| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

A Concise History of Korea and Japan

Chapter 4: The War-Ravaged Years

Korea from 1910 to 1953, Japan from 1912 to 1945

This history paper covers the following topics:

Korea: Pax Japonica

The period when Japan ruled Korea (1910-45) saw political suppression, economic exploitation, and social and educational discrimination. Koreans were deprived of freedom of assembly, association, the press, and speech. Many private schools were closed, and the new schools set up in their place tried to Japanize the natives, placing heavy emphasis on teaching the Japanese language and excluding subjects like Korean history. The Japanese also actively invested in Korean businesses and built a nationwide transportation and communications network, while barring Koreans from similar activities. Landowners were required to report the size and area of their land, and if they failed to do so, the Japanese confiscated it; they also appropriated fields and forests owned jointly by a village or clan because no single individual could claim them as his own. That land was sold cheaply to 700,000 Japanese settlers, who moved to take advantage of Korean resources and cheap labor. Western-style transportion, communication and banking networks were established across the peninsula--not for the benefit of the Koreans, but so the Japanese could squeeze as much in labor and resources out of Korea as possible; Most of these networks would be destroyed later, during the Korean War.

After World War I a Korean delegation went to Versailles and failed to persuade the Allied leaders that they were an oppressed people with a right to self-determination. Then came the death of former Emperor Gojong, the supreme symbol of national independence (at the time there were rumors that he had been poisoned). A few days later (March 1, 1919), while mourners from all over the country were gathering in Seoul, 33 Korean cultural and religious leaders signed a "Proclamation of Independence," which they read at a huge rally. This movement, now known as the Samil Independence or the March 1 movement, spread like wildfire; two million people are estimated to have taken part in 1,500 demonstrations throughout the country. The Japanese reacted brutally, killing or wounding nearly 23,000 in clashes and arresting 47,000 more, but afterward they tried to prevent future demonstrations by giving the Koreans freedom of the press and a small measure of self-government.(1) Other independence movements broke out from time to time, but Japan remained in full control until the end of World War II.

The beginning of Japan's long war with China in 1931 brought Korea under military rule again. Japan now made a determined effort to obliterate Korean civilization, by forcing Koreans to worship at Shinto temples, banning newspapers and magazines published in Korean, and ordering Koreans to adopt Japanese names. The peninsula became an important economic and military base for Japan's continental expansion. Hundreds of thousands of able-bodied Koreans were drafted to fight for Japan and work in mines, factories, and military bases. Because Japan's industrial development caused a decline in agricultural output at home, Korean crops were diverted to make up for the food shortage. Most Koreans ended up living on low-quality grains imported from Manchuria because their own rice was no longer available. And the imposition of Shinto and Japanese Buddhist sects on Korea made the Koreans receptive to Christianity, which forbade observance of Shinto rites; that is why many South Koreans became Christians after Japanese rule ended in 1945.

Japan: The Militants Take Over

Japan's victories against China and Russia near the beginning of the twentieth century gave it an appetite for more imperialist gains. When World War I broke out, the Japanese ordered the Germans to remove their warships from the Far East and to surrender their Chinese outpost at Kiaochow (modern Qingdao). When the Germans did not reply to this order, Japan declared war and seized the territory. Because Europe was where most of the action was in this war, the Japanese were done by the end of 1914, and had only lost 300 soldiers, compared with hundreds of thousands, sometimes more than a million, lost by each major European nation.

Then in 1915 Japan presented China with the Twenty-one Demands, a document whose frank statement of Japan's claims on the Asian continent startled the world. The Chinese government, weakened by a half century of decline and revolution, could do little but give in to most of the demands, reserving five for further consideration. Nevertheless, the Chinese had no choice but to recognize Japan's authority in northeast China and extend the Japanese land and rail concessions in Manchuria. In 1917 the Allies had to secretly agree to support Japanese gains and claims to date, to keep Japan on their side for the rest of the war. After the war ended, the Treaty of Versailles rewarded Japan with the islands formerly occupied by Germany in the north Pacific: Palau, the northern Marianas, Marshall and Caroline Islands.

In the Russian Civil War (1918-20), American, British and Japanese soldiers landed at Vladivostok and advanced up the Trans-Siberian Railway for several hundred miles, officially to recover Allied equipment that had been shipped to Russia, but actually to help whoever was fighting the Bolsheviks. At first each country agreed to send only 7,000 troops to Siberia, but soon Japan increased its involvement to 72,000 men. Incidentally, the Japanese also occupied the northern (Russian) half of Sakhalin Island, and tried unsuccessfully to get permission to build a military base in Mongolia. The Americans and British realized that the Japanese were looking to make some permanent gains, and they spent most of their time talking Japan out of it. It was not until 1922 that the last Japanese troops departed from east Siberia, and 1925 when they evacuated north Sakhalin; this was long after Communism had triumphed in the rest of Russia.

Siberia wasn't the only case where Japan's allies applied the brakes to Japanese expansion. Whereas the Russians had been the biggest bully in the Far East before 1905, nobody doubted who was doing the bullying now. The idealistic United States wanted to see the world become a place that respected the rule of law, with less of this "might makes right" business. That is why the League of Nations referred to the islands Japan got in the Versailles Treaty as the "Japanese Mandated Islands," the idea being that while Japan ruled them, it would also prepare the native population for self-government. At the Washington conference of 1921-22, pressure from the United States and Britain forced Japan to sign a treaty limiting the size of the navy to a 3-5-5 ratio (three Japanese warships for every five American and five British).(2) In 1922 the Americans followed this up by persuading Japan to return Kiaochow to China.

The British went along with what the United States was doing because they came to believe they could no longer be friendly with the Americans and Japanese at the same time. The British Empire, like Japan, had come out of World War I with some new colonies taken from Germany, but the truth was that Britain was no longer as powerful as it looked. In industrial output Britain had slipped behind Germany and the United States since the mid-nineteenth century; moreover, British resources had not kept up with London's growing commitments. The result was that Britain needed American help to win the war, and Britain's leaders realized that the next time international relations turned ugly, they would need the Americans again, either to keep the balance of power in Europe, or to come to the rescue if British colonies in the Atlantic or Pacific were attacked. Therefore, when the treaty between Britain and Japan expired in 1921, Britain did not renew it. However, isolationist sentiment soon caused the Americans to get tired of playing the world's policeman, so when the military returned to power in Tokyo, Japan would be able to resume empire-building activities.

The military wasn't running things in the 1920s because it had lost much of its influence, due to it gaining nothing from the Siberian venture, plus the diplomatic setbacks. Instead, the 1920s saw a contest for power among the groups that had taken part in the country's modernization: the army, navy, civil bureaucracy, the first political parties, and the Zaibatsu industrial combines (the handful of big corporations that dominated the economy). Domestic politics were frequently unstable, especially when the economy was bad. Many politicians, including one prime minister, were assassinated, and control of the Diet changed hands regularly with each election. In 1925 came two major pieces of legislation: universal male suffrage, and the "Peace Preservation Law," which gave the police great powers in suppressing "dangerous ideas" and specifying prison sentences up to ten years for membership in any organization that advocated major changes in the government or the abolition of private property (meaning the communists).

