| The Xenophile Historian |

A History of Russia

Chapter 5: SOVIET RUSSIA, PART III

1945 to 1991

This chapter is divided into three parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| The February Revolution and the Provisional Government | |

| The Bolsheviks Take Over | |

| The Russian Civil War | |

| The Russo-Polish War and the Comintern | |

| The New Economic Policy | |

| The Struggle to Succeed Lenin |

Part II

| The Nightmare of Stalinism Begins | |

| Prelude to World War II | |

| The Winter War | |

| "The Great Patriotic War" | |

Part III

The Cold War Begins

World War II permanently changed the world's political balance by leaving Germany, Italy and Japan in ruins, France demoralized, and Britain exhausted. The USA and the USSR, on the other hand, came out of the war stronger than before, and they had very different plans for the postwar world. The weaknesses in the wartime alliance were covered up while Hitler was the main enemy, but they became apparent before the war ended. The last major attempt to save the alliance was the Potsdam Conference, which was held in a suburb of Berlin in July-August 1945. Franklin Roosevelt had died in the five months since Yalta, and Winston Churchill was voted out of office in the middle of the proceedings; their successors, Harry Truman and Clement Attlee, were far less experienced in international affairs. Although the three leaders put on a show of solidarity for photographers, they accomplished little. After Potsdam the rivalry between East and West grew into "The Cold War," so called because it involved words and threats of physical force rather than actual fighting. Several key incidents between 1945 and 1950 mark the cooling of relations between the former allies:

1. The Soviet domination of eastern Europe.

2. The partition of Germany.

3. The Soviet Union attempted to set up a communist government in northwestern Iran, and demanded that Turkey allow the building of Soviet military bases on Turkish territory. US President Truman and the United Nations pressured Stalin to leave Iran alone.

4. Albania, Yugoslavia and Bulgaria (though not the USSR) supported Greek communist guerrillas in an attempt to overthrow the pro-Western Greek government. In response to #3 and #4, the US sent a $400 million aid package ("The Truman Doctrine") to Greece and Turkey, saving those countries from falling into the Soviet sphere of influence.

5. The poverty of war-ravaged Europe and the alarming power of the Communist parties in France and Italy made the US launch a $1+ billion economic aid package, called the Marshall Plan, to repair the continent in 1947. It was a complete success, creating the dynamic economies of western Europe that still exist today. The countries behind the Iron Curtain were also invited to participate, but Stalin would not accept any money with the strings of US influence attached to it.

6. Yugoslavia remains communist, but breaks with the Soviet Union.

7. To contain Soviet expansionism, the Western countries formed a series of economic and military alliances, the most successful being NATO, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Others modeled after NATO include SEATO (Southeast Asia), CENTO (the Middle East), OAS (Latin America), and ANZUS (the south Pacific). To oppose the West, the Soviets formed their own series of alliances: the Cominform (a political alliance) in 1947, the COMECON (an economic alliance) in 1949, and the Warsaw Pact (a military alliance) in 1955.

8. China falls to communism after years of civil war. In the same year (1949) the USSR ended the American nuclear monopoly by exploding an A-bomb of its own.

9. In various places the Cold War became a hot one, as the US and the USSR supported opposing sides in local brush wars, starting with Korea (1950-3) and French Indochina (1946-54). Americans and Soviets never fought each other directly, but often there was the danger of a war by proxy turning into World War III.

These events are covered in more detail in the other history papers on this website:

Europe.

Turkey & Iran.

China.

Korea.

Indochina.

Recompression at Home

After almost twenty years of hardship from the Five Year Plans, the purges, and World War II, the Soviet people were hoping for a freer, more prosperous life. But those hopes were quickly dashed as the Cold War began. Stalin launched a fourth Five-Year Plan in 1946 to bring a quick recovery from the wartime destruction, and announced that austerity, hard work, and rigid discipline would continue for some time to come. He pointed out that the ultimate enemy of the Soviet Union, capitalism, was still around, and that "so as capitalism existed, the world would not be free from the threat of war." Therefore Soviet citizens would have to be ready for yet more sacrifices and dangers.

Always preoccupied with security, Stalin spent the postwar years further strengthening his control over the country. He was so thorough at this, in fact, that the years 1945-53 are the most repressive in Soviet history. Western art, literature, clothing and lifestyles (even jazz) were banned, and foreign tourists were not allowed to visit the USSR until 1958. Stalin was so leery of foreign news that he did not even allow announcements of the 1949 communist victory in China until Mao Zedong visited Moscow at the end of the year.

During and immediately after the war 1,250,000 people from seven ethnic groups of dubious loyalty (Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Kalmyks, and four smaller minorities from the Caucasus) were accused of collaboration with the Nazis and deported to Central Asia and Siberia. The unruly Ukrainians were next on Stalin's blacklist, but even he had to concede that there were not enough trains in the USSR to get rid of all 40 million of them. Stalinist rule was toughest in those areas that had just come under Soviet rule since 1939, and the Catholics living in those areas were regarded as untrustworthy and forced to join the Orthodox Church. This resulted in a strange spectacle as the officially atheistic Soviet state threw its powers of coercion behind the Orthodox clergy.

At the same time came new episodes of anti-Semitism. Officially it was justified on the grounds that many Jews in the Red Army had defected to the West from East Germany, and Stalin suspected that Soviet Jews were sending military secrets to their relatives in the United States. But little actual persecution took place until the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. This was because many Israelis were socialists and/or immigrants from the USSR, giving Stalin some hope that Israel would join the Soviet Bloc after independence; the USSR even voted for the 1947 UN mandate that created the Jewish state. But because Israel is a parliamentary democracy, the Israelis have preferred to ally themselves with the West almost from the beginning. The final blow came when the first Israeli ambassador to the Soviet Union, Golda Meir, came to Moscow and received an enthusiastic welcome from Soviet Jews that made Stalin intensely jealous. Jewish organizations were suppressed by the state, and Jews in the Communist Party were removed from their posts. To avoid comparisons with the pogroms of the tsars, Stalin called this campaign "anti-Zionism."

