| The Xenophile Historian |

A History of Russia

Chapter 5: SOVIET RUSSIA, PART I

1917 to 1928

This chapter is divided into three parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| The Nightmare of Stalinism Begins | |

| Prelude to World War II | |

| The Winter War | |

| "The Great Patriotic War" | |

Part III

| The Cold War Begins | |

| Recompression at Home | |

| The Khrushchev Years | |

| Brezhnev Takes Charge | |

| Foreign Policy: The Brezhnev Doctrine & Détente | |

| Gerontocracy Triumphant | |

| Gorbachev's Experiment | |

| The Union of Fewer and Fewer Republics |

The February Revolution and the Provisional Government

World War I brought nothing but misery to the Russian people. By early 1917, the number of Russian casualties (killed, wounded, prisoners of war, and missing) had reached 7 million, nearly half of the entire force mobilized in 1914. By removing 15 million men from the farms and factories, and sending them to the front lines, Russia's developing economy was stretched to the breaking point. As more and more factories and railroad rolling stock were diverted to support the war effort, exports dropped to half of their 1913 level, and consumer goods disappeared from store shelves, resulting in inflation all around.

The Allied countries sensed this and tried to keep Russia's economy from collapsing with massive amounts of foreign aid, but Turkey blocked access to the Black Sea and Germany kept Allied shipping out of the Baltic. The aid that did get in had to follow a long roundabout path via Siberia (Vladivostok) or the Arctic (Murmansk).

Despite the inflation, the government paid the farmers the same price for their harvests as before. Realizing that the money they were getting was worthless, the farmers stopping selling food, and the cities found themselves facing starvation. In February 1917, 40,000 workers from the Petrograd Putilov factory went on strike, demanding food and a 50% wage increase. The management retaliated by firing the workers; in a wave of sympathy, 200,000 other Petrograd factory workers left their jobs. As the strikes and demonstrations increased, the soldiers were ordered to shoot the protesters; they did so at first, but then they joined the rebels and shot the officers giving the orders instead.

It was 1905 all over again, with the workers and soldiers electing Soviets as rebel governments in the cities. Meanwhile the tsar ordered the Fourth Duma to stop meeting until the crisis was passed. Fearing dissolution, the Duma also switched sides, becoming the "Provisional Government" of the revolution until free elections could be held. Seeing nobody left to support him, Nicholas was compelled to abdicate; on March 15 he gave up his throne at a little railroad station that was appropriately named Dno (bottom). The crown was offered to the ex-tsar's brother Michael, but knowing how unpopular the monarchy had become, he said he would only accept it if the people asked him to become tsar. They didn't, and the 304-year-old Romanov dynasty came to an end.

The leaders of the Provisional Government were inexperienced and unable to agree on important issues like land reform; they chose to procrastinate, putting as many decisions off as possible until after the elections they promised. Often they would ask the Petrograd Soviet for advice on crucial matters, feeling deep down that it was the actual spokesman for the masses. Thus for eight months there were actually two governments in Petrograd, one with formal authority but no power, the other with power but no authority.

While the country drifted helplessly from one crisis to another, one man had a practical program for the future: Lenin. Living in Switzerland, where he had been in exile for many years, Lenin had been denouncing the war ever since it began. To him World War I was an imperialist struggle, from which the workers of the world had nothing to gain. Lenin said that the masses would be oppressed whether they were ruled by German, French or British capitalists. The only path to peace and freedom, he asserted, was to overthrow those who had started the fighting. "Turn the imperialist war into a civil war" was his alternative to victory. His supporters heard his views with dismay, his enemies with scorn(1), and the Germans decided that he was just the man they needed to get Russia out of the war. The German government therefore arranged Lenin's return to Russia, giving him safe passage through Germany and neutral Sweden in a sealed train. Once he arrived in Petrograd Lenin campaigned on the slogan "Peace, land, and bread," and went to work bringing the other Bolsheviks around to his line of thinking.

