| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Africa

Chapter 7: THE DARK CONTINENT PARTITIONED, PART I

1795 to 1914

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| The Quest for the Source of the Nile | |

| Egypt in Bondage | |

| The Mahdist Revolt | |

| Abyssinia Regenerates | |

| The Zulu War | |

| The "Scramble for Africa," Part I | |

| From the Cape to Cairo | |

| "Heart of Darkness" | |

| From Dakar to Djibouti | |

| The Boer War | |

| Libya and Morocco: The Last Unturned Stones |

Great Britain Comes to South Africa

Before the nineteenth century, rarely a year went by without a war taking place somewhere in Europe, and whenever the two biggest rivals, Great Britain and France, had a showdown, there was a chance that their overseas colonies would be drawn into it. However, this rarely happened in Africa, due to the very limited commitment there by Europeans. There were no African battles in the Seven Years War, for example, to match the ones in India and North America, and while Britain's enemies saw the American Revolution as an opportunity for a rematch, in Africa it only meant some skirmishing between the British, French and Dutch forts on the Gold Coast.

This changed with the long, on-and-off conflict that lasted from 1789 to 1815, known in European history textbooks as the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. As France conquered first the Netherlands, and then Spain and Portugal, Britain began using the Royal Navy to pick off the overseas colonies of those nations, lest their resources be used in what London feared the most, a cross-channel invasion of England. The results were dramatic on opposite ends of the African continent, in South Africa and Egypt. Britain got involved in South Africa when Prince William, the exiled Dutch leader, asked the British to take over the administration of the Cape Colony before it fell into the hands of the French, so the Royal Navy sailed in and occupied Cape Town in 1795. They gave it back during a cease-fire between Britain and France in 1803, but soon after that the war started up again, so in 1806 the British sent sixty-three ships and 6,700 men to overwhelm Cape Town's defending militia of Dutch burghers and Hottentots. This time the occupation was more permanent; after the war Britain kept South Africa, half of Guyana, Sri Lanka and the Malayan outposts of Malacca and Penang, while returning Java to the Dutch and giving them Belgium and £6,000,000 as compensation.

In Britain's new colony, relations between the Boers and the Xhosa remained poor. The population of the Xhosa and Nguni tribes was still rapidly growing in the Natal region, and when a new conflict over pastureland and cattle broke out (the Third Kaffir War, 1799-1802), the Xhosa crossed the Great Fish River and found allies among the Hottentots, who deserted their Boer masters and brought guns and horses with them. Great Britain was too busy with the Napoleonic Wars to act effectively in South Africa, so it made concessions to the Hottentots that brought them back over to their side, and for the time being the British ignored the Xhosa squatters on the Zuurveld, an eighty-mile-wide stretch of land west of the Great Fish River.

Maybe the Boer farmers resented Dutch authorities telling them what to do, but soon they decided they liked the British even less. The British governor would have preferred to leave South African society alone--he even kept several middle-level Dutch officials in their jobs--because anything else would have meant more work to do. Instead, missionaries with Abolitionist sympathies came to the colony, and they called for treating the natives more fairly than they had been treated up to this point. By this time, the Boers had come to see Hottentots, Bushmen and Xhosas as inferior beings, created by God to be their servants, and the Boers lost many of their Hottentot workers when they took refuge in mission stations (the missionaries treated the natives better, and thus were viewed by the farmers as troublemakers who stole their help). When London outlawed the slave trade in 1807, and started arming Hottentot soldiers to enforce its rule, the Boers thought Britain was going to destroy their way of life completely.

The truth was that the governor of Cape Town, Sir John Craddock, wanted more than anything else to keep the peace. Instead, he got thousands of Xhosa swarming across the Great Fish River to find new pastures on the Zuurveld. In response, he ordered Lieutenant Colonel John Graham to do whatever was necessary to drive the Xhosa back. The resulting conflict, the Fourth Kaffir War (1811), was a complete success; by destroying their villages and crops wholesale, Graham forced the Xhosa to leave, going back across the Great Fish to face almost certain starvation. Then he tried to secure the frontier with a string of forts and two new villages named Craddock and Grahamstown. Even so, the Xhosa, now more desperate than ever, could still raid the Zuurveld, and in the Fifth Kaffir War (1818-19), they almost captured Grahamstown before they were defeated again. This time the British declared the territory between the Great Fish and Great Kei Rivers to be "no man's land," but this policy was doomed to failure, because it declared off-limits a piece of land that both sides badly wanted. In fact, British settlers started moving into this neutral zone before long.

In 1820, a fleet of ships carrying 3,500 British settlers arrived at Algoa Bay, a spot on the coast nearly a hundred miles west of the Great Fish River's mouth. Follow-up expeditions increased this number to 5,000. These were unemployed, desperately poor people, who had been lured to leave Britain by an economic depression at home, and a promise of free passage and 100 acres of land to each of those who went. This was really a continuation of the policy London had used to colonize North America and Australia--get rid of people it didn't want by relocating them overseas. What the colonists didn't know that their destination was a war zone (the author of the advertisements had only written about a "misunderstanding" between previous settlers and the Africans), and the government expected them to pacify it. Thus, they were ill-prepared, inexperienced, and ridiculously optimistic about their new homes. They tried to grow crops on land better suited for herding, and failed (even the Boers called this land "sour country"); most of them eventually sold their land and moved to the towns, where they either ended up working for someone else if they had useful skills, or sank into wretched poverty if they didn't. Nevertheless, their presence tipped the balance of power in favor of the Europeans; the number of Europeans on the Zuurveld had increased by 50%, and the total number of English-speakers in the colony had doubled. They also were the first to successfully breed Merino sheep, something the Boers had refused to try, giving the colony an important new export.(1)

The Napoleonic Gambit

Meanwhile on the other side of Africa, the French government and France's current war hero, Napoleon Bonaparte, hatched a wild scheme to invade Egypt. The idea was to strike back at Britain's naval policy by capturing Egypt and using it as an advance base to threaten the most prized colony of the British Empire, India. Everybody involved had different reasons for trying it; Bonaparte saw himself reliving the adventures of Alexander the Great, his rivals were glad to see him get out of France, his soldiers wanted to meet girls and bring back some souvenirs, while a group of savants (engineers, scientists, artists and scholars) came along to study the mysterious ruins that dotted the banks of the Nile. In May of 1798 they left France, dodged the squadrons of British Admiral Horatio Nelson, took Malta in June, and landed at Aboukir Bay, near Alexandria, in July. Bonaparte told the Egyptians they had nothing to fear, because they were there with the Turkish sultan's blessing, and because the French Revolution had recently destroyed the power of the Catholic Church in France, the French were all Moslems now. Of course none of this was true, and the sultan called for a jihad against the infidel invaders, but Bonaparte had no trouble defeating Egypt's Mameluke guardians, and took Cairo three weeks after his arrival.

Nobody seems to have thought much about what to do next, except for Admiral Nelson, who in August sailed into Aboukir Bay and blew the French fleet to bits.(2) Bonaparte tried marching into Asia, got as far as Acre in Israel before a lack of supplies and a determined defense forced him to return, and hung around in Egypt until October 1799, when he saw an opportunity to sneak back to France on a frigate. His soldiers surrendered to the British, and two years later they were allowed to go home under a truce.

Though the military campaign was a fiasco, the "wise men" who accompanied the soldiers scored a real success, by rekindling the world's interest in Egypt's ancient civilization. They drew pictures of nearly everything they saw, and brought back many artifacts, the most important being the Rosetta Stone (see Chapter 2). Knowledge of what the Egyptians had accomplished had been forgotten over the millennia, to the point that by 1800 little was known about Egypt, aside from what travelers could see on top of the sands and from what had been written in ancient works like the Bible and The Histories of Herodotus. One thing neoclassical scholars were certain about was that Egypt was old, perhaps older than any other nation. Bonaparte was remarkably close to the truth when he pointed to the pyramids of Giza and told his men, "Soldiers! From the summit of yonder pyramids forty centuries look down upon you." With the translation of hieroglyphics a generation later, an important chapter in mankind's early history was restored.

