| The Xenophile Historian |

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 5: Pax Americana, Part III

1933 to 2008

This paper is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| First, an Explanation of the Title | |

| The New Deal | |

| New Deal II | |

| Getting Out of the Depression--The Hard Way | |

| The Gathering Storm | |

| Pearl Harbor | |

| World War II |

Part II

| The Country Boy From Missouri | |

| Enter the Cold War | |

| China, Korea, and the Pumpkin Papers | |

| "I Like Ike" | |

| Life in the 1950s |

Part III

| The "New Frontier" | |

| Who Really Killed JFK? | |

| The "Great Society" | |

| Nixon Returns | |

| "All the President's Men" | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part IV

| Years of "Malaise" | |

| The Reagan Renaissance | |

| George Bush the Elder | |

| Clintonism |

Part V

| The Clinton Scandals | |

| Islamism on the Move | |

| The Battle of the Ballots | |

| George Bush the Younger | |

| Angry Democrats, Drifting Republicans | |

| Modern American Demographics | |

The "New Frontier"

Because of the 22nd Amendment and his advanced age (Eisenhower was the first president to turn seventy years old while in office), Eisenhower did not run in the 1960 presidential election. To nobody's surprise, the Republicans nominated Vice President Nixon as Ike's successor. Eight Democrats threw their hats in the ring, but most of them only ran as "favorite sons," concentrating their campaigns in their home states. The only three who were seen as candidates for the whole nation were Adlai Stevenson, John F. Kennedy, and Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota. Stevenson entered the race too late to win, so it became a contest between Kennedy and Humphrey.

Being just forty-two years old as the 1960 campaign began, Kennedy was a young and attractive candidate. He gave the impression that he came from an old aristocratic family, though the family fortune had been made by his father (see footnote #3). Most of his early years were spent at family homes in the Bronx, Hyannisport, MA and Palm Beach, FL, plus two and a half years at Choate, a private boarding school for boys in Connecticut. Enrolling at Princeton, he only stayed in that college for six weeks because of a lengthy intestinal illness (the doctors thought it was leukemia!), and the following year he went to Harvard, where he managed to stay long enough to complete his higher education. He had a back injury that troubled him all his life, but that didn't keep him from joining the US Navy in September 1941. Two years later, he was commanding a patrol boat, PT-109, which was rammed in the night by a Japanese destroyer, near the Solomon Islands. Although injured himself, Kennedy managed to tow a badly-burned man, with the help of a life jacket, to the nearest island, and then to another island, where they were eventually rescued. For this action, Kennedy received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal; by the end of the war, he was also decorated with a Purple Heart, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal and the World War II Victory Medal. When later asked how he had become a war hero, Kennedy joked to the reporter: "It was involuntary. They sank my boat."

After the war, Kennedy considered going into journalism, but his father had other plans; Papa wanted at least one of his sons to pursue a career in politics, and the eldest, Joseph Kennedy Jr., had been killed in World War II. Now he would promote John F. Kennedy at every opportunity, saying, "We're going to sell Jack like soap flakes." In 1946 a Massachusetts congressman gave up his seat to become mayor of Boston, and John F. Kennedy successfully ran for that congressional seat. In 1952 he ran for the Senate, beating the incumbent Republican, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. In 1955, while recovering from a back operation, he wrote (with the help of his future speech writer, Theodore Sorenson) Profiles In Courage, an inspiring biography of eight heroic senators. This work got far more attention than most books written by politicians in office, and won a Pulitzer prize.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

As a presidential candidate, Kennedy had two serious liabilities. First, because of his age, many were likely to see him as too inexperienced for the presidency. Second, he was a Roman Catholic. Being a Catholic had ruined Al Smith's chances of becoming president in 1928, and anti-Catholic prejudice was still strong, so to get elected, Kennedy had to prove he was not the pope's agent. His victory against Humphrey in the Wisconsin primary was not impressive, because several heavily Catholic neighborhoods came out for him, but a surprise win in West Virginia, one of the "Bible Belt" states, was a different matter. Kennedy's victory there convinced even strongly Protestant communities that he should be taken seriously. Humphrey subsequently dropped out of the race, leaving Kennedy as the first choice at the Democratic convention. For his acceptance speech, Kennedy talked about a "New Frontier," because he predicted America would be facing many serious challenges very soon; that gave a popular name to his administration. To balance the ticket, Kennedy asked one of the "favorite sons," Texas Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson ("LBJ"), to be his running mate.

Despite this success, Kennedy still faced an uphill battle against Nixon, who enjoyed a slight lead in the polls. And while the Republicans did not make Kennedy's religion an issue, he still had to convince the nation's Protestant majority that it would not be a factor; religious prejudice probably cost him a million votes in Illinois alone. In a speech before the Greater Houston Ministerial Association, Kennedy dealt with this by saying, "I am not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for president who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters--and the Church does not speak for me."

The 1960 campaign also saw the first debates on television between presidential candidates. For the first debate, Kennedy showed himself as a decisive leader, with charm and vigor that even Republicans could admire. By contrast, Nixon was tired from campaigning on the same day, had an injured leg, looked tense, and because he chose not to use makeup, had an obvious case of five o'clock shadow. Although Nixon did better in the other debates, a lot of people believe the first encounter between the candidates was the one that mattered. This would be an important early lesson in how TV images can be a powerful influence on the public.

On Election Day, Kennedy barely pulled it off, through several minor factors that worked in his favor.(44) Besides the previously mentioned ones (his war record, Profiles In Courage, his charm, and a timely recession), his wife, Jacqueline Lee Bouvier, better known as Jackie Kennedy, would be one of the classiest ladies to ever grace Washington. The election was extremely close; out of nearly 69 million votes casts, Kennedy led by only 116,000. He did better in the electoral vote, though, where he had a 303-219 lead over Nixon. Allegations arose that the Democrats had stolen enough votes in Illinois and Texas to give those states, and the election, to Kennedy. The charges were serious enough that many Republicans, including Eisenhower, thought Nixon should contest the results. Nixon refused to do it, feeling the country's political system could not survive such a battle (Perhaps even he didn't think he could be a better president?), and JFK's vote margin of less than 0.2% stood.

Wedding picture of John and Jackie Kennedy.

Eisenhower was the last president born in the nineteenth century, so a new generation took over with Kennedy. He said as much in his oft-quoted inaugural address:

"We observe today not a victory of party but a celebration of freedom--symbolizing an end as well as a beginning--signifying renewal as well as change. For I have sworn before you and Almighty God the same solemn oath our forebears prescribed nearly a century and three-quarters ago.

The world is very different now. For man holds in his hands the power to abolish all forms of human poverty and all forms of human life. And yet the same revolutionary beliefs for which our forebears fought are still at issue around the globe--the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state but from the hand of God.

We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution. Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans -- born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and hitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage -- and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed. . . .

Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, hear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty. . . .

And so my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you--ask what you can do for your country.

My fellow citizens of the world: ask not what America will do for you but what together we can do for the freedom of mankind."

If there was a place where the term "New Frontier" applied, it was space. On April 12, 1961, the Soviets put the first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, for a one-orbit flight. This prompted Kennedy to set a goal for the space race: "I believe this nation should commit itself, to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth." The United States got two space heroes later in the same year, but the rockets flown by Alan Shepard and Virgil Grissom were only capable of suborbital flights; they went up and down, and that was it. It was not until February 1962 that an American astronaut, John Glenn, successfully orbited the earth. The Russians went on to send the first woman into space, launch the first multi-man mission, and achieve the first space walk. By then, however, the United States had begun launching space probes to other planets, something the Russians hadn't yet succeeded in doing, and the highly successful Gemini program showed that Western science and technology could still catch up with and surpass whatever communist scientists invented.

