| The Xenophile Historian |

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 7: THE GREAT WHITE NORTH, PART I

Canada since 1867

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| Postwar Canada | |

| The Conservatives Return From the Wilderness--But Not For Long | |

| Pierre Trudeau, Part I | |

| The Rise of Quebec Separatism | |

| Pierre Trudeau, Part II | |

| Neo-Conservatism, Canadian Style | |

| Political Uncertainty in the 1990s | |

| Recent Events | |

| Canada Today |

The Story So Far

Now it is time to resume our narrative on Canadian history, which we broke off at the end of Chapter 3. To much of the world, Canada is something of an afterthought, because when Canadians act, they usually do so as partners of the United States or the United Kingdom, rather than go it alone. Though Canada is a member of the G-7 group, meaning it is one of the world's richest nations, it is also the one with the lowest population, and the only one that does not manufacture its own cars. Sometimes Canadians also find it distressing that there are so few differences between their citizens and US citizens. For example, when people try to tell Americans and Canadians apart, they may look for superficial differences in dialect, like a tendency for Canadians to end a sentence with "eh?", or to pronounce the last letter of the alphabet "zedd" instead of "zee." And while several Canadian actors and singers have done well in the "Lower 48" (e.g., William Shatner, Gordon Lightfoot, Alanis Morissette, Jim Carrey, Elisha Cuthbert and Justin Bieber), their American fans need to be reminded from time to time that these stars came from north of the border.

At the beginning of this work, I mentioned that Americans tend to take Canadians for granted, acting as if Canada was an appendage of the United States (a recent T-shirt called Canada "America's hat"). The main reason for this is the harsh climate. Canada is at the same latitude as northern Europe, but because no warm ocean current bathes its shores, except on the Pacific coast(1), most of the country's weather is far colder than what you find in Europe. This means that while Canada has more square miles of land than the United States, most of it is an uninhabited, undeveloped wilderness, either a coniferous forest or Arctic tundra, with ice and snow for more than half the year, and full of furry animals instead of people (remember how the fur trade attracted the first explorers and colonists). Moreover, Americans have always outnumbered Canadians by 9 or 10 to 1, and 90% of Canada's population lives within one hundred miles of the US frontier, giving the country a geography that can seem one-dimensional at times; Canadians are more likely to travel east-west than north-south.(2) Despite the wish Canadians have to stay independent of the United States, most of them live in the 100-mile-wide zone next to the US, because that is where the most moderate climate is, that is where the jobs are, and because Tim Horton's doesn't have any coffee shops in the Arctic. North of latitude 60 N., the population is mostly Native American and Inuit, and there are so few permanent residents that the northern half of the country has never been organized into provinces; the only governments it has known are colonial and territorial ones.

Is this all that comes to mind when you think of Canada? If so, you need to keep on reading.

And this is how Canadians see their country.

Americans know about Canada's spectacular natural scenery, are familiar with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (also called the RCMP or "Mounties") from old Dudley Do-Right cartoons, and they may joke about the preoccupation Canadians have with hockey, but otherwise they tend to ignore their neighbor to the north. Indeed, stories from Canada rarely appear in U.S. news, and most Americans are lucky if they know the name of the current Canadian prime minister. And because Americans and Canadians have been the best of friends for more than a century, the frontier between the United States and Canada is the longest unfortified frontier in the world.(3)

If you had been around in the 1800s, you probably would not have bet on Canada remaining independent, because of the rowdy country to the south, also rich in natural resources and home to so many more people. Yet Canada not only survived but prospered.(4) What's more, Canada succeeded without being seen as obnoxious, as some foreigners have accused Americans of acting (the so-called "Ugly American"), and Canadians have never gone to war, except to fulfill their obligations to NATO and the British Commonwealth of Nations. Now that this narrative is done with the United States, we will give Canada equal time, so sit back and enjoy some stories you probably haven't heard before.

From sea to sea to sea: how Canada looks today.

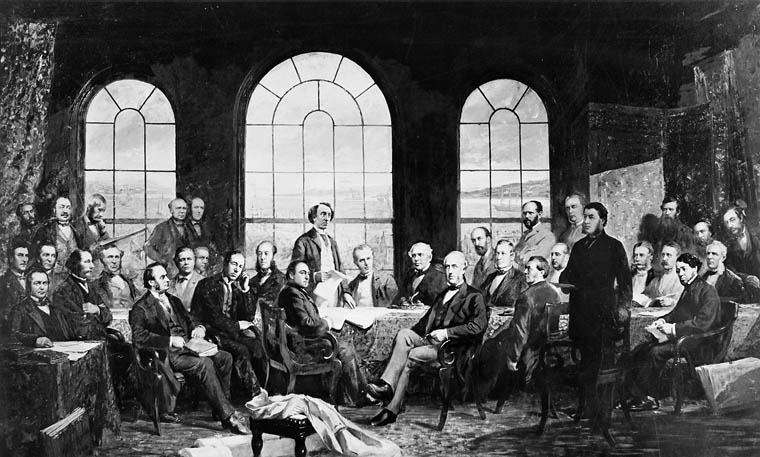

Early Canadian Politics, and the Maple Leaf Flag

The official date of Canada's birth as an independent nation is July 1, 1867, because that is when the British North America Act went into effect. From the start, Canada had a British-style Parliamentary government. The first Canadian Parliament met on November 6, 1867, with John A. Macdonald as the first prime minister.

Credit for the name "Dominion of Canada" usually goes to Samuel Leonard Tilley, a member of Parliament from New Brunswick. John MacDonald wanted to call Canada a kingdom, but since the object of the British North America Act was to put some distance between Canada and Britain, other Canadian politicians did not care much for the term; nor did they want to call their country a republic, because their rival to the south was a republic already. Tilley got the idea in 1866, while he was negotiating the terms of the British North America Act in London, and he found this verse in the Bible: "He shall have dominion also from sea to sea, and from the river unto the ends of the earth." (Psalm 72:8). To Tilley this meant that someday Canada would rule everything between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans (the "sea to sea" part), and from the St. Lawrence River to the North Pole. Well, maybe. It has also been pointed out that the British previously called another one of their colonies a "dominion"-when they merged all of their New England colonies under one government in the 1680s, to form the Dominion of New England.

For the time being, Great Britain retained control over Canada's foreign affairs, and the right to sign treaties for Canada; Canadians went along with this, because as we noted in Chapter 3, most did not want to break with the United Kingdom completely.(5) However, Canadians would have complete control over their country's internal affairs.

Canadian paper money. We are showing it here because these colorful bills feature four prime ministers discussed in this chapter. From top to bottom, the faces are as follows: Wilfrid Laurier on the (blue) 5 dollar bill, John MacDonald on the (purple) 10, Queen Elizabeth II on the (green) 20, William Lyon Mackenzie King on the (red) 50, and Robert Borden on the (brown) 100 dollar bill.

The new nation already had two major political parties, which had evolved before independence; Canadians could see from the British and American examples that a two-party system worked best. The Conservative Party (called the Liberal-Conservative Party before 1873) favored strong government, good relations with Britain, and tariffs; it was supported by groups favoring traditional values like the Orange Order (a Protestant fraternal organization, also called the Orangemen), United Empire Loyalists (descendants of the pro-British refugees who had fled the United States after the American Revolution), and those Ultramontane Catholics who wanted strong Papal authority. Because they were very much like British Conservatives, members of Canada's Conservative Party were called Tories, too.

The Liberal Party, on the other hand, was opposed to British imperialism, and wanted free trade with the United States. Most Canadians at this date considered the Liberal Party platform too radical, so they didn't do very well in the first elections. In the twenty-nine years after 1867, Canada had six prime ministers, and all but one of them were Conservatives. Later on, French Canadians switched their support to the Liberal Party, because of issues like the execution of Louis Riel and the Conscription Crisis of 1917; that helped ensure that the Liberals would become the dominant party in the twentieth century.

