| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 2: Colonial America, Part 3

1607 to 1783

This chapter is divided into three parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| Jamestown | |

| The Search for a Northwest Passage (concluded) | |

| The Founding of New France | |

| They Came on the Mayflower | |

| New Netherland | |

| Colonization: The Second Generation | |

| New Amsterdam Becomes New York | |

| Carolina | |

| The Last French Explorers |

Part II

| Colonial Growing Pains, Part 1 | |

| The Founding of Pennsylvania | |

| The Importance of the Religious Element | |

| The Lone Star Colony | |

| Colonial Growing Pains, Part 2 | |

| Sideshows to European Wars | |

| The French and Indian War | |

| Pontiac's Rebellion | |

| Causes of the American Revolution |

Part III

The California Missions

Though the Atlantic coast was America's main action center in the eighteenth century, there were interesting events on the Pacific coast as well. Very little was known about this region, because exploration had ceased by 1600, and most of the north Pacific was a blank on world maps.(37) The nation that led the way in exploring the Pacific Northwest was one that so far has not played a part in this narrative--Russia.

The Russians started with the northwest corner of the continent, because they had conquered Siberia in the seventeenth century, and wanted to know how far east it went. It was Vitus Bering, a Danish ship captain hired by the Russians, who finally reached the end of the landmass. In 1728 he sailed through the Bering Strait into the Arctic Ocean, thereby proving that there was no land connection between Siberia and North America. Then he went to St. Petersburg to get backing for a second, larger expedition, which was finally ready to cast off from Petropavlovsk (a town on the Kamchatka peninsula he had founded the year before) in 1741. Looking to see what was on the other side of the strait, Bering discovered Alaska, sighting the south coast of the mainland near Mt. Saint Elias (the second tallest mountain in both the US and Canada), and then proceeded to map the Aleutian Islands on the trip back. He didn't make it, though; after going through storms and fog, they were wrecked on an island (now called Bering Island) near Kamchatka, where Bering and 28 crew members died of scurvy and exposure. There was one carpenter among the survivors, and he managed to build a boat that got 46 members of the expedition back to Kamchatka in 1742. Soon Russian fur traders followed in Bering's tracks, attracted to Alaska by the same resource that had attracted the French to Canada. However, they did not establish any permanent settlements until 1783.

Rumors of Russian activity encouraged Spain to take an interest in California. For two hundred years they ignored the place, because it didn't seem to be worth the trouble. The winds and currents on the California coast travel from north to south, making it difficult to sail there from Mexico, and because sixteenth-century explorers had failed to discover San Francisco Bay, they had trouble finding a safe place for their ships. Spain's lack of knowledge shows in the maps that were published for two hundred years; they showed California as a long, skinny island, though nobody had proven it by going around the whole thing. The Baja (lower) California peninsula was accessible from ports like Acapulco, but it was also an uninviting desert, so while Spanish missionaries began going there in the late seventeenth century, efforts to build settlements and convert the tribes to Christianity were never more than halfhearted.

That changed when a particularly zealous Franciscan missionary, Father Junipero Serra, arrived in Baja California in 1767. As with Texas, missionaries would lead the way in civilizing California. In 1769 he headed north with the local governor, Gaspar de Portolà, and a party of soldiers and priests, to settle what was then called New (Nueva) California. They established both a mission and a presidio (fort) at San Diego de Alcalá, and later in the same year, a second mission went up at Monterey. Before his death in 1784, Serra founded seven more missions, stretching from San Diego to Santa Clara, 465 miles to the north.

The missions served not only as churches, but also as the center of a new way of life, for once they learned the tenets of Christianity, the Indians were expected to learn how to become subjects of the Spanish crown. It does not appear that all of the conversions were voluntary; Indians were forced to work as farm laborers at the missions while their education was going on, and afterwards they were placed in small farming settlements, known as pueblos (no connection to the Pueblo Indians of Chapter 1, or the communities they built by that name).

Most of the inhabitants of the pueblos, however, were poor settlers from Mexico that had been encouraged to move to California. They were there because a land route had been found, avoiding the contrary winds and currents. In Tubac, Arizona, a soldier named Juan Bautista de Anza learned that an Indian in the neighborhood had fled from one of the California missions, San Gabriel Arcángel, and using the Indian as a guide, he blazed a trail to the mission; then for good measure he marched up the coast as far as Monterey before returning to Arizona (1774). A year and a half later, de Anza proved that he wasn't telling tall tales by leading a group of colonists to San Gabriel Arcángel and Monterey. By this time San Francisco Bay had also been discovered. The bay was first sighted, but not entered, by Gaspar de Portolà in 1769, and Juan de Ayala explored the bay in 1775; Spain responded by building a presidio at the Golden Gate in 1776, thus founding the city of San Francisco. These expeditions proved to any skeptics that California was part of the mainland, not an island. A few miles from San Gabriel Arcángel, the city of Los Angeles was founded in 1781.

No attempt was made at this stage to colonize the lands north of San Francisco, but Spain sent explorers. In 1774 a Spanish ship, the Santiago, under the command of Juan José Pérez Hernández, explored the coast of Vancouver Island. In 1775 two Spanish ships went up the coast, commanded by Bruno de Hezeta and Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra. Hezeta was considered commander of the expedition because of superior ancestry (he was born in Spain while Bodega y Quadra was born in Lima, Peru), but in the long run, Bodega y Quadra was the more competent officer. They sailed together for four months, getting as far Point Grenville, WA. There some sailors went ashore to get fresh water, only to be massacred by 300 Indians attacking from the woods. The horrified crew members on the ships tried firing upon the Indians, but they were out of range. After that shocking encounter, Hezeta returned to Mexico, but Bodega y Quadra insisted on completing the original mission--locate the Russians. He kept sailing until he reached latitude 59o N., still without finding any Russians, and then he turned his ship around. On the way back, he landed once so that he could claim the whole coast he had explored for Spain. However, it appears that both the 1774 and 1775 expeditions did not find Puget Sound or the Strait of Juan de Fuca, though they are near Vancouver Island. A follow-up expedition in 1779, led by Bodega y Quadra and Ignacio de Arteaga, mapped the coast as far as 58o 30' before bad weather forced it to turn back. All of these expeditions made it clear that there was no major Russian presence in the Pacific Northwest (yet).

By this time, other nations besides Russia and Spain were active in the Pacific. In the sixteenth century, Spain had been able to claim most of the Pacific for herself, but then in the seventeenth century, the Dutch took over commerce with the Far East, managing it from their bases in Indonesia. And that wasn't all; in the 1760s France claimed Tahiti, and Britain's Captain James Cook entered the south Pacific. Within a few years (1778-79), Cook would head to the north Pacific, discover Hawaii, and map North America's Pacific coast, all the way from California to the Aleutian Islands. He was less successful, though, when it came to penetrating the ice of the Bering Strait, and like his predecessors, he missed the Strait of Juan de Fuca. The part of this trip that made a difference was the month-long stop at Nootka Sound, on Vancouver Island. While Cook and his crew were repairing their ship, the Resolution, they also met the Nootka Indians, and by trading with them, obtained a cargo of furs. The sea otter pelts from that cargo were later sold in Macao for more than $10,000, and when news of that handsome profit reached British and American fur companies, it brought as many as a dozen ships a year to the previously unvisited coast of British Columbia.

The arrival of all these interlopers in a part of the world Spain had long considered hers meant that the time had come to do something with those claims. If this story had happened today, we would probably tell the Spaniards, "Use it or lose it."