The Fulani Jihads

While France and Britain were meddling on the northern and southern ends of the continent, West Africans were probably more concerned with the continuing advance of the Fulani tribe. In the previous two chapters we looked at how the Fulani spread across the Sahel, and grew increasingly aggressive as they converted to Islam. African Moslems probably did not see the Europeans as an immediate threat, but they must have been aware of how in other parts of the world, like India and the Balkans, Islam was on the defensive against Christianity. Thus, when Arabia's Wahhabi sect (see Chapter 14 of my Middle Eastern history) was founded in the mid-eighteenth century, many Africans were susceptible to its call for following Islamic law to the letter. At this time a number of religious schools, known as tariqa (brotherhoods), existed in the Sahara, usually named after the founding teacher (e.g., the Tijaniyya brotherhood was named after Ahmad Tijani). Now existing brotherhoods reformed themselves to become more fundamentalist, and several new ones appeared that imitated the Wahhabis.

The most successful Fulani leader, Usman dan Fodio (1754-1817), was born in the Hausa state of Gobir, in what is now northern Nigeria. A member of the Qadiriyya, a Tuareg brotherhood, he went to the oasis of Agades to complete his education, and when he returned he became tutor to Yunfa, the son and heir of Nafata, Gobir's ruler. From that position he called for religious reform, and promised that the Mahdi would be coming soon after him, but when Yunfa succeeded his father in 1801, he lost whatever interest he had in dan Fodio's ideas. Shortly after that, Yunfa summoned dan Fodio and tried to shoot him, but the pistol backfired and he wounded his own hand. The disappointed teacher withdrew to his native village, and so many followers went with him that Yunfa threatened military action. In response, Usman dan Fodio retreated even further, to the Gudu district (1804), announced that he was re-enacting Mohammed's hegira or flight from Mecca to Medina, and gained still more followers, until he had a formidable army. With this he declared a jihad, and enjoyed rapid success, as all who disliked the half-pagan Hausa rulers joined the movement. In 1808 he killed Yunfa in battle, and captured Ngazargamu, the capital of Bornu; by 1809 he had conquered not only all of Hausaland (a Fulani emir now replaced the Hausa king in each city), but also much of the surrounding territory, reaching as far as Adamawa in the Cameroon mts. His only defeat was in the east, where he was driven out of Bornu in 1811 by Muhammad al-Kanemi, the cleric-turned-warrior who currently ran that country.(3)

In the forest zone, the Fulani empire included Ilorin, the northern half of the Oyo kingdom. This was not a conquest so much as an annexation; Fulani agents and their ideas infiltrated Oyo until many of its citizens decided they would like to see a change of masters. In 1817 several Oyo chiefs, led by Afonja of Ilorin, sent an empty calabash to Aole, the king of Oyo, signifying that they would no longer pay tribute. Aole cursed his former vassals before committing suicide, and the kingdom quickly disintegrated. Ibadan arose to become the most important Yoruba city after this, but it never completely replaced Oyo, so neighbors like Dahomey and Benin saw these events as the elimination of a rival.

Usman dan Fodio eventually grew tired of conquering, being more of a scholar than a king or general, so he built a new capital at Sokoto and settled down. His son and heir, Muhammad Bello (1817-37), enjoyed a peaceful reign, because the Fulani lost their religious zeal after they became a new ruling class. However, by this time they had also planted a successful missionary enterprise in the west. In 1810 Hamadu Bari (also known as Ahmadu Lobo), one of dan Fodio's early followers, led an army to his homeland on the middle Niger, and drove the Bambara out of the area between Jenné and Timbuktu; this became a new Fulani kingdom, known as Masina.

The fiercest jihad of all came from the Fulani homeland of Senegal, and was led by a cleric named Umar (1797-1864), a native of the state of Futa Toro. At the age of 29, he made his pilgrimage to Mecca, joined the Tijaniyya brotherhood before returning, spent a considerable amount of time on the way back in Bornu, Sokoto, and Masina, and even married the sister of Muhammad Bello. Now called Al-Hajj Umar (Umar the Pilgrim), he finally settled in Futa Jallon in 1837, gathered a number of followers, and armed them with European-made guns. In 1849 he was forced to leave, so he moved to the Tukulor tribe, turned their state into a theocracy, and three years later he launched his jihad, first attacking the two Bambara kingdoms because they were still pagan. Over the course of the following decade, he built an empire on the upper reaches of the Niger and Senegal Rivers, called the Tukulor empire. He also conquered Khasso, and would have taken Futa Toro next, but his advance to the west ran into the French advancing east.(4) The troops of Umar and the French governor of St. Louis, Louis Faidherbe, clashed in 1857, and while the Fulani stopped the French from going any farther, they failed to take Medine, the newest French fort, and Futa Toro fell to the French. Then Umar negotiated a treaty with Faidherbe, and turned his attention back eastward. He finished off the Bambara by taking Segu in 1861, and overran Masina a year later. By 1863 he had also captured Timbuktu, but there he reached his limits; the local Tuaregs joined the Fulani of Masina in a revolt, and Umar was killed defending Hamdallahi, his capital, from the rebels, in February 1864. His son, Ahmadu, spent the next ten years just establishing his right to rule the entire empire. And because the French now had Futa Toro, the ancestral home of the Tukulor rulers and many of their warriors, an observer could expect a rematch between the French and Tukulors, since their first conflict hadn't really settled anything.

"To the Shores of Tripoli"

In the previous chapter we saw the Ottoman Empire's African provinces drift into what was, for all practical purposes, independence. They went so far as to work against each other during the Napoleonic Wars. Yusuf Qaramanli, the pasha of Tripoli, assisted the British in the recovery of Egypt from Napoleon, and in return the British helped him conquer the Fezzan, the interior district that now makes up southern Libya (1801-11). The bey of Tunis acted more neutral, openly favoring the French but secretly accepting British aid to keep himself independent of the Ottoman sultan, while the dey of Algiers sold considerable amounts of grain to France from 1792 to 1815, even when Napoleon was attacking Egypt.

We also noted previously that the Barbary pirates, who had once provided a major source of income for all of the Maghreb states, stopped being a threat to European shipping in the eighteenth century. However, they were still dangerous to the infant United States, which at this stage didn't have a navy strong enough to protect American ships in the Mediterranean. Before 1776, American ships were safe because they flew the Union Jack of Great Britain, and the French navy provided protection during the American Revolution. That all ended, however, when Britain recognized the independence of its former Atlantic seaboard colonies in 1783. One year later the United States Congress authorized the payment of tribute to the pirates. This protection scheme lasted for fifteen years; US payments in tribute and ransom money reached as much as $1 million per year, 20 percent of the US government's annual revenue in 1800.

Thomas Jefferson had always opposed these payments, arguing that they encouraged the Barbary pirates and their patrons to go for bigger prizes. His opinion was put to the test as soon as he became president in 1801; Yusuf Qaramanli demanded a new payment of $225,000, and showed he meant business by chopping down the flagstaff of the US Consulate. Jefferson refused, and all four of the Barbary states, led by Tripoli, declared war. This conflict, known either as the First Barbary War or the Tripolitan War (1801-05), would be the first time that United States forces saw overseas activity; in fact, the Americans were motivated by some of the same factors that would cause them to wage war against terrorism in the twenty-first century.

Algiers and Tunis backed down when a squadron of American frigates appeared off their shores, but Tripoli and Morocco remained committed to the conflict. The Americans were never seriously challenged at sea, and the fleet commander, Commodore Edward Preble, blockaded the Barbary ports and raided the enemy fleets. The Tripolitans enjoyed one victory in October 1803, when a storm drove an American ship, the Philadelphia, aground in Tripoli's harbor; the locals captured it, held its crew hostage, and began converting the ship for their own use. Four months later the Americans retaliated in a daring raid; a disguised ship, the Intrepid, sneaked into the harbor with a group of sailors, led by Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, and they burned the Philadelphia before the Tripolitans could use it against them. In July 1804 Preble sent the Intrepid back to Tripoli, this time as a fire ship full of explosives. The plan was to blow up the Intrepid in the middle of the enemy fleet, but it was destroyed, either by accident or by enemy guns, before it reached its target.

In March 1805, the American consul William Eaton launched a land campaign against Tripoli, marching from Alexandria with eight United States Marines, 38 Greeks, 300 Berber mercenaries, and Yusuf Qaramanli's brother Hamed, who would become the new pasha if the little army succeeded. They advanced 600 miles, captured the port of Derna, and got as far as Benghazi before they received news that the war was over.(5) The expedition was technically a failure, but it earned immortality in the opening line of the US Marines' Hymn: "From the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli."

