| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Latin America and the Caribbean

Chapter 3: A New World No More, Part I

1650 to 1830

This chapter is divided into three parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| Growing Trouble between Spain And Her Colonies | |

| Brazil: Movement Inland, and to the South | |

| The Haitian Revolution | |

| The Liberation of Latin America Begins | |

| Bolívar and San Martin | |

| The Haitian Monarchy |

Part III

| Bolívar's Campaigns | |

| Early Paraguay: Marxism Before Marx | |

| Over the Andes | |

| Gran Colombia | |

| The First Mexican Empire | |

| Brazil: Independent By Accident | |

| All Roads End At Ayacucho | |

| The Falklands Dispute Begins | |

| The Shattered Dream |

A Hollow Empire

The Spanish Empire must look curious to the casual reader -- it has a beginning and an end, but not a middle. If you don't count Cuba and Puerto Rico, which Spain held until 1898, the Spanish Empire lasted 333 years in the New World, from 1492 to 1825. There was plenty of activity in the first ninety-six years (1492-1588, from Columbus to the Armada), and in the last sixty-three years (1762-1825, from the Seven Years War to liberation), but not much from the 174 years in-between.

When I completed the previous chapter, I was asked why I chose to end it at 1650. After all, the chapter began with 1492, a year that even non-historians know was critical, but 1650 wasn't such a year. Well, my choice of 1650 for the year to divide Chapter 2 from Chapter 3 is purely arbitrary; any year between 1588 and 1762 would have worked here. Of course, a lot of people don't mind living in a year when nothing happened. The typical historian likes to write about wars and other disasters, which is just what the rest of us don't want. Hence, the historian will quickly skip over years that were peaceful but dull, and you may have heard the Chinese curse, “May you live in interesting times.”

It was a similar story with the Portuguese Empire. This empire lasted as long as it did because after Portugal regained independence from Spain in 1640, it stopped attracting attention from others. The Portuguese did not threaten the colonies or commerce of any other empire, and they stayed out of European politics. Between 1640 and 1801, the Portuguese only got involved in two conflicts, the War of the Spanish Succession and the Seven Years War, and in both they were minor participants; they didn't fight at all in the first war, and only fought briefly in the second. But while most of the empire, from Madeira to Macao, took the form of sleepy outposts, Brazil became the place to be, especially after Portugal's royal family moved there.

The Jesuit Experiment

In the previous chapter we began to discuss Church activities in Latin America. Chief among the Catholic missionaries were the Jesuits, who saw the conversion of natives as the “spiritual conquest,” and while they enjoyed success in many areas, their greatest achievement was converting the Guarani Indians in Paraguay. In doing so they did not just build churches and teach the tenets of Christianity to their converts; they launched a social experiment by gathering the Indians into model communities, called reductions.

The typical reduction was managed by two or three Jesuits. It had a large grassy square at its center, with the community church on one side and longhouses on the other three sides. The longhouses were made of sun-dried bricks or wattled canes, and could hold more than a hundred families; each family had a private apartment within the structure. The Guarani did not have to work very much, when they lived by hunting, so besides teaching them how to be good Christians, the Jesuits had to coax them to work harder than they were used to working. The Jesuit equivalent of reveille went like this:

“They marshalled their neophytes to the sound of music; and in procession to the fields, with a saint borne high aloft, the community each day at sunrise took its way. Along the paths, at stated intervals, were shrines of saints, and before each of them they prayed, and between each shrine sang hymns. As the procession advanced, it became gradually smaller as groups of Indians dropped off to work the various fields, and finally the priest and acolyte with the musicians returned alone. At midday, before eating, they all united and sang hymns, and then, after their meal and siesta, returned to work until sundown, when the procession again re-formed, and the labourers, singing, returned to their abodes.”(1)

The main tasks of the Guarani were to grow crops, especially yerba mate, and to herd cattle and sheep. Others wove cotton or labored in workshops to produce all kinds of manufactured goods: leather, wood, clothing, rope, boats, carts, books, arms, gunpowder, musical instruments and books. In return for the goods they grew and made, the Indians received rations of food and clothing, and a few manufactured goods like knives, scissors and telescopes. Besides the work days, the natives were also told when to attend church, and when the times for holidays or recreation arrived.

At the peak of the Jesuit mission, between 1650 and 1720, there were more than 60 reductions, which were home to more than 100,000 people. The drawback to it was the paternal attitude of the Jesuits; they treated the natives like children who would never grow up. Most were not given responsibilities or taught to think for themselves, so while their souls were saved, and their standard of living was somewhat better in the reductions, they did not learn the skills needed to be successful elsewhere, especially in cities like Asuncion.

What ended the Jesuit experiment was the jealousy of non-Jesuits, who envied the success the Jesuits enjoyed with their Indian work force. The reductions also attracted slave raiders from Brazil, the bandeirantes, who came looking for Indians to carry off; not only were the priests and Indians nearly defenseless, but other Spaniards in the vicinity did not do much to protect the reductions. Finally, King Charles III did not trust the Jesuits, so a decree from him in 1767 expelled the Jesuits from Spain, and ordered their property confiscated. The men put in charge of the reductions, both clergy and civil administrators, did not know how to manage them. The Indians wandered off, and either went back to their old way of life or became workers on European-owned plantations. Within a few years the reductions were ruins, reclaimed by the Amazonian jungle, along with the surrounding orchards and fields.

Caribbean Contention, Part 1

Spain's rivals grew bolder as the seventeenth century wore on. Before 1654, all the French, Dutch and English could do about Spain was hire privateers to prey on Spanish shipping, or pick off the small islands that Spain had claimed, but never got around to colonizing. When Spain showed more signs of weakness, however, they felt ready to try for greater prizes. At the end of 1654, Oliver Cromwell sent a fleet from England, commanded by Admiral Sir William Penn (father of the William Penn who founded Pennsylvania) and General Robert Venables, with orders to conquer Hispaniola, the most important Spanish-ruled island in the Caribbean. In April 1655 they landed about forty miles west of Santo Domingo, but their two attempts to take the island's capital failed miserably. Venables blamed the failure on the cowardice of his men, got on his ship and sailed to Jamaica, which he and the men managed to conquer in just a week. The Spaniards abandoned their fortifications, Penn gave them an ultimatum, and the Spaniards left Jamaica for Cuba (before they left, though, they freed and armed their slaves, in the hope that the slaves would continue a guerrilla war against the English). Then Penn and Venables returned to England to report their success and defend their actions. But because Jamaica was a poorer island than Hispaniola, it was not considered an acceptable substitute, and both Penn and Venables were briefly imprisoned in the Tower of London for failing to complete their mission. Still, they had inflicted a blow from which Spain never recovered--they had captured one of the Greater Antilles--and the Spanish government ceded both Jamaica and the Cayman Islands to England in 1670.(2)

In the same year that Jamaica was conquered, England gained another foothold in Central America, to go with the one they already had at Belize (see Chapter 2). Details are not clear, but at some point in the 1630s, the Providence Island Company (the same group of Puritans that tried unsuccessfully to found a colony on a small island near Nicaragua), brought the son of a Nicaraguan chief to England, and he requested an alliance. London agreed and the chief's son returned under English protection. That was where matters stood until 1655, when the English declared that the whole eastern coast of Nicaragua and part of Honduras, henceforth known as the Mosquito Coast, would become an English protectorate.(3)

The success with Jamaica and the Mosquito coast encouraged more Englishmen to come to Central America, to harvest hardwood (chiefly mahogany) and dyewood. Besides going to the logging camp already established at Belize, they founded a second one on the other side of Yucatan, at Campeche Bay. Of course the Spaniards were not pleased to have these new neighbors, and they succeeded in getting rid of the Campeche group in 1717. They also drove the English loggers out of Belize four times (1717, 1730, 1754 and 1779), but because they did not settle Belize, the English always came back. The decisive battle came on September 10, 1798; a strong Spanish force tried to wipe out the Belize colony, but the loggers drove them off with the help of their slaves, an armed sloop, and three companies of a British regiment. This battle was named the battle of St. George's Caye, and it is celebrated as a national holiday in modern-day Belize. The Spaniards never bothered Belize again after that, because with their empire now coming undone, they had much bigger concerns to keep them busy elsewhere.