As was the case in Europe, while the economy was strong, the liberals did well. In the 1920s the Japanese built thousands of factories that turned out products that enabled Japan to claim a major share of the world textile market and to flood the world with mass-produced, cheap, low-quality goods. Japanese industrialists were quick to adopt modern machine techniques, until a few giant firms working together controlled the greater part of the country's wealth.

Prosperity--and by implication the liberals' position--rested on fragile foundations. Japan lacked natural resources, and its population grew at a rapid rate. In 1920 there were more than 55 million inhabitants; eleven years later there were 65 million. By 1932 the annual population increase was one million. The Japanese economy had to create 250,000 jobs yearly and find the food to feed the growing population. Until 1930, Japan did it by expanding its exports. But between 1929 and 1931, the effects of the Great Depression cut export trade in half. Unemployment soared, leading to wage cuts and strikes. As in Germany on the eve of Adolf Hitler's rise to power, economic hard times discredited the ideas of liberal politicians and big business; frustration increased geometrically.

Emperor Hirohito enjoyed the longest reign in Japanese history (1926-89); he called it the Showa or "Enlightened Peace" era, but the first nineteen years were anything but that. The domestic situation was tense for the following reasons, in addition to those mentioned above:

1. Suppression of labor movements and intellectuals, strict pro-state education, censorship, and other police-state behavior.

2. Public apathy to the political parties, which were compromised by financial scandals, incidents of bribery and questionable ties to business.

3. Anti-democratic activities by the army & navy, such as the assassination of liberal politicians and moderate officers.

4. The increase of nationalism, with Shinto ideals (loyalty to the divine & untouchable emperor, a sense of mission, etc.) as its basis. This paved the way for the return of militarism.

The political pot boiled over in February 1936 when the liberals won the elections; 1,400 troops led by lieutenants and captains boldly occupied the prime minister's house, the Diet, the War Office, and police headquarters. The emperor ended the mutiny by ordering the troops back to their barracks, but the damage to democratic procedure had been done. A new prime minister, Prince Konoye Fumumaro from the venerable Fujiwara family, was chosen; he was acceptable to every faction but too weak to bring the military back under control.

A group of ultranationalistic and militaristic leaders was now running the country; they did not rule through a charismatic leader, the way their Fascist counterparts in Germany and Italy did, but through a military clique. The members of the clique, who had nothing but contempt for democracy and peaceful policies, terrorized the civilian members of the government, plotted to shelve the Diet, and used "incidents" against Japanese interests in China as excuses to use force on the Asiatic mainland. Their goals were to gain resources for the economy, living space for the population, markets for Japanese goods, and cultural domination throughout Asia. They referred to their program as a "beneficial mission" and called it the "New Order in Asia." The military clique had already taken its first step with the invasion of Manchuria in 1931. As far as China was concerned, World War II began early.(3)

World War II

China

On the outset Japan's attacks on China looked like a pygmy assaulting a giant, but while China was big, it was also flabby, broken into warring segments, and nearly defenseless. The hand of the Chinese central government, led by Chiang Kai-shek, extended weakly, or not at all, into most of the country. Furthermore years of famine and corruption had left most of the country impoverished, and among the many factions only the communists had high morale. As a result, when the all-out invasion of China Proper began (July 7, 1937), the Japanese easily took the coastal cities first, then moved up the rivers and spread inland. But the giant was too big to swallow. There was still enough land left for most Chinese units to defend themselves by simply running away, and though the Chinese almost never won, they succeeded in slowing the Japanese advance to a crawl, and tied down the bulk of the Japanese armed forces for all of World War II.

None of the great powers that might have halted the Japanese advance into Manchuria and China Proper did anything. The Chinese appealed to the League of Nations, which appointed a committee of inquiry in 1933. The committee's report condemned the aggression, but at the same time tried not to provoke Japan. The outcome was that the League did not put an end to the aggression and could not keep Japan as a member--two years later Tokyo withdrew from the organization. On the national level, Britain and France did not get involved because they were in the depths of economic crisis and political paralysis, the United States was totally absorbed in fighting the Depression, while the Soviet Union was busy with Joseph Stalin's five-year plans, and his political purges.

Siberia or the Pacific?

Japan's generals told the emperor that China would be finished in a few months, but because the stakes were so much higher, the Second Sino-Japanese War could not be as easy as the first one. Whereas in the last war the primary objective was expelling the Chinese from a land that had never been theirs (Korea), now Japan was out to conquer all of China. To keep going, Japan would need resources that China didn't have, especially oil and metals. They could get them from Siberia, though, and Adolf Hitler's activities in Europe gave the Japanese hope, for Hitler hated communism and was likely to go to war against the Soviet Union some day. Whenever that happened, the Japanese would have a chance to grab some Siberian territory. But when the Japanese tested the strength of the new Red Army, they realized the Russians were no longer pushovers. In two clashes along the Manchurian border, one near Vladivostok (the battle of Lake Khasan, 1938), and the other on a Mongolian river (the battle of Khalkhin Gol, 1939), the Japanese got the worst of the fighting.

Meanwhile the Nazis signed a nonaggression pact with the Soviets, and that really left the Japanese scratching their heads, but not for long. One week later Hitler started the European phase of World War II by invading Poland, and this meant the nations of Europe would concentrate their forces and attention there, leaving little to spare for their colonies or interests in the Pacific. That could only be good for Japan, but what Hitler did in 1940 helped even more. That spring the Germans struck west, and aside from the battle of Dunkirk, where the British army escaped annihilation, everything went right for Germany; in two lightning campaigns the Germans crushed Denmark, Norway, the Low Countries and France. Now if the Japanese struck in Southeast Asia instead of Siberia, they would find the French and Dutch colonies easy pickings. French Indochina (modern-day Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos) was a fertile area for growing rubber and rice, while Dutch Indonesia had tin, bauxite, and most important of all, oil. Britain also had valuable colonies, such as Hong Kong and Singapore, and because the British were still alive and kicking, they would try to shore up the defenses of those colonies, but with the home island under attack from Germany, they couldn't do very much.

