| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 14: THE GREAT WAR

1914 to 1919

This chapter covers the following topics:

It Started as the Third Balkan War

From a political point of view, the twentieth century began on June 28, 1914. The thirteen years before that fateful day saw the same sort of peace, socioeconomic progress, and optimism that marked the late nineteenth century. In other words, those living in 1901-13 had more in common with the recently concluded Victorian era than they did with the rest of the twentieth century.

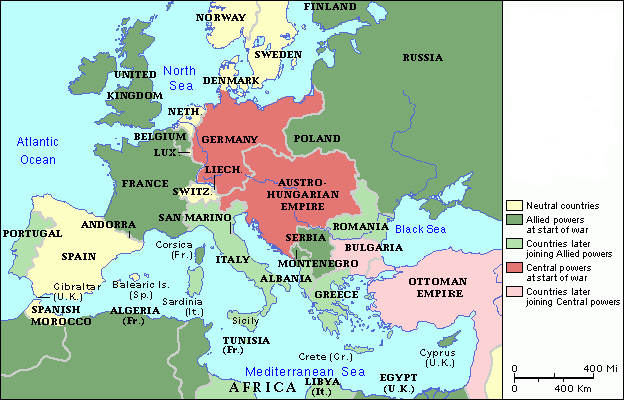

Europe in August 1914. Source: Grollier Online Atlas.

The immediate cause of World War I was the chronic Balkan problem, in this case Austria-Hungary's ongoing efforts to make the Bosnians see their future with the Hapsburgs rather than with the Serbs. When everything else failed, the governor of Bosnia invited Archduke Franz Ferdinand to make an official tour of the province. He could stay at Ilidze, a pleasant little resort, watch the army's summer maneuvers and chat with the local dignitaries. As for Bosnia's population, it was hoped that if enough of them saw the archduke on the tour, they would realize he was their friend. The archduke accepted the invitation; so did his wife, Sophie, because in Bosnia, unlike in Vienna, the emperor would not be around to treat her like a commoner.

Next, the governor's staff drew up an itinerary for the trip. Not long afterwards, a copy of this document was delivered to the desk of Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijevic, Chief of Serbian Intelligence. This was not the colonel's only job; he had been one of the assassins that killed the previous king of Serbia in 1903, and under the code name of Apis, he led Crna Ruka ("The Black Hand"), a terrorist organization dedicated to the creation of Yugoslavia. A radical hates a reformer more than he hates his enemy, and Dimitrijevic decided that eliminating the archduke was the best way to serve his cause. Still, he didn't want Serbia to be blamed for the assassination, so first he tried to scare the archduke away. On June 5, the Serbian ambassador warned the Austrian finance minister that it would be dangerous for the archduke to come to Bosnia; somebody in the welcoming crowd might have a gun loaded with real ammunition, not blanks. This was dismissed as a groundless fear, so you could say World War I happened because the finance minister couldn't take a hint.

Franz Ferdinand and Sophie began their tour on June 25, 1914. On the first days, they watched the army on maneuvers, as planned. For June 28, because that day was both a Sunday and their 14th wedding anniversary, the first thing they did was attend a special mass, held in their hotel for them. Then they took a six-mile train ride from Ilidze to Sarajevo, the provincial capital. The crowd that came to see them in Sarajevo included six agents of the Black Hand; one of them threw a bomb at the archduke's car as it passed. The bomb hit the car but bounced off before exploding; no one was killed, and the only people injured were some spectators and a colonel in the next car. The archduke sped to the city hall, where he complained about being greeted with an assassination attempt, but then acted remarkably cheerful as he listened to a speech from the mayor of Sarajevo. Then he called for his car, so he could visit the colonel in the hospital.

Unfortunately, nobody had told the chauffeur about the change in plans, and he started driving to the museum, the next stop on the official itinerary; Franz Ferdinand had to call a halt while the misunderstanding was straightened out. That caused the car to stop alongside a sandwich shop, just as another member of the Black Hand, a nineteen-year-old Bosnian Serb named Gavrilo Princip, came out of the shop. This fellow thought there would not be another chance to get the archduke, after the Black Hand member with the bomb failed, so he went off to drown his sorrows with an early lunch, some "comfort food." Now seeing his opportunity, Princip put one bullet into Franz Ferdinand and another into Sophie; then he took a cyanide pill. The cyanide came from a long-expired batch, like the poison Napoleon had used a hundred years earlier (see Chapter 12, footnote #12), so it wasn't a fatal dosage. However, the bullets did their job; both the archduke and duchess were dead on arrival at the hospital.

The Lights Go Out

To modern readers it seems bizarre that the death of the Austrian emperor's nephew and heir became an excuse for everyone to start World War I. Franz Ferdinand wasn't even popular with the Austrian and Hungarian elites, who saw him as too wishy-washy; the Hungarians in particular hated him so much that for a little while the Hapsburgs feared his killer might be a Hungarian agent. This was the sort of crisis European diplomats would have handled easily in other times. But there were many other factors involved. One was the polarization of most of Europe at the turn of the century into two hostile camps, the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy) and the Triple Entente (Britain, France and Russia); this was caused by the modernization and arming of Germany, as we saw in the previous chapter. Another was the unhappy emperor himself, who had seen too many personal tragedies. He had narrowly escaped an assassin's knife in 1853, which made him a devout Catholic for the rest of his life. His younger brother Maximilian tried to become emperor of Mexico in the 1860s, only to end up in front of a firing squad. Another brother, Karl Ludwig, died of an illness he got from drinking bad water on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land (1896). His only son Rudolf was the nineteenth century's most famous love suicide. His beloved wife, the Empress Elizabeth, was stabbed by an Italian anarchist while visiting Geneva in 1898. Essayist Hermann Broch once wrote, "(The emperor) carried a burden of personal misfortune almost as excessive as in a Greek tragedy." For him Sarajevo was the last straw, and the benevolent old autocrat was too weary, too out of touch with reality to do anything but make pious warnings about the calamity that would soon strike the Slavs.

The Austrians got little out of Princip before he died of tuberculosis in prison; all they learned was that he and his fellow conspirators had gotten their training and equipment from Belgrade. Still, it was enough. When the Austrians realized they had a war on their hands, they first made sure that the Germans would back them up, and then they sent the Serbs an ultimatum: "Let our investigating teams follow up the leads we have in Belgrade--or else." To make sure that the Serbs wouldn't agree, they gave Serbia only forty-eight hours to reply. No sovereign state could accept a demand like this; the Serbs rejected it and on July 28, Austria-Hungary declared war. Next Russia mobilized, determined not to let the Austrians destroy their best friend in the Balkans. They had planned at first to only mass troops along the Austro-Russian frontier, so as not to threaten Germany. But the details of a partial mobilization were too much for the primitive Russian military machine. Faced with calling out all of his troops or none at all, the tsar chose to put them all on the active duty list. So did the Germans; they didn't really want to get involved, but they had promised to do so if a major power joined Austria's enemies. Then the Germans made sure that France would fight by asking for guarantees of neutrality that the French couldn't possibly give. In the first two weeks of August, while diplomats were hurrying about delivering declarations of war, the Central Powers(1) prepared to overthrow the Franco-Russian-Serbian entente.

Just about everyone expected the upcoming war to be a short one, a rerun of the "genteel wars" that marked most of the previous century. Young men in all participating nations had been brought up on stories emphasizing heroism, and were taught that someday it would be their duty to fight for the homeland, and die for it if necessary. In the case of Britain, this kind of war had not been fought since the battle of Waterloo, and those who believed every man needed to prove himself thought a major European conflict was overdue. Because all the wars any European could remember had been short, both sides expected to win swiftly, the result being that a few soldiers would get killed and the rest would go home full of stories to tell their grandchildren. In August the kaiser boasted to his troops: "You will be home before the leaves have fallen from the trees." In Britain hundreds of thousands of young men enlisted, far more than could be easily trained or equipped; all of them were eager to get involved in what looked like the adventure of a lifetime. When the first British soldiers went across the Channel, the rest protested, expecting the war to end before they got their chance to go for glory, and with a mind-set almost incomprehensible to us, some British officers refused to let their men wear steel helmets because they thought it was unsporting!(2)

Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1914.