In February 1953, nine doctors, most of them Jewish, were accused of poisoning Andrei A. Zhdanov (the Leningrad party chief and Stalin's favorite minister from 1934 to 1948), and of plotting to do in other generals and Politburo members. During the previous year Stalin called his henchmen spies, and Molotov lost his position as foreign minister because of his Jewish wife; she was sent to a labor camp without her husband even protesting. Alleged "Titoists" and "Zionists" were already being arrested and put on trial in eastern Europe. A new wave of purges, especially an anti-Jewish one, appeared to be beginning, and plans were made to deport all Soviet Jews to an autonomous region set aside for them on the border of Manchuria. But fate intervened; Stalin died of a cerebral hemorrhage on March 5, 1953. The politburo quickly released the victims of the "Doctor's Plot."(17)

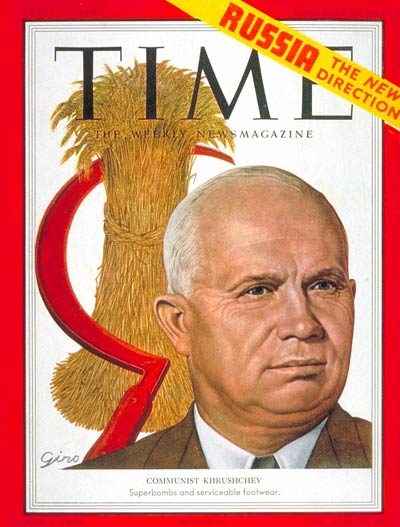

The Khrushchev Years

Stalin's handpicked successor, Georgi M. Malenkov, found that nobody wanted him around, now that Stalin was gone. He only held the post of secretary general for nine days before he stepped down to become premier, giving the top post to a junior politburo member, Nikita Sergeevich Khrushchev. Three months later police chief Beria tried to seize power for himself; he was arrested by army sentries and executed.

Nikita Khrushchev was born in 1894 to a small farmer in the Ukraine. He only had three years of formal schooling and struggled to make ends meet as a miner and locksmith, until he joined the Communist Party in 1918. He rose swiftly after he got the attention and patronage of Lazar Kaganovich, the Ukrainian party boss and the last Jewish member of the Politburo. By 1934 he was a member of the Central Committee, and in the Politburo by 1938. At that time Stalin transferred him to Kiev and placed him in charge of the purges in the Ukraine; that move probably saved his life. The other senior Politburo members thought that this self-educated peasant worker with a simplistic mind, extremely crude manners and a preoccupation with agriculture could be easily manipulated, but by 1955 he showed that the tail could wag the dog, by firing Malenkov and installing Nikolai Bulganin as premier.

Khrushchev's interest in agriculture was not misplaced because the annual harvests had been exceptionally poor in recent years. Stating that "the agricultural sector" had become a major bottleneck for economic progress, Khrushchev tried to reorganize it along functional, more efficient lines. To start with, taxes on farmers were reduced and the government paid more for the food taken from them. Then came what was called "The Virgin Lands Campaign," in which thousands of young peasants were dispatched to Kazakhstan and west Siberia to plow up arable land there. At first it was his greatest success: by 1956 the amount of farmland in the Soviet Union had been increased by 87 million acres, or 50%. Corn, meat and milk production increased so dramatically that Khrushchev predicted the USSR's total agricultural production would overtake that of the United States by 1970. Those successes made Khrushchev very popular, and encouraged him to make sweeping changes in other areas as well.

During Khrushchev's first three years it seemed that Stalin still controlled the Soviet Union from the grave. His monuments were visible everywhere; everybody in the government was there because he had stayed in Stalin's good graces; and only 12,000 of the five or six million prisoners that were still living in the Gulag had been freed. The Twentieth Party Congress in February 1956 seemed to continue this trend when it opened with a tribute to the late "Great Leader and Teacher." But on the last day, after the routine work was finished, Khrushchev suddenly convened an extraordinary session that no foreigners were allowed to attend. For the next four and a half hours he stunned the world by giving a passionate speech that denounced Stalin's personality, methods and policies with words that only the most virulent anticommunists would use, calling him a "criminal murderer" and a "purveyor of moral and physical annihilation," among other things. He denounced the mass purges, calling all of the cases fabrications that crippled the country's leadership just before World War II began. He questioned Stalin's policy toward minorities, his rigid centralized planning of the economy, and accused him of driving Tito away.(18)

A wave of de-Stalinization followed the secret speech. The ethnic groups deported by Stalin to Siberia/Central Asia (except the Crimean Tatars) were immediately returned to their homelands. The political prisoners were freed, though not all were rehabilitated. Stalin's victims in the Red Army, like Marshall Tukhachevsky, were posthumously rehabilitated, as well as his political victims in the right wing of the Party; left-wing Party members like Kamenev and Zinoviev, however, were tainted by their association with Trotsky, and did not have their good names restored until 1988. The Gulag camps were closed, though some political prisoners continued to be held up until the Gorbachev era. Most of Stalin's pictures and statues disappeared from public places. In 1961 his remains were removed from a place of honor beside Lenin and buried outside Lenin's Tomb; that year also saw new names for the five cities named after Stalin.(19) But by discrediting Stalin, Khrushchev had also destroyed the myth that Soviet leaders were the infallible interpreters of Marxism-Leninism. He had unknowingly cast doubt on the legitimacy of all future leaders. If a sadistic monster could rule Russia for three decades and claim to be following Marxism correctly, how reliable could the system be? Russians learned for the first time to question authority, and the political dissidents that have been a part of Russian life since the 1960s got started as a result of the secret speech.

The effects of de-Stalinization were immediately felt in the satellite states. There the USSR had already loosened the grip on its empire slightly, to prevent a repeat of the riots that rocked East Germany in 1953. Despite this, riots broke out in both Poland and Hungary in 1956. Wladislaw Gomulka, the new first secretary of Poland, quickly managed to make a deal when Khrushchev flew to Warsaw. In Hungary, it took a bloody suppression of the rebellion with Soviet tanks to keep that state in the Soviet camp. For more about these affairs, see Chapter 17 of my European history.

