| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A Concise History of Southeast Asia

Chapter 5: THE SECOND INDOCHINA WAR

1954 to 1975

This chapter covers the following topics:

America's Mandarin

|

|

|

|

As the French withdrew from Indochina, the American Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, conceived a plan for a military alliance to keep communism from spreading in the region. This was SEATO, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization. SEATO, however, had shortcomings that limited its effectiveness. To start with, the name was inaccurate. Only two Southeast Asian countries (Thailand and the Philippines) joined SEATO; the other members were Britain, New Zealand, Australia, France, Pakistan and the United States. Worse than that, the alliance only defended its members from an invasion by conventional forces, rather than the guerrilla units that are common in this region. Like too many generals, Dulles was preparing for the last, rather than the next war. Since no invader obligingly marched in with banners and bugles, SEATO remained inert in one of the world's most troubled areas.

SEATO's contribution came during the Second Indochina War, when it sent soldiers from Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, the Philippines and Thailand to fight alongside the Americans in Vietnam. However, the only part of this multinational coalition that the news media paid attention to were the Americans; since then the world has forgotten the involvement of the others. After the war ended SEATO no longer had a reason to exist, and it was dissolved by the mutual consent of its members.

In Vietnam the US wanted a government that was both respectable and anticommunist. But true nationalists outside the ranks of the Viet Minh were hard to find in 1954. Many had been killed by the communists or the French; others withdrew from politics or emigrated from Vietnam altogether. Into this vacuum stepped Ngo Dinh Diem, and Americans saw him as the savior Vietnam needed.

At first Diem had a lot of personal qualities in his favor. He came from an upper-class family, giving him an air of sophistication that appealed to many important Americans, including Senator John F. Kennedy. He was a certified patriot who had never collaborated with either the French or the Japanese. He also hated the communists, who killed one of his brothers and forced him to live abroad from 1950 to 1954. Last but not least, he was a pious Roman Catholic; his eldest brother, Ngo Dinh Thuc, was the Archbishop of Hue. Catholic Vietnamese, who made up a tenth of the population, looked to Diem for leadership and protection; he responded by trusting few others.

In 1954 Bao Dai appointed Diem prime minister of South Vietnam, hoping that his presence would keep American aid flowing into the country. For a year the playboy and the puritan made an odd couple. Bao Dai thought he was using Ngo Dinh Diem, but the tail was strong enough to wag the dog. First Diem had a showdown with his rivals in Saigon. In a brief but violent battle that left between 500 and 1,000 people dead and about 20,000 homeless, the South Vietnamese army crushed the Binh Xuyen gang and brought the militant Cao Dai and Hoa Hao sects into line. Next, Diem sent troops out into the countryside to root out any communists that might still be there. In October 1955 Diem held an election to determine whether the South Vietnamese people wanted a monarchy or a republic, rigged it to give the republican choice an overwhelming victory, deposed Bao Dai, and declared himself president.(1) As Diem brought stability and security, he gained the praise and admiration of American officials, who hailed him as the "miracle man" of Asia. At this stage he was at the peak of his career; afterwards his many failings would cause him to make grave errors, with violent consequences.

The first error was probably unavoidable, in view of the circumstances. The 1954 Geneva accords had promised elections to reunify Vietnam by July 1956. Diem, with US approval, never allowed the elections to be held. He had his reasons. The population of North Vietnam was larger than that of South Vietnam, and Diem had no control over the voting that took place north of the 17th parallel, so Ho Chi Minh was likely to win a nationwide vote. His decision may have been sound, but it was the spark that touched off the Second Indochina War. In 1957 communist guerrillas started sneaking across the DMZ, where they recruited followers among Diem's opponents and oppressed peasants. Then they opened up a campaign of terrorism against members of the Saigon regime. Three years later North Vietnam organized them into the National Liberation Front. Saigon called the guerrillas the Viet Cong, meaning Vietnamese Communists, and the name stuck.

In his presidential palace, Diem tried to minimize the threat. He did not want to offend his American patrons by letting them know the problem was greater than they thought it was. Likewise, his subordinates swept the bad news under the rug because they were afraid of reporting it openly. Had Diem been a popular leader, he might have gained the upper hand against the Viet Cong eventually. But only friends, relatives and Catholics gave their unquestioned support; instead of seeking the goodwill of the rest, he lorded over them like an emperor, refusing to give them a voice in government or even to meet with them (he only made trips outside of Saigon when his American advisors told him it was good politics to do so). As the military situation deteriorated, he turned for guidance to his half-mad brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, and to Nhu's beautiful, venomous wife.(2) When foreign correspondents came calling he would meet with them for five or six hours, leaving other visitors and the country's problems waiting outside. During those interviews he gave marathon monologues on "personalism," an authoritarian ideology he invented that emphasized submission to the head of state as the solution to every problem. It was an unappealing philosophy that few people could even understand. Communist propaganda played on Diem's foreign dependency by linking Diem's name to that of America with a hyphen. Yet there was no way South Vietnam could rid itself of the Americans without losing the vital support that was needed more with each passing day.

In Washington, President Eisenhower tried to ignore Vietnam. His successor, Kennedy, sent military advisors, and then increased their numbers steadily. In 1961 400 US troops arrived to operate helicopters; one year later there were 11,200 US servicemen in Vietnam; by the end of 1963 there were 15,000. American advisors also took special interest in the non-Vietnamese hill tribes that lived in South Vietnam's rural areas. These folks called themselves the Degar; to the French they were Montagnards and to the Vietnamese they were Nguoi Thuong (both names mean "Highlanders" or "Mountain Men"). Whatever the name, these people did not get along well with the Vietnamese (some of them were descended from people who lived in Champa, Vietnam's ancient rival), and in 1958 they formed a political movement, with the intention of gaining autonomy for their tribes. In the early 1960s the hill tribe population was estimated at one million, and the Americans succeeded in recruiting, training and equipping 40,000 of them, to fight alongside themselves and the South Vietnamese army (ARVN, or the Army of the Republic of Vietnam).

Despite the increased American assistance, victory was no closer than it had been before. But there could be no turning back now. The United States had announced in no uncertain terms that it would stop the spread of communism, and now was committed to do that, no matter what the cost. Withdrawal was unthinkable--it would cost the US too much prestige--and no American president wanted to be responsible for losing a war. Already Americans were getting involved in firefights between South Vietnamese and the Viet Cong, but it was rarely reported in the news; the casualty counts were too low for the average American to care anyway.

Diem tried to cut off the Viet Cong's base of support by moving the peasants into fortified settlements called "strategic hamlets." The idea had worked against communist guerrillas in Malaya a few years earlier, but it was too badly planned to work here. The peasants resented having to walk long distances to their fields and ancestral burial grounds. The money promised to them when they moved often disappeared into the pockets of corrupt officials, as well as money earmarked for seed, fertilizer, irrigation, medical care, education, and sometimes even weapons. Frequently the hamlets were thrown together in such a slapdash fashion that Viet Cong agents remained inside, acting as informers for their comrades. The long-term result of the program was that it drove many neutral peasants into the arms of the Viet Cong.

The end of Ngo Dinh Diem came when he alienated both the Buddhists and the military. On May 8, 1963, Buddhists assembled in Hue to celebrate the 2,527th birthday of Buddha, and a local Catholic official prohibited them from flying their multicolored flag. Only a week earlier Catholics had waved blue and white papal banners to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the ordination of Ngo Dinh Thuc. The Buddhists protested against this form of discrimination, and in the demonstration that followed, government troops opened fire, killing a woman and eight children. While Diem tried to blame the trouble on the communists, the Buddhists organized an opposition party. One month later they burst a bombshell. A monk in Saigon drenched his robes with gasoline and burned himself to death, his hands fixed in an attitude of prayer. A shocking photo of the immolation appeared on the front pages of newspapers everywhere the next day. While world opinion turned against the Diem regime, Madame Nhu responded with a sick joke: "If the Buddhists wish to have another barbecue I will be glad to supply the gasoline and a match."

