| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 17: A CONTINENT DIVIDED

1945 to 1990

This chapter covers the following topics:

Due to Lack of Interest, World War III was Canceled

The wartime partnership between the USSR and the other Allied nations had always been an uneasy one. Britain and the United States remembered Joseph Stalin's prewar behavior, and were suspicious of Soviet secrecy; they gave detailed data on strategy and weapons to Moscow, but got little information in return. Stalin didn't trust the West either, and expected the USSR to become the target of a capitalist invasion once the Axis was out of the way. Thus, when an Allied victory became a certainty, East-West relations started unraveling. As early as the Tehran conference (September 1943), Winston Churchill confided to one of his staff that he considered Germany already finished; "the real problem now is Russia." At the February 1945 Yalta Conference, Stalin promised to allow free governments in the nations Soviet troops entered, but afterwards did not do so. On April 1, 1945, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt sent a telegram to Stalin protesting the violation of Yalta pledges.

That was all Roosevelt could do, because of his death eleven days later. In London, Churchill was growing alarmed because as the war wound down, the USSR was much stronger, and the British Empire was weaker, than he had expected. The Red Army had already occupied seven East European countries and part of Austria, so Churchill thought the American decision, to leave all of Germany east of the Elbe River to the Red Army, was a mistake. Indeed, a skirmish was reported at Wismar, the German Baltic port where British and Canadian troops met the Red Army. Churchill could also see what was happening in Poland, where all of the current Polish leaders and partisans were communists; the rest had just disappeared. Obviously, Stalin had his own view on what the postwar world should look like, and it was a different view from that of Roosevelt and Churchill. This prompted Churchill to send a long message of protest to Stalin in May, which concluded with this comment:

"There is not much comfort in looking into a future where you and the countries you dominate . . . are all on one side, and those who rally to the English-speaking nations . . . are on the other . . . their quarrel would tear the world to pieces."(1)

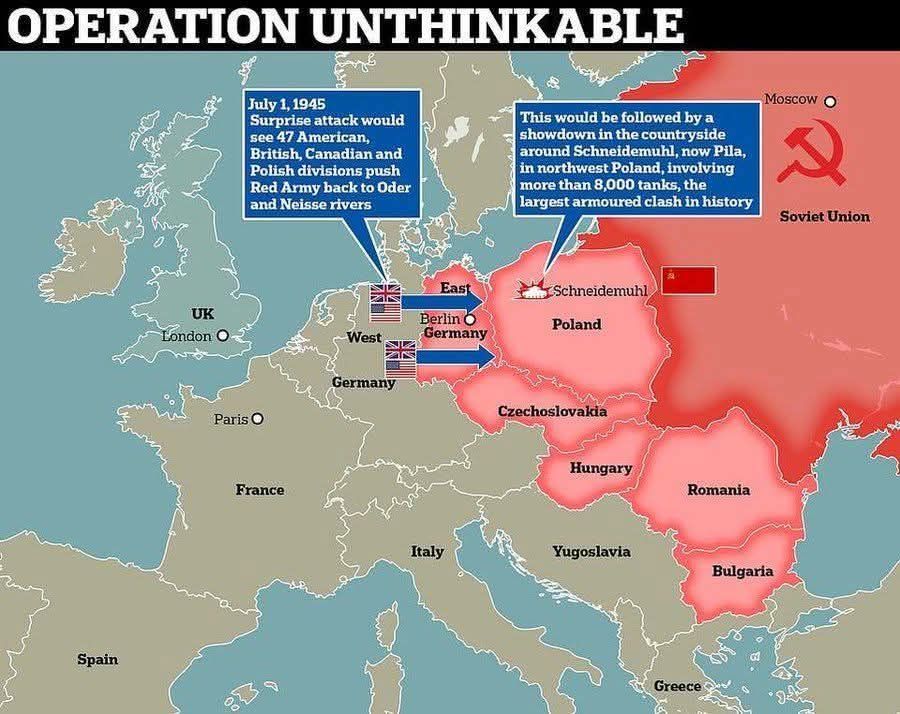

Meanwhile, Churchill ordered Britain's generals to prepare for the next war, immediately after World War II; they should now consider ways to "impose upon Russia the will of the United States and the British Empire" to secure "a square deal for Poland." This meant at a minimum, preemptive strikes on Red Army units in Germany and Poland, and a possible grand offensive to drive the Russians back to the USSR. July 1, 1945 was picked as the earliest date for the operation to begin.

The plan was called "Operation Unthinkable," and that turned out to be an appropriate name, for only Churchill thought it had any chance of succeeding. This was because the Soviet Union had a tremendous military advantage in Europe. In 1945 the Red Army numbered 11 million men, a 4:1 advantage over the troops of the Western Allies (the United States, Britain, France and Canada); Russian tanks also outnumbered Western tanks by 2 to 1, and to top it off, the Russians had more warplanes. To help even the odds, Churchill proposed re-arming 100,000 captured German soldiers, and enlisting them in a new pro-Western army; four Polish divisions were also available. In addition, Churchill knew the United States was researching nuclear weapons, and he figured that using them against the Soviet Union would give the Western Allies the firepower they needed to win.

Churchill's proposed encore to the war that had just ended.

Reality killed the plan before it got off the ground. To start with, Soviet spies informed Stalin that Churchill was up to something, and Stalin alerted his top general, Marshal Georgi Zhukov, so there was no way the attack could take the Soviets by surprise, like Hitler's attack from four years earlier. Second, the British Chiefs of Staff told Churchill that they thought the numbers against them were too great to overcome, and they didn't think the Germans, full of memories of eastern front battles like Stalingrad, would be willing to fight the Russians again. Third, on the other side of the world the United States was fighting the battle of Okinawa, and with a possible invasion of Japan coming up, the Americans didn't want to keep their troops in Europe. As for the nukes, the Americans ended up building three atomic bombs; one was used for the July 16 test at Alamogordo, New Mexico, and the other two were dropped on Japan to make the Japanese surrender without invading their home islands. If any of those bombs had been used against the USSR instead, the Pacific War would not have ended in 1945.

Fourth, the Western generals had their doubts that even atomic bombs dropped on cities like Moscow would stop the Soviets. After all, the Red Army had taken everything the Germans had thrown at it, and like the Incredible Hulk, it came back stronger and more enraged than before. And if the Allies had to invade the USSR to teach the Russians a lesson, they would be up against Russia's formidable natural defenses: winter, wide rivers that are only easy to cross when frozen over, and almost endless tracts of land, much of it mud. Nobody could guarantee that the Allies would fare better against those defenses than Charles XII of Sweden, Napoleon, and Hitler had done.

In all likelihood, if Operation Unthinkable had been launched, the Soviets would have taken their blows until they got a chance to inflict a crushing defeat on the Allies, and then they would charge across the European Continent, at least as far as France. The English Channel would stop them from invading the British Isles, but they could still hit Britain's cities with fearsome bomber and rocket attacks. When the new US president, Harry Truman, heard about the plan, he made it clear that he would not allow American forces to take part in a new war against the Soviet Union. Without the Yanks on his side, even Churchill realized the plan was doomed to fail, and not long after that, he was voted out of office and replaced with a less hawkish prime minister, Clement Atlee. Operation Unthinkable was declared a military secret and filed away; it did not become common knowledge until it was declassified in 1998.

Throughout the period covered by this chapter, people feared that a politician or general would do something that would cause a devastating war between the world's capitalist and communist nations, and that would be the end of Western civilization. Especially if nuclear weapons were used. Well, now we know there was a plan for World War III at the start, but it was immediately rejected as unwinnable, leaving bad East-West feelings that would last throughout the Cold War era.

Back in 1898, when Churchill was a young army officer and a colleague of his was fatally wounded, he said, "War, disguise it as you may, is but a dirty, shoddy business which only a fool would undertake." Nearly half a century later, those same words would apply to himself. He was one of the first to see that nothing good would come from the Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, but now it would be the job of others to do something about it.

Postwar Territorial Changes

The last message received by Berlin's telegraph office before the Red Army captured it was a brief one: "Good luck to you all." It came from Tokyo. Less than four months later, the Japanese also surrendered, and the task of rebuilding a shattered planet began.

Before 1914 there had been nine major powers: the United States, Great Britain, Japan, France, Italy, Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. World War I knocked out the last four nations on the list, but the Germans and Russians managed to recover in the 1930s, bringing the total number back up to seven. Now Germany, Italy and Japan were in ruins. Britain and France were not much better off; both of them had nearly bled to death in the two World Wars. France had lost half its livestock, and Britain, which had been the world's banker before the war, now owed more money than any nation. Neither one could have won without US help, and they had spent too much, in men and resources, to lord over the world the way they had done in the age of imperialism. The land that had once hosted the world's most advanced society saw little beyond starvation and poverty in its future. Winston Churchill put it this way in a 1947 speech: "What is Europe now? A rubble heap, a charnel house, a breeding ground for pestilence and hate."