Normally we think of communism as a political movement; however, with the way the Germans smuggled Lenin into Russia, they were treating communism as a secret weapon. For most of the previous three years, the Germans had been winning on their eastern front, but because of troubles elsewhere (e.g., a deadlocked struggle in Western Europe, food shortages at home), they were now desperate to end this part of the war. It shows in how they were using an ideology no European government wanted anything to do with, especially a conservative monarchy like Germany's. For that reason, today's historians have called communism the dealiest weapon unleashed during World War I. And unlike the war's other weapons such as tanks, warplanes and submarines, an idea cannot simply be put away when you're done using it. Germany's leaders must have been aware of the fact that this strategy could backfire by introducing communism to other nations besides Russia, and sure enough, there were unsuccessful communist revolutions in Central and Eastern Europe, immediately after the war (see below); in that sense it was like the influenza epidemic that swept around the world in 1918. Because there are still individuals and governments that subscribe to communism today, it is fair to say that a century after the Germans decided to send Lenin home, we are still living with the consequences of that decision.

The Provisional Government was quick to reassure the Allies by promising to continue fighting the war as if nothing happened. But the capacity to wage war was no longer there; the support system had disintegrated and the troops were "voting with their feet" (deserting) in increasing numbers. A loudly proclaimed offensive in July failed miserably, and became a rout; most of the front line troops ran away, and the Germans conquered Latvia. Some of the units in the Petrograd garrison, afraid of being sent to the front, revolted. The Bolsheviks tried to use the mutiny as an opportunity to seize power, but most of the garrison stayed loyal, and the uprising was put down after three days of bloody street fighting. Lenin had to go into hiding, shaving off his familiar beard and carrying a fake Finnish passport.

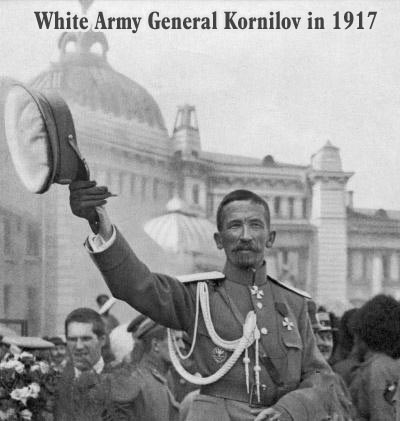

The suppression of the July Bolshevik riots in Petrograd should have given the Provisional Government a new lease on life, but another crisis followed only two days later. On July 20 the premier, Prince George Lvov, resigned because he could not get his cabinet to agree on three vital issues: whether to proclaim Russia a republic, what kind of land reform should be carried out for the peasants, and whether or not to give the Ukraine autonomy. He was succeeded by Alexander Kerensky, a lawyer from the Labor Party. Looking for someone to blame the July offensive on, Kerensky dismissed the commander-in-chief, General Brusilov, and replaced him with General Lavr G. Kornilov, a man of great courage but little understanding of politics (his chief of staff once called him "a man with a lion's heart and the brain of a sheep"). In August Kerensky secretly told Kornilov to keep his elite troops ready in case the Bolsheviks revolted again. Kornilov thought he was being told to march on Petrograd and become a military dictator, so he tried to do just that. The shocked Kerensky reversed his stand when faced with what he called a "Bonapartist threat." All charges against the Bolsheviks were dropped, their leaders were released on bail, and 40,000 rifles were given to the Bolsheviks to use in defending against Kornilov. Fortunately this coup attempt never reached the capital; propaganda from the Soviets told Kornilov's soldiers to go home and get their land. The whole army dissolved away underneath Kornilov, and Kerensky arrested him. The arms lent to the Bolsheviks were never returned.

The Bolsheviks Take Over

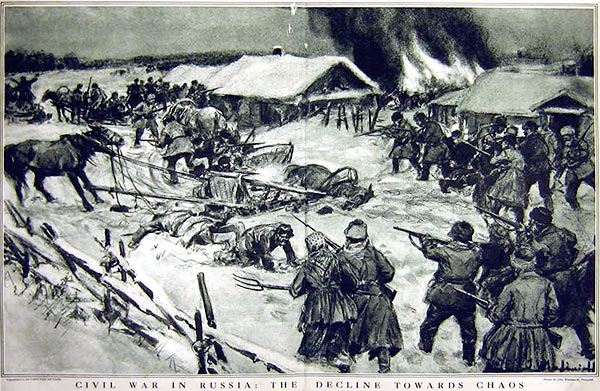

Following the Kornilov affair, law and order disintegrated completely. Army deserters returned home, often committing acts of violence and robbery along the way. The peasants grew tired of waiting for land reform and did it their own way, looting and burning the homes of landowners and often murdering them when they got the chance. A similar spree of looting went on in the shops of the cities. During this time the Bolsheviks gained control of the Petrograd and Moscow Soviets, and all of the local military units, including the Kronstadt naval base outside of Petrograd, were infiltrated, and eventually persuaded, to support the Bolshevik cause.