Canadian Prime Ministers

| Name | Dates | Party |

| Sir John A. MacDonald | 1867-1873 1878-1891 |

Conservative |

| Alexander Mackenzie | 1873-1878 | Liberal |

| John Abbott | 1891-1892 | Conservative |

| Sir John S. D. Thompson | 1892-1894 | Conservative |

| Sir Mackenzie Bowell | 1894-1896 | Conservative |

| Sir Charles Tupper | 1896 | Conservative |

| Sir Wilfrid Laurier | 1896-1911 | Liberal |

| Sir Robert L. Borden | 1911-1920 | Conservative-Unionist |

| Arthur Meighen | 1920-1921 1926 |

Conservative |

| William Lyon Mackenzie King | 1921-1926 1926-1930 1935-1948 |

Liberal |

| Viscount Richard B. Bennett | 1930-1935 | Conservative |

| Louis St. Laurent | 1948-1957 | Liberal |

| John Diefenbaker | 1957-1963 | Progressive Conservative |

| Lester Pearson | 1963-1968 | Liberal |

| Pierre Elliott Trudeau | 1968-1979 1980-1984 |

Liberal |

| Joe Clark | 1979-1980 | Progressive Conservative |

| John Turner | 1984 | Liberal |

| Brian Mulroney | 1984-1993 | Progressive Conservative |

| Kim Campbell | 1993 | Progressive Conservative |

| Jean Chrétien | 1993-2003 | Liberal |

| Paul Martin | 2003-2006 | Liberal |

| Stephen Harper | 2006-2015 | Conservative |

| Justin Trudeau | 2015-2025 | Liberal |

| Mark Carney | 2015-present | Liberal |

The first Dominion census, which was taken in 1871, reported a population of 3,689,257, about one ninth of today's figure. In the same year Britain signed the Treaty of Washington with the United States, which settled how the US and Canada could use the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence system and the Yukon River in Alaska. The United States was also given fishing rights in Canadian Atlantic waters for a limited period, in return for $5.5 million.

How did the maple leaf become Canada's national symbol? The ever-resourceful Indians knew about maple syrup, and found it a useful food, because maple trees produce it at the beginning of spring, a time when there isn't much else to eat. Europeans learned this after they arrived, and as early as 1700 French colonists were using the maple leaf as a symbol for New France. In 1826 the Saint Jean Baptiste Society in Quebec adopted the maple leaf as its symbol, the first time it was used officially. By 1867 Ontario had adopted the maple leaf as well, but theirs was gold, to distinguish it from the green maple leaf of Quebec.

The story which tells how the maple leaf became a symbol for all Canadians reminds the author of the legend surrounding Betsy Ross and the American flag; it may or may not have happened that way, but it will do until somebody can produce a better explanation. Anyway, the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII) came to Canada in 1860, becoming the first member of the British royal family to visit the North American colonies. When crowds lined the streets of Toronto to see the Prince, people from England wore a rose on their lapels, while those from Scotland wore a thistle. Canada's symbol at the time was the beaver, but that wouldn't do for a lapel pin, so it was decreed that people born in Canada should wear the maple leaf as their emblem. The idea that the maple leaf could represent all Canadians was a popular one, because the symbol of the maple leaf does not discriminate against any ethnic group, and maple trees grow in every Canadian province.

It may surprise the reader to know that the maple leaf on the Canadian flag is a relatively recent development. For 97 years after independence, the Canadian flag was called the Red Ensign, because it featured the British Union Jack and a coat of arms on a red field. During World War I, an army medic named Lester Pearson noted that almost every battalion in Canada used the maple leaf as part of its insignia. Forty years later, as a diplomat in the United Nations, Pearson helped defuse the Suez Crisis (an act that won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957), and there he noted that the Egyptians refused to accept Canadian troops as part of the peacekeeping force in the Sinai, because the Canadian flag included the Union Jack, a symbol of the hated British. These two incidents, plus a desire among Canada's young people to use symbols that were strictly Canadian, prompted Pearson to vow that he would put the maple leaf on the Canadian flag. He got his chance when he became prime minister. Parliament spent much of 1964 debating what the new design for Canada's flag would look like; the design they settled on, a red maple leaf on a red-and-white tricolor, was not the design Pearson had proposed, but it offended nobody and had no symbols already used by another nation, so it became the new flag, and was first raised in early 1965, at a ceremony attended by the Queen of England.

|

|

| 1868-1921 | 1921-1957 |

|

|

| 1957-1965 | 1965-Present |

The four flags of independent Canada.

The Original Provinces

In the late 1860s and early 1870s, there were more political changes north of the US-Canadian border than south of it. At the end of the Chapter 3 narrative, we noted that there were four original provinces when the Dominion of Canada was created: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Quebec. Ontario and Quebec were a lot smaller than they are today; "Ontario" constituted the northern shore of the Great Lakes, and the peninsula that sticks down between Michigan and New York, while "Quebec" was just the lands drained by the St. Lawrence River and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Because it has the largest population, and because Ottawa is located there (albeit on the border with Quebec), Ontario has often dominated the national government. British Columbia, Newfoundland(6), and Prince Edward Island remained under direct British rule at first; all of them were transferred to the Dominion later on. The islands in the Canadian Arctic also remained British for the time being.

Canada in 1867. From Canadiana.org.

Rupert's Land, the vast area drained by rivers running into Hudson Bay, was still the property of Hudson's Bay Company, a corporation so powerful in this region that since the 1820s, it had printed its own paper money, for use in York Factory and other HBC trading posts. In 1870 Hudson's Bay Company ceded its lands to the Canadian government in exchange for £300,000, mineral rights to lands around the trading posts, and a small percentage of prairie land for farming.(7) Rupert's Land was merged with everything else east of Alaska and British Columbia to become a vast but mostly uninhabited region, the Northwest Territory.

The Red River Rebellion

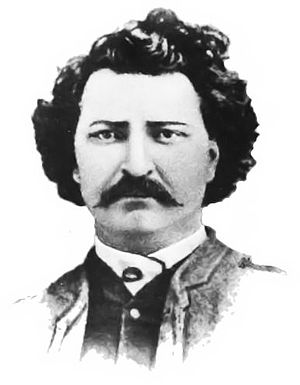

The only part of the Northwest Territory with more than a few people was the former Red River Colony (see Chapter 3), a community of 12,000 Métis (Indian/French hybrids) south of Lake Winnipeg. This area would give Canada its first political crisis, the Red River Rebellion. It started when Ottawa appointed one of the "Fathers of Confederation," English-speaking William McDougall, to be the first governor of the Northwest Territory.(8) Because transportation had not yet been developed west of Ontario, McDougall had to get permission from US President Grant to travel through the United States and enter the Northwest Territory from the Dakotas. The Métis did not like McDougall because he was notoriously anti-French. Near the border he was turned back by the Métis and their leader, Louis Riel (November 2, 1869). Then Riel led 400 Métis to seize Fort Garry (modern Winnipeg) in a bloodless coup, which became the headquarters for a provisional government; Riel was elected president of it on December 27. To Ottawa he sent demands that the religion (Catholicism), other civil rights, and land rights of the Métis be protected.

Though Riel won the first round, there was a pro-Canadian Anglophone minority in the community, made up of settlers from Ontario. Some of them were willing to launch their own counter-rebellion against the Métis rebels, if necessary. Riel arrested and imprisoned some of these opponents, and after thirteen of them escaped in January, he released the rest, but recaptured two of them in February, Charles Boulton and Thomas Scott. Feeling the need to make an example of someone, Riel had Boulton tried and sentenced to death, but then pardoned Boulton when cooler heads persuaded him not to carry out the sentence. The other prisoner, Thomas Scott, had nothing but contempt for his captors, and quarreled so badly with the guards that he was put on trial for insubordination, and convicted of insulting the president, defying the authority of the provisional government, and fighting with his guards. None of these were capital crimes, but this time Riel would not listen to reason, and had Scott shot. This was the only bloodshed in the rebellion; if he had not made the mistake of executing Scott, Riel might have gone down in history as the founder of Manitoba.

