| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 4: Industrial America, Part I

1861 to 1933

This paper is divided into five parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| Reconstruction | |

| The Free State of Van Zandt | |

| The Alaska Purchase, and the Only American Emperor | |

| Grant and the Beginning of the Grand Old Party Era | |

| The Brooks-Baxter War |

Part III

| The Panic of 1873, and the Barons of Wall Street | |

| The South Restored, and the Worst Happy Hunting Grounds | |

| The Great Railroad Strike | |

| The Spoils System Kills the President | |

| Grover the Good | |

| "I Will Fight No More Forever" | |

| The Great Barbecue | |

| The Gay Nineties |

Part IV

| The Spanish-American War | |

| Teddy and the Big Stick | |

| Big Taft and the Bull Moose | |

| Wilson the Reformer | |

| World War I | |

Part V

| The Age of Normalcy Begins | |

| The Roaring Twenties | |

| The Great Depression | |

| The Golden Age of Immigration |

America's Most Difficult Years

We are now ready to discuss the most destructive conflict in US history, the American Civil War (also known as the War Between the States, the War of Rebellion, the War for Southern Independence, or the War of Northern Aggression, depending on your point of view). Together the North and South recruited or drafted more than three million men into their armies and navies, a full tenth of the US population when the war started, of which approximately 600,000 were killed and 400,000 were wounded. More than 2,400 battles and skirmishes took place, 40 percent of them in Virginia and Tennessee, but spread over an area that stretched all the way from Picacho Pass, Arizona to St. Albans, Vermont (see the raid on St. Albans in Chapter 3). In addition the war cost $7 billion for both sides, destroyed property valued at $5 billion, brought freedom to four million black slaves, and left emotional scars that have not completely healed after more than a century and a half, especially in the South.

In the end the nation came back together again, but the Union that Northerners fought to preserve and Southerners fought to leave was replaced by another one. Before the war most Americans saw the federal government as a far-off body which they rarely thought much about; now Washington interfered so much in their lives that just about everybody expected it to do so again in the future. And the process of industrialization, having begun a few years before the Civil War started, would cause economic upheaval for generations. The United States would be transformed from a society of simple farmers and shopkeepers to a society of bustling cities, factories, railroads and big corporations. For the government and a few individuals, industrialization generated amazing amounts of wealth, and since capitalism gives power to those who have money, this meant that in the last years of the nineteenth century, the United States would become strong enough to take on any other nation. The war and industrialization are the reasons why the year 1861 was chosen as the date to begin the narrative for this chapter, and why "Industrial America" was chosen as the chapter name.

The Disunited States

In Chapter 3 we saw how the issues of states' rights and slavery had been present since the writing of the Constitution, but from 1820 onward they grew in importance, until the differences of opinion in the North and South could no longer be bridged. In the 1850s extremists on both sides got tired of shouting; they now felt they could win if they switched to shooting. We also saw that the South usually had its way in national policy, as long as the Democratic Party controlled the federal government. That ended with Abraham Lincoln's election to the presidency in 1860. Lincoln himself spoke in conciliatory tones after winning; while he made it clear he was not going to allow the further spread of slavery, in places where it was already established he would allow it to remain for the time being (see Chapter 3, footnote #72). Like other Northerners, he felt that time was on his side, so it wasn't necessary to do anything rash. And if it came to war, the odds were in the North's favor, too. In 1860 the North had the following assets:

- 61% of the nation's population

- 75% of the GNP

- 66% of the railroad mileage

- 81% of the factories

- 74% of all bank deposits

- 67% of the farms

For radical Southerners the 1860 election wasn't a signal to calm down, but a confirmation of their worst fears. No matter what Lincoln said, they didn't trust him, because was a Republican, and all Republicans were Abolitionists at this stage. If they wanted to avoid being assimilated into the industrial, liberal North, they had to get out of the Union before Lincoln took office.

Acting as if the dead Calhoun was still in charge, South Carolina went first. The South Carolina government called for a state convention, and on December 20, 1860, it unanimously passed an "ordinance of secession," which declared "that the union . . . between South Carolina and other States under the name of the United States of America is hereby dissolved." In January the other six states of the "Deep South" (Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas) passed similar resolutions to leave the Union. On February 1, 1861, representatives from six of those states met in Montgomery, Alabama (Texas was too far away to send a delegation in time for the meeting), and established a new national government, which they called the Confederate States of America (CSA). They drew up a constitution which looked a lot like the US one, with special clauses guaranteeing slavery and states' rights. Two former members of Congress, Jefferson Davis of Mississippi and Alexander Stephens of Georgia, were elected president and vice-president respectively.(3)

Together, these seven states formed a single block of territory, larger than most European nations and having the resources to grow a prosperous economy. Many Southerners dreamed of eventually building a slaveholding empire that would expand southward, all the way to the Amazon River. However, the North wasn't going to leave them alone for long, so first they would have to secure their independence. There were fifteen slave states in all, but the seven that had already seceded owned more than half of the slaves, so the other eight were less willing to kiss the Union goodbye. The question now was, would enough states in the "Upper South" join the Confederacy to give it a fighting chance?

The inauguration of President Lincoln in March was one of the gloomiest in US history. Whereas most of the congressmen from the seceded states had quit and gone home, a senator from Florida remained in Washington, still drawing his federal pay, while sending home advice on how to capture the US forts in his state. John Floyd, the outgoing secretary of war, withdrew 115,000 rifles and muskets from northern armories and sent them southward, most going to his home state of Virginia. In front of an unfinished Capitol building (the Capitol's present-day dome was under construction at the time), Lincoln told the South that it must make the first move: "In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. . . . You can have no conflict without yourselves being the aggressors. . . . We are not your enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies." But while Lincoln's inaugural address suggested that a peaceful resolution was still possible, it had no effect at all; everyone had heard words like those already. Two days later, Jefferson Davis ordered the Confederate states to raise an army of 100,000 volunteers.

Choose the Blue or the Gray

Though Lincoln did not want to fire the first shot, something would have to be done soon, because the US Army controlled four forts in Confederate territory--three in Florida and one in South Carolina--and all were badly in need of food and other supplies. Fortunately the Florida forts would not be much of a problem, because that state was militarily weak and underpopulated. As long as Florida lacked a navy, it could not blockade or attack the two forts in the Florida Keys, Fort Jefferson and Fort Zachary Taylor, and US Navy officers were confident they could get enough ships into Pensacola Bay to keep Fort Pickens going; in fact, all three forts remained in Union hands for the entire war. The tricky one would be the South Carolina fort, Fort Sumter. Located on an island at the entrance to Charleston Harbor, its defenses were unfinished, it had only half the cannon requested (due to military downsizing during the Buchanan administration), and it was surrounded by batteries held by the South Carolina militia. Resupplying the fort would be extremely dangerous if those batteries started shooting, and this was likely to happen because the fort had already ignored calls to surrender from Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard, the local commander. The only thing that could be done for Fort Sumter's garrison without starting a war was to arrange a truce, and use it to evacuate the troops.

Lincoln would have none of this; any negotiation with the rebels would be seen as giving them diplomatic recognition. Thus, Fort Sumter was a no-win situation for him. Lincoln gave the order to supply the fort, and following the rules of the day, let South Carolina's governor know that ships would be coming into Charleston Harbor for that purpose. South Carolina telegraphed the announcement to the Confederate government in Montgomery, which voted to reduce the fort. The bombardment of the fort began on April 12, 1861; 34 hours later Fort Sumter surrendered, and the American Civil War was on.

No country is ready for a civil war when it breaks out. Until now, armies of a few thousand men had been enough to defeat whatever enemy the Americans faced. The largest army George Washington ever led, for example, numbered 13,000, and that was for the Whiskey Rebellion, a confrontation that ended without any shooting. Now on the eve of the Civil War, the United States only had 17,000 soldiers, and more than half of them were stationed west of the Mississippi River(4), because in recent years Indians had been the biggest threat to US citizens.(5) The US Navy had only 76 ships, most of them obsolete, and 7,600 sailors, so a naval blockade of the South would be ineffective at this time. Accordingly, on April 15 Lincoln issued a call to the state militias for 75,000 volunteers to help "put down the insurrection." For the challenges at sea, Lincoln had an extremely efficient Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles; over the course of the war he expanded the navy to 700 ships.

