| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A General History of the Middle East

Chapter 15: SETTING THE STAGE FOR TODAY'S CONFLICTS

1914 to 1948

This chapter covers the following topics:

The Reluctant Central Power

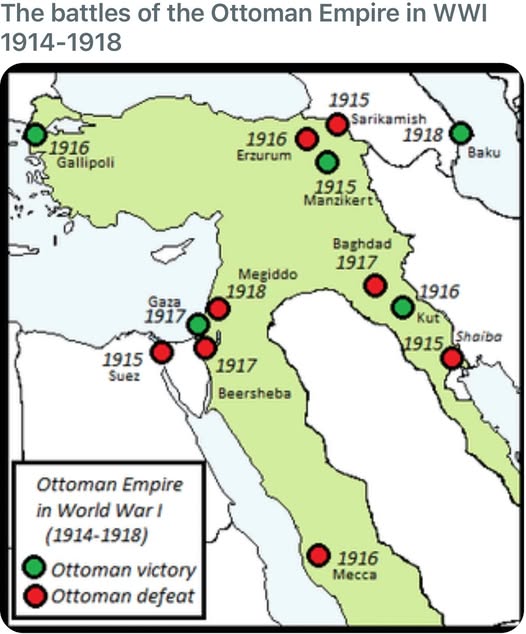

In the summer of 1914 Europe exploded into the chaos of World War I. At first the European powers did not give the Turks much thought. After all, the Ottoman Empire had just gone through two devastating wars in the Balkans, and many Turks, including Talaat Bey, wanted nothing more than some time to rest and recuperate. But as it turned out, the war engulfed an area so large that no major power could sit it out. Once it got involved, the Turkish army won few battles, but it served a useful purpose by tying down more than a million Allied soldiers, men who probably could have shortened the war had they instead gone to the main battlefields of Europe.

When the war began, it was unclear which side the Turks would take. The Allied nations (Britain, France, Russia, and several smaller states) had the advantage in ships, resources, and manpower, and some thought the Turks would play it safe and support the Allies for that reason. On the other hand, Enver Pasha and many of his comrades were pro-German, and they would not join any alliance that included Russia.

A strange set of circumstances decided the issue. In the summer of 1914 there were two German cruisers in the Mediterranean, the Goeben and the Breslau. Their mission in case of war was to sink the French transports carrying reinforcements from Algeria to Europe. Accordingly, when they received news on August 3 that Germany and France were at war, they sailed west and bombarded the Algerian ports of Philippeville and Bone. Then they disappeared into the night and fog, with the British Mediterranean squadron (12 cruisers and 16 destroyers) in pursuit. Later they sighted the two cruisers, this time steaming east. The British ships followed, but not too closely. If the Goeben and the Breslau did not attack Allied shipping or try to slip past Gibraltar into the Atlantic, there would be plenty of time to hunt down and sink them.

However, the Germans had other ideas. They sailed through the Dardanelles with Turkish permission, and dropped their anchors in the harbor of Constantinople. Since the Ottoman Empire was supposedly neutral, the British ambassador protested furiously; Enver Pasha responded by saying there was little else he could do, since the capital was defenseless under the guns of the ships. A few days later Turkish neutrality was restored by a trick; the German sailors put on Turkish uniforms and fezzes, and they sold their ships to the Turkish navy! The Germans stayed in the harbor for two months; finally they got bored, sailed into the Black Sea, and attacked the Russian port of Odessa (October 28). Thus, the Ottoman Empire entered the war on the side of the Central Powers: Germany, Austria, and later Bulgaria.

Armenian Holocaust

The first thing the Turks did after entering the war was expected; they proclaimed a jihad against the empire's foes. This was supposed to cause unrest in the Moslem colonies of the Allies, and mutinies among Moslem soldiers like the Indians in the British army. Yet few non-Ottomans responded. The typical Egyptian, for example, would say, "We wish the Turks all success--from afar," with emphasis on the last two words. For the sultan's call to have any effect, he would have to get the Sharif of Mecca, Hussein ibn Ali, to second the motion. Instead, Hussein stalled, arguing that if he made the call, he would risk bombardment of Jedda by the British navy. Meanwhile the Sharif sent out diplomatic feelers to the British in Egypt, to see if the Arabs could get a better deal from the Allies.

The second Ottoman act in the war was to march against the Russians in the Caucasus, hoping that by doing so they could incite anti-Russian uprisings among Azerbaijanis and other Moslem tribesmen. Again the expected rebellions did not take place, and by January 1915 the Turks were suffering terrible losses. Spring saw the Russians go on the offensive, and on May 14 they captured the city of Van, with the help of some Armenian guerrillas who immediately proclaimed Van the capital of an independent Armenian republic. Thousands of Armenians flocked to Van, until the Turks recaptured the city in mid-July. Inflamed by the jihad, and furious that the Armenians had gone over to the enemy, local officials and troops launched a massacre, butchering the men, and robbing and raping the women before leaving them to die. An American medical missionary reported that 55,000 Armenians were killed in Van alone.

The government announced at this point that it would deport the Armenians to provinces away from the war zone. Some relocations existed only on paper. When one conscientious officer asked Talaat Bey where he was supposed to send a group of Armenians, he received a chilling reply: "The place they are being sent to is nowhere." Of the half million Armenians who did get moved, only 90,000 survived the war. More than 600,000 Armenians were killed in Armenia itself, and many more fled the region. "I have accomplished more toward solving the Armenian problem in three months than Abdul Hamid accomplished in thirty years," Talaat Bey was said to have boasted.

The Armenian holocaust was the worst, but not the only move taken by the Young Turks to strengthen the country internally. They abolished more than three hundred years of trade concessions to the Allies, and also the autonomous status of the Lebanese Christians. Jemal Pasha took command of the troops in Syria and launched an attack against Egypt in February 1915, boasting that he would not return to Constantinople until he had first entered Cairo. However, none of this seemed to help the Turkish war effort. Jemal Pasha's campaign was a pathetic fantasy, and the British had no trouble throwing it back across the Sinai. In January 1916 the Russians resumed their offensive and overran the whole northeastern corner of Turkey. Before they halted (in August 1916), they captured Trabzon (ancient Trebizond), Erzincan, and the towns around Lake Van. There the front stabilized until the 1917 revolutions knocked Russia out of the war.

Gallipoli

By the end of 1914, World War I's main theater, the Western Front (a 475-mile line through Belgium and France), had turned into a bloody stalemate. Up to that point, Belgium, France and Britain had together suffered a million casualties (both killed and wounded), while Germany suffered three quarters of a million casualties. On the other side of Europe, Russia, despite its enormous resources, was in terrible shape, and needed constant aid from Britain & France to keep going. The Germans tried to keep that aid away by closing off the Baltic Sea, and the Turks did the same thing on their front by blockading the Black Sea. When it became clear that the war was not going to be won quickly on the Western Front, the Allies began looking for a way to force open a supply line to Russia, thereby making it possible to strike a critical blow against the Germans in the east. The only promising idea came from Britain's First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. Churchill proposed an assault on the Dardanelles; if the Allies could get through that narrow strait, they could take Constantinople, open up the Black Sea to Allied shipping, and knock the Turks out of the war. In addition, a successful campaign against the Turks was likely to persuade Italy, Greece and Romania, who were not involved in the war yet, to enter on the side of the Allies.

It was a good idea on paper, but carried out disgracefully. In the first place, preliminary attacks on the Dardanelles warned the Turks. In February 1915 British ships bombarded the guns on the Asian side of the strait; the Turkish defenders ran out of ammunition and were about to surrender when the British, unaware of the enemy's condition, turned around and left. A full-scale naval attack on March 18 was called off when three battleships, two British and one French, struck mines at the entrance to the strait. They now made plans to seize the Gallipoli peninsula, on the European side of the Dardanelles.

Ten Allied divisions came ashore on two beaches of the peninsula on April 25, 1915. They found the Turks dug in and better equipped for trench warfare than themselves. Instead of using heavy artillery, the Allies trusted in the great guns of their ships, which turned out to be useless in battering down trenches; they were also vulnerable to hostile submarines. The Allied commander, General Sir Ian Hamilton, mismanaged the entire operation, spending most of his time on Greek islands or British battleships. In his absence subordinates were free to do as they pleased, and he gave no direct, comprehensive orders to anyone. When he did come up with an attack plan in August, it was changed and modified so often that it did nothing but confuse everyone. By contrast, the Ottoman forces were German-trained, and fighting for the very heart of the empire. As a result, the Allied infantry sat on the beaches and suffered month after month until the navy took them off again (in January 1916). By the time it was over the Allies had taken 214,000 casualties, twice as many as the Ottomans. Such was the power of the machine gun--even in Turkish hands--that the farthest inland any Allied troops got was two miles.

