| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 2: Colonial America, Part 2

1607 to 1783

This chapter is divided into three parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| Jamestown | |

| The Search for a Northwest Passage (concluded) | |

| The Founding of New France | |

| They Came on the Mayflower | |

| New Netherland | |

| Colonization: The Second Generation | |

| New Amsterdam Becomes New York | |

| Carolina | |

| The Last French Explorers |

Part II

Part III

| The California Missions | |

| "The Shot Heard 'Round the World" | |

| Through the Cumberland Gap | |

| From Fort Ticonderoga to Boston | |

| The Declaration of Independence | |

| The (British) Empire Strikes Back | |

| Saratoga: The Turning Point | |

| Valley Forge and the Battles for Philadelphia | |

| On the Wild Frontier | |

| Showdown at Yorktown | |

| The Treaty That Ended It All |

Colonial Growing Pains, Part 1

The English colonies didn't grow much while the French were exploring North America's interior. Mostly they were tied up with internal struggles, first against the Indians, and then against the government of the mother country. William Bradford, the most important Pilgrim leader, had died in 1657, and Massasoit died in 1660; the next generation of leadership on both sides did not think it was so important to maintain good relations. From the Indian point of view, the problem was a land dispute; the colonists were always trying to take more Indian land for themselves, despite previously signed treaties. The Wampanoag, Narragansett, and Nipmuc tribes formed an anti-white alliance, led by Metacomet, Massasoit's second son, and in 1675 they began attacking English settlements. The English called this conflict "King Philip's War" (King Philip was their nickname for Metacomet), and it proved to be even bloodier than the Pequot War; the Indians destroyed 12 Puritan settlements, attacked 40 more, and killed or captured one out of every ten adult male English settlers. The colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island struck back, burning Indian villages, destroying crops, and capturing Indian women and children. Metacomet was killed in August 1676 (his head was displayed on a pole at Plymouth for the next twenty-five years), the near-extermination of all tribes in southern New England followed, and their lands were taken over by the colonies.

In the south, the governor of Virginia, William Berkeley, ordered land-hungry settlers to stop harassing the Indians. The settlers, led by Nathaniel Bacon, instead launched new raids on the tribes. Governor Berkeley declared Bacon a rebel, and offered to pardon him if he would go to England to stand trial before King Charles II, but many members of the House of Burgesses were sympathetic to Bacon's grievances, which included opposition to the governor's higher taxes, and that allowed him to get elected to the House in June 1676. The governor thus had to pardon him anyway, but during a debate on the Indian situation in late July, Bacon and his men surrounded the state house, forcing the governor to give in to Bacon's demand to fight the Indians without government interference. After that the rebels were in control of Jamestown; when Berkeley showed up in September with a militia to recapture the capital, Bacon burned it to the ground. A few weeks later, Bacon died suddenly of disease, and the revolt known as "Bacon's Rebellion" fell apart; when soldiers arrived from England at the end of the year, they didn't have to do much to restore order.(19)

The colonial government moved to nearby Williamsburg until Jamestown could be rebuilt. Then the statehouse in Jamestown burned down again in 1698, this time from an accidental fire. The House of Burgesses decided that it liked Williamsburg better, due to a better climate (remember the James River swamp) and because the College of William and Mary had recently been built there, so in 1699 Williamsburg became Virginia's new permanent capital.

The king may have been satisfied with how the situation was resolved in Virginia, but he was upset at New England, where the locals refused to observe the "Navigation Acts" that were enacted to protect English shipping, and their Puritan-run governments discriminated against his church. In 1671 John Evelyn, a member of the Royal Council of Foreign Plantations, wrote in his diary that New England appeared "to be very independent as to their regard to Old England or His Majesty," and was "almost upon the very brink of renouncing any dependence on the Crown!"(20) To make his colonies loyal and profitable, King Charles ended up employing the same solution that had worked for Virginia half a century earlier--he put his own man in charge of the place. In 1677 he separated New Hampshire from the Massachusetts Bay Colony (he also didn't like Massachusetts ruling Maine, but Maine was so undeveloped that he left it alone for the time being), and in 1684 he revoked the charter of Massachusetts, turning it into a crown colony. Shortly after that, Charles died and was succeeded by his brother, James II. James had an even grander idea; he sent only one governor, Sir Edmund Andros, and put him in charge over all of the New England colonies, calling this new state the Dominion of New England (1686). One year later he expanded the Dominion to include New York, New Jersey and Nova Scotia as well.

Andros had the power of a dictator. Under his harsh rule the colonists were not allowed to have a representative assembly, town meetings were permitted only once a year, taxation was imposed by the government without the consent of the colonists, and the governor supported the Church of England against the interests of the Puritans.(21) All these moves greatly angered the people of Massachusetts, and when they learned in 1689 that James II had been overthrown in the "Glorious Revolution," Andros was seized and a temporary Puritan government took over for the next two years. In 1691 the next king, William III, issued a new set of royal charters that gave all the colonies pretty much the same type of representative government, and merged the Massachusetts Bay Colony with Plymouth, Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, Maine and Nova Scotia.

This marked the creation of present-day Massachusetts, and ended the Puritan theocracy for good. Of course the Puritans weren't happy with this, and it was also around this time that the New England colonies came under attack from the Catholic French and their Indian allies (See "King William's War" below). No doubt some thought the Devil was trying to destroy God's sanctuary in America, and this helps to explain the wave of hysteria that struck Salem, Massachusetts, which led to the most notorious episode in America's colonial history, the Salem Witch Trials. Details of the trials are still controversial today; we don't know for sure if any of the people accused of witchcraft had actually practiced it, and some of today's Wiccans claim to be descended from witches convicted at Salem. From June to September in 1692, 156 people were accused; fourteen women, five men and two dogs were hanged (children accused the dogs of giving them the "evil eye"); another suspect was slowly crushed to death under heavy stones when he refused to take part in his trial; and four people died in jail while awaiting their trials. A second round of trials in the winter of 1692-93 involved nearly 150 cases, but only resulted in three convictions, and a few months later the governor pardoned the defendants. By this time many protested that the trials had been conducted too hastily, using faulty evidence. Increase Mather, the most respected minister in the colony and the father of another famous minister, Cotton Mather, argued that the Devil might indeed be involved, but if he was, he was fooling people into blaming the innocent, rather than giving his servants occult powers. The common people still believed in witchcraft, and stories of witches remained a popular subject, but the rulers of the colony allowed no more witchcraft trials.(22)

The Founding of Pennsylvania

Meanwhile in the mid-Atlantic region, one more colony got started, and if any of them reflected the true spirit of the country that would arise in the next century, it was this one. The founder was William Penn, an activist for the Society of Friends (Quakers). Penn's father, a wealthy admiral who was also named William Penn, had loaned money to King Charles II before his death in 1670, and instead of being repaid, the younger Penn asked the king for part of New York, to set up a Quaker colony. Quakers weren't popular in seventeenth-century England, so the king agreed, happy to be rid of both his debt and the Quakers. Penn received a royal charter in 1681, and he named the colony Pennsylvania, meaning "Penn's Forest" in Latin. Unlike previous colonies, which usually granted freedom of worship to one religion, Penn promised freedom to all religions; the city he founded in 1682 was named Philadelphia, meaning "Brotherly Love," and intended to be a model of tolerance.(23) The city and the colony were an immediate success, attracting not only Quakers but also Welsh, Germans, Scots-Irish, Amish, Mennonites, and other immigrants who were suffering from persecution elsewhere. While Penn was alive, Philadelphia grew to become the second largest city in Anglo-America--only Boston was larger. Soon Philadelphia would also become the home of the first "Founding Father" of the United States--Benjamin Franklin (1706-90).

For a few years there was some confusion over who owned Delaware. When we last looked at Delaware, it was one of the Duke of York's properties, along with New York and New Jersey. King Charles had promised it to Penn, so that his new colony would have access to the sea, but for some reason it was not mentioned in the charter. Local politics settled the issue; Pennsylvania grew so quickly that the politicians had trouble getting along, and decided in 1704 to meet in two separate locations, Philadelphia and New Castle. Because this arrangement worked better, the New Castle legislature got its own governor in 1710, making the Pennsylvania-Delaware split permanent.

