| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of the South Pacific

Chapter 3: Pulled Into the Modern World

1781 to 1914

Part I

Part II

| Britain Claims New Zealand | |

| The Tahitian Kingdom | |

| A French Foothold on New Caledonia | |

| The Maori Wars | |

| The Kingdom of Hawaii | |

| There's Gold Down Under . . . | |

| . . . And in New Zealand, Too |

Part III

| Tonga: The Restored Monarchy | |

| Cakobau Unites and Delivers Fiji to Britain | |

| The Unification and Division of Samoa | |

| Taming the Outback | |

Part IV

| Dividing What's Left | |

| Hawaii, USA | |

| America's Imperialist Adventure | |

| Australia: Six Colonies = One Commonwealth | |

| New Zealand Follows a Different Drummer |

Botany Bay

We noted in the previous chapter that the third expedition of Captain James Cook took place at the same time as the American Revolution. When the American Patriots won their freedom, Britain lost the land and resources of what were then its most valuable colonies. However, the part of the British system that suffered the most was one you are not likely to think of first. The government had never brought in much tax revenue from the colonies, and British merchants soon found new customers to replace the ones they had lost; it was the British penal system that was thrown into a crisis by American independence.

For nearly a century and a half the courts had been populating the colonies, especially Maryland and Virginia, by sending as many as a thousand convicted felons across the Atlantic every year, where they would typically stay after their sentences had ended – unless they could buy passage on a ship returning to England. Now the prisons were overcrowded because they could no longer get rid of these unwanted people. Most of them had not committed crimes worthy of a death sentence, nor would the public stand for it if they were just set free. Some prisoners were locked up on decommissioned warships anchored in harbors; that was supposed to be a temporary solution, but now the naval “hulks” were overcrowded, too.

The only solution was to find another dumping ground and exile the convicts there. Britain still had Canada, but with its colder climate and smaller communities, it could only take a few exiles before they disrupted the local economy. Since the rest of the Americas had already been colonized (mostly by Spain and Portugal), the new penal colony would have to be in Africa, a Caribbean island, or somewhere on the other side of the world from Europe. Africa and the Caribbean were ruled out because their climates were unhealthy for Europeans. The British home and colonial secretary, Lord Sydney, chose the South Pacific; to eighteenth-century Europeans, this region was so far away, that a person exiled there might as well be going to another planet.(1) The prospect of going on such a long journey was so frightening, that many convicts felt hanging was a more merciful punishment. They may have been right, when one considers how badly they suffered at sea, and the hardships they endured right after the colony was founded.

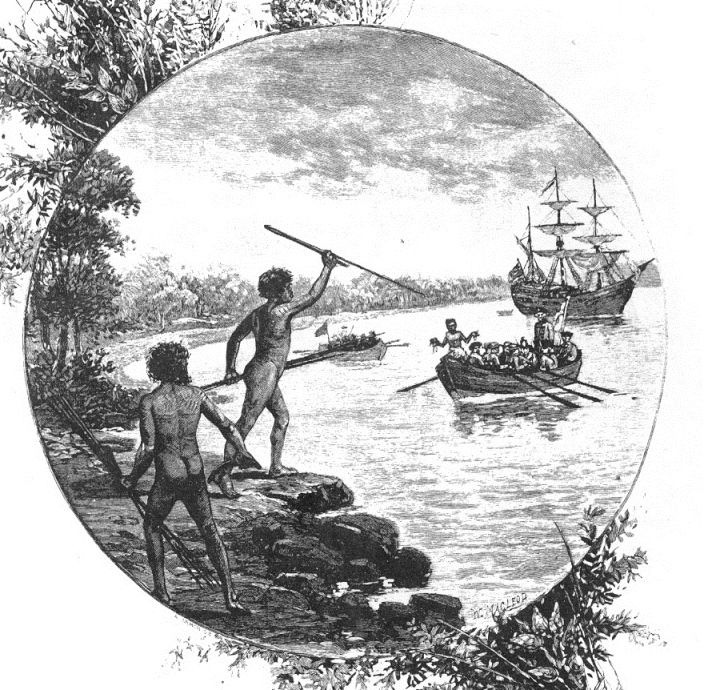

New Zealand was considered, but the government decided the Maori would kill anyone who tried to build a homestead there, so on the recommendations of Sir Joseph Banks, the scientist who had been on the first Cook expedition, Sydney picked Botany Bay, in New South Wales, as the site for the colony. Captain Arthur Phillip would lead the expedition, and become the colony's first governor after it was established. He commanded eleven ships that carried 443 sailors, 294 marines, and 736 convicts (188 of them female); three of the ships were “store ships” that carried strictly supplies. Since the marines would have to stay as the colony's first police force, only the sailors could expect to see England again anytime soon. For that reason, thirty marines brought their wives, and about twenty-five children (the offspring of either the marines or the female prisoners) also came along.

The so-called “First Fleet” set sail from England on May 13, 1787. It is a testimony to the honesty, integrity and humane attitude of Captain Phillip that although the ships were appallingly overcrowded, only forty-eight died on the 14,000-mile voyage, and because some babies were born on the way, they reached Australia with nearly as many people on board as when they started. Phillip's ship dropped anchor at Botany Bay on January 18, 1788, and the rest of the fleet arrived two days later. Though the First Fleet had made it, the British had no idea what they would do after the penal colony was established, and aside from Botany Bay, most of the continent was still a big blank spot on maps.(2)

Phillip realized right away that while Botany Bay may be a great place for explorers and scientists, it was not suitable for a colony. The harbor was unprotected; the soil was thin, rocky, and full of ants; there wasn't enough fresh water; and there weren't enough trees to supply lumber. However, Cook had discovered another harbor a few miles to the north, and named it Port Jackson. This harbor was so much better in every way that Phillip declared it was “the finest harbor in the world,” and renamed it Sydney Cove, in honor of Lord Sydney. One ship and its human cargo was dispatched to Norfolk Island, in the waters between Australia and New Zealand. Cook had reported pine trees and flax plants on Norfolk Island; those resources could be used to make spars and sails for ships. The rest of the First Fleet moved to Sydney Cove.(3) Their arrival here, on January 26, 1788, marks the date when Australia as we know it got started.(4) However, folks back in England would continue to call the colony “Botany Bay” for some time to come. Here the exiles and marines unloaded their supplies, which included the seeds and livestock needed to start farms. Hopefully these would see the colony through until 1790, when the Second Fleet was expected to bring more supplies.

On January 24, two days before the First Fleet left Botany Bay, they got unexpected visitors – two French ships, the Astrolabe and the Boussole (the “Compass”). These were commanded by Jean-François de Galaup, comte de Lapérouse, a naval veteran of the Seven Years War and the American Revolution. In the early 1780s an English merchant, William Bolts, had tried to sell the French court on the idea that France should sponsor a purely scientific expedition around the world; because Cook had been killed before he could finish exploring the northern Pacific, surely there must be something left to discover. King Louis XVI was willing to try it, but because building up French prestige was one of the goals, a Frenchman would have to command the expedition, and Lapérouse convinced the court that he was the man for the job.(5)

Leaving France in 1785, Lapérouse visited Chile, Easter Island, and Hawaii(6), and surveyed the Pacific coast of North America from Mt. Saint Elias, Alaska to Monterey, California. Then he took a cargo of furs his men had bagged to Macao, showing that the French could make a profit from that trade, and spent the rest of the winter at Manila, before heading north to the Sea of Japan. Unfortunately he did not find the strait north of Sakhalin Island, so he perpetuated the idea among geographers at the time, that Sakhalin was a peninsula of Siberia, but by sailing between Hokkaido and Sakhalin, he also proved that no part of Japan was attached to the Asian mainland. At the next stop, the Russian port of Petropavlovsk, Lapérouse learned from a French diplomat that Britain was going to found a colony at Botany Bay, and France wanted him to investigate, so he sailed directly to the South Pacific from there. In Samoa the expedition lost twelve men, including the captain of the Astrolabe, to an attack from unfriendly natives; then came repairs at Tonga and one more stop at Norfolk Island, before Lapérouse reached Botany Bay and entered our narrative.

Phillip was getting ready to leave Botany Bay, so he did not meet Lapérouse face-to-face. Still, since Britain and France were currently at peace, he didn't have a problem with the French hanging around. And because neither country had a firmly established base in Australia yet, both crews offered to help each other in the event of an emergency. One of the British ships, the Alexander, even agreed to take some journals, charts and letters from Lapérouse with it, when it returned to Europe; that turned out to be a good idea. On March 10, six weeks after arriving, Lapérouse took off; his plan was to chart the west coast of New Caledonia and then return to France via the Torres Strait. Instead, he and his two ships just disappeared.

