| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 14: WORLD WAR II

1939 to 1945

This chapter covers the following topics:

The Blitzkrieg Unleashed

Though he had taken over Austria and Czechoslovakia without firing a shot, Adolf Hitler could not hide his intentions forever, and it was easy to guess who his next victim was going to be. Poland had gained more German territory from the Versailles Treaty than any other country; the existence of Danzig and of the Polish Corridor that separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany were standing affronts to German nationalism. When Hitler opened his propaganda campaign against these "injustices," British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, in a joint declaration with the French, finally drew the line: if Germany invaded Poland, Britain and France would declare war. However, both he and the Poles shrank from asking the Soviet Union to join in this anti-Nazi alliance; the Poles because they knew exactly what the Soviets would ask for in return (the territory Poland had annexed in 1920)(1), Chamberlain because he couldn't bring himself to associate with Bolsheviks. Consequently the Anglo-French threat wasn't very impressive. The Germans would think twice about starting a war if it meant fighting on two fronts, because many felt that was what killed them in World War I, but without the USSR there wouldn't be an eastern front for long.

By this time, Hitler had set a date for the invasion of Poland. However, the Nazi leader did sense that the upcoming war would be a lot easier to handle if the Soviets stayed out of it, so he made an offer to Stalin: he would let Stalin have half of Poland if the Soviet Union did not get involved in the next war. If Chamberlain had been blind for too long about Hitler's intentions, it seems even stranger that Stalin was blind for a time as well. He appears to have regarded the Allied and German diplomatic missions to Moscow in the 1930s as nothing more than the bids of rival suitors seeking his favor. In the end, he found the German offer more to his liking, because it gave him both time and a chance to grab some land. One week after German and Soviet ministers signed the papers dividing up Poland between them, the German army crossed the Polish frontier (September 1, 1939). Two days later Chamberlain reluctantly declared war, and the world was in flames again.

Hitler knew from experience that German soldiers did best when they moved fast, avoiding bloody slugging matches like the ones that characterized World War I. But how could they overcome the immense firepower of automatic weapons in the hands of a defending force? During the last war, the tank was the best solution, so the generals wanted more tanks, and most planned on using them the same way they had done in 1918: advancing with the infantry, taking out points of resistance that were too tough for the foot soldiers to handle. However, one German general, Heinz Guderian, had a different idea. During the 1920s he wrote several papers that proposed motorizing and armoring all the elements of a normal division (infantry, artillery and engineers) so that they could work alongside tanks without slowing them down. The end result, a special panzer (armored) division, turned the tank concept around; now infantry supported the tanks, rather than the other way around. Panzer divisions would be very expensive--to pay for them, the rest of the German army would have to use horse-drawn transport for years to come--but Guderian believed that with half a dozen of them he could make war a matter of movement again.

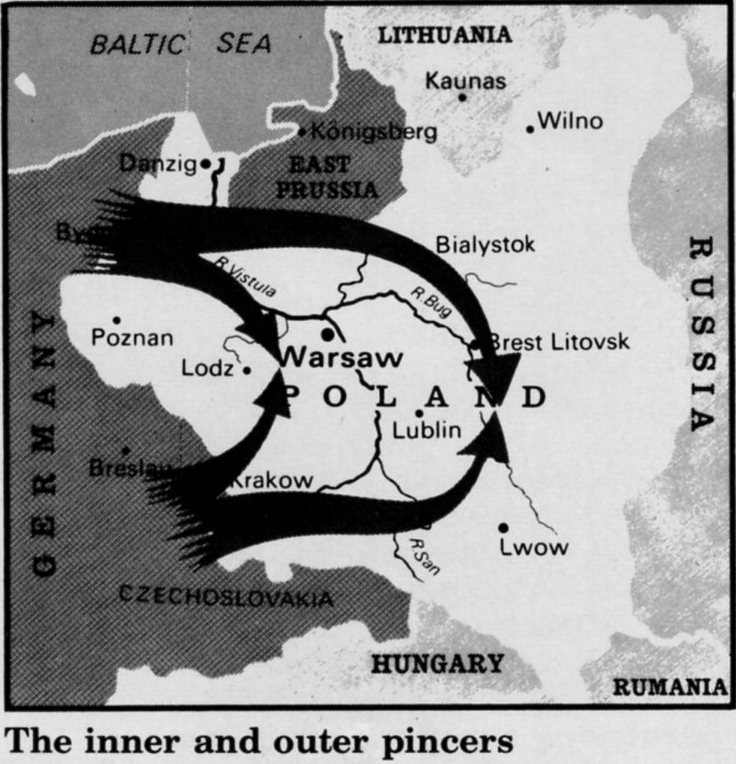

In 1933, Guderian showed Hitler the first experimental panzer unit. "That's what I want," exclaimed the excited Führer, and he gave his full support to Guderian's panzer-building program. As a result, all six of the armored divisions Guderian had requested were ready in time for the invasion of Poland. One division was based in Pomerania, and one was based in East Prussia, forming Army Group North, while four divisions formed Army Group South in Silesia. The Pomeranian and three of the Silesian divisions were under orders to converge on Warsaw as fast as possible, before the French and British could counterattack on Germany's western frontier (see Chapter 15, footnote #17). The East Prussian and the fourth Silesian division would go for Brest-Litovsk, a town 120 miles east of Warsaw.

The insistence on speed made the campaign against Poland a model operation. The Polish air force was wiped out on the first day, giving the Luftwaffe (German air force) full command of the air. Then the Luftwaffe continued to go ahead of the panzers, striking at military targets the ground forces couldn't reach, or spreading terror by attacking civilian-populated areas. Within five days Army Group North overran the Polish Corridor and Danzig; one of the divisions from Army Group South reached the gates of the Polish capital on September 9. Poland's armies, spread evenly along the frontier, found themselves first bypassed, then surrounded as infantry poured through the breaches the panzers had made. The only counterattack the Poles managed, near the Bzura River, failed to keep the Germans from encircling, bombing and shelling Warsaw into submission. The world had its first taste of Blitzkrieg, "lightning war."

A German Stuka (dive bomber) in action.

While the world concentrated its attention on the siege of Warsaw, the second pincer movement drove on Brest-Litovsk. This was General Guderian's idea; he had the second pincer movement put into his orders because he thought the panzers could take more than just Warsaw. Personally leading the East Prussian division, he reached Brest-Litovsk on September 14. Three days later he made contact with the other division sent east, and central Poland, like western Poland, was now isolated. The Poles tried to make a stand in the southeast, but any chance of that succeeding was ruined on September 17, when the Soviet Union moved in to take the part of Poland that Germany hadn't conquered yet. All the Poles could do after that was evacuate as many soldiers as possible into neutral Romania. Five weeks after the invasion started, the last Polish resistance ended.(2)

German and Soviet army officers meet at Brest-Litovsk, 1939. On September 22 they held a joint military parade, to celebrate their victory against Poland.

Hitler Strikes North

Once Poland was divided up, Stalin began to implement the other parts of the non-aggression pact. The Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) had been independent of Russian rule since 1918; now he brought them back into Russia's "sphere of influence." By the end of the year he had Soviet troops in all three republics; the following year saw them annexed into the Soviet Union. Soviet troops also entered Finland in November, but not with Finnish permission. The Russo-Finnish border was too close to Leningrad for comfort, and when the Finns refused to shift the border west, Stalin ordered the Red Army to do it, after accusing the Finns of attacking him first. The first invasions took place in sub-zero weather and were defeated by valiant Finnish troops, who counterattacked on skis. Not until February 1940 did enough Red army soldiers arrive on the scene to bludgeon a path forward to the line Stalin wanted.

Stalin's pact with Hitler and his ruthless behavior toward the states on the USSR's border aroused great fury in the west; during the Winter War, anti-Soviet feeling ran so high that Britain and France considered sending an expeditionary force to help the Finns. An Allied landing at Petsamo, Finland's Arctic port, was out of the question at this time of the year, and with the Baltic frozen as well, the only way an army from Western Europe could get to Finland was by going across neutral Norway and Sweden. The Norwegians and Swedes refused to let foreign armies pass through their territories, but the fact that the expedition had been suggested at all started people thinking. Three-quarters of Germany's iron ore came from northern Sweden, and rather than deal with ice in the Baltic, the Swedes exported the iron by shipping it on a railroad that ran from the town of Luleå to the Norwegian port of Narvik. If the Allies could get control of Narvik, Germany would lose a vital resource. Both sides saw this at the same time, but as usual Hitler acted while Chamberlain was still thinking about it.

