| The Xenophile Historian |

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 4: Industrial America, Part IV

1861 to 1933

This paper is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| America's Most Difficult Years | |

Part II

| Reconstruction | |

| The Free State of Van Zandt | |

| The Alaska Purchase, and the Only American Emperor | |

| Grant and the Beginning of the Grand Old Party Era | |

| The Brooks-Baxter War |

Part III

| The Panic of 1873, and the Barons of Wall Street | |

| The South Restored, and the Worst Happy Hunting Grounds | |

| The Great Railroad Strike | |

| The Spoils System Kills the President | |

| Grover the Good | |

| "I Will Fight No More Forever" | |

| The Great Barbecue | |

| The Gay Nineties |

Part IV

| The Spanish-American War | |

| Teddy and the Big Stick | |

| Big Taft and the Bull Moose | |

| Wilson the Reformer | |

| World War I | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part V

| The Age of Normalcy Begins | |

| The Roaring Twenties | |

| The Great Depression | |

| The Golden Age of Immigration |

The Spanish-American War

Now that the United States reached from "sea to shining sea," and tamed the West, what would it do next? Did the nation have to stop expanding? Many thought not. Maybe the USA could keep on advancing, south into Central America and the Caribbean, and west into the Pacific! One congressman, Lucas Miller of Wisconsin, predicted that the USA would keep on expanding until it ruled the whole world, and proposed changing the country's name, to the United States of Earth!

As with the European empires of the Victorian Age, Americans were motivated to expand their frontiers for a variety of reasons: the doctrine of "Manifest Destiny," the Darwinian idea that "survival of the fittest" applied to nations as well as animals and businesses, the rapid growth of American trade and investment overseas, concern about being closed out of the world market by the other empires, and that curious mixture of idealism and imperialism which made Westerners feel it was their duty to bring "Christianity, civilization and commerce" to underprivileged people. Finally, many Americans read the books and articles written by Captain Alfred T. Mahan, which emphasized the importance of sea power in the success of the world's greatest nations. The Assistant Secretary of the Navy under McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, was a follower of Captain Mahan's teachings.

The first move in the Pacific expansion has already been covered, the acquisition of Alaska. In the 1880s and 1890s the US, Britain and Germany had a three-way rivalry over Samoa, which lasted until Britain dropped its claim, allowing America and Germany to divide the islands between them.(66) Then in 1893 American immigrants ousted the last monarch of Hawaii, Queen Liliuokalani, and petitioned to join the US. Unfortunately for them, Grover Cleveland had just begun his second term as president, and he opposed imperialism. Not long after that, Cleveland enforced the Monroe Doctrine by pressuring the British to stop interfering in the affairs of Nicaragua and Venezuela. Meanwhile in Hawaii, the leaders of the coup had to settle for being an independent republic until the summer of 1898, when McKinley signed a treaty of annexation. In 1899 the McKinley administration issued the Open Door policy, which promised that the United States would prevent other foreign powers from interfering any more in Chinese affairs, in return for a promise from China to allow equal trade access for all nations.

Maybe there wasn't a good place to pick a fight in the Pacific, but the Americans found one closer to home--Cuba. Cuban nationalists had been agitating for independence from Spain for a generation, and they revolted in 1895. Spain reacted with cruelty, interning 400,000 Cubans in concentration camps, where at least half of them died. The newspapers of the day found that atrocity stories were a great way to boost circulation, so they kept on publishing them, until most Americans favored intervening on the Cubans' side. McKinley, Mark Hanna and other American leaders didn't want a war, because the economy had just come out of a depression and war might be bad for business, but the popular pressure was enough to make McKinley issue this ultimatum after he took office: if Spain didn't win the war, or negotiate a settlement with the nationalists, it could soon expect US intervention. Over the course of 1896 and 1897, Spain kept control of Cuba's cities with nearly 200,000 troops, 5/8 from Spain and the rest from a loyal Cuban militia, but the rest of the island was captured by 50,000 Cuban rebels, so Spain chose to negotiate.(67)

This was the situation when a small American battleship, the USS Maine, arrived in Havana Harbor. Neither the Spaniards nor Cubans had invited the Maine there, but they acted like they were pleased to see the ship, while the real purpose of the Maine's visit was to protect US citizens and their money and property, should the rebellion reach Havana. On February 15, 1898, the Maine suddenly blew up, killing 266 of her crew. The cause of the blast wasn't known, and it wasn't until 1976 that a naval inquiry declared it was probably a spontaneous explosion in the ship's coal bunkers, which set off a nearby magazine. Back then, however, few Americans believed it was an accident, and the "yellow journalism" press argued that Spain must have set off a mine under the Maine. Spanish officials immediately protested that they would never do such a thing, but by now the American mood was, "Remember the Maine, to hell with Spain!" On April 11 President McKinley reluctantly asked Congress to declare war.

The USS Maine (before the explosion, of course).

The United States only had 25,000 troops available when war broke out, and because it would take time to recruit and train more, the job of winning the war fell on the Navy, which would be used to blockade Cuba and other Spanish colonies until the larger Spanish armies were forced to surrender. Captain Mahan couldn't have asked for a better opportunity to test his theory. Accordingly, long before war was declared, Roosevelt ordered Commodore George Dewey to lead a squadron to Manila and attack the Spanish Asiatic fleet there, making sure that the first battle would be fought on the other side of the world from Cuba. Then he resigned his navy post, went to Tampa, FL and joined the Rough Riders, a volunteer cavalry regiment he had helped organize.

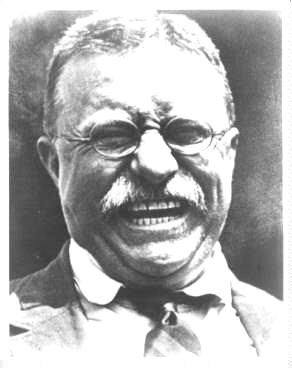

Rough Rider Roosevelt.

The blockade was a complete success, and because Spanish troops in Cuba were concentrated on the western half of the island, the decision was made to attack on the east side, at the harbor of Santiago de Cuba. 15,000 US soldiers began landing there on June 20, and the most important battle of the war, the battle of San Juan Hill, took place on July 1, driving the Spaniards from their defensive positions before Santiago.(68) The Spanish commander in Santiago ordered the local admiral to attempt an escape, so his ships wouldn't be captured, but they came out of the harbor one at a time, and the waiting American warships easily picked them off. Seven Spanish ships were sunk, while only one American seaman was killed. There was a notable moment when the USS Texas sailed by the burning Vizcaya, and Captain John W. Philip told his crew, "Don't cheer, men, those poor devils are dying!"

Santiago de Cuba surrendered on July 17; on July 25 a force of 3,300 US soldiers landed on Puerto Rico and occupied that island with little resistance. One day later the Spanish government asked for terms, and both sides agreed to an armistice on August 12. In the Philippines, American forces, unaware that the war was over, captured Manila on August 13. The Spanish-American War had lasted just four months, and was the most lopsided victory in US history. Of the 3,289 reported American casualties, only 1/8 had been combat deaths; most of the rest had been caused by tropical diseases and the bad canned meat sold to the army by meat-packing firms (soldiers claimed the meat was "embalmed beef" left over from the Civil War). American morale was also high because of a new feeling of solidarity; Northerners and Southerners, whites and blacks had joined together and fought for a common cause. The US ambassador to Britain, John Hay, summed it up in a letter he wrote to Roosevelt: "It has been a splendid little war." When the peace treaty was signed in December, Spain handed over to the US all its colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific: Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. This was followed up with the 1899 annexation of Wake Island, a coral atoll previously claimed by nobody, but useful as a stepping stone between Hawaii and Guam. The 400-year history of the Spanish Empire was now over. Meanwhile, Roosevelt used his new-found fame to run successfully for governor of New York when he returned.

A funny thing happened on the way to the Philippines. Citizens of any country show a double standard in wartime. Normally if a person kills somebody and takes his property, he is a thief and a murderer, subject to the penalties of the law; however, if he does the same thing to enemy soldiers, we praise him as a hero and a patriot. At some point, nations seem to realize that this is inconsistent, and when they do, they stop expanding. With America, it happened in the Philippines. Previously, the United States was barely aware that the Philippines existed, and American soldiers arrived in the archipelago to find themselves facing a local nationalist movement, which had declared independence for the islands in the middle of the war. Some Americans (mainly Democrats) felt that the Filipinos should have independence immediately, because their nationalists were every bit as legitimate as the ones that created the United States in 1776. A majority in Congress, however, thought that the Philippines could not yet stand on its own. One of them, Senator Albert J. Beveridge from Indiana, voiced this with a blatant imperialist speech:

"Mr. President . . . God has not prepared the English-speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing but vain and idle self-contemplation and self-admiration. No! He has made us the master organizers of the world to establish system where chaos reigns . . . He has made us adepts in government that we may administer government among savage and senile peoples . . . He has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world. This is the divine mission of America . . . The Philippines are ours forever. We will not repudiate our duty in the archipelago. We will not abandon our opportunity in the Orient. We will not renounce our part in the mission of our race, trustee, under God, of the civilization of the world."