Unfortunately, the battle of Fort Sumter and the call for troops aroused Southern patriotism as well as Northern. Two days later, Virginia voted 88-55 to secede.(6) Virginia was followed by North Carolina and Arkansas in May, and by Tennessee in June. June also saw the Confederates move their capital from Montgomery to Richmond, because Virginia was still the most important state in the South.(7) By the time summer began, the Confederacy had doubled its strength.

Most of the Virginia delegates who voted against secession came from the rugged area on the west side of the Appalachians. This region was poorer than eastern Virginia, had always been under-represented on the state and national level, and its white residents only had a few slaves. The local population contained 350,000 whites and less than 30,000 blacks, compared with 700,000 whites and 600,000 blacks in the east. The westerners had long resented how the rich eastern aristocracy claimed to represent them, and in May they held a meeting in Wheeling to discuss Virginia's secession; they decided to secede from Virginia in order to stay in the Union, and set up a pro-Union government to counter the pro-Confederate government in Richmond. June and July saw Northern soldiers, led by 34-year-old General George B. McClellan, move in from Ohio to occupy Virginia's mountains; this invasion had the full consent of the local population. At first Lincoln treated the Wheeling politicians as the rightful government of Virginia, but later decided that the two parts of the state were different enough to remain separated, so in 1863 the counties that refused to leave the Union became the youngest state east of the Mississippi, West Virginia.(8)

West Virginia showed that the first task of the new soldiers raised by the Union government would be to keep more places from seceding. Besides West Virginia, there were four slave states left: Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri. Lincoln felt he could not win the war without controlling all of them. Maryland was the most critical, because it surrounded the District of Columbia on three sides. With the Confederate flag flying on the fourth side (Alexandria County, VA), just across the Potomac River, this meant that Washington would have to be abandoned if Maryland went over to the Confederacy. Therefore Northern regiments were sent to Maryland and Washington as soon as they became available. The first unit in Maryland, the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment, was attacked by a hostile crowd as it passed through Baltimore on its way to Washington (the Baltimore Riot, April 19, 1861). To avoid further incidents, the mayor of Baltimore and the governor advised Lincoln to send reinforcements by way of Annapolis instead of Baltimore, and Lincoln did that until tempers cooled and the city was cleaned up. Then the "Boys in Blue" showed up in Baltimore again on May 13, and declared martial law; the locals, realizing they would not be able to get away with renouncing their US citizenship, glumly accepted that state of affairs. As for Delaware, it had voted against seceding on January 3, 1861, and was occupied by federal troops before it could change its mind, so Lincoln never lost any sleep over which way that state might go.

In the west, the Missouri legislature called a special session to discuss whether Missouri should secede. It voted 98-1 to stay, but the pro-Southern governor, Claiborne Jackson, had other ideas, and ordered the mobilization of the state militia. The Union army general on the spot, Nathaniel Lyon, acted quickly, using federal troops to surround the camp in St. Louis where the militia had assembled, and forcing them to surrender. While marching their prisoners away, the troops came under attack from a pro-Confederate mob and they fired back, starting three days of street riots that killed 28 and injured at least 100 (the "Camp Jackson Affair"). A meeting between Lyon and Jackson in June got nowhere, and Jackson began raising a new militia. Lyon responded by occupying the capital and installing a new governor, while Jackson fled to Neosho, a town in the Ozarks near the Arkansas border. Thus Missouri, like Virginia, now had two governments. During the next two months, Lyon won most of the battles as he tried to extend Union control over the rest of the state, until August 10, when he was killed in the battle of Wilson's Creek and his troops were routed. The Confederate force in Missouri, led by General Sterling Price, went on to win again at Lexington in September, but they could not completely undo Lyon's work. Although Price was able to stage raids as late as 1864, most of Missouri willingly accepted the pro-Union government Lyon established.

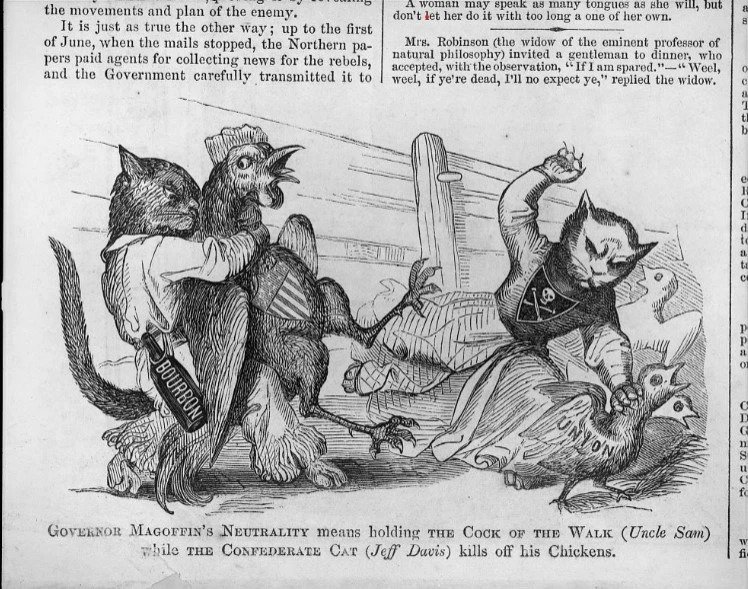

When it came to choosing sides, Kentucky was the last state to make up its mind. Kentucky was valuable to both sides for its hemp, tobacco, horses and railroads, and there was an emotional attachment; both Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis had been born there. The governor of Kentucky, Beriah Magoffin, was another Southern sympathizer, and when Lincoln asked him to contribute four regiments of Kentucky troops, he refused: "Kentucky will furnish no troops for the wicked purpose of subduing her sister Southern states." However, he didn't think he had the men to resist a Northern invasion, and because of the state's central location, most observers expected Kentucky would be right in the middle of a conflict between the North and the South. To avoid that scenario, in May the governor declared the Commonwealth of Kentucky neutral. As it turned out, this helped the Southern cause almost as much as joining it. Kentucky's neutrality protected the states below it, especially Tennessee, making it impossible for the North to come up with a sensible strategy for taking back those states. In addition, the spirit of Daniel Boone was alive and well in the rugged individualism that characterized Kentuckians; an invasion of their state by either side would make most of them join the other side. Lincoln knew that, and chose to wait and see what would happen, reportedly saying, "I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky."(9)

An 1861 cartoon about Kentucky's neutrality shows Beriah Magoffin and Jefferson Davis as cats. Source: Library of Congress.

Campaigns of 1861

The Union troops that invaded eastern Virginia in the summer of 1861 had no successes like those enjoyed by their brothers in West Virginia. The first general to try his luck there was Benjamin Butler, a Massachusetts politician-turned-soldier. Butler landed at Fort Monroe, at the mouth of the James River, and began to march on Richmond from the east. He passed Yorktown, the site of another fateful battle, and then his 3,500 men ran into 1,200 Confederates at Big Bethel Church (June 10). Both forces were made up of new recruits; the Northerners were so confused that they could not conduct a proper charge, so the Southern counterattack routed the Yankees. The North suffered 79 killed & wounded, while the South lost eight, and the Union troops fled all the way to Hampton and Newport News.

Because Butler commanded only a fraction of the troops in the "Eastern Theater," Lincoln saw Big Bethel as merely a dress rehearsal for a bigger battle. Now he turned to the highest-ranking soldier in the Union Army, Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, hero of the War of 1812 and the Mexican War. Unfortunately Scott was also 74 years old, and could no longer mount a horse or move quickly, so somebody else would have to lead the troops into battle. His first choice for a field commander was a Virginia officer, Robert E. Lee, but Lee went with Virginia when it seceded, so he settled for Major General Irvin McDowell. When Lincoln asked Scott what it would take to win the war, Old Fuss and Feathers predicted that the war would last five years, consume millions of lives, and require a campaign that involved Union armies cutting the South into pieces. As a less bloody alternative, Scott proposed a slow strangulation of the South through blockades, the "Anaconda Plan." Lincoln found this unacceptable, and never took advice from Scott again, but Scott was right; eventually the North won with this strategy.