Only later did everyone realize how much things had changed. There were too many countries involved to allow a short war, and technology had changed the weapons, strategy and tactics completely. The submarine, machine gun and barbed wire were used on a larger scale than ever before; as the conflict went on warplanes, poison gas and tanks were invented, though the generals were too old-fashioned to use them in ways that could win battles. For most of the war, they would pay for the lessons they learned with their soldiers' lives. The British, for example, contrasted the courage of their rank-and-file with the stupidity of their commanders, by calling their army a group of "lions led by donkeys." Yes, this would not be an easy war at all. The only observer who seemed to know this in August 1914 was the British Foreign Minister, Sir Edward Grey. As he watched the lamplighters making their rounds in St. James' Park, he remarked sadly: "The lamps are going out all over Europe. We will not see them lit again in our lifetime."

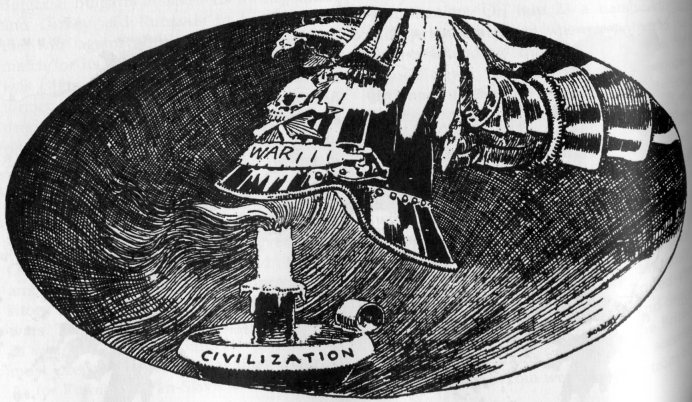

This cartoon, which illustrated Sir Edward Grey's statement, appeared in the Chicago Daily News on July 30, 1914, right before the fighting started.

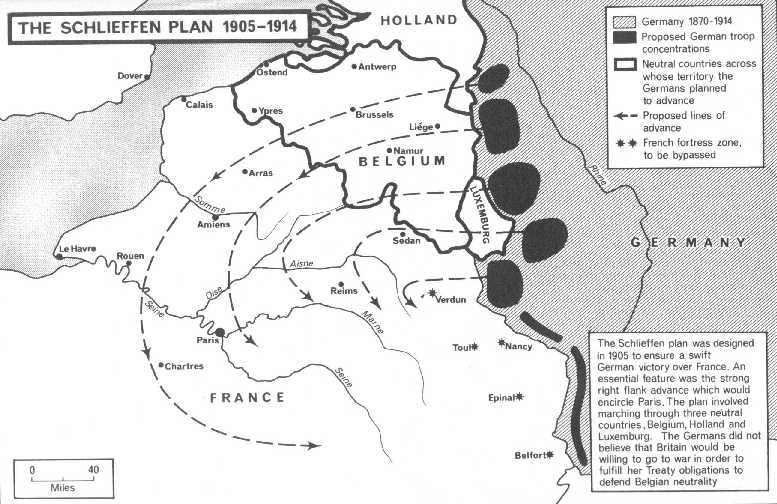

The Schlieffen Plan

The German army's plan for a two-front war was the work of Count Alfred von Schlieffen, the Chief of the German General Staff from 1891 to 1905. Early in his administration, France and Russia became allies, and Schlieffen knew that a war with one of those countries would probably become a war with both. His predecessors, Helmuth von Moltke and Alfred von Waldersee, had expected France to look for allies, and they made a plan for waging a two-front war, which involved defensive actions against France while trying to beat the other opponent first. Well, Schlieffen looked at the plan and realized that if the other opponent was Russia, a war fought this way could go on forever. Maybe the Russians could fight indefinitely, but Germany was long on technology and short on natural resources, so it would be in trouble if the war lasted more than a few months. What Schlieffen needed was a swift campaign that would knock out one opponent before the other could bring its forces to bear.

Russia was simply too big to knock out with one punch, but it would also take the Russians weeks, maybe months, to prepare and move their forces, so Germany would have time to beat France first. However, the French had used conscription to get enough troops to man the entire Franco-German frontier. An offensive here would require frontal assaults against fortified positions, not an appealing prospect for any army, especially one in a hurry.

Schlieffen's solution was a Prussian-style flanking maneuver, on a scale larger than anyone had attempted before. Instead of charging through the French, he would go around them. His plan called for the deployment of the entire German army on the western frontier, with two thirds of it stationed alongside the Low Countries. These divisions, known henceforth as the right wing of the army, were to march through Belgium, Luxembourg, and southern Holland as fast as they could go, the idea being to mobilize in two weeks and reach the Franco-Belgian frontier one week after the start of hostilities. From there they would sweep into northern France, wheel to the left, and catch both Paris and the whole French army in one enormous pocket. If all worked as planned, the campaign would be over in six weeks. The critical part in the maneuver would be played by the German 1st Army, the one farthest to the right; because it would form the rim of the German "wheel," it would have to move the farthest and the fastest, about twenty miles a day, to keep in step with the other units. And it would have to stay as close to the English Channel as possible, to make sure no French divisions escaped. As Schlieffen put it: "Let the last man on the right brush the Channel with his sleeve."

The Schlieffen Plan. Source: Atlas of the First World War, by Martin Gilbert.

It has been said that no military strategy survives its first encounter with the enemy, but the Schlieffen Plan was so rigid that any changes made to it invited disaster. The first problem was that it called for 100 divisions, but Germany only had 80 divisions when World War I began, so the all-important right wing would be understrength from the start. Then after Schlieffen retired, his successor, Helmuth von Moltke (a nephew of the other Moltke), made some more compromises. First, he revised the marching orders so that the right wing would not pass through Holland. Then he decided that ten divisions must be kept back to defend East Prussia. Schlieffen, hearing of these changes, wondered if Moltke really understood the thinking behind the plan. After all, did the burning of a few East Prussian farms matter so long as the campaign in the west succeeded? He sent memos explaining the need to hit the French as hard and as fast as possible; the evasive answers he got weren't reassuring. He was still worrying when he died in 1913. His last words were meant for Moltke: "If nothing else, keep the right wing strong."

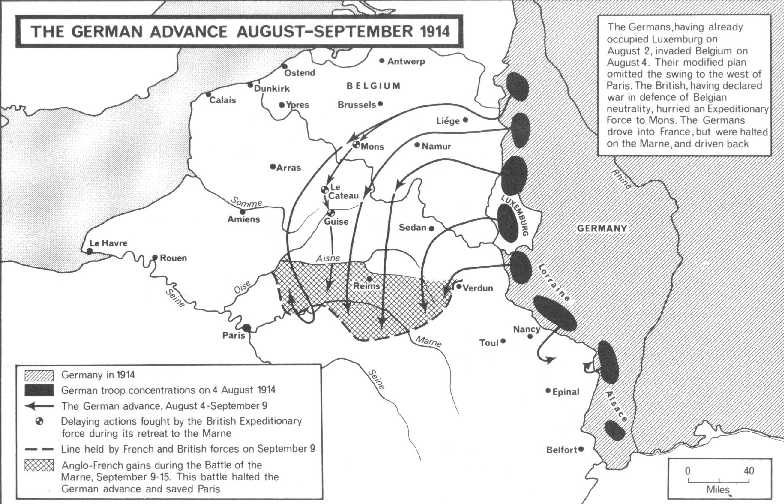

The Decisive Campaign

For a while it looked like Britain would not get involved in the war. The British were reluctant partners of the French, King George V had been making peace overtures to the kaiser in recent months (they were first cousins), and they had a rebellion at home to worry about (in Ireland). This encouraged the Germans to go ahead with the Schlieffen Plan. Because the Schlieffen Plan was the only plan they had for winning, they would now attack the French, who had so far shown considerable restraint in the whole crisis.