Until the Lapérouse expedition left Botany Bay, it had been a success, so ever since 1788 the French have wanted to know what happened to the two ships after they left Botany Bay. In 1791 Rear Admiral Bruni d'Entrecasteaux left France with two more ships, to retrace the course Lapérouse was planning to take, and rescue any survivors he might find. He searched New Caledonia and the Solomon Islands; the only clue he found was smoke signals coming from Vanikoro, an island in the Santa Cruz group, but the dangerous coral reefs surrounding the island kept him from getting close enough to find out who was making them. Follow-up expeditions to the Solomon Islands, in 1826 and 1828, brought back some swords, cannonballs, anchors and scraps of French military uniforms. The natives reported that these artifacts came from two ships that were wrecked at Vanikoro, and they were identified as coming from the Astrolabe. Fast-forward to our own time; a shipwreck discovered in 1964 was identified as the Boussole, and more expeditions in 2005 and 2008 confirmed this identification as correct. Therefore we now know where Lapérouse came to grief, but we still don't know what caused him to lose both ships(7), if anyone survived the wrecks, and if any survivors were still alive in 1793, when d'Entrecasteaux visited the site.

Mutiny on the Bounty

While Britain was claiming Australia, and France was looking for something it could claim, a drama was taking place in another part of the South Pacific, one that has captured the world's imagination more than once in the centuries since then. Several poems, books, and movies have been composed about the Bounty incident, so there's a good chance you already know the story.(8) If you know it and want to skip ahead to the next section, I won't object.

Still here? All right, let's go . . .

In 1787 the Royal Navy bought a collier named the Bethia, refitted her for long voyages, and re-christened her the Bounty. They did it because Sir Joseph Banks, the scientist we mentioned previously, had an idea: if a ship picked up young breadfruit trees from Tahiti, and brought them to the Caribbean, breadfruit could be grown as a cheap food for slaves. Banks also suggested that Lieutenant William Bligh, a navigator from the third Cook expedition, be put in command of the Bounty.

A luxury cruise this wasn't. The crew lived under cramped conditions; Bligh gave up the captain's quarters to provide a room for the potted breadfruit plants on the return trip. In real life Bligh wasn't the slave-driver portrayed in the movies (a court-martial cleared him of all charges, after he got back to England), but the crew hated him anyway for his harsh punishments and foul language. Their attempt to sail around Cape Horn, an area notorious for its frightful weather, was especially hard on everyone. After fighting storms and winds blowing in the opposite direction for a full month, Bligh turned the ship around and sailed east instead of west; this meant a longer than expected voyage, across both the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Finally, ten months after leaving England, the Bounty reached Tahiti (October 1788).

They ended up spending five months on Tahiti, because it took that long to grow the breadfruit plants large enough to give them a fighting chance of surviving a long trip on the Bounty. We saw in Chapter 2 what happened when the first European ships came to Tahiti, and the Bounty's crew enjoyed the same experience; they spent a lot of their time ashore, and few slept alone. Some men got native-style tattoos, and the first mate, Fletcher Christian, married a Tahitian woman, Maimiti. Ominously, tensions grew between Bligh and the men during this time; Fletcher Christian was a frequent target of Bligh's hot temper and verbal abuse.

Naturally the men were reluctant to leave, after five months in paradise. Instead of trying to go around Cape Horn again, Bligh wanted to explore an uncharted part of Australia's northern coast on the way home. However, the men thought this was a dangerous course as well; in fact, it was the last straw. Twenty-three days and 1,300 miles west of Tahiti, while the Bounty was in Tongan waters, Christian led a mutiny. It was a bloodless affair; eighteen of the ship's forty-two-man crew joined him, and among the rest, only Bligh resisted. The mutineers put Bligh and eighteen crewmen who remained loyal into the ship's launch, and set them adrift on the open sea. Then the mutineers took the Bounty back to Tahiti, along with six non-mutineers they did not have room for in the launch.

Bligh's job was simple, but it was not easy. He had to get back to civilization, and the nearest European settlements were on Timor, an Indonesian island divided between the Dutch and the Portuguese. By traveling halfway across the Pacific in the launch, covering 4,162 miles in forty-seven days, with only a sextant and a pocket watch for navigation tools, he became a hero and showed his sailing skills at the same time. On Tofua, an island in the Tonga group, they tried to collect provisions, and the natives stoned a crewman to death; that was the only casualty they suffered. Next they were chased by cannibals on Fiji, and after passing through the Torres Strait, they reached Kupang, a Dutch outpost on Timor. From there Bligh hitched rides on several Dutch ships until he got back to England in early 1790, and reported the mutiny.

Back on Tahiti, sixteen of the men from the Bounty chose to stay there, though they knew that the Royal Navy would come for them, and Tahiti would be the first place they would search. Christian, however, decided they would be safer if no outsiders knew what island they were on, so he took the Bounty away from there with eight mutineers, six Tahitian men, twelve Tahitian women, and one baby. After wandering around the Pacific for nearly four months, they rediscovered Pitcairn Island and settled down there, burning the ship so that no one would find them too quickly (January 1789).

Christian was probably the luckiest of the former mutineers, for only those with him on Pitcairn ever saw him again. By 1800, the only man left in the group was a mutineer named John Adams, and he ruled over nine Tahitian women and dozens of children. They were discovered by an American merchant ship, the Topaz, in 1808; the crew of the Topaz was definitely surprised to find an island of Polynesians who spoke English and practiced Christianity. Today Pitcairn is a British territory with a population of 56 (as of 2013), divided between four families descended from the mutineers and their Tahitian companions.

To recover the Bounty and bring the mutineers to justice, the British admiralty dispatched the HMS Pandora to Tahiti in 1791, commanded by Captain Edward Edwards. He was the real villain in this story, not Bligh, for Edwards proved to be an incompetent commander as well as a cruel one. At Tahiti fourteen members of the Bounty crew were left, and though four of them were non-mutineers who gave themselves up willingly, Edwards locked them all up in a cage, which the prisoners grimly called “Pandora's Box.” On the way back, the Pandora passed Vanikoro and saw the smoke signals described in the previous section. These were almost certainly survivors from the ill-fated Lapérouse expedition, but Edwards was only interested in finding Fletcher Christian, and he figured that mutineers would not make a fire to announce their presence. By passing on a chance to rescue these castaways, Edwards threw away the best opportunity he had to redeem himself in the eyes of history. Soon after that, Edwards wrecked the Pandora by running her aground on the Great Barrier Reef, while trying to pass through the Torres Strait; four mutineers and 31 of the ship's 134-member crew were killed in the wreck. The rest took the ship's four lifeboats and like Bligh, crossed the Arafura Sea and made it to the port of Kupang. Back in England, the ten remaining prisoners of Edwards were put on trial for the mutiny. Of them four were acquitted, because Bligh testified they were innocent, three were pardoned and three were hanged. Edwards also had to stand trial (losing a ship meant an automatic court-martial), and was acquitted when the court ruled that running into a reef was an unavoidable accident.

As for the breadfruit trees, Sir Joseph Banks still wanted some, so a second ship, the HMS Providence, was sent to get them in 1791. Now promoted to the rank of captain, Bligh commanded the second expedition. This time he brought nineteen marines to make sure there wasn't a second mutiny, and almost everything went as planned. At Tahiti they collected 2,126 breadfruit plants, twice as many as they had loaded on the Bounty, with plenty of other botanical specimens to please Banks. This ship returned by way of the Torres Strait, and delivered the breadfruit to Britain's Caribbean colonies. However, the project was not a total success, for the slaves on Jamaica refused to eat the breadfruit. The trees thrived in the Caribbean climate, though, and Jamaicans eventually developed a taste for breadfruit; it is part of their cuisine today.

New Holland Becomes Australia

Like the first European colonists in North America, the first Australian colonists had it so rough that many did not survive. While they did not have to endure bitterly cold winters, like those who settled in Canada and New England, they did have to deal with famine and unfriendly natives. And unlike the colonization of the Americas, there were no stories of bold pioneers here; instead there are stories of cruelty, greed, apathy and despair. One man received a thousand lashes for stealing crops, six marines were hanged for breaking into the public stores, and a woman in her eighties named Dorothy Handland hanged herself from a tree (the first reported suicide in Australian history). Whereas American W.A.S.P.s (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants) may trace their ancestry back to somebody who “came over on the Mayflower,” today's Australians are not proud of their heritage if they are descended from their country's first European settlers, because those pioneers were either criminals or guards watching criminals. Which makes it appropriate that an Australian history podcast is named "Rum, Rebels & Ratbags."

It turned out the planners of the New South Wales penal colony were overoptimistic, for things began to go wrong almost as soon as Sydney was founded. For a start, most of the marines refused to do any work; they felt defending the colony was their only job and if no enemies were present, they would just mark the time until another ship came along and they got permission to return to Europe on it. Among the convicts, few of them had skills that could be used to build up the colony. When it came to choosing who would go there, all the British penal system did was make sure no murderers or rapists were sent. While some prisoners had been carpenters, bricklayers or farm hands, most were petty criminals: pickpockets, shoplifters, forgers, swindlers, etc.; in terms of age they ranged from nine to eighty-two. Because of their lack of farming experience, and because the soil turned out to be sandy rather than fertile, the first five years were a time of starvation. Crops failed; the sheep died from an unknown disease, and most of the other animals they brought (cattle, pigs and poultry) either escaped or were butchered before they could breed.

