| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of the South Pacific

Chapter 4: The Great Pacific War

1914 to 1945

Part I

| World War I: The Prologue | |

| The Pacific Islands in the Interwar Period | |

| The Interwar Years: Australia | |

| The Cactus War and the Emu War | |

| New Zealand: Between Liberal and Labour | |

| "Under A Jarvis Moon" | |

| The Flight of Amelia Earhart |

Part II

The Pacific War Begins

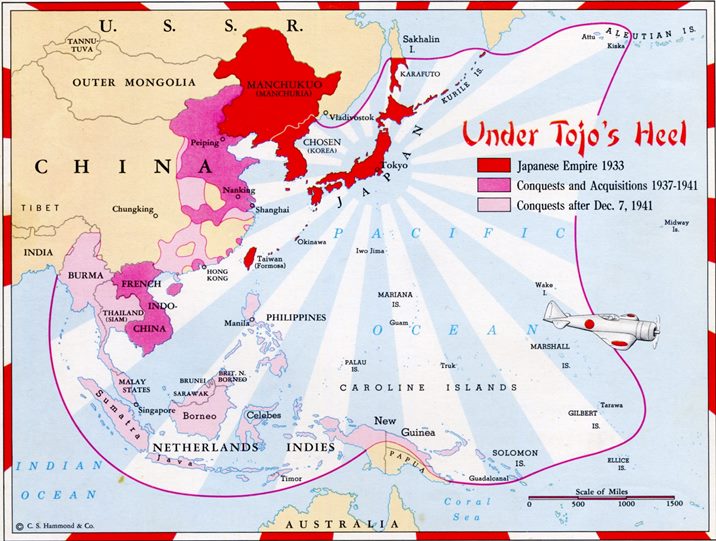

The transfer of most of Micronesia from German to Japanese hands brought a new empire into the game. Japan had been building an empire since the late nineteenth century, but the first Japanese acquisitions were close to home, in places we did not define as the "South Pacific": the Bonin & Volcano, Ryukyu and Kurile Islands, Taiwan, Port Arthur, South Sakhalin, and Korea. For that reason, early Japanese expansion is covered on this page. Those successes, plus involvement in World War I and the Russian Civil War, transformed the Japanese from underdogs that the Western nations had once rooted for, into the new bullies of the Far East.

Because of Japan’s aggressive streak, Japanese-Western relations quickly soured in the early 1920s. The Americans put pressure on Japan to leave the Chinese and Russians alone, and the British did not renew their alliance treaty with Japan when it expired in 1921. But after World War I the Americans did not want any more foreign entanglements, so they withdrew into themselves. When the Japanese resumed their expansionist policy, by invading Manchuria in 1931, the Americans were too deep in the Great Depression to care. Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1933, but the League did not even try to take away the mandate Japan had over most of Micronesia. Nor were the other colonial empires in a position to stop the Japanese. The Dutch had not been a major power for a long time, and while Britain and France now held more land than they had held at any other time in history, both had lost considerable resources and lives in World War I, making their empires much weaker than they looked. If a hostile nation attacked British or French colonial interests in the Pacific, their only hope was that they might be able to hold out until Uncle Sam woke up and came to the rescue.

The next step in Japan’s empire-building plan began on July 7, 1937, when the Japanese army used a skirmish near Beijing to justify invading the part of China they didn’t hold already. They overran most of northeastern China by the end of the year, but after that it turned out Japan was in the position of a pygmy trying to eat an elephant. Whenever Japanese and Chinese forces met, the Japanese usually won, thanks to better equipment and discipline, but China was so much bigger than Japan that the deeper the Japanese got into China, the slower the going was for them. This did not change the minds of any Japanese generals, who felt that in order to finish the war in China, they would have to conquer a place that had deposits of oil and metals, the resources a modern war machine needed. All they had to do was choose which place would be their next target.

Siberia held those resources, so at first Japanese strategists considered invading the easternmost part of the Soviet Union, the way they did in 1918, during the Russian Civil War. Clashes on the Manchurian border in 1938 and 1939 changed their minds about this; the Soviet Red Army was tougher than the Chinese and old Russian armies (for one thing, the Soviets were the first opponent the Japanese fought who had tanks). Japan would not have much of a chance of winning if it struck north.

However, the Japanese did not have to wait long for another opportunity. World War II was beginning in Europe at the same time, and in the spring of 1940, the German army won the quick victory it had failed to achieve in 1914, conquering the Low Countries and France in six weeks. This left the resource-rich Dutch and French colonies in Asia and the Pacific defenseless. The following summer saw Germany attack Great Britain, and although Britain survived, it had few thoughts or arms to spare for its empire’s most distant outposts. Japan responded by moving into French Indochina in 1940, and began to put pressure on Thailand.(15)

There was one nation left that could stop Japanese expansion in Southeast Asia -- the United States. The Americans had grown increasingly angry with the Japanese as the war with China went on. Now US President Franklin Roosevelt warned the Japanese that if they continued to make aggressive moves, the United States would stop selling Japan the oil it needed. Sure enough, when the Japanese completed their occupation of French Indochina in July 1941, Roosevelt kept his word. Unless the Japanese withdrew from Indochina, and began negotiations to return the Chinese territory they had taken, they would be allowed to buy only a month's supply of oil at a time.

For the Japanese leadership, this meant it was time to begin the war they had been planning against the British and Americans. On December 4, 1941, Japanese transports left the Chinese island of Hainan, carrying the two divisions that would be used for the invasion of British-ruled Malaya. A British search plane spotted this force, Britain correctly guessed it was coming to attack, and passed the news to the US government. In Washington the secretary of the navy asked, "Are they going to hit us?", and the nearest admiral reassured him: "No, they are going to hit the British. They aren’t ready for us yet."

Only half of the above statement was correct. What the admiral did not know what that Japan had also committed all six of its fleet carriers to take out the largest US naval base in the Pacific -- Hawaii’s Pearl Harbor. They left the Kurile Islands in absolute secrecy on November 26, escorted by battleships, cruisers and submarines. The Japanese also concealed their intentions by continuing negotiations in Washington over their activity in Indochina, right until the day of the attack.

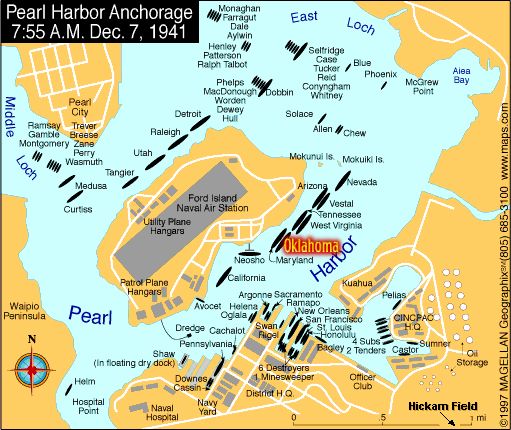

At dawn on December 7 the task force was close enough to begin launching their 356 planes for the air strike. Because it was a sleepy Sunday morning and they had managed to approach Hawaii undetected, surprise was complete. The planes attacked in two waves, lasting two hours; at "Battleship Row" they sank four of the eight battleships anchored there and disabled the rest. They also destroyed 200 American aircraft, catching most of them before they could take off. In return, the Americans shot down 29 Japanese planes, mostly in the second wave. This was a devastating blow to the US Navy, but not a permanently crippling one, because none of the Pacific Fleet’s three aircraft carriers were in port; they would play a critical role in the battles of 1942.(16)

A map of Pearl Harbor, showing the ship locations at the moment the attack began.

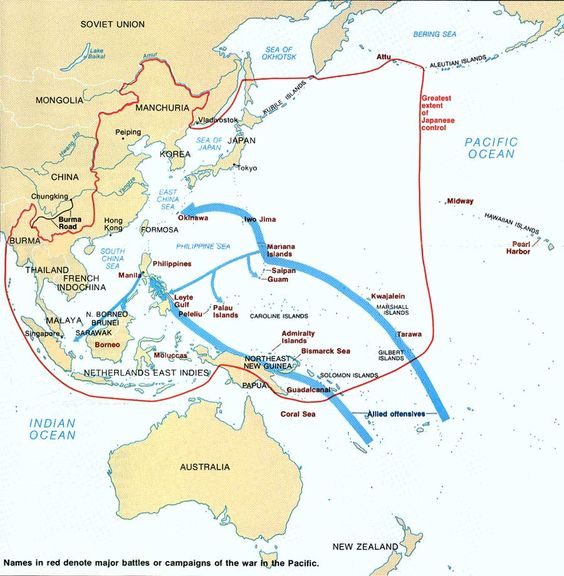

From Pearl Harbor to the Coral Sea

Once Japan decided that war was inevitable, the British and American colonies on the west (Asian) side of the Pacific were doomed. With German ships and planes in the Atlantic and their Japanese counterparts in the Pacific, there was no way the Americans and the British could get enough ships and planes into the area to defend their outposts; the supply lines from the mother countries were just too long. It showed in how fast their positions crumbled; Malaya, Singapore and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) were taken easily; Thailand joined Japan without resistance. By early March 1942 the Japanese controlled all of Southeast Asia except Burma and the Philippines. Those two areas took longer to conquer because Burma was large and full of nasty terrain (jungle-covered mountains), and because American and Filipino troops put up a determined defense, at the entrance to Manila’s harbor. Nevertheless, by May Japan subdued Burma and the Philippines as well.