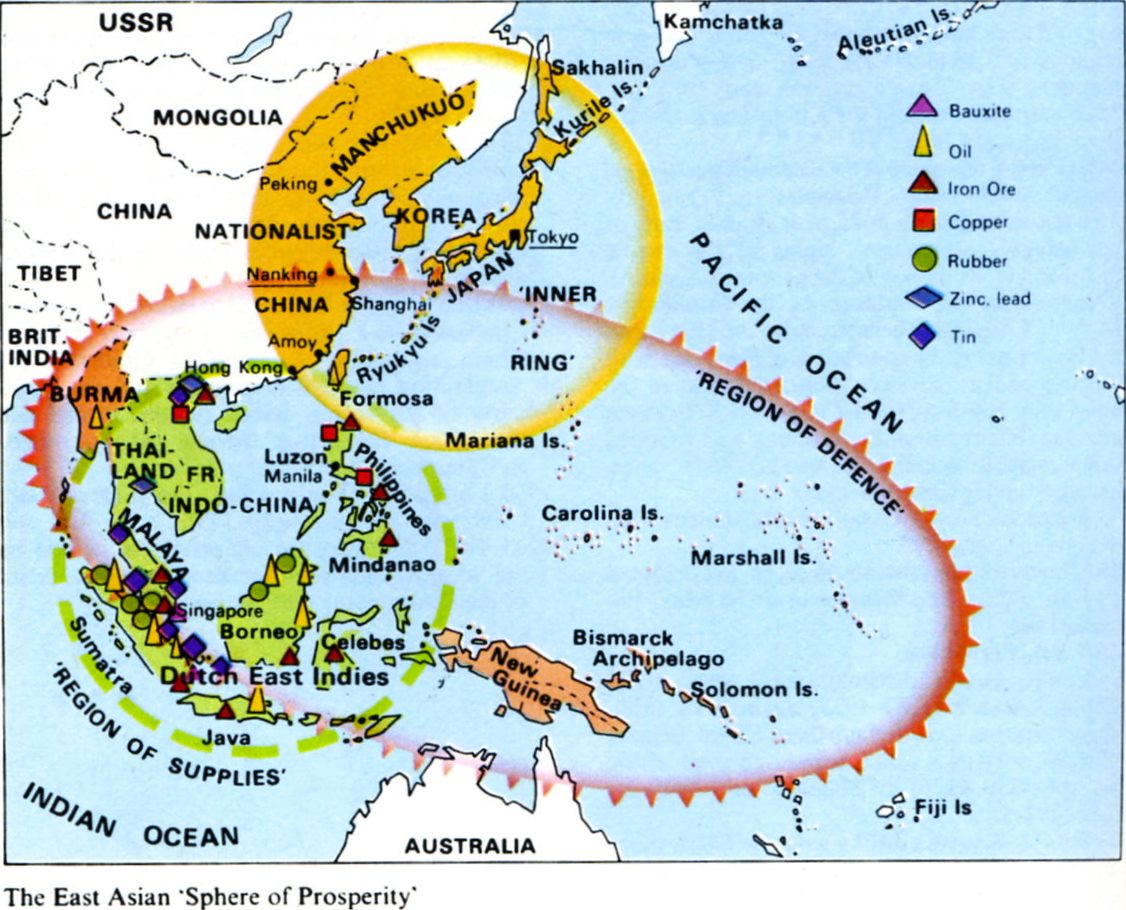

This map is a simple, graphic representation of Japan's wartime strategy. The area within the gold circle, what the Japanese called the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere," was under Japanese rule by the end of the 1930s. Then the Japanese became interested in the resource-rich green circle (most of Southeast Asia), and added that between 1940 and 1942, After Pearl Harbor they also went for the lands within the red oval, plus Wake Island and part of the Aleutian Islands on the right, as a defensive perimeter around the other areas.

Of course the Japanese took advantage of the opportunity Hitler gave them, by making the following moves:

1. (August 1940) Japan's generals forced the French to let them into the northern half of Indochina.

2. (September 1940) the Japanese foreign minister went to Europe to sign the Three Powers Pact, making the partnership with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy official.

3. Other Japanese diplomats began working on persuading Thailand to join their side.

4. (April 1941) And just as the Germans had done, Japan signed a neutrality agreement with the Soviets, to keep the USSR out of the war.

But there was still one nation willing to do what it would take to stop Japan--the United States. US-Japanese relations had continued to get worse because of the accidental sinking of an American gunboat, the Panay, in China, as well as from news reports of Japanese atrocities like the bombing of Shanghai. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt began applying pressure by building up the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, which was two thousand miles closer to Japan than the US bases on the west coast of North America. The pressure got worse when the Roosevelt administration canceled the trade agreements that allowed Japan to buy American scrap iron for Japanese steel mills. Worst of all, Japan bought its oil from the United States, so Roosevelt made it clear the United States would cut off the oil supply as well if Japanese aggression continued. This did not deter the militarists, and when Japan moved to occupy southern French Indochina in July 1941, Roosevelt kept his word. He ordered the Japanese to get out of Indochina immediately and begin negotiations to get out of China too; otherwise, they would only be allowed to buy enough oil to supply the country's needs for one month.

The Rise and Fall of Tojo

Prime minister Konoye saw three responses to American sanctions:

1. Agree to American demands, which would defuse the crisis but humiliate Japan.

2. Negotiate with the US for easier terms.

3. War with the West.

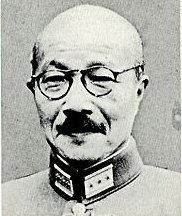

Konoye tried option #2, but could not reach an agreement; in October 1941 he resigned, and the emperor chose General Hideki Tojo to take his place. Tojo got the job because he had stayed loyal to the emperor during the 1936 coup, but he was also a rampant militarist. There was no turning back from here, as all political parties were dissolved and replaced by an authoritarian cabinet. Immediately Tojo began to prepare the country for war with the United States and Britain.

Hideki Tojo. Source: http://www.kantei.go.jp/.

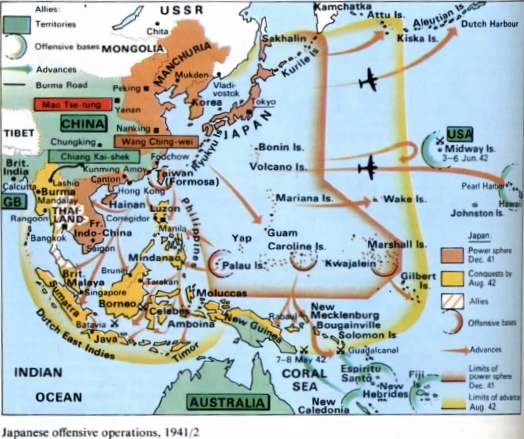

The Pacific theater of World War II began with a devastating surprise attack that sank much of the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The invasions that followed went faster than even the Japanese strategists had expected; by May 1942 much of the Pacific basin and every part of Southeast Asia, from Burma to New Guinea, was under the flag of the Rising Sun; only in the Philippines was there any resistance for long.

Now with all the original goals achieved except for the capitulation of China, Japan's main interest now became the defense and exploitation of her conquests, which were euphemistically named the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere." But this was not to be, now that America's industry and armed forces were fully mobilized. Japanese offensives were turned back at the Coral Sea, Midway Island, and on the Burmese-Indian frontier, and the Allied counteroffensive came from three directions:

1. Island-hopping across the Pacific from Hawaii, led by US Admiral Chester Nimitz.

2. Another island-hopping strategy from Australia to the Philippines, led by US General Douglas MacArthur.

3. A joint American-British-Chinese drive that liberated Burma by the end of the war.

The home islands themselves became subject to a war of attrition. Japanese merchant shipping was disrupted, and with each military defeat, shortages of food and supplies increased, while industrial production decreased. But what really made the war real to the civilian population were the American bombing raids. As early as April 1942, when the Japanese were still advancing on all fronts, Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle led the first American air raid on Tokyo. A series of false starts followed, over the next two years, before the Americans figured out which of their bombers worked best (the B-29), and the kind of tactics to use in a long-term bombing campaign. By February 1945 they were using incendiary weapons to burn out the centers of Japanese cities, where many of the buildings were still mostly made of wood. One of the fiercest firebombings, on March 9, 1945, incinerated sixteen square miles of Tokyo, and killed at least 70,000 people. Still, there was no sign that the air raids were breaking Japanese morale, either among the civilians or their unyielding leadership. The Japanese responded with desperate new tactics, like kamikaze pilots and hot-air balloons carrying incendiaries, but the longer the war went on, the more obvious it was that Japan had lost.

