| The Xenophile Historian |

A History of Christianity

Chapter 8: THE CHURCH IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY

This chapter covers the following topics:

Nationalism

The famous historian Arnold Toynbee believed that three post-Christian ideologies had replaced the great world religions: nationalism, communism and individualism. Carried to their logical conclusion, all three make huge demands on their followers, and are anti-Christian and dehumanizing. Christianity's grip on Western society had been chipped at by Marxism, Darwinism and secular philosophy, so it was unable to make an adequate answer to the challenge posed by these ideas.

Man will always venerate something, and as religion faded from daily life in the 17th-18th centuries, nationalism stepped in to take its place. Nations came to be seen as personalities, leading to the development of the modern political cartoon, with nations represented as animals (e.g., the American eagle, the British lion, the Russian bear or the Chinese dragon) or as individuals like John Bull, Uncle Sam, the goddess Britannia, etc. Gradually people came to a nation as the property of its people, not the property of the monarch. For example, they defined England as the land of the English people, rather than the land ruled by King George.

All this may seem trivial to our point of view, but take note of this: if people see a king's authority as coming from themselves, rather than from God, it's a small step to consider running a nation with no king at all! That inspired both the American and French Revolutions, and from those came nationalism, the idea that one's nation is greater than any other. Eventually this attitude of "my country right or wrong" would lead to militarism, imperialism and racism.

As the twentieth century began, the general mood in Europe was one of unprecedented optimism. Technology, industry, science and society were all progressing at a faster rate than ever before. European civilization was now supreme around the globe and had brought everyone under its influence. It was an age of rising standards of living, longer life spans, more comfort, better health, growth in democratic government and personal liberty, humanitarian advances and a flowering of literature and art. Many Christians adopted an idea called post-millennialism, meaning that they expected to create a heavenly kingdom on earth that would last for a thousand years before Jesus came back.

Along with this came the idea that cooperation between nations is better than competition. In the eleven years preceding World War I, no less than 162 treaties were signed, establishing international laws and pledging cooperation on various matters. Famous individuals also contributed to the peace movement. Alfred Nobel, the Swedish inventor of dynamite, established the Nobel Peace prize, and Andrew Carnegie, the American steel baron, founded the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and built a Peace Palace at The Hague in the Netherlands as a permanent neutral ground for future international meetings (Ironically, the building was finished just before World War I began.). But examples of international cooperation were still less visible than examples of competition. Progress in inventing new weapons outstripped progress toward getting along with each other. Few at the time could see that rivalry between competing nations would yield not a utopia, but a harvest of unparalleled human destruction.

In spite of all well-meaning efforts, early twentieth-century Europe became a powder keg, fueled by an escalating arms race and imperialist confrontations abroad. France wanted revenge for the humiliating defeat Germany inflicted on her in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), and Germans who read Nietzsche's theories on the "Superman" now saw themselves as the "Superstate." Meanwhile, Britain was confident it could deal with any crisis, and the British sang this little verse that gave us the word jingoism:

"We don't want to fight, but, by jingo if we do,

We've got the ships, we've got the men, we've got the money too."

Since France felt it could not take on Germany by itself, it formed alliances with Britain and Russia; in response, Germany allied itself with Austria and Italy. Then little countries like Serbia and Bulgaria allied themselves with the big ones. Ironically this increased the chance of war, because now any country in an alliance thought it could start a fight without suffering the consequences. By 1914 all Europe was an armed camp, and when a Serbian terrorist shot the Archduke of Austria, everyone thought it was a good enough excuse to start World War I.

Just about everyone expected the war to be a short one, a rerun of the "genteel wars" of the nineteenth century. Both sides expected to win swiftly, the result being that a few soldiers would get killed and the rest would go home full of stories to tell their grandchildren. In August the German emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, boasted to his troops: "You will be home before the leaves have fallen from the trees." In Britain far more young men enlisted than could be easily trained or equipped; all of them were eager to get involved in what looked like the adventure of a lifetime. When the first British soldiers went across the Channel, the rest protested, expecting the war to end before they got their chance to go for glory, and with a mind-set almost incomprehensible to us, some British officers refused to let their men wear steel helmets because they thought it was unsporting!Only later did everyone realize how much things had changed. There were too many countries involved to allow a short war, and technology had changed the weapons, strategy and tactics completely. The submarine, machine gun and barbed wire were used on a larger scale than ever before; as the conflict went on warplanes, poison gas and tanks were invented. Yes, this would not be an easy war at all. The only observer who seemed to know this in August 1914 was the British Foreign Minister, Sir Edward Grey. As he watched the lamplighters making their rounds in St. James' Park, he remarked sadly: "The lamps are going out all over Europe. We will not see them lit again in our lifetime."

That war wiped out most of a generation of Europeans. Afterwards, in the Treaty of Versailles, the victorious Allies tried to punish Germany's new government, the Weimar Republic, for the sins of the kaiser, without realizing this could backfire. Ten years later, while most of Europe was still recovering from the ravages of the war, the Great Depression hit, and millions of starving, unemployed people turned to a new, more dangerous form of nationalism: totalitarianism. A totalitarian government has an ideology and a strong leader, both of which demand that all aspects of human life submit to the will of the state, for the good of all. We will discuss the left-wing form of totalitarianism, communism, in the next section. Right-wing totalitarianism is commonly called fascism, and several major nations embraced its dictators in the 1920s and 30s: Italy got Benito Mussolini, Portugal got Antonio Salazar, Spain got Francisco Franco, and Japan got Hideki Tojo. In Germany a group called the National Socialist (Nazi) party produced a tyrant without match in the whole sorry history of inhumanity--Adolf Hitler.

Fascism motivates people by calling for a return to traditional values, and glorifies the nation, defining it as imperial greatness, a national mission, or simply as a racial and ethnic community that is better than all others. The result is a form of civil religion, with its own saints, creeds (Mein Kampf in Nazi Germany), and an emphasis on anti-rationalism, courage, and violent struggle against all enemies. Private property and capitalist enterprise are permitted, though tightly controlled.

The fascist leaders of Italy, Portugal and Spain were able to get along with Pope Pius XI and his successor, Pius XII (1939-58), despite some differences. In Germany, however, it was a different story. Nazism rejected the ideas of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, and idealized the primitive past portrayed in Wagnerian operas and Germanic sagas, where the complexities of modern life did not exist and one could usually deal with his enemies by killing them. To this barbaric foundation the Nazis added prejudice against foreigners, "race science" (an effort to distinguish between superior and inferior types of people), and a form of social Darwinism, teaching that strong nations will eventually destroy weaker ones. Then Hitler singled out the Jews, calling them "a culture-destroying race" which had given the world all its problems. He blamed them for introducing capitalism, Marxism, and even Christianity: "The heaviest blow that ever struck humanity was the coming of Christianity. Bolshevism is Christianity's illegitimate child. Both are inventions of the Jew."

Many German Christians sympathized with the Nazis when they first took charge of Germany in 1933, and thought that if they treated Nazism with understanding, it would outgrow its current faults (particularly its racism and neo-pagan ideology) and restore the nation. In turn, Hitler tried to get along with the Church, though he envied the wealth and influence of the Papacy and despised Protestants for their division and weakness. Any church, even a Nazified one, would divide loyalties, and he wanted no such limitation on his power. As time went on, he dabbled in occult practices and listened more to Nazis with anti-Christian sympathies, who wanted to eliminate both the "German Christians" and opponents of Nazism in the church.(1) After World War II began, they saw clergy and devout laymen in occupied territories, especially in eastern Europe, as enemy agents, and those that weren't shot out of hand joined the Jews in concentration camps. The need for popular support kept Hitler from completely eradicating Christianity, but what lay ahead was dramatized in the territory around the Polish city of Poznan. The Nazis renamed this area the Warthegau, and turned it into a model German province; they removed the Poles and Jews living there, brought in Germans from elsewhere to take their place, and all but wiped out the institutional church.

