| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A General History of the Middle East

Chapter 16: THE ARAB-ISRAELI CONFLICT SINCE 1948

This chapter covers the following topics:

Israel's War of Independence

At midnight on May 15, 1948, armies from Egypt, Syria, Transjordan, Iraq, Lebanon and Saudi Arabia invaded Israel. They advanced rapidly, threatening to destroy the one-day-old state, and drive the Jews into the sea. The Egyptians moved in two columns; one went up the coast as far as modern Ashdod, while the other moved into the Negev, taking Beersheba and Hebron. The Syrians and Lebanese besieged Jewish settlements in Galilee, where the Israelis resisted bitterly, despite grave shortages of arms and men. The Iraqis occupied the hills of Samaria, taking strategic points at Tulkarm, Jenin, and Nablus. Transjordan's Arab Legion, easily the best of the Arab armies, advanced as far as Latrun, cutting the Tel Aviv-Jerusalem highway. The Old City of Jerusalem became the scene of a two-week battle, which the Jordanians won. When it was over, some 1,500 Jews surrendered; the men between the ages of fifteen and fifty went to a Transjordanian P.O.W. camp, while the rest walked with small bundles of possessions to Haganah-held West Jerusalem. The city itself was not so fortunate; Jewish homes were torn down; synagogues and Jewish cemeteries were desecrated.

However, this was the end of the Arab winning streak. Coordination between the Arab armies broke down in a matter of days. King Abdullah planned to keep everything the Arab Legion captured for Transjordan; the other Arabs wanted all "liberated" land to go to the Palestinian Arabs. Consequently many participants lost interest when it looked like Transjordan would get the lion's share; Egypt, for instance, would not join forces with Transjordan in the south while it was possible. The Israelis, on the other hand, were fighting for their lives, with their backs to the Mediterranean; they knew if they lost, there would be no second chance. That sense of desperation caused them to launch successful counterattacks at the end of May. Then the UN sent a representative, Sweden's Count Folke Bernadotte, to negotiate a truce, to which both sides gladly agreed.

The truce ran from June 11 to July 9; during that time nobody complied with its conditions. The Israelis took full advantage of the time to bring in arms and ammunition, mostly from Czechoslovakia. When the truce ended the Israelis were better prepared and organized, and launched a series of night attacks on all fronts. During the next ten days the road to Jerusalem was cleared, and Nazareth and Lod(1) were taken. Then another UN-sponsored truce went into effect, which lasted longer than the first: July 18 to October 15. Again both sides used the time gained by the truce to move men and get more supplies; again the Israelis did better at both, since the Arabs were suffering from disorganization and the growing flood of refugees into their territory. In September Count Bernadotte was killed by a Sterngang gunman, who thought he had been a Nazi sympathizer during World War II. An American, Dr. Ralph Bunche, succeeded him. The Israeli government immediately denounced the assassination, and ordered all armed factions not under its control to disarm; consequently Menachem Begin stopped being a terrorist leader and joined the opposition to the Labor Party in Israel's parliament, the Knesset.

The third round of fighting began with two Israeli offensives: "Operation Hiram" in Galilee and "Operation Ten Plagues" in the Negev. Both were complete successes. By the end of October the Israelis had not only secured the upper Galilee but advanced five miles into Lebanon. In the south, "Operation Ten Plagues" surrounded Egyptian forces at Faluja and Hebron, and forced the rest of the Egyptian army to fall back toward home. The Israelis followed into the Sinai, until international pressure compelled them to stop. They withdrew in January 1949, and signed a cease-fire agreement with Egypt the following month.

Israel signed similar cease-fire accords with Lebanon in March, and Syria and Transjordan in July; the Iraqis and Saudis never signed any agreement, but they did go home. Gaza came under an Egyptian military administration, which was expected to last until a Palestinian Arab state could be set up. Transjordan annexed its territorial gains (Judaea & Samaria, from now on known as the West Bank, plus East Jerusalem) and renamed itself the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan; the other Arabs did not recognize this annexation. Israel was the biggest winner, not only surviving its most severe test but emerging with 21% more land than the UN had given it. Between November 1947 and January 1949 the Israelis lost 4,000 soldiers and 2,000 civilians (about 1% of the total Jewish population); the total Arab casualty count has never been revealed.

The absence of fighting does not always mean peace. Abdul Rahman Azzam, the secretary-general of the Arab League, explained the Arab strategy with these words: "We have a secret weapon which we can use better than guns and machine guns, and that is time. As long as we do not make peace with the Zionists, the war is not over; and as long as the war is not over there is neither victor nor vanquished. As soon as we recognize the state of Israel, we admit by this act that we are vanquished."

Egypt and Syria sponsored teams of Palestinian guerrillas known as Fedayeen ("sacrificers"), to continue the war on a small scale until the frontline states were ready for the next round.

An Exchange of Arabs for Jews

One aspect of the 1948-49 war that still affects us today is the departure from the land of hundreds of thousands of Arabs. Sometimes they simply fled the fighting, in other cases they were driven out by groups like the Irgun. However, most left because Arab leaders said they wanted a clear field of fire against the enemy. An Arab victory was an absolute certainty, they argued, and after the war ended they could come home and have the whole land to themselves. But because the war ended in a Jewish victory, most of the Palestinian Arabs found themselves without a country. When Israel declared independence, its government had stated that those Arabs who wanted to stay were welcome, but those who left would not get a second chance. The Arabs who stayed (plus a few that managed to return after the war) numbered 160,000 by the end of 1949, most of them in the hills of Galilee. This group, known as the Israeli Arabs, enjoys full rights as Israeli citizens, including the right to vote. We rarely hear from them in the West, however, because those Palestinians committed to the destruction of Israel have always claimed to represent all Palestinians, and have a nasty habit of assassinating Arabs who openly disagree with them.

The UN estimated that more than 725,000 Arabs fled; the Israelis estimated that between 550,000 and 600,000 Arabs fled. One reason for the discrepancy is the little-known UN definition of what a "Palestinian" is: anyone who has lived within the land for at least two years. This means that some Arabs who claim to be "Palestinians" were never actual citizens of Palestine when it was under British rule; they were immigrants from other Arab countries who may have arrived as recently as 1946. Whatever the case, they all now claim to be citizens of Palestine, and the Arab governments treat them as refugees from there.

Simultaneously Israel had to deal with a tidal wave of Jewish refugees coming in. So many arrived, in fact, that it is remarkable the Israeli economy did not collapse under their weight. To start with, 600,000 Jews, most of them holocaust survivors, came from Europe between 1948 and 1970. Another 60,000 came from Iran and 20,000 from India. About 100,000 came out of the Soviet Union in the early 1970s, before the USSR put severe restrictions on that kind of immigration.

Most important to Israel's future, however, was the arrival of the Sephardic Jews. In 1945 there were more than 870,000 of them living in the Arab world; some of their communities had existed for 2,500 years. For them life in harmony with their Arab neighbors ended with Israel's independence, because the Arabs now saw them as enemy agents. In 1947 and 1948 there were anti-Jewish riots in Aden (where 82 Jews were killed), in Egypt (where 150 Jews were killed), in Libya (where 14 Jews were killed as a follow-up to a savage 1945 pogrom), in Syria (where Jewish emigration was forbidden), and in Iraq (where "Zionism" became a capital crime). Fleeing their persecutors, the Jews were forced to abandon their property and possessions, and most of them escaped with nothing but the clothes on their backs. About two thirds of them became Israeli citizens, while the other 260,000 found refuge in Europe and the Americas.

The transfer of populations on a massive scale, either by war or by state policy, is a distinctive feature of twentieth century history. In almost every case, those uprooted from one place found a new home in the country that took them in. The movement of more than 580,000 Jews from the Arab lands to Israel, and of a similar number of Palestinian Arabs out of Israel, was typical of such movements, though it was far from being the largest (e.g., compare it with the exchange of 8.8 million Hindus for 8.5 million Moslems that took place between India and Pakistan at the same time). Still, the uprooted Jews became an integral part of Israeli life, while the Palestinian Arabs remained, often as a deliberate act by their host countries, isolated, neglected, and bitter.

In 1975 the Iraqi government invited all former Iraqi Jews to come back, to prove that the Arabs are not racists. Only one ex-Iraqi is known to have accepted the invitation. When Iraqi officials told Western reporters in Baghdad that a trickle of Iraqi Jews had returned, the reporters started calling Yusef Navi "Mr. Trickle." After a year in Iraq, Navi re-emigrated to Israel.

