| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of the South Pacific

Chapter 4: The Great Pacific War, Part I

1914 to 1945

Part I

Part II

| The Pacific War Begins | |

| From Pearl Harbor to the Coral Sea | |

| The Battle of Midway: The Tide Turns | |

| The New Guinea Campaign, Part 1 | |

| Guadalcanal | |

| The New Guinea Campaign, Part 2 | |

| Climbing the Solomon Islands, and Part 3 of the New Guinea Campaign | |

| The Pacific Drive | |

| The Last Carrier vs. Carrier Battle | |

| The End of the War is in Sight |

World War I: The Prologue

In the previous chapter, we saw six Western nations divide the South Pacific between themselves: Spain, the Netherlands, Britain, France, Germany, and the United States. By 1900, just about all of the islands had been claimed, and one of the empires, Spain, had been knocked out of the game by the United States. True, Australia and New Zealand had been granted self-government in the first decade of the twentieth century, but their obligations as members of the British Commonwealth meant that in times of war, they acted like they were still part of the British Empire.

The next nation to lose its empire was Germany. In the forty-three years after its 1871 unification, Germany grew by leaps and bounds. By 1914, Germany had the most efficient army in Europe, the strongest industry, and because its gross domestic product had just pulled ahead of Britain’s, it was now the richest European country as well. However, Britain still ruled the waves, despite Germany’s vigorous efforts since the late 1890s to build a fleet that could take on the Royal Navy. Thus, when World War I began, Germany had an early advantage in Europe, but all of its overseas colonies were isolated, lightly defended, low-hanging fruit that the British and anyone allied with them could pick off at will.

At the beginning of the war the leaders of Europe promised their subjects that this war would be short, with light casualties, like most of the wars from the previous century. They did not expect a variety of new weapons, from machine guns to poison gas, to change the rules of warfare. Because of those weapons, in Europe and the Middle East, World War I was a bloody slugfest, killing millions and lasting for years. But because of Britain’s naval advantage, the war’s Pacific phase went quickly and almost bloodlessly, as had originally been predicted for all fronts.

Australia and New Zealand were in the war automatically when Britain declared war on Germany, and because the Japanese had an alliance treaty with the British, Japan declared war three weeks later, on August 23, 1914. New Zealand troops captured German Samoa without resistance on August 29, and the Australians took Nauru on September 9.

However, there was a bit of fighting when the Australians attacked a larger colony -- German New Guinea and the Bismarck and Solomon archipelagoes. On New Britain (then called New Pomerania by the Germans), 500 Aussies met and defeated a defending force of 301 (61 Germans and 240 Melanesian policemen) at the battle of Bita Paka, on September 11. The remaining Germans on the island surrendered at Toma, on September 17. By September 24, the rest of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands were also in Allied hands. A single German officer in Kaiser Wilhelm Land, near Angorum, tried to resist with a force of thirty natives, but was captured in December 1914 after the natives deserted him. That left twenty German soldiers in New Guinea’s interior, commanded by Hermann Philipp Detzner. This group (I won’t call them a force, because they didn’t have enough men to count even as a platoon) had been sent in early 1914 to explore the hinterlands; after the war started, they hid from Allied troops, and obtained the supplies they needed from German missionaries in the neighborhood. By avoiding defeat and capture, Detzner, like Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck in East Africa, remained at large throughout the entire war, and when he finally surrendered in January 1919, he went back to Germany as a hero.

North of New Guinea, the Japanese had no trouble seizing Germany’s Micronesian islands: the Marshalls, Carolines, Marianas and Palau. This task took all of October 1914 because the islands were spread out over such a large portion of the ocean. The only hotly contested territory was Kiaochow (modern Qingdao), the German colony on the coast of China; British and Japanese forces began to surround this port at the end of August, and it fell on November 7, 1914, after a siege which killed 727 Allies and 199 Germans.

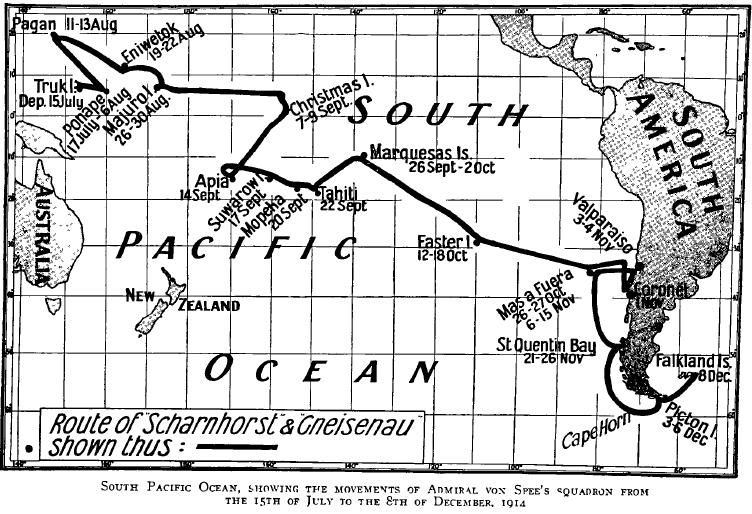

That ended all the land battles in the Pacific for the war, but there were some naval actions worth talking about after that. Six cruisers, the German East Asia Squadron, were performing various duties in the northwest Pacific when the war broke out. The squadron commander, Vice Admiral Maximilian, Reichgraf von Spee, knew they didn’t have a chance of beating the Allied fleets in the region; he figured the Australian flagship, the HMAS Australia, was strong enough to defeat the squadron all by herself. All they could do was try to make it back to Germany, where the German command could give them a more useful assignment. Accordingly, von Spee left Kiaochow on August 6, and the squadron assembled in late August at Pagan, an island in the Marianas. One ship, the Emden, captured a Russian steamship and converted it into a commerce raider; this success prompted von Spee to let the Emden separate from the squadron and go on independent raiding in the Indian Ocean. The other five ships headed east across the Pacific, the plan being to gather what supplies and information they could get from the neutral nations of the western hemisphere, before entering the Atlantic for the last part of their journey. On the way they destroyed a British wireless & cable station on Fanning Island, and bombarded Papeete in French Polynesia. At Easter Island they were able to refuel, because the local coaling station had not yet heard about the war. After this, though, the squadron lost the element of surprise and the British West Indies Squadron caught up with it off the coast of Chile. The Germans won the resulting battle, the battle of Coronel, but then their luck ran out after they rounded Cape Horn; at the next battle, the battle of the Falkland Islands, von Spee was killed and most of the German ships were sunk. The only vessel which escaped, the Dresden, returned to Chile; three British cruisers cornered the Dresden and sank her near the Chilean island of Más a Tierra (Robinson Crusoe’s island!) on March 14, 1915.

The journey of the German East Asia Squadron.

