| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Africa

Chapter 9: THE INDEPENDENCE ERA, PART III

1965 to 2005

This chapter is divided into three parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| Independence: Tying Up the Loose Ends | |

| Civil War in the Ex-Portuguese Empire | |

| Who Owns the Western Sahara? | |

| One-Man Rule: | |

| North Africa Takes a Military Road | |

Part II

| Nigeria: The Great Underachiever | |

| The Horn of Africa: Horn of Famine | |

| Southern Africa: The Fall of Apartheid | |

| Rwanda, Burundi, and the Congo: Still the Dark Heart of Africa |

Part III

| The Island at the End of the World | |

| America's Stepchild and Her Anarchic Neighbors | |

| The Islamist Menace | |

| Starting Over Again With the African Union | |

| Modern African Demographics | |

| The Challenges Facing Modern Africa | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

The Island at the End of the World

The first president of the Malagasy Republic, Philibert Tsiranana, was elected before the island became independent in 1960. Like the Ivory Coast's Félix Houphouët-Boigny, he was pro-French and procapitalist, but far less successful--his administration was unable to attract investors to the country, and it failed to reach even modest development goals, so living standards declined all around. He managed to win the support of most Malagasy by freeing those nationalists who had been imprisoned since the 1947 rebellion, and spent that goodwill on creating yet another one-party state. By putting a winner-take-all provision in the government, he managed to silence the opposition just by being the incumbent, and a policy of discrimination against the Merina in favor of the other tribes hindered the Marxists, because most of Tsiranana's opposition now came from the Merina middle class, a group not inclined to support communism.(42)

These moves allowed Tsiranana to be reelected in 1965 and 1972 without much trouble, but then came some unrest that he couldn't handle. There was a peasant uprising near Tulear in 1971, followed by a student strike just two months after the 1972 elections. The students demanded an end to the close ties between French and Malagasy schools, which helped keep the nation in the French cultural sphere, and more access to secondary schools for the economically underprivileged. Tsiranana arrested the student leaders, but that only caused workers, peasants and many unemployed folks, fed up with the stagnating economy, to join the strike. In May troops tried to stop rioting by opening fire on the demonstrators, killing between 15 and 40 and wounding 150. Tsiranana declared a state of national emergency, dissolved his government, and turned over power to the army chief of staff, General Gabriel Ramanantsoa.

Ramanantsoa, a conservative Merina, did no better at solving the economic and ethnic problems; his main accomplishment was changing the name of the Malagasy Republic to the Democratic Republic of Madagascar. After surviving an unsuccessful coup on the last day of 1974, he stepped down in February 1975. His successor, another Merina officer named Colonel Richard Ratsimandrava, was assassinated just five days later, and the military had to declare martial law. In June the ruling military council selected a naval officer, Lieutenant Commander Didier Ratsiraka, to be the new head of state. Ratsiraka proved to be more acceptable because he was not a Merina; instead he came from the Betsimisaraka, the main tribe on the east coast. In addition, he was a socialist, so he had the support of anyone who felt Madagascar needed to change--leftist political parties, students, urban workers, peasants, and the armed forces. He was elected to a seven-year term as president in December, beginning Madagascar's Second Republic.

Ratsiraka now set out to create his own socialist revolution, in a Malagasy style. This meant it would be nonviolent (overall the Malagasy are a gentle race), and follow a strictly nonaligned path in international affairs. One result of the latter was that the United States was ordered to close its satellite tracking system in Antananarivo, which it had used to keep in contact with spacecraft orbiting over southern Africa. Ratsiraka's government took over the education system and nationalized most of the economy, especially those sectors that had been under French control previously. He wrote down his plan for the future in a work named Charter of the Malagasy Socialist Revolution, but most simply called it the "Red Book" (Boky Mena). And while he allowed five other political parties to exist, they were forced to belong to a coalition led by his own party, the Vanguard of the Malagasy Revolution (AREMA).

How did all this work? Not too well, as you probably guessed if you're familiar with the track record of other countries that tried socialist/communist revolutions. The government borrowed heavily to pay for infrastructure development, leaving Madagascar deeply in debt. Today the country still has traces of a centralized economic system and a high level of illiteracy, thanks to Ratsiraka. Government repression, food shortages and price increases eroded away popular support, and though Ratsiraka was reelected in 1982 and 1989, many suspected the elections weren't entirely fair, so antigovernment demonstrations and coup attempts occurred after each one. In 1991 a general strike crippled the economy, and 400,000 protesters (in a country with a population of 12 million) marched on the President's Palace to overthrow the Ratsiraka government. The protesters were unarmed, so when the Presidential Guard fired on them, killing more than 30, it led to a crisis. No longer able to count on the loyalty of the armed forces, Ratsiraka agreed to a new constitution, free and fair elections, and to share power with the opposition leader, a member of the Tsimihety tribe named Albert Zafy. This arrangement lasted until the presidential election of February 1993, when Zafy won 67 percent of the vote, and thus became the next president.

Ratsiraka wasn't gone for long; in fact, he refused to vacate the President's Palace, becoming an embarrassment to Zafy. The euphoria that followed Madagascar's first change of power through the ballot box quickly faded; the economy continued to deteriorate and Zafy came under pressure from foreign donors, especially the International Monetary Fund, to cut budget deficits and a bloated civil service, and implement other market reforms. Protesters began to demonstrate because Zafy wasn't doing enough, which led to his impeachment by the National Assembly in 1996. New elections were held, and this time Ratsiraka beat Zafy; he was again proclaimed president in January 1997.

During the next four years, Ratsiraka had a new constitution passed, and argued with the IMF over terms for receiving new financial aid. In the presidential election of December 2001, Marc Ravalomanana, the popular mayor of Antananarivo, came out ahead of Ratsiraka, but neither received 50 percent of the vote, so a runoff election was required. Ravalomanana refused to do this; instead he simply declared himself the winner, and had himself sworn in as president. Still, "the president who wouldn't leave," Ratsiraka, demanded that the runoff take place, and set up a rival government in Tamatave, the country's most important port. An OAU-supervised recount in April 2002 confirmed that Ravalomanana was the rightful winner. Gradually the armed forces went over to Ravalomanana, until by July Ratsiraka only had control over the province containing Tamatave; at that point he fled to exile in France. Since then Ravalomanana's party has won parliamentary elections (December 2002), Ratsiraka was tried in absentia and convicted on charges of embezzlement, and Ravalomanana has moved to privatize state-owned companies; by doing the latter he has been more successful than other Malagasy leaders at securing international aid and foreign investment.

Though the worst political troubles may be over, Madagascar's other problems aren't even close to being solved. A classic example of a "developing nation," most of the people are poor, and the country is not yet industrialized, meaning that it is hard to find any factory-made goods, and many areas lack the utilities we take for granted, like clean water. Madagascar gets most of its income from three agricultural products--coffee, cloves and vanilla--which is risky when there are bigger profits to be made from manufacturing.(43) Rice used to be another export, but Madagascar can no longer sell it because of the island's growing population; the Malagasy are the world's biggest per capita consumers of rice. In addition, deforestation endangers the island; lumbering and slash-and-burn agriculture has caused large-scale soil erosion; the red soil stains the rivers so badly that astronauts in orbit can easily see it. We have seen environmental damage elsewhere in Africa (e.g., the Sahel), but 80 percent of Madagascar's plants and animals are found nowhere else in the world, so the problem is particularly serious here. Because so many of Madagascar's species are threatened, this island is the ecological equivalent of the "canary in the coal mine"; whatever mankind does that is harmful to the environment is likely to be felt first and foremost on Madagascar. Fortunately the Malagasy have been long aware of this (e.g., Madagascar's enormous "elephant bird" was apparently hunted to extinction by the first humans on the island), so efforts have been made to reforest some areas, and national parks protect 1.9 percent of the land.