Because the Japanese fought back so tenaciously, it took several months months (two years in the case of New Guinea) for the Allies to liberate the islands Japan had captured in a matter of days. In China, the Japanese were still on the offensive even in early 1945. If you want to see the Allied offensives as a race, Nimitz was the winner; his task force was the first to reach territory that Japan had ruled before the war. In mid-1944 Nimitz took the Marianas Islands, and Tojo's failure to stop the Americans there ended his prime ministership; one month later he delivered his resignation to the emperor.

Iwo Jima and Okinawa

In February 1945 Nimitz moved to take Iwo Jima, in the Volcano Islands of the north Pacific. This barren eight-square-mile island had three airfields, which could be used for B-29 bombers on missions against the Japanese home islands, but the Japanese had also filled it with gun emplacements, tunnels, pillboxes and caves. Afterwards many questioned whether the battle of Iwo Jima was worth the cost; it lasted five weeks and 26,000 Americans were killed or wounded to kill or capture 19,000 Japanese. And after it was all over, the Americans did make use of the airfields, but the island turned out to be unsuitable as a naval base or a staging area for troops.

One thing Iwo Jima taught was that the closer the Americans got to Tokyo, the bloodier the battles would get. And because the war was expected to end with the Allies invading Japan, the US army would need an advance base for that operation. At first American strategists planned to use the south Chinese port of Amoy for that purpose; later they considered Taiwan. But in late 1944, the liberation of the Philippines began, and from the Philippines one could make an assault on the Ryukyu Islands, bypassing China and the need to cooperate with the unreliable troops of Chiang Kai-shek. Therefore Okinawa, the largest of the Ryukyus, became the preferred site for a base within striking distance of all Japan.

The initial landing on the north end of Okinawa went unopposed, because the Japanese concentrated their defenses on the south. The American force of 183,000 troops with 1,200 supporting navy ships was enough to make victory inevitable, but it took nearly three months (April 1 to June 22, 1945) to secure the island against suicidal Japanese counterattacks. In the end more than 12,000 Americans were killed onshore and more than 38,000 were wounded.(4) The navy paid a high price as well, from the hundreds of kamikaze aircraft that fell on the ships; it suffered 10,000 casualties, with 34 vessels sunk and 368 damaged. There never was an accurate count of the Japanese dead, for it is believed that many were trapped in underground caves; our best guess is that around 100,000 were killed. That includes Japanese civilians, women and children, who were either killed by the men or committed suicide, because they believed the Americans would rape and torture them if they were captured.

The Grim Endgame

Everyone expected the Allied invasion of Japan to be a lot like Iwo Jima and Okinawa, only worse. Called "Operation Downfall," it would be led by General MacArthur, now that he was done clearing out the Philippines, and by the summer of 1945 the plan was to have it proceed in two steps. The first phase, "Operation Olympic," it would have fourteen American divisions assault the southernmost of the main islands, Kyushu, in November 1945. Then in March 1946 would come "Operation Coronet," where twenty-five divisions would land on Honshu's Kanto plain, to take out Tokyo and as many other cities as necessary to end Japanese resistance. Both of these landings would be far greater than D-Day in Europe, which had five divisions come ashore on the first day. If the Japanese fought to the bitter end--and all the evidence said they would--there would be hundreds of thousands of Allied casualties, at least. For that reason, the Americans accepted help from the armies and navies of the Commonwealth nations (mainly the British, Australians and Canadians)(5), and the US government minted enough Purple Heart medals in advance to keep the armed forces supplied for the rest of the twentieth century. And you could be sure that millions of Japanese would fight to the death and/or commit suicide, civilians as well as soldiers. Only by breaking through the iron will Japanese culture had imposed on this extraordinarily disciplined population, could the war end without one of the biggest bloodbaths of all time.

An alternative to such an invasion became available on July 16, 1945, when the first atomic bomb was exploded in a test at Alamogordo, New Mexico. That bomb had the explosive power of 20,000 tons of TNT. The testers promptly informed the new president of the United States, Harry Truman, who had taken charge when Roosevelt died in April. Two more atomic bombs were built, and on August 6 one of them was dropped on the city of Hiroshima. The mid-air explosion obliterated two-thirds of the city; estimates of the number killed range from 60,000 to 240,000 (the high figure is valid if you count those who died years later from radiation caused cancer). Three days later, the other bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. In a move that the Japanese found just as shocking, the USSR voided the neutrality treaty on August 8 and launched an all-out invasion of Manchuria the next day. Whereas the Japanese had bitterly contested Allied advances on other fronts, every step of the way, the Soviet armored columns cut through Manchuria like a knife through butter. Within a week the Red Army had also invaded Inner Mongolia and South Sakhalin Island.

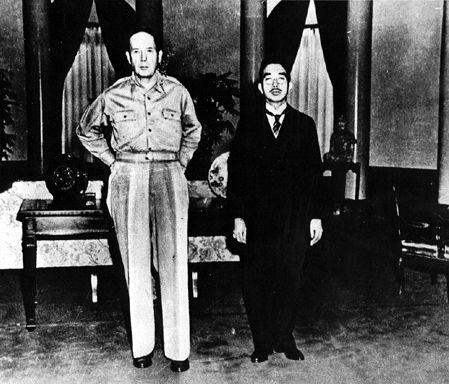

The next time the Japanese cabinet met, they had to consider a topic that was forbidden previously--how and when to surrender. Civilian members of the cabinet thought it should be done right away, while the army thought that it should fight one last battle, in the hope that Japan would get more favorable terms of peace if it won or forced a draw, and go out in a blaze of glory if it didn't. The emperor sided with the civilians and when the army refused to change its mind, that caused the emperor to act. In a rare public appearance on August 14, Hirohito ordered the country's surrender, pointing out to diehard militarists that "If we do not terminate the war at this juncture, our unique national structure will be destroyed and our nation will suffer extermination. If we save anything, be it ever so little, we could yet hope to rebuild the nation in the future." The formal terms of surrender were signed on the US battleship Missouri on September 2, 1945, and General MacArthur declared: "These proceedings are closed." That marked the end of World War II and the beginning of a new age for Japan.(6)

For the next 50 years the Japanese treated the war years as a closed book--especially concerning their country's role as an aggressor. Until the 1970s, high school texts did not mention that the war was caused by Japan invading its neighbors. The most popular books are war stories where the Japanese are the good guys, sometimes even winning the war. In these novels and in movies, Japanese soldiers suffer hardships and act heroically; they do not force 76,000 starving American and Filipino prisoners to walk for days on the Bataan Death March, use live Chinese for bayonet practice, perform hideous medical "experiments" on unanesthetized victims or bind the legs of pregnant captives in labor so that mothers and babies die in agony. Even in Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Museum, which is full of searing warnings on what nuclear weapons can do, there is little mention of the jackbooted conquests that made America put that city in its bombsights.

Only recently has Japan begun to apologize for the wartime atrocities, possibly because the victimized countries are now trading partners.(7) There may also be a gnawing worry that those who do not know their past are in danger of repeating it. In 1991 Tokyo began sending troops abroad for the first time since 1945; even though they were UN peacekeepers, their presence was chilling, both to foreigners and to Japanese who want to forget the past. However, by working together in the postwar years, Tokyo and Washington have created an economic sphere that is larger and has brought prosperity to more people than anything envisioned by the militarists--and without firing a shot. That is an achievement worth remembering, too.