"The Shot Heard 'Round the World"

We're now ready to get into the story of the American Revolution. Before we begin, it will help to explain two things that make studying the American Revolution difficult. The first is that a number of myths and legends have embraced this period of history, to the point that they overshadow the facts. I have pointed out a few already (e.g., Pocahontas in footnote #1), and you have probably heard others. In case you haven't heard, George Washington didn't chop down a cherry tree when he was a boy, and it is doubtful that a seamstress named Betsy Ross made the first American flag, since that story was first told by her descendants, a hundred years later. Most books, movies and TV shows about the Revolution portray the Patriots as the heroes (history is written by the winners, after all!), but it wasn't so obvious in the 1770s and early 1780s. Across the colonies, sentiment wasn't overwhelmingly in favor of the Patriots. John Adams felt that one third of the civilian population backed the Patriots, one third were pro-British ("Tories"), and one third went with whichever side had troops nearby. And whereas the American Civil War has been described as a conflict that pitted brother against brother, such fighting within families was even more likely during the Revolution, because every community had Loyalist and Patriot factions. If today's newspapers and news networks had been around back then, most of them (maybe even FOX News) would have routinely published polls showing a lack of public support for the war, and there would have been editorials/commentaries calling for an "exit strategy," because the war was unwinnable. Aren't you glad now that the minority prevailed?

The other factor is that warfare has changed so much since the eighteenth century. The largest armies never exceeded 30,000-40,000 men, and in terms of death and destruction, the American Revolution was a smaller war than most of those the United States has fought since then. Also, the Patriots didn't win as often as you might think. The only two victories they won against a large group of British regulars were the battles of Saratoga and Yorktown. And while George Washington has been portrayed as larger than life, for faithfully leading the Continental Army through the whole conflict, when it came to strategy, he wasn't an Alexander or a Napoleon (fortunately he didn't have their delusions of grandeur, either). Of the nine battles that Washington fought in, he won three and lost six; his best qualities were his personal courage and a determination to not give up until he finally won a victory that mattered. There was a Patriot general with a better scorecard--Benedict Arnold--and we'll see later why he isn't considered a hero today.

But on with the narrative. By early 1775 the British realized they had a rebellion on their hands, but it would quickly fall apart if they crushed the main center of Patriot activity in Massachusetts. That's probably what General Thomas Gage, now the commander of the British troops in Boston, was thinking when he received new orders from London. Those orders called for him to arrest members of the former Massachusetts Assembly, who were meeting illegally outside of Boston, and to march to Concord, a town twenty miles away, to capture the weapons the Patriots were stockpiling there. In the past he would have requested assistance from the Massachusetts militia (called the "Minutemen" because they claimed they could be ready to fight on a minute's notice), but now the militia were the other side's first line of defense, so his Redcoats would have to go alone. They left Boston on April 19, and fought their first battle at Lexington, where they knocked the Minutemen out of the way and continued on. At Concord, however, they met disaster, because the Patriots had been warned that the British were coming.(38) Here the militia had successfully copied the skirmishing techniques of the Indians, and shot at the British column from behind trees, hedges and buildings. Soon the British were forced to retreat in disorder, and only made it back to Boston because reinforcements came out to escort them on the last leg of the journey. The final score was an American victory; the British lost more than 270 casualties, while the Patriots lost less than 100. In 1837 Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote the Concord Hymn to commemorate the battle of Concord, which happened near his family's home, and used this stanza to emphasize the importance of that battle on world history:

"By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April's breeze unfurled;

Here once the embattled farmers stood;

And fired the shot heard 'round the world."

To the south, Virginia was already up in arms, thanks to a fiery speech given by Patrick Henry in March, which ended with the words, "Give me liberty or give me death!" The royal governor, John Murray, Fourth Earl of Dunmore, declared Henry an outlaw, only to find that most of the militia had gone over to the Patriots; in June he had to take refuge on a British ship in Chesapeake Bay. To regain control over Virginia and to build a new loyalist force, the governor did something in November that showed he was ahead of his time; he issued an emancipation proclamation. According to this, any slaves or indentured servants who joined the British army would earn their freedom. The proclamation caused a slave revolt in the western part of Virginia, but otherwise it backfired; slaveowners who didn't want to see their slaves run away were now persuaded to become Patriots! By the end of the year Dunmore had fled to New York, and he returned to Britain the following summer. The militias of North and South Carolina also forced their governors to flee; attempts to reinstate them in early 1776 (by raising a loyalist militia in February, and by attacking Charleston in June) were soundly defeated.

Through the Cumberland Gap

This is a good place to mention that by the time the Revolution had started, settlers were moving west again. In the mid-eighteenth century, Virginia established several companies to explore and claim land on the other side of the Appalachians. The explorers who led the way came to be known as "long hunters," because their hunting trips kept them away from home for weeks or months at a time. One of them, Thomas Walker of the Loyal Land Company, discovered a pass directly through the Appalachians, the Cumberland Gap, in 1750. Then a land surveyor, Christopher Gist, traveled through the area that would later become Kentucky in 1751, as part of an expedition to survey the Ohio River valley. Settlement, however, would have to wait until after the French and Indian War and Pontiac's Rebellion.

The most famous long hunter was Daniel Boone, who heard from another frontiersman about some good land south of the Ohio River, which currently had no Indians living on it. This was what we now call the Bluegrass region, and Boone reached it from his native Pennsylvania (by way of Ohio) in the winter of 1767-68. However, this wasn't a very practical way to get there, because most of the prospective settlers would be coming from Virginia; he found a more useful path, through the Cumberland Gap, in 1769. Then the Transylvania Company hired Boone to blaze a trail from the Cumberland Gap to central Kentucky, where three settlements were founded: Fort Harrod (modern Harrodsburg) in 1774, and Boonesborough and Lexington in 1775. Boonesborough was named after Boone, of course, while Lexington got its name because the settlers had just heard about the American Revolution breaking out, and decided to name their town after the first battle. All these activities were a violation of Britain's 1763 proclamation, that reserved all land west of the Appalachians for the Indians, but the settlers simply ignored this, figuring that if they camped on the land long enough, it would eventually become theirs.

Later in 1775, the new communities sent a petition to the Second Continental Congress, declaring that they wanted to be recognized as a new colony called Transylvania(39). Congress did not vote on the petition, and besides, many of the settlers were really against it. Communications between "Transylvania" and the outside world were practically nonexistent, and they didn't want to add political isolation to their physical isolation. The anti-Transylvania settlers sent some representatives to the Virginia legislature, which dissolved the Transylvania Company, renamed the newly settled area Kentucky County (from Caintuckee, a Cherokee word meaning "Meadowland"), and proclaimed it a part of Virginia. Independence from Virginia was thus postponed until 1792, when it became the state of Kentucky.

From Fort Ticonderoga to Boston

When the Second Continental Congress opened for business in Philadelphia, it wasn't a one-issue meeting; it stayed in session from May 10, 1775 until March 1, 1781, when the Articles of Confederation were ratified. Since the Congress now found itself in charge of an armed rebellion, the first item on the agenda was a vote for the mid-Atlantic and southern colonies to support New England, which was carried unanimously. Then they had to agree on leadership; in the end they decided that John Hancock would be president of the Congress (he and Samuel Adams had to sneak out of Boston to attend), and that a southerner, ex-Colonel George Washington, would lead the new Continental Army.(40)

Before Washington could take command, the northern Patriots tried something else--an invasion of Canada. This must have looked like a very ambitious diversion, when one considers that most of the British army in North America was cooped up in Boston. The campaign got off to a good start in May 1775, with the fall of Fort Ticonderoga to colonial forces led by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold; this was soon followed by the surrender of the British garrison at Crown Point on Lake Champlain. Ethan Allen was taken prisoner by the British in September, so General Richard Montgomery took his place and captured the next British fort on the way, Fort Saint Johns, in November. After that, Montreal was quickly taken. Meanwhile, Arnold was leading another force of 1,000 men from Maine, up the Kennebec River. Now the plan was for Arnold and Montgomery to converge on Quebec; if they could take that city, the whole St. Lawrence valley would be in Patriot hands. They did meet, and attacked Quebec in late December, but the city had been fortified since the French and Indian War, and British defensive fire was very effective, killing Montgomery and wounding Arnold. Throughout the winter the Americans had Quebec under siege, and then in the spring of 1776, a British fleet got through with supplies and went on to take back Montreal, while the Americans, now disease-ridden and poorly supplied, were compelled to withdraw to Lake Champlain in May.