America's Stepchild and Her Anarchic Neighbors

Liberia

For a century and a third of a century (1847-1980), Liberia looked like a time capsule of Antebellum America. Liberia's flag had the red and white stripes of the US flag, though only one star; the only legal political party, the True Whig Party, was named after one of America's parties in the 1840s; the ruling elite of Americo-Liberians (American-Africans?) had American names. Unfortunately, these former slaves also acted too much like the masters they had fled from. Once they had their own country, they became slave owners, and ran Liberia as if they were running a great plantation. In 1930, the League of Nations reported that Americo-Liberians were selling other Africans for forced labor, and threatened to take over Liberia and establish a trusteeship if this form of slavery was not stopped. Senior government officials were implicated in the scandal, and this led to the resignations of both President Charles D. B. King and his vice president. The next president, Edwin Barclay, spent six years abolishing the forced labor practices, and eventually his government got a clean bill of health from the League. However, Liberians who did not have American ancestry were still second-class citizens, without the right to vote. Barclay was succeeded in 1943 by Liberia's 22nd president, William Tubman.

William Tubman was the African equivalent of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Not only was he the longest-lived Liberian president, but he also was strongly pro-Western; he entered World War II on the side of the Allies in 1944, and even before declaring war he allowed American troops to use Liberia as a base. His seven terms in office are now regarded as the peak of the True Whig era, and while he did not allow any other political parties to exist, he was an honest ruler, and overall the country prospered. Tubman died in a London clinic in 1971, and William R. Tolbert Jr., who had been vice president for twenty years, took his place.

Tolbert made Liberia a little less authoritarian than it had been under Tubman, and tried to reduce the country's dependency on the United States. He accepted aid from the Soviet Union in 1974, and joined with other developing countries to sign a trade agreement with the European Community in 1978. However, he couldn't do much to improve the economy outside of Monrovia, and there were reports that the Tolbert family controlled a monopoly on rice imports, making people skeptical of anything he did with that important commodity. In 1978 a young Liberian named Gabriel B. Matthews announced he was forming an opposition party, and in 1979 a proposed increase in the price of rice led to riots that killed more than forty people. That marked the beginning of the end for the True Whigs, but Tolbert thought it was still business as usual. When he visited the United States in 1979, he confronted a demonstration against his government outside the United Nations headquarters, led by a US-educated Liberian, Charles Taylor (1948-). Tolbert personally debated Taylor, and lost. This made Taylor overconfident, and he tried to seize control of the Liberian mission at the UN; he was arrested, but later released and invited back to Liberia by Tolbert.

The last incident showed that Tolbert was overconfident, too; his downfall came as a complete surprise. On April 12, 1980, Master Sergeant Samuel K. Doe staged a bloody coup that killed Tolbert and several aides. Then Doe suspended the constitution and set up his own ruling group, the People's Revolutionary Council (PRC). Of the surviving officials, more than a dozen were put on trial without a lawyer, sentenced to death, tied to stakes on a beach and shot; one was spared because he wasn't an Americo-Liberian (he got his position by being adopted into the Tolbert clan).

Doe knew that his predecessors had ruled for so long because they kept good relations with the United States, so he did the same, openly declaring himself on the side of the West in the Cold War. There was a humorous incident around this time when Doe visited the White House, and President Ronald Reagan greeted him as "Chairman Moe." In return, the US wanted him to lift the ban on political parties that he imposed when he seized power. Instead, Doe replaced the Americo-Liberian oligarchy with one made up of folks from his own tribe, the Krahn, which was an even smaller part of the population (2 percent). When he gave in to US pressure, it was because he no longer feared being voted out of office; a new constitution establishing Liberia's second republic was introduced in 1984, and Doe narrowly won a presidential election in 1985.(44) The economy, however, was beyond his control; he tried to fix it by printing new money to pay the bills, and asking foreign governments for more aid. Anyone who has studied economics knows those are short-term solutions at best; by the end of the 1980s inflation was running wild and exports had all but stopped, leaving the Liberian practice of registering ships at a cut-rate price as the main source of income. Doe was also accused of human rights abuses, no surprise since he had begun his reign with a televised execution; Liberians began to joke that the initials of the PRC really meant "People Repeating Corruption."

Finally Doe's enemies pooled their resources, assembled an ill-trained army called the National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), and on Christmas Eve of 1989 they launched an invasion from the Ivory Coast. They received some assistance from Ivorian President Houphouët-Boigny, who had been Tolbert's brother-in-law and understandably didn't like Doe. Leading the army was the aforementioned Charles Taylor. Taylor had been a member of Doe's government, in charge of the procurement department, only to run afoul of Doe when he was accused in 1984 of embezzling $900,000. He fled to the United States, was captured in Boston, and was supposed to be shipped back to Liberia. Instead he escaped, reportedly bribing the jailors with $30,000, and sawing through the bars of the laundry room. Where he went between the United States and the Ivory Coast is a mystery; some believe he was hiding in Libya.

Anyway, the NPFL soon grew from 4,000 to 10,000 men, and gained control of much of the countryside in a few weeks. Then, when it seemed that they were about to win, a split divided the NPFL; Prince Yormie Johnson, a mentally unstable ally of Taylor's, took 1,000 soldiers from the force and founded his own group, the Independent Patriotic Front (IPF). The rebels entered Monrovia in July 1990, and six West African countries put together a peacekeeping force for Liberia (ECOMOG, the Economic Community of West African States Cease-Fire Monitoring Group), but it failed to halt the fighting. As for Doe, he turned down a US offer to be flown out of the country (the Americans had recently given free passage to Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines, and Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier of Haiti, after their subjects turned against them). What happened next is unclear; apparently Doe tried to visit ECOMOG headquarters in September, and was captured by Prince Johnson. Johnson had Doe's ears and genitals cut off before killing him, made sure the mutilation was videotaped in gruesome detail, and paraded what was left of Doe around Monrovia.

If you thought the Liberian civil war would end with Doe's death, guess again; it was only beginning. Both Taylor and Johnson claimed the presidency, but neither could hold onto it. By early 1991 ECOMOG held Monrovia while the NPFL held the rest of the country; ECOMOG set up an interim government, led by Dr. Amos Sawyer, a popular politician and professor. In October the NPFL agreed to disarm and recognize this government, but instead it clashed with ECOMOG, and in August 1992 it was attacked by ULIMO, a Sierra Leone-based faction loyal to the late Samuel Doe. By January 1993 the NPFL had been driven back out of Monrovia, and ULIMO captured much of western Liberia before it split into two tribal-based groups (ULIMO-J and ULIMO-K).

Now the civil war became a free-for-all. Cease-fires came and went, and so did temporary governments; between 1994 and 1997 three presidents succeeded Amos Sawyer, ephemeral figures who did not even belong to political parties. The competing factions splintered into smaller ones, all of which executed civilians who refused to join them, and they recruited boys as soldiers, some of them young as six years old; as many as 60,000 young thugs terrorized the countryside as a result. The typical Liberian fighter of the mid-1990s was a doped teenager armed with an AK-47, wearing a fright wig and some other piece of women's clothing, like a purse, a feather boa or a tattered wedding dress. Their outlandish costumes came from the belief that bullets could not kill them if the bullets didn't know whether they were hitting a man or woman (the same kind of thinking had caused African warriors to wear masks in the old days). Many of their leaders had been promoted directly from volunteer to general by Charles Taylor, and they took for themselves nicknames that even a certified hellraiser would hesitate to use: General No-Mother-No-Father, General Housebreaker, General F*ck-Me-Quick, General Baby Killer, General Peanut Butter, and General Dragon Master. The most notorious was Joshua Milton Blahyi, better known as "General Butt Naked" from his habit of going into battles wearing only a weapon and a pair of sneakers. While most of the "generals" came to a quick and brutal end, Butt Naked met the Lord in 1996, and since then he has been preaching in churches and on the streets of Monrovia. When talking about his past, the Reverend Blahyi confesses to having practiced voodoo and cannibalism, and describes his conversion with these words:

"So, before leading my troops into battle, we would get drunk and drugged up, sacrifice a local teenager, drink their blood, then strip down to our shoes and go into battle wearing colourful wigs and carrying dainty purses we'd looted from civilians. We'd slaughter anyone we saw, chop their heads off and use them as soccer balls. We were nude, fearless, drunk and homicidal. We killed hundreds of people--so many I lost count. But in June last year God telephoned me and told me that I was not the hero I considered myself to be, so I stopped and became a preacher."

|

|

|

| High fashion in 1990s Liberia. From Slate Magazine. | One of the Liberian warlords, ULIMO leader Roosevelt Johnson (no relation to Prince Johnson). |

Eventually the factions grew weary of the bloodshed and lawlessness; in August 1996 enough of them agreed to a cease-fire to allow a true disarmament program and new elections to take place. By this time, more than 150,000 had been killed, and more than one million people had fled their homes. When the elections were held in July 1997, Charles Taylor won three-fourths of the vote. Some accused him of threatening to kill the voters if he lost, but the election was probably fairer than any previous one in Liberian history, and the results were good enough to satisfy foreign observers.

