| The Xenophile Historian |

|

The Anglo-American Adventure

Chapter 7: THE GREAT WHITE NORTH, PART II

Canada since 1867

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| The Story So Far | |

| Early Canadian Politics, and the Mapleleaf Flag | |

| The Original Provinces | |

| The Red River Rebellion | |

| British Columbia and Prince Edward Island Enter the Dominion | |

| The Northwest Rebellion | |

| The Laurier Years | |

| The Klondike Gold Rush | |

| Here Come Alberta and Saskatchewan | |

| World War I, the Conscription Crisis, and the Unionists | |

| The Mackenzie King Era | |

| The Dominion of Newfoundland |

Part II

Postwar Canada

Canada's industry and people were able to make a smooth transition back to peacetime activities after World War II ended. However, because Canada had matured as a nation since the twentieth century began, it was now expected to play a more active role in world affairs than it had before. Consequently Canada became a charter member of both the United Nations and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Because the British gave away their empire in the postwar era, Canada's policy was to act as a partner of the United States. For example, Canada sent 27,000 men to fight alongside the Americans and South Koreans in the Korean War. And because of Canada's geographic location, on the other side of the Arctic from the Soviet Union, Soviet threats to the United States threatened Canada as well, so Canadians and Americans worked together on matters of common defense, especially through the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD).

In 1948 Mackenzie King was persuaded to retire, and his Secretary of State for External Affairs, Louis St. Laurent, succeeded him as both Liberal Party leader and prime minister. St. Laurent followed a fiscally conservative policy; taxation continued at wartime rates, and when that produced a budget surplus, he used it to pay off debts accumulated by the government during two world wars and the Great Depression. What was left over after that went to a modest increase in social programs, and the three projects listed below: the Trans-Canada Highway, the St. Lawrence Seaway, and the TransCanada Pipeline. In 1949 St. Laurent and the Liberals were re-elected in a landslide, using the slogan "You never had it so good."

Construction on the Trans-Canada Highway (TCH) began in 1950; it officially opened in 1962, and was completed in 1971. This is not one road but a network of roads across all ten provinces, identified by signs showing a white maple leaf on a green background. One stretch of the TCH is 4,990 miles long, making it one of the world's longest roads.

The St. Lawrence Seaway is a series of locks and canals in Quebec, New York and Ontario, used to make the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes accessible to seagoing traffic. In Chapter 3 we looked at an early effort to tame those waterways, the Erie Canal, and another, the Welland Canal, was built through Ontario later in the nineteenth century, to get around Niagara Falls. Upstream, the Soo Locks did the same thing for the St. Marys River, between Lake Superior and Lake Huron. However, these canals and locks were too small for twentieth-century shipping, so railroads had taken over much of the freight traffic since then. The St. Lawrence Seaway was built to remedy this imbalance. Costing $470 million US dollars and $336.2 million Canadian dollars, it was opened in 1959; Queen Elizabeth II and US President Dwight D. Eisenhower attended the opening ceremonies. Unfortunately, the Seaway also made the Erie Canal obsolete, and it is one of the reasons why the economy of upstate New York, especially Buffalo, has declined since the 1950s.

The TransCanada Pipeline transports natural gas from fossil fuel-rich Alberta to the provinces in the east, and until the Soviet Union built a pipeline from Siberia to Western Europe in the 1980s, it was the longest natural gas pipeline in the world. As with the Canada Pacific Railroad, the toughest part of the pipeline to build was the part across the Canadian Shield (see footnote #10), so Parliament debated whether to build an all-Canada route, or a cheaper one that cut across the northern US. The all-Canada route won out, for the same reasons as the railroad route, though it meant blasting with dynamite for the Canadian Shield leg. However, the decision was made with some questionable parliamentary moves. The Liberal Party leadership tried to force closure on debates by June 6, 1956, so that both funding and construction could begin by July 1; they figured that delays in funding past that date would delay construction for a year, and cause support for the whole project to fail. Parliament did meet the deadline, and the pipeline was finished on schedule (1958), but the politics behind the project, which received much coverage in the media, did not look democratic to the voters. This convinced many that the Liberals had grown arrogant, out of touch with their countrymen, leading to their electoral defeat in 1957.

Finally, it is worth mentioning another step in the progress of Canada's independence from Britain; in 1952, Charles Vincent Massey became the first native-born Canadian to be sworn in as governor general.(25) All previous governors general had come from the British nobility; the most recent was General Harold Alexander, the World War II hero. Prime Minister St. Laurent had recommended Massey because he had been chairman of the Royal Commission on National Development in the Arts, Letters and Sciences; his work there eventually led to the creation of National Library of Canada and the Canada Council of the Arts.

The Conservatives Return From the Wilderness--But Not For Long

We haven't seen the Conservatives for a while, because they were out of power from 1935 to 1957. They changed their name to "Progressive Conservative" in 1942, when John Bracken, the long-time premier of Manitoba, was picked by senior Conservatives to lead the party; they chose him because he did not currently hold a seat in Parliament, and had run a non-partisan government in his province. Because he had previously been a Progressive, Bracken asked that "Progressive" be added to the party's name before he took the job. However, most former Progressives continued to support the Liberal Party or the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, another leftist third party that had replaced the Progressives in the 1940s. Many Canadians continued to call the right-of-center party "the Conservatives," leaving out "Progressive," and Bracken was replaced in 1948, after he proved to be a listless leader. Still, "Progressive Conservative" remained the party's official name for the rest of its existence.

Prime Minister St. Laurent was confident that the voters would re-elect his government, because it was full of experienced men and the country was still prospering. Therefore he called an election in 1957, though he could have waited another year before the constitution required one. However, the Progressive Conservatives had a fiery new leader, John Diefenbaker. Before going into politics, Diefenbaker had become known as one of the most successful lawyers in Canada. His best known case occurred in 1950, when a telegraph operator named Jack Atherton was accused of sending an incomplete message, causing a wreck of two trains at Canoe River, British Columbia, and killing twenty-one soldiers on their way to Korea. Diefenbaker volunteered to defend Atherton, and did it so powerfully, that the jury only took forty minutes to vote "not guilty."

Now in 1957, Diefenbaker's personality, plus the previously mentioned pipeline debate and a general weariness with Liberal rule, gave the Progressive Conservatives an advantage they did not have previously. Campaigning in Quebec looked hopeless for them, because that was the incumbent prime minister's home province and the party had previously alienated French Canadian voters, so they concentrated their efforts in the other provinces. The strategy worked: the Liberals held onto their seats from Quebec, Newfoundland and the territories, while the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation won in Saskatchewan, the Social Credit Party (a right-wing political movement) won seats in Alberta and British Columbia, and the Progressive Conservatives carried the rest of the country. Of the 265 parliamentary seats, nobody had a majority, but the Progressive Conservatives won 112 to the Liberals' 105. Although more people cast ballots for Liberal candidates than Progressive Conservative ones, the Liberal voters were concentrated in Quebec, where they did not make a difference; St. Laurent retired instead of fighting for his job, and Diefenbaker became the next prime minister.

John Diefenbaker was the first prime minister of neither English or French ancestry, and because he had spent most of his life in Saskatchewan, he gave both ethnic minorities and western Canadians a strong voice they didn't have before. However, he felt restrained as long as he ran a minority government, and wanted a new election to come quickly and give his party a solid majority. He got it sooner than expected because his new opponent, Lester Pearson, had worked wonders as a UN diplomat, but was inexperienced at any job that required leadership. Four days after taking charge of the Liberal Party, Pearson announced that the economy was headed for trouble, and rashly called on Diefenbaker to resign, so that a Liberal government could handle the problem. Diefenbaker responded with a devastating two-hour speech, in which he read a report from a year earlier that warned of a coming recession; the Liberals had ignored that warning, and simply promised more prosperity.