The world at large forgot the handful of Jews that remained among the Arabs. As of 2009, there are an estimated 4,000 Jews left in the Arab world--most of them in Morocco, Tunisia and Yemen--and they were an unfortunate lot. As dhimmi (second-class citizens), their ability to travel is severely restricted, they have to pay special taxes, and they are subject to discriminatory laws. Four hundred stayed in Yemen, for instance, because they belonged to a Satmar, a non-Zionist sect. When Moshe al-Nahari, a thirty-year-old teacher, was killed in 2008 by a Moslem who was religiously motivated, and the judge ordered the murderer's family to pay "blood money," instead of passing a death sentence, the last Jews of Yemen realized that the Arab world does not tolerate even non-Zionist Jews, so they began to leave.

An unfortunate side effect of the Jewish departure is that except for the Palestinians, few modern Arabs are likely to meet a Jew in their lifetime. Because separation breeds prejudice, and prejudice breeds more separation, this makes the Arabs more susceptible to the anti-Semitism and crackpot conspiracy theories so common among Islamic fundamentalists.

The Syrian Dictators and Jordan's King Hussein

The Soviet Union supported Israel in the 1948-49 war. This sounds strange to modern ears, but at first the USSR found Israel more appealing than its Arab opponents; since many of modern Israel's founders came from a socialist background, some thought that the Jewish state would align itself with countries of a similar ideology, namely the Soviet bloc (American conservatives didn't want to support Israel for the same reason). Furthermore, the Soviets found nothing appealing about the Arab governments, most of which were conservative monarchies. However, the old Russian tendency toward anti-Semitism did not go away under communism, and that killed whatever moves they made to improve Soviet-Israeli relations. After Stalin's death in 1953, his successors were more flexible when it came to choosing friends in the Third World.

They found the Arabs quite willing to forgive and forget, since many Arab governments had been discredited by their humiliating defeat in the first Arab-Israeli war. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Syria. In March 1949 Syria's first president, Shukri al-Kuwatli, was overthrown in a coup led by a Kurdish officer, Colonel Husni az-Zaim. Highly unpopular, Zaim was himself overthrown in August by another colonel, Sami al-Hinnawi. A third coup, led by Colonel Adib ash-Shishakli, followed in December; in November 1951 Shishakli used a fourth coup to remove his associates.

The Syrian dictators had no special commitment to any ideology, and ruled in association with veteran politicians. The officers under them, however, were members of either the Baath party or the PPS. They came to power in February 1954 when Colonel Faisal al-Atasi overthrew Shishakli and restored Parliament. The PPS was suppressed in the following year; from that time on the Baathists had no serious rival.

Meanwhile, there was a change of kings in Jordan. In July 1951 King Abdullah went to pray in Jerusalem's al-Aqsa Mosque and was shot by a Palestinian nationalist. The king's grandson, sixteen-year-old Hussein, was also a target, but his life was saved when one of the medals he wore stopped the bullet intended for him. Abdullah's son Talal was crowned first, but one year later he was declared mentally ill and replaced by Hussein. Hussein inherited an unstable throne, and was criticized in Egypt and Syria for his British connections, until he dismissed Glubb Pasha in 1956. British support for the Arab legion was withdrawn when that happened, and Hussein turned to wealthy Arab states, particularly Saudi Arabia, to provide the subsidies needed to keep Jordan solvent.

Hussein's 46-year reign was the longest in modern Middle Eastern history. Part of this was due to his extraordinary luck, which saw him through many assassination attempts; he also chose the safest course on most political issues, and was skilled at keeping his opponents divided. Paradoxically, he may also have gotten help from Jordan's poverty; there is no great source of wealth like the oilfields of the Persian Gulf for anybody to claim if the Hashemites get overthrown some day. Furthermore, the thought that Israel could intervene to prevent the creation of a hostile Palestinian state on the East Bank restrains anti-Hashemite groups. Finally Hussein enjoyed the support of the Bedouins, who are predominant in the army.

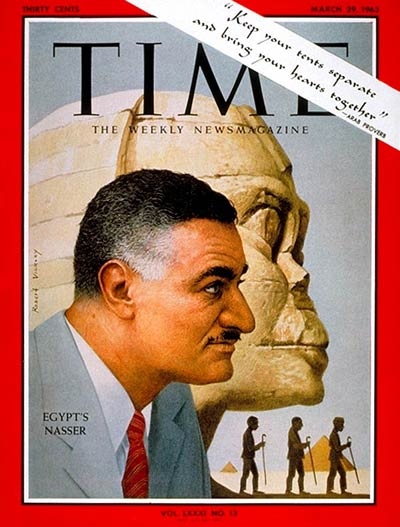

The Rise of Nasser

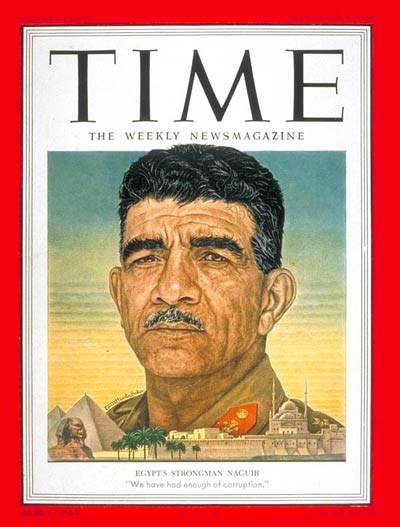

The 1948-49 war was a complete disaster for Egypt. Food and medical supplies were inadequate and irregular; arms were obsolete; the senior officers were incompetent and sometimes cowardly (a notable exception was Major General Mohammed Naguib, who along with Gamal Abdel Nasser, was wounded in the fighting). One Free Officer, Colonel Ahmed Abdul Aziz, told his associates what to expect, shortly before he was killed in battle: "Remember, the real battle is in Egypt."

After the war both the Free Officers and the Moslem Brotherhood gained hundreds of new members. The government tried to divert attention away from its own shortcomings by whipping up another anti-British campaign. It announced plans to terminate the 1936 treaty and encouraged the Moslem Brotherhood to carry out guerilla attacks against the 80,000 British soldiers still stationed in the Suez Canal zone. In January 1952, the British stormed a police station suspected of harboring guerrillas, and some fifty Egyptian policemen were killed. In response, a mob went on a rampage in Cairo, attacking buildings with foreign connections. By the time order was restored, 26 foreigners (mostly British) had been killed and much of the city's center had burned down.

The Free Officers decided this was the time to act. Six months later, on July 23, 1952, they seized power in a coup. They initially installed Mohammed Naguib as president, since he was a hero to the Egyptian people, but from the start Nasser was the true leader. For the first time in 2,300 years Egypt had a native Egyptian ruler--not someone of Turkish, Albanian, or some other foreign blood--who was not going to submit to a foreign power. Since Nasser did not like bloody revolutions, he allowed Farouk to go into exile, and the 280-lb. ex-king sailed out of Alexandria with a yacht full of gold ingots and pornography. He also had the world's largest coin collection, but that stayed behind because it was too heavy for the yacht; the Egyptian government eventually auctioned it off. Farouk spent his declining years in Italy, finally succumbing to a heart attack in a Rome restaurant (1965).

The world welcomed the Free Officers as a big improvement over Farouk, and they did well at first. Their first acts were to abolish the monarchy and titles of nobility like Bey and Pasha. Then came reforms to improve the lives of the peasants. Landholdings were limited in size to 200 acres, and they redistributed excess land among the fellahin in lots of 2-5 acres. Workers were guaranteed a minimum wage, and the rates which landlords could charge their tenants were sharply reduced. Unfortunately enforcement of these reforms was limited, due to Egypt's notoriously inefficient bureaucracy, and the rapidly growing population canceled many gains. In response, the government proposed a greater project, the construction of the world's largest dam across the Nile River at Aswan, and began looking for outside help to finance this venture.

In April 1954, when Naguib tried to be more than just a figurehead, Nasser swept him aside and took the presidency for himself. Then came a more serious challenge from the Moslem Brotherhood, which had its own plans for Egypt. An assassination attempt on Nasser at a public meeting in October was that organization's undoing. As the bullets whizzed by, Nasser stood there and shouted, "Let them kill Nasser. He is one among many and whether he lives or dies the revolution will go on." The Brotherhood was suppressed, and Nasser's coolness under fire contributed to his wild popularity among the Egyptian people.

Simultaneously, Nasser scored a diplomatic success: a new treaty with Britain. Under the treaty terms, Britain agreed to pull all of its troops from the Suez Canal in twenty months, though they could return in case of war, and both nations agreed to allow passage through the canal to the ships of all nations.