The Provisional Government was vaguely aware of what the Bolsheviks were doing, but it remained passive until it was too late. On November 7, 1917, the cruiser Aurora, manned by pro-Bolshevik sailors, sailed up to the Winter Palace and fired several blank shots as a warning to the government, which was still meeting inside. Meanwhile Bolshevik and pro-Bolshevik troops went through the city, occupying key points (the telephone and telegraph building, various offices, ministries, and banks) one by one. On the following day the Winter Palace itself was seized almost bloodlessly; thirteen members of the Provisional Government that stayed till the end were arrested, while the rest, including Kerensky, fled into exile. Within a week Bolshevik coups elsewhere put them in control of every major Russian city.(2)

Once he was in control, Lenin carried out his promise of land reform by ordering every large estate--whether it belonged to private individuals, the former imperial family, or the Church--seized, divided up, and distributed to the peasants. All land was declared the property of the state, and only those willing to cultivate it themselves were allowed to use it. Other reforms quickly followed, like nationalization of all banks, insurance companies, factories and means of communication; a Soviet constitution; and separation of the state from the Orthodox Church (that marked the beginning of communism's anti-religious persecutions).

But the Provisional Government had promised to hold elections on November 25, to create a legislative body called the Chamber of Deputies. Rather than risk ignoring public opinion, the Bolsheviks allowed the elections to go on as planned. The result was an embarrassing defeat; of the 703 deputies elected, 380 of them were right-wing Social Revolutionaries, while the Bolsheviks won only 168, or 24% of the available seats. As for the other parties, the left-wing SRs won 39 seats, the Mensheviks 18, the Cadets 17, and the rest went to the parties of ethnic minorities. The Chamber of Deputies met on January 18, and refused to recognize Bolshevik rule, so Lenin ordered armed sailors and members of the secret police(3) to clear the meeting hall. "The interests of the Revolution," he explained, "stand over the formal rights of the Constituent Assembly." The CHEKA spent the next few months hunting down Mensheviks, SRs, and other enemies of the Bolshevik regime. Thus, the democratically elected government lasted less than 24 hours. The Communist Party did not allow another free election until 1989.

Before 1917 was over Lenin sent Trotsky to the city of Brest-Litovsk to negotiate peace with the Central Powers. Because the Germans were in a hurry to move all their troops over to the Western Front before American soldiers arrived there, Lenin thought he could get an honorable peace with no major territorial concessions. But instead the Germans asked for the harshest terms they could get: Russia had to give Poland and Lithuania to Germany, and independence to Finland and Ukraine. Lenin had already granted independence to Finland, and he expected to see Poland and Lithuania go, since these people were not Eastern Slavs (Lenin believed national boundaries mattered less than class boundaries). But no Russian could willingly give up Ukraine, the birthplace of Russian civilization. Still, Lenin had promised peace at any price, so he ordered Trotsky to sign the dotted line.

Despite the signing of the treaty on March 3, 1918, the Central powers ended up with considerably more Russian territory than they were entitled to. The Germans did not give back Latvia, and they advanced up the Baltic coast until Estonia was theirs as well. They pushed east and occupied the Taman peninsula on the east shore of the Black Sea, and just for the fun of it they added Belarus and the Crimea to the German Empire. Turkey was promised the piece of Armenia taken in 1878, but when Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan declared independence from the Soviet Union in May, the Turks moved in and occupied everything south of the Caucasus mts. Soviet Russia's helplessness at this time was shown by Romania, which had been crushed by the Central powers in 1916, but now was able to grab Bessarabia (modern Moldova) and hold it until 1940. By August 1918, except for Petrograd itself, every piece of European territory Russia had gained in the past three centuries was lost, and one third of Russia's people fell under foreign rule. One important consequence of these losses was that in March 1918 Lenin moved the capital to Moscow, because he felt the Germans were getting too close to Petrograd. Another was the creation of the Red Army by Trotsky, to replace the old tsarist army that had all but disappeared by 1918.