Jefferson and the pasha of Tripoli signed a treaty ending the war in June 1805; the US Senate delayed ratification of the treaty for a year, because it still required that the United States pay ransom for sailors taken hostage by Algiers. In fact, many Christian nations continued to pay tribute to Tripoli, though the Americans no longer did. All that the First Barbary War did was show that the United States was able and willing to protect its interests, even thousands of miles from home. In 1807, the Algerians resumed the practice of capturing American ships and holding them and their crews for ransom. By this time, the Americans were distracted by deteriorating relations with both the French and the British, culminating in the War of 1812, so Algiers was put on the back burner for the time being. After the War of 1812 began, the British navy expelled American ships from the Mediterranean, and the dey of Algiers declared war on the United States for failing to pay its required tribute.

America couldn't do anything about the Barbary challenge until 1815, after the War of 1812 had ended. The Second Barbary War went much quicker than the first, lasting only three months. A force of ten ships, under the command of two heroes from the first war, Commodore Stephen Decatur and Commodore William Bainbridge (the captain of the Philadelphia), battered the Algerian fleet and killed its admiral off the coast of Spain, and captured hundreds of prisoners in an attack on Algiers itself. This was all the North Africans could take, and in June Decatur bargained for a treaty where Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli agreed to pay $81,000 in reparations, and to stop demanding any future bribes, whether or not they were called tribute. There was a tense moment when the dey's officials begged Decatur to keep on sending a small amount of gunpowder as tribute, and Decatur warned that it would come to them from a cannon: "If you insist on receiving powder as tribute, you must expect to receive BALLS with it."

The Barbary pirates would not give the Americans any more trouble, but as soon as Decatur left, the dey renounced the treaty. This prompted an Anglo-Dutch fleet to come to Algiers in the following year, and nine hours of bombardment was enough to cripple the dey's corsairs and extract from him a second treaty, in which British tribute payments were reduced to an annual £600 fee for consular privileges, and the dey agreed to stop enslaving Christians. However, this would not end European interest in North Africa; in the case of the French, European involvement was just beginning.

The Golden Age of African Exploration Begins

Africa had been the first continent explored by Europeans, back in the fifteenth century, but it was still a largely unknown place as the nineteenth century began. Every European nation had cut back on its involvement in Africa, once it was learned that Asia and the Americas had more easily obtained wealth. In America, merchants, missionaries, conquering armies and settlers had followed close behind the explorers, but in Africa, Europeans kept their contacts to a minimum; they preferred to trade from the safety of their ships, and when they did go ashore to build a fort, it was to keep other Europeans out, not to rule over the natives. On maps of sub-Saharan Africa, the coast was well-charted, but most of the interior was still blank. In the blank areas, Europeans no longer expected to find monsters or Prester John, but they still dreamed of fantastic discoveries like King Solomon's Mines or the Elephant's Graveyard, a place where elephants went to die, leaving behind a fortune in ivory tusks. In the 1730s, the English satirist Jonathan Swift wrote that:

". . . geographers, in Afric-maps,

With savage-pictures fill their gaps,

And o'er uninhabitable downs

Place elephants for want of towns."

They had a very good reason to stay away--Africa's diseases and parasites, especially malaria. Mortality was worst in West Africa, where typically malaria killed half of the Europeans who came ashore every year. Going inland didn't increase your chances, either--once you got past the disease-ridden jungles on the coast, there were fierce Moslem tribes, most of them implacably hostile to Christians. Europeans came to call West Africa the "White Man's Grave," and warned of the danger with verses like this:

"Beware, beware, the Bight of Benin,

For few come out, though many go in."

The main exception to this rule was the Anglo-Dutch colony at the Cape of Good Hope, which was far enough from the tropics to allow a European-style settlement to grow and prosper. The Portuguese were also doing fairly well in Angola and Mozambique; after living there for three hundred years, they had produced a disease-resistant mulatto community that numbered 3,000 by the mid-nineteenth century. However, they kept to the coast, because the Portuguese government discouraged travel in the interior, feeling that this should be left to the pombeiros, black and mulatto agents who knew how to get along with the natives. Typically, the pombeiros in both Angola and Mozambique would lead caravans 300 to 400 miles inland, to a garrisoned marketplace called a feira, where Africans would bring their goods to trade with the Portuguese. Then when finished, everyone returned to their homes. What this meant was that there were still 800 miles of completely unexplored territory between the innermost feiras. One of the first to try crossing the gap was Francisco de Lacerda, who had previously explored the Cunene River, in southern Angola (1787). In 1798 he went up the Zambezi from Mozambique; he made it to the capital of Mwata Kazembe, the most important of the interior kingdoms that Portugal traded with, but then died near Lake Mweru, and his expedition turned back. It was two pombeiros, Pedra Baptista and Amaro Jose', who succeeded in making the crossing by going in the opposite direction, from the Bihe' Plateau of Angola to the Zambezi (1814).

Just how dangerous Africa could be was shown by the British explorers who tried to map the Niger River. It wasn't only the Zambezi whose course was largely unknown; Europeans didn't know much about any major rivers in Africa. Consequently, one of the goals of the early explorers was to find out where the Niger went, and where the Nile and Congo came from. In 1791 Daniel Houghton followed the Gambia River to its source, crossed the Senegal River, and was lured into the desert by the local tribesmen; they stole his possessions and left him there to die. Four years later, the Scotsman Mungo Park arrived. He followed Houghton's trail to the place where the natives disposed of him, and at nearby Benown he was captured. After being held prisoner for three months, he escaped and made his way southeast. He found the Niger River at Segu in 1796, traveled 80 miles downstream to Silla, and returned to Europe because his supplies were exhausted. Back in Great Britain, Park published an account of his trip, Travels in the Interior of Africa (1799), which is still in print.

In 1805 Park tried again. This time he brought a platoon of British soldiers, knowing that he would be killed if the Moslems captured him again. The soldiers brought boat-building supplies, and the plan was to buy or build a boat at Segu, get it into the middle of the Niger, and follow the stream all the way to the sea without going ashore; the forty-six muskets of the soldiers would be enough firepower to deal with anyone who tried to stop them. The only problem with the plan was that Park had been in Africa long enough to become immune to malaria, but his companions hadn't. Most of the soldiers died on the march to Segu. By the time Park got his boat, he did not need a large one, because only four soldiers were still alive. Still, once the boat was launched, they managed to navigate the river for a thousand miles, until Park and his company drowned in the Bussa rapids of Nigeria, while escaping a native attack. Ironically, the attackers were a non-Moslem tribe that mistook him for a Moslem invader. His journal from the first part of the second expedition was published in 1815, with a postscript from his African servant Isaaco, but he had not reached the end of the Niger River, so people still speculated about that. Did it keep on going east until it reached the Nile, as medieval Arabs had believed? Did it go into the large delta on the Slave Coast that contemporary Europeans called the Oil Rivers? Did it curve south through Cameroon to join the Congo (Park's view)? Or did it flow into Lake Chad, without its waters reaching the ocean at all?

Four subsequent expeditions to the Sahel failed to trace the rest of the Niger's course. A fifth one, led by Richard and John Lander, finally succeeded (1830-32). Landing at the Bight of Benin, they marched due north until they reached the Niger at the Bussa rapids. Then they followed the river all the way to the sea. This proved once and for all that the Niger wasn't a tributary for any other river, and that the Niger and the Oil Rivers were the same stream. There were a few questions about a river the Lander brothers discovered, the Benue, which flows into the lower Niger from the east; to some it looked like it came out of Lake Chad. This was solved by two other explorers, an Englishman named James Richardson and a German named Heinrich Barth. Starting from Tripoli in 1849, they headed south across the Sahara until they reached Lake Chad, where Richardson died. Taking command, Barth led an excursion south to find the source of the Benue, then moved westward, exploring the middle section of the Niger as far as Timbuktu (1852-53). This showed that no river flowed out of Lake Chad, and the Chari was the only significant river flowing in.