In the adjustment of frontiers in Europe, the result of the war was obvious: Germany lost and the Soviet Union won. The Germans paid for their defeat twice. First, they lost all of Prussia, Pomerania and Silesia; the Soviets took half of East Prussia, while everything else went to Poland. Second, Germany would be divided for the next 45 years, into a communist East and a capitalist West. Because the Soviets insisted on keeping most of the Polish land they took in 1939, it was as if somebody had picked up Poland, carried it more than a hundred miles west, and put it back down again. Warsaw, for example, was in western Poland before the war, and in the east afterwards. This prompted Churchill to mutter "It would be a pity to stuff the Polish goose so full of German food that it died of indigestion." A wave of name changes followed in the ex-German areas: e.g., Danzig became Gdansk, Konigsberg became Kaliningrad, and Breslau became Wroclaw. Then Stalin changed the ethnic makeup of eastern Europe to fit his new boundaries; in Poland, Czechoslovakia and the USSR, those Germans and Poles caught on the wrong side of the line were deported. He also kept all three Baltic republics, held onto the frontier areas taken from Finland and Romania in 1940, and took Petsamo, Finland's only Arctic port, as punishment for Finland's wartime support of the Germans. On top of that he moved the USSR's border up to Hungary by adding Ruthenia, the tail end of Czechoslovakia. The Western Allies conceded most of these annexations without protesting much, because there were Eastern Slavs like Ukrainians and Belarusians in the areas taken, and because the Soviet Union had suffered so much; two thirds of the European war's casualties, both military and civilian, were Russian.

Poland in the twentieth century. At the end of World War I, the Polish state was given the white territory west of the "Curzon Line." By winning the Russo-Polish War of 1920, the Poles added the grey area to their country. After World War II, the Soviets took back the grey area, and gave Poland the pink areas (Pomerania, Silesia, Danzig and half of East Prussia), which used to belong to Germany. Thus, the white and the pink areas make up Poland today.

Despite all this, the Soviet frontier was usually farther east than the old frontier of the Russian Empire; Stalin didn't hold Finland and central Poland, while the tsars did. In fact, Stalin could claim that what he took was modest, in view of the USSR's past sufferings and present strength. What made a mockery of that statement was the way he made bigger gains by satellite. Eight eastern European countries unfortunate enough to be "liberated" by communists had communist governments imposed on them; their people were blocked from political, economic, and cultural contact with the West. For Stalin this became a four-hundred-mile-deep buffer zone, to protect against any future wars and to provide the USSR with the resources for rebuilding. Only Finland escaped Soviet domination, and Stalin made sure it would be neutral, rather than a pro-Western state. This was the first step in the creation of the Soviet Bloc, a coalition of client states that were treated like Russian colonies.(2)

Because Italy was a minor participant in the destruction (compared to Germany), its losses were less. The Allies assigned the Dodecanese islands to Greece, while Yugoslavia got the port of Zara and all of Istria except Trieste.

Trieste stayed with Italy because it was a disputed city, due to how the Allies captured it. During the last days of World War II, Allied forces raced up the east and west coasts of the Adriatic Sea, with each army trying to reach Trieste before the other one did. Yugoslav partisans, from Josip Broz Tito's Fourth Army, got there first, on May 1, 1945, but following the endgame policy of surrendering to the West, the German troops in the city handed it over to the other unit, which arrived the next day. That unit was the New Zealand 2nd Division, accompanied by British soldiers and Nepalese Gurkhas. Trieste should have been a place for the Allies to celebrate the end of the war before going home, but instead, the first hot battle of the Cold War almost took place here. An uneasy joint military occupation of the city followed, with sporadic clashes between soldiers of the two units. In June 1945 they agreed to a demarcation line between the Yugoslav and British Commonwealth occupation zones, called the Morgan Line. This was followed by a peace treaty between Italy and the Allies, signed on February 10, 1947. According to the treaty, the Adriatic coast, from Duino (Devin) in the north to Cittanova (Novigrad) in the south, became the Free Territory of Trieste, an independent city-state like the "free cities" created after World War I (see Chapter 15). However, the territory never had a government of its own; it continued to be administered by British and American officers in the northern half of the territory, and by Yugoslav officers in the southern half. The United Nations attempted to install a civilian governor, but the Soviet Union rejected twelve candidates nominated for the job, because none of them were communists. Likewise, elections to set up a People's Assembly were never held. Those impasses, and the deterioration of relations between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia in 1948 (see below), delayed a resolution of the affair until 1954. Then in 1954 ministers from all the countries involved signed the London Memorandum, which awarded the area occupied by the British and Americans, including Trieste, to Italy, and gave the Yugoslav-occupied area to Yugoslavia. Still, disagreements continued for the next twenty years over where the Italian-Yugoslav frontier actually ran. To settle this, Italy and Yugoslavia signed another treaty, the Treaty of Osimo, in November 1975, and it became effective in October 1977. When Yugoslavia fell apart in the early 1990s (see the next chapter), the land it got from the treaties was subdivided between Slovenia and Croatia.

The Western Allies took almost nothing for themselves. The United States and Britain realized that the world had changed too much to expect any return to a more innocent, imperialist age. They dismantled the Italian colonial empire in Africa, and the Japanese one in the Pacific, but this time, unlike with the "mandates" set up by the League of Nations, they took their duties seriously; these territories would receive independence as soon as they were ready for it, and they wouldn't be treated like colonies in the meantime. As a result, they let go of most of the ex-Italian and ex-Japanese holdings within a few years. At the time of this writing, only the Northern Marianas are still under foreign rule, and that is because they voted to remain with the United States. France and the Netherlands tried to go back to exploiting their colonies as if it was business as usual; instead they got sharp criticism from the United States, and the natives, now motivated by nationalism, launched armed uprisings that eventually got rid of their overlords (e.g., Indonesia, Vietnam, and Algeria).

The Nuremberg Trials

In a crowded Nuremberg courtroom, twenty-two surviving Nazi leaders went on trial in November 1945, charged with "waging aggressive war" and "crimes against humanity." Presiding over the trial was a panel of judges from the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union and France; they listened as massive documentation was presented, showing that the defendants had plotted both war and the murder of millions. Below is a list of the defendants and the sentences they got:

| Hermann Göring, Luftwaffe commander | Hanging |

| Adm. Karl Doenitz, chief naval commander and Hitler's heir | 10 years |

| Rudolf Hess, deputy to Hitler | Life (committed suicide in 1987) |

| Adm. Erich Raeder, former naval commander | Life (released in 1953) |

| Joachim von Ribbentrop, foreign minister | Hanging |

| Baldur von Schirach, youth leader | 20 years |

| Gen. Wilhelm Keitel, chief of High Command | Hanging |

| S. S. Gen. Fritz Saukel | Hanging |

| Alfred Rosenberg, Nazi theoretician | Hanging |

| Gen. Alfred Jodl, last army chief | Hanging |

| Hans Frank, governor general of Poland | Hanging |

| Franz von Papen, ambassador to Turkey and former vice chancellor | Acquitted |

| Wilhelm Frick, minister of the interior | Hanging |

| Artur von Seyss-Inquart, Commissar for Holland and former governor of Austria | Hanging |

| Julius Streicher, Nazi propagandist | Hanging |

| Albert Speer, chairman of armaments council | 20 years |

| Walther Funk, minister of economics | Life |

| Konstantin von Neurath, protector of Bohemia and Moravia | 15 years |

| Hjalmar Schacht, Reichsbank president | Acquitted |

| Hans Fritzsche, Nazi radio chief | Acquitted |

| Ernst Kaltenbrunner, chief of security police | Hanging |

| Martin Bormann, S. A. chief (tried in absentia) | Hanging |

Those defendants who were not acquitted went to Berlin's Spandau prison. Ten Nazis were hanged in October 1946; Göring, however, cheated the hangman by taking a smuggled dose of poison, just hours before his trip to the gallows. Among those locked up, all but Rudolf Hess were dead or released by 1967. Since the trial, some have questioned whether it is right to try the leaders of a defeated country for war atrocities--because war itself is an atrocity--but in this case most agreed that the defendants got what they deserved. For better or for worse, the Nuremberg trials set a precedent on how to treat those who plan and wage war against others.

Meanwhile, lesser officials were brought to justice. Besides German officers, the Allies went after those citizens who collaborated with the Nazis after their countries had fallen under Hitler's tyranny. In France alone, 100,000 were convicted of collaborating, and 800 were sentenced to death. Marshal Petain got a death sentence at first, but because of his extreme age (he was eighty-nine when the war ended) and his record of heroism in World War I, General de Gaulle changed it to life imprisonment. The real leader of Vichy France, Pierre Laval, went before a firing squad, and so did his Norwegian and Dutch counterparts, Vidkun Quisling and Anton Adrian Mussert. Those French women who fraternized with the enemy got the humiliation of being paraded through the streets with shaven heads. Only after the Europeans put the wartime treachery, shame and executions behind them could they begin to rehabilitate their continent.