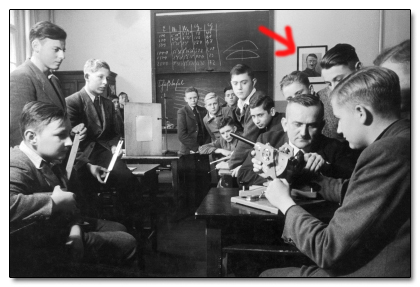

The classroom of a Catholic school in Nazi Germany, with a red arrow indicating its special feature.

During World War II, most clergy of the countries involved pledged loyalty to their governments. In America and Britain the Church engaged in humanitarian activities, but did not become the chauvinistic, bond-selling, recruiting, hate-Germany organization it had been in World War I. The largely Church-led peace movement which tried to keep America out of the war collapsed after Pearl Harbor, but the rights of its conscientious objectors were largely left alone. German Churches, both Catholic and Protestant, publicly urged their people to back the war effort, and Russian Churches enthusiastically supported "the Great Patriotic War." In 1941 the Japanese government forced its tiny Christian community to unite into one church, the Kyodan, which urged believers to "promote the Great Endeavor."

Despite their wartime support, many German clergymen grew increasingly alarmed as the Nazi state interfered in religious affairs, and declared the "new heathenism" a heresy. Most of them, however, did not oppose the regime openly, or stand up for democracy and individual rights, because they felt the German people were not on their side, and feared retaliation from the state. A notable exception, Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-45), was an active member in the anti-Hitler resistance movement. He served as a double agent for the British, and wrote a rich legacy of writings calling for Christians to reject a comfortable, undisciplined life. In 1943 he was arrested for smuggling fourteen Jews to Switzerland, and hanged two years later. After the war, surviving Church leaders in Germany admitted their guilt in failing to speak out against the Nazi regime, especially in its early stages. Many of them confessed to anti-Semitic feelings, which they felt encouraged the Holocaust, and gave their support to the new state of Israel.

As a guardian of moral and spiritual values, the pope should have spoken out against German aggression, especially when word got out about the murder of millions of Jews. Why then did Pius XII remain silent? Critics argue that he could have prevented the Holocaust by speaking out vigorously, and threatening to excommunicate those Catholics who took part in Hitler's "final solution." He was silent because speaking out would have alienated German Catholics, many of whom were anti-Semitic at heart, and Hitler would have reacted by smashing the Church wherever he could get his hands on it. Preserving the Church seemed more important than saving Jewish lives. In addition, the pope didn't want to undermine the Axis war effort against Russia; he always regarded atheistic communism as a greater evil. It was a situation where taking either side would have been asking for trouble, yet his inaction is still controversial today.

In recent years, evidence has come forth showing that there were no real neutrals in World War II. Switzerland and Sweden, for example, did considerable business with the Axis, though they did not enter into a formal alliance. More incriminating, it now appears that Pope Pius XII favored the Axis, and secretly hoped they would win. The Ustasha, Hitler's puppet government in Croatia, had an office in the Vatican; Pius XII denied as late as 1942 that a "final solution" against the Jews was taking place; after the war he denounced the Zionist movement, declaring that the Jews had lost the right to their own country two thousand years earlier. Finally, high Catholic church officials helped several Nazi war criminals, including the notorious Adolf Eichmann, to escape to South America when the war ended, and to this day the Vatican has never excommunicated a Nazi war criminal, not even Hitler. When somebody asks why Judeo-Christian relations are taking so long to heal, the answer is that Christians still have much to answer for, and some of the wrongs committed may still be discovered in the future.

The generation after the war saw the colonies turn nationalism against those who introduced it to them. New nations appeared almost every year in Africa, Asia, the Pacific and the Caribbean; some gained their independence peacefully, others not so peacefully. Most of them have learned to live in peace and not grab land from their neighbors, even in places where the colonial powers drew artificial boundaries that split tribes in two or put unfriendly ethnic groups in the same country. Today modern commerce, transportation and communication (especially the Internet) have made old-fashioned nationalism largely irrelevant, but let us not declare it dead just yet. If the unrest in formerly communist countries like Yugoslavia is any indication, there will be more brush wars in the areas where nationalism had been temporarily suppressed, and new dangers to the Church will arise to replace old ones.

Communism

Karl Marx never thought of Russia as a likely place where his ideas would first be put into practice; he always expected the communist revolution to begin in the most advanced countries of the West, where capitalism had flourished for a long time. This may have been a proper assessment of the situation during his lifetime, but it wasn't after the twentieth century began. By now the proletariat (workers) of the advanced countries, through labor unions and progressive governments, received better pay, improved working conditions, and other material benefits of capitalism, causing the desire for revolution to diminish. In Russia, on the other hand, factory workers were the lowest paid in Europe (about $90 a year), and everyday life was still nearly as nasty, brutish and short as it had been during the Middle Ages. These were workers who had nothing to lose but their chains!

Hostility to all religion, especially Christianity, has been a characteristic of communism from the start. Marxism calls religion a false consciousness, an illusion created by those in power to justify their oppression of everybody else. Marxism also predicted that religion will die a natural death when communists create a natural society, but that hasn't kept communists from actively struggling against religion; they see it as a reactionary social force that will prevent progress if it is not smashed.

When Lenin and the Bolshevik wing of Russia's Communist Party took over Russia in 1917, the Russian Orthodox Church faced an enormous challenge; it knew that the peasants and workers needed improvements in their lives, but it could not bring itself to endorse an ideology so diametrically opposed to its own. The Bolsheviks responded quickly, by confiscating Church property, canceling state subsidies to the Church, decreeing civil marriages (as opposed to church weddings), and nationalized the schools. They converted many church buildings into factories, cinemas, houses, and museums. Those buildings which did not produce revenue for the state were allowed to remain places of worship, "so long as they do not disturb public order or interfere with the rights of citizens." Churches and sects were denied the rights of ordinary people in court, which put them in a very vulnerable legal position.

In 1925 the Bolsheviks sponsored an atheist movement, the League of Militant Godless. This group spread anti-Christian propaganda, promoted classes in science and philosophy, and produced antireligious films, plays, talk shows, literature and exhibits; often they displayed the exhibits in former churches. Four years later the government passed the Law on Religious Associations, which banned churches from engaging in educational, social or charitable work. It also prohibited Bible studies, womens' or young people's meetings, and even material assistance to church members. All they allowed to remain was public worship, effectively cutting away the Church's influence on society.

The 1930s saw the worst persecutions; clergymen were denounced as "clerico-fascists," and many of them fell victim to Joseph Stalin's purges against real and imagined opponents. By the end of the decade the Russian Orthodox Church was on the verge of disintegration; the Lutheran, Baptist and Evangelical organizations were nearly wiped out; many Russian Mennonites immigrated to America. Similar treatment was heaped on Roman Catholics, Uniates (Catholics who submit to the pope but keep many Orthodox customs), Old Believers, Jews and Moslems.

The Soviet Union's antireligious attitude began to soften during World War II, especially after Hitler invaded the USSR in June of 1941. Stalin changed the tone of his speeches; he stopped talking about Marxist ideals and called upon the Russians to defend the "Motherland" in patriotic terms. Atheistic propaganda was reduced, and antireligious laws were no longer enforced as much. Recognizing that the Orthodox Church could motivate people to support the war to its conclusion, and promote Soviet policy views, he gave back its status as a legal organization, and allowed it to own property, collect funds, and give children religious instruction. Stalin even allowed the Church to have a patriarch, its first since 1700. Christians in Britain and the USA, who had been denouncing communism just a few years before, found the USSR to be an unexpected ally.