Back in Ontario there was anger against the Métis, especially after the execution of Scott, but Prime Minister MacDonald chose to negotiate a settlement with Donald Smith, an English member of the provisional government, and Bishop Alexandre Tache, the religious leader of the Red River colony. McDougall protested that recent events showed the Métis weren't ready to have their own province, but the moderates prevailed, and in May 1870, the Manitoba Act created Canada's fifth province. At this point, Manitoba only constituted a small rectangle of land between Lake Winnipeg and the US border; it was the smallest Canadian province until Prince Edward Island joined the Dominion. Next, a military expedition of more than a thousand soldiers, led by Colonel Garnet Wolseley, was sent to enforce Canadian authority in Manitoba. We already mentioned the lack of roads between Ontario and Manitoba, but a request to go through Minnesota was rejected by the US government (see footnote #4 for why the US said no), so the soldiers ended up traveling by steamer across Lakes Huron and Superior, coming ashore at Prince Arthur's Landing (modern Thunder Bay), and they combined marching with the use of small boats for the rest of the way. Riel fled before the expedition reached Fort Garry, and both his government and the rebellion collapsed. However, Riel would return for a rematch, fifteen years later.

Louis Riel. In modern Manitoba and Quebec he is seen as a folk hero, one of the most complex, controversial, and tragic characters in Canadian history. This picture is from Wikimedia Commons.

British Columbia and Prince Edward Island Enter the Dominion

We saw in Chapter 3 that British Columbia was created as a British colony because of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush in 1858. Unlike the Northwest territory, this area was well-populated; it had the largest remaining Indian communities north of the 49th parallel, to start with.(9) Population continued to grow rapidly in the 1860s, but after the gold ran out, an economic depression set in. The local government was in debt, too, because its expenses grew as it tried to meet the needs of the people. When the United States purchased the Alaska territory from Russia in 1867, the Canadian government grew disturbed. Now the British Columbia faced Yankees on its western border as well as the southern border, would it be tempted to join the United States instead? To keep that from happening, Ottawa would have to make a better offer than Washington might make. It did, and in 1871 British Columbia became the sixth province to join the Dominion, after the Canadian government agreed to assume the colony's debt and build a railroad across the Rockies within ten years, to connect it by land with the rest of Canada.(10) The railroad came a few years late, but otherwise the agreement was kept; construction on the Canada Pacific Railroad began in 1881 (during Prime Minister MacDonald's second term), and was finished in 1885.

Though Prince Edward Island had hosted the first conference that led to the birth of Canada (at Charlottetown, in 1864), it refused to join the Dominion in 1867, calling the terms of union unfavorable. During the rest of the 1860s, the Islanders considered becoming a separate dominion, or joining the United States; meanwhile, they began construction of a railroad they could not afford. Prime Minister MacDonald could not stand the idea of Prince Edward Island falling under the US flag, so he opened negotiations for Prince Edward Island to join Canada. As with British Columbia, a railroad project brought around those folks who had opposed confederation; in this case, it was the Intercolonial Railway of Canada (ICR), which, when completed in 1876, connected Quebec to the Maritime Provinces.(11) By agreeing to take over the railway debt and buy out properties owned by the island's absentee landlords (which was likely to encourage the immigration of workers onto those properties), MacDonald changed the mind of the islanders, and Prince Edward Island became a province in 1873. Despite its reluctant entry, today Prince Edward Island promotes itself to tourists as the "Birthplace of Confederation," using the term "Confederation" on buildings, a ferryboat and the bridge to New Brunswick, to remind everyone that modern Canada got started there.

John MacDonald is rightly seen as the Canadian equivalent of George Washington, because he saw Canada through the difficult early years. However, the railroads he promised were his undoing. A railroad going all the way across Canada required more miles of track than a railroad across the United States, and it placed a heavy financial commitment from a new country that had fewer people and funds to get the job done. After MacDonald was re-elected in 1872, charges surfaced that the Canada Pacific Railway Company had gotten the contract to build that railroad because it contributed $360,000 to the Conservative Party's campaigns (the "Pacific Scandal"). MacDonald was forced to resign as prime minister, and was succeeded by the first Liberal prime minister, Alexander Mackenzie (no known relation to the eighteenth century explorer by that name).

Mackenzie's administration wasn't as impressive as MacDonald's, but because Mackenzie was a tireless, honest worker, he got a lot done. Voting by ballot was introduced in 1874, the Supreme Court of Canada held its first session in 1876, and as we noted above, the Intercolonial Railway was also completed in 1876. Nevertheless, the "old chieftain," John MacDonald, remained popular, and an economic depression began during Mackenzie's term. Consequently Mackenzie lost his re-election bid in 1878, while MacDonald, running on a platform of protectionist tariffs, got his former job back. This time MacDonald kept it until his death in 1891.

The Northwest Rebellion

A commission appointed by the Ontario government recommended in 1874 that the borders of that province be expanded to the north and west, giving it the nearest part of the Northwest Territory. However, because of the poor quality of the maps, nobody was sure exactly where the rivers and other geographical features were, so nothing was done about changing the border while Mackenzie was prime minister, and MacDonald's second administration waited until 1889. By that time a decision was necessary, because thousands of settlers had moved into the area between Ontario and Manitoba, and a dispute developed over which province they belonged to. Manitoba had also been enlarged, giving it the southern third of the land that makes up Manitoba today (1881).

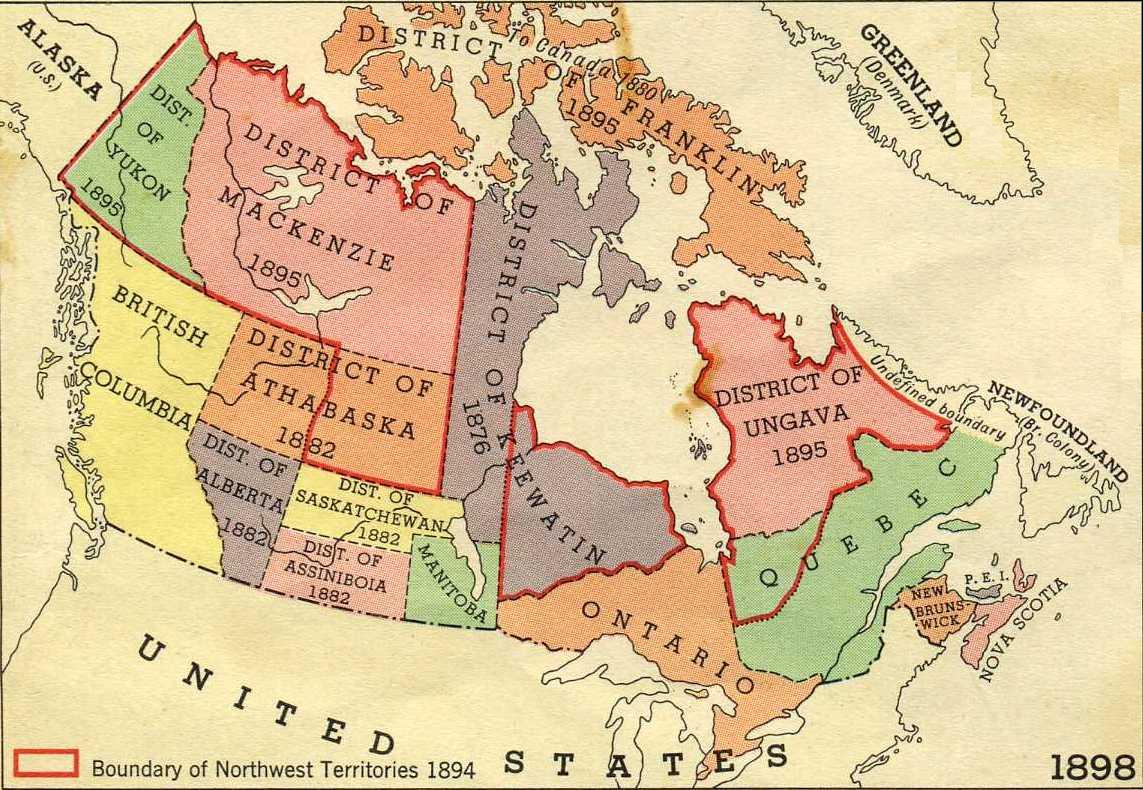

For administrative purposes, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the Northwest Territory was divided into nine districts: the District of Keewatin (1876), District of Alberta (1882), District of Assiniboia (1882), District of Athabaska (1882), District of Saskatchewan (1882), District of Franklin(12) (1895), the District of Mackenzie (1895), District of Ungava (1895), and the District of Yukon (1895).

