| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 7: THE VIKING ERA, PART II

741 to 1000

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| Iconoclasm: Act II | |

| Charlemagne | |

| The Carolingian Renaissance | |

| Wessex and the Carolingian States | |

| The Fury of the Northmen | |

| Alfred the Great | |

| The Atlantic Saga | |

| Commerce in the Viking Era |

Part II

The Church Backslides and Splits

Although the Lombard threat forced the pope to surrender the territory controlled by Rome to the Franks, he hoped to keep his freedom of action. However, to get Frankish support he had to let the Franks call the shots for a while. Pope Zacharias, for instance, gave Pepin the Short permission to assume the crown of Clovis in 750, but Pepin waited until the next pope, Stephen II, traveled across the Alps to anoint him with his own hand before he accepted (751). Likewise, Charlemagne had the Byzantine attitude that monarchs outranked the Papacy, so the popes of his reign, feeling that it would be unwise to provoke trouble, meekly accepted a secondary position under him. Yet because the Carolingians allowed the popes to crown them first kings and then emperors, they were more than halfway to admitting that they needed the Papal seal of approval. It looked like the title of emperor was something only a pope could grant, rather than something a prince could inherit. So when the Papacy regained its independence from Charlemagne's weak successors, people started asking: Who was the ultimate leader of Christendom, the emperor or the pope?

The Papacy now expressed its most extreme claims through a document called The Donation of Constantine. Supposedly written when Emperor Constantine I moved to Constantinople, it stated that he was leaving rule over the whole West to the Vicar of Christ, namely the pope. All kings in western Europe were thus nothing more than tenants of the pope's land, and their positions had to be ratified by him. Although it sounds like a big deal, nobody bothered to ask why previous popes and monarchs had never mentioned this formality, nor did anybody ask why it had taken more than four hundred years to find Constantine's will. Now by threatening to withhold their blessings, the popes could determine the legitimacy of a king, and thus look more important than any monarch. Yet the darkness of ignorance was a two-edged sword; if it made possible the acceptance of an obvious forgery, it also meant that men were too illiterate and life was too chaotic for any document to have much effect.(26) For example, Papal authority over the Church had never been challenged by the Carolingians, but with the disintegration of the feeble bureaucracy that passed for a government under Charlemagne there was no way to turn Papal prestige into real power. Papal commands to the Church could not be heard above the clang of arms; Papal calls to the kings for peace were answered with the suggestion that the pope ought to mind his own business. The pope soon found that he could not even control Rome, let alone the Papal State. As confusion increased the pope became the puppet, not of a great power that could at least maintain the dignity of the Papacy, but of the Mafia families that controlled things in central Italy.

The decline of political power in Italy was the beginning of a trend toward disunity that would characterize the peninsula for most of the next millennium. It was helped by the attacks of Moslem fleets from the other side of the Mediterranean. Previously when there were battles on the sea between Byzantine and Arab ships, the Byzantines usually won. The trend in favor of the Arabs began when Moslem Spain built a navy, and this fleet conquered Ibiza (798) and Crete (823). In 827 the Aghlabids, a Moslem state based in Tunisia, landed on Sicily; they were invited there by the Byzantine admiral Euphemius, who got in trouble with Constantinople by marrying a nun! They followed this up by invading Sardinia in the same year, by sacking Rome in 846, by taking Bari, on the heel of the Italian "boot," in 847, by conquering Corsica in 850, and by capturing Malta in 870; in 878 they sacked Syracuse, and Sicily's greatest city was never important again. Bari became a short-lived emirate (847-871), and a base for future raids on Italy. Nobody else in the neighborhood could stop them, because the Byzantines only had a few towns left in Italy, while the Lombard principality broke into three parts, with Salerno seceding from Benevento in 849, and Capua from Salerno in 860. Eventually, the pope had to call in Louis II, the king of (northern) Italy, to take back Bari. However, the Lombards understandably didn't want to submit to a Carolingian king, so to keep their independence, they invited the Byzantines to come back (873). Bari went to the Byzantines, and Emperor Basil I succeeded in strengthening the imperial position in the south, but inasmuch as he couldn't conquer his Lombard allies, the result was a six-part division of Italy south of Rome: the Byzantine province in the "heel" and "toe," the three Lombard states, and the ports of Naples and Gaeta, which were officially Byzantine but isolated and thus nearly independent.

The ninth and tenth centuries saw Rome's political factions appoint, depose, and sometimes even murder popes to get someone of their own choosing on the Papal throne. Because of that, several degenerate characters who normally would not have qualified for the job got it during this time. Just between 896 and 904, seven popes and one "antipope" rose and fell from power, of which six were murdered. One of them, Pope Stephen VI, took revenge on a rival, his predecessor Formosus, by having the dead pope's body dug up, propped in a chair, and put on trial; after conviction, the body was thrown in the Tiber River. Stephen also declared all ordinations performed by Formosus to be invalid, meaning that a bunch of clergymen instantly lost their jobs. Seven months after the trial, Stephen was overthrown, and strangled while in prison.

The so-called "Cadaver Synod." Here Stephen VI shouts at the late Formosus. In his vitally-challenged condition, Formosus could only respond by dropping pieces of himself, so Stephen had a frightened acolyte stand behind the chair of Formosus, instead of a lawyer. For example, when Stephen asked, "Why did you usurp the Papacy?", the acolyte answered for Formosus, "Because I was evil!"

It took two short-lived popes to overturn the Cadaver Synod rulings and restore the annulled ordinations. That wasn't the end of the story, though, thanks to the actions of another pope, Sergius III. He had been elected pope in 898, but a rival candidate, John IX, was backed by soldiers from the duke of Spoleto, so John was installed while Sergius was exiled and excommunicated. A few years later, however, an antipope named Christopher overthrew the pope at that time, Leo V. The military commander of Rome refused to accept this coup, so Sergius was invited to lead the faction that opposed Christopher, and when it won, Sergius became pope a second time (904-911). Sergius lasted for seven years (a venerable reign by ninth and tenth-century standards!), because he had both Leo V and Christopher strangled, and because he had an affair with an influential teenage girl named Marozia (see below). Unfortunately he was also a fan of Stephen VI and a participant in the Cadaver Synod, so he messed up things by reinstating all of Stephen's decrees, forcing all those who had been ordained by Formosus to be re-ordained.

In the early tenth century two of the most important figures in Rome were women, Marozia and her mother Theodora. Theodora was the matriarch of the powerful Crescentii family, and was also the mistress of a pope. This pope, John X, was imprisoned by Marozia in 928, and he quickly died under her care. The next two popes were caretakers elevated by Marozia, one of whom she later had killed; then she installed her illegitimate son by Sergius, now seventeen years old, as Pope John XI. However, she also had a legitimate son, Alberic, with the Duke of Spoleto (also named Alberic), and when the younger Alberic could no longer tolerate his mother playing favorites with John, he deposed and locked up both of them. Nineteen years later (955), Alberic's own son (and the grandson of Marozia, mind you) became the treacherous Pope John XII. John XII acted like a tenth-century Caligula, castrating nobles who displeased him, ordaining a deacon in a stable, setting houses on fire, appearing in public wearing a sword, helmet, and breastplate, indulging in open love affairs and drinking to the health of the devil. Two hundred years after cutting itself off from Byzantium, the Papacy was a hive of chaos and debauchery; for the tenth century, some historians call the Papacy a "pornocracy."

It was a similar story with the local church. All over western Europe church property was either looted and destroyed by raiders like the Vikings and Moslems, or it fell into the hands of the local nobility. Noblemen treated church offices as their own, rewarding friends or servants with them, or selling them to anyone with the money (the sin of simony, see footnote #5). As one might expect, this produced a clergy that was ignorant, shirked its duties, and acted immorally.(27)

With the end of Iconoclasm in 843, a formal reconciliation between Constantinople and Rome took place, but then minor doctrinal differences arose to keep East and West apart until the split became permanent. At first the issue was the relationship between Church and State, but as the power of the Papacy declined it switched to an argument over the Holy Spirit. Now that the Church had finished a centuries-long debate on the natures of God and Jesus, curiosity seems to have arisen concerning the third member of the Trinity. Did the Holy Spirit originate solely from the Father, as the East believed, or did it contain part of the essence of both Father and Son, as the pope now asserted? When the Papacy added three words, the so-called filioque ("and the son") to the part of the Nicene Creed that mentioned the Holy Spirit, Constantinople decided the western Church was a heresy beyond redemption. Although the formal split between Catholicism and Orthodoxy did not take place until 1054, for most of the two centuries preceding it the eastern and western bodies of the Church were no longer on speaking terms with each other.