Now that he had an excuse for the snap election he wanted, Diefenbaker called for it. In the campaign that followed, he excited the voters by talking about "One Canada" for everyone, and announced that just as his predecessors had developed the eastern and western parts of the country, so he would begin to develop the resources of the north. Against this, Pearson ran a disorganized campaign, that did little besides complain that the election should not have been held in February 1958 (winter weather made it difficult to travel to polling places), and promise more of the government programs that the Liberals were known for already. When Pearson realized that the Liberals were going to lose, he hoped to save at least 100 seats, but they could not even hold on to half of those. The result was the most overwhelming Conservative victory of the twentieth century: 208 seats for the Progressive Conservatives, 48 for the Liberals, and 8 for the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. Even in the Liberal stronghold of Quebec, the Progressive Conservatives won by 2 to 1; six provinces did not elect any Liberals at all. At last Diefenbaker had the powerful mandate he had been seeking.

As it turned out, the former Saskatchewan lawyer, now nicknamed "Dief the Chief," could not deliver all that he had promised. Soon after the 1958 election, the predicted recession began, and unemployment rose. Disagreement with the United States over how to handle Cuba ended up annoying the Americans, and so did an unsuccessful attempt to reduce trade with the United States by increasing trade with Europe. Diefenbaker also managed to irritate his British counterpart, Harold MacMillan, when he became such a strong opponent of apartheid that he persuaded South Africa to leave the British Commonwealth in 1961. On a positive note, Diefenbaker's government appointed the first female Cabinet member, passed the Canadian Bill of Rights (previously, rights like freedom of speech and freedom of religion had not been specified in federal law or the constitution), and gave Native Americans and Inuit the right to vote. The most controversial decision was the cancellation of the program to build the Avro CF-105 Arrow, a Canadian supersonic fighter; instead, Canada would buy its warplanes from the United States.(26)

Meanwhile, the Liberals got their act together, winning back their base of support. In the 1962 election, the Progressive Conservatives remained ahead of everybody else, but with just 116 seats, they went back to being a minority government.(27) The next year saw the prime minister unable to decide whether to allow nuclear warheads on Canadian missiles, which was required by Canada's commitments to NORAD and NATO. This led to a rift with the United States; Canada recalled its ambassador from Washington (the first time that had happened in US-Canadian relations), the Defence Minister resigned, and Diefenbaker failed to stop a no-confidence motion. New elections were called, and this time the Liberals won 129 seats, vs. 95 seats for the Progressive Conservatives. This was five seats short of a majority, but by forming a coalition with the New Democrats (see the previous footnote), the Liberals won the right to form the next government, under Lester Pearson. Diefenbaker, now the opposition leader, ran the Progressive Conservatives for four more years; once out of office he regained his old campaigning skills, and it is because he used them well after the 1963 defeat that his party managed to survive at all.(28)

Though Pearson never had a majority government, he introduced much of the social legislation that Canada is known for today. We mentioned one accomplishment, the replacement of the Red Ensign with the Maple Leaf flag, earlier in this chapter. Also passed were universal health care, the Canada Pension Plan and Canada Student Loans, the 40-hour work week, a two-week vacation every year and a new minimum wage. In 1965 he signed the Canada-United States Automotive Agreement, which allowed the free trade of cars, trucks, busses and their parts between the two countries.

Overall US-Canadian relations were probably never better than they were during the Pearson administration, but there was one rough spot, caused by the Vietnam War. Canada was willing to get involved in actions against nations that caused illegal acts of aggression, as North Korea did when it invaded South Korea, but unlike the United States, it wasn't interested in fighting communism on every front. When US troops went to fight in Vietnam, Canada turned down American requests to participate. Then on April 2, 1965, Pearson visited Temple University in Philadelphia, and recommended that the US stop bombing North Vietnam, so that there would be a chance to end the war through diplomacy. The US president at the time, Lyndon B. Johnson, was never one to hide his feelings (see Chapter 5, footnote #53), and he thought it was very rude for a foreign guest to criticize US foreign policy while on US soil. According to one story, which may or may not be true, Johnson summoned Pearson to Camp David before Pearson was done with his speech. Pearson arrived at Camp David the next day, and Johnson, who was a much larger man, grabbed him by the lapels, shook him, and shouted, "Don't you come into my living room and piss on my rug." All Pearson said about the meeting afterwards was that it ended cordially, though it did not begin that way. Canada did not commit its armed forces to Vietnam, though 30,000 individual Canadians volunteered their services by joining the US military.(29) However, the Canadian government found peacekeeping activities more to its taste; Canada was one of the five countries that sent troops to patrol South Vietnam after the 1973 cease-fire (the others were Hungary, Indonesia, Iran and Poland). Canada also made a profit during the war, by selling raw materials that the US military machine needed.

Pearson had the good fortune to be prime minister when Canada celebrated its 100th birthday on July 1, 1967. The main event for the centennial was a world's fair in Montreal, called Expo '67; the same year saw the fifth Pan-American Games held in Winnipeg.(30) However, there was also an international incident during the centennial that let Pearson know how President Johnson must have felt. The governor general, Georges Vanier, had died earlier that year, and Canadians noted that France had sent no official representative to his funeral, though Vanier and French President Charles de Gaulle had been friends since 1940. Then when de Gaulle came on an official visit in July, he did not go first to Ottawa, like most foreign leaders did, nor did he head directly to Expo '67, which was the stated purpose for the trip. Instead, his first stop was Quebec City, and the crowd that came to see the famous French leader was so enthusiastic, that he decided to make a speech endorsing the budding separatist movement in Quebec. The speech was supposed to end with two inoffensive cheers, "Vive Montréal! Vive le Québec!" (Long live Montreal! Long live Quebec!), but de Gaulle added three more cheers that showed his real sentiments: "Vive le Québec libre! Vive le Canada français! Et vive la France!" (Long live free Quebec! Long live French Canada! And long live France!). From there de Gaulle went to Montreal, where he remarked that his procession in Montreal reminded him of his return to Paris, after it was freed from the Nazis in 1944. Then realizing that he had worn out his welcome, he spent just one day at Expo '67 before returning to France.

The Canadian government was not amused, to say the least. Pierre Elliott Trudeau, the new Minister of Justice, asked what the French reaction would have been if a Canadian prime minister visited France's Celtic community and shouted, "Brittany to the Bretons." Pearson, who had seen Canadians fight and die in two world wars to save France, responded to de Gaulle's Montreal speech by saying, "Canadians do not need to be liberated" and announced that de Gaulle was no longer welcome in Canada. But at the same time, Pearson recognized that Quebec had a genuine grievance, so he and his successors made some concessions, in the hope that French Canadians might believe this was their country, too. One of the first concessions was a 1969 ruling that made French an official language, alongside of English. Since then, Francophones have gained more power in the federal government, and every prime minister after Pearson was expected to be fluent in both English and French.

Three members of Pearson's cabinet went on to become prime ministers later. Here they are with their boss, in a 1967 photo. From left to right: Pierre Trudeau, John Turner, Jean Chrétien, Lester Pearson.

Pierre Trudeau, Part I

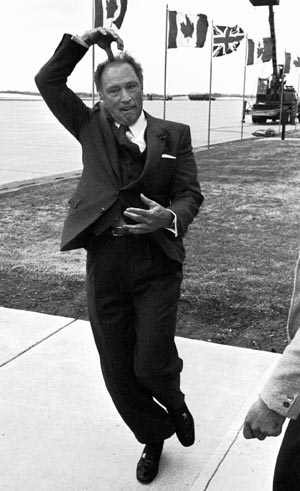

After the centennial festivities were done, Pearson announced his retirement, because he was now seventy years old. A leadership convention was held in April 1968, and it chose Pierre Trudeau to succeed him. Trudeau was only 48 years old, so he was seen as young and charismatic, compared with Pearson. The enthusiasm young voters showed for him was called "Trudeaumania" by the press, and led to suggestions that Trudeau would be a Canadian John F. Kennedy. The most flamboyant of Canadian prime ministers, he served from 1968 to 1984, except for a nine-month span in 1979-80. Canadians either loved him or hated him; while in the public spotlight, Trudeau made them feel every emotion except indifference. To start with, Trudeau's background in law and his reputation as an intellectual caused his admirers to see him as a "philosopher-king," but at the same time his self-confidence bordered on arrogance, and sometimes even made him look like an aristocrat. He was also known for his expensive tastes, vivaciousness, and for expressing his true feelings. As the British newspaper The Daily Telegraph put it, "He enjoyed dancing with pretty girls in fashionable night spots, and seemed more at home with Barbra Streisand and John Lennon than with a Nova Scotia party worker or a prairie farmer. He married a flower child half his age, treated the monarchy with near-contempt and, spouting sociology, made the doubting of ancient institutions seem acceptable."(31)

John Lennon and Yoko Ono met Trudeau in 1969. Trudeau was the only prime minister who gave Canada a strong voice on the world stage.