Meanwhile, on the same day as the Pearl Harbor raid, small Japanese forces were sent to take the parts of Micronesia held by the Americans and British. Guam and the Gilbert Islands fell to them on December 10.(17) On remote Wake Island, however, the Americans unexpectedly beat off the first Japanese landing. Morale on Wake Island was so high that at one point, Pearl Harbor sent a radio message to Wake Island that asked, "Is there anything we can provide?" and the beleaguered defenders replied, "Send us more Japs!" This prompted Japan to send two of the aircraft carriers returning from Pearl Harbor, to support a second invasion force. On the second try the defenders were overrun; Wake Island surrendered on December 23. Still, in the end the Japanese suffered more casualties than the Americans did.

Next, because Australia was in the war on Britain’s side again, Japanese ships and planes headed southward to neutralize the Australians. On January 4, 1942, the planes started attacking Rabaul, on Australian-held New Britain. The troops arrived on January 23, and those members of the Australian garrison who weren’t killed or captured fled into the nearby jungle. Australian forces on New Guinea managed to rescue 450 of these personnel, while the rest (more than a thousand), realizing they were likely to starve in the jungle, surrendered over the course of February. Rabaul now became the Japanese base of operations, for activities on New Guinea, the Bismarck and Solomon Islands; it would be their strongest base below the equator.

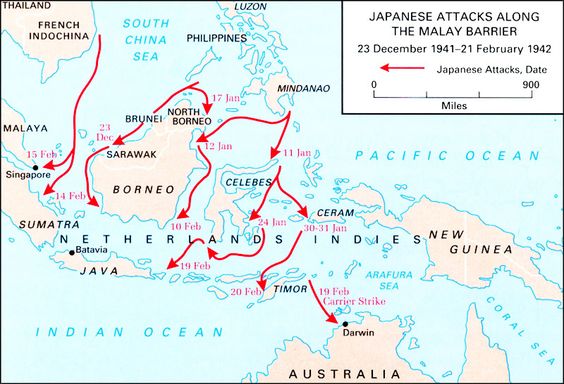

Some of the Japanese soldiers, ships and planes used to capture the Dutch East Indies came from the Philippines and Palau Islands. These included four of the aircraft carriers used at Pearl Harbor. On February 19, when the carriers were just east of Timor, they launched their planes against the nearest Australian city, Darwin in the Northern Territory. The air raid wasn’t followed up -- the planes were next used to assist in the landing of troops on Timor -- but Darwin was so devastated that it was abandoned for a while. The war had come to the shores of Australia; before it was over sixty-four air raids would strike Darwin.(18)

The Japanese invasion route, from the Philippines to Australia.

Fortunately for the Australians, the Americans now made the defense of the southwest Pacific their priority. In April US General Douglas MacArthur, who had escaped to Australia from the Philippines, was appointed Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA).(19) Admiral Chester Nimitz, the new commander-in-chief of the American fleet, strengthened the lines of communication between the United States, Australia and New Zealand, by establishing or strengthening garrisons on Christmas Island and Canton in the central Pacific, American Samoa, New Caledonia, and Fiji. The American-Australian partnership had its first test when the Allies slowed down the Japanese invasion of New Guinea. Japanese forces landed on New Guinea’s northeast coast in the second week of March, and proceeded to take the communities of Lae and Salamaua. However, casualties (in landing craft as well as men) were heavier than expected, and American planes were available to help the defenders. Those planes came from the Lexington, an American carrier in the Coral Sea, and because the Japanese had no ships that could deal with that carrier, they postponed their plans to conquer the rest of New Guinea.(20)

The first five months after Pearl Harbor had been a roaring success for Japan. China was almost finished, Southeast Asia was theirs, and they had acquired buffer zones around these conquests, should the Americans, Australians or British strike back. And it had been done at minimal cost. The army had suffered an estimated 25,000 casualties, and the navy had not lost any ships larger than destroyers. Now that Japan’s imperialists had the empire they wanted, would they be able to keep it?

The first task on the new empire-holding agenda was to get that pesky American carrier out of the Coral Sea. The nearest Japanese ships, which included two fleet carriers, the Shokaku and Zuikaku, had gone to the Indian Ocean to harass British shipping. Now those ships were recalled, and in March and April the next stage in the conquest of the Solomons took place, with the capture of Bougainville and the construction of air and naval bases on it. Then a new operation was launched, called Operation Mo, with these objectives:

- Tulagi Island would be occupied on May 3, 1942, to give the Japanese a base in the southern Solomons.

- Port Moresby, the capital of the Australian half of New Guinea, would be taken four days later.

- Nauru and Ocean Island would be captured for their rich phosphate deposits.

- Possible future actions to take New Caledonia, Fiji and American Samoa, to cut the supply/ communications lines between Australia and the United States.

What the Japanese did not know was that the Americans had not one, but two fleet carriers in the Coral Sea, the Lexington and the Yorktown. This gave Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, the commander of the carriers, the advantage of surprise. Fletcher couldn’t save Tulagi, which was taken on schedule, but he detected Admiral Goto’s force when it sailed to Port Moresby, and launched a strike on it with 93 planes. The onslaught of bombs and torpedoes caught the Shoho and sank it in thirty minutes; Admiral Goto halted the advance on Port Moresby and waited for Admiral Takagi’s carriers to arrive.

The rest of the day (May 7) continued to work in the Americans’ favor. The Shokaku and Zuikaku were less than an hour’s flying time to the east, and their planes attacked and sank the two American ships they encountered. One of the ships was a destroyer, the Sims; the other was thought to be a carrier, but it was actually the Neosho, a tanker. Sinking these was not enough to make up for the loss of the Shoho. Finally, on the night on May 7-8, Takagi launched an air attack on the Yorktown and her escort ships; it failed and most of the planes used in the attack were shot down.

The next day was a better one for the Japanese. Fletcher and Takagi located each other at 8 AM and launched their planes. American dive-bombers hit the Shokaku three times, while the Zuikaku sailed into a storm and escaped without damage. The weather was better over the American fleet, allowing the Japanese to hit the Yorktown with one bomb and the Lexington with two bombs and two torpedoes. Fires on the Lexington spread out of control; five hours later she was abandoned and had to be sunk with torpedoes. And on that note the two fleets broke off. Each side had one functioning carrier left, and the flight crews were exhausted, so they weren’t in the mood to continue the battle any longer. All the fighting had been conducted by aircraft; this was the first naval battle in which the opposing ships never got close enough to see each other.

The end result was that the Americans had fought the Japanese to a standstill. When it came to ships, the Japanese fared better; they had traded a light carrier for a fleet carrier, and this battle made it clear that fleet carriers had replaced battleships as the most important naval vessels. However, the Japanese had also lost more planes than the Americans, and for the second time, the Americans kept Port Moresby from falling into Japanese hands. Most of all, the battle had gained time for the Allies. The resources and manpower of the United States were still greater than those of Japan, and one of the rules of military history is that the longer the war, the more likely the big contestant (in this case the USA) will win. Now the question was: When and where would the United States use its superior numbers and industry to turn the tide of war against Japan?

The Japanese Empire, at its peak in 1942.

The Battle of Midway: The Tide Turns

Admiral Isoruku Yamamoto.

Before Japan went to war with the United States, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander-in-chief of the Japanese navy, had correctly predicted its course. When the prime minister asked him about it in mid-1941, Yamamoto said, "I shall run wild considerably for the first six months or a year, but I have utterly no confidence for the second and third years."(21) He said this because in December 1941 the Japanese and US Pacific fleets were roughly the same size, but at the rate the Americans could build new ships, by the end of 1943 the American fleet would be 50 percent larger, and it would be more than twice as large by the end of 1944. And this was assuming that all the time the Germans would keep part of the American fleet busy in the Atlantic. What Japan needed to win the war was a battle that would hit the Americans hard enough to make them sue for peace. In other words, Yamamoto wanted another battle like Tsushima, where Japan had smashed the Russian fleet in 1905.