As for the Emden, she spent September and October prowling in the Bay of Bengal and around the Maldive Islands. During this time fifteen merchant ships were sunk, for a total of more than 70,000 tons, and eight were captured. Captured ships were allowed to move on if they and their cargoes were not owned by an Allied nation. Two special advantages helped this light cruiser achieve so many successes: a long range (she could go up to 6,000 miles before recoaling), and the addition of a fake fourth smokestack, which made the ship look like a British cruiser.

The strangest part of the adventure came when the Emden and a captured British collier visited Diego Garcia, a British-ruled atoll south of both the Maldives and the equator, for repairs and rest. This island was so remote that it only got news from the ships that arrived (usually one came by every three months), so the locals, like the Easter Islanders, did not know the outside world was at war. The Emden's captain, Karl von Müller, claimed they were part of joint German-British-French "world naval maneuvers," and informed a local plantation owner that Pope Pius X had died, but did not bother to mention the other big news story from the past few months. The plantation owner allowed his guests shore leave, gave the crew fresh eggs and vegetables, and the natives helped the Germans scrape the barnacles off their hull. In return, the Germans gave the locals cigars and whiskey, and repaired the motor on one of their launches.

After leaving Diego Garcia, the Emden headed to the Malayan port of Penang, where in the biggest battle of the campaign to date, she sank a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer. Then the cruiser headed to the Cocos Islands, a pair of atolls about halfway between Australia and Sri Lanka, and sent a landing party ashore to disable the British wireless & cable station there. However, the station managed to get off a distress signal to a nearby Allied convoy, which was transporting troops from Australia to Egypt, and one of its cruisers, the HMAS Sydney, came to investigate. The Sydney and the Emden fought for seven hours on November 9, 1914; the Sydney suffered light damage, while the Emden was turned into a wreck, and Müller ran the ship aground on a reef so that some of the crew would survive. 142 of the Emden's crew were killed; the survivors were sent to Australia if they were wounded, and to an internment camp on Malta if they were healthy (the latter included an officer who happened to be a Hohenzollern prince). After that, the Central Powers had no ships left in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, so Allied troop transports and civilian ships could now travel those seas without escorts, allowing the Allied navies to concentrate their attention on the Atlantic.

Speaking of transporting troops, for Australians and New Zealanders, the most important military actions were not those which took place near their homelands, like the annexation of Samoa, but the Old World battles their troops participated in. Called the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), they first were used to defend the Suez Canal from the Turks, and then sent to Turkey for the Gallipoli campaign; of the more than half a million Allied troops at Gallipoli, 34,000 came from ANZAC.(1) In early 1916 ANZAC troops began to be used on the Western Front in Europe, and in 1917 they took part in the Mesopotamian campaign, and in the Sinai-Palestine campaign, which eventually cleared the Turks out of the Levant.

The Australian 9th and 10th Battalions, here seen at Giza, Egypt, brought a kangaroo mascot.

For both countries the cost of participating in the war was heavy, at a time when they were just getting used to standing independently from Britain. At the time, Australia had 4 million people, and New Zealand had 1 million. No draft was needed; ten percent of the population of each country volunteered to fight overseas. And because of the nature of World War I combat, casualties were heavy, too. Below are the numbers; more than half of the casualties were inflicted in the deadly stalemate on the Western Front:

|

Nation

|

Enlisted

|

Killed

|

Wounded, gassed, or captured

|

|

Australia

|

416,809

|

61,829

|

157,156

|

|

New Zealand

|

100,444(2)

|

16,697

|

41,317

|

As you might expect, the homelands mourned their countrymen who didn’t live to come back, promoted women to take jobs formerly held by men, endured physical and economic stress from supporting the war effort, and experienced growing resentment as the war went on. However, the war was also seen as a defining event for both nations, marking the maturity of their societies and helping to create national identities for both of them. As Ormond Burton, a decorated New Zealand veteran, put it, "Somewhere between the landing at Anzac [a Gallipoli beachhead] and the end of the battle of the Somme, New Zealand very definitely became a nation."(3)

The Allies got some excitement in 1917, when a German commerce raider interrupted their sense of security in the Pacific. This was a converted merchant, the Seeadler(Sea Eagle), and because coal was not likely to be available, a sailing ship was chosen for this mission, with a few machine guns and a supplemental diesel engine added. To get past the Royal Navy, the captain, Count Felix von Luckner, pretended the ship was a Norwegian merchant, and employed a crew of Norwegian-speaking Germans to complete the disguise. It worked, and in the first three months of 1917, the Seeadler's crew captured twelve Allied merchant ships in the Atlantic, sank eleven of them, and kept the prisoners on the twelfth. For the prisoners, von Luckner was a noble villain, who allowed captured officers to eat their meals with him, and only one Allied sailor died in the raids. When von Luckner had more than two hundred prisoners, he took them to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and dropped them off there.

By then the Allies knew the Seeadler was prowling in the South Atlantic, so it was time to take the show elsewhere. They rounded Cape Horn, going against the same storms and fierce winds that other ships going westward around the cape have faced (see Chapters 2 & 3), and after they entered the Pacific, they captured and sank three more ships, before von Luckner decided to head for the Society Islands, for fresh food and water. An uninhabited atoll, Maupelia, was picked as the place for this stop, but here the Seeadler ran aground on a reef, stranding the crew and forty-six prisoners. Von Luckner took a lifeboat and five of his crewmen and sailed to Fiji, in the hope that they could capture another ship and bring it back to rescue everybody else. Instead, on the Fijian island of Wakaya, the local police refused to believe they were Norwegians and arrested them. They were then taken to New Zealand, where von Luckner managed to escape once before he was captured for the second and last time. Back on Maupelia, the Seeadler crew captured a French schooner, the Lutece, when it stopped by in September 1917, and renamed it the Fortuna. This ship carried the crew to Easter Island, before it also ran aground on a reef. Then they were taken to Chile, and because Chile was a neutral nation, they had to stay in that country for the rest of the war, but otherwise they remained free.

After the war, the Japanese (under American pressure) returned Kiaochow to China, while the new international peacekeeping organization, the League of Nations, awarded the other ex-German and ex-Turkish territories in Africa, the Middle East and the Pacific as "mandates" to the nations that had captured them. In the Western nations, popular opinion was starting to swing toward the idea that the colonies could not be exploited forever, so the mandates would be handled the same way the United States was handling the Philippines -- outsiders would only rule until the peoples living in them were ready to govern themselves. However, there was no time limit put on how long the mandates would last; of the sixteen mandates established, only one (Iraq) became independent before World War II. Most of the mandates still existing in the late 1940s were reorganized under the name of "trust territories." We will come back to one of them, the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, in the next chapter. Whether you want to call them mandates or trust territories, this one was the longest-lived; it finally ended with the independence of Palau in 1994.