The Germans occupied Luxembourg on August 2, 1914, and sent the Belgian government a demand on the same day, to let their army march through Belgium. Would the Belgians fight to keep them out, and if they did, would the British join them? Within two days the Germans knew that the answer to both questions was yes. The German chancellor dismissed the 75-year-old treaty guaranteeing Belgium's neutrality as a "scrap of paper," and the German army invaded Belgium. Although Britain's declaration of war meant that every nation belonging to the British Commonwealth was also at war with Germany, the Germans weren't overly concerned; they were sure the war would be over before Britain could send enough troops to make a difference. But the Belgian decision was disappointing because it meant that the fortress complex at Liege, which lay right in the path of the German armies, would have to be taken out. And there were only ten days in which to do it if the Schlieffen Plan were to stay on schedule.

The main citadel of Liege was obsolete and its defenders knew it; it surrendered when General Erich Ludendorff drove up to it and banged on the door! Ringing the town, however, were twelve forts that had been built more recently (1892), with trenches full of armed men in front of them as a first line of defense, and because the Germans were pressed for time, these presented a real problem. Fortunately Krupps of Essen, the famous arms manufacturer, had two special 420mm cannon, designed to demolish forts. Normally guns that big were only used on battleships. The guns were delivered to the site in pieces, and took several days to assemble, but once in action, they reduced each fort to rubble in a few hours; one fort exploded completely when a shell hit its ammunition magazine. Delighted German soldiers nicknamed the guns "Big Bertha." The age when a territory could be defended by forts alone was over. Krupps delivered more Big Berthas to the front, and these were used successfully against the forts at Namur, Skoda and Antwerp in Belgium, and Maubeuge in France. General Alexander von Kluck's 1st Army, the force that was supposed to "brush the Channel with its sleeve," was able to start moving on August 17, almost exactly as scheduled.

On August 22, von Kluck encountered the British Expeditionary Force at Mons. In the first battle between British and Germans, the British got the better of it (1,600 British vs. 5,000 German casualties). Still, the British units weren't strong enough to stop the German advance; at this point the Germans had a two to one numerical superiority over the troops of the Allies (the name now given to the Triple Entente and their associates) on the Western Front. The British fell back, von Kluck crossed the Franco-Belgian frontier on August 24, and Moltke was so confident of a quick victory that he pulled four divisions from the right wing and sent them east to shore up defenses on the Russian front. The first phase of the great offensive, the conquest of Belgium, had proceeded perfectly.

The French commander, Marshal Joseph "Papa" Joffre, responded with a counter-offensive, a direct thrust against the German center in Lorraine. Germany couldn't have had a more cooperative opponent. The French put on a magnificent show at first; the bright blue coats and red trousers of the infantry and the gleaming breastplates of the cavalry stood out against the drab grey uniforms of the Germans.(3) But while Joffre had been in the army since 1870, he had never led troops in battle. This showed in his unimaginative plan for the attack, a document known simply as Plan 17. As another official manual declared, "Only two things are necessary: to know where the enemy is and to decide what to do. What the enemy intends is of no consequence." In other words, wars are won by the side with the most guts. This doctrine would have been questioned by anyone familiar with military history, but since most Frenchmen were too young to remember the last war France fought in Europe, it had become an article of faith among them. It soon withered away when the French charged with blind courage into the crossfire of rifles and machine guns. Within two weeks the French had lost 300,000 men and were falling back everywhere, sadder, wiser and fewer.

Meanwhile, the dead hand of Schlieffen continued to guide the Germans. Von Kluck kept to his schedule, though he had to fight soldiers from three armies (the British, Belgians and French); by September 1 he was right where he was supposed to be, at Amiens, fifty miles north of Paris. The Schlieffen Plan called for the 1st Army to march on the west side of Paris while the nearest army on von Kluck's left, the 2nd Army, marched on the east side of Paris, thereby encircling the French capital. Expecting the capital to fall shortly, the French government evacuated to Bordeaux, almost all the way on the other side of France. But each German army was now suffering heavy casualties, and the generals narrowed their front lines to keep up the momentum of their attacks. The general commanding the 2nd Army, Karl von Bülow, pleaded with von Kluck to turn more sharply left than planned, to keep a gap from forming between the 1st and 2nd Armies. Von Kluck did so, but this meant shortening the whole German line; the 1st Army would pass east of Paris, not west of it.

On September 3 von Kluck crossed the Marne River, and here, forty miles from Paris, his right flank was hit by a French force, delivered by the taxicabs of Paris. Von Kluck turned around and beat off this attack without difficulty, only to learn with dismay that while he had been shortening his front the French had been lengthening theirs. By using the railroads to transfer whole divisions, the French had built up the numbers opposite von Kluck's force until they had both outnumbered and overlapped it. It was immediately clear at this point that the Schlieffen Plan had failed. On Moltke's orders an attempt was made to break through in the center, but instead on September 9 the Germans on the right wing began to pull back to the Aisne River. The Allies surged forward, claiming that the battle of the Marne was a decisive victory. They were right, but the victory came from the strategies used, rather than the personal bravery of those soldiers involved.

How the Schlieffen Plan actually worked out. Source: Atlas of the First World War, by Martin Gilbert.

The Schlieffen Plan failed for the same reason as Plan 17: nobody took into account the firepower of the machine gun, which now gave the defender an awesome advantage. Machine guns had been invented more than forty years earlier (see Chapter 13, footnote #14), but until now, they had never been used in battles that pitted European against European; machine guns had been used by white soldiers against nonwhite warriors and civilians, in the many colonial wars beyond Europe. For an attack against an enemy with automatic weapons to succeed, it required more attackers per defender than anyone had foreseen, which is why the Germans had to shorten their line as they advanced and the French had been able to lengthen theirs as they retreated. But at the time it was thought that the generalship of the two sides had been the main reason for the outcome. Moltke was compared with Joffre, who kept a cool head throughout the whole campaign; indeed, this was Joffre's best quality. But whether he stayed calm because he knew what he was doing (as his admirers believed) or because he never realized how bad things really were (as his detractors claimed) is irrelevant. Nor did Moltke's "failure of nerve" influence the result. It was the commanders on the German right wing, including von Kluck, who ordered the retreat and they did so when they realized that the Germans, and not the French, were about to be outflanked; General Headquarters wasn't directly involved.

Blameworthy or not, Moltke had a nervous breakdown and had to be dismissed on September 14; the war minister, General Erich von Falkenhayn, took his place. Falkenhayn did his best to recover the initiative. As fast as new divisions could be raised, he sent them into Belgium and northern France with orders to get a new flanking movement going. The Allies also moved divisions into the area to keep the Germans from going around them, beginning a race to the Channel. In the end the king of Belgium may have won the race for the Allies. Like the Netherlands, part of Belgium is reclaimed land with an elevation below sea level, so the king ordered the opening of the sluice gates holding back the sea, flooding the part of Flanders where the Germans were trying to outflank the Allies. When troops from both sides reached the Channel, there was no longer any flank to find; from Switzerland to the Belgian town of Ypres, troops stood in an unbroken 500-mile-long line. The fighting became bloodier, but as hard as both sides fought, little movement was possible. Nobody had any idea how to storm a position defended by rifles or machine guns without losing more soldiers than the enemy would lose. By mid-November movement stopped completely; both sides dug in for the winter and the incredibly filthy war of the trenches had begun.(4)

Other Events of 1914

When the Germans advanced into Belgium, the Russians, as they had promised, invaded East Prussia. Ten divisions advanced into Germany's northeastern corner from the east; another army of the same size attacked from the south (Poland). The first skirmishes favored the Russians and the German commander in Prussia panicked; he telephoned Moltke to say that he was outnumbered two to one and would have to retreat. On the eastern front, if not the western, Moltke did the right thing; he sent both reinforcements and a new commander, General Ludendorff. At the age of fifty, Ludendorff was rather young for such an important command, so Moltke gave him General Paul von Hindenburg as a front man. Hindenburg was a career officer who had retired in 1910. Though he looked impressive and came from a highly respected Prussian family, he had no outstanding achievements to show for his time in the army, so detractors called him the "Wooden Titan." Now he was sixty-seven years old, delighted to be back on active duty and perfectly happy to let Ludendorff do the thinking. Their partnership would last for the entire war.