After a year of hardship, the colonists resorted to desperate measures. The only supply ship left from the First Fleet, the Sirius, was sent to China, the idea being that it could pick up enough food to see the colonists through until the Second Fleet showed up. Instead, it made a stop at Norfolk Island and ran aground there. The convicts on Norfolk Island were sent to salvage what they could from the ship's stores, and they found a stash of rum, got themselves drunk, and burned everything else. With the loss of the Sirius, the Sydney colony also lost its only means to communicate with the outside world. Some colonists tried to get the attention of any passing ship by planting red distress flags on South Head, the entrance to Port Jackson, and when Aborigines found the flags, they cut them up to make red bandanas!

Then in 1790, the Second Fleet arrived on schedule. While it was a morale-booster to know the colony had not been abandoned, one of the supply ships hit an iceberg on the way, meaning part of the needed supplies had been lost. More importantly, the fleet also brought more convicts/colonists, meaning there were more mouths to feed. One fourth of the 1,038 convicts that came with the Second Fleet died at sea, and half of the rest were so sick after the trip that they needed time to recuperate before they could do any work. The first ship to reach Sydney Cove, the Lady Juliana, carried only female convicts, to offset the shortage of women that the colony had at this point.(9) The story was repeated when the Third Fleet came to Sydney in 1791. This time 2,057 convicts left England, of which 1,875 were alive but not well (their condition appalled Governor Phillip), and the first ship to arrive, the Mary Ann, delivered 141 prostitutes.

1791 was also the year when the colony's fortunes began to turn around. One of the convicts, James Ruse, did have farming experience, and the farm he started at Parramatta, twelve miles west of Sydney, produced a decent harvest of wheat and corn. Governor Phillip decided that this area had the farmland needed for good crops; by the end of 1792, 1,000 acres around Parramatta had been turned into “commons” – public farmland -- and 500 acres had been given to individuals for cultivation. The private tracts went either to retired marines and sailors who would not go back to Europe, or to convicts whose sentences had ended early as a reward for good behavior. Some of the colonists were now in business for themselves.

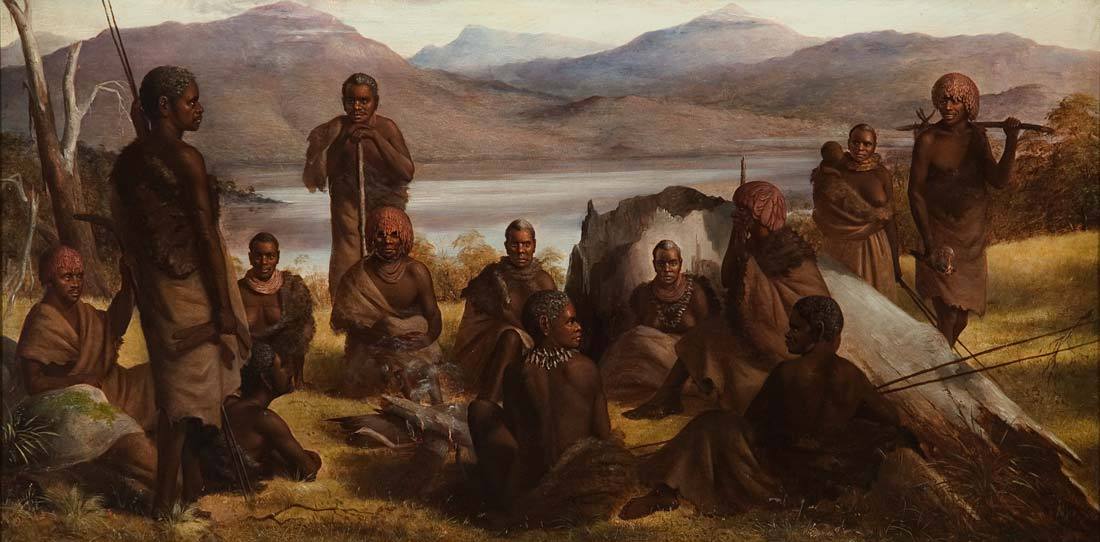

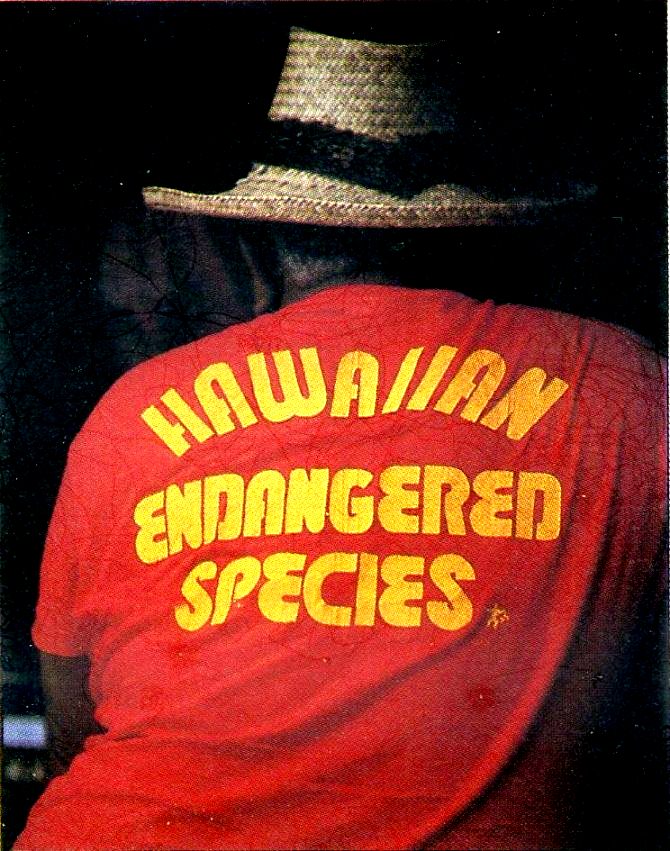

Because James Cook had reported that New South Wales was sparsely populated, none of the folks involved with planning or establishing the colony expected much trouble from the Aborigines. They did not even bother to tell the settlers that a native population existed, so the settlers arrived thinking the continent was totally uninhabited. Phillip wanted good relations with the Aborigines, but here he would not be as successful as he had been running the colony. Whereas most South Pacific peoples would adapt to Western (European) culture, and the Maori would fiercely resist the European settlement of New Zealand, the Aborigines were too primitive to do either.(10) Without permanent communities or an organization above the tribal level, they could not stake a claim to the land, and the settlers did not respect what culture the Aborigines had. In a nutshell, the Aborigines were seen as mere savages, so the settlers felt free to take advantage of them or drive them out by force. The Aborigines refused to negotiate with the British because the settlers were pushing inland, taking away places where they used to hunt and fish. Worst of all, as early as 1789 the Aborigines were catching European diseases from the newcomers, especially smallpox. Like the Polynesians and the Native Americans, they had been isolated from other humans for so long that they had no immunity to Old World diseases, so epidemics decimated their population. Soon the settlers were finding dead Aborigines on beaches and in caves, often with a source of fresh water or the remains of a campfire nearby, to prove they did not die from thirst or exposure to cold weather. While Aboriginal art and oral traditions survived in other parts of Australia, around Sydney their culture was wiped out completely.(11) Consequently the Aborigines would play no part in the development of the new nation; even today, white Australians see them as little more than an element on the fringe of modern society.

In December 1792 Phillip fell ill, resigned his governorship and returned to England. By this time there were 4,221 colonists, of whom 3,099 were convicts. After this there were no more famines, ships came more frequently, and the percentage of convicts in the population would decrease. Two months after Phillip's departure, the first free settlers disembarked at Sydney. Their names were Thomas Rose (who brought his wife and four children), Edward Powell, Thomas Webb, Joseph Webb, and Frederick Meredith.

The arrival of free men seeking their fortunes shows us that New South Wales was becoming a desirable place to live. New money-making opportunities helped a lot in this regard. In 1797 one of the most successful farmers, Captain John MacArthur, crossed English sheep with Spanish merinos, producing a breed of sheep that could thrive in that climate, and launching the continent's present-day wool industry. A small shipbuilding industry was also launched, to service the trading ships coming to Sydney; as with farming, both free settlers and convicts done with their sentences participated in this venture. When a naval vessel, the Porpoise, was sent to Tahiti in 1801 to bring back a cargo of salt pork, Sydney officially became a commercial port.

Sheep and trading were opportunities to get rich slow; the discovery that whales came to breed in the waters off Australia's east coast provided an opportunity to get rich quick. There was a rush of immigrants to hunt the whales; by 1800, the whalers outnumbered the convicts in Sydney. Their activity also led to the establishment of additional settlements: Newcastle on the coast north of Sydney, and Hobart(12), Risdon Cove and Port Dalrymple (modern Launceston) on Van Dieman's Land, the big island south of Sydney. By 1805, the combined population of all the settlements was 7,000.