The Creation of North and South Korea

There were no battles fought on Korean soil during World War II; the peninsula is so close to Japan that it would have been impractical to do so without an Allied invasion of Japan at the same time. Military action was limited to a Soviet landing in North Hamming, the province closest to Russia, on August 9, 1945, and that was an offshoot of the Soviet Union's Manchurian campaign during the final days of the war.(8)

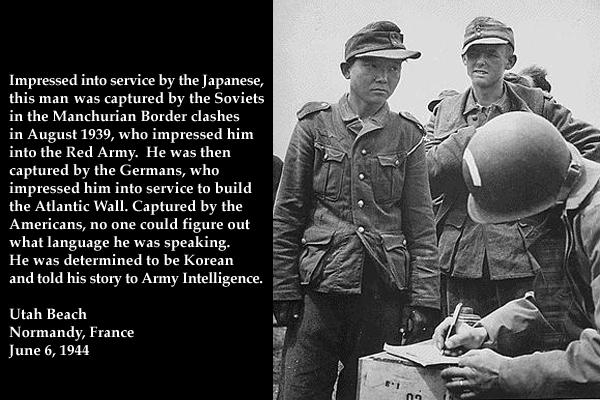

The above picture comes from D-Day by Stephen Ambrose, and it tells the strange story of three or four Koreans wearing German uniforms who were captured by American soldiers on D-Day. The man on the left is Kyoungjong Yang (1920-92). Born in North Korea, he was conscripted into Japan’s Kwantung army in 1938, captured by the Soviets at the battle of Khalkhin Gol (in Mongolia), and sent to the Gulag. After three years of hard labor he was drafted into the Red Army, captured by the Germans at the third battle of Kharkov in 1943, drafted into the Wehrmacht, and sent to Normandy, where the Americans captured him. He spent the rest of the war in a POW camp in Britain, and after the war ended he moved to Illinois, became a US citizen, and spent the rest of his life there. In the United States he had two sons and a daughter, but did not tell his incredible war story even to them. Finally, in 2011 his story was made into a Korean-language movie. The movie was called My Way, an ironic choice for a title when you consider that Yang was forced to fight for three dictatorships, making him the most unwilling soldier of all time. I don't know whether to call him lucky because he survived three major battles, or unlucky because he never saw his homeland after he grew up!

The leaders of the Allied nations had agreed in principle to restore Korea as an independent state. But US eagerness to obtain Soviet help against Japan, and the long-standing Russian interest in northeastern Asia, determined that occupation of the peninsula would be shared following the defeat of the Japanese Empire. A line was drawn at latitude 38o N., with everything south of it occupied by the United States, while everything north of it was administered by the Soviet Union.

The decision to divide Korea has aroused considerable speculation ever since. Some believe it was done merely to get the Japanese out; it took less time for them to surrender to two Allied nations than it would have taken to surrender to one. Others think the decision was already politically motivated at that early date; since Soviet forces were going to be somewhere in Korea after the war, American policy makers may have concluded that splitting Korea was better than letting Joseph Stalin have the whole thing.

For a while the Americans did not have a plan to return their half of Korea to civilian rule. Before the Japanese authorities in Korea surrendered, they allowed local nationalists to establish their own government, the short-lived People's Republic of Korea (PRK). But the general commanding the US occupation force, John Reed Hodge, saw the nationalists as communists, refused to work with them, and forced the government to disband in January 1946.(9) It wasn't until Syngman Rhee returned from the United States (see footnote #1) that the Americans found a nationalist they could trust. North of the 38th parallel, however, the Soviets allowed the PRK's local structure to remain until they could make it part of the state they were developing. The two allies established a joint commission to form a provisional Korean government, one that would include all Korean nationalists returning from exile, whether they were conservatives, moderates, socialists or communists. The plan was to create a united, independent Korea once the ravages of war had been repaired, but US-Soviet relations cooled first. The Soviets and the Americans soon disagreed on the legitimacy of the competing political groups that sought to govern Korea, and mutual suspicions mounted. The onset of the Cold War meant that neither superpower would allow unification except on its own terms.

In 1947 the United States asked the new United Nations to unite the northern and southern halves of the country. The 38th parallel hardened ominously, however, into an international boundary during the following year, with the establishment of the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the south and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the north. North Korea's regime drew on an earlier Korean Communist party, founded in exile in the 1920s, quickly becoming a Communist state with Stalinist-type emphasis on the power of its leader, Kim Il-Sung. South Korea, bolstered by ongoing American military presence, was headed by Syngman Rhee, who had also previously worked in exile against Japanese occupation. Rhee's South Korea developed parliamentary institutions, but maintained a strongly authoritarian tone. Elections were held in the south in May 1948, in fulfillment of the UN resolution. However, the Soviets considered the resolution non-binding, and refused to allow UN inspectors into the north. Therefore no voting took place in the north, and in December the UN General Assembly declared that Rhee's government was the only lawful one in Korea.

Kim Il Sung (a 1946 photo).

Syngman Rhee.

The arbitrarily set border split the peninsula both politically and economically into an industrial North and a primarily agricultural South, which was dependent on U.S. aid. By 1949 both the USSR and the United States had withdrawn most of their troops, leaving behind small advisory groups; the North Korean troops were much better trained and equipped than those in the South, however. Increasing hostility led to sporadic border clashes between North and South Koreans throughout 1949 and into 1950. In September 1949 a UN commission, after trying unsuccessfully to unify the country, warned of the possibility of civil war.