By this time, a solution had been found for the malaria problem. In 1847 a British naval surgeon discovered that a daily dose of quinine reduced the effects of sub-tertial malaria, the deadliest type of that disease. The effectiveness of this drug was shown in 1854, when a twelve-man team sailed up the Niger and Benue Rivers and back without losing anybody, something that would have been impossible previously. When Europeans began to routinely equip themselves with medikits containing quinine, Africa lost its first line of defense.

Shaka Zulu

Not all of South Africa's problems were caused by the arrival of the white man. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, a major famine led to an explosion of violence that lasted for a generation, called the Mfecane or "Time of Troubles" (also called the Difaqane). In fact, the primary reason for Xhosa raids into the Cape Colony was to get away from the troubles behind them.

At the center of the storm was the Nguni tribe. To protect themselves and their cattle, the Nguni united under a single chief, Dingiswayo of the Mthethwa clan. Dingiswayo rose to the top because he was a skilled and innovative leader, who organized his warriors into impis (regiments), and gave each impi distinctive clothing with matching shields. However, one of his officers was even better at those skills--Shaka, who came from a minor clan called the Zulus.

The son of Senzangakhona, the Zulu chief, Shaka was expelled from the clan, along with his mother Nandi, when the marriage between Senzangakhona and Nandi failed. They went to live with the Langeni, Nandi's clan, but there they were less welcome than with the Zulus. Shaka grew up bitter and lonely among people who despised and tormented both the single mom and the fatherless child. When he got the chance, he left to become a herder for the Mthethwa, and later joined Dingiswayo's army. Here he found an outlet for his frustrations, and did so well in fighting that he rose rapidly in the ranks. Dingiswayo liked Shaka, so when Shaka's father died in 1816, Dingiswayo ordered the assassination of Sigujana, Senzangakhona's chosen heir, and made Shaka chief of the Zulus. The first thing Shaka did as chief was get revenge on those responsible for his tough childhood, ordering the massacre of many Langeni. Two years later, Dingiswayo was in turn killed by a tribe that refused to submit to his authority, and in the civil war that followed, Shaka first seized control of the Mthethwa, then eliminated the ruling families of most of the other clans, and added their people and resources to his own. As a result, the tables were completely turned; the Nguni became part of the Zulu tribe, and have remained so ever since.

Military innovations were the key to Shaka's success. He imposed far more discipline on his impis then Dingiswayo had, forcing warriors to march barefoot (in land that is often thorny) most of the time, and forbidding them to marry until they had distinguished themselves in battle or their term of service ended. Each regiment was divided into four formations, named after the parts of a bull: the main body of troops was called the "chest," two bodies called the left and right "horns" ran ahead to outflank the enemy, and a reserve force called the "loins" was under orders to hold back until the other three were engaged in combat. Up to this point, African warfare was mainly a matter of getting close enough to an enemy to throw spears; casualties tended to be light, with most of those on the losing side living to fight another day. Shaka thought this way of fighting was ridiculous, and replaced the assegai with a short, wide-bladed spear which couldn't be thrown, forcing warriors to charge and stab an enemy in hand-to-hand combat. He called the new weapon an iKlwa, after the sound it made when pulled from a corpse, and added a larger shield, which the warriors could use to knock an opponent off balance. Putting all this together turned the Zulu army into an efficient killing machine, which no other tribe could beat; soon the non-Zulu tribes were fleeing the Natal region, trying to put as much distance between them and the Zulus as possible.(6)

The only known portrait of Shaka that was done in his lifetime. We don't know how much it really looked like him, but he is said to have liked it.

As Shaka's power grew, so did his cruelty. Rarely a day went by when he didn't show how little regard he had for human life; to sneeze in his presence or give him a dirty look ran the risk of getting killed on the spot. Once he ordered two thousand warriors to prove their loyalty by marching into the sea; they feared him so much that they obeyed--and were drowned. Nor was he much kinder to women. He never had a child, out of fear that an heir would someday turn against him, but he kept a harem of as many as 1,200 women, and on one occasion he came back unexpectedly early from a journey and had 170 young men and women put to death on a suspicion of adultery.

The only people he felt generous toward were the Europeans, since at this stage they could not be a threat to his kingdom. In 1824 he allowed a small group of Englishmen and Hottentots to build a settlement at Port Natal. They were soon joined by "coloreds," renegade Zulus, and refugees from the Mfecane. The settlement was too far away to receive help from the Cape Colony, so it only existed at Shaka's pleasure, and the settlers did whatever they could to stay on the Zulu king's good side. Shaka didn't fear the single-shot muskets and rifles currently used by white hunters and soldiers; in the time it took a European to reload his gun, he reasoned, a Zulu warrior could easily run up and dispatch him with a spear. Still they were useful in finishing off his enemies, so Shaka used the Europeans as mercenaries, and gave them grants of land and cattle in return. Most of what we now know about Shaka, in fact, comes from the accounts of two white adventurers who learned to speak the Zulu language fluently, Henry Francis Fynn and Nathaniel Isaacs.

While on a hunt with some Europeans in 1827, Shaka received news that his mother was dying. Nandi's death caused him to become completely unhinged. To be sure that there would be mourning, he ordered a general massacre that didn't stop until 7,000 were dead. Then for a year he wouldn't allow the planting of crops, and banned the consumption of milk, as if he was trying to starve his own people. All pregnant women were slain with their husbands, and even a considerable number of cows were killed, so that calves might know what it was like to lose a mother.

After that, Shaka had made so many enemies that things could only go downhill from there. A diplomatic mission to the British at the Cape, with Nathaniel Isaacs as the Zulu ambassador, was an embarrassing failure; London didn't want anything to do with a chap who had caused so much trouble. In 1828 he sent the impis on a raid that went south all the way to the borders of the Cape Colony, and when they returned, he sent them on another raid just as far to the north, instead of giving them the rest they expected. This was two much for the warriors, and on September 24, 1828, two of Shaka's half-brothers, Dingane and Mhlangana, assassinated the king, threw his body into empty grain storage pit, and filled it with stones.

Dingane now seized the throne, but neither him nor any subsequent Zulu kings ruled as effectively as Shaka did. According to one story, Shaka's last words were directed to his murderers: "You will not rule this country, the white people have already arrived."(7) It took another fifty years for Europeans to take over the Natal region, but otherwise Shaka was right.

Madagascar: The Merina Monarchy

Shaka wasn't the only empire-builder active in Africa during the 1820s. Two others were Radama I of Madagascar, and Mohammed Ali of Egypt. The story of Madagascar is easier to tell than that of Egypt, so we'll do Madagascar first.

Adrianampoinimerina, the ruler of Madagascar's dominant state, commanded his son Radama to "take the sea as frontier for your kingdom." Radama worked hard to do just that, conquering the Antaimoro kingdom on the east coast and winning the submission of his main rival, Betsileo. By the end of Radama's short reign (1810-28), two thirds of Madagascar was under Merina control, the exceptions being the southern coastal region, which is the most barren part of the island, and the Boina kingdom in the northwest. In 1817 he signed two treaties with Great Britain, accepting British money and arms in exchange for abolishing the slave trade on Madagascar. He also allowed British missionaries to come into the country, who had the side benefit of introducing the Latin alphabet when they translated the Bible into the Malagasy language, making modern education possible.

Radama had twelve wives, and the chief one, Ranavalona I, deserves attention because she was the first Malagasy matriarch to rule the whole island. The story of this queen began forty years earlier, when the uncle of Adrianampoinimerina plotted to assassinate him, and one of the king's servants learned of the plot in time to stop it. Adrianampoinimerina rewarded the informer by adopting his daughter Ranavalona into the royal family, and when the future king Radama was old enough to marry, Ranavalona became his chief wife. However, this arranged marriage appears to have been a loveless one, for the queen had no children, and Radama liked his other wives better. Ranavalona especially resented how the royal family did not allow her to make any important decisions, so when Radama died in 1828, she abruptly seized power and killed anyone who disagreed with the idea, starting with a nephew of the late king who was the rightful heir. It took a year to hunt down all the rivals, so she had two coronations, first a traditional one in which she was annointed with the blood of a freshly killed bull, and then after all opposition was quenched, she had a more modern coronation where she wore a French-style dress. To those attending the second ceremony, she said, "Never say, 'She is only a feeble and ignorant woman, how can she rule such a vast empire?' I will rule here, to the good fortune of my people and the glory of my name! I will worship no gods but those of my ancestors. The ocean shall be the boundary of my realm, and I will not cede the thickness of one hair of my realm!" In 1840 she annexed Boina, thereby completing the unification of Madagascar.

