| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of the South Pacific

Chapter 3: Pulled Into the Modern World

1781 to 1914

Part I

| Botany Bay | |

| Mutiny on the Bounty | |

| New Holland Becomes Australia | |

| The Impact of Western Contact | |

| Unrest In the Islands | |

| Kamehameha the Great | |

| Australia Developing | |

| The Last of the Tasmanians |

Part II

| Britain Claims New Zealand | |

| The Tahitian Kingdom | |

| A French Foothold on New Caledonia | |

| The Maori Wars | |

| The Kingdom of Hawaii | |

| There's Gold Down Under . . . | |

| . . . And in New Zealand, Too |

Part III

| Tonga: The Restored Monarchy | |

| Cakobau Unites and Delivers Fiji to Britain | |

| The Unification and Division of Samoa | |

| Taming the Outback | |

Part IV

| Dividing What's Left | |

| Hawaii, USA | |

| America's Imperialist Adventure | |

| Australia: Six Colonies = One Commonwealth | |

| New Zealand Follows a Different Drummer | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Dividing What's Left

The half-century before World War I is sometimes called the “Age of Imperialism.” This was when the world's most advanced nations gobbled up as much territory as possible – because they needed resources, they wanted the glory of an empire, they felt it was their duty to civilize primitive peoples – or all of the above. Most of the competition for colonies took place in Africa and Asia, but there were also moves to grab every island in the Pacific. You can compare this partitioning of the Pacific with the “scramble for Africa” that I covered in the African history series on this site. However, European leaders did not all meet at one time to decide how to divide the Pacific between them, the way they did with Africa (the 1884-85 Congress of Berlin), and because the Pacific did not have as many people and important resources, the overall stakes weren't as high. Finally, because most of the activity in the Pacific took place in the 1880s and 1890s, after many of the borders between the African and Asian colonies had been drawn, you could say the Pacific was an afterthought for the empire-builders. Still, the imperialist behavior was much the same here as it was elsewhere. The six nations that took shares of the South Pacific were the United States, Great Britain, France, Germany, Spain and the Netherlands.

The oldest player in the game, Spain, was only interested in keeping the places it still claimed. Besides the Philippines, this included most of Micronesia (the Mariana, Palau, Caroline and Marshall Islands), though Guam was the only Micronesian island Spain had done anything with. After Spain lost Mexico in 1821, the Pacific islands were reorganized into a single territory, called the Spanish East Indies. However, in Micronesia this did not mean Spain was doing anything different; the Micronesians were affected more by the whalers, missionaries and traders who visited them in the following years.(72) In 1874 Spain announced its claim to Micronesia again, based on three arguments: Spaniards were the first Europeans to go there, the pope had awarded most of the Pacific to Spain in 1494, and Spain had tried unsuccessfully to convert this region to Catholicism.

For the United States, the first motivator to get involved in the Pacific was – believe it or not – bird poop. In the middle of the nineteenth century it was discovered that guano, or bird droppings, not only provided potassium nitrate, one of the ingredients for gunpowder, but also made an excellent fertilizer. A rush to gain control of the world's guano deposits followed, and demand for guano escalated; by 1850, the price of guano had been driven up to $76 a pound, or ¼ the price of gold at that time. Squabbles over the largest source, the desert and offshore islands on South America's Pacific coast, led to a war between Peru and Spain, and another war between Chile, Peru and Bolivia; the “guano wars” are covered in Chapter 4 of the Latin American history series on this site. The US Congress passed the Guano Islands Act in 1856, meaning the United States would claim any islands it found that were uninhabited, but covered with bird poop. In the Pacific, these places were Wake Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Palmyra Atoll, and Howland, Baker and Jarvis Islands.

None of the above islands were occupied until more than forty years after passage of the Guano Islands Act; Wake Island, for instance, only became a US territory after the Spanish-American War, in 1898. Instead, mining operations simply came and collected guano for the rest of the century. This did not always mean profits; on Palmyra the guano could not be dried out because there was too much rain, and with the highest point on Kingman Reef just six feet above sea level, much of the guano was easily washed away, so it was never mined. And because the act's protectionist measures were not enforced, some of the sites were also mined by New Zealand and the Kingdom of Hawaii.(73)

South of the equator, the guano rush led to one more atrocity (as if we haven't covered enough injustices in this chapter!). Being few in number and impoverished, the Easter Islanders were easy prey for anyone who wanted to exploit them. This was demonstrated by the American schooner Nancy; in 1805 she sailed from New London, Connecticut to Easter Island, and took back twenty-two Easter Islanders as slaves. However, the worst slave raids came from Peru, between 1859 and 1862. By this time, Easter Island's population had fallen to 1,500; the Peruvian slavers took away 900, and worked most of them to death digging guano in Peru.(74) 100 lived long enough to be set free later; of these only fifteen saw Easter Island again, and they carried back smallpox, which decimated the population even more. By 1877, only 111 Rapa Nui were left. It wasn't until after missionaries arrived, and after Chile annexed Easter Island in 1888, that life for the islanders began to get better, instead of worse.

The United States made its next move in 1867, by annexing Midway Island. Midway got its name from its location, almost exactly in the center of the North Pacific, and on the opposite side of the world from Greenwich, England. There was a plan to set up a coaling station here, so American ships could avoid the high fees they had to pay if they refueled in Hawaii, and the Pacific Mail Steamship Company started blasting and dredging a path through Midway's coral reef for this purpose. Unfortunately, the United States had bought Alaska from the Russians in the same year that it acquired Midway, and many Americans thought they had been ripped off by the Alaska purchase. Therefore, Congress wasn't in the mood to fund Pacific ventures; the money it provided for the Midway project ran out when the channel was finished, forcing the abandonment of both the project and the island in 1871. After that, the United States concentrated its attention on Hawaii for the next generation.

Germany joined the empire club in the 1870s. By this time the best colonies around the world were already taken. This motivated the Germans in two ways: (1) they would take any territory still available, and (2) they would act aggressively wherever they saw opportunities. We already saw the Germans use their business activity in Samoa to claim most of those islands; at the same time they went for the parts of Micronesia and Melanesia the other empires did not want.