By July Lincoln felt he had enough men to do things his way, with an all-out assault on Richmond, and he ordered McDowell to go for it. If Richmond fell quickly enough, it was hoped, a rapid collapse of the Confederacy would follow, and the war would end with no more bloodshed than had been seen in previous American conflicts. Accordingly, McDowell took a green force of 35,000 men across the Potomac River. On the other side, at Alexandria, General Beauregard waited with another green force of 24,000. To the west, in the Shenandoah Valley, two more armies faced each other, 18,000 Union troops led by General Robert Patterson vs. 11,000 Confederate troops led by General Joseph Eggleston Johnston.

Instead of making directly toward Beauregard's force, McDowell headed down the road to Richmond. Thirty miles from Washington, right after the road crossed Bull Run Creek, was Manassas, which had a valuable railroad junction; capturing Manassas would give the Union forces control over the railroads in northern Virginia. However, Beauregard learned through spies what McDowell was up to, and moved his men to Manassas first. In addition, the Northerners fell victim to overconfidence. They were so sure of victory that members of Congress and their families came along to watch the spectacle; those civilians would cause problems when the situation turned ugly for the Union Army.

Despite these factors and the lack of training among his troops, McDowell got off to a good start when the armies met on July 21, in what would be called the first battle of Bull Run. He tried hitting Beauregard's force on the left flank and succeeded in pushing it back to Henry House Hill. Unfortunately, McDowell had counted on the other two armies staying in the Shenandoah Valley, but instead Johnston brought out his army and placed it under Beauregard's command; this meant both sides would have the same number of men. One of the new arrivals was an officer named Thomas Jonathan Jackson, who stood "like a stone wall" on Henry House Hill and waited for the Yankees to come and get him. At the last possible moment his Shenandoah brigade jumped up from behind the bushes, fired at point blank range, and charged with bayonets. The man who would henceforth be known as Stonewall Jackson told them, "Yell like furies when you charge!", and that was the first time Confederate soldiers hollered the famous "rebel yell." Feeling that they could not go on without the advantage of numbers, the Northerners faltered, fell back, and then just ran away in panic. They didn't stop running until they reached the streets of Washington. If the Confederates had been up to pursuing the Yankees, they might have even taken the nation's capital. As is, Bull Run killed whatever hope the North had of winning quickly and easily.

So far in the "Eastern Theater," McClellan was the only Northern general with anything to be proud of. Because he had won several small Union victories in West Virginia, it looked like he would be the man to conquer Richmond.(10) Accordingly, Lincoln transferred McDowell to a new army being raised to defend Washington, and had McClellan take his place. McClellan began rebuilding the Army of the Potomac, though at the start he pointed out that it would take the rest of 1861 before they would be ready for the big challenge. Winfield Scott retired in November, after realizing that in this war, he could not even be useful behind a desk, so McClellan was promoted to fill his shoes as well.

Meanwhile in the west, the bad news from Bull Run was offset by the news Lincoln wanted to hear the most: Kentucky was going to be on his side after all. That summer saw special elections for Kentucky's ten congressional seats, and pro-Union candidates won nine of them. Then local elections were held, and because Southern sympathizers refused to vote, the result was a state legislature where more than two thirds of the members favored staying in the Union. Magoffin, however, stayed on as governor for one more year.

Thinking that Kentucky's neutrality was about to end, the Union government now established a recruiting and arms distribution center at Lancaster, KY, and a newly promoted Union general, Ulysses Simpson Grant, occupied Belmont in Missouri, just across the Mississippi River from the village of Columbus, KY.(11) However, it was Southern actions that decided the matter. General Leonidas Polk, the South's "fighting bishop" (he had been an Episcopal bishop in Louisiana before the war), invaded western Kentucky in September. His objectives were to seize Columbus and Paducah, which would keep the central Mississippi valley in Confederate hands, now that Missouri had been lost; it would also be the first step toward bringing Kentucky back into the Southern camp. Polk captured Columbus but Grant outwitted him by crossing the river and taking Paducah first. Another Confederate force, led by General Felix Zollicoffer, moved into southeastern Kentucky from Virginia, and before September was over Albert Sidney Johnston (see footnote #4) brought in a third force from Tennessee, taking Bowling Green and Russellville with it. In this area, 200 Southern sympathizers declared that Kentucky was the 13th state to secede, and they set up a rebel government at Bowling Green. Meanwhile in the rest of the state, the fiercely independent Kentuckians called for federal protection, and in Frankfort (the real capital) the state legislature declared that Kentucky was pro-Union. Lincoln's strategy of waiting had paid off again; the Union troops gathering in Ohio and Cairo, IL would be liberators, not conquerors, when they marched into Kentucky. Instead of securing the Mississippi, Polk had made Tennessee vulnerable to Northern invasions.

Ulysses S. Grant.

Far to the west, New Mexico had been claimed by the South as a slave territory before the war, and in March, the town of Mesilla, near modern Las Cruces, declared it would secede and join the CSA. In July a Confederate unit marched up from El Paso, Texas, entered Mesilla, and defeated the Union forces from the nearest fort, Fort Filmore. Fort Filmore was abandoned, and the Confederates proclaimed an "Arizona Territory" in the southern half of present-day Arizona & New Mexico, with Mesilla as its capital. Despite all this, the official governor of New Mexico was pro-Union, and in September he issued a call for soldiers (most of them were Spanish-speaking Mexicans from the neighborhood of Albuquerque and Santa Fe). Additional troops arrived from Colorado in December; we will soon see what happened when they met the Confederates.

Finding New Ways into the People's Pockets

Before the Civil War, the federal government got most of its money from tariffs and a few other taxes, and issued various bonds and notes when it did not raise enough revenue this way. Federal spending was kept low, because most administrations, from Jefferson to Pierce, thought accumulating debt was bad in the long run. The Buchanan administration allowed an exception to this rule, because the financial panic of 1857 had reduced normal income from tariffs and duties. In 1857 the national debt was $28 million, not enough to scare anybody, and by issuing bonds and notes to cover the shortfall in revenue, Washington added $76 million to the debt by 1861.

Then came the Civil War, and the calls to recruit hundreds of thousands of new soldiers. All those troops needed to be paid, and they also needed uniforms, guns, ammunition and food, so the Civil War was not only bigger than any previous war in North America -- it was also more expensive. And because both sides had originally expected the war would be short, Lincoln's Treasury Secretary (Salmon P. Chase), and his Confederate counterpart (Christopher Gustavus Memminger) did not think they would have to raise billions of dollars for the war effort, but that is what they eventually did.

To find new sources of revenue, President Lincoln called a special session of Congress in July 1861. The ideas considered at this session included the sale of government bonds, increased tariffs, new taxes or duties, and the sale of public lands. Congress approved a $240 million bond sale, and the introduction of an income tax; the latter was a flat tax of 3% on everyone making more than $800 a year. Before the new tax was collected, though, Congress passed a new Revenue Act (in mid-1862), to replace the Revenue Act of 1861. This modified the income tax, so that it collected 3% on annual incomes above $600, and 5% on incomes above $10,000 or on US citizens living abroad. Most important of all, the income tax was declared temporary; collection of it would end in 1866. After that, Americans would not be saddled with an income tax again for almost fifty years.

The 1861 bond sale raised only $150 million, so a $500 million bond sale was authorized in February 1862. Since bonds were bought mostly by banks and brokers, Secretary Chase gave the responsibility of selling the bonds to one of the buyers, a banker named Jay Cooke. This was a roaring success; Cooke did it by running newspaper advertisements, using a network of 2,500 salesmen spread out across the country, and by writing editorials promoting the bonds. Some of the bonds had a face value as low as $50, making them affordable to private citizens, and Cooke declared that buying a bond was a patriotic act, that should be considered by anyone who wanted to preserve the Union. Because Cooke did so well, Congress authorized an $830 million bond issue in early 1865, and this time Cooke sold them all by the summer of the same year. Altogether, bond sales paid two-thirds of the $3.4 billion that the Civil War cost the Union government.