Khrushchev's problems abroad were good news to the old Stalinists in the Politburo, who resented Khrushchev's popularity and feared being implicated as Stalin's henchmen. While Khrushchev and Bulganin were visiting Finland in 1957, Malenkov, Molotov and Kaganovich got an 8-4 vote from the Politburo to expel the secretary-general. Khrushchev rushed back, got Defense Minister Zhukov to convene the Central Committee, and persuaded it to vote in his favor; according to the Soviet constitution, it takes a no-confidence vote from both the Politburo & Central Committee to remove a secretary-general. His position now secure, Khrushchev fired the conspirators.(20) He also did not want to pay any political debts, so Bulganin & Zhukov were "retired" by 1958.

As the 1950s ended and the 60s began, Khrushchev was at the height of his career, popular at home and feared abroad. At this time nothing more symbolized the USSR's status as a world leader than the beginning of the space age. Between 1957 and 1965 the Soviet Union set one space record after another: the first satellite in orbit; sending space probes to the moon; putting the first man and the first woman in space; keeping a manned spacecraft in orbit for as long as five days; and the first space walk. But while Khrushchev was enjoying his successes, his mistakes were catching up with him. It has been said that Khrushchev's downfall was caused by three words beginning with the letter "C": China, Cuba, and corn. We will look in more detail at each below.

1. China: Mao Zedong regarded Stalin as a teacher and never approved of de-Stalinization. But the apparent Soviet superiority in rocket technology shown by the launch of Sputnik I caused Mao to put aside his feelings and urge Khrushchev to provide China with nuclear weapons so that a planned invasion of Taiwan could succeed. He argued that China was not afraid of a nuclear war with the West because there were now more communists than capitalists; if 300 million Chinese were killed, there would still be 300 million left alive to continue the war after both sides ran out of bombs. Horrified at this line of thinking, Khrushchev refused, and Mao accused the Soviet Union of "revisionism."(21) His suspicions were confirmed when Khrushchev enjoyed himself immensely on a trip to the United States in 1959, but left early when he came to the celebrations marking the tenth anniversary of Communist China in the same year. After that the mutual name-calling got worse, Russia withdrew its technical experts from China, and China demanded the return of Chinese territory taken by the tsars in the nineteenth century. China decided to bring home its nuclear specialists who were studying in the USSR, but the Soviet authorities refused to let the Chinese send planes to pick them up, insisting that there was a Red Army transport available to do the job. When the plane was finally allowed to leave, after much diplomatic haggling, it exploded in midair, killing everyone aboard in what was later described as "engine failure." After that China and the USSR were implacable foes for a generation, hating each other more bitterly than either disliked the "citadel of capitalism," the USA.

One year later (1961), another Stalinist, Enver Hoxha of Albania, also chose to break with the USSR. When Khrushchev heard the news, he shouted, "You have poured a bucket of dung on my head!", while Hoxha replied that he was not afraid of the Russians because he had 800 million Chinese to back him up.

2. Cuba: In 1959 Fidel Castro seized control of Cuba. We do not know if Castro was a communist at first, but US hostility drove him into the Soviet Bloc during the next two years. The thawing of Soviet-US relations in the late 50s was followed by a series of tension-raising incidents in the early 60s: the capture of an American spy plane pilot, Soviet-US rivalry for influence in the new nations of the Third World, an unsuccessful invasion of Cuba by US-backed guerrillas, and a world crisis caused by the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961. But the most dangerous event was the placing of Soviet troops and missiles in Cuba in 1962. To Khrushchev's surprise, US President Kennedy refused to tolerate this, mobilized American forces in nearby Florida, and threatened war if the missiles were not removed. Never did the two superpowers come closer to starting World War III than they did here. Khrushchev blinked first and removed the missiles when the USA promised not to invade Cuba again. The troops stayed, but the Soviet Union took an enormous blow to its prestige.

3. Corn: While all this was going on, the Soviet economy deteriorated. The agricultural situation was especially bad, with harvests in 1959 and 1960 that were far less than expected. At the 22nd Party Congress in October 1961, Khrushchev unveiled a vast twenty-year plan to revolutionize agriculture. The success of the Virgin Lands campaign made him set extremely high goals for this plan: grain output was to double, milk to triple, and meat to quadruple. He especially encouraged the growing of corn, ordering farms to cultivate that more than anything else. It was a disaster; the seeds, fertilizer, machinery, silos and experience needed were just not there. Bad land management caused the topsoil of the Virgin Lands area to be blown away, turning Kazakhstan into a dustbowl, and old agricultural regions like the Ukraine fell into neglect as manpower and machines were poured into Central Asia. To prevent starvation Khrushchev was forced to buy 6.5 million tons of grain from Canada and Australia in 1963, the first of the many grain purchases in recent Russian history.

Khrushchev's style of leadership and his blunders made him a national embarrassment; the most notorious example came during a 1960 UN speech, when he got so mad that he banged his shoe on the podium. The last straw was Khrushchev's announcement that he would divide the Communist Party in two and place the two halves under an agricultural and an industrial bureau, a move that gave him more power at the expense of other bureaucrats. The Politburo voted to expel him a second time in October 1964, and this time the Central Committee voted against him too. Khrushchev lost his job, but not his head; he lived in comfortable obscurity until he died of natural causes in 1971. Khrushchev is remembered for many things, but most of all he was the only Soviet leader to leave Russia a better place than it had been under his predecessor.

Brezhnev Takes Charge

Decades of imperfect one-man rule convinced the Kremlin that no Soviet leader should be allowed to wield as much power as Stalin and Khrushchev did, so the Politburo gave the positions of premier and secretary-general to two different members, Alexei N. Kosygin and Leonid I. Brezhnev. The arrangement worked for most of the 1960s, with Kosygin running the government and Brezhnev running the Party; during this time Kosygin was the more visible of the two because of his trips abroad. But Russia's political traditions, shaped by a psychological need for a single strong father figure, gradually reasserted themselves. By 1970 the technocratic Kosygin had been pushed out of the limelight by the party man, Brezhnev.