Before the war President McKinley didn't know where the Philippines were, but eventually he also decided to keep them, claiming that God had told him it was America's duty to educate, uplift, modernize and "Christianize" (convert to Protestantism) the Filipinos. The result was a three-year conflict called the Philippine Insurrection or the Philippine-American War (1899-1902). It was a dirty guerrilla war in a jungle setting, much like the war America would fight in Vietnam seventy years later. The Americans suffered six thousand killed or wounded, while more than 200,000 Filipinos (mostly civilians) were killed. Finally the war ended after the Filipino leader, Emilio Aguinaldo, was captured in a raid. By then America had lost its desire to rule an empire; it kept Guam and Puerto Rico because their natives asked the Americans to stay, but Cuba was granted independence in 1902, and the Philippines was prepared for eventual independence, which finally came in 1946.(69)

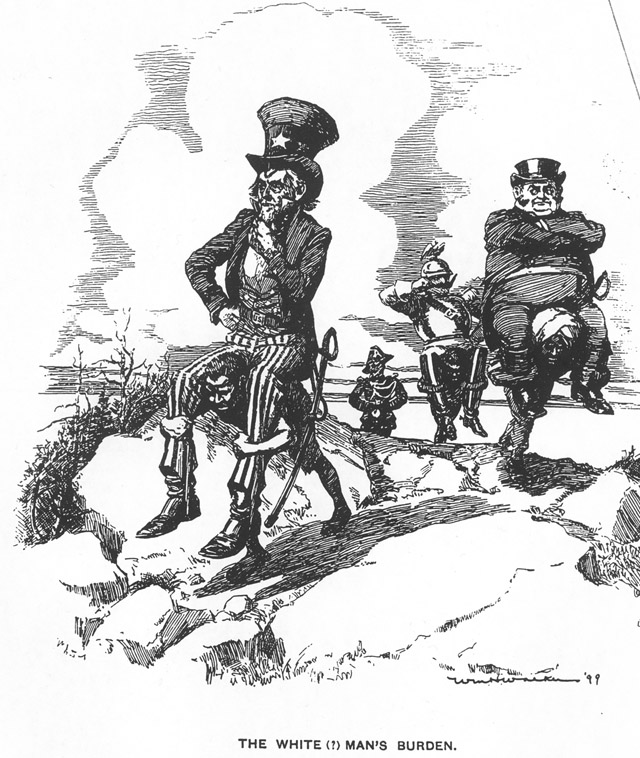

Uncle Sam learns the imperialist game by riding on a Filipino, while Britain's John Bull rides an Indian and Germany's Kaiser Bill rides an African.

Fears about the Spanish-American War's effect on the economy were groundless. Instead of draining resources, the retooling of factories to support the war effort, and a rise in commodity prices, combined to cause an economic boom.(70) Before the war, McKinley had been Mark Hanna's figurehead executive; now he was one of the best-loved presidents in American history. For the 1900 election, the Republican slogan was "Four more years of the full dinner pail," because the working man's dinner pail (what they called a lunch box in those days) was full. Even free silver wasn't an important issue anymore, because the Alaska gold rush had increased the money supply without the need to coin any other precious metal.

McKinley's first vice president had died in 1899, so the Republicans nominated Theodore "Teddy" Roosevelt as his running mate.(71) Roosevelt proved to be a dynamic candidate, traveling 21,209 miles (often with some former Rough Riders) and making 673 speeches. For example, in Colorado a Democratic heckler shouted at him, "What about the rotten beef in Cuba?" and Roosevelt shouted back, "I ate it, and you'll never get near enough to be hit by a bullet." Meanwhile, the Democrats nominated Bryan again, but the only new idea they could come up with was to argue that the war in the Philippines had bogged down. While Bryan acted like free silver was still relevant, McKinley and Roosevelt won the election easily.

Teddy and the Big Stick

On September 6, 1901, McKinley was shaking hands at a fair in Buffalo, NY, the Pan-American Exposition. One of the men who came to greet him had a handkerchief wrapped around his right hand like a bandage. The "bandage" concealed a revolver, and he fired two shots with it. Eight nights later McKinley died from a bullet wound in the stomach. The killer was an anarchist named Leon Czolgosz, who told police that for months he had been "on fire" with the desire to kill a great ruler.

All of America was shocked; Mark Hanna was probably the most upset of all, because McKinley's successor, Theodore Roosevelt, was a man he could not control. On McKinley's funeral train he exclaimed, "I told William McKinley it was a mistake to nominate that wild man at Philadelphia . . . Now look, that damned cowboy is President of the United States!"

The state of New York quickly sent Czolgosz to the electric chair, put quicklime and sulfuric acid in his coffin to dissolve the body, burned his clothes and letters, and even tore down the building where the assassination took place. Despite those measures, the nation had been changed forever; it was a rude awakening into the twentieth century.

To reassure everyone, Roosevelt said this to Secretary of State John Hay, before he was sworn in as president:

"I shall take the oath of office in obedience to your request, sir, and in doing so, it shall be my aim to continue absolutely unbroken the policies of President McKinley for the peace, prosperity, and honor of our beloved country."

He kept that promise for three or four months.

Theodore Roosevelt was one of the most interesting presidents in American history. Sickly as a child, he was nearsighted and almost died from asthma. Using a gymnasium his father installed in their home, he worked himself back into health, and showed tremendous energy as an adult. Only forty-two years old when he moved into the White House, Roosevelt was the youngest president the United States ever had--and the most athletic. The American people admired him because he did everything an American boy might want to do: he was a cowboy in the West, he fought in a war, he got to be president, and he killed lions in Africa. He always liked a good fight (he used the word "Bully!" as an adjective), but also became the first president to win the Nobel Peace Prize. His favorite vacations were hunting trips, but he also established more national parks and monuments than any other president. If you read any of the books that Roosevelt wrote, you will know that like most men with money and power in those days, he believed that white Anglo-Saxons were superior to everyone else, but as we saw in the previous footnote, he also supported equal treatment for all sexes and races. Whereas McKinley once hid his cigar from a photographer, saying, "We must not let the young men of this country see their president smoking!", Teddy loved to have his picture taken. And there were many good pictures taken of him; thanks to improvements in camera technology, he was the first president to be frequently photographed doing things besides posing for the camera. As one of his sons put it: "When father goes to a wedding, he wants to be the bride; when he goes to a funeral, he wants to be the corpse."

Another thing that made Roosevelt different from previous presidents was the way he used the full power of the executive branch of government, or as people called it in those days, "the Big Stick." This came from his favorite proverb: "Speak softly and carry a big stick, you will go far." There had been strong presidents in the past; e.g., Andrew Jackson used the Big Stick against the National Bank, and Abraham Lincoln used it to save the Union. Most of the rest, however, did not believe in an activist role for the chief executive. When Roosevelt took the Big Stick out of the closet, and began waving it around; the world ran for cover, because in the thirty-five years since it was last used, the United States had come of age, and was now a major power.

Whereas his predecessors believed in letting nature take its course, Roosevelt worked to improve the lives of ordinary people. But he was no radical or revolutionary. He called his program the "Square Deal," out of his belief in being fair to everyone. Instead of passing new laws, in the hope that they would work in any situation, he tried dealing with each problem that came his way on a case-by-case basis. In that sense, his presidency was like the battle of San Juan Hill, where Roosevelt led the charge. He preferred working this way because he always believed that whatever he did was right, and loved the publicity he got for doing the right thing. This caused a major controversy early in his administration, when he invited Booker T. Washington, the famous black educator, to a dinner at the White House. Southern politicians were furious, the press published inflammatory articles and vulgar cartoons, and somebody even hired an assassin in an attempt to kill Washington at Tuskegee; Roosevelt held his ground, but he did not invite Washington again.

Two of Roosevelt's earliest challenges came from the railroad and coal industries. By 1901, all railroads west of the Rockies were controlled by two men: James Hill (see footnote #40) owned the Great Northern and Northern Pacific, while Edward Harriman owned the Union Pacific and South Pacific. They had been rivals at first, but after a trade war in which Hill, Harriman and J. P. Morgan (an ally of Hill) tried to buy as much Northern Pacific stock as possible, the railroad kings put aside their differences and merged to form the Northern Securities Company, worth $400 million on paper. This was clearly a trust by definition, and Roosevelt launched a lawsuit against Northern Securities, becoming the first president to enforce the Sherman Antitrust Act. Morgan himself hurried to Washington to plead for some sort of compromise, but Roosevelt refused to back down; to him the United States would control the railroads, not the other way around. This gave him a reputation as a trust-buster and champion of the poor.