New settlements were needed because the most recent shipments of criminals were larger than expected; they included veterans of the recent Irish rebellion. Many of the Irish had been deported without trial, and whether they were tried or not, they were predictably mad at being sent so far away from the Emerald Isle. This led to the Castle Hill Rebellion (March 1804), the only major convict uprising in Australian history. Here 233 convicts escaped from a farm, and stole guns and ammunition. The plan was to meet with other convicts at Castle Hill, and then march on Parramatta and Sydney; at Sydney they would either capture ships to take them back to Ireland, or proclaim New South Wales as an independent state under their rule. However, the conspiracy was betrayed by a convict who switched sides, before they reached Parramatta; martial law was proclaimed throughout the area, and the rebels were surrounded by the militia at another hill. In the resulting battle, at least fifteen rebels were killed, and the rest either ran away or were forced to surrender, ending the rebellion.(13) Of those captured, nine were subsequently executed, seven were severely flogged, twenty-six were put to work digging coal at Newcastle, and the rest were pardoned.

Because of the whalers, it became necessary to map the continent's coastline completely; two hundred years after the first Dutch landfall, Europeans had still not seen at much of the coast. They did not even know if Van Diemen's Land was joined to the mainland; up to this point all ships coming to Sydney from the Indian Ocean had gone around the island's south side. To fill in this gap on the maps, a young naval officer named Matthew Flinders and a surgeon named George Bass sailed all the way around Van Diemen's Land in 1798-99. Their discovery of Bass Strait cut as much as two weeks off travel time to Sydney, encouraging the British Admiralty to put Flinders in charge of official expeditions. In 1801-02 Flinders carefully charted the south coast, from Cape Leeuwin to Sydney; then in 1802-03 he became the first person to sail around the continent completely. On his way back to England after that, he made a stop at Mauritius to repair his ship, and because Mauritius was a French colony at the time, he tried to avoid trouble by telling local officials that he was leading a purely scientific expedition (the Napoleonic Wars were now fully underway). This was true, but the French governor didn't buy it, and detained him. Although Nicholas Baudin, a French explorer whom Flinders had met on his adventures, testified that he was a decent chap who had done nothing wrong, and Emperor Napoleon eventually sent a letter ordering his release, the governor ignored them both, and would not let Flinders go for six and a half years. Thus, Flinders did not reach England until 1810.

Finally, Captain Flinders gave the land “Down Under” its present-day name. “New Holland” was no longer a suitable name, because the Dutch had never ruled any part of the continent and it had nothing that would remind people of the Netherlands (e.g., no windmills, no tulips, no Gouda cheese, and no land below sea level). However, all the names you would expect Britain to use – New England, New Britain, New Scotland, New Ireland and New Wales – were taken. Fortunately this was also the time of the Neoclassical movement in Western art and literature, so a Latin name would work. Educated Britons in the nineteenth century liked to show off their knowledge of Latin (see this footnote from the site's Indian history). Flinders was one of them, and in 1804, while being held prisoner by the French on Mauritius, he modified the Latin word Australis (“Southern”) to get Australia. The governor of New South Wales accepted the new name for the whole continent when he found out, using it in the letters he sent to England.(14) During the next twenty years everyone else took to using the new name as well.

The Impact of Western Contact

The Traders and Whalers

The late eighteenth/early nineteenth century was a turbulent time in several parts of the South Pacific. The reason for this was the arrival of the Europeans, and the introduction of their ideas and technology, from Christianity to guns.

The last twenty years of the eighteenth century saw European activity in the Pacific increase dramatically; now that the Pacific had been mapped, it was much easier (and safer) for European ships to get around. At first this was mainly commercial traffic, and much of it involved trading with China, for there was now a huge demand in Europe and the Americas for Chinese-made goods like silk, porcelain and tea. However, the Chinese were never interested in Western-manufactured goods, so the merchants usually had to pay for what they bought with silver. To reduce the amount of cash spent, merchants looked for products the Chinese liked on the islands of the Pacific, and they found several profitable commodities the Chinese used to buy from Southeast Asia: coconut oil, tortoiseshell, pearls, sandalwood, and sea cucumbers.(15) In return for all this, the islanders often asked for guns, either muskets or cannon, now that they had seen what firearms can do. We will soon see how firearms, even in small numbers, would change the balance of power in the region.

Alas, whether the commodities mentioned above were animal or vegetable, and whether they came from the land or the sea, those who collected them did so irresponsibly, like the Easter Islanders when they chopped down trees and hunted animals to extinction on their island, centuries earlier (see Chapter 1). Because the biggest profits came from marine animal products, hunters soon followed the merchants. In 1793 the British discovered that plenty of whales and seals lived around the Galapagos Islands, so whalers and sealers began coming there regularly, starting an industry to match the fur trading going on in the North Pacific at that time. A baleen whale could provide more than a ton of whalebone for corsets and hoop skirts; in London you could sell that for enough money to pay for the ship that caught the whale in the first place. Even more valuable was whale oil, used to light lamps in the days before the discovery of kerosene. More than two tons of whale oil could be obtained from a single sperm whale. So wherever the hunters went, they inflicted an environmental holocaust on the animal life. They did not take the hint when the North Pacific fur traders put themselves out of business in the 1820s, by hunting the sea otter to near-extinction. Soon after that, the waters surrounding many islands that had once teemed with life were left empty and silent.

We saw in the previous section that “bay whaling” attracted fortune seekers to Australia, and the ports of Hobart and Sydney made good money off whaling from 1805 to 1835, but the whalers pursued it so aggressively that the profits couldn't last. By the 1840s there weren't enough whales left to be worth hunting, and the Australian ports suffered a slump after the whalers moved away. In New Zealand the industry had attracted a seasonal population; it hunted whales wholesale and clubbed hordes of seals to death, and like the whalers in Australia, these hunters took off when the game ended. At the industry's peak, around 1830, there had been as many as 500 bay whalers and sealers, living in stations on the southern coast of South Island; after their departure, less than 100 traders and missionaries remained, mostly on North Island.

Deep-sea whaling was profitable much longer, because the open sea had more whales to catch. In fact, this industry lasted until the late twentieth century; in 1986 the International Whaling Commission banned commercial whaling to increase the world's whale population, but a few nations (e.g., Iceland, Norway, Japan, Russia) and the native tribes living in the Arctic still hunt whales on a small scale even now. It was a tough business, though, because the whalers were out at sea most of the time, following pods of whales. When a whaler left its home port, it did not return until all the barrels in its cargo hold were full of whale oil, so it could be gone for three years or more. The British may have started this hunt in the Pacific, but after 1820 most whalers came from the United States; because their home ports were in New England, they had to sail around South America to get to the hunting grounds. When they weren't chasing whales or processing their catch, the whalers needed ports for rest and resupply, and soon Hawaii became their favorite stopover. Hawaii also received quite a bit of traffic because its location made it an ideal place for traders to stop, when traveling between North America and Asia. Consequently the “Sandwich Islands” began to fall under American influence, long before the Americans had any ports on the Pacific coast of their home continent.

Merchants involved in the sandalwood trade were also looking for a quick profit. When a forest containing sandalwood trees was discovered, they began making regular visits to harvest this fragrant, yellow wood for Chinese consumers. The natives eagerly traded away their sandalwood trees for Western-made goods, because sandalwood was otherwise useless to them. If the island with the trees was inhabited, they would stay long enough to negotiate a price to pay the natives, but either way they did not plant new trees, or do anything else to keep sandalwood collecting at a sustainable level. Then when the island had no more sandalwood trees, the traders simply moved to another island that still had them.

From 1804 to 1816, the best source of sandalwood was Vanua Levu in Fiji; because of the ongoing Fijian civil war (see below), that island's fortunes rose while Europeans came there for sandalwood, and fell when the sandalwood was gone.(16) Wherever the traders went, the natives might try to get what they wanted through theft, murder or fraud, so the sandalwood and sea cucumber trades gained a reputation for danger and depravity. And commodity prices could change tremendously by the time the traders got to China, depending on how long it took to collect and transport the commodities, and the current demand for them. Thus, a merchant in this business needed luck as well as skill to turn a profit. For example, the most successful sandalwood merchant, Robert Towns, reported making £2,000 on one voyage and losing £1,300 on another.

Throughout Melanesia, merchants looked for ways to make their business more profitable and less volatile. There was the manner of how they did business with inhabited islands, to start with. A merchant ship could simply drop anchor and the natives could bring their commodities to it, trading directly with the crew, but that made the ship and crew vulnerable if the natives decided to attack. Another risk was that the ship might arrive when the natives had not harvested any goods to trade; the crew would then have to wait, with the ship losing money every day they were idle. If the natives were busy with planting/harvesting crops, a war, or a major ceremony, the captain would have to decide whether it was worth it to wait until they were done. If the commodity was sandalwood, crewmen could go ashore and cut it themselves, but that added a lot of extra work, and the ship was dangerously undermanned until they returned.

Eventually merchants hit on a better solution; set up a trading post where the natives could bring their goods, and the ship would pick them up here. This way the ship did not need to stay any longer than needed to load a cargo, and paying the natives was less risky. Of course someone would need to stay and manage the trading post, and as noted in the previous footnote, few white men wanted to spend time in Melanesia if they could help it. But as it turned out, only one white man was needed in the trading post (the rest of the workers could be hired natives), and the natives felt they still had some control over the trade if they gave the white overseer a female companion, making him an in-law of sorts to the tribe.