Commanding the defense, and seemingly immune to bullets, was Colonel Mustafa Kemal. A veteran of the recent war in Libya, Kemal saw the defense of Gallipoli as his personal crusade, and infected his men with the same spirit. He also understood, more than his Allied counterparts, that this was a war of attrition. "I am not ordering you to attack, I am ordering you to die," he once told his officers. "In the time it takes us to die, other forces can come and take our place."

After the Gallipoli campaign ended, a German advisor, General Otto Liman von Sanders, confessed that only Mustafa Kemal's dogged resistance kept the Turks from retreating. Kemal was hailed as the savior of the Dardanelles when he returned to Constantinople, and hastily reassigned to the Russian front by an envious Enver Pasha, who detested the war's only Turkish hero.

Meanwhile among the Allies, the man who planned the Gallipoli campaign was blamed for its failure. Whether or not you think this was fair, Churchill was demoted to an obscure cabinet post. By the end of 1915, he had resigned even from this spot, picked up a gun and headed to the Western Front, where he spent the next two years as an infantry officer with the Royal Scots Fusiliers. And after he returned to politics he wasn't very important for the next twenty years. With the ghosts of Gallipoli lurking in his past, many observers thought Churchill would never get over it, yet he did and went on to become the man who saved Britain in World War II.

The Mesopotamian Campaign

Another campaign the Allies could have managed better was their invasion of Iraq. It began in September 1914 when a British force from India occupied the oilfields of Persia, presumably to keep the oil away from the Germans. In November came the news that the Turks had joined the enemy, and the Anglo-Indians responded by landing at the head of the Persian Gulf and seizing Basra. The troops were then ordered to march to Baghdad, but they had inadequate supplies and no proper plan for the campaign. It was hoped that Russians coming from the north would join them, but that advance never came. Despite all this they pushed up the Tigris River until they reached the ruins of ancient Ctesiphon in November 1915. At that point the Gallipoli campaign was almost over, allowing the Turks to rush additional divisions into Iraq. The Allies were beaten, driven back to Kut-al-Imara, and surrounded. Three relief expeditions tried and failed to break through the Turkish lines. The Turks also refused an offer of two million British pounds to set the garrison free. Finally the garrison surrendered in April 1916. 10,000 British and Indian troops were captured, and more than 6,000 of them died in the desert as prisoners-of-war.

Reinforcements arrived in the Gulf at the end of 1916, allowing the British to try again. In February 1917 they recaptured Kut-al-Imara, and much of their pride as well. Baghdad was taken in March; by September the Allies had advanced to Ramadi on the Euphrates River and Tikrit on the Tigris. The reason for the whole campaign was never made clear; critics claimed it was mainly done to save face after the failure at Gallipoli.

The last move made by the British was the capture of Mosul, on November 3, 1918. It wasn't done for any military advantage (the Ottoman Empire surrendered four days earlier), but merely to keep the French from getting there and claiming it first.

Behind Closed Doors

For nearly a century Britain had propped up "the Sick Man of Europe"; now the Allies agreed that the sick man must die, for the sin of picking the wrong side. Almost as soon as the Turks had entered the war, plans were made to dismember the Ottoman Empire.

The first agreement was signed in March 1915, when it looked like the Gallipoli campaign would make short work of the Turks. Here Russia was rewarded with all of Turkish Armenia and the land around the Bosporus & Dardanelles (the so-called "Zone of the Straits," which included Constantinople). Ironically, this was the same land which Britain and France had kept Russia from taking on its own in the 19th century (The Crimean and the Russo-Turkish wars). The Allies offered Italy and Greece economic zones or "spheres of influence" in southwestern Turkey if they would join them.

Meanwhile in Arabia, Sharif Hussein was walking a political tightrope. He assured the sultan of his undying support and told him that he was praying for victory against the infidel ("May God lay them low"), but he also kept saying that now was not the time to make the call for a holy war. Simultaneously he exchanged several letters with the new British High Commissioner in Cairo, Sir Henry McMahon. McMahon agreed to "recognize and support the independence of the Arabs," and made vague promises to set up Hashemite-ruled Arab kingdoms in Arabia, Syria, and Iraq after the war. However, there was also a string attached--McMahon told Hussein that the eastern shore of the Mediterranean had a population that was not predominantly Arab, which would exclude it from any future Arab state. Hussein countered by saying that the Turkish vilayets (provinces) of Aleppo and Beirut (northern Syria and Lebanon) were indeed Arab territories, and must be included; McMahon replied that the matter "will require careful consideration." At no point did either of them mention Palestine, Jerusalem, or the Jews. From the Arab point of view the Holy Land had always been part of Syria, so this omission meant nothing to Hussein. Nevertheless, McMahon, with that splendidly imperial attitude that was natural to Englishmen back then, did not take his promises very seriously. This was the first of many misunderstandings that would lead to trouble.

Just as Hussein was double-dealing with the Turks, so Britain was double-dealing with the Arabs, by making secret deals with France and Russia. The result was the Sykes-Picot agreement in May 1916, named after the principal British and French negotiators. This accord divided the Fertile Crescent between Britain and France. Since France had been active in Lebanon before the war, the French laid claim to Lebanon, Syria, and the northern third of Iraq. Britain would get the rest of Iraq, not only for its oil but also because the British government wanted a place to settle Indian immigrants. They declared the Holy Land an international zone, because Russia insisted that it go to nobody at this time. Note that only in the poor, backward Arabian peninsula would the Arabs have real independence. This was not at all what Hussein and the Arab nationalists had in mind. In defense one can only argue that Britain was engaged in a deadly war, and had to put the wishes of its most important allies before everything else.

The Arab Revolt

Wartime politics divided the Arabs. The Imam Yahya of Yemen and Ibn Rashid of northern Arabia were pro-Turkish, while al-Idrisi of Asir and Ibn Saud declared themselves in the Allied camp by the end of 1914. To complete the picture, the sheikhs of coastal protectorates like Kuwait were pro-British, and in Mecca sat Sharif Hussein. Of all these, only the Imam had more than a handful of troops, and none did anything that affected the war before the summer of 1916. For example, in July 1915 the Imam invaded British-held southern Yemen, occupying Lahej but not Aden; Turkish troops remained in Lahej for the rest of the war. Offshore, British ships controlled the Red Sea and blockaded Turkish-held towns along the coast.

As for Hussein, time was running out on his fence-sitting game. When Jemal Pasha's first attack on Egypt failed, he withdrew to Syria and began preparing for a second invasion. While doing so Jemal discovered underground Arab anti-Turkish activities. His response was a wave of repression that earned him the nickname of al-Jazzar, "the butcher." Jemal burned down villages and deported their inhabitants to Turkey; thirty-two prominent Arab civilians were executed; Arab units in the Ottoman army were moved out of Syria and replaced with Turks.

Jemal Pasha also announced that he would send a large Turko-German force through the Hejaz on its way to Yemen. Hussein decided to act when he heard the news. On June 10, 1916, Hussein declared himself in revolt by symbolically firing a rifle at the Turkish barracks in Mecca. The rebels quickly took Mecca and Jedda, but that was the limit of their ability. The ill-trained and ill-equipped Bedouins were brave enough when attacking lightly-armed soldiers, but they often ran away from artillery. After one such episode, the Arabs explained that they had withdrawn "to make ourselves some coffee."

For the Arab revolt to succeed it would need gold, arms, and advice. All that was on the way with an agent named T. E. Lawrence. The illegitimate son of an Anglo-Irish baronet, Lawrence had spent the years before 1914 traveling around the Middle East, studying archeology and Arabic language and history--and incidentally, spying on the Turks. When the war broke out, he used his talents to become a temporary captain in the intelligence service, stationed first in Cairo, and then Jedda in October 1916. There he quickly made up his mind about the Hashemite family. In his book on the Arab revolt, Seven Pillars of Wisdom, he wrote:

"The first, the Sharif of Mecca, we knew to be aged. I found Abdullah the second son too clever, Ali the first son too clean. Zaid the fourth son too cool. Then I rode up-country to Faisal the third son and found in him the leader with the necessary fire."