England's next move was a second attempt to colonize the Bahamas. These islands had been a deserted archipelago for more than a century; by 1520, all of the original Indians had died from disease or were relocated to Hispaniola by the Spaniards, to work on their plantations. We also saw in the previous chapter how an early English attempt to set up a colony had failed. The second colonization effort also used settlers from Bermuda, and they set up a home on the island of New Providence in 1666. Whereas the first colonists had been mostly farmers, the second colonists made a living off the sea: salvaging shipwrecks (“wrecking”), and collecting salt, fish, sea turtles, conchs and ambergris. Then in 1670, King Charles II transferred ownership of the islands to the Carolina Company, the same organization that had founded North and South Carolina on the mainland. One year later, the Bahamas received its own governor and parliament, too. But that didn't mean life was getting better. For one thing, the “Lords Proprietor” of the Carolina Company had trouble getting the independent-minded Bahamians to follow their orders. An even bigger problem was piracy; an archipelago with as many islands as the Bahamas provides many hiding places for pirates. The most famous pirates who set up home bases in the Bahamas were Henry Morgan, Edward Teach (Blackbeard), John “Calico Jack” Rockham and his lover Anne Bonny, and a second female pirate, Mary Read.

The pirates encouraged Spain to capture the Bahamas in 1684, but as with Belize, they did not stay, and the English returned to start their colony again. This time they founded Nassau (named after a Dutch territory ruled by King William III) on New Providence Island, and fortified it as the new capital. By 1717 the pirates were making so much trouble that England terminated the Carolina Company's mandate over the islands and appointed a new governor, Woodes Rogers. His chief task as governor was to end piracy, and he did that by pardoning the pirates who accepted his authority and hanging the rest.

Once the Dutch, French and English had enough Caribbean colonies, they went over to sugar production in a big way. We saw the Portuguese growing sugar previously, first on Atlantic islands like Madeira, then in Brazil. The Dutch learned about the sugar industry while they were in Brazil, introduced it to the Caribbean, and provided plantation owners with the two things they needed the most, a supply of black slaves and a guaranteed market for the sugar. The new technology produced a dramatic increase in wealth (sugar plantations made even poor islands in this part of the world worth having), and an even more dramatic demographic change. Before Columbus, the Caribbean population had been Indian; in the sixteenth century, it was predominantly white; in the mid-seventeenth century, blacks became the majority, and have been ever since. Barbados, one of the first islands where sugar plantations succeeded, had an all-white population of 10,000 in 1640; thirty-five years later it had 50,000 people, of whom two-thirds were black.

The huge profits that the Dutch reaped from trading sugar and slaves were fairly earned, because nobody could match the Dutch in efficiency.(4) However, England wasn't any more willing to let the Dutch take money out of their colonies than Spain was, so in 1651 Parliament passed legislation which, like the Spanish laws of the sixteenth century, gave the mother country a monopoly over the colonial traffic. This led to three Anglo-Dutch naval wars between 1652 and 1674. Although the Dutch won their share of battles, ultimately England won the contest. The factor here was the same one that decided Dutch strategy in their struggle against Portugal and Spain--the bottom line. A Dutch warship was really an armed merchantman, so whereas an English man-o-war only had to fight well, a Dutch ship was expected to both fight and bring a profit. Therefore the Dutch chose to cut their losses when they became convinced that winning wasn't worth the cost. By letting the Portuguese recover Brazil, and by giving New Netherland to England (1664), they were able to save their interests in the Caribbean(5), Africa, Asia--and the trade routes between those places and Holland. As for the English, their victories against the Spaniards and the Dutch gave them the resources to build the world's greatest navy. The Royal Navy would be England's most important tool as it turned its attention back to an older rival, namely France.

Speaking of France, it was doing well in the Caribbean, too, though its achievements weren't as impressive as England's. The French launched their own campaign to conquer Hispaniola, and because their base, the islet of Tortuga, was much closer than England's nearest base, they were more successful. French buccaneers (see below) led the way, because Spain had neglected the western part of Hispaniola; Santo Domingo was on the other side of the island. In 1659 the activities of the buccaneers gained official sanction, when King Louis XIV declared Tortuga a French colony. Although piracy was the main source of income for French settlers on western Hispaniola, they also started plantations to grow coffee, tobacco, sugar and indigo. Spanish retaliation got the same results that we saw, when used against the English at Belize; Spain could drive out the French intruders, but the local resources were rich enough to bring them back after the Spaniards went home. Finally, Spain was forced to recognize that France had more control over the western third of Hispaniola than they did; in the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, Spain officially ceded this area to France. The French translated the name “Santo Domingo” into French, and gave that name, St. Domingue, to their prize; for the land that Spain still held, it was now simply called Santo Domingo, after the capital.(6) On the other side of the Caribbean, the French took Tobago from the Dutch in 1677.

Because the Dutch, French and English were so successful there, the Caribbean attracted the attention of nations not known for their New World empires. One such country was Denmark, The Danes set up a Danish West India Company, which went to the Virgin islands and settled Saint Thomas in 1672, Saint John in 1694, and purchased Saint Croix from France in 1733. They did not get all of the Virgin Islands, though, because England took over the Dutch colony already established there in 1672; that became today's British Virgin Islands. In 1754 the Danish outposts were merged into an official royal colony, called the Danish-Westindian Islands. Likewise, Sweden got a temporary outpost in the Caribbean to match its temporary outpost in North America (Delaware). From 1785 to 1878 the Swedes ruled the island of Saint Barthélemy, running it as a free port.

As you can see, sugar production became a big money maker for all the countries that tried it in the New World. Indeed, in the eighteenth century it played the same crucial role in the world economy that spices played in the fifteenth century, or that oil has played in our own time. There was some concern that if one nation gained control over too many Caribbean islands, it would saturate the sugar market, but fortunately that never happened, because world population continued to rise, causing the demand for sugar to rise as well. However, this also meant that the Caribbean was becoming very important to Europe. As the stakes rose, it became more likely that whenever two European nations with Caribbean colonies went to war, they would try to take each other's colonies. And there were many little wars in Europe at this time, which turned into big wars when England and France got involved, because their rivalry always put them on opposite sides. Each war with Caribbean activity saw a larger commitment from each nation, and thus bigger battles. Whereas the War of the Grand Alliance saw just a few naval raids, during the War of the Spanish Succession, the Caribbean was considered important enough to be included in the treaty ending the war, the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), and later on we will see that the next two big wars, the War of the Austrian Succession and the Seven Years War, had more far-reaching results in the Caribbean theater.

The Golden Age of Piracy

Besides the nations mentioned in the previous section, there was a faction that served no nation and was feared by all--the pirates. We have records of pirates in the Mediterranean more than three thousand years ago (the Mycenaean Greeks), and there have probably been pirates ever since somebody discovered that a boat can be a useful tool for a life of crime. Pirates are still active in some waters today (e.g., the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean near Somalia), but when you mention pirates, chances are that whoever hears you will think of the Caribbean around the year 1700. In part this is because Disney built a very successful boat ride at its amusement parks (Pirates of the Caribbean), and a string of movies starring Johnny Depp, around that theme. The other reason is that the Caribbean pirates made a stronger impression on Western culture than other pirates, and in the late seventeenth/early eighteenth century they were the main hazard for those traveling between the Old and New World.

During the colonial era, every European nation with colonies insisted that only it had the right to trade with those colonies. We call this practice mercantilism, and while it was always set up to protect the economy of the mother country, it never worked very well.(7) The main problem was that no country could supply everything the colonists wanted at a fair price, so smuggling quickly became a problem. Attempts to enforce the monopoly made matters worse; the cost of guarding the coast had to be met from customs duties, which increased the price of legal goods and thus increased the demand for illegal goods.