A side effect of the commerce in Melanesia was that Melanesians working for whites eventually developed a pidgin language that wasn't hard for them to learn, one which combined English words with Papuan grammar (see also Chapter 1, footnote #8). We talked in Chapter 1 about how Melanesians were extremely divided by language, so when pidgin English became the lingua franca of Melanesia, a major barrier preventing native cooperation was overcome.

Meanwhile in Polynesia, a few whalers and traders on the north-south route between Tahiti and Hawaii were stopping at the Marquesas Islands. This was interrupted in October 1813 when six ships, commanded by US Captain David Porter, arrived at the island of Nuku Hiva for repairs. Only one of the ships was American; the War of 1812 was now underway, and the other ships were British vessels Porter had captured, while prowling near the Galapagos Islands. The crew built a small village for their stays ashore, established friendly relations with the nearest tribe, and defeated two other tribes they didn't get along with. Then Porter claimed the island for the United States, calling it Madison's Island, after the current US president (the US government wasn't interested in following up on this claim, though). But in March 1814 his warship was captured off the coast of Chile, and Porter was sent home to New York in one of the ships he had taken previously. Another one of the rescued British ships went to Sydney with news that the Marquesas had sandalwood, and from 1815 to 1820 a series of ships came from Sydney to gather it, until the Marquesan sandalwood was gone as well.

We noted in Chapter 1 that because Micronesia's tiny islands have few people and few resources, Micronesia is the poorest part of the Pacific. Also, Micronesia had a reputation as a dangerous place for Europeans, thanks to hostile incidents like what happened when Spain sent missionaries to Palau in the early 1700s. The danger and the lack of products to trade meant that only a few merchants and missionaries came this way before the second half of the nineteenth century. As for the whalers, they stopped for rest and resupply on Kosrae and Pohnpei, but those were the only islands in the region big enough to supply the needs of a whaling ship and its crew.

Besides over-hunting, the hunters also disrupted Pacific communities with alcohol, violence, and disease. Some of them were escaped convicts, navy deserters and former mercenaries – rough men who mainly wanted liquor and sex when they came ashore. And even if they did not make trouble, they introduced influenza, smallpox, measles, tuberculosis, and cholera, which decimated populations that had not been exposed to those diseases already.(17) For many island communities, the arrival of the missionaries was a relief from the drunkenness, prostitution and disorder that the hunters brought.

The Missionaries

The third group to follow the explorers searched for souls, rather than animals or profits – missionaries. Protestant churches had been in existence since the sixteenth century, but only after the eighteenth-century revival called the “Great Awakening” did they feel a burden to spread the Gospel beyond Europe and North America. Because of the expense and distances involved, several denominations pooled their resources, to form the London Missionary Society in 1795. They acquired a boat, the Duff, and it was used to transport twenty-nine missionaries and five of their wives to Tahiti in 1797. Tahiti was chosen as the first destination because the reports of previous visitors convinced them that on this island “the difficulties were least.” Whereas other Europeans saw the Tahitians as “noble savages,” the missionaries saw them as sinners who needed to be saved from Hell.

“The Cession of the District of Matavai in the Island of Otaheite [Tahiti] to Captain James Wilson for the Use of the Missionaries Sent Thither in That Society by the Ship Duff.” In this scene, painted by Robert Smirke in 1799, the Tahitian king Pomare I (at left, kneeling and holding a red robe) gives a tract of land to the London Missionary Society, for future buildings. Two of his wives are being carried piggyback by servants in the background.

Stories about missionaries tend to talk about failure before success, and that was the case with the Tahiti mission. The plan was to split up this group after they reached Tahiti; half of them stayed here, the Duff delivered some of the others to the Marquesas Islands, and finally the Duff took the rest to Tonga. But within a year all but one missionary on Tahiti had given up and left, and the Marquesan mission had likewise been abandoned. From a Christian point of view, the failure of the Tongan mission was the worst, because its chief missionary, George Vason, was himself converted to the easygoing Polynesian lifestyle. But even if Vason had stayed faithful, the outbreak of Tonga's civil war (see the next section) meant the neighborhood was getting too dangerous; three men from the group were killed and the mission was abandoned in 1799.(18) That was the low point of Christianity in the South Pacific. Some of the missionaries that had gone to Tahiti returned later for another effort, and reinforcements began to arrive in 1801. Still, the mission was impoverished and neglected; they converted hardly anybody before 1808, when Tahiti's civil war drove them off-island again.

Eventually individual denominations sent their own missionaries, starting with the Anglican Church Missionary Society, which started a mission in New Zealand in 1814.(19) By the end of the 1820s there were more than a hundred British, French and American missions, scattered across the islands of the Pacific.

With remarkable speed and ease, the missionaries succeeded in imposing an alien code of laws and morals on the local cultures. To start with, they got native communities to give up nudity, casual sex, cannibalism, infanticide, headhunting, and ritual sacrifice, customs Christians had no business practicing. However, they had a harder time fighting the problems which were caused by other white men, like drunkenness and disease. Native chiefs often welcomed missionaries to their communities because they were more honest than the traders or hunters, and if they knew medicine or construction techniques or could teach literacy, they could be useful in those ways.

Back in 1772, right after the French learned about Tahiti, the philosopher Denis Diderot wrote Supplement au Voyage de Bougainville, and because this was the time called the “Enlightenment” or the “Age of Reason” in Western civilization, he warned the Tahitians what would happen when the Europeans converted them to Christianity: "One day, under their rule, you will be almost as unhappy as they are." Sure enough, the missionaries would have a greater impact on the Tahitians and their culture than the explorers or mutineers did.(20) As the nineteenth century began, many Tahitians wore Western-style clothes, attended church on Sunday, and got jobs that made them work regular hours, like gathering coconuts for export. Singing and dancing were discouraged, women cut their hair short, and even the weaving of flower garlands was banned. Most of all, the old institution of tapu (see Chapter 1) was abolished, to be replaced by a feeling of guilt because the missionaries taught that all people are sinners.

Even the introduction of European-made iron tools and clothes could be harmful to native societies, because islanders forgot their skills for making traditional bark-cloth and tools out of stone and bone. Thus, they became dependent on Europeans and Americans, to the point that they could not go back to their previous lifestyle of isolation and innocence if they had wanted to. On a positive note, some Tahitians (and also Hawaiians and Tongans) did benefit from the economic opportunities the foreigners brought. Finally, because events closer to home kept them busy most of the time, outside nations would not try to rule the islands of the Pacific until the second half of the nineteenth century, and usually they did so by cooperating with local leaders, rather than simply replacing them with officials from the mother country.

Unrest In the Islands

Before the late eighteenth century, Tonga was about the only place in the South Pacific with a state ruling more than one island. We saw in Chapter 1 that traditionally wars in the South Pacific had been ritualized affairs; they were most often caused by one community's desire to avenge an insult (real or imagined), and usually a few rounds of skirmishing was enough to settle the matter. However, now communities followed a more Western-style strategy; they went to war with the goal of exterminating or conquering the other side completely, with the annexation of the loser's territory by the winner. Thus, we see the inhabitants of other archipelagoes beside Tonga try to build multi-island states. But only in the Hawaiian Islands was the unification process completed. Elsewhere foreign powers (Europe and the United States) interrupted the process by taking over first, and no would-be Pacific Napoleon ruled any islands beyond his home archipelago.

Tonga

Though Tonga had the oldest, most elaborate monarchy in the South Pacific, even it experienced trouble during this time. We saw in Chapter 1 that the original ruling dynasty, the Tu'i Tonga, was relegated to figurehead status when another dynasty, the Tu'i Ha'atakalaua, was established, and later the Tu'i Ha'atakalaua in turn had to cede power to a third dynasty, the Tu'i Kanokupolu. This arrangement lasted through most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, though a series of intrigues meant that succession was not always from father to son; there was even a female ruler in the early 1790s, Tupou Moheofo. Then in 1799 the current Tu'i Kanokupolu, Tuku'aho, was murdered, and the system came undone. The last Tu'i Ha'atakalaua ruler had died in 1797, and his successor had not been recognized by everybody, so everyone saw vacancies in the leadership of two of the three royal houses as an excuse to start a civil war. The chief of the island of Vav'au, Finau-'Ulukalala II, did not get along with Tuku'aho, so he used this occasion to declare independence, and the Ha'apai islands joined him, making Finau-'Ulukalala ruler over two thirds of Tonga. Meanwhile, the next Tu'i Kanokupolu ruler was killed on the same day that he took charge, causing an interregnum. Due to the chaos that followed, there was no Tu'i Kanokupolu from 1799 to 1808, and no Tu'i Tonga from 1810 to 1827.