The largest unclaimed territory in the Pacific at this point was eastern New Guinea. Everything about that huge island told outsiders to stay away: the climate, diseases, difficult terrain, isolation, unfriendly natives, and risk all around. That is why the first Dutch outpost in western New Guinea failed, and why they waited until the nineteenth century was nearly over to try again. In 1881 they finally got around to staking their claim; a steamship, the Batavia, sailed from Ternate to the south coast of New Guinea, and at longitude 141o E. the crew planted a sign that showed the Dutch coat of arms and declared this was the border of "Netherlands New Guinea." With the same thoughts in mind, the first successful Dutch outposts were founded in 1898 and 1902, at the points on the northern and southern coasts where the border met the sea.

Even with all the obstacles New Guinea posed, a few folks figured that any landmass that big had to have resources worth exploiting. In the early nineteenth century some British, French and American whalers and traders came to New Guinea, seeking the same commodities that had attracted them to other parts of the Pacific: whales, sandalwood and sea cucumbers. They gave iron and steel tools, calico and fish hooks to the Papuans they met, and the tools fueled a population boom, because they made more efficient farming (meaning larger harvests) possible. Unfortunately the traders also introduced devastating European diseases, and when the natives acquired guns, the result was an explosion of warfare and head-hunting.

On New Guinea's northeast coast, the main activity after 1870 came from two German corporations, Godeffroy und Sohn and Robertson & Hernsheim. They were attracted by the same resource that had attracted Godeffroy to Samoa – coconuts. By contrast, activity on the southeast coast came from individual adventurers, like the handful of prospectors who arrived when gold was discovered near Port Moresby in 1877. Missionaries ready for the big challenge also started coming in the 1870s. The most unusual group to arrive was sent by Charles Marie Bonaventure du Breil, a French nobleman better known as the Marquis de Rays. The marquis wanted to set up a French colony in the islands adjacent to New Guinea, calling the archipelago La Nouvelle France. The government wasn't interested in this, but his wild claims, about a thriving settlement already established and looking for colonists, suckered in enough people to launch an expedition. In 1880 four ships delivered 570 ill-equipped colonists to the southern tip of New Ireland. Unfortunately this island was covered by a malarial jungle, the new colony was poorly supplied, and management of the colony was an outright scandal. 123 colonists quickly died, and most of the rest fled to Australia, New Caledonia, and the Philippines.

All of the different groups mentioned above managed to avoid running into each other until 1882, when Australian labor recruiters wandered to the northeast coast, the same area where the Germans had been getting workers for their Samoan plantations. What alarmed the Germans was that most of the foreigners in southeast New Guinea came from Queensland, a British colony that wanted to establish an empire of its own in New Guinea, now that it realized there was a territory up for grabs, just on the other side of the Torres Strait from Queensland. In 1883 the premier of Queensland called for the annexation of all of eastern New Guinea and the nearby islands; he sent a petition requesting that the British government do this. London refused, but the action got Britain involved in the New Guinea affair. Germany and Britain sent representatives to the negotiating table; after mutual accusations that the opposite side had acted in bad faith, they reached an agreement near the end of 1884, and signed it in April 1885. The southeastern quarter of New Guinea, renamed the Territory of Papua, went to the British; later, in 1906, they would transfer this territory to Australian rule. Germany got the northeastern quarter, which they renamed Kaiser Wilhelm Land, along with the islands to the east like New Britain and New Ireland (henceforth called the Bismarck Archipelago). In addition, Germany purchased the Marshall Islands from Spain, received two thirds of the Solomon Islands,(75) and annexed Nauru (1888).

.png)

How New Guinea looked from 1884 to 1914, with the Dutch in the west, the Germans in the northeast, and the British in the southeast. From Wikimedia Commons.

The Germans thought their successful business activity on Yap would allow them to claim that key Micronesian island as well. This led to an incident in 1885 where two Spanish ships arrived on Yap with the personnel and supplies needed to set up a provincial government, and then four days later, a German gunboat showed up and its crew came ashore, raising a German flag and claiming Yap for Germany. To resolve the dispute, Spain and Germany let Pope Leo XII decide; he ruled that Yap and the Caroline Islands belonged to Spain, but German corporations could continue to do business there. Meanwhile, a second round of Anglo-German negotiations divided most of Micronesia into British and German spheres of influence, with the Gilbert and Ellice Islands in the British sphere, and the Marshall, Caroline and Palau Islands in the German sphere (1886).

France's piece of the pie was the heart of Polynesia. On Tahiti, Queen Pomare IV died in 1877 and was succeeded by her second son, Pomare V. The French figured out he wasn't very interested in his duties as king, so in 1880 they persuaded Pomare V to abdicate. With this move, France added the Tuamotu Archipelago and the eastern Austral Islands to its holding in the Marquesas Islands. In return for giving up his crown, Pomare V got a pension from Paris and was made an officer in two French orders, the Order of the Legion of Honor and the Order of Agricultural Merit. Afterwards, he followed the example of his grandfather, Pomare II, by drinking himself to death in 1891.(76)

The French followed up on the Tahitian annexation by taking the rest of the Society Islands in 1887, and the rest of the Australs between 1889 and 1900.(77) Meanwhile in the southwest Pacific, they tried expanding into the New Hebrides from New Caledonia, only to find the British were expanding into the New Hebrides, too (from Australia). Because there were both British and French citizens on these islands, if either foreign power had simply taken over, it would have forced a large number of Europeans to live under an alien government and set of laws. In 1887 London and Paris agreed to work together, establishing a joint naval commission over the citizens of both nations. Still, this was not a true government; attempts were made to regulate sales in arms and liquor, but any regulations laid down could not be enforced. Moreover, this system could not keep Europeans from abusing the local Melanesians (see the previous reference to "blackbirding").

After the alternatives failed, the two nations set up an extraordinary joint government over the New Hebrides in 1906, in which British and French citizens were under the laws of their homelands, and other foreigners chose which code of laws would apply to them. For example, a lawbreaker sent to jail was likely to receive better treatment in the British prison, but better food in the French prison. This system of two coexisting governments was called the “Condominium” by the authorities and the “Pandemonium” by everyone else, because it solved most of the previous problems and caused confusion at the same time. You could see the confusion on the local roads; British citizens drove by habit on the left side of the roads, while French citizens drove on the right side. However, Melanesians living on the islands were not allowed to become citizens of either power, and those who wanted to travel abroad needed an identity document, signed by both the British and French resident commissioners.