The coal challenge came from 150,000 anthracite miners in Pennsylvania, who went on strike in May of 1902 for higher pay, recognition of their union, the United Mine Workers, and a nine-hour workday. The mine owners refused to negotiate, and the strike dragged on for five months, with no one trying to reach a settlement. At first Roosevelt lamented that he did not have the power to bring the two sides together, then abruptly changed his mind and summoned the representatives of both the miners and owners to Washington. With winter approaching, the nation faced a severe coal shortage, so he told the representatives to do the patriotic thing and end the strike. The union president, John Mitchell, agreed to cooperate with the president on this, but the spokesman for the owners, George Baer, rebuked Roosevelt for "negotiating with the fomenters of anarchy" (meaning the union leaders), and said after the meeting, "We object to being called here to meet a criminal even by the president of the United States." This made Roosevelt furious, and he told J. P. Morgan that if the mine owners continued with that attitude, he would have the Army seize and operate the mines. Under pressure from both Roosevelt and Morgan, Baer backed down, though after negotiations the miners only got a ten percent pay raise. Presidents had acted before to break up strikes, but this was the first time a president had taken the side of the strikers. Most important of all, public opinion had been solidly behind Roosevelt throughout the whole episode.

It was in foreign policy where Roosevelt swung the Big Stick the most. In 1903 he got a new treaty defining the border between Canada and lower Alaska (the 1825 treaty was rendered obsolete by an influx of settlers, following the Klondike gold rush). When the nations of Europe threatened to intervene in the affairs of Venezuela and Santo Domingo, in order to collect the debts owed them, Roosevelt threatened to send US Navy ships to keep them out. As he explained to Congress in 1904, stability must be preserved, even if it required an "exercise of international police power." In the end he did not have to go into Venezuela, but he did occupy Santo Domingo in 1905, using the Navy to make sure the money collected there went to pay the debt and support the Dominican government. Two years later US forces withdrew, after American and Dominican leaders signed a 50-year treaty that gave control of customs administration to the United States. This intervention, done to prevent intervention from others, came to be known as the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, another key feature of US policy in Latin America.

These activities are easily forgotten, though, compared with the creation of the Panama Canal. During the Spanish-American War, the battleship Oregon was forced to make a 71-day detour around South America to get to Cuba; since then many wanted an easier way to sail between the Atlantic and Pacific. Originally the idea was to dig a canal through Nicaragua; since 1849 there had been an overland route across that country, for those who wanted to travel between the oceans without going all the way to Cape Horn. However, that idea was dropped, when it was suggested that a canal through the narrower Isthmus of Panama would be easier. A French company had already tried to dig there in the 1880s, only to give up after thousands of workers died from malaria and yellow fever. Congress voted in 1902 to dig in the same place, and bought the rights to the canal from the French for $40 million.

Panama was part of Colombia at that time, so Roosevelt stepped in and made this offer to the Colombian government: $10 million for the land the canal would cut through, which would become a permanent US territory, and $250,000 in rent each year. Colombia refused and Roosevelt got mad enough to prepare for war; in a letter to Secretary of State John Hay, he wrote, "We may have to give a lesson to those jack rabbits." Fortunately it didn't happen. In October 1903 a group of Panamanian nationalists met in a New York hotel room, and wrote a declaration of independence for Panama. A French agent supplied a $100,000 "liberation fund" and a hand-stitched flag, and sent a copy of the declaration to Washington. Three weeks later they started a revolt in Panama City, by bribing the local Colombian garrison to not resist them. Roosevelt immediately declared he would support the new government, and sent the navy there to keep other Colombians out. Then he gave Panama the money he had offered to Colombia. It took three years to kill the mosquitoes that spread disease in the jungles of the Canal Zone, and another seven years to dig the canal itself, but finally the first ship passed through the canal in 1914.(72) Because of the engineering, health and political hurdles that had been overcome, the Canal was seen as an outstanding achievement, but like the Roosevelt Corollary, it left some painful scars in US-Latin American relations, that would take most of the twentieth century to heal.

When the Russo-Japanese War began in 1904, Teddy was amazed that a little country like Japan could attack Russia and win. To his son Theodore Jr. he wrote, "Between ourselves--for you must not breathe it to anybody--I was thoroughly well pleased with the Japanese victory, for Japan is playing our game." But when Japan kept on winning every battle, he got bored and invited the two combatants to send representatives to the United States for peace talks. To everyone's amazement, they agreed, and ended the war by signing the Treaty of Portsmouth. For this he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906.

Teddy brings the Russian Tsar and the Japanese Emperor to the conference table.

Because Roosevelt had not been elected president, he wanted to win the 1904 election, to give his administration the same legitimacy that most previous presidents had. Of the four vice-presidents who had moved to the top when their bosses died (Tyler, Filmore, Johnson and Arthur), none of them had won a re-election bid, and Mark Hanna likewise tried to keep Roosevelt from getting nominated. Hanna's death before the Republican convention eliminated that obstacle, and in November Roosevelt had no trouble beating the Democratic candidate, who only carried thirteen states, all of them in the South.(73)

Roosevelt learned during his second term that when it came to advocating reform, he was no longer alone; since 1900 a wave of magazine articles and books, denouncing corruption in politics and business, had come out every year. Sometimes Roosevelt praised the writers, other times he called them "degraded beings," who would end up establishing socialism. A series of articles on Senate corruption in Cosmopolitan magazine, entitled "The Treason of the Senate," got Roosevelt mad enough to denounce the author, David Graham Phillips. In a 1906 speech, Roosevelt accused Phillips of courting sensationalism, because he was the type of person "who could look no way but downward with the muckrake in his hand ... (and) continued to rake himself the filth of the floor." Because of that speech, reform-minded writers have proudly called themselves "muckrakers" ever since.

The most successful muckraker was a failed revolutionary, a twenty-eight-year-old socialist named Upton Sinclair. In 1906 he published The Jungle, a horrifying novel about working in the Chicago stockyards. The story began with a Lithuanian immigrant, Jurgis Rudkus, wondering how he is going to pay for his expensive wedding. After coming to America he gets jobs under appalling conditions in the meat-packing industry, loses his family to tragedies that could have been prevented if he had more money, is badly treated in a world run by corrupt bosses, government inspectors, police and judges, and finds life utterly hopeless until he wanders into a socialist rally, where the leader shouts, "Organize! Organize! Organize! . . . Chicago will be ours. Chicago will be ours! CHICAGO WILL BE OURS!"

The Jungle was a best-seller, but the reaction wasn't what Sinclair had wanted. Before writing the novel, he promised it would be the Uncle Tom's Cabin of the labor movement, only to find that the readers (including Roosevelt) paid more attention to what it said about their meat supply than to Sinclair's denunciations of capitalism. When they read about workers falling into vats to become "Durham's Pure Leaf Lard," inspectors bribed to pass animals that were sick of tuberculosis and cholera, poisoned rats getting shoveled into meat grinders, and scraps on the floor getting picked up and turned into "potted ham," they demanded, and got, stricter laws in the meat-packing industry. Sinclair had wanted his readers to become socialists, and lamented, "I aimed at the public's heart and hit its stomach."

Big Taft and the Bull Moose

Roosevelt would have liked to remain in the White House for the rest of his life, but in 1904 he had promised to only serve for one more term, so for the 1908 election he stopped a "Draft Roosevelt" movement and told the Republican Party to nominate a personal friend, William Howard Taft. Taft had served as the first governor of the Philippines under McKinley, and had been Secretary of War for Roosevelt's second term. Teddy told everyone that Taft was the most likeable person he had ever met, and gave this advice to his candidate: "Hit them hard, old man! Let the audience see you smile always, because I feel that your nature shines out so transparently when you do smile--you big, generous, high-minded fellow." On the other side, the Democrats nominated William Jennings Bryan for the third time, but as the voice of a previous generation, Bryan did no better than he had before. All Taft had to do was smile a lot, and he won the election by more than a million votes.