The United States must have expected Taylor to do well as president, because he had excellent character references; former Attorney General Ramsey Clark had been his lawyer during his time in American jails, and President Bill Clinton, former President Jimmy Carter and the Reverend Jesse Jackson had all given Taylor their stamp of approval. He appointed the leaders of rival factions to government positions, and the ECOMOG peacekeepers began to withdraw. In fact, there was no reason to believe that Liberia was not about to see better days--except for the track record of past Liberian presidents. Isolated pockets of the country remained in revolt, and Taylor was accused of atrocities against the opposition, as well giving aid to rebels in all three neighboring countries (Sierra Leone, Guinea and the Ivory Coast). When the UN charged him with smuggling guns into Sierra Leone in exchange for diamonds, Taylor, a Baptist with a martyr complex, publicly appeared in white robes, begged God for forgiveness and denied the charges at the same time.(45)

Despite all his efforts, Taylor went from being Liberia's best hope to the country's biggest problem. A new civil war began in 1999 when a rebel group, Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD), invaded from Guinea (which is why Taylor supported rebels in Guinea). The government responded by shutting down independent newspapers and radio stations from 2000 onward, but this did not stop the decay of Taylor's regime. A second rebel group, the Movement for Democracy in Liberia, appeared in 2003; by August the two groups controlled at least 60 percent of Liberia's territory, and LURD began a siege of Monrovia.

Now Taylor came under pressure from the US and the UN to step down; he agreed to do so if another peacekeeping force arrived to end the violence. That force came first from Nigeria, and later from the UN, while the United States took a break from pacifying Iraq by sending 2,300 marines, using them to protect the US embassy and monitor the coast. Taylor moved to Nigeria, where he was indicted by the UN for his involvement in war crimes in Sierra Leone; Interpol and Sierra Leone want him too, but the Nigerian government refuses to hand him over until it gets a specific request from Liberia. A Liberian businessman, Charles Gyude Bryant, was sworn in to serve as president of a transitional government for the next two years (2003-2005).

New elections have just taken place at the time of this writing (November 2005). Initial counts give the prize to Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, a Harvard-educated former Cabinet minister who also worked for the UN and the World Bank. If this holds, she will be the first elected female head of state in Africa's history. Her chief opponent is George Weah, a soccer star whose lack of political experience appeals to those tired of the same old politics. More than fifteen years of constant war have left the economy in ruins, with disease and starvation running rampant, 80 percent unemployment and almost one third of the population homeless. By the time you read this, we may know if the man-made plagues that have afflicted Liberia for at least a generation have finally ended.

The Ivory Coast

In the Ivory Coast, also known by its French name of Côte d'Ivoire, Houphouët-Boigny's successor, Henri Konan Bédié, ruled for six years by favoring the mostly Christian southern part of the country against the largely Moslem north. Still there were accusations of corruption, and Bédié's suppression of political opposition made him unpopular even in the south. In December 1999 he was ousted in a bloodless coup led by General Robert Guéï, a military commander he had previously fired. Guéï adopted a new constitution and allowed elections to be held in 2000, but he kept a law introduced by Bédié that disqualified all Moslem candidates (the law required full Ivorian ancestry for the candidates and their parents, and many Moslems are immigrants from nearby countries like Mali). When another candidate, Laurent Gbagbo, won the election, Guéï refused to accept the results until a wave of demonstrations killed at least 200 people and forced him to step down.

The next round of unrest came in 2002, first with a failed military coup in September, and then with rebellions in the north and west. France negotiated a peace agreement in early 2003 that would allow the rebels to join Gbagbo in a coalition government, but the agreement also called for disarming the rebels, and they refused to give up their weapons, so the fighting hasn't completely stopped. French and West African peacekeeping troops stepped in to separate the forces loyal to Gbagbo from those backing the rebel leader, Guillaume Soro. This led to a nasty incident on November 6, 2004, where Ivorian air strikes killed 9 French peacekeepers and an aid worker, and France retaliated by wiping out the whole Ivorian Air Force in an attack on the airport at Yamoussoukro. At this time, most of the population is frustrated, because there are no signs that the quality of life will get better anytime soon, and the relative prosperity of the Houphouët-Boigny era is only a distant memory. Many blame the bad situation on northerners, and some have called for replacing Houphouët-Boigny's "Françafrique" system with "Ivoirité," a racist policy that would deny political and economic rights to immigrants. At the least, this may postpone the next elections indefinitely, if Moslems and Christians, the government and the rebels, cannot agree on who is eligible to vote.

Sierra Leone

Unlike Liberia and the Ivory Coast, Sierra Leone has no past tradition of stability and prosperity. It is blessed with mineral resources (diamonds, uranium, chrome, bauxite, iron ore, and traces of gold and platinum), but much of that is smuggled abroad, rather than sold on the open market, leaving the population with a per capita income of $150, one of the lowest in the world. The first prime minister, Sir Milton Margai, died in 1964, and his half-brother, Albert Margai, ruled after him. However, when elections were held in 1967, it was unclear whether Margai or the mayor of Freetown, Siaka Stevens, was the winner, so the commander of the armed forces, Brigadier David Lansana, arrested both, announcing that tribal representatives must first be elected to Parliament, and then they would choose the next prime minister. Instead, a second army group ousted Lansana in a 1968 coup, and then a third group ousted the second, put Stevens in charge, and restored civilian rule, though Stevens had to declare a state of emergency.

Sierra Leone was declared a republic in 1971, with Stevens as president. Opposition to the government still existed, but was gradually eliminated, to the point that Stevens' party, the All People's Congress (APC), ran unopposed in the parliamentary elections of 1973; in 1976 Stevens was reelected president. One year later the Sierra Leone People's Party (SLPP), the party of the Margai brothers, made a comeback in new parliamentary elections, but not by much; it won 15 seats while the APC won 74. Still, it was enough for the APC in enact a new constitution in 1978, one that made the country a one-party state, forcing the SLPP to join the APC. Stevens was sworn in for a new seven-year term in office.

With no checks on the power of the APC, or as the people now called it, the "political class," it quickly grew corrupt. Over the course of the 1980s, Sierra Leone suffered an economic slump, caused by a decline in export revenues. As a result, the APC gradually lost the ability to rule the country. Stevens retired in 1985, and the man he picked as his successor, Major General Joseph Saidu Momoh, had no trouble getting elected as the next president, since he was the only candidate. However, there was a coup attempt in 1987, and in 1990 the Liberian civil war spilled across the border. Following the fall of Samuel Doe in Liberia, Liberian guerrillas entered Sierra Leone and captured several towns to use as bases; when the government tried to take back these towns, a rebel movement, the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), appeared and joined the guerrillas, beginning a brutal civil war.

We have seen in this chapter that civil wars in sub-Saharan Africa make wars on other continents look like high school proms, and the one in Sierra Leone was no exception. No distinction was made between soldiers and civilians, so atrocities against civilians became a preferred tactic. The 3,000-man force of the RUF was mostly Moslem, and its leader, Corporal Ahmed Foday Sankoh, had gotten arms, money and training from Libya's Gaddafi and Liberia's Taylor. Most of the rebels had no ideology (how could they, when a lot of them were kids?), and they viewed warfare as a form of hunting, not wanting to make peace or even win, because they figured winning meant killing everyone else, and then there would be no one left to plunder! Instead of code names like Bravo Company, or numerical names like the 82nd Airborne, RUF units were named after their favorite atrocities: Burn House Unit, Cut Hands Commando, and Blood Shed Squad, to name a few. The Kill Man No Blood Unit specialized in beating people to death without shedding any blood, while the Born Naked Squad stripped victims nude before killing them. Likewise, instead of abstract names for their activities like Operation Desert Storm or Operation Overlord, RUF campaigns had names that brutally described what they were supposed to do: Operation Burn House (arson), and Operation Pay Yourself (looting) were two of them. Cutting off the arms and legs of civilians was commonplace, as well as cannibalism. Definitely not nice people.