The Germans began their northern campaign with amphibious and paratrooper landings against both Denmark and Norway on April 9, 1940. The Danes were immediately overrun; their forces were too small to resist the invasion for even one day. The German attacks on Norway took Oslo, Trondheim and Narvik, the three most important cities, on the same day. However, one of the German objectives was to capture the Norwegian king, Haakon VII, and the Norwegians kept that from happening. When a German fleet led by a heavy cruiser, the Blücher, approached Oslo, a coastal fortress fired on the ships, and a torpedo shot from the fort sank the Blücher. This ship carried most of the troops, Gestapo agents and administrators that were supposed to occupy the Norwegian capital, and with its loss, the other ships retreated. While the Germans decided what to do next, the royal family, Cabinet, and most of the Parliament used the time gained to escape from Oslo by train.

At first they went to Elverum. Hitler wanted Vidkun Quisling, the leader of Norway's small Fascist Party, to run Norway for him, so the German minister to Norway demanded that the king appoint Quisling as the new prime minister. The king refused, declaring that such an appointment had to be approved by his government, and he told the Cabinet he would abdicate if they said yes to Quisling. Because the king was much loved by his subjects, the government unanimously voted no. Then the royal family and Cabinet moved on to Nybergsund, a small town near the Swedish border, but a raid by the Luftwaffe severely damaged the town on April 11, showing that they couldn't stay here. Sweden let it be known it would "detain and incarcerate" the king if he crossed the border, so the king and those with him had to flee northward.

The Germans could not use Quisling now, because no Norwegian would accept him as the country's rightful leader. As a result, Norway was managed by the army, the Wehrmacht, for a while. They did not put Quisling in charge until 1942; by then, loyalty to the German cause was more important than legitimacy. Because he should have been on the same side as his people, today we use the name "Quisling" to mean a traitor.

Fortunately for the king and his entourage, the British came to the rescue, by landing an Allied expeditionary force at three points; two of the landings were a hundred miles northeast and southwest of Trondheim respectively, while the third was near Narvik. However, the German force advancing north from Oslo was too strong, so the forces around Trondheim had to be evacuated at the beginning of May. The Allies in the north did better; a combined force of Norwegian, French, British and Polish troops recovered Narvik on May 28. Here the British were confident that their command of the sea would give them the edge in this campaign, but that thinking was out of date. As in Poland, command of the air was more important, and the Germans already had the airfields. Moreover, by this time the Germans had invaded the Low Countries and France (see the next section), meaning the British and French needed to go home and defend their homelands. Consequently they prepared to evacuate Narvik almost as soon as they arrived. On June 8 and 9 the Allies departed on their ships, leaving all of Norway to the Germans. King Haakon and his government went with them, forming a Norwegian government-in-exile in England, to go with those set up for Ethiopia and Poland.

The Fall of the West

For eight months after war was declared, all was quiet on the Western Front. To most people this didn't make sense. Western journalists, who had been expecting something like 1914, began writing about the "Phony War," and the Germans compared the Blitzkrieg in the east with the Sitzkrieg ("sit-down war") in the west. Indeed, it was because of this lack of activity that the Allies had thought about intervening in Finland and Norway. The Germans were busy moving troops to their western frontier as fast as they could, while the Allies, remembering how every offensive in the last war had produced heavy casualties, refused to strike first. On September 7, 1939, while the bulk of the German army was fighting in Poland, the French made a half-hearted invasion of the Saar district, across the Rhine; they halted at the Siegfried Line, changed their minds, and withdrew by October. After that, the French simply waited behind the Maginot Line, confident that it would defend them against anything.

Initally the Germans were going to repeat the Schlieffen Plan, marching into the Low Countries first and then wheeling left to enter France. But then in January 1940, a German plane carrying a complete copy of the orders made a forced landing in Belgium, and since the Belgians now had the orders, the High Command had to come up with a new strategy. Of the various ideas proposed, the best one, proposed by General Erich von Manstein, put the main blow in the center, through Luxembourg and the Ardennes forest. By the spring of 1940, the German army had ten panzer divisions, and General Guderian would use three of those divisions to make the crucial breakthrough. On the other side, the Allies had three (mostly French) armored divisions, but they kept them in reserve, meaning that by the time Allied tanks got to the front line, the panzers would have done their work.

The German invasion of the West began on May 10, and went like clockwork. Neville Chamberlain resigned in disgrace, now that everything he had done to prevent war had failed; he was succeeded by his rival Winston Churchill.(3) In the Low Countries, the Allies went to the rescue of the Dutch, who were invaded first, and didn't pay much attention to anything else. A daring raid by German paratroopers captured Eben-Emael, the strongest Belgian fort, opening the way for the invasion of Belgium. Again the Luftwaffe quickly won control of the air, and it mercilessly bombed the city of Rotterdam (May 14). One day later Holland surrendered--and Guderian struck. His panzers crashed through the supposedly impenetrable Ardennes, crossed the Meuse River at Sedan, and raced west. Five days later, on May 20, they reached the Channel. The Allied front had been split in two at its weakest point; the Belgian and British armies were cut off from the French. On May 28, Belgium capitulated, leaving the British Expeditionary Force surrounded in the northernmost corner of France.

Hitler and General Gerd Von Rundstedt, Guderian's commanding officer, were surprised by how swiftly the panzers had demolished the French army. During the last week of May they halted their advance, fearing that they were now overextended. For the British this was the miracle they needed, and they used the time gained to bring every boat available to the one French port remaining to them, Dunkirk, from which they evacuated their men to safety in England. At first they thought they would only have two days to undertake the rescue, but it lasted nine days, and they saved 338,226 men, which included some of their French and Belgian companions. By the time the Germans overran Dunkirk, only a holding force of 40,000 French remained.

In the long run, Hitler's decision to concentrate on finishing off the French was a critical mistake. Like (spoiler alert!) his decisions to attack the USSR and declare war on the United States, it may have decided who would win the war in the end. Because the soldiers trapped at Dunkirk had time to escape, the British army survived, and those soldiers would fight the Germans again, in North Africa, Italy, and on D-Day. It is also possible that if those soldiers had not survived, Churchill would have been forced to negotiate for peace, and his term as prime minister would have ended, just weeks after it began.

Anyway, on the same day that the siege of Dunkirk ended (June 5), the Germans began the second phase of the campaign to conquer France. General Hoth took one Panzer corps along the coast to capture Normandy and Brittany, while Kleist and Guderian led the others directly south. For the French it was a speedy doom. General Maxime Weygand had sixty-six divisions hastily dig in along the Somme and Aisne rivers, but this only held the Germans briefly. The French commander of the Maginot Line had refused to release any of his men to defend the heart of France, thinking that the main German attack was still to come at the Maginot Line itself; now he found that his guns were pointing the wrong way. Paris fell on June 14; on June 22 the French government, recognizing the military situation as hopeless, surrendered to the Germans.(4)

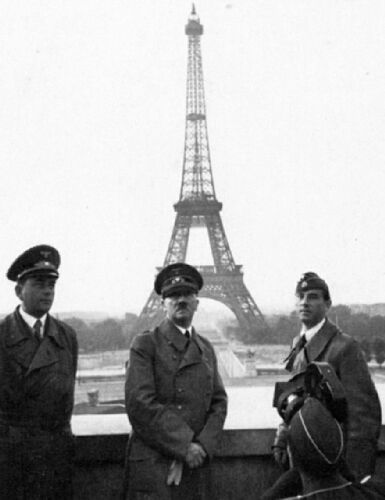

Hitler goes sightseeing in Paris, after the fall of France. He spent an hour in Napoleon's tomb, because he regarded Napoleon as a predecessor.

One final point worth noting is Mussolini's formal entry into the war. Finally convinced that Germany was going to win, he declared war on France and Britain on June 10. Unfortunately for him, Italy's military performance hadn't improved much since the last war, and the French had also fortified the Franco-Italian frontier, with a defensive barrier called the Alpine Line. Italy's thirty-two divisions, opposed by six French ones, succeeded in getting yards (not miles) past the border, in the twelve days before the French surrendered to Hitler. Winston Churchill knew that Italy was no asset; before World War II began, he was informed that Italy was going to be on Germany's side in the next war, and he reportedly said, "That seems only fair, we had them last time!"