Prince Faisal now became the leader of the Arab revolt against the Turks. Lawrence learned to wear Arab clothing and ride camels, and thus turned himself into a Bedouin warrior. Together Faisal and Lawrence led successful guerilla raids, blowing up trains and railroad tracks, and attacking isolated Turkish units. Nevertheless, the legend of "Lawrence of Arabia" belongs more to Western literature than it does to Arab history. Lawrence respected Arab culture, but his first loyalty was always to Britain; he wore an Arab headdress not out of love for the Arabs, but because they respected and trusted him when he did. Lawrence wanted independent Arab states in the Middle East because the most likely alternative would have been French colonies (he hated the French as much as he hated the Turks). The reason why books and movies exist about Lawrence is because German and Allied troops were monotonously slaughtering one another in the mud of Flanders, and the Allies desperately needed a hero who could work miracles elsewhere. To most Arabs, however, the "Lawrence of Arabia" story is overshadowed by the betrayal of the postwar settlement.

Promises, Promises . . .

In January 1917 Hussein felt confident enough about his position to proclaim himself king of the Hejaz. In July Lawrence and his Bedouins scored a major victory by capturing the port of Aqaba, on the northeastern tip of the Red Sea. However, in November came two events that poisoned Arab-Western relations, the revelation of the Sykes-Picot agreement and the Balfour Declaration.

When the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia, they gleefully published documents from the Tsar's foreign ministry which were chosen to show the Allies in the worst possible light. They revealed the terms of the Sykes-Picot agreement to the Turks, and the Turks passed them to the Arabs as proof of Christian treachery against Moslems. In those days diplomats were not in the habit of revealing the details of their negotiations, so Allied leaders were offended that this kind of material had been made public. Think of this as an early twentieth-century version of the WikiLeaks scandal, or the Edward Snowden affair, and you'll understand why the revelations from Russia raised a big stink. Hussein was appalled as well, and so was Lawrence, who didn't want the French to have anything!

The Balfour Declaration caused less trouble at the time, but it is more important in how it helped to create the modern Middle East. It came in the form of a letter written from the British foreign secretary, Arthur James Balfour, to a leading British Jew, Lord Rothschild. The key paragraph read:

"His Majesty's Government [sic] view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."

It is unclear today what caused the issuance of the Balfour Declaration, since Britain did not help the Zionists much after the war. Balfour and the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, got along well with Chaim Weizmann, the Zionist leader, but most of the other Jews in Britain (including Lord Rothschild) were not Zionists at all. It may have been because Britain wanted allies anywhere, no matter how few they may be. Or maybe the British wanted to create a friendly independent state next to the Suez Canal. It may also have been a political ploy, done to win the support of American Jews shocked by Russian anti-Semitism, or to divide the support of German Jews for the Fatherland. Finally, most nineteenth-century Englishmen were raised in a Bible-reading Protestant background, and even if they no longer believed in the God of their childhood, they may have found it appealing to bring the Jews back to their promised land after more than two thousand years.

Whatever the reason, Hussein demanded an explanation. The British spent the rest of the war sending diplomats to reassure Hussein and Faisal. On the Sykes-Picot agreement, they said that it was only a proposal, not "carved in stone," and they would probably not implement it anyway, since Russia had already left the war. On the Balfour Declaration, they said that it promised a home for the Jews, not a Jewish state, and that it would be in Palestine, but not necessarily all of Palestine. The Hashemites must have bought it, because afterwards Faisal opined that Jewish immigration would be a positive influence on the Arabs.(1) At any rate, Hussein and Faisal were now so dependent on British support that they could not really disagree with London. Still, the basis for their trust had been destroyed.

Allenby's Crusade

The Arab revolt was useful in that it tied down 30,000 Turkish soldiers on the railway between Amman and Medina, but the decisive anti-Turkish campaign came out of Egypt. It started in June 1916, when the Turks made another attempt on the Suez Canal, only to fail as miserably as they had the first time. The new commander of the British forces in Egypt, Sir Edmund Allenby, then began a counteroffensive across the Sinai, but he moved very slowly, carefully preparing supply lines every step of the way. They laid railroad tracks and water pipes as they moved forward; miles of wire netting were unrolled, because the troops marched faster over that than on ordinary sand dunes. It took until December to reach El-Arish, the main town of the Sinai.

In March and April of 1917 two unsuccessful attempts were made to take Gaza. On the third try Allenby broke through the lines by going for Beersheba, and Gaza finally fell in November. Jerusalem was captured on December 9, 1917, and Allenby was welcomed as a liberator by the people of the holy city. The Turks dug in along a new defense line stretching from Lydda to Jericho, and a cold winter allowed them to stand firm for most of 1918.

Meanwhile in the Caucasus, the Turks brought the war to a triumphant close. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which ended Russia's involvement in the war, returned to the Turks the part of Armenia (the Kars district) taken in 1878. Two months later (May 1918), the three largest ethnic groups south of the Caucasus declared themselves independent of Russia. This encouraged Enver Pasha into an ambitious fantasy involving the conquest of all Transcaucasia. He diverted Turkish troops from other fronts to occupy Georgia, Russian Armenia, and Azerbaijan. And another 400,000 Armenians perished . . .

Victory in the Caucasus came too late to prevent a Turkish collapse everywhere else. In September Bulgaria surrendered to the Allies, cutting off the Turks from Austria and Germany. Then General Allenby broke through the Turkish lines with a well-planned cavalry charge that took Megiddo, allowing him to resume his advance. With Faisal's Arabs guarding his right flank, he marched north and took Damascus and Aleppo in October, while French naval landings captured Beirut and Alexandretta. Faced with this, and famine at home, the new sultan, Mohammed VI, decided to throw in the towel. On October 13 he dismissed the whole CUP government and ordered negotiations with the Allies. An armistice was signed on October 30, 1918, at Moudros on the Greek island of Lemnos. About 325,000 Turkish soldiers had been killed in action; 400,000 had been wounded; 240,000 had fallen to disease; and at least 1.5 million had deserted. Civilians were starving, even if they were wealthy; prices had risen 2,500% since the start of the war.

The Young Turk leaders lived by the sword and died by the sword. After the armistice, Enver Pasha and Talaat Bey sneaked away in the dead of night and left the country in a German torpedo boat. Jemal Pasha lay low at Konya for a year before joining his comrades in exile. True to character, Enver got involved in the Russian Civil War and was killed in Tajikistan, while leading a cavalry charge against the Bolsheviks (1922). Talaat and Jemal were assassinated in two separate incidents by Armenians avenging the loss of loved ones. Back in Turkey, a Franco-British force sailed triumphantly past Gallipoli and took possession of Constantinople.

A Peace to End All Peace

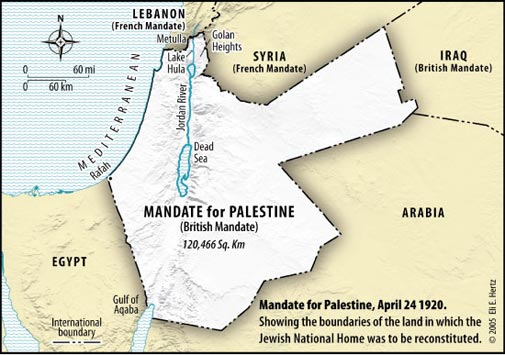

As they had promised, the Allies put the Ottoman Empire on the chopping block when the war ended. The Hejaz went to Sharif Hussein, and since nobody else wanted it, northern Yemen became independent, though Imam Yahya had supported the other side. Britain got to keep Iraq and the southern half of the Levant, now called Palestine, while the French received Syria and Lebanon. The British and French-occupied areas became known as "mandated territories," the idea being that an outside power would govern them until the natives were advanced enough politically to govern themselves. As it turned out, however, the term "mandate" was mainly a sop to the sentiments of the American president, Woodrow Wilson, and his dream, the League of Nations; the British and French ruled the mandates much like their other colonies.

The Palestine Mandate, before Transjordan was split off from it. The southeastern border is explained in footnote #2.

Despite this, Prince Faisal went to the Paris Peace Conference with high hopes, since President Wilson was arguing that the best way to prevent future wars was to create a situation where governments ruled their territories only with "the consent of the governed"--and the governed of the Arab world had not thrown out their Turkish masters only to see Europeans take their place. Using T. E. Lawrence as an interpreter, Faisal expressed his desire for an independent Arab state. However, Wilson did not have the political skills of Britain's Lloyd George or the French premier, Georges Clemenceau, who were mainly interested in revenge against Germany. Wilson sent two Americans to Syria to find out what the sentiments of the Arabs were; when they reported that an overwhelming majority of the Syrians opposed the mandate system, the other Allies simply ignored the report. In the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, the Arabs and their aspirations slipped into the background, while the Allies went ahead with what they had already planned previously.