The sinking economy and the civil war persuaded President Momoh to establish a constitutional review commission, and it recommended a return to multiparty democracy. Momoh agreed to do this, but some didn't think he was serious about it, and one group of young army officers decided not to wait for new elections; they staged a coup in April 1992 and replaced Momoh with Captain Valentine Strasser. Strasser's government reduced street crime, lowered inflation from 115 to 15 percent, and secured more than $300 million in foreign aid for Sierra Leone. However, this didn't stop the threat from the RUF. The government only had two helicopters and three planes in its air force, so just tracking small groups of rebels was a challenge. When government troops failed to penetrate rebel-held areas, Ghana, Guinea and Nigeria each committed a reinforced battalion to fight on Strasser's side, but they did no better. By the end of 1994 most of the country had been destroyed, and the RUF was the strongest force.

With few choices left, Strasser hired a well-known American mercenary, Bob MacKenzie. A veteran of the Vietnam War, MacKenzie had fought as a soldier of fortune in Rhodesia and El Salvador, and most recently had trained Croatian soldiers in Bosnia. Britain offered to help, too, unofficially asking MacKenzie to lead a brigade of 4,000 experienced Gurkhas--the best soldiers in the British army--to take back the diamond mines. In Sierra Leone he soon met his match, though; he got killed by the rebels (some say he was also eaten) only two months after his arrival. The Gurkhas ended up leaving without taking part in any major action, and the rebel offensive resumed.

Next, Strasser turned to a South African mercenary company, Executive Outcomes. EO's soldiers were veterans of elite South African units that had fought in Angola's civil war; their financing came from the De Beers Mining Company (Chapter 7, footnote #24), which understandably made recovery of Sierra Leone's mines a priority. As soon as the EO arrived in early 1995, it decided that Sierra Leone needed some aircraft, so they brought in five Ukrainian helicopters--two Mi-24vs and three Mi-17s--while Nigeria contributed two Alpha Jet fighters. Two of the helicopters were in such poor condition that they ended up being used as spare parts for the other three.

So far in the war casualties had been light, because soldiers on both sides were poorly equipped and usually under the influence of alcohol or marijuana, the result being that in a typical battle everyone would discharge a clip of ammunition and then run away. Rather than immediately jumping into the fighting, EO devoted several months to bringing in equipment, and because government troops behaved almost as badly as the rebels, the South Africans spent most of their time organizing and training the Kamajors, new combat teams made up of local militia and traditional hunters. When EO and the Kamajors were ready to strike, in August 1995, the results was far bloodier than previous armed encounters, and a complete success; RUF rebels were driven out of Freetown, and those fleeing from helicopter attacks ran right into the ambushes set up by EO and the Kamajors. This was followed up with a second offensive that liberated the mines and pursued the rebels all the way to Liberia.

Strasser had scheduled elections for April 1996, but he didn't take part in them; he was overthrown in a bloodless coup in February by his defense minister, Brigadier General Julius Maada Bio.(46) By this time the RUF was so badly beaten that it requested a ceasefire, and Bio agreed so that the war wouldn't interfere with the elections. Thirteen parties participated, Ahmed Tejan Kabbah of the SLPP was elected president, and Bio stepped down. On November 30, Kabbah and Sankoh signed a peace treaty to end a war that had killed 50,000 Sierra Leonians and forced 360,000 to flee into Liberia and Guinea.

The government now terminated its contract with EO, since it no longer needed EO's services. It acted a bit too soon. In May 1997 an assortment of junior army officers with various grievances staged yet another coup, freed Major Johnny Paul Koroma, an officer who had been arrested in September 1996 for plotting a coup, and put him in charge of the new junta. The officers declared they would rule by decree, and Koroma invited the RUF to join both the armed forces and the government. These were bad moves, which the world community immediately condemned; even worse, Koroma made Sankoh, who had been arrested during a visit to Nigeria in early 1997, the government's number two man. The UN imposed an arms embargo on Sierra Leone, and banned travel abroad for members of the ruling council. ECOMOG peacekeepers in both Sierra Leone and Liberia were given the job of enforcing the sanctions. Accordingly, Nigeria led an ECOMOG offensive that captured Freetown in February 1998, and Kabbah returned from exile a month later.

But all this did was switch everybody's places, like a game of musical chairs. The RUF resumed its struggle, this time with most of the Sierra Leone army on its side. Those troops who stayed with President Kabbah became the Civil Defense Forces (CDF). In October the government executed 24 members of Koroma's junta, including several RUF officers, and put a death sentence on Sankoh. The rebels responded with a campaign to kill, rape and destroy everything they could get their hands on, which they grimly named Operation No Living Thing. In December 1998 the rebels infiltrated Freetown and gained control over most of the city, the Presidential Palace, the radio station and the port of Freetown; only the airport and surrounding neighborhoods remained to the government and ECOMOG.

Even at this point, however, the rebels failed to achieve ultimate victory, because they did not have air power. In January 1999 3,000 Nigerian soldiers began a counteroffensive, backed by the previously mentioned Alpha Jets and one of the helicopters. The result was the most savage battle of the war; at least six thousand civilians were killed in Freetown, though the Nigerians lost one of the jets before it was all over. And the ECOMOG forces didn't behave much better than the rebels did; summary executions of rebels and suspected rebel sympathizers were routine, and a UN report at the time accused ECOMOG of a "totally unacceptable" level of atrocities.

Both sides now concluded that it would be impossible to win the war without destroying the whole country, so they began negotiations in Lome, the capital of Togo. Sankoh was released so he could take part in the talks, though Kabbah declared he would still carry out the death sentence unless a pardon was the only way to bring peace to Sierra Leone. Liberia's Charles Taylor also went to Lome to provide some diplomatic prodding, since he was still a pal of the RUF. They signed a peace agreement in July 1999 which promised a general amnesty for the RUF and reserved at least four cabinet posts for the RUF, one of them for Sankoh.

Despite the agreement, the war was in no hurry to wind down. Johnny Paul Koroma, the former coup leader, was put in charge of a commission to implement the Lome Accord, though he had helped cause the trouble that made the agreement necessary in the first place. A UN peacekeeping force stepped in to take ECOMOG's place, and in the May 2000 it clashed with the RUF, which refused to disarm. Foreigners became a popular target for attacks and kidnapings, forcing British troops to come in, rescue and evacuate foreign nationals from Freetown; they also captured and imprisoned Sankoh again.

Another ceasefire was signed in November 2000, at Abuja, Nigeria, and this time it lasted long enough for a UN-supervised disarmament of the rebels to take place. On January 18, 2002, Kabbah declared the civil war officially over, and he won a landslide victory in the elections held the following May. A war crimes tribunal was established in 2003 to try rebels for acts of terrorism, rape, sexual slavery, and extermination. However, it doesn't look like the two best known defendants will ever go to court; Sankoh died of a heart attack in July 2003, and Charles Taylor is still in Nigerian custody as we go to press.

The Islamist Menace

Islamic fundamentalism--sometimes called Islamism or Islamofascism--is nothing new to Africa. In Chapters 5-8 we chronicled several movements that used a literal interpretation of Islam as their guiding ideology: the Fatimids, Almoravids, Almohads, various Fulani states, the Mahdists, and the Sanussi. All of them eventually went down to defeat, often at the hands of non-Moslems (e.g, the Reconquista of Spain, the battle of Omdurman, the French conquest of West Africa). By the early 1920s, most of the Moslem world had been conquered by the European powers. Only Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan and Arabia remained under Moslem rule, and in the case of Turkey and Iran, new leaders arose who were determined to modernize their countries, even if it meant abandoning Islam.