As more monks went up in flames, Washington decided that Diem was a political liability that had to be replaced if South Vietnam was not going to be lost to communism. Before this time there had been two attempts on Diem's life by members of the military, both failing because the other troops stayed loyal to the president. On the third attempt the anti-Diem generals got almost all of the armed forces on their side; the US ambassador and a CIA agent gave them the signal to go ahead by hinting that US aid would not stop should the coup succeed. On November 1 the army attacked the presidential palace. Diem and Ngo Dinh Nhu went into hiding for a day, then gave themselves up in return for safe conduct out of the country. They boarded an armored car that was provided for the journey. Exactly what happened next is uncertain, but both of them were dead from gunshot wounds when the car arrived at staff headquarters. Three weeks later Kennedy was also assassinated. With new governments running both the US and South Vietnam, a new phase in the Vietnam War was about to begin.

|

|

The Eisenhower administration was more concerned with Laos than Vietnam. Laos had strategic value because it shared a common border with China, North and South Vietnam, Cambodia, Burma and Thailand. From 1955 to 1958 communists, anticommunists and neutral royalists tried to make their coalition government work, but it only succeeded as long as no faction gained enough power to control the government by itself. When the 1958 elections gave 13 of the 21 contested seats to the Pathet Lao, the right reacted by forcing the neutral prime minister, Prince Souvanna Phouma, out of office, and replacing him with their own candidate, Phoui Sananikone. Then in 1959 the rightists accepted US aid, which violated the Geneva agreement, and imprisoned the "Red Prince", Souvanouvong (he escaped a year later). The Pathet Lao retaliated by seizing Phongsali and San Nua, the capitals of the two provinces they were based in. When Phoui showed signs of moving towards a neutralist position, he was deposed by rightist army officers and replaced by one of their own, General Phoumi Novosan. The situation got more complicated when a young paratroop commander, Captain Kong Le, rebelled in 1960, captured Vientiane, the administrative capital, and brought Prince Souvanna Phouma back to power. Souvanna tried to form another coalition government that included leftists, but Phoumi refused to submit, and ordered the army to attack the neutralists. Souvanna was forced to flee the country, leaving behind a fervently anticommunist government, backed by the US. Kong Le led his troops over to the side of the Pathet Lao, and by May 1961 the whole eastern half of the country was under Pathet Lao control.

At this point a second Geneva conference was held to resolve the situation in Laos. All sides agreed that Laos should be a neutral state, with a coalition government that included all factions. Souvanna Phouma became the prime minister again, with Souvanouvong and Phoumi as his deputies. This system lasted for two years, and collapsed when the neutralists split. The neutralists with left-wing sympathies switched their allegiance to the Pathet Lao, while those remaining, including Souvanna, joined forces with the rightists. War resumed, and this time it was tied to the conflict being fought next door in Vietnam.

With North Vietnamese help, the Pathet Lao were increasingly successful. They took over the strategic Plain of Jars and large portions of the countryside, leaving only the Mekong valley and the two capitals (Luang Prabang and Vientiane) firmly in government hands. North Vietnam constructed a network of jungle paths in the east, known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and they became the main supply line for communist forces in South Vietnam. On the government side, Thai mercenaries and Hmong tribesmen, trained and financed by the US, were involved in the fighting. American planes flew bombing missions over Pathet Lao territory daily. In 1971 South Vietnam made an unsuccessful invasion to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail. By this time all sides were tired of a conflict that went on and on, with no clear victory in sight for anybody. A cease-fire was signed in the fall of 1973, and one more coalition government was established.(3)

Indochina from 1954 to 1975. The red arrows mark the path of the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

|

|

|

|

Bad as Diem was, his successors were worse. The generals who succeeded him were total incompetents, who spent more time fighting each other than the Viet Cong. In the year and a half following Diem's assassination, South Vietnam had ten different governments. The chaos in Saigon was matched by increasing Viet Cong success in the countryside; by late 1964 everything outside the cities was effectively under their control. Political stability started to return when Air Vice Marshall Nguyen Cao Ky seized power in 1965; he ruled for two years, until elections replaced him with General Nguyen Van Thieu. The governments of Thieu and Ky were so corrupt that one White House staff member called them "the bottom of the barrel, absolutely the bottom of the barrel."

The new US president, Lyndon B. Johnson, realized that just sending aid to Saigon was not enough; America would have to get directly involved in the fighting to save a country that could not save itself. In August 1964 North Vietnamese torpedo boats fired on a destroyer cruising in the Gulf of Tonkin. Following this incident LBJ asked Congress for, and got, a blank check to act in Southeast Asia as he saw fit. He started by launching bombing raids against North Vietnam; in March 1965 the first US marines came ashore at Danang.

The first American combat troops were too few to turn back the communists, so by the end of 1965 their numbers were increased to 200,000. American economic power came to South Vietnam as well. Overnight Saigon and the sleepy towns along the coast became bustling centers of activity as navy and air bases were built. Saigon was flooded with every luxury or necessity the troops could ask for, including guns and ammo, oil, spare parts, sports clothes, cameras, radios, tape recorders, soap, shampoo, deodorant, razors, and, of course, condoms. Every form of weapon in the American arsenal, except nuclear warheads, was brought over for field testing. Ho Chi Minh had once described his war against the French as a struggle between "grasshoppers and elephants"; now he was a germ facing Godzilla.

Modern helicopters were invented during the 1940s, and the Second Indochina War was the first conflict that used helicopters much. Here Bell UH-1D helicopters airlifted members of the US 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment from the Filhol Rubber Plantation area to a new staging area, during "Operation Wahiawa", a search and destroy mission conducted by the 25th Infantry Division, northeast of Cu Chi, South Vietnam, in 1966.

America considered itself unbeatable, and expected the war to end in a quick victory. But this kind of warfare was quite outside the American experience. Many books, discussions, etc. have tried to figure out why America could not defeat a third-rate power. Some of the reasons are listed below:

1. The enemy was not an obvious villain. The Viet Cong rarely wore uniforms; their ranks included women and even children.(4) Any civilian could be an enemy, and before long many Americans wondered if they were fighting on the right side. Americans also found it hard to hate the enemy completely because Ho Chi Minh was not a Stalin or a Hitler; he looked more like an Oriental Santa Claus to them.

2. The war was not a conventional conflict, with shifting front lines and armies on the move. Progress here was not measured in territory gained but in the number of casualties inflicted. Time and time again Americans would chase the Viet Cong away from one spot, only to see the Viet Cong come back after the Americans had moved elsewhere. In a war without frontiers, the Americans lived under constant danger, no matter where they were.

3. Heat, disease, leeches, tigers (yes, tigers!), and fiendish Viet Cong traps; in the jungle these put as many men out of action as the actual firefights did. An enemy soldier might spare you if he is in the mood, but nature takes no prisoners.

4. The ineffectiveness of bombing. For most of the time between 1965 and 1968, and twice in 1972, American B-52s flew daily bombing missions over North Vietnam. Ultimately North Vietnam would get pounded with triple the bomb tonnage that was dropped everywhere during World War II. But there are few targets worth hitting in a pre-industrial country, and casualties were limited; civilians were protected by putting them in underground tunnels or by moving them out to the countryside. The Ho Chi Minh Trail was also bombed, but the Viet Cong carried so little gear that their entire force could keep fighting even if only 15 tons of supplies got to them daily. Whatever could not be manufactured locally was generously given by both Russia and China. Targets that could have done real harm if hit, like the heavily populated residential neighborhoods of Hanoi, were carefully avoided; LBJ thought if he hit North Vietnam too hard, it would trigger Chinese or Russian intervention, and that would be the beginning of World War III. The US never attempted an offensive strategy--like an invasion of North Vietnam to topple Ho Chi Minh's government--for the same reason.

5. Speaking of aircraft, the North Vietnamese had a surprisingly effective air force. I say "surprisingly" because the first North Vietnamese squadron was only assembled in 1964, and a year later they won their first battle, one that pitted eight North Vietnamese planes against seventy-nine American ones. In that encounter, the North Vietnamese pilots were flying hand-me-down Soviet MIGs that were out of date, but still they managed to shoot down two American planes. Over the course of the war, the North Vietnamese lost 131 planes, while the Americans lost more than 2,000; seventeen North Vietnamese pilots had enough kills to become aces, compared with only three American aces. This isn't just beginner's luck; away from Vietnam, only the American, Soviet and Israeli air forces have done better! In fact, the Americans were so embarrassed at the North Vietnamese performance that they did not talk about it until long after the war.