Ludendorff arrived in the east to find that a plan for a counterattack had already been prepared. The basic idea was to concentrate every available unit against the southern Russian army, defeat it or drive it back, and then go after the eastern one. The Russians had no maps or reconnaissance aircraft, and were in a territory full of forests, lakes, rivers and marshes, so they moved at a ponderously slow rate, guaranteeing that the Germans would be able to strike first before the two Russian armies came together. They also unwittingly gave the Germans the advantage by using uncoded radio signals. When a Russian officer was killed in a skirmish and the Germans found plans for the entire campaign on his body, they knew exactly what the Russians were up to. Ludendorff may have wondered at this point if the whole Russian strategy was a ruse; it had been almost too easy for him. Still, he attacked where he believed the Russians were, for a victory that would go down in military textbooks. The battle of Tannenberg was a classic envelopment that almost completely wiped out the southern Russian force. Then he marched east to encounter the other Russian army at the Masurian Lakes and drove it out of Prussia with crippling losses. It was a breathtaking feat of arms, something to offset the failure in the west. Ludendorff didn't even need the four divisions Moltke had sent him from the Western Front; they were still traveling across Germany when the East Prussian battles took place.

Austria-Hungary also had two war fronts, but performed miserably on both. The Hapsburg empire was so far behind western Europe, in supplies and technology, that you could say it never really entered the twentieth century. When the main Austrian force moved north into Russian Poland, a Russian countermove from the east hit it in the side. The Austrians failed to recover their balance and by the end of the year all Galicia was in Russian hands. Even worse, their invasion of Serbia, which they had predicted would be a cakewalk, ended in a humiliating rout; the outnumbered Serbs pursued the Austrians all the way to Slovenia. The Austrian generals just couldn't seem to do anything right.

The Germans were understandably bitter about this. The Austrian army had promised much, but was a complete liability. One German general complained, "We have shackled ourselves to a corpse." And speaking of corpses, the Ottoman Empire, the traditional "Sick Man of Europe," joined Germany and Austria-Hungary in October. The attacks launched by the Turks--against the Russians in the Caucasus and the British in Egypt--had as much fantasy in them as the Austrian war plans.

1915

By the end of 1914, Germany, France, Russia and Austria-Hungary had each lost between 750,000 and 900,000 men, so in 1915 nobody attacked with the recklessness that marked the first battles. The enthusiasm of August 1914 had been replaced on all sides by a grim determination to see the struggle through, so that those killed will not have died in vain.

There seemed to be no way to break the stalemate in the west. Any would-be attackers on either side faced formidable defenses: machine guns, barbed wire, trenches and artillery. An army could always break through a spot in the enemy line by throwing enough artillery shells and men at it; the hard part was that cavalry could not survive under such conditions, and artillery could not follow the soldiers through the shell-torn wilderness created by these attacks. This meant that the defenders could usually regroup and stage a counterattack before they were forced to retreat more than a mile or two. And some parts of the Western Front were too marshy or rugged to launch an effective offensive from, so most of the battles in Belgium and northern France would be concentrated in the same sectors. These sectors became charnel houses of horror, filled with bones and bodies of the unburied dead, with the ground churned up every time artillery pounded it or the armies dug new trenches.

Before long British officers were calculating that they would need to sacrifice three British lives for every two Germans they killed, and that they would need a 13:8 superiority in numbers if they were going to have any men left to hold the battlefield after the fighting was over. It's hard to imagine warfare getting any nastier than this!

Most of the time the Western Front seemed like a contest to see which side could die faster, but both Germany and the Allies worked to find a quicker way to victory. When the Germans attacked Ypres in 1915, they introduced a ghastly new weapon--poison gas. Thousands were killed or maimed by the gases used: first chlorine, later phosgene and mustard gas. If any soldiers at this date still saw warfare as a romantic business, this idea was now dispelled; there is nothing noble or romantic about fighting, when people are being gassed like insects. However, gas was not used everywhere, and the Allies soon had primitive gas masks.(5) As in future wars, poison gas failed to win any battles, but now all soldiers would have to prepare for an encounter with this horror.

We often think of the Germans as expert mechanics, but the tank was a British invention. The idea of "land battleships"--gun-carrying armored cars--had appeared in science fiction stories shortly after the automobile was invented (the name "tank" was a code word to confuse spies). A few prototypes became available in 1915, and they first saw action in late 1916. These slow-moving monsters frightened the Germans, but the Allies didn't have enough tanks to win battles until 1918.

In addition to land and sea, the air now became a place for fighting. At the beginning of the war the airplane was a fragile flying machine, only suitable for reconnaissance. However, aircraft-building technology progressed rapidly; soon fighter planes were sturdy enough to carry bombs, and had machine guns synchronized to fire at targets in front of them without damaging the propeller. Few pilots lived long enough to become "aces"; those who did, like America's Captain Eddie Rickenbacker and Germany's Manfred von Richtofen (the "Red Baron"), were the war's most celebrated heroes. At the same time, the tactic of bombing enemy cities made civilians a target worth attacking. Despite the attention given to the pilots and the panic caused by the bombings, warplanes had a marginal effect on World War I. Not until the next war would the airplane become an important tool for winning every battle.

General Falkenhayn found enough things to do, even if they weren't war-winning strokes, to keep himself busy in 1915. First there was the Austrian sector of the eastern front, which badly needed shoring up. Falkenhayn sent a German army to western Galicia and in May it smashed through the Russian line. This became the southern arm of a huge pincer movement into Poland; the northern pincer was provided when Hindenburg and Ludendorff struck south from East Prussia. Warsaw fell in early August; by early September the Germans had all of Russian Poland. Once the Russians were pushed a safe distance away, Falkenhayn closed down the war's first really successful offensive; like Schlieffen, he believed that even the most dramatic eastern advance would run out of steam before Russia collapsed. Then he sent the troops south to help Austria with its other problem, Serbia.

Falkenhayn had a new card to play here, for Bulgaria, still bitter at her defeat in the Second Balkan War, decided to join the Central Powers. This made the second invasion of Serbia an easy success. As Germany and Austria-Hungary launched the main attack from the north, Bulgaria opened up a second front in the east; the whole country was overrun during the month of October. 150,000 Serbian solders managed a magnificent fighting retreat across the Albanian mountains, taking 25,000 Austrian prisoners with them. An Allied naval force rescued the Serbs when they reached the Adriatic, but it didn't change the results. Those Serbs who survived starvation, freezing temperatures and raids from the Albanians spent the rest of the war in a camp the Allies set up for them at the Greek port of Salonika, while the Central Powers went to work brutalizing their country.(6)

The Allies tried to help the Serbs by opening up a new front from Salonika, but this expedition was too little and too late. The Bulgarians had no trouble chasing it back to Greece, where it sat uneasily on the territory of an officially neutral country and served no useful purpose. This failure was all the more embarrassing because there had been enough troops in the Aegean during the summer to bring about a victory, but they had been squandered in an attempt to take Constantinople and knock the Turks out of the war. This expedition was so badly planned that it never got beyond the beaches of the Gallipoli peninsula and by the time it was called off (January 1916, nine months after it started) the Turkish soldiers had proved they were not lacking in courage, though their equipment was in short supply.

