| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of the South Pacific

Chapter 3: Pulled Into the Modern World

1781 to 1914

Part I

| Botany Bay | |

| Mutiny on the Bounty | |

| New Holland Becomes Australia | |

| The Impact of Western Contact | |

| Unrest In the Islands | |

| Kamehameha the Great | |

| Australia Developing | |

| The Last of the Tasmanians |

Part II

Part III

| Tonga: The Restored Monarchy | |

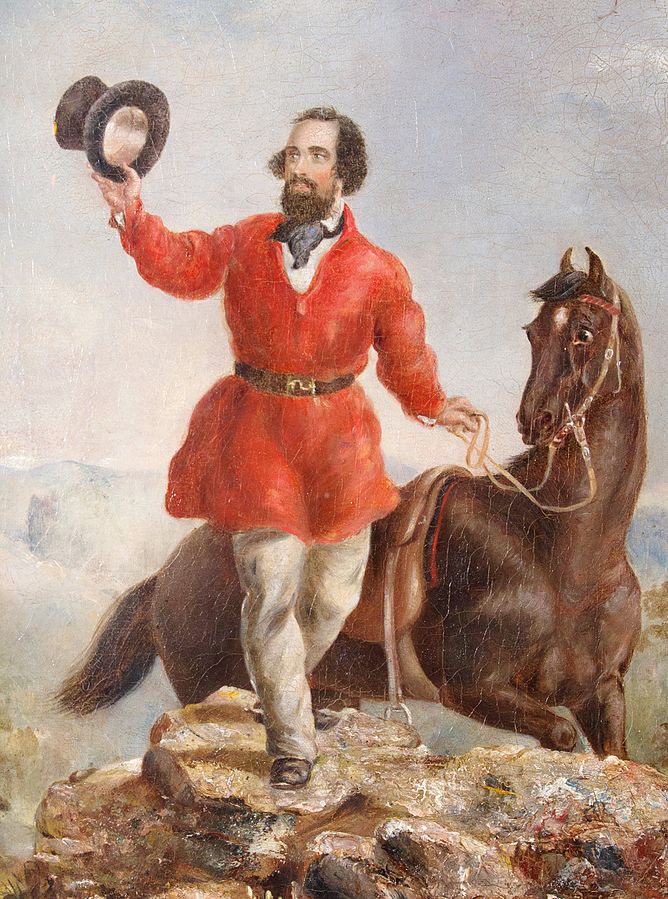

| Cakobau Unites and Delivers Fiji to Britain | |

| The Unification and Division of Samoa | |

| Taming the Outback | |

Part IV

| Dividing What's Left | |

| Hawaii, USA | |

| America's Imperialist Adventure | |

| Australia: Six Colonies = One Commonwealth | |

| New Zealand Follows a Different Drummer |

Britain Claims New Zealand

Unlike Australia, we do not have an exact date for when the European colonization of New Zealand began. Although traders, sealers and whalers started coming soon after the Cook expeditions, in the 1780s and 1790s, and they established stations to promote their businesses, they did not plan on staying there permanently. And the Maori did not see these Pakeha (Europeans) as a threat for the same reason. In fact, the normally-bellicose Maori were willing to trade. When they acquired pigs and potatoes from the Europeans, they no longer had to suffer from food shortages, and began raising these foodstuffs, along with flax and fruit, to trade with visiting ships for manufactured goods, from iron fishhooks to muskets. They also considered European ideas useful, especially literacy; even missionaries found a receptive audience when they started coming. Finally, several Maori rode on European ships to Australia, and a few got jobs as crewmen. Kororāreka (modern Russell), a whaling station on the northernmost peninsula of North Island, is now considered the first permanent European settlement and sea port in New Zealand. Or you may want to count European settlement as beginning when the first white person was born in New Zealand, Thomas King (1815).(32)

The first violent incident between Europeans and natives, the “Boyd Massacre,” occurred in 1809, at Whangaroa Harbor on North Island. The Boyd, a ship that came from Sydney to pick up a cargo of timber, was the third European ship to visit that harbor; the two previous ones had spread diseases to the local population, so the Maori thought a curse had fallen on the harbor, and thus were in a bad mood to start with. On the Boyd was Te Ara, the son of a local chief, who agreed to pay for his passage by working as a cabin boy; however, he was subsequently flogged and denied food for refusing to take orders. While the Boyd was anchored in Whangaroa Harbor, the local Maori attacked the ship, killing and eating most of the crew and passengers; then they looted the Boyd, and while trying to remove the gunpowder aboard, they set it off, killing some of the attackers and burning the ship.

In retaliation, the whalers attacked a village 37 miles to the southeast; one European and between sixteen and sixty natives were killed in the clash, including the village chief, Te Pahi. Tragically, Te Pahi favored good relations with Europeans, and had actually tried to defuse tensions when word about Te Ara's treatment got out; apparently the whalers mistakenly thought he had ordered the attack on the Boyd. News of the massacre and the reprisal delayed the first missionary visit until 1814, and caused the number of arriving ships to fall to "almost nothing" over the next few years.

It was probably inevitable that an event like the Boyd Massacre would take place, for between 1807 and 1845, New Zealand was in a state of chaos that we now call the “Musket Wars.” We saw in Chapter 1 that warfare had become a way of life for the Maori, and petty wars, usually fought after the crops had been harvested in the fall, were seen as a legitimate response to insults or crimes committed by members of other tribes. The weapons normally used were spears and clubs, rituals like the haka(33) were performed, and while some warriors were killed, there weren't enough casualties to destroy a tribe. Afterwards, the winners gained land and loot from the losing tribe and increased their mana and status, while the losers might have to move to a less desirable, unpopulated area.

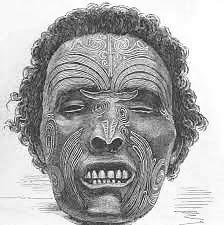

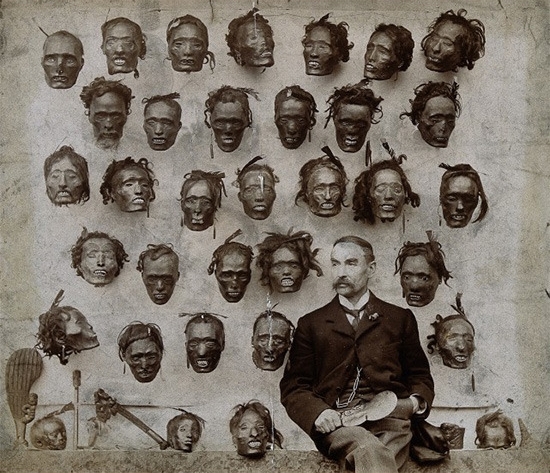

That changed with the introduction of firearms. At this stage in weapons technology, the muskets were mainly useful for “shock and awe”; they took so long to reload, that in the first battle where muskets were used, the tribe with guns was overpowered by the tribe armed with spears and clubs, before it got off a second round of shots. Still, stories of the power gained from muskets caused those who faced them to live in fear. And because a warrior with a musket had a range advantage against a warrior who couldn't use a spear or club until he was just a few feet away, the fighting did get deadlier. During the Musket Wars there were approximately 3,000 battles and skirmishes, in which as many as 20,000 Maori may have been killed, while at least 30,000 were enslaved or made homeless. Treachery, the burning of villages, killing of prisoners, torture and cannibalism were also common practices during this period.

The first two tribes to obtain muskets, the Ngapuhi and the Ngati Whatua, used them to settle the grudges they had against each other, and soon the other tribes felt they needed to have muskets to defend themselves, so all the tribes on North Island were armed with guns before long.(34) With the tribes armed equally, there were no more easy victories in the north, so some raided South Island, prompting the South Island tribes to demand muskets from Europeans, too. Across New Zealand, Hongi Hika, a chief of the Ngapuhi, became the most celebrated war leader, until he died in 1828 from a gunshot wound suffered a year earlier.

The largest battle in the Musket Wars was also the very first one; in the initial clash between the Ngapuhi and the Ngati Whatua, an estimated 16,000 warriors participated. However, Maori society was not designed to handle long-term wars. In peacetime most of the warriors were farmers and fishermen, and they were needed at home to keep the tribes fed. Because of that, and because the overall population was declining, the war parties got smaller; by the mid-1820s the typical Maori force did not number more than 350 men.

One campaign of the Musket Wars took place away from New Zealand, in the Chatham Islands to the east. We saw in Chapter 1 that the Chatham Islands were settled around 1500 by a Maori tribe that became known as the Moriori after their arrival. The local climate is cooler than that of New Zealand, so the plants brought by the Moriori did not thrive here, forcing them to live as hunter-gatherers.(35) One of the early chiefs, Nunuku, decided that they must not waste their limited resources in conflicts, and he introduced a permanent truce that prohibited warfare and cannibalism; subsequent laws and religious customs made the population renounce violence completely. To settle disputes, for example, they either negotiated a solution, or allowed a duel that was decided by first blood. Marriage between cousins was forbidden to prevent inbreeding, and sometimes male infants were castrated to keep the population from going above 2,000.(36) All these measures prevented the environmental destruction and civil war that Easter Island had suffered, but they also made the Moriori vulnerable to any visitors who did not intend to leave them alone.(37)

The ones who ended the Moriori social experiment were not Europeans but their Maori relatives. In the 1820s, two Maori tribes lost their land on North Island, and after migrating to the side of the island facing Cook Strait, decided to cooperate in an invasion of the Chatham Islands, because they heard there was food and land here, and natives who did not fight. They got their chance to do this in 1835, by hijacking the Lord Rodney, an Australian merchant ship in Wellington Harbor, and ordering its crew to take them to the Chatham Islands. For the first trip the Maori brought 470 tribal members, seventy-eight tons of seed potatoes, twenty pigs and seven waka canoes. Because a wooden sailing ship is not an ocean liner, those going for the ride suffered from overcrowding, and a shortage of good food and water; many were sick upon arrival, though the ship did not have a very long way to go. After the invaders disembarked, they sent the Lord Rodney back to New Zealand, and it brought another 430 Maori on the second trip.