Canada in 1898, showing the organization of the Northwest Territories.

Meanwhile in Manitoba, the Métis soon realized that despite the promises made by Prime Minister MacDonald to protect their rights, the government was still intent on treating them like second-class citizens, until they became both English-speaking and Protestant. To get away from the authorities, some Métis left Manitoba, moving farther west into Saskatchewan. At Batoche, on the South Saskatchewan River, they found a suitable spot for the farming communities they had in Manitoba, and settled there. Unfortunately for them, English-speaking settlers from Ontario soon followed. Among the newcomers were surveyors who divided the land into the square plots the English were familiar with. This threatened the Métis farms, because they were laid out in long, thin strips (what was called the seigneurial system), to make sure that every farm got a piece of the riverbank. In addition, the Métis and several Indian tribes were alarmed at how white hunters were slaughtering buffalo herds wholesale, because the buffalo had long been the main source of meat for them (see the Pemmican War in Chapter 3).

In 1884 a Métis delegation asked Louis Riel to come back and help them present their grievances to the Canadian government. In the years since the Red River Rebellion, Riel had lived in Quebec, and in various parts of the United States. He was elected three times to Parliament, but since he was a wanted man, he did not dare take his seat in Ottawa. He had also come to believe he was God's prophet, sent to establish a new North American Catholic Church. When the delegation found him, he was a schoolteacher in Montana, a naturalized US citizen, and married with two children. Riel agreed to return and after he did, he wrote letters and petitions to Ottawa; the official response he got back was that a new census would be taken of the territory, and a commission would be sent, to decide what to do. Riel was willing to wait for the results of those inquiries, but for the more hot-headed members of the Métis community, they were just delaying tactics. In March 1885 they set up another provisional government, with Riel as the spiritual and political leader and Gabriel Dumont as the military leader. Then Riel sent representatives to the nearest Indian tribes, asking for their assistance. On March 26, about 300 Métis, led by Riel, clashed with about 100 North West Mounted Police and volunteers, touching off the Northwest Rebellion.

Unfortunately for the Métis, the situation in western Canada had changed since the Red River Rebellion, making it even less likely for their second rebellion to succeed. The main factor was the Canada Pacific Railroad; though not complete in other areas, it was finished in the Great Plains, making it much easier to send troops from the east. Furthermore, a police force, the previously mentioned North West Mounted Police (NWMP), now existed in the troubled area. On top of that, the Catholic Church refused to support Riel, because his religious views had grown too extreme for them, and they persuaded the Blackfeet tribe to stay out of the fight.

By military standards, the Northwest Rebellion wasn't very bloody: 58 Canadian soldiers were killed, as opposed to 70 rebels and Indians dead. The Métis and their Indian allies did well in the first battles and skirmishes, until an overwhelming force of 8,000 men arrived and besieged Batoche. Three days later (May 12, 1885), Riel surrendered; the rebellion had lasted forty-six days. Riel was put on trial for treason in July, and hanged the following November. Riel's trial was the most famous in Canadian history, and since 1885 Catholics and Protestants have debated over whether his execution was justified; some have suggested he was hanged not so much for being a rebel leader, as for his execution of Thomas Scott.

In the east, the Canada (Ontario Boundary) Act of 1889 enlarged Ontario by giving it the nearest portion of the District of Keewatin, so that its northern border touched James Bay. Quebec also was experiencing growing pains; overpopulation in the St. Lawrence valley was encouraging many Québécois to move out. Some went to the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region, and the Laurentide mountains, both of which are north of the St. Lawrence valley; others emigrated to New England. The Quebec Boundary Extension Act of 1898 was Parliament's response; the northern boundary of Quebec was moved up to the eastern shore of James Bay, and the Eastmain and Hamilton Rivers, meaning it had grown by roughly the same amount as Ontario had in 1889.

None of the four Conservative prime ministers after MacDonald was very effective. An election had taken place just two months before MacDonald's death, and the constitution only required elections every five years, so there wasn't another one until 1896. In the meantime, John Abbott resigned after one year because of ill health; John Sparrow Thompson died suddenly of a heart attack, while visiting Queen Victoria in England; Mackenzie Bowell resigned when he could not resolve the political crisis caused by the Manitoba Schools Question; Charles Tupper took over shortly before the 1896 election, so his term in office only lasted sixty-nine days. On top of all that, the economic depression that had started in the 1870s was still going on.

The Manitoba Schools Question was the was the latest episode concerning the rights of French Canadians. The constitution of Manitoba had promised a separate school system for the French, but during the 1870s and 1880s immigration changed the ethnic balance in the province, so that the population was now mostly English-speaking. The newcomers called for an end to the French schools; in 1890 the Manitoba legislature removed French as one of the official languages of the province, and stopped funding Catholic schools. The French Catholic minority called on Ottawa to support their right to have schools of their own, while anti-Catholic groups like the Orange Order approved of the moves to abolish separate schools. The Conservatives proposed remedial legislation to over-ride Manitoba's decision but the Liberals, now led by Wilfrid Laurier, blocked this move, saying it would send the wrong message because it trampled on provincial rights; instead Laurier proposed negotiations between the province and the rest of the country, a process he called conciliation. In the 1896 election, the Manitoba Schools Question was the main issue, and the Liberals won, so Laurier became Canada's first French-speaking prime minister.

The Laurier Years

Wilfrid Laurier was one of Canada's most successful prime ministers. Only John MacDonald and William Lyon Mackenzie King accomplished more, and by winning four elections, he was able to serve for fifteen years (1896-1911), making his administration one of the longest-lived. He also was head of the Liberal Party for a remarkably long time, from 1887 to 1919. Once the Liberals assumed power, Laurier offered a compromise on the Manitoba Schools Question: there would no longer be separate schools, but Catholic students in Manitoba could have Catholic teaching for 30 minutes at the end of each school day, if there were enough of them in any particular school. Though this settled the immediate issue about education for Catholics, tensions over language and religion remained high in the whole country for decades to come.

Elsewhere the news for Canada was better. For the first time in twenty years, the country enjoyed prosperity. Foreign demand for Canadian exports, especially wheat, increased, and immigration brought in enough new workers to meet this demand. This gave Laurier so much confidence that he once proclaimed, "The twentieth century belongs to Canada." To further develop the west, he authorized the building of three new transcontinental railroads: The Grand Trunk Pacific, the National Transcontinental, and the Canadian Northern Railway. However, these projects, like the previous railroads, saddled the government with an expensive burden; that and a lack of improvement in relations between Canada's ethnic groups, caused Laurier's popularity to decline after he was re-elected in 1904. Then in the arms race before World War I, when both Germany and Great Britain were building more ships, the British asked Canada to make contributions for the Royal Navy. Instead of satisfying either the pro-British or the anti-imperialist factions, Laurier passed the Naval Service Act, which created the Royal Canadian Navy in 1910.(13) Finally, Laurier was blessed to be in charge at the time of the Klondike Gold Rush, and when Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces; more about that in the next sections.

The Klondike Gold Rush

As in other parts of Canada, native tribes came to the Yukon region first, followed by fur traders and missionaries. It was prospectors, though, that put the Yukon on the map. Since the gold rush in British Columbia, prospectors had been digging and panning to find another gold deposit; when they didn't find it in British Columbia, they went to try their luck in surrounding territories. Enough small discoveries turned up in the Yukon to encourage them, attract Americans from neighboring Alaska, and start a liquor trade. Concerned about these developments, the Canadian government sent inspector Charles Constantine of the North West Mounted Police in 1894, and he reported that a police force was urgently needed, because a gold rush could happen any day. A year later he brought twenty men to serve as those police, so Canada was ready when the Klondike Gold Rush broke out. Incidentally, the Gold Rush saw the best years for both the North West Mounted Police and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, as they maintained order and patrolled the border, to make sure that only those people bringing enough goods to survive would be allowed in.