Leonid Ilich Brezhnev was the first Soviet leader who climbed to the top because of political connections rather than personal ability. Like Khrushchev, he was an ethnic Russian native to the northern Ukraine. Born there in 1906, he completed his high school education (the first secretary-general to do so) and worked as a public administrator in various posts until he joined the Party in 1931. At first he was just an engineer in the metallurgical factory of his hometown, Dneprodzerzhinsk, but when Stalin's purges removed his superiors, he was able to become the Party boss of a key industrial district, Dnepropetrovsk, by the end of the 30s. Serving as a political commissar, he came out of World War II as a decorated major-general, and returned to Ukraine, where he rebuilt a hydroelectric dam and a steel plant so quickly that he was promoted to the Ukrainian Politburo. In the 50s he was Party chief of first Moldova, then Kazakhstan; in the latter he gained the friendship of Khrushchev by personally managing the Virgin Lands campaign. By 1960 he was in the Politburo as Communist Party President, the third most powerful job. There he gained the know-how to claim Khrushchev's job when he got the opportunity in 1964.

As secretary-general Brezhnev's first priority was to put some order into the chaos left behind by Khrushchev. Khrushchev's unpopular policies, like the splitting of the Party, were eliminated, as well as his plan to take the private plots of farmers. There were also some experiments with supply-&-demand economics, as an alternative to the strict government control over workers that emphasized quantity over quality. Unfortunately this attempt at limited capitalism didn't catch on, because it was sabotaged by the Party's more orthodox Marxists, who feared losing power if it succeeded. A concession was made to ordinary Soviet citizens in the form of the Ninth Five-Year Plan (1971-5), which emphasized consumer goods like cars, food, and clothing rather than heavy industry, but overall the economy remained as inefficient as ever. Nothing symbolized this better than the regular purchases of grain from the United States, an embarrassment to a government that promised agricultural self-sufficiency long ago.(22)

Many Soviet leaders, concerned with the increasing freedom enjoyed by artists, writers and scholars since 1956, felt that the de-Stalinization campaign had gone too far in its criticism of Party leadership. The 60s and 70s saw a cautious reversal of the trend, beginning with official speeches that praised Stalin for his leadership of the country during World War II. Along with re-Stalinization came crackdowns on the political and religious dissidents; Alexander Solzhenitsyn, for example, was able to write openly under Khrushchev, but was exiled from Russia by Brezhnev. But the clock could not be turned completely back to the pre-1956 era, and this was reflected in the way the USSR treated the dissidents; rather than shooting them out of hand, they were deported, fired from their jobs, or subjected to other subtle forms of harassment. Before 1989 many dissidents were also placed in mental institutions; Brezhnev's KGB chief, Yuri V. Andropov, explained this by stating that any resident of the "worker's paradise" who hates the system is seriously ill and requires long psychiatric treatment. Andropov himself was a symbol of the new policy; in 1973 he became the first police chief to join the Politburo since the downfall of Lavrenti Beria twenty years before.

Since the dissidents were not allowed to organize into political parties, they had a multitude of viewpoints. They ranged from conservatives who wanted the tsars back (Solzhenitsyn), Marxist reformers, those who wanted a Western-style democracy (Andrei Sakharov), Jews who wanted to emigrate, and Christians who wanted to practice their faith without persecution. The most unusual dissident was Stalin's daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva (1926-2011, called Lana Peters in the United States), who emigrated to the West in 1967, came back in 1984 because she missed her family, and then left again one year later, alternating between stays in the United States and the United Kingdom during the last years of her life.

Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Doctrine & Détente

There were many changes in domestic policies under Brezhnev & Kosygin, but Soviet foreign policy remained pretty much the same. The satellites of eastern Europe gave them as much trouble as they had under Khrushchev, especially Romania, Czechoslovakia, and Poland. Brezhnev was able to tolerate the maverick behavior of Romania's strongman, Nicolae Ceaucescu, because Romania was not on the border of any NATO country, and because Ceaucescu showed no interest in spreading his ideas to other Soviet Bloc states. Czechoslovakia and Poland, on the other hand, deviated too far from the Moscow's ideology; the Czechs introduced "socialism with a human face," and the Poles organized an anti-communist labor union, Solidarnosc (Solidarity). The armed forces of the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia (1968), while martial law put down the uprisings in Poland (1981). However, unlike 1956, the USSR paid more attention to the criticism laid on it by the West and China, so it imprisoned the leaders of "the Prague Spring" and Solidarity, instead of killing them outright; thus, in both cases the dissidents lived to see happier days.

The Kremlin's response to what happened in Czechoslovakia and Poland is known as "The Brezhnev Doctrine": once a country joins the Soviet Bloc, the USSR will do everything it can to keep it there. Brezhnev also practiced this policy in those Third World countries that professed Marxism, like Vietnam, Angola, Ethiopia, Nicaragua and Afghanistan. The USSR also tried to woo neutral nations into its camp, but there the defeats (Indonesia in 1965, Ghana in 1966, Egypt in 1972, Chile in 1973, and Somalia in 1977) nearly offset the victories. The bottom line was that the USSR had no real friends anywhere, just alliances of mutual convenience.

Even more embarrassing was the behavior of the Communist Parties in western Europe. Their attitude was summarized in a statement made by the leader of the Spanish Communists, Santiago Carillo, at a 1976 conference of Communist parties held in East Berlin: "For years Moscow was our Rome. Today we have grown up. More and more we lose the character of a church." When the Kremlin declared that there was only one true way to socialism, the French, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese communists ("Eurocommunists") went their own ways, pursuing local ideas that they claimed were appropriate in their own countries, if not in Russia. Often the Eurocommunists entertained thoughts that were considered heresy in Brezhnev's Russia, like a tolerance for religion and noncommunist political parties. By the early 1980s the Soviet press even had to censor copies of the French communist paper L'Humanite' before they could be distributed in the USSR (unheard of in times when communists everywhere were in total agreement!).

If the Soviet economy stagnated under Brezhnev, the armed forces never had to go hungry. Every year the defense budget increased; indeed, it has been estimated that the amount spent on defense, space, and nuclear energy may have been as high as 20-25% of the GNP. Since most of the manned and unmanned space missions carried military payloads of one sort or another, the space program also got everything it wanted.(23) By 1968 the Soviet nuclear arsenal had grown to match that of the United States, but the buildup continued without interruption, until the Soviet Union had the largest war machine in history.