Trudeau once did a pirouette behind the Queen of England's back.

By the time Trudeau took over, Canada had more trade and defense agreements with the United States than with any other country. Consequently, a US decision in 1971 to put a 10 percent tariff on all imports upset the Canadian economy (the so-called "Nixon Shock"). Trudeau and Nixon hated each other, and Trudeau had previously felt Canadian-US relations were too close, so he responded with a speech that called for a "third Option," in which Canada would conduct its affairs independent of both the US and the UK.(32) This was a reversal of the pro-US stand previous Liberals had taken. However, such a policy was easier to applaud than to implement; Trudeau's efforts toward that were not very successful. For example, he liked to irritate the Americans by making friendly visits to the Soviet Union, Cuba and China. When he was expected to denounce communist atrocities like the Soviet invasions of Czechoslovakia (1968) and Afghanistan (1979), the Polish government's crackdown on the Solidarity labor union (1981), and the shooting down of Korean Airlines Flight 007 (1983), he did so with an obvious lack of enthusiasm. But this behavior made look like a communist sympathizer to the NATO countries, because he also tried to reduce Canada's commitment to the NATO force in Europe. After Trudeau, Brian Mulroney did not even try to distance himself from the Americans, so today more than 75 percent of Canada's trade is with the US. Since then, the stand politicians take on relations with the US has largely depended on which American party is in charge; e.g., Conservatives are pro-American when a Republican is president, while Liberals like Americans best when a Democrat is in the White House.

The Rise of Quebec Separatism

Trudeau's biggest challenge came not from the United States, but from the Quebec Separatist movement. For the past century, Anglophone Canadians had hoped their French-speaking neighbors would learn English and assimilate into the English-speaking majority around them. Instead, the Québécois stubbornly held onto their culture. In the nineteenth century, Quebec was able to keep its identity because the Québécois made a living from agriculture and lumber, largely ignoring the Industrial Revolution when it transformed the United States and Ontario. However, after 1900, hydroelectric power and the wood pulp industry were introduced to Quebec, and they made it possible to make a good income in parts of the province that weren't fit for farming. This led to new industries and new jobs in the cities, especially Montreal, so many people moved to the cities. By 1921 Quebec was Canada's most urbanized province, but only a few Québécois prospered under the new system, because the provincial government, taking a laissez-faire approach, encouraged the growth of industry without doing much to check its worst excesses. Consequently most of the new businesses paid low wages, and were owned by either Anglophone Canadians or US citizens. The resulting society mocked traditional values, and workers found themselves facing challenges in the factory that could not be solved with the Catholic, conservative solutions that had worked on the farm. However, the rulers of Quebec at this time were the Roman Catholic Church and a handful of business executives, not people likely to make changes. After World War II, the cities of Quebec saw the growth of an educated French-speaking middle class (this included Trudeau), which joined labor in looking to create a better society. Abroad, the breakup of colonial empires in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean, convinced many French Canadians that they had the right to self-determination, too.

The Union Nationale, a conservative nationalist party, was founded in Quebec in 1935. This was the first political party to rule the province that wasn't a branch of one of Canada's two major parties. For most of the following generation (1936-39 and 1944-59), Maurice Duplessis, the Union Nationale leader, was premier of Quebec. Today Duplessis is remembered for being a strong opponent of involvement in World War II, and for his reactionary, authoritarian rule. Duplessis died in 1959, and one year later, the Quebec Liberal Party, under Jean Lesage, won the local elections.

The new government launched a number of new legislative initiatives to get rid of the corruption from previous administrations, improve Quebec's infrastructure, remove the Church from non-Church activities, nationalize the power companies (which had previously been privately owned), and encourage more economic development. The changes in society were so dramatic, that the wave of Liberal activism in the early 1960s is sometimes called the "Quiet Revolution."(33) That ended in 1966, when the Liberals were voted out of office and the Union Nationale returned to power. However, by then the Quiet Revolution had also encouraged the development of more radical movements. A vocal minority of leftists raised demands that ranged from giving Quebec autonomy to full independence from the confederation; henceforth these leftists will be known as Quebec Separatists.

The most radical of the Separatists was the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ, Quebec Liberation Front in English), a Marxist paramilitary group founded in 1963, and inspired by the recent civil wars in Algeria and Cuba. More important, however, was the Parti Québécois (PQ), a nationalist party founded in 1968 by the merger of two older groups, and led by René Lévesque, a former member of the Quebec Liberal Party who quit after other members refused to discuss the idea of a sovereign Quebec at the party convention. The PQ first got to test its strength among the voters in the 1970 provincial election, where it ran under the simple slogan "Oui." How did that go? Not too good! Though the PQ won 24 percent of the popular vote, the electoral districts were drawn in an archaic fashion that gave only 7 out of 95 seats to them, and 72 seats (including Lévesque's) to the Liberals. Quebec would not secede before constitutional reform could be tried again.

The provincial flag of Quebec uses the fleur-de-lis emblem, making it look a lot like the flag France used when it ruled Canada (see below). Because it is also the symbol of the Quebec Separatists, the Québécois see this flag much like folks in the southern United States see the "Stars and Bars" (Confederate battle flag)--for them it is more popular than the national flag.

The FLQ chose terrorism, rather than the ballot box, as its main political tool. Like terrorists elsewhere, they inflicted bombings, bank robberies, kidnappings, acts of vandalism, letters containing death threats, and at least five murders. Usually they simply stuck bombs in mailboxes, but a 1969 attack on the Montreal Stock Exchange injured twenty-seven people; this also showed the FLQ wanted Quebec to abandon capitalism as well as Canada. Over the course of the 1960s, the attacks were not as common as in other hot spots like Northern Ireland, but they succeeded in creating an atmosphere of fear--which is why it's called terrorism.(34)

Most Canadians--French as well as English--did not believe violence was the answer to Quebec's problems, and felt the FLQ's behavior was "un-Canadian." Though a French Canadian himself, Trudeau did not see a future for Quebec if it left Canada. Neither did the current premier of Quebec, Robert Bourassa. Then in October 1970 the conflict suddenly escalated into the "October Crisis," when the FLQ kidnapped British Trade Commissioner James Cross, and Quebec's Minister of Labour, Pierre Laporte, from their homes. Bourassa and the mayor of Montreal asked the federal government for emergency powers to arrest anyone suspected of causing trouble, and Trudeau responded by invoking the War Measures Act, to do just that.

The War Measures Act had been on the law books since 1914, but aside from wartime measures during World War I & II, this was the only time it has been used. When asked how far he would go in putting down the uprising, and how long the emergency would be in effect, Trudeau simply said, "Just watch me." Tanks and soldiers moved into Montreal, helping the police to arrest 497 people without warrant, often just because they were sympathetic to the Separatists. The next day Laporte was found dead in the trunk of a car, after the FLQ sent a message to the police announcing they had executed the "minister of unemployment and assimilation."

The rest of Canada almost unanimously supported the government's tough action, though it meant several innocent people were among those detained. It was the people of Quebec, and the other political parties, aside from the Liberals, who called it excessive. For example, Tommy Douglas, the leader of the New Democratic Party, said, "The government, I submit, is using a sledgehammer to crack a peanut." Others panicked, and called it an imposition of martial law, though technically it wasn't because the military and the government were in agreement all the time. Two months later James Cross was released, after a negotiated settlement where the government granted safe passage to Cuba for five FLQ leaders. The FLQ fell apart once its leaders were gone, suggesting that it never had the resources or manpower for a long campaign against the government; meanwhile, most of those arrested were released. Even the guilty got off easier than expected; the kidnappers sentenced for killing Laporte were all paroled by 1982, and those who fled to Cuba were eventually allowed to return.