There was also the question of what to do with eight million surviving Nazi slaves, who had been put to work in Germany's factories and prison camps. By the end of 1945, five million of them had been sent home, including many Soviet citizens who were forced to return against their wishes ("Operation Keelhaul"). Some of the latter chose suicide rather than return to Stalin's rule.

The Iron Curtain Descends

If you have seen the photos and newsreels from World War II that show civilians welcoming the Allies as liberators, remember that they only did this for the Western Allies. The rejoicing from those "liberated" by the Red Army was subdued, by comparison. Indeed, the Ukrainians probably celebrated more in 1941, when they thought the Germans were freeing them from Stalin, without realizing what could take his place. I put quotation marks around "liberated" because for eastern Europeans, the Soviets were at least as bad as the Nazis. And because the USSR had fought the hardest of any Allied nation, its soldiers thought they could have anything they wanted in eastern Europe, from easily carried objects like watches to whole farms and factories. The first years after the war saw largescale looting wherever Red Army troops were in control; even Europeans who belonged to local Communist Parties could not prevent having their belongings taken away.

Even before the war ended, communists were ruling Albania and Bulgaria, and had driven away all opposition. In 1946 Josip Broz Tito crushed Yugoslavia's monarchists by executing his main rival, Drago Mihailovich. Romania, Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia briefly had coalition governments, but with Soviet troops still garrisoned in all of them, it was clear who was in charge. In June 1947 they helped Romania's communists suppress their coalition partner, the National Peasant Party; King Michael was forced to abdicate and flee the country before the year was over. The process was even quicker in Poland; rigged elections in February 1947 gave 85 percent of the vote to the communists and socialists. Hungary had four parties in its coalition, so the communists used a step-by-step approach to take over the Magyar state. In January 1947 some of the leaders of the Smallholders' Party were charged with conspiring to overthrow the republic and were arrested by the communists; officers suspected of disloyalty to the communists were purged from the army. Elections for a new parliament were held in August. Although the communists won only 22 percent of the votes, they dominated the coalition government, by pressuring the Social Democratic Party to join the Communist Party. A purge of the party in early 1949 made sure that only true communists were in charge, and the next parliamentary elections (May 1949) presented voters a single list of candidates, all communists and their supporters. In August the assembly adopted a constitution, establishing the Hungarian People's Republic.

Czechoslovakia's prewar president, Eduard Beneš, had resigned and left the country in 1938. The Allies recognized him as the head of a Czech government in exile, but he was disgusted with how the Western nations had failed to help Czechoslovakia in its hour of need, so in 1943 he signed a twenty-year treaty of friendship with the Soviets. After the war he returned to Prague and agreed to share power with the communists. In May 1946 national elections were held, and these ones, unlike those in Poland and Hungary, were genuinely fair; Beneš retained the presidency, while the communists gained some key cabinet posts and more than a third of the parliamentary seats. The honeymoon didn't last long after that; communists began assassinating their opponents and packing the police force with their followers. President Beneš, now dying and afraid of a civil war, was blackmailed into resigning by a general strike and the threat of a Soviet invasion (February 1948). In his place came a government that only had one non-Communist member, Jan Masaryk, the son of Czechoslovakia's founder, Thomas Masaryk. Shortly after that, Masaryk fell out of a window, and his death was officially declared a suicide. Now that the communists had all of eastern Europe, they introduced the same tools of repression that Stalin had perfected in the Soviet Union: political purges, massive economic planning, the jailing of political and cultural opponents, etc.

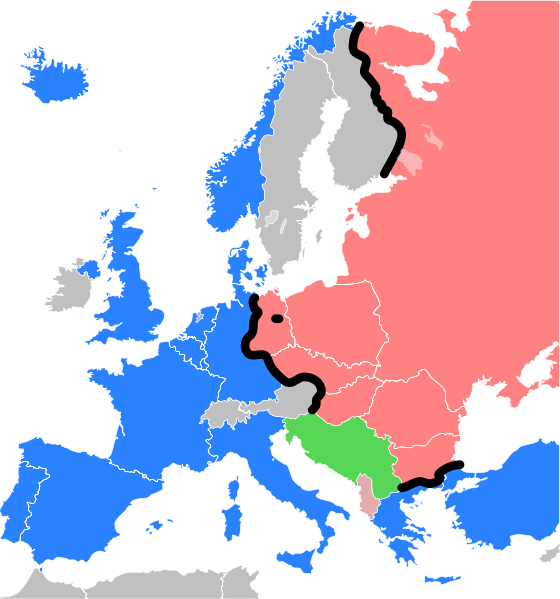

The expansion of communism beyond the USSR was a departure from Stalin's old policy, which called for "socialism in one country." Now the missionary zeal of the Marxists alarmed the West. Churchill gave a name to the new barrier between East and West in 1946. Making a speech at a college in Fulton, Missouri, the former prime minister declared that "From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent." To Churchill only the combined strength of the democracies could stop communism, for the Russians respected might, "and there is nothing for which they have less respect than for weakness, especially military weakness." This speech shocked those who didn't want to offend the Soviet Union, but soon various events, from Berlin to Korea, would prove Churchill had been right again. The West had trouble understanding the new war of nerves, soon to be called the Cold War, as well as the unconventional weapons of the other side; the communists preferred to use guerrillas and political chaos to advance their goals, since both are so much harder to watch and control than tanks, planes and soldiers. Nevertheless, the democracies would have to fight this conflict, or they would lose the whole world to communism.

An American diplomat, George F. Kennan, formulated the policy the West adopted in dealing with the Soviet Union, "containment." In an article entitled "The Sources of Soviet Conduct," written under the byline of "Mr. X" in the July 1947 issue of Foreign Affairs, Kennan proposed a "realistic understanding of the profound and deep-rooted difference between the United States and the Soviet Union" and the exercise of "a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies."(3) Rather than denounce the USSR for its behavior, as so many others had done, Kennan called for making the current situation a stalemate; the US could and should prevent the spread of communism to any more countries, but it must not try to remove the communist regimes that already existed. The Soviets would see an anticommunist counteroffensive as a threat to them, and that would be enough to trigger the big war which Kennan wanted to avoid most of all. On the surface, containment resembles the policy of appeasement that failed to prevent World War II; this time it worked because both the US and the USSR had nuclear weapons by 1949, and they believed that using these arms would destroy the human race. When the Soviet empire finally fell, it collapsed on its own, without a push from outside.

Europe during the Cold War years, divided by the Iron Curtain (black line) into a capitalist West (blue) and a communist East (pink). Yugoslavia (green) and Albania (striped) were also communist, but for most of this period they were not part of the Soviet Bloc; read on to find out what happened to them.

The Marshall Plan

Before Churchill made his warning, communists began exploiting western European weaknesses. Because communist guerrillas had been very successful in the wartime Underground, they were now as strong as the official governments of France, Italy and Greece. Their political leaders, Jacques Duclos of France and Palmiro Togliatti of Italy, stood a good chance of getting elected to public office. In Greece, more than 25,000 guerrillas roamed the country at will, waging a war against what they called the "monarcho-fascists." Albania, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria (though not the USSR) supported the guerrillas, while Britain tried to help the restored Greek monarchy. However, the effort was too much for the cash-strapped British, and in February 1947 Britain informed the United States that it would be withdrawing all financial and military support from Greece by April 1. The Americans stepped in by announcing the Truman Doctrine in March; to contain communism, President Truman pledged $400 million in aid for Greece and Turkey (Turkey was also under strong communist pressure).

Before long Truman had also authorized massive assistance for the rest of western Europe. Secretary of State George C. Marshall proposed a plan of economic aid to help Europe to solve its postwar financial problems. Congress authorized the plan, officially called the European Recovery Program but better known as the Marshall Plan. Sixteen nations, with a combined population of 270 million people, eagerly accepted the aid, and $23 billion poured across the Atlantic between 1947 and 1952, compared with $15 billion before 1947. The Marshall Plan also offered aid to eastern Europe, but Stalin rejected it, because each country that received aid had to open up its economy to American financial planners, and he wasn't going to allow anything that would make him dependent on the United States. In the end Czechoslovakia was the only satellite to ask for Marshall Plan funding, and the 1948 coup in Prague made sure that the Czechs wouldn't get any money. In western Europe, the plan was a complete success; the risk of starvation was gone by the end of 1948, and by the mid-1950s every nation west of the Iron Curtain was fully recovered. Equally important, the danger of communism began to fade. Only in Portugal during the mid-1970s did the communists come close to taking over any western European nation. Some communists tried extreme measures; the Red Brigades in Italy and the Baader-Meinhof gang in West Germany resorted to terrorism. Incidents they caused, like the assassination of Italian prime minister Aldo Moro (1978), got them worldwide attention, but they failed to win popular support; by the late 1980s both groups had lost so many members that they were no longer relevant.