In April 1955 Nasser started secret negotiations which had the potential for bringing a peace settlement between Israel and Egypt. The Quaker representative to the United Nations, Elmore Jackson, carried messages between Nasser, Israeli Prime Minister Moshe Sharett (Ben-Gurion had retired to his Negev farm in 1953), Ben-Gurion, and other Israeli and Egyptian officials. At one point Ben-Gurion said that "Nasser is a decent fellow who has the interests of his people genuinely at heart"; he even offered to meet with the Egyptian president in Cairo. The talks ended in August after they failed to produce results, but as Elmore Jackson pointed out when he revealed the existence of the meetings in 1982, Nasser was the only Arab leader with enough popular support to even consider a settlement with the state most Arabs denounced as "the Zionist entity." Peace would have to wait until another Egyptian leader went to Israel, 22 years later.

The Suez Crisis of 1956

1955 was also the end of the honeymoon between Nasser and the West. Nasser chose not to take sides in the Cold War; he disliked communism, but he also wanted no part of any Western alliance that included Britain and France. Instead, he proposed a third alliance, which would not only include the Arabs but neutral nations like India and Yugoslavia. As he saw it, Egypt was uniquely suited to lead three major blocs of nations, which he called the Arab Circle, the African Circle, and the Islamic Circle. In 1955 he went to the first conference of nonaligned nations, held in Bandung, Indonesia, and there he was welcomed as an equal by other neutral heads of state. Yet to cold warriors like John Foster Dulles, the US Secretary of State, there could be no middle ground in the struggle between East and West. When the West refused to sell him the modern arms he wanted, Nasser looked east and bought Soviet arms from Czechoslovakia. Then he opposed American attempts to stop communist activities in the Middle East, and without warning recognized the communist government of China. Most Americans now felt that Nasser had sold his soul to the devil.

Nevertheless, the Americans were not Nasser's main enemy. The British prime minister, Sir Anthony Eden, hated him with a passion that verged on hysteria. Eden blamed all of Britain's problems in the Middle East on Nasser. When Jordan's King Hussein dismissed Glubb Pasha in March 1956, Eden thought Nasser was behind the firing. He decided that the world was not big enough for both him and Nasser, and began looking for a way to eliminate the Egyptian leader before Nasser could undermine the British government or Britain's position in the Middle East. A few days later, when one of his ministers, Anthony Nutting, tried to persuade Eden to moderate his attitude, Eden shouted back, "But what's all this nonsense about isolating Nasser, or 'neutralizing' him, as you call it? I want him destroyed, can't you understand?"

The opportunity Eden wanted came shortly. Earlier that year, the US and Britain had agreed to lend $270 million for the construction of the Aswan High Dam; in July they canceled the offer. The official reason for this about-face was the instability of Egypt's economy, but the West really wanted to punish Nasser for flirting with the Soviets. In response, Nasser announced a week later that he would nationalize the canal. In a fiery three-hour speech, he told a cheering crowd that Egypt would build the dam with revenues from the canal, and if the imperialist powers did not like it, they could "choke on their rage." Since Nasser was planning to pay the canal's European stockholders for their shares, the takeover was legal, but the speech started a panic anyhow. Britain hosted an emergency meeting for the principal canal-using countries in London; Egypt was invited, but a few days before the conference began, Eden made a television broadcast in which he called Nasser a "man who cannot be trusted to keep an agreement. We all know this is how Fascist governments behave." The Egyptians refused to attend, and just as predictably, Nasser flatly rejected the conference's proposal to have an international board operate the canal. Now Britain looked for an excuse to invade Egypt, topple Nasser, and restore the canal to Western hands.

That is when France and Israel entered the game. The French thought Nasser was giving aid to anti-French rebels in Algeria, and were quite happy to help anybody who was trying to get rid of him. Israel was willing to get involved because tensions had been steadily rising for the past year. Egyptian-backed Fedayeen raids across the border into Israel were met with heavy reprisal raids from the IDF; then Nasser closed off both the Suez Canal and the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping. In late October, Britain, France, and Israel made their plans in a secret meeting at Sevres, near Paris.(2) On October 25, Egypt raised tensions another notch by announcing that the Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian armies would be placed under the command of an Egyptian general.

For the Israelis that meant it was time to go ahead with the plan they had agreed to with their allies. On October 29, 1956, Israeli paratroopers dropped into the middle of the Sinai, and Israeli tanks roared into the desert to meet them. Other IDF units, moving along the coasts, took Gaza and Sharm el-Sheikh; the former was a hornet's nest of guerrilla bases, the capture of the latter allowed Israeli shipping to sail in the Red Sea again. Britain and France, playing the role of peacemakers, stepped in and issued an ultimatum: both sides must stop fighting and pull their troops at least ten miles from the canal, to protect it from possible damage or disruption. The Israelis accepted this demand, since they were still about 125 miles east of the canal; the Egyptians rejected it rather than withdraw 135 miles from territory they still had. On October 31, British and French planes went into action, destroying Nasser's air force and knocking out Egyptian radio stations. Five days later, an Anglo-French force landed at the north end of the canal, captured Port Said, and pushed south.

As it turned out, this was the last exercise in old-fashioned "gunboat diplomacy." The world was also holding its breath over another crisis (Soviet repression in Hungary), but both the US and the Soviet Union disliked what they saw in Egypt. The United Nations condemned the British and French for what they did; the Soviets threatened to intervene on the side of Nasser; the US warned the financially strapped British government that it could expect no more loans while British troops were in Egypt. The Egyptians made the canal useless by sinking ships in it, and Syria blew up the oil pipelines that crossed its territory, threatening Western Europe with a serious oil shortage. Under this combined pressure, fighting halted, and all three attacking countries withdrew their forces from the Sinai over the next few months. A political casualty of the war was Sir Anthony Eden, who under failing health, resigned in January 1957. In other words, his efforts to get rid of Nasser resulted in the destruction of his own career.

The political victory in the war went to the intended victim: Nasser. He had stood fast against two major Western powers and an aggressive Israel; instead of toppling him, the war had made him a hero among Arabs everywhere. Nasser's picture became a common sight from Morocco to the Persian Gulf, and he was viewed as the unofficial leader of the Arab world. Nearly every Arab-owned radio was tuned in when emergency measures brought Cairo's powerful propaganda machine, the "Voice of the Arabs" radio station, back on the air again. In this heady atmosphere Nasser accepted the role of champion of the Arab renaissance, and spent the rest of his life trying to live up to it.

The United Arab Republic

Taking advantage of his new popularity, Nasser used the Egyptian media to call for pan-Arab unity under his charismatic leadership. This program bore unexpected fruit quickly. In February 1958 Nasser and Syria's Baathist leaders announced they were uniting to form a new nation called the United Arab Republic (U.A.R.), and they declared that this was "a preliminary step toward the realization of complete Arab unity." Before the end of the year Yemen also joined the U.A.R., in a looser federation that left the imam's government in charge of local affairs. The other Arab states were also potential members. A pro-Nasser government briefly held power in Jordan, and when anti-Hashemite riots broke out there, King Hussein called in British troops to restore order. His cousin was not so lucky; a bloody coup in July killed Iraq's King Faisal II and wiped out the whole Hashemite family in that country. Iraq's new leaders declared they would "stand together as one nation" with the U.A.R. And the Nasserist tide threatened Lebanon's delicate government, causing a crisis that we will cover in the next section.

The Soviet Union took full advantage of the situation. There were already Soviet advisors in Egypt, helping Nasser build the Aswan High Dam and training his army to use the new weapons that they generously provided. Now Soviet arms, advisors, and technicians also appeared in Syria and Iraq. This raised anti-Soviet fears, not only in the West but also among conservative monarchies like Jordan and Saudi Arabia, and among Lebanese businessmen. None of these Arabs wanted unity if it meant replacing Western domination with Soviet puppet states.

Strains like this put the U.A.R. in trouble almost immediately. Iraq may have been a strong advocate for Arab unity, but it but it wasn't going to let any rival, even a like-minded one, have Syria, the heart of the ancient Fertile Crescent. The U.A.R. also had problems which even Nasser's charisma could not cover up. Syria had only one fifth of Egypt's population and no leader of Nasser's caliber; consequently Syria was the junior partner in the U.A.R., and the Syrians resented that. Nasser tried to set up in Syria the same policies he had used in the Nile Valley: one-party rule and "Arab socialism."(3) The Syrians had accepted union as a solution to their own chronic instability, but this was too much for them. In September 1961 a coup brought new army officers to power, and they immediately declared Syria's independence from the U.A.R. By this time the burden of governing both Syria and Egypt was an intolerable strain; Nasser did nothing to prevent the separation.