However, the Islamist dream of a seventh-century utopia would not go away; it appealed to those who wanted revenge on the West, when the alternative was to become more like the West. Appropriately, the first group to promote it after the fall of the Ottoman Empire was based in Arabia--the Wahhabis, the spiritual advisors of the Saudi royal family. From them the idea spread to Egypt in the 1920s, via the Moslem Brotherhood, and when the ayatollahs took over Iran in 1979, they reintroduced fundamentalism to the Shi'a branch of Islam. The last two decades of the twentieth century saw a Moslem revival, as Islamists popped up in Moslem communities everywhere, and they gained control over many of the schools and mosques responsible for Islam's missionary efforts. What made these Islamists different was that they blamed different nations for causing all of the Islamic world's problems; in the past Christian Europe was the scapegoat, but now anything having to do with the United States or Israel became the primary target.

Americans tend to think that the War on Terror started on September 11, 2001, but long before that date, Islamists declared war on everyone who doesn't share their beliefs, including moderate Moslem leaders. Several African countries were on the front line from the start, especially Egypt, Libya, Algeria and Sudan. In fact, the assassination of Anwar Sadat was one of the first victories achieved by modern Islamists. The Egyptian government is notoriously inefficient when it comes to performing any of the services expected of today's governments, so groups like the Moslem Brotherhood made themselves popular by providing medical, educational and social benefits to poor people, using traditional Islamic networks; the chronic poverty of the Fellahin tended to work in the Islamists' favor, too.(47) Still, they cannot directly confront the Mubarak regime, so they usually try to murder indirect targets: secular-minded politicians and writers, Copts, and foreign tourists. By scaring away the tourists who come to see what the pharaohs built, they hope to shut down one of Egypt's biggest sources of revenue.(48) The worst of these attacks occurred at Queen Hatshepsut's Deir el-Bahri temple (see Chapter 2) in 1997, when six militants from the Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya group used guns and knives to kill four Egyptians and fifty-eight tourists. In July 2005, three bombs went off near the hotels of Sharm el-Sheikh, a resort city at the southern tip of the Sinai peninsula, killing 90 and wounding 150 (most of the victims were Egyptians). In both cases the terrorists expected to kill Americans and/or Israelis, but they didn't seem to care when somebody else became the victims. Nor did these attacks swing Egyptian opinion against the terrorists; the native workers who lost their jobs in the Sharm el-Sheikh bombings convinced themselves that "Zionists" or the West were somehow responsible.

Egypt has long been a westward-looking country, especially when Alexandria was the capital, and Egyptian Islamists are relatively weak compared with their Algerian and Sudanese counterparts. Still, many believe that Al Qaeda, the most notorious of today's terrorist organizations, was involved in the Deir el-Bahri and Sharm el-Sheikh massacres, and Al Qaeda has no trouble finding Egyptian recruits: Osama bin Laden's right-hand man, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and Mohammed Atta, the leader of the September 11 hijackers, both came from Egypt. Osama's family business, Bin Laden Brothers for Contracting and Industry, reportedly employs 40,000 Egyptians.

Whereas the Islamists were limited to acts of terrorism in Egypt, in Algeria they very nearly took over the country, resorting to bullets when they weren't allowed to win with ballots. It began when the military refused to recognize the results of the 1991 elections, which would have established a government run by the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS). They had good reason to be concerned; the FIS had condemned its opponents as unpatriotic, pro-French and financially corrupt, and that their goal was to establish an Iranian-style theocracy. And while the FIS wanted to be voted into office, it wasn't clear that they would ever allow themselves to be voted out in a future election. It didn't help when spokesmen for the FIS made statements like, "Democracy is like a virgin. You only use it once."

The army declared a state of emergency in early 1992, and started arresting FIS members--5,000 by the army's account, 30,000 according to FIS. Bearded men were afraid to leave their homes, because they might be accused of belonging to the FIS (compare this with footnote #17), and because there wasn't enough room in the jails to lock up everyone arrested, camps were set up for them in the Sahara desert. Part of the constitution was suspended, and the government was accused of many of the abuses that typically take place under Third World dictatorships: torture, the holding of suspects without charge or trial, etc. The FIS activists still at large launched the Algerian Civil War, which lasted until 2002.

As in previous Algerian wars, most of the fighting took place in the Atlas Mts., which have rugged, tree-covered terrain, ideally suited for guerrilla warfare; the oil industry in the Sahara was never seriously threatened. The Islamist rebels included veterans of the recently concluded war against the Soviets in Afghanistan, who had received training in Sudan and had a reputation for being even more extremist than the rest of the bunch. In 1993 and early 1993 some rival groups to the FIS formed: the Armed Islamic Movement (MIA), the Movement for an Islamic State (MEI), and the Armed Islamic Group (GIA). From 1994 onwards the GIA was the most prominent group, and the others, including the FIS, united to form the Islamic Salvation Army (AIS).

Though they disagreed on who was best suited to lead an Islamic revolution, all of these groups opposed the government. Most of them, especially the GIA, also felt that the government wasn't the only enemy; they expanded their list of targets to include teachers (because they were paid government salaries), journalists, foreigners, and any civilian who refused to live by the strict lifestyle of fundamentalist Islam. After a few well-publicized killings, like the 1993 beheading of four young women who were sunbathing on a beach in Western-style swimsuits, virtually all foreigners left the country, and quite a few Algerians emigrated, too. Because of the lack of coverage, Algeria disappeared from news headlines, and since 1994 most of the world has pretended that Algeria doesn't exist.

General Liamine Zeroual, a former diplomat and defense minister, became the next president in 1994; he came from the faction of the army that believed a negotiated settlement was still possible. Initial negotiations failed, so he decided to hold presidential elections. When they took place in November 1995, Zeroual won 60% of the vote, beating two Islamists and one secular candidate. The FIS boycotted the election, since they still were not allowed to participate, and the GIA threatened to kill anyone who voted (their slogan was "one vote, one bullet"), but foreign observers agreed that this was the fairest election Algeria had seen so far. International lenders rescheduled Algeria's foreign debt, a move that helped the economy, and Zeroual gained the confidence to introduce a revised constitution in 1996, and hold parliamentary elections in 1997.

Meanwhile, assassinations and disagreements among the rebels caused the GIA to begin to break up. By the end of 1995 it had turned against the AIS, and battles in the west between the AIS and the GIA became commonplace. In 1997 the war got even nastier, as the GIA started going into villages or neighborhoods and massacring everyone in them, regardless of age or sex. By this time the GIA felt that any Algerian who did not fight the government was corrupt enough to be considered an infidel, and thus it was no sin to kill them; Antar Zouabri, the GIA leader at this point, reportedly said that "except for those who are with us, all others are apostates and deserving of death." Many of the killings took place on the fertile Mitidja Plain, just south of Algiers, which had strongly supported the FIS in the 1991 election; this area was now renamed the Triangle of Death. Killing tens or even hundreds of civilians at a time, they would not even spare children or pregnant women, nor did they take time off during the holy month of Ramadan. Nesroullah Yous, a survivor of one of the worst massacres, claims that the attackers at Bentalha told him this:

"We have the whole night to rape your women and children, drink your blood. Even if you escape today, we'll come back tomorrow to finish you off! We're here to send you to your God!"(49)

At Bentalha and other massacres, it was also reported that the army arrived on the scene, did nothing to stop the killings, and even prevented the villagers from escaping. This led to rumors of collaboration between the army and the GIA. Other rumors asserted that civilian militias, trained and armed by the government, retaliated by committing their own brutal acts, playing tit-for-tat. Whether or not any of this was true, the fighting soon proved to be too much for the AIS. Caught between the government and the GIA, the AIS leader, Madani Mezrag, ordered a cease-fire in September 1997, effectively taking his group out of the war.