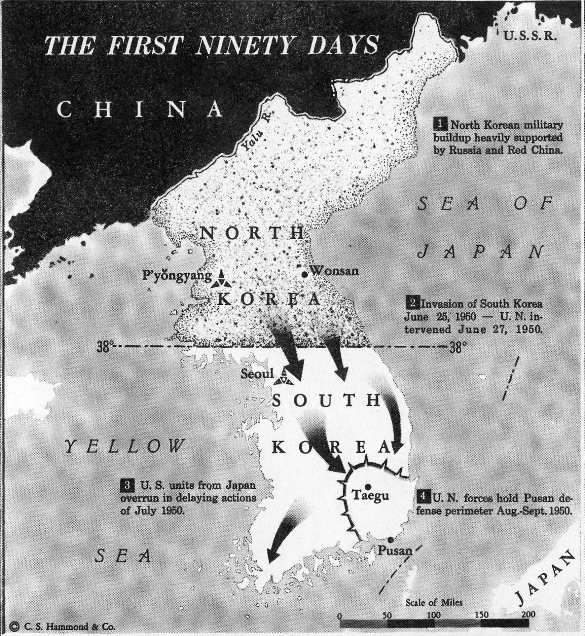

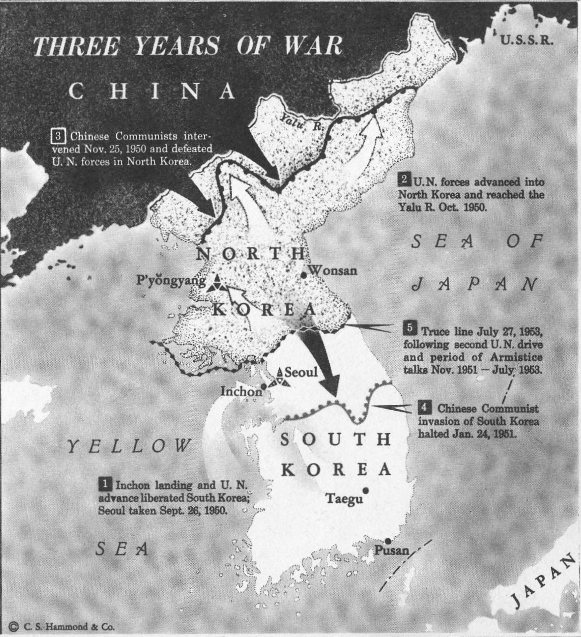

The withdrawal of US forces, and a speech (January 12, 1950) by Secretary of State Dean Acheson (which excluded South Korea from the US defensive perimeter in the Pacific), encouraged North Korea to take a bold military action. At approximately 4:00 AM on June 25, 1950, artillery of the North Korean Army opened fire on South Korean units standing watch along the 38th parallel. About 30 minutes later the first of about 80,000 North Korean troops crossed the border. At 5:30 AM the main attack, consisting of North Korean infantry and tanks, advanced along the shortest route between the 38th parallel and Seoul, the capital of South Korea. North Korean divisions also struck in the mountains of central Korea and along the east coast. Thus, the Cold War suddenly turned into a hot one.

The course of the Korean War, shown with an animated gif file. Communist-held areas are red, while land held by South Korean and UN forces is green. From Wikimedia Commons.

Reacting to initial reports of the fighting, the United States requested (June 25) an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council to discuss the situation. After confirming the details of the invasion and deciding that the attack was a breach of the peace, the Security Council called on the North Korean government to cease hostilities. Because it seemed clear by June 27 that the North Koreans intended to disregard the UN request, the Security Council met again to consider a new resolution, one recommending that "the members of the United Nations furnish such assistance to the Republic of Korea as may be necessary to repel the armed attack and to restore international peace and security in the area." After some debate the resolution passed. The USSR did not attend the Security Council meeting because it was protesting the exclusion of Communist China from the United Nations.(10)

In the meantime, US President Harry S. Truman conferred with Acheson and concluded that the USSR had directed the invasion. On June 27, Truman, without a congressional declaration of war, committed US military supplies to South Korea and moved the US Seventh Fleet into the Formosa Strait, a show of force meant to make China think twice about getting involved. Proceeding unilaterally, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) directed (June 30) General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, the American commander in East Asia, to commit his ground, air, and naval forces against the North Koreans. On July 7 the UN Security Council passed a resolution requesting that all member states wishing to aid South Korea make their armed forces available to the United States. By this resolution, President Truman became the executive agent for the UN on all matters involving the war in Korea, and MacArthur became the UN's commander in chief. Although the United States ultimately contributed most of the air and sea power and about half of the ground forces (with South Korea supplying the bulk of the remainder), MacArthur controlled the allied war effort of a total of 17 combatant nations (the largest contributors, after the United States and South Korea, being Australia, Canada, Great Britain, and Turkey). Five additional nations provided medical units.(11)

MacArthur's sole hope of saving the South Koreans from the superior Soviet and Chinese-trained North Korean forces was to hold the port of Busan (then called Pusan), at the southern tip of the Korean peninsula, until help arrived. He rushed reinforcements north to bolster the hard-pressed South Korean Army; on July 5, American units made contact with North Korean tanks and infantry just north of Osan. The Eighth Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Walton H. Walker, delayed the North Koreans north and west of the Naktong River, the last natural barrier protecting Busan. As the North Koreans pushed south toward the Naktong, however, Walker moved the Eighth Army into what came to be known as the Pusan Perimeter, a 150 mile-long front around the cities of Daegu and Busan, which survived only because of the timely arrival of reinforcements and American air superiority over the battlefield.

Beginning on August 5 the North Koreans launched a series of violent attacks against the perimeter in an effort to capture Daegu and Busan.(12) By September 12, however, reinforcements had greatly increased the combat power of the allies, and the North Korean offensive had spent itself.

Click on this map and the next one to see them full size (will open in separate windows)

With virtually all enemy units concentrated against Busan, the time for a counteroffensive had arrived. MacArthur had long planned a counterstroke against Seoul's port of Inchon, on the west coast behind enemy lines. For several weeks he had gathered forces in Japan to prepare for this counterattack, committing just enough men and materiel in Korea to keep Busan from falling. His sense of how much to send and how much to withhold helped transform his greatest gamble into his most brilliant military success.

Inchon, with its appalling array of tides and currents, was the worst sort of amphibious objective. The harbor was dominated by Wolmi-do, a small island which, if defended, could impede the landing and prevent tactical surprise.(13) Disregarding strong objections to his plan, MacArthur remained convinced that the advantages of seizing the Inchon-Seoul area were worth the risks of landing in Inchon Harbor. He made a daring amphibious landing at Inchon on September 15, successfully cutting the North Korean supply lines. In the days that followed, the Marines seized Kimpo Airport and Seoul while the infantry turned south to meet the Eighth Army, which was now pursuing a fleeing enemy north from the Pusan Perimeter. By October 1, 1950, the North Koreans had been pushed out of South Korea, and UN forces reached the 38th parallel.

In the meantime, President Truman's National Security Council advised against crossing the 38th, arguing that the ejection of the North Koreans from South Korea was a sufficient victory. The Joint Chiefs of Staff objected; contemporary military doctrine demanded the destruction of the North Korean Army to prevent them from invading the South again. MacArthur, they argued, would have to take the conflict to the North Koreans. On September 11--four days before the Inchon landing--the president adopted the arguments of his military advisors while retaining restraints recommended by the National Security Council to avoid provoking the Chinese and the Soviets. No UN or South Korean troops would enter Manchuria or the USSR, unless the Soviets or Chinese intervened before the scheduled crossing.

On October 7 the UN General Assembly passed a resolution calling for the unification of the peninsula and authorized MacArthur to send his forces into North Korea. In a conference with Truman at Wake Island on October 15, MacArthur was optimistic about a quick victory. The North Korean capital of Pyongyang fell on October 19, and the allied UN troops streamed north virtually unopposed. They pushed the North Korean forces to the Yalu River, on the border of China. By the end of the month, the fall of North Korea seemed likely.

In retrospect, the decision to cross the 38th parallel changed the course of the war. Beginning in late September, Communist China had warned of possible Chinese intervention if UN forces crossed the border, and during the second half of October, about 180,000 Communist "volunteers" had secretly crossed the Yalu. Not knowing the full extent of the Chinese commitment, MacArthur did not believe that a furious counterattack on October 25 was the beginning of Chinese intervention. By November 2, however, intelligence officers had accumulated undeniable evidence that Chinese Communist forces had joined the other side, and the UN Security Council was alerted to this fact.

After his troops replenished their depleted supplies, MacArthur launched a "home-by-Christmas" offensive on November 24. Although some UN and South Korean forces reached the Yalu, the Chinese army struck quickly and with full force. The United States 1st Marine Division, surrounded at Chosin Reservoir, fought to the sea in an historic march. Stunned, American and South Korean units began a second retreat that ended in January 1951, only after both sides had recrossed the 38th parallel and Seoul had once again fallen.