Outsiders could not sit out the civil war. In 1802 an American ship, the Duke of Portland, came to Kanokupolu, the home village of the Tu'i Kanokupolu. A local chief, Teukava, requested aid from the crew in driving off invaders from another island; they did so, and the chief offered gifts in return (yams, tapa cloth, roast pigs and fish). The next day, part of the crew went ashore in two boats to collect supplies, while several native canoes showed up full of men and the promised gifts. When the natives came aboard, they began to loot the ship; the captain, Lovett Mellon, and the crew were killed in the battle that followed. The only ones spared were two American women, Elizabeth Morey and her black maid Eliza. Those two became the first female castaways in South Pacific history, and their ship was the first vessel from the outside world captured by Pacific islanders.(21)

Elizabeth Morey became one of Teukava's wives, and she appears to have given birth to three of his children, two of them while she was held captive. Two years later (1804) another American ship, the Union, showed up. Seeing her chance to escape, she swam out to the ship and was taken aboard, but the Union suffered the same fate as the Duke of Portland; the Tongans attacked and killed the captain and seven crewmen. When the ship managed to get away, Morey was taken to Sydney, where she gave an account of her adventure. Unfortunately for us, she said nothing about her life before arriving in Tonga, and later she even returned to Tonga for the birth of her third child. A 1999 article proposed that Morey originally came from Massachusetts, went out to see the world because she was an orphan, and traveled on the Duke of Portland as the captain's romantic companion. If these facts are true, the captain broke several laws/regulations to bring her along.

A British privateer, the Port au Prince, dropped anchor at the Ha'apai group of islands for repairs and resupply, in 1806. Because of the civil war, the chief on the spot, Finau-'Ulukalala II, saw the ship as fair game, so his warriors came on board, stole all the muskets and ammunition, and massacred the crew. Before the crewmen died, however, they managed to sink the ship, thereby keeping the Tongans from using it. William Mariner, a fifteen-year-old cabin boy, was allowed to live, adopted by the chief, and given the name Toki Ukamea. He stayed in Tonga for four years, and was allowed to leave when another British ship showed up. Back in England, Mariner wrote a 460-page book about his experience, An Account of the Natives of the Tonga Islands, in the South Pacific Ocean. It is still good reading today, not only because it is an exciting adventure tale, but also because it is our best source of information about the Tongan and Samoan cultures, before they were altered by Western civilization.

I will share one excerpt from Mariner's book before resuming the narrative, because it shows how the Tongans could have a different outlook on the world and be clever at the same time. Since Finau-'Ulukalala could not have the Port au Prince intact, he decided to salvage whatever was valuable from the wreck, and burn the rest. While looking over the wreckage, they found the treasure the privateers had taken in successful raids – 12,000 copper, silver and gold coins. The chief refused to take the coins, thinking they were just playing pieces from a game. When Mariner told Finau-'Ulukalala that those metal disks were called money, and they were what the crew valued the most, the chief gave the following reply:

“If money were made of iron and could be converted into knives, axes and chisels there would be some sense in placing a value on it; but as it is, I see none. If a man has more yams than he wants, let him exchange some of them away for pork. [...] Certainly money is much handier and more convenient but then, as it will not spoil by being kept, people will store it up instead of sharing it out as a chief ought to do, and thus become selfish. [...] I understand now very well what it is that makes the papālangi [white men] so selfish — it is this money!”

The Tongan word for gaming pieces is pa'anga, and because of this episode with the privateers' loot, when modern Tonga issued its own currency, it named the main unit the pa'anga.

Methodist missionaries arrived in Tonga in 1826, beginning a successful campaign to convert the islands to Christianity. They became players in the civil war by baptizing the next Tu'i Kanokupolu leader, Aleamotu'a (1827-45); he responded by changing his name to Josiah Topou. This meant the civil war now had three main factions: Christians supported the Tu'i Kanokupolo, pagans supported the Tu'i Tonga (the Tu'i Tonga's authority came from the old-time religion), and the Vav'au separatists fought without religious backing.

Meanwhile, the person with the best claim to the Tu'i Kanokupolo title was not Josiah Tupou but a grandson of Tuku'aho, Taufa'ahau; Josiah got the title because Tafau'ahau was too young in the 1820s. Instead, Taufa'ahau was given the title of Tu'i Ha'apai, meaning he ruled just his birthplace. In 1831 missionaries baptized Taufa'ahau as well; henceforth he would call himself George Tupou I (after Britain's King George III). Then he divorced all but his favorite wife, who renamed herself Charlotte, after George III's queen. The leader of the Vav'au faction, Finau-'Ulukalala III, died in 1833, and because he happened to be George Tupou's father-in-law, George staked his claim and made himself the next ruler of Vav'au. Thus, when George Tupou succeeded Josiah Tupou as Tu'i Kanokupolo in 1845, all of the Tonga isles were effectively brought under his rule. That marked the end of the Tongan civil war, though George's main opponent, the Tu'i Tonga, was still at large. The next twenty years saw a slow and painful reunification of the country, pitting Christians against traditional pagans and Protestants against Roman Catholics.

The Society Islands

When the Society Islands were discovered in the 1760s, they were loosely organized into four states that are best described as confederacies, because each had more than one chief running it; Tahiti, for example, was divided between three “high chiefs.” All chiefs claimed descent from a legendary high chief named Hiro. In addition, few chiefs ruled alone; as soon as a chief appointed an heir, the heir was considered a new chief, with the older one sticking around as the official regent.

Internal upheaval came to the Society Islands as a religious revolution. Previously, Tahiti and the surrounding islands had worshiped four major gods: Ta´aroa (god of the sea and fishing, also spelled Tangaroa), Tane (forest and handicrafts), Tu (war), and Ro´o (farming and weather, also spelled Rongo). Then in the second half of the eighteenth century, the priests of Raiatea, the religious center of the Society Islands, began promoting a new war god, 'Oro, the son of Ta´aroa. This god was a bloody one, demanding more human sacrifices than the older Tahitian gods, so the cult of 'Oro generated a reign of terror as it got popular. In the 1760s a Tahitian chief named Teu Tunuieaiteatua tried to unite Tahiti under himself, using the cult of 'Oro as his ideology. He wanted to do this because one of the other chiefs wore a stunning girdle made of red feathers, and he thought that would make a great symbol for 'Oro.(22) But Teu's opponents formed an alliance to keep him from winning the girdle and the honors.

Teu's son, Tu, had a better time of it. Between 1788 and 1791 Tu established himself as Tahiti's foremost chief, got the chiefs of several nearby islands to recognize him as the highest-ranked chief of all, and changed his name to Pomare I. With Teu's death in 1802, Pomare became the sole ruler of the island, and though he in turn died just a year later, he had founded the royal Tahitian dynasty. However, under him the war of unification stopped being a crusade for 'Oro. While Pomare continued to follow 'Oro, he also became a patron of the Christian missionaries who came to Tahiti, first the Spanish ones in the 1770s, and then the British ones in the 1790s, because he saw them as a way to get Europeans to support his cause.(23) Later we will see his son Pomare II convert to Christianity, abandoning the old gods altogether.

Fiji

The Fijians probably tried unification because they were inspired by neighboring Tonga's early success at it. On the two largest islands of Fiji, rival political factions arose, each based in a different district: Ba, Ra, Verata, Bau, and Rewa on Viti Levu; Cakaudrove, Macuata and Bua on Vanua Levu. Another faction brought together the Lau Islands of eastern Fiji under one authority. Most interesting to us, however, is the faction based on Bau, a tiny island just off the east coast of Viti Levu. This faction became the most successful of all, due to two strategies: a series of marriages which united the families within the faction; and making it a priority to build a superb fleet of catamarans, crewed by the Lasakau sea warriors, between 1760 and 1790. Bau had to become a sea power because it did not have enough land to become a land power, like the other Fijian factions.

Bau also was the first Fijian faction to use firearms, thanks to the timely arrival of a European who joined them. We don't know his original name – nowadays he is called Charlie Savage – and the stories we have about him cannot be verified as accurate. What we do know is that he was a sailor on a ship that traveled from Sydney to Tonga in 1807, and he rode on a second ship to Fiji, which was wrecked upon arrival. From the wreckage, Savage recovered and repaired several muskets, which he demonstrated to the Bau leaders. After that, he led a small group of European beachcombers/mercenaries that were very effective, not only because of the muskets, but also because they were not restricted by Fijian rules of warfare (i.e., they aimed at enemy chiefs even at the beginning of a battle). In this way he helped Naulivou, the chief of Bau, conquer the Verata faction, and in return Naulivou gave Savage titles and two high-ranked women for wives. But Savage was then killed in a skirmish in 1813, so he did not get to enjoy his triumph for long. Later in this chapter we will see the nephew of Naulivou, Ratu Seru Cakobau, rise to become first chief of Bau, and then the most powerful chief in all of Fiji.

Kamehameha the Great

Originally the chiefs of Hawaii had been independent, and their mini-kingdoms were typically wedge-shaped: each held several miles of coastline, which narrowed to a point in the less desirable interior. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, petty wars were commonplace, between the islands and between the chiefs on each island. By the time Captain Cook discovered the archipelago, four larger states had arisen, dominated by the largest islands: Hawaii, Maui, Oahu and Kauai. While the Big Island and Oahu were one-island states, Maui dominated nearby Molokai, Lanai and Kahoolawe, and Kauai ruled Niihau.(24) The individual chiefs remained in power locally, but in each state one chief, called an Ali'i, lorded over the others; we can call him “king.”