While Pennsylvania and Delaware were getting on their feet, New York and New Jersey endured the worst governor in American history--Edward Hyde, better known as Lord Cornbury (1661-1723). The eldest son of the Second Earl of Clarendon, Lord Cornbury spent sixteen years in Parliament, where he made plenty of enemies, because he was greedy, arrogant, dishonest and bigoted. Worst of all, he spent money like water and raked up massive debts. About the only person in England who liked him was his cousin, Queen Anne. Accordingly, when the queen offered him a seven-year assignment as governor of New York and New Jersey, Cornbury eagerly accepted, because this would put a whole ocean between him and his creditors.

Lord Cornbury came across "the Pond" in 1702 to take up his new job. From the queen he received £2,000 to cover his traveling expenses (about $800,000 in today's dollars), and his entire salary paid in advance. That should have been enough, but he quickly spent it anyway. When the money ran out, he asked the New York legislature for more; they refused and he dissolved the assembly. Then he tried to get cash from the New Jersey government, with the same results. In the end he embezzled the state treasuries for the funds he needed, including £1,500 that was supposed to go toward the defense of New York Harbor.

Why did Cornbury need so much money? That was the real reason why people detested him; he spent it on a hobby so outrageous, that even today it would get him in trouble. Cornbury loved fancy clothing, and wanted to be the best-dressed person in the colonies. The kind of clothing he wore was fancy women's clothing. Typically he would appear at public ceremonies in a dress, with silk stockings, a fancy hairdo, long uncut nails, and sometimes high-heeled boots. Yes, the governor was a transvestite.

The only existing portrait of Lord Cornbury.

The last straw came when Cornbury meddled in religious affairs. A proud member of the Church of England, he fined and jailed some Presbyterian ministers for preaching without a license. The settlers saw this as so unfair that even an Episcopalian jury was willing to let the preachers go free. When the queen heard about this and other complaints, she ordered Cornbury's removal from office, one year before his term was due to end. He had to do time in a debtor's prison, but after he got out he went back to Parliament and spent the last years of his life in the House of Lords, calling himself the Third Earl of Clarendon.

The Importance of the Religious Element

Most history books that discuss colonial American history will mention the religious element; groups like the Puritans and Quakers, incidents like the founding of Plymouth and the Salem witch trials, and how important it was for most colonists to be able to worship according to their consciences. We aren't so pious today, so why should we remember that people felt differently, three hundred years ago? It is because in the aftermath of the Reformation, different denominations became dominant in different colonies, so the settlers not only resented the king telling them what church they could go to--they also didn't want other colonies telling them what church was right for them. A few quotes will show how much suspicion they had for each other at this stage.

- A Puritan describing Virginians: "The farthest from conscience and moral honesty of any such number together in the world."

- A Virginian, William Byrd II, describing the Puritans: "A watchful eye must be kept on these foul traders."

- But both Virginians and Puritans agreed on what they thought of the Quakers: "[They] pray for their fellow men one day a week, and [prey] on them the other six."

- While the Quakers felt the same way about the Puritans, calling them "The flock of Cain."

The Lone Star Colony

So far we haven't heard from Spain in this chapter. In fact, from our point of view, it seemed that the Spanish Empire went to sleep after the battle of the Armada; it stopped expanding anyway. It took the encroachment of La Salle and other representatives of France into territories they had long seen as theirs to wake the Spaniards up again; if they did not settle the Gulf Coast, they ran the risk of losing it. In the late seventeenth century they had begun expanding their activity in Florida from St. Augustine, and they built their second Pensacola fort in 1696, this time to keep the French from expanding any more to the east.

There was quite a bit of trouble in New Mexico during the seventeenth century, which may have been why the Mallet brothers got such a chilly reception when they tried to do business there. The Pueblo Indians resented being forced to work as slaves, and when Spanish priests only converted a few of them to Christianity, they tried to get to the rest by preventing native ceremonies. A series of minor revolts broke out from 1640 onward; the big revolt came in 1680 when Popé, a medicine man from Tewa Pueblo, enlisted the help of the Apaches, and together they destroyed the missions and killed every Spaniard they could get their hands on. A new Spanish force came up from Mexico, took back Santa Fe in 1692, and spent the next four years reconquering the territory.

Spain also got serious about Texas. In the days before oil and the internal combustion engine, it was hard to get people to go to Texas, because it just didn't seem to have anything of value. Well, missionaries have a motivation to go into places with no obvious resources. In 1682 Spanish priests established a mission at Ysleta, a village near present-day El Paso. After La Salle built a fort in Texas, Spain sent a military expedition from Mexico to uproot it. They arrived in 1690 to find it already destroyed, with all of the adult inhabitants killed; the Karankawa Indians, however, had spared five children, and eventually the Spaniards recovered them. More clergymen came afterwards to start new missions, but all of them were difficult to maintain and quickly abandoned. That's the way things stood until 1714, when some French traders came to the Rio Grande and set up a fort near the modern town of Eagle Pass. Again, the Spaniards were alarmed. Because keeping the French out had become their main motivation for settling Texas, they established more than 30 new missions from 1716 onward, and a town, San Antonio, was founded near six of them in 1718. We will be hearing more about one of those missions in the next chapter--the Alamo. Finally, Spain rebuilt La Salle's Fort St. Louis in 1721, and renamed it Presidio La Bahia, to defend the Texas coast.

Spain also claimed the plains north of Texas, but did not do well here. In 1720 a group of Spanish soldiers and settlers from New Mexico, with their Indian allies (Pueblo and Apache), advanced into the plains as far as eastern Nebraska. At the junction of the Platte and Loup Rivers, they were ambushed by Indians from two pro-French tribes, the Pawnee and the Oto. It was not a battle so much as a rout; 35 Spaniards were killed, including the commander, Don Pedro de Villasur, along with ten Pueblo scouts. Surviving Indians painted pictures of the battle on buffalo hides, two of which still exist today. This was the only evidence of the clash until recently, when fragments of some Spanish-style olive jars were found with Indian artifacts in a suburb of Omaha; apparently Omaha was an Oto campsite in the early eighteenth century, and some of the loot captured from the Spaniards was taken there. At any rate, Spain sent no more expeditions into the plains, allowing France's claim over the Louisiana territory to stick.

It's hard to find anything Europeans did in the colonial era that improved the lives of Indians. One thing that did help was the introduction of horses. The Spaniards had brought horses to use in their colonies, and some of them escaped, becoming the wild mustangs of the American wilderness. The nearest tribes to the New Mexico colony, the Navajo and the Apache, acquired horses first; in 1659 Spain reported the first raid by Indians (Navajo) on horseback. For the other tribes, their opportunity came with the great Pueblo revolt of the 1680s. When the Spaniards abandoned New Mexico, they left their horses, sheep and goats behind; the Pueblo, however, are a sedentary people, so they did not have much use for horses, and simply turned them loose.

The place where horses had the greatest impact was on the Great Plains. Previously, life on the plains had been tough, especially after enemy tribes to the east acquired guns from European traders. The tribes we associate with the plains today (the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa and Comanche) only ventured onto the plains to hunt buffalo, and spent the rest of the year elsewhere. Then around 1700, the Sioux captured and learned to ride horses, and this transformed their entire culture. To start with, they moved from their previous home in southern Minnesota, to the Black Hills of South Dakota, choosing to live on the plains all year round. Now that they could outrun the buffalo and other Indians, and transport heavy loads(24) when it was time to move, the tepee-dwelling plains Indians became the ones with the desirable lifestyle, and they were such good warriors on horseback that admirers have called them "the world's best light cavalry." Today, if you ask someone to think of an Indian tribe, there's a good chance he will imagine the Sioux, or another nomadic tribe that successfully imitated them.