The New Hebrides flag, 1906 to 1980. By Elevatorrailfan - This vector image includes elements that have been taken or adapted from this:

Flag of France.svg., CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons.

When it came to building empires, Great Britain had been in the lead for decades, but was a reluctant participant in the Pacific. The reason was satisfaction; around the world, Great Britain already had everything it wanted. The aggressive imperialists calling for British expansion in the Pacific were not officials in London, but British citizens in Australia and New Zealand. What they ended up taking were archipelagoes in areas already defined as within British spheres of influence, like the Gilbert Islands and Ellice Islands (both in 1892), or small islands and island groups bypassed by the other colonial powers. The latter included Ocean Island near Nauru (1901), and the Pitcairn group (1898-1902). The islands nearest to New Zealand were put under New Zealand's administration, making them colonies of a colony; these included Chatham (already a British colony), the Kermadecs (1887), the Cook Islands (protectorate in 1888, annexed in 1900), and Niue (1900). South of New Zealand, the Auckland and Antipodes Islands went to New Zealand by default; nobody lived there because of the subantarctic climate.

Britain's lack of interest in new colonies/responsibilities overseas also showed in its response when the United States moved to take Hawaii (see the next section). Whereas the British had disputed American and German claims to Samoa, they declined to get involved in Hawaii again, though the Hawaiian monarchs had cultivated good relations with Britain precisely to keep the United States at a safe distance. London realized that in the northeast quarter of the Pacific, all advantages were with the Americans, and they were not going to let their fingers get caught in a closing door.

Hawaii, USA

When we last looked at Hawaii, a native monarch was still the head of state, but a small group of whites, businessmen and the descendants of missionaries, pulled most of the strings. The Hawaiians were quite happy with their monarchy before the Bayonet Constitution took away its power, and Queen Lili'uokalani agreed with them; her goals were to restore the strength of the monarchy and loosen Hawaii's ties to the United States. In January 1893 the queen announced to the Hawaiian legislature that she would soon give them a constitution like the one that had been introduced in 1864. Realizing that she was about to undo the results of the 1887 coup, those whites who favored annexation formed a group called the Committee of Safety, and they conspired to overthrow the monarchy and invite the United States to annex Hawaii. They also had a special trick to play; the US ambassador, John L. Stevens, was on their side, and an American warship, the USS Boston, was conveniently sitting in Honolulu Harbor.

On the day that the Committee of Safety launched its revolt, Stevens, without any authorization from Washington, ordered the 162 marines and naval troops (“bluejackets”) on the Boston to come ashore. Stevens claimed he did it to “protect American lives and property,” but that was not a likely story, since there had been no acts of violence against Americans, and most of the troops set up their camp not where the Americans lived, but right outside 'Iolani Palace. To prevent bloodshed, the queen abdicated, though she made it clear she was giving up under duress. Still, she was optimistic that when Washington found out, the US government would restore her to the throne.

Queen Lili'uokalani's confidence was reasonable, because the 1892 US presidential election had just been completed on the mainland; the American electorate voted President Benjamin Harrison out of office and brought back his predecessor, Grover Cleveland. Whereas the Harrison administration was receptive to the idea of annexation, Cleveland had no interest in imperialist games. He sent James Henderson Blount, a former Georgia congressman and Confederate army officer, to investigate what was going on in Hawaii.

Blount found a resentful native population, and a provisional government made up solely of American immigrants, with Sanford Dole, the mastermind of the 1887 coup, as its president. In response to this, Blount ordered all American flags taken down, and all US troops removed from the streets of Honolulu. When he returned to Washington he reported that “a great wrong had been done to the Hawaiians,” who were “overwhelmingly opposed to annexation.” Cleveland agreed that the Hawaiian monarchy should be restored. The next step was to get Congress to authorize intervention, but all Congress did was recall Stevens and force the commander of the US troops in Hawaii to resign. By this time Blount's report reached Congress, it had been a year since the queen's overthrow; tempers had cooled (except for the queen, of course), and the outside world was coming around to accept Hawaii's new leaders. The provisional government ignored Cleveland's order to reinstate the queen, and instead declared Hawaii a republic in July 1894. Even Cleveland recognized the republic, when he realized that opposition to it wasn't going anywhere.

The provisional government had expected annexation would soon follow the end of the monarchy. Instead, like the founders of Texas in 1836, they would have to manage an independent state for a few years, while Washington made up its mind.(78) In January 1895 there was an attempt by some 200 monarchists to stage a counter-coup and restore the monarchy. The provisional government found out about this and nipped the revolt in the bud; the plotters and their troops were chased out of Honolulu, captured, tried and imprisoned. Of course Queen Lili'uokalani supported what the monarchists were doing; she denied involvement in the plot, but national guardsmen found enough weapons and ammunition in her palace to make it look like she was an accomplice. The queen was put under house arrest (meaning she couldn't leave the palace), tried on charges of treason, found guilty, and sentenced to five years of hard labor and a fine of $5,000. However, putting the queen on trial, and the humiliations she endured afterwards, were so unpopular that the sentences were never carried out, and she received a full pardon by the end of 1896.

In Washington, the question of what to do about Hawaii was deadlocked, between a Republican Congress and a Democratic president, so nothing happened until Cleveland's term in office ended in 1897. The next president, William McKinley, was a Republican, and both he and Congress saw the strategic importance of the Hawaiian Islands for any naval activity in the Pacific, especially after the Spanish-American War began in early 1898 (see the next section). Under these conditions, the questions regarding Hawaii's annexation were resolved, the annexation bill was passed, McKinley signed it into law, and on August 12, 1898, Hawaiian sovereignty was formally transferred.(79) Henceforth Hawaii will be part of the US, joining Florida as one of America's vacation lands, and becoming a state in 1959.

America's Imperialist Adventure

The United States was more eager to have an overseas empire at the end of the nineteenth century, than it was at any time before or since. Unlike Europeans, Americans did not need the resources an empire could give them; the US mainland was already blessed abundantly with good land and mineral wealth. Nor were they motivated by a desire for glory, the way Europeans often were when they conquered parts of the non-European world. What motivated Americans the most was a desire unique to the modern era, the idea that primitive peoples needed to be civilized, and the United States, with its highly successful economic and political system, was the best nation to do it. With much of the world already under European rule, Americans saw two opportunities available: they could increase their influence over Latin America, or they could take over islands in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Chapter 5 of the Latin American history on this site covers how Americans did the former, while the Spanish-American War gave them a chance to do the latter.