6. The role of the US press. At first the media supported the war effort, but soon many editors were having second thoughts. In 1967 LIFE Magazine brought the reality of the war home to readers by printing names and high school photos of the 250 young Americans killed in a single week. The television news programs also showed a point of view that was not pro-American, by interviewing North Vietnamese/Viet Cong leaders and by showing pictures of wounded Americans and atrocities committed against civilians, like the notorious My Lai massacre. The actual effect of all this on American morale has been debated ever since.

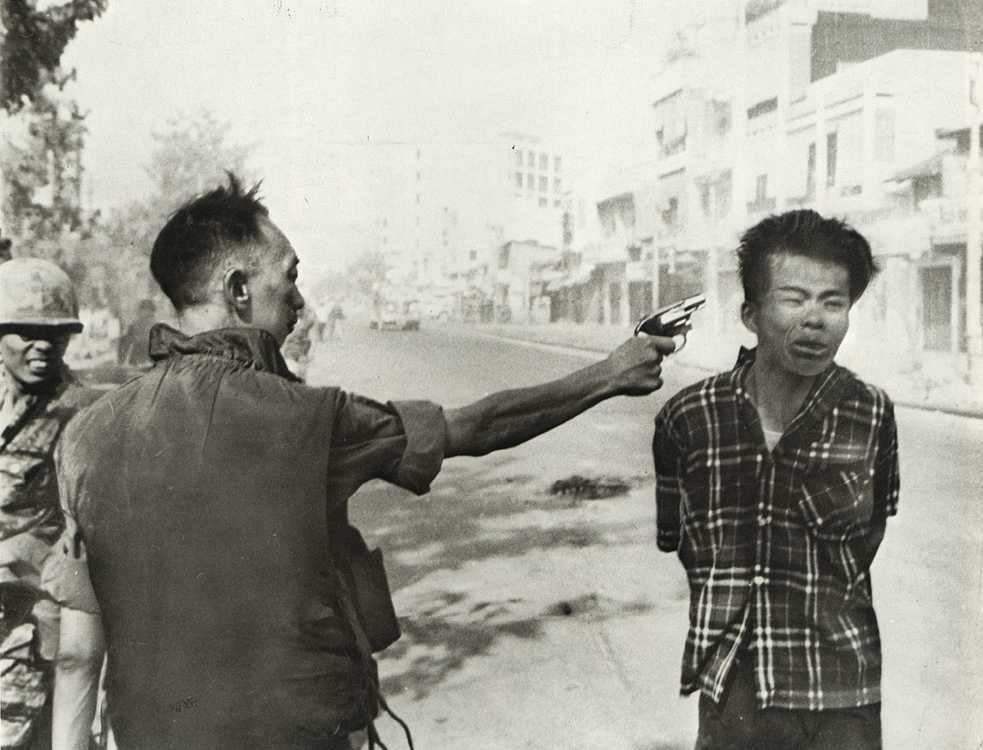

"It says something about this war that the great picture of the Tet Offensive was Eddie Adam's photograph of a South Vietnamese general shooting a man with his arms tied behind his back, that the most memorable quotation was Peter Arnett's damning epigram from Ben Tre, 'It became necessary to destroy the town to save it' and that the only Pulitzer Prize specifically awarded for reporting an event of the Tet [sic] offensive was given two years later to Seymour M. Hersh, who never set foot in Vietnam, for exposing the U.S. Army massacre of more than a hundred civilians at My Lai."(5)

The photo mentioned in the previous paragraph. When a Viet Cong prisoner was brought before Nguyen Ngoc Loan, South Vietnam's chief of national police, Loan executed him without hesitation, in front of NBC cameras.

7. America underestimated the breaking point of the communists, and overestimated its own. The Vietnamese had fought wars that lasted for centuries, and the Communist Party provided the discipline and coercion needed to withstand the war with America. America, on the other hand, had never fought a war that lasted this long, and it did not have the willpower to fight an unpopular war for generations. It has been said that the Americans won every battle in Vietnam, but they lost the war in America.

When the Americans did not win a decisive victory, it was reasoned that more force was needed, so more men, more bombs, and more equipment were shipped in. But the enemy was just as capable of moving in reinforcements, a move which forced the US to make an even larger commitment just to maintain the present situation. This process of escalation continued until 1969.

In January 1968 the communists launched an astonishing wave of attacks on Tet, the Vietnamese New Year's Day. Because both sides had agreed to a truce for that day, the Americans and South Vietnamese were taken completely by surprise. The previous year had seen several American victories, causing the Americans to believe that the Viet Cong were too beaten to stage an attack. Instead, Viet Cong guerrillas went on a rampage in every city, and even the US embassy was attacked. When the US and South Vietnam struck back, it was with unprecedented fury. The fiercest battle was fought over Hue, which communist units held for 25 days, committing ghastly atrocities while they were there.

The purpose of the Tet offensive was to win the war while Ho Chi Minh was alive (he died of old age a year later). From a military standpoint, it was a failure; the communists gained almost no territory and suffered frightful casualties. The victory they won was a psychological one. American morale was broken, and now the main desire of the US was not to win, but to get out. As opposition to the war mounted, the Johnson administration crumbled, and Richard Nixon won the 1968 presidential election by promising to end the war. Peace talks between American and North Vietnamese diplomats were already in progress by the time he took office.

Vietnamization and the Cambodian Diversion

|

|

|

|

|

American involvement in Vietnam peaked in the spring of 1969, when 543,000 US servicemen were in the country. Gradually they were withdrawn, and the burden of the war was shifted to the unsteady shoulders of the ARVN, in a process the Nixon administration called "Vietnamization." Great efforts were made to train and equip the South Vietnamese so that they could hold the communists on their own. As the 1970s began they recovered much Viet Cong territory, and South Vietnam's future began to look secure at last.

1970 was a bad year for everybody. The Viet Cong were badly mauled by the Tet offensive, ARVN, and a CIA operation called the Phoenix program, which had killed or captured thousands of them. The North Vietnamese defense minister, Vo Nguyen Giap, replaced the losses by bringing in northern regulars, changing a guerrilla war into a more conventional conflict. But America and South Vietnam did not profit from these setbacks. In fact, antiwar sentiment in the US was greater than ever, forcing Nixon to make the troop withdrawals ahead of schedule. The peace talks were getting nowhere in Paris. And then there was Cambodia.

Prince Norodom Sihanouk, the mercurial Cambodian ruler, played a dangerous game for 17 years to keep his country neutral. At first in the 1950s he bid for American protection. But America had stronger ties with Cambodia's historical foes, Thailand and South Vietnam. Because of that, he gradually shifted toward China and broke the American connection completely. Now he expected the communists to prevail in Vietnam, so he allowed them to build bases and extend the Ho Chi Minh Trail through Cambodia; he also counted on China to keep the Vietnamese from violating his sovereignty. Then late in 1967 he reversed his decision again, by telling US officials he would grant them right of "hot pursuit" against the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong in Cambodia--as long as no Cambodians were harmed. Sihanouk's flip-flop behavior made him enemies on both the right and the left. The right included a small pro-democracy, pro-US group called the Khmer Serei (Free Khmer), the army, and many who simply wanted a share of the merchandise America was dumping on Bangkok and Saigon. On the left were Cambodian students, many of them educated abroad, who resented Sihanouk's intolerance of radical dissent. As the economy deteriorated in the late 1960s, due to bad planning, Sihanouk lost the support of everybody but the peasants, who still saw him as a god-king. In 1968 a Cambodian communist movement called the Khmer Rouge (Red Khmer) started a guerrilla war in the remote areas of the country.