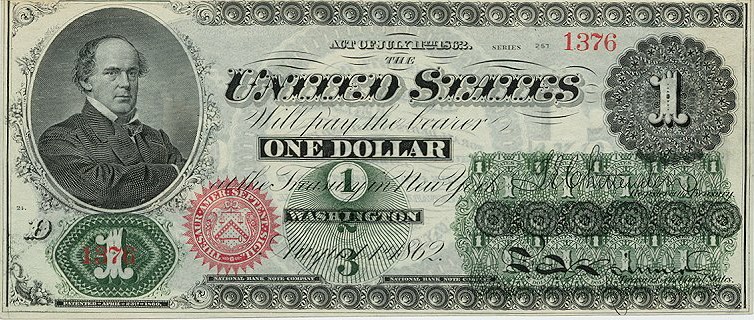

Finally, the Civil War saw the introduction of paper money as present-day Americans know it. At the beginning of the war, the money supply in circulation was $200 million worth of banknotes. Each state authorized a few banks to print the money, and from state to state the bills looked different, and were in different denominations. To reduce the confusion this understandably caused, Treasury Secretary Chase suggested that the federal government print $150 million worth of a new paper currency not backed by gold, but still considered an obligation of the USA. Printed on green paper, these "greenbacks" would be convertible into an equal amount of government bonds and considered legal tender for all public and private debts. After two months of heated deliberation, Congress approved his plan, through the Legal Tender Act of 1862. Ironically, the first dollar bills printed had Chase's picture on them (see below). Still, the new standard currency was soon accepted by both merchants and consumers, so in July 1862, Congress authorized another $150 million greenback issue, and urged that about 25% of the notes be issued in denominations of one to five dollars. Then it approved the third greenback issue, worth $150 million, in early 1863. By the end of the war, approximately $450 million worth of the new paper money was in circulation.

The Western Theater, 1862

The Confederate States of America began the war with most of the territory it wanted to have, and was now as strong as it was ever likely to be. This meant that the Southern strategy would be a defensive one: do not let the Yankees grab land in any seceded state, and stage limited offensives when possible to prevent Union offensives. In the Western Theater, the front line roughly followed the Missouri-Arkansas and Kentucky-Tennessee borders, except for the Confederate-controlled Ozarks and the mountains of southeast Kentucky. Albert Sidney Johnston, the commander on the front between the Cumberland Gap and the Mississippi, found himself defending a 600-mile line with 48,000 men. In most places the Confederate Army was spread too thin to do its job; Union General George Thomas showed this at the battle of Mill Springs (January 19, 1862), when his force of 4,400 men attacked the winter camp of a larger Confederate force in southern Kentucky, defeating the Rebels and chasing them all the way to Murfreesboro, TN.

One week after Mill Springs, General Grant launched his own offensive, trying to conquer Tennessee by first gaining control of the two rivers coming out of it, the Tennessee and the Cumberland. Each river was guarded by a single Confederate fort, Fort Henry on the Tennessee and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland. Fort Henry was easy; Northern gunboats blasted it into submission by the time Grant's troops arrived (February 6). Fort Donelson, however, was better protected, and Confederate batteries forced the gunboats to withdraw, leaving the Northern soldiers to advance first. Still, this reversal in tactics paid off. The two generals in command, Gideon Pillow and former War Secretary John Floyd, failed to break through the ring of troops that now surrounded the fort, so they handed over command to the third general in the fort, Simon Bolivar Buckner, and sneaked out before the Yankees could capture them. Buckner asked Grant for terms; he probably thought he could get off easily, because he and Grant had been friends in California before the war. Instead, Grant made it clear in the letter he sent back that he didn't follow any code of chivalry:

"Sir: Yours of this date proposing Armistice, and appointment of Commissioners, to settle terms of Capitulation is just received. No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works. "

Buckner knew he wasn't bluffing and surrendered the fort (February 16). The Union forces took more than 13,000 prisoners and captured 48 cannon. Still, Buckner and Grant managed to swap some jokes about the generals who ran away, while the surrender was taking place. Remember what I said about the Confederacy getting most of the good generals? Well, Grant already knew that Gideon Pillow wasn't one of them, and remarked that if he had captured Pillow, he would have released him again, because having him on the loose was one of the best things the Union had going for it!

The loss of Forts Henry and Donelson meant that the Confederate fort at Columbus, KY was vulnerable, so Johnston abandoned it in March. The way to Nashville was wide open, but Grant left the occupation of Tennessee's capital to another general, Don Carlos Buell, because his interest had shifted to Mississippi. Johnston was now just across the border at Corinth, MS, where the east-west Chattanooga to Memphis railroad met the north-south Columbus to Mobile line. Grant figured that if he and Buell could reach Corinth before Johnston assembled a large force there, they could easily capture this crucial railroad junction.

What they didn't know was that Johnston had been thinking the same thing; using the railroads, he brought in men from all four directions, and persuaded President Davis to send him the newest recruits. By the time Grant arrived at Shiloh, twenty miles to the north, Johnston had 44,699 men ready, nearly as many as Grant's 48,894, and 11,000 more showed up at Corinth after Johnston moved the main force to Shiloh. On April 6, Johnston launched an attack on Grant's inexperienced army that took it totally by surprise. A frontal assault drove the Union forces to the banks of the Tennessee River, but the Confederates weren't able to exploit the weak spots they punched in the Union line. In fact, neither side showed anything clever about its maneuvers; the battle of Shiloh was mainly the biggest round of bloodletting the war had seen to date. Late in the day Johnston was killed, and Beauregard assumed command of the Confederates. That night Buell arrived at Shiloh with his force of 17,918, and after a second day of fearsome fighting, Beauregard was forced to pull back to Corinth. The final score: 13,047 Union casualties, 10,699 Confederate casualties.

The battle of Shiloh is noteworthy because here is where we first see William Tecumseh Sherman, who would go on to become one of the most important Union generals. At Shiloh he kept the raw recruits in his division from fleeing by appearing everywhere along the front lines, eventually suffering two minor wounds and having three horses shot out from under him. As for Grant, Shiloh almost destroyed him; though the North technically won, it had suffered more men killed, wounded and missing than the South had. Northern newspapers pleaded with Lincoln to replace Grant with someone who didn't spend the lives of his soldiers so freely, and Lincoln, comparing Grant with the other generals he had at this time, replied, "I can't spare this man--he fights!"(12) Still, the carnage of Grant's "Pyrrhic victory" kept the Union Army from advancing to Corinth until the end of May.

West of the Mississippi, a Confederate invasion of Missouri from Arkansas was defeated in March (the battle of Pea Ridge, which pitted 12,000 Union troops against 12,500 Confederates and 3,500 Indians). More important, though, was the beginning of a Union campaign to conquer the entire Mississippi valley. Using both troops and ironclad gunboats (see the Monitor in the next section), General John Pope took New Madrid, Missouri, and went downstream to capture Island Number Ten, the next Confederate stronghold after Columbus, KY (March 3-April 8). This gave the North control over the entire Mississippi valley above Tennessee. On the other end of the river, Admiral David Farragut staged a brilliant naval maneuver, where a squadron blasted its way past the forts guarding the mouth of the Mississippi and forced the surrender of New Orleans (April 25). Now the South could no longer use the Mississippi for commerce, but the job wouldn't be finished until Union forces took the last Confederate strongholds on the river, at Vicksburg, MS and Port Hudson, LA. These were too strong for both Pope and Farragut, so it was time for the army of Grant and Buell to stop recuperating and get moving again.

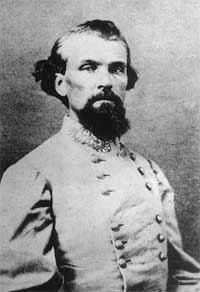

After taking Corinth, Grant and Buell separated again, each following a railroad; Grant headed west, while Buell went east. Of the two, Grant did better, but not well enough. On June 6 he reached Memphis, meaning he was back on the banks of the Mississippi, about 150 miles south of where he had crossed it in the fall of 1861. However, Vicksburg was too strong for him as well, and too far downstream. A siege would be necessary to take out Vicksburg, which would require reinforcements and shorter supply lines, so Grant had to pause for the time being. Additional attempts on Vicksburg, by Grant in November and Sherman in December, were likewise repulsed. As for Buell, his four divisions moved slowly, allowing his Confederate opponent, Nathan Bedford Forrest, to stage a raid on Murfreesboro that captured an entire garrison of 1,040 Union troops. This disrupted Buell's supply lines and halted his army before it got to Chattanooga.

Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Surprisingly, in view of what had been lost, the Confederacy gained the initiative in the Western Theater during the summer of 1862, and held it for the rest of the year. John Hunt Morgan, a dashing Confederate colonel from Kentucky, spent three weeks of July on a highly successful cavalry raid in his home state; he won four battles, killed, wounded or captured 1,200 Yankees, destroyed large amounts of Union materiel--and lost less than 100 men in the process. Even more ambitious was the campaign of General Braxton Bragg, who had just succeeded Beauregard as commander of the Army of Mississippi. When Bragg learned where Buell was going, he used the local railroad to quickly move his army from Tupelo to Chattanooga; then when Buell didn't show up at Chattanooga, he launched an invasion of Kentucky in August. He succeeded in conquering most of central Kentucky, including Lexington and Frankfort. At Frankfort, he installed the pro-Southern state government and its governor, Richard Hawes, but the inauguration was interrupted by an ambush from Buell's army, which had just returned from Louisville with reinforcements. Bragg withdrew, and Buell pursued, catching up with him at Perryville (October 8, 1862). The resulting battle of Perryville was a Shiloh-style bloodbath, again caused because neither side's generals showed much leadership (Buell was too timid in confronting Bragg, while Bragg didn't know how to follow up on his victories). 7,400 were killed here, of which 4,200 casualties were Northern, so Perryville can be called a tactical victory for the Confederates, but afterwards, Bragg promptly returned to Tennessee. He realized that he wasn't going to receive any reinforcements, so the odds would be against him if he continued the offensive. The pro-Confederate government went with Bragg; after that, it did not have a fixed base in Kentucky, but followed the Army of Tennessee for the rest of the war.

Buell did not pursue the Confederates, and two weeks later Lincoln, who was tired of Buell's vacillating behavior, sacked him and replaced him with General William Rosecrans. Rosecrans had just won two battles in northeastern Mississippi, at Iuka (September 19) and Corinth (October 3-4), and Lincoln hoped he would be aggressive enough to finish what Buell had started. He wasn't for long; first he spent two months in Nashville, getting more supplies and training for his force; then in the last week of December he finally moved out and attacked Bragg's force near Murfreesboro. The battle of Stones River (December 31-January 2) ended with Bragg leaving the field; Rosecrans was declared the winner, but he had suffered 13,249 casualties to Bragg's 10,266. Only gradually, as months went by and Rosecrans stayed in Murfreesboro, did it become clear how costly that victory had been. Back in Kentucky, 1862 ended with a "Christmas Raid" from Morgan's cavalry, which took 1,887 Union prisoners and destroyed $2 million worth of Federal property, while suffering only two killed and twenty-four wounded.

William Rosecrans.

We will finish this section with the conclusion of the New Mexico campaign. From Mesilla a force of 3,200 Confederates, led by General Henry Hopkins Sibley, advanced on Fort Craig, where 4,500 Union troops were now assembled. They did not take the fort, but won a victory at Valverde (February 21, 1862), which allowed the Confederates to bypass Fort Craig and occupy Albuquerque and Santa Fe in early March. By then reports of the battle of Valverde had reached Denver, prompting that territory to send reinforcements to the nearest fort still in Union hands, the appropriately named Fort Union. The Confederates continued north when they were done in Santa Fe, the Northern troops in Fort Union headed south to meet them, and on March 26 the two sides clashed in Glorieta Pass. Three battles were fought there in a three-day period; the Union forces won the first one, and while they technically lost the other two, they managed to destroy most of the Confederate supplies, forcing them to turn back anyhow. In April the Confederates abandoned Santa Fe and Albuquerque, fought an inconclusive skirmish with Union troops that tried to trap them at Peralta, and returned to Mesilla by a different route to avoid coming too close to Fort Craig.(13) May saw the Confederates abandon New Mexico altogether; in a letter to the father of a fallen soldier, Sibley wrote, "My dear sir, we beat the enemy where we encountered them. The famished country beat us." The Confederate Arizona Territory ceased to exist, and in 1863 the US government created another Arizona Territory, one that would eventually become the state of Arizona.

The Eastern Theater, 1862

While Grant was making crucial breakthroughs in the Western Theater, the Eastern Theater saw more stalemates. The US Army's main accomplishment was in recruiting, which over the course of 1861 raised the number of men in its ranks to 600,000, making it the largest army the western hemisphere had ever seen. McClellan's administrative skills had made the Army of the Potomac one of the best prepared armies, too. However, the Confederacy had also been busy recruiting, and now it had the second largest army in the western hemisphere, at 250,000; even more amazing, it was able to provide arms and uniforms for most of them, despite its lack of industry and the Union naval blockade. This was enough to make the Northern commanders (except for Grant) hesitant about going on the offensive. In fact, east of the Appalachians, except for capturing Cape Hatteras and Port Royal, the Union forces had made no progress at all. Lincoln noted that Union soldiers outnumbered the Confederates by at least 2 to 1 on most fronts, and thus couldn't understand why his generals were so unwilling to go on the offensive. At a Cabinet meeting attended by several of McClellan's division commanders, Lincoln remarked, "If General McClellan does not want to use the army, I would like to borrow it, provided I could see how it could be made to do something."(14)

In February, Lincoln got tired of hearing McClellan telling everyone why he couldn't fight now, and ordered him to move out. For his strategy, McClellan decided on a repeat of what Butler had tried the year before, a "Peninsular Campaign" that would have the army transported by sea down the coast to the Yorktown Peninsula; then he would attack Richmond from the east. This offered the advantage of a reduced marching distance; the army would only have to march sixty miles, compared with 120 if they followed the southbound road from Washington. Lincoln agreed to the plan, on condition that half of the Army of the Potomac be kept behind for the protection of Washington (Stonewall Jackson was too close for comfort, see below).

Before McClellan could move anything, he had to secure control over the waters of Chesapeake Bay, and this led to the war's most famous naval battle. Control was necessary because the Confederates had salvaged a US Navy frigate, the Merrimack, converted her into a new type of vessel, an ironclad warship, and re-christened her the Virginia. On March 8 the Virginia surprised the blockading Union ships by entering the mouth of the James River, where it destroyed two of them and disabled a third. However, the North had been working on an ironclad of its own, the Monitor, and sprang it on the scene the next morning. Whereas the Virginia resembled a haystack with ten cannon sticking out, the Monitor had two guns in a single turret, barely above the waterline; it was described as "a cheese box on a raft." The resulting battle ended in a draw; both ships bounced cannonballs off each other's armored sides without doing serious damage. However, this restored the blockade, and changed the history of naval warfare forever. In May the Confederates scuttled the Virginia to keep her out of Union hands, while a storm sank the Monitor in December. Now McClellan could proceed with his plans; by the end of March, a flotilla of 389 vessels had transported 121,500 soldiers, 14,592 animals, 1,200 wagons and 44 cannon to the tip of the Yorktown Peninsula.(15)

On the Confederate side, 1862 began with Stonewall Jackson back in the Shenandoah Valley. When we last saw him, he got his nickname from a successful defense, but now he showed that his real genius lay with offensive actions. To flush him out, Washington sent three armies with a combined total of 63,000 men into the valley, led by McDowell (from the north), former Speaker of the House Nathaniel Banks (from the east), and John C. Frémont (from the west). Thus, Jackson had a tough assignment--with no more than 8,500 men on his side, he had to hold the valley and prevent the Union armies in it from sending any reinforcements to McClellan. A firm believer in the maxim that battles are won by whoever "gets thar fustest with the mostest,"(16) Jackson moved first, hitting Banks' army so hard and fast that Banks thought he had a larger army than what was really the case. Then he picked up 8,000 reinforcements, and over the course of April and May, he charged up and down the valley, moving 646 miles in 48 days (his troops earned the nickname of "foot cavalry" for this) and striking each of the Union armies separately, before they could get together and overwhelm him with their numbers. He won all five of the battles he fought during this time, and his reputation grew to the point that when McClellan ran into trouble on his "Peninsular Campaign," Lincoln felt he could not spare him any of the 70,000 troops he had defending the nation's capital.

As for McClellan, his march up the peninsula went without a hitch, going from Fort Monroe to Yorktown to Williamsburg to the outskirts of Richmond. However, he wasn't in a hurry; it took him two months to do it, with half of that time spent besieging Yorktown. When the Confederate commander, Joseph E. Johnston, finally abandoned Yorktown, he later said he did it because "No one but McClellan could have hesitated to attack," meaning that no other general would have given him time to escape. McClellan hesitated again when he came upon a Confederate fort at Centreville; he wondered why such a well-armed place did not have any troops, until a second look revealed that the artillery pieces were painted logs (nicknamed "Quaker guns," after the nonviolent Christian sect).