To pull off this kind of victory, Yamamoto would have to get as many enemy ships as possible to gather at one spot, and annihilate them there. He thought long and hard about where he could concentrate those ships, decided it would have to be a vital place the Americans felt they could not afford to lose, and the best candidate for such a target was Midway, one of the westernmost Hawaiian islands. We saw in the previous chapter that before the United States annexed Hawaii, it had claimed Midway because of its strategic location. If the battle succeeded, the American fleet would be wiped out, and Japan would gain an advance outpost in the central Pacific.

Well, Yamamoto’s staff did not like this plan at all; they wanted more small offensives in the southwest Pacific, with Samoa and Fiji as the next targets. Yamamoto’s response was that the Americans were not willing to fight hard to defend such peripheral places, so while attacks in that area would probably succeed, they would not catch many American ships that way. First he threatened to resign if his plan wasn’t accepted, then he promised to take Fiji and Samoa after winning at Midway; with those two moves, he won approval for the Midway operation.

To lure the Americans to Midway, Yamamoto committed nearly all of the Japanese navy to the north-central Pacific, grouped into eight different task forces. Three task forces went to Alaska instead of Midway, the idea being that they would confuse the Americans by creating a big diversion in the Aleutian Islands. One task force, made up of two light carriers, would stage a raid on Dutch Harbor, the American base in the Aleutians, on June 3, 1942. The other two task forces were troop transports and their escorts; they would succeed in taking two of the westernmost islands, Attu and Kiska, and hold them for a year.

Meanwhile, closer to Midway, two task forces carrying the troops that would take the island were approaching from the southwest. Behind these convoys came their escorts (two battleships, four cruisers and a light carrier), making up a third task force. As the Japanese wanted, these groups were detected by the Americans on June 3, and the American fleet quickly left Pearl Harbor to intercept them before they made landfall; planes launched from Midway bombed the troop convoys, but failed to do much damage. As this happened, the two strongest task forces rapidly closed in from the west; we shall call them the Strike Force and the Main Force to tell them apart. The Strike Force, commanded by Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, contained four fleet carriers, two battleships, one cruiser, twelve destroyers -- and most of the planes that Japan would use in the battle. Close behind the Strike Force followed the Main Force, which contained a total of 48 ships: two light carriers, five battleships, six cruisers and the fleet support vessels. Admiral Yamamoto would direct the whole operation from the Main Force’s newest and largest battleship, the Yamato. He and Nagumo would divide the Main Force between the Aleutians operation and the Strike Force, once they knew where the ships were needed the most.

One thing was clear, the Americans would have a hard time getting a fleet together to match all this. They didn’t even try to match the battleships. Of the eight battleships bombed by the Japanese at Pearl Harbor, only two, the Oklahoma and the Arizona, had been declared total losses; the other six had been repaired and were fit for active duty again. A seventh, the Mississippi, had been sent over from the American fleet in the Atlantic. But these capital ships were old and slow, compared with fleet carriers (the Mississippi had been built during World War I), so Admiral Nimitz sent them to the west coast of North America, to use for training, patrol and escort duties. Regarding fleet carriers, Nimitz had five as of April 1942: the Enterprise, Hornet, Lexington, Saratoga and Yorktown. A torpedo had damaged the Saratoga in January, and we saw already that the Lexington had been sunk in the Coral Sea; with the Saratoga and Yorktown undergoing repairs, only two carriers were available for Midway.

The biggest advantage Nimitz had was not in ships, but in information. In March Navy codebreakers had cracked the complex JN-25 code, used by the Japanese for their most secret communications. After this achievement, American naval personnel were able to intercept Japanese radio messages and find out when and where they were going to strike. Realizing there was no time to lose, Nimitz moved the Enterprise and Hornet to the northeast side of Midway at the beginning of June, and by working around the clock for three days, repair crews got a patched-up Yorktown battle-ready in time; it joined the other carriers on June 2. The Yorktown brought along some workmen to continue making repairs even while the battle went on.

Another factor that worked in the Americans’ favor was that the two Japanese fleet carriers that had taken part in the battle of the Coral Sea would not be present for this battle. Both the Shokaku and Zuikaku had gone straight back to Japan from the Coral Sea; the Shokaku needed extensive repairs, while the Zuikaku needed to replace the planes and pilots lost in the battle. Neither carrier was expected to be battle-ready again before July. Thus, for the battle of Midway, the ratio of fleet carriers was 4:3 in favor of the Japanese, but because Admiral Nagumo didn’t know the Yorktown was back, he thought he had a 4:2 advantage. Some historians have suggested that if the Shokaku’s aircraft and flight crews had been transferred to the Zuikaku, the Zuikaku would have been able to return to duty almost fully equipped. That would have given the Japanese a 5:3 advantage; could that have made a difference? It didn't happen because the Japanese, unlike the Americans, insisted that flight crews and their carriers must train and work together as a single unit.

All Japanese units were in their assigned positions when the battle began. The attacks on the Aleutians did not confuse the Americans; on the contrary, it told them that the intelligence gathered on the Japanese plan was correct. At 4 AM on June 4, Nagumo’s Strike Force launched 108 planes for a strike on Midway. However, the results of this bombing run were a disappointment, like the American bombing run on the troop convoys the day before. In this case, the Americans spotted two of the carriers before the planes arrived, and ordered all American planes on the ground to take off, so while the American planes did suffer heavy losses, they went down fighting. And the attacks on ground targets damaged, but did not destroy the airbase; the strike leader reported a second strike would be needed to neutralize defenses before the troop landing could begin.

Nagumo had held enough planes in reserve for a second strike, but Yamamoto’s plan called for using them against the American ships when they showed up, so they were armed with torpedoes for this task. At 7:15 AM he ordered that the torpedoes be removed, so that bombs could be put on the planes. While this work was still going on, the Midway-based bombers began attacking the Strike Force. The American torpedo bombers were so slow that flying them was basically a suicide mission, and Japanese fighters shot them down easily, while the high-altitude bombers simply missed their targets. At 8:20 AM, a scout plane messed up Nagumo’s plan as well, by reporting an American carrier, two hundred miles to the northeast. Therefore, Nagumo rescinded his order and told the flight mechanics to put the torpedoes back on the planes. Then when the planes that had carried out the first strike returned to the carriers, the Strike Force turned away from Midway and went forth to engage the enemy.

On the other side, Admiral Raymond Spruance, the commander of the Enterprise and Hornet, already knew there were Japanese ships ahead, and began launching his planes at 6 AM. Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher, still commanding the Yorktown, was sailing well behind the other carriers, so he waited until 8:30 to launch his planes. Because the Strike Force changed course between the two launchings, the Hornet’s dive bombers never found any targets, and they ran out of fuel before they could get back. The Hornet’s fifteen torpedo bombers reached the Strike Force at 9:25, but because they had the undivided attention of the Japanese fighters, they were all massacred; only one got close enough to drop a torpedo, and its pilot was the only survivor from the squadron. Then at 9:30 fourteen torpedo bombers from the Enterprise arrived, and the results were almost as bad; none hit any targets with their torpedoes, and only three survived the close encounter with the Japanese pilots. At 10 AM the last torpedo bomber squadron -- twelve planes from the Yorktown -- showed up, and for the Japanese pilots it was like shooting fish in a barrel; their fighters got them all.

If you are feeling sorry for the torpedo bomber pilots, rest assured; they did not die in vain. To aim at the torpedo bombers, the Japanese pilots had to fly their planes very low, at a level between the carrier flight decks and the ocean surface. This left the sky open above the carriers, and right after the last torpedo bombers began their attack runs, forty-seven dive bombers, from the Enterprise and Yorktown, arrived, 20,000 feet overhead. At 10:25 AM, the Americans had three of the fleet carriers, the Akagi, the Kaga and the Soryu, in their sights. Even worse, more than half of the Japanese planes -- the ones that were supposed to go after the American ships -- were on the carrier flight decks, getting ready to take off.

Having been taken by surprise, the Japanese carriers were disasters waiting to happen. Covering their wooden flight decks were planes loaded with fuel and ammunition, and there were unattached bombs and torpedoes lying around; it was dreadfully easy to set all this ablaze. Once the dive bombers hit the Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu, it only took five minutes to turn all three carriers into burning wrecks. By 10:30 AM the battle was as good as over.