The first elections after the October Crisis were held in October 1972. No party won a majority, and Trudeau kept his job with the same strategy his predecessor had used--he persuaded the New Democrats to support the Liberals, and gained a majority that way. Elections were held again when high inflation and a withdrawal of New Democrat support caused the government to fall in 1974. This time the Liberals won a majority of seats, allowing Trudeau to rule without anyone else's help.

The Quebec Separatists made themselves heard again when they elected René Lévesque premier of the province in 1976. Other Canadians panicked at the thought that the Separatists could now legally carry out the breakup of Canada they had threatened for the past decade. The Parti Québécois followed up its victory with a controversial law called the Charter of the French Language, which made French the official language of the province, changed English place names and cut back on instruction in schools that used any language besides French. In 1980 a referendum was introduced, asking the voters if Quebec should pursue a path to sovereignty, and 60 percent of them voted "Non!" That took the wind out of the PQ's sails, and though it wasn't voted out of office until 1985, it stopped making moves toward independence. After that the PQ opposed the 1982 constitution, because it included a provision for freedom of language in education, and unsuccessfully sought the right to unique powers and status after the constitution went into effect; then in 1984 the Supreme Court ruled against Quebec's schooling restrictions.

Pierre Trudeau, Part II

The rest of the 1970s was not a happy time for Trudeau. As in the United States, the economy did poorly for the whole decade. In 1975 he introduced wage and price controls to curb inflation, which made him look hypocritical because he had ridiculed the Progressive Conservatives for proposing the same solution during the last election. Despite this, prices, interest rates, the national debt and unemployment all soared out of control during his administration. The national debt rose from $18 billion in 1968 to $200 billion in 1984, while unemployment was at 4% when he took office, rose as high as 12%, and had only dropped to 11% by the time he retired--and this happened while the US economy was booming under Ronald Reagan. Even his marriage ran aground. For the first few years after they got married in 1971, Margaret Trudeau was not very visible, because she was busy raising the couple's three children.(35) After that, however, she grew tired of her husband's workaholic behavior, and embarrassed him with her attention-getting stunts. She once smuggled drugs in the prime minister's luggage; she danced at the famous nightclub Studio 54, even on the night her husband lost the 1979 election; rumors flew of Margaret having possible affairs with Fidel Castro, US Senator Teddy Kennedy, Geraldo Rivera, and Ron Wood of the Rolling Stones. The Trudeaus separated in 1977, and got a divorce in 1984.

Besides all the stuff in the previous paragraph, a lot of Canadians had grown tired of Liberal rule, after sixteen years of it. When the 1979 election came around, the Progressive Conservatives won more seats than the Liberals, and Joe Clark, a former MP from Alberta, became the youngest prime minister in Canadian history (he was sworn in one day before his 40th birthday). However, Clark never really got a chance to prove himself. Saddled with a minority government, and distrusted because of his lack of experience, he lost a no-confidence motion before the year was over, forcing a new election in 1980. Trudeau had resigned as head of the Liberal Party after losing in 1979, but the party never got around to choosing his replacement (that required a leadership convention), so he quickly rescinded his resignation before the election. This time the Liberals won a majority of seats, allowing Trudeau to return as prime minister.(36) However, the results also showed an ominous east-west split in voting patterns. The Liberals won all but two of Quebec's 75 seats, and got a comfortable majority in Ontario, but the three westernmost provinces, which felt unappreciated by the federal government, did not send a single Liberal to Parliament.

The Trudeau of the 1980s was grayer and more subdued than the Trudeau seen previously. First he led the massive ad campaign that persuaded Quebec's voters to reject the 1980 Quebec referendum. This success encouraged him to try something that other prime ministers had talked about for fifty years, but never succeeded in doing--write a new Canadian constitution. The first constitution had been written by the British, as part of the 1867 British North America Act, and Canadians understandably felt that a constitution written by themselves would be much better. Through a series of meetings with the premiers of the provinces, Trudeau was able to put the finishing touches on a document that was acceptable to every province except Quebec. Meanwhile in London, Canadian High Commissioner Jean Wadds met with British leaders like Margaret Thatcher. There were some sensitive moments when Native Americans and Inuit went to London in traditional dress to make an appeal to the Queen against the constitution, but in the end Trudeau had his way. On April 17, 1982, Queen Elizabeth went to Ottawa and signed the Constitution Act, giving Britain's approval to Canada's new law of the land.

The document produced by the Constitution Act was not really a new constitution so much as an amended version of the old one. The main difference was that previously the constitution did not have a bill of rights, so Trudeau threw one in, calling it the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Still, it was enough for Trudeau's ultimate goal, the complete transfer of constitutional powers from London to Ottawa. Except for the Queen's status and Canada's membership in the Commonwealth, the last legal ties between Canada and the United Kingdom had been cut.(37)

Curiously, the term "Dominion" disappeared from the Canadian political vocabulary after the Constitution Act was signed. It wasn't outlawed, it just went out of use. For example, the name of Canada's July 1 holiday was changed from Dominion Day to Canada Day in 1982, and the government stopped using the title "Dominion of Canada" a generation earlier, when Louis St. Laurent was prime minister. Since then the nation's official name has just been "Canada," with no "Dominion," "Republic," or any other word in the title to describe it. Usually when asked, the explanation given is that "Dominion" reminds Canadians too much of the old days of colonialism and British imperialism; it has also been pointed out that there is no word in French meaning exactly the same thing.

Unfortunately for Trudeau, his success with the constitution could not be applied to the economy. The energy crises of the 1970s prompted him to look for a way to gain control over Canada's energy industries, so he introduced the National Energy Program (NEP) in 1980. The purpose of this was to tax domestically produced oil and gas, keep the price of domestic oil below that of imported oil, make the nation self-sufficient on energy, and promote alternative energy sources that would produce less pollution.

The province most affected by the NEP was Alberta, which not only had 80 percent of Canada's natural gas, but also the second largest source of oil in the world, only exceeded by Saudi Arabia. This was the Athabasca Tar Sands, a deposit in northeastern Alberta that is estimated to contain hundreds of billions, possibly even more than a trillion barrels of oil. The existence of the oil had been known for two hundred years (explorers like Alexander MacKenzie reported deep pools of bitumen when they passed through the area), and oil production in the Athabascan region started in 1967. However, the process of separating the oil from sand is more expensive than drilling and pumping conventional oil wells, so it wasn't until after the price of oil started rising in 1973 that extraction became cost-effective; then the rest of the world realized the full potential of Alberta's oil.

The federal government assumed that oil prices would keep going up, and that new taxes on oil and gas would help solve the budget deficit problem. But because the NEP forced western Canada to sell its fossil fuel for a lower price than it could get on the world market, the program was extremely unpopular; some Albertans, like the Québécois, talked about seceding from Canada to stop the rip-off. While the NEP was in effect, Alberta lost an estimated $50 to $100 billion, and Trudeau has been hated there ever since. Then in the mid-1980s, falling oil prices made it impossible for the oil industry to turn a profit while the government was interfering, so after the 1984 election, the NEP was scrapped. Today the western provinces, especially Alberta, still distrust the government in Ottawa because of bad memories of the attempt in the 1980s to nationalize the oil companies.

As the economy and the NEP collapsed, so did Trudeau's approval ratings. In early 1984 he realized the Liberals would be sure to lose the next election if he continued to lead them, so after a "long walk in the snow" on February 29, he announced he would resign. John Turner, a rival of Trudeau, took his place the following June.(38) However, Turner proved to be a Liberal Joe Clark, only holding the job of prime minister for seventy-nine days. The Progressive Conservatives had a new leader, Brian Mulroney, and the voters were mad at Liberal corruption, so Mulroney assembled a base of support that put him ahead in every province and territory. Even Quebec preferred Mulroney over Turner, because Mulroney was born in Quebec, though he was Irish rather than French, while Turner came from Vancouver. A debate between the candidates was a smashing victory for Mulroney, which left Turner looking weak and incapable of doing anything besides continuing Trudeau's policies. When the election took place, in September 1984, it was the worst defeat the Liberals ever suffered; the Progressive Conservatives won 211 of Parliament's 282 seats (a three-fourths majority!), compared with 40 for the Liberals and 31 for the New Democrats.(39)

The Turner-Mulroney debate (Mulroney is on the right).