On May 31, when McClellan was only nine miles from Richmond, Johnston launched a desperate counterattack. This was the battle of Seven Pines, which caused McClellan to halt his advance; he thought he might do better after the roads dried out and he got the reinforcements he asked for. However, Johnston was wounded on the second day of the battle, and Jefferson Davis replaced him with Robert E. Lee. For the rest of the war, Lee would be the top Confederate general in Virginia; his military skills and magnetic personality would soon make him a legend, and the most admired officer on either side.

Robert E. Lee, from a picture taken shortly after the war ended.

At the moment, however, McClellan had 100,000 men to Lee's 50,000, so an outside observer would have expected to see the fall of Richmond next. To keep that from happening, Lee concentrated his men on the east side of Richmond by thinning out those on the other sides, and had the ones he left on the north, south and west dig in. Then he called in Jackson from the "Valley Campaign," and deployed him on the left wing of his eastward-facing force, giving him a 3:2 advantage over McClellan's right wing. Another colorful Confederate general, J. E. B. "Jeb" Stuart, led a bold reconnaissance mission that went completely around the Union Army; he discovered that the right wing was indeed the weakest link in the Union chain, because it was isolated from the other units by the rain-swollen Chickahominy River. The resulting battle, known as the battle of Seven Days (June 25-July 1, 1862) was a series of Confederate attacks that took McClellan by surprise (McClellan, like other Union leaders, thought Jackson was still in the Shenandoah Valley), and eventually broke though both the Union right and center. The cost was very heavy for Lee (he lost 20,614 men, compared with 15,849 for McClellan), but he saved Richmond and forced McClellan to flee back down the peninsula.

Lincoln blamed the failure of the Peninsular Campaign on McClellan, because he had not tried hard enough to take Richmond, while McClellan blamed Washington for not sending him reinforcements. To save the situation for the North, Lincoln decided he would have to use the Army of the Potomac for offensive operations, instead of just defense. He called in John Pope, one of his more successful generals from the west, put him in charge of the army, and ordered him to go for Richmond; then he ordered McClellan to launch a second offensive from the east, so that Pope wouldn't have to face Lee and Jackson alone. McClellan refused to do it, protesting that he was outnumbered, so Lincoln gave him a new set of orders: return to the Potomac and join forces with Pope.

This strategy might have worked if Northern armies moved as fast as Southern ones, and as we saw, McClellan did anything but that. Lee knew this, and wasn't going to miss an opportunity to destroy Pope before McClellan arrived, so he rushed north to deal with the new threat to Virginia. Jackson got there first, engaging and defeating the unit led by Banks at the battle of Cedar Mountain (August 9). Next Jackson went on a long, curved path that took him around the right flank of Pope's army, and cut off its supply lines by capturing Manassas. Pope turned around to attack, and thought he won; he sent a telegram to Washington claiming he had beaten Jackson, only to find Lee arriving with the main Confederate army the next day! This was the second battle of Bull Run (August 28-30), and it ended the same way as the first one--with a Confederate victory. Again, the Union forces fought bravely at first, but their morale faltered before that of the Confederates did, and in the end they pulled themselves off the battlefield. This time they broke through a trap Lee tried to set for them at Chantilly, five miles to the northeast of Bull Run; after that, they managed a retreat to Washington that was more disciplined than the one of 1861, but just as embarrassing. The Army of the Potomac was back to where it had started, its only accomplishment being a growing list of casualties and discredited generals.

The Bull Run rematch gave Lee the idea that this would be a good time to invade the North. He had seen the damage inflicted on his beloved Virginia, and felt that the more fighting he could wage on Union territory, the better. Finally, there was the chance that a campaign north of the Potomac would bring Maryland back into the Southern camp (Braxton Bragg was trying the same thing with Kentucky at that moment), and if he caused enough trouble in Maryland and Pennsylvania, it might even result in the Democrats winning the 1862 congressional elections; that might force Lincoln to negotiate an early end to the war. Accordingly, as soon as his men had rested a bit from Bull Run, Lee began marching them north on the "Maryland Campaign." In Maryland they captured Frederick on September 7, and this caused a panic in Washington. Lincoln, who had just dismissed Pope, reluctantly transferred command of the Army of the Potomac to McClellan, told him to do what he could to restore its morale, and then go and get Lee. After his performance near Richmond, McClellan was hardly an inspiring leader, but Lincoln didn't have anyone else for that job.

From Frederick, Lee split up his army, sending Jackson west to seize the Union arsenal at Harper's Ferry (the same one that John Brown had raided three years earlier). Another general, James Longstreet, would lead most of the army to Hagerstown, while Jeb Stuart would guard the rear at South Mountain. It was a risky strategy, because Lee's "Army of Northern Virginia" had dwindled from 55,000 men to 45,000 in just ten days. Some men had refused to cross over into Maryland because they didn't believe the purpose of the war was to invade Union territory; others became sick from eating unripe "green corn" from the local farms, or had their bare feet bloodied on paved northern roads. What's more, the local population did not give the Confederates the support they expected; this wasn't occupied Baltimore, after all. Worst of all, when they got to Frederick, Union soldiers found a copy of Lee's orders, which showed where each of the Confederate Army's units was going; of course this was passed on to McClellan. Afterwards McClellan continued to be overly cautious (he thought Lee had 120,000 troops vs. his 87,000), but when he caught up with Lee at Sharpsburg, Lee was the one at a disadvantage: he was surprised, outnumbered, and caught while Jackson was away at Harper's Ferry.

The battle that followed on September 17, 1862 is called Antietam (after Antietam Creek) by Northerners, and Sharpsburg by Southerners. Whatever the name, it was the bloodiest single day of the war, and the bloodiest day in US history; 12,401 Union soldiers and 10,316 Confederate soldiers fell. The North claimed victory afterwards; though Lee had defended well against McClellan's poorly coordinated assaults, he lost so many men that he immediately called off the Maryland Campaign. On the other hand, McClellan had not committed his entire force, allowing the Confederates at Harper's Ferry to rush back in time to save the day for Lee, and then after the battle Lee successfully withdrew across the Potomac. Jeb Stuart stayed a bit longer, though, leading a brief raid in October that got as far north as Chambersburg, PA.

Union soldiers at Antietam.

The Copperheads and Lincoln's Masterpiece

By now the war had been going on for a year and a half. The struggle had been tougher, and far more costly and bloody, than either side had expected. The Union had recovered much of Tennessee and the Mississippi valley, but on the Virginia front, the score was: "CSA=4, USA=0." In place of the easy enthusiasm of 1861, participants on both sides were now grimly determined to stay in the struggle until it was over, so that those who had fallen will not have died in vain. Because volunteer soldiers were getting harder to find, both sides introduced conscription. This was just one example of how the government was beginning to meddle in the lives of ordinary people; other examples included the economic reforms described previously, and a suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. Of course all this regulation would be outdone by the "New Deal" and the welfare state of our own era (see the next chapter), but still Lincoln's acts would have been unthinkable to any prewar government; we saw how former President Van Buren did not try to rescue the economy when it crashed under his watch.

The longer wars last, the less popular they are. Lincoln had to keep this in mind because opposition to his administration gained strength every time a battle was lost.(17) Most of it came from the Democratic Party, which now had its strongest faction caught in the Confederacy. Among Northern Democrats, some stayed loyal to the Union after the war broke out, but the party included a disturbing number of racists, Southern sympathizers, draft-dodgers, pacifists who didn't think the war was justified, and anyone who was bitter at seeing the country under Republican rule. They came to be known as "Copperheads" because they wore copper Liberty head pennies as badges, but for most Northerners the other kind of copperhead--a poisonous snake that likes to hide, ready to strike if discovered--seemed more appropriate. One Copperhead, New York City Mayor Fernando Wood, wanted his city to secede and become a free port, so it would not lose its cotton trade with the South. Another was Edward G. Roddy, editor of the Pennsylvania newspaper Genius of Liberty; Roddy saw blacks as an inferior race, and while he had supported the war when it started, he blamed Abolitionists for prolonging it and soon called Lincoln both a tyrant and a dunce; by 1864 he was demanding peace at any price. Still others tried to persuade Union soldiers to desert, helped Confederate prisoners of war to escape, and plotted the violent overthrow of state governments.