The Byzantine monasteries lost many of their members and much of their wealth during the iconoclastic controversy, because they opposed the imperial decrees and thus attracted official persecution. The type of monastery started by St. Benedict in the West did better, as noted in the previous chapter, but in the ninth and early tenth centuries there was a sharp drop in Benedictine standards. As noted before, this was because the monasteries grew rich; the monks managed their land very responsibly by draining swamps, digging wells, and building mills. The downside was that laymen had less respect for monks who had fun too often, and there was a lot of this when their hard work paid off. Communal life was abandoned, monks got married and shared the income of the monastery, and sometimes their lack of discipline made them a menace to the neighborhood.

What the monks needed were new rules and regulations, and these came in 910 when William the Pious, Duke of Burgundy, founded a new monastery at Cluny; under its energetic abbot, Odo, it soon became a model for the strict observance of Benedictine rule. Unlike the older Benedictine monasteries, which were autonomous and answerable to nobody but the pope, the Cluniac monasteries were rigidly organized and controlled by the one at Cluny. It was an immediate success. Zeal for reform spread, and by the twelfth century the order of Cluny had 1184 houses. Kings and other wealthy benefactors gave generously to Cluny until it was able to build the largest church in Western Europe, surpassing even St. Peter's Basilica in Rome; the abbot of Cluny became the second most powerful man in the Catholic Church.

With the Cluniac reform the Western monastery became a more important part of the economy and society than its Eastern counterpart did. It served as an oasis of peace, learning and stability, irrigating the potentially fertile ground around it. The Cluniacs were also responsible for creating the concept of Christendom--the idea that Christians belonged to a superstate that transcended all borders decided by kings or differences in language and custom. The idea of universal brotherhood, a common feature of the early Church, returned, and many clergymen began to repeat a popular Cluniac maxim: "Away with anyone who thinks that God is merely local."

Those bishops who supported the reforms formed a "Peace of God" movement, which met in Aquitaine in 989 to condemn private warfare. Out of it came the "Truce of God," a pledge by armed men either to renounce acts of violence altogether, or to restrict them to certain days of the week (Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays); those who took the vow also agreed to leave some non-combatants alone.(28) Since the West did not yet have any strong monarchies or police forces, the Truce of God was a considerable improvement, and was endorsed by later Church councils. Thus, the Church played a major role in the upswing of prosperity that heralded the opening of the second millennium A.D..

Basil the Magnificent

When we last looked at the Byzantine Empire, the Empress Theodora was ruling on behalf of her son, Michael III. In 855 Michael was furious that Theodora would not let him see his mistress Eudocia, so he seized power in a palace coup and had his mother sent to a monastery. Under him the Empire's situation started to improve, because it was no longer constantly fighting barbarians and heretics, and the main Moslem state, the Abbasid Caliphate, was breaking up. Michael's uncle, Bardas, halted the Empire's shrinkage by leading a military campaign that recovered several Thracian cities from the Bulgars (855-856). And that wasn't all; Bardas got more than one opportunity to fight the Arabs. Although he could not stop their advance in Sicily and southern Italy, he fought a successful defensive war on the eastern front which saw him advance as far as Amida in Iraq, while the Byzantine navy raided Damietta in Egypt. Finally, in 860 he beat off a Varangian (Viking) attack on Constantinople. The Varangians had to get past other barbarians (Petchenegs, Magyars and Bulgars) to reach the Black Sea, so when they arrived, they were spread too thin to be a serious threat. Still, we're mentioning them here because this was the first meeting between the Byzantines and the founders of Russia. That was the beginning of a very productive friendship, the evidence of which still exists in the Russian Orthodox Church.

Michael could not take credit for any of the Empire's recent successes, because he was only interested in bedrooms, drinking and the race track. Fortunately he let more capable individuals handle matters of state, especially Bardas, who was a very dedicated and incorruptible administrator. Besides the wars against the Bulgars and the Arabs, Bardas was responsible for some successful missionary activities. By this time more than half of Europe was Christian, so the current Bulgar Khan, Boris I (852-889) thought he should convert to Christianity, too, but instead of sending his request to Constantinople, he sent it to Louis the German, king of the eastern Franks. Had this overture succeeded, it would have meant a Catholic kingdom right on Constantinople's doorstep, and the Byzantines wouldn't stand for that; a Byzantine attack on Bulgaria in 863 convinced Boris that becoming Orthodox would be a better idea. By the end of the year there were Orthodox missionaries working in Bulgaria, starting with the royal family. Meanwhile two other Byzantine missionaries, St. Cyril and St. Methodius (more about them later), went to the western Slavs in Bohemia and Moravia.

Another official of Michael's court with impressive achievements was Photius, an in-law with an excellent education who became the foremost scholar of the late ninth century. Photius first gained the attention of the imperial family because his brother married Michael's aunt, and during the next decade he served as a captain of the guard, an imperial secretary, and an ambassador to Baghdad. When the current patriarch, Ignatius, accused Photius of having an illicit love affair and wouldn't let him enter Hagia Sophia, Michael and Bardas came to the rescue by accusing the patriarch of treason and removing him from his post. Then they decided to have Photius take his place, though he was a layman, so in a four-day period they ordained him lector, sub-deacon, deacon and priest, allowing him to become patriarch on Christmas Day of 858. Photius was an odd choice for the job because he wasn't very interested in theology--rumors circulated about him muttering secular Greek poetry when he should have been reciting the Divine Liturgy at church services--but he became interested when Pope Nicholas I challenged his authority, because his predecessor had been deposed without any sort of trial. Over the course of the 860s Photius and the pope excommunicated each other; Photius became the East's chief spokesman in the war of words over who was the ultimate leader of the Church, and where the Holy Spirit came from (see the previous section).

Byzantium's silver age began with a spirited horse. Michael III's favorite hobby was racing horses, and in 858 he had one that no one could ride. When all attempts to tame it failed, Michael became depressed and started drinking; this put those around him in peril, for this emperor committed acts of cruelty, and even ordered sudden executions, when frustrated or provoked. To save the day, one of the emperor's courtiers put himself at risk, by announcing that one of his servants was a strong and gifted Macedonian peasant named Basil, and he could probably handle the animal. Michael summoned Basil, who turned out to be a magnificent physical specimen.

Under the emperor's gaze, Basil approached the horse. He grabbed the horse's bridle with a powerful hand and forced the animal to stand still; with the other hand he gripped the horse's ear and spoke softly into it. Whatever he said, it had an amazing effect; one moment later the untameable horse was a docile servant of the emperor. Michael was overjoyed, and promptly drafted Basil into the imperial palace guard.

This was the first step in a remarkable rise to power. Basil had come to Constantinople with nothing but the clothes on his back, and though illiterate, he enjoyed success because of luck and his physical abilities. Now he got involved in the intrigue which made up Byzantine politics. Soon after Basil entered imperial service, the imperial high chamberlain was fired, and Basil took his job. Michael also wanted a respectable way to bring his mistress Eudocia into the palace, so he ordered Basil to divorce his wife, though they already had a son named Constantine, and marry Eudocia. However, Michael still considered Eudocia his property; after the wedding he took her back, and in her place gave away his sister Thecla, to become Basil's new mistress. Basil probably didn't like any of this, but an ambitious person will do strange things for power, so he complied with Michael's wishes and did not complain. When Basil and Eudocia had a son named Leo, rumors circulated about Michael being the real father.

