Desert Storm."

The coalition offensive began with air assaults, which continued around the clock for six weeks. This was the first war which used cruise missiles and stealth fighters, and they hit their targets with devastating precision. First Iraqi air defenses were obliterated, then coalition planes and missiles worked together to disrupt ground forces and cripple Iraq's infrastructure. In an attempt to pry the coalition apart, Iraq fired Scud missiles at Saudi Arabia and Israel. The attacks on Israel were intended to make it look like coalition members, especially the Egyptians and Syrians, were fighting on the side of Israel.(9) Israeli civilian life was disrupted, but the missiles did not carry chemical warheads, and could not be guided (the technology was about the same as what Germany used in its V-2 rockets, 47 years earlier); out of 39 missile strikes, only four Israelis were killed, one by a direct hit. The United States told Israel not to retaliate, so the Scud missile strategy failed to split the coalition. Iraqi ground forces also initiated a limited amount of ground fighting, occupying the Saudi border town of Khafji on January 30 before being driven back.

By February 24, coalition planes had flown 118,000 missions against Iraq, and the ground offensive began. Two thirds of the coalition troops struck directly into the Iraqi desert from Saudi Arabia, and then wheeled to the right near Basra, surrounding both Kuwait and the Iraqi forces. The rest of the coalition moved up the coast to liberate Kuwait City. Some Iraqi units resisted, but the coalition advanced so quickly that most surrendered or deserted. As Iraq's elite units withdrew from Kuwait, they set oil wells on fire, creating huge oil lakes and thick black smoke; more environmental damage occurred as they let millions of barrels of oil spill into the Gulf.

Four days after the ground war began, Iraq agreed to a UN-imposed cease-fire, thereby preventing the coalition from driving on Baghdad. The coalition broke up at this point, because the only thing all members agreed on was that Kuwait must be liberated, and now that this had been accomplished, many felt that removing Saddam Hussein wasn't necessary. The Arabs, for example, believed the war was fought to restore one Arab country, not to destroy another. An offensive to topple the Iraqi government might split Iraq into three states, since the Kurds and Shiites were now in rebellion, and because the Sunni Arab center of the country didn't have as much oil as the Kurdish north and the Shiite south, a divided Iraq would not come back together easily. Most coalition leaders, including President Bush, must have been aware that leaving Hussein in office would give him a chance to cause more mischief in the future, put they preferred dealing with him than with the unknown devil(s) who might take his place.(10) Thus, the coalition encouraged Kurdish and Shiite uprisings, but did not give them the material support they needed to win. They may have expected the rebels to overthrow Saddam Hussein; instead he suppressed the rebels. After the fighting ended, the UN tried to protect the Kurds and Shiites from more atrocities by imposing "no-fly zones" over most of Iraq; Iraqi planes were not allowed to fly north of latitude 36° or south of latitude 32°.

Almost all of the Persian Gulf War's casualties occurred on the Iraqi side. Western military experts now estimate that Iraq sustained between 20,000 and 35,000 casualties. The coalition losses were extremely light by comparison: 240 were killed, 148 of whom were American. The number of wounded totaled 776, of whom 458 were American. After the war, it turned out that 1/4 of the American casualties were not inflicted by Iraq, but by "friendly fire." The worst case of friendly fire involved the Patriot missiles, the defensive missiles used by the Americans to intercept 99 percent of the Scuds; one Patriot went off course and slammed into a barracks, killing 28 soldiers and wounding about 100. None of the new stealth fighters were lost or even scratched, giving proof to the maxim that "you can't fight what you can't see." Still, in the perverse nature of Middle Eastern politics, Saddam Hussein claimed victory because his regime and the Republican Guards had survived.

The Persian Gulf War.

The Wounded Predator

The UN's economic sanctions against Iraq remained in effect after the Persian Gulf War ended. On April 2, 1991, the Security Council laid out its terms for ending the sanctions: Iraq must accept liability for damages, destroy its missiles, chemical and biological weapons, stop its nuclear program, and accept international inspection to ensure these conditions were met. Iraq has prevented most outside inspections, claiming that it already complied when it withdrew from Kuwait, and that the inspectors from the UN Special Commission on Iraq (UNSCOM) were really American spies. Now Saddam Hussein had two major objectives: (1.) free Iraq of the sanctions, and (2.) build weapons of mass destruction, either nuclear, biological or chemical. Of course the UN wouldn't let him have both; as a result, the sanctions caused severe shortages of food and medicine, resulting in many deaths among the masses, without having much effect on the Tikriti elite. They also cost Iraq an estimated $180 billion in lost oil revenues, and crippled one of the world's most highly valued currencies; an Iraqi 250-dinar note was worth $800 in August 1990, but ten years later it was only worth twelve US cents.

In Kuwait, the prewar regime was restored, and in 1992 the emir honored his pledge in exile to reconvene the country's parliament. The burning oil wells were finally extinguished, though that took until the end of 1991. Palestinian workers in Kuwait, who numbered 400,000 before the war, became scapegoats for collaborating with the Iraqis; most of them were expelled after the war. To take their place, Kuwait hired workers from outside the Middle East, especially Thais and Filipinos, because they were far less likely to get involved in local politics.

Long after the war, thousands of American soldiers suffered from various health problems: abdominal pain, diarrhea, insomnia, short-term memory loss, rashes, headaches, blurred vision, and aching joints. These symptoms are collectively called Gulf War Syndrome, but their cause is unknown. During the war there were no reported cases of Iraq using any chemical or biological weapons, but these symptoms have led many to wonder if the troops had been exposed (possibly by accident) to sarin, a nerve gas, or if their bodies were simply contaminated by all the pollution from Kuwait's blazing oil wells.

Firemen working to put out a Kuwaiti oil well fire.