Back on earth, the biggest challenge was that in recent years, the political scene had gotten more complicated; the world was no longer simply divided into communist and anticommunist factions. Since the end of World War II, Great Britain, France, Italy, the Netherlands and Belgium had followed the American example toward the Philippines, and granted independence to their colonies. Most of these new nations were in Africa, but some very important ones (e.g., India) appeared in Asia as well; before long new nations would be popping up in the Caribbean, too. Unfortunately for the west, most of these countries didn't want to take the same side as their former masters, preferring to be neutral in the Cold War; some of the new heads of state, like the Congo's Patrice Lumumba, even saw the Communists as the lesser of two evils. To win the friendship of these nations, Kennedy established the Peace Corps, a humanitarian program with three purposes: provide technical assistance to developing nations, help non-Americans understand US culture, and help Americans understand foreign cultures. The first director of the Peace Corps was R. Sargent Shriver, the president's brother-in-law. In the early 1960s, most liberals believed that the United States should use its power and resources to make the world a better place, and the Peace Corps is the best example of this attitude transformed into action.

Unfortunately, not every foreigner could be won over with the Peace Corps. One who wasn't was Fidel Castro, who by now had become a royal pain for the United States. On April 17, 1961, after a couple of days making diversionary attacks, a band of 1,400 armed Cuban exiles landed on a Cuban beach, the Bay of Pigs. They were trained by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and their goal was to overthrow the Castro regime.(45) Unfortunately for them, their invasion was a poorly kept secret (the beach turned out to be a favorite fishing spot of Castro's), and the US failed to provide the air cover they needed. The result was that the exiles got nowhere; all of them were quickly killed or captured. Most of the planning for the Bay of Pigs invasion had been done before Kennedy took office, but he took full responsibility for what happened. The American public forgave him, chalking it up to the new president's lack of experience.

This happened because Americans, and much of the world's population, simply loved the first family. After the Bay of Pigs, for example, Kennedy's approval rating climbed to an astounding 82 percent. This caused him to exclaim, "My God, it's as bad as Eisenhower. The worse I do, the more popular I get." The media couldn't get enough stories of the president, the first lady, and their two children, Caroline and John F. Kennedy Jr. ("John-John"). For instance, they reported on Caroline's pet pony, Macaroni (a gift from Vice President Johnson), and how Caroline offered India's prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, a rose to wear in his buttonhole. In 1962 Jackie guided TV cameras on the first televised tour of the White House, and The First Family, Vol. 1, a comedy album where Vaughn Meader impersonated the president, became the most popular record made up to that time, selling 7.5 million copies. In 1999, the Gallup organization did a poll on the most admired people of the twentieth century, and JFK came in third place, after Mother Teresa and Martin Luther King, Jr. The Kennedy family legacy allowed the president's two younger brothers to pursue political careers for the rest of their lives; Robert F. ("Bobby") Kennedy was first Attorney General, then a senator from New York, while Edward M. ("Teddy") Kennedy got himself elected senator from Massachusetts in 1962, and held that seat for the next forty-seven years.

However, there was another aspect to the Kennedy legacy that wouldn't be reported until more than a decade after his death--the president's sexual escapades. From his teenage years onward, JFK showed a very active interest in pretty women, which wasn't satisfied after he married Jackie. He also had the charisma to attract them. During the 1952 Senate campaign, his Republican opponents found a snapshot of JFK reclining on a Florida beach, next to a nude woman with a spectacular figure. His worried aides brought the photo to Kennedy, and he studied it for a moment before smiling and saying, "Yes, I remember her. She was great." Women regularly sent him love notes while he was a senator, to the point that when he was elected president, one of his aides privately predicted, "This administration is going to do for sex what the last one did for golf." While serving the country, Kennedy not only had his wife but also a steady supply of interns, prostitutes, airline stewardesses, beauty queens and actresses to serve him. The actresses included Jayne Mansfield and Marilyn Monroe, but it is not clear how close a relationship they had with the president; of course some of the stories are just gossip. Still the idea that JFK was an American Casanova only seems to have added to his larger-than-life reputation.(46)

Kennedy met with Nikita Khrushchev in the summer of 1961, and for Khrushchev, the meeting confirmed what he guessed after the Bay of Pigs fiasco--that Kennedy was a pliable novice. Not long after that, the Soviets tightened their grip on East Germany by building a wall around West Berlin, which until now had been the easiest place for East Germans to escape to the West. Although Kennedy let it be known he was aware of the situation, by going to West Berlin and making his "I am a Berliner" speech, the wall stayed up; in fact the Soviets started adding nasty features to the wall like barbed wire, broken glass, machine gun towers and attack dogs, to trap/kill those who tried to go over it. This stalemate over Berlin lasted for the rest of the Cold War era.

For the US, the situation was even less acceptable in the former French colonies of Indochina. Not only had a second war erupted in Vietnam, but a three-sided civil war had begun in Laos in 1959, pitting Communists against "rightists" and a neutral faction around the Laotian royal family. Whereas Eisenhower had simply thrown money to the Laotian and South Vietnamese governments, Kennedy saw that wasn't helping anything, so he sent 400 Americans soldiers to South Vietnam in early 1961--only as advisors, of course. That didn't stop the Communist guerrillas, either, so Kennedy raised the stakes by sending more troops, steadily increasing the number over the course of 1962 and 1963. Unfortunately, the South Vietnamese government proved it was too corrupt to defend its own people, and its president, Ngo Dinh Diem, became as unpopular as Cuba's Batista had been. Diem's assassination at the hands of the South Vietnamese army was not engineered by Washington, but it had Washington's approval. Alas, that left South Vietnam in a state of anarchy, and with the size of the American force up to 15,000, mission creep set in; many Americans now believed they would have to fight the war for South Vietnam, or lose it altogether.

Meanwhile in the western hemisphere, U-2 spy planes flying over Cuba made a chilling discovery: the Soviets had shipped medium-range missiles to Cuba, which were capable of hitting targets in the United States, Central America, or the nearest countries of South America. Kennedy was shown the photos on October 16, 1962, and six days later he announced what he would do: impose a total blockade on ships approaching Cuba. An invasion of the island or air strikes on the missiles was likely to trigger the nuclear exchange he didn't want (Castro urged the Soviets to use the missiles if any attack on Cuba was made), but just in case it came to that, he rushed soldiers and military equipment to Florida. This was the only time the new Interstate highway system was used for the defensive purpose Eisenhower had in mind.

Never before--and never again--did the USA and USSR come so close to the brink of nuclear war. The Soviets announced they would not allow their ships to be stopped and searched, but Kennedy stood firm, though he made sure that the only ship searched by the US Navy was a Cuban ship that wasn't likely to carry any missiles. Finally, after a six-day standoff, Khrushchev backed down; on October 28 he said the missiles would be removed if the United States ended the blockade and promised not to invade Cuba.(47) Kennedy came out as the winner in the "Cuban Missile Crisis," and because both sides were frightened by what almost happened, they signed a treaty banning aboveground nuclear tests in 1963; now people could hope that the Cold War would end peacefully. To keep misunderstandings from causing another crisis in the future, a direct telephone line, the "hot line," was installed between the White House and the Kremlin (we saw in Chapter 3 how a lack of communications had caused the War of 1812).

Within US borders, the main issue, besides the economy, was civil rights. Because the lives of Black Americans had improved in incremental steps during the Roosevelt, Truman and Eisenhower years, black leaders were now calling for full equality between the races. The Attorney General, Robert F. Kennedy, cooperated by ending segregation in interstate transportation, and moving to guarantee the voting rights of blacks; the federal government also opened more jobs to blacks than it had before.(48) There was a repeat of the Little Rock incident in October 1962, when troops were sent to Oxford, MS, to protect a black student at the University of Mississippi from rioters. This period also was the peak of Martin Luther King's career. In May 1963 he led a march through the streets of Birmingham, AL, where they were met by fire hoses and police dogs; in the riot that followed, 3,300 were jailed, including King. Before the year was over, parades, demonstrations and sit-ins took place in some 800 cities and towns across the country. There were some acts of violence, and casualties (e.g., a "freedom walker" shot in Alabama, an NAACP leader lynched in Mississippi, four black children killed in a Birmingham church bombing), but overall this was a peaceful revolution. Then in August, 200,000 Americans gathered in Washington D.C., to hear King make his most famous speech ("I have a dream") at the Lincoln Memorial.(49)

Who Really Killed JFK?