The Japanese fleet carrier Akagi. This photo was taken in April 1942, two months before the battle of Midway.

Except that the Japanese were not yet ready to admit defeat. They had one fleet carrier left, the Hiryu, and at 11 AM this carrier’s planes took off and followed the retreating American planes. When they reached the Yorktown, the Japanese planes dropped three bombs, which did enough damage that Admiral Fletcher and his staff were persuaded to move to another ship, the heavy cruiser Astoria. Repair crews got to work immediately, and they did a good enough job that when the second wave of planes from the Hiryu arrived, two and a half hours after the first wave, the pilots didn’t recognize the Yorktown; they thought they were attacking a different, undamaged carrier. Two torpedo hits from the second wave caused the Yorktown to lose all power and lean 23 degrees to port; this time the whole crew abandoned ship.

The Yorktown’s planes landed on the Enterprise, and one of them managed to locate the Hiryu at 1:30 PM. Admiral Spruance responded by launching thirty-eight dive bombers, and at 5 PM they found the Hiryu. Though the Hiryu had a defensive screen of more than a dozen Zero fighters, she was ruined by four or five bombs, and the crew was evacuated.

Needless to say, Admiral Yamamoto was dismayed by the reports he received on the battle. On the evening of June 4 he considered attacking the Americans at night with the Main Force. If this had just been a battle of ships against ships, he would have had an overwhelming advantage in firepower; remember, the Americans didn’t have any battleships here. However, Spruance knew where the Main Force was, and suspected the Japanese might try this, so he only stayed around long enough to pick up the rest of the American planes before withdrawing to the east. Yamamoto did not find Spruance, and the next morning he realized that even his formidable Main Force was vulnerable, because he had hardly any aircraft left. No longer believing that victory was possible, Yamamoto ordered all remaining ships near Midway to return to the home ports they came from. Thus, the Main Force did not see any action in the battle.

On June 5, the Japanese scuttled what was left of the Hiryu, and on the 6th a submarine sank the Yorktown with torpedoes, while the Americans were trying to tow her away. However, Yamamoto lost ships and men even while retreating; two heavy cruisers collided and were drifting near Midway on June 6, when Spruance found them, sank one, and inflicted more damage on the other. That marked the end of the battle which Yamamoto had wanted so badly, but turned out completely different from what he had expected. In the Pacific and in the air above, the initiative now passed from the Japanese to the Americans.

The New Guinea Campaign, Part 1

After the battle of Midway, it was clear that the Japanese navy was overextended. Lousy security had given away the Japanese advantage before the battle, and it could not be recovered. Instead of the American fleet getting destroyed at Midway, it would grow larger every year, while the Japanese navy, staying about the same size under the best of circumstances, would be hard pressed to defend the huge portion of the world claimed by the Japanese empire. One consequence of the changing situation was that all plans for conquering New Caledonia, Fiji and Samoa were cancelled immediately after the battle; carrier-based airplanes were no longer available to support major amphibious operations.(22)

However, the army’s mood remained, "Let’s go hurt somebody." The Japanese army had not lost a battle yet, and it still felt that it would win in the end, if the soldiers never gave up. In April 1942 some of the troops that had been used to occupy Java were transferred to western (Dutch) New Guinea. Only a handful of Dutch soldiers were there to resist; those that weren’t captured immediately withdrew to the jungle, to begin a guerrilla campaign. On the west coast, the Japanese advanced as far as Frederik Hendrik Island (modern Pulau Yos Sudarso). The only Dutch community they did not take was Merauke, on the south coast; Australian forces would keep this city in Allied hands for the entire war. April also saw the capture of most of the north coast. Now the army wanted to make another effort to take Port Moresby, this time by marching across the Owen Stanley Mts., the east-west mountain range that forms the spine of New Guinea. Controlling Port Moresby was essential if they wanted to control the whole island, and taking it would also give Japan a base only 340 miles from Australia’s Cape York Peninsula. The possibility that Japan might do this prompted Australia to recall the troops it had sent to fight alongside the British in North Africa, because it looked like they would be needed to defend the Australian homeland.(23)

Australia held the whole eastern end of New Guinea, the "tail" of the island, so the Japanese plan called for landing troops on the northeast coast, halfway between Salamaua and Milne Bay, the bay on the tip of the "tail." They would take the towns of Buna and Gona, and then strike inland, using a 120-mile-long trail, the Kokoda Track, to go over the Owen Stanley Mts. and head straight for Port Moresby. To regain some of its lost honor, the navy was compelled to assist the operation, by taking the Allied airfields at Milne Bay.

The troop landings took place on July 21-22, 1942. But while Buna and Gona were captured easily, the trail proved to be narrower and more rugged than expected(24); it took until August 12 to seize the village of Kokoda, and the key mountain passes used by the trail. Near the end of August, Australian defenders took a stand at Isurava, and in a re-enactment of the famous battle of Thermopylae, they held off a larger Japanese force for four days. At Ioribaiwa Ridge the Japanese were close enough to see the lights of Port Moresby, just twenty-five miles away; here Australian reinforcements managed to halt their advance in mid-September. Then the Australian counterattack began on September 23, and the Japanese, now seriously short on supplies, withdrew the way they came.

Meanwhile at Milne Bay, the Japanese navy didn’t do any better than the army. They had 1,943 elite naval troops, not enough to take the airfields because at the last minute, Australian and American reinforcements built up the defending strength to 8,824. The battle for Milne Bay lasted two weeks, from August 25 to September 7, and when the Allies won, it was a morale-booster, for this was the first time Allied troops had won a decisive victory against the Japanese on land.

On the Kokoda Track, the Japanese turned around because they had orders to withdraw if they could not advance. The battle of Guadalcanal (see below) was going badly, and General Harukichi Hyakutake, the commander of the southwest Pacific campaigns, figured that Japan could not drive the Allies from New Guinea and Guadalcanal at the same time, so he chose to send all reinforcements to Guadalcanal. Still, the force on New Guinea made an orderly retreat; in early November they returned to Buna and Gona and dug in around these bases. The Allies now had two air-supported divisions, one Australian and one American, but they were unable to penetrate this combination of swamp and defensive perimeter. The American performance was especially poor, because most of the American troops were inexperienced, having only joined the army since the battle of Pearl Harbor. General MacArthur showed little sympathy for the hardship the troops were suffering; after the Japanese won a firefight, he put a new general in charge of the assault, Robert Eichelberger, and told him, "Bob, I want you to take Buna, or not come back alive . . . And that goes for your chief of staff, too." Because the defenders were doing their job better, it took persistence to get the results MacArthur wanted. The Australians overran Gona on December 9, while a combined frontal attack and flanking movement finally captured Buna on January 22, 1943.(25) The Japanese had lost 13,000 men and the Allies had lost 8,500 (2/3 of them Australian, the rest American); 27,000 cases of malaria had also been reported among the Allied troops. Consequently the Allied divisions were so battered that they had to take six months off, to rest, recuperate and replace their losses, before they would be ready for their next operation.

Guadalcanal

While Australian, American and Japanese soldiers fought over New Guinea, Admiral Nimitz planned Operation Watchtower, the first American offensive. First, he created a new military command. While he would continue to personally lead US naval forces in the Central and North Pacific, those forces south of the equator were now declared to be in the "South Pacific Area." The headquarters of the South Pacific command was established at Noumea, on New Caledonia; Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley would command the South Pacific ships, and they would cooperate with General MacArthur in driving the Japanese out of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

Next, Nimitz picked Tulagi, the small island captured just before the battle of the Coral Sea, as the target to liberate first. However, on June 8 the Japanese captured a nearby large island, Guadalcanal, and now they were building an airstrip on it. If completed, the airstrip would allow Japanese aircraft to cut the sea route between Australia and the United States. When air reconnaissance discovered the airstrip, Guadalcanal immediately became Operation Watchtower’s priority. And because Guadalcanal was the southernmost occupied island, taking it would give a signal that the rolling back of the Japanese Empire had begun.

On August 7, 1942, eight months to the day after the Pearl Harbor disaster, the US First Marine Division made landings on Guadalcanal and three smaller islands: Tulagi, Gavutu, and Florida Island. Three carriers provided air cover for the Marines, their planes fighting off Japanese planes launched from Rabaul. The Guadalcanal landing was next to the unfinished airstrip, so by August 8 it was captured (the Americans subsequently named it Henderson Field). Fighting was fierce on the other islands, but within twenty-four hours they were all taken, too.