Colonial Growing Pains, Part 2

The Carolina colony grew large enough to have its own version of Bacon's Rebellion in 1711. Called Cary's Rebellion, this was a dispute over who should be the deputy governor. Because the colony had allowed religious freedom from the start, quite a few of its settlers were Quakers; in fact, George Fox, the founder of the Quaker denomination, paid a visit to Albermarle in 1672. By 1705 there were enough Quakers in the northern part of Carolina for one of them, Thomas Cary, to become deputy governor. But Cary turned out to be a strong friend of the Anglican establishment and enforced their rules, which included a requirement that everyone in the government swear an oath of loyalty to Queen Anne (Quakers do not take oaths). The disappointed Quakers persuaded a Lord Proprietor to go to England and have Cary removed from office. Cary did not stay away from northern Carolina for long, and when he returned his supporters ousted his replacement. Now Cary decided that since he was a Quaker, he should be on the side of the Quakers in the colony, so he did away with the oath requirement. Thus, the Quakers ran half of Carolina until 1711, when the Lords Proprietor announced that Cary's term was up and the new deputy governor was an Episcopalian named Edward Hyde (not Lord Cornbury!). Cary refused to step down, followers of Hyde and Cary armed themselves, and after a month-long staredown, they started shooting at each other in the town of Bath. The skirmishes were inconclusive until Alexander Spotswood, the governor of Virginia, sent a company of royal marines to help the Hyde faction. Because Quakers are pacifists, Cary could not order his followers to shoot British soldiers, and the rebellion instantly fell apart. Cary was captured and taken to England to stand trial for treason, but because no one bothered to show up and press charges, Cary was released a year later; he returned to Bath and gave no more trouble.

Cary's Rebellion coincided with a yellow fever epidemic and a drought, so the Tuscarora, an Indian tribe in the Roanoke area of Carolina, had it really rough at this time. Fed up with European diseases and settlers encroaching on their lands, the Tuscarora declared war on the Carolina colony in September 1711, just two months after Cary's Rebellion ended. They didn't get very far, because Deputy Governor Hyde called out the militia and inflicted a crushing defeat on them in the following year. After the Tuscarora War, part of the tribe migrated north to New York, and were allowed to join the Iroquois in 1722, turning the five-nation Iroquois confederacy into a six-nation one.

The Indian tribes living in the future states of Georgia and Alabama were together called the Creek, because many rivers and smaller streams ("creeks," get it?) ran through their territory; sometimes they are also called Muskogeans, because the dominant tribe among them were the Muskogee. However, it was another tribe among them, the Yamassee, that first came into contact with Europeans, in the sixteenth century. At the time, they lived in what is now southern Georgia, but pressure from the Spaniards eventually forced them to move to the north side of the Savannah River, so when Carolina was founded, they were in the part of it south of Charleston. After that, they traded furs with the white man for guns, and fought on the side of the settlers in the Tuscarora War, but soon the inevitable culture clash between natives and settlers happened here, too. By now the Yamasee had several grievances, which included losing agricultural and hunting land when the settlers set up rice plantations, losing deer to white hunters, abuses by the white traders which put the Yamasee in debt, and traders enslaving Yamasee women and children when those debts could not be paid. When the Yamasee could not take this anymore, they got together with the Ochese, Waxhaw and Santee tribes, and in early 1715 they attacked white trading posts and settlements, starting with the Pocotaligo massacre. For Carolinans, the Yamasee War (1715-17) was as disastrous as King Philip's War had been for New England; 400 settlers were killed, about 7 percent of southern Carolina's white population. At one point, the town of Port Royal was abandoned, and it looked like the Yamasee-led coalition would take Charleston. It didn't happen because the Cherokee eventually decided to fight with the settlers against their Creek rivals. Likewise a tribe with the Yamasee, the Catawba, gave in to the lure of British-made goods and switched sides, and those Tuscarora Indians who had not yet gone north supported the Carolinans, feeling it was time to make friends with the white man again. Finally the Virginia militia came to save the day, and the Yamasee were defeated. Forced to flee from their villages in Carolina and Georgia, the tribes in the Yamasee coalition disintegrated; surviving members of those tribes went to Florida and joined the Seminoles.(25)

Because of all the incidents described above, London decided that Carolina was too large to govern effectively, and in 1729 the colony was divided into North and South Carolina. Also, both Carolinas would now be crown colonies--no more Lords Proprietor.(26) But that wasn't the end of the reorganization of the South. In 1733, James Oglethorpe arrived on the Atlantic coast and founded the city of Savannah, the first step toward creating the colony of Georgia. A former general and member of Parliament, Oglethorpe's favorite cause was the plight of the poor; he thought that those who are bankrupt do not deserve to go to a place like debtor's prison, where living conditions are abominable, and suggested that they be given a second chance in America. He got King George II's endorsement of the idea when he proposed putting the new colony in the south, as a buffer state between the other British colonies and Spanish Florida, and filling it with farmers and soldiers to defend the frontier. To avoid antagonizing the Creeks, the land for Georgia came from the southernmost part of the Carolina land grant, where nobody had lived since the Yamasee and Ochese abandoned it. Thus, colonial Georgia was limited to the area between the Savannah, Ocmulgee, and Altamaha Rivers, less than half of present-day Georgia.

Oglethorpe's idea for Georgia was that if he could move England's ne'er-do-wells to his gigantic "poor farm," and carefully manage their activities, he could make them prosper. Instead of setting up a conventional government, Oglethorpe and his associates called themselves "trustees," and ran Georgia like a charity or public assistance agency. Because they wanted their settlers to work hard for themselves, they banned the sale of liquor and prohibited slavery. They also interviewed candidates for relocation to Georgia, to make sure they were people who deserved a helping hand. There wasn't even a legislature like Parliament or the House of Burgesses, because the trustees reasoned that they had the best of intentions and already knew what was best for the people, so why should a second opinion from their "wards" be allowed to get in the way? Unfortunately, it was hard to make a southern colony grow in those days without slave labor, and the colony did so badly in the first generation of its existence that Oglethorpe had to lift the ban on slaves in 1750. In 1752 the trustees were forced to admit that their system of administration had failed to turn the unthrifty poor into thrifty folks, and they handed over their charter, one year before it was due to expire; Georgia became another crown colony after that.

Sideshows to European Wars

If you have read my European history, you know that seventeenth-century Europe was a place full of petty states, especially in the expiring "Holy Roman Empire," which hadn't been holy, Roman, or an empire for a long time, to paraphrase what the philosopher Voltaire said about it. These petty states often started petty wars for petty reasons, and because France and England were arch-rivals, if one of them got involved, the other was likely to join the other side, turning a little war into a big one. Therefore it was expected that French and English citizens overseas would fight each other, once both sides had colonies worth defending. Three such wars took place between 1680 and 1750, and while they didn't make much of a difference on the ground (they were won or lost in Europe, after all), they prepared the colonists for a future war that was big enough to be decided in North America.

The first war, lasting from 1688 to 1697, was called King William's War(27) in America, and either the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg in Europe. Basically, it was a showdown between King Louis XIV of France and all his European neighbors. In North America it was a draw, because the French did better on land, while the English did better at sea. From the St. Lawrence valley the French made successful raids on English frontier settlements in New York and New Hampshire, the most famous being the Schenectady Massacre of 1690, while their Indian allies, the Abnaki of New Brunswick, did the same thing in Maine. They had the advantage because the English were in a weakened state after the recent turmoil in Massachusetts, and were counting on the Iroquois to help defend the colonies, but the Iroquois were now past their peak. The English navy captured Port Royal, the main French outpost in Nova Scotia, but an attempt to take Quebec failed. Then the war ended; the Treaty of Ryswick put everyone in America back where they had started, and both sides had a five-year break before they were drawn into the next European conflict.