Occupied Germany and the Berlin Airlift

Few nations have been destroyed as thoroughly as Nazi Germany. Every city had been bombed out, and whereas Kaiser Wilhelm's German Empire surrendered before any Allied soldiers set foot on German soil, most of the Third Reich, true to Hitler's last wishes, had fought to the end. Much of the population was homeless, and the infrastructure no longer existed. In some areas, adults could only find enough food for a diet of 700 calories per day, one sixth the ration of American soldiers. Many felt that the end of civilization had arrived, and spoke of stunde null, the zero hour.

To rebuild central Europe and prevent the establishment of a new government bent on revenge, the Allies divided both Germany and Austria into four zones of occupation. Since Austria was no longer important, the "Big Four" agreed to a treaty that made Austria a neutral nation, and they withdrew from that country in 1955. It was not so easy in Germany, though. There the Americans got Bavaria and Hesse, the French took Baden-Württemberg and most of the Rhineland, the British administered the northwest (Westphalia, Hanover and Schleswig-Holstein), and the east (old Brandenburg and Saxony) went to the Soviets. Berlin was deep in the Soviet zone, but because it was the capital, it was also split into British, American, French and Soviet sectors.

Occupied Germany and Austria.

The last conference between the American, British and Soviet leaders (held at Potsdam, July 1945) failed to reach an agreement on what form postwar Germany should take; the USSR demanded $10 billion in reparations, while the West wanted to rebuild Germany as a Western-style democracy, so each side developed its own version of Germany. The Western Allies went ahead with their own plan, merging their zones first economically, and then politically. Stalin responded in June 1948 by blocking all access by land and water to the part of Berlin he did not control, now called West Berlin. He thought this would starve the 2,250,000 residents of West Berlin, many of them refugees from Soviet-ruled districts. Instead of giving in, the West launched a massive airlift called "Operation Vittles," which brought food, fuel, and all other supplies. Since the main cargo plane available, the American C-47, carried just three tons, they had to fly in and out of West Berlin's Templehof Airfield constantly. At the peak of the Berlin Airlift, a plane landed almost every minute, and together they brought in 13,000 tons of supplies a day. The pilots became heroes to the Berliners, especially the "candy bombers" who dropped treats to the children. More than 70 Allied pilots died in crashes; Stalin kept up the blockade for eleven months because he remembered how a German airlift during the war had failed to save the army trapped in Stalingrad. This time he was wrong; on May 12, 1949, the Russians conceded defeat and reopened the roads to Berlin to Western traffic.

In the spring of 1949 Washington established the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a permanent military alliance. The first members were the United States, Canada, Iceland, and nine nations of western Europe. Greece and Turkey joined in 1952, followed by West Germany in 1955. The purpose of NATO, as its first secretary-general put it, was to keep "the Soviets out, the Americans in and the Germans down." It succeeded marvelously in all three, and became the model for other alliances that the United States formed during the next few years: SEATO and ANZUS in the Pacific, CENTO in the Middle East, and the OAS in Latin America. In response the Soviets created the Warsaw Pact in 1955, which formalized the stationing of Red Army units in eastern Europe. This alliance, which included every satellite state of the USSR, lasted until 1991.

Yugoslavia Breaks With Moscow

While Stalin suffered a setback with the Berlin Airlift, Yugoslavia handed him a much more embarrassing defeat. As we noted before, Yugoslavia had liberated itself from the Nazis with only a little help from the USSR. In the immediate postwar years, Tito ran Yugoslavia his own way, not Stalin's way, and he went so far as to open up negotiations with his Bulgarian counterpart, Georgi Dimitrov, to talk about uniting Yugoslavia and Bulgaria into a single nation for all Slavs in the Balkans. Stalin could not trust a foreign leader as self-reliant as Marshal Tito, so he tried to gain control over the Yugoslav economy, armed forces, and party apparatus with Soviet agents. Tito, who had been a devoted Stalinist to this point, resisted by canceling ruinous economic contracts and by deporting the Soviet agents, knowing he was fighting for his career, and probably his life. At the beginning of 1948, Stalin "invited" both Dimitrov and Tito to meet with him in Moscow. As Stalin's most loyal follower in Europe, Dimitrov went, but Tito (probably suspecting that he would not come back if he went) sent a representative in his place. Furious, Stalin condemned the Yugoslav communists as "deviationists" and "traitors," expelled Yugoslavia from his international communist organization (the Cominform), and called upon the armies of Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Albania to prepare for an invasion. But Tito used Stalin's own tactics against him; his totalitarian controls, combined with patriotic and anti-Russian feelings, quickly brought the whole country behind him. The United States promptly forgave Tito of his pre-1948 political sins and gave him the economic aid he needed to get his country through the hardest days.

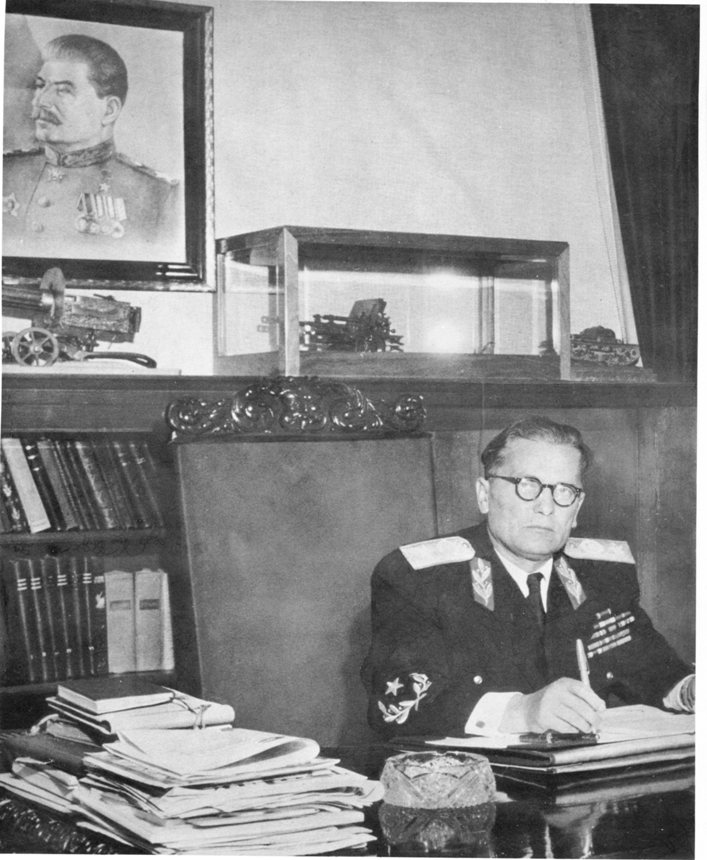

Before their falling out, Tito kept a portrait of Stalin on the wall behind his deak.

Stalin had expected Tito to quickly crumble without Soviet support, bragging that: "I only need to wag my little finger and Tito and his clique will vanish!" And he did wag; between 1948 and his death in 1953, Stalin tried no less than twenty-two times to assassinate Tito. But Tito was a veteran of two World Wars, so people trying to kill him were nothing new. Eventually, Tito responded by writing a letter to Stalin that said:

"Stop sending people to kill me. We've already captured five of them, one of them with a bomb and another with a rifle . . . If you don't stop sending killers, I'll send one to Moscow, and I won't have to send a second."

--Josip Broz Tito

Stalin kept the letter on his desk for the rest of his life, leading to a theory that he was still plotting to kill Tito, but Tito got him first (well maybe, there is also this theory). Very few people ever defied Stalin and survived; Tito was one of them (the other was Harry Truman, and Truman had the atomic bomb). In fact, Tito outlived Stalin by twenty-seven years, now a respectable Third World statesman and living proof that one could be a communist and not a Stalinist at the same time.

Incidentally, the break between Tito and Stalin also brought an end to the Greek communist guerrillas, because the three countries that backed them were now too busy watching each other to advance the cause of revolution anywhere else.

The Postwar Leaders of Western Europe

By 1949 every country of western Europe had a parliamentary system, and only Spain and Portugal remained under fascist rule; the rest were democracies. Because the United States paid most of the defense bill for its allies, Europe's postwar politicians could be conservative in their foreign policy, but liberal in spending at home. The chief political party in Italy and Germany was called the Christian Democrat Party, and France's equivalent, the Mouvement Républicain Populaire (MRP), was also influenced by the Catholic Church.

Italy's King Victor Emmanuel III abdicated in May 1946, and when a plebiscite abolished the monarchy, his son Humbert soon followed him into exile. The prime minister who replaced both king and dictator was Alcide de Gasperi (1881-1954), a veteran nationalist. Born in the south Tyrol when Austria ruled it, de Gasperi started his career by campaigning for the liberation of Italia Irridenta. Mussolini imprisoned him from 1926 to 1929, and then he spent the rest of the Mussolini years as a librarian in the Vatican. When he took charge he discarded the Communists, who had been coalition partners, and encouraged a free-enterprise economy. His "government of rebirth and salvation" was unstable, and he had to reshuffle cabinet members eight times before he retired in 1953, but he succeeded in making sure Italy would be one of the most prosperous nations of the late twentieth century. Italy's presence in the "G-7" group of nations is the legacy of de Gasperi today, though Italy's political system remains more chaotic than that of its neighbors.