Wartime pressures may also have been too much for President Zeroual; in September 1998 he suddenly announced his resignation. Presidential elections were scheduled for April 1999, but before the voting took place, six of the seven candidates withdrew, warning of fraud; this allowed the seventh candidate, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, to win easily. Bouteflika was a veteran of the war for independence and had been foreign minister under Ahmed Ben Bella. To end the war, Bouteflika presented a "Civil Concord" calling for a pardon of all Islamist prisoners not guilty of rape or murder; this approved in a national referendum that September. The AIS formally disbanded in January 2000, now that its members had amnesty. The GIA was torn apart by splits and desertions in its ranks and by successful army counterattacks; it disintegrated after Zouabri's death in early 2002. By 2003, the only Islamist group left that hadn't laid down its arms was the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC), a splinter faction of the GIA which had an estimated 300 members and was supported by the Al Qaeda network. The GSPC's presence has resulted in an improvement of relations between the United States and Algeria, since Al Qaeda is a common enemy of both.

Algeria has suffered terribly from the civil war. Between 80,000 and 120,000 have been killed since 1992, and half a million were driven from their homes; the only good thing about these figures is that they are smaller than the body count racked up by Algeria's war for independence, forty years earlier. Some terrorist incidents still occur, but the country stabilized enough for new presidential elections, allowing Bouteflika to win a second term in 2004. International observers, however, say that Algeria has not made significant progress on human rights and democracy. There is also the possibility of future ethnic violence, between the Arab elite and the often-ignored Berbers, who make up 30 percent of the population; Berbers in the Kabyle region have staged strikes and demonstrations, protesting the outlawing of their language.(50) Finally, Algeria will need to deal with large-scale unemployment and diversify the oil-based economy, if it is going to prosper in the long run.

Whereas in Algeria the Islamists fought the government, in Sudan the Islamists and the government cooperated against the country's non-Arab and non-Moslem communities. When Omar Hassan al-Bashir seized power in 1989, he was expected to end the Second Sudanese Civil War, since his predecessor had failed to do so. Instead, he stepped up assaults on the rebels in the south, banned trade unions, political parties and other "nonreligious institutions," shut down the press, and purged 78,000 from the ranks of the police, the army and the civil administration. Al-Bashir dismissed his opponents as imperialist and Zionist agents, and like Moslem leaders elsewhere, he indulged in anti-Semitism from time to time; once he claimed that "Jews control all decision-making centers in the US. The Secretary of State, the Defense Secretary, the National Security Advisor and the CIA are all [controlled by] Jews." In 1991 he introduced a new criminal law code that called for harsh, Islamic-style punishments, including amputations and stoning. The south was exempt from the new laws for the time being, but since southerners had not received the sovereignty they wanted, the code could always be imposed on them at some future date.

Sudan backed Iraq in the 1991 Persian Gulf War; the United States responded by putting Sudan on a list of "rogue nations" supporting terrorism, began to isolate the country through sanctions, and offered money to any other country facing trouble from a Sudan-backed faction, like Uganda. In 1992 Osama bin Laden arrived, and Sudan became Al Qaeda's base of operations for the next four years. Sudan tried unsuccessfully to mend relations by handing over bin Laden to the United States, which wasn't interested in him yet (only later would he be implicated in terrorist attacks on Americans), and then expelled him in 1996, whereupon he moved to Afghanistan.

In March 1996 al-Bashir and his supporters swept presidential and legislative elections. Hassan al-Turabi, the head of the National Islamic Front and a national spiritual leader, became speaker of the National Assembly. One month later, evidence surfaced linking al-Bashir's government with a recent assassination attempt on Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak in Ethiopia; the UN subsequently levied sanctions against Sudan for refusing to give up three suspects in the assassination attempt.

After a government offensive in January 1994, the southerners had the advantage more often than not. Soon most of the south was controlled by the strongest rebel group, the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), led by John Garang. Because al-Bashir was so widely loathed, both by foreigners and by his own people, the rebels got the aid they needed from Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda and the United States; the Sudanese government also accused Eritrea and Tanzania of helping them. In response, pro-government militias, called the Janjaweed, committed horrible atrocities against civilians in the south; international observers accused them of genocide, torture, rape and murder on a large scale. In addition, because the war had been going on for so long, there was little agricultural or industrial production in the south, and the food sent by foreign agencies to prevent starvation was often kept from arriving by the government in Khartoum. Finally, there were credible reports of the Janjaweed bringing back slavery, breaking up Christian families by kidnaping women and children and forcing them to become workers or concubines. Al-Bashir spoke out against this cruel practice, but did very little to stop it; his government may have even encouraged it.

In December 1999, al-Bashir and al-Turabi had a falling out. Al-Turabi attempted to pass constitutional amendments that would have reduced the president's powers, by creating a prime minister who was chosen by the National Assembly, and by removing presidential control over the selection of provincial governors. Instead, al-Bashir declared a state of emergency, dismissed and jailed al-Turabi, and purged al-Turabi's supporters from the cabinet. One year later new elections were held, and al-Bashir won easily, no surprise since all other parties boycotted the elections and most of the south did not even get to vote. However, he still did not feel too confident about his position, and let the state of emergency continue until 2005.

Because of extremely heavy international pressure, especially after September 11, 2001, Khartoum agreed to negotiate a peaceful settlement with the rebels. Usually the talks failed to reach agreement on a key issue, like the relationship between religion and the government or whether the borders of the southern provinces would be redrawn, now that we know they contain oil. They finally signed a comprehensive peace treaty in January 2005, which called for the following:

- The south would have autonomy until 2011, after which it would vote on whether to become independent.

- John Garang would become vice president, with veto powers.

- Income from oilfields would be shared 50:50.

- Islamic law would only be in effect in the south if the National Assembly approved of it. In addition, the constitutional requirement that the president be a Moslem was dropped.

- A power-sharing agreement in which 52 percent of cabinet positions would go to the National Congress Party, 28 percent to the SPLA, and 20 percent to other groups.

By this time, Sudan's hot spot had shifted from the south to the west. Two rebel groups in Darfur, the westernmost province, launched a revolt in 2003. The rebels accused the central government of neglecting Darfur, though they did not agree on whether the solution was independence from the rest of Sudan or a new central government in Khartoum. The government gave Darfur the same response it had given the south; it sent in the Janjaweed militias, in addition to its own forces. In February 2004 the government captured Tine, a town on the Chad border, and claimed it had crushed the rebellion, but fighting still continues in many areas. Since then various reports have accused the militias of murders, gang rapes and ethnic cleansing, so the conflict has become a race war (Darfur's residents are Moslem, but not Arab), rather than a religious war like the conflict in the south. The UN Security Council passed a resolution in July 2004 that demanded the Sudanese government disarm and prosecute the militias, or face the threat of punitive measures. Instead, tens of thousands of people had been killed in Darfur by 2005, and as many as two million were homeless, with 200,000 of them becoming refugees in Chad. The ineffectiveness of the threat caused UN Secretary General Kofi Annan to state in a BBC interview, "We have learned nothing from Rwanda." Later in the same month (July 2005), Nicholas Kristof noted in a column for the New York Times that the media only gives Africa much attention when celebrities like Brad Pitt talk about the continent's plight, and wrote, "If only Michael Jackson's trial had been held in Darfur."

South of the Sahara, Islamists have only made limited inroads to date; for some reason Islam has a harder time advancing in places with trees than it does in deserts. Still, it would be folly to ignore a potential threat; Moslems have been trying to conquer/convert all of Africa for centuries, and there is no reason to think they won't try it again in the future. Earlier in this chapter we looked at efforts to spread Islam in West Africa's forest zone (Nigeria, the Ivory Coast and Sierra Leone). In August 1998 Al Qaeda set off bombs simultaneously in the US embassies at Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; more than 300 were killed and 5,000 injured, most of the casualties being African. The US response was to launch cruise missiles at Al Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan and at a Sudanese factory, but this was ineffective (the camps were deserted and the factory appears to have only produced harmless medicines, rather than nerve gas). Another bomb went off in an Israeli-owned hotel, and terrorists tried to shoot down an EL AL airliner with a shoulder-launched missile (both incidents occurred in Mombasa, Kenya, in 2002).