While Faisal was away the Arab nationalist movement al-Fatat met in Damascus and made its own demands: Faisal should be made king of the whole Levant, an area they called "Greater Syria," and Faisal's brother Abdullah should become king of Iraq. The delegates also denounced the Sykes-Picot agreement, the Balfour Declaration, and the whole idea of mandates. This did not change Anglo-French opinion, and in December 1919 French troops arrived in coastal Syria to replace the departing British. Driven to desperation, the Arab congress proclaimed all of "Greater Syria" an independent kingdom in March 1920. Yet it was a very shaky kingdom, and when the French marched on Damascus in May, Faisal surrendered and ordered the disbanding of his army. The French general, however, would not let the Arabs get off that easily, and overran all of Syria with tanks and planes. Faisal departed for London at the end of the year, a sad and pathetic figure invited by an embarrassed British government.

The Greco-Turkish War

The Turks nearly suffered the same fate at Allied hands as the Arabs did. That they didn't was due to the willpower and drive of one man, the hero of Gallipoli, Mustafa Kemal. During the last months of the war he had led the Turkish Third Army in a successful withdrawal from the hills of Samaria. After the war ended, many Turkish troops were loose in central and eastern Turkey, far away from the reach of the nearest Allied force. The Allies told the sultan to send a Turkish general into the region, to pacify it and receive the surrender of those troops. Kemal used his military record to get himself appointed to that job, as Inspector General of the Ninth Army. On May 16, 1919, he sailed to Samsun, a Black Sea port, to begin a mission that turned out to be quite different from what the sultan and the Allies had in mind. And not a moment too soon; the day before he sailed the Greeks began a project of their own--the conquest the Aegean's eastern shore--by landing troops at Smyrna.

Kemal arrived to find that the Ninth Army no longer existed, and immediately began organizing a new force. He also held congresses at Erzerum and Sivas, where he announced his intention of making a radical break with the past. Since the sultan was now a prisoner of the Allies, he argued, any command issued by him was no longer valid. The Turkish people would have to create a new state to save themselves from the Allies, especially the Greeks. Angora, a textile-producing town right in the center of the Anatolian peninsula, became the capital of Kemal's nationalists. Where Kemal was in charge, the sultan could no longer command--and neither could the Allies.

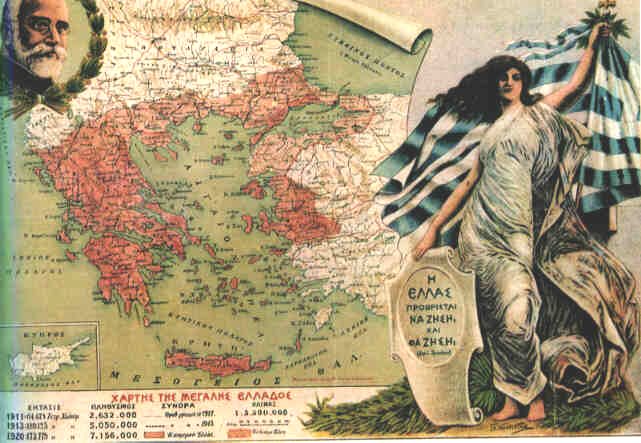

It took a whole year and a half for the Allies to agree on what to do with Turkey. They unveiled the final document, the Treaty of Sevres, in May of 1920. Most of the Turkish homeland, the Anatolian peninsula, would have to be left to the Turks, of course, but President Wilson felt that the Armenians deserved a state of their own in the northeast. In addition, the French wanted the land next to their Syrian mandate (Cilicia), and the Zone of the Straits was declared an international area, where only Allied troops could be stationed. Finally, the Allies rewarded the Greeks richly for their small participation in World War I: they got all of Turkey-in-Europe except Constantinople, and an unspecified amount of land around Smyrna. To nobody's surprise, the sultan signed it and Kemal rejected it. Kemal did not miss the loss of the Arab lands, but under no circumstances would he give anything to the Greeks, traditional enemies of the Turks. However, the Greeks had been expecting that and had already transferred the bulk of their army to Smyrna. At the beginning of 1921 they launched an offensive, pushing eastward almost effortlessly.

A Greek propaganda poster shows how much of Turkey the Greeks expected to get after World War I. Had these boundaries gone into effect, Greece would have gained all the land that belonged to the Byzantine Empire in the late thirteenth century, before the Ottoman Empire got started (see Chapter 12). The Greek prime minister, Eleutherios Venizelos, is in the top left corner.

Kemal now found himself facing enemies in every direction, while he was hard pressed just to clothe his troops (he required every home to supply a kit of underwear, socks and shoes). He survived because of successful diplomacy on the eastern and southern fronts. Italy and the new Soviet Union gave him aid, and while he had to give most of Transcaucasia to the Soviets, he did get to keep the Kars region of Armenia. That gave him a free hand to eliminate the Armenian separatists--there would be no Armenian state while he had any say in the matter! To the south, the French were concerned about their Syrian problem and purchased Kemal's neutrality by handing over Cilicia to him.

Meanwhile in the west, the Greeks were coming closer, advancing two-thirds of the way to Angora before they were stopped. But stopped they were, on the banks of the Sakarya river. There, late in the summer of 1921, Greeks and Turks battled along a sixty-mile front for twenty-two days and nights. Kemal's tactic was to divide his army into individual units, each operating independently of the others, so that there was no Turkish line of defense to break. "There is no linear defense," he explained. "There is a surface defense, and the surface is the entire territory of the nation." Fighting for their lives and country, the Turks wore down the Greeks, and by the end of the year the scales had tipped Kemal's way.

The following summer, Kemal ordered a counteroffensive that broke the Greek army quickly and completely. Perhaps half of it managed to get back to Smyrna, but the Turks closed in fast and the Greek dream of reviving the Byzantine Empire ended in a hurried and humiliating evacuation. Smyrna was captured violently on September 9, and over half the city, including all of the Greek and Armenian quarters, was burned down. The death toll, in military and civilian casualties, may have been as high as 100,000. After the war ended, 1.5 million Greeks were left in the Smyrna neighborhood, and a progrom was launched against them; those who did not escape to Greece were killed.

Kemal now turned his attention to the Straits, where his troops confronted a British force at Chanak, on the east shore of the Dardanelles. Faced with a Turkish army that was clearly spoiling for a fight, the Allies decided to get out. The Greeks had decided by this time that they wouldn't even try to hold onto eastern Thrace, so the part of the Treaty of Sevres that dealt with Turkey's western frontier became a dead letter; the Turks simply re-occupied everything they had held in 1914.

Mustafa Kemal's last opponent on the road to total victory was the sultan. He bullied and persuaded his government to abolish the sultanate, and on November 17, 1922, the sixty-one-year-old Mohammed VI went into exile on a British ship. His cousin stayed behind to take the post of caliph (now a powerless job), and he died in Italy four years later, after making an unsuccessful bid to replace Hussein as king of the Hejaz. Thus, 700 years of Ottoman history ended.

The Republic of Turkey

The new Turkey had no pretensions about becoming an empire; it accepted that its position would be that of a middle-rate power. There were many of these in eastern Europe now (Poland, Finland, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia), and Kemal told the Allies that just like the peoples of those other states, the Turks had been oppressed by a tyrannical monarchy. Negotiations went on for eight months, and produced the Treaty of Lausanne (July 1923). In this accord the Allies recognized the new Turkish frontiers, canceled the capitulations and debts of the Ottoman Empire, and arranged for the exchange of Turkish and Greek minorities caught on the wrong side of the border. The Turkish negotiator was a five-foot four-inch hero of the Greco-Turkish war named Ismet Pasha (later known as Ismet Inönü); slightly deaf, he used this disability to his advantage by claiming not to hear any proposal he did not like. Nevertheless, both he and the Western diplomats knew that the Turks were ready to fight again if they did not get the terms they demanded.

Mustafa Kemal spent the rest of his life transforming Turkey into a modern, western nation. Few leaders have ever shaped a nation as quickly and permanently as he did. On October 29, 1923, he declared Turkey a republic, with himself as its first president. Five months later he began his program of secularization, by abolishing the caliphate. Within a month Moslem religious colleges and law courts followed the caliph into oblivion. Thus, Turkey became the first Moslem country to practice Western-style separation of church and state.