Alcide de Gasperi, on a 1953 Time Magazine cover.

In Germany the American, British and French zones became the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) in 1949, with its capital at Bonn. The elections that followed chose Konrad Adenauer (1876-1967), the Christian Democrat Party's leader, as the first chancellor. Adenauer had been mayor of Cologne under the Weimar Republic, and was jailed by the Nazis; at the age of seventy-three, he was already an elder statesman. He predicted that poor health would force him to retire in two years, but as it turned out, he stayed in office until 1963. Abroad, he cultivated good relations with France and the United States, rather than with East Germany. At home his administration succeeded in everything he considered important, and West Germany played a leading role in the creation of the Common Market, which Adenauer saw as an important step toward uniting the continent. Most of all, his presence reassured many Europeans that the new Germany would be peaceful; in this grandfather-type figure nobody could see another Kaiser or a Hitler.

Konrad Adenauer.

Adenauer was succeeded by two more Christian Democrats, Ludwig Erhard (1963-66) and Kurt Georg Kiesinger (1966-69). Then the Social Democrats came to power, under Willy Brandt (1969-74) and Helmut Schmidt (1974-82). Conservative sentiments in the 1980s allowed the Christian Democrats to regain control; their chancellor, Helmut Kohl, has so far held office longer than anyone else (1982-98), and he oversaw the reunification of Germany.

West Germany's industry recovered at a speed that astonished even the Germans; they called it the Wirtschaftswunder, the "economic miracle." Helping it were a total overhaul of the currency, a large supply of trained workers, an avoidance of the strikes and labor unrest that disrupted other countries, and as we noted, the fact that the West Germans did not have to pay for their armed forces until 1955. They even made a profit from the Korean War, by increasing steel production during that time. Before the 1950s had ended, West Germany's economy became the strongest in western Europe. The miracle ended with a major recession in 1966, followed by the oil crisis of 1973, allowing Britain, France and Italy to catch up. In the 1980s the average growth rate was 1.6 percent a year. This was less than half of what it had been previously, but still ahead of the stagnating economies to the east.

France was under martial law immediately after liberation; Charles de Gaulle stepped down in 1946 so that a civilian government, the Fourth Republic, could take charge. During the Fourth Republic's twelve-year existence, it saw even less stability than Italy; twenty governments rose and fell, while de Gaulle, still the country's most capable leader, watched from the sidelines. Before the war, American humorist Will Rogers had joked that American tourists go to London to watch the changing of the guard, and then they go to Paris to watch the changing of the government; this was even more true of postwar France (and Italy). What finally brought the Republic down was its insistence on fighting two wars it could not win, to keep France's colonial empire; each lasted for eight years and drained the country's wealth and manpower. The first, in Vietnam, ended in a humiliating defeat, when the Vietnamese communists besieged and captured Dienbienphu (1954). The second, in Algeria, became the "grave of the Fourth Republic." Paris freely gave independence to neighboring Morocco and Tunisia, but French colonists insisted that the Tricolor remain over Algeria forever, so fighting erupted here only four months after the fighting ended in Vietnam. The corrupt colonial regime pursued a campaign of terror against Algerian natives, and the army ignored the directives issued from Paris. Despite this, the French were not any closer to winning, and in May 1958 the war caused the government to disintegrate. Militant army officers and European civilians, fearful that Paris was preparing to talk with the rebels, seized control of Algiers; the army supported them, and a military coup in France looked likely. The National Assembly was forced to call de Gaulle out of retirement, and it voted him almost dictatorial powers, to govern the country for six months and to prepare a new constitution.

De Gaulle submitted his constitution to a plebiscite in September 1958, and the voters gave it a 79 percent approval rating, an overwhelming vote of confidence for the author. Thus, de Gaulle became the first president of the Fifth Republic. He promised that, "There will be no Dienbienphu in Algeria," but that meant he would negotiate a peaceful settlement, whereas his supporters expected him to push for an ultimate victory. In 1960 he began peace talks with the Algerian rebels, and--undeterred by revolts of army officers in Algeria, assassination attempts against himself, and by terrorist violence--he pursued these negotiations until they reached an agreement granting independence. In an April 1962 referendum, 90 percent of the voters approved. At any rate, Algeria's one and a quarter million French residents had given de Gaulle more headaches than nine million Algerians.

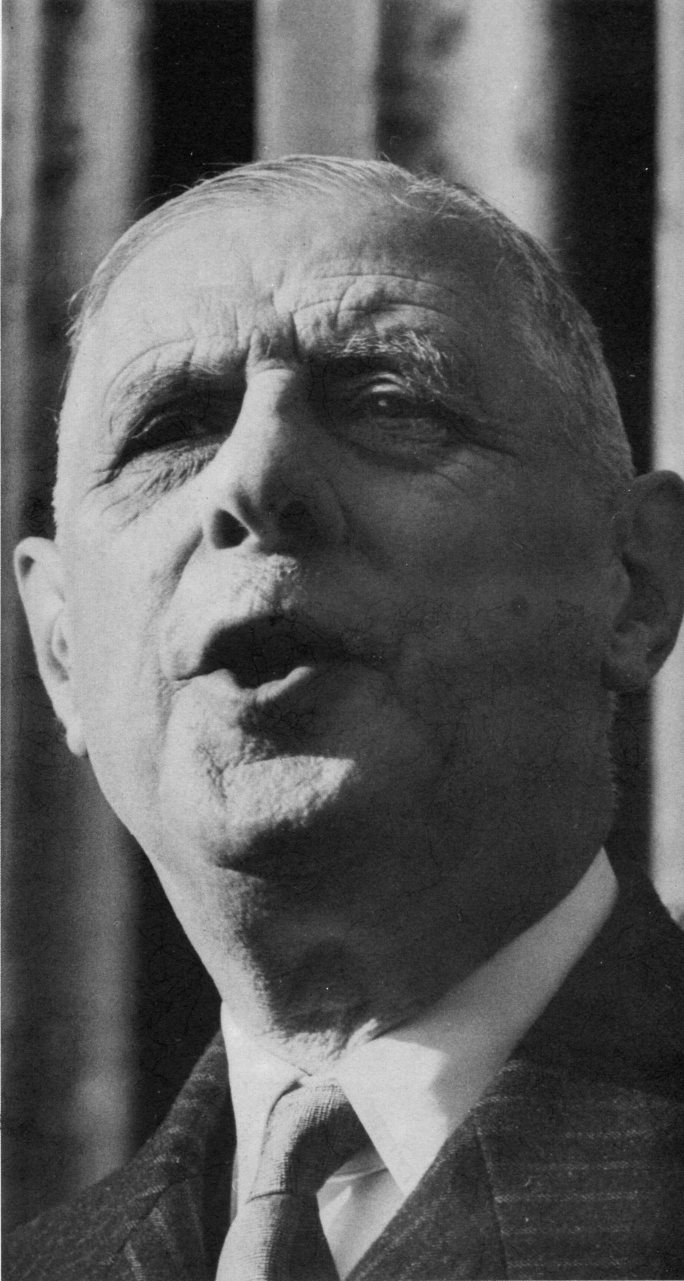

President Charles de Gaulle.

For de Gaulle, the most important task was to restore France as a first-class power. However, the French had learned the hard way that the age of colonialism was over, so he gave the rest of the French empire (most of it in Africa) the choice of staying or leaving. Most of the colonies chose independence; by the time de Gaulle pulled out of Algeria, only a few choice islands and coastal enclaves were left. Therefore, he worked instead to make France the most important nation in continental Europe; because of him, France played a major role in the Common Market and all other activities that involved more than one western European nation. He got along well with Konrad Adenauer, and together they ended the century-old rivalry that had caused three bitter wars between France and Germany. At the same time, he cooled relations with the United States, declaring that: "We will never descend to the level of American vassals." In 1966 he removed the French armed forces from NATO, making France a nonparticipating member of that organization, and developed a French atomic bomb to further reduce the need for American protection. As far as de Gaulle was concerned, the British were little more than American agents, so in 1963 he vetoed the first effort to bring the United Kingdom into the Common Market. Despite all this, he was a nationalist first, not anti-American or anti-British as much as he was pro-France.

France saw considerable economic growth during the de Gaulle years, but also inflation and rising unemployment. A surplus of university graduates found no suitable jobs for them as they left school; having grown up in an age of affluence, they found themselves in an unrewarding consumer society. In 1968 this led to widespread student revolts, like the strikes and demonstrations that shook other Western nations at that time. The government's efforts to end it by persuasion and concession failed, and de Gaulle called for new elections. The voters, fearful of growing disorder, gave de Gaulle's party an absolute majority in the new assembly. De Gaulle, however, felt the need for additional endorsement of his presidency, so in 1969 he announced a referendum on two constitutional reforms and declared that he would resign if the voters rejected his proposals. 53 percent of the electorate voted against them, so de Gaulle resigned, and died a year later.