The leader of the Copperheads was Clement Vallandigham, an Ohio congressman who coined the faction's slogan: "To maintain the Constitution as it is, and to restore the Union as it was." Vallandigham opposed every effort in his state to support the war, especially the draft. In May 1863 he was arrested for making an openly seditious speech; this generated such a fiery controversy that Lincoln decided Vallandigham was too much trouble, even in a jail cell, and ordered him deported to the Confederacy. Not long after that, Vallandigham walked across no man's land in Tennessee and told an astonished private, "I surrender myself to you as a prisoner of war." Most Confederates snickered; having no use for him, President Davis ordered Vallandigham sent to Wilmington, NC, to be guarded as an "alien enemy." From there he escaped to Bermuda in a blockade runner, traveled to Canada, and campaigned in absentia as a candidate for governor of Ohio. Democrats demanded that Lincoln allow Vallandigham to return, and Lincoln asked, "Must I shoot some simple-minded soldier boy who deserts, and not touch a hair of a wily agitator who induces him to desert?" Vallandigham lost the election, and in 1864 he sneaked back into the United States, wearing a pillow stuffed into his pants and vest and fake whiskers on his face. The disguise didn't fool the authorities, but this time Lincoln ignored him.

Incidentally, Vallandigham suffered a fate worse than even he deserved; it was only appropriate for someone trying to win a Darwin award. After the war he tried running for Congress as an anti-Reconstruction candidate, lost again, and went back to the career he had before entering politics, as a trial lawyer. In 1871 he was defending a man accused of murder in a barroom brawl, and his argument was that the dead man's pistol had gone off accidentally. To demonstrate what could have happened, Vallandigham took a pistol, put it in his pocket, and got down on his knees. He didn't know the gun was loaded, and shot himself while trying to stand up and draw the pistol at the same time. He died of his wound the next day; the good news was that he had proved his point, so the defendant was acquitted.

Early in this chapter we noted that Lincoln put the slavery question on the back burner, because unlike most Abolitionists, he felt the war was about saving the United States, not about doing away with slavery. As time went on, however, Abolitionist leaders like Frederick Douglass put pressure on him to abolish slavery anyway. Republicans in Congress also applied pressure, by voting to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia and all territories, now that Southern legislators were no longer there to stop them. When Horace Greeley wrote Lincoln a letter demanding abolition, calling it the "Prayer of Twenty Millions," the president replied with a letter of his own which showed where his priorities were: "If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. . . . I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free."

The ink was barely dry on that letter before Lincoln decided that it was time to act on his personal wishes. On September 22, 1862 (five days after Antietam), he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that as of January 1, 1863, all three million slaves in the seceded states would "henceforward and forever, be free." Although this was one of the most important acts of any president, we must remember that the Emancipation Proclamation was mainly a political gesture. In the short run, it did not free a single slave, because it only applied to those states that were currently in rebellion. It did not apply to slaves in any states that stayed with the Union, like Missouri; nor did it apply to Tennessee, or to the parts of Virginia and Louisiana that had been taken back by Union forces. It would not have even applied to any Rebel state that rejoined the Union before the last day of 1862 (fortunately for the slaves, no state did that). Lincoln felt that he did not have the right to take away the property of law-abiding citizens, only the property of rebels. Thus, the Emancipation Proclamation was no more likely to be enforced than an order sent to Adolf Hitler in 1943, demanding that he free every Jew in Germany. For the slaves, real emancipation would come in 1865, with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

What made the Emancipation Proclamation a success was that it claimed the moral high ground for the North. Now Lincoln had an argument that outweighed the Confederate argument that the seceding states were only exercising their voluntary right to leave the Union that they had voted to join, three quarters of a century earlier. Britain and France had abolished slavery in their countries already (see Chapter 7 of my African history to find out how they stamped out the slave trade), so now world opinion switched from favoring the underdog South to the liberating North. English workers successfully persuaded their government to stop building ships for the Confederate Navy. Russia's Tsar Alexander II had just freed his own serfs in 1861, and he sent Russian warships on a friendly visit to New York and San Francisco, to show he approved of Lincoln's action.(18)

Emancipation also answered the question of what to do about escaped slaves. Since the war began, many slaves had escaped, gone north and joined the Union Army. Should they be returned to their masters? Were the Fugitive Slave Act and the Dred Scott Decision still valid? General Benjamin Butler said no; they were "contraband of war," and he would not return his enemy's property. After the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln had no trouble agreeing. Over the course of the war, the Union Army would recruit 179,895 black soldiers, of which a third would be killed in battle. They were enrolled in special "colored" units, and faced discrimination, enduring inferior pay and living conditions compared with white soldiers, but they proved to be more motivated than Confederate black soldiers(19) or the white soldiers on both sides, because they were fighting for their freedom. Thus, for many blacks, the struggle for civil rights began in the same place where the struggle against slavery ended--in the armed forces.

Despite his political victory, Lincoln still needed somebody who could win a military victory for him; in Virginia this meant getting rid of that chronic staller, McClellan. McClellan had been popular among his men because he didn't risk their lives much, but at Antietam he failed to do even that. For the way he handled the battle, and for letting Lee escape back into Virginia, Lincoln relieved him of command in November, replacing him with General Ambrose Burnside.(20) Alas, Burnside proved to be even worse than his predecessors. At Antietam he had sent company after company of men across a narrow bridge, and Confederate sharpshooters picked them off; the really sad part was that the water under the bridge was only waist deep, so if any reconnaissance had been done, the men could have waded through the creek without coming near the deadly bridge.

For his campaign, Burnside would outwit Lee by sneaking across the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg, and then march on Richmond before Lee found out what he was up to. The problem in his plan was that when Burnside got to Fredericksburg, he didn't find the pontoon bridges he expected for crossing the Rappahannock, and Lee was in a well-prepared defensive position on the other side. He crossed the river anyway, using boats when Confederate snipers prevented the building of the bridges. What followed was more butchery than battle; on December 13 Burnside had his army charge Lee's position, one brigade at a time. Every charge failed, and in the end Burnside was only able to leave because Lee agreed to a truce the next day, allowing the Union Army to retreat across the river. Northern casualties had been 12,653 men, lost for no gain at all, compared with 5,309 Southern losses. Even Lee felt sorry for the Yankees; at one point during the battle he said, "It is well that war is so terrible, or we should grow too fond of it." A Southern newspaper, the Charleston Mercury, praised Lee's victory by writing, "General Lee knows his business and the army has yet known no such word as fail." One month later Burnside tried to restore Northern morale by crossing the Rappahannock at a different location, but got nowhere due to bad weather (the so-called "Mud March"). Lincoln stopped it by replacing Burnside with General Joseph Hooker on January 26.

The Western Theater, 1863

The Union Army's plan for 1863 was simple: go for the objectives it had failed to achieve in 1862. In the west, General Grant would take Vicksburg, General Rosecrans would take Chattanooga, and General Banks would march from New Orleans to take Port Hudson. If all three of these missions succeeded, the war west of the Appalachians would be finished, aside from mopping up operations, and Georgia would be open to invasion.

Easier said than done, though. In the first three months of 1863, Rosecrans and Banks didn't move at all, and while Grant made four attempts on Vicksburg, all of them failed. The only good news concerning these efforts was a successful raid Grant sent out to distract the Confederates. Led by Colonel Benjamin Grierson, this involved 1,700 cavalrymen going from La Grange, Tennessee to Baton Rouge, Louisiana; on the way they killed 100 enemy soldiers, captured 500 more, destroyed 60 miles of railroad and 3,000 small arms, set fire to tons of Confederate supplies--and lost only twenty-four men.

Because Vicksburg was so well defended on the north and west sides, Grant decided to try striking from the south and east. Doing this would require traveling without a supply line, meaning that Grant would only have two weeks to win a victory. In April he went ahead and did this, marching past Vicksburg on the west bank of the Mississippi River; Admiral David Porter's river fleet provided protection for the troops during this crucial period. At a point thirty miles south of Vicksburg, Grant used Porter's boats to cross the river, and entered the state of Mississippi. From there he took Jackson, the state capital, a move which put his army between Vicksburg and any reinforcements assigned to it. Then he returned to the river, twice defeated Vicksburg's commander, General John Pemberton, when he tried to break out of the tightening circle, captured the bluffs north of Vicksburg, and reestablished the supply line to his army. He still hadn't taken Vicksburg, but having completely surrounded it, he could starve it out at his leisure. Over the course of May and June its defenders were forced to take shelter in caves and eat mules, dogs, and even rats, if the stories about the siege are true.