As the emperor's new right-hand man, Basil started rumors against the previous favorite, suggesting that Bardas was scheming to take the throne for himself. Bardas heard about this while planning a naval expedition to take back the now Moslem-held island of Crete. Instead of running away or doing anything else to protect himself, Bardas decided to directly confront Basil on this matter, because he looked very impressive when dressed in his finest outfit. Basil was caught by surprise, and placated Bardas by swearing an oath that he had no ill intentions against the emperor's uncle. Then, thinking Basil was just another drinking buddy for Michael, Bardas went back to preparing for the reconquest of Crete. Suddenly, while all three of these noteworthies were with the army in Asia Minor, the rumors against Bardas began to circulate again. At the next council of war, Michael and Bardas were reviewing army preparedness, when Basil and his henchmen suddenly attacked the imperial uncle and hacked him to death. Michael approved of the killing but was apparently shocked by the violence of it. The expedition was called off, Michael sent Photius a letter informing him that Bardas had been executed for treason, and he adopted Basil as his son and co-emperor, aware that he now had no true ally but his protegé.

During the next few months, Michael sank deeper into debauchery, and Basil got a chilling warning that even his position was not secure; an unstable emperor can take back what he has given. After winning a horse race, the emperor threw a party, and a new acquaintance, a boatman, flattered him; Michael invited the fellow to remove Michael's royal red boots and try them on. Basil objected to this unseemly behavior, and the furious emperor turned on him and spat, "I made you emperor, and have I not the power to create another emperor if I will?" Unlike Bardas, Basil did not simply hope that things would turn out all right; the next time the emperor drunk himself into a stupor, Basil helped him to bed, like he had done so many times before, but left the bedroom door unlocked and came back with eight armed men. After making short work of the emperor's guards, Basil and his accomplices quickly finished off Michael.

Despite the treachery used by Basil to rise to the top, his reign (867-886) accomplished so much that now we call him "Basil the Magnificent." However, his first act as emperor was a fumble. Unlike his predecessors, Basil wanted to bury the hatchet, and reunite the eastern and western Churches. Because the current squabble was over the patriarch Photius, Basil removed him and brought back Ignatius. But Photius had never done him any wrong; in fact he served as tutor for Basil's children, and once produced a phony genealogy which claimed that Basil's ancestors were not really peasants, but descendants of Alexander the Great, Constantine I, and the Arsacids, the royal family that had once ruled both Armenia and the Parthian Empire! When he saw that his actions had failed to mend relations with the pope, Basil realized he had done Photius dirty. Therefore when Ignatius died in 877, he reinstated Photius for a second term as patriarch.

Because of his humble origins, Basil made the collection of taxes more fair by punishing venal officials and greedy landowners, and expressed clearly what the tax rates were so that taxpayers would know what was expected of them. He also recodified the civil law, which had not been revised since the time of Justinian. For this we sometimes call Basil the "second Justinian." Because Basil could not read, he obviously needed help from more learned men like Photius to go through the old laws, most of which were still written in Latin rather than Greek, plus three centuries of new laws, decrees and precendents. The recodification filled sixty books and was not completed until after his reign. Even so, an introduction (Epanagoge) to the law code and a summary of it (Procheiron) were produced while Basil was alive, and those works by themselves made the Byzantine lawyer's job easier.

When not busy reorganizing laws, Basil devoted himself to a massive building program in Constantinople, the first in at least a century, to repair structures that had been damaged by time and earthquakes, like the Hagia Sophia. When finished, the new buildings were so ornate that Basil boasted he had turned the capital into one big treasure house, which was itself a treasure. On the palace grounds he built a church to rival the Hagia Sophia, which was simply called the Nea Ekklesia (New Church). Unfortunately for us, nothing remains of Basil's architecture, which like so many other things from the Dark Ages, simply did not stand the test of time. In the case of the New Church, it was converted into a monastery in the eleventh century, stripped of its valuables when the Empire needed cash during its latter years, was used to store gunpowder after the Ottoman Turks captured the city, and was finally torn down after a lightning strike in 1490. Contemporary observers wrote that the gold, silver, mosaics and gems that went into the New Church made it truly dazzling, and we'll have to take their word on that.

On the military front, Basil fought the Moslems in Asia Minor for fourteen years (871-885), usually doing better than his opponents. He also faced opposition in the east from the Paulicians, a heretical movement that tried to reform the Orthodox Church during the years of iconoclasm, and then joined the Moslems against Byzantium when it failed. Basil won his most important victories by breaking the Paulician army in 872, and capturing Samosata from the Moslems in 873. The surviving Paulicians were relocated to the Balkans, and though they survived there and in Armenia for another millennium, they never were a threat to the Empire again. In the west, Basil lost the Sicilian city of Syracuse to the Moslems, but expelled them from the mainland and took back south-central Italy from the Lombards, as covered previously. Finally, by cooperating with Louis the German, he succeeded in clearing the Moslems out of Dalmatia and the Adriatic Sea.

Basil's reign ended on a tragic note. His first and favorite son, Constantine, died in 879, and he never got over that. He had three other eligible sons, Leo being the eldest, but as we noted before, it was questionable whether Basil was really the father, so Basil did not like Leo much. Therefore, instead of just crowning Leo as his heir, he crowned Leo and one of Leo's brothers, Alexander, as co-emperors. The patriarch Photius didn't like Leo either, because he rightly feared that he would be out of a job when Basil died. Accordingly, Photius tried to comfort the emperor by holding a séance to contact the spirit of the dead prince, and even had Constantine canonized as a saint. Still, the emperor was so grief-stricken that he had to leave the affairs of government to others, while he tried to forget his sorrows by hunting. On a hunting trip in 886, a huge white stag impaled the emperor on its antlers, and because the antlers caught under Basil's belt, the stag carried and dragged Basil for sixteen miles. A servant chased after them and freed the emperor by cutting off the belt, but Basil died of internal bleeding nine days later.

Well, that is the official report of what happened. Today historians are skeptical of it, for several reasons. First, the emperor was no longer mentally competent, so one wonders why his guards weren't around to prevent such a mishap. In addition, Basil was famous in youth for his strength, so it seems even less credible that he could not kill the stag, or at least cut himself loose. Finally, the story came to us from a rescue party led by the father of Leo's mistress; surely this man knew that Leo's life was in danger as long as Basil lived, and he had everything to gain if Leo became the next emperor. Therefore it appears more likely to us that Basil's reign ended the same way it had begun--through assassination.

The Macedonian Revival Continues

The Macedonian dynasty ruled Byzantium for nearly two centuries (867-1056) and produced two outstanding emperors, both named Basil. Most of the seven emperors between Basil I and Basil II were also competent, but the three with military skills were all officers who usurped the throne and married into the imperial family, not necessarily in that order. While they were in charge, it must have looked like the descedants of Basil I had become a dynasty of figureheads, like the Merovingians and Carolingians in France.

The first two emperors were both sons of Basil I: Leo VI (886-912, also called Leo the Wise), and Alexander (912-913). Leo caused a major scandal because his first and second wives died without giving him a son, so he went ahead and married again, and again. The Church made it clear that it considered more than two marriages sinful, but the dynasty needed an heir, so when Leo finally got a son from his fourth wife, that son was automatically a candidate for the throne, and eventually crowned as Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (913-959).

Constantine VII was strictly interested in intellectual pursuits, and turned military affairs over to his father-in-law, an admiral named Romanus Lecapenus. He did this because a strong hand was needed on the frontier; the conversion of the Bulgars to Christianity had not improved them much, and they waged a long on-and-off war with Byzantium (894-927), that only ended when both sides realized that Bulgaria could not take Constantinople by force of arms. After that Romanus and a general under him, John Kourkoas, campaigned in Armenia in 924, fought the Abbasids along the eastern frontier in 926, and took the city of Melitene in 934. But as in other times and places, a military leader will get the idea that he could--and should--lead more than just soldiers and ships. This temptation becomes especially strong when the military leader is successful, and the head of state is weak. In 920 Romanus muscled in and forced Constantine to crown him co-emperor, but he proved to be a gentle usurper; Romanus continued to call Constantine the senior ruler, even after he crowned his own three sons as additional co-emperors. In the end Constantine outlasted all of them. Romanus I was arrested by his sons in 944 and packed off to a monastery; before the year was over, the same fate happened to the sons. Constantine was happy to see them go, because for more than twenty years he was in danger of being deposed--or worse. For his son Romanus II, Constantine wrote a manual on how to be a good emperor, entitled On the Governance of the Empire, but the younger Romanus died after only ruling for four years (959-963), and most of his short reign was spent pursuing pleasure. Had he lived longer, he might have matured into a statesman, but we have no way of knowing for sure.