The Battle of Britain and the Campaigns of 1941

With France defeated, Hitler was ready to wind down the war in the west; his main interest shifted to Russia. Because the English were Aryans like the Germans, he didn't really want to fight them, and figured if he offered peace, they would either join him or agree to a treaty. Many folks in Britain, including the ex-king Edward VIII and David Lloyd George, the prime minister during the last war, also felt that after the French collapse, the war was as good as over. However, it was the current prime minister's opinion that mattered, and in Churchill, the Allies finally had a leader who wouldn't knuckle under to Hitler's threats. When the prime minister spurned the Führer's overtures, Hitler had to plan for an invasion of the British Isles. This wasn't a simple proposition; the British not only had their famous navy patrolling the Channel, they also had--and this was the one military preparation they did exactly right--fighter squadrons protecting the skies, guided by the new invention of radar. In the Battle of Britain Hitler tried repeatedly to shoot down the RAF (Royal Air Force), but he failed to win the air superiority he needed; summer became fall, and "Operation Sea Lion," the invasion of Britain, had to be indefinitely postponed. The Nazi leader shrugged off his first defeat as irrelevant; to try to break the spirit of the British he sent nightly bombing raids against the cities of England ("the Blitz") until May 1941. Meanwhile plans were made for "Operation Barbarossa," the invasion of Russia. Hitler thought that Russia wouldn't be much more of an opponent than France had been, and once he had eliminated the "Jewish Bolshevik" the British would listen to reason and make peace. And if London still didn't agree, he would be in an even stronger position to deal the death blow to Britain.(5)

St. Paul's Cathedral survived all German attacks on London, though the buildings around it went up in flames.

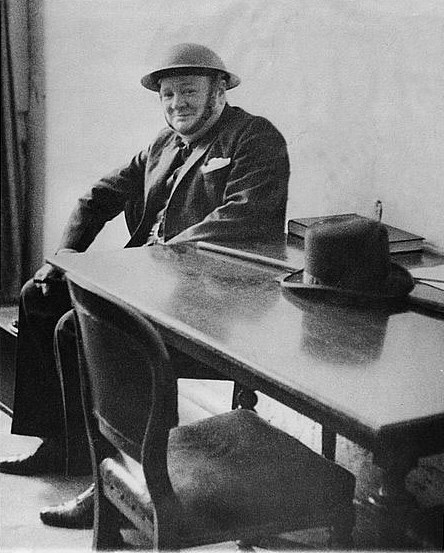

And here Winston Churchill wears a helmet during an air raid.

Meanwhile Mussolini made his own play for the limelight. In August he occupied British Somaliland and in September he invaded Egypt from Libya. Those activities were all that the Italians could handle, but when the campaign against Egypt began to go badly, Mussolini responded by opening up additional fronts. He proposed simultaneous invasions of Switzerland, Yugoslavia and Greece, until his commanders warned that he did not have enough troops for all three, so he decided to go after Greece only. Then came the news that Hitler had persuaded Romania to join the Axis. Mussolini blurted to Count Ciano, his son-in-law and foreign minister, "Hitler always faces me with a fait accompli. This time I am going to pay him back in his own coin. He will find out from the newspapers that I have occupied Greece. In this way the equilibrium will be reestablished. I shall send in my resignation as an Italian if anyone objects to our fighting the Greeks."

Unfortunately for him the Greeks objected. Since 1936 Greece had been under its own fascist dictator, Ioannis Metaxas. Mussolini may have thought that he could make Metaxas become the next Axis member, but most Greeks preferred France and Britain, and because of Greece's preoccupation with the sea, they had a strong respect for the Royal Navy. According to a popular legend, on October 28, 1940, an Italian diplomat presented Metaxas with an ultimatum demanding that he allow Italian forces to occupy strategic sites in Greece, and Metaxas responded with one word, "Ohi!" meaning "No!" in Greek. Because of that event, in modern Greece October 28 is a national holiday, "Ohi Day." The Italians launched a surprise attack from Albania, Metaxas successfully mobilized his subjects to resist, and within a matter of days the Italians were stopped and turned back, by a far smaller army using obsolete equipment. Two weeks after the invasion began, Mussolini sacked the general in charge, Sebastiano Visconti Prasca, but his replacement, Ubaldo Soddu, was worse. Soddu was a career officer who was good at office work and networking (before the war he attended so many parties that he had quite a few friends from both Germany and Britain), but when it came to strategy and tactics, he had no talent whatsoever. Nor did that interest him much; he once told his staff, "When you have a fine plate of pasta guaranteed for life and a little music, you don't need anything more." While the Greeks began a counterattack that captured a third of Albania by early 1941, Soddu spent much of his time composing musical scores for movie soundtracks. In Africa the British also turned the tables on the invaders, conquering half of Libya and all of Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somaliland.

Hitler, who had wanted to keep things quiet elsewhere while he got the Russian campaign ready, was furious, but he felt he had to bail out his fellow dictator. Two divisions sent to North Africa restored the situation in Libya and became the core units for the soon-to-be-famous Afrika Korps. In March the Yugoslav government gave in to German pressure and agreed to join the Axis, thereby allowing the Germans to pass through their country on the way to Greece. This was too much for the Yugoslav people, though, and a few days later a coup d'etat brought in a new government dedicated to keeping Yugoslavia neutral.

Germany retaliated quickly and without mercy. Five panzer divisions and the cooperation of his Balkan partners (Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania) made it possible for Hitler to crush Yugoslavia in just ten days. The panzers moved on, and by the end of April they took care of mainland Greece, too. Then came a whirlwind paratroop assault on Crete, which forced a sudden withdrawal of the forces Britain had dispatched to the area.(6) But all this forced Hitler to postpone the invasion of Russia for five weeks. Later on he wished that the Italians had never gotten involved in the war--at least on his side. "My unshakable friendship for Italy and the Duce may well be held to be an error on my part," he wrote. "It is in fact quite obvious that our Italian alliance has been of more service to our enemies than to ourselves."

With the wisdom of hindsight, one could point out that the delay of Operation Barbarossa caused by the Balkan campaign was quite unnecessary. In June 1941 Hitler had more than 150 divisions massed along the Russian border, compared with just seven in Yugoslavia and Greece. But those five weeks may well have made all the difference. By the time the panzers reached the gates of Moscow in the fall of 1941, the troops were fought out, ill-prepared for the Russian winter (they didn't bring cold weather clothing because they had expected victory by the end of summer), and unable to go any farther. As Hitler began to deal with the consequences of having made the same mistake as Napoleon and Sweden's King Charles XII, Stalin found that his best generals were the ones that nature had provided in the past: first "General Mud," and later "Generals January and February."(7)

Finally one other event of 1941 is important enough to mention here, though it took place on the other side of the world. On December 7, the Japanese launched a pre-emptive air strike on the American Pacific Fleet as it was anchored at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. This caused the United States to declare war on Japan, and when Hitler heard the news, he was so delighted that he proclaimed the Japanese honorary Aryans and declared war on the USA himself. With both Britain and Russia still fighting, it was the height of folly. Maybe America was going to come against Germany sooner or later, but why hasten the day?(8) What conceivable advantage could be gained, even of the most temporary sort? There seems to be no answer except to say that Hitler was acting petulant and short-sighted. But then Hitler never did calculate the long-term odds of anything. Maybe that is why he was so successful--in the short term.

Under the Swastika

Hitler had predicted that the Third Reich would last for a thousand years, and as it turned out, he was only 988 years off. As a political structure, what did this mean for Europe? Germany was much larger, for a start. Besides Austria and Bohemia-Moravia, the new German provinces were territories that had previously belonged to Poland (Bialystok and the entire northwest), Luxembourg (the whole country), France (Alsace-Lorraine) and Yugoslavia (northern Slovenia). Then came the states ruled by either Nazi officials or locals appointed by the Nazis: Slovakia, Poland (what was left of it, Galicia and the area around Warsaw), Serbia, Croatia (which included Bosnia-Herzegovina), the Ukraine and Ostland (a future Baltic German state, made by uniting Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Belarus). The next rank down was for those states under direct Nazi military occupation: Holland, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, northern and western France, Russia east of the Ukraine and Ostland, Greece and the Serbian part of Banat.(9) Finally there were the other members of the Axis, those sovereign states that had chosen to hitch their wagons to Hitler's star: Italy, Vichy France, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania and Finland.(10)

Those in the last group were rewarded for their support. Mussolini got those bits of the Balkans he had always wanted: southern Slovenia, Dalmatia and the Ionian Islands, additions to his Albanian province (Kosovo and part of Greece) and Montenegro as a new one. The Hungarians got Transylvania and half of Banat; the Bulgarians got back western Thrace, the southern Dobruja, and added the Yugoslavian part of Macedonia. Hungary and Bulgaria's gains were made partially at Romania's expense, and because Hitler had also let Stalin annex Bessarabia and northern Bukovina in 1940, the Romanians were the least happy members of the Axis. However, after the break with Russia, Hitler gave them back Bessarabia and northern Bukovina and threw in the slice of the Ukraine between the Dniester and the Southern Bug Rivers (Transnistria) as well. As for the Finns, they were once again in possession of the territory they had lost in 1940, though in the war against Russia they did not take anything beyond that.