In 1925 a treaty with Britain gave the oil-rich vilayet of Mosul to Iraq. The same year saw a Kurdish rebellion in the part of Turkey nearest to Iraq, led by Seyh Said, hereditary chief of the Naksbendi dervishes. The Kurds had been loyal subjects of the Turkish sultan, who was also "Commander of the Faithful," but they wanted nothing to do with a secular Turkey. Martial law was proclaimed in thirteen provinces, and the legal definition of treason was extended to include "the use of religion as a political instrument." Within three months the revolt had been stamped out, and Kurdish hopes for an independent Kurdistan were dashed, as they would be in Iraq and Iran later. A side effect of this was that all Sufi lodges and tombs of the saints were closed for the remainder of Kemal's lifetime.

Modernization was Kemal's only faith, and by that he meant the adoption of anything the West used. He introduced Western calendars and clocks, adopted the metric system, and encouraged orchestras to play Western music. Traditional Moslem practices such as polygamy and begging were outlawed, womens' education was promoted, and voting rights were extended to all citizens. He banned the fez, in favor of brimmed European hats, and encouraged women to take off the veil.

Mustafa Kemal's favorite project was the overhauling of the Turkish language. He helped prepare a twenty-nine-letter Latin alphabet to replace the Arabic script used previously, and spent much of his time touring the countryside with a blackboard, teaching peasants how to use the new alphabet. Words of Arabic or Persian origin were purged from the Turkish language, and replaced with ancient Turkish equivalents, though he had to stick with words of Western origin for modern inventions like the otomobil and fotograf. Despite the confusion this produced, literacy increased dramatically in the 1920s and 30s.

The language revision was just one part of a program to give the Turks a new form of nationalism. History books were rewritten to belittle the role of the Ottomans; instead they stressed the achievements of the Turkish people as a whole. The Sumerians and Hittites, and every ethnic group that had once lived on the Central Asian steppes, were all claimed as Turks. Since "adam" is the Turkish word for man, some even claimed that Adam and Eve were Turks and therefore all mankind is of Turkish ancestry. Of course such ideas were absurd, but they served a useful purpose in restoring Turkish racial identity and pride.

Even Turkish names were changed. All place names from other languages were dropped, and thus Angora became Ankara, Smyrna became Izmir, and Constantinople became Istanbul. In 1934 traditional titles such as Pasha or Bey were abolished, and Turks were told to pick a Western style surname, instead of calling themselves after a birthplace or profession. For example, Kemal was really a nickname meaning "excellent," because Mustafa Kemal had been an excellent math student in school. Now parliament gave him the name of Atatürk, meaning "Father of the Turks."

Kemal Atatürk--as he was always called after this--never quite got the idea of how democracy works in the West. Although his title was president, he was really a benevolent dictator, personally guiding every affair of the country and its people; his political philosophy was appropriately called "statism." The state controlled agriculture, industry, and foreign exchange; for example, farmers were given subsidies to grow profitable crops, but not those for which there was little demand. This program worked in Turkey's favor; the Turks made it through the Great Depression with only a little more hardship than they were used to already. Kemal Atatürk said that he wanted to give up some of his power, but calamities like the Depression made it too dangerous to do so. He did allow opposition parties, though, if they only opposed him personally and not the state he was creating.

Kemal Atatürk lived in a 19th-century Ottoman palace, and died there on November 10, 1938. He was mourned extravagantly, but genuinely, by his country. "The Turkish homeland has lost its great creator," lamented the official announcement, "the Turkish nation a mighty chief, and humanity a great son." The announcement could have added that the Middle East had lost its greatest statesman as well. Kemal Atatürk is remembered so fondly by his people that his portrait still can be found in every Turkish household today.

The Anglo-Arab Monarchies

The British, like the French, had trouble when they assumed control of the territories mandated to them. There was a major uprising among the tribes of the central Euphrates in the summer of 1920, which cost 2,000 casualties and 40 million pounds (more than three times the total subsidy of the Arab Revolt) to suppress. After it was over the British decided to reward their principal Arab client, Faisal, by making him king over Iraq. They carefully arranged his triumphal arrival. First they held meetings to persuade tribal leaders. Then a political rival, Sayid Talib, was whisked off in an armored car to a prolonged stay in Sri Lanka. Finally a plebiscite was held in which Faisal won with a 96.8% majority. He was crowned on April 23, 1921.

Faisal got off to a good start because several hundred of his officers settled in Iraq with him, giving him a base of local support. In 1924 a constitution was drawn up that provided for a British-style limited monarchy. In practice, though, the Iraqi government centered on a few key figures who rotated portfolios in ever-changing cabinets, while British advisors labored in the background to keep Iraq stable and pro-British. Each cabinet won support by promising to get rid of British influence, a promise it knew it could not keep, and then it resigned to give another group of politicians an opportunity to fail. These appeals to Iraqi nationalism served a useful purpose, though, by submerging the potential explosive divisions between the country's ethnic groups (Sunni vs. Shiite Moslems, Kurds & Assyrians vs. Arabs, tribesmen vs. townspeople, etc.). The most important Iraqi politician was an ex-Turkish army veteran named Nuri Said, who served either as prime minister or in some other important post during this time; while he was in charge, Iraq would be the friendliest Arab state to the West.

A gusher was struck at Kirkuk in 1927, making Iraq the second largest oil producer (after Persia) in the Middle East. A pipeline was built to the Mediterranean, and Iraq did not have to worry about revenue after that. Then a treaty with Britain was drawn up in 1930; it gave Iraq a kind of dependent independence, where Britain maintained its favored economic position, provided for "consultations" in foreign affairs, and kept air bases and troops on Iraqi soil (to protect the oil, of course). Two years later (1932) the mandate was terminated and Iraq became an independent member of the League of Nations.

Faisal died in 1933 and was succeeded by his son Ghazi. Handsome and popular, but irresponsible, Ghazi was happy to let factions of army officers and ministers compete for power while he pursued his hobbies of fast horses, airplanes, and sports cars. In 1939 he was killed in an auto accident; his brother-in-law, the Emir Abdul Ilah, became regent for the king's infant son, Faisal II.

One other Hashemite had ambitions. In November 1920 Abdullah appeared at Ma'an, in what is now southern Jordan, with a motley group of followers and announced his intention of marching on Damascus to avenge his brother's expulsion. Winston Churchill and T. E. Lawrence, who were talking with Palestinian Arabs in Jerusalem at the time, summoned Abdullah to meet with them. Like a good Oriental salesman Abdullah began by naming impossible prices, like joining Iraq with Palestine and making him king over both. Instead the British offered to give him the land on the east bank of the Jordan river (76% of the Palestine mandate), along with an annual British subsidy and a promise to make the French give him Syria later. Abdullah haggled, then finally accepted the British proposal. He knew there was no real chance of getting Syria from the French, but a secure emirate was worth several hypothetical kingdoms.(2)

Abdullah's kingdom, now called Transjordan, was an unappealing peace of real estate, all desert except within a few miles of the Jordan river and no natural resources. In the past great nations had passed it by without caring who owned it. That is why the Hashemites have survived there to this day--nobody else wants the land. More intelligent, humorous, and stronger-willed than his brother Faisal, Abdullah never let his poor-relation status bother him; in fact, he showed some contempt for the pomp of the court in Baghdad. Abdullah and his successors have supported themselves with financial subsidies from friendly outside powers, first the British, and later oil-rich states like Saudi Arabia.

Abdullah's biggest asset was his army, known as the Arab Legion. It was trained by British officers and commanded by General Sir John Bagot Glubb, who gave himself the peculiar title of Glubb Pasha and continued the Lawrence of Arabia tradition. Because this was the strongest military force in the Arab world, Abdullah hoped that he could someday use it to add some richer lands to his own. Instead this had fatal consequences for him and the stability of his kingdom.