Always preoccupied with security, Stalin spent the last eight years of his life strengthening control over the country. He was so thorough at this, in fact, that the years 1945-53 were the most repressive in Soviet history. Western art, literature, clothing and lifestyles (even jazz) were banned, and foreign tourists were not allowed to visit the USSR until 1958. During and immediately after the war 1,250,000 people from seven ethnic groups of dubious loyalty were accused of collaboration with the Nazis and deported to Central Asia and Siberia. The always unruly Ukrainians were next on Stalin's blacklist, but even he had to concede that there not enough trains in the USSR to get rid of all 40 million of them. Stalinist rule was toughest in those areas that had just come under Soviet rule since 1939, like eastern Poland, and the Catholics living in those areas were regarded as untrustworthy and forced to join the Orthodox Church. This resulted in a strange spectacle as the officially atheistic Soviet state threw its powers of coercion behind the Orthodox clergy.

The postwar years saw communism spread beyond the USSR to eight eastern European countries unfortunate enough to be "liberated" from the Nazis by the Soviets. This prompted the US and its allies to counter Soviet expansion with a "containment" policy, especially after China was "lost" in 1949. Any form of communism, no matter how small its following, was seen as a direct threat to American security. The American-Soviet rivalry, which we now call the Cold War, quickly took on an ideological dimension, thanks to the antireligious stand of the communists. Westerners came to see communism as a world conspiracy, directed by Moscow, at least until China broke with the Soviets in the early 1960s. Pope Pius XII was extremely critical of communism (he excommunicated Catholics involved in communist activities), and so were American Catholics (Senator Joseph McCarthy was one). Protestant pulpits in America regularly thundered with anti-Communist sermons, and denounced those liberals who saw accommodation with the enemy as a possibility.

Some Latin American Catholics tried to coopt Marxism, rather than fight it; we call this approach Liberation Theology. When local governments, many of them right-wing juntas, and American foreign aid failed to solve the problems of hunger and poverty, many concluded that capitalism would always perpetuate the gap between rich and poor nations; for them China and Cuba became role models for Latin America's future. Liberation Theology's leading proponents included Gustavo Gutierrez (Peru), Juan Luis Segundo (Uruguay), Jose Miguez Bonino (Argentina), Jose Porfirio Miranda (Mexico), and Dom Helder Camara (Brazil). To them salvation comes mainly through political and economic liberation, and they concentrate on those parts of the Bible (Old Testament prophets like Amos, and the teachings of Jesus) which attack the principle of private property. The result was a form of Christianity that was a little bit of Jesus and a lot of Marx. As Father Camilo Torres, a Liberation Theologist who was shot in 1966, put it: "The Catholic who is not a revolutionary is living in mortal sin." In recent years, though, Liberation Theology has declined, because of three factors: (1.) the ultimate failure of communism in every country that tried it, (2.) the replacement of caudillos (dictators) with true democracy in nearly every nation south of the border, and (3.) the open opposition to the movement by Pope John Paul II.

The communist regimes of the Cold War years were all hostile to religion, but not all of them treated it the same way. Albania and North Korea were the only ones that rooted it out completely; in fact, the Albanians broke diplomatic relations with the USSR in 1961 because they felt that Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin's successor, was too tolerant (!) of religious activity. Mao Zedong saw Christianity as a Western colonial influence, so he expelled all foreign missionaries, liquidated religious organizations, and launched a ruthless wave of persecutions, but after his death in 1976 a state-run Chinese Church was set up.(2) Bulgaria, always the USSR's most loyal satellite in Europe, toed the party line and always kept its churches under severe restraints, while Mongolia did the same thing with its Buddhists. East Germany, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia permitted considerable religious activity when Soviet troops weren't forcing those countries to knuckle under, as they did in the 1950s and 60s. Yugoslavia and Romania generally tolerated Christians and Jews to show that they weren't mindless Soviet puppets; Romania went so far as to allow practicing members of the Orthodox Church to be members of the Communist Party, something other communist states would not permit. Poland saw the most toleration of Christians, because the Poles have always seen the Catholic Church as their friend, not their oppressor. The USSR had to go easy on Poland to keep it in the Soviet Bloc, due to the millennium-old hatred between Poles & Russians, and because the Catholic Church was so strong that for all practical purposes it served as an opposition party (especially after 1978, when Polish Cardinal Karol Wojtyla became Pope John Paul II). All Soviet bloc states tolerated Islam to avoid alienating Moslem allies in the Third World like Syria, Libya and Iraq.

Despite spasmodic ill-treatment, Christianity survived in most of the places where Communists took over. A Russian Baptist once explained this by saying that "Religion is like a nail. The more you strike it, the harder it is to pull out." To fight Christianity, communism became a secular religion, reminding us of the maxim that if you fight the same enemy long enough, you will come to resemble him. Communism has its holy books (the writings of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Mao, etc.), its holy city (Moscow), its holy icons (Lenin's body, which the faithful still go to see), and its own world view and ideology. Communists in western Europe (Euro-Communists) soon learned not to accept the "one true way" of the Moscow "popes," and went their own way in 1976; the leader of the Spanish Communists, Santiago Carillo, declared that: "For years Moscow was our Rome. Today we have grown up. More and more we lose the character of a church." 1988 marked the 1,000-year anniversary of Russian Christianity, and they broadcast the celebrations on TV; they also praised the Church as a builder of moral character, a 180-degree turn from past policy.(3)

When the Soviet Bloc collapsed in 1989-91, one effect was a religious revival everywhere. The election of Alexei II as Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church was hotly contested, because this was the first time the choice for Church leadership made a difference. The doors are now wide open for evangelism in ex-communist countries, but in the chaos that marks today's Russia, there are still many who see evangelists as a subversive influence, though for different reasons. In 1996 General Alexander Lebed scared many by declaring that the only religions which had any business in Russia were Orthodoxy, Islam and Buddhism (actually the only foreign creeds he admitted disliking were Mormonism and Aum Shinri Kyo, the murderous Japanese cult, but Jews and evangelicals asked themselves why he didn't say anything about them). And while we may have declared the Russian bear dead, Communism lingers on in China, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos and Cuba, and the Communist Party looks to return to power in the next Russian election.(4) Whatever happens next over there, the next few years promise to be exciting ones.

Individualism

There are three dangers that can bring down any nation: invasion, rebellion, and corruption. Of the three, corruption is the worst, since instead of coming from outside, it comes from within, and it directly attacks and weakens the nation's people. Using the same analogy, militant nationalism and communism are enemies outside us, while individualism (another name for secular humanism) is a corruption in the soul and spirit of modern man. From our perspective individualism is the most dangerous of the three twentieth-century -isms, because nationalism and communism are on the way out, while individualism is stronger than ever. For more than two thousand years the devil has worked to make the human race lose its fear and awe of God; by using Greek philosophy, the western idea of human rights, and the attitude that people are more important than God, he has succeeded. As pointed out before, we have paid less attention to our Lord and Creator in every generation since the Reformation. It is my belief that Satan will use individualism to create a one-world government that rejects God (as least God as we know it) completely, to rebuild the ungodly civilization that existed before Noah's Flood and at Babel. When this world state, the "Beast" of Daniel 7 and Revelation 13, arises, it will be time for Jesus to return and set up God's kingdom on earth.

We noted that at the beginning of the twentieth century most people were very optimistic about the future, and expected that this century would see the creation of a true Utopia, a perfect world. Then came World War I, and men began to wonder. Whatever dreams they still had of mankind creating a better future were laid to rest beside Hitler's gas ovens in World War II.

Despite these nasty shocks, there are still those who believe that man left by himself is generally good, and he can improve himself without God's help. I guess some will never learn. These folks point to the Holocaust and ask how someone can have faith in God when such an awful thing happens, and I ask, how can one have faith in man when such an awful thing happens?(5)

Anyway, the result of the above shocks was a replacement of the previous optimism with a pessimism about human nature; many see the twentieth century as an age of anxiety. This age has disproved the liberalism of nineteenth-century philosophers and theologians, but many people continue to follow it anyway. Today's thinkers often deny the existence of God, but have nothing to offer in its place; many of them take the viewpoint of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), and reduce man to a collection of neuroses and reactions to sensory stimulation, who can't help it if he goes wrong. They also deny the historical accuracy of the Bible, rendering its teachings invalid.