Lt. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgeway, who took over the Eighth Army after General Walker died (December 23, 1950) in a jeep accident near the front line, brought the UN withdrawal to a halt south of Seoul. Beginning on January 7, 1951, allied units began to probe north, opening an offensive that frontline troops came to call the "meatgrinder." Throughout January, February, and March, Ridgeway's men pushed on relentlessly until they once again crossed the 38th parallel. In early April the UN advance slowed temporarily as units consolidated strong defensive ground and braced themselves for an expected enemy counteroffensive.

In the meantime the defeat in North Korea had forced the UN to consider what should be done about China. MacArthur quickly charged that he was facing "an entirely new war" and that the strategy for war against North Korea did not apply in a war against China. MacArthur wanted more forces and a broader charter to retaliate against the Chinese, especially to conduct air operations against the "privileged sanctuary" of Manchuria. In this strategy, he was completely at odds with President Truman and other UN leaders who wanted a lesser commitment and a cease-fire. The UN General Assembly branded Communist China an aggressor in February 1951 and voted to subject it to economic sanctions. Its new war aim was to contain the Communist forces along the 38th parallel while negotiating an end to the conflict. Even in the dark days when the Pusan Perimeter was under siege, American leaders believed that restraint was necessary to avoid turning a local war into World War III. In particular, the administration feared that an invasion of China might cause it to invoke the Sino-Soviet treaty and the Soviets would respond by unleashing nuclear weapons against the United States or mounting a conventional invasion of western Europe. Consequently, the US administration opposed MacArthur's desire to expand his force so he could retaliate against the Chinese. In return, MacArthur disagreed with Acheson and Truman's policy of giving priority to Europe at the expense of the shooting war in Korea; he openly appealed to the public and Congress in an attempt to reverse the new war policy. During this period of cold-war tensions many Americans--most notably Wisconsin's Senator Joseph R. McCarthy--agreed with MacArthur's stand.

MacArthur had been a difficult subordinate. He had clashed with Truman over US policy toward Taiwan early in the war and complained about the restrictions placed on his forces and his freedom to wage the war. He publicly suggested that the policies of the Truman administration had been responsible for military setbacks. On March 25, 1951, just as President Truman put the finishing touches on a proposal calling for a cease-fire, MacArthur broadcast a bellicose ultimatum to the enemy commander that undermined the president's plan. Truman was furious; MacArthur had preempted presidential prerogative, confused friends and enemies alike about who was directing the war, and directly challenged the president's authority as commander in chief. Then on April 5, Joseph W. Martin, the minority (Republican) leader of the House of Representatives, released the contents of a letter from MacArthur in which the general repeated his criticism of the administration. The only way the president could respond to that was to relieve MacArthur from command. After MacArthur was fired, he returned home to a hero's welcome, Ridgeway moved to Tokyo to replace him, and Lt. Gen. James A. Van Fleet took command of the Eighth Army. On April 22, while Van Fleet's army edged north, the more than 450,000 Chinese opened a general offensive. Followed closely by this formidable force, Van Fleet withdrew below the 38th parallel, finally halting only five miles north of Seoul.

On May 10, the Chinese launched a second offensive, concentrating their main effort on the eastern sector of the front line. Van Fleet instead attacked in the west, north of Seoul. The surprised Communist units pulled back, suffering their heaviest casualties of the war, and by the end of May they were retreating into North Korea. By late June, a military stalemate had developed as the battle lines stabilized in the vicinity of the 38th parallel. Both sides dug into the hills and for the next two years waged a strange and frequently violent war over outposts between their lines.

In late June 1951 the Soviets proposed peace talks. Although both sides wanted a cease-fire, negotiating held different meanings for each side. The UN wanted above all to bring an end to the fighting and to defer political questions to a postwar international conference, while the Communists wanted to deal with political questions and a cease-fire at the same time. Because of that difference, the talks dragged on for two years before an armistice was finally concluded.

Negotiations were initially hampered by haggling over matters of protocol and the selection of a truly neutral site. On July 10, 1951, the full armistice delegations met at Kaesong, with Vice Adm. C. Turner Joy representing the UN command and Gen. Nam Il of North Korea representing the Communists.

On July 26 the two sides finally reached agreement on an agenda containing four major points: fixing a demarcation line and demilitarized zone, supervision of the truce, arrangements for prisoners of war, and recommendations to the governments involved in the war. Numerous problems arose, however, causing frequent suspensions of the talks, which in October resumed at a new site, Panmunjom.

One by one the issues were resolved until the only remaining obstacle was the handling of prisoners of war (POWS). The UN wanted prisoners to decide for themselves whether they would return home; the Communists insisted on forced repatriation. A lengthy stalemate developed, reflecting the battlefield stalemate along the 38th parallel. A series of Communist POW riots that erupted in May 1952 on Koje and Cheju islands only complicated the issue. Thousands of captured Red troops asked to stay in South Korea, and the United States would not repatriate any prisoner against his wishes. In order to force the Communists to negotiate in good faith, Gen. Mark Clark, who succeeded Ridgeway, increased air attacks over North Korea; on June 23, 1952, these air strikes destroyed major hydroelectric installations on the Yalu.

By April 1953 the POW deadlock was finally broken, and the first prisoners were exchanged at Panmunjom under a compromise that permitted prisoners to choose sides under supervision of a neutral commission. During this dramatic episode, the US was troubled to learn that hundreds of American soldiers--after communist brainwashing--had collaborated in various degrees with their captors; 21 Americans chose to remain behind in China. Not satisfied with a truce that did not result in the unification of Korea and totally voluntary repatriation, Syngman Rhee disrupted the proceedings on June 18 by releasing about 25,000 North Korean prisoners who wanted to live in the South. To gain Rhee's cooperation, the U.S. government promised him a mutual security pact, long-term economic aid, expansion of the South Korean Army, and coordination of goals and actions in future international conferences.

On July 27, 1953, an armistice was signed, without the participation of South Korea, and the shooting phase of the Korean War came to an end. Although the precise number of Chinese and North Korean casualties is unknown, estimates of total losses range between 1.5 and 2 million, plus perhaps a million civilians in the north.(14) The UN command suffered a total of 88,000 killed, of whom 23,300 were American. Add those wounded or missing, and the total UN casualties were 459,360, including 300,000 South Koreans. Another million civilian casualties were incurred in South Korea. In addition more than 40 percent of the industry and a third of the homes in the country were ruined.

Politically and militarily the war was inconclusive. The two armies continue to watch each other over the demilitarized zone, a 2.5-mile band stretching 155 miles across the Korean peninsula, waiting for the day when the fighting might begin again. South Korea and the United States concluded a mutual defense treaty in 1954; American troops levels were reduced, but the South Korean army gained more sophisticated military equipment and the United States poured considerable economic aid into the country, because in the 1950s and part of the 60s, that war-ravaged land was in danger of starvation.

Korea was no closer to unification; the war only served to intensify bitterness between North and South. The truce has been an uneasy one, marked by frequent border skirmishes which made it necessary for the United States to keep 40,000 troops stationed along the DMZ on a permanent basis. Since 1953 Korea has continued its dual pattern of development; South Korea went from democracy to military dictatorship and back to democracy again, while North Korea produced an unusually isolated dictatorship that concentrated all power in one family, that of Kim Il Sung. No treaty formally ending the war has been produced, and reunification talks have been held periodically since 1972 without results.