Those who hadn't converted to Christianity, especially the pagan priests and much of the upper class, felt threatened by the new religion and the young educated men it produced, and Ranavalona took over with their help, so during her reign a reactionary trend set in. She cancelled the treaties with Great Britain, ended trade with the French, and ordered the missionaries to leave. Some Christians were killed in the persecution that followed, but the stories missionaries told of the atrocities in Madagascar may have been exaggerated. Most of the time she didn't kill Christians outright, but looked for more creative ways to bring back the old-time paganism. These included torture, progressive amputations, forced marches through malarial swamps, and selling Christians into slavery. On top of all that, she did away with trial by jury and brought back trial by ordeal. With trial by ordeal, the defendant was made to drink the juice of a poisonous plant called tangena, and eat three pieces of chicken skin. If he threw up afterwards, he was judged innocent; if he died or failed to puke, he was guilty.

Naturally the British and the French were upset at being locked out. To show they weren't going to go away quietly, the French bombarded and occupied the eastern port of Tamatave in 1829, and held it briefly until enemy gunshots and malaria killed off most of the troops. In 1835 a combined British-French army made a second attempt on Tamatave, and this time they fared even worse. Ranavalona cut off the heads of twenty-one dead Europeans, and stuck them on pikes on the beach facing the ocean, as a warning not to mess with her again. Europeans got the message, and stayed away from Madagascar as long as it was ruled by a "Female Caligula," but nearby islands remained fair game; in 1841 the French took Mayotte in the Comoros (which had been conquered a few years earlier by Boina's King Adriansouli), and Madagascar's offshore island of Nosy Bé. Queen Ranavalona still wouldn't yield, and suspended all overseas commerce, except with the United States.

Despite all this, Ranavalona wasn't a total xenophobe, and kept a few foreign advisors around to make the country self-reliant. The most remarkable of these was a Frenchman, Jean Laborde, who built a center for manufacturing and agricultural research at Mantasoa, near Antananarivo; eventually it employed 20,000 workers producing guns, glass, soap, silk, tools and cement.

Today's Malagasy have mixed feelings about Ranavalona I. One the one hand she successfully resisted colonialism, keeping European invaders out of her country for as long as she lived, something few African rulers could do in the nineteenth century. But it came at a terrible price, one which gave her the title "Ranavalona the Cruel." And as with Shaka, the brutality got worse as time went on. Because of her military campaigns, deaths caused by forced labor, and her Draconian system of justice, the population of Madagascar is estimated to have dropped from 5 million to 2.5 million in the 1830s.

At least once the lives lost were simply wasted. In 1845 the queen ordered a buffalo hunt. This was a traditional ritual which required all the nobles to come with the monarch, and each of them had an entourage of servants and slaves; soon 50,000 people were going on the expedition. To make the journey easier, Ranavalona commanded that a road be built, but there was little advance planning about how to feed either the road workers or the unwieldy expedition. Consequently road workers died (which were immediately replaced) and the price of rice skyrocketed in the area near the road. As Keith Laidler put it, "The royal road was littered with corpses, most of which were not even buried, but simply thrown into some convenient ditch or under a nearby bush. In total, 10,000 men, women, and children are said to have perished during the 16 weeks of the queen's 'hunt.' In all this time, there is no record of a single buffalo being shot."

In 1853 the Europeans paid Ranavalona $15,000 in compensation, and she lifted the trade ban, only to see foreigners, local Christians and others plot a coup against her. They wanted to replace the queen with her son, Radama II, but Radama sided with his mother, and thus was spared when the queen retaliated against the plotters. Then Ranavalona died peacefully in 1861, and Radama became king legally. However, this Radama was too peaceful and pro-European, so he only lasted on the throne for two years. He signed treaties with the British and French that gave them exemptions from tariffs and other duties, and promised perpetual friendship with France. Then he tried to remove the leaders of two prominent clans, but instead the nobility strangled him, and crowned his wife, Rasoherina, in his place.

The new ruler, however, was a queen in name only; real power went to the pro-European majority in her council, especially the prime minister, who promptly married her. One year later, he was overthrown by his brother, the army commander Rainilaiarivony, who became the next prime minister, and secured his position by marrying the queen, and both of the queens that came after her, Ranavalona II (1868-83) and Ranavalona III (1883-97). The missionaries returned, and Rainilaiarivony became a Protestant Christian in 1868, followed by the queen a year later. By the 1880s Roman Catholic missionaries from France were also active, there were more than 150,000 Christians in Madagascar, and the percentage of children attending school in Madagascar was almost as high as in Europe. But the old pagan beliefs and customs, like the Merina festival of Famadihana (the digging up, rewrapping, and reburial of the bones of the dead), survived, and are still practiced even today.

Mohammed Ali Modernizes Egypt

For more than forty years, Mohammed Ali was the most important individual in northeast Africa and much of the Middle East. Today Egyptians see him as the man who began the modernization of their country, quite a remarkable feat when you consider that he wasn't an Egyptian; he was born in the Balkan province of Macedonia, in 1769. He came to Egypt at the age of thirty, as an officer in the Turkish army sent by the sultan to restore control after Napoleon Bonaparte left. If nothing else, Napoleon's expedition showed how weak the Ottoman Empire had become, compared with its Christian opponents. Consequently, once he was in charge, Mohammed Ali used all his talents toward the goal of catching up with the West. Unlike previous African leaders, he saw that it would take more than acquiring modern firearms to build a first-rate military power; he would have to completely modify the armed forces and the supporting industries.

Mohammed Ali made sure that the mostly Albanian soldiers were more loyal to him than to the distant sultan, and used them to make himself the most powerful man in Cairo. In 1805 he won the sultan's recognition as viceroy or governor of Egypt, but his position was still threatened by the previous rulers, the Mamelukes. In 1811 the sultan, Mahmud II, called for his help in putting down a rebellion on the other side of the Red Sea, that of the Wahhabis. Mohammed Ali couldn't send troops until he solved the Mameluke problem, so he did it in a characteristically ruthless fashion, eliminating them as a social class; he invited 470 Mameluke leaders to a banquet, and had his soldiers massacre them after they ate.(8) In Arabia, Mohammed Ali's troops proved to be better than those of the sultan; first they secured the holy cities, Mecca and Medina, then they invaded the Wahhabi home base in the interior. By 1818 most of Arabia was under their control, the main exceptions being the Rub al-Khali ("Empty Quarter") and Oman.

Next on Mohammed Ali's busy agenda was the conquest of the Sudan. In 1820 his son Ismail led a small force of 4,000 men up the Nile, which captured Dongola (see the previous footnote), and went on to overthrow the Sultanate of Funj in 1821.(9) At the junction of the Blue and White Niles, they founded the city of Khartoum, which became Egypt's base of operations in the new territories. Nearly 400 miles south of Khartoum, further progress was delayed by the Shilluk, a small tribe with a centralized kingdom. The Shilluk were finally overcome in a series of expeditions between 1839 and 1841, led by a Turkish sea captain named Selim. The next obstacle after that was the Sudd, Africa's greatest swamp. Up to this point no boats had gotten through the Sudd; it is a place infested with crocodiles and hippopotami, where the White Nile splits into various small streams and lagoons, and masses of vegetation form floating islands that change the course of the waterways every year. Still, persistence paid off, and in 1842 Mohammed Ali's men succeeded in penetrating the Sudd. From here they passed through the country of the Dinka and Nuer tribes, and were finally forced to stop at Gondokoro, near modern Juba and a thousand miles upstream from Khartoum; past this point the White Nile was no longer navigable (some maps call it the Mountain Nile here). Together, the Arabian and Sudanese campaigns gave Mohammed Ali a larger empire than those the rulers of ancient Egypt and Nubia ruled, even in the best of times.