Attempts have been made to bridge the growing gap between Christianity and the philosophers. We mentioned some in previous sections: Deism, theistic evolution, and Liberation Theology. Another is the Social Gospel, put forth by Walter Rauschenbusch in 1919 and calling for improvement in social and economic conditions through political activism.(6) Whatever you call such compromises, the result is always a spiritless, powerless Church with services and sermons that are as dull as dishwater. Karl Barth (1886-1968), an important theologian early in this century, attacked liberalism, but his Neo-orthodoxy, which combined liberal Bible criticism with a transcendent God and Holy Spirit, has been criticized as a cure no better than the disease he tried to eradicate.

In America we call the movement to reverse liberalism in the Church fundamentalism, after a series of doctrinal statements published in 1909 by B. B. Warfield, H. C. G. Moule, James Orr and several other writers, under the title The Fundamentals. As the name implies, fundamentalists have a back-to-basics attitude toward Christianity. They believe in Biblical infallibility, the substitutionary death of Christ for our sins, the reality of eternal punishment, and that everyone needs personal salvation. Unfortunately, liberals succeeded in giving fundamentalists a bad name, by portraying them as both anti-intellectual and anti-cultural. They also use the term fundamentalist to describe other religious fanatics, like Moslem terrorists who blow themselves up on Israeli busses or those vegetarian Hindus who attack Moslems in the name of "cow protection." Consequently many modern conservative theologians who would fit the description of fundamentalists shy away from that label today.

The best defense of traditional Christianity in the face of modern thought came from Clive Staples Lewis (1898-1963), an Oxford professor who wrote many creative literary works and allegories, like The Screwtape Letters and The Narnia Chronicles. I will finish this section with a quote from Lewis' Mere Christianity which says it all:

"'I'm ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don't accept his claim to be God.' That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic--on a level with the man who says he is a poached egg--or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must take your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God; or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon, or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God. But let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to."

Protestant U.S.A.: A Faith for the Frontier

The largest Protestant community in today's world lives in the United States of America. "Upon my arrival in the United States," Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in 1835, "the religious aspect of the country was the first thing that struck my attention." Throughout American history visitors have remarked on the religious character of the United States. G. K. Chesterton, for instance, concluded that America thought of itself in religious terms and that the United States was "a nation with the soul of a church." Gallup poll data tells us that 94 percent of Americans believe in God or a universal spirit, as compared with 76 percent of the British, 62 percent of the French, and 52 percent of the Swedes. In addition, 65 percent of Americans claim membership in a church or synagogue, and 42 percent attend religious services in any given week.

The dominant Protestant churches in today's United States. Click on this thumbnail for the map to open full size in a separate window.

Americans are undeniably a religious people. To a remarkable degree, many seek to fashion their conduct around religious principles, and their religious communities very often define their social networks. Throughout their history Americans have believed that their country occupies a special place in the divine plan. When Thomas Prince wrote his history of New England, early in the eighteenth century, he felt compelled to begin his narrative with the Genesis account of creation, so confident was he of America's special place in God's plan. The Puritans saw themselves as the New Israel, fleeing the Egypt of England for the Promised Land of Massachusetts. Even Benjamin Franklin, so much a man of the Enlightenment, proposed that the seal of the United States depict Moses leading the children of Israel across the Red Sea.

Today foreigners still call Americans the most religious people in the Western world. Yet very little of this is shared in American history books. One gets the impression from a typical textbook in today's public schools that Americans were religious when they came over on the Mayflower, but after the Salem witch trials religion played no important role whatsoever. The propagandist can be very clever when he rewrites history--what he doesn't write can have as much effect as what he does write--and we can't count on improperly educated students knowing the truth, especially if the teacher doesn't know it either (a lot of American history teachers in today's high schools go by the first name of "Coach"). I hope that this session will help to fill this gap in our heritage.

The American Revolution divided Christians among the thirteen colonies. The New England branch of the Church of England stayed loyal to England, while Episcopalians in the southern colonies joined the revolutionaries. Because of their commitment to pacifism, the Moravians and the Quakers refused to get involved on either side. John Wesley opposed the Revolution, so most of his Methodist ministers returned to England during the war; only Francis Asbury remained, so he became the founder of American Methodism. The other denominations tended to support the Revolution. One result of these conflicting activities was that the United States was born without a state church, and before long the first amendment of the Constitution would make sure that it stayed that way.

A long spiritual drought followed the Great Awakening; churches became places of dead ritual again. However, a second great revival was just around the corner. In 1795 Timothy Dwight, the president of Yale and a grandson of Jonathan Edwards, started this revival by giving many lectures and sermons against Deism, infidelity and materialism. The Presbyterian James McGready and the Methodist Peter Cartwright spread the revival to the frontier, where people were grossly ignorant about how to live a godly life. In 1801 Presbyterians and Methodists got together to stage a "camp meeting" in Kentucky, and so many people were saved that outdoor revival meetings have been used as a tool of evangelism ever since. Perhaps you met the Lord at such a "retreat."

The nineteenth century was a time of rapid growth for the United States. As Americans moved west, pushing the frontier from the Appalachians to the Pacific, the more dynamic denominations went with them. Three sects which had not amounted to much during the colonial era--the Presbyterians, Baptists and Methodists--gained the most from this adventure. The Presbyterians did well because of a mutual alliance with the Congregationalists, once they realized that they were in full agreement on doctrine, only differing in their method of organization. Baptists did better, because their emotional call for salvation had more appeal to rugged frontiersmen than the scholarly sermons of Presbyterians. The Methodists did best of all, because innovations of theirs like open-air meetings, log-cabin churches, and a system of traveling ministers ("circuit riders"), were ideal for spreading the Gospel to remote areas.

Since Americans never forgot that everyone is equal in the eyes of God, American revivals took on a democratic character rarely seen in missionary activity elsewhere; some have called them "a crusade among equals." As in England, ordinary people were encouraged to get involved in political or social issues. Americans were so steeped in optimism about the perfectibility of individuals and society that their churches organized reform societies (temperance reform, abolitionism, female suffrage, prison reform) with a zealotry unmatched in American history. Other campaigns were directed against institutions that promoted sin, like theaters, prostitution, Sabbath-breaking, dueling, immigration, slums, and most important, Roman Catholicism and slavery. Witness the nativist sentiment directed against non-Protestant immigrants, and McGuffey's Reader, the most widely used school book of the nineteenth century, with its unabashed celebration of Protestantism and patriotism.

Protestant Americans inherited from England a strong dislike for Protestantism's oldest enemy, the Roman Catholic Church. They accused Catholics of trying to take over American schools so they could throw the Bible out and get their ideas in. In 1836 the Americans who moved into Texas revolted against their ruler, Mexico's General Santa Ana, when he presented them with a list of demands which included an order to convert to Catholicism ("Remember the Alamo!"). Ten years later, during the Mexican War, there were rumors of popish plots to poison American soldiers. When America went to war against Spain in 1898, President William McKinley sent a force to conquer the Philippines because he claimed that God told him it was America's duty to educate, modernize and "Christianize" the Filipinos.(7) Prejudice, however, is bred by ignorance and separation, and as Catholic immigrants arrived here in large numbers from places like Ireland and Italy, Americans grew more tolerant. The first sign of this came in 1884, when a pastor called the Democratic Party the party of "rum, Romanism and rebellion." So many were turned off by that statement that part of Republican Party voted Democratic a few weeks later, electing Grover Cleveland president. Despite this change of attitude, though, all but one of our presidents (John F. Kennedy) has come from a Protestant background.