The Korean War had other important results in the arena of international diplomacy. It contributed to the strained relations between Washington and Beijing. In addition it added a new military dimension to the U.S. foreign policy of containment, which had heretofore been implemented by political and economic measures, including military aid. Originally formulated by George F. Kennan, developed by Dean Acheson, and advanced by John Foster Dulles, the containment policy led to US military involvement in Vietnam during the 1960s.

This is the End of Chapter 4.

FOOTNOTES

1. Today March 1 is a national holiday in both North and South Korea, because of the patriotism of those who took part in the movement, and because it was a training ground for the future founders of North and South Korea. Syngman Rhee (1875-1965), for example, had been a member of the Korean nationalist movement since 1896, and consequently had been forced to take refuge in the United States twice (1904-10, and again from 1912 on), where he converted to Christianity. Later in 1919, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea was established in Shanghai, China, and Rhee was elected its first president. After World War II the United Nations would recognize the Provisional Government as the official successor to the Joseon dynasty, and Korea's rightful government in exile.

A few years after the 1919 uprisings, one Kim Sung Chu (1912-94) changed his name to that of another leader in the March 1 movement, becoming Kim Il Sung. Kim's family fled to Manchuria in the late 1920s to escape the Japanese; consequently Kim had all his formal education in Chinese, and until he returned to Korea at the end of World War II, he spoke Chinese better than Korean. After he grew up, Kim joined the Communist Party in 1931, fought the Japanese occupation forces in the 1930s and commanded a Korean unit in the Soviet army in World War II, making himself the USSR's logical choice to lead a communist government in postwar Korea.

2. However, the treaty gave the Japanese a secret advantage. Britain had to divide its ships between three oceans (Atlantic, Indian and Pacific), while the US Navy had to patrol two (Atlantic and Pacific). Thus, Japan had a free hand to build its fleet to a commanding lead in the one body of water that mattered to the Japanese, the western Pacific.

3. Details of the WWII campaigns in China can be found in my Chinese history narrative. It would be redundant to repeat them here.

4. Among the dead was Ernie Pyle, America's favorite war correspondent.

5. In the wartime meetings between Franklin Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin, Roosevelt got a promise that the Soviet Union would declare war on Japan no more than three months after the war ended in Europe. This may be the only promise made in the 1940s that the Soviets actually kept. What Roosevelt didn't know was that the USSR drew up a plan to invade the northern island of Hokkaido, and probably would have carried it out if the Japan hadn't surrendered before they were finished with Manchuria. If the invasion had taken place, it would have left Japan a divided country during the Cold War era, like what happened to Korea, Germany, and Vietnam.

6. A number of Japanese soldiers stranded on distant islands continued to fight long after the war ended, because they had orders not to surrender under any circumstances. When they got separated from their units, they usually took to the hills and jungles wherever they were stationed, and waged a guerrilla war from there. Because of poor communications in that part of the world, most of them didn't hear the war was over for years, and when they did hear the news, they refused to believe it. Some of these "holdouts" even joined guerrilla movements from the next wars--Sukarno's nationalists in Indonesia, the Viet Minh in North Vietnam, and the Malayan communists--because in all cases these were Asians fighting Europeans. The most famous holdout was Lieutenant Hiroo Onada, who fought in the Philippines until 1974, when his former commanding officer personally went there and ordered him to lay down his sword and rifle, which he still had. Others who made headlines were Sergeant Shoichi Yokoi, captured on Guam in 1972; and Private Teruo Nakamura, who surrendered in 1975 on Morotai in Indonesia. When they returned to Japan, they did not like what they saw, because the country had changed too much during the years they were away. Reports of other holdouts popped up occasionally from 1975 to 2005, but none of them were verified.

7. Not until 1996 did Tokyo begin paying compensation to the women, mostly Koreans, who were used as sex slaves by Japanese soldiers. In 2015 Japan and South Korea reached an agreement where Japan would pay 1 billion yen ($8.3 million) in reparations -- the amount South Korea asked for -- to settle the matter once and for all. But by then only 46 of the 200,000 estimated "comfort women" were still alive.

8. The USSR's greatest triumph concerning Korea came after the war, when Soviet troops moved in to disarm and remove the Japanese forces remaining on the north side of the 38th parallel. In the process they captured the reactor that was the source of Japanese nuclear research, thereby gaining the knowledge and materials needed to build nuclear weapons.

9. Despite their suppression, a number of PRK units remained active in the southwest, especially on Jeju Island. They opposed the 1948 election, seeing it as an attempt by the United States to install a puppet regime. In April 1948 clashes broke out on Jeju between the nationalists and the police, which soon turned into a guerrilla insurrection against Seoul. The South Korean government responded by sending in troops and anti-communist youth gangs, and Syngman Rhee declared martial law over the island in November 1948. For those reasons, the rebels openly sided with North Korea after that, sometimes flying the North Korean flag. It took until the second half of 1949 for Seoul to crush the rebellion; the number of combat deaths and executions is estimated at 14,000-30,000, possibly one-fifth of the island's population. In addition, more than half of the island's villages were destroyed, and some 40,000 refugees fled across Tsushima Strait to Japan.

For almost fifty years afterwards, the South Korean government made it a crime for its citizens to even mention the Jeju uprising. It did not issue an official apology to families of the victims until 2006, and while reparations have been promised, they have not been made yet.

10. In retrospect, this turned out to be a grave error, for without the Soviet veto the UN was able to pass resolutions supporting the South Korean government, meaning that the United States and South Korea would not have to fight alone.

11. North Korea may be the most repressive state in today's world (see the next chapter), but alas, it now that appears that South Korea committed the worst wartime atrocity. This occurred because South Korea wasn't really a democracy yet, despite the recent election. When the war began, Rhee had 30,000 political prisoners in jail, and another 300,000 in "re-education" camps. Besides communists and communist sympathizers, these included collaborators with the Japanese in the previous war, and political opponents. Many of the latter belonged to a movement called the Bodo League, which gave its name to this massacre. On June 28, Rhee ordered the executions of the communists and Bodo League members, to keep them from falling into the hands of the North Koreans. During the next two months mass executions took place without trials; at least 100,000 were killed, and there may be more victims we don't know about. Most of the bodies were buried in mass graves, and some were thrown into the sea. American soldiers in Korea knew what was happening, but did not try to stop it. As with the Jeju uprising (see footnote #9), details of the Bodo League Massacre were suppressed or forgotten until after the turn of the century, when the Truth and Reconcilliation Commission brought them forth for everyone to see.

12. Because Seoul changed hands four times in 1950 and 1951, and was largely destroyed in those battles, the South Korean government stayed at Busan for the rest of the war.

13. Wolmi-do must have reminded General MacArthur of Corregidor, which guards Manila's harbor in the same way.

14. The Chinese drove the UN and South Korean forces back to the 38th parallel through waves of human assaults, expending men at the rate other armies expend bullets. Since China's civil war had ended less than a year earlier, many of the soldiers in the People's Liberation Army didn't have guns, and stayed in the rear until they saw an opportunity to grab a rifle from a fallen comrade. Among the Chinese killed was Mao Anying, the son of Mao Zedong.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A Concise History of Korea and Japan

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|