Neo-Conservatism, Canadian Style

The 1980s saw a neo-conservative trend in many countries, as a reaction to the activist governments they had in the 1960s and 1970s. In the United States it produced Ronald Reagan, in the United Kingdom it produced Margaret Thatcher, and in Canada it produced Brian Mulroney.

In terms of foreign policy, Mulroney took a somewhat more moderate stand than Reagan and Thatcher. He was a strong opponent of apartheid in South Africa, whereas the American and British governments were willing to cut South Africa some slack. He also opposed US intervention to support the Contras, the rebel movement in Sandinista-controlled Nicaragua, and allowed Canada to take in refugees from Central American conflicts; moreover, Canada was the first Western nation to send emergency aid those starving in communist-controlled Ethiopia, during their famine in the mid-1980s. Aside from that, though, Mulroney, Reagan and Thatcher made a companionate threesome.(40)

Mulroney's first big challenge was finding experienced people who were not of the Liberal persuasion to serve in his Cabinet, because the Liberals had been in charge for 51 of the past 63 years. Cutting the deficit was his main priority, but as was the case with Reagan, the national debt continued to rise, albeit not as quickly as it would have under a Liberal government. He also placated the west by phasing out the National Energy Program, as we mentioned previously. Next on the agenda came two important initiatives, which he negotiated in 1987. The first, the Meech Lake Accord, defined Quebec's status, declaring it a "distinct society" and transferring several powers from Ottawa to all provinces. The House of Commons in Parliament ratified the accord in 1988, but it also needed to be approved by every province; Quebec said it would finally accept the 1982 constitution if the Meech Lake Accord passed. The other initiative was a Free Trade Agreement, that would eliminate all tariffs between Canada and the United States. Mulroney and Reagan completed work on the Free Trade Agreement in 1988, but both the Liberals and New Democrats opposed it so strongly that Mulroney had to schedule an election for the same year. In effect, the election was a popular referendum on the Free Trade Agreement, and it went into effect after Mulroney was re-elected with another majority government. Afterwards the Agreement was enough of a success, that Mulroney negotiated a more extensive one, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), during his second term.(41)

Unfortunately, the Meech Lake Accord failed in the provinces, meaning that Mulroney's track record was the opposite of Trudeau's: he did well with the economy but not with the constitution and Quebec. What killed the Meech Lake Accord was that the legislatures of two provinces, Manitoba and Newfoundland, did not ratify it before the deadline (June 23, 1990). However, the parties that had produced the Accord weren't ready to give up, so they spent the next two years working on another package of amendments to the constitution that would make it acceptable to all provinces. The new agreement was reached in Charlottetown, the capital of Prince Edward Island, in August 1992, so the amendments were called the Charlottetown Accord. This time the decision was made to hold a national referendum, so the voters, rather than the provincial and federal governments, would choose whether or not to accept the Accord. All three major parties, Native Americans, Inuit, Métis, and most of the English language media endorsed it. However, there also were a few key opponents, including former Prime Minister Trudeau and the Parti Québécois, and they successfully portrayed the Accord as a document written by elitists, for elitists. Mulroney's efforts to campaign for the Accord worked against it, because his luster had faded by this time. On Election Day (October 26, 1992) the voters rejected the Accord, 54-46. Consequently Quebec's Separatists got a new lease on life.

Meanwhile it was various Indian groups, and not the French Canadians, that were giving the government the most trouble. The most serious event was the Oka Crisis of 1990, and involved a an ancient property dispute between the Mohawk tribe and the white man, that had never been resolved. In 1989 the town of Oka, Quebec decided to go ahead with plans to expand a golf course from nine to eighteen holes, and to build sixty luxury condominiums, all on 55 acres of land that the Mohawks claimed was a burial ground of theirs; the Mohawk claim had been rejected in 1986 by the Office of Native Claims, an agency with the federal government. Before construction could begin, though, the Mohawks set up a barricade to block the project, and ignored an order from the mayor to remove it. On July 11, 1990, one hundred members of Quebec's police force, the Sûreté du Québec (SQ), attacked the barricade, using tear gas and stun grenades. They got the worst of it; the wind blew the tear gas back in their faces, and a gun battle followed between them and the Mohawks, in which one police officer was killed.

For the next eleven weeks there was a standoff in Oka between the Mohawks and the authorities. In other parts of Canada, Native Americans acted to show their solidarity with the Mohawks. They blockaded the Mercier Bridge, one of the four main bridges into Montreal, and three highways in Quebec, causing major traffic jams. Other groups blockaded railroads in Ontario and in British Columbia; five electricity transmission towers were toppled in southwest Ontario; a Canadian National Railway bridge was burned down; the Peigans, a Blackfeet nation in Alberta, diverted the course of the Oldman River, to protest the construction of a dam that would destroy their lands. In August, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police were sent to Oka, but they did no better than the SQ; mobs caused by the Mohawks and blocked traffic put ten Mounties in the hospital. Finally, the army was called in, and the Mohawks were forced to surrender in September. The mayor of Oka defused the situation by canceling the golf course expansion, and the First Nations Chiefs of Police Association (FNCPA) was created in 1992, to prevent future crises by coordinating the various Aboriginal police forces.

Mulroney's economic policy was undermined by a worldwide recession at the end of the 1980s. He tried to keep control over spending by introducing a new sales tax, the Goods and Service Tax (GST). This was very unpopular; polls showed up to 80 percent of Canadians opposed to the tax. Mulroney had to stack the Senate with supporters in order to get the bill past them, and it went into effect on the first day of 1991. South of the border, U.S. President George H. W. Bush had also raised taxes, and the result was the same in both countries; Bush was not re-elected, while the coalition which had brought Mulroney victories in 1984 and 1988 broke up. By early 1993, Mulroney's approval ratings were so low that he chose to resign, because an election was due for that year and he didn't want to drag the Progressive Conservative Party down with him. His Minister of National Defence, Kim Campbell, was chosen to succeed him in June, becoming Canada's first female prime minister.

Political Uncertainty in the 1990s

Kim Campbell probably took over too late to save the Progressive Conservatives. Will Ferguson, a Canadian humorist, said that "taking over the party leadership from Brian [Mulroney] was a lot like taking over the controls of a 747 just before it plunges into the Rockies."(42) The electorate found her a bit too honest when she predicted that the deficit and unemployment would not be reduced much before the "end of the century," and she refused to discuss the overhauling of Canada's social policies, because she felt she could not do justice to that issue, in a campaign that lasted only forty-seven days. Moreover, the media portrayed Campbell unfavorably in news stories, for reasons it never made clear (they may have thought she would continue Mulroney's policies). Finally, two new political parties appeared, both made up of former Mulroney supporters: the Bloc Québécois and the Reform Party of Canada (no connection with Ross Perot's Reform Party in the United States). Finally, the Liberals did a better job of campaigning than the Progressive Conservatives did.

The result was a rout in October; instead of the Liberals winning with enough seats to form a minority government, as was expected, they got a 177-seat majority. The Liberal Party leader, Jean Chrétien, would be the prime minister for the next decade. The two new parties came in second and third place; the Bloc Québécois won in Quebec by a big margin, though Chrétien was from there, while the Reform Party carried British Columbia and Alberta. Fourth place went to the New Democrats, who did badly because much of their support defected to other parties. The Progressive Conservatives, who had won the largest Parliamentary majority in Canadian history just nine years earlier, were reduced to just two seats, and they would never again be a major party.

The failure of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords prompted the Quebec Separatists to try breaking with Canada again. In 1994 they won Quebec's provincial elections, and put another referendum about Quebec's future on the ballot for 1995. This time, the referendum asked if Quebec should make a bid for independence, not just for "sovereignty," and if Quebec becomes independent, whether it should make a partnership offer to the rest of Canada. The first polls suggested that the referendum would fail at least as badly as the first one had, because the federal government and all national parties except the Bloc Québécois were against it. So were the Cree and Inuit tribes of northern Quebec, who threatened to secede from Quebec if Quebec seceded, so they could stay in Canada.