The slavery question divided many churches. Some felt that the Bible authorized slavery, because there are rules in the Old and New Testament for treating slaves (Paul's Epistle to Philemon, for instance); others felt that owning another human being is cruel, and that nothing but evil can come from it. There was a movement in the 1820s to send freed slaves back to Africa, which ended after enough returned to start the nation of Liberia. In 1831 William Lloyd Garrison brought up the issue up again by producing an Abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, and called the Constitution "an agreement with Hell" because it allowed slavery. Soon northern evangelists like the famous Charles Finney joined the Abolitionist cause, though they weren't political radicals. Many southern churches in turn felt the need to support slavery because they couldn't see how the economy of the South could turn a profit without it. Southern Methodists declared themselves independent from Northern Methodists in 1845, and the Southern Baptist Convention was founded in the same year; Presbyterians and Episcopalians also split when the Civil War broke out, though because they stayed neutral on the issue, they could reunite after the war ended.

After 1860 ministers from both the North and South sent their young men to fight in Union or Confederate armies. Julia Ward Howe wrote "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" in 1861 to explain that God was "trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored" (the South), and that God's truth (the northern cause) was marching on. Confederates answered with this prayer to the same God: "Lay thou their legions low, roll back the ruthless foe; Let the proud spoiler know, God's on our side."

The end of the Civil War did not restore good relations between the northern and southern churches. Northerners thought the southern churches, along with the ex-slaves, needed evangelizing, while southerners refused to pledge loyalty to the Union, or to admit that slavery was wrong (the Southern Baptist Convention finally apologized to blacks for previous mistreatment in 1996). Most blacks became Baptists or Methodists, where they were freer to express themselves during services; their churches still have a distinct character today, in worship, gospel music and member participation.(8)

Today's black churches came into existence largely because black Americans were excluded from white congregations, in the decades of segregation which followed the Civil War. The black church became the only social institution that gave support to ex-slaves in a racist society. Perhaps because of that, leading civil rights activists, both then and now, have come from black churches--the most outstanding example is Dr. Martin Luther King--and some white Christians were moved to join their black brethren in speaking out against the sin of racism and the need for social justice.

More often, however, Christianity has had a conservative influence on American life. Witness the praise of conservative Christian values in McGuffey's Reader, the identification of capitalism with Christianity by powerful businessmen such as John D. Rockefeller, the fundamentalist political resurgence since 1975, and the fierce conservatism of the Mormons. Many Christians only challenge the political or social order to champion so-called traditional values or to evoke a past when America was supposedly more religious. Examples of this include efforts to reverse the Supreme Court's 1963 decision banning prayer in public schools; attempts to ban the teaching of evolution or to teach the Genesis account of creation next to Darwinism in public schools; the right-to-life movement; lobbying efforts like Jerry Falwell's Moral Majority in the 1980s, and Ralph Reed's Christian Coalition in the 90s; and the increasing number of parents who home-school their children. At the same time, many politically active Christians call upon and perpetuate the enduring myth of America as a Christian nation and Americans as God's chosen people.

Historically, religion has shaped America's higher education as well. Many of the nation's most prestigious universities trace their origins to people who wanted the best possible college for members of their faith: Harvard, Yale, and Dartmouth (Congregational); the College of William and Mary and Columbia (Anglican); Princeton (Presbyterian); Brown (Baptist); Georgetown (Jesuit); Brandeis (Jewish). Although many of these institutions have slipped their religious moorings, others (Notre Dame, Southern Methodist, Brigham Young) have remained more faithful to their origins. In addition, religious groups began hundreds of colleges to expand their influence on American culture: Colby (Baptist), Connecticut Wesleyan (Methodist), Davidson (Presbyterian), Gettysburg (Lutheran), Kenyon (Episcopal), to name a few.

Finally, we should mention two outstanding American evangelists. The most important in the nineteenth century was Dwight L. Moody (1837-99), though you would not have expected it from his early life. He was one of nine children born to a Unitarian family in Northfield, Massachusetts. His father died when he was four, and he did not finish school, leaving home at the age of seventeen to work in his uncle's shoe shop in Boston. There he was converted by his Sunday school teacher, Edward Kimble.

Moving to Chicago in 1865, Moody became a successful businessman and an active member of Plymouth Congregational Church. Every Sunday he filled four pews in the church with those he had recruited, and became a successful recruiter and administrator for the Sunday school. Soon he was a full-time worker for the ministry, preaching to soldiers, speaking at Sunday school conventions, establishing his own church and serving as president of the Chicago YMCA.

It was on a tour of Great Britain (1873-75) that Moody decided his real calling was evangelism. When he returned he teamed up with Ira Sankey, a hymnwriter and musician, and together they worked and traveled for the rest of his life. He was never a polished speaker, but the style and organization of his campaigns set the pattern followed by mass evangelism ever since. During his last years he established two schools, a regular summer Bible conference in Northfield, and the Chicago Evangelization Society, now called the Moody Bible Institute.

Another great revivalist who worked to make America "one nation under God" was William Ashley "Billy" Sunday (1862-1935). Billy's father died as a Union soldier in the Civil War when he was only a month old, and he grew up in an orphanage. He became an outstanding baseball player, playing for the Chicago White Stockings, the Pittsburgh Pittsburgs, and the Philadelphia Phillies. One Sunday in 1887 Billy and some of his teammates were invited to "The Old Lighthouse," an outreach of the Pacific Garden Mission, and there Billy found Christ.

At first Billy Sunday used his fame as a baseball hero to make people listen when he talked about Jesus,(9) but soon gave up his athletic career to become a full-time worker for the Chicago YMCA. Then he joined the traveling team of evangelist Dr. J. Wilbur Chapman; when Chapman decided to go back to being a pastor, Billy went into evangelism on his own. During the nearly four decades that followed he spoke face to face, without loudspeaker, radio or television, to an estimated 100 million people. Wherever he went large tents were set up, and sawdust was put on the ground to reduce noise; hundreds walked the "Sawdust Trail" every night to accept the Lord. Campaigns became front-page news and lasted for months, with more than ten thousand hearing a typical sermon of his.

Billy Sunday reached people from all walks of life with his folksy jargon, frequent references to baseball ("Hit a home run for the Lord!"), and constant gestures to keep the crowd focussed on him. Whatever city he preached in became morally cleaner and a safer place to live. Because he preached hardest against "booze," many saloons closed down because they lost their customers. Here are two of his typical statements:

"I'm against sin. I'll kick it as long as I've got a foot, and I'll fight it as long as I've got a fist. I'll butt it as long as I've got a head. I'll bite it as long as I've got a tooth. And when I'm old and fistless and footless and toothless, I'll gum it till I go home to Glory and it goes home to perdition!"

"I'm going to fight this liquor business till hell freezes over, and then I'll put on ice skates and fight it some more."

For much of the nineteenth and twentieth century, the conventional wisdom was that any nation which modernized and industrialized would make religion unimportant. America's persistent spirituality, however, has confounded those experts. In the United States, one of the most modern nations on earth, religion remains very much a part of both private life and public discourse.

Strange New Sects

Because of the size of America's Protestant community, and the willingness of Americans to try something new, it is perhaps natural that many of the newest denominations (those founded since 1800) are of American origin. The first half of the nineteenth century was marked by spiritual experimentation: Anti-Masonic groups, spiritualism, Mormonism, and various spiritual communes. Some of these groups "push the envelope," making it difficult for outsiders to agree on whether they are really Christian; others step across the limit completely, by rejecting traditional Christian teachings and promoting new ones.