Here we will tell the early story of Saloth Sar, one of the leftist students. Born in 1925 or 1928, he came from a small fishing village, but his family did well by Cambodian standards; a sister was a concubine of King Sisovath Monivong (Sihanouk's grandfather), and a brother was a court official. In 1949 he won a scholarship to go to college in Paris, where he joined a group of Cambodian Marxist students, the Cercle Marxiste. Saloth Sar came back in 1953, after failing too many exams, and soon after that, he and his classmates founded the Khmer Rouge. From 1956 to 1963, Saloth Sar led a double life. By day he was a professor at Chamraon Vichea, a private college in Phnom Penh, where he taught French literature and was much liked by his students; by night he plotted to replace the monarchy with a communist government. When Sihanouk began cracking down on leftist political movements, the oldest dissidents were arrested, allowing Saloth Sar to become leader of the Khmer Rouge in 1963. Then, to avoid being arrested next, Saloth Sar disappeared without a trace. He fled into the jungle, changed his name to Pol Pot, and cut all ties to everyone outside the Khmer Rouge who knew him, so his friends, relatives and students had no idea what happened, and assumed he was dead. About fifteen years later, they would find out he was the monstrous dictator who had taken over their country (see the next chapter). So if you are a student and your teacher is absent from school quite often, you have a good reason to be concerned.

Washington had long regarded Sihanouk as a royal pain in the neck. It is uncertain whether the US was involved in his ouster, but US intelligence services certainly knew what was going on. It came in March 1970 when Sihanouk went to France for medical treatment. The two men who ran Cambodia in his absence, General Lon Nol and Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak, ordered the Vietnamese communists out of the country, and soon the Cambodian people were running amok, rioting and killing any Vietnamese they could find, in an explosion of ethnic hatred. Before Sihanouk could return, Lon Nol deposed the prince, declared himself president, and renamed Cambodia the "Khmer Republic." Sihanouk moved to China, and joined his former enemies, the Khmer Rouge, and became their figurehead leader.

In April Lon Nol broadcast a desperate appeal for aid against the communists. America already had a plan to intervene. Within a week a force of 20,000 Americans and South Vietnamese were in Cambodia, going after the communist bases there. The invasion did not last long--massive anti-war protests that threatened to tear the US apart made sure of that--and once it was over the Khmer Rouge went on the offensive, capturing the eastern half of Cambodia within months. Now the Nixon administration found itself supporting a corrupt regime in Phnom Penh as well as in Saigon. American bombers pounded the Khmer Rouge until August 1973, when the bombing missions were discovered and ordered stopped by the US Congress. By that time nearly 80% of the country was controlled by the Khmer Rouge, and all of Cambodia's cities, including Phnom Penh, were under siege. Since nobody tried to make a peaceful settlement, a Khmer Rouge victory was only a matter of time.

Nixon had promised to "end the war and win the peace." But during his first term in office he seemed to go in the opposite direction, spreading the war to every corner of Indochina. Peace finally came during his second term, but it was peace on the terms of the communists.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the spring of 1972 North Vietnam launched a second offensive, this time with mainly conventional forces. Like the Tet offensive, this assault eventually ran out of steam, but before it did one fourth of South Vietnam's land and 15% of its people were captured. The main battle was fought in the northernmost provincial capital, Quang Tri, which the communists held for four and a half months before ARVN forces retook it. The last American soldiers were leaving Vietnam at this time, so the United States did not get involved in the fighting.

At the same time, the United States was improving relations with China and the Soviet Union. The Vietnam War kept getting in the way of the agreements they were signing, so Washington, Moscow and Beijing all looked for ways to make the war go away.

The peace talks had been stuck for years on issues that neither side would compromise on, like whether the North Vietnamese should withdraw to their side of the DMZ, the role of Thieu and the Viet Cong in the postwar government, etc. Now the major powers increased pressure on both Hanoi and Saigon for a diplomatic solution. China and the USSR refused North Vietnamese requests for more aid, and the US threatened to cut off aid to Thieu unless he made peace as well. The real breakthrough came when both sides agreed to a partial settlement; in effect what they said was, "Just stop the fighting now and we'll take care of the rest later."

The cease-fire agreement, signed in Paris on January 27, 1973, had serious flaws from the start. First, the North Vietnamese were permitted to keep 145,000 troops in South Vietnam. Neither side tried very hard to keep the peace, and violations of the agreement occurred daily, growing into major battles by 1974. US bombing of Hanoi and Haiphong reached its peak just a month before the cease-fire was signed, leading some to believe the communists were forced to sign an agreement they didn't really want. Most of all, it was the same sort of partial solution that had hindered the 1954 Geneva accord; once a military solution was reached, a political solution was expected to come and bring about real peace, and when it did not come, a renewal of the war became inevitable. And when the conflict did begin again, America was out of the game. North Vietnam's premier, Pham Van Dong, stated that only American troops could keep the north from winning, and, he joked, "They won't come back even if we offered them candy."

Hanoi expected the war to go on at least until 1976. Hence, when an experimental thrust in December 1974 captured a provincial capital only about 75 miles from Saigon, the success amazed even the communists. A second attack in March 1975 took another provincial capital, Ban Me Thuot in the central highlands, and the whole South Vietnamese defense collapsed. As the ARVN retreated to the coast, they were joined by more than a million refugees, and the retreat became a rout. Hue and Danang were surrounded and captured, and the North Vietnamese advanced southward, taking the rest of the coastal cities one by one. Only at Xuan Loc, 35 miles northeast of Saigon, could the ARVN put up any resistance; there in mid-April the ARVN 18th Infantry Division held off two North Vietnamese Army Corps, a force ten times larger, for twelve days. That was the South Vietnamese Army's last stand.

President Thieu resigned and went abroad with a fortune in gold, and he was followed by the Americans, who hastily closed the US embassy and bases before they left. About 130,000 lucky Vietnamese refugees managed to get out with the Americans, beginning the exodus of "boat people" that continued for the rest of the 1970s and 80s. On April 30, 1975, North Vietnamese tanks entered Saigon and knocked down the gates of the presidential palace; the government surrendered, and the victors promptly renamed the southern capital Ho Chi Minh City. The war which had cost 58,000 American lives, 1.3 million Vietnamese lives (both soldiers and civilians), and $189 billion in US dollars was finally over. And the result--Vietnam united under communist rule--was exactly the same as what many thought would happen, if the 1956 elections had taken place.

The end of the war in Vietnam also brought about an end to non-communist regimes in Cambodia and Laos. Two weeks before the fall of Saigon, the long siege of Phnom Penh ended. Like Thieu, Lon Nol went into self-imposed exile, leaving the rest of his government to surrender to the Khmer Rouge(6). In Laos, the 1973 cease-fire looked like it would become a permanent peace, but when they heard the news from Cambodia and Vietnam, the rightists in the Laotian cabinet lost their confidence, quit, and fled the country (May 1975). Thus, the Pathet Lao took over the government without firing a shot. Taking their time after that, the Pathet Lao moved into Luang Prabang in June, and Vientiane in August. In December the last king, Savang Vatthana, was deposed, and the country was renamed the Lao People's Democratic Republic. The Pathet Lao leader, Prince Souvanouvong, was merciful to his defeated enemies, since they were in fact his relatives. While the king died in captivity at an uncertain date, former prime minister Souvanna Phouma was allowed to serve as an advisor, once he learned communist ways. The Cambodian people were not so lucky; for them the worst part of their ordeal was about to begin.

Malaysia and Singapore Get Organized

So far in this chapter we have only discussed Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. The rest of this chapter will cover what the other Southeast Asian nations were doing, while Indochina was making headlines.

Once Malaya became independent, the future of the last British colonies in the region (Brunei, Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore) was re-examined. With India and the Suez Canal gone, it seemed pointless for Britain to hold on to pieces of its once-great empire, but what should be done with the colonies was not clear. Local politics decided the issue differently in each one.

Singapore had a dynamic nationalist movement, the People's Action Party (PAP). It developed so quickly in the postwar years that it was sharing rule of the city with the British by 1948. When the PAP gained full authority over local affairs in 1959, Singapore's colonial era was all but over. A Malayan state without Singapore in it looked a little odd, but the Tengku of Malaya wanted nothing to do with the busy port. The reason was racial; the Malays still feared drowning in a sea of Chinese. Malaya was successful because its Malay, Chinese, and Indian communities had carefully worked out a system that clearly spelled out what each group could have. Singapore's population was 76% Chinese, enough to upset the balance and turn Malaya into a new Chinese state if the city was included in the federation.