What the Canadian battles had shown was that although the Patriots did all right on the defensive, they weren't well suited for an offensive campaign. Most armed Americans at this stage saw themselves as "citizen soldiers," who would only fight for short periods and mainly to defend their homes. An invasion like this would not be tried again until the War of 1812, and strategists on the American side turned their attentions back to clearing the British from the Thirteen Colonies.

Back at Boston, twenty thousand Minutemen and other American troops now surrounded the city. On June 17, 1775, General Gage attacked the nearest American positions, on Breed's Hill and Bunker Hill. On the third charge they dislodged the Patriots, but the "battle of Bunker Hill" was a Pyrrhic victory; the British lost more than a thousand casualties (more than in any other battle of the war), while the Americans suffered 140 killed and 270 wounded. Afterwards, British General Henry Clinton wrote in his diary that "A few more such victories would have surely put an end to British dominion in America."

Not long after that, General Washington arrived on the scene in Massachusetts. He found himself in command of an army that was in no shape for waging war over any length of time. Most of the troops were raw recruits, and morale was poor; it would take time to turn such men into decent soldiers. They also had some customs that a southern gentleman would find peculiar, like officers elected by their enlisted men and black men serving with white men in the same units. Washington immediately began making changes to turn this army into a disciplined fighting force (he ended up letting the black soldiers stay, though as a slaveowner, he would have preferred to dismiss them), but there was still the problem of how to get the British out of Boston. The battle of Bunker Hill showed that any attempt to attack the Redcoats in the city would be very costly; nor could they starve them out, because the British navy controlled the sea, and could easily bring in more supplies and men. Then they remembered that they had captured several large cannon at Fort Ticonderoga, and decided to use those. It took all winter to move the cannon to Boston(41), and in March 1776 they were placed on Dorchester Heights, overlooking the city. Against these guns, the British were sitting ducks, unable to point their own cannon high enough to fire back. As soon as he realized his predicament, General William Howe, who had replaced Gage after the Battle of Bunker Hill, gave the order to evacuate, and the British sailed away to Halifax, Nova Scotia, accompanied by more than 1,000 Loyalist refugees. With that, the last remnant of British rule over the Thirteen Colonies ceased to exist. Today the anniversary of the British departure is celebrated in Massachusetts on March 17, as Evacuation Day.

The Declaration of Independence

Throughout 1775, it was never clear what the Patriots were fighting for. Some saw the conflict as a larger, bloodier version of previous disputes between the colonies and London, and after the fighting stopped, they would go back to being good subjects of the king. The trend, however, was against any kind of a peaceful resolution. A final "Olive Branch Petition," approved by the Second Continental Congress in July 1775, was rejected by the king, and in December, Parliament passed the Prohibitory Act, which outlawed trade with the rebellious colonies and set up a naval blockade.

It was Thomas Paine who gave the Revolution a cause its followers could rally around. In January 1776 he published a pamphlet with the simple name of Common Sense, which persuasively argued that the time had come to make a complete break with Great Britain. It began with this paragraph, which let everyone know that the true patriot must be in it for the long haul:

"These are the times that try men's souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph."

Paine asked whether "a continent should continue to be ruled by an Island," referring to Britain's control over commerce and the current blockade. There also was the issue of how to fight with a shrinking, impoverished army. The Continental Congress did not have the power to tax the colonies, or draft new soldiers to replace casualties and deserters, so it could give its soldiers little besides moral support. Britain had enemies in Europe--especially France--who might help, but why should they do anything if the colonists intended to remain British citizens? George Washington found Common Sense so inspiring that he ordered it read to all his troops. Within a few months, the idea that the Thirteen Colonies should become a new nation went from being the goal of radicals to the mainstream opinion among Patriots. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a proposal at Congress to vote for independence, and it was passed on July 2; the only opposition came from a few delegates who called for more time to decide.

At the same time, many felt that Congress needed to justify its actions with a formal declaration of independence. A committee of five was selected to write it: John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut. Adams led the committee, and he picked Jefferson to write the declaration's rough draft. When Jefferson asked Adams why he wouldn't write it, Adams said, "I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular." Since the 1760s, Adams had made a name for himself as a lawyer, and was known to be stubborn, abrasive, and a tireless crusader for truth and justice. Adams also felt that a declaration would impress the most people if a Virginian wrote it, because Virginia was the oldest and largest of the thirteen colonies. Anyway, Jefferson knew the importance of his task, so he worked very carefully, spending eighteen days on the draft, though it was only one page. After Franklin and Adams made a few minor corrections, the committee presented the document on June 28, and on July 4, 1776, Congress voted to accept the final version.(42) With that event, the United States of America was born.

One of the reasons why Jefferson took so long on the Declaration is that Congress didn't just want a majority of those present to ratify it; they wanted the vote to be unanimous. They went for a total commitment because once they signed the document, they would be traitors in the eyes of the king and Parliament, to be hanged if caught; hence the need for unity against an opponent as strong as the British Empire (Benjamin Franklin said at the signing, "We must all hang together, or most assuredly we will all hang separately."). For that reason, about four-fifths of the Declaration is a laundry list of twenty-seven grievances against His Majesty and Parliament. This was meant to show that Americans had been forced to dissolve their ties with London by the abuses of the British government; they weren't simply revolting to get out of paying taxes. Some of the charges were rather trivial (one accused the king of taking too long to approve new laws the governors had passed, and not letting them go into effect until he had approved them), but when put together, there was something for everybody in Congress.(43) One could make the case that to lawyers of the eighteenth century (and many of the Founding Fathers had been full or part-time lawyers), those complaints were the most important part of the document, and that a legal argument made it easier to defend the more abstract argument for universal human rights ("life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness") that the Declaration is chiefly remembered for today.(44)

The (British) Empire Strikes Back

By no means did the British think they were defeated, just because they had been forced out of their rebellious colonies. Like ancient Rome, Britain had a tradition of losing the first battle, and then going on to win the war. Moreover, England, Wales, and Scotland had a combined population of about nine million (more than three times as much as the Thirteen Colonies, despite the rapid growth of the latter), the best navy in the world, an army that was at least as good as anybody else's, and plenty of money from Britain's vibrant economy. Surely, the British government reasoned, it should be possible to combine these resources with those groups in the colonies that didn't support the Revolution (Indians, Loyalists and most slaves), and grind the Patriots into submission.

Even while Congress was signing the Declaration of Independence, the British were on their way back. Reinforcements were sent to Halifax, which now was serving as Britain's advance base, and General Howe received orders to capture New York City. Soon the largest armada seen so far in the New World was transporting 30,000 men from Halifax to New York. They landed first at Staten Island, and then quickly moved to Long Island, where Washington had 10,000 troops dug in at Brooklyn Heights. Howe not only had the larger army, he showed himself to be a better strategist; in August he outmaneuvered Washington and drove him off Long Island. Washington went on to lose New York City in September, Upper Manhattan in October, and the forts on the lower Hudson in November. Most embarrassing was his failure to order the evacuation of Fort Washington, on the northern end of Manhattan; when the British took it in November, the Americans lost 3,000 soldiers and scores of cannon. Altogether, the battle for New York was Washington's worst defeat, and he spent the rest of the war trying to atone for it. As for the British, they were doing well enough that Howe could send General Clinton and 6,000 men to take Newport, RI (December 1).