The most successful (and most exotic) of the new sects is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, also known as the Mormons. This movement got started in 1820 when a teenager in upstate New York, Joseph Smith (1805-44), claimed he had met the Lord, and all existing churches and Bibles were in error. Three years later he reported that an angel named Moroni showed him the location of some golden plates buried in the ground, and he would use them to reestablish God's true Church. The writing on the plates was "reformed Egyptian hieroglyphics" (no, I haven't heard of this language either), and contained the true history of the Jaredites, the first inhabitants of America after the Tower of Babel incident; the history of the Nephites, a Jewish group that came to America to escape the Babylonian Captivity, which the American Indians are supposedly descended from; and a claim that Jesus visited America to preach to the Indians after His resurrection. The translation of these plates became the Book of Mormon, a book considered equal with and "supporting but not supplanting" the Bible; afterwards the angel took the plates into Heaven (a convenient answer to critics who wish to examine the originals!). In 1830 Smith, his scribe Oliver Crowdery, and four others established the church.

The new church grew rapidly--upstate New York had plenty of people willing to listen to a new prophet--and came under persecution because of its strange practices, especially polygamy. Just a year later Smith and his followers had to move to Kirtland, Ohio. In 1837 they moved to Independence, Missouri, were expelled, and settled in Nauvoo, Illinois (1840). Violence followed them everywhere, and in 1844 a mob broke into the jail where Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were being held and murdered them. This senseless act of violence made instant martyrs of the two.

The leaders of the Mormon Church elected Brigham Young as their new leader; a minority faction, though, argued that Young couldn't legally succeed Joseph Smith, since he wasn't related, and left to found splinter churches. In 1846 Young and the main body, about 5,000 people, pulled up stakes again and moved west. Their goal was to find a new home in a place so remote that nobody would bother them. They thought they found it when they reached Great Salt Lake; the surrounding land was so desolate that even the Indians didn't want it! Unfortunately for them, this was also the time of the Mexican War, and the United States expanded its frontiers faster and farther than the Mormons did. The Mormons found themselves surrounded by U.S. territory on all sides, forcing them to come to terms with the fact that they would become the state of Utah, rather than the independent nation of "Deseret."(10) Salt Lake City, "the City of the Saints," grew so quickly that Utah qualified for statehood in the 1850s, but it was delayed until 1896, because the federal government insisted that the church drop its stand on polygamy first.(11)

Politically the Mormons are as conservative as fundamentalist Christians; Utah is a favorite stronghold of the Republican Party. In spiritual matters, though, they accept many beliefs and practices not found in traditional Christianity. Some of these are "celestial" or eternal marriage, baptism for the dead, and the Book of Mormon, which generally takes precedence over the Bible when there is a discrepancy, despite claims otherwise (Mormons think parts of the Bible were not translated properly). Since the last chapter of Revelation warns against adding to the Word of God, I think that we can call Mormonism is a post-Christian religion, rather than a Protestant sect (remember that Islam likewise claims that the Koran supersedes the Bible).

Every generation produces believers who look at the problems of their day and think that the Second Coming of Jesus, followed by the Millennium, are about to take place. There were quite a few of these folks in the nineteenth century, and they produced two sects that are still going strong: the Adventists and Jehovah's Witnesses. Both groups, like the Mormons, believe in a clean, conservative lifestyle, and will abstain from alcohol, tobacco, and pork; they also insist on Saturday worship services and practice vigorous evangelism.

The Adventists were founded by William Miller (1782-1849), a Baptist lay minister who predicted that the Lord would come on March 21, 1843. The date came and nothing happened--nor did anything happen on the subsequent dates he picked. Most of Miller's followers left at this point, but enough stayed to form several Adventist organizations. They disagreed over the following issues:

- Will Christ reign on earth for a thousand years after His coming, or will He destroy the earth and take all His followers into Heaven?

- Will the wicked be eternally punished or completely obliterated?

- When will the righteous dead be resurrected, and are their souls conscious now?

- Should the Sabbath be celebrated on Saturday or Sunday?

I believe that an Adventist can be a follower of Christ at the same time, but the Adventists, like the Catholics, load a bunch of ideas and requirements on members that God never called for. However, I believe the Jehovah's Witnesses have strayed beyond the limits of what we can call true Christianity. Their founder, Charles Taze Russell (1852-1916), did not believe in the Trinity, the deity of Christ, or the existence of Hell, and expected the Lord to come to Earth in 1914. In 1872 he started to preach his views, and a few years later founded the Watch Tower Tract Society (now known as the Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society). For the Jehovah's Witnesses, publications have been the most successful way to gain converts. Watch Tower presses turn out an awesome amount of literature--100,000 books and 800,000 magazines daily!

When 1914 arrived the result was World War I, so Russell declared that Jesus did come, but invisibly; it would take more years of work to redeem the earth. Following his death, a Missouri lawyer named Joseph Franklin Rutherford took charge of the organization. Previously they had used many names (Russelites, Millennial Dawnists, or International Bible Students); in 1931 Rutherford chose the name Jehovah's Witnesses, from Isaiah 43:10. Whatever you call it, "Judge" Rutherford made the organization more respectable, since he had been to college (Russell only had a seventh-grade education); he also discarded some of Russell's stranger theories about the gathering of the Jews and prophecies found in the measurements of the Great Pyramid. Rutherford wrote prolifically, and his works were declared divine revelation. After Rutherford's death in 1942, though, subsequent leaders like Nathan Knorr and Frederick William Franz ignored his writings when they became inconvenient. Membership has swelled to 4.2 million around the world.

The pronouncements that issue from their Brooklyn headquarters are binding, and they tolerate no deviation. Those who violate the commandments are disfellowshipped, considered already dead, and declared unworthy of resurrection. Jehovah's Witnesses will not vote, serve in the armed forces, or salute the flag, because they feel that all governments are evil. They do not accept blood transfusions or organ transplants, even if the lives of their children depend on it, because they see them as a violation of Biblical commandments against eating blood (Leviticus 17:10-15). Until 1952 they did not even receive smallpox vaccinations. To them Jesus was not bodily resurrected; the disciples saw a "spirit." Members do not associate with outsiders, so you may only meet them when their door-to-door evangelists knock on your door (Give them credit for persistence; Watch Tower statistics claim that it typically requires 740 house calls to get one new member!). To deal with discrepancies between their practices and Biblical teachings, they have a specially prepared Bible called the New World Translation, which students of the Word have noticed is significantly different from the Bible you're familiar with.

Like other groups who think the end times are near, the Jehovah's Witnesses have picked another date for the Second Coming every time the latest prediction did not come to pass. After 1914 the new dates prophesied have been 1918, 1920, 1925, 1941, and 1975. Despite this poor batting average, members claim it must happen soon, before the last of their "anointed class" of 144,000 members dies. Since the youngest of the "anointed" were born in 1914, only a few thousand are left.

Of course there are many more such nonconformist or cult movements; the only limit may be one's imagination. There are the Christian Scientists, whose idea of mind-over-matter healing is neither very good Christianity nor very good science; Unity (not to be confused with the Unitarians), which combines reincarnation with positive thinking; Scientology, which combines science fiction, pop psychology, a lucrative business, and a "priesthood"; personality-centered cults like Sun Myung Moon's Unification Church; and blatant occult and Eastern religions. The purpose of this class is not to look at these groups in any detail; besides, other authors like Walter F. Martin, Josh McDowell, and Bob Larson have done a more thorough job of that already. Besides, new groups are popping up all the time, while old ones fade away. Let it be enough that we must be aware that such groups exist, and we must study the scriptures so that we do not fall for false teaching. The most dangerous cults of all are the ones that teach the truth more than 90% of the time, because with them we are unlikely to notice when they slip a lie past us!

Pentecostalism

While the institutional church has tried to channel the Holy Spirit through bishops and sacraments, some Christians consider a personal relationship with God more important. Examples of such Christians from previous lessons include St. Benedict, the founders of the Moravian Church, and John Wesley, whose heart was "strangely warmed" when he got saved. Many of what we call "the gifts of the Spirit" were manifested when Wesley preached, and in the camp revivals of the nineteenth century "Holiness" teachers saw this outpouring, which they called "the baptism of the Holy Ghost," as a true sign of salvation and God's activity in this world.