This was a good start, but on August 8 the carriers left to resupply, and the following night, Japanese warships (seven cruisers and one destroyer) launched a surprise attack on the Allied ships (eight cruisers, fifteen destroyers and five minesweepers) protecting the beachheads. This clash, the battle of Savo Island, went very well for the Japanese; their cruisers suffered only light damage, while four Allied cruisers were sunk. The only thing that saved the troop transports and the Marines already ashore was that the Japanese thought the carriers were still around, so they withdrew before the sun rose. The battle also meant the Americans had lost control of the waters around Guadalcanal; that is the main reason why it took them six months to expel the Japanese from the island. Now the Japanese would regularly send convoys from Bougainville at dusk, going down the channel between the Solomon Islands (today this is the New Georgia Sound, but during the war it was called "the Slot"). At Guadalcanal the "Tokyo Night Express" would unload supplies and reinforcements, and maybe bombard the American positions, but because they only had air cover around Rabaul (the Americans soon completed Henderson Field and put it to use for their actions), they had to get back to the northern Solomons before dawn.

The first Japanese reinforcements landed on August 18, twenty miles east of Henderson Field; they tried to take the airstrip on the 21st but were driven back into the sea. Then another convoy was sent from Truk Lagoon, a major Japanese base in Micronesia, this time supported by two battleships, sixteen cruisers, twenty-five destroyers, and three carriers: the Shokaku, the Zuikaku, and the light carrier Ryujo. On the other side, Admiral Fletcher was approaching the Solomons from the east with a much smaller task force: three carriers (the Enterprise, Saratoga and Wasp), one battleship, four cruisers and eleven destroyers. On August 23 they spotted the Japanese convoy. Fletcher launched an airstrike at once, and the convoy turned around to dodge it. After the planes returned, Fletcher released one of his carriers, the Wasp, to go refuel, so it missed the battle which came next.

That night, Admiral Nagumo ordered the Ryujo to go on to Guadalcanal with three escort ships and attack Henderson Field at dawn. The idea here was that the Ryujo would serve as bait; if any Allied ships attacked her, the other two carriers, following along behind, would launch their planes at the Allied ships. Thus, the battle of the Eastern Solomons began in earnest on August 24. The American carriers took the bait, sinking the Ryujo with the Saratoga’s planes, and when the Japanese stuck back, they dropped three bombs on the Enterprise, heavily damaging that carrier, but not putting her out of action. After that, the carriers from both sides pulled out, but there was more fighting on the 25th, this time between the Japanese ships that stayed behind and the American planes based at Henderson Field and Espiritu Santo; the Americans managed to sink a troop transport and a destroyer before the rest of the ships withdrew. Both sides claimed victory afterwards; the Japanese felt they had won because the Americans completely missed their fleet carriers, but this was the last time Japanese ships approached Guadalcanal during daylight hours.

The Japanese reinforcements delivered to Guadalcanal made another attempt to take Henderson Field on September 12, and launched two more attacks on October 23-24. However, the American force on the island was larger, and the October attacks were not coordinated, so the Americans won each time. At sea another US carrier, the Hornet, arrived in the South Pacific, but then the Americans lost their carrier advantage; the Saratoga was damaged by a torpedo (again) on August 31, and a submarine sank the Wasp with three torpedoes on September 14. On the night of October 11-12, there was a clash between opposing ships off Cape Esperance, at Guadalcanal’s northern tip; the Americans lost a destroyer while the Japanese lost a destroyer and a cruiser. A few days after that, Admiral Nimitz decided that Admiral Ghormley was too weak and indecisive, and replaced the South Pacific commander with Admiral William Halsey. "Bull" Halsey should have been at the battle of Midway, but missed it due to a serious illness (Spruance took his place); the aggressive strategies he showed for the rest of the war can be seen as a way of making up for his mid-1942 absence.

The fourth carrier-vs.-carrier battle of the war was the battle of Santa Cruz. This time the Japanese tried to break the Guadalcanal stalemate -- where the Americans won all the land battles and the Japanese replaced their losses -- by trying to get rid of the American carriers first. The task force that headed for the southern Solomon Islands in late October was the largest Yamamoto had assembled since the battle of Midway: three fleet carriers, one light carrier, four battleships, ten cruisers, and twenty-two destroyers. Against this, the American force in the area was roughly half as strong: two carriers, one battleship, six cruisers and fourteen destroyers. On the morning of October 26, the two forces spotted each other near the Santa Cruz Islands, and rushed to engage. It turned out to be mainly a rematch of the carriers, as the Shokaku, Zuikaku, and the light carrier Zuiho traded airstrikes with the Enterprise and Hornet. Because the Enterprise was hidden by a squall for the first two hours, she suffered much like she did in the last battle, taking two bomb hits but surviving. The Hornet did not fare as well; three bomb and two torpedo hits turned her into a burning hulk, forcing the crew to abandon ship, four more Japanese torpedoes sunk the Hornet later. In response, the American planes inflicted heavy damage on the Shokaku and Zuiho, but those carriers lived to fight another day. Since the Japanese did not lose any ships, they claimed victory. They also had the satisfaction of knowing that now they had sunk the same number of fleet carriers as the Americans had (4), and the Americans only had one damaged carrier left in the whole Pacific, the Enterprise. However, the Japanese had also lost more planes and flight crews than the Americans, meaning their carriers would again have to return to Japan for replacements.

Back on Guadalcanal, the Japanese were determined to hold as much of the island as they could, whether they had Henderson Field or not. Three offshore naval battles in November resulted in near-equal results: the Japanese lost two battleships and four destroyers, compared with three cruisers and seven destroyers lost by the Americans. In December the Japanese navy decided they were getting nowhere and recommended abandoning the island; the army and the emperor agreed before the end of the month. Using the "Tokyo Night Express," they picked up all remaining troops by February 9, 1943.

Japan had committed 36,200 men to the Guadalcanal campaign, of which 10,652 were evacuated at the end. The Allied losses weren’t as heavy; of the 60,000 they landed, 1,600 were killed in action, 4,200 wounded, and 5,500 dead from tropical diseases like malaria. Guadalcanal was a great psychological victory for the Allies as well as a physical one. It proved the Japanese army was beatable, just as Midway did with the Japanese navy; it took away an important airbase before the enemy could use it; and the Americans learned how to make amphibious assaults and fight in the jungle, things they would be doing regularly for the rest of the war.(26)

The New Guinea Campaign, Part 2

The siege and taking of Buna was an important landmark in the liberation of New Guinea, but General MacArthur had a long way to go to finish the job. Three factors made the Allied advance so painfully slow: New Guinea’s terrible terrain, which we have mentioned more than once in this narrative already; Japanese determination to defend most territories for as long as humanly possible; and the fact that new airfields had to be built every time ground forces advanced more than a few miles, to maintain air cover and provide an alternative to ground transportation. And because it was so long and inglorious, having been fought "beyond the pale of civilization," the New Guinea campaign was largely forgotten after it ended; ask somebody familiar with World War II to name some of the Pacific battles, and he is likely to mention Pearl Harbor, Corregidor, Tarawa or Iwo Jima -- but not any New Guinea battles.(27)

When the Allies recovered Gona and Buna, the Japanese evacuated their survivors to the bases they had on the northeast coast, at Lae and Salamaua. Then Japanese strategists remembered that when they had captured Salamaua in early 1942, they had not paid any attention to Wau, a town thirty miles to the southwest. Wau had been the site of a gold rush in the 1920s and 30s, and an airfield had been built there to handle the gold traffic. Capturing that airfield would permit air cover for the troops, the next time the Japanese went after Port Moresby. Accordingly, a ground force marched on Wau, but the Austalians managed to turn it back (the battle of Wau, January 29-31, 1943).

The Japanese were not ready to give up on New Guinea yet, and thought that if they reinforced their garrisons, they could make another attempt to capture Wau. Allied cryptographers decoded and translated Japanese naval messages that told of a convoy going from Rabaul to Lae, under the cover of bad weather: eight transports carrying 6,900 troops, escorted by eight destroyers and a hundred aircraft. MacArthur’s air commander, General George C. Kenney, sent every available plane to intercept the convoy, resulting in the battle of the Bismarck Sea (March 2-4). Attacks from B-17 and B-25 bombers sank all eight transports and four of the destroyers. 3,900 Japanese troops survived, but most had to be rescued and returned to Rabaul; only 1,200 made it to Lae.