In 1961 the Tengku astonished the public by reversing his stand and proposing the union of Malaya and Singapore into one state. His reasoning was that an independent Singapore, with a leftist or socialist government, would pose a greater danger to Malaya than the incorporation of the island into an expanded Malayan state. The mayor of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, accepted the proposal, since he did not think the city could stand on its own. After negotiations and a plebiscite, Singapore joined Malaya in 1963.

The three territories on Borneo presented different problems. The tribes that lived in the interior of the big island did not get along well with the Malays living on the coast, but they were too primitive to go it alone, so union with Malaya seemed inescapable. The local politicians were won over by promises to protect their interests, so in August 1963 Sarawak and Sabah were united with Malaya to create a new nation, called Malaysia. To resolve the issue of how the people of Borneo felt about union, a UN fact-finding team went to Sarawak and Sabah; to nobody's surprise, it reported two months later that virtually everyone approved of the merger.

Brunei was also supposed to become a part of Malaysia, but the sultan of that tiny state balked at the prospect. A year earlier, there was an unsuccessful revolt that made him nervous about losing British support. He also had much to lose if he joined Malaysia's royalty club. If he was placed at the back of the line in Malaysia's rotating monarchy, he might have to wait as long as 45 years before he could take his turn as king of the whole country. Finally Brunei has sizeable oil reserves, the profits of which would have to be shared if Brunei was part of another country. In short, Brunei was peaceful and prosperous under British rule, and chose to remain that way for another twenty years.

The birth of Malaysia was denounced by Indonesia and the Philippines, both of which have ethnic Malay populations. The Philippines resurrected an old and dubious claim to Sabah; Sukarno claimed all of Borneo and denounced Malaysia as a "neo-colonial" idea. Between 1963 and 1966 Indonesian guerrillas infiltrated Sarawak and Sabah, while thousands of regular troops massed along the borders. Military aid from Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand kept Malaysia alive during this critical period, now known as the "Malaysian Confrontation." After Sukarno fell from power Malaysia and Indonesia quietly ended the conflict, which was getting both of them nowhere.

Philippine president Macapagal proposed uniting all three nations into a Malay superstate called "Maphilindo," but Malaysia and Indonesia didn't care for the idea. More successful was the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, an organization founded in 1967 to promote cooperation between the pro-Western countries in the region. The original five members of ASEAN were Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Singapore. Thus, ASEAN acted like an economic version of SEATO until other nations joined it.

The ASEAN flag.

Despite the best of intentions, Singapore remained a part of Malaysia for only 23 months. During the 1964 elections Lee Kuan Yew tried to extend his influence by sponsoring nine candidates for parliamentary seats that represented the mainland, not Singapore. Only one of them won, while the Alliance maintained power by winning 89 seats. Lee could not get along with the Alliance leaders after that, so with their consent, he exercised his right to secede on August 9, 1965.

As it turned out, both Malaysia and Singapore were better off without each other. Because the Malays are still mostly farmers, most of the profits from the tin and rubber industries go to the Chinese and Indians instead. In 1968 the government announced a rural development program, called the New Economic Policy (NEP), in the hopes of raising the Malay standard of living to a level closer to that of the Chinese and Indians. The government also continues to discriminate in favor of the Malays for the same reason; for example, the civil service is required by the constitution to hire four Malays for every non-Malay hired. The Tengku retired in 1970, and his successors have maintained Malaysia's ethnic, economic and political balance to this day. The only time it threatened to fail was after the 1969 elections, when bloody riots against the Chinese and Indian communities killed at least 200. The government declared a state of emergency, which lasted until 1971; Parliament did not meet during that time.

The new prime minister, Tun Abdul Razak, broadened the Alliance into an organization called the National Front, which included some opposition parties. The National Front won the 1974 elections decisively and also, under Prime Minister Datuk Hussein Onn, the 1978 elections. Ethnicity, however, still dominated the political scene, and two major opposition parties opposed the National Front: the Pan-Malayan Islamic Party and the Democratic Action Party. When Hussein Onn retired in 1981, he was succeeded by his deputy, Mahathir bin Muhammad.

Burma: A Ne Win Situation

The anti-Western feeling in independent Burma was so strong that it rejected capitalism and tried to build the country along socialist lines. Both U Nu and his successor, General Ne Win, developed a national policy by combining socialism, Buddhism, and isolationism, calling it "the Burmese Way to Socialism." U Nu's main accomplishment was a Buddhist revival. From 1954 to 1956 he hosted the Sixth World Buddhist Council, the first international convention of Buddhist monks and scholars held in nearly a century. He traveled abroad often and became a respected spokesman for the Nonaligned Movement. Refusing to take sides in the Cold War, he attempted to serve as an intermediary between East and West, and was judiciously fair in his dealings with other countries; for example, Burma was one of the first nations to recognize both Israel and Communist China. In the countries that were divided by the Cold War (Germany, Korea and Vietnam), he refused to send diplomats to either side. U Nu's greatest diplomatic triumph was good relations with China; in 1960 he signed a treaty of friendship with China's Zhou Enlai and settled a border dispute that had bothered both countries for much of the 1950s. Another statesman that made Burma look good to the rest of the world was U Thant, the secretary general of the United Nations from 1961 to 1971.

On domestic issues, however, U Nu was only a mediocre leader. The economy never recovered to its pre-World War II levels, and he had to postpone indefinitely his plans to make Burma the first welfare state in Asia. In 1954 he proposed a constitutional amendment making Buddhism the state religion, a move that offended the country's Christian and Moslem minorities. To placate them he offered equal time for the teaching of all three religions in the schools. That caused so much trouble from the monks that he banned all religious instruction, a move that caused demonstrations all over the country. He was forced to capitulate and allow only Buddhist instruction; one observer commented that he became a victim of the very sentiments that, as a patron of Buddhism, he had fostered.

In 1958 the AFPFL split into two factions, known as the "Clean" AFPFL and "stable" AFPFL. The Shans were also threatening to secede, now that the ten-year waiting period they had promised Aung San was over. Faced with losing control over the country, U Nu turned to General Ne Win for help. For the next 18 months Ne Win led a caretaker government that put Burma's house back in order. At the end of that time new elections were held, and Ne Win returned the government to civilian rule. Once U Nu was back, however, the old problems came back with a vengeance. This time Ne Win did not wait for permission to take over. In March 1962 he arrested U Nu, scrapped the constitution, dismissed Parliament, and ruled by decree. The disorderly AFPFL was replaced by the Burmese Socialist Program Party (BSPP), which now became the only legal political party in the land.

Burma under the BSPP experienced one-man misrule. Ne Win imposed socialism more aggressively than U Nu did, by nationalizing all land, commerce and industry. Rice marketing was made a government monopoly and peasants were paid less than a third of the market value for their crop. Ne Win also had a puritanical streak; he closed dance halls, prohibited beauty contests and horse racing, and insisted on punctuality and industriousness. Such behavior did not go over well with the easygoing Burmese, and the economy went from bad to worse. Per capita income sank from $670 in 1960 to a low of $200 in 1989 (it is $1,144 as of 2012), and most of the population practiced subsistence farming to avoid starvation. Once the world's largest exporter of rice, Burma stopped exporting rice in 1973; now it is known as the world's second largest grower of the opium poppy. The country is rich in farmland, teak, rubies, even oil, but is classified as the poorest nation of Southeast Asia, and one of the poorest nations in the world. Most homes are bamboo huts; electricity is a rarity; buildings seem to crumble before one's eyes. Keith Laumer, a former US diplomat stationed there in the 1950s, described Rangoon this way a generation later: "Once the garden city of the East, now the garbage city of the East."