The Pacific Islands in the Interwar Period

Before World War I, the policy for most of the colonial powers was exploitation if there were resources worth the effort, and pacification. The latter meant preventing internal violence between native tribes and villages, as well as preventing native-white violence. This was especially the case in Melanesia, where places like New Guinea and the Solomon Islands had been occupied just one generation before World War I, and thus had not yet adapted to the new society imposed on them. Most islands did not have economic opportunites to attract settlers, so their native communities managed to muddle through these tough times. One notable exception was New Caledonia, where the nickel mining industry brought in so many immigrants that the native Kanak population seemed to be on the verge of extinction in the early twentieth century.

However, the United States administered its territories differently. We noted in the previous chapter that unlike the Europeans, the Americans had little motivation to exploit or civilize the places they held, and after 1898, only the Philippines required a pacification campaign. Now the Philippines were being prepared for independence; in 1934 they became a self-governing commonwealth, like present-day Puerto Rico, and July 4, 1945 was picked as the date for full independence.(4) Meanwhile, American Samoa and Guam were largely ignored, except for the US naval base at Pago Pago and Guam’s coaling and communications station.

Hawaii got special treatment, due to its large immigrant community; this was the only US-held territory that attracted more than a handful of Americans from the mainland. Because of this, Americans expected that Hawaii, and not any other recently acquired territory, would someday become a US state. The newcomers formed a multiclass society, with the haoles (whites) on top, the Asians in the middle, and native Hawaiians on the bottom. Asians formed a pecking order of their own, with Japanese outranking Chinese, Koreans, Filipinos, and Samoans. Though this hierarchy wasn’t a happy arrangement, it was a stable one, since native Hawaiians were now a minority in the archipelago (today Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders make up just 10 percent of the population). As interracial marriage became more socially acceptable, it began to blur differences between the ethnic groups; by the 1980s, 30 percent of Hawaiian marriages were mixed.(5)

By the end of World War I, all Pacific islands had been pacified. The Commonwealth nations ruling parts of the Pacific (the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand) came to see their colonies the same way the United States did. Now indigenous peoples became wards of the state; maybe exploitation could go on for a little while longer, but that would have to be phased out, as preparations for eventual independence got underway. By contrast, France, Japan and the Netherlands still treated their colonies as places to exploit; in fact (spoiler alert!), the only Pacific colony France would turn loose was the jointly-ruled New Hebrides.

Fiji’s main problem during this period had to do with a group unwanted by native Fijians, and neglected by the British -- the Indian workers. Because India was the British Empire’s most important colony, and the British Empire was a big promoter of commerce, today you can expect to see Indians in any country Britain used to rule. However, the colonial government discouraged cooperation between Indians and Fijians, and discriminated in favor of the latter. While Britain was building schools, clinics and hospitals, and generally improving the living standard of the Fijians, the Indians did not benefit much from these improvements. The Indians also resented having none of the political and civil rights that automatically went to the Europeans, though they came to Fiji because the Europeans invited them. Nor could they own land, unless Europeans sold it to them, because Fijians were forbidden to sell their land. The practice of importing Indians as indentured labor was abolished in 1916, and the last indentured contracts ended in January 1919, but most of the Indians stayed afterwards, and usually their families came to join them. These Indians ended up starting small businesses, or became farmers on land that they rented in long-term leases.

The first organized workers’ strikes in Pacific island history took place during this period. On January 15, 1920, Indian employees of the public works department in Suva, Fiji, walked off their jobs. They demanded higher pay because the cost of food had gone up during the World War I years, and refused an order to work 48 hours a week instead of the previous 45 hours. The government simply used white and Fijian policemen to restore order; in one confrontation, a striker was shot dead and several wounded. Immediately after this strike ended, another broke out on the same island, this time against the Colonial Sugar Refining Company. The demands of these workers included more pay, specified work hours, improved housing, medical and pension benefits, classrooms for their children, and small plots of land to keep dairy cattle. 250 Fijian constables were brought over from Bau to break up the second strike. Also, a recently arrived Hindu priest, Sadhu Basisth Muni, was falsely accused of being an agent of Mahatma Gandhi, and deported. The state of Fiji’s Indian community only began to improve in 1929, when the local legislature was enlarged to include three elected Indian members.

White over-reaction to the peaceful Rabaul strike of 1929 created the first Papuan nationalist, a boat captain from New Ireland named Sumsuma (1903?-65). A man with exceptional drive and initiative, he was such a good worker that by 1928 he was the best-paid native in the Australian New Guinea territory, earning £12 a month when the typical Papuan worker only earned five or six shillings, 1/48th as much. At the end of that year he teamed up with another native, N’Dramei, the senior sergeant-major of police in Rabaul, the capital of New Britain. Together they persuaded 200 police and 3000 Papuans, almost all the workers in Rabaul, to walk off their jobs until their wages were raised to £12 a month, too. On the morning of January 3, 1929, the whites living in Rabaul woke up to find that none of their native employees/servants had shown up for work. Instead, because most of the workers were Methodists or Catholics, they had gathered at the Methodist and Catholic missions outside of town. Sumsuma thought the missionaries would negotiate on behalf of the strikers in their congregations, but they refused, and the employers refused to make any kind of deal, so the strike collapsed by the end of the first day.

Afterwards the white response was one of panic; they behaved as if the native population had revolted outright. The government fired 190 policemen, and sentenced most to six months of hard labor, while twenty-one other strikers, including Sumsuma and N’Dramei, got three-year jail sentences; Sumsuma was beaten badly enough to leave permanent scars. During World War II Sumsuma collaborated with the Japanese, and when the Australians returned they put him in jail again, this time on charges of cargo cult activities (we will look at the cargo cults in the next chapter of this work). After he got out he remained a local activist for the rest of his life, starting institutions like a bank and a school with the help of a Catholic mission.(6)

Overall, Tonga fared best of the Pacific islands. Readers of the previous chapters of this work will understand why; though they were considered part of the British Empire, Tonga was a protectorate rather than a full colony, and its monarchy was still going strong. At the beginning of the period covered by this chapter, George Tupou II was still the king. Because all three of his children were daughters, the eldest, Sālote, became his heir. Then in 1918, both the king and queen fell victim to the Spanish flu epidemic that was sweeping the world at the time, and the six-foot-two, eighteen-year-old crown princess became Queen Sālote Tupou III (1918-65).(7)

The queen got off to a good start because of a good marriage. One year before she took over, her father arranged a marriage with a chieftain named Viliami Tungī Mailefihi, though he was twelve and a half years older. This proved to be a move that helped keep the kingdom stable, for the Prince Consort was a descendant of the defunct Tu'i Ha'atakalaua dynasty. Because the princess had the ancestry of the Tu'i Kanokupolu on her father’s side, and the Tu’i Tonga on her mother’s side, her children, and thus all rulers of Tonga after her, would be descended from all three of Tonga’s royal families. Prince Tungī also served as prime minister of Tonga, from 1923 until his death in 1941. By then the king and queen’s son, the future King Tupou IV, was twenty-three years old, so he became the next prime minister.