At the same time as the battle of the Bismarck Sea, Allied airstrikes began to neutralize the main Japanese airfield at Lae. On the other side, Admiral Yamamoto promised the emperor that he would also launch a series of massive airstrikes, to retaliate for Japanese defeats suffered over the past few months. While these attacks hit targets in the Solomon Islands, Milne Bay and Port Moresby, the main casualty was the admiral himself. Yamamoto made an inspection tour of the New Guinea-Solomon Islands area in April 1943, and by intercepting another message using the code the Americans had broken, the Allies learned his itinerary, and set up an ambush to get him. They succeeded on April 18, shooting down his plane over Bougainville. His successor, Admiral Mineichi Koga, bolstered the defense of the northern Solomons by transferring all carrier groups to Rabaul, though this meant not all of the pilots could complete their training, and it weakened air defenses elsewhere. Koga was in turn killed eleven months later, when his plane flew into a typhoon between Palau and Mindanao and crashed in the sea.

On April 22, Australia began to recover the northeast, by having ground forces attack the Japanese defense perimeter around Salamaua. Though the Americans joined them later, they faced more slow going; it took until mid-July before the Allies began to scale the mountain overlooking Salamaua, Mount Tambu, and it took until mid-August to drive the Japanese off it. Then additional fronts were opened against Lae, with an amphibious landing on the coast east of Lae, and an airborne landing 30 miles inland, at Nadzab (September 4-6). They finally retook Salamaua on September 11, and Lae on September 15.

Next above Lae is the Huon Peninsula, which juts into the sea, pointing toward New Britain, and marking the junction between New Guinea’s northern and eastern coasts. An amphibious landing on the peninsula’s eastern tip captured it quickly enough (September 22), but because of more jungle fighting, the American and Australian troops took three and a half months -- until January 1944 -- to advance sixty miles to Sio, the town on the peninsula’s north side. A few hundred miles to the east, American naval and marine forces had spent most of 1943 advancing up the Solomon Islands in a parallel course (see the next section). By the beginning of 1944, they had just reached New Britain, though Rabaul, the "Gibraltar of the South Pacific," remained in Japanese hands. How the Allies dealt with Rabaul decided what they did next on New Guinea as well as in the Pacific Ocean.

Climbing the Solomon Islands, and Part 3 of the New Guinea Campaign

None of the other Solomon Islands took as long to liberate as Guadalcanal did. Still, they kept Admiral Halsey busy for most of 1943. For four months after Guadalcanal, there was a pause as US forces got ready for the next big move. The only activity during this time was an unopposed landing on the Russell Islands, between Guadalcanal and New Georgia (Operation Cleanslate, February 21), and the previously mentioned killing of Admiral Yamamoto.

US forces began moving into the central Solomons with Operation Toenail, landing on New Georgia on June 21. Assaults on the surrounding islands quickly followed in early July. New Georgia contained the most important Japanese airfield south of Rabaul, and it was fiercely defended on land and sea; resistance did not end until August 25. New Zealand troops joined the Americans in mid-September, to help clear the Japanese from the northernmost islands taken so far, Vella Lavella and Kolombangara.(28)

October 27 saw a New Zealand brigade attack the Treasury Islands (Operation Goodtime), and a US Marine battalion raid Choiseul (Operation Blissful). Those actions paved the way for stepping onto the top rung of Solomons "ladder," Bougainville (Operation Cherryblossom, begun November 1). This was close enough to Rabaul for the Japanese to stage counterattacks, the battle of Empress Augusta Bay (November 7), and the battle of "Hellzapoppin Ridge" on land (December 12-24). By the end of 1943 much of Bougainville was still in Japanese hands, but the Allies had three airfields available, so they could go on to New Britain. The remaining Japanese were bottled up at a safe distance from the airfields, and left isolated for the rest of the war.

MacArthur called his plan for New Britain "Operation Cartwheel," and it began with two landings, on the southwest coast (Arawe, December 15) and the northwest coast (Cape Gloucester, December 26). Not only did Japanese defenders fight back, but the Americans arrived during the rainy season, meaning they experienced jungle warfare at its worst. It took until mid-January to capture the Cape Gloucester airfield and establish a defensive perimeter around it. Efforts were also made to surround and blockade the ultimate objective on New Britain, namely Rabaul. In February 1944, New Zealand forces captured the Green Islands, east of both New Britain and New Ireland, while the Americans captured the Admiralty Islands in February, and the St. Matthias Group in March.

At this point almost half of New Britain had been taken by the Allies. But now they took a second look at what taking Rabaul would cost. Over the past two years, Japan had stationed as many as 100,000 personnel here, and though recent bombing runs on the base had persuaded Tokyo to pull out its air and naval groups, there were probably enough troops remaining to make an assault on Rabaul the largest battle of the Pacific War to date. At their Quebec conference in 1943, President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had decided that it would be better to neutralize Rabaul than to try beating it to a bloody pulp. MacArthur would have preferred taking Rabaul, but he had his orders, so once he was sure that the Japanese troops at Rabaul and on New Ireland could not break out of the Allied blockade, he bypassed them and turned his attention back to liberating New Guinea.

After the liberation of the Huon peninsula, further Allied advances on the north coast of New Guinea were blocked by a Japanese army in the town of Wewak. MacArthur chose to go around that army, instead of hitting it; on April 22, 1944 he landed troops at Aitape, Vanimo, and Hollandia. The landings achieved complete surprise, and because Hollandia (modern Jayapura) was on the Dutch half of the island, taking it ruined Japanese plans for defending western New Guinea.(29) The combination of wartime airpower, seapower and manpower allowed MacArthur’s next step toward Tokyo to be a larger one than expected.

There were more battles in northern and western New Guinea after Hollandia, going on all the way until the end of the war. We will be skipping the details here for the following reasons:

- None of them were very large, compared with the battles on other fronts.

- They had no effect on the war anywhere else, since they involved Japanese soldiers in isolated pockets vs. Allied efforts to reduce those pockets.

- The Allies won all of them at little cost.

The Pacific Drive

The awesome industrial strength of the United States began making itself felt in 1943. There were thirty-three aircraft carriers (twenty-four fleet and nine light) under construction in US shipyards; in the middle of the year, three fleet and five light carriers were completed and delivered to the fleet of Admiral Nimitz. This meant the fleet could bring up to 600 planes on its campaigns, enough for any battle on the smaller islands or against any enemy fleet.

The US Navy gained another advantage in the same year, that was far less visible. One reason why the Japanese did so well in 1941 and 1942 was because they had better torpedoes and better vehicles to deliver them; American torpedoes were less reliable and less likely to hit the target. But by late 1943, those problems had been fixed, and now American submarines, the so-called "Silent Service," became the Navy’s secret weapon. In 1943 alone, subs would be responsible for the sinking of 22 Japanese warships and 296 merchant ships; Japan learned the hard way that it wasn’t doing enough to protect its ships at sea. Still, this success came at a cost; one fourth of the subs did not make it to the end of the war, and the Navy only took volunteers for submarine duty, to keep morale up.

Nimitz would continue to provide men, ships and planes to MacArthur and Halsey as they needed them, but with his new ships he could open up another offensive in the central Pacific, a westward advance from Hawaii to Asia. If this campaign succeeded, it would clear the Japanese out of Micronesia. Because the Japanese were now running low on ships and aircraft everywhere, all they could do to defend these islands was strengthen the garrisons on them, in the hope that they would be strong enough to defeat the Allied assaults by themselves, or at least slow the Allies down until victory could be achieved elsewhere.

The two main Allied counter-offensives in the Pacific, led by General Douglas MacArthur (from the south) and Admiral Chester Nimitz (from the southeast).

The first islands encountered by the westbound American fleet were the Gilberts. Japan only had two strongpoints in this archipelago, Makin and Tarawa; Nimitz landed troops on the beaches of both atolls on November 20, 1943. The Americans lost a light carrier to a torpedo at Makin, but otherwise casualties from that battle weren’t very high. Tarawa, however, saw US Marines having a hard time getting past the coral reefs in order to make landings while under fire, and the main strongpoint, Betio, had hundreds of pillboxes made of concrete and coral, with steel beams and coconut logs making up the rest of this fortress. Though the Americans bombed and shelled Betio before trying to take it with Marines, its well-supplied garrison of 4,700 Japanese fanatically fought almost to the last man.(30) It ended up being a four-day battle, one of the bloodiest of the entire war, with a suicide charge by the Japanese at the end; 1,700 Americans were killed, and all but 17 of the Japanese defenders died. Americans called this battle "Terrible Tarawa," not knowing there would be more island battles like it later. Afterwards, Navy Seebees came ashore with their bulldozers and promptly began constructing a new base for use in the next battle, in the Marshall Islands.