When the Maori arrived, small armed groups of them walked all over the main island. Whenever they came upon a Moriori settlement, they told the residents that their land had been taken and the Moriori were now their vassals. They also began to enslave some Moriori, and kill and eat others.(38)

At first the Moriori withdrew to one of their holy places, to get out of the way. When they realized the Maori had no plans to leave, their elders held a council. Though they knew how the Maori treated their victims, and some of the chiefs pleaded that Gandhi-style pacifism was not appropriate now, two chiefs, Tapata and Torea, declared that "the law of Nunuku was not a strategy for survival, to be varied as conditions changed; it was a moral imperative."(39)

And that was all she wrote; there would be no resistance. Between 200 and 300 Moriori were quickly slaughtered, and the rest were enslaved. As one Moriori survivor told it: "[The Maori] commenced to kill us like sheep.... [We] were terrified, fled to the bush, concealed ourselves in holes underground, and in any place to escape our enemies. It was of no avail; we were discovered and killed - men, women and children indiscriminately." On the other side, a Maori explained, "We took possession... in accordance with our customs and we caught all the people. Not one escaped....."(40) But through it all, as descendants of the Moriori proudly point out, not one Maori invader was killed. The Moriori never compromised with the principles that made them unique, even when it meant the end of them and their culture.

Moriori holy sites were desecrated, and Moriori were forbidden to marry other Moriori. In 1842 thirty Maori and an equal number of Moriori slaves migrated to the subantarctic Auckland Islands, 290 miles south of South Island, and lived there for twenty years by hunting seals and growing flax. By the time the Maori were ordered to free their slaves, in 1862, only 101 Moriori were still alive. The last full-blooded Moriori died in 1933, so in the end the Maori disposed of them as completely as European settlers had gotten rid of the Tasmanians.(41)

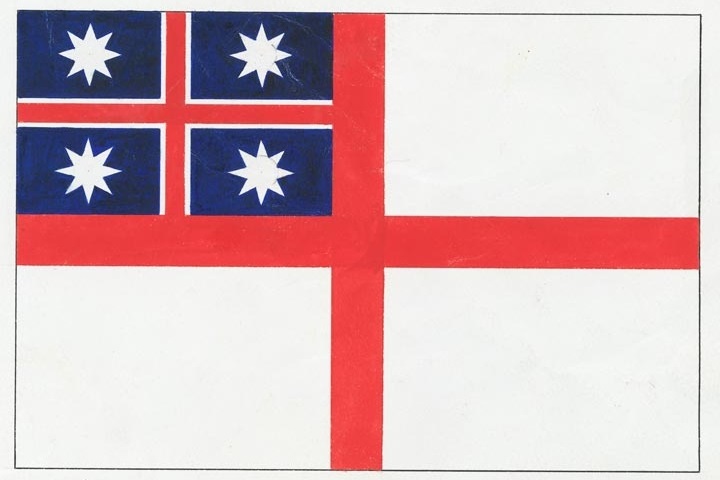

By the 1830s, many settlers were calling for an end to the lawlessness in New Zealand, not only because of the Musket Wars, but also because of the behavior of individual sailors and adventurers. These voices were echoed abroad by missionaries, who saw the chaos making their job tougher than it needed to be, and by those who feared the French were about to establish a colony in New Zealand.(42) In 1833 the governor of New South Wales appointed a resident, James Busby, as the official representative of the British government on North Island. One year later Busby got the northern Maori tribes to form a confederation, the United Tribes of New Zealand, and they created for themselves a flag and a declaration of independence, which Britain's King William IV accepted.

The United Tribes flag.

Source: http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/culture/taming-the-frontier/united-tribes-flag

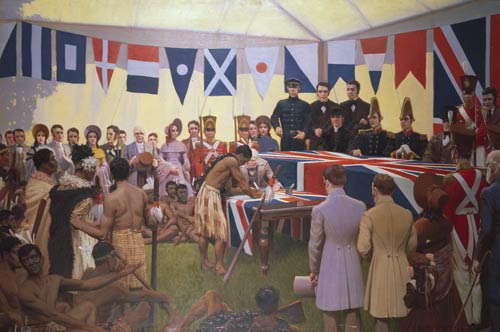

This did not stop the lawlessness, and London realized that the only way to impose order was to make New Zealand a colony, since the settlers were coming in at a rate that could not be stopped. Accordingly, New Zealand's first governor, Captain William Hobson, was appointed next. Once he arrived, on January 29, 1840, Hobson drew up the Treaty of Waitangi, along with his secretary James Freeman and Busby. Instead of recognizing an independent New Zealand state, this document declared that the king or queen of England was New Zealand's ruler. In return for ceding their sovereignty, the Maori would receive all the rights of British citizens, and get to keep their land. After the treaty was translated into the Maori language, forty-three local chiefs signed it, on February 6, 1840. Then during the next eight months, the treaty was taken all over North and South Island; eventually it got signatures from more than 500 chiefs.

The first signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, New Zealand's founding document.

Source: http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/artwork/1487/the-treaty-of-waitangi-in-art

Meanwhile the New Zealand Company (see the previous footnote) founded a new settlement on Wellington Harbor, and the first settlers arrived one week before Governor Hobson did. At first they called it Port Nicholson, but before 1840 ended they renamed it Wellington, after the Duke of Wellington, of course. Hobson sent soldiers to make sure they knew they were under British rule, and not part of a new, independent state. The leader of the settlement responded with a proposal to make Wellington the capital of the colony, but Hobson preferred another new settlement on North Island's narrowest point, which was named Auckland after George Eden, the Earl of Auckland and the current governor-general of India. Thus, Auckland became the capital of New Zealand in 1841.(43)

For those keeping track of demographics, New Zealand's estimated population in 1840 was 70,000 Maori and 2,000 Pakeha (whites). A demographic map would have shown a few white settlements on the coast, surrounding an overwhelmingly Maori heartland, especially on North Island. While the Maori were comfortably in the lead at this point, foreign diseases continued to take their toll, and the number of immigrants increased every year, so the Maori won't be ahead for much longer.

The Tahitian Kingdom

Pomare II had been appointed heir in 1782 by his father, and thus became king of Tahiti upon Pomare I's death in 1803. But while the other Tahitian chiefs had recognized the authority of Pomare I over them, they did not feel their allegiance extended to his descendants. They revolted, defeated Pomare II in 1808, and he fled to the nearest island, Mo'orea. Although the royal family was still pagan at this point, the missionaries on Tahiti were seen as their allies, so the missionaries had to flee, too.

In exile, Pomare believed he had been abandoned by 'Oro, the god of his father and grandfather. The missionaries saw this as their cue and advised Pomare that since his god had let him down, he should try theirs. Pomare listened, and was regarded as a Christian from this time forward. In 1815 he returned to Tahiti with armed followers and crushed his enemies at the battle of Te Feipi, which allowed him to resume his reign. Christianity also triumphed with that battle. In the aftermath, Pomare acted more merciful than his predecessors; the homes of the losers were not burned, their families were not massacred, and enemy warriors who laid down their weapons were pardoned.

The many deaths caused by disease and the recent civil war encouraged most Tahitians to convert to Christianity during the next few years, leading to the dramatic changes in Tahitian society that we noted previously. The missionaries also encouraged the introduction of new crops and industries to bolster the economy. By 1819 Tahiti had a sugar mill, a textile factory, a printing press, and farms growing cotton, sugar cane and coffee.

Pomare II completed his conversion by accepting baptism in 1819, and he followed this up by writing Tahiti's first law code, using advice from the missionaries to make sure the laws followed Christian principles. However, it doesn't appear that he – or anyone else in the royal family – was a devout Christian; Pomare converted mainly because it was the easiest way to gain European support. It showed in 1821, when excessive drinking caused him to get sick and die. His son and heir, Pomare III, was only one year old, so a council of Regency ran Tahiti until he in turn died in 1827.

Now the throne passed to 'Aimata, the fourteen-year-old daughter of Pomare II, and in keeping with the family custom, she changed her name to Pomare IV. The missionaries saw her as another regent, expecting her to step down when a male ruler of adult age appeared. Instead, Pomare IV ruled for a full fifty years (1827-77), the longest reign of the Tahitian dynasty. During that time, she succeeded in bringing several of the Society and Austral Islands under her rule and forged alliances with the rest, but she also saw the French show up and take over this part of the Pacific.

French involvement started with the arrival of Catholic missionaries. Two French Jesuits, Fathers Honoré Laval and François Caret, founded a mission on Mangareva (at the southeastern end of the Tuamotu Archipelago) in 1834, and in 1836 they were quietly dropped off on the eastern tip of Tahiti. Being British and Protestant, the missionaries already on Tahiti saw these priests as a threat, and when they showed up in Pape'ete, Tahiti's capital, they were arrested and deported. Another Catholic mission was established in the Marquesas Islands in 1838, and France used the mission as the reason for more French activity. Four years later the French Pacific Naval Division arrived, commanded by Rear Admiral Abel Aubert Dupetit-Thouars, to officially annex the Marquesas; this was the first step in the creation of French Polynesia.