For those keeping score, the Central Powers were ahead on most fronts by the end of 1915. Britain had built up its army on the Western Front until the Allies had a 3:2 superiority over the Germans, but the Allied offensive was beaten back with terrible losses (400,000 Allied dead against a German loss of less than half this number). Add to this another 250,000 Allied soldiers wasted on Gallipoli. In the east, Russia was crippled, Serbia was eliminated, and Turkey had survived its toughest test. The only good news for the Allies was that Italy joined them in May. Italy had offered to sell herself to the highest bidder, and since Austria held the territory she wanted, the Allies could offer a better deal. But Italy proved just as disappointing for the Allies as Austria-Hungary was for Germany. The Italians never got more than a few miles across the border in the eastern Alps, and the Austrians finally had an enemy they could take care of on their own.

1916

Beating the Russians and the Serbs helped the Central powers, but both sides expected the war to be won on the Western Front. Thus, 1916 began with Falkenhayn looking for a way to end the deadlock in the west. He decided that, since Germany's casualty count had been consistently lower than those of her enemies, a war of attrition might be the answer. His plan called for an attack at a point the French would defend at all costs, where he had the tactical advantage. This point was Verdun, the northernmost of the prewar fortresses that Germany had bypassed in the 1914 campaign. He wouldn't try to capture Verdun, just press it hard enough to draw in the bulk of the French army; then he would bleed it white. It would be expensive and slow, but the German army should be able to do it.

French soldiers at Verdun.

And here are the leftover shell casings from an Allied bombardment. Over 60 million shells were fired during the battle of Verdun; that works out to 150 for every square meter of the battlefield! According to the French Interior Ministry, as many as 12 million unexploded shells could be lying in the ground here.

Falkenhayn began the bloodiest battle in history on February 21, 1916. At first it looked as though the plan might work, but then, as the French learned how to counter the German tactics, the battle deteriorated into a struggle that was just as punishing for the Germans as the French. The final score after the attack was called off in July: 300,000 estimated German dead, 350,000 estimated French dead. Meanwhile, the British finally had as many troops on the front as the French, so they launched a massive assault in the Somme valley. This took the pressure off the French but turned another sector into an equally bloody mess. Four months of fighting gained the British 120 square miles, an area about one tenth the size of Rhode Island, but at an awesome cost: 419,654 lives, nearly one percent of Great Britain's population at the time. By the end of the year the total number of casualties on the Western Front had exceeded one million, but nobody could claim victory. For all this sacrifice, the front line had only shifted seven miles to the east.

British soldiers at the Somme.

In the east, where there were fewer troops per mile and the armies weren't so evenly matched, a war of movement was still possible. The Russians launched their last successful attack, the Brusilov offensive, in June and reconquered the eastern half of Galicia from the Austrians before the attack petered out in September. The main result of this was that Romania ended two years of fence-sitting and jumped in with the Allies. Romania, like Italy, wanted part of Austria-Hungary's territory; unfortunately, the Romanians, like the Italians, were so militarily inept that they failed to help the Allied cause.

In Austria-Hungary, Franz Joseph's 68-year reign ended with his death in 1916. A grandnephew succeeded him as Karl I. His two years on the throne were ineffectual ones, and today we only remember him because he was the last emperor of the venerable Hapsburg dynasty.

Other events worthy of note in 1916 included a Russian advance across the Caucasus into Turkey, and Germany's creation of a vassal Polish kingdom out of conquered Russian territory. This version of Poland was only a core territory around Warsaw; Germany and Austria-Hungary didn't give it any of the Polish lands they held before the war started. In fact, the Germans arrested its leader, Marshal Joseph Pilsudski, when he started acting too independent. Portugal joined the Allies in spring, and Greece declared itself in the Allied camp that summer.

The failure of Verdun discredited Falkenhayn; after the Brusilov offensive he was relieved of command. The Hindenburg-Ludendorff team now took command of both the east and the west. Ludendorff quickly turned about the situation in the east, by putting German officers and NCOs in the Austro-Hungarian units. Then he sent enough troops to Hungary and Bulgaria for them to take the offensive against Romania. The demoted Falkenhayn led the Romanian campaign, and he carried it out brilliantly. Because of Romania's geographical shape (like a backwards letter "L"), and Germany's talent for moving troops quickly by railroad, it was easy to arrange for attacks from four directions to cut off the southern half of the country (Wallachia). The end of 1916 saw the shattered remnants of the Romanian army hiding behind a Russian relief force in Moldavia, while the Central Powers drained Wallachia of its cattle, wheat and oil.

These new supplies were welcome, but they weren't enough. Britain had put a total naval blockade on the Central Powers at the beginning of the war, and by 1916 it was hurting them badly. Food was running short in Germany and the behavior of the people lining up for it was disorderly; several cities saw serious riots in the spring. Germans called the winter of 1916-17 the "turnip winter" because they didn't have much to eat, besides turnips and rutabagas. At the end of 1916, German diplomats offered a peace proposal--this would have ended the war while Garmany was still ahead--and Britain rejected it without giving it serious consideration. In Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey, the situation was even worse; the Austrians warned Germany that if the war didn't end in 1917, they would be finished. The Central powers needed a war-winning idea more than ever.

The best suggestion came from an unexpected source--the German navy. The naval commander, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, was one of the kaiser's favorites, but his surface fleet had gotten nowhere against the British. The surface naval engagement where Germany had its greatest success was the battle of Jutland, off the coast of Denmark, in May 1916. This battle pitted 99 German vs. 151 British vessels; the Germans sank fourteen ships while losing eleven. Thus, Germany was able to claim a victory, but because getting home safely was the Germans' top priority, Britain still ruled the waves.

Though Germany's battleships had failed to live up to expectations, the submarines, also called U-boats (from the German Unterseeboot), had done well. The catch was that U-boat attacks only did real harm when they were "unrestricted," meaning that they had to be free to attack any ship that belonged to the Allies, both military and civilian. In 1915 a U-boat sank a British ocean liner, the Lusitania, killing 1,198 civilians (128 of them American). The United States wouldn't stand for this, and warned that it would declare war on Germany if the attacks continued, so the German admiralty agreed to stop them. One reason why they did was because of a shortage of U-boats; with only twenty-five available for action at a time, they couldn't wage an effective campaign. By the end of 1916, however, there were more than a hundred U-boats, and the German admirals claimed that, free of restrictions, they could sink 600,000 tons of shipping a month. Six months of this ought to be enough to bring famine to Britain and halt her economic engine. America would enter the war, but it would take a year and a half for the Americans to build up an army and ship it across the Atlantic; by then it would all be over.

1917

The U-boat campaign began on February 1, 1917. At first, everything went as planned, with the U-boats sinking the predicted 600,000 tons of Allied shipping per month (This included the ships of neutral nations that came too close to the British Isles.). Britain was reduced to four weeks' supply of some essential materials, and German hopes were high. The British quickly responded with convoys to escort the merchants and liners; by May this had cut losses to a more tolerable 300,000 tons monthly, and the U-boats never really got on top of the situation after that. The tonnage sunk gradually dropped back to the level they were at before restrictions were lifted, while hydrophones and depth charges caused U-boat losses to rise steadily. Instead of winning the war, the submarine captains made sure that Germany would lose it; the United States declared war on April 6.

The German people didn't pay much attention to the Americans at this point because they believed that--in Europe anyway--everything was finally going their way. The Russian tsar had abdicated in March, his army was withering away, and it was only a matter of time before the Germans could dictate peace on their own terms for the eastern front. France was almost as war-weary as Russia; morale was so low that when they were ordered to march across No Man's Land into German machine gun fire for the umpteenth time, some French soldiers went bleating like sheep. The British didn't do much better; the battle of Passchendaele saw them sacrifice another quarter million lives to gain fifty square miles of mud in Flanders.(7) There was every reason to believe that victory in the west would quickly follow victory in the east. Overseas, Germany had lost all of its colonies except German East Africa, but this caused little concern; victory in Europe would allow the Central Powers to recover all their losses at the conference table.