At first the Americans were not interested in Spain's Pacific assets; they were watching how Spain was brutally suppressing an independence movement on Cuba, the most important island it still controlled in the western hemisphere. In early 1898 an American battleship, the USS Maine, made an ambiguous “courtesy call” (nobody had invited the Americans to come to Cuba), and it suddenly blew up in Havana Harbor. Nowadays we believe the Maine suffered an accidental engine room explosion, but the imperialist faction in the United States argued that Spain did it, and convinced enough people to get a declaration of war issued against Spain. While the main theater of the Spanish-American War was in the Caribbean, where US ships and troops conquered Cuba and Puerto Rico, another US squadron traveled across the Pacific, captured Guam without a battle, and went on to the Philippines, where it demolished Spain's Asiatic fleet in Manila Bay. Ten weeks after the fighting started, Spain surrendered; the oldest European empire to hold islands in the Pacific was also the first empire to go. Because the war had been quick and US casualties were minimal, it couldn't have gone better for the Americans.

Except in the Philippines. Like the Cubans, the Filipinos had a nationalist movement, and when the Americans established themselves in Manila, the nationalists withdrew to the jungle and waged a guerrilla war that lasted for years.(80) That long, dirty war caused Americans to think that they didn't want to play the imperialist game after all, if the main rule was “meet exotic people and kill them.” They kept Guam because it was just as useful for American ships going to and from the Philippines as it had been for Spain, but the rest of Spanish Micronesia did not interest them. Seeing an opportunity to gain more islands for its empire, Germany signed a treaty in 1899 that bought the Caroline, Palau and Northern Mariana Islands for 17 million Deutsche Marks (25 million Spanish pesetas, or roughly $4 million US dollars), greatly enlarging the German part of the Pacific. The United States limited its gains after this to uninhabited islands, in order to build a chain of naval bases between the Philippine and Hawaiian Islands; for this purpose they occupied Wake Island, and re-occupied Midway. Hawaii was formally organized as a US territory in 1900, and two guano-rich atolls in the central Pacific, Johnston and Palmyra Islands, were added to that territory as well.

Australia: Six Colonies = One Commonwealth

Australia may have grown up as six British colonies (New South Wales, Tasmania, Western Australia, South Australia, Victoria and Queensland), but in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the idea of a federation was promoted; if Australia was ready to declare its independence, it should do it as one country, not six. There were two reasons why this became popular. The first was the fact that it was taking so long to recover from the 1890 depression. The next time an economic crisis hit, recovery would be easier if each colony could count on help from the others. The second reason was concern over potential threats from overseas. With the French in the New Hebrides, and the Germans in New Guinea, those European powers were getting closer. Either of them might invade Australia in a future war, and newspapers spread a rumor that Russia was also considering an invasion of Australia, though the Russians were nowhere near the South Pacific. Furthermore, the last British soldiers stationed in Australia had gone home in 1870, the same year they were withdrawn from New Zealand. Because the continent was at peace, colonial forces were small, and the colonies would have to pool their military resources in order to defend themselves from hostile outsiders. Finally, four British colonies in North America had successfully merged to form Canada in 1867, and that gave Australians an example to follow.

Henry Parkes (1815-96), a five-time premier of New South Wales, is credited with starting the movement toward federation in the late 1880s; although he wasn't the first to call for it, he was its strongest supporter. But as you might expect, not everyone thought federation was a good idea. Those living in the outback supported it because they felt a central government would act as a check on the power of the big cities. The middle class were for it because it would keep the unions from becoming too strong, and get rid of the tariffs between the colonies. And the unions and politicians tended to be against it for the same reasons. A New South Wales politician, for instance, noted his colony was the only one favoring free trade, and claimed that federation would be like forcing a sober man to live with five drunkards. The more people talked about federation, the more it divided them, until it became impossible for an Australian to be neutral on the issue.

By 1895, the colonial premiers had come to believe that federation was inevitable, and they decided to have representatives from each colony get together and draw up a federal constitution. Four constitutional conventions were held in 1897 and 1898. They decided that because dominion status was working well for Canada, they would set up the same kind of government for Australia. Economic and military ties with the United Kingdom would remain; Australians had fought on Britain's side in two recent African wars (the Mahdist Revolt and the Boer War), and they felt that if they continued to support Britain in future conflicts, the mother country would send troops to help them if Australia ever came under attack. Like Canada, the top two officials in the government would be the king or queen of England, and an appointed governor-general. However, of the three branches of government, the legislative branch would be the most important, and its Parliament would have two houses: a Senate with six members from each colony (soon to be renamed states), and a House of Representatives where the number of members depended on the population of each state, and was elected by universal male suffrage.

When the first national referendum was held on the constitution in 1898, only three colonies (South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria) approved it. This caused the premiers to add amendments to the constitution, to win the support of the other three colonies. Then a second round of referendums was held in 1899, and here New South Wales and Queensland joined the three colonies that had voted "Yes" already.

The main holdout was Western Australia and its premier, Sir John Forrest, the former explorer. He noted that because isolation, Aboriginal resistance and the deserts had hindered the development of his colony, Western Australia was about fifty years behind the colonies in the east. And while the discovery of gold in Western Australia helped, the goldfields were near Kalgoorlie, a location so remote that an infrastructure would be required to support the new mining industry.(81) What the mines needed the most were an excellent harbor, a railroad and a reliable water supply. Rather than trust private contractors to do the job, Forrest made each of these items a government project, and hired a brilliant engineer, the Irish-born Charles Yelverton O'Connor. "C.Y." had limestone and sand dredged from the mouth of the Swan River to create Fremantle Harbor, while others were saying the project wasn't worth what it would cost. For the water supply, he built one of the world's longest pipelines, running 330 miles from Perth to Kalgoorlie, with eight pumping stations capable of moving 5 million gallons of water every day. Nevertheless, O'Connor's opponents in the local Parliament accused him of corruption and various misdemeanors, and the press mercilessly published libelous stories about him. In 1902 O'Connor couldn't take it anymore, so he rode his horse into the waters off a Fremantle beach and shot himself. However, the fact that all of his projects are still working, more than a hundred years after their completion, shows that he had been right all along. Today in Western Australia, several places are named after O'Connor and you can see two statues of him, one of which marks the spot where he committed suicide.