40 percent of France and the overseas French colonies were ruled from the provincial town of Vichy, under a dictatorship managed by the ancient Marshal Petain, and a despicable prime minister named Pierre Laval. Petain pleaded that he was not a traitor, and that only political necessity made him support the Axis. Though this was true, at times it seemed that he pleaded too often and too easily; still, at this stage in the war, most Frenchmen gave him their support. When the Allies captured French North Africa in November 1942, Hitler dispensed with the Vichy charade. Savoy, Provence and Corsica were given to Italy, while the rest of France was brought under German occupation.

One part of France which Hitler never got his hands on was the French fleet. In 1940, after the fall of France, Britain staged a raid on the part of the French fleet stationed in Algeria, thereby making sure those ships would not be used against them. Most of the French fleet, however, was kept at the Mediterranean port of Toulon for the next two years. Then when the Germans occupied southern France, French sailors scuttled the ships, by settling off demolition charges and opening sea valves, before the Germans could take them away. The vessels sunk here included three battleships, seven cruisers, fifteen destroyers, thirteen torpedo boats, six sloops, twelve submarines, nine patrol boats, nineteen auxiliary ships, one school ship, and twenty-eight tugs, plus four cranes. Overall the French had few victories in this war, and one of them was against their own fleet!

One French general, Charles de Gaulle, escaped to England in 1940 and tried to persuade French citizens to continue the struggle against Germany. But while Churchill and Roosevelt recognized him as the leader of the "Free French" without hesitation, he got little response from the French themselves. The British hoped that he could at least bring Syria over to their side, but instead they had to conquer it for him and install a Free French governor. Not until late 1942 did de Gaulle have enough popular support to help the Allies constructively (in the liberation of French North Africa).

If de Gaulle's initial performance was disappointing to the Allies, Spain's Francisco Franco was a greater disappointment to the Axis. He was in debt to the Germans for their help in the Spanish Civil War, but he kept Spain neutral for all of World War II. He wouldn't declare war on the Allies because he said that Spain was too poor to afford another war, and wouldn't even let the Germans pass though Spanish territory to take the British base at Gibraltar. All he could do was contribute a regiment of Spanish volunteers, the so-called Blue Division, which joined the Wehrmacht on the Russian front.

Besides Spain, the other neutral nations were Ireland, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and Vatican City. Ireland refused to join any alliance that included Britain, despite its Commonwealth status, because Northern Ireland was still in British hands. However, Eamon de Valera, who served as prime minister from 1932 to 1948, faced a threat from a local fascist movement, the "Blue Shirts," in addition to the Irish Republican Army, so he gave the Allies better treatment. American and British pilots who crashlanded in Eire were given food and safe transport to Northern Ireland, along with their planes if they could be repaired, while German pilots were interned (the accidental German bombing of Dublin in 1941 didn't help German-Irish relations, either). Portugal signed a friendship pact with Spain right after the Spanish Civil War, and allowed the Allies to use Portuguese air bases from 1943 onward, but otherwise refused to commit itself to either side. Turkey stayed out until early 1945, and only declared war on Germany so that she would qualify for charter membership in the new United Nations. Sweden sold its iron ore to Germany, as we noted earlier, while Switzerland's banks and factories did business with the Third Reich; after the war the Swedes and Swiss claimed this was necessary to prevent an outright German invasion. In the 1990s it was discovered that Swiss bank accounts still held money the Nazis had looted from their Jewish victims, leading some to wonder how "neutral" Switzerland really was during the war.

The most controversial of the neutrals was the Vatican. We now know, from documents just made public in 2013, that Pope Pius XII worked to save several thousand Jews from the Nazis, either by giving them travel visas identifying them as Catholics, so they could leave Germany or Hungary, or by hiding them in Italian convents and monasteries. However, he also did very little to hinder Axis activities, going so far as allowing one Axis state, Croatia, to have an office in the Vatican. It has been said the pope did this because Hitler would have persecuted both Catholics and "Catholics" if he came out openly against the Axis, but he still refused to denounce Axis behavior after the war, when it was no longer dangerous to speak out. In today's information society, words can speak louder than actions, and the pope's silence led to the publication of a biography about him in 1999, entitled "Hitler's Pope."

Surprisingly, the Nazi regime did little to regulate Germany's economy, when one considers how much it controlled the rest of German society. Perhaps Hitler and his associates felt that economic prosperity was the real reason why the German people supported them, rather than their propaganda machine and the Nuremberg rallies. While the Allied nations accepted rationing, martial law, etc., almost immediately after they entered the war, ordinary Germans enjoyed peacetime standards of living until 1941; luxury goods that were no longer available in Britain or the USSR, and scarce in the United States, were still common in Germany. When shortages did appear, the Germans got by with imports from their conquests (e.g., French perfumes, Dutch cheeses, Norwegian furs, etc.), and with ersatz (substitute) products invented by their scientists. Equally astonishing, German factories worked only one shift a day until 1943, and they did not hire women to fill the vacancies when their workers went off to war. There was no Axis equivalent of "Rosie the Riveter," because that went against Nazi ideology; propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels declared that a woman's most important tasks were "being beautiful and bringing children into the world."(11)

The "Final Solution"

Undoubtedly the most insane aspect of the Third Reich was its hatred of Jews. Like other European Jews, the Jews of Germany were loyal subjects who thought of themselves as Germans first; many had served in the army during the Franco-Prussian War and World War I. Anti-Semitism had long been a fact of life in Europe, but except for the pogroms in Russia, it now only showed up in isolated incidents (the most notorious being the Dreyfus case of the 1890s), rather than the wholesale expulsions and massacres of the past. Many Jews felt that if they looked like Germans, dressed like Germans, acted like Germans, and spoke the German language instead of Yiddish, they would find acceptance as Germans. However, tyrants find it useful to have a scapegoat around; even before he left his native Austria, Hitler was reading anti-Semitic literature, and jealous of Vienna's Jewish community. Soon he was blaming a worldwide Jewish conspiracy for every problem Germany had.

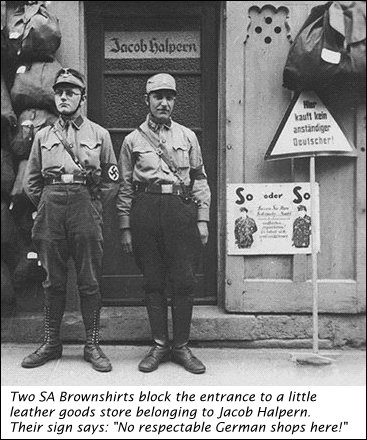

Hitler had announced his anti-Jewish feelings to the world when he wrote Mein Kampf, and he started putting them into action once he could rule without opposition. 1934 saw the creation of the first concentration camp, Dachau, and it served as the model for those built afterwards. The camps held anybody the Nazis didn't like, but as time went on Jews became the largest group incarcerated. In 1935 the infamous Nuremberg Laws liquidated Jewish businesses, barred Jews from working as doctors or lawyers, and made it illegal for them to marry Gentiles. In schools the teachers taught courage in battle, obedience, and the superiority of the "Aryan race," while books considered offensive were burned in bonfires. Individual Jews like Albert Einstein began leaving Germany for western Europe and America; for those who decided to wait it out, this was only the beginning.

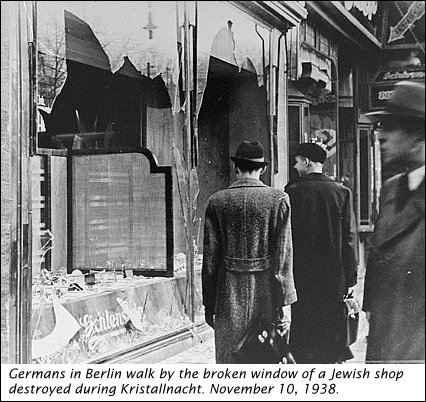

At first it seems that the main goal was to humiliate and impoverish the Jews; some even came out of the concentration camps, broken in spirit, but still alive. The second stage of the persecution began with Kristallnacht ("The Night of Broken Glass"), Hitler's own version of an organized pogrom. On the night of November 9-10, 1938, synagogues were burned, Jewish cemeteries desecrated, Jewish-owned buildings were destroyed, and 26,000 male Jews were arrested. More restrictions on Jewish life followed: Jews were prohibited from attending college, visiting cultural centers, or using public transportation. The worsening situation caused Jewish emigration to increase, but many couldn't leave because the German government confiscated their property, and wouldn't allow them to transfer cash out of the country. Another barrier came from the potential host countries; many, including the United States, would accept only a fraction of the refugees who wanted to go there.