However, Taft was also a very different person from Roosevelt. At 326 pounds, he was not the greatest president in American history, but he was the biggest. In the White House, one of the main events was the installation of a new, larger bathtub, because the old one was too small for him (The story about Taft getting stuck in the old bathtub isn't true. Sorry.). Instead of aggressively meeting every new challenge that came along, Taft was jolly and rather timid. Once in 1908, he was making a speech and somebody asked him, "What would you advise a man to do who is out of a job and whose family is starving because he can't get work?" Instead of making a campaign promise, Taft answered, "God knows. Such a man has my deepest sympathy." One promise he did make during the campaign was to lower the tariff, something the Western states still wanted, but conservative senators had their way on the tariff bill. Senator Nelson Aldritch of Rhode Island completely rewrote the bill to raise duties on six hundred items, so that after Taft signed it, the new tariff was higher, not lower. Taft also appointed a conservative Cabinet, and never criticized big business or businessmen in his speeches. When invited to make a speech at the National American Women's Suffrage Association, Taft announced that he didn't favor giving women the right to vote, because if they had it, power would flow into the hands of females "of the less desirable class"; the audience almost hissed him off the stage.(74)

The first two decades of twentieth century are sometimes called the "Progressive era," because after Roosevelt was gone, a number of liberal Republicans rose up to finish what he had started. Their leader was Senator Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin, who formed a faction in the GOP called the Progressive Republican Party. Other important Progressives included Senator William Borah of Idaho, Governor Hiram Johnson of California, Congressman George Norris of Nebraska, and Senator Jonathan Dolliver of Iowa. Dolliver explained that they were noisy because "President Taft is an amiable man, completely surrounded by men who know what they want." In 1910 they and the Democrats gained control of Congress, and they worked to end child labor, increase voting rights, give state governments more control over railroads and utilities, and gain various benefits for workers. By putting pressure on Taft, they got him to launch more lawsuits against the trusts than Roosevelt had (90 for Taft vs. 44 for Teddy). Other Progressive accomplishments were the creation of the Department of Labor, and the passage of two constitutional amendments in 1913: the Sixteenth (which authorized the creation of an income tax), and the Seventeenth (which called for direct election of senators by the people, instead of by state governments). Near the end of the decade, the Eighteenth (prohibition) and Nineteenth (women's suffrage) Amendments were also largely the work of Progressives.

The Progressives may have come along just in time, because socialist movements in America peaked during the Taft administration. Milwaukee sent Victor Berger, the first Socialist congressman, to Washington. Eugene Debs got six percent of the vote in the 1912 presidential election, his highest percentage ever. In addition to Debs' Socialist Party, there was a socialist group in the West, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, called "Wobblies" or "I Won't Works" by detractors). As is, the corrective actions of the Progressives damped the desire among American workers for revolution, so the United States did not experience the upheavals that would soon shake many European nations, especially Russia. Still preferring reform over revolution, Roosevelt blamed socialism's inroads on "the dull, purblind folly of the very rich."

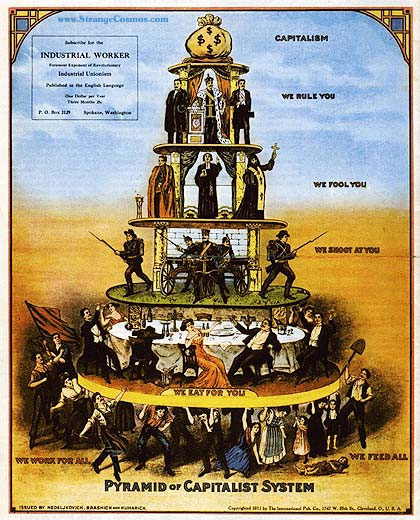

An anti-capitalist poster from the IWW.

Teddy couldn't comment on Taft's lack of leadership right away, because he spent 1909 and 1910 in Africa and Europe (see Chapter 7, footnote #33 of my African history). When he got the news, however, it was the end of their friendship. After he returned he called Taft "disloyal," and guilty of "the grossest and most astounding hypocrisy." Taft hadn't really wanted to be president(75), but he could not ignore this challenge, and he told The New York Times, "I have been a man of straw long enough. Even a rat in a corner will fight!" By 1912, Taft was seen as the leader of conservative Republicans, while Roosevelt and "Fighting Bob" LaFollette competed for the support of liberal Republicans; all three wanted to become the Republican candidate in the 1912 presidential election. Taft started gathering delegates for the Republican convention first, so he got the nomination, though Roosevelt won the most votes in the primary races. Accusing Taft of stealing the convention, Roosevelt and his followers walked out and held their own convention, where they nominated Roosevelt to run for a third term. At first they called themselves the Progressive Party, but soon Roosevelt answered a question about his health by saying, "I'm as fit as a bull moose," and the Progressives were known as the Bull Moose Party after that.(76)

Theodore Roosevelt, from a 1912 campaign photo.

In practice, there really wasn't much difference between the Republican, Bull Moose and Democratic platforms; all of them called for reforms. Therefore the election was mainly a clash between three personalities: Taft, Roosevelt, and the Democratic candidate, Thomas Woodrow Wilson. There was an exciting moment in October when Roosevelt left his hotel in Milwaukee and got shot by an anti-third term fanatic. Fortunately for Roosevelt, he had written a long speech on fifty sheets of paper, which were folded and placed in his shirt pocket. The assassin's bullet went through Roosevelt's coat, vest, glasses case and papers before cracking a rib; it probably would have killed him if not slowed by the papers. When he realized the wound wasn't as serious as it looked, the old Rough Rider insisted on giving his speech. At the rally he said, "There is a bullet in my body. But it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose!" Then he showed the papers containing the bullet hole, and opened his vest to reveal a bloody shirt to the shocked audience. Though he did cut his speech short, he stayed on the stage for ninety minutes before going to the hospital. The doctors decided that removing the bullet would be more dangerous than leaving it in, so Roosevelt carried it for the rest of life; that severely limited the exercise regimen Roosevelt had followed every day.

Despite Roosevelt's brave response to the assassination attempt, he did not win the election. Many folks who were inclined to support him were committed to one of the major party candidates. For example, a young relative of his, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, couldn't back him because he was already a prominent candidate. However, he did get revenge. In November he won six states, compared with two for Taft; this was the only time that a third party did better than one of the two major parties. Together they got more overall votes than Wilson, but because the Republicans were divided, Wilson got a plurality in most states, and he ended up with a huge electoral majority. Roosevelt's response was, "There is only one thing to do, and that is go back to the Republican Party." With that, the challenge from the Bull Moose came to an end.

After his defeat, Roosevelt tried to forget his humiliation by going on another adventure. This was in character for him; he had gone west to become a cowboy in 1884, following the death of his mother and his first wife on the same day; the 1909 African safari helped him get over the fact that he was not president anymore. For this excursion, he and his son Kermit joined a Brazilian explorer, Candido Mariano da Silva Rondon, to map a river in the Amazon jungle that Rondon had recently discovered, which he called the "River of Doubt." But whereas Roosevelt's African safari had been almost like a modern tourist's vacation, on the 1914 "River of Doubt expedition" they were in constant danger from rapids, a shortage of supplies, disease, fatigue, nasty creatures like anacondas and piranhas, and Indians with poisoned arrows. Malaria and an infected leg injury left Roosevelt weak and delirious; at one point he told Kermit to leave him to die, so that he would not hold up the expedition any longer. They made it out, though, and the river was subsequently renamed the Rio Teodoro, after the former president, but Roosevelt was never a well man again.(77)

Wilson the Reformer

Woodrow Wilson was an unlikely choice for president. First of all, he was a Southerner, born in Virginia and raised in Georgia, while all of the nine previous presidents had been "Yankees." Second, and more important, his background marked him as an intellectual, not a politician; he was the son, nephew and grandson of Presbyterian ministers, studied and taught at six universities, and eventually became the president of Princeton University. He only entered politics in 1910, two years before running for the presidency, when he was persuaded to run as the Democratic candidate for governor of New Jersey. Then, as now, New Jersey had one of the most corrupt political machines of any state; a group of business and political bosses nominated Wilson because they figured he would be a useful front man, to make them more respectable. Once elected, however, he introduced a utility control act, a workingmen's compensation act, a corrupt political practices act, and a direct primary act. This spectacular success at cleaning up the state government made him the natural choice of the reformers in the party, so he became their candidate on a national scale in 1912.

The first twenty months of his presidency showed similar energy, but whereas Wilson and Roosevelt both believed in using the Big Stick, and had similar goals on domestic issues, Wilson's high-minded approach contrasted with Roosevelt's heavy-handedness. Calling his program the "New Freedom," Wilson created the Federal Trade Commission and a stricter antitrust law, both for the purpose of stopping unfair trade practices. The Underwood tariff reduced the tariff on 958 imported items, because the newly created income tax would now be the government's main source of revenue. A child labor law, forbidding the employment of children under 14, was passed by Congress, but later was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. And by approving legislation to increase the wages and cut working hours of railroad employees, he prevented a railroad strike in 1916.