The Hawaiian chief we mentioned in Chapter 2, Kalaniopuu, was “king” of the Big Island in the 1760s and 1770s. His main rival was the king of Maui, Kahekili II; in 1776 Kahekili used an ambush to defeat an invasion of Maui by Kalaniopuu. The main character of this narrative, Kamehameha, was a nephew of Kalaniopuu, either twenty-one or twenty-three years old(25), but already an experienced warrior, and a prominent member of the king's court at the time of Cook's visit. Because he wore some kind of paste or powder in his hair, Kamehameha looked particularly scary to the haoles, though he was friendly to them at the same time, and asked them many questions about the amazing gadgets they used. Already he was thinking that European cannon and ships would be the key to building a kingdom larger and stronger than any that had existed in the islands before.

Kalaniopuu died in 1782. His son Kiwalao became the next Ali'i, while Kamehameha became guardian of the war-god Ku. However, the two cousins never got along very well, and war broke out between them a few months later, when five lesser chiefs offered to back Kamehameha in a bid for the throne. Because he possessed the image of the war-god, Kamehameha was confident he would win, but it took four years of fighting before Kiwalao was killed in battle, and after that Kamehameha ruled the west side of the Big Island, while two other contenders ruled the east and south sides. Meanwhile to the west, Kahekili of Maui conquered Oahu and replaced its king with his son (1783). Because the king of Kauai was a relative of his, Kahekili was now technically the most powerful ruler in the Hawaiian Islands.

By this time traders were coming to Hawaii, and Kamehameha let them know that of all the goods they had to sell, he wanted guns and ammunition the most. To pay for what he bought, he had teams go into the mountains on the Big Island and cut down sandalwood trees (this resource lasted until the 1820s). Two sailors, Isaac Davis and John Young, were kept on as advisors, and they trained Kamehameha's troops to use firearms. By mounting cannon on the platforms of catamarans, Kamehameha's force was able to prevail, even when several rivals joined forces against them at the battle of Kepuwahaʻulaʻula (red-mouthed gun).

Most of the time, however, the struggle for supremacy among the chiefs was confined to raids on each other's territory. In 1790 Kamehameha asked a kahuna (priest) what he needed to do to win the war, and the priest recommended he build a new heiau (temple) and dedicate it to the god Ku. Kamehameha then built a temple so massive that it took a year to finish, even with a work crew numbering in the thousands, and he vowed to dedicate it with the sacrifice of an enemy chief. While construction went on, he overthrew his eastern rival, Chief Keawemaʻuhili. That left Keōua Kūʻahuʻula, the brother of Kiwalao, who took advantage of Kamehameha's absence to launch a revolt. When Kamehameha and his army returned and defeated the rebels in the battle of Hilo, Keōua fled southward, and as his warriors passed the Kilauea volcano, it erupted and killed nearly a third of them with poisonous gasses. This convinced many Hawaiians that Pele, the volcano goddess, was on Kamehameha's side.(26)

When the new temple, the Puʻukoholā Heiau, was completed in 1791, Kamehameha invited Keōua to come and negotiate a peace treaty. Keōua must have known his cousin was luring him with a ruse, but he came anyway; he may have been surrendering to fate, after losing his army to both a battle and an eruption. One version of the story asserts that he mutilated himself on the way in ensure he would be unfit as a sacrificial victim. But when they stepped ashore, somebody threw a spear at Keōua; though he dodged it, he and his retinue were ambushed and killed. Their bodies were offered at the temple anyway, and Kamehameha became king of the whole island of Hawaii.

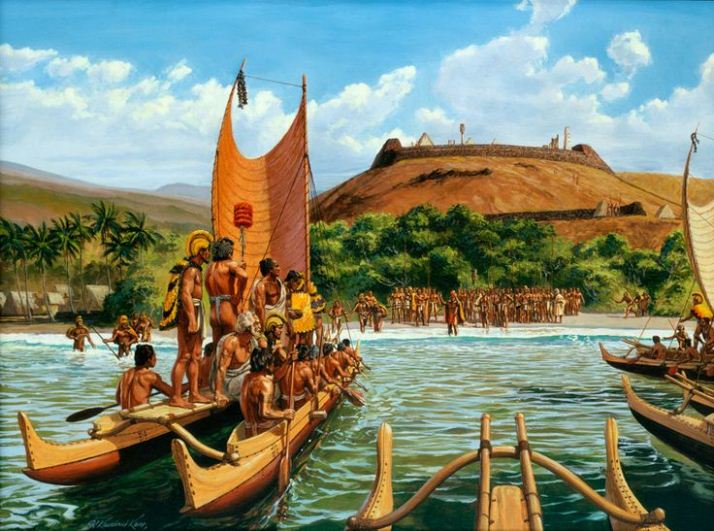

Keōua arrives at the Puʻukoholā Heiau. He was killed one minute later. Painting by Herb Kawainui Kane (1928-2011).

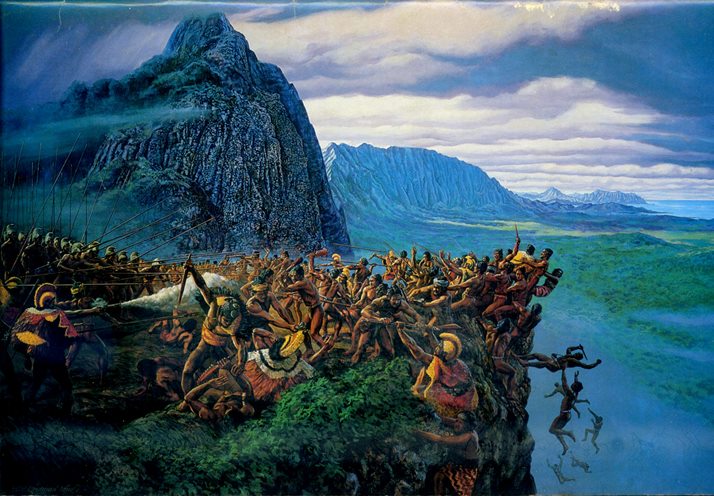

Kamehameha dreamed of ruling other islands as well, but he bided his time, waiting for the opportunity to strike. It came in 1794, when Kahekili died and his brother and son fought over who would be the next king of Maui. In 1795 Kamehameha sailed to Maui with 960 canoes and 10,000 warriors, an awesome force when one considers that the Hawaiian Islands probably never had more than 150,000 people up to this point. The resulting battle of Kawela was an easy victory, which secured Maui and Molokai without too much fuss. However, when this armada moved on to Oahu, they saw fiercer fighting, for the chief of Oahu, Kalanikupule, had also collected cannon and muskets. The battle of Nuuanu could have gone either way, until Kamehameha's men captured the defending cannon; after that, Kalanikupule's warriors were forced up a valley, until more than 400 of them were pushed off the cliffs, or jumped to their deaths.

The battle of Nuuanu. Painting by Herb Kawainui Kane (1928-2011).

The only Hawaiian islands left that weren't under Kamehameha's rule were Kauai and Niihau. He tried to invade these islands in 1796, but bad weather and a rebellion on the Big Island forced him to turn back. A second invasion in 1803 was stopped by a disease epidemic. Then he built up a huge fleet for a third attempt, which included some European ships and war canoes armed with cannon. Kaumualii, the king of Kauai, decided that he could not beat such a force, and negotiated a peaceful settlement in 1810, in which he became a vassal of Kamehameha. This united the archipelago at last, and upon Kaumualii's death in 1824, Kauai and Niihau came under the direct rule of Kamehameha's family.

Now that the wars were over, Kamehameha returned to his court at Kailua-Kona on the Big Island and devoted the rest of his reign to ensuring that the Hawaiian Islands would remain united and independent after his death. He did not allow non-Hawaiians to own land, and he appointed governors over each island that were either loyal chiefs under him, or trusted allies. To pay the costs of rebuilding and developing the islands, he collected taxes in food and later in sandalwood. And while he felt Western ideas were good for the new nation, he did not think they were good for the people, so he minimized casual contacts with the outside world; for example, he continued to practice the traditional paganism, though in a concession to Christian outsiders, he outlawed human sacrifice.

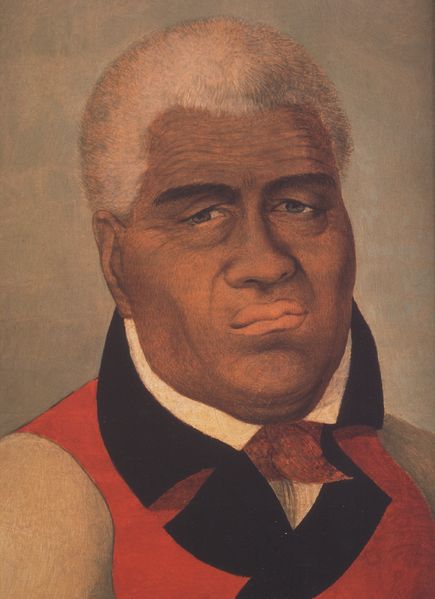

Kamehameha I, late in life.