The rapid Axis advances in the first years of the war brought millions of Jews under Nazi domination. Administration of the conquered areas became the job of the SS and the Gestapo, or secret police; Jews living here suffered harsher treatment than the Jews in Germany. In Poland the world's largest Jewish community went into confinement, either quartered in ghettoes or hauled off to the concentration camps. Relocating the Jews took too long on the Russian front, where the standing order was to kill them on sight. In the occupied part of the USSR, the preferred solution was to dig trenches for mass graves, and machine-gun the victims as they stood in front of them.

In July 1941, Hitler's second-in-command, Hermann Göring, sent a directive to the chief of the Reich Security Main Office, Reinhard Heydrich, charging him with the task of organizing a "final solution to the Jewish question" in all of German-dominated Europe. By September 1941, the Jews of Germany were forced to wear badges or armbands marked with a yellow star. In the following months, tens of thousands were deported to ghettos in Poland and to cities wrested from the USSR. Over there, a new type of concentration camp was created, where the main goal was to kill the inmates, not to put them to work.

Prisoners were usually transported to the new death camps in railroad cattle cars, and told beforehand that they were going somewhere else. Upon arrival, those incapable of working (women, children, the ill and the aged), were usually marched to the gas chambers right away. Those who could work were subjected to forced labor, until that or the starvation rations ended their usefulness. Besides the gassings, victims could be killed in any diabolical manner dreamed up by the guards, from shootings and hangings to "experimental surgery." Auschwitz (modern Oswiecim, near Cracow) was the worst camp of all; more than a million perished there.

The administration of the camps was an example of German efficiency gone mad; it shows how the prisoners were regarded as nothing more than animals, an exploitable commodity. To start with, prisoners had to wear a cloth triangle on their clothing, colored to identify which category of untermenschen (inferior people) they were: brown for Gypsies, red for political prisoners, green for common criminals, purple for Jehovah's Witnesses, blue for immigrants, pink for homosexuals, and black for miscellaneous anti-socials. For Jews, two yellow triangles were put together to form a Star-of-David-shaped badge. Other record-keeping among the SS doctors produced the following statistics: the typical inmate's work was worth six marks a day, and he could be expected to work 270 days before he dropped dead; after death, his gold fillings, money, clothing, and objects like eyeglasses would be worth an average of 200 marks. After taking from this two marks for the cost of cremation and a tenth of a mark for amortization of clothing, a final profit of 1,631 marks would be realized, plus some further revenue from industrial use of the bones and ashes.

Hitler ordered the trains to keep hauling Jews to the death camps for as long as possible, even when his officers protested that they needed the trains to move men and materiel to the war fronts.(12) Outside Germany, rumors about the Holocaust leaked out as early as 1942, but many among the Allies refused to believe them, thinking that the stories were just wartime propaganda. The truth became clear to everyone in early 1945, when Allied troops advanced far enough into the Third Reich to reach the camps. Most of the soldiers were battle-hardened veterans by this time, but they were sickened by what they saw: prisoners reduced to living skeletons, many of them too weak to be helped by doctors; dead and dying victims everywhere; bodies stacked like cordwood outside gas chambers and crematoria; SS guards still shooting inmates right until the end. When he heard what was in the camps, US General George Patton, a tough warrior nicknamed "Old Blood and Guts," refused to go in, out of fear that the sights would make him sick -- now THAT'S bad. However the highest-ranking American general, Dwight D. Eisenhower, felt he had to see the horror for himself, and once he did, he called Washington, D.C. and London, telling them to send photographers, reporters, and anyone else who could record these atrocities, because he knew that someday people would refuse to believe they had ever taken place; that is why we have so much information documenting the Holocaust. The camps were only in use for a few years, but what happened there may be the most horrifying episode in the story of man's inhumanity to man. Linguists had to coin a new word--genocide, the murder of a race--to define the mass slaughter of ten million people, six million of them Jews. The following table shows how many Jews fell victim to the Nazis in each country:

| Nation | Approx. Jewish Population (1941) | Est. number of Jews killed by 1945 |

Concentration Camps |

| Austria | 70,000 | 65,000 | Mauthausen |

| Belgium | 85,000 | 28,000 | - |

| Bulgaria | 48,000 | 40,000 | - |

| Czechoslovakia | 281,000 | 277,000 | Theresienstadt |

| Denmark | 6,000 | 100 | - |

| France | 300,000 | 83,000 | - |

| Germany | 250,000 | 180,000 | Belsen, Buchenwald, Dachau, Flossenberg, Grossrosen, Mittelbaudora, Neuengamme, Oranienberg, Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, Stutthof |

| Greece | 67,000 | 65,000 | - |

| Hungary | 710,000 | 402,000 | - |

| Italy | 120,000 | 9,000 | - |

| Latvia | 100,000 | 70,000 | - |

| Lithuania | 140,000 | 104,000 | - |

| Netherlands | 140,000 | 106,000 | Vught |

| Poland | 3,000,000 | 2,600,000 | Aushwitz, Belzec, Birkenau, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor, Treblinka |

| Romania | 1,000,000 | 750,000 | - |

| (occupied) USSR | 2,500,000 | 750,000 | - |

| Yugoslavia | 70,000 | 65,000 | - |

Most of the other Axis dictators were less bloodthirsty than Hitler, and didn't share his enthusiasm for killing members of "inferior races." Italy, Romania and Hungary, in fact, refused to hand over their Jews to the Germans, until German troops occupied those countries late in the war. This loophole allowed many Jews an opportunity to escape by going first to one of Germany's allies, then to a neutral nation like Switzerland. Most of Denmark's small Jewish community survived because the Danes cooperated in ferrying their Jews to Sweden. Finland never gave up its 2,000 Jews, and gave asylum to Jewish refugees who came there. The Finnish government even continued to allow Jews to serve in its army, though this meant they had Jews fighting on the side of Hitler! On the other side of the world, the Japanese did not understand why the Nazis hated Jews, so they ignored the few thousand Jewish refugees in the territories they conquered (mainly in Shanghai and Manila).

After the war those Jews who survived did not want to stay in Europe, since they had lost their homes and families. In the east, the Soviet Union and its satellite states continued to practice its own form of anti-Semitism. Most Jews who could leave emigrated to the United States or Israel. Today only a remnant is left of the once vibrant European Jewish community: 30,000 Jews in the Netherlands, 8,000 in Poland, 70,000 in Hungary, 10,000 in Austria, 40,000 in Germany. Of all the countries unlucky enough to fall under Axis tyranny, only France ended up with more Jews than it had before the war (600,000 in the late twentieth century), and more than half of them were North African immigrants, forced to leave North Africa when French rule over that area ended. Now a lot of those Jews are making Aliyah to Israel, thanks to Islam-inspired terrorist attacks. A large percentage of European Jews are more than 65 years old, and intermarriage with Gentiles is common among the younger ones, so the 21st century will probably witness the total assimilation of the last Jews in Europe. If this happens, Hitler will have perversely succeeded in one of his goals, despite the total defeat of Nazism.

Underground Resistance

If Hitler had shown a trace of mercy, the Third Reich would have lasted considerably longer. Instead, he alienated the citizens of every country he conquered. Most civilians tried to go about their lives as normally as possible, if they did not collaborate with the rulers, but every year saw more of them join guerrilla/partisan units, collectively called "the Underground," to resist the Nazis. The Allied nations considered these movements worth several of their own divisions, and often the partisans helped by rescuing Allied pilots shot down over enemy territory. As early as 1940, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) office was equipping and encouraging resistance fighters, and so did its American counterpart, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), after the United States entered the war.