Other attempts have been made to unify the Arab world since 1961, with dismal results: Egypt-Syria-Iraq, 1963; Egypt-Libya-Syria, 1971; Egypt-Libya-Sudan, 1972; Egypt-Libya, 1972 & 1973; Syria-Iraq, 1979. More recently the Arab world has tried forming smaller regional blocs, rather than attempt to merge into a single super-state; examples include the Gulf Cooperation Council (Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrein, Qatar, the U.A.E. and Oman), the Arab Maghreb Union (Mauretania, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya), and the Arab Cooperation Council (North Yemen, Egypt, Jordan and Iraq). Whatever the method used, a clash of personalities, and sometimes a clash of ideologies, has thwarted any action that did more than promote economic cooperation (e.g., the 1979 Syrian-Iraqi union was stopped dead in its tracks when Saddam Hussein became president of Iraq). Sometimes a mutual hatred of Israel was the only thing that made the Arab leaders consider unification in the first place. Another factor was the cultural differences that exist in the Arab world; contrary to what Sati al-Husri believed, it takes more than a common language to define an ethnic group. No wonder that in 1979 an exasperated Syrian columnist wrote that "Trying to unite the Arabs is like nailing jelly to a wall." When Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, a prominent Saudi Arabian businessman echoed the feelings of many by saying, "Al-uruba intaharat" ("Arabism has committed suicide").

In a sense, after 1958 Nasser was a captive of his own image. The Arab masses had all but deified him, and he had raised expectations among them that no leader could possibly fulfill. They now viewed him as a modern-day Saladin who would show them the way out of poverty and lead them in triumph against the Israelis. Yet a third Arab-Israeli war was something Nasser did not want. He remembered very well how the 1948 and 1956 wars had all but destroyed the Egyptian army, and knew it could happen again, despite Soviet arms and training. In the 1960s he attempted to dampen Arab hopes, but still they drew him into another near-fatal confrontation with Israel.

The 1958 Lebanese Crisis

All nations require some tolerance and compromise between their various communities; for Lebanon it is a matter of survival. As pointed out earlier, this small state is a collection of Arabs of various religions (Maronite Catholics, Greek Orthodox, Sunni & Shiite Moslems, Druze, and a few Protestants) with a sprinkling of Armenians and Jews thrown in. The government enforced this diversity by reserving key positions for as many ethnic groups as possible, though no census could be taken to figure out the size of each. Yet the Lebanese enjoyed more freedom than any other society in the Arab world, which is probably why the system worked for thirty years despite its illogical nature. The mutual tolerance allowed a form of laissez-faire capitalism rarely seen in the Third World, a subtle reminder of the country's Phoenician founders. Beirut became a Mediterranean beach resort that attracted European tourists; wealthy Arabs came to Beirut as well, to buy anything they could not get at home.

The first Lebanese president, Bishara al-Khuri, rigged the 1947 elections to produce a friendly parliament, which returned the favor by granting his request: a temporary amendment to the constitution that gave him a second six-year term in office, starting in 1949. Of course this did not go over well with most of the people, and a general strike launched in September 1952 forced Khuri's resignation. Parliament elected another Maronite, Camille Chamoun, to succeed him.

Chamoun was very pro-Western, and refused to break diplomatic relations with Britain and France during the Suez war of 1956. This made Nasser his enemy, and Nasser accused Chamoun of trying to bring Lebanon into the Western-sponsored CENTO (Central Treaty Organization) alliance.

Matters came to a head in 1958, for two reasons: (1.) Chamoun, like Khuri, tried to manipulate the government to allow his reelection, and (2.) the creation of the United Arab Republic put a Nasser-controlled province (Syria) right on Lebanon's doorstep. Nasserists, most of them Lebanese Moslems, called for Lebanon to join the U.A.R.; Christians, who feared that the country's careful political compromise was coming apart, wanted to keep Lebanon aligned with the West. Arms filtered across the Syrian frontier and in May a general strike was proclaimed. Moslems rose in rebellion, and the army was asked to take action, but the commanding general, Fuad Chehab, refused to attack the rebels, out of fear that this would split the army into Christian and Moslem factions. When a coup toppled Iraq's pro-Western government in July, Chamoun immediately requested US military intervention, and on the following day 3,600 US marines landed outside Beirut. The marines saw no action--they stayed in a camp on the beach--but their presence made Nasser forget about invading Lebanon, and the crisis gradually ended as tempers cooled on all sides. Because he had shown restraint at a critical moment, Christian and Moslem now respected General Chehab, and Parliament voted to have him replace Chamoun as president. The American troops and Nasser's agents departed, and Lebanon resumed the political balancing act it had practiced before.

More Years of Armed Truce

The early 1960s was a relatively quiet time for the Middle East. Both Nasser and King Hussein chose to concentrate on solving domestic problems rather than pick a fight with Israel. Lebanon's President Chehab finished his term in office (1958-64) without any major problems, and so did his successor, Charles Helou. Helou was followed in 1970 by the more troubled regime of Suleiman Franjieh.

In Israel, David Ben-Gurion made a political comeback, and he served as both prime minister and defense minister for most of the time between 1955 and 1963. Then he retired again, and Levi Eshkol served as prime minister from 1963 until his death in 1969. During this period the main news item was the arrest, trial, and execution of Adolf Eichmann, a former Nazi official who had been a leader in the extermination of Jews during World War II.

Syria continued to live up to its reputation as the most unstable Arab state. The Syrians were deeply unhappy that they, the first to propose Arab unity, should have been the ones to kill it when it was first put in practice. They hated the title of "secessionists" which Egypt hurled against them, and in 1963 the shamefaced regime was thrown out in a coup that put the Baathists back in control, under Major General Amin al-Hafez.

Since Arab unity is the cornerstone of the Baath creed, the new government declared its willingness to join in a political union with Egypt and Iraq. Yet the factors that made the U.A.R. fail were still around. Because of Egypt's huge population, any union which gave an equal share of power to the non-Egyptian territories would have been artificial and unworkable, but a united Arab state dominated by Nasser was unacceptable to the Baathists. Thus the plan died before it was born.

The Baathists in Syria had another problem that stemmed from pan-Arabism. Although Syrians led the party, it had branches in Iraq, Lebanon, and Jordan, giving non-Syrian Baathists a considerable say in Syrian affairs. The party split in 1966 and in that year a coup gave Syria to the more radical faction. The new leaders separated the Syrian from the non-Syrian branches of the party; since then the Syrian and Iraqi Baathists have been bitter rivals who can't get along. One outcome of the split was that the ideological founders of the party, Michel Aflaq and Salah Bitar, went into exile. It was as if a group of neo-communists had seized power in Russia but publicly rejected both Marx and Lenin, and many Arabs felt that only the Syrians could be so perverse.

Paradoxically, membership among the Syrian Baathists now came mostly from two religious minorities, the Alawites and the Druze. Before 1966 was over the Druze were purged, leaving the Alawites in control. Traditionally the poorest and least educated group in Syria, the Alawites had joined the army because that was the only avenue for upward mobility left open to them. Their numbers in the ranks steadily increased, until there were enough of them to wrest control of the armed forces, and eventually the government, from the country's Sunni majority. Knowing that their rule is not popular among the Sunnis, the Alawites stayed united behind their leaders after that, giving Syria a stability that did not exist under Sunni rule. For similar reasons, the Baath party uses military force to keep itself in power, which I am sure is not what its founders had in mind.

The Six Day War

Tensions between Israel and the Arab states rose again in 1966-67. This time the new Syrian government was responsible; it deliberately provoked incidents with Israel, presumably to direct Syrian attention away from domestic issues. They gave arms to Palestinian guerrillas, who now had bases in Syria for their activities. Syrians on the Golan Heights took pot shots at Israeli farms in the upper Jordan valley. Israel retaliated with first counter-shelling, then air strikes against Syrian positions; Jerusalem warned that it would take more severe action if the guerrilla raids continued. Both Syria and the Soviet Union used this threat to maximum effect, to rally more Arab support.

What happened next was like trying to put out a fire by pouring gasoline on it. The Syrians were on the worst possible terms with every country around them, but now the other Arabs put aside their squabbles to deal with the enemy they all hated: Israel. Saudi Arabia and Iraq disliked King Hussein, for example, but both sent thousands of troops to back up the Jordanians in the upcoming war. Arab states farther away from the action like Kuwait, Sudan and Algeria also promised to get involved. By May 1967 the Arabs had committed 547,000 armed men, 2,504 tanks, and 957 combat aircraft; against this Israel could muster no more than 264,000 troops, 800 tanks, and 300 warplanes. Arab propaganda heated emotions to a fever pitch, convincing many that the final campaign to destroy Zionism was about to begin.