It would have worse for Washington if Benedict Arnold had not saved the day on the northern front. Once they had New York City, the British were planning to occupy the Hudson valley, thereby conquering the whole state of New York and cutting off New England from the other colonies. A British counterattack from Canada, led by General Guy Carleton, was halted by Arnold at Lake Champlain (the battle of Valcour Island); with hindsight, we can see that ended Britain's best chance of winning the war.

As for Washington, he couldn't keep New Jersey, let alone New York, in Patriot hands. In December he withdrew across the Delaware River to Philadelphia, and advised the Continental Congress that "on our side the war should be defensive." What he was thinking was that their best chance of winning would come if they lured the British inland, away from their ships and supplies. Nevertheless, he soon got a chance to hit them near the coast. One of the rules of European warfare was "don't fight in the winter," so accordingly, the Redcoats and their Hessian auxiliaries set up winter quarters in Princeton and Trenton, New Jersey.(45) On Christmas night, 1776, Washington sneaked back across the Delaware, attacked a camp of 1,400 Hessians at Trenton, and captured 900 of them, while only suffering four wounded (one of the wounded was future president James Monroe, then a lieutenant). When the British heard about this, the general on the spot, Charles Cornwallis, marched out of Princeton with his troops to get Washington. Small groups of American soldiers managed to slow down Cornwallis, so that his force didn't reach Trenton until late on January 2, 1777. Still, he had a larger army than Washington did, so Washington decided to sneak away; his army left their campfires burning so that the British would think they hadn't moved. That night, the Americans marched to attack the British rear in Princeton, winning a bloody skirmish the next morning against the garrison stationed there. Cornwallis and his men awoke to the sound of cannon firing behind them, rushed back to Princeton, and Washington caught and defeated them, too (see footnote #30). The British lost 500 men altogether, and Cornwallis retreated to Brunswick, abandoning southern New Jersey. For Washington these were small victories, but they loom large in American history because they restored the morale of the Americans.

General Washington crossing the Delaware. The actual crossings were less dramatic than this famous painting would suggest. The first time Washington crossed the river, he was in full retreat, and the second crossing was done at night, in the middle of a winter storm. In fact, that was why he surprised the Hessians; nobody thought he would try to come back under such conditions. Finally, I think Washington would have had enough sense to not stand up in a boat. Incidentally, the young man holding the flag is another future president, James Monroe.

Saratoga: The Turning Point

Both sides had reason to be optimistic as 1777 began. The Americans were in good spirits simply because they had won the last battle of 1776. The British, however, were in a better military situation. They had forced their way back into the colonies, and showed that in a fixed battle, they would usually beat the Americans. For them 1777 looked like it would bring more victories, so they predicted it would be the "year of the hangman." However, they had not yet reconquered much of the land; how would they go about doing that, and even more important, win over the inhabitants? The best idea anyone could come up with was a repeat of the 1776 northern campaign--march through the Hudson valley and isolate New England. General John Burgoyne, Carleton's replacement as commander in Canada, would lead his army of 10,000 men due south from Montreal. A second force (300 regular troops plus 650 Canadians and Tories, and 1,000 Indians, mostly Mohawks), led by Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger, would sail across Lake Ontario to Fort Oswego, and create a diversion by marching from the west, following the Mohawk River. Burgoyne didn't think he had enough men to do the job by himself, so he counted on Howe to march up the Hudson from New York City, and all three armies would meet in the neighborhood of Albany.

Unfortunately Howe had a plan of his own, and London could not get the two generals to coordinate their plans. Remembering Washington's performance from the previous year, Howe figured that if he could lure Washington onto a battlefield and beat him, the road to Philadelphia would be wide open. Surely a chance to capture the rebel capital outweighed going after any other objective, so Burgoyne would have to wait until Howe returned from his Philadelphia campaign. Since then historians have debated which general is most to blame for the British defeat of 1777: Howe for abandoning Burgoyne, or Burgoyne for choosing to go ahead anyway after he learned that Howe would not support him.

Burgoyne and St. Leger were ready to move in June. On June 24 Burgoyne reached Crown Point, a fort on Lake Champlain that marked the northernmost spot under American control, took it without opposition, and went on to capture Fort Ticonderoga on July 6, and Fort Anne on July 7. He also managed to catch up with and defeat the rear guard of the retreating Americans at the battle of Hubbardton. Then the three American generals on the northern front, Philip Schuyler, Arthur St. Clair and Benedict Arnold, found a weapon to slow the British advance to a crawl--the axe. Their troops began felling trees onto the roads, and because the British were bringing wagons and cannon, they had to stop to remove each tree; as a result, they only moved 23 miles in 24 days. It took until July 29 for Burgoyne to reach and capture the next fort on the way, Fort Edward.

The British army steadily shrank as it moved along. In addition to the usual casualties, Burgoyne left 400 men to garrison Crown Point, and 900 at Ticonderoga--more than he should have taken out of his attacking force. They also ran low on supplies, especially horses, making it necessary to send out foraging expeditions. One of those expeditions resulted in a disaster when it was ambushed near Bennington, Vermont; the New Hampshire militia and Vermont's Green Mountain Boys killed 200 British soldiers and captured 700 (August 16). Now the Indians traveling with Burgoyne sensed trouble and slipped away, leaving the British army blind in the forest.

On the western front, St. Leger left Oswego on July 25, and met his first significant opposition at Fort Stanwix in early August. He drove off the first force that came to the rescue of the fort, at the battle of Oriskany; this battle was interesting because it saw Iroquois warriors fighting on both sides (see footnote #34). Benedict Arnold led the second relief expedition, and because he only had 900 men (800 regulars plus 100 local militiamen), he used a trick; he allowed a captive to escape who thought the force was much larger, and when he told St. Leger, the news persuaded St. Leger to abandon the siege of Fort Stanwix. Arnold sent a detachment to pursue him on the way back to Canada, and then rejoined the main American army at Saratoga. Burgoyne would have to win or lose on his own.

After hearing about the latest battles in upstate New York, Congress appointed a new commander, General Horatio Gates, since the generals on the front line had failed to save forts like Ticonderoga. He arrived at Bemis Heights, where the Americans were trying to build fortifications between Saratoga and Albany, on August 19. The other generals resented him taking command, because so far in the war he had done little besides follow Washington around. Schuyler resigned the next day, and Arnold disagreed with Gates so strongly that Gates had him removed from command, leaving him to pace in headquarters without anything useful to do. Then Burgoyne arrived at Saratoga; he was down to 7,000 men, while the American force had grown until it was larger than his, so he paused to see if there was any news of Howe or any other British generals on the way.

The so-called "battle of Saratoga" was really two battles, one at Freeman's Farm (September 19), and one at Bemis Heights (October 7). The first battle took place when Burgoyne realized that he wasn't going to get any help, and started moving again. He succeeded in taking the farm that the battle is named after, but lost 600 men while the Americans lost 300. Still, Burgoyne wasn't the type of general who would turn around when the going got tough, so he made a second attempt to break through the American line at Bemis Heights. It failed; he was surrounded by an American army that had grown to 17,000, and forced to surrender on October 17. The Patriots took 5,800 prisoners in a victory that was more important than all their defeats to this point.