Despite the buildup and the adventures abroad, Moscow looked for a way to relax tensions with the West, a policy called Détente (French for disengagement). Negotiations to this effect were attempted by Kosygin when he visited US President Johnson in 1967. The big breakthrough came five years later when the next president, Richard Nixon, visited the USSR. During the Nixon-Brezhnev summit meeting, a number of agreements promoting scientific & cultural exchanges were drawn up, and Russia bought $750 million worth of US grain. Most important was the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT), which got rid of antiballistic missile systems (ABMs), and declared how many strategic weapons each side could have; the USSR got numerical advantages in missiles and submarines, while the USA had a greater number of total warheads. Nixon and Brezhnev had three follow-up meetings in 1973 and 1974. Détente's high point came in 1975, with a joint US-Soviet space mission, and a conference at Helsinki where the leaders of 34 nations (the USA, USSR, and every European country except Albania) recognized Russia's domination of eastern Europe in return for promises of improved human rights in the Soviet Bloc.

In 1977 Brezhnev and US President Jimmy Carter signed another arms treaty, called SALT II, but the Soviet-US honeymoon was over. In the years since SALT I, the Soviet Union talked peace, but continued to sharpen its sword in arms buildups as if there was no peace at all. In addition, the continuing adventurism in the Third World, and a lack of progress on human rights, caused the US Congress to reject SALT II. Soviet-American relations soured after that, and there was another series of "incidents" like those of the previous generation: Soviet intervention in Afghanistan and Central America; the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympic games by the US, followed by a Soviet boycott of the Los Angeles Olympic games four years later; the election of a conservative US president, Ronald Reagan, who rebuilt the US armed forces with increased funds and new weapons the Soviets did not have the technology to match; and the shooting down of a South Korean airliner by Soviet warplanes. It was the end of Détente, and the beginning of a new round of mutual distrust.

Gerontocracy Triumphant

During his later years Brezhnev built around himself a personality cult. Every time a special event, like a Party Congress, took place, he was awarded new honors. On his seventieth birthday in 1976, for example, he was awarded his third Hero of the Soviet Union medal and his fifth Order of Lenin. By contrast, Stalin only gave himself one Hero of the Soviet Union medal, for leading the USSR during WOrld War II. Two years later Brezhnev "retired" President Nikolai V. Podgorny, and added his job to the others he had.

During this time a withering of Marxism became obvious to outsiders. This trend began in World War II, when a British journalist noticed that during his three years as a war correspondent in Moscow, nobody tried to convert him to Marxism. Stalin's wartime propaganda had effectively caused a new form of Russian nationalism to replace Marxism as the driving force in Soviet society. The doctrine taught by Marx, Engels and Lenin had been slaughtered in the purges, by censorship that allowed no deviation from the Kremlin's viewpoint, and by repeated changes in official interpretations of it. By the time of Brezhnev, Marxism was destroyed as a credible system of thought; it was only taken seriously in the classroom, while everyday problems were solved by people who did what they thought was right and then explained it in Marxist terms later. The egalitarian principles of Lenin's day were largely forgotten, replaced by a new aristocracy. An entire government bureau, known by the innocent-sounding name of the "Administration of Affairs," maintained exclusive apartments, dachas, car pools, servants, and special stores for high-ranking Party members and their families, giving them the privileges once enjoyed by the tsars. The moral of the story could be that, as George Orwell would say, "All are equal, but some are more equal than others."

The Soviet leaders, many of them in important posts since the time of Stalin, refused to step down and let younger men take over. Consequently, in the late 1970s Russia became a true gerontocracy. By 1981 the average age of those in the Politburo was 69, and only two members, Grigori Romanov (58) and Mikhail Gorbachev (50), were under 60. But inevitably nature took its course. Kosygin died in 1980; Suslov and Brezhnev followed in 1982. Brezhnev, like Stalin, ended up dying twice: first in body & soul, and then in public opinion a few years later. Nowadays he and his friends, called collectively "the Dnepropetrovsk Mafia," are accused of incompetence and corruption. One joke compares the administrations of Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev to the operation of a train. Stalin shot the engineer and sent the conductor to the Gulag; Khrushchev rehabilitated the engineer and released the conductor; Brezhnev let the train go off the tracks and told the passengers to pretend it was still moving!

Because of the Byzantine nature of Soviet politics, Kremlin-watchers in the West resorted to looking for various symbols to understand what was going on. On the November 7th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, the Politburo members would line up in front of Lenin's tomb, and Sovietologists would guess that whoever was standing close to the General Secretary was currently in favor; they also rated a Soviet leader's standing by the number of people who went with him on trips abroad. If TV and radio programs were interrupted by a day or two of classical music, that was the best sign (before the official announcement) that a Politburo member had died.

Brezhnev's immediate successor was Yuri Andropov, his KGB chief. Andropov was 68 years old and too sickly to accomplish much. Three months after taking office, he went into the hospital for kidney dialysis, and spent the last year of his life there, while the outside world was told he had a cold. Thus, he died after 15 months in office. The next secretary general, Konstantin U. Chernenko, was three years older than Andropov, already terminally ill (he regularly missed major public occasions), and only held the top post for thirteen months (February 1984-March 1985) before he too succumbed to old age.(24) Under the ineffective rule of both, Soviet-US relations cooled to their lowest point since the Cuban missile crisis. Sometimes the poor relations are blamed on US President Ronald Reagan, because he never met with Brezhnev, Andropov or Chernenko, and was less willing to make concessions than the presidents before him. In Reagan's defense, you have to admit it's awfully hard to make a deal with someone who is always too sick to visit, and Reagan's good health was all the more amazing when you remember that he was the same age as Chernenko.