To replace the losses the army had suffered in these campaigns, Mohammed Ali began conscripting Egyptian peasants in 1822. During the past 2,000 years, the rulers of Egypt did not think the fellahin were useful for anything but working the fields; they controlled and defended the country with non-Egyptian troops (Greeks, Romans, Bedouins, Mamelukes, etc.). Equipping the fellahin as a modern army, and bringing in European (mostly French) military experts to train them, was the most revolutionary thing he did; this caused the first stirrings of nationalism among the Egyptians since pharaonic times. It's no coincidence that 140 years later, the leaders who overthrew the monarchy and established the government of modern Egypt would come from the army.

Along with the creation of the new army came a number of civil reforms to match. The amount of irrigated land was greatly increased, cash crops like cotton were introduced to increase revenue, and modern factories and schools were built. Despite all this, Mohammed Ali never really found a way to pay for his activities. Egypt still got most of its income from agriculture, in a time when products made in factories earned a bigger profit. This meant that industrialized nations had a definite economic advantage. Britain had already industrialized, France industrialized during Mohammed Ali's reign, and other Westerners like the Americans and the Dutch were beginning to industrialize. Unlike Egypt and the Ottoman Empire, these countries had the resources to send out unprofitable expeditions, and wage unprofitable wars. In fact, the main reason why Mohammed Ali invaded the Sudan was to make up for the growing trade deficit, via Sudanese gold, ivory and slaves. He kept telling his troops to look for the source of the gold that went into the treasure hoards of the pharaohs, but they never found it, and hunting for elephants and slaves did more harm than good to the Sudanese.(10) In the end none of the newly won territories brought in enough revenue to pay for the cost of their conquest. Furthermore, because all power was concentrated in Mohammed Ali's hands, he couldn't blame his failures on anyone else. We'll see later on how that led to trouble for Egypt, after Mohammed Ali bequeathed his job to less capable successors.

By the early 1820s, Mohammed Ali was clearly more powerful than his Ottoman overlord, an excellent example of the tail wagging the dog. In 1821 he began building an Egyptian navy at great expense, because he realized that sea power was just as important to European success as industrial power; without ships, Westerners wouldn't be able to meddle in Africa at all. The same year saw a major revolt break out in Greece, forcing Sultan Mahmud II to call for help again. The Greeks were no match for the force led by Ibrahim Pasha, another son of Mohammed Ali, but Britain, France and Russia teamed up to support the Greeks, giving Mohammed Ali his first defeat.(11)

Mohammed Ali had expected Constantinople to at least pay his expenses, and originally the sultan had promised him Syria, but he reneged on this when the war ended in a Greek-European victory. In response, Mohammed Ali launched a campaign to conquer the rest of the Ottoman Empire, starting with Ibrahim Pasha landing the Egyptian army and navy at Jaffa (next to modern Tel Aviv) in 1831. Over the course of 1832 Ibrahim won one victory after another, at Acre, Damascus, Aleppo, and Konya. He finally halted his march at Kutaya, just 150 miles from Constantinople, when European pressure and a letter from his father compelled him to stop. All involved parties signed a treaty in May 1833, which gave the entire Levant over to Ibrahim and made him tax collector for the Turkish city of Adana, while Egypt continued to pay an annual tribute to Constantinople. Ibrahim tolerated the religious minorities in his new domain, especially the Christians, but was heavy-handed when it came to conscriptions and tax collecting, leading to many desertions and a revolt in Syria.

A second war between Mohammed Ali and Sultan Mahmud broke out in 1839, when the sultan ordered Egypt to get rid of its fleet and reduce its army. Mohammed Ali refused, a Turkish army marched into Syria, and at Nizib, on the banks of the Euphrates, Ibrahim Pasha won his last great victory. Within a matter of days the sultan died, and the Ottoman navy sailed to Alexandria and went over to the Egyptians. The new sultan was only sixteen years old, and it looked like a golden opportunity to take over the whole empire. Instead, the European powers intervened again, sending diplomats who stated in no uncertain terms that they weren't going to let Mohammed Ali do it. The British in particular didn't want to see control of the entire Middle East pass from a weak power like Turkey to a strong power like Egypt, because Great Britain was now heavily involved in India, and the Middle East was on the most direct path between India and Europe. In 1840 a British squadron came to Beirut and demanded that the Levant be evacuated. Ibrahim led his army back to Egypt, and in 1841 Mohammed Ali accepted a new treaty that set the maximum size of the Egyptian army at 18,000 men; it also set Egypt's annual tribute at 9 million French francs and prohibited the building of warships without the sultan's permission. The treaty also forced Mohammed Ali to give back the Levant, but his rule over the Sudan was officially recognized, and--what he had wanted most of all--the governorship of Egypt, and the title of khedive (viceroy) would remain permanently in his family.

The Abolitionist Triumph

We noted in the previous section that Great Britain could afford to fight unprofitable wars. Perhaps the best example of this was the campaign against slavery, which the British took up wholeheartedly as the nineteenth century began. Now that the Abolitionists had won the hearts of Britons at home, the British outlawed the slave trade in 1807, and began putting pressure on the other Western powers to do the same. Consequently the United States followed suit in 1808, and at the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the rest of Europe agreed to end the business.

Now, passing new laws is useless if you aren't going to enforce them. In 1808 the British showed they meant what they said by sending ships to patrol the Atlantic coast of Africa, with orders to stop and search any ship, no matter what flag it was flying, if they suspected those ships were carrying slaves. However, the number of slaves transported from Africa continued to rise for a while (in fact, the slavers could charge a higher price, now that they had to smuggle their cargo to their customers); the peak came in the 1830s, when 135,000 slaves were being shipped every year. The trade routes changed, too; instead of taking the "Middle Passage" from Nigeria to the West Indies, most slave ships now went from Angola to Brazil. On a positive note, slave owners in the New World began treating their slaves better, once they realized that they would be harder to replace if they died.

Three new cities and one new nation were created as part of the anti-slavery campaign. The first of the former was Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone. Both the Americans and the British had recruited and armed slaves during the American Revolution, usually by promising to free them when they completed their term of service. After the war those ex-slaves who had fought for the British ended up in Canada, where the climate was too cold for them to prosper. Britain founded Freetown for them in 1787, but a disease epidemic wiped out the first community, so it was reestablished in 1792. Then the organization in charge, the Sierra Leone Company, went bankrupt, so only a thousand Canadian unfortunates were relocated by 1808. Things turned around in that year when the British government took over, setting up a naval base and anti-slave trade courts in Freetown. Over the course of the next fifty years, the Royal Navy rescued about 100,000 slaves, who were called "recaptives,"and dropped off 80 percent of them at Freetown. Of these, half tried to go home again, but very few of them made it; it was the 40,000 who stayed that made Freetown a successful colony. And because the Abolitionist movement was founded and led by church leaders, the former slaves became enthusiastic converts to Christianity; that would give a boost to the efforts of Christian missionaries in West Africa.

It was a similar story with Liberia, Africa's American colony. In 1816 the American Colonization Society was founded to resettle freed slaves who wanted to return to Africa. This organization got a grant of land from the tribe ruling the mouth of the Saint Paul River in 1821, and here they built Monrovia, named after US President James Monroe. The colony grew steadily, but the settlers had trouble getting along with their sponsors in the United States, so in 1841 Joseph Jenkins Roberts became the first black governor; then in 1847 Liberia became an independent republic, with Roberts as its first president. Britain recognized Liberia in 1848, and France did in 1852, but paradoxically, the United States delayed recognition until 1862.

At the time of independence, Liberia had 80,000 natives (from the tribes that had lived there originally), 15,000 former slaves from the Americas, and 6,000 unwilling immigrants, slaves rescued by US anti-slavery patrols like the British ones that operated out of Freetown. Only 5 percent of today's Liberians claim American descent (call them Americo-Liberians or American-Africans), but they had a firm grip on the country for more than 130 years, which did not begin to loosen until 1980 (see Chapter 9).

France abolished slavery in 1848, and a year later established a community for freed slaves, Libreville ("Freetown" in French), near the spot where Africa's Atlantic coast crosses the equator. It didn't serve this purpose very well, because by then the number of slaves rescued or returned was falling. In the end Libreville served better as the first French outpost in equatorial Africa, and as the capital of present-day Gabon.