Because the Spanish economy was the largest and the least competitive, Spanish colonies attracted the most smugglers; in the Caribbean, smuggled goods actually exceeded official imports. It was a similar story with Buenos Aires, which had an excellent port, but suffered from the crown's restrictions on trade; here as well, smugglers brought in contraband from Portuguese Brazil and non-Spanish Europe, to meet the needs of the colonists. More police and heavier punishments were the official answer, but as usual repression fought a losing battle with economics. The ships and men available were not strong enough to solve the problem, so the authorities used them viciously when they had them. This taught the smugglers to arm and organize themselves. At first the resident smugglers of the Caribbean only had canoes, but when they captured some real Spanish ships, they turned into the buccaneers, the international “Brethren of the Coast,” with their own captains and admirals.

We saw in Chapter 2 that the first pirates in the New World were French, because in terms of land, ships and money the French could not compete with Spain on an equal footing, so like today's guerrillas and terrorists, they resorted to unconventional warfare. Today the terms “pirate” and “buccaneer” are treated as meaning the same thing, but the technical definition of “buccaneer” means a pirate who belongs to a large group (larger than the crew of one pirate ship), or a pirate who spends all his time prowling the Caribbean (as opposed to those who tried their luck in other places, like the Indian Ocean). The early pirates were also hunters, and they learned from the Arawak Indians to smoke what they caught, so it would last longer and be easier to transport. The Arawak smoked their meat on a wooden frame called a buccan, which the French translated to boucane, and gave the name boucanier to the hunters who used such frames. When the English learned the term, they Anglicized boucanier to buccaneer. Originally manatees were the main item smoked, but because there were now wild cattle and pigs to hunt on Hispaniola, they quickly became the preferred delicacy.(8)

For the second half of the seventeenth century, the buccaneers were the scourge of the Spanish Caribbean. When we saw Caribbean pirates in the previous chapter, they were using Tortuga, the island just north of Hispaniola, as their base, with the consent of the French. After the English took Jamaica in 1655 they moved to Jamaica's capital, Port Royal. England let them in because they gave Port Royal protection against foreign attacks, at a time when England itself did not have enough ships to spare for Jamaica.

While the buccaneers were there, Port Royal gained a reputation as the Caribbean's worst hive of scum and villainy. Outsiders saw it as the Sodom of the New World, a city full of criminals and prostitutes. It was where pirates came for rest and recreation after a successful raid, a place with so much money that drunks gave women extravagant sums of cash just to see them naked. Port Royal's taverns consumed so much liquor that we have reports of wild animals coming there for a drink. Here is how Jan van Riebeeck, the Dutchman who founded Cape Town, described the scene outside the Port Royal taverns:

“The parrots of Port Royal gather to drink from the large stocks of ale with just as much alacrity as the drunks that frequent the taverns that serve it.”

Appropriately, Port Royal got a Biblical punishment for the sins of its inhabitants. On June 7, 1692, a terrible earthquake destroyed the city, and the northern half of it sank into the sea. In the 1960s, divers in the sunken part of Port Royal found a pocket watch that had stopped at 11:43 AM, so we know the time when the earthquake happened, as well as the date. After attempts to rebuild Port Royal failed, the capital of Jamaica was moved to nearby Kingston, where it has been ever since.

It was while England looked the other way that the buccaneers achieved their greatest coups. As an organization, the buccaneers enjoyed their last fling in 1685, when two parties of them crossed Panama to terrorize Spanish America's Pacific coast again. The English buccaneers, a force of 3,000 men led by Edward Davis, John Eaton and Charles Swan, failed to take Panama City, while the French buccaneers, led by Pierre le Picard, looted Guayaquil in Ecuador before returning to the Caribbean.(9) After that, the English, French and Dutch governments stopped issuing letters of marque against Spain. England in particular felt that her colonies were no longer in danger from Spain, but they needed some law and order. The buccaneer brotherhood split into English and French halves, because the only letters of marque still available were for those who wanted to become English privateers against France, or vice versa. Some pirates responded by attacking all ships besides their own; they had short careers, because the governments of the day did not provide vocational rehabilitation to pirates who might want to change jobs. Most of the time, the authorities put the pirates out of business by hunting them down and hanging them (see the fate of Captain Kidd below). The pirate party was over, until our pop culture fell in love with them.

Famous Pirates

The biographies and adventures of the pirates cannot be completely covered in a general narrative such as this; they would need their own website, to tell their stories completely. Here we will mention the best known plunderers, and highlight their outstanding achievements; go ahead and Google their names if you want to learn more about them.

- Henry Morgan (ca. 1635-88). One of the most successful pirates of all, in part because he was never a buccaneer, but did all his raiding against Spanish targets with an English letter of marque, meaning he was a privateer. We don't know anything about his early life; when he first appeared, he was taking part in the 1655 Jamaican expedition. Under Commodore Christopher Mings, he became a privateer and rose through the ranks, commanding his first ship in 1661. The mid-1660s saw him spend two years going after targets in Mesoamerica, from Mexico to Nicaragua, because he discovered a loophole in his contract; he did not have to share the loot with the English government if he acquired it in a land campaign, instead of on the sea. Then he took part in raiding Dutch ships and islands during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Next came the biggest prizes. In 1668 he raided Puerto Principe, Cuba, and then took and sacked Porto Bello, the heavily-fortified Spanish city in Panama. For 1669 he sacked Maracaibo, Venezuela's second largest city, and then in 1671 he topped all previous raids by leading 1,400 men across the Isthmus of Panama to pillage and destroy Panama City. However, England and Spain had just signed a peace treaty, meaning Morgan was now in real trouble. He was arrested and sent to England, where he managed to prove he had no previous knowledge of the treaty. In 1674 King Charles II actually knighted Morgan and appointed him governor of Jamaica, a post he held until 1681.(10) His last years were peaceful ones; more than one story has a pirate retiring with his ill-gotten gains, but Henry Morgan was one of the few who really did it.

- William Kidd (1654-1701). The Scottish-born Captain Kidd is controversial; he was either one of the most notorious pirates ever, or he was an unjustly prosecuted privateer, depending on whose account you're reading. He showed more than anyone else that the line between privateering and straight piracy is a thin one; weak and corrupt governments found it difficult to keep control over the ships that received letters of marque from them, and actions that had the approval of one group were often considered illegal by another.

William Kidd belonged to several ship crews during his early years; we first hear of him in 1689, when he was a member of a French-English pirate crew. A mutiny in this crew ousted the previous captain, and Kidd took his place; his first act was to rename the ship the Blessed William. During the War of the Grand Alliance, Kidd was a privateer against the French, under orders of the colonial governor of New York and Massachusetts. Then in 1695 Kidd sailed to England, to accept an offer to hunt both pirates and French ships in the Red Sea; this proved to be a fatal error.

In England Kidd was given the Adventure Galley, a ship superbly suited for the task of catching pirate ships; it had oars as well as sails, so it could keep moving when the wind was calm. But that was the end of his good luck. First Kidd headed for New York to recruit more crewmen, then into the South Atlantic on the way to the Red Sea. Suddenly the thick fog of the mid-ocean cleared and he found himself surrounded by a squadron of Royal Navy ships. These ships badly needed new sailors to replace those lost to scurvy, and English law said they could take up to half the men from any English ship, to serve on their own. Captain Kidd could not continue his own voyage if he lost that many men, so using the Adventure Galley's oars, he sneaked away on a windless night. The navy captains decided he did this because he was up to no good, and spread the rumor that he had become a real pirate.

By the time he got to Africa, Kidd was also dealing with scurvy, a rotting ship, and a shortage of food and water. He couldn't land in South Africa, because that was where the Royal Navy squadron was headed, so he went to Madagascar, which like Jamaica was a pirate's haven. From there he went on to the Red Sea, then to the coast of India, without catching much. By this time he and the crew no longer cared if they were operating legally; all they wanted was enough provisions to keep them going, and enough treasure to make the voyage a success.