To counter all this, Lucien Bouchard, the leader of the Bloc Québécois, became the chief spokesman in favor of the referendum. Bouchard had special appeal as a suffering hero, because in December 1994, he almost died from necrotizing fasciitis ("flesh-eating bacteria"), and doctors amputated his left leg to save him. Thus, he appeared in public on crutches, generating sentiment for both him and his cause. As the campaign went on, the polls showed the difference between the "Oui" (Yes) and "Non" (No) voters narrowed, until during the last two weeks before election day, the difference was within the 2% margin of error, or the "Yes" faction was actually in the lead.

It probably wasn't a surprise when the 1980 referendum went down in defeat, but the results for the 1995 referendum were too close for comfort, whether you were for it or against it. Bouchard made plans to take control of all military bases and Canadian Air Force jet fighters in the province, should the referendum pass, as the first step in the creation of the Quebec armed forces. Instead, on October 30, 1995, the voters rejected the referendum by an extremely thin margin: 50.58% No, 49.42% Yes. As with the 2000 presidential election in the US, this required a recount, and it took months for the controversy to settle down; 86,000 ballots were thrown out because they were not marked properly, but the difference between the "Yes" and "No" votes was only 54,000, meaning that the discarded ballots could have decided the election.

Because the second referendum failed, Quebec is still part of Canada today, though not completely satisfied, and the provincial government continues to alternate between pro-separation and pro-Canadian premiers. One thing is certain: as long as they can do it legally, the Separatists will keep on submitting referendums calling for independence, or at least autonomy, until they get one passed.

The survival of French Canadians up to this day is no small accomplishment, after all the efforts by the British and Anglophone Canadians to assimilate them, but the stubbornness that kept them French may be holding them back now. Perhaps the best sign of this comes from immigration patterns; only 5 percent of the immigrants that come to Canada settle in Quebec. Consequently Montreal may be the largest Canadian city, but its population is mostly from one ethnic group; by contrast, the second and third largest cities, Toronto and Vancouver, revel in their ethnic diversity. And most of the immigrants that choose Quebec come from French-speaking parts of Africa and the Caribbean, not places known for producing rich, well-educated people. Figuratively, the Québécois may have preserved their heritage by surrounding themselves with a wall, but one wonders how different their fortunes would be if they had built a bridge instead?

Chrétien and the Liberals had no trouble winning re-election in 1997; the main result was that the Reform Party pulled ahead of the Bloc Québécois for a strong second-place finish, and thus became the official opposition party. Before the next election, in 2000, the Reform Party changed its name to the Canadian Alliance, in an effort to gather all conservatives under its banner, but the result was the same: the Liberals won again.

In 1999 the Northwest Territories were reorganized once more. This time the Districts of Mackenzie, Keewatin and Franklin were dissolved, and 60 percent of the land became the new territory of Nunavut, meaning "Our Land," with its capital at Iqaluit (formerly Frobisher Bay) on Baffin Island. The arrangement makes more sense from a geographical perspective, because the name "Northwest Territories" is no longer applied to places actually located in northeastern Canada (e.g., Baffin Island and Ungava Bay). It also makes sense from an ethnic perspective, because the north is now organized into three territories of almost equal populations, each dominated by a different ethnic group: the Yukon Territory for whites, the Northwest Territories for Athabaskan Indian tribes, and Nunavut for the Inuit.

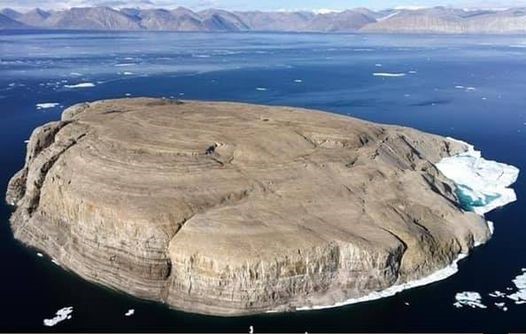

The creation of Nunavut left one issue unresolved, a very small issue -- literally! In the Kennedy Channel of the Nares Strait, between Ellesmere Island (Canada's northernmost island) and Greenland, there are three barren islands: Franklin, Crozier and Hans Island. Nobody lived there, though Inuit from both Canada and Greenland would go there to hunt and fish. Because Greenland is a territory of Denmark, the Danes claimed all three islands, but because Hans Island, the smallest of the three, is right in the middle of the waterway, Canada put forth a claim to it, too. The Canadian claim to Hans Island (known as Hans Ø in Danish and Tartupaluk in Greenlandic) came from the sale of the Hudson Bay Company's land, from a hundred years earlier, which included Hans Island. In 1973 the question of who owned the island was referred to the United Nations, and both sides promised to resolve it without resorting to violence. And there the matter stood for another eleven years. Because Hans Island has an area of less than one square mile, and no valuable minerals, neither side saw it as worth fighting over.

Both sides kept their promise of no violence, so the struggle for Hans Island was a lighthearted affair, that has gone down in history as the "Whisky War." In 1984 Canada decided it needed to stake a physical claim, and Canadian soldiers were landed on the rock. They planted the maple leaf flag, buried a bottle of Canadian whisky, and then returned home. Well, Denmark's minister of Greenland affairs couldn't let such a provocation stand, so a few weeks later he went to Hans Island, removed the offending Canadian symbols, and replaced them with a Danish flag and a bottle of Copenhagen's finest schnapps. He also left a letter for the Canadians which read: "Welcome to the Danish Island." Over the following years, more Canadians and Danes came to leave items as proof that their country owned the island, and visitors reported an accumulation of tattered red and white flags and notes. And yes, each time the troops came, they drank the liquor left by the previous group. Finally, surveyors drew a line following a ridge, that divided the island in two, and both sides agreed to share the island this way, on June 14, 2022. Since it happened a few months after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, this solution became an example of how territorial disputes can be settled peacefully.

|

|

Here is Hans Island, all of it!

The other geographical changes since 1999 have only involved names. In 2001 Newfoundland was renamed Newfoundland and Labrador; in 2003 the Yukon Territory became simply Yukon.

Click here for an animated map (opens in separate window), showing the evolution of Canada's

provinces and territories. From Wikimedia Commons.

![]()

Recent Events

Most of the world sympathized with the United States when it became a victim of history's worst terrorist attack on September 11, 2001.(43) One month later, the United States and NATO went into Afghanistan, to catch the Al Qaeda perpetrators, and Canada committed troops to fight alongside its allies. The first Canadian soldiers arrived in early 2002, and at the time of this writing, there are 2,830 Canadians stationed there. However, Canada refused to participate when US President George W. Bush opened up a second front in Iraq, putting a strain in US-Canadian relations. Consequently the "Coalition of the Willing" included the Americans, British and Australians, but not the Canadians; that looked a little odd for those who remembered the times when all four nations were on the same side.

Meanwhile, Chrétien announced in 2002 that he would not seek a fourth term as prime minister, so a year later he stepped down and handed over his job to a rival, former Finance Minister Paul Martin. In June 2004, an election was held to confirm the new prime minister. Fears that Martin would inflict a defeat severe enough to obliterate both right-of-center parties encouraged the Canadian Alliance and the Progressive Conservatives to unite, forming a new Conservative Party. Stephen Harper, a former Reform Party MP, became the Conservative Party's first leader. On the left, the Green Party entered candidates in all 308 races for the first time in its history, and though none of them were elected, the Green Party got 4.29% of the popular vote, suggesting that it may become a major party in the near future. Martin was re-elected, but the Liberals only got 135 seats this time, meaning they had lost their majority in Parliament. Because there are currently four major parties instead of two, all governments elected since 2004 have been minority ones.

In 2005, a scandal involving the misappropriation of government funds by the Liberal Party threatened the stability of the government, and forced new elections in January 2006. Martin was not implicated in the scandal, but Chrétien was accused of having his hand in it. With the 2006 election, the Conservatives won with 36% of the vote, and Conservative leader Stephen Harper took Martin's place as prime minister.

So far 140 Canadians have been killed in Afghanistan. Though that is just 1/7 as many casualties as the Americans have suffered, it's enough to generate antiwar sentiments, especially from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) and the New Democratic Party. When Pakistan's President Pervez Musharraf visited Canada, he told the CBC to stop complaining about Canada's war-related deaths, which were 40 at the time, compared with 600 for his country. As for the New Democrats, Afghan President Hamid Karzai put them in their place when he came to Canada; because the New Democrat leader, Jack Layton, wants to negotiate with the Taliban, Karzai refused to meet with him, despite several requests from Layton.