La Syrie et Le Liban

The French did not have the same attitude as the British toward their mandated territories. Not only were they in no hurry to end the mandate, but they tried to squeeze out a profit while they held the area. They enlarged Lebanon so that it included not only Beirut and Mt. Lebanon but several predominantly Moslem areas, like the Bekaa valley, Tyre and Sidon. The idea behind this was to create as large an area as possible for Lebanon's Christian Arabs to rule, since they were more likely than Moslems to be friendly to France. Sure enough, a 1932 census announced that Lebanon had a slight Christian majority. A constitution was drawn up in Paris and imposed on the Lebanese with the assumption that the situation would stay that way; all seats in the parliament and cabinet would be filled by people of the appropriate religious persuasion. The president, for example, had to be a Maronite Catholic, the prime minister a Sunni Moslem, and the speaker of parliament a Shiite Moslem; in addition, the cabinet was required to have at least one Greek Orthodox and one Druze member. Seats in the parliament numbered a multiple of eleven, with six Christians for every five Moslems.(3)

Syria was subdivided into four provinces, each with a French governor and a staff made up of Arabs and Frenchmen. The policy behind this was "divide and rule," but the French said that they did it to be fair to two religious minorities, the Alawites and the Druze. Later, elected councils and a constitution made it look like Syria was moving to independence, but the French high commissioner and the French army were always there to guard the interests of Paris. Just as distressing to Arab nationalists was the French insistence on their "civilizing mission." French was taught as a second language in all schools, and textbooks were written to encourage French ideas and culture.

French rule did have its positive side. France expanded communications, built schools, and used public health programs to eliminate the scourge of disease; the general standard of living improved. To Arab nationalists, however, this did not compensate for the loss of freedom and self-determination. Fortunately for them, France ruled Syria and Lebanon for only one generation, and today the imprint of French culture on the Middle East is minimal (contrast this with other former French colonies like North Africa).

A negotiated treaty calling for Syrian independence was completed in September 1936, and a similar document was drawn up for Lebanon in November. The Syrian and Lebanese parliaments ratified both treaties, but they were voted down by the French legislature and thus never went into effect. There were both economic and political reasons for this. First, there was the possibility that oil might be discovered in Syria, since it was next door to Iraq. Another factor was that Syrian and Lebanese independence would affect the Arabs living in French North Africa, perhaps inspiring them to call for independence too. Finally, the growing threat of Nazi Germany made the French feel that they could not let go of anything anywhere.

The prospect of war with Germany also led France to buy peace with Turkey, by readjusting Syria's northern border. For years Turkey had claimed the sanjak or district of Alexandretta, which had a mixed population of Turks, Arabs, and Armenians. In June 1939 the area was formally handed over; Turkey renamed it Hatay, in memory of ancient Hatti (see chapter 2), and classical Antioch became modern Antakya. Naturally Syrian nationalists opposed the loss of their country's northernmost ports, and have never accepted this bit of diplomacy. Today maps in Syrian schools still show Antioch and Alexandretta as part of the Syrian Arab Republic.

Before we move on, a brief mention of the Syrian political parties forming at this time will help to explain some events covered in the next chapter. The most important of these was the Baath, or Renaissance Party, founded in 1944 by a Christian schoolteacher in Damascus, Michel Aflaq. As the name suggests, Baath members felt that a long dark age was ending for the Arabs. Aflaq stated that the party's main goals were "freedom, unity, and socialism." By freedom he meant political, cultural, and religious liberty, and an end to colonial rule. His socialism was a liberal program involving land redistribution, nationalization of utilities, regulation of wages and working conditions, old age insurance, free medical care, and free secondary schooling, rather than a Marxist plan for the complete restructuring of humanity and society. Aflaq's partner in organizing the party, another schoolteacher named Salah Bitar, served as Syria's prime minister more than once after independence. The Baath party has played a pivotal role in modern Syrian and Iraqi politics, ruling both countries since 1963.

Another party was more powerful at first, but less successful in the end: the Parti Populaire Syrien (PPS). This was the brainchild of Antoun Saadeh, another Syrian Christian. More overtly fascist than the Baath, the PPS saw strength, discipline, unity and obedience to a single leader as the way to achieve its goals. A determined humanist, Saadeh called for a complete separation between the state and religious institutions; this gave him considerable support among ethnic minorities like the Christians, Druze, and Kurds. Instead of Arab unity, he called for a Greater Syrian nation that controlled the whole Levant. To him, the Syrian people were not just Arabs but everyone who has lived in Syria since the beginning of history: an ethnic fusion of "Canaanites, Akkadians, Chaldeans, Assyrians, Aramaeans, Hittites, and Mitannis." He said that when the Arabs arrived in the seventh century the Syrian national character had already been formed.

After World War II Antoun Saadeh attempted to take on the governments of independent Syria and Lebanon, and was executed by the Lebanese for launching an unsuccessful coup in 1949. His successor ran head-on into the rising tide of pan-Arab nationalism, which rejected the Syrian separation of the PPS. The party tried to come to terms with this trend too late, and disappeared after a second Lebanese coup attempt in 1961.

Ibn Saud

Hussein was upset at the way the Allies treated his sons, but he could not even hold onto the kingdom assigned to him. After World War I ended relations between the Hashemites and the Saudis deteriorated, because both claimed leadership over Islam and the Arabian peninsula. In 1919 Abdul-Aziz ibn Saud resumed his campaign to bring Arabia under Wahhabi rule; he defeated Hussein in a battle that year, and only British intervention prevented a full-scale war (Britain was still subsidizing both monarchies). In 1921 ibn Saud annexed Asir, and eliminated the last of the Rashidi emirs, his traditional family foe. In 1924 Hussein claimed the now-vacant office of caliph, and ibn Saud declared war; before the year was over the Saudis overran all of the Hejaz, including the holy cities. Hussein abdicated in favor of his eldest son, Ali, and retired to a bitter exile in Cyprus. Yet for Ali the situation was hopeless; one year later he abandoned all claims to the land and crown of his father. Ibn Saud waited until the major powers recognized his new status, and in 1932 he proclaimed the four territories under his control (al-Hasa, Asir, the Hejaz and Nejd) the united Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. There was still one other independent Arabian leader to deal with, the Imam Yahya of Yemen, and their dispute over Asir led to a two-month border war in 1934. Saudi troops led by ibn Saud's son, Prince Faisal, quickly routed the imam's forces, but in the peace agreement the Saudis took almost nothing, and those moderate terms made ibn Saud and the imam friends for life.

To prevent a future Arabian war, the British demanded that the Saudis and Hashemites agree on permanent national boundaries. Britain had already taken care of the Saudi-Transjordan frontier when it created Abdullah's kingdom, but a defined frontier wasn't a priority for either ibn Saud or Iraq's Faisal. This issue here was that the area between them was populated by Bedouins, who resented others telling them where they could and could not go. This meant that it would be almost impossible to draw a boundary that didn't cut off some tribe's access to a grazing ground or oasis. When the British got tired of waiting for the borders, they convinced all parties to create two neutral zones instead, one between Saudi Arabia and Iraq, the other between Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Nomads could still travel freely through each zone, but no government could build fortifications or station troops in or near the zones. This worked until oil was discovered under the Saudi-Kuwait zone, and then both countries agreed in 1969 to divide it up, regardless of what the nomads might think. Saudi Arabia and Iraq agreed to divide the other zone in 1981, after the Iranian revolution and the Iran-Iraq War persuaded them to do something to stabilize the border and improve Saudi-Iraqi relations.

Ibn Saud's biggest problem was money; his kingdom was not only backward but desperately poor. In the early 1920s his total revenue from all sources was only £150,000, plus an annual British subsidy of £60,000. Unlike the Hashemites in Iraq and Transjordan, he had Wahhabi puritanism opposing every attempt to modernize his country. Everything Western, from the telephone to the automobile, faced a stiff challenge when introduced (the question of whether to legalize the bicycle was a subject of serious discussion for the Ulema). The king, in the manner of a typical Arab sheikh, micromanaged everyday life, personally meeting with every citizen of his country who might have a problem, no matter how lowly that subject might be.(4) For a long time he was a successful leader, using a combination of commanding presence, personal charm, and a sense of humor, but by the 1930s his advancing age forced him to relax control. Since there were not enough trained Saudis to run the government, he ended up hiring other Arabs, mainly Egyptians, Syrians, and Lebanese.

The king had two ways to increase his meager revenues: raise the tax on pilgrims traveling to Mecca, or open his country to Western exploitation. Most Moslems disliked the former, and he and his followers had grave doubts about the latter. When the Great Depression sharply reduced the number of pilgrims making the hajj, the money shortage became really bad, and the king overcame his fears about doing business with Westerners. In 1932 he sent a delegation of diplomats to London, led by Prince Faisal, to ask for a loan of £500,000 in gold. As part of the terms for repayment of the loan, the Saudis would allow the British to drill for oil in their country. However, the senior civil servant they met in the Foreign Office, Sir Lancelot Oliphant, thought it was a risky business venture to drill in the Arabian peninsula, when the only evidence for oil was the fact that it had been discovered in nearby Persia and Iraq. Moreover, money was tight in Britain during the Depression, too, so he turned down the Saudi proposal. Ibn Saud next turned to the United States, found the Americans more receptive, and granted an oil concession to Standard Oil of California. Five years after that the big oil strike was made (1938). Three other oil companies joined with Standard Oil of California to create the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco) in 1944. Although full development of this resource would have to wait until after World War II, it soon became apparent that the Saudis had more oil under their land than the richest Texas oil baron.