In August 1896, a small party of Indians and Nova Scotians made the big discovery, at Bonanza (Rabbit) Creek, in the Yukon region. It took months for news of the gold to reach civilization, but because both the US and Canadian economies were doing poorly at this date, the news spread like wildfire when it got there. Those who caught the gold fever started arriving in the summer of 1897, coming from places as far away as New York, South Africa, Europe and Australia. Some traveled overland from western Canada, while others came by water and landed in Alaska first.

The experience of previous gold rushes showed that most of the gold was likely to go to those who found it before the crowds arrived. Many of the newcomers knew their chances of getting rich through gold were slim, so they came more for adventure than for wealth. Among these folks were William Howard Taft, the future president of the United States, and Jack London, author of The Call of the Wild. Some didn't go any farther than Alaska, choosing to take their chances there, rather than along the Klondike and Yukon Rivers. Consequently it was at this date that Americans stopped thinking that their purchase of Alaska from Russia (see Chapter 4) had been a mistake.

Population boomed so quickly in the District of Yukon that it was detached from the Northwest Territories completely, and renamed the Yukon Territory in 1898. Dawson was the first capital; it was moved to Whitehorse in 1952. This reorganization made sure that Canada would not lose the Yukon to the US citizens coming in, the way the British lost Oregon in the 1840s. A 1901 census put the number of people in the territory at 27,219. However, population dropped after that, because many fortune-seekers moved away when they didn't find gold; unlike California, Colorado, and British Columbia, the cold climate gave them a strong reason to leave if they could not get rich. By 1921 the population was only 4,157. Although it recovered after that, the numbers did not reach gold rush levels again until 1991.

Another side effect of the gold rush was that prospectors found other sources of mineral wealth, in various parts of Canada. To give just two examples, they found nickel at Sudbury, Ontario in 1883, and silver north of Lake Nipissing in the first years of the twentieth century. And while the gold rush may be long over, Canada has remained a major gold producer since then, usually ranked right behind South Africa and the countries of the former Soviet Union. In fact, during the period when South Africa was governed by its apartheid policy, investors saw the Canadian Maple Leaf coin as a safe alternative to the South African Krugerrand, a way to own gold without having to deal with economic boycotts or international politics.

Here Come Alberta and Saskatchewan

As with the American West, the settlers of western Canada were attracted to the Pacific coast first, then they settled the Rockies and the central plains later. By the first decade of the twentieth century, the area between Manitoba and British Columbia had 169,000 inhabitants, so it was ready to be upgraded to provincial status. The only question was: How many provinces would be created there? Prime Minister Laurier thought that if he created just one province, it would be powerful enough to challenge Ontario and Quebec for rule over all Canada, but three provinces would not be economically viable, so he compromised again and created two provinces. The province of Saskatchewan was created by merging the Assiniboia and Saskatchewan districts with half of the Athabaska district, while the rest of Athabaska was joined to the Alberta district to create the province of Alberta. The official date for the establishment of both provinces was September 1, 1905.

After the creation of Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905, the provinces of Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba all said they wanted more territory. In 1912 Parliament passed bills to extend Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba northward to their present boundaries. Ontario and Manitoba got more of the District of Keewatin, extending the northern borders of both to Hudson Bay and making Manitoba comparable in size to neighboring Saskatchewan. Quebec claimed the District of Ungava, arguing that even though only Inuit lived in this area, it was geographically isolated from the rest of the Northwest Territories, and Quebec was in a better situation than any other province to develop the region's resources. Ottawa agreed, and the Quebec Boundaries Extension Act of 1912 gave Quebec everything it wanted, except for the islands in Hudson Bay that were part of Ungava. With the 1912 acts, all of Canada's provinces except Newfoundland assumed their present-day appearance.

World War I, the Conscription Crisis, and the Unionists

Like other Liberals, Wilfrid Laurier wanted free trade with the United States, and introduced a free trade bill, called a limited reciprocity pact, in 1911. Farmers supported the bill, but businessmen opposed it, and Conservatives called it a sell-out; some of the latter even predicted that passing the bill would be the first step toward Canada being absorbed into the United States. To show his government was popular enough to pass the reciprocity bill, Laurier called for an election. Instead he was defeated, and the Conservative candidate, Robert Laird Borden, became the next prime minister.

Three years after the election, World War I began in Europe. Because of its obligations to Great Britain, Canada declared war on Germany on the same day that the British did, but the political parties had different opinions on how much support to give. Normally one would have expected Conservatives to support the British wholeheartedly, while the Liberals would minimize Canada's participation. However, Germany's invasion of Belgium, which had been a neutral nation for the previous 75 years, was brutal enough to make both parties give the war effort their full backing, at least for the short run.

The first Canadian unit, nicknamed "Canada's Answer," numbered 31,200 men, and it went to Britain in October 1914. During the course of the war, more than 619,000 Canadians enlisted(14), and they served with distinction and courage. The battles on the Western Front where Canadian troops saw action included Ypres, the Somme, Passchendaele, Vimy Ridge, Amiens, Cambrai, and Mons. But anyone with at least a passing knowledge of World War I will know its battles were meat grinders, and Canada paid a terrible price for the respect it gained; more than 60,000 were killed, nearly one percent of the country's population at that time.(15) Canada had been independent for half a century, but up until now, many foreigners continued to see it as a British colony(16); the Canadian role in the war did much to change their minds. After the war, Prime Minister Borden successfully lobbied to get Canada its own seat in the new League of Nations.

For two and a half years Canada was able to use an all-volunteer force. By early 1917, however, war weariness was setting in, as it did in Europe, and the supply of willing recruits dried up. It was also noticed by then that the vast majority of Canadians who enlisted were English-speaking. French Canadians were not enthusiastic about fighting alongside the British, because they did not consider Britain their mother country; nor did they want to serve in units that were mostly English-speaking and Protestant. A few French-speaking units were available, but overall the Canadian armed forces were only 5 percent French, though French Canadians currently were 28 percent of the population back home.

In 1917 Prime Minister Borden decided that the only solution was conscription, both to get the number of soldiers needed and to make French Canadians pull their weight, so in August the Military Service Act was passed. This led to what is now called the Conscription Crisis of 1917. As with other issues, Canadians split along ethnic lines; Anglophones (English-speakers) thought it was time that Francophones (French-speakers) did their share for the war effort, while French Canadians bitterly opposed the act.(17) Opposition to conscription was strongest in Quebec, where Henri Bourassa, a French Canadian nationalist, told Francophones that their only loyalty was to Quebec; they could enlist to fight in defense of France, if they wished, but they must not be forced to do it.(18)

Borden needed widespread support to implement conscription, so he called an election for December 1917, and formed a "Union government," made up of members of Parliament who supported the war from all parties. This was a lot like the National Union Party that Abraham Lincoln created, for the 1864 presidential election in the US. With the Canadian example, Borden persuaded several independents and Liberals (though not Liberal leader Laurier) to join him, and changed the name of the Conservatives to the Unionist Party. The result was a whopping 2-1 victory for the Unionists; the Laurier Liberals won 82 seats in Parliament (62 of them from Quebec), but the Unionists got 153. Afterwards, in early 1918, the government started enforcing the Military Service Act, but the 125,000 men it conscripted were far less than the number expected, and the war ended before most of them could be sent to Europe. Meanwhile, the Conservatives and pro-war Liberals continued to use the "Unionist" label until the next election, held in 1921.

Borden retired in 1920, and was succeeded by Arthur Meighen. Meighen was the first prime minister to be born after Canada became independent, and the only one from Manitoba, but he held the job for just a year and a half, because he could not keep non-Conservatives in the Unionist camp. This group protested high tariffs on farm products, and did not like Meighen's role in how the government had violently put down the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. Consequently those who supported the farms and labor unions broke away to form a third party, the Progressives. In the 1921 elections, the Conservatives came in third place; both the Liberals and Progressives won more seats than they did. Laurier had died in 1919, so the man who succeeded him as the Liberal Party leader, William Lyon Mackenzie King, became the new prime minister.