In the long run, Wilson's most important action may have been the Federal Reserve Act, enacted on December 23, 1913. We noted earlier that every decade or so, the economy had an unfortunate tendency to crash, with devastating results on the population; the most recent occurrence was a recession in 1907. After that recession, J. P. Morgan suggested bringing back the National Bank of the early 1800s, because he (correctly) predicted that when the next recession hit, he would not be around to bail out the country (see footnote #59). In 1912, Senator Aldrich proposed placing control of the nation's credit under a network of commercial bankers, to prevent such boom-and-bust cycles in the future. But many feared this "Money Trust" would also dominate the American people, so instead, the Federal Reserve Act created a network of government-controlled banks for the same purpose. By controlling the rates of interest permitted on loans, the Federal Reserve Board manages to keep economic growth from either rising or falling too quickly; its function has been compared with "taking away the punchbowl before the party gets out of hand." Consequently, the economic slumps experienced since 1913 have been milder and shorter than those of the nineteenth century, except for the Great Depression. However, the Constitution gave Congress the power to regulate commerce, and the Federal Reserve Act took away much of that power, so some observers feel that the Federal Reserve System is just as unconstitutional as the National Bank, and an unjustified expansion of the government.

The health of Wilson's first wife, Ellen, declined after they moved into the White House, and she died on August, 6, 1914. Thus, in the following March, the president's friends introduced him to Edith Bolling Galt, a widow who had successfully managed her husband's jewelry business. Because they were both Southerners, they got along from the start. She said no when Wilson first proposed to her, but he pursued the relationship, she said yes later on, and they were married in December 1915. Remember Edith; (Spoiler alert!) she will play an unexpected important role in Wilson's second term!

Wilson's program suffered an interruption in 1914, due to the ongoing Mexican revolution. President Francisco Madero had seized power in 1911, with the intention of introducing land reform, but two years later he was murdered by a reactionary general, Victoriano Huerta, and Huerta took his place. Since Madero's ideas were like Wilson's, Wilson denounced Huerta as a "desperate brute," and in April 1914, an unpleasant incident involving Mexican and American sailors (the "Tampico Affair") prompted Wilson to order the taking of Veracruz, Mexico's chief port. Four Americans and 126 Mexicans were killed in that battle, and it looked like a second Mexican-American war was beginning. All-out war was averted, however, when the three strongest South American nations (Argentina, Brazil and Chile) offered to mediate; Wilson agreed and pulled out the American forces, and Huerta resigned and went into exile.

That wasn't the end of the story, however, because three rival leaders, Venustiano Carranza, Francisco "Pancho" Villa, and Emiliano Zapata, now competed to rule all of Mexico. The revolution threatened to spill over into the United States when Washington recognized Carranza as the new president, and Pancho Villa responded in 1916 with a raid on the border town of Columbus, NM, killing eighteen US citizens. There were also three attacks on border towns in Texas, but no one knows to this day if Villa was behind them. Troops were rushed to the border, and Brigadier General John "Black Jack" Pershing led 10,000 of them into northern Mexico, on a mission to get Villa. They never caught him, though, and after chasing Villa for eleven months, Pershing withdrew in embarrassment. The conflict and anarchy in Mexico lasted until 1922--eventually 400 Americans were killed and $200 million worth of American property was destroyed--but this wasn't enough to make the United States intervene again, because Uncle Sam was preoccupied with other matters now.(78)

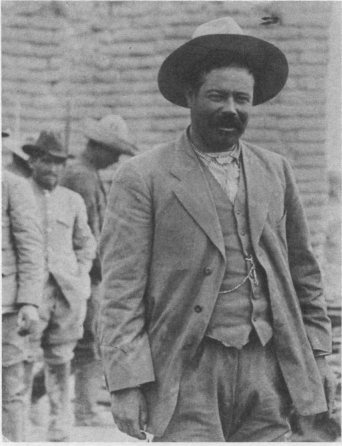

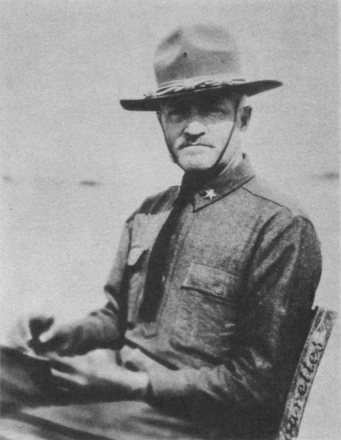

Two Contestants In the Mexican Revolution:

|

|

| Pancho Villa. | Black Jack Pershing. |

Meanwhile in the Caribbean, Haiti, like Santo Domingo and Venezuela, was in great financial distress. When the president of Haiti was killed by an angry mob in 1915, Wilson sent in US Marines, both to restore order and to keep the Europeans out. As with Santo Domingo, the US introduced a treaty that put Haiti's finances under American control, in an effort to straighten out the local economy. When the treaty expired in 1926, it was renewed for another ten years. Finally in 1934, Haiti's situation had improved to the point that the marines could leave, but as in other parts of Latin American, US intervention was bitterly resented. In 1917 the United States bought the Virgin Islands from Denmark for $25 million, and Puerto Ricans were made US citizens.

While history texts do not hesitate to tell us about Wilson's leadership, before and during World War I, and how he became a symbol of idealism afterwards, they usually gloss over the fact that he was also a white supremacist. When he was in charge of Princeton University, Wilson discouraged blacks from even applying for admission as students. As president, he tried to impose Southern-style segregation on the federal government, firing many black Republican government workers (however, he did hire a few black Democrats, including W. E. B. DuBois, a founder of the NAACP). When a black delegation protested these actions, Wilson told them that "Segregation is not a humiliation but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen." 1915 saw the release of Birth of a Nation, a feature-length film praising the Ku Klux Klan and attacking the Reconstruction period in Southern history. Birth of a Nation caused a sensation in theaters across the country, in part because it used a quote from History of the American People, a book Wilson had written years earlier:

"The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation . . . until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the Southern country."

Although Wilson played no part in the making of Birth of a Nation, he considered it an accurate account of the events; when he saw it in a private White House screening, he remarked, "It is like writing history with lightning; my only regret is that it is all so terribly true." The movie helped inspire the revival of the Ku Klux Klan in the same year. Whereas the original Klan had been simply anti-black in its sentiments, the new Klan expanded its hatred to include "Reds," immigrants, Catholics, and Jews as well.(79)

World War I

Part 1: Sitting It Out

Unfortunately for Woodrow Wilson, the war in Mexico wasn't the only war fought during his watch. The order that had kept the peace in Europe for nearly a century came crashing down in the summer of 1914, and World War I began. That conflict, also known as the "Great War," the "War to End All Wars," and the "Catastrophe of Modern Imperialism," would occupy most of Wilson's attention after that. This narrative will just cover what happened in the United States during World War I. For those who want to read about war-related events and battles, in the kind of detail that I've already devoted to the Civil War, visit these other papers on the site:

- Europe (the main theater of war)

- Russia (before the 1917 revolutions)

- The 1917 Russian revolutions and the Russian Civil War

- Middle East

- Africa

- The South Pacific

The Germans retaliated with a new wartime weapon, the submarine. In February 1915 the German government announced that all enemy ships intercepted near the British Isles would be sunk on sight. The Allies saw the submarine as a violation of traditional warfare, because a submarine could not surface and warn its target ship before firing; the guns on even a merchant ship could easily sink its thin-hulled attacker. Moreover, a submarine was much too small to take on any passengers or crew who abandoned ship, so most of the time submarines sank ships without warning, and there were no survivors.

From the American point of view, the worst incident came on May 7, 1915, when a German submarine torpedoed the Lusitania, the largest ocean liner currently in service. There were 1,924 passengers and crew onboard, and 1,198 died that day, including 128 Americans and 63 small children. The liner sank so fast that the submarine did not have to fire a second torpedo; presumably the explosion from the first torpedo ignited the 4,200 cases of rifle cartridges in the cargo hold. Newspapers called the Lusitania sinking "deliberate murder" and claimed the Germans were "savages drunk with blood," so Americans expected a declaration of war would come next. But Wilson was a pacifist at heart, and urged restraint: "There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force. There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight."

Wilson may not have wanted to go to war, but his actions ensured it would happen some day. He insisted that Americans had the right to sail in European waters, even on a ship belonging to one of the nations presently at war. His notes to Germany, demanding an apology and payment for damages, were so threatening that Secretary of State Bryan resigned, feeling these were impossible demands and that American neutrality could not last. Germany did back down, though, promising not to attack passenger ships without warning them first, if the United States could persuade Allied navies to do the same, and end the food blockade on Germany. Wilson rejected these conditions, but German attacks on American shipping ceased for the rest of 1915 and 1916.