On July 4, 1863, six weeks after the siege began, Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg; Grant took 30,000 soldiers prisoner and seized 172 cannon and 60,000 muskets. Meanwhile to the south, Banks put Port Hudson under siege on May 27. This battle is noteworthy because it was the first time that the United States used black soldiers in combat on a large scale. Among those who proved their courage here was Color Sergeant Anselmas Planciancois of the 1st Louisiana Native Guards. Given the assignment of carrying his regiment's flag, Placiancois made this promise: "Colonel, I will bring back the colors with honor or report to God the reason why." He did both; mortally wounded in the battle, his final act was to hold the flag against his breast. Then on July 9, the 6,000-man garrison at Port Hudson surrendered, after hearing what had happened at Vicksburg. The entire Mississippi valley was back under Union control, and the Confederacy had been split in two; Lincoln joyfully reported to Congress that "The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea!"

The Confederate response to Vicksburg was to have John Hunt Morgan go on another raid; this one, the so-called "Ohio Raid," was more dramatic than the raids of 1862, but less rewarding. Leading 2,500 men through the middle of Kentucky, Morgan didn't stop when he got to the Ohio River, but crossed over into Indiana, turned east, entered Ohio by way of Cincinnati's suburbs, and continued on until he reached the Ohio-West Virginia border, where Union troops were strong enough to handle the raiders. Morgan finally surrendered near New Lisbon, OH on July 26; except for the raid on St. Albans, Vermont mentioned in the previous chapter, this was the northernmost spot reached by any Confederate force. He escaped in November, but was killed ten months later in a battle at Greenville, Tennessee.

On the Tennessee front, Rosecrans waited so long to go for a rematch against Bragg that he started to look like a second McClellan; he didn't move out until the second half of June. Over the course of the summer he pushed Bragg back from Murfreesboro to Chattanooga, and took that city in early September. Chattanooga had been an important Union objective for the past year and a half, and its capture went a long way toward clearing the Confederates out of eastern Tennessee. This encouraged Rosecrans to announce that he was going on to Atlanta; instead, he ran into Bragg's army at Chickamauga Station, just a few miles southeast of Chattanooga. Jefferson Davis was so concerned about the Western Theater collapsing that he ordered all available reinforcements sent to Bragg; he even had Lee send 11,000 troops from the Army of Northern Virginia, including General James Longstreet. Consequently Bragg now had 58,000 men vs. the 54,000 men under Rosecrans (one of the few times that a Confederate army was larger than a Union one). Rosecrans sensed that things were no longer going his way in time to pull his widely scattered force together, but neither he nor Bragg showed much confidence or resourcefulness. On the first day of the battle of Chickamauga (September 19), Rosecrans felt he had to keep shifting his divisions around, since they were arranged in a disorderly line. On the second day this movement caused a gap in the line, right in front of Longstreet and his veterans; Longstreet charged in and sent the entire right wing of the Union Army (including Rosecrans himself) fleeing back to Chattanooga, as fast as their feet would let them. The general commanding the Union left, George Thomas, stood his ground, earning him the nickname "Rock of Chickamauga" and keeping the battle from becoming a total disaster, but in the end he had to withdraw to Chattanooga, too. Rosecrans ending up losing 16,170 casualties; Bragg lost 18,454.

Now it was Lincoln's turn to panic. The Army of the Cumberland was under siege in Chattanooga, and because the Confederates controlled the supply lines, food and firewood (a crucial concern, now that fall had arrived) were running out. Fortunately his actions were just what was needed to save the day. Because the battles of Vicksburg and Gettysburg (see the next section) were over, he dispatched two corps from the Army of the Potomac as reinforcements, and a third, the one led by General Sherman, from the Mississippi valley. Most important, he put Grant in charge of the entire Western Theater. Grant removed Rosecrans from command of the Army of the Cumberland, replacing him with Thomas, and opened up supply lines to Chattanooga. Bragg's force occupied two high points nearby, Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, and when Grant struck back, he gave his troops orders to take only the base of those hills, because it seemed impossible to scale the high points under fire. Instead, the troops went on without orders and performed the spectacular feat of taking both positions in three days (November 23-25). Lifting the siege of Chattanooga ended up costing Grant 5,824 troops, but unlike Bragg's 6,667 casualties, he could replace them. Bragg withdrew to Dalton, GA, and soon resigned, having failed to follow up on the Confederacy's only victory in the Western Theater for 1863.

The Eastern Theater, 1863

Like McClellan, "Fighting Joe" Hooker was a good organizer; in three months he built the Army of the Potomac up to 134,000 men, and restored its morale. The latter was done by introducing programs to improve the health and welfare of the troops, and by his own boundless optimism. About the army he said, "I have the finest army on the planet. I have the finest army the sun ever shone on. . . . If the enemy does not run, God help them. May God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none." About himself, he had no doubt that he was the one to bring down Lee, and seemed to view himself as another Caesar or Napoleon, because he was overheard saying that in wartime a dictator could better serve the country than a president. When Lincoln got wind of this, he responded with a letter that scolded Hooker like a wayward child. First he praised Hooker for his previous accomplishments, and then he wrote, "I have heard, in such way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain success can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship. . . . And now, beware of rashness. Beware of rashness, but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories."

April is the traditional time for military campaigns to begin, so when April rolled around in 1863 Hooker felt it was time for actions to match his words. His plan was to have General John Sedgwick cause a diversion by making a second attempt on Fredericksburg, and while he was doing that, Hooker would take the main part of the army across the Rappahannock River at another point, turn east, and inflict a crushing blow on Lee's left flank. This would mean splitting the army in two, something which always led to trouble when other Union Generals tried it, but because his force outnumbered Lee's by two to one, Hooker felt he could pull it off.

Lee ruined Hooker's plan by splitting up his own army: one part under General Jubal Early would stay behind and hold Fredericksburg, while Lee would take the second part west to engage Hooker directly. Hooker suddenly lost his nerve when he learned that Lee was coming to attack him (Hooker later said about that day, "For the first time, I lost faith in Hooker."). Not wanting to fight in a heavily forested area (the so-called "Wilderness"), which would make his cannon useless, Hooker advanced to Chancellorsville, ten miles west of Fredericksburg, and chose to go on the defensive. Before Lee arrived he split his army again, sending Stonewall Jackson with part of it into the Wilderness. Thus, after the main battle between Lee and Hooker began on May 2, Jackson's men exploded from the forest on Hooker's unprotected right flank, screaming rebel yells. This surprise attack shattered an entire Union corps, but because it came in the late afternoon, darkness fell before Jackson's unit could do any more. At the peak of the fighting, Hooker was stunned when a Confederate cannonball hit the wooden pillar he was leaning on at his headquarters. He refused to turn over command to a subordinate while recovering from this minor injury, so the Union troops were poorly led for the rest of the battle; he failed to call in reinforcements when he could, for instance. The Union army began to retreat across the Rappahannock, and Lee heard that in his rear, Sedgwick had taken Fredericksburg. He rushed back on May 4 & 5 to restore the situation for Early, and when that was done, returned his tired men to Chancellorsville, only to find that Hooker was no longer there; the Army of the Potomac was in full retreat.

Chancellorsville was Lee's boldest gamble and his greatest victory, a textbook example of how to defeat a larger force by taking the initiative. But both sides paid a terrible price for it: 17,197 Union casualties vs. 12,764 Confederate casualties. Among the latter was Stonewall Jackson, who fell victim to "friendly fire." On the night of May 2, he went on a reconnaissance mission and was shot by some North Carolina soldiers who didn't recognize him. Because it was dark, and the usual battletime confusion was going on, Jackson didn't receive immediate care; in fact he was dropped from a stretcher while they were evacuating him. The doctors tried to save him by amputating a mangled arm, but eight days later he died anyway. This inspired Lee to say that while Jackson had lost his left arm, he had lost his right arm. The Confederate Army would keep on fighting after Chancellorsville, but without Jackson's talent for flanking maneuvers it would be far less flexible.