Nasser wanted to defuse the crisis, but it had gone beyond his control. He knew that the Israelis had beaten superior odds before, and did not want to fight them while 50,000 of his best troops were tied down in Yemen's civil war. Syria called him a coward for boasting of Egypt's military strength while sitting behind a UN peacekeeping force. To save face, Nasser had to order the UN to remove its troops from the Sinai. Once they were gone, he did what all Arabs expected of him: he rushed Egyptian forces into the peninsula and closed the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli shipping. At the end of May one of his former enemies, King Hussein, flew to Cairo to sign a Jordanian-Egyptian defense pact. His commander in chief, Field Marshall Abdul Hakim Amer, quelled whatever misgivings Nasser might have had about Egyptian readiness by pointing to his neck and saying, "On my own head be it, boss! Everything's in tiptop shape."

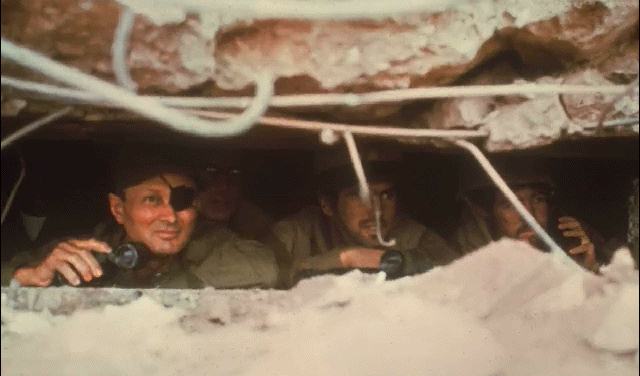

The Israelis did not wait for the Arabs to strike the first blow. Since the previous war, they had created a remarkable force to defend themselves with. Instead of a large standing army, which they did not have the population to support, they gave everybody military training and reserve duty. When war threatened, archaeologists, farmers, professors and musicians put aside their civilian tools and became fighting men and women. No expense was spared on buying the best airplanes from Britain, the United States, and especially France. On June 1, Jerusalem let the world know it was ready by appointing Moshe Dayan, an officer with unquestioned hawkish credentials, as defense minister.(4)

Dayan had already planned an ambitious preemptive strike before he took the job. On the morning of June 5, 1967, 183 Israeli planes took off in a wave-slicing maneuver that carried them just 30 feet above the Mediterranean Sea. Minutes later they appeared over Egypt, and destroyed most of the Egyptian air force on the ground. The Egyptians were taken totally by surprise; Nasser accused the United States and Britain of helping the Israelis, since he did not believe they could send so many aircraft against him on short notice. Similar strikes on Jordan, Syria and Iraq gave Israel command over the skies on all fronts. The few Arab planes remaining were too disorganized to pose a threat. "They just don't fly the MIG-21 right," said one disappointed Israeli pilot about the Syrians. "We expect the best of the enemy; they want to prove we're wrong," another added.

The first radio reports from Cairo claimed that the Egyptians had defended themselves succesfully, and that Egyptian troops had already entered the Negev! That convinced King Hussein to enter the war, and Jordanian artillery began shelling Israeli-held West Jerusalem. However, Israel was ready for this and launched a three-pronged invasion of the West Bank. All columns converged on the Jordanian half of Jerusalem, where Israel decided not to use heavy armaments so that they would take the beloved Holy City intact. It was, but this also meant high casualties and two days of brutal, hand-to-hand street fighting. Finally on June 7 the Star of David flew over the Old City. Battle-hardened Israeli soldiers went to the Western (Wailing) Wall, which had been closed off to Jews since 1948, donned yarmulkes, and wept in the emotion of the moment. They also captured the Temple Mount, containing the Dome of the Rock and the al-Aqsa Mosque, but in the name of peace, Moshe Dayan chose to let it remain in the care of Arabs. The Temple Mount has been a center for Palestinian political activity since then, and today some Israelis, who would like to see Solomon's Temple rebuilt up there, wonder if Dayan might have made a mistake in the long run.

The loss of Jerusalem ended the game for Jordan, which agreed to a cease-fire on June 7. King Hussein had lost the conquests of his grandfather, and gained another 150,000 Palestinian refugees, who fled across the Jordan river to escape Israeli rule. He also lost most of Jordan's thriving tourist trade, since many places mentioned in the Bible (Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Hebron, Jericho, Shechem) were held by Jordan before 1967; that made his country even more dependent on foreign aid.

Meanwhile on the Sinai front, Israeli troops easily surrounded their Egyptian and Palestinian opponents. One IDF column headed to the southern tip of the peninsula (reopening the Gulf of Aqaba to Israeli ships), another surrounded Gaza, while the rest charged due west across the desert. The only major battle took place at Mitla Pass, on June 7, and one day later the Israelis reached the banks of the Suez Canal (the Egyptians blocked the canal with sunken ships, as they had done in the 1956 war). Egypt now also bowed out of the war.

Some thought Egypt's defeat would also mean the end of Nasser's career. He tried to make it so, going on radio and television to announce his resignation. But so firm was his place in the hearts of the Egyptian people that they simply would not let him resign. Crowds mobbed the streets of Cairo and Alexandria chanting "Nasser, Nasser, Nasser" until the Egyptian National Assembly rejected his resignation and voted instead to give him full powers for "the military and political rebuilding of the country." Similar pro-Nasser demonstrations took place in Beirut, Damascus, Baghdad and Benghazi.

Only Syria remained to actively fight Israel. Since their positions elsewhere were now secure, the Israelis had a free hand to deal with the Syrians, and in a lightning campaign they captured the Golan Heights. After only 27 hours of fighting (June 9 & 10), Quneitra, the Syrian provincial capital, fell. Syria gave in to calls for peace and the Six Day War was over, with time remaining for Israel to enjoy the Sabbath.

The swift, stunning war had cost the Israelis 766 lives; as in all wars, Arab casualty figures are not available, but estimates place the total Arab number between 15,000 and 25,000. In less than a week, Israel had taken territory four times its own size, and now at last, it had sensible and secure borders. That has always been a major concern for the Israelis, since they are a small nation--an island of democracy--surrounded by larger, hostile countries. Before 1967, the part of Israel around the city of Netanya was only nine miles wide, and Israelis had nightmares about Arab tanks coming through that area and cutting the country in two. Furthermore, most of Israel's Jewish population lives in an L-shaped zone, stretching from Haifa to Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, and before 1967 all of it was in range of Jordanian artillery.

There is a story of uncertain origins that makes a point about Israel's preoccupation with security. In the early 1970s, the United States proposed that Israel return to its pre-1967 borders in return for a promise of peace from the Arab states. The US secretary of state, William Rogers, went first to Egypt, then Israel, to sell this "peace plan."

In Israel he was welcomed by Golda Meir, who had become prime minister in 1969. Ms. Meir asked if Mr. Rogers would mind stepping over to a window with her before they began their discussions. Of course he'd be glad to. She pointed to a school yard where children were playing. He remarked on the lovely children. Ms. Meir then asked him to look through another window at some hills. He remarked that they were very pretty hills. Well, said Ms. Meir, those schoolchildren used to live underground because enemy soldiers in those hills were shooting down at them. Those children, she said, were not going to have to live underground again. Now, Mr. Secretary, what was it you came to see me about? End of peace plan, end of story.

Israel also got a burden of human misery with its conquests. One and a half million Arabs lived in those territories and were unable to get out in time. Many of them, especially in the Gaza strip, lived lives of hopeless desperation in refugee camps. These homeless noncitizens would become the guerrillas and terrorists of the next generation.

The War of Attrition

Shortly after the Six Day War, Israel offered to exchange the land it had won for permanent peace with its neighbors. The Arab response, from a summit in Khartoum, was right to the point: "No peace with Israel, no negotiations with Israel, no recognition of Israel." The next few years saw random violence, international skullduggery, exits (some dramatically fatal), and entrances by several new important characters on the Middle Eastern stage.

Though his leadership of Egypt remained unquestioned, Nasser was no longer the spotless hero of Suez. He had led the Arabs to what they believed was Armageddon--and lost. He welcomed two more nations to the radical Arab camp (young officers that admired and imitated Nasser seized control of Libya and Sudan in 1969), and he saw the British withdraw from their last bases and protectorates in the Arab world, but faced problems in Egypt itself. In August 1967, he purged the army, sending many senior officers to prison; there the disgraced commander in chief, Field Marshall Amer, committed suicide. Food shortages caused serious rioting among students and industrial workers in 1968 and 1969.

He also had to continue the struggle against Israel, whether he liked it or not. In October 1968 the Egyptians opened fire on Israeli positions along the Suez Canal. The Israelis responded with counter-raids, and fortified their side of the canal, calling it the Bar Lev Line (named for chief of staff Rav-Aluf Chaim Bar Lev). Fighting escalated, until Nasser declared he was going to wear down the enemy in a "War of Attrition." It was not the best of arrangements--no territory was gained or lost, and Egypt suffered more casualties than Israel did--but while it continued the Arab leaders who participated remained legitimate in the eyes of their people.