A parallel development took place in the Persian Gulf sheikhdoms. Oil was discovered on Bahrein in 1932 (just two weeks after the British Foreign Office sent away the Saudis empty-handed!) and in Kuwait in 1938. Both of those countries had small populations, and when the oil money was divided among them it made for an extremely high per capita income. Both countries devoted a large share of their newfound wealth to education and other social services. The modern oil-rich sheikhdom, a land of Cadillacs and camels, where the rulers had more money than they knew what to do with, now came into existence.

Reza Shah Pahlavi

Persia, like Turkey, hit bottom during and immediately after World War I. The authority of the last Qajar monarch, Ahmad Shah, was virtually nonexistent outside Tehran. Persia as a whole was so weak that its neutrality during the war did not matter a bit to the major powers. Turkish and Russian soldiers marched through the northwestern part of the country, each trying to open a second front against the other. German agents gained control over several cities (Shushtar, Isfahan, Yazd, Shiraz and Kerman), forcing the British to divert for the defense of the oilfields troops that might have prevented the 1916 defeat in Mesopotamia. The last year of the war saw British troops occupy Kermanshah, Resht and Tabriz. The usual wartime economic dislocations generated a devastating inflation that multiplied the price of food and other goods some ten times.

After the war Britain coerced and bribed the regime into accepting a treaty that would have reduced the country to a British-run protectorate. The Majlis, however, was beginning to feel the stirs of nationalism and would not consider ratification of this document. To the north, the Bolshevik revolution led to a dramatic change in Russo-Persian relations. As part of their effort to start a worldwide revolution against capitalism, Russia's new leaders announced they would abandon the concessions that the tsars had obtained from other nations. They renounced extraterritorial rights, canceled loans, and abolished trade agreements, with one notable exception: the caviar-producing Caspian Sea fisheries. Apparently even communism could not get rid of the Russian craving for this luxury.

Into Persia's postwar chaos stepped Reza Khan, an illiterate army officer with a reputation for valor and leadership. As commander of the Persian Cossack Brigade, he swept down on Tehran in 1921 and forced the Shah to accept a new cabinet, with himself as war minister and a fiery journalist, Sayyid Zia ud-Din Tabataba'i, as prime minister. The new prime minister immediately tried to confiscate the landed estates and do away with corruption, but his reforms were far too radical to accept at this early date. After all, the leading nationalists were also landlords and bureaucrats, whose principal goal was to eject foreign influence, not undercut their own positions. Discredited by his extremism, the prime minister was forced to resign before the year was over, and Reza Khan took his job. In 1925, Ahmad Shah, who had fled to Europe, was officially deposed, and Reza Khan was enthroned in his place. He changed his name to Reza Shah Pahlavi; "Pahlavi" is the modern Farsi name for the language of the Parthians (see Chapters 6 & 7). By doing this the new shah was letting people know that true Persians now ruled Persia, not half-Turks like the deposed Qajars.

Inspired by Kemal Ataturk, Reza Shah began an ambitious program to modernize Persia. First he eliminated every military force that was not directly dependent on his bounty. Sparing no expense on his own army, he used it to bring every dissident unit to heel, including hard-to-control nomadic tribes like the Bakhtiari who could previously do what they pleased. Persia was now more peaceful and united than it had been in 300 years.

On the economic scene another American expert, Dr. Arthur C. Millspaugh, was hired to put the country's financial house in order. During his five-year contract (1922-7) he went a long way toward completing that task; corruption was reduced, landlords and other aristocrats were forced to pay their fair share of taxes, and the budget was balanced. Roads and railroads received major attention, and many factories were built, although there weren't enough trained technicians and managers to run them efficiently.

Despite all this, the Shah was far less successful than Ataturk had been. First he knew little about the West, and the Persians were more backward and conservative than the Turks. Reza Shah was an energetic, straight-laced hard worker, who never seemed to enjoy being around his subjects the way Ataturk did. Indeed, he chose to run everything himself, rather than delegate responsibility to others; he probably could have delegated little anyway, because of the lack of trained talent. The Majlis became a rubber stamp for his decisions, rather than a true legislative body, and rigorous censorship suppressed any expression of opposition. Eventually the heavy workload took its toll on him; he became more introverted and despotic, and lost the friendly personality that had made him popular originally.

In 1935 he changed the official name of Persia to Iran, effectively telling the rest of the world to call his land by its Farsi name. In 1939 he married his twenty-year-old son, Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi, to Princess Fawzia, the sister of King Farouk of Egypt. The marriage was a failure, because it produced no son. The future Shah had to divorce and remarry twice; his third wife finally gave him an heir in 1960.

The main obstacle to reform was the Shiite hierarchy. Again following Kemal Ataturk's example, Reza Shah tried to secularize the state. The vast estates, schools, hospitals, and other properties of the clergy were confiscated, along with the 200,000 peasants who worked on that land. As compensation he gave the mullahs stipends, in the hope that they would now look to the government for their livelihood. Public performances by dervishes and penitential parades mourning the deaths of the Shiite martyrs were banned, and so were polygamy and the wearing of the veil by women. Finally, Islamic law was replaced by a secular law code patterned after the French model. The effectiveness of these reforms varied greatly, from almost nothing in remote areas to absolute obedience wherever the Shah could apply his authority. Still, Reza Shah always considered himself a faithful Moslem, and never crushed the clergy completely, the way he did his political and military foes. That oversight would come home to roost during the reign of his son.

Late in the 1930s, the Shah openly showed admiration for Nazi Germany and its dictator, Adolf Hitler. When Hitler offered generous trade agreements, he accepted, without a thought for what the rest of the world might think. Thousands of Germans of every description came to Iran; Nazi scholars flattered the Shah by telling him that since Iran's name comes from the same root word as "Aryan," the Iranians must be Aryans like the Germans. By the beginning of World War II, 45% of Iran's trade was with Germany.

Nationalism in Egypt

Early in the twentieth century Egyptian nationalism gained a new voice in a craggy middle-aged lawyer with a gift for oratory, Saad Zaghloul. The British resident, Lord Kitchener (the same Kitchener who had conquered the Sudan), could not get along with Zaghloul, but in 1913 he found this troublesome man in charge of the legislature created by the British in the hope of staving off nationalist demands. Egypt was about to revolt when World War I intervened.

Officially Egypt was neutral during the war, but British censorship and martial law kept the Egyptians in line, while inflation and shortages caused severe hardship for the people. The wartime disregard for Egyptian sensibilities fueled the fires of nationalism in a way the British government failed to appreciate. When the war ended, Saad Zaghloul requested permission to go to London to present his case for independence. The British refused, and Zaghloul's followers organized to form a political party known as the Wafd (delegation). The arrest and deportation of Zaghloul and three other leaders to Malta sparked violence and rebellion all over the land. General Allenby, the wartime hero, was sent in to restore order, but once he did he recalled Zaghloul from exile and let negotiations for independence begin.

Britain had three primary interests in Egypt: (1.) the Suez Canal, (2.) the economic concessions or "capitulations" it had enjoyed since Ottoman times, and (3.) rule over the Sudan. Whatever form independence took, the British were determined to keep all three. Zaghloul opposed this, of course, but since they could not agree on these matters, both sides agreed to go ahead with independence now and deal with the thorny questions later. Egypt was declared an independent nation in 1922; the last surviving son of the Khedive Ismail was crowned as King Fuad I (1917-36). The result was similar to the dominion status Britain had granted to Canada and Australia previously; not only were British interests maintained, but Britain retained the right to intervene in Egypt's affairs in case of war. The situation as it stood was unacceptable to any Egyptian nationalist, and Egypt's struggle for full independence would continue for another generation.

Zaghloul died in 1927, long before the fruits of his labor were won. Whenever free elections were held, the Wafd won an overwhelming majority of seats in the legislature. However, the king disliked the idea of limited monarchy--in 1930 he replaced the constitution with a new one that increased the powers of the king. The following year saw new elections, which were won by right-wing authoritarians and declared fraudulent by the Wafd. This government was not at all popular, and in 1934 the Wafdists returned to power. One of their first acts was to bring back the constitution of 1923.