Saratoga also produced a character who, like Arnold, would become a traitor later on. This was Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson, a young aide to General Gates, and he was given the job of delivering the official report of the victory to the Continental Congress. He arrived with the good news several days later than expected; first he was delayed by a fierce storm he failed to outrun, then he stopped to attend a party and got plastered, and finally he took time off to visit his girlfriend. As compensation for his tardiness, he threw in some made-up stories about what he did at Saratoga, and did such a good job of charming Congress that they promoted this courier to the rank of brigadier general, though he was only twenty years old and it meant passing over some colonels who were more experienced. A few months later, however, Wilkinson was accused of being involved in a plot to replace Washington with Gates as the army's comander-in-chief, and forced to resign. Congress then appointed him clothier general of the army--definitely a desk job--but in 1781 he had to resign that post as well, when he was charged with corruption. We'll come back to Wilkinson in the next chapter.

Valley Forge and the Battles for Philadelphia

For someone so certain that he was doing the right thing, Howe acted remarkably cautious. When he was ready to move out, he loaded 20,000 men on 250 ships and headed south along the coast, leaving General Clinton and 3,000 men to guard New York City. The expedition went all the way to Virginia, entered Chesapeake Bay, and came ashore to attack Philadelphia from the south. This maneuver took all of July and August, when he could have gotten there much quicker by marching overland through New Jersey; this really perplexed Washington. Otherwise things went as planned for the British; the Continental Congress fled to Baltimore, and Washington was compelled to defend Philadelphia, though he was outnumbered. Howe knocked him out of the way at the battle of the Brandywine on September 11, and then occupied Philadelphia on the 26th. A counterattack by Washington on Philadelphia's suburbs failed (the battle of Germantown, October 4), and then Howe retired for the winter.(46) He now held the second and third largest cities in the United States. In western Europe this would have made a big difference in the course of a war, and it certainly embarrassed the Patriots, but since colonial America was more of an agrarian society than an urban one, the Americans could still fight as much as ever.

Washington and 11,000 soldiers spent the winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge, twenty miles from Philadelphia. This was the lowest point of Washington's career; one fourth of the men died of disease or exposure to the cold weather, while desertions and a lack of provisions further reduced the army to about half its former size. The deprivation came about because the British bribed the local farmers to supply them, instead of Washington, and Congress refused to send anything. By contrast, the British enjoyed a comfortable winter in Philadelphia. When spring arrived, Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, a Prussian officer who volunteered his services to the American cause, restored discipline and morale to Washington's remaining troops by training and teaching the military tactics that Prussians are known for.

While he was suffering at Valley Forge, Washington missed the best news, as he had at Fort Duquesne twenty years earlier. Saratoga is not remembered as the turning point of the war because it changed the military situation on the ground (though it did), but because of the effect it had on European opinion. First of all, General Howe was forced to resign in disgrace, because he had not assisted in the northern campaign when he could; General Clinton now became the supreme British commander in the colonies, with General Cornwallis as the new Number Two. Even more important, Saratoga showed Europeans that the Patriots might win after all. France had been secretly sending arms, ammunition and uniforms since 1776; they didn't really expect an American victory, but couldn't resist an opportunity to hurt their archenemy.(47) The Patriots had all hated the French when they were loyal British citizens, so they didn't want to talk much about French aid, either. However, after Saratoga the French were no longer worried about how London might react, so in February 1778, the French government declared war on Britain.(48)

France's entry into the war changed things in a big way for the British. From their point of view, the American war had turned into a European War; the French replaced the Patriots as the primary enemy. It also meant that any British colonies, especially the rich islands in the Caribbean, could come under attack by the French navy. London insisted that those islands be protected, so General Clinton received orders to send 5,000 of his soldiers to the Caribbean. To do this he would have to abandon Philadelphia, which wasn't worth much because he had not captured the American government when he took it the year before. Nevertheless, Clinton complied, and marched from Philadelphia to New York. On the way his forces were spread out across the New Jersey countryside, and Washington tried to intercept them, only to be defeated again (the battle of Monmouth Courthouse, June 28, 1778). British forces also repelled a joint Franco-American attack on Newport, RI. After those two battles, both sides settled in for the winter (already!).(49)

France's involvement encouraged some other countries that wanted to settle a grudge with Britain; Spain declared war in 1779 and the Netherlands did in 1780. The Spanish Governor of Louisiana, Count Bernardo de Galvez, received orders to take back the forts Spain had lost to the British in 1763, so he managed to reconquer West Florida by the end of the war, taking Natchez and Baton Rouge in 1779, Mobile in 1780, and Pensacola in 1781. When the British threatened to take Spanish-held St. Louis, a Spanish officer, Lt. Eugenio Pouree, led 151 men (91 Spaniards and 60 Indians) on an expedition across Illinois that captured Fort St. Joseph in Michigan (January-February 1781); this move took the British by surprise because they thought nobody from a warm country like Spain would try such a long overland march in the winter. All this helped the Patriot cause, but because Galvez moved so slowly, it didn't make a difference in the war's final outcome. The Dutch response was even weaker, because the Dutch only had twenty warships available when they declared war; they mainly fought in the parts of Africa and Asia where both the Dutch and the British had colonies, and the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780-84) was an economic disaster for the Netherlands.

It was during this time that Benedict Arnold became the most notorious traitor in American history. He had played a crucial role at Saratoga, disobeying General Gates' order to stay at headquarters during the battle of Bemis Heights, and riding forth to rally the troops, until he was shot in the same leg he had been wounded in, two years earlier. Historians agree that he almost singlehandedly kept the British from escaping when the battle turned against them, though afterwards Gates got all the credit for winning Saratoga. After recovering, Arnold went to spend the winter with Washington at Valley Forge. Washington put him in charge of Philadelphia after recovering that city, but he was still a bitter man, feeling unappreciated because he had won more battles than any other American general, including Washington, but had been passed over for promotion more than once. Moreover, as a veteran of the French and Indian War, he strongly opposed the Patriot decision to ally with France. In Philadelphia, he spent so much on living the good life that he fell deeply into debt, and in 1779 he married a young lady whose sympathies were pro-British, so he was receptive to any offers the British might make. Over the next sixteen months he corresponded with General Clinton, though it was an act of treason to do so, and when he got himself appointed commander of West Point, a strategic fort on the Hudson River, in 1780, he offered to hand it over to the British for £20,000 and a commission as brigadier general. The plot failed because the go-between, British Major John André, was captured with documents revealing both the plot and Arnold's role in it. Arnold fled to the British, and they gave him the general's rank, but only £6,000 of the promised money, because he hadn't delivered West Point to them (nobody likes a turncoat, after all). After that he saw action in Virginia and Connecticut, and when the war ended he sailed to England, where he spent the rest of his life in much-deserved scorn and obscurity.

How a dollar bill might look today, if Benedict Arnold hadn't switched sides. See also my favorite alternate history story, Crossroads of Destiny, by H. Beam Piper.

On the Wild Frontier

The Iroquois weren't the only Indian nation divided by the American Revolution. Both the British and Congress tried to get Indians to join their side, or at least stay neutral, so the Cherokee, Shawnee and Delaware tribes were also split into factions. Consequently Indians played a role in the battles fought west of the Appalachians, with their warriors on both sides. The frontier wars were more ruthless than the ones in the Thirteen Colonies, because civilians and the villages they lived in were the most common targets. An example of this was the 1778 Wyoming Valley Massacre, where Tories and their Indian allies killed 360 Patriots near Wilkes-Barre, PA, and then proceeded to destroy 1,000 Patriot homes in western Pennsylvania; the Tory commander reported taking 227 American scalps, though it is not clear how many civilians actually fell victim to them. This was soon followed by the Cherry Valley Massacre, where Tories and Indians attacked a fort and its neighboring village in New York, killing and scalping at least 33 civilians. The Americans retaliated with a major raid called the Sullivan Expedition, which destroyed at least forty Iroquois villages in western New York in 1779.