Unfortunately, Canada's biggest contribution to the War On Terror may be a family that works for the other side. Their patriarch was an immigrant from Egypt named Ahmed Said Khadr, usually called "al-Kanadi" because he was the highest ranking Canadian citizen in Al Qaeda, with ties to that organization going back as far as 1988. He was killed in a 2003 firefight between Al Qaeda, Taliban and Pakistani forces; however, his family has insisted that he was not a terrorist but only a relief worker, caught in the wrong place. Khadr's four sons also participated in the war. The eldest blew himself up in a suicide bombing that killed a Canadian soldier. The second son moved to Afghanistan in 2001, was captured by the Northern Alliance in Kabul, sent to Guantanamo Bay, was later released, and made his way back to Canada. He is now considered the "black sheep" of the family because he has denounced both Islamic extremism ("I want to be a good, strong, civilized, peaceful Muslim") and the radical politics of the other Khadrs. The third son killed a US Army medic with a hand grenade, was wounded and captured, and has been held at Guantanamo since 2002; he is currently the only citizen of a Western nation confined there. So far the Canadian government does not want him back, though several Canadians have called for his repatriation, because they want the Guantanamo prison closed. The youngest, though only fourteen years old, was left paralyzed in the same shootout that killed his father.

Naturally, the youngest Khadr wasn't likely to get good care in a Pakistani prison hospital, so al-Kanadi's widow brought her son back to Toronto, stating, "I'm Canadian, and I'm not begging for my rights. I'm demanding my rights." Incredibly, Prime Minister Martin let the Khadrs use the Canadian health care system, because it let him prove that like liberals elsewhere, he was tolerant of everything except intolerance. Ignoring demands that the whole Khadr family be deported, Martin said, "I believe that once you are a Canadian citizen, you have the right to your own views and to disagree."

In June 2006, police arrested seventeen suspected Islamist terrorists in Toronto, whom they had been monitoring for at least two years. Two months later they detained another suspect, giving this group the name "Toronto 18." The suspects were accused of plotting to blow up major targets inside Canada, with trucks carrying three tons of ammonium nitrate (the same weapon used in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing). In addition, they were accused of having plans to storm the Parliament building, take hostages, and behead the prime minister if they captured him. Most alarming was the fact that this was a home-grown plot; everyone accused was either a Canadian citizen or a legal immigrant. Since then one of the defendants has been convicted, four more have pleaded guilty, and the group's leader, after he also pleaded guilty, was sentenced to life in prison.

Among the Western nations, only France has shown more tolerance for radical Islam. The provincial government of Ontario once even considered putting local Moslems under Shari'a (Islamic law), instead of Canadian law. And we noted earlier that Canada opposes the war in Iraq and the indefinite detainment of captured enemy combatants at Guantanamo. The only reason Islamists might attack Canada is because they are notoriously intolerant of anyone who is not a radical Moslem like themselves. Osama bin Laden, for instance, once listed Canada with the United States, Britain, Spain and Australia as "Christian" nations that should become terrorist targets, until the people of those countries convert to Islam. Thus, the casual observer has to look at the behavior of Moslem extremists, going after a target that is neither American or Jewish, and say, "What a bunch of ingrates!"

A page from The Toronto Star, Canada's leading newspaper, after seventeen suspects in the 2006 terrorist plot were arrested. As you can see, the Canadian media, like the US mainstream media, is too politically correct to consider that religion might have motivated the plotters. Meanwhile, the rest of us note that while more than one nationality is represented among them, all attended services at the same mosque.

Unlike his predecessors, Harper does not believe in appeasing terrorists. During the 2006 conflict in Lebanon between Israel and Hezbollah, Canada was a strong supporter of Israel's right to defend itself. Under Harper, the Canadian government has also denounced Iran, cut off Palestinian aid because it was being diverted to Hamas, deported illegal immigrants, and refused to meet with Cindy Sheehan, the American anti-war activist. When Canada learned that the 2009 UN conference on racism was for racism, in the form of anti-Semitism, it became the first nation that refused to attend the conference, and cut off funding for non-governmental organizations that participated. Canada's example encouraged Israel, the United States, New Zealand, Germany, Italy, Sweden, the Netherlands, Poland and Australia to boycott the "Durban II" conference; forty other delegates walked out of the conference when Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad made a speech that attacked Israel's right to exist, and called the Jewish state a plot by Western nations to establish a racist government in the Middle East. Canada is now learning what the United States already knows, that leading a cause can be lonely, until others realize it is the right thing to do and follow the leader.(44)

In February 2007, Canada's Supreme Court struck down a law that permitted foreign terrorism suspects to be detained indefinitely without charges, while waiting for deportation. As Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin put it, "The overarching principle of fundamental justice that applies here is this: before the state can detain people for significant periods of time, it must accord them a fair judicial process." More recently, Prime Minister Harper has announced that Canadian troops have been in Afghanistan long enough, so he plans to withdraw most of them by 2011.

We have chronicled the efforts by the Canadian government to give Quebec special treatment since the 1960s, mainly to prevent Quebec from carrying out its threat to secede, but also because four recent prime ministers (Trudeau, Mulroney, Chrétien and Martin), ruling for a combined total of thirty-seven years, were Quebec natives. Harper did not need to do this, because he came from Alberta and the current premier of Quebec, Jean Charest, is against separatism, but he granted a concession to Quebec anyway. In November 2006 he got a motion passed in Parliament which declared that "the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada." The vote on the motion was 266-16, meaning that all the major parties supported it. Such a declaration was enough to make Premier Charest happy, but Quebec still has not accepted the 1982 constitution, which is probably Harper's ultimate goal.(45)

Harper was re-elected in the next election, held in October 2008. This time there were no major changes from 2006; the Conservatives are still in charge with a minority government. In fact, the voters had so little interest in the election that only 22 percent of them went to the polls. Still, it shows that a plurality of Canadians, if not a majority, agree with Harper's domestic and foreign policies. Barring any crisis, the next election is scheduled for 2012. Until then, it is too early to say if Harper is an aberration from the old pattern where the Liberals ruled most of the time, unless they made a big mistake, or if the current administration represents a true political paradigm shift for twenty-first-century Canada.

One month after becoming president of the United States, Barack Obama made his first foreign trip as president, and met with Stephen Harper in Ottawa.

Canada Today

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, Canada became known as a place with one of the world's most liberal social policies (that's liberal with a small "L"). Part of the reason why is that three of Canada's four major political parties (Liberal, New Democrat, and Bloc Québécois) have a left-of-center orientation. The other reason is that like western Europe, Canada is protected by the armed forces of the United States, so the government can allow the local army, navy and air force to shrink down, leaving it free to spend as much as it wants on social services. Consider these examples of modern Canadian liberalism:

1. Most US states still have the death penalty on their law books. Even California, one of the most liberal states, carries it out occasionally. Canada, on the other hand, abolished capital punishment in 1976, and proposals to bring it back are rejected like the plague.

2. Canada legalized medical marijuana for sick people in 2001, and began dispensing marijuana by prescription in July 2003. In both cases this was long before the same thing became legal anywhere in the United States.