Unfortunately for Tahiti, the French were unusually touchy at this time, because they were starting to build a new empire, and for this purpose, any excuse for “gunboat diplomacy” would do. A few years earlier, France responded to the insulting of a French diplomat by invading and conquering Algeria; now the expulsion of the two priests from Tahiti would be used the same way. Demands, claims and counterclaims were exchanged between Paris and Pape'ete; Queen Pomare wrote letters to King Louis-Philippe of France and Queen Victoria, apologizing to the former and requesting military assistance from the latter. Instead, when the fleet was done imposing French rule over the Marquesas, Admiral Dupetit-Thouars sailed to Tahiti, and with the guns of his flagship pointed at Pape'ete, declared Tahiti a French protectorate. A governor was installed to represent French interests; George Pritchard, a missionary who also happened to be a British consul and advisor to the queen, was arrested and expelled from the island; Catholic missionaries were brought in to replace their Protestant predecessors.

Admiral Dupetit-Thouars had taken Tahiti without the French government's permission, and the French treatment of Pritchard badly hurt relations with Britain, but France decided to keep all that it had taken, and Britain did not intervene when the Tahitians revolted, in a struggle now called the French-Tahitian War or the Tahitian War for Independence (1844-47). The queen lived in exile on Raiatea during this conflict, and native guerrillas gave the French such a hard time that they had to build forts, but in the end France prevailed; for good measure they also declared an unofficial protectorate over Mangareva. When the fighting ended, Queen Pomare returned to Tahiti, but for the rest of her reign she was a figurehead.

Pomare IV.

A French Foothold on New Caledonia

Thwarted in their efforts to establish a colony in Australia or New Zealand, the French took another look at the nearest Melanesian islands. So did other Europeans, who began visiting New Caledonia to hunt whales and collect sandalwood around 1840. And now that Christianity was spreading nicely in Polynesia, missionaries also turned their attention to Melanesia. The first missionaries to arrive in this area were Protestants from the London Missionary Society and Catholics from the Marist Brothers, a recently founded French order. However, the mission effort in Melanesia required greater resources than Polynesia, at a time when the churches had fewer resources available (the revivals that occurred around 1800 were clearly over by now). Consequently, the missions in Melanesia were a cooperative effort almost from the start; recently ordained clergymen from places like Tonga and Samoa worked with white missionaries on this project. Nevertheless, it was very slow going. The first Europeans to come to this area had left a bad impression in their mistreatment of the natives, and the natives showed their resentment with violent and unpredictable attacks on foreigners. This led to the deaths of several missionaries and their assistants, and added to Melanesia's reputation as the most dangerous part of the Pacific. Only in the Loyalty Islands (next to New Caledonia) and the southern New Hebrides did the missionaries convert a significant share of the population before 1860.

In 1848 George Augustus Selwyn, the first Anglican bishop of New Zealand, came up with the idea of converting Melanesia by bringing Melanesian boys to Auckland for training, and sending them back as ordained clergymen, on the assumption that Melanesians would be more receptive to the Gospel if they heard it from one of their own. However, there were logistical problems in the training. If the boys were kept away from home for more than a year, it would be cruel to them, and leave them so assimilated into Western culture that they might even forget their native languages. But when the training was interrupted with vacations at home, the program took longer, it cost more because of the frequent trips, the student could backslide when surrounded by unconverted family and neighbors, or he might lose interest and not return to the seminary. For those reasons, Selwyn recruited 152 boys for training during the 1850s, but only thirty-nine of them spent more than a year in Auckland. John Coleridge Patteson took over as the first Bishop of Melanesia in 1861, and he continued the training program, but he moved the headquarters and school from Auckland to Norfolk Island in 1865, and started teaching in a native language, Mota (from an island north of the New Hebrides where missionaries were active), rather than English. While this got results, it wasn't until the last decade of the nineteenth century, when Britain, France and Germany added the Melanesian islands to their empires, that missionaries in this region enjoyed success comparable to what they had experienced in Polynesia already.

As on other islands, the sandalwood supply did not last long in Melanesia, so Europeans switched to a more sinister trade they called “blackbirding” – the seizing of natives from New Caledonia, the Loyalty Islands, the New Hebrides, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands, to work on plantations in Fiji and northeast Australia. There were some cases where the natives asked, for whatever reason, to be taken from their home islands, and when their term of service ended (usually three years), they would be allowed to return. To most white observers, however, this was seen as a new kind of slavery or indentured servitude. The blackbirding business continued until 1904, long after slavery had been abolished in Europe and the Americas. That, and the death toll from introduced diseases like smallpox and measles, is why the Kanaks, the native population of New Caledonia, remained hostile to outsiders; in 1849 the crew of an American ship, the Cutter, were killed and eaten by a Kanak clan.

Nevertheless, France was determined to have a colony somewhere in Melanesia. In 1853 Admiral August Febvrier Despointes took possession of New Caledonia for France; the island's capital, Nouméa, was founded a year later. Settlers came almost immediately to establish farms, and in 1864 Jules Garnier, a mining engineer, discovered nickel ore, thereby launching what has been New Caledonia's most important industry since then. At the same time, the French government declared that the island would become a penal colony; between 1864 and 1894 France sent 22,000 criminals and political prisoners here (the latter included Paris Communards and Algerian nationalists). But the prisoners were always outnumbered by free settlers and Asian immigrants who came to take mining jobs.

Eventually the Kanaks were outnumbered as well. As white settlers arrived, they and the government forced the Kanaks off more than half the land, pushing them into reservations. This sparked a guerrilla war in 1878, when High Chief Atal of La Foa united many of the central tribes against the French; 200 Frenchmen and 1,000 Kanaks were killed before it was over. This rebellion was doomed to fail because native numbers were still decreasing; not until the 1930s would the population acquire enough immunity against disease to start growing again.

The Maori Wars

Unfortunately, there were bound to be misunderstandings after the Waitangi Treaty was signed, because the Maori language version of the document was not an exact translation of the English one. Instead of seeing themselves as citizens of the British Empire, Maori chiefs now reasoned that Queen Victoria would protect New Zealand from outside dangers, but with local affairs they were free to do what they pleased. They also badly underestimated the number of Pakeha who would move to New Zealand and want to buy Maori land.

We saw that the Maori were willing to get along with Europeans who had goods to trade and knowledge to teach. Indeed, until 1860 the city of Auckland bought most of the food it needed from the Maori, not from white farmers. However, as more settlers arrived, they needed land, and they put pressure on the Maori to sell it. Up to this time the Maori did not understand the concept of buying and selling land; they saw a tract of land as their identity, the home of the entire tribe (not the property of an individual), and a place for the graves of their ancestors. To them the only way they could gain more land was by defeating another tribe in battle and taking their land. Therefore taking away a tribe's land was a step towards destroying that tribe, and Governor Hobson knew it.

Desiring to avoid the mistakes the British had made when they added India and Australia to the empire, Governor Hobson placed a provision in the Waitangi Treaty which allowed the highest-ranking chiefs a chance to veto any proposed land sale. Unfortunately the New Zealand Company wasn't as scrupulous; it made deals with subchiefs to buy land in ways that were illegal; settlers also made the argument that the land should belong to them because the Maori were not using it efficiently. Because of this, the Maori became alarmed and began to resist the inroads settlers were making. The result was the same as what happened when European colonies were founded on the east coast of North America in the seventeenth century; the American Indians were often friendly when European outposts were too small to be a threat, but when those communities became big enough to push the Indians off their own land, the white man became their enemy. The “Musket Wars” that we covered previously were conflicts between native tribes, and Europeans could avoid becoming casualties by staying away from the areas where fighting was taking place. But now Maori and Pakeha were running into each other too often, so the next generation in New Zealand would see true race wars.

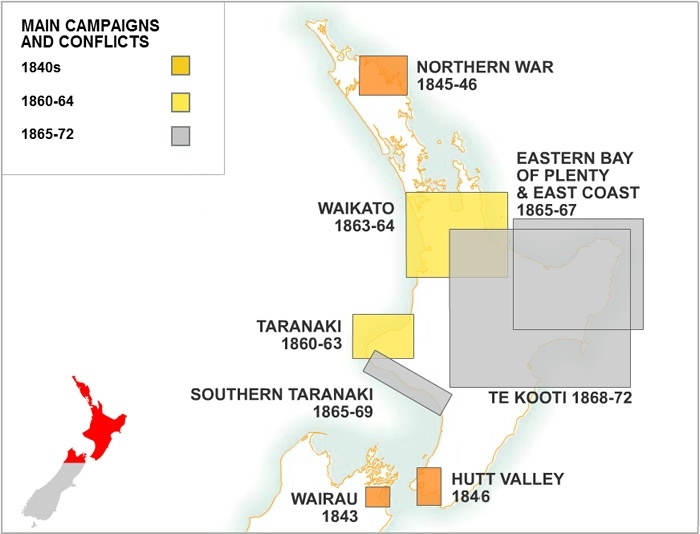

The dates and general locations of the Maori Wars.

Source: New Zealand Wars map.

The Wairau Massacre, the Bay of Islands War, and the Wellington/Whanganui Battles

The first bloody incident was the Wairau Massacre of 1843. A group of settlers had illegally purchased the Wairau Valley, on the north shore of South Island, and the Ngati Toa tribe would not let them survey the land. At first the Maori chiefs requested that the Europeans wait until the government decided the matter, but during the standoff, shots were suddenly fired. By the time the fighting was over, twenty-two Europeans and four Maori were killed, including the wives of the two chiefs on the scene. Governor Hobson had died in 1842 and his replacement, Robert FitzRoy, ruled that the Ngati Toa had been provoked by the settlers, so he took no action. The settlers and the New Zealand Company were both dismayed by this response, and took it to mean the government put the needs of the natives before the needs of the settlers.