Sālote Tupou III is the most-loved monarch in modern Tongan history. Partially this is because she led the kingdom well, especially during the World War II years, so you can credit her with fixing the political mess Tonga was in before her reign. And while copra production was almost the only source of income, it remained in Tongan hands, and a small budget kept Tonga debt-free. In 1959 she modified the friendship treaty with Britain, which would be the first step toward terminating the protectorate under her successor.

The other reason for Queen Sālote’s popularity is that she was a patron of native culture, especially poetry and dancing; in fact, she wrote many dance songs and love poems. Yet at the same time she restricted commerce with the outside world, because she did not want her people to become Westernized; e.g., she did not allow the building of a modern hotel in Tonga for that reason. In 1953 she gained international attention by going to London to attend the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. During the parade, a rainstorm drenched the crowd and hoods were put over the carriages, but Queen Sālote insisted on riding bareheaded in the rain, because Tongan custom dictates that visitors paying respect to royalty should not demand the same treatment as those they are honoring. This endeared her to the spectators, and also the new Queen of England; Elizabeth and Prince Philip returned the honor by visiting Tonga later in the same year.

Samoa did fairly well, because it did not have any large non-Samoan communities, and because much of the economy remained in native hands; moreover, the land owned by German citizens before the war was confiscated by the colonial government, and not given to other outsiders. A nationalist movement had sprung up here in 1908, called the Mau ("Opinion") movement. The Germans exiled its leaders to Saipan, but New Zealand tolerated the movement, so long as it did not turn violent. The one exception came in 1929, when the New Zealand police dispersed a peaceful demonstration in Apia by shooting into a crowd, killing twelve, including a senior chief, Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III. Western Samoa suffered the most in November 1918, when a New Zealand steamship, the SS Talune, brought the Spanish flu to Apia. Because the crew and passengers on the ship were not quarantined, 90 percent of the native population caught the flu, and 20 percent died from it. Meanwhile on American Samoa, the US-appointed governor slapped a quarantine on the territory so strict that nobody there died from the disease. As a result, in January 1919 some Western Samoans presented a petition to be transferred to either American or British rule. The government refused to consider such a move, of course, but they got the message to shape up.

Residents of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands were not exploited, simply because most of those islands had no resources to exploit. The exception came from two tiny islands on the southern edge of that territory: Nauru and Ocean Island (modern Banaba). These islands had extremely rich phosphate deposits that attracted mining companies, and the miners literally dug the land away while giving the residents the lowest compensation possible.(8)

The Interwar Years: Australia

To refresh the reader’s memory, Australia’s political system started out with three parties, two Liberal and one Labor Party. Elections were held in September 1914, six weeks after World War I began, and Labor won. However, the workload was more than the new prime minister, Andrew Fisher, could handle, and his health suffered so much that he resigned a year later; the deputy party leader, William Morris "Billy" Hughes, took his place. He would prove to be not only a vigorous

leader during the war years, but also held the office for a total of eight years (1915-23), longer than most Australian prime ministers.

By mid-1916, Australia had suffered so many casualties that Billy Hughes was persuaded that some kind of military draft would be needed, if the nation’s participation in the war effort was not going to falter. However, most of his party was strongly against it, and when he held a plebiscite on the issue of conscription, it was defeated. Around the same time, Hughes walked out of a Parliamentary session after saying, "Let those who think like me, follow me," and twenty-four other members left with him, so Hughes was expelled from the Labor Party. To keep his job as prime minister, Hughes and the pro-conscription members of the Labor Party joined the Commonwealth Liberal Party, to form the Nationalist Party of Australia, and they won a huge victory when the next election took place, in May 1917. Another plebiscite on conscription was held in December, which was also defeated, but as we saw at the beginning of this chapter, a draft wasn’t needed.

Because of Australia’s participation in the war, Hughes attended the peace conference afterwards and signed the Versailles Treaty, though he personally felt the League of Nations was a very bad idea (however, he managed to get independent representation for Australia in the League). As the 1920s began, the popularity of Hughes faded, and after the Nationalist Party lost the 1922 election, conservatives within the party forced Hughes to resign. He was succeeded by another Nationalist, Stanley Bruce, who served from 1923 to 1929. Meanwhile, the Country Party was founded in 1920 to represent conservative farmers and ranchers. At first it joined the Nationalist Party’s coalition; more recently it has been called the National Party since 1975, and usually it works in a coalition with the Liberals.

The 1920s were a time of rapid change. Australians went from owning 50,000 cars and trucks in 1918, to 500,000 in 1929. The Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Service (now called Qantas Airlines) was founded in 1920, and the Reverend John Flynn founded the famous Royal Flying Doctor Service in 1928, to handle the medical needs of those in the outback. With these transportation advances came an encouragement of consumerism and entertainment; in that sense, you could say Australia was imitiating the United States during the "Roaring Twenties" era. However, while Hollywood movies were popular, Australia’s film industry wasn’t a success until the 1970s, and like New Zealand, Australia rejected moves to introduce prohibition. Finally, while the United States largely closed its doors to immigrants during the 1920s, Stanley Bruce encouraged almost 300,000 British citizens to move to Australia, declaring that he wanted "men, money and markets" from the mother country.

Australia also underwent a few geographical changes worth mentioning during this period. In 1915 Jervis Bay, a bay on the southeast coast, was detatched from New South Wales and declared a separate territory, not part of any state. The idea was that the future capital, Canberra, should not be dependent on any state for access to the sea. Today Jervis Bay is still separated from the states, and while it contains a naval base and a national park, Australia did not build the commercial port you might expect, and even a promised railroad linking Canberra with Jervis Bay was never built. In Canberra, the first Parliament House opened for business on May 9, 1927, meaning it replaced Melbourne as the seat of the federal government on that day. However, the whole city of Canberra was far from complete, and over the next two decades, the Great Depression and World War II delayed or stopped construction projects in the new capital. In the late 1940s Canberra was described as "several suburbs in search of a city," so during his second term as prime minister, Robert Menzies would make finishing the capital a priority.

In February 1927, the Northern Territory was split in two, with the dividing line at latitude 20° S. The two new territories were called North Australia and Central Australia, with their capitals at Darwin and Alice Springs respectively. However, this did nothing to make the land a more desirable place, so in June 1931 the land went back to simply being the Northern Territory. And over the course of the early twentieth century, several places near Australia, mostly minor islands, were transferred from British to Australian rule, for much the same reason that southeastern New Guinea was transferred before World War I: convenience. These islands were Norfolk Island (1914); Ashmore Island and the Cartier Islands (1931); the Australian Antarctic Territory (1933); and Heard Island, the McDonald Islands, and Macquarie Island (1947).

The excitement of the 1920s ended with the economic collapse of the Great Depression. The Australian economy was largely dependent on exports of wheat and wool, and the prices for those commodities now plummeted. Manufacturing also declined, because there now wasn’t much demand for the goods, and unemployment brought shame and misery all over the country. At the Depression’s worst point, in 1932, estimates of the portion of the working population without jobs ranged from 17 to 41 percent, with twenty-nine percent as the figure most often cited; whatever numbers you believe, you have to admit it was an awful time.