For the first months following the October revolution, there was little resistance to the Bolshevik regime. Most people were too caught up in just staying alive to care much about what the Bolsheviks did. But the slamming of the door on the elected government, followed by the humiliating terms of the Brest-Litovsk treaty, and the increasing harshness of Bolshevik rule, motivated anti-Bolshevik Russians to act. The first to do so was General Kornilov, who escaped house arrest in December 1917. He went south to the Don Cossack territory and organized a "White Army" of 3,000 men to oppose the "Reds." Kornilov was killed in a skirmish shortly after that, and he was succeeded by Anton I. Denikin. During the rest of 1918 other White armies were formed wherever the Bolsheviks were not firmly in control.

The first blow struck in favor of the anti-Bolshevik cause did not come from the White Army, however, but from Czech and Slovak prisoners of war, 30,000 of which remained in Russia after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Tomas G. Masaryk, the founder of Czechoslovakia, wanted these POWs transferred to France, where he planned to use them as the army for the new Czecho-Slovak state; the Bolsheviks agreed, armed the prisoners, and let them organize into a military unit, the Czech Corps. Since going directly west was out of the question while World War I raged, the Czech Corps had to get out of Russia the long way: by taking the Trans-Siberian Railroad east to the Pacific, where Allied shipping would pick them up. The journey started in March, but having that many armed men in one place was a guaranteed source of trouble; local Red authorities often delayed them, and rumors spread suggesting that the Bolsheviks either wanted to draft the Czechs into the Red Army or turn them over to Austria and Germany. On May 14 at Chelyabinsk a fight between the Corps and some Hungarian communists ended in a Czech victory; War Commissar Trotsky declared the Czechs counter-revolutionaries and ordered them disarmed or shot. The Corps decided almost unanimously to go on to Vladivostok, even though it meant fighting at every train station along the way, and the well-disciplined force succeeded at this, reaching the Pacific on June 29. As a result of the Czech adventure, the Reds lost control of the Trans-Siberian Railroad, and with it, all of Siberia.

Not long after this, death came to the Romanovs. For sixteen months after his abdication, Tsar Nicholas II and his family had been exiled to Siberia, first in Tobolsk and later in Yekaterinburg, trying to live the lives of ordinary citizens. The actions of the Czech Corps made the local Bolsheviks fearful that the royal family would soon fall into enemy hands and become a symbol of anticommunist resistance. On July 16 Nicholas, his family, doctor, servants and even his dog were herded into the cellar of their house and shot to death.

So far the Allies had been offended by everything the Bolsheviks did: proclaiming a philosophy that rejected every Western ideal, getting out of the war without their permission, refusing to pay the huge foreign debts of the pre-1917 regime, and executing the tsar. The adventure of the Czech Corps convinced them that the communist government could be easily overthrown, so in July British, French and American troops landed at the Arctic ports of Murmansk and Archangel, occupying a large stretch of the USSR's northern coastline. This was followed by a landing of Americans, British and Japanese at Vladivostok, and they advanced several hundred miles up the Trans-Siberian Railroad, stopping at Chita, just 242 miles east of Lake Baikal. Officially these forces were only there to recover the war materiel that had been shipped to Russia before 1918, but once that was done they began to actively help the White Armies, especially that of Admiral Alexander V. Kolchak, which at this point occupied everything between the Urals and Lake Baikal. After World War I ended the Allies made even more attempts at intervention; the French landed at Odessa to give support to Denikin and the Ukrainians, and the British came through Iran to occupy Merv (in Turkmenistan) and the Baku oilfields.

By 1919 a truly formidable list of anti-Bolshevik groups had appeared. They were as follows:

White Army Commanders

Admiral Kolchak (Siberia)General Denikin (Ukraine, 1918-19)

General Nikolai Yudenich (Estonia)

General Pyotr Wrangel (Ukraine, 1920)

Baron von Ungern-Sternberg (Mongolia, God knows what he was doing there!)