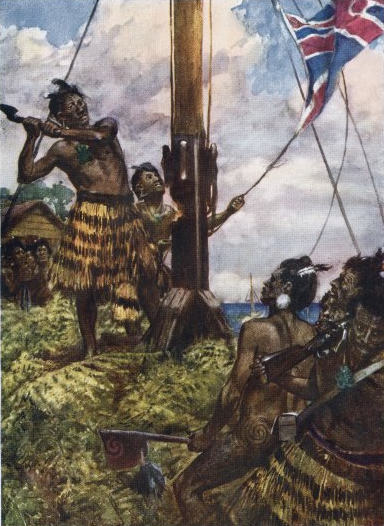

The next event, the Bay of Islands War (1844-47), was a more serious conflict; it is also called the Flagstaff War or the First Maori War. Hone Heke, the chief who started it, had several reasons to be upset: the Wairau Massacre, settlers grabbing more and more land, the shrinking Maori population, and the moving of the capital to Auckland (which hurt business for his tribe). To show he wasn't happy with how things had turned out, since the Waitangi Treaty had replaced the United Tribes flag with the Union Jack, Hone Heke staged a raid on Kororāreka/Russell, that culminated with Hone Heke chopping down the flagpole flying the British flag. Over the next few months, the flagpole was replaced and cut down again three times, but because he was a Christian, Hone Heke left the European residents of Russell alone. However, when the final felling took place in March 1845, he brought along an allied chief, Te Ruki Kawiti, and together they chose to sack the town as well; the survivors of this raid escaped to Auckland. That marked the beginning of war between British troops and the northernmost Maori tribes.

The flagpole that started the war. From Wikimedia Commons.

Next, Hone Heke and Kawiti began raiding other white settlements on the north side of North Island. Three British regiments were sent from Auckland to deal with the menace. However, their opponents had built major earthenworks, modern versions of the traditional pa fortifications. The British shelled and captured the first fort they encountered, Otuihu Pa, but the tribe owning it turned out to be neutral, not on Hone Heke's side. Then they attacked two enemy forts, Puketutu (owned by Hone Heke) and Ohaeawai (owned by Kawiti), and failed to take either one. Still, this did not mean the Maori were united; immediately afterwards Hone Heke's force was attacked by a force led by Tamati Waka Nene, a chief who remained pro-British, and Hone Heke could not dislodge them from Te Ahuahu, the fort Waka Nene had in the area.

All the events in the previous paragraph happened in mid-1845, wintertime in the southern hemisphere. The British decided they would do better if they waited until the weather warmed up, and took a timeout. While they were waiting, Sir George Grey became both the new governor and commander of the troops; he would be the last important colonial governor in New Zealand's history.(44) With Grey came more soldiers and 32-pounder cannon, artillery pieces they did not have previously. On the other side, Kawiti built the most formidable fort yet, Ruapekapeka Pa (“Fort Bat's Nest”), and he was so confident of its strength that he rejected a peace proposal from Grey, before the British started moving again. To get to the fort, the British had to hike and haul their cannon through a dozen miles of very difficult terrain; this took two weeks, and once the cannon were ready, they bombarded Ruapekapeka for another two weeks, without using the troops in a frontal assault like they had before. Suddenly on January 11, 1846, they noticed that the fort appeared empty, and when a combined British-Maori force stormed the fort, they found only a few defenders inside. What really happened is still a subject of controversy. The day when Ruapekapeka was taken happened to be a Sunday, and at the time it was said that the Christian Maori had gone outside for a church service, allowing the less pious British to take the fort by surprise. However, the Maori had shown in other battles that they were willing to fight on Sundays, and there were no provisions left in the fort, meaning that those who abandoned it were not planning to return. It now appears more likely that Hone Heki and Kawiti were preparing an ambush outside the fort, which failed because the British moved before they were ready.

After the battle of Ruapekapeka, Hone Heki and Kawiti were ready to make peace. This war, like previous wars involving the Maori, had begun to disrupt food production, and using Waka Nene as their go-between, they offered to end the rebellion if British troops would get off their land. Surprisingly, since he had won the last battle, Grey accepted those terms; everyone from the opposing tribes was pardoned, and no land was confiscated. This prompted Waka Nene to tell Grey, “You have saved us all.” However, Grey waited until after Hone Heke's death to put up a new flagpole at Russell.

Grey may have been lenient because trouble was brewing on the other side of North Island, in the neighborhood of Wellington. The Wellington settlers were still mad at how the government had handled the Wairau Massacre, and there were some skirmishes between them and the Ngati Toa. Governor Grey responded by sending troops to Wellington and putting the community under martial law (March 1846). The main area of fighting was the Hutt Valley, and the following May saw the largest battle here, when a Maori war party attacked Boulcott's Farm; eight British soldiers and ten Maori were killed. In June news of more war parties on the way prompted Grey to extend martial law to the town of Whanganui; in July a raid captured Te Rauparaha, the Ngati Toa chief, and resistance from that tribe soon ended.

Wellington was now secure, but the Ngati Toa had made alliances with other tribes, and those allies now transferred their attention to Whanganui. Here the settlers claimed they had bought the land in 1839, while the local tribes denied they had ever sold it. Tensions rose when 180 British soldiers arrived in December 1846. Still, the two sides managed to get along until April 1847, when a pistol accidentally went off, wounding a minor chief in the head. Although the chief began to recover and he testified it was an accident, six natives went looking for revenge; at the home of one J. A. Gilfillan, they wounded the father and a daughter, and killed the mother and their other three children. All but one of the killers were captured by friendly natives, handed over to the British, tried and hanged. However, only a fraction of the Maori in the area thought the execution was a proper punishment; the rest took up arms and attacked Whanganui. Most of the residents and troops withdrew to Rutland Stockade, the hilltop fort overlooking the town, and for the next two months (May-July 1847) the Maori tried using minor skirmishes to lure the defenders out. The biggest encounter was the battle of St. John's Wood (July 19), which involved 400 warriors on each side, and saw three killed on each side. In late May Governor Grey showed up with some northern chiefs, in an attempt to defuse the conflict. Finally at the end of July the Maori withdrew, because they needed to go home and plant their potato crops. Grey negotiated a peace settlement in February 1848, and it lasted for a dozen years, in part because both sides were too busy making money; the Australian gold rush of the 1850s (see below) gave both Maori and Pakeha farmers opportunities to sell food to the prospectors in Australia.

Meanwhile in London, Parliament passed the New Zealand Constitution Act in 1846, which proposed self-government for New Zealand's settlers. Grey persuaded London to delay implementing the act for six years, arguing that because there was native unrest, a local Parliament made up of whites could not be trusted to pass laws that would protect the Maori majority. The settlers didn't like this, and protested that their needs were being ignored again. Nevertheless, they had to wait until 1852 for a constitution, followed by their own Parliament and a reorganization of New Zealand into six provinces. Henry Sewell, the first representative from Christchurch in Parliament, was elected as the first prime minister in 1855, and held that job for only two weeks before a no-confidence motion brought it down. The governor retained responsibility for defense, Maori affairs and land sales, while in other areas the prime minister became the leading official in the New Zealand government.

The Taranaki Wars

Tensions between settlers and natives rose during the 1850s, again because the settlers wanted more land than the government and the Maori were willing to sell. Many Maori thought no more land should be sold, and because they saw unity as the secret behind British strength, they founded the Kingitanga (Maori King Movement), with the goal of uniting all Maori tribes under a single monarch. By contrast, the current system established by the Watangi Treaty favored disunity, because it allowed Maori to kill each other, and the British got involved only when Pakeha were killed. They also gradually realized that the British government's ultimate goal was to impose British law and culture on the Maori, thereby assimilating them into Western society.

From 1853 onward two leaders in the Kingitanga movement, Mātene Te Whiwhi and Tāmihana Te Rauparaha, wandered all around North Island, looking for a suitable chief to become king. Most of the chiefs they met refused the honor, because the Maori tribal mindset said that no tribe should rule another tribe. Eventually the seekers decided on Potatau Te Wherowhero, the chief of the Waikato tribe, in part because he had never signed the Waitangi Treaty. He also said no at first, but later came around to agree that the Maori needed more effective leadership, so he was proclaimed the first Maori king in 1858. Although the governors were reluctant to negotiate with Potatau after he made this move, it was not an act of rebellion because the Maori still saw Queen Victoria as the ultimate human ruler over them; they just didn't want governors and prime ministers as intermediate authorities. Furthermore, not all Maori tribes recognized this new ruler over them. Two years later Potatau died, and he was succeeded by his son, Matutaera Tawhiao; he would rule during one of the most difficult and depressing times in Maori history (1860-94).

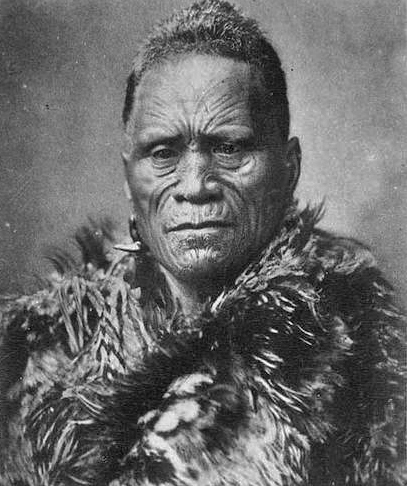

King Tawhiao.

The next three wars are called the Taranaki Wars because they all saw activity in Taranaki, a rich district on the west side of North Island. Settlers had founded a town here called New Plymouth, and they felt the land purchased for the town was not enough for their needs. In 1859 a Maori subchief in Taranaki sold another block of land at the mouth of the Waitara River without his tribe's permission, and that tribe resisted when surveyors and settlers came to the tract in question. The current governor, Thomas Gore Browne, paid no attention to the part of the Waitangi Treaty that allowed senior chiefs to veto land sales, and ordered 400 troops into the land tract. In response, the local chief ordered the building of an L-shaped pa, overlooking the British garrison. The local commander, Colonel Charles Gold, ordered an attack on the pa (March 17, 1860), but the Maori kept them from taking it until dawn the next day, when the troops found the fortification abandoned. Still, the First Taranaki War was on. Because the British had fired the first shots, Maori war parties from outside Taranaki soon showed up, and began raiding the farms near New Plymouth.