Just how bad it was for the French was shown by what happened when they tried a new commanding officer. In December 1916 Marshal Joffre was asked what strategy he was planning for the next campaign, and he proposed a repeat of the battle of the Somme. That was too much; the French government kicked Joffre upstairs and replaced him with General Robert Nivelle, who promptly planned a grand offensive. Britain liked Nivelle because he spoke perfect English and was a great optimist; he declared he could drive the Germans back without suffering more than 10,000 casualties, and most importantly, promised to call off the offensive if it did not get favorable results within forty-eight hours. Cautious politicians in Paris tried to talk Nivelle out of it, since Verdun had nearly bled the French Army to death. The Germans heard what Nivelle was planning, prepared defenses in depth along the Aisne River, and pulled back from the Somme to a powerful line of fortifications, called the Hindenburg Line. Nivelle paid no attention, and launched his attack in April. It failed, like all other French offensives to date. Often waves of French soldiers overran the lightly guarded first German line of defense, thinking they were now winning, only to get hammered when they came within range of the troops and guns on the Hindenburg Line. By the standards of the war, it was a small failure, costing just 120,000 casualties. Even so, Nivelle had promised much and delivered nothing. He continued pouring men onto the battlefields, ignoring casualty reports and refusing to accept defeat. In May, thousands of men deserted, and whole divisions refused to go into battle. A Russian division, sent to the Western Front as a friendly gesture, rebelled openly. The French soldiers simply couldn't take any more. By June, fifty-four divisions--half the French army--were in a state of mutiny, and there were no reliable troops left between the front line and Paris.

Somehow the French were able to keep the mutiny secret from the Germans until they restored order. In Paris the government collapsed; the new leaders dismissed Nivelle from his command, and Henri Philippe Petain, the hero of Verdun, took his place. Petain promised better rations, pay raises, more leave time--and no more futile assaults. Unlike his predecessors, he would wait for tanks and the Americans to arrive before going on the offensive. Forty-six ringleaders in the mutiny were shot, while the Russians were surrounded and destroyed by artillery.

On the Italian front, eleven battles had failed to get the Italians across the Isonzo River. In October the Austrians inflicted a crushing defeat at the battle of Caporetto. 260,000 Italians were captured, another 200,000 deserted, and the Austrians occupied nearly all of Venetia. France and Britain had to rush troops to Italy to keep Venice in Allied hands.

The Last German Offensive

1918 began with negotiations between Germany and Russia's new communist government to end the war on the eastern front. Germany was in a hurry to get its soldiers over to the west, but that didn't stop the kaiser's diplomats from demanding the toughest terms they could possibly get, terms which amounted to Russia abandoning one third of its people and the same proportion of its European territory. Lenin accepted, because Russia needed peace, no matter what the price. Details of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed in March 1918, may be found in Chapter 4 of my Russian history.

Once Russia was taken care of it was Romania's turn to sign the dotted line. When they did so (in May) a piece of Moldavia went to Austria-Hungary while the southern half of Romania's coastline (Dobruja) went to Bulgaria. The northern Dobruja was also detached, though it was never clarified in the last months of the war who would get it (presumably Germany). Neither was Bessarabia (modern Moldova), which was separated from Russia; because Germany was totally occupied elsewhere, the Romanians got away with adding Bessarabia to their kingdom, as partial compensation for their losses.

Now that Hindenburg and Ludendorff had won the war in the east, they had to do the same in the west. And they only had spring to do it in, because the Americans would be there in strength by summer. Once their troops were shifted from east to west, the Germans had a numerical superiority (200 German divisions vs. 170 British & French), but this would not last long. They would have to strike the critical blows in March and April. History texts call this campaign the Spring Offensive, the Ludendorff Offensive, or Kaiserschlact ("the Kaiser's Battle"), depending on whom you're reading.

Ludendorff launched his first attack, Operation Michael, in the Somme sector, by positioning 70 specially trained "assault divisions" against 35 British.(8) The opening day (March 21), saw the biggest artillery bombardment for 1918, and the biggest casualty count for any day in the entire war (78,000 killed and wounded on both sides). By the time German troops marched forward, the British line was gone; whole battalions had vanished, never to be seen again.

Avoiding the front line did not necessarily keep you safe during this offensive. On the day the offensive began, shells started falling on Paris, though no German planes or zeppelins flew overhead and no artillery pieces were nearby. The Germans had built a really big artillery cannon, which they called the Kaiser Wilhelm Geschütz ("Emperor William Gun"); the Allies called it the Paris Gun. The gun fired a 234-lb. shell that could hit a target up to 81 miles away; Parisians could not hear them coming because the shells traveled at five times the speed of sound, and on their trajectories, the shells went up to an altitude of 26 miles before coming down, making them the first manmade objects to reach the stratosphere. While the gun certainly had value as a psychological weapon, it turned out to be a waste of resources when it came to actual damage inflicted. Because of its size, it could only fire about twenty shots per day, and since it could not be aimed at a target smaller than a city, casualties were less than expected: 256 killed and 620 wounded. All copies of the Paris Gun were destroyed in August 1918, to keep them out of Allied hands. A generation later, during World War II, the Germans would build another supergun, called the V-3, so they could shoot at London from the French side of the English Channel, but Allied bombing raids prevented the completion of this secret weapon.

Within a week some German units had advanced forty miles, ten times farther than any Allied force had gone in the same amount of time. It was a magnificent replay of 1914, but it wasn't enough. The Germans were exhausted, and because of the British naval blockade on Germany, they were hungry, having less food to eat than their opponents had. In addition, offensives work best when the troops have some sort of cavalry leading the way, but after four years of fighting, the Germans had run out of horses, and unlike the Allies, they would not have tanks until the next war. For these reasons, the German offensive ground to a halt in the second week; German losses (especially among the new elite units) began to exceed Allied casualties, and Operation Michael had to be closed down. The same thing happened with Ludendorff's second and third attacks, Operation Georgette in April and Operation Blücher in May; both of these were tactical successes but strategic failures.

Operation Blücher took the Germans to the Marne again. At this point, German troops were close enough to Paris that the French government talked about moving to Bordeaux, in southern France. But the Germans were in the forest of Chateau-Thierry when they reached the Marne, and here, on May 31, they ran into American troops. There were only two divisions of them, but the psychological impact was enormous. By the reduced standards that ruled this late in the war, any American unit was at double strength, because these men and their equipment were fresh. Six days later, when the French were withdrawing from the adjacent forest of Belleau Wood, they ordered US Marine Captain Lloyd Williams to retreat, and he shouted back, "Retreat? Hell, we just got here!" Soon the German Command reluctantly reported that: "The American soldier proves himself brave, strong and skillful."(9) And on top of all that, there were plenty more Americans on the way. By the end of June there were ten American divisions in the front line; by the end of July, twenty; by the end of October, thirty. Time had finally run out for Germany.

The Central Powers Give Up

Ludendorff launched two more grand assaults after the Germans met the Americans, in June and July of 1918. Both were turned back after gaining just a few miles of territory, and from then on the Allies always had the initiative. They were now better organized as well; a French officer, Marshal Ferdinand Foch, became supreme commander of all Allied forces on the Western Front during the German spring offensive. In August their local counterattacks turned into a grand advance; if it never quite matched the pace set by the Germans in 1914 and early 1918, it was better sustained and thus more effective. Every day the Germans had to withdraw somewhere along the line. The tactical situation loosened up slightly; first because the Allies finally had enough tanks to break through the German defenses, and second because the armies no longer stood still long enough to dig in. Attacks were still expensive but not prohibitively so and, as the Allies ground steadily forward, the morale of the German army finally began to fray. In September the main German defensive barrier, the Hindenburg Line, was breached, meaning that Germany's last hope of even fighting the war to a draw was gone.(10)

The signs that Germany was going to lose were quickly read by the other Central Powers. Italy, with British and French help, liberated its occupied territory in the course of four months (June-October 1918). In mid-September the much ridiculed part-French, part-Serbian, part-British army in Greece launched a major attack on Bulgaria, and the Bulgarians almost immediately decided to throw in the towel. As Bulgaria withdrew from the war, British forces raced to the Turkish frontier, French columns reached the Danube and the Serbs made a good start on liberating their homeland. The Turks held out until the end of October before they surrendered, during which time Syria was conquered by the Allies.