Before Ne Win took over, Burma had isolationist tendencies; under him they became downright xenophobia. Few countries were harder to get into. In the 1960s tourists were not allowed to stay in Burma for more than 24 hours--this was extended to one week in 1970, so that tourists could visit places outside of Rangoon. Burma even quit the Nonaligned Movement that it helped get started, charging that the 1979 meeting hosted by Cuba's Fidel Castro was tainted by superpower politicking. Ne Win locked out the modern world everywhere; under him Burma had no high-rises, nightclubs, or neon signs; even Coca-Cola was unknown. Offices kept their records in nineteenth-century style ledgers, because they couldn't get typewriters. No new cars were available after U Nu was ousted, and the Burmese became mechanical geniuses when it came to maintaining the cars they had.

If all Ne Win did was oppress the people and make himself rich, we'd be done talking about him now; most dictators do that, after all. However, he was also superstitious, and he let it affect national policy. We saw in the previous chapter that Burmese politicians consult astrologers and soothsayers (they decided the date for the country's independence, remember), but the BSPP kept a Board of Astrologers -- an actual government agency! -- and Ne Win heeded their advice, even when it was insane. He would cross bridges backwards to protect himself from evil, and one report asserted that he bathed in dolphin's blood, because he believed it restored youth and energy. When he grew concerned that his regime was leaning too far to the left (that's to the left politically, meaning pro-communist), his soothsayers told him that was because the Burmese, like their former British masters, drove on the left side of the road. So to compensate for that, Ne Win suddenly ordered everyone to drive on the right from now on, though their vehicles and the roads weren't set up to handle the change in traffic. On the day that law went into effect, Burma experienced a country-wide demolition derby. Even today, because of Burma's long-term isolation, most cars still have their steering wheels on the right side, and most busses have doors on the left side, meaning that drivers have large blind spots behind them, and passengers have to dodge traffic while getting on or off a bus.

To make sure that Burma's population would never be absorbed into one of its two big neighbors, India and China, he outlawed all forms of birth control. In case you're curious how that worked, the Indians and Chinese outnumbered the Burmese by nearly 47 to 1, so the Burmese mothers could never catch up.

There weren't many things the Ne Win regime did well, but putting down dissent was one of them. In 1974 student strikes erupted at the funeral of U Thant, an old rival of Ne Win, and the students were put down so forcefully that scarcely a murmur of dissent was heard for a decade. Ne Win was less successful in dealing with the various rebels (mostly Karens, communists and opium warlords) on the periphery of the state, but since they were too weak to threaten Rangoon, most of the country enjoyed peace.

Indonesia Under Sukarno

The Indonesians were not quite used to the idea of being one nation when independence came. The Dutch colonial adventure had lumped together dozens of tribes, with diverse languages, religions, and political opinions. The limited amount of unity that was shown while they were fighting the Dutch disappeared after the war, to be replaced by petty bickering between the political factions. Between December 1949 and March 1957 there were seven governments, each trying (not very successfully) to maintain internal security and develop the economy. During these years Sukarno sat above it all as a figurehead leader. The chaos prevented elections from being held until 1955; when they did take place the four parties that did best were the major Moslem party (Masyumi), the Moslem fundamentalist party (Nahdatul Ulama), Sukarno's Nationalists (PNI), and the communists (PKI). No party, however, won more than 25% of the seats in Parliament, a good sign that more trouble was on the way.

Into this confusion Sukarno stepped in, bringing order and increasing his personal power at the same time. He announced that Western-style democracy would only lead to anarchy. In its place he offered what he called "Guided Democracy," where a president with considerable power would be balanced by a national council of advisors that represented not only political parties but various professions: workers, peasants, the intelligentsia, businessmen, religious organizations, the armed forces, youth and women's groups, etc. What Sukarno hoped for was a national version of the government by consensus that had always been practiced on the village level. In practice, though, Sukarno found he had to please as many people as possible. To maintain popular support he juggled three political balls constantly, the military, the PNI and the PKI; his talents allowed him to do this for years, but disaster struck when those three factions finally became unbalanced.

US President John F. Kennedy with Sukarno.

Not everyone approved of Sukarno's policies. The export-producing Outer Islands felt the Jakarta regime discriminated in favor of densely-populated Java. In December 1956 several local army commanders on Sumatra and Sulawesi revolted, their goal being the establishment of a government that cared for them, not the communists. Sukarno and his defense minister, General A. H. Nasution, put down the rebellions by 1958, and they proposed bringing back the revolutionary constitution of 1945, a move which would give the president the emergency powers needed to deal with similar crises in the future. Sukarno urged this course in a speech to the Constituent Assembly, which had been elected in 1955 to draft a permanent constitution. When the Assembly failed to produce the two-thirds majority needed to approve the 1945 constitution, Sukarno, despite the dubious legality of such an action, introduced it by presidential decree on July 5, 1959.

As time went on, Sukarno directed the economy in a socialist direction, away from Western capitalists. To give the people a sense of national identity, he built grandiose buildings and monuments. His ideology was simplified to a cluster of slogans and abbreviations that anyone could remember: continuing revolution, Manipol (Political Manifesto), Ampera (the Message of the People's Suffering), Nasakom (the unity of nationalism, religion, and communism), and others. Western music, dancing, and institutions like the Boy Scouts were replaced with Indonesian substitutes. At the same time Sukarno behaved flamboyantly in public, traveled around the world on costly junkets, and lived like a monarch from Indonesia's pre-Moslem era. In 1955 he hosted the leaders of Africa and Asia at a conference in the city of Bandung, an event that started the Nonaligned or Third World Movement. Seven years later he sponsored a series of Asian sporting events as an alternative to the "imperialist-controlled" Olympics. All this was done with no concern for what it might do to the economy. To pay his bills Sukarno printed new money constantly; inflation and the national debt both rose steadily during the early 1960s.

Five leaders of the Nonaligned Movement. From left to right: India's Jawaharlal Nehru, Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah, Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser, Indonesia's Achmed Sukarno, Yugoslavia's Josip Broz Tito.

Indonesia has shown a remarkable aggressive streak in a world that considers international cooperation better than world domination. One example, the Malayan Confrontation of 1963-66, was discussed previously. When Malaysia joined the United Nations Security Council in 1964, Indonesia became the first (and only) nation to ever resign from the UN. In 1957 Sukarno got tired of waiting for the Dutch to get out of western New Guinea (also called West Irian or Irian Jaya), and launched his own campaign to get it. He ordered a 24-hour strike against Dutch-owned businesses in Indonesia, banned Dutch publications, prohibited the landing of KLM (the Dutch airline) planes at Indonesian airports, and nationalized Dutch holdings; this led to a mass exodus of 40,000 Dutch citizens from Indonesia. Using warships and planes supplied by the Soviet Union, he landed paratroopers on New Guinea. To defuse the situation, the UN took control of the Dutch half of the huge island in 1961, and handed it over to Indonesia one year later. Maps were published that changed the name of the Indian Ocean to the "Indonesian Ocean," called Papua New Guinea "East Irian," and even renamed Australia "South Irian," to the dismay of the Australians. The 1975 conquest of Portuguese Timor, covered in the next chapter, was a continuation of the same expansionist tendency.

The early 1960s saw the communists gain much power and prestige. Meanwhile Sukarno's playboy lifestyle gave him a collection of diseases, causing him to age rapidly. In 1965 Sukarno faltered in the middle of a speech and had to be helped from the platform, before the eyes of shocked thousands. Both the military and Western nations were concerned that the communists were preparing to come to power. The feeling by everyone that time was running out led to the violent upheavals of 1965.

On the last night of September 1965, a group of army conspirators kidnaped six generals, murdered them, and threw their bodies down a well. At dawn the coup leaders, who called themselves the 30th September Movement, announced they had seized power to prevent military treachery against the president. Sukarno, significantly enough, had spent the predawn hours at a nearby air force base, making friendly small talk with the men who killed his generals.

Two top-ranking officers managed to escape death. Defense Minister Nasution fled a hail of bullets that killed his infant daughter. The other was General Suharto(7) (1921-2008), the commander of the army's strategic reserves; he either was lucky enough or smart enough to be away from his house when the killers assigned to him arrived. Now he took command of the armed forces, launching a counter-coup against the conspirators. Within 24 hours he had broken the 30th September Movement and gained control of Jakarta.