For this war, the British brought in 3,500 professional soldiers from Australia, to fight alongside the local militia. Against them, the size of the Maori force ranged from a few hundred to 1,500, since as we mentioned previously, the Maori were part-time warriors. Whenever the British attacked a pa, they either failed to take it, or if they succeeded, they overcame so few defenders that it was a hollow victory. Finally, when the British seized the Te Arei Pa in early 1861, the Maori proposed a cease-fire because harvest time was approaching, and it was accepted. This war had been fought to a draw; British casualties are estimated to have been 238, while Maori losses were about 200. The Maori also were allowed to keep Tataraimaka, a block of land west of New Plymouth that they had captured. However, the British promised to return the Waitara River block as well, but never got around to doing it, and they re-occupied Tataraimaka at the beginning of the next war.

The cease-fire held for two years. When fighting broke out again in April 1863, Sir George Grey was back for his second term as governor, and because the Kingitanga movement was based in Waikato, a district just south of Auckland, Grey decided to make Waikato the main theater of the war, instead of Taranaki. Even before the war resumed, Grey had the commander of the Imperial British Forces, General Duncan Cameron, build a road going into Waikato, so it would be easy to move troops (1862). Then with the return of hostilities, he demanded that all chiefs in Waikato swear allegiance to Queen Victoria, and when they refused, he launched the invasion. This would be the largest campaign of all the Maori Wars, pitting 14,000 British troops (both Imperial and colonial) against an estimated 4,000 Maori. In addition, the British had the help of gunboats, firing at various targets on land. During a nine-month period (July 1863-April 1864) the British advanced slowly because of heavy native resistance, and practiced a “scorched earth” policy by driving the inhabitants away, destroying native villages and farms, building fortifications in areas that had not been pacified yet, and letting settlers move into areas that were secure. In this way the settlers gained 1.2 million acres of land by the end of the war; the provisions of the Waitangi Treaty were forgotten by just about everybody.(45)

Today's New Zealanders mainly remember three battles from the Waikato phase of the Second Taranaki War. The pa of Meremere held out for two months (August-October), with gunboats and native riflemen exchanging fire. Finally, when British barges transported 600 men past Meremere, the Maori realized they were now behind enemy lines, and abandoned the fort. The battle of Rangiriri, a two-day struggle in November 1863 to capture a pa by the same name, was the bloodiest battle involving Europeans in New Zealand's history; 136 Europeans killed and wounded, 71 Maori killed and wounded, and 180 Maori warriors captured. Then in April 1864 came a three-day siege of the fort at Orakau, which is now called “Rewi's Last Stand” (after Rewi Maniapoto, the Maori commander). When Orakau fell, the remaining Kingitanga Maori withdrew into the interior of North Island, allowing the British to proclaim victory.

In the twentieth century the government eventually admitted that Europeans had done the Waikato Maori dirty; tribes like the Tainui had never rebelled, but had been forced into a defensive war they could not win. The 1927 Royal Commission on Confiscated Land ruled that the Waikato land confiscations had been “excessive,” returned one fourth of the land taken, and paid about £23,000 in compensation. You'll probably agree that wasn't enough, and more than sixty years later the Tainui decided to negotiate directly with the British Crown, rather than with any authority in modern New Zealand. They reached a settlement in 1995 that was signed both by Queen Elizabeth II and the current Maori queen, Dame Te Arikinui Te Atairangikaahu. In this the Crown apologized to the Tainui and the Kingitanga for the loss of life and property the invasion of Waikato had caused, and agreed to pay a compensation of cash and government-controlled land worth $171 million – an estimated 1 percent of the value of the land confiscated in 1863.

Though the fighting had ended in Waikato, the struggle continued on other parts of North Island. Attention now turned to Tauranga and the Bay of Plenty, an area where the tribes had sent reinforcements and supplies to the Kingitanga. Here the Maori scored their greatest victory, at the battle of Gate Pa (also called Pukehinahina), in late April 1864. At Gate Pa, 250 warriors from the Ngai Te Rangi and Ngati Koheriki tribes defeated a much larger force of 1700 British soldiers, by letting the British bombard the fort until they breached its defenses, and then ambushing the soldiers that tried going in through the breach. The British were greatly embarrassed that they could not beat a force of what they called “half-naked, half-armed savages,” so two months later, when the British surprised a force of 500 Maori by catching them in the open before they could complete the fort they were working on (the battle of Te Ranga), they felt redeemed from the previous defeat. In July 1864 Governor Grey offered terms of peace, in which the Ngai Te Rangi gave up most of their weapons, but little land was confiscated from them; Grey even gave them food and seeds to help them get through the winter. We think he let them off easily because London let him know that Britain was getting tired of wars in New Zealand and wanted to bring its troops home (see the previous footnote), so Grey was expected to establish a “just and enduring peace” as soon as possible. However, some warriors who weren't willing to make peace arrived on the east coast of North Island after that, and they caused a number of skirmishes until 1867, which we now call the East Cape War or East Coast War.

Those warriors mentioned in the previous sentence followed a new religion, which motivated many Maori to keep on fighting. Founded in 1862 by a prophet named Te Ua Haumene, it was called Pai Marire (Goodness and Peace) and combined elements of Judaism, Christianity and paganism. Chief among these was the idea that the Maori were one of the lost tribes of Israel (the priests were called Teu, meaning Jews), and Te Ua observed the Sabbath on Saturdays; however, worship services were conducted around a sacred pole, rather than in a church. To promote Pai Marire, Te Ua chose three disciples (their names were Tahutaki, Hepenaia and Wi Parara), and wrote a book, Ua Rongo Pai (The Gospel According to Ua), which taught that soon God would drive the Pakeha into the sea and restore New Zealand to His people. As the religion's name suggests, Pai Marire started out peaceful, but warrior converts in Taranaki quickly turned it into a violent anti-Pakeha cult. These folks believed that if they shouted “Pai Marire, hau hau!” in battle, their words would call the god of the wind to protect them from bullets, so they came to be known as the Hauhau movement. The Hauhau also practiced traditional incantations, and sometimes committed beheadings and cannibalism; their most famous victim was a German missionary, Carl Völkner.

In April 1864 the Hauhau announced a prophecy which predicted they would soon win a battle, and sure enough, at Ahuahu in Taranaki, Maori successfully ambushed a larger British force, while they were resting without their weapons in easy reach; this persuaded more Maori to join the movement. However, neither Pai Marire nor Hauhau were appealing to those Maori who were Christians already. And the rest of the battles fought in 1864 and 1865 all resulted in Maori defeats; the Hauhau presence made things more complicated for the British, but it did not keep them from winning. Governor Grey responded to the Hauhau atrocities by ordering the movement suppressed, and about 400 followers of the cult were arrested and incarcerated on the Chatham Islands. Te Ua was captured, too, but because he swore an oath of loyalty to the Crown, and he wasn't leading the Hauhau warriors, he was pardoned. Still, the cult was not stamped out completely; according to the New Zealand Department of Statistics, when it conducted the 2006 census, 609 people claimed "Hauhau" as their religion.

The last phase of armed Maori resistance, now called the Third Taranaki War, lasted for seven years (1865-72), and took place in three areas – southern Taranaki, the east coast and the interior. In southern Taranaki, Duncan Cameron's terrible campaign (see the previous footnote) was continued into 1866 by Trevor Chute and Thomas McDonnell. On the Maori side a Ngati Ruanui subchief, Titokowaru, became the leader of the resistance. Up to this point, Titokowaru's credentials were that he was a veteran of the Second Taranaki War and a Methodist lay minister; suddenly in the mid-1860s he converted, becoming a Pai Marire prophet. Because of all the destruction inflicted by the British advance, Titokowaru proclaimed 1867 a year of peace and reconciliation, but the continuing creeping confiscation of land by settlers was too much even for a pacifist, so in June 1868 Titokowaru ordered his followers to resume the war.

For the rest of 1868, Titokowaru's Maori won a series of stunning victories, despite being outnumbered, and the size of their force grew from 150 to 1,000. The settlers in Taranaki and Whanganui became seriously concerned for their future, and the government considered giving back all confiscated land. On February 3, 1869, the Kingitanga movement got involved on Titokowaru's side, with a raid in north Taranaki. Since everyone now knew that Titokowaru was a military genius, what happened next is a mystery. At the village of Tauranga-ika he built a pa, the strongest Maori fort yet, and on February 2, the British assaulted it, without breaking through its defenses, only to find out the next day that the Maori defenders had slipped away under cover of darkness. No one knows why Titokowaru's army abandoned a fortress that looked impregnable, or why the army fell apart over the next few days. The most common explanation is that Titowokaru committed adultery with the wife of one of his warriors, and thus lost too much mana to continue leading them; he may also have been frightened by the British attack, or they may have run out of food or ammunition. Titokowaru escaped to the upper Waitara valley and went back to preaching his old message of peace, so when the British stopped pursuing him, the war ended in Taranaki.

During the East Cape War a Maori fighting on the side of the British, Te Kooti Arikirangi Te Turuki, was accusing of being a Hauhau spy. Though he was a Christian and he appealed for a trial to clear his name, he was exiled to the Chatham Islands, along with the third bunch of Hauhau prisoners sent there. While serving his sentence, Te Kooti contracted tuberculosis, but he survived and during his recovery, he experienced two visions that prompted him to start his own version of the Hauhau movement, which he called Ringatu (“The Upraised Hand”); he subsequently converted many fellow prisoners. By the end of 1867 the chiefs among the prisoners had been released, making Te Kooti the unofficial leader of those who were left. On July 4, 1868, Te Kooti led a group of prisoners (163 men and 135 of their women and children), seized the Rifleman, a schooner that had just brought supplies to the Chathams, and used it to escape back to New Zealand. Upon arrival at Poverty Bay, on North Island's east coast, he requested shelter from King Tawhiao and offered to negotiate with the British government, but both rejected him. Te Kooti then decided to go inland and challenge King Tawhiao for spiritual leadership of the Maori, because he never recognized the king's authority. The local commander, Major R. N. Biggs, in turn decided that Te Kooti must be stopped, and sent a mixed force of militia, provincial troops and Maori volunteers to arrest Te Kooti and his followers.