Not all of the casualties in the War of Attrition were military ones. The Egyptians living in cities near the canal had to be moved elsewhere, putting more strain on Egypt's economy. World commerce suffered, because Egypt could not remove the wrecks blocking the canal while fighting took place near it. In April 1969 reports of Soviet missile installations in Egypt chilled the world community. In July Syria jumped in with artillery and jet attacks. Israel retaliated with its air force, first attacking military targets along the canal, then striking targets deep inside Egypt. Jordan got involved by sheltering Palestinian guerrillas, until their presence made King Hussein uneasy. In the summer of 1970 Soviet pilots started flying missions for Egypt; Israeli jets downed four Soviet MIG-21s on one day. Finally everybody got tired of the fighting, and in August 1970 Egypt, Jordan, and Israel agreed to a 90-day cease-fire. As part of the agreement, Egypt agreed not to place any missiles within 20 miles of the canal, but within two weeks she had built between 20 and 30 new sites and placed more than 500 missiles in them; that would cost the Israeli Air Force dearly in the next war. The agreement also called on Jordan to do something about the Palestinians, which brings us to an explosive new factor in Middle Eastern affairs.

The Palestinian Wild Card

As pointed out earlier in this chapter, the Palestinian Arab refugees have been kept in a deliberate state of neglect by the Arab countries that accepted them. No Arab government recognized them as different from other Arabs, and they did not try to create a Palestinian Arab state while Jordan had the West Bank. Only Jordan granted citizenship to the refugees, a quiet admission from King Hussein that Jordan is still part of Palestine, despite the name changes. When Israel captured the nearest refugee camps in the Six Day War, the UN did not even allow the Israelis to resettle the residents of those camps. The refugee camps became permanent communities; cement blockhouses replaced tents, utilities were installed, and schools and shops were built. Denial of citizenship meant a denial of political & economic power, and made the refugees subject to discrimination.(5)

Before 1967 the Palestinian Arabs went along with this; they had faith that the Arab states would liberate their land, and expected to become part of the huge Arab nation Nasser talked about. The Six Day War shattered this hope, and soon they came to the conclusion that if the job was going to get done, they would have to do it themselves. As their sense of nationalism grew, several Palestinian guerrilla movements appeared on the scene, which the Arab governments generously funded and equipped. Outside the Arab world the Palestinians succeeded in changing world opinion on the conflict; instead of spewing rabid anti-Semitism and talking about driving the Jews into the sea, they told about the injustices they had suffered and made Israel look like the bully, rather than the underdog. Many leftists and students, who would have been inclined to support Israel in the past, now favored the Palestinian cause instead.

The largest of the Palestinian guerilla groups was al-Fatah, meaning "The Victory." Its leader was a shabby and elusive figure, Yasir Arafat (1929-). Born in Cairo under the name of Muhammad Abd ar-Ra'uf Arafat al-Qudwa al-Husayni, his early years were shaped by parental neglect. His mother, a distant relative of the Mufti of Jerusalem, died when he was five, while his father, a small-scale textile worker, was obsessed by a long (and ultimately unsuccessful) lawsuit to reclaim some land in Egypt that had belonged to his family 150 years earlier. Eventually the father sent the son to live with his maternal uncle in Jerusalem; the two of them couldn't get along after that, and when his father died (1952), Arafat did not even attend the funeral.

After growing up, Arafat served in the Egyptian military during the 1948 war, studied engineering at Cairo Unibersity, joined the Moslem Brotherhood, and left Egypt under a cloud when Nasser suppressed that organization in 1954. He returned one year later to complete work on his degree, and decided to support the Palestinian Arab cause, by forming al-Fatah. Kuwait, where he had an engineering firm, became his first source of financial support, while Algeria provided recruits and training. However, Kuwait and Algeria were too far away to provide a suitable military base. At first the only frontline Arab state that would have him was Syria, so he moved there in 1963. On the first day of 1965 al-Fatah made its first raid into Israel, announcing its existence to the world. One year later, sensing a threat, Hafez al-Assad, the Defense Minister of Syria, had him arrested on a murder charge, though it wasn't clear whether Arafat was even in the room when the murder took place. Arafat was covicted, and Assad wanted him executed, but by then Arafat had a potent reputation among the Arabs, so he was quietly released instead.

Other groups formed in different places, with similar goals in mind. From the refugee camps of Gaza came the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), founded in 1964 by a lawyer named Ahmad Shukairy. More radical was the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), founded in 1968 by a Christian medical student, Dr. George Habash. Unlike Arafat, who hinted at compromise when talking to non-Arabs, Habash told everyone that his goal is the total destruction of Israel. Habash was also the first to advocate terrorist attacks outside the Middle East, like hijackings and bombings. To him anything that hurt Israel could be justified and if innocent civilians suffered this was sad but could not be helped. This hardline position has always given him followers, but because he was not a Moslem he never became leader of the whole Palestinian movement.

Shukairy, Habash, Arafat, and other Palestinian leaders began to coordinate their activities shortly after the Six Day War. At a major conference held in Cairo (1969), Shukairy was ousted from PLO leadership (his rivals accused him of being more interested in words than action). The PLO now became an umbrella organization, uniting the old PLO, al-Fatah, and several smaller groups, with Arafat as leader over them all. The PFLP also joined, but withdrew in September 1974. There were two reasons for this: (1.) a personal rivalry between Arafat and Habash, and (2.) Habash's insistence that all Palestinians commit themselves to a single ideology (by contrast, Arafat felt that ideological commitment could and should be put aside until after Palestine is liberated).

Though it was a small organization, even the PFLP suffered ideological division. Late in 1969, a Jordanian Marxist, Naif Hawatmeh, broke away to form the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP); Hawatmeh felt that Habash was too petit bourgeois to be a proper revolutionary leader. Around the same time, a Syrian Army captain, Ahmed Jibril, formed the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC), and concentrated on waging war inside Israel, against her citizens. Both splinter groups remain under PLO leadership today, unlike the main body of the PFLP. Al-Fatah suffered a split of its own in 1978 when one of its officers, Abu Nidal (real name: Mazen Sabry al-Banna), broke away because he thought Arafat was too "accommodating." Abu Nidal's group, Black June, has been supported at different times by Libya, Iraq, and Syria, and claimed responsibility for many attacks on Palestinian moderates.

The one thing on which all the Palestinian groups agreed was the rejection of all previous peace attempts, including UN Security Council resolutions, since a peace agreement with Israel suggests that Israel has a right to exist. Instead they proposed a secular democratic state called Palestine, where Moslems, Christians and Jews could live together in equality. That proposal implies the destruction of the Jewish state, and Palestinian leaders were ominously silent on what would happen to the Jews should they accomplish that. Some hinted that those Jews who came to the land before 1948, or those who accepted the Palestinian state, would be allowed to remain. Yet the savagery of Palestinian terrorist attacks on Israeli markets, schools, airports, overseas consulates, and airliners undermined Jewish faith in Palestinian promises. Furthermore, the idea that Moslem and non-Moslem can live together as equals is questionable, since in the past Moslem leaders have always insisted on the humbling of the Dhimmi among them, with restrictive laws, higher taxes, distinctive clothing, etc. In April 1975, Yasir Arafat was quoted as saying, "We have in the Lebanese experience a significant example that is close to the multi-religious state we are trying to achieve"; that was just days before Lebanon's devastating civil war began!

Two years later (March 31, 1977), Zahir Muhsein, a member of the PLO's executive committee, explained the Arab world's plan for the Palestinians, in a remarkably candid interview with the Dutch newspaper Trouw:

"The Palestinian people does not exist. The creation of a Palestinian state is only a means for continuing our struggle against the state of Israel for our Arab unity. In reality, today there is no difference between Jordanians, Palestinians, Syrians, and Lebanese. Only for political and tactical reasons do we speak today about the existence of a Palestinian people, since Arab national interests demand that we posit the existence of a distinct 'Palestinian people' to oppose Zionism . . . For tactical reasons, Jordan, which is a sovereign state with defined borders, cannot raise claims to Haifa and Jaffa, while as a Palestinian, I can undoubtedly demand Haifa, Jaffa, Beer-Sheva and Jerusalem. However, the moment we reclaim our right to all of Palestine, we will not wait even a minute to unite Palestine and Jordan."

All Palestinian groups attempted to set up advance bases in Israel, so they could advance from sporadic terrorist attacks to full-scale guerilla activity. Hundreds of raids took place, some of them led by Arafat himself; by the end of 1968, 234 Israeli soldiers and 47 Israeli civilians were killed. Also killed were 50 Arabs on the West Bank and 138 Arabs in the Gaza strip, whom they accused of "collaborating" with Israel. The IDF struck back, crossing the Jordan river in March 1968 to attack Karame, the main terrorist base in Jordan. Then they sealed the border with fences and minefields, and gradually flushed out the terrorists; by 1970 Gaza and the West Bank were secure again. As military exercises the raids had been failures, but as publicity exercises they were fantastic successes, capturing the imagination of the Palestinian people.