A delegation took the draft constitution to London in 1900. Parliament passed it, and though Britsh Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain had some misgivings, he reached an agreement with the Australian delegates, and they are said to have joined hands and danced around the room at that point. Thus, on July 9, 1900, the constitution became the supreme law code of the colonies that had approved it. In Perth, Forrest finally accepted the federation idea; not only did he feel he had gotten the best possible terms for Western Australia put into the constitution, but the constitution's passage meant the other colonies were going to form an Australian nation whether the west was with them or not. Thus, on July 31 another referendum was held in Western Australia, and this time it passed by a 2-1 margin. Queen Victoria gave her approval to the constitution in September, and on the first day of 1901, the Commonwealth of Australia was born. Appropriately, the leading Federationist in New South Wales, Sir Edmund Barton, became the nation's first prime minister.

Technically this date (01/01/1901) marks when Australia became independent, and the continent's 3.8 million citizens were so eager to celebrate, that many parties began the night before. Besides setting off fireworks, the residents of the cities used bells, whistle, gongs, accordions, rattles, and metal pots – anything that made noise – to mark the event. Because Australia joined the British Commonwealth of Nations, meaning it was still part of the British Empire, Britain still had control over military and foreign affairs, but when it came to domestic matters, Australians were now in charge of their lives.

The thirteen years between independence and World War I were good years for the economy, and it grew very nicely. This attracted large numbers of immigrants, which peaked at 200,000 between 1911 and 1913. Australians became concerned that they might lose their hard-won identity in the flood of newcomers, especially if the immigrants were not white. There were also fears that if Asians and Pacific islanders were allowed in, they would compete unfairly with white workers, because they were willing to work for lower wages.(82) Consequently, the first item on the agenda for the new Australian Parliament was passing legislation known as the White Australia Policy, starting with the Immigration Restriction Act (1901), which required all nonwhite immigrants to pass a dictation test, proving they could write in a European language. The British government protested, because it felt that nonwhite citizens of the British Empire should be allowed to travel freely between its territories, including Australia; so did the sugar growers of Queensland, with their black workers from Melanesia; Parliament ignored both. This official racism stayed on the law books for the next seventy years. The White Australia Policy is gone now, but you can still see its effect on demographics; the current Australian population is 92 percent white.

Next came a bit of unfinished business from the constitutional conventions – where to put the nation's capital. For the time being, Parliament met in Melbourne, but because of the rivalry between Melbourne and Sydney, everyone agreed that neither city could have the honor of hosting the capital permanently. The constitution stated that a federal district for the capital, like the District of Columbia in the United States, would be created in New South Wales, and that it must be at least 100 miles from Sydney.(83) Surveyors went looking for a suitable spot, and selected it in 1908. An American, Walter Burley Griffin, drew up the plans for the future city, and construction on Canberra began in 1913.

Because of the fears mentioned above concerning immigrants, the government also decided it had to do something about the grossly underpopulated north-central region. This land had been under South Australian rule since 1863, and it seemed dumb to keep on calling a northern territory “South Australia.” Worse, outside of Palmerston/Darwin (see footnote #67), only Aborigines wanted to live there, meaning that if a foreign power invaded Australia, it wouldn't have much trouble occupying the north. Therefore in the name of security, the federal government separated the territory from South Australia. On January 1, 1911, the territory was put under Commonwealth control, and simply renamed the “Northern Territory.” As Alfred Deakin, the nation's first attorney general and second prime minister, explained it: "To me the question has been not so much commercial as national, first, second, third and last. Either we must accomplish the peopling of the northern territory or submit to its transfer to some other nation."

Though the name “Northern Territory” describes the location, you have to admit it's not the best name for a place. In the late nineteenth century it was called Alexandra Land, but that name never caught on. Immediately after the Northern Territory was declared, other names were suggested. The most popular new name was “Kingsland,” because England was now ruled by King George V and the territory was next to Queensland, get it? Other names proposed were “Centralia” and “Territoria.” The government never accepted any of these names, though, nor did it succeed in filling the territory with white settlers. The continued low population of the Northern Territory is probably the reason why no one since then has tried to rename it. Even today, the Northern Territory is not considered a state because its population is under a quarter million, less than half the population of the smallest state, Tasmania.

Last but not least, there was a program in the first decade of the twentieth century, to create a model society for those allowed to live in Australia, called the “Australian settlement.” Besides the White Australia Policy, this included the following:

- Women's suffrage (passed in 1902, see also the next section).

- Coalition governments. In order to get things done, coalitions had to be formed in Parliament, because no party held a majority of the seats until the Labor Party won the 1910 elections.(84)

- Protective tariffs on manufactured goods from other countries, instead of tariffs on goods from other states.

- The establishment of the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, to settle industrial disputes without resorting to lock-outs and strikes.

- Early social welfare policies, including old-age pensions and a “living wage” that could support a worker with a wife and three children.

New Zealand Follows a Different Drummer

After the New Zealand gold rushes, the next important leader was Julius Vogel, a Jewish immigrant from London who had only arrived in 1861. From 1869 to 1876, he was either the colonial treasurer or prime minister. In 1870 New Zealand suffered an economic slump, and Vogel proposed a major development program. With large sums of borrowed money, he bought more Maori land and financed the building of railroads,(85) roads, bridges, port facilities and telegraph lines. And to top it all off, the 1870s were a time for building schools. A network of Native Schools replaced the mission schools for the Māori; the Universities of Otago and New Zealand were founded; the 1877 Education Act established a colony-wide public school system.

Vogel's reasoning was that if you build the infrastructure, people will come, and if enough people come, another economic boom would follow. They did come, all right; by 1880 New Zealand's population was approaching half a million. The newcomers tended to see themselves not as residents of whichever province they settled in, but simply as New Zealanders. Vogel agreed with them, and abolished the previously existing provinces in 1876. Transportation and communication had improved to the point that provincial governments were no longer needed anyway, and in the New Zealand Vogel was building, there would be no place for the provincial attitudes or pork-barrel politics that provincial governments generated.