Kennedy didn't live long enough to get most of his domestic legislation passed, which included a civil rights bill and tax cuts to stimulate the economy. On November 22, 1963, he paid a visit to Dallas, TX for the purposes of extending good will and raising funds for the next year's elections. The limousine leaving the airport carried, besides the driver and Secret Service agents, the president and first lady, Texas Governor John Connally, and Connally's wife. Suddenly three shots rang out from a sixth-story window of the Texas School Book Depository, a building the motorcade had just passed. One bullet struck the president in the back and came out his throat; a second struck him in the head. Though the limousine rushed to the nearest hospital immediately, he was beyond hope. Connally was also seriously wounded by a bullet, but he later recovered.

The police quickly apprehended a suspect at the building mentioned above; a never-do-well named Lee Harvey Oswald. Oswald had enlisted as a Marine in the mid-1950s, and was trained well enough in using a rifle to qualify as a sharpshooter. However, he also had pro-Marxist sympathies; in 1959 he defected to the Soviet Union, was given a job at a factory in Minsk, found life in that city too boring, and managed to return to the US in 1962. A police officer had been shot and killed in that part of Dallas on the same day as the president, so when the police tracked Oswald down in a movie theater, they arrested him on a charge of committing both murders. Then things took a bizarre turn just two days later; when Oswald was being transferred from the police station to a jail, he was fatally shot by Jack Ruby, a local nightclub operator. In the trial that followed, Ruby claimed he had only done it because he was distraught over Kennedy's death; no one set him up to silence Oswald before he told his side of the story. Though put in jail for his actions, Ruby went to the grave without ever changing his defense; thus, we may never know his real motivations, or Oswald's.

Because of the above events, the Kennedy assassination wasn't an open-and-shut case. Whereas Lincoln's assassin had a handful of accomplices, and the killers of Garfield and McKinley acted alone, it has never been established what sort of conspiracy--if any--was behind the JFK assassination. A commission set up by Chief Justice Warren shortly after the assassination concluded that Oswald was the only gunman. In Congress, however, the House Select Committee on Assassinations investigated the case from 1976 to 1979, and came to a different conclusion; besides the three shots, a fourth one was heard coming from a nearby grassy knoll. This would mean a second gunman was involved, but if so, he missed and was never caught.

The incomplete resolution of the case has led to a variety of conspiracy theories about who wanted to kill Kennedy, and why. Wikipedia has no less than twenty-seven conspiracy theories listed on its page about the subject. Candidates for the mastermind behind the plot include the CIA, the KGB, the Mafia, J. Edgar Hoover, Vice President Johnson, former Vice President Nixon, Fidel Castro, anti-Castro Cuban exiles, a faction of the military-industrial complex, the Federal Reserve, and so on. Leftists seem especially prone to these theories. Oliver Stone, for instance, suggested in his movie "JFK" that Kennedy was killed by right-wing extremists because he had second thoughts about Vietnam, and was planning to pull out American troops in 1964 or 1965. However, to accept Stone's theory, or those like it, you have to believe that Kennedy was about to become a leftist, and you have to forget three facts: (1) Kennedy fought communism; (2) Joe McCarthy got along well with the Kennedy family, when both he and JFK were senators; and (3) the man who pulled the trigger was a Communist wannabe.

Perhaps these theories are the reason for the transformation that occurred among liberals in the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination. The Left acted like it had lost its innocence, and subsequent events like Vietnam and Watergate seemed to reinforce the new attitude. In the past liberals had believed that the United States could be a force for good in the world; now they were more likely to blame America first when things weren't going right, and demand perfect behavior from the United States, while overlooking the shortcomings of nations with left-wing governments. These neo-liberals called themselves the "New Left," to separate themselves from the "Old Left" that had run the Democratic Party for most of the past century.

The New Left briefly had its way in 1972, when it nominated its man, George McGovern as the Democratic candidate for president. However, he was defeated in a landslide, and more moderate Democrats regained control of the party. It wasn't until the beginning of the twenty-first century that the ex-hippies took over again, and this time they stayed in power. They also managed to make some converts from the Old Left. Teddy Kennedy, for example, was the only one of the Kennedy brothers to live past middle age, and as he got older, he grew more liberal; he fought tax cuts like the ones John introduced, never saw a spending bill he didn't like, and supported causes that were socialist and/or anti-American. The last representatives of the Old Left, like Connecticut Senator Joe Lieberman and former New York City Mayor Ed Koch, found they no longer recognized the party where they had spent most of their lives, and ended up campaigning for the Republicans. Finally, the revulsion of "Middle America" against the ideas and behavior of the New Left gave conservatism a new lease on life, as we will see later.

After leaving the White House, Jackie Kennedy referred to the JFK presidency as "Camelot," and admirers of the Kennedies have used the name ever since. She was thinking of the nostalgia people tend to have with the early 1960s, but it was also appropriate because all Camelot stories end tragically. And there are so many unhappy stories regarding the Kennedy family, that some talk about the "Kennedy curse." The paparazzi rarely gave Jackie any peace, to start with. Patrick, the third child of John and Jackie, died only two days after his birth in 1963. Jackie remarried in 1968; this time the husband was Aristotle Onassis, the owner of a very successful Greek shipping company and one of the world's richest men. However, Onassis in turn died in 1975, so after that she found work as a book editor, and enjoyed that so much that her final years were probably the happiest of her life. Bobby Kennedy, like his brother, fell victim to an assassin, as we will see when we look at the 1968 presidential election. David Kennedy, a son of Bobby, died of a drug overdose in 1984, and another son, Michael Kennedy, died when he skied into a tree in 1997. A nephew, William Kennedy Smith, was the defendant in a highly publicized 1991 rape trial, from which he was acquitted. In 1995 John F. Kennedy Jr. founded George, a magazine that combined humor and politics, but then in 1999 he was lost at sea with his wife and sister-in-law, when his private plane went down near Martha's Vineyard. Perhaps the luckiest member of the Kennedy clan is Caroline, who has lived most of her adult life in relative obscurity, working as a New York City lawyer. About the only time Caroline got attention in recent years was in 2009, when somebody proposed that she fill the Senate seat vacated by Hillary Clinton. She turned down the offer, without giving a reason; perhaps she felt her luck would run out if she accepted?

Aside from the assassinations, the best-known tragedy had to do with Teddy Kennedy. On the night of July 18, 1969, he was driving home from a party on Chappaquiddick, a small island connected to Martha's Vineyard by a ferry. Drunk at the time, he took a bridge too fast and the car went off it, landing upside down in a tidal pool. Teddy managed to swim to safety, but his companion, a twenty-eight-year-old campaign worker named Mary Jo Kopechne, drowned in the car. Teddy later was found in a hotel on Martha's Vineyard, where he rested and made seventeen phone calls. However, instead of calling the police immediately, he waited ten hours to report the incident, and then did it because his mishap had already been discovered. This irresponsible behavior caused Americans to question Teddy's character, and it kept him from rising to any office higher than senator, though it didn't keep Massachusetts voters from reelecting him to the Senate, again and again.(50)

The "Great Society"

Lyndon B. Johnson had been in Congress for twenty-three years, before becoming Kennedy's vice president. He climbed to the top by knowing the right people; early on he got FDR's attention as an enthusiastic New Deal supporter, and over the years he carried on several highly successful "courtships" with folks who outranked him. From 1937 to 1949 he was a congressman, representing the 10th district of Texas. In 1941 he ran for the Senate, but his opponent, Texas Governor W. Lee "Pappy" O'Daniel, was very popular, having been a successful flour salesman and radio personality before going into politics. While Johnson was declared the winner in unofficial election returns, the official returns said that O'Daniel won; on Election Night, Johnson went to bed ahead by 5,000 votes, and found himself 10,000 votes behind when he woke up. It was a lesson Johnson would not forget.