Elections for the House of Representatives, held on October 12, 1929 were won by the Labor Party, and they put a new prime minister in office, James H. Scullin. Too bad for the winners; this happened just days before the Great Depression began! They could not deal with this huge challenge for several reasons, like inexperience, and lack of control over the Senate and the banking system. Government policies designed to encourage inflation or deflation ended up splitting the Labor Party again, and with the next election, in 1931, the winners were former Nationalists and defecting Laborites, who got together to form a conservative group, the United Australia Party. The new party’s leader, Joseph Aloysius Lyons, became the next prime minister.

Like the Americans, Australians tried to escape the worries of the Depression years through entertainment, especially with sports. Cricket lifted their spirits a lot; an extraordinary cricket player named Donald Bradman (1908-2001) broke the highest batting record in 1930, with 452 runs not out in 415 minutes. When he retired in 1949 he had an unsurpassed career average of 99.94 runs, making him the Australian equivalent of Babe Ruth. Meanwhile in horse racing, a horse named Phar Lap became another Australian legend, entering 51 races and winning 37 of them. Phar Lap was shipped to North America, and in early 1932 he won a race near Tijuana, Mexico, the Agua Caliente Handicap, but not long after that he suddenly fell ill and died. Ever since then Australians and equine veterinarians have debated whether the champion horse was poisoned, or fell victim to an intestinal infection.

Whereas the United States tried to get out of the Depression by having the government stimulate the economy, and New Zealand concentrated on reducing the suffering (see below), the Lyons government followed a traditional fiscal policy, which emphasized stability and growth. Wages were lowered while the cost of raw materials remained cheap, industry tariffs remained up, and manufacturing replaced agriculture as the main component of the economy. While recovery was not complete when World War II began, unemployment was down to 11%, compared with 17.2% in the United States, so in that sense, Australia’s belt-tightening approach was more successful than the American "New Deal."

Lyons died in office in 1939 and was succeeded by his Attorney-General, Robert Gordon Menzies. Menzies’ first term in office (April 1939-August 1941) coincided with the beginning of World War II. For most of the late 1930s, Australia, like Britain under Neville Chamberlain, followed an appeasement policy with belligerent nations like Germany and Japan, not only to prevent war, but also because Japan had become a major customer of Australian wool. Nevertheless, when World War II began, the response was the same as it had been with World War I; on the day that Britain declared war on Germany (September 3, 1939), Australia and New Zealand declared war, too. But aside from mobilizing the armed forces, sending troops to fight on Britain’s side in the North Africa campaign, and a four-month visit to Britain in 1941(9), Menzies would not get to lead Australia during the war. Not only was Germany too far away to be a direct threat to Australia, but while Menzies was away, his work at home wasn’t getting done.(10) Thus, when Menzies returned, he found he had lost all support, and was compelled to resign. Neither the United Australia Party nor its partner, the Country Party, could find a suitable replacement for Menzies (the ancient former prime minister Billy Hughes was considered at one point), and in the next election, voters returned the Labor Party to power. The real threat to Australia came from Japan; first Japan joined the German-Italian alliance in 1940 (the so-called "Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis"), and then in December 1941, Japan attacked British and American outposts in the Pacific, starting an offensive that would bring the Japanese to Australia’s doorstep.

The Cactus War and the Emu War

One lesson nature has taught us (the hard way), is that it is often a bad idea to introduce an animal to a strange but friendly environment, where natural enemies do not exist. This is especially the case in the South Pacific, because islands support a limited number of species, and thus have fragile ecosystems. And wildlife on even the largest landmasses is vulnerable; we know that from the number of species that have become extinct in Australia and New Zealand, during the past few thousand years.

The prickly pear cactus shows us that plants introduced to a new environment can also run wild. Because plants tend to grow in one spot for their whole lives, most people do not give them much attention until their seeds and offspring spread. Unlike other types of cactus, the prickly pear has a modular design, growing several leaf-shaped "pads" instead of a single trunk. This makes it easy to propagate; if a pad breaks off, it can grow roots and become a new plant.

Prickly pears were introduced to Australia at a very early date; it looks like they may have even been brought on one of the ships from the First Fleet. The idea was to start a local industry in cochineal, a red dye made from insects that eat prickly pears. And there was a demand for red dye, to make the famous red coats of British army uniforms. Over the course of the nineteenth century, no less than ten prickly pear species were imported from Mexico. By then synthetic red dyes were available, but other uses were found for the cactus. Because the outback is an ideal environment for cactus to grow in, ranchers found that they could plant fences instead of building them, and during times of drought, prickly pear pads can be fed to livestock, once the spines are removed. And the fruit is fit for human consumption; Native Americans regularly eat it.

No cactus grows quickly, and though it was deliberately spread during drought years, the explosive expansion of the prickly pear across the outback caught everyone by surprise. By 1900, it covered 10 million acres, filling up most of the pastureland in Queensland and spreading into New South Wales; at the peak of the plant epidemic in 1925, it covered an estimated 60 million acres, an area larger than Great Britain! Wherever prickly pears made up more than just a hedge, they became weeds that rendered most of the land useless, and workers and farm/ranch animals kept getting injured by cactus spines. Attempts to control prickly pear by hand required a tremendous amount of work, while poisons were both dangerous and expensive. One 1940 study estimated that removing thick patches of prickly pear by mechanical or chemical means cost six times as much as the land underneath was worth.

Can it get any worse than this? From The Great Cactus War.

Scientists traveled to other countries where the prickly pear grows, to find out what controls it there. In Argentina they found the cactoblastis moth, an insect that eats nothing but cactus, and brought back 2,750 moth eggs in 1925. The moth’s caterpillars were bred and delivered to cactus-infested areas, and they killed off the prickly pear even faster than it had spread across those acres. Within seven years, the prickly pear was no longer an obstacle to settling and farming the outback. Best of all, the prickly pear was removed at a small fraction of what it would have cost if non-biological methods had been used, and because of its restricted diet, the cactoblastis moth has not disrupted the ecology like other animals introduced to Australia.

What you read next will probably go down as the silliest story in this work. Elsewhere I have talked about stupid battles and wars; for the South Pacific, the stupidest conflict was the brief Emu War of 1932. Be warned, what you are about to read did not come from The Onion.

Here, in one picture, is everything you need to know.

During World War I, the Australian government was looking for a good way to reward the troops for their military service, and maybe provide jobs for them, since most were not likely to stay in the armed forces after the war ended. They decided to offer tracts of land and money to any ex-soldiers who wanted to become farmers, and 5,030 veterans accepted it. However, some of the land was in desolate Western Australia, where growing wheat and raising sheep is only barely possible. Besides the desert conditions, it was hard to turn a profit during the Great Depression, when a bad economy kept the prices of their crops down. And on top of that was the emu problem.