Romanus II had a wife named Theophano, who like the eighth-century empress Irene, was a native of Greece, beautiful, and ready to do anything to keep the throne. Their marriage produced three children: Anna, Basil and Constantine. In 962 Romanus crowned the two boys as co-emperors, so henceforth we will call them Basil II and Constantine VIII. But when the father died, Basil was only five years old, and Constantine was two; it probably did not look like either would live to reign. To protect the kids and herself, Theophano married the Empire's best general, an Armenian named Nicephorus Phocas, though he was twenty-nine years older than her, and reportedly ugly enough to give those who saw him nightmares. Officially Nicephorus was just a regent for the young sons of Romanus and Theophano, but he thought he could push them aside and become the founder of a new dynasty, so we call him Emperor Nicephorus II (963-969).

Nicephorus II showed his military skill in 960 when he led the long-delayed expedition against Crete, and reconquered that island by March 961. After he became emperor, he spent most of his time campaigning. In the west, the Empire lost the last part of Sicily it held to the Fatimids, a new Moslem state in North Africa (965), and on the Italian mainland, the Empire's generals were defeated by the German emperor Otto I. However, he did much better in the east. The campaign he led from 964 to 966 recovered Cilicia, while another led by a patrician named Nicetas took Cyprus in 965. On the Balkan front, he taught the Bulgars a lesson by paying the Russian prince Svyatoslav to attack them. In 969 he invaded Syria and captured both Antioch and Aleppo. These conquests happened not only because the health of the Empire had improved, but also because its enemies were chronically divided among themselves. Nicephorus further divided them by keeping Antioch, but he left Aleppo to the Hamdanids, the Arab family currently ruling Syria; the Hamdanids now became a vassal state under Byzantium.

In classical times, Antioch was the capital of the Seleucid Kingdom and the third largest city of the Roman Empire; more recently it was the seat for one of the four patriarchs of the Orthodox Church. Therefore its capture should have been the greatest triumph of all. Instead, the people of Constantinople threw rocks and garbage at Nicephorus when he came home, and he had to barricade himself in the palace. His policy of raising taxes and slashing spending on non-military parts of the budget (to pay for the armed forces) had made him very unpopular, not to mention his ban on building new monasteries so that there would be still more money available for wars. Worse, the empress had second thoughts about her new husband, and took his nephew, John Tzimisces, as a lover. One night in December 969, John Tzimisces led a group of assassins into the palace; by disguising themselves as women, they got past the gates and were able to hide in the chambers of the empress. There was an alarming moment when they found the emperor's bed empty, because Nicephorus liked to sleep on the floor, but then they found Nicephorus, struck him down and decapitated him. The sarcophagus he was later buried in contained an inscription that summarized his career with one sentence: "You conquered all but a woman."

In all ways, John Tzimisces did better than his predecessor. Polyeuctus, the current patriarch of Constantinople, forced him to atone for his crime by banishing the empress Theophano, before he would allow a coronation. Then John Tzimisces secured his position by marrying Theodora, a daughter of Constantine VII. However, he allowed the children of Theophano to remain in the palace, because they would not be old enough to threaten him for many years. The immediate threat came from another general, Bardas Phocas, who launched his own bid for the throne. Fortunately the new emperor's brother-in-law, Bardas Sclerus, was an even better commander, and a campaign from him defeated the rebellion; Bardas Phocas was captured and exiled to the Aegean island of Chios.

Being a military man, John Tzimisces had no trouble picking up on the battlefield where Nicephorus left off. In the Balkans, Svyatoslav, the Russian leader, had become overbearing; not only did he refuse to hand over the former Byzantine lands he had taken from the Bulgars, he even built a new capital for himself, Pereyaslavets, on the banks of the Danube. These moves made Russia more dangerous than the Bulgars had been, so John went to the Danube for a personal meeting with Svyatoslav. When that failed to persuade the Russians to leave, John sent Bardas Sclerus with an army to drive the Russians away (970-971); eastern Bulgaria and Dobruja (Romania's Black Sea coast) now came under Byzantine control. On the eastern front, the Arabs began to make trouble again, so John Tzimisces campaigned twice against them, invading northern Iraq in 972 and Syria in 975. The latter was a great success, that saw Byzantine armies capture several important Levantine cities: Emesa, Baalbek, Damascus, Tiberias, Nazareth, Caesarea, Sidon, Beirut, Byblos and Tripoli. Jerusalem should have been next, but here the Fatimids, who had recently conquered Egypt, arrived on the scene with an army strong enough to keep John from taking the holy city. On the way home from the campaign John Tzimisces fell ill and died (976); the Fatimids then occupied John's conquests before another Byzantine army showed up.

Introducing Basil II

For the past generation the imperial household had been managed by Basil Lecapenus, a eunuch and the illegitimate son of Romanus I. This Basil, whom we will call Basil the chamberlain to distinguish him from the emperors, was also chief of the central administration and president of the Senate; he got these jobs because the soldier emperors were too busy with their wars to be bothered by them. A rumor went around that Basil the chamberlain had poisoned John Tzimisces, to avoid being punished for his own corruption. Whether or not this was true, he recognized Basil II and Constantine VIII as the rightful emperors; both of them were now teenagers, but he probably felt he had the experience to continue acting as the power behind the throne.

Basil and Constantine may have had the best claim, but the two previous emperors had been generals, and they ignored the real princes most of the time. Therefore Bardus Sclerus, who had been solidly loyal to John Tzimisces, expected he would get the crown next. It looked like he would take over without too much fuss, when his troops proclaimed him emperor, and he quickly gained control over the Mediterranean fleet, and most of Asia Minor. Nicaea came under siege, and Sclerus had plans to cross the straits and attack Constantinople next. Basil the chamberlain responded by sending out the fleet of Constantinople, and using the terrible weapon of Greek fire, it burned up the rebel fleet. That helped a lot, but Sclerus continued to win on land, so in 978 Basil made the risky move of letting Bardas Phocas come back from exile, and put him in command of the imperial army. This was risky because Phocas also wanted to become emperor, and while he could be trusted to get rid of a rival general with the Empire's blessing, what about after that? Sclerus and Phocas met in three battles in Asia Minor; Sclerus won the first two, but Phocas always managed to escape with most of his troops. At the third encounter, on March 24, 979, Bardas went for the heroic approach, challenging Sclerus to fight him in single combat, and letting that decide the battle. Remarkably, Sclerus accepted, though strategy had worked better for him than chivalry, and Phocas was a much larger man than him. The duel was over almost as soon as it started; Sclerus cut an ear off the horse of Phocas, but Phocas knocked him down with a serious head wound. The army of Sclerus ran away, thinking he was dead, and Sclerus fled to the Arabs, eventually becoming a refugee at the caliph's court in Baghdad.

Once the civil war was over, Basil the chamberlain made Bardas Phocas happy by giving him the title of Domestic of the Scholae (Commander in Chief), and sent him off to fight the Moslems in Syria. By this time Basil II and Constantine VIII had grown up, and when they remained quiet about the current political arrangement, Basil the chamberlain must have felt everything was going his way. The truth was that Constantine VIII was indeed an intellectual lightweight like his father, but Basil II was studying everything around him, learning his duties and how to play political games. He had a quality that few medieval nobles had--patience--and he had a tremendous supply of it; that would cause all his enemies to underestimate him. The first who did was Basil the chamberlain, who saw Basil the emperor exchange diplomats with the Arabs for years, and apparently believed a rumor that Basil II was going to hand over the Syrian city of Aleppo to the Caliphate in return for Sclerus. But now Basil II was ready to rule by himself, and he struck first, which must have surprised everybody. In 985, he accused Basil the eunuch of plotting against him with Bardas Phocas, had him arrested and exiled, confiscated all his lands and possessions (which included the lavish furnishings for a monastery he had built), and declared all laws issued by Basil the eunuch's administration to be null and void.