The last Maori war, called Te Kooti's War, was a four-year guerrilla struggle (1868-72), which pitted colonial and pro-British Maori troops against Te Kooti's force; the latter peaked at 200 warriors in the second half of 1868 and dwindled away after that. Te Kooti won the first battles, but in November 1868 he went on the offensive, attacking the town of Matawhero, killing 51 men, women and children living there, including Major Biggs, and setting their homes on fire. This incident, the Poverty Bay Massacre, caused him to lose considerable Maori support, and the authorities put a price of £5,000 on his head. The bloodiest battle of the war, the siege of Ngatapa Pa, took place at the beginning of 1869; although Te Kooti escaped from this trap, he lost 136 of his followers here.

Next, Te Kooti retreated into the Urewera Mountains, taking refuge with the Tuhoe tribe, which didn't like the British much either. When they agreed to form an alliance, Te Kooti said, “I take you as my people, and I will be your God.” After that, when he went on raids, Te Kooti rode a white horse, which he claimed kept him from being captured. The next few months saw him stage several raids successfully, but when he went into the King Country, in an effort to either persuade Tawhiao to join him, or to depose him, the king refused to meet him in person. That made sure the Maori would not form a widespread, anti-British alliance. His luck seems to have run out at that point, because he lost the next battles, and was wounded three times, though again he managed to avoid capture.

In 1870 the government launched a scorched-earth campaign against the Tuhoe territory, using only Maori soldiers from anti-Tuhoe tribes. One by one, Tuhoe chiefs were forced to surrender and hand over any fugitives they were harboring. This put Te Kooti on the run, but still his pursuers failed to catch him. Finally Te Kooti decided he couldn't run anymore, so on May 15, 1872, he entered the King Country again and asked for asylum. King Tawhiao did not like Te Kooti's aggressive attitude, or the Ringatu creed he was preaching, but took in Te Kooti anyway. Because the King Country was closed to Europeans, and the only followers Te Kooti had left were members of his religion, the last war fought in New Zealand was now over.

Aftermath

The wars in New Zealand ended when they did because both sides were exhausted. The Maori had resisted European colonization even more strongly than American Indian tribes like the Seminole and the Sioux did. They fought back against encroachments on their land with such skill and courage, that it offset the European technological advantage; we saw how they won their share of battles. Ultimately they were ground down by the greater numbers and resources of the Europeans. James Cowan, an early twentieth century historian, counted the number of casualties in the wars, civilian as well as military, and estimated that overall, 2,154 Maori and 754 whites had been killed.

Because the Maori had been such formidable opponents, the Pakeha respected them enough to make sure they would continue to be part of New Zealand society, unlike the Aborigines in Australia. In 1867 four Parliamentary seats were reserved for Maori members, but since the Parliament had seventy-six members, this had a minimal effect on the political system. Efforts in recent years to undo or atone for the injustices of the war years, like the restitution for the invasion of Waikato mentioned previously, are another consequence of the wars being followed by a newfound respect for a former enemy who was so hard to beat.

However, none of this stopped the trend which had caused the wars in the first place – the Europeans taking Maori land without ever being satisfied (Raupatu became the Maori word for land confiscations). In 1863 it became legal for individuals to buy Maori land (they no longer had to wait for the government to get it for them), and in 1865 the Native Land Court was established to handle land transactions. What's more, land was now considered to be owned by individuals, rather than collectively by whole tribes – another move which made land sales easier. The Maori called the court “te kooti tango whenua” (the land-taking court) because in most cases the land was transferred out of Maori ownership; the court had also facilitated land confiscation immediately after the wars. The court still exists today, but in 1947 it was renamed the Maori Land Court, and currently its main purposes are to keep Maori land in Maori ownership, and to promote its use and development.(46)

After the wars, the Maori withdrew from contact with whites in most places; isolated, rural villages became the norm for them. In southern Taranaki, the community of Parihaka tried peaceful resistance; they pulled up survey pegs and destroyed roads and fences built on land they considered theirs. The government responded first with arrests, then in November 1881 it sent soldiers to invade Parihaka. The leaders of the resistance movement, Te Whiti-o-Rongomai and Tohu Kakahi, were imprisoned and exiled to South Island.

As for Te Kooti, he stayed in the King Country for a decade. In 1883 leaders of the Ngati Maniapoto tribe accepted a proposal to build a railroad through the King Country, and they persuaded the government to pardon Te Kooti, as one of the terms of their agreement. Afterwards, the Maori lost their independence even in this reservation. It finally disappeared when police invaded the last native sanctuary, the Urewera Mountains, in 1916.

The Kingdom of Hawaii

Kamehameha II

Kamehameha I was succeeded by 'Iolani Liholiho, the son of his highest-ranked wife, Keōpuolani; he took for himself the title Kamehameha II. The new king was twenty-two years old, a bit on the young side, so another wife of the previous king, Ka'ahumanu I, announced that Kamehameha I had wanted her to share power with his heir, and thus became the official regent. Because Ka'ahumanu was the late, great king's favorite wife, she was able to act as the power behind the throne for the rest of her life; though she could be nagging and shrewish, she gets credit for being an early champion of women's rights (the 'ai noa in the next paragraph was her idea). Also worth remembering is Kalanimoku, the high chief of Maui; he had served Kamehameha I as chief minister and treasurer, so it made sense to appoint him as the new king's prime minister.

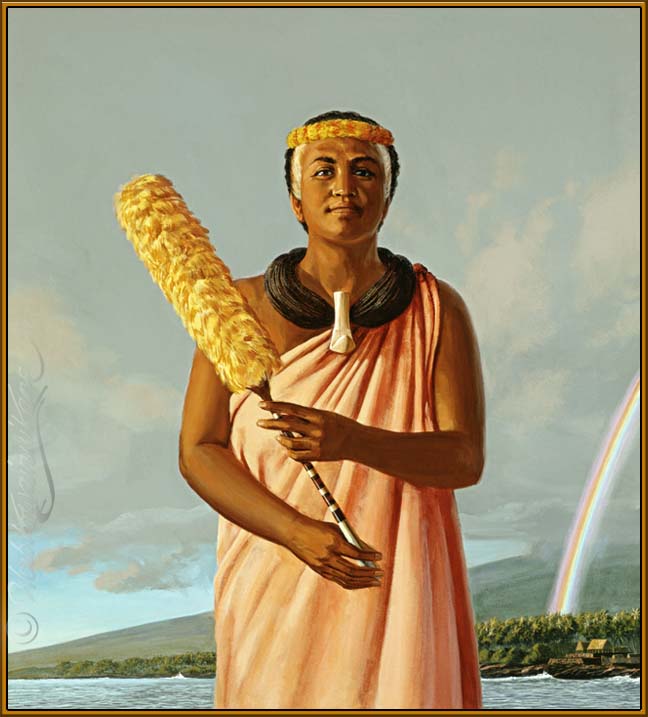

Queen Ka'ahumanu I. Painting by Herb Kawainui Kane (1928-2011).

Kamehameha II is mainly known for breaking tradition; he made sure everyone knew the old Hawaii, with its gods and Ali'i, had died with his father. Normally during a time of great mourning, the kapu (taboo) system was suspended – people could eat whatever they liked and have sex with whomever they pleased, and worship at the temples was not practiced – because routine life was seen as an impossibility. That was the case for the first six months of Kamehameha II's reign, but at the end of that time, instead of re-imposing the kapu, he committed an act the Hawaiians called 'ai noa (free eating); he ate a meal with the two queens mentioned above, Ka'ahumanu and Keōpuolani, and they dined in a place where commoners could see them. This broke more than one kapu; not only was it forbidden for men and women to eat together, but the main course, dog meat, was supposed to be for women only. When word of this spread around Hawaii, it told the people that the kapu system was gone for good.

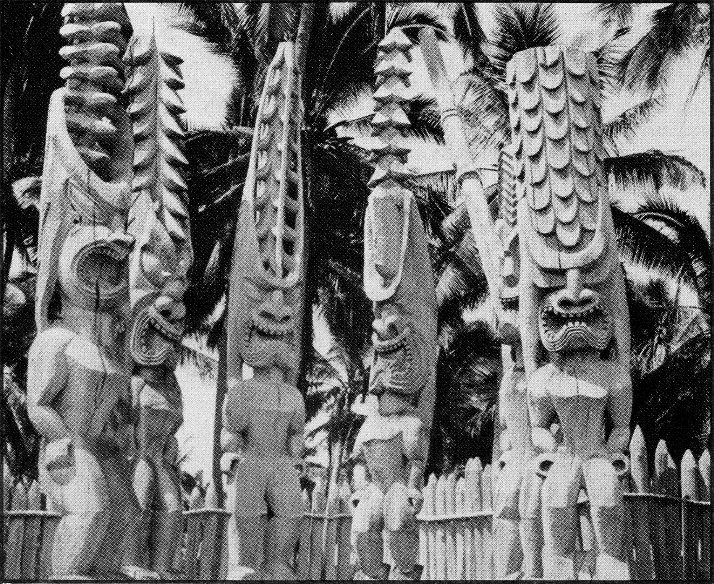

Next on the agenda was the destruction of the old religion. Together Ka'ahumanu and Kamehameha II ordered the desecration of the temples, the burning of wooden idols, and the disbanding of the priestly order. Naturally there was opposition to this, because many felt that rejecting the gods was asking for trouble, and it was led by Keaoua Kekua-o-kalani, the king's cousin and the current high priest to the war-god Ku. He launched a rebellion on the Big Island, but an army led by Kalanimoku quickly crushed it, at the battle of Kuamo'o.