For the 1916 presidential election, Wilson had a simple, direct slogan: "He kept us out of war." Though the sympathies of most Americans were with the Allies by now, it didn't mean they wanted to fight for them. One of the few who did was Roosevelt, who declared that if he had been president in 1914, he would have saved Belgium. Expecting that the US would enter the war eventually, Roosevelt prepared an army division for that day, and tried to get Wilson to put him in command of it, promising that if he and the division went to France, he would not come back. Historians have suggestested that Roosevelt was trying to bring back the Rough Riders, for one more cavalry charge like the one that won the battle of San Juan Hill. If that was his plan, it would have been a suicide mission; the French had tried a cavalry charge against the advancing German army in August 1914, only to be massacred by machine gun fire. One thing that was clear about World War I, was that with all the new military technology, it would not be like any war in the past. Maybe Roosevelt thought it would be better to fall in battle than suffer with the pains and sickness of old age; if so, his promise wasn't a joke. Wilson didn't get it, and refused to send the division.

Because the Republicans were recovering from their 1912 split, they looked for an uncontroversial candidate to run against Wilson. Indeed, Roosevelt had to talk some die-hard Progressives out of nominating him for another Bull Moose campaign. Instead, the party nominated a Supreme Court justice, Charles Evans Hughes, because in his six years on the Court, he had not said or done anything which could get him in trouble. Hughes was honest and dignified beyond a doubt, but perhaps too uncontroversial. When he did not attack Wilson very hard, Roosevelt privately called him "the bearded lady."

On a campaign stop in California, Hughes happened to stay in the same hotel as Governor Hiram Johnson, but failed to make a courtesy visit to Johnson's suite. Hughes may not have even known Johnson was there, but Johnson took it as a snub anyway, and did not campaign much for him. That may have decided the election, in view of how close the California vote was.

On election night Hughes swept most of the Northeast and Midwestern states and went to bed early, thinking he had won. After midnight a reporter tried calling, and the person answering the phone told him, "The president cannot be disturbed." To this the reporter said back, "Well, when he wakes up just tell him he isn't president." Wilson had made a comeback, carrying all of the South and West except Oregon and South Dakota. In California Wilson won by 3,800 votes, out of nearly a million cast, which gave him a slim 277-254 electoral majority.

Part 2: Over Here

After he was re-elected, Wilson kept the "He kept us out of war" pledge for only five more months. In fact, he and Congress authorized the building up of the Army and Navy in early 1916.(82) Now Wilson talked about ending the war with some kind of peace conference, an approach which came to be known as "peace without victory." But neither side was interested, and on February 1, 1917, the Germans announced they would resume unrestricted submarine warfare. They reasoned that if they sank enough British ships, they could starve Great Britain into submission, and even if this strategy brought the United States into the war, the Germans would be able to beat the Russians, British and French before there were enough American soldiers in Europe to stop them. To his admiralty, the kaiser wrote a memorandum that read, "Now, once and for all, an end to negotiations with America. If Wilson wants war, let him make it, and let him then have it." Wilson's response was to order the arming of American merchant ships; the Germans sank four of those ships in March.

Another reason why the Americans prepared for war was German diplomacy, which tried to take advantage of the current rift in US-Mexican relations. Three days before unrestricted submarine warfare resumed, the German foreign secretary sent a telegram to the German ambassador in Mexico, promising the states of Arizona, New Mexico and Texas to the Mexicans if they entered the war on Germany's side. The British intercepted the "Zimmermann Telegram," and passed it on to Washington.

On April 2, Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany, declaring that "The world must be made safe for democracy." Afterwards, he rode through the streets of Washington as crowds cheered, and the shocked president said, "My message today was a message of death for our young men. How strange it seems to applaud that." Congress gave him the war declaration on April 6; at the end of June the first American troops reached France. The Navy also mobilized, and it defeated the submarine menace so quickly that only one American troopship was lost to the "U-boats."

Once war had been declared, Americans put aside their pre-war arguments and dedicated themselves to winning it, showing a solidarity that would be impossible today. Rather than depend on an all-volunteer force, the Selective Service Act was passed to authorize military conscription. Nine million men registered with Selective Service; by the war's end, four million had been called up. Americans bought more than $18 billion in bonds to finance the war effort, and extraordinary efforts were made to conserve money and resources (one slogan said, "He serves best who saves most"). Patriotic songs like "Over There," and celebrities like Jack Dempsey and Douglas Fairbanks, did their part to rally the population behind the troops. To save on energy, clocks were moved forward.

The prosecution of trusts was curtailed for the war's duration, because big businesses were seen as quicker and more efficient, when it came to providing goods and services. The federal government placed six controlling boards over shipping, food, fuel, railroads, commerce and priorities, to get the most out of them; the leaders of those boards met with the president periodically, as a "wartime Cabinet." Of these men, the most important was Bernard Baruch, who used the War Industries Board to organize 28,000 factories into a "production trust" bigger than anything J. P. Morgan or John D. Rockefeller could have dreamed of. Because the nation's food supply was controlled by Herbert C. Hoover, a former mining consultant and humanitarian, women said they were "Hooverizing" when they did without wheat on Mondays, meat on Tuesdays, and sugar on Fridays, so that there would be enough for the soldiers.

For the Allies, the United States entered the war just in time; throughout Europe things were going bad for them. On the Western Front, Paris was no longer under the immediate threat of a German attack, due to the bloody stalemate in the trenches, but every attempt to push the Germans back had resulted in a frightful casualty list, and Allied morale was slipping, especially among the French. In the Balkans, Serbia and Romania, two smaller Allied nations, had been crushed. Italy was doing so badly against Austria-Hungary that troops had to be diverted from the Western Front to prevent an Italian collapse. The British were making progress in Africa and the Middle East (Baghdad and Jerusalem were captured by the end of 1917), but no victories in those places would be important without a matching victory on the Western Front. In the east, a revolution in March 1917 toppled the last Tsar of Russia; a second revolution in November put the Bolsheviks in charge, and one of the first things they did was pull Russia out of the war altogether. That allowed the Germans to concentrate their attention on the Western Front for the spring of 1918, with another march into France.

It took all of 1917 for the United States to send 200,000 troops to France, but as the number of ships and trained troops increased, the pace picked up; in 1918 it was possible for 50,000 troops to cross the Atlantic every month. By October 1918, 1,750,000 had landed on French soil. A reorganization of command had also taken place, with General Pershing in charge of the American soldiers, and France's Marshal Ferdinand Foch as supreme commander of the Allied forces.

The American "doughboys" first made a difference on May 28, 1918, when they captured and held the French town of Cantigny. The same week saw them stop a German attempt to cross the Marne River, at Chateau-Thierry. In July, the Germans called off their spring offensive, having lost 800,000 troops since March. Allied losses were nearly as great, but while the Germans had advanced as far as forty miles in some sectors, they had failed to capture any of their objectives: Ypres, Amiens, Compiègne, Arras and Rheims. Even more important, the Allied line--and Allied morale--had held.

Now the combined Franco-American-British force gained the initiative. Whereas there had only been 27,500 Americans available for Chateau-Thierry and the next battle in the neighborhood, Belleau Wood, 270,000 Americans took part in the first Allied counteroffensive, which pushed the depressed, exhausted Germans back twenty miles, in the Second Battle of the Marne (July 18-August 6). By contrast, the Americans were fresh and eager for a fight; at Belleau Wood, when a unit was pinned down by German machinegun fire, First Sergeant Dan Daly got his men to charge by shouting, "Come on, you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever?!" Next came the "Hundred Days Offensive," which lasted for the rest of the war (August 8-November 11). From Amiens, a combination of Australian, American, Canadian and British troops broke through the German line, crossed the Somme River, and began the liberation of Belgium. In mid-September, 550,000 Americans recovered the town of St. Mihiel and breached the main German defensive barrier, the Hindenburg Line; 16,000 Germans and 443 guns were captured there. Previously the British High Command had thought the Allies would not have the strength to try the Hindenburg Line until 1919, but now, with the help of tanks, more breaches soon followed. In October the British general Henry Rawlinson(83) had this to say about the Allied success: "Had the Boche [Germans] not shown marked signs of deterioration during the past month, I should never have contemplated attacking the Hindenburg line. Had it been defended by the Germans of two years ago, it would certainly have been impregnable." The biggest operation involving Americans, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, was also the last: 1.2 million US troops captured the railway hub of Sedan and drove the Germans all the way back to the Meuse River (September 26-November 11).