The PKI insisted that the violence was an internal affair of the army, and that they were not involved in it. Nobody else believed that, and a vendetta of unmatched proportions was launched against the communists. Estimates of the numbers killed in the slaughter range from 80,000 to more than a million. Countless innocents were caught in the army or mob attacks; beautiful Bali was soaked in blood; rivers in central and eastern Java were said to have been dammed by bloated corpses. The Indonesian Communist Party went down for the third and last time.

Sukarno tried to save himself with his old act of balancing leftist and rightist factions. After the coup he formed a new cabinet, dismissing Nasution and hiring a number of communist sympathizers. That made Sukarno look pro-PKI to many. Student protests increased, and Sukarno was forced to give his powers to Suharto, who now became acting president. The next year (1967) saw Sukarno removed from office, and in March 1968 Suharto was elected to take his place. Sukarno was kept under house arrest until he died in 1970.

The Philippines: A Dictatorship Made For Two

For eight years the Philippines muddled through the rule of two mediocre presidents, Carlos Garcia (1957-61) and Diosdado Macapagal (1961-65). Both of them did little to solve the country's problems, both were uncharismatic, and both ran corrupt administrations, inspiring little hope for the future. During this time the Philippine government functioned as a noisy version of the US government it was patterned after. The Manila press reeked of sensationalism, and politicians could be very vocal when expressing their opinions. Stanley Karnow, a retired TIME-LIFE correspondent, reported one such example when he first visited the Philippines in 1959. The legislature at the time was debating the latest tax proposal when Miguel Cuaderno, a banker who supported the measure, arrived. Alfredo Montelibano, who represented the sugar companies and opposed the tax, spotted Cuaderno and shouted, "You are mentally dishonest." Cuaderno responded with, "And you are a coward who deserves to be shot." Both men reached into their briefcases, and the Assembly scrambled for safety, but the two rivals were talked out of violence and the hearings went on. Filipinos considered the incident routine, and it only rated a paragraph in the newspapers the next day.

Every trick in the book was used at election time, like using "gold, guns and goons" to influence the voters, ballot box stuffing, and adding names from tombstones to lists of people who voted. Control of the government changed hands between the Liberal and Nationalist parties with every election, but since both parties derived their support from the landowning upper class, there was hardly a difference between them. All things considered, the best thing about the presidents of the pre-Marcos era is that none of them was elected more than once.

When Ferdinand E. Marcos was elected president in 1965, he was seen by many as the most promising leader to come along since Ramon Magsaysay. The son of a school supervisor in Ilocos Norte, the country's northernmost province, he first went to law school, where he scored so high on the exams that he was accused of cheating, until he refuted the charge by reciting the legal texts he knew by heart. He gained national attention in 1938 when he was accused of murdering a political rival of his father. Acting as his own lawyer, Marcos won his release from a conviction by delivering an emotional address that moved the judge to tears and gained the admiration of everyone. No one knows for sure what he did during World War II, but afterwards he claimed to be the war's greatest hero, leading a force of 8,000 guerrillas (that story was completely false, but he told it so many times that he came to believe it himself). In 1949, at the age of 32, he became the youngest member of the legislature by appealing to the provincial pride of the voters: "Elect me now and I promise you an Ilocano president in twenty years." In 1954 he married a former beauty queen, Imelda Romualdez, and on the day he was sworn in as president, she got more attention than he did. Together Ferdinand and Imelda made an attractive couple, often compared with John and Jackie Kennedy.

Imelda & Ferdinand Marcos.

Marcos promised to rid the country of crooked politicians, but eventually he would outdo them all. He got rid of the old political parties and introduced in their place a party he controlled completely, the New Society Movement. Likewise the old oligarchy was swept away, only to be replaced by one of his own creation. Imelda became governor of Metro Manila, Minister of Human Settlements, and chairperson of 23 other agencies and corporations; this gave her an unflattering nickname, the "Iron Butterfly." Imelda's brother Benjamin first became governor of Leyte (his family's home island), then ambassador to China, and finally ambassador to the United States. The president's sister, and later his son, were governors of Ilocos Norte. A daughter joined the legislature. His brother Pacifico led the Medicare Commission and 20 different private companies. A third cousin, Fabian Ver, was named Chief of Staff of the armed forces. Other friends and relatives were placed in charge of key industries, like coconuts and sugar. Whoever got those jobs returned the favor with enormous kickbacks. The constitution only allowed him two four-year terms in office, so he started looking for ways to change it so he could rule indefinitely.

As the economic misery of the people got worse, it was translated into political unrest. In 1968 a group of disgruntled students and former Huk guerrillas got together to form another communist movement, the New People's Army (NPA). Unlike the Huks, who concentrated themselves in one area, the NPA spread its members out to every province of the country. They murdered and plundered freely, but were a more disciplined force than the police or the army, and they won followers by dispensing a rough form of justice against unpopular local officials, unfaithful husbands, and anyone else the common people disliked. In 1972 a Moslem guerrilla movement, the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), launched a campaign in the south to create an independent Moslem state named Bangsa Moro.

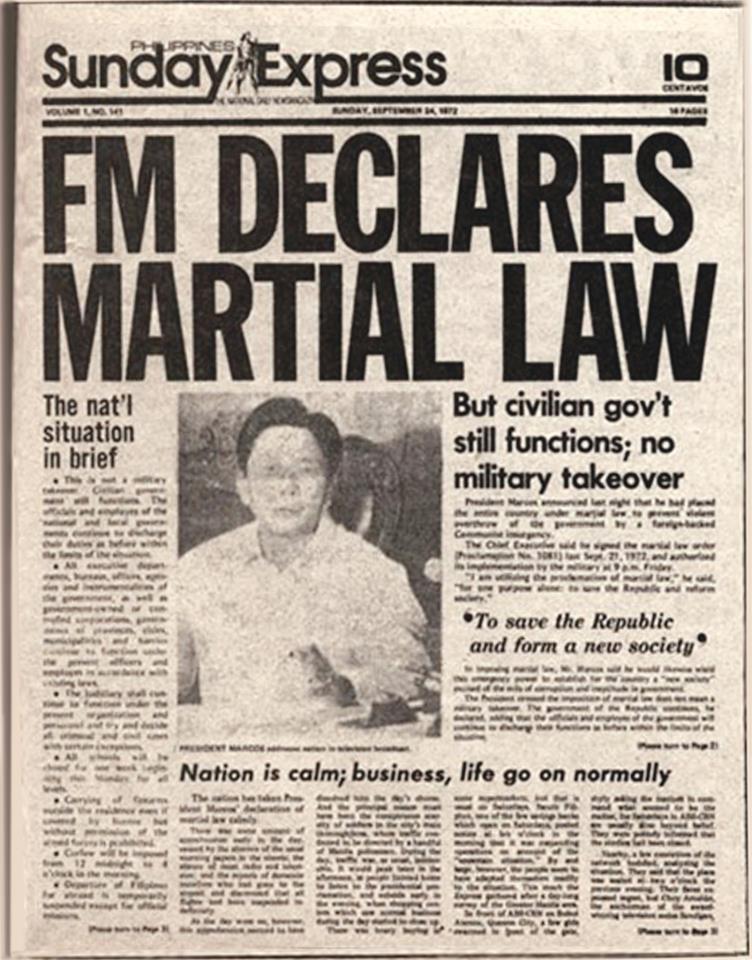

The Filipinos began to suspect that something was not kosher when Marcos won reelection in 1969. During his second term a number of disturbing events took place, and Marcos made no attempt to hide them. Inflation reached a rate of 18% a year; volcanic eruptions and earthquakes disrupted the lives of many; anti-government demonstrations turned violent; bombs and grenades were thrown at politicians. By 1972 Manila seemed to be slipping into anarchy. In September, unidentified gunmen ambushed an empty car that was supposed to be carrying the defense minister, Juan Ponce Enrile. Years later Enrile admitted that he staged the incident to get a reaction from Marcos. Sure enough, it played into the president's hands perfectly. Marcos blamed the current wave of violence on the communists and imposed martial law on the country. He closed down newspapers, radio and television stations, censored those that remained in operation, seized control of the airline and public utilities, placed a nighttime curfew on Manila, and jailed six thousand political rivals, journalists, professors and students, branding them communists or communist sympathizers. Most of those arrested were eventually released, but Senator Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino, whose only crime was running ahead of Marcos in public opinion polls, languished in prison for seven and a half years. Now able to get what he wanted, Marcos produced a new constitution that allowed him to rule for life, with unlimited powers during emergency situations like this one.