They thought they hit paydirt when they captured the Quedah Merchant, an Indian ship with an Armenian crew, in 1698. This was the biggest catch of Kidd's career; not only did it have a rich cargo worth £7,000, the ship was a good replacement for the Adventure Galley. Kidd kept it and renamed it the Adventure Prize. Unfortunately for him, the ship had been on a merchant run supported by backers from more than one nation, which included the Mogul emperor Aurangzeb and the English East India Company. The Quedah Merchant's owner demanded restitution from the company, meaning that Kidd had now become the enemy of English businessmen.

Sailing back to Madagascar first, then returning to the Atlantic, Kidd did not realize he had crossed the line between privateering and piracy until he arrived in the Caribbean with the Adventure Prize. When he learned he was a wanted man, he decided to rush to New York, where he had friends powerful enough to protect him. But he could not show up with incriminating evidence, so first he burned the Adventure Prize at Hispaniola,(11) and sold the rest of the cargo. The gold he got from that sale was easier to transport than all the chests and bags that made up a ship's cargo, but Kidd still feared it would fall into the wrong hands, so while he was in the North American colonies, negotiating a pardon, he went and buried the gold, either on Long Island or along the Connecticut River, thereby starting the buried treasure business. Though he succeeded in hiding the loot, he was suddenly arrested in July 1699, and thrown in jail in Boston. A year later he was sent to England, where he became a political pawn, but there he still refused to name his patrons, confident they would come to the rescue. Instead he was put on trial, convicted of murder and piracy, and subsequently hanged. Afterward his body was tarred and left swinging in a cage for three years, as a warning to other would-be pirates.

- Benjamin Hornigold (?-1719). You probably haven't heard of this pirate; he belongs on the list because he was Blackbeard's mentor. Definitely not your “shiver-me-timbers” run-of-the-mill pirate, he had a reputation for being a gentleman, and was only in the business for four years, from 1713 to 1717. Apparently the end of the War of the Spanish Succession forced him to turn to piracy, when he could not find another way to earn a living. Even so, he refused to attack English ships, giving the illusion that he was a privateer for England. His greatest feat was the capture of a thirty-gun sloop, the most heavily armed ship in the Caribbean; he renamed it the Ranger and made Blackbeard the captain of his older, smaller ship. After this, attacking merchant ships was so easy that he seemed think it was just a game. Once he chased a merchant ship, caught up with it, and told the crew that he only wanted their hats, because his pirates got drunk the night before and threw their own hats overboard. Once he had the hats, he let the merchants go, with their ship, cargo and purses intact. Another captured crew reported that Hornigold let them go as well, after taking "only some rum, a little sugar, powder and shott." Naturally the crew didn't like this behavior, because it wasn't making them rich, so they voted to depose Hornigold and replace him with his lieutenant Blackbeard. After that, Hornigold decided to take the amnesty offered by Woodes Rogers, the governor of the Bahamas (see above). Rogers accepted, on condition that Hornigold become a pirate hunter, and go chasing his former allies and partners. Hornigold did, and eighteen months later a hurricane wrecked his ship on an uncharted reef, drowning everyone aboard.

- Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard (ca. 1680-1718). The most notorious pirate of all, because he used psychological warfare to make his reputation even more fearsome; among other things, he is reported to have tied bits of hemp rope in his beard and lit them just before battle, to frighten his enemies. We saw above that his career got started when Benjamin Hornigold recruited him. Right after he succeeded Hornigold as leader of the pirate fleet, Blackbeard captured a large French slave ship, the Concorde, which he renamed the Queen Anne's Revenge. Then he headed to the North American mainland, where he blockaded Charleston, South Carolina for a while, looting nine ships that tried to go in or out of Charleston's harbor. After that he managed to get a pardon from the governor of North Carolina, but soon returned to piracy, this time using Ocracoke Inlet, NC as his favorite anchorage. His presence alarmed the North American colonies as far north as Pennsylvania, and the governor of Virginia sent Lieutenant Robert Maynard, captain of the HMS Pearl, to get Blackbeard. When the showdown took place at Ocracoke, Blackbeard reportedly was shot five times and suffered twenty sword cuts before he died; then Maynard cut off Blackbeard's head, pushed the body overboard, and hung the head on the bow of his ship, so he could claim the reward.

The battle between Blackbeard and Lt. Maynard.

Blackbeard has been dead for three centuries, but he can still make news. In 2005 the wreck of the Queen Anne's Revenge was found off the North Carolina coast; divers have recovered some 16,000 artifacts from it so far. And what happened to his head after Lt. Maynard got home? It was mounted on a pole at Hampton, Virginia, between the heads of two other recently killed pirates, again as a warning. After that, when only the skull was left, somebody gave it the same treatment reserved for the victims of Eurasian barbarians--it was coated with silver and converted into a drinking cup. Just the thing for spooky frat parties! The skull/punchbowl was last reported in a New England museum in 2007, though it isn't clear how it got there.

- John “Calico Jack” Rackham (1682-1720). This pirate got his nickname from the underwear he wore most of the time. When we first see him, he is the quartermaster for an English warship. One day in 1718, this ship encountered a French warship. The captain, Charles Vane, refused to fight the larger French ship, while Rakham argued that they should try to take the ship, because it must be full of riches, and having that ship would make them stronger. Shortly after they fled the French ship, the crew, led by Rackham, voted to remove Vane from command and have Rackham take his place. Then he encouraged the crew to become pirates. His new career was short-lived, though; after just two years of raids, Rackham and his crew were captured, taken to Jamaica, tried and hanged. Calico Jack is mainly known today for his version of the Jolly Roger (a skull above two crossed cutlasses), and for introducing us to the two most famous female pirates, Anne Bonny and Mary Read.

- Anne Bonny (1702?-1782?) and Mary Read (1690?-1721). Anne Bonny was born in Ireland, under the name Anne Cormac, the illegitimate daughter of a successful lawyer. When word got out about her father having a child out of wedlock, it ruined his reputation, so he, his wife and Anne moved to Charleston, South Carolina to start over. Being the independent-minded type, Anne married James Bonny, a small-time sailor and pirate, when she was sixteen, against her father's wishes. Mr. Bonny wanted to become heir to his father-in-law's estate, but Anne's father disowned her instead, so James and Anne went to the Bahamas to try their luck there. While in Nassau, Anne met John “Calico Jack” Rackham, and when James became an informer to the governor, Woodes Rogers, Anne left him to become Calico Jack's mistress.

For the next few months Anne traveled as a member of Calico Jack's crew, except for a brief period when Anne was pregnant and Calico Jack left her on Cuba to deliver their baby (we don't know if the baby died at birth, or was given up for adoption). Along the way they recruited Mary Read as a new crew member, because she was disguised as a man at the time.

Mary Read was the illegitimate daughter of a ship captain who sailed away and never came back. She had an older, legitimate brother who died young, and her mother started dressing her up as a boy, so that her grandmother would continue to give them financial support. The grandmother was fooled so well that Mary wore male clothing until she grew up, and ended up doing it for most of her life. Thus, she even did terms of military service for England and Holland, during the War of the Spanish Succession. On the pirate ship, the disguise lasted until Anne Bonny took an interest in what she thought was a handsome young crewman. After revealing that she wasn't a man, she and Bonny remained close friends; some believe they even had a lesbian affair. When Calico Jack found out, he decided to break tradition and let Read remain a member of the crew.

When a pirate hunter captured Calico Jack's ship, most of the crew was too drunk to fight; the only ones who did were the two women and an unnamed crewman. Before his execution, Bonny visited Rackham in prison, and told him that she was "sorry to see him there, but if he had fought like a Man, he need not have been hang'd like a Dog." Soon after that, Bonny and Read were put on trial; both claimed to be pregnant, and escaped the hangman by “pleading their bellies” (it was against the law to execute an unborn child). Read died around her delivery time, either from childbirth or from a fever contracted immediately afterwards. Bonny disappears from the records at this point, so we don't know what her fate was. The most popular theory is that her father showed up on the scene, used his connections to secure her release, and then took her back to South Carolina, where she lived quietly and respectfully for the next sixty years.