It was a long road from Belgrade to Vienna, but the Allied armies never had to march on it; Austria-Hungary fell apart first. October saw Czech nationalists seize control of Prague and proclaim it the capital of an independent Chechoslovak state, while the Poles and Ukrainians of Galicia looked to become either a part of the new Polish state or the short-lived Ukrainian Republic. Meanwhile the Slovenes, Croats and Bosnians repudiated both Austrian and Hungarian rule and declared, with surprising unanimity, that they would join with Serbia and Montenegro to form a single Yugo-Slav state. Even the Italians successfully advanced against Austria-Hungary at this point. With help from some British and French troops, the Italians pushed on the Adriatic coast to the Isonzo River, which is where they were when the Italian phase of the war began, three years earlier. On the way, the Allies captured 300,000 enemy soldiers and 5,000 guns. All that was left was for coups in Vienna and Budapest to declare separate Austrian and Hungarian republics, and the Hapsburg empire ceased to exist.

Germany stood alone as November began. On the third day of the month the sailors of the German fleet mutinied rather than sail on a death-or-glory mission against the British. It looked like many army units were about to do the same. And a third of Belgium had been liberated. The kaiser reluctantly conceded that the war was lost, but the Allies would only talk peace to the German people--not the military or monarchy--so on November 9 he abdicated. A number of important Germans gathered in the city of Weimar to discuss and write a new constitution, so today we call the government that came after the kaiser the Weimar Republic. Two days after the abdication, an armistice was signed in a railroad car near Compiègne, France, and the guns fell silent for the last time. Any hope that this would be a truce between equals was quickly dashed; the terms of the agreement amounted to a complete surrender.

The Germans surrendered here. Marshal Foch is the one standing behind the table. The railroad car will be used again in World War II.

The Germans signed because they had one hope left. The American president, Woodrow Wilson, declared that the postwar frontiers of Europe would be decided by the people, not the politicians. Self-determination would be the most important principle, with plebiscites to determine the people's will. On this basis Germany wouldn't do too badly, which is why the Germans chose to negotiate with the idealistic Wilson and not his European allies. True, the president said that there would be exceptions to the rule (Alsace-Lorraine would go to France so that the French would lose their interest in revenge, and the new Polish state--whose existence all parties had agreed on--would be given a seacoast carved from German territory), but if Wilson had his way, Germany would end up clipped instead of crippled.

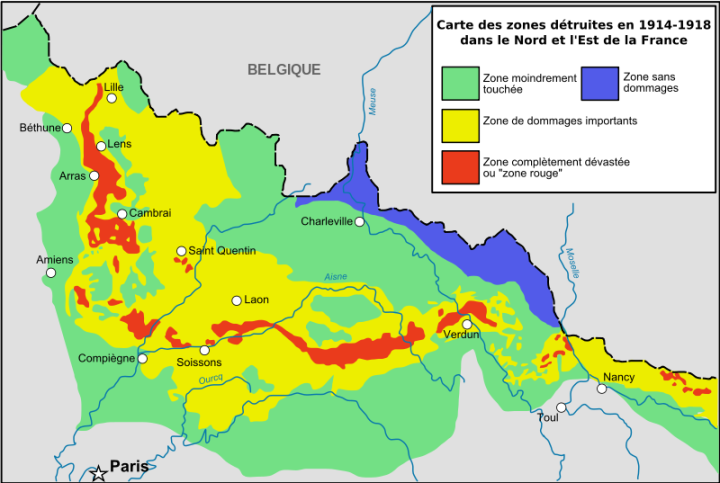

The cost of the war, in lives and resources, was staggering. Germany had lost 1,827,000 men, or 12% of its male population between the ages of 15 and 50. France had also lost most of a generation--1,400,000. Austria-Hungary lost 1,350,000 men, Russia lost nearly two million. Italy lost 700,000; Serbia lost 350,000; Britain and its dominions lost 950,000. Because it was a late participant, the United States lost a mere 115,000, about half of them victims of disease. The grand total for everybody came up to ten million dead, twenty million wounded. Add to this the civilian casualties caused by invasion and bombings; epidemics of cholera, typhus and influenza; malnutrition and famine; perhaps another ten million innocent lives. Finally, the war was hell for animals. Because horses had been used for cavalry early in the war, and remained in use all through it to move artillery and supplies, more than eight million horses died on the Western Front alone.

Belgium and northern France were utterly devastated. During the course of the war, the armies on the Western Front fired approximately 720 million shells and mortar bombs at each other. The red areas on the map below, the Zone Rouge, were so ravaged that the French government relocated the residents living there. Even now, more than a century after the war, the public is not allowed to go in the red zone, nor may farmers work the land, because the land contains toxic chemicals, the remains of countless soldiers, and unexploded ordinance. In the nearby yellow and blue zones, farmers dig up an "iron harvest" of nearly 900 tons of shells, bombs, grenades and bullets every year.

A French-language map of the Western Front in France today. From Wikimedia Commons.

For France and Great Britain, the cost of the war in money was estimated at 10% of the national wealth. Never in history had a single war come so close to destroying civilization. It was called the Great War, the "war to end all wars," for a generation--until a second world war, an even more destructive conflict, set the world ablaze again.

This is the End of Chapter 14.

FOOTNOTES

1. Just Germany and Austria-Hungary at this point. Italy and Romania were allies of theirs, but both of them chose to sit out the war at this date, arguing that the alliance was purely a defensive one, and that they had no obligation to support Germany or Austria-Hungary if they were the aggressors. Later on they entered the war on the other side.

2. Likewise, when steel helmets became available to the French army, General Joseph Joffre did not bother to order any, because he thought the war would end before they could be delivered to his troops. In the east, the Russians imported some helmets of the French design, but most Russian soldiers did not wear steel helmets until the 1930s.

3. Indeed, the French cavalry at this point wouldn't have looked out of place if it was in Napoleon's army, one hundred years earlier. By now the other armies were dressing their men in colors that helped them hide, instead of making them easier to see. Whereas in previous wars British soldiers wore red uniforms, and American soldiers wore blue, from World War I onward, almost every country's soldiers would wear grey, brown or khaki.

On the other side, the Germans were easy to recognize because of their spiked helmets. This fashion, the Pickelhaube, had been passed down from the Prussian army in the nineteenth century. As the war dragged on, however, the Germans decided it was more important for their gear to be functional than showy, so in 1916 they began to issue the Stahlhelm, a helmet that was all steel (the Pickelhaube was partially made of leather), did away with the spike and had a flared rim to give more protection to the neck. During the next war the Stahlhelm became a symbol of the Wehrmacht, so you could say the German army was dressed for World War II, before World War I was over.

|

|

| The Pickelhaube. | The Stahlhelm. |

4. The 1914 German invasion of Belgium caused a wave of anti-German hysteria in the Allied countries. The Russian capital was renamed Petrograd because St. Petersburg sounded too German, and because Gotha bombers starting attacking Britain, King George V changed his family name from Saxe-Coburg-Gotha to Windsor. Below is a cartoon from the British humor magazine Punch, showing George V sweeping away his German heritage. In 1947 the future Queen Elizabeth II married Philip Mountbatten, Duke of Edinburgh, so today the official name of the British royal family is Mountbatten-Windsor.

While we're on the subject of British royalty, note that George V was the first English monarch since the Wars of the Roses who was more English than anything else. For most of the previous 1,400 years, England's dynasties were foreign in origin. The Anglo-Saxons were German, the Normans were Vikings turned into Frenchmen, the Plantagenets were fullblooded French, the Tudors were Welsh, the Stuarts were Scots, William III was Dutch, and the Hanoverians and Saxe-Coburg-Gothas were German again. I'll venture that if there are any more dynastic changes in London, it will be Ireland's turn to have someone on the throne next time.

5. The Germans tried poison gas on the Russian front first, only to find out that the frigid cold of an eastern European winter turned the gas to liquid and made it useless.