Earlier we noted that Kentucky was uninhabited when the first white settlers moved in, because the Cherokee and Shawnee tribes agreed to keep the land between them open, as a hunting ground. But just because they weren't willing to live there didn't mean they would just sit by and watch somebody else occupy the land. Thus, the British were able to find allies among the local Shawnee, who attacked Boonesborough in September 1778. The siege of Boonesborough was called off after ten days, but Indian raids were a problem all Kentucky settlements faced for the rest of the eighteenth century. One of those raids in 1786 killed Abraham Lincoln Sr., the grandfather of the future president by the same name.

The most significant campaign on the western front was launched by a Virginia frontiersman, George Rogers Clark. In 1778 he left Fort Pitt (see footnote #32) and marched all the way down the Ohio River, capturing Fort Sackville, a British fort at modern Vincennes, Indiana, on the way. On the banks of the Mississippi, he also seized Kaskaskia, the oldest European settlement in Illinois, which had been founded by the French 75 years earlier. General Henry Hamilton, the British commander at Detroit, retook Fort Sackville, but Clark returned in a surprise march in February 1779 and captured it again, along with Hamilton himself. Clark's adventure allowed the United States to claim the Ohio and Mississippi valleys when the war ended.

By this time, other Americans were beginning to settle Tennessee, and as with Kentucky, "long hunters" led the way. This was the first time anybody had shown much interest in the territory since Spanish explorers passed through it in the sixteenth century. French fur traders established a trading post in the middle of the territory in 1717, but it was abandoned by 1740 (the British called it "French Lick"). Then in 1779, James Robertson led two hundred settlers from Watauga, a recently established community in northwestern North Carolina, and on Christmas Day they arrived at the spot where the French had their outpost. There they built a new fort, which they called Fort Nashborough, in honor of Francis Nash (a North Carolina general who had been killed at the battle of Germantown); this name was shortened to Nashville in 1784. They were joined by sixty more families in April 1780, who arrived by boat. Officially they were all still citizens of North Carolina, but Nashville's rapid growth, which soon exceeded that of Watauga, insured that they would be successful, once they were on their own.

The final battles of the American Revolution were fought in the west, presumably because they were the last to hear that the war was over. Perhaps the worst episode was the Gnadenhütten massacre, in which members of the Pennsylvania militia killed ninety-six Christian Munsee Indians (members of the Delaware tribe that had been converted to Christianity by Moravian missionaries), including sixty women and children, because they suspected the Indians had taken part in recent raids (March 1782). Then in August 1782, ten months after Yorktown (see below), a force of 1,000 British and Indians attacked Bryan's Station in northern Kentucky, and ambushed the force of 180 Kentucky militiamen that came to the rescue. That incident, now called the battle of Blue Licks, was one of the worst defeats Americans suffered in their struggle for possession of the west. However, it did not change the course of the war, because the British had already surrendered elsewhere. Consequently, the Indians felt betrayed a year later, when the British handed over Kentucky to the United States; they thought winning the last battle would keep Patriots out of the frontier lands!

Showdown at Yorktown

The summer and fall of 1778 saw British forces in the colonies concentrated in two ports, New York and Newport. The troops sent to fight the French in the Caribbean did well, and Clinton had another trick up his sleeve. In December 1778 he sent 3,500 men south to take Savannah, GA, the southernmost port in Patriot hands. This move was a complete success, and one month later the troops captured Augusta, bringing all of Georgia, the colony with the smallest and most unsteady population, back under British rule.

Clinton was attracted to the southern colonies because of their cash crops; tobacco, rice and indigo earned a more reliable profit than the products of the North. He also found out that Georgia had a stronger than expected Loyalist community, and even the local Patriots distrusted the New England radicals that had so much control over their movement. Before 1779 was over, he found that he could turn the government of Georgia over to native Loyalists, have them train a new militia that was loyal to the Crown, and use his regular troops in an invasion of South Carolina. And as long as they could count on enough "Tories" to mind the areas they had already conquered, it should be possible for the Redcoats to keep on moving, maybe even until they were back in New York. This was the best strategy the British had come up with for winning the war.

After beating off a Patriot counterattack on Savannah, which had been backed up by French ships (October 1779), the British were ready to move into South Carolina. They besieged Charleston, and when it fell in May 1780 they captured more than 5,000 American troops, a spectacular success. Clinton felt confident enough to return to New York, leaving Cornwallis in command, and Congress tried to turn the situation around by putting Horatio Gates, the hero of Saratoga, in charge of all troops in the south. This amounted to approximately 3,500 men, more than Cornwallis had, but then Congress negated that advantage by forcing Gates to fight before he was ready. The result was a rout at the battle of Camden in August, where the Americans made one of the fastest retreats in military history. This was a low point in American morale, as American strength in the southern theater declined to less than a thousand men.

Meanwhile in the north, superior British discipline led to a naval battle so embarrassing for the Patriots that they refused to talk about it afterwards, to the point that few people have even heard of the battle. In the summer of 1779 the British sent an expedition of three ships and 700 men to Maine; the plan was to detatch Maine from Massachusetts by starting a Loyalist colony there, and calling it New Ireland. They landed at the mouth of the Penobscot River and built a fort; when the Patriots heard about it, they sent their own expedition to get rid of the fort. The Patriots had forty-two ships (eighteen warships plus transports, the largest fleet assembled by the Americans during the war), more than a thousand militiamen, and six cannon, which should have been enough to do the job. They landed and captured the nearest heights, half a mile from the fort, but suffered a hundred casualties in the landing, so the local commander decided to bombard the fort from a distance instead of attacking it by frontal assault. Now the Americans were paralyzed by a communications breakdown; the general refused to attack the fort until the admiral took out the British ships, while the admiral refused to attack the ships until the general caused a diversion by attacking the fort! The British, on the other hand, were able to get reinforcements from New York, and build higher walls around their fort. In the end, those reinforcements decided the battle. Ten British ships attacked the American fleet, trapping it in the Penobscot River; all but one of the American ships were destroyed or scuttled between the fort and an upstream settlement (present-day Bangor). With its support gone, the Patriot army fled overland to Boston, losing nearly all its food and ammunition on the way. The final score for the Penobscot expedition: 25 British killed and 34 British wounded, while 474 Americans were killed, wounded, captured or missing. The Patriot in charge of the artillery, Paul Revere (see footnote #38), was accused of disobedience and cowardice, courtmartialed, dismissed from the militia, and later exonerated. Maine stayed in British hands until the 1783 Treaty of Paris.

For the British, after conquering Georgia and South Carolina, the next logical step was to invade North Carolina, but instead, they began to lose control of South Carolina. Patriot bands led by Francis Marion, Thomas Sumter, and Andrew Pickens launched a successful guerrilla campaign. At the battle of King's Mountain (October 7, 1780), the old, pro-Patriot militia defeated the new, pro-British militia. For the regular army, Washington sent Nathanael Greene to replace Gates and recruit a new force, and he sent a small force led by Daniel Morgan to keep Cornwallis busy. Cornwallis responded by sending a force of his own to get Morgan, led by his most brutal officer, Banastre Tarleton. Tarleton caught up with Morgan and Pickens at Cowpens, and walked into the trap they had prepared; the resulting battle (January 17, 1781) saw a double envelopment from the Americans that killed 110 Redcoats and captured 830, while the Americans suffered only 12 killed and 61 wounded.