Though still in Congress, Johnson became a commissioned officer in the Navy Reserves during World War II, and looked for a combat assignment. He got one in 1942, when President Roosevelt decided he needed a political aide he could trust, to investigate the situation in the southwest Pacific. Accompanied by two army officers, Johnson went to Australia, and General MacArthur put him on a B-26 bomber attacking Lae, a Japanese airbase on New Guinea. Not all of the bombers came back from that mission, and subsequent reports disagreed on whether Johnson's bomber came under enemy fire, and whether or not it had turned back before reaching the target, due to generator trouble. Despite this confusion, MacArthur awarded a Silver Star, a very high-ranking combat medal, to Johnson, though it wasn't even clear what LBJ had done to earn it; nobody else on that plane got one.(51) After Johnson returned, his testimony to navy leaders and to Congress got more men and materiel sent to the South Pacific; he may have gone for personal/political gain, but in the end he helped MacArthur's campaign considerably.

Johnson got to be a senator because of some ballot-box stuffing. He tried again for the Senate in 1948, and found himself running against another incumbent Texas governor, Coke Stevenson. Nobody got a majority of the votes in the primary, so a runoff primary was held, and this time the results were so close that a recount had to be done. During the recount, strange things happened; in the town of Alice, TX, the first count had Johnson ahead by 1,000 votes, but the second count gave him a lead of about 1,200 votes. Between the first and second count, some 202 ballots had been found that were all for Johnson; even more curious, all of the ballots used the same handwriting and the same ink, and had been cast in alphabetical order. Voting was rigged in other parts of south Texas as well, including 10,000 ballots in Bexar County alone. When the second count was finished, Johnson was declared the winner by only eighty-seven votes, out of nearly a million cast.(52)

Needless to say, Governor Stevenson thought fraud had been committed. The case went all the way to the US Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of Johnson's vote count. After that, while he was in the Senate, Johnson carried the sarcastic nickname of "Landslide Lyndon," because of his supposed razor-thin margin of victory. It wasn't until 1977, four years after Johnson's death, that a Texas judge, Luis Salas, confessed to have certified 202 fraudulent ballots for Johnson.

LBJ became an important figure in the Senate while still a freshman. Following the path blazed by Truman, Johnson used his position in the Senate Armed Services Committee to investigate defense costs and efficiency, and he did such a good job of it that he was appointed Senate majority whip in 1951. With the Republican victory in the 1952 election, he became Senate minority leader, and when the Democrats regained control of the Senate in 1954, that title changed to Senate majority leader. He remained the most important senator for six years, until he made his first bid to become the Democratic candidate for president; his second-place finish at the convention was strong enough for Kennedy to pick him for the vice presidential spot. Johnson was in Dallas on the fateful day of Kennedy's death, and was sworn in as the 36th president aboard Air Force One, the presidential airliner.(53)

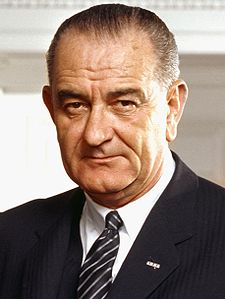

Lyndon Baines Johnson.

The nation was still in shock over the Kennedy assassination when 1964 began, and with it, the campaign for the 1964 presidential election. Though Johnson had not yet been tested as president, the only significant Democratic opposition he faced came from Alabama Governor George Wallace, who ran on a platform that opposed civil rights for blacks, and called for states' rights and "law and order." On the other side of the aisle, the Republicans were bitterly divided between Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, who represented the conservatives, and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, who represented the moderates. Rockefeller's image was tarnished by scandals regarding his marriage, so at the convention an effort was made to run another moderate, like Pennsylvania Governor William Scranton, but the conservatives stood firm and Goldwater was nominated on the first ballot.

For more than thirty years, conservatism was in exile; since the beginning of the Great Depression, nobody had been a spokesperson for conservatives on the national stage, and all the presidential candidates nominated by both major parties were either liberal or moderate. Now conservatives had their way at last, and Goldwater made that clear when he said at his acceptance speech: "I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue." However, Goldwater found it difficult to attract support beyond his conservative base; even moderate Republicans didn't want to campaign for him. Thus, Johnson found his job simple; all he had to do were make Goldwater look like a warmonger and a right-wing extremist. The result on Election Day was the biggest popular vote majority that any presidential candidate ever received, 61.1% for Johnson vs. 38.5% for Goldwater. The only states Goldwater won were Arizona, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina. If you compare maps, you will see this is nearly the opposite of what had happened in the two races between Eisenhower and Stevenson. Also note that all but one of the Goldwater states are in the Deep South; this was the first time that a Republican had more support in the South than in the rest of the country.

Johnson was almost unstoppable when it came to passing legislation, too. In Congress he had learned how to interrogate and bully others into cooperating with him, and while the nation was grieving over Kennedy, he could finish anything that Kennedy had started.(54) In 1964 he passed Kennedy's civil rights bill, as the Civil Rights Act, which prohibited discrimination in employment and in public buildings like restaurants and hotels, on the basis of race, creed, sex, or nationality. Surprisingly, although Johnson was a Southerner, he imposed this law on Southern white Democrats with more force than Kennedy probably would have used, had he lived. This, along with the increasingly left-wing platform of the Democratic Party, encouraged blacks to become Democrats, and Southern whites to become Republicans; the age of the solidly Democratic South ended with the Johnson years. The Civil Rights Act was followed up with the Voting Rights Act in 1965, which enforced the Fifteenth Amendment, and banned requirements such as literacy tests that reduced the number of people qualified to vote. To top all this off, Johnson got the Kennedy tax cuts passed; this was the last time the Democratic Party was serious about lowering taxes (Clinton and Obama both promised tax cuts before they were elected, only to back out of their promises later, claiming that the government couldn't afford to give the people's money back).

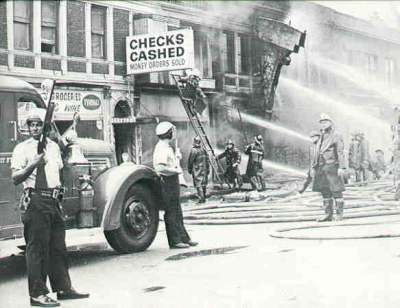

After passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act, some more hurdles had to be cleared before one could declare that racial equality had been achieved, but they would be minor by comparison. However, for some black Americans, progress was coming fast enough. This resulted in a split in the civil rights movement. Previously, civil rights leaders had believed they could get what they wanted by cooperating with the existing government and society (e.g., Martin Luther King was a Republican, believe it or not!), and resorting to civil disobedience when that failed. Now a rejectionist faction appeared, that refused to get along with whites, used "black power" as its slogan, and called on its members to "fight the power" of those in positions of authority. The oldest of these groups was a religious sect, the Nation of Islam, also known as the Black Muslims. In the mid-1960s they were joined by militant groups like the Black Panthers. Race riots in American cities were common during the "long, hot summers" of 1965 through 1968. These were caused not only by dissatisfaction with the rate of progress in civil rights, but also because of a realization that the percentage of men drafted to fight in Vietnam was disproportionately black.

A typical riot scene from the 1960s.

At a commencement speech for the University of Michigan in 1964, Johnson gave a name to his program: the "Great Society." He firmly believed that poverty, like racial injustice, could be eliminated by the actions of government. To do this he declared a "war on poverty," made the most sweeping changes in the federal government since the New Deal, and created the welfare state as we know it today. Chief among these were the following programs:

- The Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO), which oversaw the other programs below, and existed as a federal agency from 1965 to 1980.

- The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965.

- Medicare, a Social Security-type health care program for the elderly.

- Medicaid, same idea as Medicare but for younger folks who couldn't afford health insurance.

- The Job Corps, a vocational training program for young people, aged 16 to 24.

- The Food Stamp program, officially called AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children).

So how did the war on poverty go? Not too good! The Elementary and Secondary Education Act spent billions on educating poor children but produced no results; a 1977 study by the National Institute of Education showed that what the students learned in one year was usually forgotten in the next. Medicare and Medicaid did not improve the quality of health care available (A visit to the typical VA clinic will show what you get when the government pays the doctors!), and as more and more people demanded government-subsidized treatment, the cost of these programs, like Social Security, grew until it far exceeded what was initially predicted of them. The Job Corps spent as much as $21,333 per person on those it trained, but two thirds of those in the program failed to complete it. Furthermore, subsequent studies showed that among those who finished, only 12 percent found work in the field they were trained for, only 44 percent found any job at all, and most of those working were earning the minimum wage, or not much more than that.