The civilian administration was now clearly under his control, but Basil's position as emperor could not be considered secure while Bardas Phocas and Bardas Sclerus were both alive. He also faced a more immediate threat from the Bulgars, who were riding high in the late tenth century. At this point they ruled not only Bulgaria but also most of the Balkans (northern Greece, northern Macedonia, Albania, Serbia, Kosovo and Montenegro), and as you might expect, they wanted to regain the eastern land they had lost to Byzantium in 971. For a few years after that defeat, a civil war among the Bulgar princes and generals kept them at home, but from 976 onward they began raiding Byzantine territory again. Then an anti-Byzantine revolt broke out in Macedonia and Thessaly, which the Bulgars supported, so Basil led 30,000 soldiers into Bulgaria in 986. His objective was the city of Sofia, but the expedition was a disaster. Basil had no military experience, the troops suffered from an unusually hot summer, and the Bulgar prince Samuel resorted to guerrilla tactics, harassing them with a series of raids, instead of facing the Byzantine army in a conventional battle. After besieging Sardica for three weeks, the Byzantines decided that was all they could take, but on their way home, they were ambushed in a mountain pass called the Gates of Trajan. Most of the soldiers were killed or captured, and the Bulgars captured the imperial insignia as well, but Basil escaped, and swore that some day he would come back and beat the Bulgars. This probably sounded like empty boasting; the losers of other contests, in other times and places, have promised a rematch with different results. Indeed, the pope was so impressed by Samuel's victory that he recognized him as the next tsar of Bulgaria, and Samuel went to Rome to be crowned in 997. Still. they were underestimating Basil again; this would be his only defeat.

The battle of the Gates of Trajan was seen by the Byzantine generals as a sign that the emperor was weak. Bardas Phocas decided that this was his opportunity to take over, and he invited Bardas Sclerus to join him, promising to divide the Empire between them if they succeeded. The caliph of Baghdad gave Bardas Sclerus enough money to raise a new army, and sent him away with his blessing. The alliance of generals did not last long, though; instead of marching on Constantinople with Sclerus, Phocas had him arrested and thrown in prison. Then, with the most of the army backing him, he conquered Asia Minor; Phocas was so confident of victory that he began wearing a crown and purple robe, as if he was already the emperor. However, Basil had another trick up his sleeve. At this point, Vladimir I, the grand prince of Russia, converted to Orthodox Christianity (988), giving Byzantium the powerful ally it needed. Of course a successful missionary effort was part of the reason for this, but Vladimir also said he wanted to marry a Byzantine princess, and though he already had several wives, Basil agreed to send his sister Anna, on condition that he convert and provide fearsome Viking warriors as mercenaries.

Using these Vikings as the core of a new force, Basil crossed the straits to Abydos, the city on the Asian shore of the Dardanelles that Phocas currently had under siege. The Vikings and the Greek fire of Basil's ships slaughtered the besiegers, and Basil marched on Phocas, who was currently at Nicaea with a reserve force. When the two armies met in battle (April 13, 989), Basil kept morale up on his side by holding an icon of the Virgin Mary in one hand and his sword in the other, while shouting encouraging words to his troops. Phocas in turn resorted to the same trick he had used once before; he challenged the emperor to a duel. However, this match ended even more quickly than the duel between Phocas and Sclerus; as Phocas charged the emperor, he suddenly collapsed and died of a stroke. To medieval Christians there could be no clearer sign that God was on the emperor's side, and the army of Phocas was immediately scattered.

The widow of Bardas Phocas tried to keep the rebellion going by releasing Bardas Sclerus. But years of exile and imprisonment had taken their toll. Now Sclerus was a broken man, nearly blind, and he did not have long to live. After few months of token resistance, he negotiated a settlement with the emperor. Basil had shown no mercy to the followers of Phocas, but surprisingly, he forgave Sclerus and let him live on an estate for the rest of his days.

Around the same time, a terrible earthquake severely damaged both Constantinople and the nearby city of Nicomedia (October 25, 989). One of the casualties was Hagia Sofia; part of its great dome was knocked down. Fortunately Basil had an excellent Armenian architect named Trdat, and he did a good enough job repairing the damage that the church reopened in 994, and it still stands intact today (well, nearly intact, if you count what the Ottoman Turks did when they captured the city, four and a half centuries later).

In 994 the Fatimid Arabs defeated the Byzantine forces on the Orontes River, besieged Aleppo and threatened Antioch. Basil at this point was interested in the Balkans, because of recent Bulgar advances, but Antioch was so important that he personally led the rescue army. To travel as quickly as possible, Basil provided 80,000 mules for 40,000 men, so that nobody would have to march on foot. Sure enough, the journey across Asia Minor, instead of taking three months, only took two weeks, and the army took the Fatimids completely by surprise, forcing them to withdraw. Then Basil went back to Europe. He had to return in 998 when the Fatimids attacked Antioch again, and this time he ravaged the Orontes valley and advanced to the walls of Tripoli before the Fatimids agreed to a ten-year truce. Thus, by 999 Basil had restored the status quo in Syria.

We still have to cover Basil's second war against the Bulgars. However, his reign is divided almost evenly between the tenth and eleventh century (976-1025), and the ultimate victory came after the turn of the millennium, so we will save it for the beginning of the next chapter. We will finish this section by looking at the relationship between the Byzantine army and civilian administration, during the Macedonian dynasty.

In the previous chapter we noted that Emperor Heraclius divided Asia Minor into four military districts called themes. When he did this, he had to swallow the feeling that it was dangerous to give both civil and military authority over a large area to a single man. Some commanders, like Leo III, did give into the temptation that such power gave them. Accordingly, the emperors after Heraclius reduced this threat to Constantinople by breaking the themes into smaller ones. By the time of Constantine VII, there were sixteen themes in Asia Minor (which included one in the Aegean islands), and twelve themes in Europe. Fortunately, pressure on the Empire slacked off after the eighth century, so this division did not bring disaster. In fact, after the Empire regained the initiative against its enemies, the sort of defense-in-depth strategy that the themes represented was no longer needed. Since the themes were now only strong enough to use in a defensive role, the tenth century saw the imperial government build a new strike force, to lead the way in conquests.

This new army was given first call on the resources of the themes. Into the strike force went foreign mercenaries known for their fighting ability, like the Vikings and Normans, and since they had to be paid in cash the emperor began asking the themes for money instead of men. As a result, the theme regiments got smaller while the strike force expanded. After a 300-year interruption the empire had returned to the old Roman system of tax-paying provinces and a paid professional army.

As the millennium came to an end, the Empire was in better shape than at any point since 600. The new army was a great success; it had to be, for both the Empire and the theme units now depended on it absolutely.

The Caliphate of Cordova

Which were the two most advanced countries in western Europe during the Dark Ages? The answer will probably surprise you. In the period covered by Chapter 6, it was Ireland; in the period covered by this chapter, it was Moslem Spain.

The only part of the Iberian peninsula that remained free of Islam after the initial invasion was the northern mountains; this contained the nearly inaccessible Basques and the Kingdom of Asturias, which had a tenuous claim to being the last part of the Visigoth state. In time they might have succumbed too, but strong Frankish leaders (Charles Martel, Pepin and Charlemagne) and Moslem disunity saved the day. Spain became the first province of the Islamic Caliphate to break away after the Abbasids took over in 750; the Abbasids slaughtered all but one member of the previous ruling family, the Umayyads. This survivor, Abd-al-Rahman I, escaped to Morocco, where he learned that Spain was in a state of near-anarchy. In the forty years since the Moslem conquest of Spain, twenty emirs or viceroys had been appointed by the Caliphs, and they were such cruel rulers that some part of the peninsula was always in rebellion, no Moslem leader would recognize anyone as his superior, and the various sheikhs waged vendettas against one another. Eighty high-ranking Arabs got together and decided that they must declare independence from the Caliph and unite under a leader of their own choosing, rather than wait for somebody in a far-off place like Damascus to send a governor they didn't care for. Accordingly, they invited Abd-al-Rahman to take over, so he made a triumphal crossing from Morocco, drove out the recently appointed Abbasid viceroy, and proclaimed Moorish Spain the independent emirate of al-Andalus in 756. Seven years later, he defeated an Abbasid army sent by Baghdad to remove him. In the northwest, the Christians of Asturias recovered Galicia by 771, putting their kingdom on a firmer footing.(29) Because of the Islamic split, the Moors could not look for armies to come to their assistance from the Middle East; most of the Islamic world stood aside while they fought, won and ultimately lost their battles in Spain.