Cornwallis wouldn't take a defeat for an answer, and pursued Morgan and Greene with a vengeance into North Carolina. Here he usually couldn't catch up with the Americans, and ended up fighting them to a draw when he did (the battle of Guilford Courthouse, March 15, 1781, in modern Greensboro, NC). Even worse, he couldn't find enough Loyalists to help him, the way they had in South Carolina and Georgia. As for Greene, he came up with a motto that described his approach to combat: "We fight, get beat, rise, and fight again." Clinton had given Cornwallis instructions to pull back to Charleston or Savannah if he couldn't conquer North Carolina, and wait there for reinforcements. Cornwallis didn't do this because he was a fighting general like Washington and Burgoyne, not the type of general who likes to march his men around in fancy maneuvers. Instead of retreating, he continued to advance into Virginia, where he would get reinforcements by meeting with the British army already there, now commanded by Benedict Arnold.

Cornwallis and Arnold met no serious resistance in Virginia. Very little fighting had taken place there since 1775, so most of Virginia's soldiers were in other colonies. In 1780 Thomas Jefferson, then the governor, moved Virginia's capital from Williamsburg to Richmond, which he thought would be a safer place, but that didn't stop Arnold from burning it in January 1781. The government moved west to Charlottesville, where it narrowly escaped a raid from Banastre Tarleton in June, having been warned in an overnight ride by Jack Jouett, the "Paul Revere of the South." Meanwhile, Washington sent the Marquis de Lafayette in March, to take charge of what troops were available, and Cornwallis tried to catch him, saying, "The boy cannot escape me."

Fortunately for the Americans, help was on the way; the French finally got serious about fighting the British in North America (see footnote #48). In July 1780 they sent General Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, with 5,000 troops to dislodge the British from Newport. After that he stayed in Rhode Island for nearly a year, reluctant to move because the British had blockaded Narragansett Bay, and the British were a threat to his ships as long as they were there. Then in the summer of 1781 the French announced they would deal with the British navy by committing twenty-seven ships under Admiral François Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse. Washington at this stage was in Connecticut, still obsessed with taking back New York City, and trying to catch Arnold, who had just arrived to make trouble in the neighborhood (Arnold subsequently burned New London, CT), but Rochambeau, who had finally left Rhode Island in May, convinced him that Cornwallis had become the biggest prize, and that all available resources should be committed to trapping him. Since Virginia was now where the action was, Rochambeau and Washington marched south in August, while de Grasse sailed from the Caribbean to Chesapeake Bay, and the Newport squadron slipped out to join de Grasse. Only Clinton stayed put; he watched Washington and Rochambeau march around his New York stronghold, without suspecting what they were doing.

Clinton had never approved of Cornwallis going to Virginia, and now he sent orders for Cornwallis to set up a permanent base at Yorktown, on the James peninsula. Cornwallis' men were tired and in need of supplies, so he agreed, confident that the British navy would back him up. And indeed, two squadrons were on the way, having been commanded to leave the Caribbean and spend hurricane season off the North American coast. What happened next would depend on which fleet got to Chesapeake Bay first, and it was the French who won the race; the British had gone to New York first. Too late, the commanders of the British squadrons, Admiral Samuel Hood and Admiral Thomas Graves, realized what was happening, and hurried to Virginia, only to find de Grasse blocking the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. The French ships outnumbered the British, by twenty-four to nineteen, and in the battle of the Chesapeake (September 5), Hood and Graves failed to break through the French line. Now de Grasse moved in to blockade Yorktown from the sea, and his ships contributed 3,000 men to the troops moving in by land. As at Saratoga, the Americans were able to gather reinforcements, until the Franco-American force numbered 17,000, while for the immobilized British, the situation could only deteriorate. Finally on October 19, 1781, the battle of Yorktown (really a siege) ended, when Cornwallis surrendered his 7,000 remaining men to Washington. England's adventure in Virginia ended just fifteen miles from where it had started, at Jamestown.

The Treaty That Ended It All

Britain still had 30,000 soldiers occupying New York, Charleston, and Savannah, but the will to fight had evaporated with Yorktown. Lord North reportedly said, "Oh God, it's all over, it's all over!" when he heard the news, and in March 1782 he lost a no-confidence vote (the first in the history of Parliament), forcing his resignation. The people would not accept new taxes to pay for the war effort, and the new government was not willing to support any more military campaigns on the North American mainland, because after nearly seven years of conflict, they were no closer to winning than when they had started.

Lord North's replacement, Charles Watson-Wentworth, the Marquess of Rockingham, quickly opened negotiations with the American diplomats in Paris (John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and Henry Laurens). There was no more fighting in North America, except on the western frontier (see above), so they reached agreement on all items regarding the United States by November 30, 1782, but the European powers weren't done fighting on other fronts. In 1782 and 1783 the British managed a recovery of their lost pride by defeating a Spanish attempt to take Gibraltar, and by capturing Admiral de Grasse in a Caribbean battle. Winning the final battles meant the British were in a better mood than expected when the final treaty was signed in Paris, on September 3, 1783.(50) This may also help to explain why today, history classes and textbooks in the United Kingdom barely mention the American Revolution, though in the western hemisphere it was critically important.

The Treaty of Paris recognized the complete independence of the thirteen ex-British colonies on the Atlantic seaboard. Remarkably, the treaty also granted the lands between the Appalachians and the Mississippi to the former colonies. The thinking here was that Britain did not want Spain or France to have these lands, but a strong and prosperous United States could be a good trading partner of Britain in the future, so if the British could not have this area, let it go to the Patriots. Because Spain had recovered West Florida late in the war, East Florida was returned to Spain, too. This meant that Britain had given up everything south of Canada on the continent, in return for the right to keep Canada, legal protection for British merchants who held debts in America, and promises to protect the property and rights of Loyalists.

There was a problem with fuzzy borders in three corners of the United States, because they were in areas that hadn't been completely explored and surveyed. Nobody knew yet where the Mississippi began, so the territory making up Minnesota, Manitoba and North Dakota was in dispute until 1818. In the northeast, nobody could agree on exactly where the frontier ran between the United States and Canada; that would require another treaty in 1842. Spain distrusted democracy and everything the Americans did, so at the peace talks Spain tried to make the Appalachians the western boundary of the United States, and when they didn't get this, they argued with the new nation over how much of Alabama and Mississippi they could have (Spain wanted the northern border of West Florida to be where the British had it, while the Americans wanted Spain to only have the Gulf Coast, because previously there had been little Spanish effort to build any inland settlements). Fortunately all of these disputes were resolved peacefully, and in the next chapter we will see how it was done.

This is the End of Chapter 2.

FOOTNOTES

37. The lack of knowledge about the north Pacific encouraged Jonathan Swift to place one of his fantasy islands, Brobdingnag, the land of giants, northwest of California, when he wrote Gulliver's Travels in 1726.

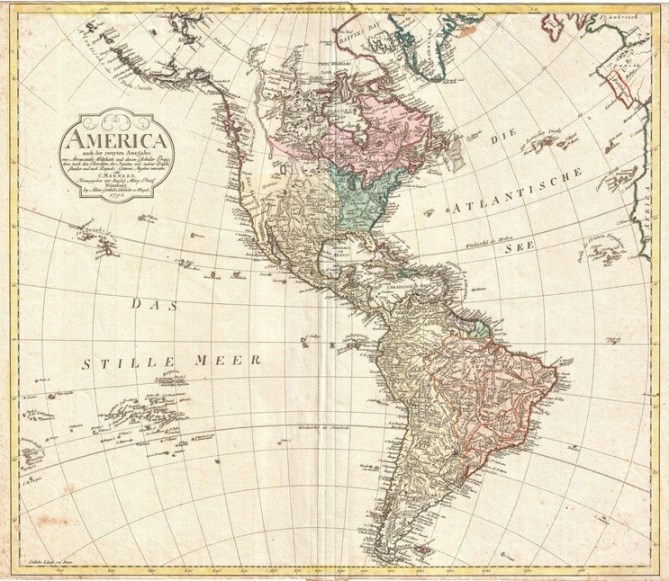

This 1796 map shows how in the eighteenth century, all of North America had been mapped out except the areas farthest north and west.