The worst consequence of these new programs was that they took away the needy person's sense that he was responsible for his actions. In the past, if a poor person got married, stayed married, didn't have children outside of marriage, kept a job, and avoided spending too much on vices like liquor and gambling, he would eventually escape from poverty.(55) Accordingly, the charities that existed before the Great Society era (usually private organizations like churches) would evaluate candidates before helping them, to see if they were deserving of assistance. That all ended now; liberals called it "too judgmental" to say that a widow with children should be helped and a lazy "couch potato" shouldn't. The new programs, especially AFDC, allowed Uncle Sam to take the place of a husband/father, so unmarried mothers were now discouraged from marrying (because then the food stamps would stop coming), and an explosion of divorces and out-of-wedlock births was the result. For the men, long periods where the unemployed were eligible for payments meant that they could skip working, if they felt like it. Eventually, the recipients of public assistance would even view these benefits as a right, an entitlement. For them the so-called "safety net" had become a hammock. The original intention had been to meet the needs of the poor and unemployed while they tried, as quickly as possible, to pull themselves to the point where they didn't need help anymore; now many could stay needy indefinitely.

As columnist Walter Williams put it, the welfare state, with its subsidies for illegitimacy, destroyed the black family in ways that slavery and segregation had not done. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to figure out that governments can modify human behavior by taxing the behavior it wants to decrease, and by subsidizing the behavior it wants to increase. The programs of the Great Society, on the other hand, had done the opposite; they encouraged wrong behaviors and discouraged right ones.

Finally, when the lives of most Americans have gotten better, and their incomes have risen, the government has raised the standards of what constitutes "poor." Here is how the author put it in another essay on this site, A Packrat Nation:

"We are rich--in things, if not in money. The United States is the only country I know of where poor people are overweight, live in homes with air conditioning, own color TVs, and drive around in cars. Granted, those homes, TV sets and cars may not be the best, but one comparison with any Third World country, or even certain parts of Europe, will show you how good life is for us Americans."

Jesus said in the New Testament that "the poor you always have with you" (Matt 26:11, Mark 14:7), so one wonders if the definition of "poor" has been changed to fulfill those scriptures, and to make sure that too many Americans don't climb above the current poverty line. Perhaps some folks in Washington are simply trying to keep their jobs, because the federal programs for fighting poverty might be disbanded if enough Americans felt they had succeeded. The result is that after more than forty years and trillions of dollars in spending, the percentage of people living in poverty is about the same as it was before. So what is the final score in the "war on poverty?" Poverty won, or at least it held its ground.

Johnson came to grief because he had a real war to fight, at the same time as his "war on poverty." In 1964 the communist guerrilla movement in South Vietnam, the Viet Cong, was on the verge of winning, controlling nearly the entire countryside.(56) A battle between an American destroyer and three North Vietnamese torpedo boats, off the coast of North Vietnam (August 2, 1964, henceforth called the Gulf of Tonkin Incident), gave Johnson the excuse he needed to get the United States more heavily involved than it was already. Charging that the North Vietnamese had fired on the destroyer, Johnson got Congress to pass the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which gave him permission, without a declaration of war, to do whatever was necessary in order to assist "any member or protocol state of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty." The new involvement meant first bombing North Vietnam, then sending over combat troops to fight on the side of the South Vietnamese. For the United States, the Vietnam War was on.

The United States went into Vietnam with the idea that the strength of its armed forces would turn the tide, only to find that this war was very different from any the Americans had fought in the past. Because this was a not conventional war, the enemy could be anywhere, not just along a front line, and the enemy army was not a conventional force, with tanks and uniformed soldiers. Americans had fought in the past against enemies that used guerrilla-style tactics (e.g., the Indian wars and the Philippine Insurrection), but even there they did not run the risk of surprise attacks from women and children, which was the case in Vietnam. Bombing did not work very well either, because the Viet Cong could get most of what they needed by living off the land, and North Vietnam had few targets worth hitting, aside from Hanoi and Haiphong, and the Americans were careful not to hit those, feeling it would be an unacceptable atrocity. In fact, the whole US strategy was strictly defensive; though the US knew that North Vietnam was supporting the Viet Cong, no effort was made to invade North Vietnam or topple the North Vietnamese government, because of fears that such a move would trigger Soviet or Chinese intervention, the way it had in Korea.

Meanwhile in Saigon, the United States attempted social engineering on the South Vietnamese government, in order to avoid supporting another dictator like Ngo Dinh Diem. The problem here was that Washington wanted to turn South Vietnam into a working democracy, when the only types of government the Vietnamese had any experience with were monarchy and foreign rule (namely Chinese and the French colonialism). Constitutional monarchy was not an option, either, because Diem had kicked out the last emperor, so the generals were the only figures strong enough to bring stability, especially Nguyen Cao Ky (ruled 1965-67) and Nguyen Van Thieu (ruled 1967-75). As one might expect, this did little to endear the Saigon regime with the Vietnamese.

The first American combat troops halted, but did not turn back the Viet Cong, so Johnson, his advisors and the commanding generals decided that more men and more weapons were needed. For all of Johnson's second term, it was felt that victory was just around the corner, if only more firepower could be provided and more money could be sent to Saigon. Accordingly, the size of the force committed escalated every year, from 27,000 men in 1964 to 543,000 in early 1969. And because Americans would stay involved in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia until the fall of Saigon in 1975, this would be the longest war in US history. For Americans born in the 1950s and 1960s, the Vietnam War would be the ultimate conflict, the one against which all others would be measured.

Americans changed their minds about the war when the Tet Offensive took place in early 1968; here the Viet Cong launched an astonishing wave of surprise attacks all over South Vietnam. At the time it was a tactical disaster; the Americans still had superior firepower and training, and the Viet Cong lost so many guerrillas that they had to stop pretending that they were fighting a civil war by themselves. The next time the Communists staged an offensive, in 1972, it would be an invasion of the South by conventional North Vietnamese forces. Today, however, Tet is considered a Communist victory, because it broke the American will to fight. This was soon followed by news of Khe Sanh, a US Marine base near the Laotian border that was besieged by North Vietnamese troops for three months, and the notorious My Lai massacre. Soon Americans no longer believed they could win this "romp through the swamp"; they just wanted to leave Indochina as quickly and graciously as possible.

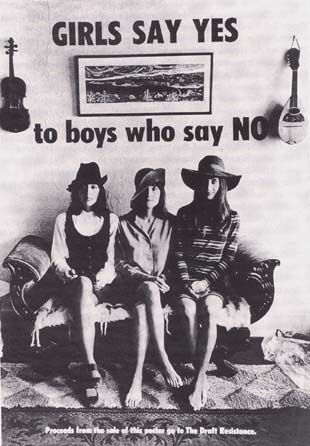

The second half of the 1960s is now remembered as the most violent period in recent US history, and not just because of the fighting in Indochina. As mentioned earlier, there was racial unrest in the cities, coupled with the black power movement, and now student unrest appeared as well. College students formed antiwar groups like the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), burned draft cards, and staged demonstrations, chanting slogans like "Hell no, we won't go!"(57) Some also fled to Canada, to avoid getting drafted. Finally a counterculture movement, that of the hippies, made its presence felt. For a while the hippies were pacifists, called "flower children" because they decorated themselves with flowers and tried to bring about world peace by giving everyone a daisy. In 1967 100,000 flower children gathered in San Francisco for the "summer of love," where they listened to concerts from their favorite bands, and experimented with new ideas, behaviors, and styles of fashion. But this didn't solve the world's problems, so afterwards they turned into angry young rebels, rejecting the existing rules of society (those who opposed them were either called "straights" or "the Establishment") and accepting anything that went against the mainstream culture, especially nontraditional religions and the recreational use of sex and drugs.

Nixon Returns

Unlike most elections in recent years, for several months after the campaigns started, nobody knew who the major parties would nominate for the 1968 presidential election, in part because of all the unrest going on. The Democrats were divided into four factions, each of which favored a different candidate and distrusted the other three:

- Traditional blue-collar workers, labor union members and big-city bosses--the "New Deal" crowd--preferred to stay the course with Johnson.