Meanwhile on the Gold Coast, the British were pulling ahead of their rivals, though not entirely through their own choice. By selling gold dust to the Dutch for firearms, the Ashanti had become strong enough to conquer the Fante, the tribe on the coast, in 1807, and now they were a major threat to the European forts as well. The local British governor, Sir Charles M'Carthy, started a war in 1824 to liberate the Fante, but was defeated and killed. Britain sent reinforcements, the Ashanti were defeated in 1827, and in 1831 they agreed to abandon the coast. As for the forts, the British bought the Danish and Portuguese ones in 1850, and the Dutch ones in 1871, bringing the entire Gold Coast under British control. On the former Slave Coast, the British resolved a dispute between Benin and Dahomey over the island of Lagos by taking it for themselves in 1861.

As they increased their activities in the south Atlantic, the Royal Navy required an increased presence south of Freetown. In 1827 Britain leased the island of Fernando Póo from Spain, and turned it into a naval base. They gave it back in 1858, when an end to the trafficking of human beings across the Atlantic was in sight. The last slavers were black Brazilians, because Europeans and white Americans had gotten out of the slave business, leaving behind those who were less likely to arose suspicion. By this time, only three countries remained in the western hemisphere where slavery was legal. With the abolition of slavery in those countries (the United States in 1863, Cuba in 1886, and Brazil in 1888), the Atlantic market for slaves finally disappeared.

It took longer to grind down the slave market in the Indian Ocean. One reason for this was increased economic activity--the Swahili wanted more ivory and slaves, while the tribes of the interior wanted more guns. Another was an Arab revival under Oman's greatest ruler, Sayyid Said (1806-56). Between 1817 and 1828, a series of expeditions across the Arabian sea reestablished Omani rule over most of the Swahili coast, from Warsheikh in Somalia to Lindi in southern Tanzania. It took a few more years to subjugate the area, but when this was done Sayyid Said decided that his new territories were nicer than the old ones, so he moved his capital from Muscat to Zanzibar (1840). He also introduced clove trees from Indonesia, and this venture did so well that soon East Africa was producing more cloves than Southeast Asia. However, the clove plantations required workers, so Oman bought and sold as many as 100,000 East African slaves every year; Atkins Hamerton, a British consul, estimated in 1850 that 450,000 slaves were working just on the islands of Zanzibar and Pemba. Consequently, after 1840 British anti-slavery patrols spent more time on Africa's east coast; early in his reign Sayyid Said had signed a treaty promising to end Oman's involvement in the slave trade, and obviously he wasn't enforcing it.

When Sayyid Said died in 1856 his realm was split in two; one son, Majid, ruled from Zanzibar and another son, Thuwain, ruled from Muscat. Britain made Zanzibar a protectorate, by giving it the aid it needed to prevent Thuwain from reconquering it. With the British as the power behind Zanzibar's throne, the number of slaves trafficked on the Swahili coast finally declined. In 1873 Sir John Kirk, the British consul-general at Zanzibar, got Majid's brother and successor, Sayyid Barghash ibn Said, to sign a treaty banning the slave trade by sea and promising to protect all liberated slaves within the area he controlled. Finally in 1897, the legal status of slavery in Tanzania was abolished. There were some violations in various parts of the continent after that date (the Portuguese didn't suppress slavery in Mozambique until 1912), but for all practical purposes the enslavement of Africans had ended. Today only the Arabs of Mauritania still openly practice black slavery, though technically it is illegal there, like it is everywhere else.(12)

This may sound strange to modern ears, but only the blacks already overseas benefited from emancipation. All African kingdoms that had made a living selling slaves suffered an economic slump, even if they had tried to diversify their income with industries like palm oil and cloves.(13) The port of Mombasa, for example, didn't recover until after 1900, when the British built a railroad from there to Uganda. Nor were the primary victims of the slave trade better off; the slavers now had to get rid of a lot of unwanted human beings. They ended up doing the same things that they had done in the past when they could not sell their slaves; they had them executed if they were accused of a crime, or sacrificed if they weren't. Consequently, visitors to slaver states like Dahomey in the second half of the nineteenth century reported horrifying spectacles, convincing many humanitarians that Europe needed to conquer Africa before the Africans destroyed themselves. It was a bloodcurdling epilogue to one of the saddest stories in human history.

France Invades Algeria

There were many excuses given by Europeans for invading non-European lands during the age of imperialism, but the one the French used when they went into Algeria has to be one of the most absurd; the dey of Algiers was rude to a French diplomat. France was earning a good profit through trade with Algeria, using a fortified outpost near the eastern port of Bône as the French base of operations. However, the French were often late in making payments on their debts, so in 1830 Hussain III, the last dey, summoned the French consul and asked him when Paris was going to pay what it owed to two Algerian Jewish merchants who had sold wheat to France. Hussain then told the consul that the French must remove all cannon from their trading posts on Algerian soil, and that henceforth French merchants would have no privilege over other merchants. A heated argument developed--the dey later claimed that the consul had insulted both Islam and the Ottoman sultan--and he responded by hitting the consul two or three times in the face with a flyswatter he happened to be holding.

This was too much for French pride, so they sent 37,000 soldiers across the Mediterranean and landed them just west of Algiers. The French government claimed it was suppressing piracy, but the Barbary pirates had stopped being a menace fifteen years earlier. And the French people didn't support this overseas venture; in fact, they overthrew King Charles X after the army left Paris. However, the military phase of the campaign was a complete success; three weeks after the French arrived, the dey surrendered Algiers. The French commander promised to respect local customs and keep his troops out of mosques, but before long they were turning mosques into churches, as the first step in a program to turn Algeria into another France.

Once the French decided to keep Algiers, they realized they couldn't do so while the surrounding countryside was against them. The locals resisted violently when land was taken away from them, and while the French managed to conquer most of Algeria's coast by the end of the 1830s, the Algerians found a charismatic leader in Abd el-Kader, the son of a holy man; in 1832 he launched a guerrilla war from the Atlas mountains. To deal with him, France eventually committed a third of the French army to Algeria, and put a ruthless general, Thomas Bugeaud, in charge of it. As Abd el-Kader drew the French into the interior, they inflicted a series of atrocities that could only be justified because they weren't happening in Europe. Bugeaud put it this way in 1846: "We have burnt a great deal and destroyed a great deal. It may be that I shall be called a barbarian, but I have the conviction that I have done something useful for my country. I consider myself above the reproaches of the press." Abd el-Kader was captured in 1847, but resistance continued to smolder for a generation. Not until 1879 was all of Algeria declared safe for tourists, at which time a civilian government replaced the military one. Still, the French required 100,000 troops to keep the country pacified, whereas the deys had managed to do it with 15,000.(14)

Behind the soldiers came colonists from southern Europe--Italians, Spaniards and Maltese as well as French. Most were attracted by the prospect of doing business with the Algerians, or they simply wanted to find better jobs. By the mid-1850s they numbered 170,000, almost as many as the white settlers in South Africa; by 1880 there were 350,000. The French among them kept in touch with friends and relatives back in France, and in the twentieth century they had far more influence on French politics than their numbers would suggest.

As time went on, Algeria became France's most cherished colony; the French regarded it the same way as the British regarded India. For that reason, the French began to look covetously at surrounding territories like Tunisia and Morocco, as buffer states to defend Algeria with. In 1878, an international conference was held in Berlin to deal with the latest Balkan crisis, the Russo-Turkish War, and in the thinking of that time, every European nation except the German hosts felt they had to have a piece of the Turkish empire whose future they were discussing; the Russians got part of Armenia, and the British took Cyprus. The French put forth a claim to Tunisia, which they made into a protectorate in 1881.

Meanwhile to the east, a power struggle arose in Libya following Yusuf Qaramanli's death in 1830, and the Bedouins of the Fezzan declared their independence from Tripoli. The Ottoman government decided that this would be a good time to reassert its authority, before Mohammed Ali beat the sultan to it. In 1835 a new governor arrived from Constantinople, and he declared that the Qaramanid dynasty was now deposed. However, it took until 1842 to reconquer the Fezzan.