US Marines on Tarawa.

The Marshall Islands were the first place the Allies attacked that had been Japanese territory before the war. The first island American troops landed on was Majuro, on January 30, 1944, but there was no battle; the Japanese had evacuated Majuro a year earlier, leaving a single Japanese warrant officer as the caretaker. Majuro thus became the new capital of Marshall Islands (previously the capital had been on Jaluit). That left six atolls in the Marshall Islands with Japanese garrisons, and now that Nimitz had perfected his "island-hopping" strategy, he would go after two of them, Kwajalein and Eniwetok, and ignore the rest (Wotje, Mili, Maloelap, and Jaluit).

Kwajalein is the world’s largest coral atoll: 66 miles long, 18 miles wide, and enclosing a lagoon with an area of 839 square miles. After the experience on Tarawa, Nimitz took no chances; before the first troop transport landed, on February 1, American ships and planes shelled/dropped 15,000 tons of explosives on Kwajalein, and Navy frogmen blasted pathways through the coral reefs. When the soldiers arrived, Kwajalein was a mass of dust-covered rubble, and one serviceman remarked that "the entire island looked as if it had been picked up 20,000 feet and then dropped." Japanese soldiers fought back savagely for three days, but all the preliminary bombardment did its work; only 348 Americans were killed, while among the 8,000 Japanese defenders, only 253 lived to be captured.

The success at Kwajalein encouraged Nimitz to move up the schedule for attacking Eniwetok, from May 1 to February 17. This time time the battle lasted for six days, until February 23, though the Japanese garrison here was smaller. Again there was a heavy bombardment at the beginning, and American casualties were relatively light: 313 Americans killed, as opposed to 3,380 Japanese killed and 105 captured. As for the unconquered Marshall Islands, they were simply bypassed. Lacking air and sea power, and under orders from Tokyo to not surrender, the garrisons on those islands were left behind as helpless spectators. Because there was not enough land on the islands to grow the food the garrisons needed, more than half of their soldiers died from starvation or disease before the war ended.

Next, after the Marshalls came the Caroline Islands. Here the strongpoints were Pohnpei in the east, Truk Lagoon in the middle of the archipelago, and Yap and Ulithi Atoll in the west. Truk was especially formidable; Japan had heavily fortified it, in violation of the League of Nations rules concerning the management of mandated territories. By the time the war began, it was the command center and the most important Japanese base in the central Pacific; the only stronger base was Pearl Harbor. So before trying to take any of the Caroline Islands, Nimitz sent a fleet to soften up Truk, an action called "Operation Hailstone" (February 17-18, 1944). In the fleet were eight carriers (five fleet, three light), seven battleships, forty-five other surface warships, ten submarines, and more than five hundred planes. A week earlier, the Japanese, expecting a Pearl Harbor-like assault, had withdrawn their carriers, battleships and heavy cruisers from Truk, so while quite a few ships were sunk by the attacking force, they were small and expendable, compared with those that got away. The attack kept the Japanese from sending reinforcements to the battle of Eniwetok, which was going on at the same time. Follow-up carrier attacks on April 30 and May 1 took out the remaining planes and their fuel supply. With that, Truk’s role as an important base was over.(31) Then, following the same thinking that had been used for Rabaul, when the actual invasion fleet entered the Caroline Islands, it bypassed Pohnpei, Truk and Yap, going straight to the Mariana Islands instead.

The Last Carrier vs. Carrier Battle

For the Japanese, the Allied strategy was obvious. While Nimitz was leading his drive from the east, MacArthur was getting ready to strike from the south, now that the New Guinea campaign had reached the mopping-up stage. If Nimitz succeeded, he would cut the Japanese empire in two; if MacArthur succeeded, he would take away the Southeast Asian conquests, which Japan valued more than the Pacific islands that have been fought over so much in this narrative. Both offensives had to be stopped, or the war would be lost.

The clash both sides were expecting came in June 1944, when Nimitz moved against the Marianas. He was eager to recover Guam because it had been a US territory before the war, while his Japanese counterpart, Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, decided this would be the place for the Kantai Kessen (decisive battle) against the Americans. Admiral Spruance was the man on the spot commanding the American forces, which were divided into two fleets; between them the fleets had more than 600 ships and 128,000 men. One fleet carried the troops to be used in the landings on the islands, plus seven converted merchant ships, called escort carriers, to provide air cover. The other fleet brought most of the warships and most of the planes, 956 of them, divided between seven fleet and eight light carriers.

On the other side, Japan had 71,000 soldiers concentrated on three of the Mariana Islands: Guam, Saipan, and Tinian. Ozawa’s fleet was smaller, too; 90 ships led by five fleet and four light carriers, carrying 450 planes. When Ozawa heard the Americans were coming, most of this fleet was anchored at Tawitawi, in the southwest corner of the Philippines. However, there were 300 more planes in the Marianas to help even the odds. Also, the Japanese planes had a longer range, so the first airstrike made would be theirs. All things considered, the battle for the Marianas was set up like Midway in reverse, and Ozawa’s hope was that it would work out the same way, with victory going to the smaller fleet with land-based planes.

Spruance made the first move, with a bombardment of Saipan on June 13, and landings on June 15. The Japanese garrison on Saipan had no chance of winning without the help of outside forces, but they resisted bitterly anyhow. The toughness of the fight showed in the names Americans gave to various places on the island (e.g., Hell's Pocket, Purple Heart Ridge and Death Valley). On July 7 the remaining Japanese troops staged a suicide charge, in which even their wounded participated. By the time resistance ended, on July 9, almost 3,000 Americans and 29,000 Japanese were dead. Among the latter was Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, the former naval commander at the battle of Pearl Harbor. He had been transferred to Saipan after failing to win at Midway and Guadalcanal, and committed suicide when he saw this battle was lost, too. And the loss of Saipan was a bad enough defeat that it caused the Japanese prime minister, Hideki Tojo, to resign.

Meanwhile, the Japanese and American fleets met in the Philippine Sea, the part of the Pacific between the Philippines and the Marianas. Because of the range advantage mentioned above, Japanese reconnaissance planes spotted the American ships first, on the evening of June 18. The next morning Ozawa launched four airstrikes, using a total of 304 planes. The American planes could not find the Japanese ships, and thus could not hit back -- but American radar was good enough to detect the Japanese planes from 150 miles away. In addition to the American fleet being larger and having better radar, the aircraft were much improved from previous battles, and their crews were more experienced. Thus, American planes intercepted these attack waves long before they reached their targets and blasted them out of the sky; the only hit scored by the Japanese planes was a bomb dropped on a battleship, the USS South Dakota. In history texts, this battle is called the battle of the Philippine Sea, but American pilots had their own name for it -- "the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot!" By the end of the day, the Japanese lost 346 planes (218 from the carriers, the rest from the Marianas), while the Americans lost 30 planes. Finally, American submarines managed to locate and sink two Japanese fleet carriers, the brand-new Taiho and the veteran Shokaku.

The second day of the battle (June 20) began with American aircraft looking for the Japanese fleet, which they spotted in mid-afternoon. American fighters and bombers took off in pursuit, reached the fleet at sundown, penetrated the fleet’s air cover, and managed to sink two tankers and one more fleet carrier, the Hiyo; six other ships were also damaged. Ozawa then withdrew to Okinawa under cover of darkness, and the battle was over.

Afterwards, the Americans saw the battle as a disappointment, because most of the Japanese ships got away. However, subsequent events showed it was as crushing a victory as Midway had been. Altogether the Japanese lost between 550 and 645 aircraft, a loss that was not only devastating, but at this late date, irreplaceable. Without their planes, the surviving carriers were glorified barges, and the Japanese could no longer prevent Allied ships and aircraft from entering Japan’s home waters. On the other side, most of the 123 American planes lost were the result of ditching in the sea after running out of fuel, or crashes from attempted night landings on carrier decks.

With the Japanese fleet beaten off, American attention returned to the Marianas. US Marine and Army troops landed on Guam on July 21, and on Tinian on July 24-25. Again furious Japanese counter-attacks failed to drive the Americans back into the sea, and though neither island had a garrison as large as the one on Saipan, another 3,000 Americans were killed on Guam. Organized Japanese resistance ended August 1 on Tinian, and August 10 on Guam.(32) Afterwards, airfields were constructed on Saipan and Tinian for long-range B-29 bombers, which would drop bombs on the Japanese home islands for the rest of the war.