These were the foundations for the Pentecostal Revival of the twentieth century. It all came together on Azusa Street, in Los Angeles, in a meeting that lasted for three years (1906-09). Here they declared that a person baptized in the Spirit will "speak in tongues," heal the sick, and perform other miracles like those in the New Testament. Several hundred Christians from all over North America, and some from Europe and the Third World, visited Azusa Street and took this message home with them. Shortly after that several new denominations emphasizing Pentecostalism arose; the largest in the USA are the Assemblies of God, the Church of God in Christ, the Church of God and the Pentecostal Holiness Church.

What makes Pentecostalism different from previous movements in the Church is that it did not just produce a new denomination. In fact, it is more appropriately described as a fourth major branch of Christianity. Whereas Orthodoxy makes tradition its main authority, Catholicism emphasizes an earthly organization, and Protestantism gives priority to the Bible, Pentecostalism is centered on the "gifts" and "fruits" of the Holy Spirit. It has grown dramatically everywhere, especially in Africa and Latin America, but it also found widespread acceptance as a revitalizing movement in established churches, both Protestant and Catholic.

In the 1960s a second wave of Pentecostalism, called the Charismatic movement, spread among the young people, hippies and dropouts disillusioned with modern society. For several years groups of "Jesus People" held rallies, discarded their sex and drugs and rock & roll, and became enthusiastic followers of Christ.(12) Those who thought Christianity was on the way out could not explain what happened. In 1966, for example, Time Magazine declared on its cover that God was dead, but in 1971 it did a cover story on Jesus, asking, "Is God coming back to life?"

Nobody knows for sure how the Jesus movement started. No preacher or mass crusade got it off the ground. The two foremost evangelists of the late twentieth century, Billy Graham and Dave Wilkerson, gave it their endorsement, but they seem to have been bystanders rather than movers and shakers. If there was a single initiator, it could have been Ted Wise, a drug-using sailmaker who lived near San Francisco. On the surface, one might not think of San Francisco as a suitable place for a revival; the city was notorious at the time for student revolutionaries, the Black Panthers, nude beaches, strange religions like Anton LaVey's Church of Satan, Haight-Ashbury, Timothy Leary and the drug scene, gays coming out of the closet, angry mobs and racial violence. But God works with unlikely people in unlikely places. Wise stumbled on a stray Bible in 1966 and began reading it. He quietly committed his life to Christ, and shared his discovery with his friends. A year later they opened a coffee house in Haight-Ashbury to introduce street people to Jesus and the Bible. We estimate that during the next two years they won between thirty and fifty thousand souls to Christ, and these ex-freaks started Christian groups on the west coast, and eventually all over America.

The Pentecostals were the first Christians to use television effectively for evangelism. Billy Graham's crusades were broadcast on TV, allowing millions who normally would not attend such a meeting to hear his salvation message. The 1970s saw the rise of several "TV evangelists," and new television networks dedicated to evangelism, like PTL and CBN. They were very effective in reaching shut-ins and other people who did not go to regular worship services. Soon they spawned other businesses on the side, which only distantly related to their original mission; PTL, for example, ran an amusement park called Heritage USA in South Carolina. Unfortunately, television is a very expensive form of communication--much more than radio or newspapers--and it gets more expensive every year. TV evangelists found themselves spending an improper amount of time asking for money from viewers to keep their programs on the air, and corruption set in. In the late 1980s came a series of scandals some called "Pearlygate," where many famous evangelists came to grief because of sex scandals or failing to deliver on promises made to donors. This was probably God's way of purifying His Church, because even small ministries which did not broadcast were influenced by this purge. TV evangelism is still going on today, but hopefully those watching are wiser; as in traditional churches, you can find both true men of God and charlatans, and they are no easier to tell apart than the proverbial tares among the wheat. All I can say is, be careful if you hear one say something like, "Trouble happens, but a $20 pledge will keep trouble from happening to you!"

In an age when membership and attendance in many mainstream churches is declining, those who have accepted the Pentecostals, like the Baptists, have seen their numbers grow, often in double-digit figures. Because of that, many see Pentecostalism as the Church's best hope for renewal and survival in the years ahead.

Preaching the Good news to All Nations

Of all the changes the Church has experienced in recent history, the most exciting is the dramatic shift in its geographical and cultural center. Two hundred years ago, a visitor from another planet would have concluded that Christianity is a European religion for white people. With a few easily explained exceptions, every Caucasian in Europe and Europe's colonies professed Christianity. With a few more exceptions that could be explained by survival or conquest, nobody else did.

If this observer returned in our own time for a second look, he (She? It?) would get a completely different picture. This time he would find Christianity firmly established on six continents, with people of just about every ethnic background professing faith in it. It would be growing fastest in Africa, Latin America and the Far East. By contrast, it would be declining in Europe, the area which had previously been its stronghold. The causes of this reversal--the industrial revolution, the rise and fall of colonial empires, and the missionary movement, are related in a complex way, and I probably did not do them justice in the short time we have. The result is a worldwide Church, and on that note I hope to bring our journey to a triumphant conclusion.

As pointed out previously, the Protestants did not engage in much missionary activity before the eighteenth century. If you had asked one why he did not follow Jesus' commandment to "preach to all nations," he probably would have said that obeying an order given only to the Apostles is not appropriate. When Captain Cook discovered Hawaii and other islands in the Pacific, he didn't think Christianity would ever be preached there because nobody could make a profit from it. To combat vice and Presbyterianism in the American colonies, the Church of England launched the first modern missionary society, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), in 1701. However, the SPG was only interested in evangelism among English citizens living overseas. That changed because of two reasons:

1. The Pietists and Moravians went forth to preach to non-Europeans like the American Indians, shaming other Protestant denominations into doing the same.

2. The evangelists of the Great Awakening, Jonathan Edwards in particular, had a vision of the world "filled with the knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea," and expected it to happen in their lifetimes. Also remember John Wesley's most famous quote: "The world is my parish."

As with the Anglican Church in England, the SPG could not act without the government's permission, so it moved painfully slow. Because of that, when the second Evangelical Revival took place, other English churches jumped in to fill the gap. The Baptists were the first, founding the Baptist Missionary Society in 1792. Its leader, William Carey, sailed to India the following year, and spent the rest of his life there, preaching and making converts in and around Calcutta. When not doing that, Carey supervised six complete and twenty-four partial translations of the Bible into Asian languages, founded the Agricultural Society of India to improve native farming techniques, did some award-winning botanical studies, and took a leading part in the campaign to abolish the ancient Hindu custom of suttee (the burning of widows on the pyres of their husbands). Other Protestants in the mission field would soon eagerly follow his example.

Before the 1790s were over, the Presbyterians, Anglicans and Methodists had set up missionary societies of their own, and gave them the freedom needed to act on their own when it took weeks or months to send a message to the Church in the mother country. The United States was not far behind, despite its youth; a Calvinist Baptist, Adoniram Judson, became the first American missionary in 1812, traveling to India and Burma.

In the Victorian era, every denomination based in England or the United States was expected to have a missionary society. Other Europeans participated too, but the general rule of thumb was that most Protestant missionaries came from the UK or USA, while most Catholic missionaries came from France. A small but significant liberal missionary movement developed in the early twentieth century, which was more sympathetic to non-Christian religions, and put more emphasis on social work than the winning of souls for Christ (Dr. Albert Schweitzer was a famous example of this type of humanitarian). Only rarely did doctrinal differences cause discord between the different missionary societies, and as recently as 1950, many children in Christian homes and Sunday schools were brought up with stories about the brave "missionary pioneers."