The Germans maintained an orderly retreat, but because they could not make a stand anywhere, they knew the war was lost. In October a moderate chancellor, Prince Max of Baden, was put in charge of the German government, and begged President Wilson for peace based on the Fourteen Points (see the next section). But Wilson wouldn't negotiate until Germany got rid of the kaiser, so on November 9, 1918, the kaiser abdicated and went to the Netherlands. Two days later a delegation of German civilians signed an armistice, in the railroad car that Marshal Foch used as his headquarters, and World War I was over.

The United States had been in the war for nineteen months, and spent $42 billion, ten times as much as the Civil War had cost. The cost in lives was high, too, at 116,516, but that was far less than Civil War losses, and only 2 percent of the total number of Allied casualties. In addition, more than half of the American dead were victims of disease (the worst influenza epidemic on record struck in 1918 and 1919), rather than victims of battle.

Part 3: Rejecting the Peace

One reason why Wilson had changed his mind about the war was the thought that a just peace would only be possible if the United States dictated the terms of it, and that wasn't going to happen if the country stayed out of the war completely. To a group of peace activists, led by Jane Addams, he explained that "as head of a nation participating in the war, the president of the United States would have a seat at the peace table, but . . . if he remained the representative of a neutral country, he could at best only 'call through a crack in the door.'" Accordingly, he was planning what those terms would be, almost as soon as war had been declared. In January 1918, he boiled his ideas down into fourteen easy-to-remember principles, which were called the Fourteen Points:

- Open covenants of peace, with no more secret diplomacy.

- Freedom of navigation on the seas.

- Free trade between all countries signing the peace treaty.

- Guarantees to reduce national armaments.

- Impartial settlement of all colonial claims.

- Evacuation of all Russian territory.

- Restoration of Belgium.

- Return of Alsace-Lorraine to France.

- Adjust Italy's frontiers to follow the borders between ethnic groups.

- Autonomous development for the peoples of Austria-Hungary.

- Evacuation of Romania, Serbia and Montenegro, with free access to the sea for Serbia.

- Autonomy for non-Turkish ethnic groups in the Ottoman Empire.

- An independent Polish state with a seacoast.

- A League of Nations to maintain world peace.

In late 1918, even while the war was going on, the Allies also intervened in the former Russian Empire, now called the Soviet Union. The Bolshevik leader who had seized power there, Nikolai Lenin, was like Woodrow Wilson in that he had a vision to create a new world order. But when the Bolsheviks got out of the war without Allied approval, executed the last Tsar, and declared their intention to cause a worldwide communist revolution, the Allies decided they didn't want any part of Lenin's dream. Soon there were also communist revolutions in Estonia, Finland, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Hungary. All of them failed eventually, but they got Westerners nervous; could Red uprisings happen in France, the United Kingdom, and the United States, too? The second half of 1918 saw British, French, American and Japanese troops land at the ports of Murmansk, Archangel and Vladivostok. Their original mission was to recover the arms and other supplies that had been sent to Russia previously, before they fell into German or Bolshevik hands, but after that the mission changed, and soon the Allies were actively helping the anti-Bolshevik "White Armies." However, it was only a halfhearted effort; most of the troops wanted to go home, after the main war in Europe ended, and only the Japanese seemed to know what they were fighting for. By 1920 most of the White Army factions had been defeated, so the Allies announced they were getting out; the last Americans left in 1922. This strange epilogue to World War I got Soviet-Western relations off to a bad start, leading to the Cold War later on.

After the war Wilson showed his greatest shortcoming; he was so self-righteous that he was inflexible when it came to diplomacy. Feeling that his job was only half over, Wilson decided he must attend the peace conference in Europe. In October 1918 he asked the voters to back him up by electing Democrats in that year's congressional elections, a move that backfired; the people instead elected Republican majorities to both houses. Wilson went to Europe anyway, becoming the second president to travel outside the United States while in office.(84) He was encouraged when crowds greeted him enthusiastically in every European city, prompting him to predict, "The fortunes of mankind are now in the hands of the plain people of the world."

The conference was held first in Paris, and the resulting treaty was signed at Versailles, the former palace of French kings. Wilson soon found out that his partners, especially French Premier Georges Clemenceau, were more interested in revenge than in "peace without victory."(85) As negotiations dragged on, one member of the American delegation, General Tasker Bliss, grimly commented, "Why deceive ourselves? We are making no peace here." The final document included the Fourteen Points, but Germany was also forced to pay reparations, give up its overseas colonies, and admit guilt in starting the war. And even there Wilson had to compromise on most of the Points to make sure the one he wanted the most--the League of Nations--remained intact.

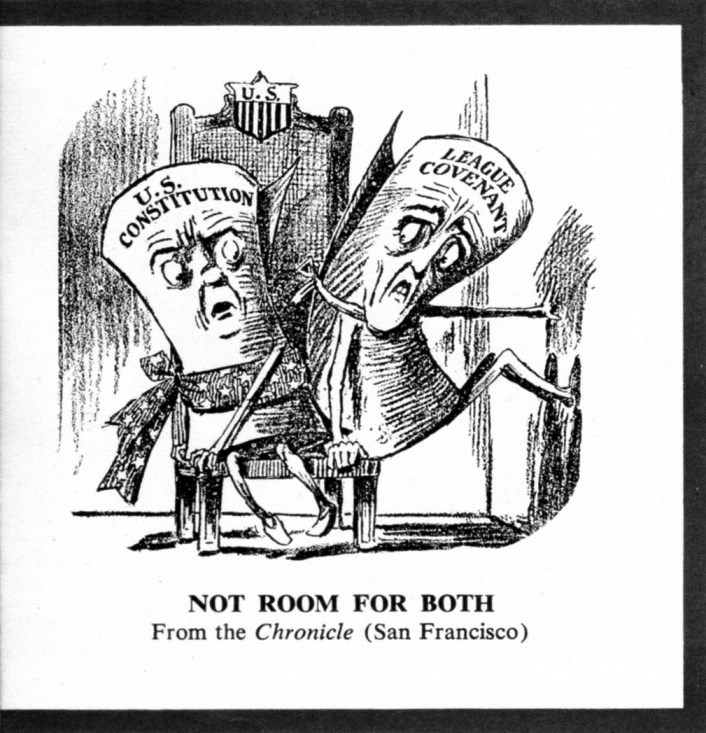

Wilson hated how the treaty turned out, but because he felt the League of Nations could fix problems like this, he went home to sell the treaty. He had been away for six months, and found to his horror that most of Congress and the American people were against what he had been doing. There were many sources for this opposition. First of all, the economy was suffering from a postwar slump.(86) Many farmers were bankrupt or in debt, after a sudden drop in the price of farmland. Four million soldiers had gone back to civilian life with little money and few benefits; as was the case after the Civil War, a lot of new jobs were needed. Irish-Americans were upset because the treaty said nothing about Ireland becoming independent; Italian-Americans were upset because Italy had fought hard but gained little in the treaty; German-Americans were upset because the treaty was too hard on Germany. Isolationists who had opposed the war had no interest in continuing US involvement with the world after the war ended. Albert J. Beveridge, who had been a leading imperialist twenty years earlier, didn't want to see any future international agreements get in the way of US interests; he said at this point, "America first! Not only America first, but America only!" Some opponents even saw the League Covenant as a replacement for the US Constitution (see the cartoon below).

However, Wilson's toughest opponents were the Republicans in the Senate, who were offended because Wilson never consulted them during the peace process. They were led by another former imperialist, Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts. Lodge had supported the idea of the League of Nations at first, but when he saw the treaty, he proposed fourteen amendments and reservations that would make it more acceptable to Americans. The most important change required that if the League called on its members to contribute troops for the purpose of stopping a future aggressor, the United States would have to get the approval of Congress before it took part in such an action. Wilson wouldn't have anything to do with this, calling his foes "a little group of willful men," and Lodge became the League's worst enemy.

Wilson thought that if he could persuade enough voters to support him, it might change the minds of the senators, so in September 1919 he took his case to the people. By now he believed that world peace could only be maintained by wholehearted American support for the League, and in a whirlwind tour of the country he warned that if the League were rejected or crippled, another world war would come in a generation, and the weapons used in it would make the weapons of World War I look like toys. After delivering his fortieth speech in Pueblo, CO, he collapsed, the victim of a stroke that paralyzed him on one side. For several weeks he could not sign documents, and most of the decisions he was expected to make were delegated to his vice-president, Thomas R. Marshall. Rumors flew around that the president was dying, or had gone insane, and in an extraordinary move, the Senate sent a committee to the White House to see for themselves if the president was mentally competent.(87) For the visit from the senators, the White House staff put Wilson in a darkened room, so the senators could not get a good look at him, and coached him on what to say; Wilson said his lines correctly, and this convinced the committee that the president was all right. During the last year and a half of Wilson's presidency, his wife Edith played the part of an unofficial acting president, by carrying out many of the presidential duties, so if you're wondering when the United States will get its first female president, it has probably already happened. Keep in mind that Edith was not seeking power; the job of acting president came to her unexpectedly, and while the Nineteenth Amendment was passed around this time, she had never supported women's suffrage. All this time, Wilson was an invalid; never before, and never again, did a president finish his term in such bad shape.