I mentioned in Chapter 1 that flightless birds have a hard time surviving when humans move into their neighborhood. That is the case with the ostrich-like emu, and in most of Australia they are a protected species for that reason. But not in Western Australia; that state took emus off the protected list in 1922, after they developed a taste for wheat, and started eating up the crops of the farmers. They were also attracted by the water supplies set up for the farms. Finally, when the emus ravaged a crop, they left holes in the fences that let in the pesky rabbits. Being former soldiers, the farmers resorted to shooting the birds, killing 3,000 in 1928 alone. It wasn’t enough, and in 1932 an estimated 20,000 emus descended on the farming districts of Chandler and Walgoolan, a few miles inland from Perth.

Normally the Minister of Agriculture is expected to deal with a farm-related crisis, but the ex-soldiers did not trust him, and instead sent a delegation to the Minister of Defence for help. This gentleman provided two Lewis machine guns, 10,000 rounds of ammunition, and two soldiers to use them. Major G. P. W. Meredith would lead what was now a military expedition, and he would also bring a news journalist to film it. Against battle-hardened soldiers and up-to-date weapons, what could a flock of dumb birds do, even a very large flock of very large, dumb birds? Naturally everyone expected this war on emus would be a glorified turkey shoot.

They had underestimated their opponents. You can see it in how 10,000 bullets were issued for an expedition that was expected to kill twice as many birds. On the first day, November 2, the gunners shot at a group of fifty emus, but they dispersed, running off in different directions, and the few emus hit by bullets were only wounded, thanks to their thick skins. Two days later, they tried to ambush a thousand emus near a dam; this time they killed twelve of the enemy, the rest scattered again, and then the gun jammed.

Over the next few days the birds were so hard to locate and corner, that it seemed they knew the techniques of guerrilla warfare. One army observer on the fourth day sadly remarked:

"The emus have proved that they are not so stupid as they are usually considered to be. Each mob has its leader, always an enormous black-plumed bird standing fully six-feet high, who keeps watch while his fellows busy themselves with the wheat. At the first suspicious sign, he gives the signal, and dozens of heads stretch up out of the crop. A few birds will take fright, starting a headlong stampede for the scrub, the leader always remaining until his followers have reached safety."(11)

At one point it looks like Major Meredith couldn’t take any more humiliation from the birds, because he mounted one machine gun on the back of a truck so they could chase them. How did that work? Not too good! The emus could outrun the truck, the ride was so bumpy that the gunner couldn’t aim at anything, and the chase ended when the truck hit an emu and its body got tangled in the steering wheel, causing the truck to go off the road and crash into a fence.

After that there were no more spectacular showdowns between man and bird, just isolated skirmishes that yielded about 100 kills a week. One month after he started, Meredith reported that 986 birds had been killed, and 9,860 bullets had been expended -- it took exactly ten shots to kill each emu. The government recalled Meredith on December 13, and the Emu War was over. Because of the bad press generated and the embarrassing shortage of dead birds, the government declared that the emus won; imagine how bad it would have looked if there had been any human casualties! Afterwards, Meredith expressed an admiration for his feathered enemies:

"If we had a military division with the bullet-carrying capacity of these birds it would face any army in the world. They can face machine-guns with the invulnerability of tanks. They are like Zulus whom even dum-dum bullets could not stop."(12)

Still, something had to be done about the emus. The government found it got better results when it just gave the farmers the bullets they needed to hunt the birds, and offered a bounty for each one shot. In 1934 the locals bagged 57,034 emus, and by 1960 the population had been culled to a point that the emu could become a protected species again.

New Zealand: Between Liberal and Labour

We noted in Chapter 3 that when New Zealand gained dominion status in 1907, its people acted like they were still a British colony. Most non-Maori felt strong ties with the mother country, because they came from the British Isles or their families did, not too many years earlier, and Britain remained the largest customer of New Zealand goods, especially the meat and dairy products that could now be shipped overseas. New Zealanders taught British history and culture to their children, and several of them, like the physicist Ernest Rutherford and the author Katherine Mansfield, contributed to British culture as well. However, the government had mixed feelings, because the Royal Navy remained the country’s first line of defense. Generally, Wellington trusted Conservative (Tory) governments in London, but not Labour governments; the British Labour Party counted too much on the untested League of Nations to keep the peace, while Wellington followed a realistic foreign policy that did not trust any international organization.

New Zealand’s first political party, the Liberal Party, did not last long after the transition from colony to dominion, so the party that replaced it, the Reform Party, ran the country for sixteen years (1912-28). Overall the Reform Party was more conservative than the Liberals, though it had no official platform or agenda; it had formed simply to oppose the "Tammany Hall" organization that the main Liberal prime minister, Richard Seddon (see Chapter 3), had formed. As it turned out, though, the first Reform prime minister, William Massey, was a better organizer of coalition governments and the Cabinet than even Seddon had been. It was a skill he needed, for the Reform Party did not hold a majority of seats in Parliament until after the 1919 elections.

Massey was nicknamed "Farmer Bill" because he had been a farmer before becoming a politician, and because he took the side of the farmers, in disputes between farmers and urban workers. This was especially the case during two major strikes, a miners’ strike in 1912 and a waterfront strike in 1913. Massey broke up the latter strike by sending baton-wielding constables on horseback, most of them freshly recruited farmers; their heavy-handed approach earned them the name "Massey’s Cossacks." But after World War I began, domestic issues had to take a back seat to what was happening abroad. During the war Massey took two entended trips to Europe, lasting a total of fifteen months, and after the war ended he went again, to take part in the Paris Peace Conference and the signing of the Versailles Treaty (December 1918-June 1919). Then in the early 1920s he dealt with a recession, inflation and a railroad strike, before dying of cancer.

Massey’s immediate successor, Francis Bell, held the PM spot for two weeks before a caucus ballot within the Reform Party chose Joseph Gordon Coates as the official replacement. Coates was a war veteran and had held several positions in the Cabinet, most recently as native minister, where he settled land claims and opened investigations into the confiscations of Maori land after the wars of the 1860s. Because this was the 1920s, Coates was quickly nicknamed the "Jazz Premier," and when general elections were held six months after he took over, the Reform Party won its largest majority yet. Instead of talking about policy issues, they used an American-style ad campaign, where they posted handsome pictures of Coates all over the place with short slogans like "Coats off with Coates." However, the goodwill Coates had when he came into office soon faded, because he could not get a sluggish economy to recover from its recent dip, and the reforms he introduced alienated conservatives within his own party, including his campaign manager. In 1928 the surviving Liberals reorganized themselves as the United Party, and when elections later in the same year resulted in a tie, the United Party formed the next government by joining forces with another new party, the Labour Party.