Minority Groups Seeking Independence

CossacksEstonians

Latvians

Lithuanians

Georgians

Armenians

Azerbaijanis

Ukrainians

Central Asian Moslems

Foreign Powers

FinlandGreat Britain

The United States

France

Japan

Poland

The Russian Civil War, in the summer of 1919. Click on the thumbnail for a full-sized map (557 KB, opens in a separate tab). From Emersonkent.com.

Throughout late 1918 and early 1919 these factions advanced toward the central part of the country where the Bolsheviks were still in control. The low point for the Bolsheviks was June-October 1919, when 86% of the old Russian Empire was under enemy control (everything but the yellow area in the above map). Only the most important part of the country--Petrograd, Moscow, and the Volga River--remained to the Bolsheviks. But the largest White Army, Kolchak's, was also the worst organized. A conservative who wanted to see the old autocracy restored, Kolchak refused to grant land reform, even though it made his soldiers ("peasants in uniform") unreliable. Riots and mutinies broke out constantly behind his advancing troops, and Red partisans also hindered his progress. Under these circumstances it only took one defeat to stop him, and when this happened on the banks of the Volga in June Kolchak was sent fleeing back eastward. Following the Trans-Siberian Railroad, the White Army abandoned Omsk, Kolchak's capital, and headed for Irkutsk. However, a leftist faction had just seized control of Irkutsk and handed over the city government to the Bolsheviks, so when the train Kochak was riding reached Irkutsk, he was arrested and shot; his body was shoved under the ice of the frozen Angara River. After that incident (February 1920), Bolsheviks stood on the shore of Lake Baikal again. Kolchak's army tried to escape to China in the "Great Siberian Ice March," but only a fraction of them made it. The first leg of the march was across the frozen surface of Lake Baikal itself, because the Bolsheviks now controlled the railroad, and a terrible blizzard caught them on the lake, freezing most of them to death. Their bodies remained on the ice as a grim tableau until spring, when the ice melted and dumped them into the lake.

The other Whites did not do much better. Denikin advanced steadily northward until he reached Orel, only 250 miles from Moscow, in October 1919; at this point Lenin ordered false passports made, in case the government was forced to flee Moscow and go underground. But Denikin was unable to get the other anti-Bolshevik groups in his area, the Poles and Ukrainians, to cooperate with him. Part of this was his own fault; his favorite slogan was "Russia: one, great, and indivisible," and the non-Russians definitely did not want any more of that. As a result, when Denikin got to Orel his forces were stretched dangerously thin. As was the case with Kolchak, one defeat caused his army to collapse with amazing speed. By the end of 1919 the Ukrainians had lost Kiev to the Reds, and Denikin went into exile on an Allied ship. Command of his force went to General Wrangel, who was by far the most competent White leader, but he had come along too late to prevent a Red victory; one year later he too was leaving Russia on an Allied ship, along with the men he had left.

The story of General Yudenich is marked by amazing stupidity. While Denikin was driving north toward Moscow, Yudenich led a force of 20,000 Estonians and Russians to the gates of Petrograd. When he got there in October he expected the city to fall any minute and declared, "There is no Estonia. It is a piece of Russian soil, a Russian province. The Estonian government is a gang of criminals." The shocked Estonians removed their troops and went home; by November Yudenich also had to retreat because he no longer had enough men to take the city.

1920 was a year of mopping-up operations for the victorious Communists; by the end of the year the only resistance left was in isolated parts of the Caucasus and Central Asian regions, and Japanese-occupied east Siberia.(4)

When looking at the political situation, one would think that a White victory was inevitable, since they outnumbered the Reds in area and numbers of people. But the reasons why the Reds won are not hard to figure out. Five of them are listed below:

1. The Bolsheviks were united in purpose, forming a single, highly centralized, strongly motivated force. Their enemies, on the other hand, were a loosely united group made up of everything from reactionary officers to SRs and Mensheviks. Whenever the question of land reform or freedom for the minorities came up, they quarreled and eventually alienated each other (see the example with Yudenich above).

2. The Reds were more successful at economic efficiency than the Whites; their policy, called "War Communism," will be described in more detail later.