Charlemagne recovered the area around Barcelona in several campaigns (778-802), and pushed to the Ebro River in 812. After him the Franks lost control of the "Spanish March" and it evolved into two separate states: the kingdom of Aragon (809) and the county of Barcelona (830). In the northwest, the Basques coalesced into a kingdom named Navarre (822), while the kingdom of Asturias captured the area around Burgos (860-899); henceforth this would be known as the county of Castile. From 910 to 951 Galicia was independent of Asturias; in 913 Asturias moved its capital from Oviedo to Leon, and subsequently changed its name to the kingdom of Leon. Because Leon was an inland town, the move meant that Spanish Christians were no longer looking to the Atlantic for their livelihood; the ocean at this point was too risky, being full of storms, Vikings, and who knows what kind of monsters. In 970 Navarre absorbed Aragon, so by 1000 there were three small Christian states opposing Islam in Spain.

The Islamic part of Spain was itself in an unstable state, even after the Umayyads took charge, because their authority was often challenged by the Arab and Berber governors around them. In fact, the Arab ruling class was always a small minority, no more than 20% of the population; the rest were Berbers, indigenous Spaniards(30), Jews, and slaves from Africa and eastern Europe. As a result, the Ummayad emir based in Cordova (also spelled Cordoba) played a political balancing act to keep himself at the top of the heap. For example, we know of at least one case where treachery was used to put down a rebellion. In 807 Amrus Ibn Yusuf, the governor of Toledo, pulled a trick that had done elsewhere (it happened to the Ummayads back in the Middle East), by inviting hundreds of his most important enemies to a banquet at his new castle. In the castle courtyard Amrus had a long ditch dug, and stationed his executioner next to it. The guests were brought in one at a time, and each was beheaded and thrown into the ditch.

Al-Andalus enjoyed its best years in the tenth century, under three excellent leaders: Abd-al-Rahman III (912-961), his son al-Hakam II (961-976), and Muhammad ibn Abu ‘Amir (981-1002). Abd-al-Rahman took for himself the title of caliph, meaning the spiritual leader of Islam, in 929, to show everyone else in Spain who was boss, and to compete with the Sunni caliph in Baghdad and the Shiite caliphs in North Africa. For this reason we call his state the Caliphate of Cordova. Under him Cordova grew to become a major intellectual center, with seventy libraries, until it was the largest city in western Europe; estimates of its population range from a hundred thousand to half a million. Remember, this was at a time when London and Paris were scarcely more than dirty villages.

Abd-al-Rahman spent a good part of his time on building projects, one of which was the grandest palace of Dark Age Europe, a veritable Versailles named Medinat al-Zahra (City of Zahra), after a favorite concubine; he lavished a third of the royal budget on it for 25 years, until it was completed in 961. Another was La Mezquita, the great mosque of Cordova, originally founded in 785. He made it the third largest mosque in the world, its most distinctive feature being a forest of red and white arches supported by columns. 850 of the original 1,300 columns still stand today; the rest are gone because in the sixteenth century, the Catholic Church ordered a cathedral built right in the middle of the mosque. Even the pious King Charles V thought this change of architecture was too much; when he saw the results, he told the Church authorities: "You have destroyed something that was unique and replaced it with something which is commonplace."

Abd-al-Rahman also cut down on the number of wars in the north, by putting a friendly king in charge of Leon. First he allied himself with Fernán González, an uppity duke who attacked the castles in Leon that weren't his already; González also wanted to be king so bad that he called himself the king of Castile, instead of merely its duke. Then in 956 Sancho the Fat became Leon's king, but because of the problem that earned him his nickname, his nobles, especially González, didn't want him around. They threw Sancho out, crowned a cousin, and Sancho's grandmother, Queen Toto of Navarre, wrote to the caliph, asking if there was anything he could do. Abd-al-Rahman responded by sending his court physician, Hasdai ibn Shapirut, a Jew who was also blessed with diplomatic skills (a few years earlier he had represented the caliph, on a mission to meet with Germany's Otto I). Shapirut convinced the queen that she would have to bring Sancho to Cordova, and the sight of a Christian prince coming to the caliph for help scored a political victory for Islam. Then Shapirut put his medical skills to work, subjecting Sancho to a strict diet for several months, until he had shed enough pounds to look like a proper king. When Sancho was ready to go home, Abd-al-Rahman sent a Moorish army to take the throne of Leon for him (960), and he didn't get involved when Sancho put the duke of Castile in his place, in 966.

Despite these successes, Abd-al-Rahman seems to have been a melancholy fellow. Near the end of his long reign, he wrote: "And in all that time, I have numbered the days of pure and genuine happiness that have befallen my lot . . . They amount to fourteen . . . Put not therefore your hopes in the things of this world." Under his son, al-Hakam II, the Zahra palace became a city in its own right, reportedly housing or employing 38,000 people. Moslem pirates terrorized the Mediterranean and even set up a base on the Riviera. In the 970s Morocco submitted to Spain, after the Shiite family ruling it, the Idrisids, became extinct. From there, Berbers were recruited in large numbers and sent north to terrorize the Christian kingdoms.

The next caliph, Hisham II, was only a child when he succeeded al-Hakam in 976, so three regents managed the government. One of them, Muhammad ibn Abu ‘Amir, was so brilliant and ambitious that soon he was ruling in all but name; this alarmed the other two (one was his father-in-law!), and they revolted, stirring up an uprising in the army and calling in help from Leon, Castile and Navarre. Ibn Abu ‘Amir quickly crushed the rebellion, and then turned against Leon, defeating King Ramiro III and sacking the cities of Zamora and Simancas (981). These triumphs earned him the title al-Mansur bi-Allah (victorious through Allah); Western writers called him Almanzor or Almansor. In 985 al-Mansur marched north again, this time against Barcelona; the Barcelona Christians had stayed out of the previous conflict, but still he torched their city, and massacred or enslaved everyone in it. When Leon expelled some Cordovan mercenaries in 987, al-Mansur saw this as a good reason to teach the Christians another "lesson." This time he ravaged all of Leon, including the capital, stirred up a rebellion against Leon in Castile, and exacted tribute in return for peace. As a final triumph against Christianity, he invaded Galicia in 997, destroyed the church of Santiago da Compostela (but he spared the tomb of the Apostle James), bringing back the church's great bronze bells as trophies to show in the Cordova mosque. However, he was more interested in imposing Cordova's will than he was in finishing off Spanish Christianity; Christian kings paid their tribute and lived to see another day.

The Caliphate of Cordova, 1000 A.D.

The First Reich and the Recovery of Christendom

Christianity regained its confidence in the ninth century, after 400 years on the defensive. This showed in the launching of vigorous missionary activity into northern and eastern Europe from both the Orthodox and Catholic Churches. The Orthodox won the first prizes; they converted the Danube Bulgars (865) and Serbs (879), while a third mission, led by St. Cyril and St. Methodius, started work in the Kingdom of Great Moravia in 863.(31) This was a Slav-ruled state in what is now the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and parts of Poland, Austria and Hungary; much of that land had belonged to Charlemagne's empire, but now the Moravians were frequently at war with Charlemagne's descendants in Germany. The Catholic Church took over after Cyril and Methodius left, so in the end the ancestors of today's Czechs and Slovaks joined the Western rather than the Eastern Church (890). Around 879 the Croats and the Slovenes also became Catholics, forming a permanent division between them and their Serb cousins. The missionaries from Rome and Constantinople might have done even better if they had cooperated more and competed less. Nevertheless, it was encouraging that both churches were on the move again. At last Christendom had some gains to offset its huge losses to Islam in the Mediterranean basin.

One reason for the turnaround was that the Vikings were starting to run out of steam, now that they had land in France, Russia, the British Isles and Iceland. But this didn't mean that Christian Europe's troubles were over, because a new group of troublemakers, the Magyars, arrived at that point. Driven from the Ukraine by the Turkic Petchenegs, the Magyars, like the Huns and Avars before them, settled on the plains of Hungary (896), where they found the grasslands needed to feed their horses. The Bulgars had claimed Hungary, but they were a long way from their power base, located between the Danube and Constantinople, so the Magyars had no trouble chasing them out. They also made friends with the German king Arnulf, which gave them an excuse to attack Arnulf's enemy, Great Moravia. Arnulf only wanted them to humble Great Moravia, but the Magyars did better than that; in a series of campaigns that lasted until 907, they destroyed the Moravian kingdom completely, and took the rest of Hungary for themselves. The Czechs replaced Great Moravia with a state called the Duchy of Bohemia, which only contsined the land of the Czechs and was an obedient vassal of Germany from the start, so Germany's Slavic problem was solved. Then the Magyar horsemen began raiding all surrounding countries. They proved to be tougher than the other enemies of Christian Europe; whereas the Vikings usually fought on foot with swords and axes, and the Moors of Spain relied on light cavalry, the Magyars had a heavy cavalry, horsemen covered with chainmail and armed with lances; the knights who fought the nomads must have felt like they were going up against other knights!