Vogel may have also believed that a growing population would diversify the economy, making it less dependent on gold and wool. Well, the economy did diversify, but it was because of technology, not government spending. In 1882 the Dunedin, a clipper ship with a refrigerated cargo hold, successfully transported a cargo of frozen meat and butter from New Zealand to England, and after paying all expenses, made a profit of £4,700 from the voyage. As with Argentina, the invention of refrigeration revolutionized New Zealand's economy; now its ranchers could export not just wool, but also meat and dairy products. Quite a few forests were cut down during the next few years, as New Zealand became a farm for the mother country.

Unfortunately for Vogel, the boom he was investing for didn't come until the mid-1890s, long after he had retired. First, another bust came in 1879. The failure of a bank in Scotland caused other British banks to tighten up on their lending practices, meaning higher interest rates on New Zealand's current debt, at a time when wool prices were down. Many blamed Vogel for making New Zealand vulnerable to a credit shortage, due to his heavy borrowing. Nowadays this slump is called the Long Depression, because it lasted all through the 1880s. Prices for crops fell, unemployment rose, and there were reports of factories using “sweated” (overworked and underpaid) labor. A wave of emigration followed the previous wave of immigration, with most of those needing jobs moving to Australia. Near the end of the depression, in 1890, New Zealand saw its first big strikes because port workers walked off the job, in support of Australian strikers.

The 1890 election was important for two reasons. First, the practice of “plural voting” was ended, where a man could vote in every district where he owned property. Second, New Zealand's first political party, the Liberal Party, had just been founded, and because it faced no organized opposition, it won a majority of the seats, and held that majority for the next twenty-two years. The Liberal platform called for supporting the rights of the working class and small farmers, creating more small farmers by making it easier for them to obtain land, and welfare-state legislation like old age pensions and developing a system to peacefully settle industrial disputes. From the party's point of view, New Zealand was both a “workingman's paradise” and the world's social laboratory.

New Zealand does not get credit for being a pioneer of women's rights, but it was the first nation in modern times to give women the right to vote. What's more, it happened in 1893, while New Zealand was still a colony. The colony of South Australia did likewise in 1894 (South Australia had to maintain its progressive reputation), but every other nation, including the rest of Australia, waited until after the twentieth century began, to grant women's suffrage.

Julius Vogel may have started the women's suffrage movement in his country, because in 1889 he wrote New Zealand's first science-fiction novel, Anno Domini 2000, or, Woman's Destiny, which described a future British Empire where women not only vote, but hold all top positions in the government. After that, the struggle for the right to vote reads a lot like the history of the movement in the United States: both had suffragettes(86) who campaigned for years to win the minds of the public and politicians, and in both countries the opposition included the liquor industry, because women also favored temperance laws that would hurt their business.

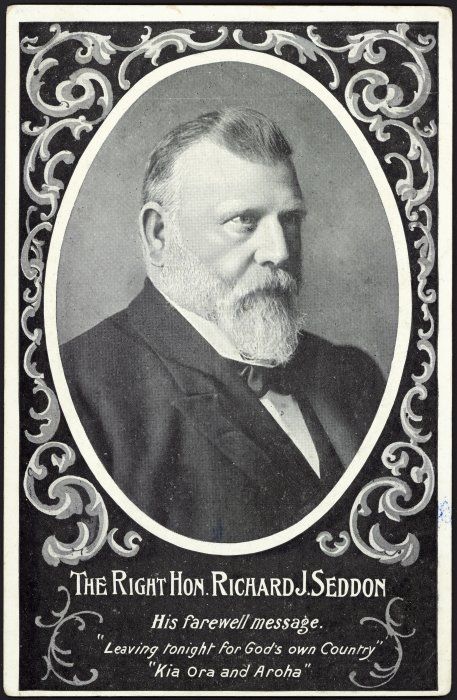

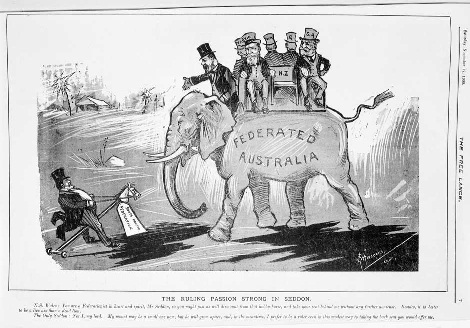

So why did the Kiwi suffragettes win the struggle twenty-seven years before their US counterparts did? Because of petty bickering among those who opposed it. The Liberal Party introduced the suffrage bill to Parliament twice, in 1891 and 1892; though it passed in the lower house each time, opponents in the upper house managed to kill the bill by adding amendments to it that other upper house members could not support. John Ballance, the Liberal Party's founder and the current prime minister, was pro-suffrage, but in April 1893 he died and Richard Seddon took his place. Seddon was a friend of the liquor industry, so naturally he was against giving the vote to women.(87) Because of his autocratic style of leadership, Seddon had another name – King Dick. Go ahead and look it up (the Encyclopedia of New Zealand is a good place to start); King Dick sounds like a naughty nickname a modern writer might give to Seddon, but even during his lifetime he was called that. And when you hear what he did, I think you will agree that the King Dick nickname fits him even better today.

Anyway, petitions sent to Parliament got another suffrage bill introduced, and the lower house passed it again, but there wasn't much hope it would prevail in the upper house, because of King Dick. Still, when Seddon checked on how upper house members felt about the bill, the result was a tie of 19-19. To keep the bill from passing and becoming law, he would have to change one “yes” vote to a “no” vote. Accordingly, King Dick sent an upper house councilor a telegram that ordered him to change his vote. The councilor did, presumably because King Dick would have made life in Parliament very uncomfortable for him if he didn't. However, word of Seddon's trick got out, and it offended two other upper house members who were against the suffrage bill. These two fellows did not belong to the Liberal Party, and thus were immune to King Dick's bullying. They also did not feel too strongly about the bill, having opposed it on a technicality, so to embarrass the prime minister, they changed their votes from “no” to “yes,” and the bill passed by a narrow 20-18 margin.