3. The Bolsheviks had superior leadership all around. None of their enemies could make impassioned speeches as well as Trotsky, and none of them had the self-discipline and talent for organization that Lenin did.

4. Even at their nadir in 1919, the Bolsheviks still controlled most of the country's railroads and factories.

5. The Allied intervention, which was slow in arriving and carried out badly. Morale among the Allies (except the Japanese) was poor; now that the "Great War" was over, most of them just wanted to go home. They also worked at cross-purposes; e.g., the Japanese wanted to take part of Siberia for themselves, forcing the other Allies to spend much time talking them out of it. The aid given to the White armies had a negative propaganda effect because the Reds could claim that their enemies were tools of foreign imperialism while the Bolsheviks were the real defenders of "Mother Russia." By the end of 1919 most of the Allied troops had departed, their strange adventure forgotten by almost everybody in the West today.

The Russo-Polish War and the Comintern

Poland had been restored as a nation by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, but the new Polish state was rather small: about 2/3 the size of present-day Poland, though its boundaries included virtually all of the Polish people. For the Poles this was not good enough; they wanted the wide borders of pre-1772 Poland, and the fact that the territory in question was inhabited by Lithuanians, Belarusians and Ukrainians did not matter to them. The collapse of the Ukrainian state convinced the Poles that they better grab as much territory as possible before it was too late, so in May 1920 they captured Kiev. But the Polish army had only ten divisions and was stretched to its limits; one month later the Red Army took back Kiev and it was Poland's turn to face an invasion. The last battle of this strange seesaw struggle was fought a few miles from Warsaw in August; that ended in a Polish victory. For a while Lenin had seen the Russo-Polish War as his best opportunity to spread communism to the rest of Europe; now he reverted to the logic he had used at Brest-Litovsk. Keeping communism alive in Russia was the most important priority and if that meant independence to the Baltic states and letting the Poles have most of what they claimed, he was prepared to do it. Five treaties signed in 1920-21 between Russia and Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland marked the western boundary of the USSR until 1939.

Throughout the entire civil war period Lenin hoped that communist revolutions in the West would take the foreign pressure off Russia. Even before World War I ended communist governments had been set up in Estonia and Finland, but the Germans quickly replaced them with anticommunist regimes. From 1919 to 1923 there were eight procommunist uprisings in Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Bulgaria. All of them failed; the closest thing to success came from Hungary, where Bela Kun ruled a communist government from March to August of 1919, only to be thrown out by a Romanian invasion.

To encourage more revolutions abroad, Lenin set up an organization for foreign communists called the Communist International, or Comintern. Many future communist leaders, like China's Zhou Enlai, Vietnam's Ho Chi Minh, Yugoslavia's Josip Broz (later known as Tito), and Germany's Walter Ulbricht attended the meetings. But in the short run the Comintern was a failure; after Poland's victory in 1920 the Comintern stopped getting actively involved in foreign politics, though it continued to exist as an institution until 1943. During those years the only successful communist revolution was in Mongolia, which declared independence from China in 1921.

The New Economic Policy

In 1921 the Soviet Union, after having defeated its enemies, was alive but not well. The ravages of two wars and two revolutions in the previous seven years had destroyed the Russian economy. Industrial production was down to only 20% of its 1913 level, and the small supply of food that had caused the February Revolution would have looked plentiful compared to what was available four years later. Immediately after the Russian Civil War came years of famine so bad that even the Allied countries sent economic aid to stop mass starvation. H.G. Wells wrote this in The Outline of History after he saw the damage up close:

"When the writer visited [sic] Petersburg in 1920 he beheld an astonishing spectacle of desolation. It was the first time a modern city had collapsed in this fashion. Nothing had been repaired for four years. There were great holes in the streets where the surface had fallen into the broken drains; lamp-posts lay as they had fallen; not a shop was open, and most were boarded up over their broken windows. The scanty drift of people in the streets wore shabby and incongruous clothing, for there were no new clothes in Russia, no new boots. Many people wore bast wrappings on their feet. People, city, everything were shabby and threadbare. Even the Bolshevik commissars had scrubby chins, for razors and such-like things were neither being made nor imported. The death-rate was enormous, and the population of this doomed city was falling by the hundred thousand every year."(5)