The Mackenzie King Era

William Lyon Mackenzie King was the Canadian equivalent of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He had a long name because he was the grandson of William Lyon Mackenzie, leader of the 1837 Upper Canada Rebellion (see Chapter 3). Between 1921 and 1948 he was prime minister three times, for a combined total of 22 years, the longest tenure of any Canadian prime minister, and he saw the country through both the Great Depression and World War II. In childhood he chose for his motto "Help those that cannot help themselves," so like FDR, he saw himself as a champion of the ordinary man. Mackenzie King was mild-mannered and dull in public, but in private he showed some exotic tastes; he was both a devout Christian and a firm believer in the occult. After his death it was revealed that during World War II, he tried more than once to contact his deceased mother and dog with a crystal ball, to get advice on policy matters.(19)

Mackenzie King got his start in politics as soon as he got out of college. While a student, he met nine of his future cabinet ministers as well as his future rival, Arthur Meighen. Wilfrid Laurier saw him as a expert on labor questions, and appointed him as deputy minister of labor (1900-1908) and minister of labor (1909-11). In 1909 he also began his first term in the House of Commons, and during World War I, it was his job to travel between Canada and the United States, keeping war-related industries running smoothly in both countries. In 1919 he was chosen to succeed Laurier as leader of the Liberal Party, and he kept that job until he retired in 1948.

Mackenzie King's first administration had a weak majority in Parliament, 118 out of 235 seats. With the 1925 election, the Conservatives won more seats than the Liberals, but not a majority; Mackenzie King formed an alliance with the Progressives to keep the Conservatives from regaining control.(20) But then a few months later, one of his appointees in the Department of Customs and Excise was revealed to have taken bribes. This scandal led to a constitutional crisis, in which the Progressives withdrew their support of the Liberals, and King was forced to resign; the governor general, Lord Byng of Vimy, called on the Conservatives to form a new government. Meighen became prime minister again, but the Liberals remained more popular than the Conservatives, so when Meighen failed to win a no-confidence vote, new elections took place in 1926. This time the liberals won, and King returned; Meighen's second term as prime minister only lasted twelve weeks.

The advanced nations of the world enjoyed significant progress and economic growth in the 1920s, only to see it stop suddenly when the New York Stock Exchange crashed in 1929. Canada was no exception to this rule. Mackenzie King's government could not do anything about rising unemployment, and he responded to criticism from Conservatives by saying he "would not give a five-cent piece" to Tory provincial governments. This offended so many voters that when elections were held in 1930, the Liberals were turned out, and the Conservatives got another chance to rule.

Unfortunately for the Conservatives, they took over in the middle of the Great Depression, and could not find a solution. The Conservative prime minister, Richard Bedford Bennett, thought that he could jump-start the economy by increasing trade with the British Empire and the Commonwealth, and imposing tariffs on any imports which did not come from those countries. When this did not work, he could not offer any other ideas, and his party, being pro-business and pro-banking, was reluctant to offer much help to the unemployed, believing that workers would then be less inclined to look for jobs. What the government did try was a Canadian version of the US Civilian Conservation Corps, where single, unemployed men went to military style camps in the countryside, and labored at make-work projects for twenty cents a day. To do more than that was the responsibility of provincial and local governments, but being broke, they were not up to the task. In addition, a severe drought ruined crops in the central plains (what Americans called the "Dust Bowl"). Finally, Bennett rubbed many folks the wrong way, with his impersonal style and his habit of showing his wealth openly.

When protest movements sprang up in the provinces, Bennett used Section 98, a controversial law passed after the Winnipeg General Strike, to break up even non-violent demonstrations and arrest its members, because he saw these movements as fronts for socialist and communist subversion. Instead this only caused more disorder; Tim Buck, the Communist Party leader, was seen as a civil rights hero after shots were fired through his cell window during a prison riot, and communists started infiltrating even the work camps. In April 1935 they persuaded camp workers in Vancouver to go on strike and begin what they called the "On-to-Ottawa Trek," taking their grievances directly to the national government. 3,000 of them and their supporters got as far as Regina, Saskatchewan, where the government called out the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to stop what it saw as an insurrection; in the confrontation on July 1, two protesters were killed and dozens were wounded.

Bennett's advisors, especially his brother-in-law and the Canadian ambassador to the US, looked across the border at all the activity and experimentation that Franklin Delano Roosevelt's administration was doing in the United States, and eventually they persuaded the prime minister to try a program like that. In a series of speeches he made in January 1935, Bennett declared that the world had changed to much for old solutions to work anymore, and announced his own "New Deal" for Canada. Like the American New Deal, this would mean greatly increased government spending and intervention in the economy, and innovations like an income tax with a rate that increased when one's earnings increased, a minimum wage, a limit on the number of working hours in a week, insurance for health, unemployment and retirement, and farming subsidies. Though this sounds ambitious, for most voters it was too little, too late to save the government. Just as US citizens in the early 1930s named substandard products after Herbert Hoover (e.g., shantytowns were called "Hoovervilles") so Canadians named things that didn't work after Bennett; for example, when drivers could no longer afford gasoline, they hitched their vehicles to horses and called them "Bennett Buggies." As you might expect, the next election (held in October 1935) was a liberal landslide; campaigning on the slogan "King or Chaos," the Liberals won 173 seats, compared with 40 seats for the Conservatives. Mackenzie King came back to begin his third term as prime minister, and the Liberals, like the Democratic Party in the US at that time, would be in control for two whole decades.

If you look at the table of prime ministers in this chapter, you will see that many of them were eventually knighted by the British Crown, allowing them to put the title "Sir" before their names. Well, Richard Bennett improved on that; he was the only head of state in both US and Canadian history who moved out of the country after leaving office. Apparently tired of life in Canada, he retired to England, where he was elevated to the rank of viscount. Now called Viscount Bennett, he became the only Canadian prime minister to join the House of Lords in London. Then after he died in 1947, he ended up being the only Canadian prime minister who is not buried in Canada.

Ironically, the reforms introduced by Bennett accomplished more than those of Mackenzie King; most of the latter were blocked by both Liberal and Conservative courts. In the end, the beginning of World War II, with the vast mobilization and increase in industrial production it required, did more to lift Canada out of the Depression than any government program did.

Before the war, Mackenzie King supported the policies of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who believed that war could be prevented by appeasing Nazi Germany. So did the Canadian people, but soon events in Europe caused them to feel more sympathy for Germany's victims (read: Czechoslovakia, Poland, and France). When the war came, Canada was not expected to automatically enter the war in lockstep with Britain, and at first Mackenzie King declared the nation neutral, but he believed that the Canadians would soon follow the British; the neutrality declaration gave Parliament a few extra days to discuss the matter. Sure enough, on September 10, 1939, exactly one week after Britain declared war, Canada's Parliament voted to declare war on Germany. This time, to prevent another conscription crisis like the one in the last war, Mackenzie King promised that conscription would only be done to defend the homeland; no drafted troops would be sent overseas.

Not having seen action in twenty years, the Canadian armed forces had run down so badly since World War I that they needed to be rebuilt from scratch. In 1939 there was a permanent militia of only 4,261 men, and a reserve force of 51,000. During the war, they managed to recruit and train 1.1 million men and women, for the Army, Navy, and Air Force, and build at least 400 ships and 14,000 airplanes(21); 131,000 personnel also served in the Royal Air Force for Britain. However, more than half of the Army and three quarters of the Air Force stayed in Canada; not only was this because of the prime minister's policy to delay conscription for as long as possible ("Conscription if necessary, but not necessarily conscription."), but because this time there was no Western Front in Europe to send the troops to, after the French collapse in June 1940. On other fronts, like North Africa, the British were usually able to draw enough troops from other Commonwealth countries that the Canadians weren't needed.(22)

The first Canadian division arrived in Great Britain before the end of 1939, but for most of the war Canadians only did garrison duty, guarding the mother country during its finest hour. Aside from that, the most important part they played was defending the sea lanes, during the Battle of the Atlantic; they also took part in bombing missions over Germany. However, the first place where Canadian soldiers saw action was unintentional; in November 1941 two battalions, the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers, were sent across the Pacific as reinforcements for the Hong Kong garrison, where they were besieged and captured by the Japanese one month later.

A good symbol of wartime cooperation; this picture of a Mountie and a US state trooper was taken in 1941. This is a public domain photo from Wikimedia Commons.