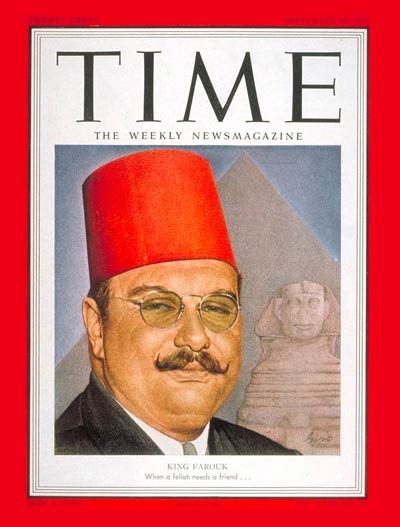

In 1936 Fuad was succeeded by his sixteen-year-old son Farouk. He began his reign with a public radio address, the first time in modern history that an Egyptian leader had spoken directly to his people. Whereas Fuad had only known Turkish, Farouk could speak Arabic, and he was hailed as a hero who would bring a new day for his countrymen. Instead he squandered millions; while most of his people lived dangerously close to starvation, the king bought yachts and jewels, and collected rare coins and stamps. Although he avoided drinking, in respect to the teachings of Islam, he also chased women, and grew monstrously fat. He gambled compulsively, until a courtier remarked, "A man who can lose $120,000 in a night can lose anything." Like Reza Shah Pahlavi, he liked Nazi Germany, which got him in trouble with the British after World War II began.

Before Farouk became an object of ridicule and scorn, he won a new agreement on Britain's relations with Egypt. In 1936 Britain agreed to withdraw its forces from Egypt proper, limiting its troops to 10,000 soldiers in the canal zone. Both sides agreed to a twenty-year alliance, and Britain promised to phase out its grip on the Egyptian economy.

At this point it seemed that the three political factions in Egypt--King Farouk, the Wafd, and the British--had finally reached terms that everybody could live with. Nevertheless, many Egyptians still wanted complete independence, and groups of those who would not compromise now came out into the open. The most notorious of these groups was the Moslem Brotherhood, founded in the 1920s by a schoolteacher who felt that every aspect of Egyptian society should be based on the Koran and Islamic traditions. Soon the Brotherhood was giving its members paramilitary training, and sending them on bombing or assassination missions against Western targets.

Meanwhile, student demonstrations against Farouk and the British increased. One of these students was a tall and moody teenager named Gamal Abdel Nasser. In 1935, after getting wounded by police bullets in one demonstration, he considered joining the Brotherhood, but found it wanting; twentieth-century Egypt could not solve its problems by becoming an eighth-century caliphate. In 1937, at the age of nineteen, he entered the Military Academy, after concluding that the army was the only faction with the discipline and organization needed to reform Egyptian society. There he met several like-minded young officers (Anwar Sadat was among them), and together they formed the clandestine Free Officers' movement.

The Rebuilding of Zion

Western Palestine was the most troublesome of all the Middle Eastern mandates. We already stated the reason for this: separate arms of the British government, not knowing what each other was doing, had promised the land to both the Jews and the Arabs. Still, in 1918 a solution appeared possible. The population, despite Jewish immigration, was overwhelmingly Arab, and it was Britain's duty as the mandatory power to prepare the locals for self-government as quickly as possible. Of course the Zionists would try to create a Jewish majority in the land before this happened, but it did not look like they could do it, and once the British were gone it would be up to the Arabs to decide what role the Jews would have in their state.

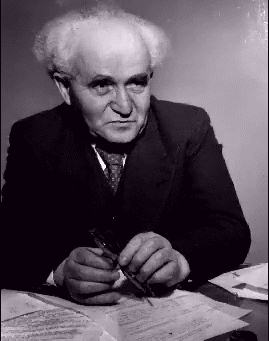

The Jews in the land suffered badly during World War I. Jemal Pasha distrusted them because many had immigrated from the Allied nations, especially Russia; thus he was inclined to give them the same sort of treatment the Turks had dished out on the Armenians and Syrian Arabs. Zionist leaders were arrested and deported; among the latter was a farmer named David Ben-Gurion, who would one day become Israel's first prime minister. Other Zionists were tortured, hanged, or shot. Thousands of ordinary Jews gave up their pioneering dream and moved away. By the end of the war, Palestine's Jewish population had nearly been cut in half, to about 50,000.

Recovery from this setback came quickly. By 1920 about 10,000 more Jewish immigrants had arrived, again mostly from Russia. Another 8,000 came in 1921. In response the Arabs urged the British to give them representative government at once, so they could veto all future Jewish immigration. Britain rejected this demand, but after the riots of 1920-21 the British High Commissioner, Sir Herbert Samuel (himself a Jew), ordered an immediate suspension on Jewish immigration, and some Jews who had just arrived in port were refused permission to land. Immigration resumed after tensions cooled (40,000 Jews came between 1922 and 1925), but Britain insisted that it should never exceed "the economic capacity of Palestine to absorb new immigrants," a phrase which pleased the Arabs and alarmed the Jews.

1920 was an important year for the following three reasons:

1. The beginning of the Arab-Israeli conflict. On March 1, 1920, Arabs attacked Tel Hai, a Jewish agricultural settlement near modern Metulla. Eight Jews were killed, including Josef Trumpeldor, a war hero and founder of Hehalutz, a Russian movement that encouraged immigration to the land. Several other Jewish communities were attacked in March and April, and in May 1921.

2. The Jewish response. The Zionists chose not to wait until Britain restored order. In June 1920 they organized their own paramilitary force, the Haganah ("defense"), to protect Jewish settlements from further Arab attacks. This was not entirely legal, but the British chose to look the other way because the Haganah did not attack either Arabs or the British authorities. After independence those men who gained experience in the Haganah would form the core of today's Israel Defense Force (IDF).

3. A new organization. In December 1920 four Jewish groups met in Haifa to merge and form the Histadrut, the labor union of modern Israel. Its purpose was to encourage immigration, agricultural settlement, the growth of industry, and social welfare projects. From this point on the Histadrut would be the main organization promoting economic development of the land. The union's political wing, the Mapai or Labor Party, would also play an important role under its founder, David Ben-Gurion (1886-1973); it would run the Israeli government for a generation after independence.

The next few years saw a dramatic transformation of the land. As Jews bought overpriced tracts of wasteland from the previous owners, they drained swamps, irrigated deserts, and built farming communities.(5) Most of the farms were communes known as kibbutzim, and were run along socialist lines, with all property owned in common. Other farms, called moshav-ovdim, allowed individual ownership of land and homes, but resembled the kibbutz in that the members pooled their resources to buy expensive machinery like tractors and incubators. They also planted about five million trees, turning deserts into forests, and today Jews still commemorate important personal events like weddings by planting a tree.

As the Jews transformed the land, so the land transformed them. Hebrew was revived and made into a modern language, thanks largely to a fanatical scholar, Eliezer Ben Yehudah, who insisted on speaking and writing only in Hebrew. Whereas the Jews had previously gone into white-collar professions (rabbis, doctors, bankers and lawyers, etc. ), now they learned to be farmers as well. And since they would have to fight to defend their gains, they changed from a passive people to a nation of fighters, the physical and mental opposite of the "ghetto Jew" stereotype. For that reason, those born in the land came to call themselves sabras, meaning cactus: tough and prickly on the outside, but sweet on the inside.

One Zionist faction chose not to restrain itself when it came to defending the Jews. Vladimir "Zeev" Jabotinsky (1880-1940), a famous Zionist orator and journalist, joined the British army during World War I and formed three battalions known as the Jewish Legion, or "the Judaeans." The Legion fought at Gallipoli, and alongside General Allenby's troops in the final months of the war. After the war he became the main spokesman for those who favored the creation of a Jewish national army. In 1935 he founded a political party known as the New Zionists (later the Herut party); two years later this was followed with a paramilitary force, the Irgun Zvai Leumi (National Military Organization). His goals were easily understood: force the British to go home, defeat the Arabs before the Arabs attacked them, bring in one million Jewish settlers within a year, and establish without delay a Jewish state on both sides of the Jordan.(6) Moderates and non-Zionists denounced the Irgun as a terrorist, fascist organization. Irgun members strongly denied this charge, and said that they must do whatever they can to save the Jewish people from the undying monster of anti-Semitism.

The Zionist equivalent of Uncle Sam was Bat Zion, the "Daughter of Zion." She even had her own version of Uncle Sam's famous "I want you" poster; written in Yiddish, it says "Your Old [and] New Land must have you! Join the Jewish regiment."