Throughout the Civil War years the government had kept itself going by a process of emergency appropriations called "War Communism." This involved forced labor, tightly controlled commerce, confiscation of all surplus goods, removing nonessential people from the cities to work the farms, and a general leading of civilians in a military manner. For the ordinary people this was a disaster; farmers starved because their crops were confiscated to feed the Bolsheviks and the Red Army, while workers were motivated to only do enough work to keep their jobs, since they knew that the fruits of their labors would be confiscated, too. Though the suffering of the masses was obvious, the radical wing of the Communist Party wanted War Communism to continue it until the last vestiges of capitalism were eliminated. By 1921 War Communism had become so oppressive that the sailors from the Kronstadt naval base revolted again, this time against communism. At the same time peasant revolts occurred in different parts of the country.

Using the Red Army, Trotsky quickly put down all these uprisings, but Lenin feared them more than he did the White Armies; after all, the rebels were the same people who had helped him gain control of Russia in the first place! At the Tenth Congress of the Communist Party (February 1921) he announced that the Party had overreached itself and must try a new policy. Since it had taken seven years of destruction to bring the country to this point, he reasoned, seven years of recovery will be needed before progress toward socialism can continue. The New Economic Policy (NEP) that he now formulated was effectively a step back to capitalism: private enterprise was made legal again, the government removed all controls from the economy, taxes replaced expropriations, and the country was allowed to recover at a natural rate. Hardline communists scornfully referred to those who profited from the NEP as "NEP-men," but the plan worked; by 1928 agricultural production was back to the 1913 levels, and 5% of the peasants, a group called the kulaks, actually grew wealthy enough to hire other peasants to work on the fields for them. Industry did not fully recover--it needed more supervision than it was getting--but growth was seen there, too.

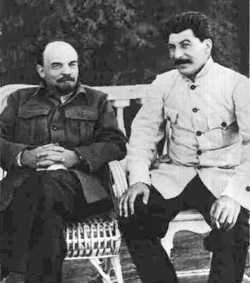

The Struggle to Succeed Lenin

NEP was the last accomplishment of Lenin's career. In 1922 he was incapacitated by three strokes, and never fully recovered. To keep his work continuing, Lenin offered his job to Trotsky, but Trotsky refused, pleading ill health. A new job was created that promised to give its holder most of Lenin's work but none of his glory; the position was called "Secretary General of the Central Committee." To use a term from today's corporate world, the person in that job would be the human resources director of the Communist Party. The only member of the Politburo (the highest council of the Communist Party) who wanted the job was the Commissar of Nationalities, Joseph Stalin. But once Stalin had it, he used it to place his friends in key positions of power, and to make important connections, effectively making him the real leader of the party, in fact if not in name.

Lenin and Stalin together, 1922.

As time went on, Stalin grew increasingly arrogant, intolerant and rude, even to Lenin and his wife. At the end of 1922 Lenin wrote a memo to the other Party members, warning that: "Comrade Stalin, having become Secretary General, has concentrated enormous power in his hands; I am not sure that he always knows how to use that power with sufficient caution." He then recommended that Stalin be removed at a convenient time, and called on the party to stay united in purpose. Stalin and his cronies, however, suppressed the memo called Lenin's Testament as soon as they heard about it.

Despite Lenin's urging, the Party split into two factions over the issue of the USSR's future. The left wing of the Party, led by Trotsky, Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev, advocated these ideas:

- "Permanent Revolution" (Spread communism everywhere)

- "Primitive Socialist Accumulation" (Redistribute the wealth so that everyone has the same amount)

- Dump the kulaks, go to immediate industrialization.

- "Socialism in One Country" (Build up the Soviet Union before spreading revolution abroad)

- Continue NEP indefinitely, perhaps even 25 years.

- Help the farmers first.

Surprisingly, Trotsky was not in Moscow for the funeral; Stalin gave him the incorrect date for the occasion. That left Stalin as master of ceremonies, and he played that role to the hilt, making himself appear as Lenin's most loyal follower. Contrary to Lenin's intentions, an official cult of his personality began; Petrograd was renamed Leningrad, pictures and statues of him popped up all over the country, and his embalmed body was placed in a large Red Square mausoleum, where visitors still pay their respects today.