- White intellectuals and college students backed the doctrinaire liberal, Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy, because he was also the first candidate to oppose the war.

- Ethnic minorities, especially Catholics, went with Bobby Kennedy.

- The favorite of conservative Southerners was Alabama Governor George Wallace.

The trouble didn't end with Johnson's departure. In April Dr. Martin Luther King was fatally shot on a hotel balcony in Memphis, TN, meaning that there would be more racial turmoil. The next two months saw fierce competition between McCarthy and Kennedy, with neither willing to support the other, should he get the nomination. Some narrow primary victories allowed Kennedy to move into first place, though he didn't have enough of a lead to beat his opponents in the first ballot at the convention. Then in June he was assassinated by Sirhan Sirhan, a Palestinian terrorist who didn't want Kennedy elected because he was a strong supporter of Israel.

Some of Kennedy's supporters switched to McCarthy, while others, remembering the bitter spring fight, turned to one of Kennedy's backers, South Dakota Senator George McGovern. Thus, with the left wing of the party divided, establishment Democrats had no trouble getting Humphrey nominated. However, the 1968 Democratic convention was the stormiest convention in recent US history. Besides the usual delegates and reporters, 10,000 hippies and antiwar demonstrators descended upon the convention site in Chicago, and they were met by 23,000 police and national guardsmen. Protesters threw rocks and bottles, and "pigs" was the cleanest name they had for the police. One hippie faction, the Youth International Party (Yippies), mocked the political process by nominating a pig, which they named "Pigasus the Immortal," as their candidate for president. The police responded with clubs and tear gas; tear gas was so heavily used that some of it got into Humphrey's hotel room. Viewers on TV saw a combination of riot scenes and speeches, while the mayor of Chicago, Richard Daley, defended the police by saying, "The police are not here to create disorder, they're here to preserve disorder."(58) Although the demonstrators and liberals elsewhere denounced these acts as "police brutality," the sympathies of most Americans were with those representing authority, not with latter-day anarchists. Still, the violence was a big turn-off for voters, and Humphrey's campaign never got over it.

The Republicans were also divided, though not as badly as the Democrats. The first Republican to throw his hat in the ring was Michigan Governor George Romney. Romney was handsome, energetic, and very successful at everything he did, whether he was a Mormon missionary, head of two major corporations, or governor. He must have seemed like the perfect candidate, because he also supported civil rights, and Republican leaders wanted to avoid another reactionary like Goldwater. Instead, he became one of the first casualties of the modern "sound bite." In 1965 he went on a fact-finding trip to Vietnam, and two years later, he told a reporter about it: "When I came back from Vietnam, I'd just had the greatest brainwashing [from the US military] that anybody can get." That trip had made him an opponent of the Vietnam War, but the damage by his poor choice of words was done; nobody wanted a president who claimed to have been "brainwashed." Editorials and talk shows made fun of him mercilessly, until Romney withdrew his name as a candidate in February 1968.

The same month saw Richard Nixon(59) make his comeback. Though he faced strong challenges from Nelson Rockefeller on the left, and California Governor Ronald Reagan on the right, Nixon was always the front runner; even before he entered the race, he was ahead of Romney in the polls. After he won the nomination on the first ballot, he chose Maryland Governor Spiro T. Agnew for his running mate; because virtually no one knew who Agnew was, "Spiro who?" became a Democratic campaign slogan.

Nixon the way most people remember him--in campaign mode, flashing the "V for Victory" sign with both hands.

Neither major party tried very hard to win the votes of conservatives, so Wallace stayed in the race, forming the American Independent Party and running as its candidate. Of the three, Nixon was the only one who talked about ending the war quickly. He also proposed ending the draft and creating an all-volunteer army; this would silence those who opposed the war primarily because they did not want to fight in it. When the voters found their choices to be Wallace, Humphrey and Nixon, Nixon looked pretty good. On Election Day the popular vote was very close, with Nixon only getting 500,000 more votes than Humphrey, out of more than 73 million cast. He got a healthy margin of the electoral vote, though (303 vs. 191 for Humphrey). As for Wallace, he got nearly 10 million popular votes and 46 electoral votes, by winning in five Southern states (Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas and Louisiana). This was the last time that an independent or third party candidate won any states or electoral votes.

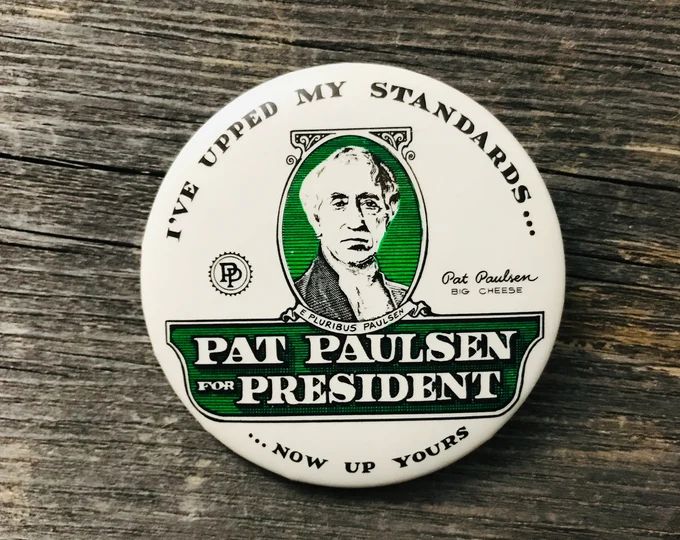

Wallace wasn't the only third party candidate for president in 1968. Another was comedian Pat Paulsen (1927-97), who ran a satirical campaign in 1968, and again every four years for the rest of his life. He claimed to represent the STAG (Straight Talking American Government) Party. At least he was funny, which is more than you can say about career politicians! Now about Vermin Supreme . . .

Johnson left the White House under an even darker cloud than Harry Truman had (see footnote #30). Aside from attending the Apollo 11 launch at Cape Canaveral (see below), he stayed out of the limelight, and the Democrats in turn treated him the way post-1956 Russians treated Stalin, not even mentioning his name if they could help it. Though he suffered two heart attacks (in 1955 and 1972), he could not stop drinking and smoking, and the third heart attack killed him, four years and two days after the end of his presidency.

The summer of 1969 is worth remembering because of two key events. First, the United States won the "space race," by landing men on the moon with the Apollo 11 mission. Throughout the 1960s, there was considerable concern that the Soviet Union would get there first (President Johnson once said, "I do not believe that this generation of Americans is willing to resign itself to going to bed each night by the light of a Communist moon"), and as late as 1964, when somebody asked Werner von Braun what he expected to find on the moon, he answered, "Russians." The Apollo program was delayed by more than a year when a tragic fire incinerated the first Apollo spacecraft on the ground, taking the lives of its three astronauts, but Neil Armstrong, Edwin Aldrin and Michael Collins still made it to the moon before the deadline set by JFK. After that, public interest in space exploration faded; three of the proposed ten moon missions were cancelled to cut costs, and the only manned missions after the Apollo program were in earth orbit, like those on Skylab, the first American space station.

In 1966, at the height of the "space race," NASA claimed almost 4.5 percent of the entire federal budget. By 2014, NASA was no longer launching manned spacecraft, and its share of the budget had fallen to 0.5 percent.

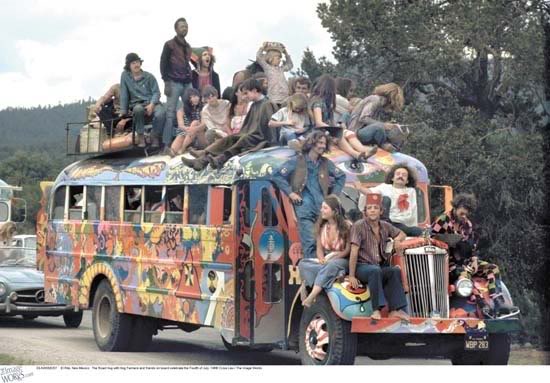

The other special event of 1969 was Woodstock, probably the most famous music festival of all time. Held on a farm in upstate New York, for three rainy days in August, an estimated 450,000 fans converged on the spot, and this concert was remembered afterwards as the high point of the hippie movement. The American counterculture enjoyed a few more good years before it disappeared from the stage, but as with the space program, most Americans shifted their attention to another cause, like environmentalism or feminism. In this case, it was because the Vietnam War was starting to wind down.