- Bartholomew Roberts (1682-1723). Also called “Black Bart”; don't confuse him with the other Black Bart, who was an outlaw in the American West. Over the course of his four-year career he captured around 470 ships, more than any other pirate. The son of a well-to-do Welsh family, Roberts was working on a slave ship that happened to be captured off the coast of Africa by two pirate ships, commanded by Howell Davis. When the pirates “invited” several crew members to join them, Roberts accepted, because he was making less than £3 a month at his job on the slave ship, and because he probably would have been killed if he refused. Davis took an immediate liking to him because he was a skilled navigator, and because both of them were Welsh, meaning they could converse in the Welsh language without anyone else in the crew understanding them. Soon after that, Davis was killed while attacking the Portuguese island of Principe, and the pirates elected Roberts as their new captain; though he had been with them for only six weeks. Previously he had made it clear that he didn't like being a pirate, so when he accepted the promotion, he said it was "Better being a commander than a common man." Then he led the men back to Principe, plundered the island, and killed much of its male population.

After that Roberts felt that the pirate's life was for him, but he acted more civilized than most people in his position. He imposed on his own crew an eleven-rule code of conduct, which stated things like how much of the loot each crewman could have, no gambling for money, lights out at 8 PM, everyone must keep his weapons clean, no women or boys aboard, and so forth; he even had them swear on a Bible to uphold these rules. If a ship worth taking came into view on a Sunday, it was likely to get away, too, because Bart refused to fight on Sunday, for religious reasons. And when he captured a ship, before taking anything from it he would ask the defeated crew if they had been well treated by the captain and officers; if they said no, he would chop up whomever they did not like, as they cheered.

Roberts did not concentrate his efforts in one area, but traveled all around the Atlantic, to Brazil, the Lesser Antilles, Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. His first attacks against Barbados and Martinique caused him to lose many men, making him so mad that when he returned to Martinique, after he was finished with Canada, he captured that island's governor and hanged him from a yardarm. Next he went to West Africa again, and on February 10, 1722, he was killed by a round of grapeshot fired by an English warship he was fighting with. Roberts had told his crew previously that he wanted to be buried at sea, so they quickly put weights on his body and dumped it overboard. The rest of the battle was a total rout; 272 pirates were captured. 75 of those men were black, so they were sold into slavery, and 52 of the rest were subsequently hanged. That persuaded a lot of men to not become pirates, so some historian declare that the age of piracy ended with Black Bart's death.

- Jean LaFitte (1776?-1823), lived more than a century after the other pirates on this list; we are including him here because of the role he played in US history. He detested being called a pirate, and always insisted he was a privateer, though he did not have a letter of marque from anywhere but the Colombian city of Cartagena.(12) A great admirer of the young United States, he never attacked an American ship, and felt that the Americans did not appreciate him enough. Lafitte did his share of raiding, in the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean and the Atlantic, but his main interest was the Mississippi delta, because the people living there were largely French, like himself.

In the first decade of the nineteenth century, LaFitte and his two brothers managed a smuggling operation, running tariff-free goods to New Orleans. This was especially profitable after US President Jefferson tried to influence the Napoleonic Wars with the Embargo Act. The people of New Orleans admired Lafitte because this was only a few years after the Louisiana Purchase, so there were no roads and few boats to connect Louisiana with the rest of the nation; to them Lafitte was like Wal-Mart, bringing them merchandise that was otherwise unavailable, at prices they could afford. By 1813, the LaFitte brothers were doing so much illicit business that Louisiana Governor Claiborne ordered the pirates to abandon their base on the island of Grand Terre, and then offered a reward of $300 for Jean LaFitte, dead or alive. The freebooter wasn't too scared, because he had more ships on his side than Claiborne did, and responded with an offer of $1,000 for the governor! A year later, the US Navy made its way to Grand Terre and scattered LaFitte's men. By this time the War of 1812 was in full swing, and the British sent this offer to LaFitte: if he would join them in their invasion of the southern United States, they would give him the rank of captain, command of a frigate, and £30,000. LaFitte asked for fifteen days to think about it, and wrote a letter to Governor Claiborne, offering to put his men and ships in the service of the Americans, if the United States would stop harassing him. Claiborne agreed, so LaFitte fought on the side of the Americans at the battle of New Orleans. The western United States might not exist today if LaFitte hadn't done his part to keep the British from winning that battle, and the American general on the scene, Andrew Jackson, knew it; this prompted President Madison to grant a general pardon to the freebooters a month later.

After the war LaFitte moved to Texas; he figured he would be safer in Spanish territory, and soon had the same kind of island base at Galveston that he had on Grand Terre. Instead of American meddling, here he faced attacks from the local Indians, the Karankawas, and a nasty hurricane. Eventually he abandoned Galveston, and spent his last years raiding Spanish shipping, until he was killed in a battle off Omoa, Honduras, by two ships that he thought were Spanish merchant vessels, but were really heavily armed Spanish privateers.

- First, the buried treasure scene that is so common in pirate stories. A pirate captain was more likely to share the loot with his crew than he was to hoard and bury it.(13) After all, the crewmen were in the pirating business for the money, and the captain did not have absolute control; pirate crews were governed by a crude democracy, which could vote to replace a captain if he did not fight or deliver as expected. And someone else could find the treasure, if it was buried and left unattended. The only real-life pirates reported to have buried treasure were Sir Francis Drake, Roche Brasiliano, and William Kidd. Moreover, none of them drew treasure maps to keep track of where they buried the chests. Because Captain Kidd did not come back to get his booty, many treasure hunts have taken place over the past three centuries, but nobody found anything, so we can't even be sure if Kidd's treasure existed.

- Pirates stole more than just gold, silver and gems. A ship with a cargo of food, candles, soap, gunpowder or tools was welcome, too. Because pirates spent most of their time on the high seas, they took whatever they could get to keep themselves from starving, or to keep their ships afloat. Consequently any ship headed for the colonies with a cargo was likely to have something pirates could use.

However, you have to feel sorry for Basil Hood, because of his choice of loot. In 1713 this pirate captain and his crew went ashore, stole a herd of cattle, and put them in their ship's cargo hold. They must have thought it was an easy raid. What they didn't know was that cows get seasick easily, and when that happens, they become what has been described as a "volcano of vomit." The puking cows made such a foul-smelling mess that when an English warship showed up, Hood surrendered, but once the English captain got a look (and a whiff) of what the pirate ship was carrying, he actually let them go!

- The parrot on a pirate captain's shoulder. That apparently started with a fictional pirate, Long John Silver. A parrot would be an appropriate pet for a pirate to have (quite a few sailors had them), but we have no record of any of the more famous pirates owning one. On the other hand, we know that Blackbeard had a howler monkey named Jefferson.

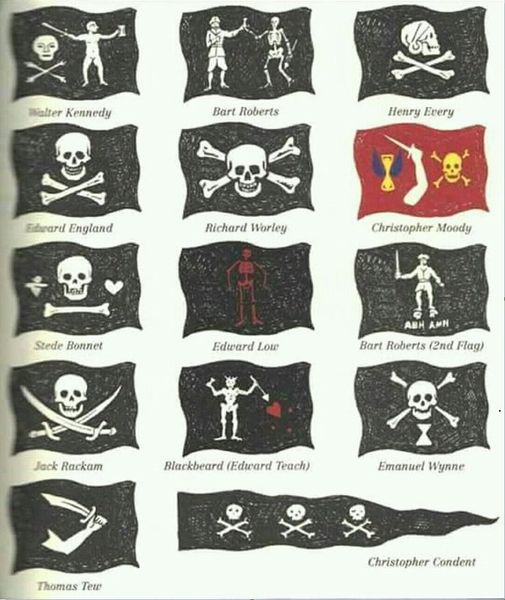

- The “Jolly Roger,” the flag associated with pirates, was real, but it did not have to follow the skull-and-crossbones design that we think of today; it did not even have to be a black flag. Every pirate crew or buccaneer fleet had their own flag, and the only common feature about them was that they included a symbol of death. Bartholomew Roberts (“Black Bart”), for example, flew a black flag that featured himself and a skeleton holding an hourglass.

An assortment of pirate flags, with the names of the captains who flew them.