The next war was Queen Anne's War (1702-1713), also known as the War of the Spanish Succession. The French had Spain on their side, but the longer the war went on, the worse it got for both of them. In North America, it began with the English capturing St. Augustine, Florida, and they successfully defended Charleston from a Franco-Spanish counterattack. On the northern front, the French and Indians raided New York and New England again, but their only triumph worth noting was the destruction of Deerfield, Massachusetts, in 1704. And to nobody's surprise, the English navy took Port Royal again (1710). When the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713, France had to give up its part of Newfoundland and the Nova Scotia peninsula; the French also had to drop their claim to Hudson Bay. As in the previous war, the terms of the treaty were dictated by how the battles went in Europe, not in America; the French wouldn't have lost as much if only the American battles had counted.(28)

The growing French disadvantage wasn't obvious, though, to someone looking at a map of North America. Now that the French had forts on the Gulf Coast at Biloxi, Mobile and New Orleans, it was theoretically possible to attack the British colonies from the south as well as from the north. The French even captured Pensacola in 1719, as part of a brief war with Spain (the War of the Quadruple Alliance). Even so, there would not be a southern front in this war. The reason why a southern front did not appear is because the French could not persuade the Creek tribes to join their side; the Creek had more respect for the arms and ability of the British. British activity in the area, which was covered in the previous section, soon proved them right.

The founding of Georgia was a smart move because tensions between Britain and Spain increased during the 1730s, leading to the War of Jenkins' Ear in 1739, and an unsuccessful British attack on St. Augustine. One year later, all the major powers in Europe began fighting each other, over the issue of who should rule Austria, and the small War of Jenkins' Ear turned into the big War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48), or as the colonists called it, King George's War. This war is less interesting to us than the others covered in this section; in most places it was an inconclusive stalemate, and the only excitement was in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. This was where the French had suffered most of their losses from the previous war, but they still had a large island called Isle Royale (modern Cape Breton Island), so in the years between Queen Anne's War and King George's War, they relocated the displaced Newfoundland settlers to Isle Royale, and built a powerful fortress there, Louisbourg. The problem was that when you have a fort thousands of miles from home, you need not only strong walls, but also a strong navy to keep it supplied. In 1745 the British navy transported the New England militia to Isle Royale, and together they took Louisbourg after a seven-week siege. Fortunately for the French, the European phase of the war ended in a tie, so the British had to give Louisbourg back after the war ended. Once the French returned, they ignored the fort's poor performance and began pouring more money down the same rathole, thinking that if they spent enough on fortifications it would not fall a second time.

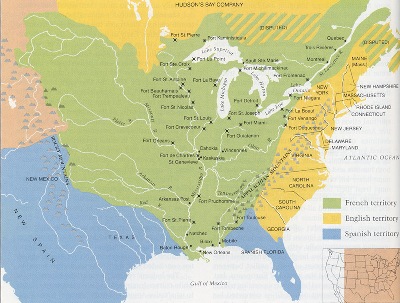

North America before the French and Indian War. Click on the above thumbnail to see the full-size map (Opens in a new window).

The French and Indian War

The king of France and his ministers didn't care much for their American colonies; rather than treat them as new lands worth developing, they saw them as places to exploit, and to be traded away if they could get something better at the conference table. Every time the French lost a battle, their position in America grew more precarious; every time they won, it only postponed the next defeat. And the British were clearly getting closer. Now that the British were moving into Georgia, the South became a potential war zone, because three European nations (Britain, France and Spain) claimed the lands that would someday become the states of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee. In the north, the British built Fort Oswego on the eastern shore of Lake Ontario--until now the Great Lakes had been completely within the French sphere of influence. In 1749 the French sent an expedition down the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers, and they buried lead plates in several locations which said that France owned those valleys. But then the French realized that the British only respected territorial claims of other nations if they settled the land in question, so in 1753 they began building forts in the Ohio valley. One of those forts was Fort Duquesne, where the Monongahela and the Allegheny Rivers join to form the Ohio River. The Ohio valley was in an area claimed by Virginia (the old "sea to sea" claim, from the original charter of the Virginia Company), so Virginia Governor Robert Dinwiddie wrote a letter ordering the French to leave.

Warning: Satire! A long time ago (but not in a galaxy far, far away!) it looks like an Imperial Stardestroyer crashed on the site where Fort Duquesne (modern Pittsburgh) would one day be built.

The job of delivering that letter went to an officer who had been in the Virginia militia for less than a year--Major George Washington. Washington came from one of the established families in the "Virginia aristocracy," but his father had died when he was eleven, so he wasn't very rich--personal ability and ambition had gotten him to this point, rather than wealth or family connections. When he heard about the letter-carrying assignment, he volunteered for it, figuring this would earn him fame and a chance to transfer into the more prestigious British army. He earned fame, all right--Virginians knew little about what was beyond the Appalachians, and when Washington got back he wrote an account of his journey that immediately became a bestseller in the colonies. The mission, however, was a failure. Washington went to the nearest fort, Fort Duquesne. The French commander of the fort thought Washington was a fine fellow--tall (6' 2"), handsome, and already possessing some of the qualities that marked him as a future leader--but he couldn't take either Washington or the letter seriously, for these reasons:

- Washington was only twenty-one years old.

- Virginia was too small to fight the French on its own, and its militiamen had a reputation for drinking, not for winning battles.

- Speaking of soldiers, Washington didn't bring any with him, only some guides. Did that mean Virginia had no soldiers to spare, should the situation turn ugly?

Europe was enjoying a rare moment of peace, so when the world heard about this incident, the British politician Horace Walpole called it "a shot fired by a young Virginian in the backwoods of America [that] set the world on fire." There was general agreement, both in London and in the other colonies, that the French must go, and that Virginia was going to need some help. Even while Washington was besieged at Fort Necessity, seven colonies (the four in New England plus New York, Pennsylvania and Maryland) sent representatives to a conference in Albany, NY, where the topics were forming a united front against the French, and improving relations with the Iroquois. The two most important delegates at the conference were Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania and Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts. Reaching agreement on a new Indian treaty was the easy part; for dealing with the French, they proposed creating a federal army, made of troops from all colonies, and sending delegates to a "continental assembly." In addition, a "president-general," appointed by the king, would preside over the army and the assembly, and each colony would contribute money to support the new measures. The plan was passed unanimously by the Albany Congress, but that's as far as it got. King George II rejected it because he didn't want anyone thinking the colonies could take care of themselves, which would be the case here, even if his own man was on the scene. Worse than that, the legislatures in every one of the participating colonies rejected the plan, because they weren't ready to act on their own if it meant giving up some of their freedoms; after all, England had always bailed them out when the going got tough. The only long-term result of the Albany Congress was that some of its ideas were later tried in the Articles of Confederation.(29)

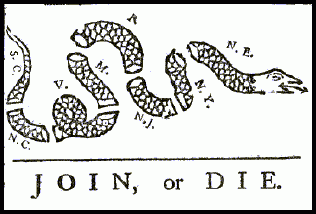

Benjamin Franklin promoted unity among the colonies at the Albany Congress by publishing the first political cartoon in American history. He left Delaware and Georgia out of the cartoon because he did not expect them to participate.