As early as the 1920s, proposals were made to build a road that would connect Alaska, Canada, the "Lower 48" states, and possibly even Russia (using a bridge or tunnel across the Bering Strait), but during the Great Depression, it seemed pointless to build such a road when only a few thousand people lived in the area that would benefit. Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor changed that point of view; both the US and Canadian governments were now convinced that better transportation was needed for the northwest corner of the continent. Canada agreed to allow the project if the United States would pay the costs, and turn the Canadian portion of the road over to Canadian authorities after the war ended. The route decided on for the Alaska Highway (also called the ALCAN Highway) started at Dawson Creek, in northeast British Columbia, ran through the Yukon Territory, and ended at Delta Junction, AK, where it connected with Alaska's Richardson Highway. Construction on the Alaska Highway began in 1942, and the initial road, running 1,423 miles, was declared complete by the end of the year.

Despite this success, the Alaska Highway wasn't a "highway" like the Interstates connecting major US cities today. Besides the obvious rush job, it was built on extremely difficult terrain.(23) Many areas had steep grades, and used switchbacks to get over hills; guardrails and steel bridges were rare. Most of the road was surfaced with gravel, instead of asphalt, and log roads were used in some places where permafrost presented an additional challenge. Since the initial completion, repairs and upgrades have been done on the road almost constantly. The Alaskan portion of the road was paved over in the 1960s, while it took until the 1980s to give the Canadian portion a modern surface. Some efforts have also been made to shorten the highway, by building new sections that follow a more direct path. Even so, it is a two-lane road that often lacks center lines and wide shoulders, so driving on it is a modern adventure. Some visitors choose to take the Alaska Highway one way, and use the ferries connecting southern Alaska with British Columbia and Washington State for the other part of the trip.

Now back to the narrative. In Europe, Canadians were involved in the disastrous Dieppe raid on northern France in 1942; then in mid-1943, they participated in the campaigns to liberate Sicily and Italy, alongside American and British troops. With the D-Day invasion, of the five divisions that came ashore on the first day, the Canadian division got the farthest inland, and suffered the heaviest casualties.(24) After the liberation of France, the First Canadian Army defeated the Germans in the five-week battle of the Scheldt, which liberated northern Belgium and the southern Netherlands in late 1944. Finally, the First Canadian Army fought on both sides of the Rhine in early 1945, joining the Americans, British, French and Russians in overrunning the Third Reich.

As time went on, the government realized it would have to break its promise not to send conscripts overseas, in order to bring the war to a successful conclusion. Fortunately, tensions over the conscription issue were less than they had been during World War I. For one thing, the volunteers from Quebec got to serve in all-French units this time. In the end, Mackenzie King held a plebiscite to see how the public felt on the matter, and every province except Quebec voted for conscription, if necessary. That need came up with the manpower demands after D-Day, but by then the end of the war was in sight. It probably also helped that while 42,000 Canadians were killed in World War II, this was less than in World War I, and in terms of population, Canadian casualties were proportional to the losses suffered by the United States.

The heads of state who attended the Quebec conference of 1943. In the front are US President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Earl of Athlone, the governor general of Canada. Behind them are Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, and British Prime Minster Winston Churchill. This is a public domain photo from Wikimedia Commons.

The Dominion of Newfoundland

Newfoundland made a more complete break with Canada than the other colonies that initially refused to join. Like Texas, it was even an independent country for a while. In the elections of 1869, twenty-one Anti-Confederate candidates and nine Conservative (pro-Confederation) candidates were elected to the local legislature, the House of Assembly; the overwhelming Anti-Confederate majority ended discussions about joining Canada for the time being. In 1892 Canadian Prime Minister John Thompson came very close to negotiating Newfoundland's entry, but that fell through as well.

Great Britain granted dominion status to both New Zealand and Newfoundland in 1907. However, the Dominion of Newfoundland was never a successful proposition; its main accomplishment was sending the 1st Newfoundland Regiment to Europe, where it fought bravely in World War I. Diplomatically, it had trouble getting along with everybody but the mother country. When a trade agreement was negotiated with the United States, Canada objected, and Britain kept the agreement from taking effect. In addition, there was the previously mentioned dispute over Labrador's frontier (see footnote #6), and Newfoundland never joined the League of Nations. The local economy was dependent on the export of fish, paper and minerals, so when demand for those products dropped during the Great Depression, the economy was ruined beyond repair. In 1932 a mob of 10,000 marched on the House of Assembly, forcing the current prime minister, Sir Richard Squires, to flee; Squires was voted out of office later in the same year. The British decided that Newfoundland's government was too corrupt to permit a recovery, and resumed direct rule in 1934. After that the Dominion of Newfoundland existed in name only; it is one of the few countries in history that gave up self-rule without a fight.

Because of its strategic position in the north Atlantic, Newfoundland became an important island during World War II. Two Newfoundland regiments were raised and sent to Europe, the Americans and British built military bases here, Canada provided an occupation force to defend the island like the occupation force the Americans had on Greenland and Iceland, and Newfoundland was the place where Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill had their first meeting in 1941. All the activity from incoming ships and servicemen created jobs, so prosperity quickly returned. Before the war ended, Newfoundland even loaned some money to London. Many Newfoundland girls married American soldiers and sailors, and a new political party was formed, the Economic Union Party, which called for economic union with the United States. Members of other parties denounced the Economic Union Party as republican, disloyal and anti-British, and in the elections concerning Newfoundland's status (see below), Britain refused to give voters a chance to choose union with the U.S. The US government stayed out of this affair, because wartime cooperation with the British and Canadians was more important than an opportunity to make Newfoundland the 49th state.

After World War II the Newfoundland National Convention was held to determine Newfoundland's future. Meeting from September to December in 1946, it adjourned without deciding whether to remain under British rule, or restore the pre-1934 government. A third option, joining Canada, was introduced by one of the delegates, Joseph Smallwood, after the convention started, but it was voted down; a proposal to join the United States was even less popular. Instead of staying quiet, Smallwood gathered 5,000 signatures on a petition within two weeks, and sent it to London. London's response was to announce that it would not give Newfoundland any more financial assistance, and it arranged for a special election to decide the matter.

When this plebiscite was held (on June 3, 1948), nobody won: 44.5% voted to restore the dominion, 41.1% voted for confederation with Canada, and 14.3% voted to stay with Britain. Thus, it was decided that a runoff election would be necessary; this time the only choices would be dominion or confederation. Before the second plebiscite happened, though, a rumor spread that Catholic bishops, who were pro-dominion, were trying to influence the voting. The Protestant Orange Order called on its members to vote for confederation, to keep the bishops from getting what they wanted, and because Newfoundland's population was 2/3 Protestant, that settled it. The second plebiscite, held on July 22, 1948, resulted in a vote of 52% in favor of confederation, and Newfoundland joined Canada as the tenth province on March 31, 1949.

This is the end of Part I. Click here to go to Part II.

FOOTNOTES

1. The warm current passing British Columbia, and the mountains blocking much of the cold air from the Arctic, have given Vancouver the balmiest climate in all of Canada. This led to a problem when the 2010 Winter Olympic Games were held in Vancouver--no snow! Fortunately enough snow was brought in by the truckload for the games to go on.

2. "If some countries have too much history, we have too much geography."--Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King

3. Perhaps the best example of good US-Canadian relations is in the two national parks on the Alberta-Montana border. In 1932 Alberta's Waterton Lakes National Park was joined with Montana's Glacier National Park to become the world's first international peace park.

4. It must have helped that by the time the British turned Canada loose, Americans had lost interest in expanding northward, now that they were fully involved with exploiting and settling the lands they had acquired in the west. One group of Americans who still wanted Canadian land in the 1860s were in Minnesota; they thought the Red River colony, later called Manitoba, belonged to them, due to questions over where the boundary defined by the 1818 treaty actually ran. Such sentiments faded after the Red River Rebellion of 1869-1870 failed. Possibly the last American to covet Canada was Donald Trump, after he was re-elected president in 2024.

5. British control of Canadian foreign policy ended in 1931, when London passed the Statute of Westminster. This gave all six of Britain's Dominions (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa and Ireland) the right to control their own affairs, both internal and external. After this they only remained allies because the British Crown was the ultimate authority over all of them.