- Pirate ships were not wooden dreadnoughts that overpowered their opponents with brute force. That may be how they look in the movies, but in real life most were one or two-masted sloops. This meant they were smaller than navy vessels, so when a typical pirate ship encountered a “man-o-war,” the first response would be to sail away quickly, or hide in a cove that larger ships couldn't enter. Benjamin Hornigold's big ship was the exception to the rule.

- Arrh, the language, ye mateys! I happen to be writing this on “Talk Like A Pirate Day,” (September 19), so this stereotype needs to be addressed, too. A lot of so-called pirate lingo is an exaggeration of the western English country accent, plus the imagination of writers like Robert Louis Stevenson. In truth, sailors from the Cornwall area could talk that way, too, and there is no reason why pirates always had to sound like they flunked English class (especially if they weren't English to begin with). William Dampier (1651-1715), for instance, was just the opposite of a stereotypical pirate; he was also a scientist, explorer, and best-selling author. Instead of speaking a warped version of the English language, he actually expanded its vocabulary; from his writings we learned how to spell hundreds of words that were new in his day, like “barbecue,” “avocado,” and “chopsticks.” In 1697 he wrote a book about his adventures, and it even gave some ideas to Jonathan Swift when he wrote Gulliver's Travels--now that's impressive.

- The peg-legs and hooks for hands are realistic, alas. Medicine on pirate ships was primitive, so amputations were the most common cure for serious wounds. The heavy drinking was necessary, too, because it was hard to keep water supplies fresh.

- On the other hand, the eyepatches weren't always there to cover the loss of an eye. It now turns out that some pirates with two good eyes would wear an eyepatch when they expected to go into a dark place, like the unlit cargo hold of a ship. The idea is that when they entered darkness, they would switch the eyepatch around so that it now covered the eye that had been exposed to bright light, and then they would use the eye that had been covered previously. It meant a loss of depth perception, but the pirate didn't have to wait around several minutes until his vision got adjusted to the dark, which was obviously helpful in a fight. The idea of using an eyepatch to preserve night vision passed a test on a 2007 episode of the TV show MythBusters.

- Hollywood has made old-school pirates look fun, even comical, so never forget that they were bloodthirsty killers, like the Somali pirates of today. The name I gave the previous section, “The Golden Age of Piracy,” would not have been used by anyone back then. If you had lived around 1700, you wouldn't want to meet pirates any more than you would want to meet a group of Al Qaeda terrorists. Some of their real-life careers were so bloody, that I don't expect Hollywood will ever make movies out of them. One of the worst examples was a French pirate named Francois l'Olonnais (1635-68), who actually ate a human heart to prove a point. A year or two after he became a buccaneer, l'Olonnais was in a raiding party that got into a battle with the Spaniards at the Bay of Campeche; he escaped by covering himself with the blood of his comrades, and playing dead. For the rest of his life, l'Olonnais hated Spain bitterly; once he beheaded the entire crew of a Spanish ship except for one man, and sent him away with this message: "I shall never henceforward give quarter to any Spaniard whatsoever." Later on, while raiding the coast of Venezuela, he was ambushed by Spanish soldiers again. Again he barely got away, and took two Spanish hostages as he withdrew. He didn't have enough men to fight, if he met any more soldiers, so he demanded directions to escape from the neighborhood. Alexandre Exquemelin, a seventeenth-century historian, tells us what he did to show he meant business: “He drew his cutlass, and with it cut open the breast of one of those poor Spanish, and pulling out his heart with his sacrilegious hands, began to bite and gnaw it with his teeth, like a ravenous wolf, saying to the rest: I will serve you all alike, if you show me not another way.” The directions given by the horrified surviving hostage got him safely back to his ship, but then l'Olonnais and his surviving crew ran aground in the Darien region of Panama (see below). The reader will probably see justice in what happened next; when l'Olonnais went hunting for food in the Panama jungle, he was captured by Cuna Indians, killed and eaten.

The Darien Scheme and the South Sea Bubble

In the 1690s, Scotland made its only colonial venture in Latin America, and while it did not affect the New World, it changed the course of history for the mother country. Through an act by the Scottish parliament, the Company of Scotland was established in 1695, and it was given extraordinary privileges. For thirty years the Company would have a monopoly on all trade between Scotland and the world beyond Europe; it was authorized to establish colonies where no European colonies existed already; Company ships would not have to pay any customs duties for twenty-one years. The Company's directors decided to raise a sum of £400,000 for their plans, and by appealing to the patriotism of the Scots, they did it in six months. The money came not only from the rich and famous, but also from very ordinary people in all walks of life; we estimate that nearly 1,500 Scots contributed. In today's world, £400,000 does not sound like much to a government or major corporation, but it was one fifth of all the money circulating in Scotland at the time. Keep in mind that Scotland was a poor country, the amount raised was 2.5 times the estimated value of Scotland's annual exports, and the Bank of Scotland (also founded in 1695) was doing its own fundraising at the same time. By the standards of the 1690s, Bernie Madoff would have been a piker, compared with the Company!

So what would they do with the money? The first plan was to build outposts in Africa and Asia, the way other European nations had done, and thereby get a share of the lucrative trade in gold, slaves, ivory and spices. However, one of the Company's directors, William Paterson, had a different plan. He persuasively argued that if the Company wanted to go to Asia, the best way to do it was to go west, like Columbus did. Of course they would have to cross the Americas at some point, so Paterson told them to build a colony in the Isthmus of Panama, where the overland crossing between the Atlantic and Pacific was only a few dozen miles. According to this reasoning, whoever had a colony in Panama would control the richest east-west trade route in the world.

Only the Scots thought this was a good idea. The part of Panama where they planned to build the colony was the Darien Gap. This is a patch of jungle and swamp so thick that no civilization has ever tamed it. In fact, today it is considered the most dangerous jungle in the world. To give one example of how bad it is, the world's longest road, the Pan-American Highway, runs across the Americas, from Alaska to Buenos Aires, but the part that is supposed to go through the Darien Gap has never been completed. Even worse, the colony's location put it close to two critical Spanish ports, Porto Bello and Cartagena. We saw in the previous chapter that Peru's silver was sent to Porto Bello before it was shipped to Spain; likewise, Cartagena was the shipping point for the gold and emeralds of Colombia. Whoever built a colony in that neighborhood was sure to make an enemy of Spain, and no other European power wanted to do that, while the succession to the throne of Spain was up in the air. England's King William III was upset most of all, and he ordered all English colonies in the New World to give no support to the Scots.

Scotland went ahead with the “Darien Scheme” anyway. Paterson paid less attention to the reaction of other Europeans, and more attention to the fact that Spain wasn't as strong as it used to be (remember the buccaneer raids on Panama, just a few years earlier). In 1698 the Company of Scotland sent its first expedition across the Atlantic, bringing 1,200 colonists to a part of eastern Panama they would call “Caledonia Bay.” They built a settlement named New Edinburgh and a fort named Fort St. Andrew. However, the colony only lasted for seven months. They ran out of food quickly, and the Scots hadn't taken the jungle climate into account; Spain had a warmer climate than Scotland to begin with, so naturally the Spaniards did not suffer as much as the Scots in a place like this. A disease epidemic killed more than 300 colonists, including Paterson's wife, and their bodies were buried in mass graves. Paterson himself was so sick from the fever that he had to be carried onto the ship, when the decision was made to abandon the colony. After further loss of life, one of their four ships made it back to Scotland.

Unfortunately, that ship did not come back with the bad news before the second expedition left, with another thousand colonists (June 1699). It arrived to find a deserted settlement at Caledonia Bay. Despite this, the settlers decided to try their luck. They were encouraged when they defeated the nearest Spanish army unit in early 1700, but that only made the Spaniards angry, and one week later they sent a much larger force. Against this, the Scots were hopelessly outnumbered, and they surrendered after a two-week siege.