Since the colonies were unable to get the French out of the Ohio valley, London would have to do it for them. In early 1755 the British government sent two regiments of soldiers, the famous "Redcoats," for this purpose, led by General Edward Braddock. Landing in Virginia, they immediately found they had a problem; how were they going to transport all their equipment, which included ten heavy cannon? Virginia could not spare enough wagons to haul that stuff into the backwoods, but Benjamin Franklin was on the scene, and he supplied the needed wagons from Pennsylvania. Once the wagons were loaded, the soldiers began marching to Fort Duquesne; Washington volunteered to go as one of Braddock's aides. Braddock and his men were experts at European-style warfare--marching in a straight line, keeping in a disciplined formation, and engaging in the sort of maneuvers that look good on a parade ground. This caused them to blunder into a trap at the Monongahela River, where the French and Indians shot from behind the rocks and trees, wiping out a larger, better armed British force. Three fourths of the British officers were killed or wounded, including Braddock, who was mortally wounded and died during the retreat that followed. The French captured the heavy cannon, and would use them against the British in future battles. Washington took charge when Braddock fell, and led enough survivors to safety that people started calling him the "Hero of the Monongahela."(30)

In 1756 the rulers of Europe found something to fight over--a rematch between Maria Theresa of Austria and Frederick II of Prussia, the two main antagonists from the previous war. Thus began the Seven Years War. The French took the side of Austria, while the British sided with Prussia, thereby turning the French and Indian War into a North American theater for another European war. Despite this expansion, George Washington remained the only British hero for a while. In North America the French continued to win the battles, though they were outnumbered almost every time. The French captured Fort Oswego in 1756, and Fort William Henry, another fort in upstate New York, in 1757 (the latter battle was the setting for The Last of the Mohicans, the famous novel by James Fenimore Cooper). They also turned back another attempt on Fort Duquesne in 1758. Most humiliating was the battle of Carillon (Fort Ticonderoga), in which the French commander, Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, defeated a British force five times larger than his own. The problem was that the war was being waged in so many places (North America, Europe and India, plus some side shows in South America, Africa and the Philippines), and British forces were spread thin in most of those places. The Indian front didn't need help after the British won a tremendous victory there in 1757 (the battle of Plassey), so the question was whether to concentrate available forces in North America or Europe.(31)

The battles of the French and Indian War.

That question was answered when William Pitt the Elder became Britain's Secretary of State in 1757. An ardent imperialist, Pitt believed North America should be the priority, so he subsidized the Prussians to keep the French busy in Europe, used the British navy to prevent French reinforcements from getting across the Atlantic, and gave Britain's troops in the colonies all that they needed, including leadership. The French, on the other hand, were now overextended, and couldn't go any further unless they captured some British cities. As a result, the tide turned against the French in the second half of 1758. The British counterattack began with four assaults, three by land and one by sea. One of the armies marched on Fort Duquesne (again); a second made another unsuccessful attempt to take Fort Ticonderoga; a third recovered Fort Oswego and went on to take the nearest French forts, Fort Niagara and Fort Frontenac. The main force, the one traveling by sea, went to Cape Breton Island and took Louisbourg, the French fort that promised so much but failed to deliver. This left New France wide open to the next attack, so the French began recalling their garrisons beyond the St. Lawrence valley to defend Montreal and Quebec.

At this time, Washington was with the force marching on Fort Duquesne. He had been in three battles by now, one victory and two defeats, so he didn't have much reason to think this expedition would succeed--but this far into the wilderness, he didn't hear what was happening on the other fronts. They found Fort Duquesne deserted, because the French had gone back to Canada.(32) Of course this was what Virginia had wanted all along, but George Washington was a man of action. For him this was such a disappointment that he resigned his commission, married a wealthy widow, Martha Custis, and retired to an estate at Mt. Vernon, which grew so large in the 1760s that Washington found the job of managing it to be not too different from managing an army.

In 1759 the British force at Louisbourg was ready to move on Quebec. Sailing up the St. Lawrence River, the fleet and its regiments spent all of July and August looking for a way to get through the rapids and enemy defenses, before choosing to land at the base of a cliff. They scaled the cliff and managed to capture a French camp on the top, a plateau known as the Plains of Abraham (after the owner of the property, one Abraham Martin dit L'Écossais). The French, led by General Montcalm, sallied forth to meet the British, a move uncharacteristic of Montcalm since he had won his other battles by waiting for the British to come to him. They fired their first volley at too great a distance to have much effect, though they managed to kill the British commander, General James Wolfe. The rest of the British soldiers held their fire until the French were 40 yards away before cutting loose with their own, in what has been called "the most beautiful volley in the history of warfare." The survivors of the charge that followed fell back to Quebec; Montcalm, himself mortally wounded, told those who saw him stagger into the city that the wound was nothing, but he died the next morning. The British surrounded Quebec, and it surrendered to them five days after the battle.

The remaining French forces in Canada tried to take back Quebec at the battle of Sainte-Foy, in April 1760. Although the British lost more men, technically making this the last French victory in the war, the French failed to fight their way into Quebec. Then the British converged on Montreal from three directions (Quebec, Fort Ticonderoga and Lake Ontario). When they captured that city, the war was as good as over.

It didn't end, however, for a few more years, because of activities on other fronts. In the mountains of the western Carolinas and north Georgia, the Cherokee Indians were pro-British, having signed an alliance treaty in 1754. They fought on the same side in the early years of the war, but had a falling out in 1759, when a hundred Cherokee, traveling with a Virginia expedition against the Ohio Shawnee, lost their provisions while crossing a river and were abandoned by the Virginians. The Cherokee responded to this faithlessness by stealing some of the Virginians' horses, and their white "allies" struck back, killing twenty. Then other outraged Cherokee warriors began attacking white settlements in South Carolina, leading to the "Cherokee War" (1760-62). This rampage quickly expanded beyond the ability of the local militia to control it, forcing the governor to call on General Jeffrey Amherst, the highest ranking British officer in North America, for help. Because France was out of the game, the entire British army in North America was now available, but it took nearly two years to grind the Cherokee into submission, and even then they only gave up because their food supply for the upcoming winter had been destroyed, putting them in danger of starvation if the war continued.

Meanwhile, France persuaded Spain to enter the war on the French side. Spain's motivation was revenge for nearly 200 years of humiliation at the hands of the British, so she declared war on Britain in January 1762. Instead, Spain got more humiliation, as the British navy simply added Spanish colonies to the list of overseas targets; British naval expeditions took Havana in Cuba, and Manila in the Philippines (both in 1762). Finally, the French tried invading Newfoundland, which ended in a defeat for them (the battle of Signal Hill, 1762). By then the war was winding down in Europe, and the Treaty of Paris was signed on February 10, 1763.

The terms of the treaty showed what a lopsided victory it had been for Britain; indeed, the British gained so much land that they acted uncommonly generous with it, and allowed Spain to come out of the war with more land than she had going in. The British took Canada and the part of Louisiana east of the Mississippi from France, and the provinces of East and West Florida from Spain.(33) However, the part of Louisiana between the Mississippi and the Rockies was too large and too far away for the British to manage effectively, so they did not object when France handed it to Spain instead of to them. They even let Spain have New Orleans, though it was on the east bank of the Mississippi and thus part of West Florida; they were so happy to get rid of the French that they ignored technicalities like this. In a nutshell, North America was roughly divided into two equal parts, with Britain ruling the north and east, and Spain ruling the south and west.

The French got to keep Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, two islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, so that they could continue fishing at the Grand Banks, and the British returned Guadeloupe, Martinique and Saint Lucia, which had been captured in the war's Caribbean battles. The truth of the matter was that the French didn't miss Canada and Louisiana as much as those three islands; in fact, France's Caribbean colonies had more people, and generated more revenue, than their Canadian colonies ever had.

Pontiac's Rebellion

Life became more difficult for the Indians after the French and Indian War, even if they had fought on the winning side. Now that the French were gone, the British no longer needed the Iroquois to help defend the frontier, so Anglo-Iroquois relations cooled. General Amherst didn't like any Indians, friend or foe, and reduced the gifts and provisions that had previously been given to them, because he considered this to be bribery. What really hurt was that this cut off many Indians from supplies of gunpowder and ammunition, two products that they needed for hunting but could not make themselves. Also, some farsighted Indians must have wondered what would happen to them and their land, now that they could no longer play the European powers against each other. The British had exterminated or driven out most of the tribes east of the Appalachians; were the Indians west of the Appalachians about to suffer the same fate?(34)

For Pontiac, a leader of the Ottawa tribe, the answer to that question was yes, and he figured that a good offense would be the best defense. On April 27, 1763, several tribes in the Great Lakes region met at a spot now called Council Point Park, ten miles south of Fort Detroit, and there Pontiac called for each tribe to attack the nearest British fort; he would set an example by personally leading the attack on Fort Detroit. Once they had captured the forts, they would proceed to drive the British off the continent, and then, since they needed to buy gunpowder from somebody, they would invite the French to come back.