Christianity's East Wind

Often British missionaries claimed that their country owed a debt to Africa because of the slave trade, and to Asia because of the wealth taken from it. What they should give back was the best Britain could give in return--"Christianity, commerce and civilization." Rudyard Kipling called this duty "the white man's burden," while the French spoke of the mission civilisatrice. This caused Westerners to believe in a strange mixture of idealism and imperialism--they felt they must conquer the non-Western world to save those people from themselves or unfriendly outsiders. For instance, Scottish missionaries begged for the United Kingdom to step in and take over the rest of Africa before Portuguese misrule spread from Mozambique, bringing war and slavery with it. When France decided that it wanted a colony in the Far East, it went for the country where French missionaries had been most successful--Vietnam. Protestant missionaries and their converts feared annexation by a Catholic power and vice versa. Sometimes conquest was justified in that it would open up territories closed to missionary work; they were right, for the rulers of "closed" areas knew that to let in one type of white man would ultimately mean admitting them all. Only some American missionaries seem to have opposed the spread of colonial empires, and they didn't protest when the United States claimed islands in the Pacific like Hawaii, Guam and the Philippines.

The nationalist movements that undermined the colonial empires in the twentieth century were often led by individuals who received from Christian schools the education they needed to be effective. Many missionaries sympathized with the nationalist dreams of their students, prompting strong criticism of missions from the white settlers in places like Algeria, Indonesia and South Africa, who hoped to stay in charge indefinitely. All this made for a complex situation; sometimes missionaries preceded the flag of the conquering army, sometimes they followed it. One thing is clear, though; not only did the missions help cause imperialism, they also sowed the seeds of its destruction.

The growth of Christianity from a European to a worldwide phenomenon is illustrated by who attended the first three interdenominational missionary conferences. At the First World Missionary Conference, held in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1910, only seventeen of the more than 1,200 representatives came from the Third World (eight from India, one from Burma, three from China, one from Korea and four from Japan). The Second World Missionary Conference (Jerusalem, 1928) presented a more balanced picture, while the third (Madras, 1938) sent delegates from fifty countries, nearly half of them non-Western.

After World War I, the Church suffered great disillusionment in the West, but it showed unexpected vitality among its nonwestern converts. Also important, more than half the new believers were Protestants, showing that the Catholic Church had lost its leadership role in the mission field. For example, by the 1970s Japan had 300,000 Catholics and 800,000 Protestants. The American Baptists who went to Burma (Myanmar since 1989) did not convert the Burmese, who remained committed to Buddhism, but they converted the Karens, the country's largest minority. And we already mentioned the existence of uncounted millions of believers in China. Most dramatic of all is the growth in Korea. In 1912 this country, so isolated that outsiders called it "the Hermit Kingdom," had 80,000 Catholics and 96,000 Protestants, making for a total of about 1% of the population. With the split of Korea into a communist north and an anticommunist south, South Korea became very receptive to anything that came from the United States, including missionaries. Today the church with the world's largest congregation is not in the West, but in Seoul, founded by an Assembly of God pastor, Dr. Paul Yong-gi Cho; it claims three quarters of a million members. The latest figures I have (1994), list South Korea's population as 38% Protestant, 11% Catholic. If current trends continue, South Korea will forget its Buddhist-Confucianist past and become a predominantly Christian nation in the next decade. Since North Korea is literally starving to death as I write this, it is likely that North and South Korea will reunite under Seoul's direction. If that happens the North Koreans will probably become Christians, too.(13)

Also encouraging is that many countries which were formerly closed to missionaries are open now, like Bhutan, Nepal, Mongolia and the Central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union. In India restrictions were placed on foreign missionaries following independence in 1947, and this encouraged Indian Christians to stop relying on outsiders to provide leadership and assistance. Protestants in India found that the doctrinal differences which divided Protestants in Europe and America didn't apply to them here, and they merged to form a single denomination, the Church of India, in 1961. By 1974 Protestants, Catholics and the Mar Thoma Church (an ancient Nestorian community which claims to have been founded by the Apostle Thomas) claimed 14 million believers between them; in the 1990s 22 million is the most likely figure. East of Iran, only Afghanistan, which has always had either Moslem or Marxist rulers (most recently the radical fundamentalist group Taliban), is closed to the Gospel at this time.

Some tribes in Papua New Guinea scarcely knew that white people existed as recently as World War II. After the war fifteen different Protestant groups and several Catholic orders sent missionaries. By the time that country became independent in 1975, it was reportedly 92% Christian, of which more than half was Protestant.

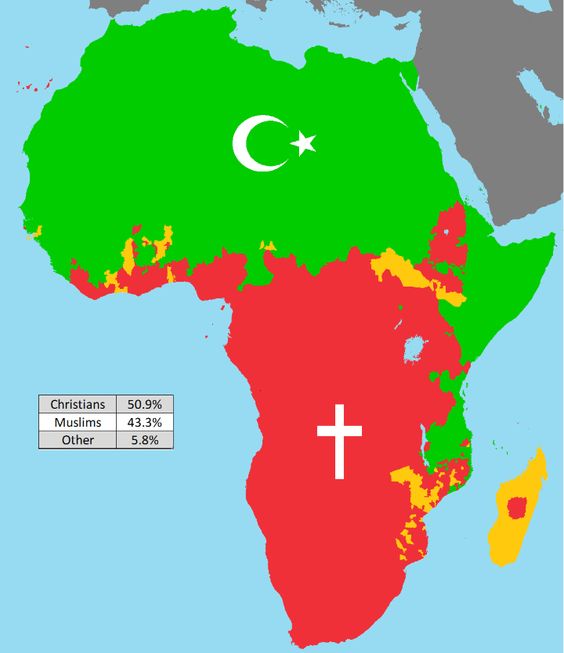

Zulu Zion

Today there are an estimated 340 million Christians in Africa, meaning that for the first time since the seventh century there are more Christians than Moslems on that continent. Of these 128 million are Catholic, 29 million are Coptic (Egyptian or Ethiopian Orthodox), 28 million are Anglican, 91 million come from other Protestant churches, and the remaining 64 million belong to local independent denominations. Western missionaries gave black Africa a modern educational system, which survived Africa's struggle for independence mostly intact. Many foreign missionaries had to leave when nationalist leaders took over, but most of the new governments tolerated Christianity, especially after the formation of native churches not directly tied to churches abroad.(14) Most African Christians want fellowship with churches on other continents (many have joined the World Council of Churches), without being dominated by them. The survival of Christianity in the post-colonial Third World is no longer in doubt, just the survival of those churches dependent on Western missionaries and soaked in Western culture.

There is one notable exception, though: the Sudan. Moslems have run this crossroads between the Sahara and Black Africa since independence, and its regime has seen the Arab, Moslem north persecute and oppress the black, Christian south. In 1992 fundamentalists declared the Sudan an Iranian-style Islamic republic; they have even brought back slavery to break up Christian families. If this hasn't made the evening news, I suppose it is because our media considers domestic issues like the O.J. Simpson trials to be more important. At any rate, in Africa Islam is more dangerous to believers than communism or individualism, and there are brothers and sisters over there who need our prayers!

Several names have been used to describe the African independent churches: indigenous, separatist, prophetic, messianic, millennial, or Zionist. No single name is appropriate, for hundreds of sects exist, and they differ greatly from one to the next. Nor does an African convert to Christianity cease to be African; if he can keep his ancestral heritage, he will. Most of these churches are Bible-centered, and many campaign against parts of the old religion which are definitely anti-Christian such as witchcraft, charms and fetishes; others attack modern vices like tobacco, alcohol and gambling. Many do not consider monogamy essential, and a few have emphasized polygamy.

One way to classify them is into "Ethiopian" churches, which are organized the same way as Western churches but run entirely by Africans, and "Zionist" churches, which are charismatic and seek to build a "Zion" (Promised Land) of their own. Many of the latter were started by individuals who became famous as prophets and/or healers. It is not unusual for an African to belong to both a mainline church out of loyalty and respectability, and to an independent church for his spiritual needs.

There are several underlying reasons why independent churches have been so successful:

1. The desire to be free of foreign domination.