France has seen seven presidents since de Gaulle: Georges Pompidou (1969-74), Valery Giscard d'Estaing (1974-81), François Mitterand (1981-95), Jacques Chirac (1995-2007), Nicolas Sarkozy (2007-12), François Hollande (2012-17), and Emmanuel Macron (2017-). Mitterand and Hollande were socialists, while the rest were center-right "Gaullists." All of them have promoted European unity, independence from the superpowers, and a strong economy; even under Mitterand the confrontation many expected between government and business never took place.

Britain started the postwar era with a head start; its factories had suffered less damage than those on the Continent, and the Allied victory had apparently proven that democracy was the best kind of government. Nevertheless, the United Kingdom failed to keep ahead of the recovering states. It may have won the war, but it had lost a fourth of its net wealth. Instead of collecting reparations from its defeated enemies, Britain was helping them get back on their feet, because having their support against communism was now more important than any punishment. The British found it especially galling when they had to send aid to Germany, to prevent mass starvation during the winter of 1946, and it was no accident that the Americans gave more assistance to Germany and Italy than to their allies. Over the next twenty years Britain managed a growth rate of 2.5 percent a year, but this was far less than France and Germany's. An inflation rate of 20% and a poorly organized industry caused even more trouble, requiring a major loan from the International Monetary Fund in the 1970s and a vigorous overhauling of the economy while Margaret Thatcher was prime minister (1979-90). Instead of dominating the Continent, Britons gave most of their attention to domestic matters.

The British Empire disintegrated in a single generation. During and immediately after World War II, the Americans made it clear that their vision for the future called for a world government, namely the United Nations, but it had no place for any empire, including Britain's. And there was considerable nationalist activity in the colonies before the war, so Britain had to make concessions (like independence for India) to keep the nationalists on their side throughout the war years. Afterwards Britain honored its agreement, and let India go in 1947. Once this happened it didn't have the resources to hold on to the rest of its empire, and many Britons thought colonies had lost their relevance anyway, so the British empire became the first in history to give itself away. By 1970 the only colonies left were little ones in places that saw British rule as better than the alternatives, and Britain turned these loose once the natives changed their minds. In 1982 Argentina seized South Georgia and the Falkland Islands, causing a brief war that Britain won easily; the English-speaking inhabitants of those islands never wanted to be under Argentine rule. Hong Kong went back to China in 1997, leaving a small list of places where the Union Jack still flies: Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Turks & Caicos Islands, Anguilla, British Virgin Islands, Montserrat, Falkland Islands, South Georgia & the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory, St. Helena, Ascension Island, Tristan da Cunha, Gibraltar, the British Indian Ocean Territory, and Pitcairn Island. Between them these outposts have only 200,000 people, and nearly half of those residents live on Bermuda and the Cayman Islands, places best known for beautiful beaches and loose financial regulations. Most of them are too small to find independence attractive, since it would mean giving up the money London sends them every year to keep their economies afloat. At this point one could say that the sun still never sets on penguins and volcanoes!

Unrest in the Soviet Empire

In each nation of eastern Europe, communism brought heavy-handed state planning, a near-total loss of political and religious freedom, and an economy that was static and inefficient compared to the capitalist West. In previous chapters we noted how governments can mobilize their people to take part in impressive projects, but in the long run the gains (especially in science and per capita income) are greatest when individuals are left alone. By contrast, the societies of the socialist/communist world saw little creativity and little choice; store shelves would have only one brand of a given product, if they weren't completely bare. Staples we take for granted, like meat and eggs, were in such short supply that consumers would wait in line for hours to buy them. Moreover, the state showed no concern for the environment, so industrial pollution ran rampant, turning every communist state into a biohazard. West Germans pointed out that even the birds no longer stopped in East Germany when they migrated; they flew out while the people were forced to stay.

After Yugoslavia left the Soviet Bloc, most of the other satellite states remained loyal, but only Bulgaria gave Stalin and his immediate successors, Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev, the cooperation they wanted; the others saw unrest, and sometimes revolts, at one time or another. Here is a capsule description of how they behaved during the Cold War era:

Albania

If there was a true tyrant among eastern Europe's strongmen, it was Albania's Enver Hoxha (pronounced "Haw-Jah"). He got rid of malaria, and dramatically increased literacy and the role of women in society, but otherwise he transformed Albania into a state so totalitarian that even the USSR looked democratic by comparison.(4) By the time he was done, Hoxha resembled Big Brother, the ultimate dictator in George Orwell's 1984. Hoxha also isolated Albania from the rest of the world; very few outsiders were allowed in, and only party members could leave. The Soviet Union persecuted religious organizations, but was willing to recognize their existence; by contrast, Hoxha eradicated all religions, and declared Albania the first truly atheist country. Society was so regimented that ordinary people could not own a car, a permit was required to own a refrigerator or typewriter, singing was not allowed in public, and neither citizens nor visiting foreigners could have beards (The government reasoned that anyone with a beard was either a Moslem or a hippie, and wanted nothing to do with either. I don't know how they explained pictures of Marx and Lenin, though.). The countryside was turned into an armed camp, full of bunkers and concrete pillboxes to deter potential invaders, which in Hoxha's book included just about everybody.

The religious issue and the USSR's de-Stalinization (Hoxha was a devout Stalinist) prompted Albania to break with the Soviet Union in 1961. Since Albania was not adjacent to any Soviet Bloc state, it was able to get away with this, unlike Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The break in relations between China and the Soviet Union occurred around the same time, so Albania sided with China, seeing Mao Zedong's brand of communism as purer than that of the Russians; in return, China replaced the USSR as a major supplier of trade and economic aid. Then in 1978, Albania broke with China as well, denouncing China's abandonment of Maoism and the normalization of relations between China and the United States. After that Albania went alone for the next few years, despite a declining economy.

Because of Hoxha's tight grip on the country, and because he wrote more than sixty books telling everyone how great he was, the only opposition came from within the ruling party. In 1981 Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu died under mysterious circumstances; officially it was declared a suicide, but many suspect he tried unsuccessfully to unseat Hoxha. When Hoxha died in 1985, he was succeeded by Ramiz Alia; still, there was hardly any loosening of the regime's absolute rule until 1990.

Enver Hoxha.

Epilog: For today's Albanians, the concrete bunkers built by Hoxha are an eyesore from the past that won't go away. There are more than 750,000 of them, about one for every four Albanians. Because the bunkers were designed to last through a massive bombardment, you can't just knock them down with a bulldozer, and Albania cannot afford the equipment needed to remove them. Therefore the Albanians have come up with creative ways to recycle their "concrete mushrooms." Hoxha's bunker was recently opened as a tourist attraction, while others have been converted into cafes, two-person homes, works of modern art, and in one case, a tattoo parlor.

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia gave the USSR no trouble while another Stalinist, Antonin Novotny, was in charge. However, he eventually fell out of favor in Moscow, and in January 1968 Alexander Dubcek, the reform-minded party boss of Slovakia, took his place. Almost immediately he began loosening the tight controls of the state in a program he called "socialism with a human face." He abolished censorship, rehabilitated the victims of "the past period of mistakes and aberrations," and even toyed with the idea of legalizing non-Communist political parties. Along with this he signed economic agreements with the West, particularly West Germany. Moscow warned Dubcek that he was making too many changes too fast, and when he did not heed the warnings, the Soviets struck. On August 21, 1968, Soviet, East German, Polish, Hungarian and Bulgarian divisions invaded and quickly occupied the country. Dubcek and his supporters were arrested, taken to Moscow in chains, and blackmailed to surrender. But thanks to universal Western and Chinese condemnation, the Soviets did not commit any atrocities in Prague after that.

Soviet tanks in Prague, 1968.

Dubcek got the last laugh; he lived as a private citizen for the next twenty-one years, and then took part in the revolution that toppled communism in his country. He had the right idea about "socialism with a human face," but was a generation ahead of his time.

East Germany

The German Democratic Republic (East Germany) was supposedly the best-run state in eastern Europe. In the 1970s East German standards of living were even higher than those of the Soviet Union, but compared to dynamic West Germany, the East didn't amount to much.(5) There also was no doubt about which part of Germany the Germans preferred; the number of East Germans defecting to the West peaked at 500,000 in 1960. Thus, to avoid losing its workers, East Germany had to lock them in. Here the Iron Curtain became three-dimensional, a physical barrier as well as one in the imagination.

First East Germany built barbed-wire and chain-link fences, minefields and guard towers, all along its border with West Germany. Whenever some defector managed to get over these obstacles, more were added, until this became the most heavily fortified frontier between two nations. However, there was still a problem with Berlin, where it was relatively easy for somebody in East Berlin to sneak over to West Berlin and not come back. Suddenly on August 13, 1961, East Germany began building a concrete wall, all the way around the 28-mile perimeter of West Berlin. To make the wall truly formidable, the construction crews added additional barricades: landmines, trip wires, broken glass, sentries with vicious dogs, etc. East German leader Walter Ulbricht called the wall an "antifascist protection barrier," to keep the enemies of communism out, but everyone knew its real purpose was to keep the East German people in.