There were fourteen British forts west of the Appalachians, of which the most important were Forts Pitt, Detroit, and Mackinaw, and all of them came under Indian attack in May 1763. However, it is not clear how the Indians were organized; did they really follow a coordinated plan after Pontiac adjourned the meeting (some history books call the war "Pontiac's Conspiracy," because the Indians used infiltration and surprise attacks to their advantage), or was it every tribe for itself? Since the Indians were illiterate and did not keep written records, and white men were not present at all of their meetings, we can't know everything that they agreed to do. Moreover, we aren't sure how widespread the "conspiracy" was. It started with the Ottawa and the Ojibway tribes in Ontario, and the Potawatomi of Michigan; later on the Miami of Indiana and the Huron joined it, when it looked like Pontiac was going to win. There were also rumors of other tribes getting involved, in the Mississippi and Ohio valleys, but if they supported the uprising, most of them did not take part in any raids or battles. Finally it appears that while Pontiac may have started the rebellion, he had no control over it afterwards, except for his own attempt to capture Fort Detroit. In Chapter 1 we noted that most Native Americans value their freedom too much to submit to a single leader, so Pontiac could not have been a dictator or a "generalissimo," from the European point of view.

Anyway, eight of the British forts fell, and their garrisons were massacred. A ninth fort, Fort Edward Augustus in Wisconsin, was abandoned because it was too remote to keep supplied. However, the Indians failed to capture Forts Niagara, Pitt, Ligonier, Bedford, and Detroit, though Detroit was under siege for five months. There was an early example of germ warfare at Fort Pitt, where the fort commander called for negotiations with the besieging Delaware tribe, because more than 200 women and children were trapped in the fort, and he gave the Indians blankets infected with smallpox, starting an epidemic among the attackers. By the end of summer, Indian warriors, who never believed in long wars and were running low on ammunition, began drifting back to their villages, allowing the British to reestablish control in 1764. Pontiac himself agreed to a peace treaty on August 17, 1765, and traveled to Fort Oswego to confirm it in 1766.

Pontiac was willing to talk peace because the uprising had made the British reconsider their Indian policy. As early as August 1763, London recalled General Amherst and replaced him with General Thomas Gage, who believed in trying diplomacy first. London also issued a proclamation in 1763 declaring that all land west of the Appalachians belonged to the Indians; the old "sea to sea" provisions in the colonial charters were voided. What's more, the west would be a true reservation; the Indians wouldn't be allowed to sell their land if they wanted to. This meant that the only territories still open to white settlers were Florida and the part of Canada north and east of Lake Ontario, because Britain had not claimed those areas before 1763.

If the colonists did not make much of a fuss over these restrictions, it is because they didn't think they were permanent; borders had been drawn between European and Indian lands before, and none of those borders lasted more than a few years. The colonists felt differently, however, when Parliament passed the Quebec Act in 1774. This expanded the borders of Quebec to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, restored the French tradition of private law, and declared Catholicism to be the official religion of the province; French Canadians could now participate in the government of their colony. From the settlers point of view, London was giving the lion's share of their newly won land to the enemy they had so recently defeated, and this enemy belonged to the church they feared the most! Fortunately for them, this act did not go into effect (if it had, the entire Midwest -- Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin and eastern Minnesota -- would now be part of Canada), but it succeeded in pacifying the French. The main results of the Quebec Act were that it kept French Canadians loyal when the American Revolution broke out, and the act provided one of the more obscure grievances Thomas Jefferson wrote down in the Declaration of Independence.

One more minor war took place before the American Revolution, this time between the Virginia Militia and the Native Americans along the Ohio River. This conflict was brief, lasting from April to October of 1774, and is called Lord Dunmore's War, because the leader on the Virginia side was the current governor, John Murray, the 4th Earl of Dunmore. The land in question was the westernmost part of Virginia, today's West Virginia and Kentucky. No Indians lived here, because two tribes, the Shawnee and the Cherokee, had a treaty where they shared this land as a hunting ground between them. Of course the settlers moving into this area didn't recognize such a treaty, and the Virginia Militia was sent in "to pacify the hostile Indian war bands." On the other side, the Natives fighting were mainly from two tribes, the Shawnee and the Mingo. The decisive battle was fought at Point Pleasant, on the upper Ohio River in West Virginia. Virginia's casualties were higher (75 Virginians killed vs. 41 Natives killed), but the Militia prevailed in driving the Native Americans out of the area. Shortly after that, the Shawnee leader at the battle, Cornstalk, was forced to agree to the Treaty of Camp Charlotte, where the Shawnee gave up all of their claims to the lands south of the Ohio River. Not all Indians accepted this loss, though, and some would try to take the lands back, during the Revolution and the years immediately after it, by fighting on the side of the British against the settlers.

Causes of the American Revolution

The aftermath of the French and Indian War caused the British and the colonists to take a new look at their relationship. London did this because new people were in charge: George II had died and was succeeded by his grandson, George III, in 1760. George III was the first native-born king of England in half a century; the first two Georges came from the German state of Hanover, and because neither spoke good English, they had to let Parliament manage the country for them. He also had high but impractical ideas of kingship. His mother had admonished him, saying, "George, be a king," so he tried to be a king with real power, unlike his predecessors. At first his goals were simple: to rule without depending on political parties, to banish corruption from political practice, and to ignore German politics, which had dragged Britain into the last two European wars. He removed William Pitt and everyone else from the old administration, because he didn't trust them, and packed Parliament with friendly members, known as the "king's friends," until they had a majority in the House of Commons. George III never completely became an autocrat in the sense that his opponents contended (and he certainly does not look like a tyrant, when you compare his record with Napoleon, Hitler, Stalin, Mao, etc.), but he always made sure that people knew his point of view on the issues. He also didn't have the mental stability to rule as an autocrat; there were occasional bouts of insanity at this stage, and after 1800 he was completely mad, spending much of his last twenty years wondering how the apple got into the dumpling.

As for the Thirteen Colonies, it was clear that they had grown up. Two million people now lived there, who could grow and manufacture almost anything they needed, and they had reached a stage where they were starting to produce their own art and literature. Over the years, the people in the colonies had four enemies that they feared more than any other: the French, the Indians, black slaves, and the mother country's government. Well, the recent war got rid of the French, and because there were more white men than red men north of the Rio Grande, the Indians weren't much of a threat anymore; even during Pontiac's Rebellion, major cities like Boston, New York and Philadelphia weren't in danger. As for the slaves, there were not yet enough of them to make slaveowners worry much about slave revolts; that danger would come after the nineteenth century began. That left the British government as the biggest potential threat to their way of life. During the war the number of Redcoats in the colonies increased, from 3,200 in 1754 to 8,000 in 1765. London justified keeping them through Pontiac's Rebellion by claiming they were needed to protect the colonies. However, the colonists did not believe the French would come back, and most of the ranger units, which were best suited for fighting the Indians, were disbanded after 1763. The remaining Redcoats were garrisoned in the cities; some colonists suspected they were not really there for defense.

Wars are an expensive business, even for the winners, so after the French and Indian War, the government of England looked for ways to cut expenses and replenish the treasury. One way was to make the colonies pay a bigger share of their upkeep, now that they could afford to do so. In all the wars up to this point, the colonies had raised their own militias, but otherwise contributed nothing toward their defense. For this purpose the new prime minister, George Grenville, suggested some new taxes, with the goal of raising £100,000 a year. This seemed like a fair amount because London was currently spending three times as much on the colonies, and American taxes were only 1/26 as high as those in England. Accordingly, he first proposed the Sugar Act in 1764, which put a duty on molasses, at three pennies a gallon. But this only raised £45,000 in the first year, so in 1765 he proposed the farther-reaching Stamp Act to come up with the rest. Under this law, every legal document, permit, contract, newspaper, pamphlet, and even playing cards would have to carry a stamp, showing that the tax had been paid. Parliament unanimously passed the Stamp Act on March 22, 1765, and it went into effect later that year, on November 1. Again, Englishmen had paid this kind of tax for a while, so Grenville didn't expect much opposition to it.