Anti-Nazi activity was strongest in the east, where the Germans had behaved with utter brutality. Red Army soldiers caught behind enemy lines formed the core of the resistance in the Soviet Union, which grew to number around 200,000 armed fighters. Yugoslavia fell to the Axis so quickly that tens of thousands of Yugoslav soldiers went into hiding, before the Germans could kill or capture them. By the end of 1941 they had organized themselves into two guerrilla movements. One, led by a Serb named Drago Mihailovich, was dedicated to restoring the Serbian monarchy; the other was led by Josip Broz Tito (1891-1980), a Croatian communist. Both attacked the Ustasha, the fascist regime set up in Croatia, and the Ustasha retaliated with a campaign of extermination against the Serbs.(13) In the long run, the communists did better; the brush wars of the late twentieth century showed that communism and guerrilla warfare work well together. From late 1943 onward the Americans and British only gave aid to Tito, because he was killing more Germans than anyone else in the Balkans. Poland also had a large Underground movement, though here it was nearly impossible for Britain and the United States to send help.

Similar but smaller groups of spies and saboteurs worked in Italy, France, Norway and the Netherlands. As in the east, many of these partisans were communists, which led to the rise of strong communist parties in postwar Europe. The German occupation force stationed in France had orders to act courteous and cultured, but this failed to end French hatred of the Boche. Eventually the Nazis resorted to their usual heavy-handedness, and resistance began to grow. The French fighters, a mixture of communists and de Gaulle's Free French, called themselves the Maquis, after the guerrillas that had long opposed the authorities on Corsica. The largest guerrilla force in western Europe was in northern Italy; it had more than 100,000 men by the end of the war.

Members of the Underground could expect only death and torture if captured; sometimes Nazi retaliation was even worse. In May 1942 the notorious Nazi administrator Reinhard Heydrich was assassinated in Czechoslovakia. A reward of ten million Czech crowns was offered for information leading to the capture of Heydrich's killers, but there were no takers, even after the reward increased to twenty million. Then the Nazis went to the map and randomly chose a victim to punish: Lidice, a village just west of Prague. All 192 men in the village were lined up and shot, while the women and children went to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Women under the age of 25 were assigned to brothels, and nine of the ninety-one children passed a racial test and were adopted by German families; the rest of the women and children were gassed to death. Then the houses were leveled, the cattle driven off, and the village pond filled in, leaving only a bare plain. The last step involved removing the name of Lidice from maps and government documents.

Despite all this, Lidice did not stay dead. Towns in Mexico and Illinois changed their names to Lidice when the Allies found out, and Venezuela gave that name to a new suburb. Several countries built memorials, and after the war the Czech government built a new village named Lidice, next to the old one; the original site became a memorial garden for the victims. This wasn't the case with another community the Nazis destroyed, Oradour-sur-Glane in central France. On June 10, 1944, two years to the day after the Lidice massacre, they drove into Oradour, shot or burned 642 people (all but six of the residents), and set the buildings on fire, to avenge the murder of another German officer. After liberation the French left the charred ruins of Oradour standing, but never publicized what happened, so today few people outside of France know about this atrocity.

In the long run, the Underground's greatest achievement was probably keeping the Germans from developing an atomic bomb. In the 1930s, scientists discovered that "heavy water" -- deuterium oxide (D2O) -- was an excellent material for controlling nuclear reactions, because deuterium atoms, unlike regular hydrogen atoms, have neutrons. However, heavy water molecules are extremely rare, about one for every 41 million molecules of good old H2O. To filter out and collect heavy water molecules you need a lot of water and a lot of electricity; the only facility in Europe that produced enough heavy water to use was Vemork, a hydroelectric plant at Rjukan, Norway. By the early 1940s, both Axis and Allied nations were trying to develop an atomic bomb. Leif Tronstad, the Norwegian professor who had turned Vermork into a heavy water producer, had escaped to England, and he urged Allied leaders to destroy the plant, because after the Germans conquered Norway, Vemork became critical to their atomic research.

Unfortunately, Vemork would not be an easy target; it was perched on an icy ravine and heavily guarded. In addition, the part of the plant used to make and store heavy water was in the basement, so airplanes could bomb it and still miss everything that mattered. Therefore a commando team would have to go in and personally destroy the equipment, to make sure the job was done right. An attempt to send in thirty British engineers on gliders failed because bad weather caused the aircraft to crash; those who survived the landing were captured by the Germans, tortured and executed.

For the second attempt, six specially trained Norwegians were dropped eighteen miles from the site by parachute, on the night of February 27, 1943, and they used skis to travel quickly and silently to Vemork. The bridge going over the ravine to the facility was guarded, so the commandos had to climb into the ravine, cross the river at the bottom, and then scale the 600-foot-high cliffs to get to the building. As treacherous as this sounds (and keep in mind that they did this in winter), they succeeded in getting past the obstacles, broke into the building without setting off the alarms, planted the explosives they brought, and escaped. The resulting explosions destroyed three thousand pounds of heavy water, which had taken four months to make, and put the plant out of action for five months. Of course a story this exciting was later made into a movie, The Heroes of Telemark.

When the Germans repaired Vemork, the Allies sent regular bombing raids, forcing the Germans to abandon the plant. They tried shipping the rest of the D2O to Germany, but the journey included a trip by ferry across a lake, and one of the commandos from the previous mission planted a bomb on the ferry, blowing it up on February 20, 1944. Thus, Hitler had to give up his nuclear project. If the mission against the heavy water facility had failed, and if Hitler had gotten the atomic bomb first, the war would have ended sooner, in a very unfavorable way.

The Battle of the Atlantic

The longest-running battle of the war was the one between Germany, Britain and the United States for control of the Atlantic. The sea lanes were crucial to Britain's survival, as they had been in the last war, and the Americans could not get involved in Europe unless the Allies ruled the waves. Despite this, Hitler considered naval power a low priority; he didn't even begin a full-scale buildup of the German fleet until 1939. Admiral Erich Raeder, the commander-in-chief of the navy, didn't want to fight until 1942; by then he hoped to have 250 U-boats, thirteen battleships, and four aircraft carriers. The beginning of the war forced him to cancel this plan, and hurry construction of the submarines instead.

Even so, the Germans had some secret weapons with which they hoped to gain the advantage. All of their ships were brand-new, for a start, while most of Britain's capital ships were built before World War I. The U-boats operated in "wolf packs," which proved to be a bigger challenge than the solitary raiders of the last war, and this time the submarine captains didn't bother with the "restricted warfare" that had so hindered them before. Early in the war the Germans introduced the magnetic mine, which didn't wait for a ship to hit it, but exploded when a ship came close. It was a success until November 1940, when a magnetic mine was found intact on a British beach and taken apart, allowing scientists to invent a defense against it ("degaussing"). In the early 1930s Germany built three cruisers with as many guns packed into them as possible, to get around the tonnage limitations of the Versailles treaty; these "pocket battleships" were more powerful than anything the Allies had of similar size. Using the "pocket battleship" idea also permitted the construction of two super-battleships, the Bismarck and the Tirpitz.

There was no "phony war" at sea. Just hours before Britain declared war on Germany, a U-boat sank a British ocean liner, the Athenia; 112 lives were lost, including 28 Americans. On the night of October 13-14, another U-boat, commanded by Captain Gunther Prien, slipped into the naval base at Scapa Flow, and sank the battleship Royal Oak; this was one of the most daring submarine raids ever attempted. A pocket battleship, the Graf Spee, wreaked havoc against Allied shipping in the south Atlantic, sinking nine merchantmen in two months, from Brazil to Mozambique. Finally on December 13, 1939, three British cruisers caught up with the Graf Spee outside the bay of the Rio de la Plata. In the battle that followed, all ships were heavily damaged, before the Graf Spee broke off and headed for Montevideo. Once in port, however, Captain Hans Langsdorff got the idea that he would not be able to escape, so a few days later he scuttled the Graf Spee and shot himself, ending a hunt that captured the attention of the world.

In May 1941, the Bismarck made her first and only foray into the war. The super-battleship, accompanied by the cruiser Prinz Eugen, sailed from the Baltic into the north Atlantic, with the intention of joining two warships and six U-boats already there. British planes spotted the Bismarck while refueling at Bergen, Norway, and immediately sent four ships in pursuit. Three days later, the Hood and the Prince of Wales, two of Britain's largest battleships, engaged the Bismarck between Iceland and Greenland. Only eight minutes after the battle began, a shell from the Bismarck found the Hood's magazine and blew up the whole ship; the Prince of Wales, badly damaged, limped away. The Bismarck also took a serious hit, and she changed course for the French port of Sainte-Nazaire, leaving a steady oil trail in her wake. On May 26, more British planes, cruisers and destroyers caught up with the Bismarck, 700 miles from occupied France, and went for the kill. The torpedoes from the planes couldn't penetrate the Bismarck's armor, but one disabled her rudder, making it impossible to escape; then torpedoes and shells from the ships finished her off. The sinking of the Bismarck was hailed as a great Allied victory, but it diverted so many ships and planes to the Atlantic that it may have permitted Hitler's victory on Crete at the same time.