Afterwards, Seddon tried to take credit for women's suffrage, because his party had supported it from the start, even if he hadn't. And he didn't act like a reactionary when other bills came to Parliament, especially the Old-Age Pensions Act of 1898. Thus, he has gone down in history both as a reformer and as one of New Zealand's better leaders. Finally, Seddon won five elections in a row, something no other prime minister has done, and he held the premiership until his death in 1906, one year before dominion status arrived, so he barely missed becoming the George Washington of New Zealand.

Richard Seddon / King Dick (depending on your point of view) in 1906. From Wikimedia Commons.

When the Australian colonies began talking about a federation, New Zealand considered joining them. They went so far as to send a delegation to the 1891 National Australia Convention in Sydney. But after that, New Zealanders lost interest in becoming part of Australia. Many feared losing their distinctive identity and character; others did not want to join because they believed New Zealanders represented a better “type of Britisher.” As a result, when Australians took the next step, by writing a constitution for their federation, New Zealand did not attend the constitutional conventions. In 1902 New Zealand showed it was not going with Australia by adopting the flag it has used ever since, which looks like the Australian flag but has red stars instead of white ones.(88)

New South Wales Premier: You are a Federationist in heart and spirit, Mr. Seddon, so you might just as well dismount from that hobby-horse, and take your seat behind me without any further nonsense. Besides, it is better to be a live ass than a dead lion.

The Only Seddon: Not I, my lord. My mount may be a small one now, but he will grow apace, and, in the meantime, I prefer to be a ruler even in this modest way to taking the back seat you would offer me.

Seddon's successor, Joseph Ward, decided that if New Zealand had come of age and could not be considered a colony anymore, the best option was to call itself a “dominion,” like Canada. The idea here was that as a dominion, New Zealand could join the British Commonwealth of Nations, and be considered equal to Canada and Australia; this would not happen if New Zealand was under Australian rule. He got Parliament to pass a resolution approving dominion status, and Britain agreed. On September 26, 1907, the United Kingdom declared New Zealand and Newfoundland “Dominions” within the British Empire (Newfoundland had not joined Canada yet). That date was called Dominion Day, and a Wellington newspaper that published its first edition on that day was named the Dominion.

The foreign point of view was that New Zealand was now an independent nation, but to the Kiwis, whose population was now 967,000, nothing had really changed at all. Because they had been just one colony previously, and not six like Australia, they did not have to learn to get along with each other. Their country still had the same ties with Britain that it had before 1907; the British Isles were still the largest source of immigrants; New Zealand soldiers had recently fought on Britain's side in the Boer War, and expected to fight again when Britain called for them. There was celebration on the first Dominion Day, but it was polite and subdued, compared with Australia's boisterous celebration in 1901. Even Dominion Day was only celebrated for a few years; ordinary people couldn't get excited about the day, and after the Liberal Party fell from power, none of the governments which came after it wanted to make Dominion Day a government holiday.

Since Seddon had ruled so long and done so much, his shoes were hard to fill, and Joseph Ward wasn't up to it. Although the Liberals won the 1908 elections under his leadership, he was considered a windbag, too concerned with his own appearance to be a convincing friend of the working class. And the voters now decided they were tired of the Liberals, so changing the party's most visible face wasn't enough to change their minds. The December 1911 election created a mixup; the Liberals got more votes than William Massey's Reform Party, which had just formed in 1909, but the Reform Party won more seats; however, neither party had 41 seats, the required minimum to rule. The Liberals were able to hold onto power for a few more months by getting the speaker of the lower house to vote with them, and Ward stepped down in March 1912, but the party failed to win a vote of confidence after that, so Massey put together the next government, in July 1912. He would rule until his death in 1925, making his administration the second longest-lived after Seddon's, and the Reform Party would rule until 1928, while the Liberal Party faded away.

This is the End of Chapter 3.

FOOTNOTES

72. One of the Caroline Islands, Yap, has become famous for its “stone money,” probably the most unusual currency ever created anywhere. Called Rai in Yapese, these are stone disks with a hole in the middle, resembling stone wheels; in size they range from 3 inches to 12 feet across. Amazingly, the stone used to make these “coins” is not available on Yap, so the locals sail to Palau, almost three hundred miles to the west, and carve the money there. The only way they could bring the money back was to lay it on rafts, and tow the rafts behind canoes. The money was considered valuable because of the effort and risk involved with getting it, and because of the limited supply of Rai, one did not have to worry about inflation/deflation changing its value. A final hazard was that the Yapese could not obtain the needed stone if relations with the Palauans were not good.

The rules for stone money economics were perfected in the nineteenth century, which is why I am discussing them in this chapter. Understandably, this kind of money is only used for major purchases, like a bride's dowry. Because it can take a work crew of more than a hundred men to move the largest stone money, once a Rai is put in a suitable place for display, it stays there. When stone money is “spent,” a ceremony is held to signify that the money has changed hands, from one owner to another. Hmmm, that sounds a little like how our banks work, doesn't it?

Because the stone doesn't move when it changes owners, it does not even have to be on Yap to be considered legal tender. The oral tradition tells how more than a hundred years ago, a work crew was bringing a stone coin to Yap, when a storm struck. The raft carrying the stone was tipped and the stone was lost, but the crew survived. When they made it to Yap, they told what happened, and everyone decided that the stone money was still good, even on the bottom of the ocean. So the oral tradition of Yap has kept track of who owned that stone coin in the past, and who owns it today, though nobody has seen it for more than a century.

And while we're on the subject, a 1990 episode of Saturday Night Live began with Donald Trump (played by Phil Hartman) finding a modern use for Yap currency.

73. The Guano Islands Act led to the creation of a national park in our own time. In January 2009, two weeks before the end of his presidency, George W. Bush followed up on the establishment of the the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (see Chapter 1), by creating the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument. This claimed the waters around the seven islands claimed by the Guano Islands Act, extending out 12 to 50 nautical miles from each. Because the US government has legal control over the waters up to 200 miles from any US territory, in September 2014 President Barack Obama extended the borders of the park to the 200-mile limit, enlarging it to 490,000 square miles and making it the world's largest wildlife sanctuary.