Wooden idols (tikis) at the reconstructed Hale o Keawe Temple, in the Pu'uhonua o Honaunau National Historical Park, on the Big Island.

The Hawaiians did not have to go without a religion for long, because a new god came to Hawaii on March 30, 1820 (three months after Kuamo'o), introduced by a party of fourteen Calvinists from the United States. Hiram Bingham, the leader of the mission, showed he did not see Hawaii as an island paradise when he wrote about his first impression of the place: “The appearance of destitution, degradation and barbarism among the chattering, almost naked savages, whose heads and feet and much of their sunburnt swarthy skin were bare, was appalling. Can these be human beings?” This was the first time any Christian missionaries were allowed in Hawaii, and because of the spiritual vacuum, they made converts quickly. Keōpuolani was one of the first; she converted an hour before her death. The king didn't mind the new creed, but he refused to join it; to do so would have meant giving up drinking and four of his five wives, and he wasn't willing to do that.(47)

Kamehameha II indulged in an expensive hobby – he liked to collect boats, and travel around in them. The one he liked best was a small, modern schooner named the Prince Regent, which he received as a gift from England's King George IV in 1822. Restless and impulsive, he sailed to England to thank King George personally, and negotiate a defense treaty, leaving Ka'ahumanu in charge while he was away. He and his entourage had a great time touring London, but before they could meet with King George, they contracted measles, a disease for which Hawaiians had no immunity. Both Kamehameha and Queen Kamamalu died as a result; he had reigned for just five years (1819-24).(48) His younger brother Kauikeaouli became the next king, but his coronation was delayed eleven months, until the bodies of the previous king and queen could be returned to Hawaii and buried.

Kamehameha III

In keeping with the new tradition, Kauikeaouli changed his name to Kamehameha III. He enjoyed the longest reign of the Hawaiian monarchs (1825-54), but because he was only ten years old when he got started, Ka'ahumanu and Kalanimoku continued to run the show during the early years. After Ka'ahumanu's death in 1832, the king's older sister, Ka'ahumanu II, became the new regent, and they shared power until her death in 1839.

This period also saw the missionaries complete the conversion of the Hawaiians to Christianity. Ka'ahumanu I, for example, was baptized at the beginning of Kamehameha III's reign, and became an enthusiastic Christian afterwards. By 1826, all of the important chiefs had declared themselves Christians. Kamehameha III went down in history as Hawaii's first christian king, but he was a reluctant member of the faith. In the 1830s, he was especially known for racing horses, drinking, gambling and dancing the hula; apparently he thought following Christianity as the missionaries preached it would take all the fun out of life. At first there was only Protestant Christianity (the missionaries specifically told them to pay no attention to Catholic clergymen), but after threats to bombard Honolulu from a French ship, Hawaii signed a treaty in 1839 that guaranteed the safety of French nationals, including French Catholic missionaries; it also opened up the country to imports of French wine and brandy. Because of that treaty, and subsequent immigration from Catholic strongholds like the Philippines, Catholics outnumber Protestants in Hawaii today.

The most dramatic episode was provided by a chiefess named Kapiolani, who challenged the fire goddess Pele on her home ground – Kilauea. This was a bold move, considering that Kilauea had destroyed an army in 1790. Early in 1824, Kapiolani had become the first Hawaiian leader to build a church, and in November of the same year, she led a crowd in a hike across the Big Island to Kilauea, said a Christian prayer instead of a pagan prayer to Pele, and descended about 500 feet into the main caldera. There she announced, “Iehovah is my God. He kindled these fires. I fear not Pele.” Then she cast stones into the lava lake below, and ate ohelo berries, a local fruit that previously had been considered sacred to Pele, and kapu for women (compare this with Kamehameha I's visit in footnote #26). The volcano did not erupt or do anything else to protest, so Kapiolani escaped with only bruises on her feet from the rocks, and Christians in Hawaii and abroad told and retold this heroic story for the next fifty years.

Another important move came in 1840, when the king and queen introduced Hawaii's first constitution, which ended the absolute monarchy and put the laws down in writing. This document also created Hawaii's first Supreme Court, and a bicameral legislature, with a House of Nobles and an elected House of Representatives. In 1852 it was decided that the new government wasn't democratic enough (all it did regarding democracy was declare that Hawaii was a Christian country and all Hawaiians were equal), so a second constitution was written, and this one cut back some of the powers of the monarchy and added new democratic features. Equally important, the king issued a package of land reform laws called the Great Mahele in 1848, which specified how to go about owning and purchasing property; in 1850 these were amended to allow foreigners the right to own property, too.

Both constitutions kept the king in charge, but there was a brief interruption of his reign, now called the Paulet Affair. France's subjugation of Tahiti had caused a war scare in both Britain and Hawaii, and in February 1843, a British frigate arrived in Honolulu Harbor. The frigate's captain, Lord George Paulet, had been informed by another British citizen that British nationals were being mistreated in Hawaii, so he seized the fort at Honolulu, raised the Union Jack over it, had his men destroy every Hawaiian flag they could get their hands on, and had the ship's band play “God Save the Queen” while he forced the king to surrender the whole country. However, the rumor Paulet had acted on was false; London had no plans to annex Hawaii, the Brits in the islands were doing just fine, and in July Paulet's superior, Rear Admiral Richard Thomas, came to Hawaii to formally restore the kingdom to a tearful Kamehameha. At the restoration ceremony, the king showed his thanks by saying, “Ua mau ke ea o ka aina I ka pono” (“The life of the land is preserved in righteousness”), and that became Hawaii's motto, both as a kingdom and as a US state.(49)

Up to this point the capital of Hawaii had not been in a fixed location; it was wherever the king's court happened to be. Kamehameha I had it on the Big Island most of the time, except when he was on expeditions to conquer the other islands, and after the battle of Kuamo'o, Kamehameha II alternated between Lahaina on Maui, and Honolulu on Oahu. Meanwhile, outsiders were coming in through several ports, but after the Hawaiian Islands were united they started gathering at Honolulu, turning it into a boom town. Good harbors are an important asset for a nation dependent on sea power, and it was obvious to foreigners that Honolulu had the best harbor of all. Kamehameha III got the hint, and moved his fledgling legislature from Lahaina to Honolulu in 1845; the port's growth since then made sure the capital would stay there.

Besides British meddling, there was also a case of French meddling. In August 1849, French admiral Louis de Tromelin arrived in Honolulu Harbor with two ships, and presented King Kamehameha III with a list of ten demands. France was upset that Hawaii had not fully complied with the 1839 treaty; Catholics still did not enjoy full religious rights, and the duties charged on French wine and brandy were too high. The king did not give in to the demands, so after a second warning, French troops captured Honolulu Fort, destroyed the coastal guns and stores of muskets and gunpowder, raided the home of the Oahu governor, and stole the king's yacht, the Kamehameha III. Because Hawaii wasn't strong enough to take on a major power like France, all the Hawaiians could do was wait until de Tromelin and his men sailed away; their raiding and looting caused a total of $100,000 in damages.

Kamehameha IV

Throughout Hawaii's ups and downs, Kamehameha III had been a popular king. He adopted a nephew, Alexander Liholiho, as his heir, and this nephew became King Kamehameha IV, a month before his 21st birthday. The fourth king's reign (1855-63) was much shorter than that of his predecessor, and it would be a time of dramatic changes, mostly economic. The main factor here was that the whaling industry, which had brought both money and vice to Hawaiian ports for most of the early nineteenth century, was past its peak.(50) Not only was the supply of whales getting low, but the demand for whale oil was declining, now that kerosene and coal lamps were providing alternate sources of light. Fortunately, other sources of income were already available. A few entrepreneurs had experimented with growing sugar cane, and though the sugar they produced wasn't as good as Caribbean sugar, it brought in a large profit during the California gold rush, because prices were high in California and the settlers on the US west coast could not get sugar from anywhere else. By 1860, Hawaii was producing and selling 1.5 million pounds of sugar per year. Other crops would follow; e.g., the first commercial pineapple plantation was started in 1886. However, the farms were largely owned by non-Hawaiians, and they were having problems getting Hawaiian workers, for the following reasons:

- The shrinking Hawaiian population.

- Many Hawaiian men were leaving the islands to take jobs elsewhere. To give one example, some, like the Maori, became crewmen on foreign-owned ships.

- The general attitude that Hawaiians were temperamentally unsuited for hard labor. The reason for this is same one that attracts tourists to present-day Hawaii; these islands have one of the most pleasant climates anywhere. People don't have to work hard in a place where life is as easy as it is here (see what I said about that in Chapter 1), and even when they were dirt poor, the natives were not likely to starve.

Speaking of foreign influence, when Kamehameha IV became king, American missionaries were suggesting that the United States should annex Hawaii. To keep this from happening, his foreign policy sought to reduce US influence, by improving relations with Great Britain (e.g., he invited the Church of England to build its first church in Hawaii), removing US citizens from cabinet posts in the government, and promoting trade with other nations.(51) His other big challenge was that the Hawaiian population was still losing people to foreign diseases, so in 1859 he established the Queen's Hospital in Honolulu to slow down that trend.