6. The part of the Atlantic coast on the mainland north of Newfoundland, called Labrador, became part of Newfoundland in 1809; this region has always been too poor and underpopulated to stand on its own. However, the boundary line between Labrador, Quebec, and the Northwest Territories was undefined and disputed, until a 1927 treaty drew today's border. In recent years roads have been built between the Labrador communities (the so-called "Trans-Labrador Highway"), but currently they are not up to the standards of highways in other parts of North America, and are not recommended for inexperienced travelers.

7. This ended the Company's role in Canadian history. For the next century and a half, Hudson's Bay Company ran more than one chain of department stores, becoming the Canadian equivalent of Sears or Wal-Mart. Those department stores were called The Bay, Zellers, Home Outfitters and Fields. In 1957 the HBC moved its headquarters and archives of the fur-trading era, from York Factory to Winnipeg, Manitoba. It was the crises of the 2020s that finished off the HBC: first the COVID pandemic, and then the trade war between Canada and the United States, during the second presidency of Donald Trump. By June 2025 the last of their stores had closed. The final score: the HBC was in business for 355 years, from 1670 to 2025.

8. "Fathers of Confederation" is the term Canadians have given to those who attended the conferences in Charlottetown, Quebec City (see above) and London before 1867. They play the same role in Canadian history as the "Founding Fathers" play in US history.

9. Among the Native American tribes of the Pacific Northwest, wealth is not measured by how much a person has, or by how much he can borrow (modern society's standard), but by how much he can give away. This led to an unusual festival called a potlatch (from the word patshatl, meaning "a gift" or "giving"). The typical potlatch had plenty of food and ceremonial dancing, but the main purpose of such gatherings was to redistribute the tribe's wealth. A guest coming to a potlatch would be loaded with fine food and gifts, and if he wanted to show himself equal or superior to the host, he would have to throw his own feast later, in which he would give away at least as many goods as the first host did.

Originally the gifts handed out at potlatches were mostly foodstuffs, feathers, blankets and canoes. After the white man introduced metallurgy and manufactured goods, the number of gifts multiplied, so in the nineteenth century, potlatches became orgies of destruction, as Indians tried to outdo one another in what they could destroy or give away. Sometimes the hosts even killed their slaves or burned down their own houses, in this game of one-upmanship. One story tells how the host of a potlatch brought out his most prized possession, a large engraved copper plaque, had it smashed, and gave the pieces to two rivals. The rivals were immediately shamed, because they did not have anything of equal value to get rid of. One was so shocked that he dropped dead on the spot, while the other shut himself up, living in seclusion and misery until he died six months later. Thus, the potlatch host killed two opponents without using any sort of weapon.

Christian missionaries and government agents denounced potlatching as both wasteful and barbaric, so in 1885 the Canadian government banned potlatching; the United States banned the practice for a while, too. This had the opposite effect of what the authorities wanted; potlatches became more popular than ever, now that attending them could be seen as defying the white man. The tribal communities of British Columbia were too large to patrol effectively, so potlatching could not be suppressed; it was also pointed out that sometimes old and sick natives only got good meals at potlatches. After the tribes outlawed acts of murder and arson during potlatches, the government stopped trying to enforce the ban. In 1951 the ban was lifted, and for the first potlatches after that, only old members of the tribes showed up. Today's potlatches are well attended, but now the main purpose of them is to preserve the culture of the Pacific Northwest Indians.

10. When the route of the Canada Pacific was being planned, one proposal called for having part of the track go through the United States, via Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan's Upper Peninsula. Proponents of the southern route thought this would be an easier place to build a track, than across the Canadian Shield, the huge rugged plateau north of Lake Superior. The proposal didn't last long, because of national pride; after all, the main purpose of the railroad was to show that Canadians could go west without US help.

11. At first the ICR ran from Quebec City to Halifax. Later it was extended to Montreal.

12. The District of Franklin was mostly made up of Arctic islands. Britain transferred these to Canadian rule in 1880; Norway had a claim to the northernmost islands until 1930.

13. But only two warships, the Rainbow and the Niobe (both cruisers), and two submarines were ready for action when World War I broke out. Two Coast Guard vessels were drafted into service at that point, bringing the number of naval vessels up to six.

14. Most went straight to the Canadian Army or Navy, but 22,000 also served in Britain's Royal Air Force.

15. A astonishing number of those casualties were right at home. On December 6, 1917, an unloaded Belgian supply ship collided with a French munitions carrier in the harbor of Halifax, Nova Scotia. The resulting ignition was bad enough, but then the burning French ship drifted to shore, crashed into a pier, and set off more munitions stored there. The resulting explosion has been estimated at 2.9 kilotons, a blast equivalent to that produced by 2,900 tons of TNT. This obliterated 500 acres of buildings in Halifax, caused a 60-ft. tsunami, and created a "pressure wave" of air that snapped trees, bent iron rails, demolished buildings, and grounded vessels. The next day, one of the worst blizzards ever recorded in Halifax began, lasting for six days. Altogether 1,900 people were killed and at least 9,000 were injured, from one of the greatest accidental explosions of all time. You may want to compare this with the blast in Mobile, Alabama, at the end of the US Civil War.

16. 7,400 Canadians served in South Africa during the Boer War, of which 224 were killed and 252 were wounded. As in World War I, English-speaking Canadians were far more willing to fight for the British Empire than French Canadians were.

17. Francophones remembered the Manitoba Schools Question, and some said they did not want to send troops to fight in the war until they "got their schools back."

18. Bourassa was the grandson of a French Canadian nationalist that we saw in Chapter 3, Louis-Joseph Papineau.

19. We know Mackenzie King's real personality because he would have been a great blogger if he was alive today. His hobby was writing in his diary, and from 1893, when he was an 18-year-old student, until a few days before his death in 1950, he composed 30,000 diary pages; that's one or two pages for every day of his adult life. In his will, the prime minister asked that the diaries be destroyed, except for certain parts that could be used by others, but he did not specify which parts those were. Consequently, the whole set of diaries was photographed and put on microfiche, and eventually made public. Now, thanks to the fact that we live in the Information Age, you can access the diaries on this website.

20. The way Mackenzie King saw it, Progressives were "Liberals in a hurry," temporarily separated from the party that was their real home.

21. Canadian raw materials were more important to the war effort than manufactured goods. Half of the aluminum and ninety percent of the nickel used by the Allies came from Canada.

22. German U-boats sank four vessels in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1942, and fired a torpedo at a dock on Bell Island, off the coast of Newfoundland. On the other side of Canada, a Japanese submarine attacked a lighthouse on Vancouver Island in 1942, and Japanese balloons carrying incendiary weapons were floated across the Pacific, with some reaching British Columbia and the west coast of the US.

One German U-boat crew came ashore on the mainland without being detected, and incredibly, nobody else knew about their visit for nearly forty years. In 1943 the Germans realized they needed the ability to predict storms as effectively as the Allies did, so they built a series of automated weather stations. Two of those stations were supposed to go behind enemy lines in North America, to monitor the weather in the western Atlantic, but one of the U-boats assigned to deliver them sank. However, the other U-boat, U-537, made it to the frozen wastes of northern Labrador, and its crew set up their weather station, naming it "Kurt," after Dr. Kurt Sommermeyer, the meteorologist in charge of the expedition. After they left, the station worked for two weeks, before the batteries powering it ran down. Because of the remote location, no Canadians found the station until some archaeologists stumbled upon it in 1977, and they were fooled into thinking it belonged to their own government, because the Germans disguised it by marking it as property of the "Canadian Weather Service!" Only in 1981 was the station correctly identified, by a retired engineer writing a book on Nazi weather stations. You can read more about this extraordinary incident here, and see what's left of weather station Kurt at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

23. The original road crossed the Yukon-BC border six times in one six-mile stretch.

24. One of the Canadian veterans of D-Day was James Doohan, best known for playing Scotty on "Star Trek." He lost a finger to machine gun fire on that day, and managed to hide the missing digit from the camera for his whole acting career.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

The Anglo-American Adventure

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|