"But wait, there's more!", as the famous salesman Billy Mays used to say. Even now Obama didn't think this was enough; in August 2016, with a stroke of a pen, he added 400,000 square miles to Papahānaumokuākea, giving that park a total area of 582,578 square miles. To put this in perspective, Papahānaumokuākea is now more than three and a half times the size of California, ten times the size of Iowa, and 105 times the size of Connecticut. However, this also means commercial fishing and drilling is no longer permitted in 60 percent of the waters around Hawaii. Environmentalists and some scientists said this expansion was necessary to protect marine species that had been overfished, but fisherman warned this is also likely to increase seafood prices and imports; keep in mind that the cost of living in Hawaii is already notoriously high.

74. Unfortunately, many of those removed were high-ranking islanders, and they died before they could pass on their special knowledge and skills to the next generation. This included everyone who knew how to read Rongorongo, the only form of writing ever created by Polynesians. Rongorongo has been described as looking like the picture writing of the Indus Valley civilization or Neo-Hittite hieroglyphics; the only surviving examples of the script are on twenty-six boards or “tablets.” The first outsider to see Rongorongo was a French priest, in 1864; we don't know how long the islanders had it before then, and some have suggested they invented the script after a shipload of Spaniards came by in 1770, and showed them an impressive-looking document that claimed Spain owned the island. Attempts to decipher the boards have failed to this point, so what they say is another Easter Island mystery; our best guess is that they are the words to songs or prayers. What we have figured out is that the reader is supposed to start in the bottom-left corner and read it Boustrophedon style; he follows the first line from left to right, then turns the board upside down and reads the second line from left to right (really right to left), then turns the board rightside up and reads the third line from left to right, and so on. Still, we can't be sure if the characters are a true pictographic script, or some kind of mnemonic memory aid.

75. Britain established a protectorate over the southern Solomons in 1893. In 1899 the central Solomons were transferred from Germany to Britain, in return for British recognition of German rule over Western Samoa.

76. In several countries that used to have kings and queens, there is somebody descended from the former royal family, a “man who would be king” if the monarchy was restored. With Tahiti the self-proclaimed heir is a descendant of Pomare V. But while Polynesia has been under French rule for more than a century, no nationalist movement has sprung up here yet, and France doesn't take the claim seriously.

77. Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), the Post-impressionist French artist, first lived on Tahiti from 1891 to 1893. Many of his masterpieces were painted here, but when he returned to France, his “primitivist” style was not popular, so he only sold eleven of the forty works he put on display. His second sojourn on Tahiti (1895-1901) was even less successful, prompting him to move to the Marquesas Islands, where he died poor and alone. As with some other artists and entertainers you have probably heard of, it was after Gauguin's death when his work caught on and he became famous. Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse were influenced by his paintings and sculptures, and one of his paintings, Maternité II, sold for $39.2 million in 2004.

78. One challenge they had to deal with was rebellious lepers. Back in 1865 a leper colony had been established on the island of Molokai, and the monarchy decreed at the same time that everyone in Hawaii with leprosy would have to move to that colony. Father Damien Joseph de Veuster, the priest who ran the leper colony for most of its early years, is regarded as a saint by present-day Hawaiians, for all that he did to improve the lives of these forsaken people.

The colony was placed on a peninsula that was only accessible by mule trail. The peninsula was proclaimed Kalawao County, a separate county from the rest of Molokai, in 1905, and it is run not by the state of Hawaii, but by the Hawaii Department of Health. In 1969 the quarantine policy forcing lepers to stay there was lifted, since the disease had become treatable and non-contagious. However, not all patients left, and the state promised that they could remain for the rest of their lives, if they chose to do so. Over the years the population of Kalawao County has declined accordingly, from a peak of 1,177 in 1900, to just 90 in the latest census (2010).

Anyway, in July 1893 there was a brief uprising on Kauai, called the Leper War. A deputy sheriff tried to expel an isolated leper colony on Kauai, moving its patients to the colony on Molokai, and the lepers resisted by killing the sheriff. The provisional government declared martial law and sent troops to Kauai. Over the course of twelve days, they captured and deported twenty-seven lepers; the rest managed to avoid capture by hiding until the authorities stopped looking for them, but the Kauai colony was no more.

79. "Hawaii is ours. As I look back upon the first steps in this miserable business and as I contemplate the means used to complete the outrage I am ashamed of the whole affair." -- Former President Grover Cleveland, when he heard that the annexation was finished. Likewise, Queen Lili'uokalani predicted that native Hawaiians would be treated as badly as Native Americans on the mainland.

80. This is one of the little-known conflicts in American history, called the Philippine Insurrection or the Philippine-American War. In most of the archipelago it lasted from 1899 to 1902; the Moslem area in the southwest held out until 1915. If it had lasted any longer, the conflict could have become part of World War I, and General John “Blackjack” Pershing probably would have been stuck on Mindanao, instead of leading the US Army in France.

81. Although the politicians did not say it at the time, the development of infrastructure would also support Western Australia's population, which boomed because of the gold rushes. In the 1890s, it grew from 50,000 to 200,000.

82. “Our chief plank is, of course, a White Australia. There's no compromise about that. The industrious coloured brother has to go – and remain away!” – The Labor Party Platform, quoted by The Bulletin, February 16, 1901.

83. In the early twentieth century, the district chosen for the capital was called the Federal Capital Territory. Today it is the Australian Capital Territory, or ACT.

84. Australia started out with three political parties: the Protectionist Liberals, the Free Trade Liberals, and the Labor Party (ALP).

85. Before 1870, New Zealand only had 47 miles of railroad tracks. By 1880, this had increased to 1,250 miles.

86. The Kiwi equivalent of Susan B. Anthony was Kate Sheppard. You can read her biography here.

87. If the liquor industry had known the future, they probably wouldn't have been concerned about women voting. The issue of prohibition was put to a national referendum in 1911, and it received a majority of the votes cast, but it needed a 60% supermajority to become law, and that did not happen. Three more referendums were held in the 1920s, and they also failed to pass. Maybe New Zealanders noticed that prohibition was not working in the United States. Still, those who weren't friends of the liquor industry could make it difficult to serve drinks. Until 1967, there was a law on the books requiring pubs to close at 6 PM.

88. Fiji, like New Zealand, was invited to join the Australian Federation, but declined to do so. Considering how little Australia and Fiji have in common, I don't know where anyone got the idea that a union between those two places would work!

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of the South Pacific

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|