The Darien Scheme had been a colossal failure. The money spent gained nothing in return, ten of the thirteen ships committed had been lost, and a lot of lives had been wasted; many of the casualties had starved before they could return to Europe, thanks to King William's decree. Because of the fiasco, and a major fire in Edinburgh in February 1700, the Presbyterian Church suggested that God was mad at Scotland, and called for days of prayer and fasting. Indeed, one of the reasons why Scotland accepted the 1707 Act of Union, which merged England and Scotland to form the United Kingdom, was because the treaty called for compensating the Darien investors with an “equivalent” of nearly £400,000, plus 5 percent interest over a nine year period to cover the rest. Moreover, the Scots realized that their nation could not go it alone, nor could they count on England's support, though a Scottish king had ruled England as recently as 1688. Henceforth, in this narrative we will not be referring to the citizens of Great Britain as English, Scots or Welsh, but as British, or simply Brits.

Meanwhile, the European wars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries taught the British that it was safer to take colonies overseas, especially small islands, than it was to occupy a territory on the Continent. Limiting their landholdings on the European mainland meant they could sit out the frequent conflicts there, if they chose to do so.(14) Overseas colonies could also be more profitable, if defended and managed right. Accordingly, in the Treaty of Utrecht, one of the things the British asked for, and got, was the French half of the island of St. Kitts. They also won the right to sell up to 4,800 slaves and 500 tons of cargo per year in the Spanish colonies, something they probably considered more important than the land they gained.

The British wanted trading rights because wars are expensive, and they had run up some big debts during the War of the Spanish Succession. By 1711 the national debt was estimated at £9 million; the government staged lotteries and sold tickets to citizens looking for a chance to win prizes, but this only raised a fraction of the money needed to pay down the debt. Then the idea came up of floating a company that would assume at least part of the debt. In return this company, called the South Sea Company, would be given the right to trade in Latin America and the Caribbean, once the Spanish colonies opened up to non-Spanish merchants. The government would also give the company an annual annuity, worth 6 percent of the debt it took on, and this annuity was distributed to the shareholders as a dividend. We don't know who thought of the South Sea Company first; some historians think it was Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe; others think it was William Paterson, the same fellow who gave us the Darien Scheme. If it was Paterson, this shows us that Great Britain did not learn anything from Scotland's experience in Panama.

The trade rights granted by the Treaty of Utrecht were much less than what the South Sea Company had expected, meaning its ability to make a profit legally would be limited. Nevertheless, many saw great potential in Latin America, and persuaded themselves that the company was another Dutch West India Company; once Latin American colonists tried British-made products, the profits would pour in. When the company issued its first shares of stock, investors bought them eagerly. The first voyage by a company ship in 1717 only brought a moderate return, but then King George I became governor of the company in the following year, boosting investor confidence again. By 1720 the company was doing so well that it offered to take over the entire national debt, and Parliament accepted the proposal.

What Parliament did not realize was that the company was experiencing its first cash flow problem; it did not have enough money to pay the Christmas 1719 dividend, and it informed shareholders that payment would be delayed twelve months. Since it would take too long to get the money by expanding trade, Company executives tried bidding up the value of their stock. In January 1720, company shares were trading at £128, and the price had not changed much for a while. Back then one pound (£1) was worth about $400 in today's dollars, so if you do the math, you will see why the stock wasn't selling very fast.

When the company executives told wild stories about the wealth of the lands beyond the "South Sea," how Latin America was loaded with gold and silver that the company would eventually bring to Europe, this caused a buying frenzy, now called the South Sea Bubble, that drove up the value of the stock, to £175 in February, £330 in March, £550 at the end of May, and at its peak in August, around £1,000 a share. Politicians were offered a chance to buy shares at pre-bubble prices, allowing them to make a profit when they sold the shares later. The big bubble also led to the appearance of little bubbles, as swindlers went to investors who missed out on the company stock and offered them absurd get-rich-quick schemes that were limited only by imagination. The proposals put forth by these "companies" ranged from making better soap, to importing walnut trees from Virginia, to a cannon that fired square cannonballs. Probably the cleverest and craziest proposal got investors to put down money "for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage; but nobody to know what it is."

At that point the bubble burst. When those running the South Sea Company realized that their personal shares were worth many times as much as the company itself, they sold their stock, hoping that if they kept this move secret, the company would continue to do all right without them. Instead, word of them cutting and running got out, a panic selling replaced the frenzied buying, and share prices instantly collapsed; prices fell to £175 by the end of September, and £124 by December. Those who got in after the bubble started swelling were financially ruined, especially those who had borrowed money to purchase shares. Among the losers was the great scientist Sir Isaac Newton, who lost £20,000 (worth probably $8 million today) and remarked, "I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men." Well, what goes up must come down, and Newton, of all people, should have known that!

The House of Commons conducted an investigation in 1721, which found plenty of deceit and corruption; at least three government ministers had taken bribes from the company. The prosecution of those officials and the company managers followed. The South Sea Company stayed in business until 1853, but its stock was given to two real moneymakers, the Bank of England and the British East India Company, and it sold most of its rights to the Spanish government in 1750. Finally, the British government outlawed the issuing of stock certificates, and that law stayed on the books until 1825.

Caribbean Contention, Part 2

The War of the Austrian Succession was preceded by a small war between Britain and Spain, the War of Jenkins' Ear (click here for the footnote on where this strange name came from). Here the British didn't do as well, because they had neglected their navy in the twenty-six years since the previous war ended. Their main success in this war was the battle of Porto Bello; using six ships, the British vice admiral Edward Vernon took the Panamanian silver port in 1739, and held it for three weeks. However, the next two naval assaults failed badly, against St. Augustine in Florida (1740) and Cartagena in Colombia (1741). Those were led respectively by James Oglethorpe (the founder of the colony of Georgia) and Admiral Vernon. The fleet that went after Cartagena was one of the largest Britain ever sent anywhere: 186 ships and 23,600 men.(15) Against this, Spain had no more than 3,000 men defending the port, but a lack of leadership and a lack of provisions among the British quickly turned the siege in Spain's favor. Over the course of a two-month siege, fifty British ships were sunk, damaged or abandoned, and 18,000 men died, mostly because of yellow fever. Meanwhile, Britain sent six ships under Commodore George Anson around Cape Horn, to raid South America's Pacific coast. The loot gained here was small, because the squadron missed the real prize they were after: Spain's treasure ship from the Philippines, the Manila Galleon. However, they managed to cross the Pacific, take on some badly needed repairs in Canton, and catch the Manila Galleon the next year (1743). After that Anson returned to England by continuing to sail west, circumnavigating the globe in the process. Although Anson's expedition lost more than nine tenths of its men to disease, London considered the mission a success, because the captured Manila Galleon had a cargo worth millions.

In 1740 the War of the Austrian Succession broke out in Europe, and the War of Jenkins' Ear turned into the New World theater of that Old World conflict. Spain staged an unsuccessful invasion of Georgia in 1742, in retaliation for the British attack on Florida. Otherwise the conflict in the Caribbean died down, because France had replaced Spain as Britain's main opponent. After Anson's expedition, the only activity in the Caribbean was a few naval battles between Britain and Spain, off the coast of Cuba, in 1748; both sides were so exhausted at this point that the war ended in the same year. Because Britain had done so much worse than expected, the treaty ending the war had a strange feature: the French islands of Dominica, St. Vincent and Tobago, and the British island of St. Lucia, were declared neutral territories. The official reason given for this was that all four islands still had colonies of Carib Indians, who had not gotten involved in the war. Although this was true, nobody would have expected such a response, had either side won a clear victory. Readers of the North American history series on this website will remember that treaties between the Indians and white men were never kept, and in this case, the neutral status of the islands and the Caribs only lasted until the next war.