Gorbachev's Experiment

Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev was born in 1931, in a village near the city of Stavropol, just east of the Black Sea. Joining the Communist Party in 1952, he was too young to be affected by Stalin's purges, and that gave him a much different outlook from his predecessors. He rose gradually, becoming a Party organizer in 1962, the First Secretary of the Stavropol territory in 1970, the Central Committee Secretary of Agriculture in 1978, and a Politburo member in 1980. Upon Andropov's death, Gorbachev struggled with Chernenko and Romanov to take his place. The old guard had their way one more time, and Chernenko got the job, but Gorbachev was put in charge of so many departments in the following months (ideology, personnel, planning, and relations with foreign communists) that he was the natural choice when Chernenko's short reign ended in 1985. Once at the top, his first act was to consolidate support by removing the oldest government and Party members--as well as rivals like Romanov--and replacing them with his own supporters. By the time of the 27th Party Congress, in February 1986, more than half of the members of Brezhnev's Central Committee had been replaced.

The main theme of the Gorbachev years was rapid economic and political change. The names for the reform movement were glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring), and those two words were used enough to become part of the English language. Gorbachev's main interest was in making the economy and political system more efficient, but because he did it by imitating Western institutions, the opening up of Soviet society was the most visible result. Political prisoners were released, criticism of government activities was permitted in the media, and the Jewish "refuseniks" were finally allowed to emigrate to Israel. 1988 marked the 1,000-year anniversary of Russian Christianity, and the celebrations were not only broadcast on TV, but for the first time the Church was praised as a builder of moral character, a 180-degree turn from the official Marxist line that "religion is the opiate of the masses." Small privately-owned business sprang up all over the USSR. Boris Pasternak's classic novel Dr. Zhivago was published in its homeland for the first time, and a new wave of criticism for Stalin's career began.

It didn't take long before there were also dramatic changes abroad. Gorbachev met with US leaders every year; the first two meetings accomplished little, but at the third, in December 1987, a treaty eliminating intermediate-range nuclear missiles on both sides was signed. US-Soviet relations improved rapidly after that; Gorbachev signed the START I (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty) with Reagan's successor, George Bush, in 1991. In the Far East, China's Mao Zedong once predicted that the political differences between China and Russia were so great that they could not be resolved in 10,000 years, but less than thirty years after the Sino-Soviet split took place, Russia and China buried the hatchet; the revolutionary zeal that set them against each other in the early 60s is now gone from both countries, and now there is considerable commerce over China's long frontier.

Nine years of active Soviet support for the communist regime in Afghanistan vs. Moslem rebels killed 13,000 Soviet soldiers and produced millions of Afghan casualties and refugees, with the communists no closer to victory than when they started. Frustrated with this no-win situation, Gorbachev removed the Red Army in 1988-89, calling it "Brezhnev's war" to save face in what had become a Russian Vietnam. He continued to send aid to Kabul afterwards, but it wasn't enough; the satellite government collapsed in 1992.

In 1989 Gorbachev started using perestroika to reorganize the government along more efficient lines. Up to this point the Soviet Union had a bicameral legislature called the Supreme Soviet, which outwardly resembled the US Congress, but did not work the same way at all. Its 700+ members ran unopposed in rigged elections where they usually won with 99% of the vote; eventually Soviet elections became so predictable that the results would be printed on the back page of Pravda before the actual voting took place. And once elected, the Supreme Soviet was not expected to debate or veto any decisions made by the Politburo, but merely to act as a rubber stamp and approve what the Politburo had already decided to do.(25)

Gorbachev changed this by adding a third legislative body called the Congress of People's Deputies; its members would be freely elected, and from now on members of the other two bodies would be appointed, not elected, from the membership of the Congress. On March 26, 1989, the Congress of People's Deputies was elected in the first free election Russia had seen in 71 years. By Western standards it left much to be desired: in 384 of the 1500 races, Communist Party members (including Gorbachev) ran unopposed, and no opposition parties were permitted, though independent candidates were. Despite these hindrances, the results stunned everybody. The most talked-about candidate was Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin (1931-), a former construction engineer from Sverdlovsk in the Urals. Yeltsin had been brought to Moscow by Gorbachev and installed as first secretary of the Moscow City Party Committee in 1985, but Yeltsin quickly alienated his comrades for openly criticizing the privileges of the Party elite, leading to his dismissal in 1987. Now he ran a populist campaign to get his job back, and beat the Party favorite with an incredible 89% of the vote. Elsewhere the list of Communist losers was equally startling: the mayors of Moscow and Kiev, the top leadership of Lithuania and Belarus, Estonia's KGB chief, the admiral of the Soviet Pacific Fleet, and every communist candidate in Leningrad (including those who ran unopposed!).

But the Russians soon found out that glasnost is a two-edged sword; increasing the amount of personal freedom also means listening to bad news as well as good news. Gorbachev got a lesson in that when the Chernobyl nuclear reactor, just outside of Kiev, melted down in 1986, spewing a cloud of radiation over much of Europe. Whereas previous Soviet leaders would have kept such a disaster secret for as long as possible, Gorbachev was forced by concerned people in the West to come clean on what actually happened. Also, the new freedom of the press revealed how much of a mess the Soviet economy was really in. Not only does one have to wait years to buy a car, refrigerator, or washing machine, but shoppers have to wait in long lines for hours to buy staples like sausages, rice, coffee and candy. 36 million tons of grain had to be imported in 1988, and in the same year Gorbachev started cutting defense spending to keep the economy from collapsing completely. And the problems of poor transportation, worker alcoholism & absenteeism, and black marketing are as bad as ever. Even the average life expectancy has dropped, from 69 to 65 years, an accomplishment even Third World countries find hard to match in this age of modern medicine. In a 1988 speech Gorbachev admitted that, "Frankly speaking, comrades, we have underestimated the extent and gravity of the deformations." This was further emphasized during the first session of the Congress of People's Deputies; the main attempt was an unsuccessful last-ditch effort to keep Yeltsin from attending, and the rest of the session was spent debating the problems and how bad they really were. Without intending to do so, Gorbachev had triggered a revolution that would soon unseat him and the Communist regime.