Despite all this, Africa's non-Moslem leaders are reluctant to side with the West against Islamic terrorism. The main reason for this is the same reflex that made many Africans support communism during the Cold War years; because Western nations ruled them half a century ago, they still see the West's enemy as a lesser evil. As for the United States, it never ruled any part of Africa besides Liberia, but because it has taken the place of Europe as the main Western power, it might as well be the same old thing. Nelson Mandela, for example, once claimed that President Bush "cannot think properly" and "wants a holocaust." Mandela's successor is even more blunt; in a speech to the Non-Aligned Movement in 2000, South African President Mbeki called the United States a country of increasing racism and xenophobia. And when South Africa hosted the 2001 U.N. Conference Against Racism in Durban, it quickly degenerated into a series of anti-American and anti-Semitic rants, until the United States walked out from the meetings. Of course a sudden upsurge in terrorist attacks, or a new Moslem-sponsored war in a sub-Saharan country, could change the minds of Black Africans in a hurry, but let's hope it doesn't come to that.

Even Muammar el-Gaddafi has become a potential target for terrorists, which is a surprise considering how recently he had been on their side. When he took over Libya, he installed an ideology that was partially based on the Koran, the same ultimate source used by the Sanussi king he replaced. Still, he was too secular for the tastes of hardcore Islamists, and from 1995 onward the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG), a faction with ties to Al Qaeda, tried more than once to kill the colonel-turned-president. Faced with the possibility of being violently removed from office by either the known devil of the West or the less predictable Islamists, Gaddafi chose to make a deal with the former. When American troops captured the Iraqi dictator, Saddam Hussein, in December 2003, Gaddafi came clean, announcing that Libya did have programs to develop nuclear and chemical weapons, and that he would allow international inspectors to observe and dismantle Libya's weapons of mass destruction. A spokesman for Silvio Berlusconi, the prime minister of Italy, said that Gaddafi called him on the telephone, because Berlusconi is a good friend of President Bush, and said, "I will do whatever the Americans want, because I saw what happened in Iraq, and I was afraid." In 2004 the US re-established diplomatic relations with Libya, British Prime Minister Tony Blair made a visit to Tripoli, and Libya's rehabilitation into the rest of the world community began. Later, like a teenager full of hormones, Gaddafi went so far as to develop a crush for Bush's Secretary of State, Condoleeza Rice; after Gaddafi was overthrown, a photo album filled with pictures of Rice was found in one of his compounds.

Hosni Mubarak had joined the US-led coalition that liberated Kuwait in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, but many Egyptians sympathized with the Iraqis, so his support got him nowhere. Consequently, the next time the United States went to war with Iraq, Egypt tried to stay out of the conflict, until the introduction of a Western-style democracy in Iraq persuaded the aging Mubarak that he'd better show some progress in the same direction. Originally, it looked like he was going to hand over the presidency to one of his sons, but after Iraq's free election in January 2005, Mubarak announced he would also allow multiparty elections, the first in Egypt's history. In previous elections, Parliament had put forth a single presidential candidate, and the voters had to vote yes or no on him; of course Mubarak won every time, and the results were so predictable that only around 10 percent of the voters bothered to go to the polls. In the multiparty election of September 2005, Mubarak was elected to a fifth term with 88.6% of the votes cast. This time the voter turnout was estimated at 22 percent. Opposition parties charged fraud and outside observers noted irregularities in the voting, but neither was enough to prevent an official declaration of a successful election.

Starting Over Again With the African Union

By the end of the twentieth century, it was clear that the Organization of African Unity was not succeeding in its primary function; the continent was no closer to becoming united than it had been when the OAU was founded. The only thing it did very well was bring Black Africans together to oppose white rule south of the Sahara; once colonialism and apartheid had been defeated, the OAU failed to find a new purpose. Part of the reason was the early agreement that governments and borders should not be changed. For example, early on the OAU helped mediate a border dispute between Algeria and Morocco and another between Somalia, Ethiopia and Kenya, rightly claiming both as successes, but in truth the maps of those countries had not changed at all. Eventually the policy of non-interference and non-intervention turned the OAU into a "dictator's club"; each member state usually turned a blind eye to what was going on in the others, and even a tyrant as odious as Idi Amin or Mobutu Sese Seko could sit at OAU meetings and not fear anything worse than verbal abuse.

The 2002 election in Zimbabwe was one of the last events overseen by the OAU. When the United States talked about putting sanctions on the Mugabe regime, the OAU issued a protest, but otherwise did nothing: "We are dismayed by this report, which amounts to interference in the internal affairs of a member state." No wonder Amara Essy, the last Secretary-General of the OAU, said in an interview that "The OAU is the most difficult organization I have ever seen."

The main mover and shaker in the transition from the OAU to the African Union was an unlikely one: Libya's Gaddafi. In the 1990s he gave up on his old dream of pan-Arabism; he no longer even called himself an Arab, insisting that he was first and foremost an African. "Libya has for too long endured the Arabs, for whom we have paid blood and money," he said in a 2003 speech, and because of that, his country had been "boycotted by the US and demonized by the West." In his new role Gaddafi called for the creation of a "United States of Africa," and hosted the first meeting to create a replacement organization for the OAU, at Sirte, Libya in 1999. Additional meetings were held in Lome, Togo in 2000, and Lusaka, Zambia in 2001; all three summits were successful in producing agreements. The African Union itself came into being at Durban, South Africa in July 2002, with South African President Mbeki as its first president.

The African Union flag.

Most former OAU members joined the African Union immediately; the only country that has refused to join is Morocco, because the Western Sahara is a member. Paradoxically, Morocco instead asked in 1987 if it could join the European Economic Community, the forerunner of today's European Union. The Moroccans wanted to join because they felt they had been treated well by their former colonial masters, Spain and France. Moreover, at the Strait of Gibraltar's narrowest point, only 14 kilometers (8.6 miles) separate Morocco from Spain (see footnote #8). And because Spain still rules two towns on the African side of the strait (Ceuta and Melilla), Morocco enjoys a land connection with Spain as well. The Europeans rejected Morocco's request immediately, for reasons of geography; in no way were the Moroccans Europeans. However, the Europeans were willing to improve relations and increase trade; two political agreements with the European Union (signed in 2000 and 2008) did just that. Today the European Union is Morocco's primary trading partner abroad.

Of course, the African Union's name comes from the European Union, which it is modeled after, though some of the official bodies that make up the organization were inspired by the United Nations.(51) What makes the AU different from the OAU (besides the removal of one letter) is a stronger emphasis on economic development, promoting democracy and improving the lives of ordinary people, even if these goals mean abandoning the principle of state sovereignty. So far, however, when it comes to dealing with corruption, warfare and AIDS, the AU has acted no different from its predecessor. This is not a good sign; to remain a relevant organization, the AU will have to show that it can implement what it promises.

Modern African Demographics

Counting all the people in a community is a major task, even in countries that are used to doing it. In Africa it is particularly difficult; many African countries do not conduct a regular census. That is why we only looked at Africa's population three times in this narrative (the other times were in Chapters 4 and 6).

Our best estimates put approximately 800 million people in Africa for the year 2000, and by 2023, it was 1.429 billion. This is 18 percent of the total world population, so keep in mind that it's really a recovery of sorts; before the introduction of conveniences like modern medicine and sanitation, Africa's portion had been shrinking, thanks to the harsh environment that limited growth across most of the continent. Five thousand years ago, the African portion of world population was probably 20 percent. By 1800 A.D., however, it was as low as 7 percent, so if Africa had kept up with the rest of the world over the ages, there would be nearly two billion Africans by now.