The desire for freedom was so strong that some East Germans tried to get over the Berlin Wall anyway. Those who succeeded became local legends, and today Berlin has a museum to commemorate their exploits. One defector flew over the wall in a balloon; another had himself lowered on the other side by a crane. A West Berliner drove through one of the wall's gates to get his girlfriend out of East Berlin, and while he was on the east side, he cut the whole top half of his car off, so he could drive under the gate's lowered crossing barrier when he returned. An entire nursing home of senior citizens, located a hundred yards from the border, managed to escape by digging a tunnel with spoons. However, these were the lucky ones; 75 were killed by guards when they tried to cross. West Berliners showed how they felt by covering their side of Die Mauer ("the Wall") with graffiti, and they cursed the structure, declaring that moss would never grow on it. Even so, the Berlin Wall was a success in that it stopped the mass defections, and the officer in charge of its construction, Erich Honecker, succeeded Ulbricht as secretary general in 1971.

Hungary

Hungary saw the bloodiest anti-Soviet uprising in the Warsaw Pact. There Nikita Khrushchev's 1956 denunciation of Stalin became a signal to launch riots. The rioting turned into street fighting, and then open rebellion, when part of the Hungarian army joined the rebels. The Soviet forces pulled out of Hungary at the end of October; the new Hungarian prime minister, Imré Nagy, declared Hungary a neutral, multiparty state, and announced he was withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact. This was too much for the Soviets; the Red Army's armored divisions turned around and attacked Budapest, slaughtering the freedom fighters who had been celebrating their "victory." It was a massacre. As a sickened world listened, the rebel radio broadcast its last message: "Goodbye friends. Save our souls. The Russians are too near." More than 200,000 Hungarians fled across the Austrian border to a sickened West before order was restored. Nagy and hundreds of others were executed, and Nagy's successor, János Kádár, kept Hungary firmly in the Soviet camp for the next thirty years.

Ironically, Kádár succeeded for as long as he did because he made Hungary the most capitalist state in the Soviet Bloc. Although he kept absolute control over the Communist Party and the government, he allowed western-style economic reforms, long before the Soviet Union tried them. Peasants were allowed to earn a profit from their land, and industry was free from state control. This nearly free market improved the Hungarians' standard of living, so that by the 1980s one family in three had a car, and nearly half the population could take vacations abroad. However, they depended too heavily on trade with the West, which declined during the bad economic years of the 1970s and early 80s, so Hungary nearly went bankrupt by 1985. What kept the economy going at this time was the unofficial black market, which produced an estimated 30 percent of the nation's GDP in 1985. Two thirds of all apartments were built without government approval, and 80 percent of Hungarians made ends meet with an unofficial second job. It wasn't the safest way to live, but it allowed people to joke that Hungary had the most comfortable barracks in the Soviet concentration camp.

Poland

The USSR always had to go easy on Poland, due to the millennium-old hatred between Poles & Russians. There was also the Catholic Church, which was so strong in Poland that it served as an opposition party, especially after Karol Wojtyla, the cardinal of Cracow, became Pope John Paul II (1978). Thus, the USSR carefully avoided pushing the Poles too far. Despite this, the effects of de-Stalinization were felt immediately. As in Hungary, riots broke out here in 1956, but here the story had a happier ending. Wladislaw Gomulka, an anti-Stalinist who had recently been released from prison, used the unrest to get himself elevated to the position of Poland's first secretary, without Moscow's consent. He promptly expelled the Russian officers in Poland's army, dissolved the collectives, and allowed optional religious teaching in the schools. Khrushchev and three other Politburo members (Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazar Kaganovich and Anastas Mikoyan) flew to Warsaw and found an uncooperative Polish government staring at them. After a heated debate Khrushchev decided that he liked Gomulka, and left him alone after Gomulka promised to keep Poland's economic and military ties with the Soviet Union.

Gomulka's successor, Edward Gierek, was less successful at solving the country's problems. By the end of the 1970s, the economy was in dreadful shape, and on August 14, 1980, this triggered a strike at the Lenin Shipyard of Gdansk. Within weeks the strike was joined by others all over Poland, the strikers began demanding political rights, and Gierek was forced to step down. The strikers, led by an unemployed electrician named Lech Walesa, quickly formed a trade union named Solidarnosc (Solidarity), and by the end of the year its membership had grown to exceed that of the Polish Communist Party.

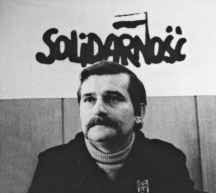

Lech Walesa.

Solidarity gave Marxist ideologists, like the Politburo's Mikhail Suslov, major headaches; Marxist philosophy repeatedly states that communism is a government for the workers, so the existence of unions was a strong indication that communism had not lived up to its promises; that's why labor unions were not allowed in the USSR. Suslov made a personal trip to warn the Poles that they had gone far enough. So did Walesa and other moderates, who now urged the Polish people to stop for the good of the nation, but food shortages, rationing, and strikes caused by radical workers got worse. On December 13, 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, the commander of Poland's armed forces, declared enough was enough and imposed martial law on the country. In defense, Jaruzelski argued that he had saved Poland from outside intervention; if the Poles did not put their own house in order, the Russians would do it for them. Solidarity was outlawed, but it was too popular to die; one year later Walesa was released from prison. Negotiations concerning the relationship between the government and the workers went on for most of the 1980s.

Romania

Romania's first communist leader, Gheorghe Gheorghiu Dej, died in 1965, and was succeeded by his protegé, Nicolae Ceausescu. Once his position was secure, Ceausescu began leading the country on a dangerous form of tightrope diplomacy--act as independent of the USSR as possible without triggering Soviet intervention. To start with, Romania remained in the Warsaw Pact, but did not allow the stationing of Red Army troops within its borders; it also refused to submit to Soviet economic planning. During the Sino-Soviet quarrel, Romanian newspapers printed the arguments of both major powers, and Chinese leaders made regular visits to Bucharest. Romania condemned the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, and the 1979 invasion of Afghanistan; moreover, it sent athletes to the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, defying the communist boycott imposed on the games. Romania even had good relations with Israel, which was unthinkable in the rest of the communist world. Thus, Romania became the same sort of maverick for the East that de Gaulle's France was for the West. The USSR permitted all this because Romania was not on the border of any NATO country; furthermore, Ceausescu wasn't interested in spreading his ideas to other Soviet Bloc states.

Nicolae Ceausescu.

Ceausescu was praised in the West as a champion of national self-determination. The Queen of England knighted him, and France granted him its Legion of Honor. Though his wife Elena was a dropout who could barely read, Ceausescu demanded that she be made a member of the New York Academy of Sciences and the Royal Institute of Chemistry--and both of those institutions accepted her, to avoid causing an incident. When he made a state visit to France, in the place where he stayed, everything worth taking was stolen, so when he came to London in 1978, Queen Elizabeth II prevented more kleptomania by having his guest rooms stripped of all valuables.

Romanian foreign policy concealed what Ceausescu was doing to his own people. There was persecution of the country's Hungarian minority, he tried to destroy the culture of the peasants by uprooting and resettling them in drab apartment complexes, and he filled the country with secret police. To gain much needed capital from abroad, he exported the country's abundant meat, grain and oil, making those items scarce at home.

Ceausescu's early success went to his head, causing him to build a personality cult around himself that rivaled Stalin's. He called himself "the Genius of the Carpathians," and became the first communist leader to carry a scepter in public. When the famous artist Salvador Dalí sent him a telegram congratulating him for "introducing the presidential scepter," Ceausescu didn't realize Dalí was making fun of him, and passed the note on to the Romanian newspapers, which published it the next day. In the 1980s Ceausescu grew paranoid and senile. Fearing that his clothing might be poisoned, he wore a new suit every day and had his clothes and shoes burned after a single wearing. For the trips he made, he brought his own food in a cooler, which was kept under armed guard (of course). When Ceaucescu went to Washington, DC, the US government let him stay at Blair House, the usual guest house for visiting heads of state, but before he arrived, his staff cleaned and disinfected the place, replaced the linens and pillows with approved Romanian ones, and installed radiation detectors. For his people, Ceaucescu launched strange economic programs and megalomaniac building projects that impoverished the country. By 1989 Romania was tied with Albania for the dubious title of Europe's poorest, most oppressed nation.

The craziest of Ceausescu's projects was a palace called the "People's House," meant to house himself and the entire national government. You may have thought Versailles was a grand palace (see Chapter 11), but for Ceausescu it wasn't grand enough; his palace is the world's largest government building, the most expensive administrative building (it cost $10 billion to build), and the heaviest building. By putting it in the historic district of Bucharest, he forced the tearing down of twenty-two churches (nineteen Orthodox, three Protestant), six synagogues and 30,000 homes to make room for it.