A 1972 newspaper, announcing the declaration of martial law.

There is something of a tradition in Asia that gives approval to heads of state that take away freedom and give an improved standard of living in return. 20th-century examples of such benevolent dictators ruled in Turkey, Thailand, Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea. For this reason, most Filipinos in 1972 thought that martial law was the proper solution to the country's problems, and even Aquino admitted that he might introduce some kind of authoritarian regime if he became president. If Marcos behaved in the above manner, he might have gone down in history as a good leader. But instead he and Imelda used their new powers to live extravagantly, impoverishing the Philippines in the process. The government got nothing done without huge bribes being paid, either to the president or someone else in his inner circle. He amassed a hidden fortune in gold, real estate, and Swiss bank accounts, estimated to be worth billions--all the time receiving only $5,600 per year as an official salary. Imelda gave lavish parties that looked like something out of a Cecil B. DeMille movie, and went on megabuck shopping sprees whenever she visited the United States. The rest of the country had to pay the bill for this, and the economy took a nosedive; from 1983 to 1985 the gross national product dropped a rate of -5% a year. The United States generously gave aid during these years, convinced that only Marcos could keep the country (and the US bases) out of communist hands; Washington asked no questions and Marcos got the same friendly treatment given to pro-US dictators elsewhere.(8)

Marcos ended martial law in 1981, and was re-elected again. Not long after that the new US vice-president, George H. W. Bush, attended the inauguration and praised Marcos for his "adherence to democratic principles." Actually, it no longer mattered whether there was martial law or not, since Marcos still ruled by decree and could rig elections as much as he pleased.

Thailand Experiments With Revolution

Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat ran the government of Thailand from 1957 until his death in 1963. Concerned with where the nation was heading, he acted in a number of ways to improve and modernize Thai society. He dedicated himself to making Bangkok clean and orderly by repairing streets, removing hooligans, outlawing the sale and use of opium, and by bringing prostitution under control. He banned pedicabs because he thought they were old-fashioned and uncivilized. All opponents of his regime were denounced as communists and detained for long periods without trial or bail; that move by itself brought stability to Thailand for the next 15 years.

Sarit justified his actions by inventing an ideology that has been followed since his time. The way he saw it, an abstract constitution would not work well in Thailand, where most people still respected traditional authority. What Thailand needed was a strong leader who was firm but also concerned for the welfare of the people. The king was once that authority figure, but nobody wanted a return to absolute monarchy, so a separation between crown and government had to continue. The king did, however, play an important role as a symbol of the nation and the people, and the government could only claim to be legitimate so long as it had the king's approval.

The Sarit government's first priority was economic development, and the standard of living climbed impressively during this time. Sarit also prospered, perhaps too much; he left behind fifty mistresses and a fortune worth $150 million, which included large holdings in various companies, 8,000 acres of land, and several houses. Of course he did not acquire that wealth honestly, but after experiencing the rule of his successors the public felt Sarit may have been worth the price. He was succeeded by his prime minister, General Thanom Kittikachorn, who ruled by martial law for much of the following decade (1963-73).

The Thanom regime experimented with introducing the elements of democracy, but very cautiously. A new constitution had been promised back in 1959, but it did not go into effect until 1968. Elections established a new legislature in 1969, but rule by decree came back three years later when Thanom became concerned over domestic and foreign developments. The Nixon administration was pulling out of Vietnam and normalizing relations with China; both events threatened Thailand's security. Worse than that was the unrest at home. China and Vietnam punished Thailand for its pro-US stance by arming communist guerrillas; they started making trouble along the Laotian border in 1965. A Moslem revolt rose up in the far south. And the country's students, educated in far greater numbers than ever before, were becoming familiar with Western values and deploring the lack of political progress.

Matters came to a head in 1973 when student protests against the government snowballed into gatherings of hundreds of thousands. After bloody clashes between civilians and the police, the king declared that he was on the side of the students, farmers and middle-class demonstrators. Thanom lost the military support he needed and was forced to resign. A civilian government took over, a new constitution was written, and a new democratic era seemed to be beginning.

Despite its best efforts, the new regime could not bring stability. 1974 saw demonstrations against Japanese-made trade goods while the Japanese prime minister was visiting, followed by anti-Chinese riots. When elections were held in 1975, 42 parties sponsored 2,193 candidates for 269 seats in the Assembly, making sure that no party would win a majority. Three prime ministers held office between 1973 and 1976, and the coalitions they put together came apart at least once every year. Meanwhile, the communist victories in Indochina forced Thailand to rethink its foreign policy. With its own communist insurgency growing, there was a very real concern that Thailand would degenerate into another Vietnam-type situation. The American servicemen in Thailand were ordered to leave, except for a few advisors, and the US bases were turned over to Bangkok.

While feuding politicians entertained or exasperated the middle class, leftist students became more radical, alienating the monarchy, the bureaucracy, and the public with their behavior. In October 1976 former prime minister Thanom returned from exile as a Buddhist monk, and became respectable when the royal family visited him. Leftists protested Thanom's reception and committed the unpardonable sin of insulting the royal family, triggering a right-wing backlash. Mobs and the police engaged in an orgy of violence, killing many students before the military stepped in, abolished the government, and restored order. Many Thais were revolted by the barbarity of this episode, and that made them more politically moderate in the years that followed.

This is the End of Chapter 5.

FOOTNOTES

1. After the battle of Dienbienphu, the United States sent in Edward Lansdale, the agent who had gotten Ramon Magsaysay elected president of the Philippines, to see if he could put somebody like that in charge of South Vietnam. Lansdale was so anti-communist that when he heard the French were not going to defend Hanoi to the last man, he suggested a "military coup in Paris to make [a] lady out of [a] slut." But he also knew that dirty tricks should not be obvious. For the 1955 referendum, Lansdale told Diem not to rig the vote, because he would probably win anyway, with a 60-70% majority. Instead, the vote counters reported that Diem won with 98.2% of the vote; in Saigon they reported 600,000 ballots cast in Diem's favor, though there were only 450,000 registered voters!

2. Because Diem was a bachelor, Madame Nhu became the country's unofficial first lady. Her favorite motto was, "Power is wonderful. Total power is totally wonderful."

3. The Laotian cabinet now had five communist, five rightist, and two royalist members.

4. American evangelist Mike Warnke served as a marine in Vietnam for three years, and tells the story of how he was handing out candy bars to Vietnamese kids, one of the nicer things anyone can do in a war zone. One boy who couldn't have been older than twelve took a candy bar, ran into his house, came out with a pistol and shot him! Warnke wasn't seriously hurt, since he was wearing a bulletproof vest, but the impact knocked him out of the jeep he was standing in. The first thing he thought of as he hit the ground was, "If you don't like Hershey with almonds, say so!"

5. Oberdorfer, Don, Tet!; The Turning Point in the Vietnam War, New York, Johns Hopkins University press, 1971, pg. 332.

6. Some of Lon Nol's soldiers barricaded themselves in Preah Vihear, a Hindu temple built by the Khmers in the eleventh century. One soldier said, "This is the Khmer Republic. It is very small now." Because of Preah Vihear's location, on high ground along the Cambodian-Thai border, they held out until May 22, 1975, five weeks after Phnom Penh fell, and this was the last part of the country to be taken by the Khmer Rouge.

7. Like many Javans, Suharto used only one name.

8. Near Baguio City, Marcos had his face carved into a mountain, Mt. Rushmore fashion; it was finished in 1985, a few months before the end of his presidency. The bust stood intact until 2002, when it was severely damaged in an explosion that took out the eyes, forehead and cheeks. Whoever blew it up is unknown; the vandal(s) could have been left-wing activists, members of a local tribe, or looters following a rumor that Marcos hid treasure in it. In that sense Marcos is a modern-day Ozymandias, building monuments to make people remember him forever, only to have those monuments fall into ruin later.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A Concise History of Southeast Asia

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|