Far out, man! The Woodstock generation.

While we're on the subject of the hippies, what was their contribution, and that of the 1960s in general, to modern-day America, aside from "sex and drugs and rock and roll"? Well, the drugs got more dangerous as time went on, as those looking for a new high graduated from marijuana and switched to pills, heroin, LSD, cocaine, and eventually today's synthetic concoctions (e.g., methamphetamine, oxycontin). The federal government fought back with a "war on drugs," but so far this has shown about the same amount of progress (little or none) as the war on poverty. The invention of the birth control pill led to increased sexual activity, and a loosening of traditional moral values/taboos that came to be known as the "sexual revolution." However, the sexual revolution also caused a jump in the number of teen pregnancies and out-of-wedlock births, in spite of the availability of contraceptives, and the spread of sexually-transmitted diseases; the worst of the latter was AIDS, which broke out of its first incubation zone, central Africa, at the beginning of the 1980s.

A by-product of the sexual revolution and the civil rights movement is that other social groups, besides African-Americans, began calling for better treatment. The first to speak out were women, whose movement was first called "women's liberation," and later feminism. Feminists like Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem expressed their views by founding new magazines and organizations. Their demands legalized abortion(60), "equal pay for equal work," equal treatment under the law, and the replacement of "macho" men with more sensitive "metrosexuals." However, their biggest demand was an "Equal Rights Amendment" for the Constitution, and when the ERA bill expired without getting enough votes to be ratified, by either the states or Congress, feminism had trouble finding a new purpose, since by then the feminists had most of the other things they wanted. Today the largest feminist group, the National Organization for Women, is little more than just another faction in the Democratic Party.

Meanwhile, homosexuals, who had previously been invisible to mainstream America, became bold enough to start coming "out of the closet." The event which touched that off was a police raid in June 1969 on the Stonewall Inn, the only openly gay bar in New York City. Days of rioting followed, and one year later, on the first anniversary of the incident, it was commemorated in Los Angeles and New York City with the first "gay pride" parades. However, it was San Francisco, not NYC or LA, that had the largest number of homosexuals per capita, so that city became the center for gay and lesbian activity. Toleration of gays by "straights" began to grow after 1973, when the American Psychiatric Association stopped listing homosexuality as a mental disorder, and Harvey Milk, the first openly homosexual politician to be elected to public office, became a city supervisor in San Francisco in 1978. But not everything got better for them; the risky, promiscuous lifestyle of many gays has made them the group most likely to get AIDS, so today their life expectancy is still shorter than that of straights.

Finally, the hippies dabbled with any new religion that looked different from the church their parents attended. In Chapters 2 and 3 we saw some examples of how early Americans were spiritually active, but since then American society had grown increasingly secular. In 1869, for instance, Thomas Nast drew a cartoon of a businessman sitting at his desk with the devil whispering into one ear, while an angel stands behind a railing, and the businessman tells the angel, "I am too busy to see you now. Wait till Sunday." Thus, it was probably inevitable that the spiritual pendulum would swing back at some point, and it did in the 1960s. What was less predictable was the direction the swing would take. Some young people found the God of Christianity, but He was a more active God than the one previous churchgoers acknowledged; that marked the beginning of a new Pentecostal Revival. Others combined today's environmentalism with that old-time paganism to create the New Age movement, while still others experimented with the occult or eastern religions. In the process a bewildering variety of new cults were created, which ranged from ones that just looked silly (e.g., the Rastafarians, or the Divine Light Mission of Guru Maharaj Ji), to the enslaving (the Unification Church of Sun Myung Moon), to ones that were downright deadly. Examples of the latter included Charles Manson, who set up a commune with several young women, and used Satanism and LSD to make them commit a wave of crimes, including murders(61); the Rev. Jim Jones of the People's Temple, who took 900 of his followers to Guyana, and had them drink poisoned Kool-aid when federal authorities closed in, after the murder of a California congressman; and Heaven's Gate, a group of castrated UFO worshipers who committed suicide when they thought a comet had come to take them away (they left their website running, though). And see footnote #91 for what happened to another cult, the Branch Davidian sect.

Now back to the narrative. Nixon had said during the 1968 election that he had a secret plan for ending the war. He never said what it was, but it probably came in two phases. The first phase was the withdrawal of American troops, which began in 1969. This was called "Vietnamization," because the Americans trained and equipped the South Vietnamese army to fight on its own, with US assistance limited to air support. However, the war got worse before it got better. In 1970 the war spilled into Cambodia, which until then had been Indochina's neutral corner. For years North Vietnam had been sending supplies to the Viet Cong via the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which ran through eastern Laos and Cambodia, and the Communists had taken refuge in Cambodia when things got too hot for them in Vietnam, so it was a neutral nation in name only. When a pro-American general, Lon Nol, overthrew the Cambodian monarchy and proclaimed the "Khmer Republic," the United States found itself backing two friendly but incompetent governments in Indochina. Soon American and South Vietnamese forces crossed the border, to defend the Cambodian regime from its own communist insurgency; it was hoped that a successful operation here would give them the upper hand against the insurgency in Vietnam.

Back in the US, a lot of Americans, especially leftists who didn't understand that wars can't always be fought by a set of rules (or within a fixed space), were outraged at the new conflict, and saw the US intervention as a violation of Cambodian sovereignty. Antiwar demonstrations got ugly (e.g., at the 1970 Kent State massacre, National Guardsmen fired into a crowd of demonstrators, killing four and wounding nine), and for a while it looked like the United States was going to tear itself asunder. Some folks were probably relieved when the American expedition returned to Vietnam a few weeks later, though American planes continued to bomb targets in Cambodia until 1973.

Nixon's initiative to normalize relations with China and the USSR was most likely the other phase of his plan to end the Vietnam War, because the Chinese and the Russians would be less eager to support their Indochinese clients if it succeeded. To the reader, this may be a bit of a surprise; we saw that Nixon had been known as a "commie-baiter" in the 1950s. However, as vice president he had learned how to deal with Communist leaders (e.g., his 1959 "Kitchen Debate" with Nikita Khrushchev). Moreover, people with a reputation for acting like hawks can find it easier to make peace than doves can, because they aren't as likely to be accused of selling out to the enemy. France had produced another example a decade earlier, when Charles de Gaulle became president, and the former general used his new position to negotiate an end to the Algerian War, under terms that would not have been acceptable if any other French leader had agreed to them.(62) Indeed, when Nixon announced that he would visit Communist China, a place that the United States had no dealings with, some observers remarked, "Only Nixon can go to China." Late in 1971 the United States stopped opposing efforts to seat China as a member in the United Nations (however, the subsequent vote in the UN to expel Taiwan, which also called itself "China," was not what Washington had in mind). The door-opening visits came in 1972, with Nixon traveling to China in February, and the Soviet Union in May. With the Russians, Nixon began talking about cooperation in matters like space exploration and trade, and they signed a new treaty to limit the number of nuclear weapons; the next few years would be known as the era of Détente, after a French word meaning "disengagement." Although the Cold War had a few more years to go (it didn't really end until the fall of communism in eastern Europe, at the end of the 1980s), many Americans now felt it was over.(63)

On domestic issues, Nixon turned out to be less conservative than the Republicans who came after him. Increasing concerns about mankind damaging the environment led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency, the passage of several bills curbing air and water pollution, including a ban on the pesticide DDT, and the scrapping of a program to built the Supersonic Transport (SST), an airliner that could travel faster than the speed of sound, because of fears over the effect of sonic booms on nature. With the economy, inflation had become a serious concern in the 1960s, and Nixon believed in the Keynesian model, believing that the government can control prices. When milder measures didn't work, the administration imposed across-the-board wage and price controls in 1971. Passing a law saying that something cannot be sold for more than a specified price can slow inflation, but it doesn't stop it. It never does; check out what happened when Diocletian tried it, more than 1,600 years earlier. By preventing the law of supply and demand from running its course, the laws make it easier for people to hoard certain goods, so prices will continue to rise; when Nixon released the controls in 1973, inflation came back in double-digit figures, and the recession that followed produced an especially painful effect called "stagflation," where prices continued to rise even while people were out of work and the stock market was falling. Bouts of inflation and stagflation would be a major challenge for Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, too.(64)