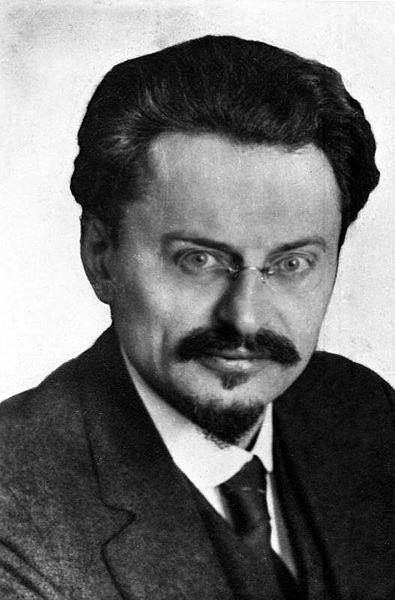

Before I go on, I should mention something about the two men who now wanted to succeed Lenin. Stalin and Trotsky had some similarities in their biographies to this point. Both of them were born in 1879, under different names from what we commonly call them now. Both of them came from ethnic minorities, but both gave up their heritage to make themselves acceptable to Russians.(6) Both of them were active Party members from the time they grew up, and both were in exile when the 1917 revolutions began (Trotsky in America, Stalin in Siberia). But in personality the two men were very different. Trotsky was a brilliant speaker and writer, with an ego to match, while Stalin was the quiet, organizing, calculating type. Trotsky had been in the limelight as a Bolshevik leader since the 1905 Revolution, while Stalin was as inconspicuous as a bug under a rock, even after he had been promoted to the Politburo in 1917. It was the clash between their personalities that set the stage for the events that followed.

Trotsky must have thought that since he was so popular, he could become leader of the Soviet Union whenever he asked for it; that's the only way to explain his lack of activity while Stalin was bringing the rest of the Party around to his side. By not criticizing Stalin while Lenin was alive, and by missing Lenin's funeral, Trotsky made two grave errors. In May 1924 Lenin's Testament was read to the Central Committee; Stalin offered to resign, but Zinoviev persuaded the Central Committee to suppress the memo again.(7) Even Trotsky voted to suppress Lenin's Testament at this point, feeling that Party unity mattered more than his personal success. That was his last chance to oust Stalin, and in the next few years Stalin effectively cut out the ground from under him:

1925: Trotsky loses his job as War Commissar.

1926: Trotsky is expelled from the Politburo.

1927: Trotsky is expelled from the Central Committee, and later the Party.

1928: Trotsky is expelled to Alma-Ata, in Kazakhstan.

Every step of the way Trotsky continued to denounce Stalin, especially when he could catch Stalin making a mistake. Having had enough, Stalin exiled him from the USSR in 1929. Trotsky wandered around the world for eleven years after that, warning of the dangers of Stalinism. Finally in 1940, an assassin sent by Stalin caught up with Trotsky in Mexico City and drove an ice-axe into his brain. That was Stalin's policy: eliminate all enemies, both actual and potential.

This is the end of Part I. Click here to go to Part II.

FOOTNOTES

1. Even the Mensheviks wanted to continue the war until it ended in victory.

2. Before 1918 Russia used the Julian calendar, which runs thirteen days behind the Gregorian calendar of the West. Because of that the two revolutions of 1917 are called the February and October revolutions, though the main events actually took place in March and November.

3. The secret police, the most feared arm of the Soviet government, was originally called the CHEKA, and was founded by a ruthless Pole named Felix Dzerzhinsky. Under Stalin it became the NKVD, and from Khrushchev onwards it was known as the KGB, but all of these organizations acted in the same way.

4. To avoid fighting the Japanese, the Soviets declared that the Siberian territory east and south of Lake Baikal was an independent "Far Eastern Republic," but then promptly re-annexed it after the Allies departed from Vladivostok in 1922. Some Japanese troops remained on the north half of Sakhalin island as late as 1925.

5. Wells, H. G., The Outline of History, Garden City, NY, Garden City Books, 1920 (revised in 1949), pg. 1131.

6. Stalin even forgot the Georgian of his birth, speaking nothing but Russian after he was about 30.

7. It was not published until 1956.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Russia

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|