Despite their setback in the War of the Austrian Succession, the ultimate winner in the colonial contests was Great Britain. As early as 1700, the British colonies in North America were doing great, and Britain's outposts in India and the Caribbean were also prospering. In terms of tonnage shipped and profits made, the Dutch were still in the lead, but before the eighteenth century was half over, British shipping would catch up and pass that of the Netherlands. Although the French claimed more land overseas than the British or Dutch at this stage, in other ways they were in third place; French colonies were underpopulated and unprofitable, and the French trading network had been disrupted by Europe's wars. As for Spain, back in Chapter 2 it was in the lead, but because the Spaniards managed their colonies even less efficiently than the French, they had fallen to fourth place. The other Iberian power, Portugal, brought up the rear. The Portuguese kept Goa, their base in India, by reaching an agreement with England before the Dutch could take it, and cooperation with Spain allowed them to keep Macao, because both countries wanted to trade with China; Canton was the only Chinese port open to them, and Macao was the nearest European base to Canton. On the other hand, in the late seventeenth century Portugal lost half of its ports in the Arabian Sea (mostly on the coast of modern Kenya and Tanzania) to the sultan of Muscat (modern Oman), the ruler of a nation other Europeans did not even notice.

The Settlement of Mexico's Northern Frontier

Meanwhile, French explorers and traders were getting closer to Mexico. The French explorer Robert de La Salle, who sailed down the Mississippi and claimed all land drained by that river for France, even made an unsuccessful attempt to start a French colony in Texas, at Matagorda Island. Because of this, the Spaniards made another effort to incorporate Texas into their empire. This time they were successful. A series of permanent outposts (mostly missions) were established in 1716-17, and though these settlements remained small, their combined population was large enough for Spain to turn the territory into a full-fledged province, in 1728. Then during the next twenty years, Spain settled the part of the Gulf coast just south of the Rio Grande, a sector which had been neglected previously; that became the province of New Santander (modern Tamaulipas) in 1747. Finally, they detached Mexico's barren northwest coast from the province of New Vizcaya, and made it the province of Sinaloa. Sinaloa (which included modern Sonora at this point) had been settled gradually from the south over the past century. The agents of civilization in Sinaloa were the Jesuits, who had worked there since 1591 to convert the Yaqui, a friendly Indian tribe, enjoying a success comparable to what they had achieved in Paraguay. From the northern edge of Sinaloa, the next step was to convert and civilize the Indians of California; that would be done by Franciscan and Dominican missionaries after 1750.

The Seven Years War and the American Revolution In Latin America

The Seven Years War was a world war that took place more than a century before the world wars you have heard of (you may want to call it World War 0). It saw fighting in three major theaters--Europe, North America, and India. On one side was Great Britain, Prussia, four smaller German states, and Portugal; on the other side was Austria, France, Russia, Spain, Sweden, the German state of Saxony, and the East Indian state of Bengal.(16) To the modern reader it is not a surprise that Britain and Prussia won, because Britain had the best navy and more money than anyone else, while Prussia had the best army. Back then it wasn't a foregone conclusion, though, because the enemies of Britain and Prussia had far more land, men and resources, even if they couldn't use them as efficiently.

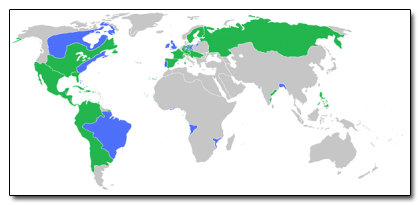

How the match-up looked on a world map: Britain and allies (blue) vs. France and allies (green).

In fact, understanding the Seven Years War is a bit of a challenge, because it was really two wars happening at the same time. In Europe (1756-63) the war was a grudge match between two heads of state who couldn't get along, Austria's Maria Theresa vs. Prussia's Frederick the Great. Outside Europe the war was the latest round in the rivalry between France and Britain (1754-63), and there a young Virginian named George Washington fired the first shot. The outcomes of the two wars were different, too. In Europe it was a matter of Frederick defending Prussia until the Russians switched sides (in the nick of time); in India and North America the British overcame an early French advantage to win one of their greatest victories ever. Though neither Britain nor France had any interests in Latin America, two battles took place there anyway, so this section will cover them.

The first battle took place while Spain was still neutral. In November 1757 fifteen French ships sailed out of the port of Toulon; their mission was to reinforce Louisbourg, the main French fort in Canada. The fleet slipped past the British blockade of the Mediterranean at Gibraltar, ran into a fierce storm in the Atlantic, and took shelter in the port of Cartagena. They were still there when a British fleet, also with fifteen ships, arrived in February 1758. Then two more French ships arrived and got past the British to reinforce the French fleet; the British commander, Henry Osborn, wasn't paying attention because he heard that three French ships-of-the-line, some of the largest fighting ships of the day, were coming as well. Sure enough, when those French ships showed up, Osborn sent his four best ships to engage them, and used the rest to keep the French fleet bottled up in Cartagena. The battle which followed showed that the Royal Navy had gotten its touch back; the British lost no ships, two of the French ships were captured, and the third was run aground to keep it from being captured. After that victory Osborn waited until July, and then he let the ships in Cartagena out, figuring that it was too late for them to save Louisbourg. Sure enough, Louisbourg fell to the British in the same month, so the French ships returned to Toulon instead of going on to North America.

By the time Spain got involved in the war, France was ready to throw in the towel. Spain's only motivation was revenge, for two hundred years of injury and humiliation at the hands of the British. But once they joined the French, instead of getting even, they suffered more humiliation. The British invaded Cuba and took Havana in 1762, while another British squadron sailed to the other side of the globe, and took Manila in the Philippines. To get those important cities back, Spain had to surrender Florida.(17)

Meanwhile in the Caribbean, the British scooped up all the French islands except St. Domingue. At the peace talks the British negotiators told the French they could either have New France (Canada) back, or the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique; the French chose the latter, because they were making a bigger profit from sugar than they were from furs. Still, their victories in Canada and India put the British in a generous mood; with the 1763 Treaty of Paris they returned most of the captured islands to France. The only Caribbean conquests they kept were Dominica, St. Vincent, Grenada and Tobago.

In an attempt to make up for the losses suffered in the war, King Louis XV made an ambitious attempt to settle French Guiana in 1763. The 12,000 colonists he sent were lured by stories of the land being rich with gold. What they found instead were hostile natives and tropical diseases; no preparation was made for them at the landing site, and even fresh water was not available. By 1765 only 2,000 were still alive, and they fled to three small offshore islands: Royal Island, St. Joseph, and the infamous Devil's Island.(18) After they returned to France, a long investigation resulted in the imprisonment of the expedition's incompetent leaders, and the terrible stories of the survivors talked everybody out of colonizing French Guiana for the next thirty years.(19)

The French also tried colonizing the Falkland Islands. They established Port St. Louis, on East Falkland in 1764, and gave the islands the name of Îles Malouines, which would later be translated into Spanish as Islas Malvinas, Argentina's current name for the place. In 1765 a British captain named John Byron sailed to the western part of the Falklands; unaware that the French were already in the east, he claimed the islands for Britain, and a British outpost, Port Egmont, was built on the same spot a year later. Then Spain reminded the British and French that this was supposed to be Spain's part of the world. There was a brief war scare when both Britain and Spain sent armed ships to the Falklands. The French agreed to leave, and after Spain promised to compensate the French for their loss, it took Port St. Louis and renamed it Puerto Soledad (1767). The British chose to stay until the American Revolution required that they send their ships elsewhere; Port Egmont was abandoned in 1776, though the British left a plaque which said that they still owned the place. Spain kept a governor there until 1806; they also left because of the revolution in their colonies, and Spain also left behind a plaque asserting that the Falklands were theirs. That last Spanish colonists were withdrawn after Latin America's revolutions began, by the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata (1811).

The changed geopolitical situation after the Seven Years War, and the British response to it, caused tensions to rise between London and the North American colonies, which eventually led to the American Revolution (1775-83). The first three years of that war were strictly a North American affair, because the American Patriots were fighting alone with just a few ships, so most of the land and sea battles were within a few hundred miles of North America's Atlantic coast. The exception was the first US marine action, at Fort Montagu, a small fort guarding Nassau in the Bahamas. In 1776 the Continental Congress heard that the British had stored two hundred barrels of gunpowder at Fort Montagu, so it sent eight ships and 234 marines to capture this supply. They took the fort without a fight (the Bahamian militia had retreated to Nassau itself), but the gunpowder had been removed a day earlier, so the marines hauled off what the fort did have: forty-six cannon and thousands of cannonballs.