Rather than fight over which of their faction leaders should become the next prime minister, the United Party brought back someone who had held that job twenty years earlier -- Joseph Ward. But Ward was now seventy-two years old, and in such poor health that he got even less done than he did the first time he was prime minister. In May 1930, seventeen months after taking office, he was compelled to step down, and died forty days later. His successor, George William Forbes, had the misfortune of taking charge right after the worldwide Great Depression began; the US stock market had crashed in October 1929, and the collapsing American economy soon dragged down the economy of every nation it traded with. Unemployment soared, and export prices fell to the point that some farmers earned nothing between 1930 and 1932.

No government had ever dealt with an economic slump on a scale as large as this, and when the Labour Party pulled out of the ruling coalition, a new coalition formed between the United and Reform parties. Under this arrangement, Forbes remained prime minister, but some felt that the Reform Party leader, former prime minister Gordon Coates, had more power. Whether or not this was the case, the way Forbes dealt with the Depression was described as "apathetic and fatalistic"; opponents accused him of paying too much attention to the advice of friends. All he and the government could do was cut spending and organize the unemployed in work camps, where they built/repaired roads, worked on farms, or did park improvements. These efforts were so ineffective and unpopular that in the 1935 elections, the voters turned out the United-Reform coalition and elected a Labour Party government in its place.

The Labour Party had been around since 1916, when several socialist groups and trade unions got together as a political party for the working class. At first their platform was blatantly socialist, and thus too radical for the voters who weren’t already members. Over the next two decades, though, the new party’s stand on the issues moderated until it abandoned socialism completely in 1927, so with each election they grew more popular and gained more votes. Finally, they won in 1935 by taking 53 of the 80 available seats in Parliament.

The Labour Party’s solution for the Great Depression was extensive social legislation, that had much in common with Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s "New Deal" in the United States. The list of policies enacted is too long to include here; we will just mention the highlights, like:

- A state housing program to build 29,000 rental homes for low-income workers.

- Social security for the elderly, widows, and orphans, with family benefit payments (1938).

- A minimum wage (1936).

- A 40-hour workweek, with unemployment and health insurance (1938).

- Socialized medicine (1941).

"Under A Jarvis Moon"

Before we get into the World War II narrative, a few words should be said about the introduction of aviation to the Pacific. Readers probably know that the first heavier-than-air-aircraft (as opposed to lighter-than-air balloons and dirigibles) was invented by the Wright Brothers, two American bicycle mechanics, in 1903, and between the World Wars, commercial air transportation was introduced. However, the age of jet airliners did not begin until 1957, with the first flight of the Boeing 707. Before that time, airplanes were smaller, propeller-driven, and had shorter travel ranges. Therefore they did not carry enough passengers to replace passenger travel on ocean liners, and like the steamships of the nineteenth century, they had to make more than one stop to cross the Pacific Ocean. A typical air crossing from the United States, for example, might travel from Los Angeles to Honolulu to Wake Island to Guam to Manila, before reaching a destination on the Asian mainland like Hanoi.

Because of the need to build more airstrips in the Pacific, the United States government took a new look at the uninhabited atolls, especially the equatorial Line Islands, and Howland and Baker Islands, located about 1,100 miles to the west. This area is halfway between Australia and the US mainland, so ships passed through here, and it was expected that an air route between the two countries would pass through here, too. Today eight of the eleven Line Islands belong to the nation of Kiribati, but originally all of these islands had been claimed by the Americans, through the Guano Islands Act of 1856 (see Chapter 3). However, with no one living here, and few visitors dropping in, all territorial claims were unenforced. American, British and New Zealand companies came to mine the guano deposits, and the British staked claims of their own, but aside from the mining, nobody did much with these atolls.

In 1935 the United States began a colonization project, sending a few young Hawaiians and furloughed army personnel to live on Howland, Baker and Jarvis Islands. They did not stay permanently, but were replaced by a fresh group every three months. For the Hawaiians it was like a camping trip, while the non-Hawaiians did not enjoy it as much, so after the first group was done, mostly native Hawaiians were sent. Because of the competing British claim, the project was kept secret for the first year, until US President Franklin D. Roosevelt publicly re-asserted the American claim in 1936. On Howland Island they prepared an airstrip for Amelia Earhart (see the next section). The story of the settlers and their settlement, Millersville, was the topic of a 2010 documentary, "Under A Jarvis Moon." We will finish that story after covering how Amelia Earhart came to the central Pacific.

The Flight of Amelia Earhart

One of the pioneers in the early years of aviation was Amelia Mary Earhart (1897-1937?), a famous American pilot and author. For most of the 1920s she worked a variety of jobs, and flying was a hobby. That changed in 1928, when she rode on a plane from Newfoundland to Wales, becoming the first woman to fly across the Atlantic. Though a male pilot and co-pilot did the actual flying, and she said she felt she was "just baggage, like a sack of potatoes," the achievement got the three of them a tickertape parade in New York City and a reception with US President Coolidge in the White House. After that, flying was always Earhart’s main job, and she went on to set a number of records (e.g., first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic in 1932), and won several awards, including a gold medal from the National Geographic Society, and the Distinguished Flying Cross -- the first time both awards had been given to a woman.

Amelia Earhart.

The part of this story which involved the South Pacific came in 1937, when Earhart tried for a new record -- to become the first woman to fly around the world. For the first attempt, in March, she flew successfully from Oakland, California to Honolulu, Hawaii, but the plane rolled while trying to take off for the next leg of the journey, suffering so much damage that it had to be shipped back to California for repairs. When she was ready to fly again, in June, she chose to take a west-to-east course, due to changed weather patterns. Over the next month, she and her navigator, Fred Noonan, flew without incident across the US, Caribbean, northern South America, Africa, southern Asia, and Australia.(14) The last successful stop on the circumnavigation attempt was at Lae, New Guinea, on July 2, 1937. They had gone 22,000 miles so far, and had 7,000 miles left to go. From Lae the plan was to fly to Howland Island. This was more than 2,500 miles away, at the airplane’s maximum range; non-essential items were removed from the cargo to make room for extra fuel, and three US ships, including a Coast Guard cutter, were enlisted to help guide the plane to its destination. If they made it, they would be more than halfway to Hawaii, and the longest flight on the journey would be completed. Instead, there were difficulties with radio communications on the flight, and it appears that an error in navigation, despite all the precautions, caused the plane to miss Howland Island, for Earhart and Noonan were never seen again. Search parties were immediately sent to that part of the Pacific, but they found nothing, and a California court declared Earhart legally dead in 1939.

Since 1937, the fate of Amelia Earhart has been called one of the world’s greatest unsolved mysteries; Americans view it the same way that the French view the ill-fated Lapérouse expedition, that disappeared 149 years earlier. By now there has been more written about her disappearance than about her life; books, movies and TV shows have all speculated on what happened. Some have suggested, for instance, that US President Roosevelt sent Earhart to spy on the Japanese, or that the Japanese captured her and forced her to broadcast propaganda, as "Tokyo Rose" during World War II. Still others think she committed suicide by deliberately crashing the plane in the Pacific.