6. Austria-Hungary also occupied Montenegro and most of Albania as it chased the Serbs to the sea. Greek troops had moved into the southern quarter of Albania, ancient Epirus, in October 1914, to protect the Greek minority living in that area. Because of the Greek presence, the Central Powers did not occupy the whole country. In 1916, Italian and French troops took the place of the Greeks.

Today's Serbs will talk at length about how World War I started and how it ended--history is an important subject to anyone from eastern Europe--but they say very little about how bad things were during the four years in-between. The Austrians left Nikola Pasic, the pre-war prime minister, in charge of Serbia, because he had opposed starting a war over the archduke's assassination. In 1917 he had Princip's patron, Colonel Dimitrijevic, executed on a charge of treason. Thousands of Serbs would suffer a similar fate before the country was liberated in October 1918.

7. Before Passchendaele, the British won a minor victory in the battle of Messines. Messines was a ridge the Germans controlled near Ypres. The British commander in charge of taking the ridge back, General Herbert Plumer, was a real pyromaniac, and determined to start the battle with a bang (literally). So determined, that he spent eighteen months preparing the explosives. Miners dug secret tunnels from the British trenches to Messines, and planted twenty-two colossal landmines in the ridge, under the Germans. Each mine got at least 25 tons of TNT; more than 600 tons of explosives were used altogether. One mine was discovered and exploded by German counter-miners in August 1916. They did not find the rest, though, and when Plumer was ready to go, he said, "Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography."

At 3:10 AM on June 7, 1917, Plumer gave the order and nineteen mines were detonated. These were the greatest controlled explosions anyone had attempted, up to this date. Prime Minister David Lloyd George claimed he could hear the explosions from London, and an insomniac student in Dublin claimed he heard them, too. Each mine blasted a crater more than a hundred feet wide on the surface, and the British infantry marched forward to take what was left of the ridge. We're not sure how many Germans were killed, but they lost at least 10,000 troops; this was one of the few battles during the war where the defender suffered heavier casualties than the attacker.

Did you notice that I said twenty-two mines were planted, the Germans blew up one, and the British detonated nineteen? The last two mines were not used, because there weren't any Germans within range of them when the battle began. After the battle the British promised themselves they would remove the unexploded mines, but never got around to doing it, because of other battles. Soon they lost track of where they had put the mines, so everyone forgot about them, until a lightning strike set off one of the mines on June 17, 1955; fortunately the only victim killed in that explosion was a cow. No one knows for sure where the remaining mine is, or if the TNT can go off after this much time in the ground. Remember that if you're planning to visit western Flanders, and have a nice trip.

8. These German units were called "storm troopers" and maintained the offensive by carrying light machine guns. Avoiding frontal assaults, they always followed the path of least resistance, leaving enemy strongpoints to be dealt with by the general infantry behind them.

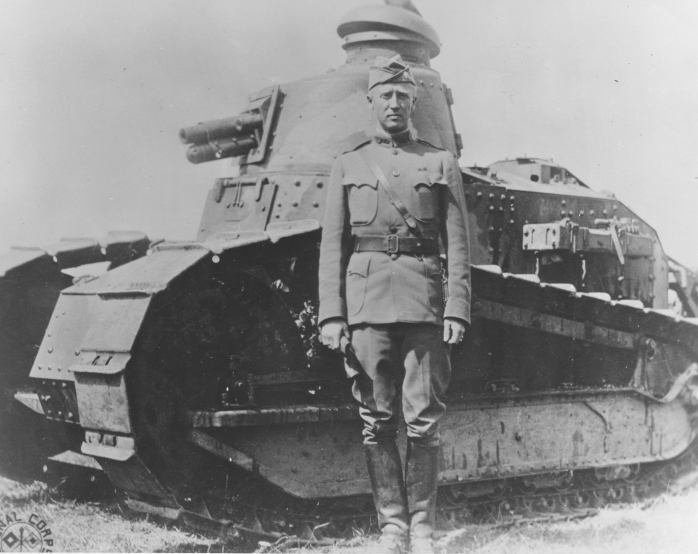

9. The United States established its first tank corps in 1917, and the first American soldier to join was an officer we'll be hearing a lot from in the next war, then-Captain George S. Patton. Patton guessed that he would see more action with the newly invented armored vehicles than he would if he stayed with the infantry. Before the year was over, Patton, now a colonel, was sent to find a good location in France for a tank training school; he decided a village named Bourg would do, because it had lots of mud to practice driving in. While there, the mayor of Bourg came to him with tears in his eyes, because he had failed to tell Patton of the American soldier who had died in Bourg. Patton quickly checked, and found that no one in his unit was dead or missing, but the mayor insisted that he at least visit the soldier's grave.

The mayor proceeded to take Patton to a mound of dirt with a stick posted in the ground at one end. Nailed crosswise on that stick was another piece of wood with the words "Abandoned Rear"; evidently the French had mistaken the sign for a cross. It wasn't a grave but a recently closed latrine; the dirt and the sign had been left by the last person using it!

Patton didn't tell the French the truth about that spot. In 1944, during World War II, General Patton returned to Bourg and was given a hero's welcome by those who remembered the last time he was there. He relived memories by visiting his old office and living quarters, and noted that the village was still respectfully maintaining the "grave" of "Abandoned Rear."

George S. Patton with his FT-17 tank, summer of 1918.

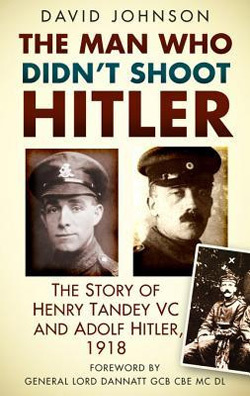

10. Here is a great "What if?" situation, for those who like to speculate on how history could have been different. On September 29, 1918, the British liberated Marcoing, a small French town. The hero of that day was Private Henry Tandey (1891-1977), a veteran of several other World War I battles, including Ypres in 1914, the Somme and Passchendaele. Twenty-seven-year-old Tandey saved the day for the British by taking out a German machine gun nest, and then he repaired a bridge, replacing several missing planks so that his buddies could use it. While doing this he was still under fire from the Germans, and took a couple of hits himself. Nevertheless, he continued marching to Marcoing, and on the way, a wounded German soldier came into view. Tandey raised his rifle at the German, who seemed to know his time was up. Suddenly, Tandey decided there had been enough killing, and couldn't bring himself to shoot a wounded man; he put the rifle down, and the German nodded in thanks and got out of there.

Because of his involvement in so many battles, Tandey was the most decorated private soldier of the war. King George V awarded Tandey the Victoria Cross, Britain's highest medal for valor, for what he did at Marcoing, but in the long run, sparing an enemy soldier undid all his other achievements, for the German he let go was Adolf Hitler. After that, Hitler talked about how "providence" had saved him to do great things, and eventually he acquired a copy of a painting that showed Tandey at Ypres, carrying a wounded soldier. When Neville Chamberlain met Hitler in 1938, Hitler showed him the painting, said that was the man who almost shot him, and asked the prime minister to take a kind message to Tandey. Chamberlain did, giving Tandey a phone call after he returned to London. Of course Tandey wasn't happy to learn that his act of kindness had led to all the unpleasantness of the late 1930s, but by then he was too old and had too many injuries to re-enlist in the army. Later he lamented, "If only I had known what he [Hitler] would turn out to be ... When I saw all the people and women and children he had killed and wounded, I was sorry to God I let him go."

Today there are some skeptics who don't believe Hitler and Tandey ever met. They will point to evidence that Hitler was in another sector of the Western Front on that day in 1918, suggest that Hitler mistakenly thought the man who almost shot him was the same man that he saw in the painting, or that Hitler was just being a jerk, using the meeting with Chamberlain to embarrass a real war hero. For those reasons, Tandey could have finished his life without his conscience burdened by the thought that he had spared Hitler. What would you have done, if the decision not to shoot someone would cause terrible things to happen in the future?

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Europe

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|