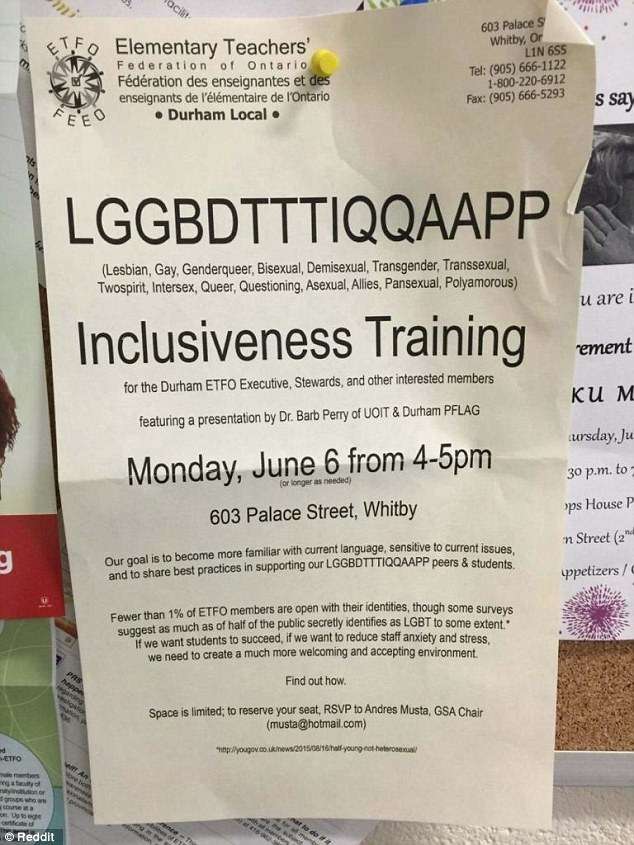

3. Same-sex marriage was legalized across Canada in 2005, ten years before the US Supreme Court did the same thing for the United States. In both countries, opinion polls showed that before legalization, a majority of the public was against it.

4. A 2004 poll in Canada showed that only 22% of Canadians would have voted for George W. Bush in that year's presidential election. Compare that with the 50.73% of Americans who voted to re-elect Bush. Only in the chronically Democratic District of Columbia did Bush get less than 22% of the vote; even Massachusetts, the home state of his opponent, gave him 36%.

5. The question of whether it is a racial slur to call someone "Kemosabe," the Indian name Tonto gave to the Lone Ranger, was a topic of serious discussion for the courts of Nova Scotia. Fortunately, the Canadian Supreme Court had enough sense to refuse to hear that case.

6. Laws and regulations that cause absurd results when enforced. One such law orders radio stations to play Canadian music at least 35% of the time, with strict rules on which songs are Canadian enough. For example, Celine Dion is Canadian, but her song "My Heart Will Go On" did not pass the test, because the lyricist, the songwriter, and the recording all came from elsewhere. An even sillier case came up in 2014, when three Toronto-based erotica TV channels were reprimanded because less than 35% of the pornography they broadcast was Canadian-made.

7. Socialized medicine, with the same problems that it caused in Europe. A 2000 report from the Heritage Foundation found long waiting lists, government rationing, and substandard care in Canada's system. To control drug spending, they limit the number of approved drugs and slow down the approval process, so that in one four-year period, Canada approved only 24 of 400 new drugs. Now that it looks like the United States is going the same way, let's see where Canadians will go for the healthcare they can't get at home.

8. An obsession with censorship. Canadians want to be seen as nice people, living in the most civilized of countries, where violence is only allowed at hockey games. This causes them to ban un-nice books and videos, starting with anything that includes "undue exploitation of sex" or is declared "degrading or dehumanizing." Likewise, advertisements become illegal if they are "directed at children", and speech (which includes telephone answering machine messages) is illegal if it "promotes hatred" or spreads "false news." For example, a few years ago, a Saskatchewan newspaper ad listed four Bible verses against homosexuality (just the chapter and verse numbers, no text), and showed two hand-holding male stick figures with a slash mark drawn across them; this was ruled a human-rights offense, and the man who placed the ad was ordered to pay $1,800 each to three gay men who found the ad offensive.(46)

Recently Ann Coulter, an American author known for her fiery, conservative views, got a strong lesson in Canadian-style censorship. In March 2010 she crossed the border to speak at three Canadian universities. Before the speeches took place, Francois A. Houle, provost of the University of Ottawa, wrote Coulter an e-mail warning that "promoting hatred against any identifiable group would not only be considered inappropriate, but could in fact lead to criminal charges." Then a mob of radical students threatened to commit un-Canadian acts of violence, forcing organizers to first increase security, then cancel the Ottawa speech. Ironically, the cancellation made Coulter a martyr for free speech; her next appearance, at the University of Calgary, was to a sold-out crowd.

For another recent example, a single Newfoundland listener complained about the Dire Straits song "Money for Nothing," because it mentions a "little faggot" three times in the second verse. This caused the Canadian Broadcast Standards Council (CBSC) to ban playing the song, unless the second verse was removed. What made this censorship silly was that the song was recorded in 1985, and the CBSC banned it in 2011, meaning it had been played freely for twenty-six years before anyone made a fuss over it. Second, anyone who listens to all of the lyrics knows that "Money for Nothing" is a blue-collar worker's lament about how rock stars can get rich without doing backbreaking labor; the "little faggot" in question is Boy George, and they're talking about him being a millionaire, not criticizing his lifestyle. Eight months later, the CBSC lifted the ban after receiving "considerable additional information," including the fact that "the composer's language appears not to have had an iota of malevolent or insulting intention." In simple English, somebody told the rest of the story to a censor who had probably never heard the song before banning it.

9. Like liberals in the United States, Canadians, especially the elite, love to imitate Europe. Examples of European fads include the censorship mentioned above, multiculturalism, contempt for religion (the "Toronto Blessing," an evangelical Christian revival in the 1990s, is an exception to this rule), and even a negative birthrate. I am mentioning the birthrate because the population of most European countries is currently declining, and Canadian women currently have an average of 1.49 children, when 2.1 kids per mother are needed to maintain the native-born population. The only reason why the number of people in Canada does not shrink is because enough immigrants come in to offset the lack of native fertility.

Eventually, the above birth dearth may end Canada's love affair with liberalism (the 2008 election could be a sign that it has happened already). Children are more likely to learn political, social and moral values from their parents, than from schools and other institutions. In the developed countries of the world, liberals avoided producing children, and quietly destroyed them if they made an uninvited appearance. Therefore when the time comes for the Left to pass on its values, the next generation won't be there.

At the beginning of this chapter we saw that Canada beat the odds, and overcame the challenges from without and within, to survive and prosper in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Because of that track record, I expect Canada will make it through the twenty-first century as well, especially if both the United States and Europe can overcome the current challenge from militant Islam. Unfortunately, while we can learn much from challenges of the past (e.g., fascism, communism, etc.), they don't teach us everything we need to know, in order to win in the present. That is why in the military, generals make the common mistake of preparing to fight future battles in the same way that they won previous battles.

There is also the ongoing issue of relations between the Francophone minority and the Anglophone majority. Will the recent declaration of Quebec as a separate nation within the nation be enough to guarantee future harmony, or will French Canadians continue to see themselves as strangers in a country that isn't theirs?

This marks the conclusion of our North American history narrative, "The Anglo-American Adventure." However, writing history is like writing a book that will never be finished; more chapters are likely to be added in the future, to cover events that haven't happened yet, not to mention future trends. Along that line, perhaps the best analogy to this work would be a TV drama with several episodes, that suddenly breaks off when the producers stop filming for the year. In that case, the story will end if the program is cancelled, but it is just as likely that new episodes will be filmed next year; the only way to know if the story is over is by checking for those new episodes. Thus, I won't say goodbye, when the best way to conclude an ongoing story may be to declare that this is

THE END

(for now)

FOOTNOTES

25. Since Massey, the Canadians have become more adventurous in their choices for governor general. The governor general from 2005 to 2010, Michaëlle Jean, was not even born in the British Commonwealth; her family came to Canada as political refugees from Haiti, and she holds a French citizenship as well. Her husband is a French Canadian filmmaker, so I guess being married to a Canadian citizen is all the qualification needed for the job these days. Maybe Canada wanted to be the first developed country with a black female head of state.

26. Diefenbaker was prime minister at the height of the Cold War; the bomb shelters built by his government were sometimes called "Diefenbunkers."

The Cold War led to a "friendly fire" incident in 1962, when a Canadian destroyer was conducting training exercises in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and the shells that missed the target landed in the village of Clallam Bay, Washington. Fortunately no one was hurt; the US and Canadian governments quickly dismissed the shelling as an accident, and the whole thing was soon forgotten. A hundred years earlier, the shooting of a nearby pig came closer to starting a war between the two countries (see Chapter 3).

27. In 1961 the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation joined with the Canadian Labour Congress, a federation of trade unions, to form the New Democratic Party. The New Democrats took a political stand to the left of both major parties, and in their first election, the one of 1962, they won nineteen seats.