The colonists, however, saw the matter differently. Not only was the Stamp Act expensive for those who used papers a lot, such as newspaper publishers and lawyers, but complying with the act generated much additional work. Even worse, some colonists didn't like the principle behind the thing. Englishmen could be taxed by Parliament, where they had elected representatives in the House of Commons, and colonists could be taxed by their elected representatives in local legislatures, but this was the first time that the colonists had a tax directly imposed on them by Parliament. The colonists had no representatives in Parliament, because it wasn't feasible to send any across the ocean, but the idea that any authority could impose a tax without the consent of the governed seemed immoral, and possibly illegal. Politicians like Virginia's Patrick Henry put the feelings of the colonists into words with phrases like "Taxation without representation is tyranny." In October 1765, nine colonies sent delegates to a Stamp Act Congress in New York City, which drew up a list of grievances and sent them to Parliament.

In the end, the Stamp Act was unenforceable. Stamps were often unavailable, and in places where they were available, many colonists refused to buy them. Colonists threatened tax collectors with tarring and feathering, and few collectors were willing to risk themselves to uphold the tax. A riot broke out in Boston, the usual place, where protestors hanged and burned an effigy of the stamp agent, Andrew Oliver, and broke into both his home and his office. Oliver resigned, and nobody would take his place. Similar events occurred in New York City and Charleston, and then colonists did something that really hurt--they began to organize a general boycott of British-made goods, and refused to pay debts owed to British creditors. Before the end of 1765 King George sacked Grenville, and Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in March 1766.

The colonists learned from the Stamp Act protests how strong they could be if they worked together. The British don't seem to have learned as much, because as soon as tempers cooled, they came back with new taxes. Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was still having trouble balancing the budget, so in 1767 he came up with two measures called the Townshend Acts. The first act called for suspending the New York Assembly, because it had not complied with a law that required the colonies to provide quarters for British soldiers. The second one, called the Revenue Act, imposed customs duties on colonial imports of glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea. In addition, new measures were enacted to crack down on smugglers, who brought cargoes to the colonies without paying taxes on them first. This had to be done, because it was estimated that most of the tea drunk in Boston, New York and Philadelphis was smuggled; once the tea was unloaded from the ships, there was no way to tell if it was legal or not.

The new laws and taxes were quite legal, since previous legislation had given the government monopoly rights over trade with the colonies. Despite this, they were nearly as unpopular as the Stamp Act. Also, in a fit of absentmindedness, the main customs house for collecting these taxes was placed in Boston, where trouble was most likely to happen. Sure enough, riots broke out in Boston in 1768, prompting the crown to dissolve the Massachusetts legislature and move in troops to protect the customs house. Once the Redcoats were there, the British realized, too late, that they were in a sticky situation; they needed to defend the king's property, but nobody on either side wanted to see a standing army grow large enough to become a danger to the liberties of the people. The expected clash came on March 5, 1770, when a crowd of men and boys threw snowballs at a sentry in front of the customs house. Other British soldiers came to support the sentry, the crowd grew larger and started throwing anything they could pick up, and the soldiers fired into the crowd, killing five.

Patriot leaders like Samuel Adams were quick to point to this incident, the "Boston Massacre," as an example of British tyranny. Similar events in other times and places have started revolutions, so why didn't the American Revolution begin here? Well, neither side felt ready for a war at this point, so cooler heads managed to defuse the crisis. When the British soldiers responsible were arrested and tried for murder, two prominent Patriots, John Adams and Josiah Quincy, successfully defended them, after other Boston lawyers refused to take the case. And it now appears that Samuel Adams didn't want an uprising if it looked like a lawless rabble was behind it. As for the British, they removed the troops and canceled most of the Townshend Acts, leaving only the tax on tea, to make a point that the government had a right to tax commerce.

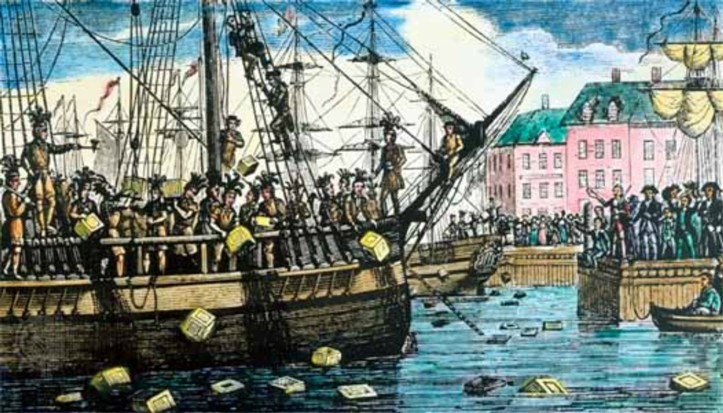

During the next three years there was optimism for improving relations between England and the colonies, which hurt Samuel Adams. Still, even the tea tax was unacceptable to some Patriots. They called for a tea boycott, and the British responded by giving the British East India Company permission to deliver its tea directly from Asia to the colonies, without stopping in England first. This brought down the price of legal tea until it was cheaper than the untaxed tea of the smugglers. When Company ships loaded with tea arrived in the colonies, most ports turned them away, so they landed in Boston, where the governor thought the British navy could protect them. This gave Samuel Adams an opportunity for a disciplined demonstration, and on the night of December 16, 1773, an estimated 150 Patriots disguised themselves as Indians, boarded three ships, broke open the tea chests, and threw the tea overboard (see below).

- The Massachusetts Government Act did away with elections and made nearly every office in the colonial government an appointed one.

- The Administration of Justice Act did away with the local justice system, forcing trials to be held in England or another colony, and requiring bail for any person accused of a "capital crime in the execution of their duty." Together, #1 and #2 effectively put Massachusetts under martial law.

- The Boston Port Act ordered Boston's port closed until the destroyed tea shipment was paid for.

- The Quartering Act ordered the colonies to provide quarters for British soldiers if there weren't enough barracks. This would eventually lead to the Third Amendment in the US Constitution.

London hoped that the other colonies would ignore the punishment of Massachusetts, but Samuel Adams and John Hancock, the businessman who financed Patriot activities in Boston(35), had formed "Committees of Correspondence," Patriot cell groups across Massachusetts that kept in touch with each other through letters. Now they let the committees know what was going on in Boston, and the committees contacted Patriots beyond Massachusetts, making arrangements for a meeting that would involve representatives from all British colonies in North America. The result was that fifty-five delegates, representing twelve colonies, met in Philadelphia for the First Continental Congress, which was in session from September 5 to October 26, 1774. In addition to the usual speeches made at a convention like this, the Congress called for a boycott of British goods and a halt on exports to Britain if the "Intolerable Acts" were not repealed.(36) Then the delegates declared the Congress a success, made plans for a Second Continental Congress to convene on May 10, 1775, and sent invitations to the colonies that had not attended: Quebec, Prince Edward Island (called St. John's Island until 1798), Nova Scotia, Georgia, East Florida, and West Florida. Before that happened, however, the battles of the American Revolution began, and of those invited, only Georgia would send delegates to the next Congress--the rest refused to break with the mother country.

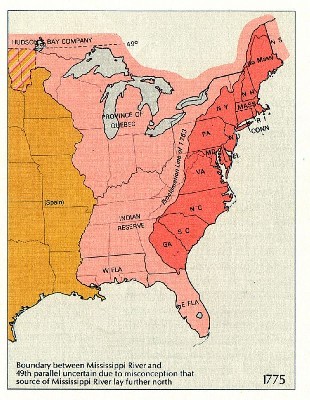

Eastern North America, 1775. The Thirteen Colonies are shown in red, the colonies that stayed with Britain are pink, and the Spanish colonies are orange. Click on the above thumbnail to see the full-size map (Opens in a new window).

This is the end of Part II. Click here to go to Part III.