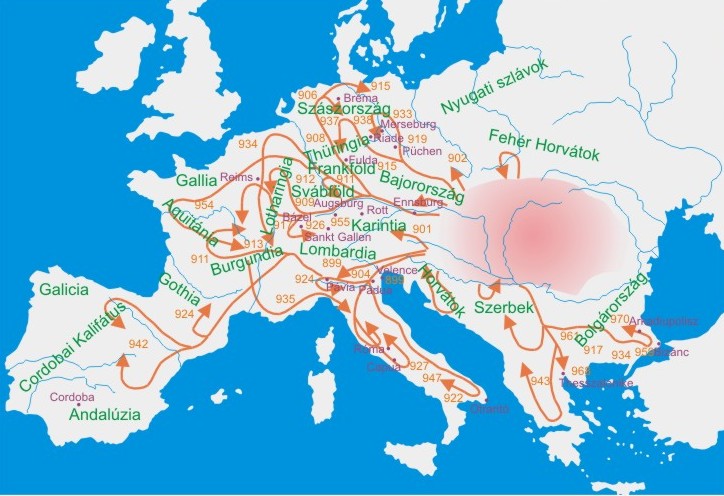

Dates and locations of the Magyar raids. The pink area is the Magyar home base.

There was one more member of the unholy trinity raiding Western Europe. While Magyars attacked from the east and Vikings from the north and west, Moslem fleets resumed their offensive in the Mediterranean. We already mentioned how they threatened to conquer Italy in the ninth century; the early tenth century saw the Moors of Spain take Majorca and Minorca, while the Fatimids of North Africa raided the coast of Italy. Together both of these groups hit Sardinia and Corsica.(32) The boldest pirates set up advance bases in 890, at Garigliano in southern Italy and at Fraxinetum on the French Riviera; from there they could penetrate far into France and Italy. The kingdoms of Christendom were now surrounded by enemies on all sides, and the continent was subjected to the worst raids since the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Burgundy, for example, was based in modern-day Switzerland, a supposedly safe haven from raiders, but in the second quarter of the tenth century the Vikings, Moslems and Magyars all took turns looting it.

After Arnulf, his son Louis the Child (899-911) became king of Germany. The failure of central royal authority to stop raids (from the Vikings and Magyars) meant that the dukes of Germany were on their own, so Germany effectively became six tribal duchies: Saxony, Thuringia, Bavaria, Swabia, Lorraine and Franconia. When Louis the Child died, the Saxons refused to stand for any more feeble Carolingians. Only recently civilized at this point, the Saxon landowners and officials were so determined to keep their political and personal independence, that it made them downright antisocial. The result was that they chose the weakest of their dukes, Conrad of Franconia (911-918), to be their king; with that Charlemagne's conquered subjects became the masters. Conrad was not very successful; he could not assert his royal prerogatives over the unruly dukes, and Lorraine (which included Belgium) defected to France. The next king, Henry I (919-936, also called Henry the Fowler), was also a Saxon, but elected from another family. He recovered Lorraine, defeated rivals in Bavaria and Swabia, stopped the Slavic advance westward by conquering Lusatia (928), and persuaded the Magyars to accept a nine-year truce. He used the time thus gained to build new castles and enlist an army of knights, and succeeded in passing a more secure, better-organized kingdom to his son Otto in 936.

Meanwhile, Magyar raiders hit Germany almost every year; the worst raid passed through Germany, France, Burgundy and followed Italy all the way to the heel before returning to the Danube (937). Some Magyar bands going west did not stop at France but continued into Spain. Not until the German king Otto I trapped and destroyed the main Magyar army (the battle of Lechfeld, 955) was Europe freed from their devastations.

The prestige Otto I gained by this victory made him the new champion of Christendom and helped him in his main work--the re-creation of Charlemagne's empire. In 961 he conquered the kingdom of Italy. The next year Pope John XII revived the title of Holy Roman Emperor for him. France and Burgundy were no longer part of the empire, but on the other hand Otto conquered the Slavs who had sat on Charlemagne's eastern marches. Otto's empire, like Charlemagne's, was a pipe dream, and for the same reason: it had almost no administrative structure. But it was big enough to enjoy a reputation as Europe's main state for the next three centuries.

The pope must have been surprised when he found he could not control the emperor he had crowned. After making the Roman people promise that they would not elect a pope without his or his son's consent, Otto convened a synod which tried Pope John, found him guilty of many crimes, and deposed him. In his place they chose a layman, who in the course of twelve hours was ordained and like Photius of Constantinople, given all the other ecclesiastical promotions needed to become Pope Leo VIII. Leo then died of a stroke one year later, while committing adultery (964).

The elimination of the Saracen pirates took place in the next generation. Their base at Garigliano had already been captured in 916, through a joint action involving Pope John X, the Duke of Spoleto, and the Byzantine fleet of Gaeta. In 972 the pirates kidnaped and held Maiolus, the abbot of the great Burgundian monastery of Cluny. This was too important a person to be ignored. As soon as the monks of Cluny had raised and paid the ransom, a strong force of French knights descended on the Riviera and wiped out Fraxinetum.

As the turn of the millennium arrived, the Church got a pope who was fit for the job. This was Sylvester II (999-1003), the most learned man of his day. Born in central France under the name of Gerbert, he was first educated at the monastery of Aurillac. Then in 967, Count Borrell of Barcelona visited the monastery, and the abbot asked the count to take Gerbert back to Spain with him, so that the youth could study the latest in mathematics. When Gerbert learned all that was available in Barcelona, he crossed the frontier into Moslem territory, where he discovered the great libraries of Cordova, saw the scientific works that the Arabs had translated from China, India, Persia and ancient Greece, and learned Arabic and modern astronomy. Returning to Christendom in 969, he got the attention of both the pope and the German emperor; soon he was tutor to the future emperor Otto II, and ended up as a teacher at the cathedral school of Rheims. There he experimented with what he had learned; he constructed the world's largest abacus, built an organ with a water-powered bellows, invented the pendulum clock and the eight-note scale that most Western music is composed with, and introduced Arabic numerals, which are so much easier to use in math problems than the Roman numerals that European Christians were still using at this time.(33)

Many people refused to believe that anyone could know as much as Gerbert did, and as he rose in the clergy, eventually becoming archbishop of Rheims in 991, stories circulated about him being a magician, or that he had made a deal with the Devil. In 996 he lost his job as archbishop, for declaring that the French king's marriage was illegal. Gerbert fled to Germany, where Emperor Otto III welcomed him and hired him as a teacher and advisor. Otto felt that the quickest way to clean up the Papacy was to make sure that the pope wasn't an Italian (and thus someone without local family connections), so he made Gerbert archbishop of Ravenna in 998, and then one year later, made him the first French pope; he took the name of Sylvester II, because Sylvester I had led the Roman church in Constantine the Great's time. However, the people of Rome didn't care for a foreign pope, and they drove both the emperor and pope out in 1001; Sylvester died shortly after he managed to return, and the Papacy went back to its previous routine.

The late tenth century saw the armies of Christendom join the missionaries in gaining more lands and believers for God. The Slavs in eastern Germany were conquered, rather than converted, as Charlemagne had done with the Saxons earlier, and the recovery of central Spain was also a matter of conversion by sword rather than by word. And like the Western missionaries, the Catholic soldiers did better than their Orthodox counterparts. The Byzantine Empire's expansion under the Macedonian dynasty failed to convert many unbelievers; the emperor's armies either conquered already converted peoples like the Serbs, or uncovered schismatics such as the Armenian Monophysites.