Gradually acts of terrorism became the preferred way of advancing the Palestinian cause. Since he suggested it first, George Habash led the way. In the summer of 1968, the PFLP hijacked an EL AL airliner from Athens. The plane and its more than twenty Jewish passengers went to Algiers and were held there--while the world watched--for five weeks. It was a modest beginning, but it worked as a public relations venture. The hijacking got world coverage, nobody was killed, and the job was carried out with disciplined precision. Habash struck again in December 1968, seizing and burning another EL AL airliner in Athens. This time the Israelis retaliated, with a helicopter raid on Beirut's airport that demolished thirteen Lebanese airliners. Since Habash commanded his war from Lebanon, Lebanon now suffered for it.

Ahmed Jibril's group made its debut in February 1970, when PFLP-GC agents persuaded some young women in Zurich to carry some packages aboard a SwissAir jet bound for Tel Aviv. The plane exploded in midair, killing all 47 people aboard.

The PFLP's most spectacular stunt took place on September 6, 1970, involving four airliners and more than 600 passengers. They hijacked all over Europe, but one got away. On this one, an EL AL 707, the crew and passengers fought back; a male hijacker was fatally shot while his female companion, Leila Khaled, was wounded and overpowered. The plane landed at a London airport and Khaled was taken into custody; one steward was shot in the scuffle and two passengers suffered cuts and bruises, but all of them made it to the hospital in time. The other three planes were not so fortunate. One of them, a PanAm 747, was taken as far as Beirut before it ran low on fuel and was forced to land. A TWA 707 and a SwissAir DC-8 went to an abandoned World War II airfield at Mafrak, in northern Jordan. Three days later a BOAC VC-10 was also hijacked and brought to Mafrak. There the hijackers demanded the release of guerrillas imprisoned in Switzerland, West Germany and Britain (including the recently arrested Leila Khaled), and gradually released the passengers, except for 54 Jews. The countries holding the prisoners agreed to release them, the remaining hostages were set free, and the hijacked planes at Beirut and Mafrak were destroyed--in a blaze of revolutionary glory.

King Hussein was embarrassed at this whole escapade. While the hijackers were at Mafrak, they had claimed the airstrip for themselves, renaming it "Revolution Air Base." Not only was this an affront to Jordanian sovereignty, but Hussein was already unhappy with the behavior of other Palestinian guerrillas in his country. The result was a brief but bloody conflict in the second half of the same month, now called "Black September" by the Palestinians.

Black September

King Hussein had long been concerned about the Palestinians in Jordan. Now that the West Bank had been lost to them, the various Palestinian groups based themselves in Jordan and Lebanon. From there they launched raids against Israel and increased in numbers & strength, becoming a virtual state within a state in both countries. Hussein encouraged them at first; at a press conference in March 1968 he declared, "One day we will all be Fedayeen." To the commandos he said they could do whatever they pleased if they did not fire their weapons until they crossed the border into Israel. Yet whenever Israel struck back at the commandos, it hit targets in Jordan and Lebanon. Furthermore, the Palestinian presence was a threat to Hussein's throne; they might decide to throw him out and make Jordan the real Palestinian state, since they already made up most of Jordan's urban population.

When Hussein signed the 1970 cease-fire that ended the "War of Attrition" between Egypt and Israel, many Palestinians called for his elimination. An unsuccessful assassination attempt on September 1 confirmed the king's worst fears and unleashed a fury of retribution. On September 16 he declared martial law and formed a military government to enforce it. A 24-hour curfew went into effect in Amman and Zarka, while heavy fighting broke out in five cities, including Amman. Palestinians occupied two hotels in the capital and held sixty occupants hostage, to gain world attention. They lobbed rockets at the radio station and even the royal palace. However, the Jordanian soldiers had heavy artillery, and within ten days they smashed the Palestinians around Amman, driving them into the northwestern corner of Jordan. There the Syrians intervened briefly but ineffectively on the side of the Palestinians; Iraq also promised to help but that support never appeared. At the end of September a cease-fire signed in Cairo went into effect, but small-scale fighting continued while the Jordanian government asserted its authority. In July 1971 the Palestinians were driven out of their last strongholds (Jerash, Ajlun, and Irbid). Most of them fled to Syria and Lebanon; a few went to Iraq and Israel. Estimates of the total number of casualties range from 5,000 to 25,000, and surely include many Palestinian civilians. Whatever the number, the Palestinian political presence in Jordan had been eradicated. King Hussein's throne was safe.

One casualty of the Jordanian civil war was an indirect one: Nasser. He had suffered from diabetes since 1956, and his health steadily deteriorated after the Six Day War. Despite this, he felt the need to restore a united Arab front, so he invited all Arab leaders to an emergency conference in Cairo to end the war in Jordan. After the meeting ended Nasser went to the airport to say goodbye to the ruler of Kuwait, and on the way back he suffered a heart attack and died; he was 52. Apparently his death had been expected for some time. "Those who knew Nasser well," wrote Anwar Sadat, "realized that he did not die on September 28, 1970, but on June 5, 1967, exactly one hour after the war broke out. That was how he looked at the time, and for a long time afterward--a living corpse. The pallor of death was evident on his face and hands, although he still moved and walked, listened and talked."

The Jordanian civil war also finished off the Syrian government, which was discredited by its unsuccessful involvement. In November 1970 the coalition of military and civilian Baathists was ousted in a coup by the Defense Minister, General Hafez al-Assad. Assad was more formidable and clever than previous Baathist heads of state, and remained in office for the next twenty-nine years by using two tried techniques: ruthless suppression of all opposition and a steady campaign of propaganda or activity against opponents abroad (to keep Syrian attention distracted from domestic concerns). His long reign over Syria is remarkable when one considers that none of his predecessors could hold the job for more than four years.

The 1973 War

The Six Day War and Black September convinced King Hussein that peace was the best solution. In 1971 he held a secret summit meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir. Less than two years later, in January 1973, Meir invited Hussein to a second meeting in Tel Aviv, to talk about reports that Egypt was planning to attack. There, the king confided that Nasser's successor, Anwar Sadat, was indeed considering a military action, but he would make peace if Israel returned the Sinai to Egypt. Meir didn't believe that Sadat really wanted peace, so before he went home, Hussein surprised her with a proposal of his own. Written on a single sheet of paper with no letterhead, the document offered a peace treaty and normal relations between Israel and Jordan, and promised that Jordan would keep the West Bank completely demilitarized after Israel returned it. It also suggested making Jerusalem a city jointly ruled by both countries, instead of dividing it, and that resident alien visas would be issued to Israelis and Jordanians who chose to live in each other's country, allowing Jewish settlers on the West Bank to stay. It was the first Arab peace proposal to be put in writing, but Meir rejected the offer, believing that the Arabs could eventually be talked into letting Israel keep part of the West Bank. As with Nasser's diplomacy with Ben-Gurion, more than twenty years went by before anyone revealed that these meetings took place. Hussein had a very good reason to keep them secret; remember what happened in 1951 when his grandfather hinted that he would negotiate with the Israelis.

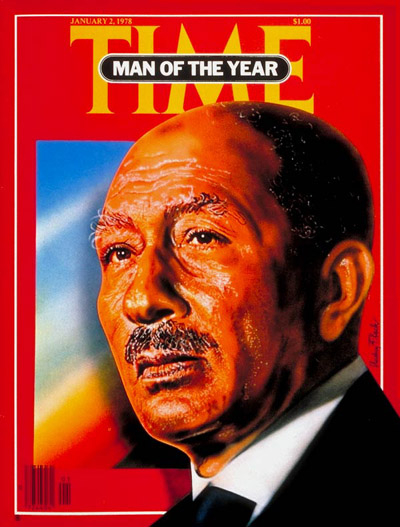

In Egypt, Anwar Sadat had been a quiet partner of Nasser for most of his adult life. An army captain during World War II, he flirted with Nazism (the British arrested him once on a charge of spying for the Axis) and Islamic fundamentalism before deciding that Nasser had the most practical plan for the future. More recently he was president of the Egyptian National Assembly, but since this was merely a rubber stamp to approve decisions Nasser had already made, the job hardly taxed his abilities. Early in 1970 Nasser made him vice-president, apparently because he was the least controversial candidate. The rest of Nasser's inner circle went along with this choice, since they thought they could easily manipulate the man they called Nasser's "black donkey." However, the "black donkey" had some tricks up his sleeve, and soon showed, in his own way, that he could be just as dramatic and flamboyant as Nasser had been.