The Union of Fewer and Fewer Republics

When glasnost and perestroika trickled into the satellite states of the Soviet Bloc, they triggered a wave of revolutionary activity. Unlike his predecessors, Gorbachev did little to stop the collapse of communism in the Soviet empire. At one point he joked that he was replacing the Brezhnev Doctrine with the "Sinatra Doctrine," meaning that he would let the satellite states do things their way (get it?). This also made the COMECON and the Warsaw Pact irrelevant; both of those international organizations dissolved in early 1991. For more about the revolutions that shook eastern Europe in 1989 and 1990, read Chapter 17 of my European history.

As the 1990s began, Gorbachev's reforms gained more momentum, until they escaped his control completely. Gorbachev responded to this by attempting to put the brakes on the movements he had once pushed enthusiastically. He hoped this would win back estranged hardliners, who began to charge him with deserting the Communist Party's cause. Instead, he alienated the reformers, who now looked to Boris Yeltsin, rather than Gorbachev, as the true leader of the "democrats." To shore up his centrist position and avoid another contest with Yeltsin, Gorbachev made the Supreme Soviet create a new office in March 1990, that of USSR president, and had himself selected to fill it.

Despite Gorbachev's efforts, the economy continued to deteriorate. His popularity was at an all-time high in the West (Time Magazine proclaimed him the "Man of the Decade" in 1990) but public approval slipped at home. New revelations of secret Soviet misbehaving continued to come out, the most distressing being that Chernobyl was not unique. News of hideous air pollution, massive oil and toxic waste spills, and misplanned irrigation (diversion of water from Central Asian rivers dried out the Aral Sea) came out everywhere, revealing that the Soviet Bloc was an environmentalist's nightmare.

On top of all this national consciousness arose among the ethnic minorities. Acts of violence broke out between the Moslem groups of Central Asia, some involving automatic weapons (in a totalitarian state!). A Georgian demonstration for independence in April 1989 was put down with tanks and poison gas, killing 21. In Baku, Azerbaijan, riots against neighboring Armenians and the communist regime were also met with Soviet troops, killing another 100 (January 1990). Despite this repression, the Red Army could only briefly keep the lid on a territorial dispute between earthquake-shaken Armenia and Moslem Azerbaijan; that became a full-scale war after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

The first republic to break away was Lithuania; early in 1990 it announced it would legalize opposition parties. Gorbachev opposed this at first, but after meeting Lithuania's president, Vytautas Landsbergis, he abruptly reversed his stand, declaring that the article in the 1977 constitution that makes the USSR a one-party state was no longer valid. That move got him through one political crisis, but in March Landsbergis gave him another by declaring outright independence from the USSR. Gorbachev slapped an economic blockade on Lithuania, and in three months the Lithuanians were forced to back down; Landsbergis stated that the declaration could not be withdrawn, but he was willing to negotiate for the time being. In the middle of the crisis Estonia and Latvia also declared independence, but they were more cautious about it, stating that their independence would not necessarily go into effect right away. One by one each of the other 12 republics passed resolutions, declaring that their own laws superseded those of the Soviet Union.

Even the largest and most powerful republic, Russia, joined this "state's rights" movement. In May Boris Yeltsin was elected parliamentary chairman; in June parliament declared that within the Russian republic, Russian laws now took precedence over Soviet ones. In effect, this meant that Russia was pulling out of the USSR. A Soviet Union without Russia could not last; all it had left were the institutions which had enforced its power in the past--the CPSU, army, interior ministry and the KGB--and now they were crumbling.

The 28th Communist Party Congress, held in the summer of 1990, proved to be the last. In the middle of it, Boris Yeltsin took the podium, declared his contempt for the Communist Party, announced his resignation from it, and stormed out. The car waiting for him outside suggested that Yeltsin planned the whole thing, but it was still great theater and an embarrassing defeat for Gorbachev. Before the year was over Yeltsin organized a Russian Communist Party, as a separate organization from the CPSU. Another bombshell burst in December when Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze warned that dictatorship was coming, resigned, and escaped to his native Georgia. The next time Shevardnadze appeared, in the spring of 1992, it would be as the leader of an independent Georgian republic.

1991 began with two new attempts by Gorbachev to stop the growing anarchy. First he filled vacant positions in the government with hardliners who strongly opposed any kind of reform. Then he sent troops into the boisterous Baltic republics. In Vilnius (the capital of Lithuania), Red Army soldiers seized the main press building and television tower, killing thirteen civilians when crowds formed to stop them. Five more demonstrators lost their lives in Riga when troops from the Soviet Interior Ministry attacked the Latvian Interior Ministry. The Kremlin got away with it at first because the rest of the world was paying attention to the Persian Gulf crisis, where Iraq had occupied Kuwait; in that sense the Hungarian uprising of 1956 was repeating itself. This time, however, there were voices within the Soviet Union Bloc to oppose this brutal behavior. Boris Yeltsin flew to Estonia and signed a resolution condemning the use of force in the Baltic States, while a quarter million Muscovites likewise demonstrated against using force.

In April Georgia declared itself completely independent of the USSR. Two months later Yeltsin won a majority of the vote to become first president of the Russian republic, which made his power roughly equal to Gorbachev's. In response, Gorbachev decided he needed to make a deal with the non-Russian republics, so he began to renegotiate the 1922 treaty that had formed the USSR. A draft Union Treaty was worked out with nine republics, including Russia, and Gorbachev went off to enjoy a long vacation in the Crimea. He planned to sign the agreement on August 20, 1991.

The signing ceremony never took place. While Gorbachev was away, three top Communist Party members formed the State Committee for the State of Emergency. When he was ready to come back, this group sent a delegation to demand his resignation. He told them to go back where they came from, and they refused to let Gorbachev leave his dacha.

On August 19, the Emergency Committee announced on Radio Moscow that Gorbachev would not be returning to Moscow because of illness, and for the sake of the USSR, they were taking over. Then they surrounded the Russian Parliament building (now called the "White House") with tanks, because that is where their chief enemy, Russian President Yeltsin, was currently staying. Yeltsin, however, was able to keep in contact with the outside world via telephone and fax machine.