The End of the War is in Sight

While the liberation of the Marianas was underway, General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz met with President Roosevelt, and they agreed to modify the Allied strategy; now MacArthur, Halsey and Nimitz would pool their resources in an all-out campaign to take back the Philippines. In men and materiel, this force would be even larger than the one used in the Marianas, so several advance bases would be needed. Accordingly, on July 30, 1944, MacArthur sent an amphibious force 200 miles from his most advanced position on New Guinea to take Cape Sansapor, on the Vogelkop peninsula (the "Bird’s Head" of northwest New Guinea). Next came a landing on Morotai in the northern Moluccas (September 15), which also isolated a Japanese naval base on nearby Halmahera. These moves put MacArthur directly south of Mindanao, the second largest island in the Philippines.

Nimitz got ready for the Philippine campaign by going for some western Micronesian islands that had been bypassed previously. In the Palau archipelago, these were Angaur and Peleliu. Peleliu had a large Japanese garrison and was fortified with many caves and rock formations; the commander of the Marine division used in the landing predicted the island would be secured in four days, but it took two and a half months (September 15-November 27), with more than 2,000 Americans and 10,000 Japanese killed. However, there weren’t any civilian casualties, because the local civilians were evacuated to nearby islands. Because Peleliu is a tiny island, at five square miles, you have to admit that taking it was a waste of lives, equipment and time. Angaur wasn’t so tough by comparison, because it had a smaller garrison; it was taken with 260 Americans and 1,350 Japanese killed (September 17-October 22). Ulithi atoll, in the western Caroline Islands, was found to be deserted when troops landed there on September 23; this was the most useful place captured in the Palau campaign, because like Kwajalein, the atoll enclosed a very large lagoon that was soon converted into a naval base.

A sign left by the first Americans on Peleliu, warning the rest of danger ahead.

At this point, the battle for the Philippines began. As the forces of the United States and its Allied partners closed in on Japan, the theater of war left the region we have defined as the South Pacific. The final ten months of World War II’s Pacific conflict (October 1944-August 1945) took place in Southeast Asia, China, and territories held by Japan before the twentieth century, like Iwo Jima. If you want to read how the last battles turned out, click on the links below to go to the pages where those battles are covered:

- The liberation of the Philippines

- Operation Ichigo, in China

- Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and the endgame in Japan itself

This is the end of Chapter 4.

FOOTNOTES

15. The fall of France meant that French citizens in the overseas colonies had to choose which side to give their allegiance to. French Indochina went with the Vichy French government, the puppet regime installed by the Nazis. However, the South Pacific colonies, New Caledonia and French Polynesia, backed Charles de Gaulle’s Free French movement, which continued the struggle against the Axis. Japan considered taking those islands, but Japanese forces were stopped before they got close enough to attack. Because of the need for cooperation, during the war the borders between territories held by the five Allied nations in the Pacific (Australia, the Free French, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and United States) were practically nonexistent.

16. During World War II, aircraft carriers came in two sizes. Both Japanese and American fleet carriers were as big as battleships, and carried around 75 aircraft each, while light carriers carried half as many planes. The three American carriers available in 1941 were all fleet carriers. When the US started building light carriers, they used cruiser hulls, making them fast enough to keep up with other ships. Japanese light carriers, however, were constructed by converting non-warships, and because they were slower, they usually operated independently. Also, at this stage, Japanese carriers had wooden flight decks, making them more vulnerable to fire than carriers with steel or aluminum flight decks, built later on.

17. The Japanese never got around to taking the Ellice Islands, though, so that island chain remained in Allied hands for the whole war.

18. On the night of May 31, 1942, three Japanese mini-submarines entered Sydney's harbor. They succeeded in sinking a converted ferry, the HMAS Kuttabul, killing 21 sailors. In the battle that followed, the crews of the mini-subs scuttled their vessels and committed suicide; one of the mini-subs was not found until 2006. Incidentally, other mini-subs like these were used in a raid on Madagascar at the same time. Then in early June, regular-sized Japanese submarines off the coast of New South Wales sank three Allied merchant ships, killing 50 sailors, and bombarded Sydney and Newcastle.

Overall, Australia suffered far less casualties during World War II than it had in World War I: 27,000 killed, 23,000 wounded. Still, the Aussies found World War II more emotionally draining, because nobody threatened to invade the Australian homeland in World War I, while for part of 1942 it looked like the Japanese would attempt an invasion.

19. While MacArthur had a good relationship with the prime minister at the time, John Curtin, many Australians resented the idea that a foreign general would be leading them in the battles. Because the Australians knew that the Americans had saved them, and not the British, their wartime partnership with the Americans marked the end of Australia’s special relationship with Britain. Aussies still get along with the mother country today, but they are more likely to see the United States as their best friend abroad. Likewise, on the other side of the Pacific, it is hard to find a modern-day American who doesn’t like Australia.

20. The Japanese got another message that they needed to do something about American aircraft carriers on April 18, when Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle used bombers launched from the USS Hornet to stage the first American air raid on Tokyo.

21. Harry A. Gailey, The War in the Pacific: From Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay, New York, Presidio Press, copyright 1995. p.68.

22. Fiji and Samoa enjoyed a wartime economic boom, because they were the closest important islands to the war zone that weren’t attacked. A lot of men stopped on those islands, either going between the United States and Australia, or on their way to fight in the Solomon Islands or New Guinea, and the natives were happy to do business with them during these stopovers. A garrison of American troops was stationed in Western Samoa during the war, and it improved life for the natives by building roads and an airport. Also, 8,000 Fijians were recruited to fight the Japanese in the Solomon Islands campaign, and a hundred were recruited for service in Europe.

However, Japan could still engage in minor amphibious operations. One was the occupation of phosphate-rich Nauru and Ocean Island. Originally planned for May 1942, the invasion was postponed by the battle of the Coral Sea, and the unopposed landings finally took place on August 29 (Nauru) and 30 (Ocean Island). Afterwards the Japanese established a strong base on Nauru, and because the Allies decided to bypass Nauru instead of retaking it, Japan held both islands until the end of the war. Today the base is Nauru International Airport, but Nauruans are not proud of this achievement, because the Japanese built it by using the local population as forced labor. During the occupation, to deal with overcrowding and food shortages, 1,200 Nauruans and 600 Banabans, more than half of the natives, were deported to Truk and Tarawa, but since a larger number of soldiers and workers were brought in, living conditions did not improve, and while the natives were returned after the war, hundreds did not live long enough to come back. After the war, most of the Banabans were resettled on Rabi in Fiji, because of the devastation caused by phosphate mining; more about that in the next chapter.

23. However, the New Zealanders stayed in North Africa, finishing that campaign and going on to fight alongside the British in Italy. The picture below shows the 28th Battalion, a Maori unit, performing a haka in Egypt (see Chapter 3, footnote #33).

24. The Owen Stanley Mountains have peaks towering as much as 13,000 ft. above sea level; the highest point reached by the Kokoda Track is 7,380 ft. And because the trail goes through jungle all the way, those using it also have to deal with the jungle environment’s hazards: heat, torrential rains, tough plants, nasty animals, diseases like malaria, etc. Australia made a movie about this campaign in 2006, Kokoda: 39th Battalion.

25. You can see that MacArthur was growing more confident, and his position was growing more secure, because he moved his headquarters more than once to get closer to the action. When he first arrived in Australia, he set up the HQ in Melbourne; with the start of the Papuan campaign in July 1942, he moved it to Brisbane, and then in November he moved it to Port Moresby.

26. Before 1942, the British colonial government for the Solomon Islands was based on Tulagi. After the war the capital was moved to Honiara, on Guadalcanal, to take advantage of the infrastructure left behind by the US military. In fact, Honiara remained the capital after independence came.

27. Well, present-day Papua New Guinea remembers the battles. July 23, the anniversary of the first clash between Papuan and Japanese units in 1942, is a national holiday, Remembrance Day, where the Papuans honor their soldiers, including those who served in the Australian armed forces before independence. Australia began recruiting native soldiers in 1940, as the Pacific Islands Regiment (PIR); by the end of the war more than 3,500 had served in its ranks. Because they knew the land well, natives gained a reputation as fearsome jungle fighters, killing some 2,200 Japanese while only losing 65 of their own men. Natives also noted that their relationship with non-Papuans had changed; the Australian army treated them better than the Germans, Dutch, Japanese, and even pre-war Australians had.

28. New Zealand was not left out, when the Americans and Australians began working together. From mid-1942 to mid-1944, while there were battles to be fought south of the equator, between 15,000 and 45,000 American troops were stationed in New Zealand, usually at camps in Auckland and Wellington.