You can see what a ridiculous idea the palace was by what present-day Romania has done with it. It wasn't completed until 1997, eight years after Ceausescu's death, and the Romanians first renamed it the House of Ceausescu; then after both of the legislative houses moved in, it became the Palace of the Parliament. But even today, with the whole Parliament in there, only 30 percent of the building is being used.

Yugoslavia

Under Josip Broz Tito, Yugoslavia enjoyed its best years, but even then "Splitsville" might have been a more appropriate name. The country was divided into six republics (Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro and Macedonia), each for a different ethnic group. In addition, Serbia had two autonomous districts: Voyvodina, with a Hungarian minority, and Kosovo with its Albanian majority. Because he had mixed Croat-Slovene ancestry, Tito discriminated in favor of the non-Serbs whenever there was a boundary question. The result was that he drew the borders so that there were Serbs in Croatia and Bosnia, but no Croats or Bosnians in Serbia.

Tito's Yugoslavia, showing the republics and autonomous districts.

In foreign policy, Tito successfully cultivated his image as the head of a neutral state. At international conferences he often appeared with other famous neutral leaders, like India's Jawaharlal Nehru and Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser. He also entertained Khrushchev and Brezhnev when they visited Belgrade, but neither guest could persuade him to return to the Soviet fold. At the United Nations, Yugoslavia generally voted with other communist countries on most issues, but condemned the Soviets for intervening in Korea and Czechoslovakia. The last conference he attended was the 1979 meeting of the nonaligned nations in Havana, and there he claimed he was a better representative of the Third World than the host, Cuba's Fidel Castro.

Economics proved to be the one challenge Tito couldn't overcome. The 1950s and 60s saw rapid growth, urbanization and industrialization, as Western nations rushed to do business with Yugoslavia; the country also became a popular tourist destination. However, the incoming money was not distributed evenly. Slovenia, Croatia and Voyvodina became the richest areas, while Kosovo was the poorest. From 1965 to 1988, a massive welfare program transferred funds from rich republics to poor ones. It didn't work, and the controversial program was abandoned because it produced no significant results. The Slovenes and Croats came to resent the Serbs for taking their profits away, calling it an abuse of federal power against the republics, while Kosovo's lack of development suggested that much of the money earmarked for it never reached the intended destinations. During Tito's final years, the country suffered from inflation, unemployment and strikes, and the trade deficit bloomed to $15 billion per year, one of the world's highest.

Tito died in 1980, after two months in the hospital. The mourning at his funeral was real, because all Yugoslavs knew that nobody could hold the country together as well as he had. The 1974 constitution called for Tito's successors to set up a rotating government, where the leaders of the republics, and the leaders of the two autonomous districts, took turns as president, each serving for one year. The system worked for a decade, so all eight regions got their turn in the president's chair. Still, a solution like this is not a formula for stability, and the deteriorating economy eventually undermined it.

Fascism's Last Stand

Winston Churchill may have called the Mediterranean "the soft underbelly of the Axis beast," but in Spain, Portugal and Greece, harsh dictatorships existed long after the war. Spain's Francisco Franco called the Loyalists "Reds" who had been "anti-Spain," imprisoned hundreds of thousands, and executed 37,000 opponents by 1943. By then, the Allies were winning the big war against the Axis powers, so Franco eased up to avoid their wrath. Nevertheless, until the beginning of the Korean War, the United Nations ostracized his regime, and many countries cut off diplomatic and other relations with Spain. With the complicity of France, surviving Loyalists started a new guerrilla war. Most of Spain saw guerrilla activity well into the 1950s.

During the Cold War, the Americans were willing to forgive Spain in return for Spanish support against communism, so in 1953 Spain gave the United States the right to use Spanish air and naval bases, in return for important military and economic aid. Two years later, Spain was finally allowed to join the UN. However, Franco's fascist origins were not completely forgotten; many European nations remained unfriendly, and Spain was kept out of NATO. Still, open hostility ended, and Spain was no longer a pariah nation.

Franco had the backing of three conservative factions: the army, the Falange Party, and the Church. In 1947 he announced that Spain would return to monarchy after his death, but waited until 1969 to choose an heir: Juan Carlos, grandson of the last Bourbon king, Alfonso XIII. During the second half of his reign, Franco released control over business and labor, and Spain's economy finally industrialized. Abroad, Spain avoided wars in Africa by giving its colonies (Equatorial Guinea, the Western Sahara and part of Morocco) independence. The country saw unprecedented growth, foreign investment and socioeconomic change during the 1960s, but in politics El Caudillo (the Leader) remained oppressive; in fact, he ruled by martial law from 1962 to 1970. This was because he could not suppress the Basques in the north and the Catalans in the northeast, after peace had returned everywhere else. The Catalans weren't really Spanish, and they remembered how on several occasions they had been part of France (see Chapters 7, 11 and 12). The 1931 revolution had given the Catalans their own president and parliament, but they lost these gains when Franco took over, because of their support for the Loyalists. It took a restoration of limited Catalan autonomy to satisfy the folks in Barcelona, and that didn't happen until 1977, two years after Franco's death.

The Basques were far more difficult to please. Four hundred years of Spanish rule had not extinguished their desire to be free; one of their favorite mottos was: "Neither slave nor tyrant." Like the Catalans, the Basques enjoyed autonomy from 1931 to 1939, and under Franco they formed a separatist movement called the ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasuna, meaning Basque Homeland and Liberty). In 1969 they began a campaign of terrorism, and the government responded with counter violence against random targets in the Basque provinces. One year later several ETA members were sentenced to death, but international pressure caused the government to back down and commute the sentences. The ETA scored its biggest success in 1973, when a car bomb assassinated Premier Luis Carrero Blanco. The regime was badly shaken, but the next premier, Carlos Arias Navarro, chose liberalization instead of repression; his program included the legalization of political associations, which had been banned since 1939. Hard-core Phalangists opposed this, and after they sabotaged Arias's attempted reforms, they passed a law requiring the death penalty for terrorists who killed police. As a result, five Basques were executed in September 1975, but this was the last hurrah for the fascists. Already gravely ill, Franco went into the hospital around this time; two months and five heart attacks later, he was dead.

Juan Carlos never wanted to be anything more than a constitutional monarch, so the fascist regime was quickly dismantled. In July 1976 he appointed Adolfo Suárez González, a moderate Phalangist, to succeed Arias, and Suárez successfully led Spain's transition to democracy. First Suárez introduced the Political Reform Law, which was approved by referendum in December 1976; then he legalized the Communist Party, despite strong army objections. In June 1977 the first democratic elections in four decades gave him a vote of approval; his new party, the Union of the Democratic Center (UDC), won 34 percent of the vote, with the Socialists a close second. A new democratic constitution, introduced in 1978, did much to decentralize the government by granting autonomy to seventeen regions, especially Catalonia and the Basque country.

Suárez ran into problems after that. His policy of cooperation with other parties broke down, and the economy went into a recession. He resigned in January 1981, and was succeeded by Deputy Prime Minister Leopoldo Calvo Sotelo. This administration only lasted for a little more than a year; the main accomplishment was Calvo Sotelo's decision to have Spain join NATO. The next time elections took place (October 1982), the Spanish Socialist Workers Party, led by Felipe González Márquez, won a decisive victory. Despite his leftist background, González acted moderately once in office, and thus was able to manage the country for fifteen years.

Among the fascist regimes of twentieth-century Europe, Portugal's was both the least belligerent and the longest lived. Antonio Salazar ruled for forty years, giving us some idea of how long Adolf Hitler might have lasted, if he hadn't been such a bully-boy; Salazar never even set foot outside of Portugal. However, he also presided over a terribly backward country; the Portuguese were 30 percent illiterate, and had the second highest infant mortality rate in Europe.

We already noted that Portugal sat out World War II, but its economy suffered anyway. The fishing industry declined, exports lessened, and refugees crowded the country; in the Pacific, Japan's occupation of Timor didn't do the Portuguese any good. By the end of the war, unemployment and poverty were widespread, but the National Union remained in total control. In May 1947, after crushing an attempted revolt, the government deported numerous labor leaders and army officers to the Cape Verde Islands. Marshal Carmona died in April 1951 and General Francisco Lopes, another ally of Salazar, became the next president. Lopes served until 1958 and was then in turn succeeded by Rear Admiral Américo Deus Tomás.

The brush fire of nationalism which had brought down other colonial empires spread to Portugal's colonies around this time. Rebellions broke out in Africa (Angola, Mozambique and Portuguese Guinea) during the early 1960s, while India annexed Portuguese Goa in 1961. Lisbon tried both the stick and the carrot; it sent in the army against each rebellion, while granting Portuguese citizenship to Africans in the territories. Neither had much effect, and the United Nations condemned Portugal for waging "colonial wars."