The end of the Carolingian line of kings broke the last political link between the West Frankish (French) and East Frankish (German) kingdoms. The last two Carolingian kings in the west, Lothar IV and his son Louis V ("Louis the Lazy"), were dominated by a powerful French noble, Hugh Capet. In 985 Gerbert of Aurillac wrote to the Archbishop Adalberon that "Lothair is king of France in name alone; Hugh is, however, not in name but in effect and deed." When Louis V died childless in 987, the nobility and clergy got together to elect Hugh Capet king, thus founding the first authentic French dynasty, the Capetians. However, Hugh took over a France that was far less united than the France of today. The only areas in the kingdom that spoke French were the Seine valley and the lands between the Seine and the Loire; in Normandy they spoke French with a Scandinavian accent. North of the Seine valley, the inhabitants spoke the Low German dialects that would one day become Dutch and Flemish. South of the Loire, Aquitaine and Provence spoke their own languages (see Chapter 6, footnote #18), while the people living in the Pyrenees spoke either Basque or Gothic. Burgundy was independent in the east, and so was Brittany in the west. To the linguistic disunity was added political disunity, because of the dukes; Hugh Capet was not really the king of a great nation, but the leader of a coalition of medium-sized states. Indeed, the kings called themselves Rex Francorum ("King of the Franks") for the next three hundred years, as if they were caretakers over part of Charlemagne's empire; Philip the Fair was the first to use the title Roi de France ("King of France"). It was a similar story in Germany, where the Holy Roman emperors lorded over an incredibly unruly bunch of nobles and bishops. In the next three chapters we will see the French kings fight an uphill struggle to unify their country, and the Holy Roman emperors fail to do the same thing in central Europe.

France was not the only modern European nation that appeared in the tenth century. The expulsion of the Danes meant that England was now united under the dynasty that once ruled only Wessex, while the union of Scots and Picts (844), followed by the Strathclyde Welsh joining them (945), created the kingdom of Scotland. The need for a stronger defense against the Vikings also briefly united most of Ireland, when in Brian Boru (975-1014) the Irish found their national hero; he ended the Viking menace by capturing Dublin in 999, only to fall in another battle fifteen years later.(34)

The Vikings themselves began to look civilized in the tenth century. Many of the Danelaw's residents converted to Christianity after they settled down, so as early as 900 it was safe for English priests and monks to return to the churches that had been ravaged before. Of course conversion meant giving up their hellraising lifestyle, so many Vikings did not convert eagerly; usually they converted because Christians refused to trade with pagans or let them marry into their families. As in Anglo-Saxon England, the rulers tended to convert first, and their subjects followed later. Harald Bluetooth was the first Scandinavian king to become a Christian (965), but the next two Danish kings, Sveyn Forkbeard and Harald IV, were pagans, so Christianity would have to be re-introduced to Denmark by Canute the Great (1018-35). Missionaries also had to convert the kings of Norway more than once; Haakon I the Good (934-963) and Olaf Tryggvason (995-1000) both converted(35), but were followed by pagan rulers, so it wasn't until Olaf II Haraldson (1015-28) that Norway became Christian and stayed that way. Sweden converted just before the end of the millennium, under Olaf III Skötkonung (995-1022), and around 1001 the president of Iceland's Althing became a Christian, but because Icelanders loved their freedom, he let them know they could stay pagan for the time being. Most historians stop referring to Scandinavians as "Vikings" after this, saving the term for pagan Scandinavians only.

Poland got its act together in response to the Germans advancing toward it. The name of the country comes from polye, the Slavic word for field, which is appropriate because Poland is mostly flat. The Western Slavs who became the Poles claim a legendary figure named Piast as the founder of their royal family (840 A.D.?), but the first Polish ruler that we know anything about was Mieszko I (960-992). Starting from a territory on the south bank of the Vistula River ("Greater Poland"), with its capital at the town of Kruszwica, Mieszko pushed east as far as Warsaw; in the north he reached the Baltic, founded Gdansk in 980, and began the absorption of Pomerania. Equally important, he converted to Christianity in 966, after marrying a Czech princess named Dubravka, and the rest of the country followed. He defeated a German invasion of Pomerania in 983, but two years later paid homage to the German emperor, on condition that the emperor didn't try to be more than a lord in name only. Mieszko's successor, Boleslav, conquered Silesia in 999, and Cracow in 1000, so at the end of the century Poland had roughly the same lands it has today.

1000 A.D. also saw the final victory of the Catholic Church in central Europe. The Magyars, like the Poles, had held back because they did not want to be under German archbishops (which would have made them part of the Holy Roman Empire). Emperor Otto III agreed that their objection was reasonable, and Pope Sylvester II saw to it that both peoples got archbishops of their own. In 1000 the chief of the Magyars was crowned Stephen I, the first king of Hungary.(36) Russia officially became Orthodox when Vladimir I converted in 988, so now only really remote tribes like the Finns, Prussians and Lithuanians continued to stick up for paganism.(37)

Few centuries in European history started as dismally as the tenth, and few ended so triumphantly. In many history books you will read that tenth-century Christians feared the world would come to an end in the year 1000, and panicked in a sort of Y1K crisis. Actually most people just went about the day-to-day business of survival, simply because literacy was so bad that a lot of them weren't sure what day or even what year it was. What really ended in 1000 was the Dark Ages.

A New Beginning

Although Dark Age Europe may not have been in the same class as Islam or China when it came to civilization, after 1000 Western Europe showed steady economic and cultural growth. This means that at a time when the West looked pretty hopeless, something was happening there that would eventually put Europe ahead of its rivals. What changed to give Europe an advantage?

It started with a shift in geography, caused by Christendom's loss of its southern Mediterranean lands to Islam, and subsequent gains that brought it to the Baltic and the Volga. The result was a general shift north. Christianity had started out as a Mediterranean religion, and had become a purely European creed. Despite its name, the Mediterranean was no longer viewed as the "middle of the Earth"; the Moslem conquests of Sardinia and Sicily moved Rome from the center of the Christian world to the southern fringe of it.

The northward move was into colder, wetter lands, where the sun often does not shine through overcast skies. Up to this point agriculture had mainly been practiced in hot, dry places, often with irrigation, so the techniques developed to get the best yields were ones that were best suited for that sort of climate. And three of the most commonly grown crops -- wheat, barley and grapes -- came originally from the Near East, a place known for having a hot, dry climate. Europeans grew grapes for wine, of course, and before the Dark Ages began, bread had become the "staff of life"; wheat and barley are the main ingredients for that. European farmers faced quite different challenges from Near Eastern farmers, and they took centuries to develop the skills needed to solve them. The really important thing is that during the Dark Ages they experimented and eventually succeeded. For example, early on the farmers learned they could keep the soil fertile longer by crop rotation: they divided a farm into three equal parts, and one of those parts lay fallow each year, with only grass and weeds in it, so that it could regain its strength before crops were planted in it again. It may have looked as though Christendom had the poorest corner of the world, but northern Europe had not been ravaged and misused the way older places like Greece and the Middle East had been; by the end of the Middle Ages, proper land management had turned it into one of the richest places.

The crucial invention was a wheeled plow heavy enough to turn and drain the soil, not just scratch a furrow for seed. We first hear of heavy plows being used in northern Europe in late Roman times. It took the whole Dark Ages to get the design right and in general use. By the year 1000 the European farmer was on top of his job. He couldn't produce as much per acre as a Near Eastern farmer with irrigated fields but, thanks to his plow, he could do more work in a hour. He began to prosper.

This prosperity shows in the other tools that came into use. Water mills save a lot of time when it comes to grinding grain, but mills need millers to run them and millers have to be paid. Only a prosperous farming community can afford to do this. It says something about the rising level of prosperity that by the end of the Dark Ages every village in northwest Europe had a water mill.

Another change for the better is the appearance of the horse as a farm animal. Up until now the horse was mainly a luxury for the nobility, while oxen (and sometimes people) did the plowing. Horses are more expensive because they eat more, but they are also stronger and faster, doing up to three times as much work as oxen. The farmer who could afford horses could work a bigger field, and bring in a bigger harvest. But if you hitch a horse to a typical yoke, it cannot pull the load without choking itself. It took the invention of the horsecollar, to spread the weight of a burden evenly on a horse's shoulders, before the horse could take the ox's place in front of the plow. Finally, a horse needs horseshoes to give its feet a firmer grip on the ground, whether it is carrying a knight or pulling a plow, so the use of more horses stimulated the blacksmith industry as well.