"All the President's Men"

On June 13, 1971, Nixon picked up The New York Times, and saw a wedding picture of his daughter Tricia, taken with him in the White House Rose Garden. He later claimed he did not read the story next to the picture, which came under the headline Vietnam Archive: Pentagon Study Traces 3 Decades of Growing U.S. Involvement, but to those around him, it marked the beginning of a constitutional crisis. The article was the first installment in The Pentagon Papers, a series of top-secret documents that gave the real history of US involvement in Vietnam, from 1945 to 1967. They had been taken to the Times by Daniel Ellsberg, a former Marine and State Department official who had been stationed for two years in Vietnam, and during that time he became disillusioned with how the US government was conducting that war. Among other things, the papers stated that the United States had no realistic plan for winning the war, but for political reasons the government and the military felt they had to keep on fighting. This led to an expansion of the war by carpet bombing Cambodia and Laos, the staging of coastal raids on North Vietnam, and Marine Corps attacks--all of which had previously gone unreported. They also reported that Johnson had planned to bomb North Vietnam as early as 1964, when he was accusing Barry Goldwater of wanting to do that.

Most of The Pentagon Papers had been written during the Johnson presidency, but Nixon was embarrassed anyway, because this hurt his war effort. Moreover, most Americans up to this point had trusted their government to do the right thing, so they were shocked, too. John Mitchell, the Attorney General, contacted the Times the next day and ordered them to stop publication of the papers. Soon a court injunction followed, but the Times took the case to the Supreme Court, and won the right to publish the rest of the series. By then Ellsberg had released The Pentagon Papers to other newspapers, making it clear that the government would have to file injunctions against every newspaper in the country to suppress the story.

Nixon set up a secret team called the "plumbers," to stop future government leaks, by investigating the private lives of Nixon's critics and opponents. Their first assignment was to discredit Ellsberg, who had just given himself up and was charged with theft, conspiracy, and espionage. In September 1971, two of the plumbers, G. Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt, broke into Ellsberg's psychiatrist's office and tried to find information they could use against him. Then in May 1972, the White House secretly flew a dozen Cuban CIA commandos to Washington, D.C., with orders to assault or assassinate Ellsberg, but the crowd was too large to give them an opportunity. When news of the government's misconduct broke out, all charges against Ellsberg were dropped, and the antiwar movement felt vindicated.

Because Nixon had waited until his first term was nearly over to begin his foreign policy initiatives, and he left unfinished business concerning Vietnam and the economy, many Democrats thought they could do better. They were a familiar crowd, too. Most of the candidates in the 1972 presidential election had run in 1968: Hubert Humphrey, George Wallace, Eugene McCarthy, George McGovern, etc. About the only newcomer was New York Representative Shirley Chisholm, who generated interest by being both the first African-American and the first woman to run for the Democratic nomination. On the Republican side, Nixon faced only token opposition, and Spiro Agnew had not done anything to embarrass him, so the Republican ticket was Nixon-Agnew again.

For most of 1971, the Democratic front runner was Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine; he had been Humphrey's vice-presidential choice in 1968. Unfortunately, he found out that, like Romney in the previous election, the one in the lead is an inviting target. Two weeks before the New Hampshire primary, a local newspaper, The Manchester Union-Leader, published a faked letter which attacked the character of both Muskie and his wife. The actual author of the letter was never discovered, though FBI investigators thought it was a dirty trick from the White House "plumbers," now called the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP). Muskie responded by going to the Union-Leader's offices and delivering a tear-filled speech that defended his wife and attacked the newspaper's editor, a well-known conservative named William Loeb III. The crying episode convinced many New Hampshire voters that Muskie was too emotionally unstable for the job, and though he won the primary, he was only nine percentage points ahead of McGovern. After that, his campaign crashed and burned, never regaining the momentum it had lost.

With Muskie gone the three Democrats most likely to win were Humphrey, McGovern, and Wallace. Humphrey won several Northern primaries, but never could get in first place. Wallace scored some impressive victories in the South, but while campaigning in Maryland, he was shot in an assassination attempt that left him paralyzed from the waist down. Although Wallace went on to win both the Maryland and Michigan primaries, his health eliminated him as a contender. It was McGovern and his campaign manager, Gary Hart (a future Colorado senator and presidential candidate), who put together the winning campaign. McGovern had been running since January 1971 (it was rare in those days to start running more than a year before Election Day), and campaigned in more races than anyone else. Furthermore, being from South Dakota, he used the prairie populist approach that had worked for William Jennings Bryan, and his two main issues, ending the Vietnam War immediately and the legalization of marijuana, won the support of liberals who had previously gone with Eugene McCarthy. Finally, ultra-liberal Democrats (the "New Left" mentioned previously) gained controlled of the party apparatus, and in the name of making elections more fair to the voters, they ordered that more primaries be held, so that the voters, rather than the party leadership, would choose most of the delegates to the convention. However, at this stage they kept the "winner-take-all" rule regarding delegates, so when McGovern won the California primary, and got to keep all the delegates from the most populous state, his nomination was in the bag.

Meanwhile, the Committee to Re-Elect the President was up to its tricks again. The Democratic National Committee had its Washington, D.C. headquarters in an office adjacent to the Watergate Hotel, and the White House "plumbers" installed bugging equipment there. On June 17, 1972, five burglars were arrested after they broke into the headquarters; one of them was James W. McCord, the security director for CREEP. Ron Ziegler, Nixon's Press Secretary, dismissed the break-in as a "third-rate burglary attempt," and it didn't keep Nixon from winning the election, but make a note; you'll be hearing a lot more about Watergate shortly.

Once the leftists were running the Democratic Party, they quickly showed their lack of experience. First of all, the convention was mismanaged, so that the acceptance speeches were held at 3 A.M. (remember, this was before the invention of Tivo and even VCRs). Second, McGovern chose Missouri Senator Thomas Eagleton as his vice presidential candidate, without doing a thorough check on his past. Shortly after the convention, word leaked out that Eagleton had received electroshock therapy as treatment for mental illness. At first, McGovern said he backed his running mate "1,000%," but three days later, concerned over the attention this would draw from his campaign, he dumped Eagleton from the ticket. This flip-flop caused quite a few voters to question McGovern's judgment and trustworthiness. Eventually he picked a safer choice, R. Sargent Shriver, to replace Eagleton.

By this time, Nixon was riding high in the polls, and probably was unbeatable. Besides the Eagleton affair, McGovern was so liberal that he alienated many Democrats; a "Democrats for Nixon" campaign popped up, and as conservative commentator Robert Novak put it, McGovern was seen as the candidate for "abortion, amnesty and acid." Finally, the last combat troops had left Vietnam that summer, so an end to the Vietnam War was in sight. When news headlines in late October announced that the two negotiators, Henry Kissinger and North Vietnam's Le Duc Tho, were on the verge of reaching an agreement, it was all over for McGovern's campaign. On Election Night the popular vote went 61-38 in favor of the Republicans, and 49 states voted for Nixon. Only in Massachusetts and the District of Columbia did a majority vote Democratic. Afterwards McGovern joked that he had wanted to run for president in the worst way--and that he had done so.(65)

One week after Nixon's second term began, the United States, North and South Vietnam, and the Viet Cong signed a cease-fire agreement in Paris. Under the terms, all sides agreed to immediately halt all military activities, and North Vietnam agreed to release the American POWs (prisoners of war) it was holding. 145,000 North Vietnamese soldiers were allowed to remain south of the demilitarized zone, and Vietnam was declared a divided state, with one government in the north, and two (President Thieu's regime and the Viet Cong) in the south. With that, active American involvement in Vietnam ended.(66) Later in 1973, another cease-fire ended the fighting in Laos and established a coalition government there, leaving Cambodia as the only place in Indochina where the factions wouldn't talk peace.