Wilson did manage to issue one more order to Senate Democrats. He called on them to reject every Republican attempt to water down the League; it must be the League of Nations on his terms, or nothing. He soon found that his illness had gained him little sympathy. In November the Senate voted to reject the treaty, and the League with it. Enough pro-League voters petitioned the Senate to make it reconsider its action in early 1920, but because the president remained intransigent, the vote was 49-35, seven votes short of the two-thirds majority needed to pass the treaty. The League of Nations would have to manage the world without US help.

This is the end of Part IV. Click here to go to Part V.

FOOTNOTES

66. There was a scare in 1889 when warships from all three nations entered a Samoan harbor; war was averted when a sudden hurricane swept away all but one of the ships.

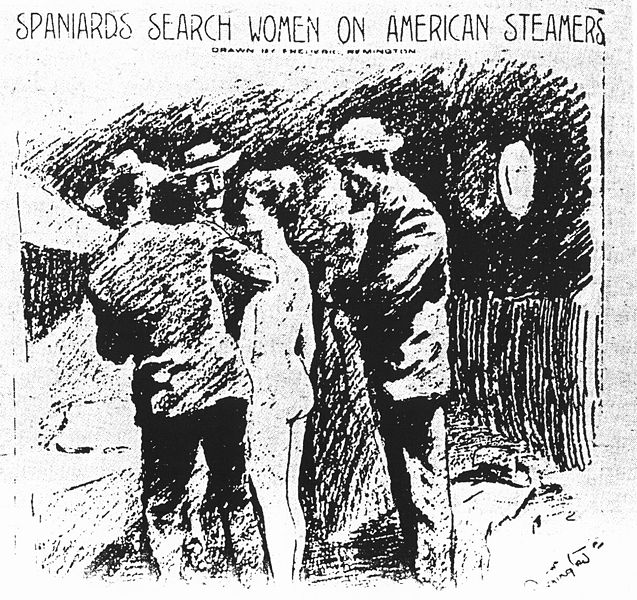

67. William Randolph Hearst, one of America's most powerful newspaper publishers, hired Frederic Remington, an artist famous for his paintings of the American West, to do some sketches of the Cuban rebellion. When Remington arrived in Cuba, however, hostilities between the Cubans and the Spaniards were winding down. The homesick Remington sent this telegram: "Everything is quiet. There is no trouble here. There will be no war. I wish to return." Hearst was so confident of what his newspapers could do that he wired back: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war."

One of Remington's contributions was this fake atrocity picture, showing Spanish soldiers strip-searching American women on a ship near Cuba. From Wikimedia Commons.

68. President McKinley commissioned six ex-Confederate generals to serve as generals in the Spanish-American War. One of them was Joseph Wheeler, who had been a cavalry commander in the Army of Tennessee. Sailing with the Rough Riders, he fell ill during the campaign and had to be carried in an ambulance to Santiago. When he saw the battle of San Juan Hill going badly, "Fighting Joe" bravely left the ambulance, asked for help in mounting a horse, and led a cavalry charge. The charge worked, and Wheeler had a flashback to his youth, shouting to his men, "The Yankees are running; they are leaving their guns!" Then he remembered that technically he was a "Yankee" now, and exclaimed, "Oh, damn it, I didn't mean the Yankees, I meant the Spaniards!"

69. Read Chapter 3 of my Southeast Asian history for more about the Philippines. And here are some rare movies shot during the Philippine Insurrection.

70. To help pay for the Spanish-American War, Congress put a one-cent tax on every telephone call. By 1990 the tax had grown to three percent of a typical monthly long-distance service bill. It wasn't until 2006 that enough of an outcry was raised to make the Internal Revenue Service and the Department of the Treasury stop collecting the tax. Because the war began and ended in 1898, does anybody know where the money went during those other 107 years?

71. During the 1898 gubernatorial election, Roosevelt's patron was the most powerful Republican in New York, Senator Thomas Platt. But after Roosevelt became governor, he and Platt stopped getting along. Roosevelt believed the government should give equal treatment to everyone, regardless of their sex or ethnic background, and a lot of politicians in those days weren't ready to accept that idea. Platt was even more offended by how Roosevelt enthusiastically cleaned out corruption in every department he got to lead, and now that department was the whole New York state government; he called Roosevelt a "bull in a china shop." So when Platt suggested that Roosevelt become McKinley's second vice president, he wasn't rewarding Roosevelt for his Rough Rider adventure, or even for his loyalty to the Republican Party; he was "kicking him upstairs," so to speak. The reasoning was that making Roosevelt vice president would keep his admirers happy, and while he was vice president, he would not get anything done. Of course there was a chance that a vice president could become president later, but more often they faded into obscurity (see Chapter 3, footnote #14). Indeed, after getting the job, Roosevelt said he would like to see the vice presidency abolished. Fortunately for him, and unfortunately for Platt, Roosevelt only stayed vice president for six months. Oops!

By the way, Roosevelt disliked his nickname, but he couldn't stop most Americans from calling him Teddy.

72. By the time the Panama Canal opened, William Jennings Bryan was Secretary of State. In one of the most embarrassing goofs of history, he sent a letter to Switzerland, inviting the Swiss Navy to attend the Canal's opening ceremonies.

73. Roosevelt's 1904 opponent was a dark horse Democrat, Alton B. Parker, who's only worth remembering because of my favorite bit of political trivia; this was the last time that the Republicans nominated a liberal for the presidential race, and the Democrats nominated a conservative. I don't think the Democrats seriously expected to win, because Parker's running mate was an eighty-one-year-old millionaire.

74. If only Taft could have seen who took over the feminist movement in the late twentieth century!

75. Taft was happy to leave the White House, and after he did, he finally got what he really wanted--to become the most important judge in the land. In 1921 President Harding appointed Taft Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and he stayed in that position until one month before his death in 1930.

76. "I want to be a Bull Moose,

And with the Bull Moose stand,

With antlers on my forehead,

And a Big Stick in my hand."--sign carried by the California delegation at the 1912 Progressive convention

77. Roosevelt died in his sleep on January 6, 1919. In 1918 he considered running for president again, but his death put an end to whatever plans he had for that. When the current vice president, Thomas R. Marshall, heard that Roosevelt was gone, he said, "Death had to take Roosevelt sleeping, for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight." For someone as tough as Roosevelt, you can't give a better eulogy than that.

78. In the first years after the motion picture camera was invented, movie-making was controlled by a trust, like so many other industries at the beginning of the twentieth century. In this case, the trust was the Motion Picture Patents Company, which was founded in 1908 and based in New York. The trust had such a firm grip on every aspect of the business, that no one could legally make a movie without its permission. When some filmmakers tried to escape the trust's grip by working outside of New York, they looked for locations close to the southern border of the US, where winters were shorter and cheap labor was easy to find. They tried setting up studios in Florida and Cuba, but those places were too hot and prone to disease. In the end southern California worked best; besides a drier climate and the reasons mentioned above, it was close enough to Mexico for film crews to make a run for the border, if they got in trouble. Hence, the Hollywood film industry was born by the time Wilson became president.

Speaking of the border, click here to read the surprising story of how Hollywood influenced the Mexican Revolution.

79. Ku Klutz Klan might have been a more appropriate name. The organization's founder, William Joseph Simmons, wrote a rules manual, which he called The Book of the Invisible Empire; the Kloran for short. In June 1916 he issued this "Imperial Decree" about it: "The Kloran is the book of the Invisible Empire and is therefore a sacred book with our citizens, and its contents must be rigidly safeguarded. The book or any part of it must not be kept or carried where any person of the 'alien' world may chance to become acquainted with its sacred contents as such. In warning: A penalty sufficient will speedily be enforced for disregarding the decree in the profanation of the Kloran." By the end of the year, however, Simmons decided that a book as important as the Kloran needed the protection of federal law, so he applied for a copyright. The requirements for a copyright were a one dollar fee and two copies of the manuscript, sent to the Register of Copyrights. Simmons complied with the dollar and the copies like any other author would, so the supposedly forbidden Kloran became available in the Library of Congress, and is on the Internet today.