What happened next was a fine example of a bungled revolution. The Emergency Committee apparently assumed that ordinary people would be glad to see law and order return, and they would either support the hardliners or get out of the way. They did neither. A flood of demonstrators surrounded the tanks, climbed on them, and criticized the crews for going against the wishes of the people; the bewildered Red Army troops wondered what they were doing there, and ten tanks turned their guns outward, showing they would defend the White House, not the Emergency Committee. A revolution succeeds or fails when the armed forces choose which side they will support, so when the troops went over to the demonstrators, a victory for democracy was in the bag.

The coup leaders--Boris Pugo, Gennady Yanaev and Oleg Baklanov--realized their support was weak, so they appeared in a press conference on TV. They looked very nervous and unconvincing; Yanaev was even drunk. After that came an armed clash in which three demonstrators were killed. When that failed to bring the whole Red Army on their side, the plotters fled to the airport, and escaped to the Crimea. Gorbachev refused to meet with them, and Boris Pugo shot himself a day later; the rest were arrested.

Now free, Gorbachev returned to Moscow on August 22. There he showed how out of touch he had become, by declaring that he still believed in the ideas and goals of the Communist Party, though it had just tried to get rid of him. After that few people took him seriously. One by one the Soviet Union's republics declared independence, or in the case of the Baltic States, reaffirmed their declaration. In September the Congress of People's Deputies voted itself out of existence. A wave of name changes swept across the cities of the USSR, where Soviet-era names were replaced by those of Tsarist times.(26)

On December 8, Yeltsin met in Minsk with the presidents of Ukraine and Belarus; they announced they would replace the USSR with a confederation, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). During the next two weeks eight other republics joined them, leaving out only the Baltic states and civil war-wracked Georgia. This left Gorbachev a tenant in a country he no longer ruled. All he could do was resign from his last post, that of USSR president, and he did so on December 25, 1991. The Soviet Union was no more.

This is the End of Chapter 5.

FOOTNOTES

17. In 2003, on the fiftieth anniversary of Stalin's death, two historians, one American and one Russian, released a book on the Doctor's Plot, entitled Stalin's Last Crime. This book proposed that Stalin was preparing for war with the United States, and he was only stopped when somebody in the Poliburo, most likely Lavrenti Beria, poisoned him. If there is any truth to this, the much-reviled secret police chief (shown below) may have prevented World War III.

18. An attempt to reconcile Soviet-Yugoslav differences with a summit meeting in Belgrade got nowhere the year before.

19. The name changes were as follows: Stalingrad = Volgograd, Stalino = Donetsk, Stalinogorsk = Novomoskovsk, Stalinabad = Dushanbe, Stalinsk = Novokuznetsk. A 1961 political cartoon had a Red Army veteran tell his son, "Stop asking me for stories about Stalingrad. There is no more Stalingrad."

20. All three of the conspirators lived to a ripe old age, because Khrushchev, unlike Stalin, did not believe in killing all his enemies. Vyacheslav Molotov was first appointed ambassador to Mongolia, and then became the Soviet representative to the International Atomic Energy Agency; since both jobs sent him abroad, they can be seen as a form of banishment. Then in 1961 Khrushchev expelled both him and Kaganovich from the Communist Party completely. Molotov enjoyed a partial rehabilitation in the 1970s and 80s, but he remained an unrepentant Stalinist until his death in 1986.

Georgy Malenkov was exiled to Kazakhstan, where he became manager of a hydroelectric plant in Ust'-Kamenogorsk. Late in life he became a Christian, a remarkable transformation for a communist, and a minor Orthodox clergyman, serving as a reader and a choir singer. When he died in 1988 he received a Christian funeral.

After his firing, Lazar Kaganovich became director of a small potash works in the Urals, until his 1961 expulsion from the Party; then he lived on a pension in Moscow for the next thirty years. The last of the old-school Bolsheviks, he died at the age of 97, on June 25, 1991, five months to the day before the Soviet Union ended as well.

21. "Revisionism" means backsliding from communism to capitalism; it is the dirtiest word in the Marxist vocabulary.

22. Despite all the promises and efforts, Marxism could never create a human being totally free from greed. This was most evident on the Soviet collective farms, where farmers had little motivation to work since the profits went to the state rather than to themselves. Even Stalin had to give the farmers a concession in the form of private plots of land, where they could keep or sell the crops and/or livestock raised on them. Of course the farmers gave their best seed, fertilizer, and attention to the private plots, but Khrushchev and his successors never found a way to eliminate the plots without causing an economic catastrophe, because 30% of the country's food was being produced on the private 5% of the farmland! Neither were they willing to do away with the inefficient collective farms, because collective work of any kind is a sacred cow that communists and socialists refuse to give up.

23. In the late 1960s and 70s the USA gained the lead in space exploration by putting men on the moon, but America's government and people have shown less willingness to support their space program. The Soviet space program suffered many mishaps, some of them stupid by Western standards, but eventually Russian determination allowed the USSR to catch up again, in a hare-and-tortoise fashion.

24. Because Russia gets notoriously cold in the winter, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher let an aide persuade her to stop at a shoe store and get some fleece-lined boots, before going to Andropov's funeral. She complained about spending money on that purchase until she shook hands with Chernenko, and then, realizing that she was likely to be making a second trip soon, said this about the boots: "They were a prudent long-term investment." The American vice president, George H. W. Bush, had similar sentiments; after the funeral, he said goodbye to the US Embassy staff by telling them, "Next year, same time, same place."

25. A March 1966 National Geographic article called this "Government by Da (Yes)."

26. To give a few examples, Leningrad became St. Petersburg again, Sverdlovsk became Yekaterinburg, Kuibyshev became Samarra, Ul'yanovsk became Simbirsk, Kirov became Nizhniy Novgorod and Kalinin became Tver. At the time, the Russians told a joke to illustrate how many name changes they had to deal with. The joke was about an old man who emigrated from Russia in 1917, and came back in 1991. Here are the questions an immigration official asked him, and the answers he gave:

Q: "Where were you born?" A: "St. Petersburg."

Q: "From which port did you leave Russia?" A: "Petrograd."

Q. "Which city was your port of entry?" A: "Leningrad."

Q. "Where do you plan to stay?" A: "St. Petersburg."

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Russia

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|