While the Bismarck went down fighting, the career of the Tirpitz was long and inactive. After what happened to the Bismarck, Admiral Raeder didn't want to risk the other super-battleship in the Atlantic, and hid the Tirpitz in the fjords of Norway instead. The plan was to have the Tirpitz attack Allied convoys as they sailed past, on their way to Russia, but she saw no significant action; by mid-1942 the German Command realized that U-boats and the Luftwaffe did a better job at raiding. Even so, the presence of the Tirpitz so close to England kept the British nervous, and several air raids attempted to sink her. They failed because conventional bombs could not penetrate the dreadnought's double layer of armor plate; a special 12,000-lb. bomb called the "Tallboy" was invented in 1944, just to do that job. In September 1944 a squadron armed with the new bomb attacked at Kaa fjord, in northern Norway; they didn't sink the Tirpitz, but did so much damage that the Germans moved her south to Tromso, where they decided to use her as a floating artillery battery. There on November 12, 1944, another raid of Tallboy-equipped bombers finally blew up and sank the battleship. That event marked the end of the naval war in northern waters.

For the German navy, the best part of the war was from July to October 1940, when the threat of invasion kept the British fleet close to home, leaving convoys with almost no escort. During this time, each U-boat sank an average of eight ships per month. After that, though, the British began to work out an effective antisubmarine defense, and soon the Americans were helping as well. The entry of the United States in the war greatly expanded the area of operations. For a few months in 1942, the U-boats in American waters got choosy; pickings were so good that they let high-riding empty ships go by and sank only those that looked full. Eventually the Americans also learned how to defend themselves against the U-boats (sonar, depth charges, destroyer-escorted convoys, air reconnaissance), so the easy hunting ended by summer. The losses in men, ships and cargo were still appalling, but enough got through to keep Britain fighting, and each year after 1942 saw the German sailor's mission grow more suicidal.

For the U-boats, the most embarrassing defeat came because a U-boat captain did not know how to use a new toilet. The toilets on German subs could only be flushed when they were at or near the surface of the ocean, due to water pressure on the hull, so let's just say the atmosphere inside a U-boat could get really unpleasant if it spent a long time underwater. Even in the best of times, life on a submarine is not much fun, and extremely cramped; you can get an idea of it from the movie Das Boot. In April 1945 a U-boat, the U-1206, was launched with a new kind of plumbing that allowed underwater flushes, but the equipment was so complicated that most of the crew did not know how to operate it. That included the captain, and when he answered nature's call without the help of a toilet specialist, he turned the wrong valves and water started flooding into the sub. Because of the flooding, and because chlorine gas was released when sea water came into contact with the U-1206's batteries, the submarine had to surface immediately. Unfortunately this was right off the coast of Scotland, and Allied warplanes attacked it soon enough. Since the submarine could not dive again, the captain ordered the crew to abandon ship, and then scuttled it. Of the fifty crew members, one was killed in the air attacks, and three drowned. The remaining forty-six were captured, but unlike so many other sailors, they lived to see the war's end.

The Air War

World War II saw the warplane come of age; in nearly every campaign the outcome was decided by who controlled the air. We saw earlier how air power was crucial to the German victories, and how Hitler had to call off the invasion of Britain when the Luftwaffe couldn't defeat the RAF. The war also saw the residential districts of cities become targets for bombing; both sides regularly attacked civilians in bomber raids, and did much to destroy industry, but failed to destroy the other side's will to resist.

Britain launched its first raids on Germany in July 1940, while the battle of Britain was taking place. The commander of the Luftwaffe, Reichsmarshal Hermann Göring, boasted that if any Allied bombs fell on Berlin, people could call him Meyer (a popular German Jewish name). A lot of Germans called him Meyer before long, when they had to spend their nights in bomb shelters! However, these early attacks did little besides restore British morale; daytime missions were suicidal, while bombers that attacked at night couldn't see their targets. It took America's entry into the war and the development of long-range bombers before the Allied planes could inflict real damage.

The Allies began to get the upper hand against the Luftwaffe in 1942. Part of the reason was numbers: in that year the overextended Germans built about 15,000 aircraft, compared to 23,672 for Britain, 25,436 for the Soviet Union, and 47,836 for the United States. The other reason was that the British and Americans worked out a strategy for their bombing campaign; the more heavily armored American planes would attack in the daytime, while the RAF made its raids during the night, using new target-finding techniques. The first of these combined missions went against Lübeck in March 1942; the old headquarters of the Hanseatic League was full of wooden buildings, so the attack flattened or burned half the city. At the end of May, a massive force of 1,000 bombers incinerated Cologne, bringing the horrors of war to the heart of Germany. No more raids on that scale were attempted for the rest of 1942, but now nights in an air-raid shelter became a regular part of life for the Germans, rather than the British. Each year saw the raids on Britain decrease, while the raids on Germany increased:

| Bombs dropped on Britain (tons) | Bombs dropped on Germany (tons) | |

| 1940 | 36,844 | 10,000 |

| 1941 | 21,858 | 30,000 |

| 1942 | 3,260 | 40,000 |

| 1943 | 2,298 | 120,000 |

| 1944 | 9,151 | 650,000 |

| Early 1945 | 761 | 500,000 |

1943 saw the beginning of Allied bombing around the clock. By early 1944, advances on the Russian and Italian fronts made three-way bombing possible: bombers could take off from Britain, southern Italy or the Soviet Union, fly missions over any place the Axis controlled, and land in one of the other Allied areas. However, the raids didn't disrupt German production as much as the Allies expected, especially when they hit homes instead of factories, and Allied losses were also heavy; an American B-17 bomber, for instance, cost more than $250,000 in 1942, and its trained crew was even harder to replace. Furthermore, bombing civilian targets was a poor advertisement for the Allied cause; the worst example was the bombing of Dresden, where three raids in February 1945 killed 135,000 and turned that city into a smoking tomb. The bombing campaign's value was in the strain it put on the Luftwaffe, and how it increased the drain on Germany's resources. It also meant that German soldiers could no longer expect air support.

In 1944 the Germans invented some devastating secret weapons, which gave the Allies a few sleepless nights but failed to change the course of the air war. One of these was the first jet fighter, the ME 262. At a top speed of 540 MPH, it could outrun and outfight any other plane, but Hitler was not impressed. When Göring and other Luftwaffe generals argued that the ME 262 would make an excellent defensive weapon, he shouted, "I want bombers, bombers, bombers. Your fighters are no damned good!" For months he refused to even watch a test flight, then he changed his mind and ordered that the jet be converted into a bomber, though it had neither the range nor the load capacity.

Hitler probably liked another airplane design better, the Horten Ho 229. This was a bomber that could not be detected by radar, eliminating the advantage that saved the RAF in the battle of Britain. Using a "flying wing" design, the builders created an airplane that looked a lot like the B-2 stealth bomber the United States produced, forty-five years later. A prototype of the Horten Ho 229 was built and successfully tested at the end of 1944, but then American soldiers captured it, ending this remarkable project. Man, those German scientists were good; no wonder the United States and the Soviet Union wanted to capture them, after the war ended.

Two German secret weapons did see use in the war, with stunning results. The first was a forerunner of the cruise missile, the V-1 (the V stood for "vengeance"). Basically an unmanned, unguided jet full of explosives, the V-1 was tested at Peenemünde on the Baltic, and launched at London from bases in the Netherlands and northern France. The British were forced to station planes along the Channel to catch these "buzz bombs" before they hit anything. Then the Germans introduced the V-2; the Allies found this rocket unstoppable, because it traveled at a speed of 3,000 miles an hour, and flew as high as 60 miles before it slammed into its target with 2,200 pounds of TNT. Fortunately for the Allies, the V-2 could not be guided to a target, either; of those launched at Britain, one in five missed the island altogether. Also, V-2s were not cost-effective -- each cost about $500,000 in wartime dollars, while an American B-29 bomber could carry bombs weighing ten times as much as the V-2's warhead. Then when the Allies captured the launching sites on the Continental side of the Channel, the missile threat to Britain ended. The last attack of the Luftwaffe occurred around the same time (January 1, 1945), and the Germans lost so many planes that Göring never tried large-scale bombing raids again.(14)

The Underbelly of the Axis

1942 was the most crucial year of the war. It began like the last two, with the Allies on the defensive, reeling from the attacks of the dictators. But then the tide turned. It turned in the Coral Sea, at Midway Island, Guadalcanal, Stalingrad, and El Alamein. By the end of the year, the Allies were on the offensive, and they would remain so almost constantly for the rest of the war.