Sadat began by dismissing his rivals from government, including the highest-ranking leftist, Ali Sabry. This alerted the Soviet Union, and the USSR promptly sent its number three man, President Nikolai Podgorny, to negotiate a 15-year treaty promising economic and military cooperation. Moscow thought all was safe when Sadat signed the treaty; Nasser had never been willing to put Soviet-Egyptian relations in writing. One year later (1972), however, Sadat declared that the USSR was taking too long to ship promised military equipment, and ordered all Soviet military advisors out of his country. The United States stepped into the vacuum left behind by the Soviets, and Egypt has been pro-Western ever since. Sadat also found it easy to improve relations with many countries that disliked Nasser, like Iran, Saudi Arabia and Britain.

The real reason for Sadat's policy switch was his realization that the United States was the only major power that could bring Israel to the conference table. The US did not respond right away, though, since the current deadlock worked to Israel's benefit (the Sinai peninsula gave Israel a very large buffer zone to protect the country with, and contained the only oilfield in both countries). It also seemed that the US and the USSR were too preoccupied with ending their own rivalry to pay much attention to the Middle East. Sadat then decided that he would use force to break the deadlock. In June 1973 he invited King Hussein and Syria's Hafez al-Assad to a summit meeting in Cairo. Nobody thought much of this--Arab leaders are meeting somewhere at any given time--and since Sadat had been threatening a new war against Israel since he took office, he wasn't taken seriously when he talked about it this time. What was kept secret from everybody, including even Hussein, was that Sadat and Assad agreed on a battle plan and a date to launch a two-pronged invasion of Israel.

The date they chose was Saturday, October 6, 1973. For Israel it could not have been a worse date; this was Yom Kippur, the holiest day on the Jewish calendar. It was also a holy day for Moslems--the 10th of Ramadan--so nowadays we call this conflict either the Yom Kippur War or the Ramadan War, depending on whose side you are on. Anyway, it began with a combined Egyptian-Syrian attack that caught the Israelis totally by surprise. 80,000 Egyptians crossed the canal, overwhelmed 2,600 Israeli defenders, and shattered the Bar-Lev line. The Syrians retook half the Golan Heights on the first day, while shelling and rocket attacks from Syria and Lebanon killed one Israeli and twelve Druze. Israel's advantage in air power and armor was also nearly neutralized, thanks to new Soviet-made SAM missiles and the Sagger antitank "suitcase missile," which a single infantryman can carry. Most of the Arab world was also surprised when the war began, but before it ended nine other Arab nations committed troops, tanks, and planes to support either Egypt or Syria.

For three days it looked like the Six Day War in reverse, with the Arabs making the surprise attacks and winning. Then they stopped advancing on both fronts. Why? The answer was never totally clear. The Egyptians dug in along a new front line ten miles east of the Suez Canal, while the Syrians did not cross the Jordan River into Israel proper. It appears that they did not want to advance beyond the covering range of their missiles, and they suspected that there were more Israelis behind the units they had just smashed. Actually there were almost no defenders left, and that pause was the miracle Moshe Dayan needed to mobilize the rest of the IDF. It took him 72 hours, because the war had started on a holiday, but once it was complete he effectively threw back the Arabs on both fronts. By October 12 the Golan Heights & Mt. Hermon were cleared of Syrians, and the Israelis began to advance on the suburbs of Damascus. On October 15 a maverick Israeli general, Ariel Sharon, broke through a gap between the Egyptian Second and Third Armies, crossed the Suez Canal, swung south to isolate the Third Army, and began a charge toward Cairo.

By this time both the United States and the Soviet Union were involved. The USSR acted first, by shipping military equipment to Egypt and Syria, and that prompted the US to do the same for Israel. When the tide of battle turned in Israel's favor both superpowers became extremely concerned. The Soviets wanted a truce before Egypt lost all of its initial gains; the Americans feared that Israel's capture of Cairo or Damascus would provoke a full-scale Soviet intervention. US forces around the world went on full military alert, and both the US and USSR put pressure on their client states to stop fighting. The combatants agreed to a cease-fire on October 22, but a new round of fighting broke it right away. When the second cease-fire went into effect (October 24), Israeli forces halted about sixty miles from Cairo and twenty-five miles from Damascus.

The 1973 war cost Israel 2,378 men, one third of her air force (102 planes), and more than 800 tanks, a shockingly high figure for a country the size of Delaware, with about the same number of people as Alabama. To comprehend such a loss, a comparatively high casualty count on the US armed forces would have resulted in 140,000 dead. As in previous conflicts, no official record of the Arab losses was ever released, but again we estimate that they were higher: about 19,000 dead, more than 350 fighter planes, 1,300 tanks, and 11 ships. Israel won on the battlefield, but in world opinion it was the first three days that counted, because it showed that superior equipment and surprise were not Israeli monopolies. Sadat could claim a great political victory, because he had succeeded in breaking the stalemate over peace in the Middle East. Now the United States worked overtime to arrange a comprehensive series of peace talks, no longer letting domestic concerns (Watergate, the 1974 recession, etc.) get in the way. The Arabs also recovered the self-respect they had lost in 1967, and they also discovered a devastating new weapon to use against the West: oil. We will cover the use of the oil weapon more fully in the section on Saudi Arabia in the final chapter of this work.

Terrorism: The Clandestine War

While the Middle East went through cycles of war and uneasy peace, Palestinian terrorists continued to make headlines of their own. In May 1972 four al-Fatah gunmen hijacked a Belgian Sabena 707 while it was on the ground at Lod Airport, only to be overpowered 23 hours later by a team of IDF soldiers disguised as mechanics.(6) Later in the same month the PFLP sent three Japanese "freedom fighters" they had trained at Baalbek, Lebanon. The three men flew to Europe, boarded an Air France jet bound for Lod, and cut loose with machine-gun fire and hand grenades in the airport's customs hall. One assailant, Kozo Okamoto, was captured, another committed suicide, while the third escaped. The final score was 26 dead, 72 wounded. Among the dead were sixteen Puerto Ricans on a pilgrimage to see the birthplace of Jesus.

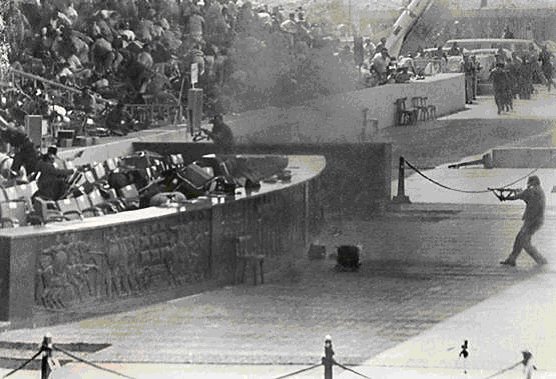

The next attack earned the revulsion of the world, because it took place where one expects only peaceful competition: the 1972 Summer Olympic games in Munich, West Germany. On September 5, 1972, eight members of a group that called itself Black September broke into the Olympic village, killed two Israeli athletes, and seized nine more. They announced that unless Israel released two hundred imprisoned guerrillas, they would kill the hostages at regular intervals. Israel refused to negotiate, leaving West Germany with the responsibility of making a deal with the Black Septemberists. They thought they succeeded when the terrorists accepted an offer of a helicopter to take them and the hostages to the nearest airport, where a Lufthansa 747 was waiting. At the airport, however, a firefight broke out between the Arabs and the German troops that tried to overpower them and free the Israelis. All nine of the Israelis were killed; four of them were incinerated when a hand grenade was tossed into the helicopter. Five Arabs and one German policeman were also killed. Three of the Arabs surrendered and were held for a month, when another Lufthansa jet was hijacked and threatened with the destruction of plane, crew, and seventeen passengers. The Arabs went to a hero's welcome in Tripoli, Libya.

1973 saw the murder of one Belgian and two American diplomats, including the US ambassador, in Khartoum, Sudan, by eight al-Fatah terrorists. In May 1974, Naif Hawatmeh's DFLP tried to achieve a military victory of its own. But "military" is hardly the word for what happened. At Maalot, a village in northern Israel, three DFLP gunmen took over an elementary school and demanded the release of 23 prisoners. The Israeli authorities never negotiated with terrorists before, and this time, instead of talking, sent in the army. Hawatmeh's men were killed, along with 22 children. Previously Hawatmeh had claimed he favored a political solution to the Palestinian problem, rather than a military one; now he lost whatever following he might have had from sympathetic Israelis. After this came a week of Israeli air raids on Palestinian bases in Lebanon, followed by a bloody but fruitless raid by the DFLP on an apartment in the village of Beth-Shan (November 1974).