Kamehameha also retained the harsh, kapu-based system of laws and punishments, but also introduced a piece of human rights legislation, something you rarely hear about in the history of non-Western societies. The story goes like this: back around 1782 he was a young warrior leading a raid, and while chasing some fishermen, his foot got caught in a rock crevice. One fisherman turned around, and hit Kamehameha on the head with a canoe paddle so hard that the paddle broke. But before he could hit Kamehameha again, another fisherman pleaded that he be spared, so they ran away, leaving him for dead. Twelve years later, the fisherman who struck Kamehameha was brought before him. Still deeply moved by the incident, Kamehameha declared he – and not the fisherman – had been the evil person on that day, for attacking innocent people; instead of punishing the fisherman, he let him go free with gifts of land. Then he decreed the Māmalahoe Kānāwai, the “Law of the Splintered Paddle,” which ordered that all civilians be left alone in wartime: "Let every elderly person, woman, and child lie by the roadside in safety."(27)

Kamehameha died in May 1819. Knowing that the end was near, his family and friends gathered around his death mat and asked for a final message; he told them, “Endless is the good that I leave for you to enjoy.” Two trusted friends, Hoapili and Hoʻolulu, had him buried in a secret location, due to the belief that because he succeeded in everything he did, his mana level must be off the scale; therefore no part of his body should be allowed to fall into the wrong hands. We still do not know today where he is buried. Two generations later, King Kamehameha III asked Hoapili to show him where his father's bones were, but on the way to the burial spot, Hoapili realized they were being followed, and turned around without revealing the place. Although Kamehameha had brought peace and prosperity to Hawaii, he had also changed the islands forever, without fully realizing it.

Australia Developing

The Napoleonic Wars ended with the battle of Waterloo in 1815, and in the aftermath, the empires of Great Britain's European rivals were in ruins. All that the French had left were some Caribbean islands (but not Haiti, their biggest prize), French Guiana, a few trading posts in Senegal, Réunion Island in the Indian Ocean, and five insignificant outposts in India. Most of Spain's empire was in revolt and would soon be lost, and Portugal was about to lose its most important colony, Brazil. The Dutch only had an empire because Britain gave back part of what it took during the war years, and for the rest of the nineteenth century the Dutch kept themselves busy by exploiting and strengthening their control over Indonesia. The part of this which affects our narrative is the western half of New Guinea, which the Dutch claimed because it was next to Indonesia; Britain recognized their claim in 1824. New Guinea was thus divided in two, with the border between the Dutch half and the unclaimed half following the 141st meridian. In 1828 the Dutch set up a colony near present-day Kaimana, but it failed. Because the Dutch had shifted their attention from Australia to the islands north of it, Britain now felt confident enough to claim all of Australia, and would not worry about what others might think (compare this with footnote #2).

So far most of the Australian communities we have mentioned were either coastal settlements, or just a few miles inland. In 1813 an expedition of three explorers and four servants, led by Gregory Blaxland, blazed a trail over the Blue Mountains, in the area west of Sydney, and found well-watered forests and grassland on the other side. Recognizing that this would be a good place for sheep ranching, another pioneer, William Cox, organized a work detail to build a dirt road along that path in 1814-1815, and the town of Bathurst was founded at the end of the road. It was the first community in Australia's interior, or as we call it nowadays, the outback. However, this achievement would not be repeated right away. Another explorer wandered west of the new grazing lands in 1817, found nothing promising, and reported on his return that “for all practical purposes of civilized man, the interior of this country, west of the 147th meridian, is uninhabitable.” Of course this ignored the fact that the Aborigines had been living there for thousands of years, with equipment far more primitive than what the Europeans had.

And after our civilization falls, you can expect to find this guy living there.

Still, everyone had to agree that the lands discovered after the founding of Bathurst were less inviting: hot grasslands and tree-dotted savannas, or outright deserts. Being a frontier environment, it required strength, courage, and an attitude of self-reliance to live in such a place. While the cities were getting started, life in them was adventure enough for most folks; the bold individuals who wanted to “get away from it all” would come later, when the cities were no more exciting than cities in Europe or North America.

At this point, the best sites for new cities were at the harbors discovered on the Australian coast in the early 1800s. Thus, Brisbane was founded on the northeast coast (1824), Perth was founded on the west coast (1829), and Melbourne (1835) and Adelaide (1836) were founded on the south coast. Some reorganization of the colonial government(s) also took place. In 1825 Van Dieman's Land, which previously had been part of New South Wales, was declared a separate colony. The same year saw the western border of New South Wales moved from longitude 135º E. to 129º E., increasing Britain's share of the continent from half to two-thirds. Then when Britain heard rumors that France was interested in establishing a colony in the west, it beat the French to it by founding a military outpost named Albany near the southwest corner of the continent (1826), and Perth and Fremantle along the Swan River. With this move, Britain stopped calling the west “New Holland,” renaming it first the Swan River Colony (1829), and then Western Australia (1832). Adelaide, named after the current queen of England, was founded by a proposal to start a colony in the southwest quarter of New South Wales that had only free settlers – no convicts, no religious discrimination, and no unemployment would be permitted here. This became the colony of South Australia (1836). And because Australians were now demanding representation in the government over them, Britain allowed New South Wales to elect the continent's first legislature in 1842; the other colonies also got legislatures from 1850 onward.

The land outside the cities was called the “back country” at first. The modern term “outback” was first used in an 1869 newspaper article; today's Australians will also refer to the countryside as “the bush.” Whatever you call the hinterlands, even today it is one of the most sparsely populated places in the world. More than 90 percent of today's Australians still live in the cities, and even with a metropolis as large as Melbourne, the outback comes close enough to the city limits that you can drive away from the city and be in the outback within an hour.

The first pioneers to cross the Blue Mountains also discovered several westward-flowing rivers, like the Lachlan, the Macquarie and the Murrumbidgee. The main goal of the explorers who came after them (John Oxley, Hamilton Hume, William Hovell, George Macley and Thomas Mitchell) was to chart the course of those rivers. For a while it was thought that they flowed into a lake or inland sea. Instead, another explorer, Charles Sturt, found out they flowed into the Darling and Murray Rivers; then the Darling in turn flowed into the Murray, and the Murray emptied into a lagoon on the south coast, near Adelaide. For his last expedition, in 1844, Sturt went up the Murray and Darling and then headed for the center of Australia, but was forced to turn back by the two fearsome deserts he discovered, the Sturt Stony Desert and the Simpson Desert. On the way back, the whole expedition suffered terribly; the second-in-command, James Poole, died of scurvy, and John McDouall Stuart took his place, though he was afflicted, too. By 1845 the southeastern quarter of the continent, the most habitable part, had been completely explored; now the real challenges would begin.

The exploration of inland South Australia began with a young immigrant named Edward John Eyre, who came to Australia when he was seventeen years old, learned to raise sheep, and made his first fortune by bringing a herd of 1,000 sheep and 600 cattle overland from New South Wales and selling them for a profit at Adelaide. For his first expedition, in 1839, he and five other men explored the land on all sides of Spencer Gulf; from the northernmost point they reached (soon to be named Mt. Eyre), Eyre spotted a salt lake, Lake Torrens. A month after returning to Adelaide, Eyre went forth again, following the south coast for about 300 miles, from Port Lincoln to Streaky Bay. In 1840 he led a third expedition northwards, and made it just fifty miles farther than he had the first time, before a shortage of supplies made him turn back. At the turnaround point, he climbed a hill and all he saw from the top was barren land, a salt lake and broken ridges. From this he incorrectly thought that Lake Torrens was a large, bow-shaped lake that blocked all progress past that point, so he named the hill “Mount Hopeless.” Actually he was looking at another lake, which is now called Lake Eyre; he had missed the path between Lake Torrens and Lake Eyre.

However, this wasn't the end of his adventure; this was only the beginning. Eyre sent most of the expedition home and chose to go west with only himself, his friend John Baxter, and three aborigines, figuring that the supplies would last longer if fewer men were consuming them. Now his goal was to follow the southern coast, exploring as much of the land bordering the “Great Australian Bight” as possible. As they went along, they found no standing water and the summertime heat was great; they survived by using aboriginal techniques to get water, either from the morning dew on grass or by digging for it. However, most of the sheep and horses died on the way, forcing them to abandon more of their supplies.

One night in April 1841, two of the Aborigines stole all the supplies they could carry and ran away; Baxter woke up, caught them in the act, and the thieves shot him dead. Eyre was now in a really bad situation; he feared the Aborigines might kill him as well, and did not know if he could trust Wylie, the Aborigine who had stayed loyal. The ground was too rocky to bury Baxter, so Eyre and Wylie wrapped the body in a blanket (more than eighty years later, another expedition found Baxter's bones, and a memorial was erected in his honor on the spot). All they had left to live on was some water and flour that had not been taken, and because they had gone more than halfway from Adelaide to Albany, they decided to keep going instead of turning back.

What made the journey even worse was that winter had arrived, and they couldn't keep warm because they had thrown away most of their clothes already, to lighten the burden on their horses. At one point they ate a diseased horse, which made them sick for days. When they were down to their last spoonful of flour, they came upon a bay where a French ship, a whaler named the Mississippi, had dropped anchor. The ship captain was an English-born gentleman named Thomas Rossiter, and for two weeks he let the two explorers rest and recover with his crew; Eyre thanked him by naming the place Rossiter Bay. Finally in July 1841, Eyre and Wylie made it to Albany; they had traveled nearly 2,000 miles across a waterless land.