In the European theater, the Allied counterattack began on the southern fringe: North Africa. German air power had badly shaken, but failed to destroy, Britain's prewar naval supremacy over the Mediterranean. The tiny but strategic island of Malta underwent a hideous two-year siege at the hands of the Luftwaffe, but like Gibraltar, it remained in British hands. Honors in the desert war between General Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps and the British Eighth Army were even for two years and if the British had their supply problems (they had to sail around Africa, rather than use the Suez Canal), so did the Germans, because air and submarine attacks by both sides made travel in the Mediterranean a risky business for everybody.

Rommel's last success was his offensive of June 1942, which chased the British halfway to Suez. However, Rommel failed to break through the Alamein Line--the last defense before Alexandria--at that time, and again when he tried three months later. In October, the Eighth Army, led by General Bernard Law Montgomery, struck back. The Afrika Korps was hit very hard in this battle and barely managed to get out of Egypt; worse still, it couldn't stop to recuperate in Libya the way it had before because the Allies had opened up a second front in the rear--by landing British and American troops in Algeria and Morocco (Operation Torch, November 1942). Thus, Rommel had to withdraw to Tunisia. He managed to hold out for the entire winter because Hitler foolishly reinforced him, but in May 1943 the entire Afrika Korps (though not Rommel, who was recalled to Europe before the end) was forced to surrender.

The liberation of North Africa was a tremendous triumph for the Allies, but there was still the question of where and when the first attack on Hitler's "Fortress Europa" should begin. Stalin and Roosevelt both felt it should be in France, since it would crush the Germans in a two-front offensive from both east and west, but when a 1942 commando raid on the German defensives along the Channel (at Dieppe) ended in disaster, it was back to the drawing board. It would take the immense resources of the United States to force a breakthrough that way, and there wouldn't be enough Americans in England to try it until 1944, so Churchill proposed a smaller invasion for 1943. He suggested going after Italy, which he called "the soft underbelly of the Axis beast."

The attack began with a landing of eight divisions on Sicily (July 10, 1943). With the Americans racing around the west end of the island, and the British occupying the east, the Allies succeeded in driving out the Italian forces, along with their German help, by the end of August. And on July 19, the Allies were close enough to launch their first air raid on Rome.

Mussolini's showmanship and dictatorial powers concealed the fact that he had never abolished the government that existed before he took over in 1922; his official title was still prime minister, and Victor Emmanuel III was still the king of Italy. Because Italy had lost all its African colonies, and the Allies were now on Italy's doorstep, several of the men around Mussolini turned against him. To rally support, a tired, sick Mussolini summoned the Grand Council of Fascism on July 24, the first time that group had met since Italy entered the war. Instead, the council passed a "no confidence" vote by 19-8, and called on Victor Emmanuel to resume his powers. The next day, Mussolini met with the king, who told him that the war was lost, and Marshal Pietro Badoglio was the new prime minister. Immediately after the meeting, Mussolini was arrested. There were no protests when Mussolini fell; the Italians were sick of the war, and saw joining the Allies as the quickest way to get out. But as soon as they thought about quitting, Hitler suspected it; when it came to a double-cross he had always been a hard man to beat.

Hitler's action to keep Italy in the Axis was both swift and successful. The Italians, playing very carefully, didn't announce they were changing sides until September, when Allied forces landed on Sardinia, the Italian toe, and at Salerno. This delay gave Hitler enough time to transfer an army from Russia, which he used to occupy Italy and form a defensive line across the peninsula, between Rome and Naples (the Gustav Line). He also managed to find out where the new Italian government had locked up Mussolini, spring him from jail and put him back in charge.(15)

Mussolini with the German soldiers who rescued him.

Churchill's portrayal of Italy as a vulnerable spot may have been correct politically, but it wasn't from a geographical standpoint. The Italian peninsula has many streams and lines of mountains, providing numerous opportunities to set up defensive barriers. Once the Germans were in charge their commander, Field Marshal Alfred Kesselring, used a brilliantly flexible series of tactics that slowed the Allied advance to a miserable crawl. The Allies expected to be in Rome by Christmas, but the Gustav Line held until the last days of 1943.

In January 1944 an attempt was made to go around the Germans, by making a new amphibious landing at Anzio, less than 40 miles south of Rome. The landing achieved complete surprise, but once the troops were on the beach, their commander kept them there, waiting for the artillery and tanks that would back him up. This gave the Germans time to mount a counter-assault that bottled up the invaders on their beachhead--"the largest self-supporting prison camp in the world" is what German propaganda called it. Meanwhile, activity on the main front centered on a siege of the Monte Cassino monastery, the birthplace of the Benedictine order (see Chapter 6). Not until May 1944 was there a successful breakout, and in the end it was the main force that came to the rescue of the troops at Anzio, when the original plan had been for the opposite to happen. Allied troops finally entered Rome on June 4.

The capture of Rome was a moral triumph for the Allies--it was the first capital of an Axis state to fall into Allied hands--but it was overshadowed by the D-day landings which took place in France just two days later. D-day took away men and supplies from the Italian front, and those officers remaining showed a remarkable lack of imagination, seeming to think that all they needed was superiority in numbers and they would win in the end. This was true, but it also prolonged the Italian campaign much longer than necessary. The Allies had Kesselring on the run in the summer of 1944, for example, but they didn't follow him very closely; by August they had only gotten as far as the Arno River and the Etruscan Apennines. There the Germans dug in along a new barrier, the Gothic Line, and the Allies made no headway at all for months. By the time they broke through and liberated northern Italy it was April 1945, and Allied troops were so close to victory in Germany that what happened in the south no longer mattered much.(16)

The Liberation of France

The campaigns in North Africa, Italy, and the Pacific showed the Allies what had to be done if an amphibious invasion was going to succeed; the failed raid on Dieppe showed that thorough preparations were essential. Throughout 1943 and early 1944, troops from the United States, Britain and Canada assembled and trained in southern England. The Normandy coast, between Cherbourg and Le Havre, was picked as the place to land, because it was conveniently close to the airfields and ports in both southeast and southwest England, unlike the part of France at the narrowest point of the Channel, around Calais. By the spring of 1944, the massed force was so large that Hitler couldn't fail to notice it, and he placed a fifth of the German army (58 divisions, out of the 295 he had at the time) in France, making it the strongest point of "Fortress Europe," with his best general, Rommel, in command of the defenses. A complex Allied deception plan, which involved dummy tanks and troop maneuvers in the southeast, convinced the Germans that the main landing was going to take place at Calais, so they held back several divisions from the action, even after the Allies began the attack in Normandy.

American soldiers on D-Day.

The original date for "D-Day," June 5, 1944, had to be cancelled due to extremely bad weather, but on the following day there was a lull in the storm, so the commanding Allied general, Dwight D. Eisenhower, reluctantly gave the go-ahead. The largest amphibious assault in history, involving five divisions (two American, two British, and one Canadian), took place on the beaches of Normandy. Not only were the Germans totally surprised, they happened to be leaderless on that day, and this helped a lot. The same bad weather which made Eisenhower postpone the landing had also convinced Rommel that the Allies would not try to land at all, so he drove home to celebrate his wife's birthday, meaning he couldn't be reached for several critical hours. There was another general on the scene, Field Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt, who correctly guessed from the air raids on June 5 that the Allies were about to land at Normandy, and he tried to get the two nearest panzer divisions sent there. Those tanks would have made short work of the Allied troops, but they were under the direct command of Hitler, and would not move unless he ordered them to do so. To complete this comedy of errors, Hitler had left orders to let him sleep late on the morning of June 6, and his guards were too frightened to wake him up for any reason, including a massive invasion that was sure to decide the war!

Though the Allies had to spend their first month on the coast building up their force to full strength, they did manage to liberate the nearest French town to the west, Cherbourg. At the end of July the Americans succeeded in breaking out of that zone. Swinging first through Brittany, the US armies turned to the east in a maneuver that tried to pin the Germans back against the British; they weren't quick enough to catch the panzer divisions they were after, but they did trap and destroy a German army at Falaise. In late August, the Allies approached Paris, and they stood aside so that de Gaulle and the Free French could have the honor of liberating the city.