The five most populous countries are Nigeria (183.5 million), Ethiopia (98.9 million), Egypt (84.7 million), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (71.2 million), and South Africa (53.5 million). Nigeria and Egypt have been ahead in the population department for centuries, and they piled on to their lead at such a rate (at least a million every year) that it seems only a pandemic or famine can stop the growth.(52) Ethiopia and the Congo are the big surprises, from a census-taker's point of view; neither was a top contender in the mid-twentieth century, but both of them more than tripled their population in just the period covered by this chapter, and they did it in spite of the wars and poverty that have gripped those lands. South Africa had just two million in 1800, and it got to where it is today by building the most advanced society in Africa, thereby attracting quite a few immigrants; in fact, it was in third place in the late twentieth century, before Ethiopia and the Congo pulled ahead.(53)

Africa's population also became more diverse. Besides the ethnic groups listed in previous chapters (Bantus, Nilotics, Pygmies, Bushmen, Semites, Berbers and Malagasy), the above total includes more than 4.5 million European whites, 2.7 million Indians and 5.6 million "coloreds." Most of the folks from all three groups live in South Africa; in fact, the continent's population was even more diverse during the colonial era than it is now, but when independence came, most African countries have forced the non-Africans living within their borders to leave. Another factor promoting diversity is the city; cities bring together people from many tribes, so the typical urban African will rub elbows with members of other tribes more often than he would if he had lived like his ancestors. Older West African cities like Kano try to limit intermingling by segregating the immigrants to separate neighborhoods, the so-called "stranger quarters." Although Africa's urban population is 47 percent, making this the least urbanized continent, it has some of the world's largest metropolitan areas: Cairo currently has 22 million residents, Kinshasha has 16 million, and Lagos has 15 million.(54)

Finally, modern Africa's population is a mobile one. For those whose ancestors were nomads, moving around a lot comes naturally. Others learned to make long commutes in colonial times, when they worked on mines and plantations located more than a day's journey from home. Nowadays, ambitious Africans will move to the cities, but they don't stay there all year long; many regularly go back to visit their birthplaces and/or the lands of their ancestors.

However, many migrating Africans are refugees. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 30 percent of the world's refugees come from Africa. As in other places, African refugees flee from war, tyranny or famine--and Africa has plenty of all three. Usually they go to the nearest country that will take them in, and if enough migrate in that direction, they will destabilize the host country to the point that another wave of refugees will head in the opposite direction. Examples of such exchanges took place in the late twentieth century between Ethiopia and Somalia, Rwanda and Burundi, and Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Some Africans make a complete break with the past, by migrating off the continent altogether. Generally, the Western nation that colonized them is their first choice, even if the colonial power was oppressive (e.g., Senegalese leaving Africa are inclined to pick France for an overseas home, but so do Algerians, though the French treated them worse than the Senegalese). Unfortunately, most Africans leave for other continents because they have little to lose and much to gain by moving elsewhere. And because the richest and best-educated find it easiest to leave, the result is a "brain drain" that Africa can't really afford. In the United States, for example, 881,300 US residents were African-born at the time of the 2000 census; often they are better off than their "African-American" brothers, whose families have been in the New World for centuries. Walter Williams, a black American columnist, illustrated the predicament by telling about an event he attended a few years ago, at the Nigerian embassy in Washington, D.C. At one point, the Nigerian ambassador told the audience, which was mostly Nigerian, that they should go back to Nigeria, because people with professional skills are sorely needed there. Many of the Nigerians responded by breaking out in near uncontrollable laughter.

Africa has the world's highest birth rate; the total population has grown almost fivefold since the 1960s. The annual growth rate peaked at 3.43 percent in 1979, and though it has leveled off since then (down to 2.08 percent), it is still higher than the world average. When it comes to human communities, forget what you learned in school about "survival of the fittest"; the poorest, least fit societies are growing the fastest in today's world, while the most advanced societies, especially those of Europe and Japan, aren't fertile enough to keep their populations from shrinking.

There are both positive and negative factors behind the drop in Africa's birthrate over the past generation. The positive factor is a change of attitude brought about by modernization. In pre-industrial societies, large families are an asset; children are a symbol of wealth and prestige, an important source of labor, a form of insurance to make sure the elderly are cared for, and through marriage, they allow a family to network with as many other families as possible (interdependency is important in a place where many hazards, both natural and manmade, exist). For those reasons, childlessness is often seen as a tragedy. In Chapter 18 of my European history, I explained why Europe's birthrate declined in the twentieth century: marriage and childbearing delayed by the demands of education and career, the viewing of children as a costly burden, and the introduction of birth control. Similar trends are now taking place among Africa's urban middle class.

The negative factor is a high death rate; Africa ranks highest there as well. Plants and animals that produce many young tend to lose many young, and the same seems to be true with human communities. Life in Africa is cheap, to a degree that Europe hasn't seen since the end of the Thirty Years War. For a start, Africa provides so many "natural" ways to die: wild animals (e.g., crocodiles, lions, sharks, poisonous snakes and insects), parasites, bad food, no food at all, and so on. Add manmade causes like violent crime, war, and the various atrocities that come when governments ignore human rights and the rule of law. Top that off with epidemics like AIDS, and you'll get an idea why Africa's life expectancy, after rising for most of the twentieth century, has fallen in recent years; the overall life expectancy for the continent is now just fifty years.

Kim du Toit, a blogger who lived in South Africa for thirty years, used this story to explain Africa's casual attitude toward death:

"My favorite African story actually happened after I left the country. An American executive took a job over there, and on his very first day, the newspaper headlines read: 'Three Headless Bodies Found.'

The next day: 'Three Heads Found.'

The third day: 'Heads Don't Match Bodies.'"(55)

So far in this chapter we haven't talked about the impact of AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome), and we should, because it has infected more people in Africa than on any other continent. Equatorial Africa is a notorious "hot zone"; the tropical climate of this region, coupled with the natural biodiversity of the jungle, make it easy for microbes to jump from one species to another. Apparently this is what happened with AIDS; we now believe that HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, made the jump in the 1930s, when a human hunter butchered a chimpanzee and came in contact with HIV-tainted blood. At first the disease stayed put, because it was confined to an isolated, rural community, but the construction of the Kinshasa Highway, and the wars, famines and political upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s, encouraged infected Africans to migrate to the cities, taking the disease with them. From there it spread like wildfire, thanks to modern transportation, and the first cases of AIDS outside of Africa were reported in 1981.

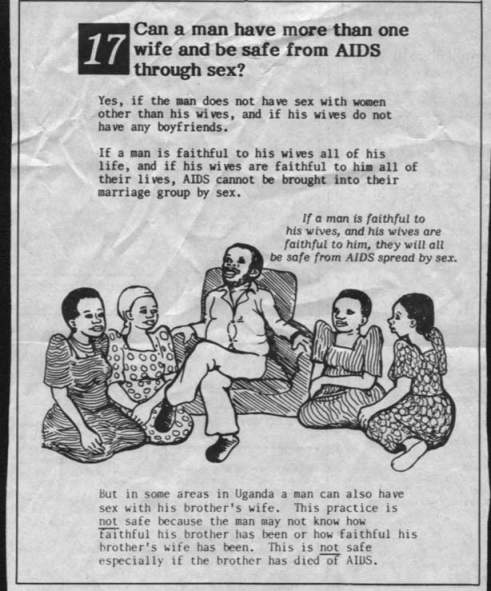

One major reason why AIDS has spread is ignorance about what causes it. Thus, education has become one of the weapons used to fight it. This strange poster from Uganda is part of the effort to stop the spread of AIDS, by teaching safe sex.

AIDS is a worldwide problem, but Africa has been the continent hardest hit, due to it being the site of the first outbreaks, unsafe sexual practices, substandard medical facilities, soldiers raping their victims in war zones, etc. According to the Population Reference Bureau (prb.org), all of the fifteen countries with the highest percentage of AIDS cases are in Africa. Here are the figures as of 2003:

| Rank | Country | Percentage of Population Infected |

| 1 | Eswatini(56) | 38.8 |

| 2 | Botswana | 37.3 |

| 3 | Lesotho | 28.9 |

| 4 | Zimbabwe | 24.6 |

| 5 | South Africa | 21.5 |

| 6 | Namibia | 21.3 |

| 7 | Zambia | 16.5 |

| 8 | Malawi | 14.2 |

| 9 | Central African Republic | 13.5 |

| 10 | Mozambique | 12.2 |

| 11 | Tanzania | 8.8 |

| 12 | Gabon | 8.1 |

| 13 | Ivory Coast | 7.0 |

| 14 | Cameroon | 6.9 |

| 15 | Kenya | 6.7 |