At this time, the most likely theory is the "Gardner Island hypothesis." According to this, after the airplane’s radio failed, Earhart and Noonan went on to the Phoenix Islands, 350 miles southeast of Howland Island, and landed on Nikumaroro, then called Gardner Island. They lived as castaways for a while, but weren’t rescued, and eventually they succumbed to one of many fates: injury, illness, bad food or a lack of fresh water. Then at some point, storms washed most of the plane’s wreckage into the nearby sea.

What evidence exists for this theory? Well, Gerald Gallagher, a British Colonial Service officer, visited this island in 1940 and found a number of objects that can be associated with Earhart. These included a woman's shoe, a pocket knife, an empty bottle, and a sextant box whose serial numbers matched the type known to have been carried by Noonan. Most important was part of a skeleton, which was subsequently identified as belonging to a woman with Earhart’s measurements. Unfortunately the bones were sent to Fiji and lost after that, so as with the skull of Pemulwuy (see Chapter 3), we cannot give them a proper burial until they turn up again. We believe the reason why only a partial skeleton was found is because Nikumaroro has a colony of giant coconut crabs, and being scavengers, they probably made off with the rest of the remains.

Coconut crabs are big enough to star in scary photos.

Other visits to Nikumaroro have produced more evidence. A piece of aluminum found in 1991 has been identified as a patch placed on Earhart’s airplane, to replace a missing window. In 2012 a cosmetic jar of freckle cream was found; this is something only a white woman is likely to have. Thus, for some people, including the author, the Amelia Earhart mystery has been solved. However, not everyone is convinced as we go to the press.

Earhart’s disappearance reinforced the idea that there should be an airport somewhere in the middle of the Pacific. In 1937 the British turned their attention to the Phoenix Islands, and claimed them as an addition to their Micronesian colony, the Gilbert & Ellice Islands. One year later the United States put forth a counter-claim to Canton and Enderbury, the two largest islands in the Phoenix group; their size made them the best places for an airport and the buildings that would go with it, like a hotel for passengers staying overnight, a power station, a clinic, and a school for the airport workers’ children. The rivalry was settled in 1939, when the US and UK agreed to joint rule for the next forty years, calling it the "Canton and Enderbury Islands condominium." Also in 1939, Pan American World Airways (Pan Am for short) built the "Canton Island Airport" for their flying boat service, and both civilian and naval aircraft used it for trips between North America and the South Pacific, stopping here on the Honolulu-to-Fiji air route.

Meanwhile, the American settlements founded a few years earlier (on Howland, Baker and Jarvis Islands) were forgotten by almost everybody. Japan launched air raids on December 8, 1941, the day after the battle of Pearl Harbor, which killed two settlers on Howland, and the other settlers were evacuated in early 1942. Those islands have had no permanent residents since then, and now they are wildlife refuges, part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

During World War II, Canton Island Airport was restricted to military travel, and while the Japanese attacked it more than once, they never tried to capture it. After the war, in November 1946, civilian airline service resumed. At the airport’s peak, in 1955, Canton had about 280 residents, but then in the late 1950s, the introduction of long-range jet airliners made stopping here unnecessary. In 1965 the airport was closed except for use in emergency landings. A station for tracking missiles and orbiting spacecraft was set up on Canton in 1960, and it was used until 1976; its closing marked the end of the American presence on the island. With the independence of Kiribati in 1979, the Anglo-American condominium was terminated, so Canton and Enderbury could join the new nation. Canton Island’s spelling was changed to the present-day Kanton, and today there are only about two dozen residents, who were relocated here from Kiribati’s more crowded islands.

This is the end of Part I. Click here to go to Part II.

FOOTNOTES

1. April 25, the day the battle of Gallipoli began, is now a holiday in Australia & New Zealand to remember their fallen troops, called Anzac Day.

2. The New Zealand forces included more than 2,200 Maori, and 500 Pacific Islanders from places like Niue. Britain also sent a Fijian labor unit to Europe, which performed only non-combat duties.

A Fijian chief, Ratu Lala Sukuna, tried to enlist in the British army, feeling that the British would only respect natives who fought alongside them. At this time, the British thought recruiting natives for combat duty would set a bad precedent, and thus wouldn’t have him, so he applied for the French Foreign Legion, was accepted, and fought in the French army until he was wounded in 1915. He was forced to return to Fiji after this, but was awarded the Croix de Guerre for his trouble, and joined the labor unit mentioned above when he recovered. Where there is a will, there is a way!

3. Ormond Burton, A Rich Old Man (an unpublished autobiography), pg. 138.

4. The Americans did not know at the time that World War II would get in the way, forcing independence to be postponed exactly one year.

5. A couple other things about Hawaii’s cultural development should be mentioned. Honolulu’s official natural history museum, the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, was founded even before annexation, in 1889. And the University of Hawaii got started in 1907; this was the first university established anywhere in the South Pacific, besides Australia and New Zealand.

6. The information in the past two paragraphs came from the article "Sumsuma (1903? - 1965)," by Bill Gammage, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 12, Melbourne University Press, 1990, p. 139.

7. Sālote is not a Tongan-language name; it is what you get when Tongans say the English name Charlotte.

8. There are three islands in the Pacific called phosphate rock islands, because they are made up largely of this valuable mineral. Nauru and Ocean Island are two of them; the third is Makatea in French Polynesia.

9. Some Australians believe that Menzies stayed abroad so long because he was a candidate to become the next prime minister of Britain, should Winston Churchill fail to keep the job for any reason. There is no evidence backing up this theory, though.

10. German activity in the vicinity of Australia was limited to a few commerce raiders, in late 1940 and 1941. The main encounter took place on November 19, 1941, when the Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney met a ship off Australia’s west coast that tried to pass itself off as a Dutch merchantman. It was really a German cruiser, the Kormoran, and a half-hour battle followed which sank both ships. The Sydney went down with all hands, while 318 German sailors, almost 4/5 of the Kormoran’s crew, were found in lifeboats and interned in prisoner of war camps for the rest of the war. The actual location of the battle was unknown until the wrecks of the two ships were found in 2008.

11. From Scientific American, The Great Emu War: In which some large, flightless birds unwittingly foiled the Australian Army.

12. "New Strategy In A War On The Emu," from The Sunday Herald, July 5, 1953.

13. David Hackett Fischer, Fairness and Freedom: A History of Two Open Societies: New Zealand and the United States. ISBN 9780199912957, Oxford U.P., copyright 2012, pg. 368.14. The Australian equivalent of Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart was a pilot named Sir Charles Kingsford Smith. He had already flown around Australia in 1927, and in 1928 he made the first flight between the US and Australia, using an airplane named the Southern Cross, with stops in Hawaii and Fiji on the way. Also in 1928, he made the first crossing of the Tasman Sea by air, flying from Sydney to Christchurch and back. However, in 1935 he disappeared on a night flight between India and Singapore, so when Earhart attempted her globe-circling journey, Smith wasn’t around to act as a rival.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of the South Pacific

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|