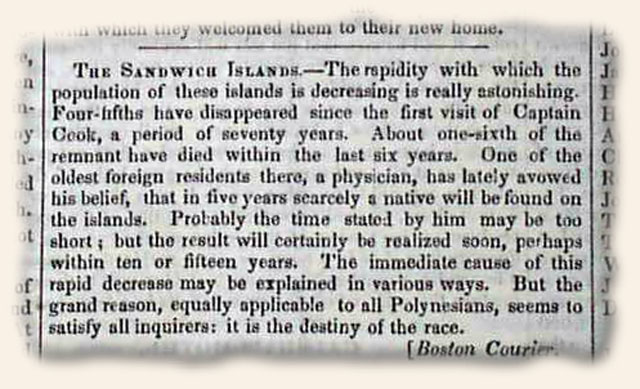

This contemporary newspaper clipping had a blatantly racist explanation for epidemics in the South Pacific. After the theory of evolution caught on, this attitude would be called “social Darwinism.”

The last years of Kamehameha IV were a long tragedy. In 1859, while drunk and in a fit of jealousy, he shot Henry Neilson, an American friend and his secretary. Neilson took two years to die from his wounds, and his suffering caused the king to feel guilt and remorse for what he did. Then in 1862 Prince Albert, his only son, died at the age of four. The shock from this probably shortened Kamehameha's life; he died of asthma just a year later. His older brother, Lot Kapuāiwa, was the only male candidate available, so he was proclaimed Kamehameha V on the same day.

Kamehameha V

The last Kamehameha (1863-72) seemed to be cut from a different cloth than the others. Instead of acting humble, he believed in the adage, “if you want something done right, you have to do it yourself,” and thus ran the kingdom as he saw fit. He started out by refusing to take an oath to defend the 1852 constitution, because he felt the constitution made the monarchy too weak. In 1864 he called for a constitutional convention, but when the delegates were deadlocked for several days over the issue of voter qualifications, the impatient king dismissed them, abrogated the 1852 constitution, and told the shocked nobles and legislative representatives, “I will give you a constitution.” One week later he presented a constitution that weakened the powers of the royal Privy Council, merged the two houses of the legislature into one, and required anyone born after 1840 to pass a literacy test and own property in order to vote. Though his action was in effect a bloodless coup from the top (in Latin America, such a move is called an autogolpe), it allowed his reign to be a mostly successful one. It showed in the booming sugar industry; sugar sales during his reign expanded from 5.3 million pounds in 1864, to 17 million pounds by 1872.

Kamehameha V was also launched a number of building projects that included a central post office, a government office building called the Aliiolani Hale (the present-day state Supreme Court building), the 'Iolani Barracks for the Royal Household Troops, the first major hotel in Honolulu for tourists, and the Hawaiian Steam Navigation Company to transport cargo and passengers between the islands. He probably spent too much here, because he left Hawaii with a national debt, which reached $355,000 by the end of 1874. In other activities he hosted hula performances, which had been suppressed after the Hawaiians became Christians (see footnote #47), and made traditional “kahuna medicine” legal again. On the other hand, he refused to sign a bill that would have legalized the sale of hard liquor to native Hawaiians, because he knew how much trouble alcoholism was causing, and said, “I will never sign the death warrant of my people.”

There were two areas in which Kamehameha V could not get his way. One was fair trade with the United States. In 1865 and 1867 he proposed a reciprocal trade treaty; the US Civil War caused the American Senate to ignore the first treaty, and it voted against the second one. His other failure was the succession. Because he had never married, the king initially named his sister Victoria Kamamalu as his heir, but she died in 1866. After that he did not appoint another successor. He died on his 42nd birthday in 1872, and an hour before the end, he asked Bernice Pauahi Bishop, a great-granddaughter of Kamehameha I, to take the throne, but she refused. Thus, the Kamehameha dynasty came to an end.

William Lunalilo and David Kalakaua

The 1864 constitution declared that if the throne became vacant, the legislature would elect a new king from among the available chiefs and chiefesses, and that person would found a new dynasty. The candidates who ran were William Charles Lunalilo, Colonel David Kalakaua, and Ruth Keelikolani; the latter was quickly eliminated as a contender, making it a contest between Lunalilo and Kalakaua. Everyone agreed to let the people decide with a plebiscite on January 1, 1873, and because Lunalilo was more popular and more closely related to the Kamehameha family, he won easily. Therefore the legislature's vote became a formality; after confirming the popular vote they elected Lunalilo unanimously, so it would not look like they were going against the will of the people.

Lunalilo, nicknamed “Prince William” and “the People's King,” was the most liberal Hawaiian king; he wanted to amend the 1864 constitution to make it more democratic. Another goal was a trade treaty that would allow Hawaiian sugar to enter the United States without being taxed, but the Hawaiians balked at what the Americans wanted in return – a US coaling station in the Pearl River Lagoon, today's Pearl Harbor. He didn't make much progress on either item; barely a year after he was crowned, he died from a combination of tuberculosis and alcoholism.

Like his predecessor Lunalilo was a bachelor, forcing the legislature to go through the sticky business of electing a king again. This time the two candidates were David Kalakaua and Queen Emma, the widow of Kamehameha IV. The legislature voted 39-6 in favor of Kalakaua, and though this meant another landslide win, Queen Emma's supporters rioted in protest. One person was killed and several injured at the courthouse where the voting took place, and American and British marines from visiting warships had to be called in to restore order.

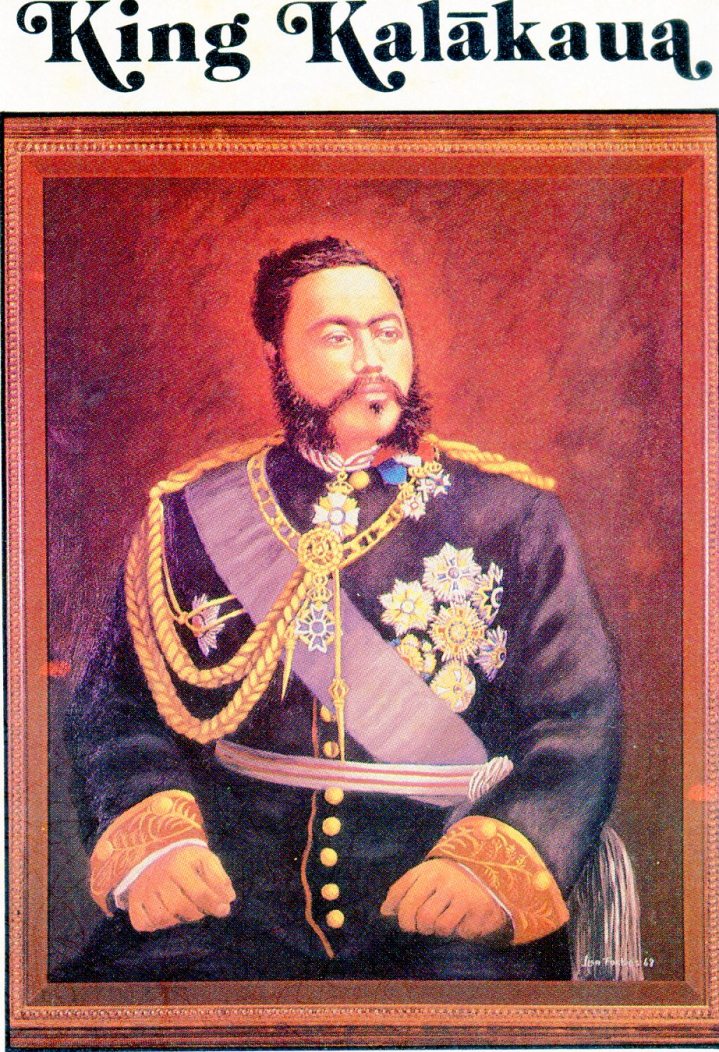

That riot prompted Kalakaua to accept his victory modestly, without the lavish celebration he had planned. However, afterwards he went back to enjoying the good things of life, such as music, dancing, parties, and good food and drink. Consequently he came to be known as the Merry Monarch, putting Hawaiians in a good mood for most of his reign (1874-91). One of his first acts as king was to make a goodwill tour of all the Hawaiian Islands, and the people were delighted to meet him. At the end of the year he went to Washington, D.C. to meet US President Grant, becoming the first reigning monarch to visit the United States. Subsequent negotiations allowed him to get the reciprocal trade treaty that had eluded the two previous kings.

In 1881 King Kalakaua and his queen, Kapiolani, embarked on a grand tour around the world, becoming the first monarchs to circumnavigate the globe. Inspired by the pomp of the British royal court, he had two jeweled crowns made for himself and the queen, at a cost of $10,000. Then upon their return, he decided he needed a more luxurious palace, and had 'Iolani Palace built for $300,000. When it was finished in 1883, Kalakaua used it for the official coronation ceremony he had skipped nine years earlier. All these expenses were small by the standards of European royalty, but for Hawaii they were unheard-of amounts. While this caused some to grumble about the king spending too much, it's just as well he celebrated when he could, for soon afterwards came events that would mark the beginning of the end of the Hawaiian kingdom.(52)

The trouble came from haole immigrants, who as we noted earlier were growing in numbers and had gained control over the economy, though not the government. They resented Kalakaua's policies, which kept political power out of their hands, and blamed the kingdom's growing debt on the king's spending habits. Some whites merely wanted the king to abdicate in favor of a ruler who would give them what they wanted, others wanted to get rid of the monarchy completely and have Hawaii join the United States. The latter formed a group called the Hawaiian League, and it was led by Sanford B. Dole, who currently represented Kauai in the legislature and was a cousin of the Dole who founded the Dole fruit company. On their side was the Honolulu Rifles, a small volunteer militia of haole soldiers. One day in 1887 the Hawaiian League and the Honolulu Rifles stormed the palace, woke up the king, and forced him to sign a new constitution at gun point. This document, henceforth known as the Bayonet Constitution, reduced the king to a figurehead; real power was now held by the cabinet, which was entirely made up of white landowners.

In November 1890, an ill Kalakaua sailed to California for medical treatment. Two months later he died of kidney failure at a hotel in San Francisco. Because he had no children, he had named his sister Lili'uokalani heir in 1877, so now she took over as the last Hawaiian monarch.