38. Here's another legend that needs clarification. Students of American history have all heard how the warning was given by Paul Revere riding out of Boston at midnight. Three other messengers, William Dawes, Samuel Prescott and Israel Bissell, also went forth. What really happened is that Revere, Dawes and Prescott were captured and detained by the British on the way; Dawes and Prescott went on to complete the mission after they were released, but Revere's horse was confiscated. As for Bissell, he didn't just warn the folks of Massachusetts; he rode from Boston to Philadelphia, a distance of 345 miles, to bring the news to the Continental Congress. He made the trip in four days and seven hours, and rode one horse to death to do it, but how many people have heard of him today? Though he was the least successful of the four riders, Paul Revere gets the credit because in 1860, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a celebrated poem about him.

39. I believe Transylvania is Latin for "beyond the forest," and Daniel Boone picked a name that rhymed with Pennsylvania, to make the place he explored sound just as good. He and the settlers probably weren't thinking of the Romanian mountains, and since this was more than a hundred years before Bram Stoker wrote Dracula, the name didn't have a spooky connotation, the way it does now.

Incidentally, Boone's trademark coonskin cap is an invention of twentieth-century pop culture. In the 1950s Walt Disney produced three short movies about another "long hunter," Davy Crockett (see Chapter 3), and they were so popular that the lead actor, Fess Parker, was cast to play Daniel Boone in a 1960s TV series; for that role he wore the Davy Crockett costume, including the coonskin cap. However, the real Daniel Boone wore a conventional wide-brimmed hat most of the time (see the painting below); he once said he didn't like the idea of going around with the skin of a dead animal on his head. Boone's statement tells me that if he was alive today, he'd probably be an environmentalist.

40. Washington went to Congress as one of the delegates representing Virginia, and it now appears he was dropping a hint that he wanted the general's job; he showed up for meetings in the old Virginia militia uniform that he hadn't worn in fifteen years.

41. The cannon were transported on sleds pulled by oxen, supervised by a 250-lb. officer named Henry Knox. One author that I read suggested that Knox inspired the oxen because he resembled them!

42. John Hancock signed his name twice as large as everybody else, so that, as he put it, the king could read it without his glasses; that was considered a bold move. It also made his name a slang term for signatures, as in "Put your John Hancock on that line."

We have gotten the idea, from John Trumbull's famous painting and the musical "1776," that the Declaration was signed right when it was ratified. Actually, all fifty-six signers weren't in the room at the time; some had not even been elected yet by the colonies/states they represented. It wasn't until August 2 that John Hancock put his signature on the document, and it took three more months (until November!) to collect the rest of the signatures.

43. But even Mr. Jefferson was forced to draw the line somewhere. He accused the king of letting the slave trade go unchecked with these words: "He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither." However, this was likely to offend sympathetic Englishmen and southern Patriots who owned slaves, so it was left out of the final version of the Declaration. Also, the Abolitionist movement was just getting started; the idea that slavery should be abolished was considered too radical by most people at this time.

44. On July 9, 1776, some Patriots in Bowling Green, NY, pulled down a lead statue of the king, and added injury to insult by melting it into bullets and shooting it back at King George's soldiers!

45. The British had augmented their army by hiring 30,000 German mercenaries; they were called Hessians because more than half of them came from the German state of Hesse-Kassel. The Americans generally regarded them as brutes, who had been brought to America to do King George's dirty work.

As daring as Washington's raid was, it shouldn't have succeeded. He lost the element of surprise when a British sympathizer saw Washington's men coming, and this Tory sent a warning message to Colonel Johann Rall, the Hessian commander. Still, we noted earlier that Washington was one of the luckiest generals who ever lived, and here luck worked in his favor again. Rall was playing cards and drinking when he got the note, and instead of letting it interrupt his game, he just put the note in his pocket. He didn't bother to read it until after he was captured.

Another reason why Washington shouldn't have won the battle is because the Hessians, aside from their commander, were stone-cold sober. Germans have a reputation for taking Christmas seriously (you may have heard the story about the Christmas truce during World War I), and while there were several barrels of rum handy, the Hessians hadn't touched them yet, partially from the need to maintain discipline, and partially out of respect for the birthday of their Lord and Savior. Washington took one look at the barrels, and decided they shouldn't be left there, but the men couldn't take the kegs with them either, so he ordered the men to empty the barrels. He should have been more specific; instead of throwing away the liquor, the troops promptly began drinking it. Luckily they had time to recover before their next battle with the British.

46. Warfare in the eighteenth century followed rules of gentlemanly behavior. During the battle of Germantown, General Howe's dog ran away and somehow ended up with the Patriots. Instead of claiming the dog as a war trophy, Washington sent it back to the British two days later, with a note that read, "General Washington's compliments to General Howe. He does himself the pleasure to return him a dog, which accidentally fell into his hands, and by the inscription on the Collar appears to belong to General Howe." In real life, just as in fiction, the hero is always kind to dogs and cats.

47. The Continental Congress sent three envoys, Silas Deane, Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee, to represent America in France. The French had already heard about Franklin, because of Poor Richard's Almanack, the book he published when he was a printer, and how he had discovered electricity by flying a kite in a thunderstorm, so they greeted him enthusiastically, treating him as if an ancient philosopher like Socrates had come back to life. Several authors have remarked at how Franklin appeared very simple when he appeared before King Louis XVI, wearing a plain brown coat and putting no powder in his hair, but soon he showed he had more wit than anyone else at the French court.

In the summer of 1777 an idealistic young French officer, Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert Du Motier, better known as the Marquis de Lafayette, came to Philadelphia and asked to enlist in the Continental Army, and when Congress tried to turn him away, he offered to serve without pay, so they made him a major general and he traveled with Washington, providing invaluable assistance as both an advisor and a military commander in his own right. After the war, Lafayette went back to France and distinguished himself in the French Revolution. He also became an early Abolitionist, freeing the slaves he owned and urging Washington to set an example by doing the same. Washington didn't, but he left instructions in his will for his slaves to be set free upon his death.

48. Lord North, the British prime minister, was deeply troubled by the inability of his generals to defeat the Patriot armies. After Saratoga he proposed a peaceful settlement of the rebellion. For this purpose he repealed the Tea Act and the Intolerable Acts, and offered a chance to return to the pre-1763 imperial relationship. It was too little, too late. Before the signing of the Declaration of Independence it might have worked, but now the Patriot leaders wanted nothing short of complete independence, and France gave them the ability to achieve it.

49. Despite Lafayette's presence (see footnote #47), France was never willing to be as aggressive or committed to the North American theater as Washington wanted. One reason why so little happened in 1778 was because Washington was waiting for French ships and soldiers, and they didn't arrive until 1780. Altogether it was a peculiar alliance.

50. Don't get confused because two Treaties of Paris are mentioned in this chapter, one ending the French and Indian War and one ending the American Revolution. Treaties are named after the places where they are negotiated/signed, and can anyone blame the diplomats, if they wanted to do their work in Paris?

Britain granted diplomatic recognition to the United States when the second Treaty of Paris was signed. Before that date, five other nations had granted recognition: Morocco (1777), France (1778), the Netherlands (1782), Spain and Sweden (both in early 1783).

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

The Anglo-American Adventure

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|