FOOTNOTES

19. Although this sounds a little like the American Revolution, it isn't even a dress rehearsal for it; the year is 1676, a century too early!

20. Bieber, Ralph Paul, "The British Plantation Councils of 1670-4," English Historical Review, Vol. 40, No. 157 (Jan., 1925) , pp. 93-106.

21. Connecticut refused to submit to Andros until he showed up with troops and ships, in October 1687. The Connecticut governor was thus forced to convene the assembly, and after Governor Andros praised the colony's industry and government, he demanded their charter. As they placed it on the table, people blew out all the candles; when the lights came back on, the charter was missing. According to legend, it was hidden in an oak tree, henceforth known as the Charter Oak, until Andros gave up looking for it, named four men to rule in his place, and returned to Boston.

22. Boston continued to have a reputation as an unruly place for most of the eighteenth century. Two big riots broke out there in 1737 and 1747. And in other years, Bostonians kept in shape with an annual riot on November 5. For the British Empire this was a holiday called Guy Fawkes Day, which commemorated the foiling of a 1605 plot to blow up both the king and Parliament, but in Boston it was "Pope Day"; two mobs, one from the north side of town and one from the south side, would meet in the center of Boston, each mob carrying a dummy of the pope. Then they started brawling, with stones and clubs widely used, and victory would go to the mob which captured or destroyed the other mob's "pope"! The last celebration took place in 1764, and then Samuel Adams came along and decided that the mobs of Boston would be put to better use starting the American Revolution, instead of busting each others' heads on Pope Days. Nowadays Boston is a predominantly Catholic city, so I suppose if anyone tried to bring back Pope Day, he would cause riots for a different reason!

23. William Penn also tried to be fair to the Indians, but not everyone in the colony felt the same way. One notorious example was the so-called "Walking Purchase." In 1686 a treaty was signed with the Delaware tribe that purchased land between the Delaware and the Lehigh Rivers, as far as "a man can walk in a day and a half." In 1737, when it became necessary for surveyors to mark where the actual western boundary was, Thomas Penn (William's son) had a path cleared out, left refreshments at several spots along the way, and hired three athletes, offering a prize to the one who ran the farthest; the winner did 64 miles! Of course the Delaware were furious when they realized they had been cheated, but when they complained to the Iroquois, who they thought would defend their interest, the Iroquois were furious too, because the Delaware had signed a treaty without their permission. Finally the Delaware and the Iroquois brought their grievances before the governor, in a 1742 meeting. When Nutimus, the Delaware chief, rose to protest the Walking Purchase, the Iroquois representative, Canasatego, silenced him by saying, "We conquered you. You are women; we made women of you. Give up claims to your old lands and move west. Never attempt to sell land again. Now get out."

24. I pointed out in Chapter 1 that the New World has a shortage of animals that can do work; the largest are the llamas of Peru. Most Indians without horses used dogs to pull a crude sled, called a travois. Among other things, it became feasible to build larger tepees when horses hauled the poles around.

25. In the early eighteenth century, the Seminoles, a branch of the Creek tribe, migrated into Florida, absorbing the smaller tribes already there, as well as refugees from east coast tribes like the Yamasee. They got along well with the Spaniards and the British, but not with the Americans after the United States was founded. For that reason, the Seminoles took in escaped slaves who made it to their swamps and forests. Later, during the Second Seminole War (see Chapter 3), they recruited several hundred slaves to fight on their side.

26. Seven of the current Lords Proprietor were persuaded to sell the lands they had inherited from their ancestors. The lone holdout was John Carteret, the second Earl of Granville; he agreed to get out of politics but insisted on keeping his share of the land for his family. This tract, defined as all of North Carolina within sixty miles of the Virginia border, became known as the Granville District. It lasted for half a century, until the American Revolution, and it caused considerable confusion because of inaccurate records; settlers in the district could not obtain clear title to any land they tried to purchase. The North Carolina government confiscated the land between 1777 and 1779, and after the Revolution, the Carteret heirs were partially compensated for it.

27. Note that the colonists named each war after whoever sat on the throne of England at the time. This tells us that they saw the conflicts as somebody else's wars, with themselves as minor participants.

28. England and Scotland had been ruled by the same monarch since 1603. In 1707 this union was formalized in a treaty that declared both countries, plus English-ruled Wales and Ireland, members of the "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland." For that reason, after 1707 we refer to Englishmen, Welsh and Scotsmen as British.

One consequence of the new union was a change in the source of immigrants to the New World. Whereas most of the settlers to the English colonies during the first hundred years had come mainly from central and southern England and Wales, from now until the Revolution most of them would be from Yorkshire, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Unfortunately for them, the best farmland, the coastal plains, had already been taken, so the new settlers headed inland, to set up farms in the foothills of the Appalachians. This meant that among those Americans moving west, there would always be a significant Celtic element.

29. Benjamin Franklin said this about the Albany plan in 1789: "On Reflection it now seems probable, that if the foregoing Plan or some thing like it, had been adopted and carried into Execution, the subsequent Separation of the Colonies from the Mother Country might not so soon have happened, nor the Mischiefs suffered on both sides have occurred, perhaps during another Century. For the Colonies, if so united, would have really been, as they then thought themselves, sufficient to their own Defence, and being trusted with it, as by the Plan, an Army from Britain, for that purpose would have been unnecessary: The Pretences for framing the Stamp-Act would not then have existed, nor the other Projects for drawing a Revenue from America to Britain by Acts of Parliament, which were the Cause of the Breach, and attended with such terrible Expence of Blood and Treasure: so that the different Parts of the Empire might still have remained in Peace and Union." In other words, he thought that the colonies would have gained independence peacefully, around the same time that Canada did. A Dominion of North America, perhaps?

30. Washington cheated death so often in battle, that many Americans believed God was protecting him. At the battle of the Monongahela, Washington had two horses shot out from under him, and later he found four bullet holes in his coat, though none of the bullets had touched him. Later on, in the American Revolution, Washington rallied his troops at the battle of Princeton (1777), by putting himself and his horse in front of the Americans, with the British just thirty yards away. He was an obvious target, but when the British fired at him, they all missed, so the Americans stood firm long enough to win the battle. On still other occasions he narrowly missed getting shot by snipers. Unfortunately his extraordinary luck did not extend to the people around him, as Braddock found out the hard way!

31. In 1755, when it looked like the French were going to win, the British decided to deport Nova Scotia's 6,000 French-speaking residents, scattering them all over the other colonies. Many of them eventually found their way to Louisiana, becoming the Cajun (Acadian) community of today.

32. Fort Duquesne was renamed Fort Pitt by the British, and after the American Revolution it became the city of Pittsburgh.

For what it's worth, the site of the battle where Washington fired the first shot, and where Jumonville was killed, is now the location of a Christian summer camp, in southwest Pennsylvania. The conflict started here grew into a world war, with battles on five continents, but the main landmark is an eighty-foot-tall cross, rather than a war memorial. And while the Indians with Washington scalped Jumonville, scalping is not one of the wilderness skills taught to the young people who come to the camp each year!

33. Most of the modern state of Florida (the peninsula), was called East Florida back then. West Florida included not only the Florida Panhandle but also the southern third of Alabama and Mississippi, and the part of Louisiana around Lake Pontchartrain. British surveyors marked the territory's northern frontier at latitude 32o 28'.

34. Currently we estimate that in 1492, approximately 120,000 Indians lived in the land that would become the Thirteen Colonies. By the time of the French and Indian War, this figure had dropped to 20,000. The only tribes left that had more than a few hundred members apiece were the Cherokee and the Iroquois. The rest had moved west, or simply died. Sometimes when a tribe got too small to keep on going, its members would join a larger tribe; that's why the Cherokee and the Iroquois did better than the others. Later on, the American Revolution would split the Iroquois Confederacy; the Seneca and the Tuscarora supported the Patriots, while the other four nations stayed pro-British.

35. John Hancock had been a smuggler as well as a merchant. Bostonians joked that "Sam Adams writes the letters and John Hancock pays the postage."