In the end the interior was stabilized not by a ruler in Tripoli, but by a new fundamentalist movement, the Sanussi Brotherhood. Founded in 1843 by Muhammad al-Sanussi (1790-1859), it called for a return to the primitive Islam of the seventh century, and became very popular among the nomads because al-Sanussi was an excellent leader and diplomat. The first school of the order was established in Cyrenaica, and within a generation there were followers as far south as Bornu and Wadai, and as far west as Timbuktu. Sanussi members promoted agriculture and commerce as well as religious propaganda, so the caravan routes to Bornu and Wadai, which were badly disrupted following the death of Bornu's Muhammad al-Kanemi in 1837, soon became the busiest in the whole Sahara. The Ottoman Empire was forced to recognize Sanussi authority in the Fezzan because those caravan routes were the region's prime asset.

Under attack first from the Fulani in the west, and then from the kingdom of Wadai in the east, the old kingdom of Bornu declined rapidly. A civil war broke out in 1846, with the last mai, 'Ali V Dalatumi, on one side, and al-Kanemi's son Umar on the other side. Wadai intervened on behalf of the mai, but Umar won, ending the reign of one of the longest-lived dynasties in history. Umar discarded the pre-Islamic title of mai for the humbler title of shehu (from the Arabic shaykh or sheikh), but he didn't rule with the vigor of his father; his advisors came to run everyday affairs, and Umar's sons were just as much puppet kings as the last Saifawa mais had been.

Aftershocks of the Mfecane

Southeastern Africa remained in turmoil for more than a decade after Shaka's death. Among those individuals who fled the zone of anarchy, one of the most successful was Mzilikazi. A former lieutenant of Shaka, Mzilikazi headed west over the Drakensberg mountains when Shaka suspected him of stealing cattle. Along the way, he collected other Mfecane refugees, molding them to form a new tribe called the Matabele or Ndebele. Across the Drakensberg they found a fertile, temperate plateau, the High Veld, and settled down here. Previously this had been an underpopulated, quiet place, but that would change quickly when the Boers moved into that area, too.

Another group that headed west, the Kololo, went all the way to Botswana, throwing that area into disorder when they defeated the people who had lived there previously. They were enemies of the Ndebele, and had an ongoing struggle with them. When the Kololo got the worst of a battle in 1823, their leader, Sebetwane, took them north into what is now Zambia, and conquered Barotse, a small kingdom belonging to the Lozi tribe, on the upper Zambezi River (1840).

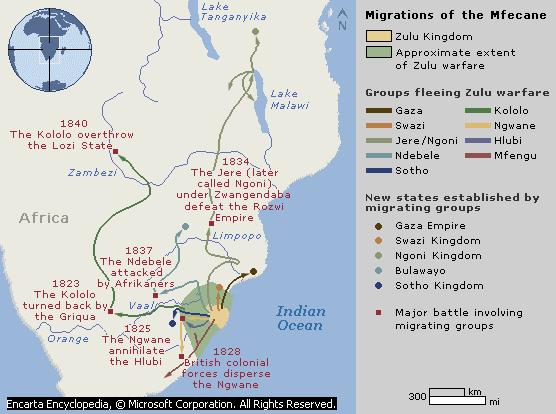

Areas affected by the Mfecane.

Other refugees headed south, and ran into the zone Europeans were settling; the only tribe that succeeded in finding a new home here was the Sotho. They had a superb leader named Moshoeshoe (1815-68), who was brilliant both as a warrior and as a diplomat. From his location in the western Drakensberg, he had to deal with raids from both Shaka and Mzilikazi. First he took his people to the mountain of Butha-Buthe, but after several battles he found a better location on top of another mountain, Thaba Bosiu, and led the tribe there in 1824. This flat-topped mountain was 300 feet high, with a good spring on the summit and surrounded by 150 acres of pastureland and a deep valley. Only three narrow trails went up the slopes, and the people living there spread a rumor that at night the mountain grew so high that climbing it was impossible, until it returned to its regular size the next morning. In other words, it was a perfect place for a fortified settlement, and the one built there became Maseru, the capital of modern Lesotho. From here, Moshoeshoe beat off all attacks by others, and like Mzilikazi, he increased the strength of the tribe by accepting any Mfecane refugees that came in his direction. But unlike his rivals, he always tried to negotiate before he had to fight, and was so good at it that his kingdom, now called Basutoland, became an island of peace in the Mfecane storm. When the Boers and the British became new threats in the 1830s, Moshoeshoe also realized that he would have to modernize, so he began buying guns and horses for his men. Then in 1842 he "purchased" (invited) French missionaries from the Paris Evangelical Fraternity. The French were impressed; one wrote, "I felt at once that I had to do with a superior man, trained to think, to command others, and above all himself." In the same year Moshoeshoe requested a treaty of protection from the Cape Colony, but it was not granted at this time.

The lands north of Natal offered fewer opportunities than the lands to the west and south, but at least there weren't any Europeans blocking the way. One of the first to try the north was the Dlamini tribe, which in 1815 migrated to a small area between the Pongola River and Delegoa Bay (the site of Lourenço Marques, Portugal's southernmost settlement in Mozambique). Their king, Sobhuza I, adopted the military strategy of the Zulus, and defeated a Zulu invasion in 1836. He was succeeded by his son Mswazi (1839-68), who gave his name to the tribe (Swazi) and the kingdom (Swaziland).

Most of the migrations northward, however, involved Nguni clans whose leaders quarreled with Shaka, and thus saw no future for their people if they joined the Zulus. Soshangane took one group, the Gaza, and settled them in central Mozambique. An even larger group, led by Zwangendaba and Nxaba, also entered Mozambique, was defeated by the Gaza, turned west and destroyed the Urozwi kingdom, the current rulers of Zimbabwe (1834). Then the two chiefs had a falling out; Nxaba stayed near the Zambezi River, where he was killed in another battle with the Gaza a year later, while Zwangendaba took his followers north again. When they reached Lake Nyasa, the Nguni split up and settled on both the east and west sides of the lake, after inflicting further defeats on the Shona and Maravi tribes, and recruiting survivors from the defeated tribes into their ranks. In the 1840s, individual impis raided Tanzania and the upper Congo basin, campaigning as far north as the southern shore of Lake Victoria (stopping just short of the equator) and as far east as the Indian Ocean. When Zwangendaba died in 1848, his Nguni nation split into five clans; three settled down in Zambia and Malawi, while the other two chose to stay in Tanzania.

The Great Trek

The 1830s also saw a migration of Africa's "white tribe," for reasons that had nothing to do with the Zulus. On August 1, 1834, the abolition of slavery went into effect throughout most of the British Empire; during a four-year "transition period," all slaves would have to be set free. London offered £1,250,000 in compensation to slave owners, but in order to claim the money, they either had to make the long trip to England, or hire an agent to do it. Thus, many Boers got no compensation for their slaves, and felt they had been robbed. Even more galling for them was the idea that they would now have to treat the black man as an equal.(15) As soon as they heard of the abolition, many decided that they would have to load their wagons and move to a place where the British wouldn't bother their way of life; in 1834 three advance parties of voortrekkers(16) left to explore the lands beyond the Orange River.

While they were away, the Sixth Kaffir War (1834-35) erupted between European settlers and Africans. The population of both groups along the frontier had swelled, raising tensions to the boiling point, and the Xhosa, suffering from another bad famine, were particularly mad at a law that permitted Boer commandos to follow footprints to Xhosa villages (kraals) and take cattle if they believed the cattle were stolen. This time 12,000 Xhosa burst into the Cape Colony, and while superior British firepower eventually drove them back, it was the most costly war yet; the Europeans lost 456 farms and both sides lost thousands of animals. On top of this, the foremost Xhosa chief had been captured, and shot while trying to escape; British soldiers cut off his ears for souvenirs, and tried to gouge out his teeth with bayonets. The Xhosa never forgave the British for this atrocity. The British commander, Colonel Harry Smith, announced the annexation of the land between the Great Fish and Great Kei Rivers, calling the territory Queen Adelaide Province, but the Xhosa simply refused to get out; eventually Cape Town's governor gave the land back.

For the Boers, winning a war and having nothing to show for it was too much. They knew what to do when their exploration parties returned. One group went to what is now Namibia, and found only deserts. The second had explored the High Veld and reported finding almost unlimited grazing land, but neglected to add that the Ndebele already lived there. The third group had the most glowing report of all; they had entered Natal and their leader declared that, "only heaven could be more beautiful." Thus, from 1836 to 1839, about 6,000 Boers and their servants crossed the Orange River and headed for the High Veld, in a migration now known as the Great Trek.