| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 12: A GENERATION OF REVOLUTION, PART I

1772 to 1815

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| It All Started in America | |

| The First French Revolution | |

| The Reign of Terror | |

| The Directory | |

| The End of Poland--For Now | |

| Enter Napoleon Bonaparte | |

| The United Irishmen's Revolt | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

Part II

| The First Consul Takes on the Second Coalition | |

| The First French Empire | |

| Napoleon at the Height of Power | |

| From Moscow to Elba | |

| The Hundred Days | |

| Population at the End of the Revolutionary Era | |

| The Industrial Revolution Begins |

It All Started in America

The eighteenth century is often called "the Enlightenment" or "the Age of Reason" because from the point of view of philosophers like Voltaire and Rousseau, mankind had been finally set free of the fear of God, and now without the shackles of the Church holding him down, he could go on to produce a perfect society, one free of war, tyranny, bigotry, and all the other evils they saw in the world around them. But it seems that mankind will always venerate something, and as religion faded from daily life, nationalism stepped in to take its place. Nations came to be seen as personalities, leading to the development of the modern political cartoon, with nations represented as animals (e.g., the American eagle, the British lion, the Russian bear or the Chinese dragon) or as individuals like John Bull, Uncle Sam, the goddess Britannia, etc. The politics of the seventeenth century may have been best symbolized by Louis XIV's apocryphal statement, "L'etat, c'est moi," but in the early eighteenth century Prussia's Frederick William I showed how much things had changed by saying, "I am the state's first servant." Now people saw international events as the actions of nations rather than the actions of kings. For example, in 1772 it was Prussia, Russia and Austria--not Frederick the Great, Catherine the Great, and Maria Theresa--who were seen as falling upon and dividing Poland. It was not King George but Britain who defeated the French in Canada and India, during the Seven Years War. At the same time people came to see a nation as the property of its people, not the property of the monarch. For example, France came to be defined as the land of the French people, rather than the land ruled by King Louis.

All this may seem trivial from our point of view, but take note of this: if the people see a king's authority as coming from themselves, rather than from God, it is a small step to consider running a nation with no king at all! With a cynical eye common citizens looked at the way kings went along wheeling and dealing, acting treacherously when they could get away with it, caring little for the welfare of their subjects, and trading pieces of land (with the inhabitants on them) as if they were baseball cards. What the kings did not realize was that a generation was growing up that would refuse to play this game. They first showed themselves among a group of people who had already left the homes of their ancestors to make a clean break with the past--the settlers of the British colonies in America. A wave of monarchist refugees fled across the Atlantic when the victors in the English Civil War executed Charles I; they were joined not long after that by Cromwell's supporters when the monarchists returned to power; consequently the Americans had some vivid revolutionary memories to go on. And if that wasn't enough, one could also look to the republics of Switzerland and the Netherlands to see what ordinary people can achieve when freed of the shackles imposed by kings.

During the Seven Years War the cost of driving the French and Spaniards from the Atlantic seaboard of North America was met by the British taxpayer. The American colonists did not contribute a penny beyond what normally went to their militias. After the war the home government, coming under the usual pressure to reduce spending, decided that the time had come for the Americans to pay for their own defense. The money was to be raised from stamps that the colonists would be required to put on all legal documents, a form of taxation that already existed in England. The colonists decided that they were having none of this. They argued that Parliament did not have the right to tax those subjects who have no voting representatives in the House of Commons, which would have been impractical anyway, given the amount of time it took to communicate across the Atlantic. Vigorous demonstrations followed. The British government, recognizing that it was not worth risking a civil war to force the issue, took only a few months to change its mind and drop the idea (1765).

The truth was that the thirteen colonies between Canada and Florida had grown up. While the British flattered themselves by thinking that their red-coated soldiers had saved the colonists from the threat of destruction by Indian, Spaniard, or Frenchman, the truth was that steady multiplication had raised the American population to a level where only the mother country's government could be a threat.

For a few years after the Stamp Act the situation was reasonably calm; most colonists were satisfied with the autonomy created by their distance from the mother country; Britain was aware that it could lose a captive market if it insisted on more than token legislation to prove it was still sovereign. One of these token acts was the granting of a tea monopoly to the British East India Company. The radicals of New England considered even this a form of tyranny and organized a tea boycott. It was an immediate success; in Boston the authorities lost power completely and the colonists dumped a consignment of tea into the harbor (1773). This episode, the "Boston Tea Party," clearly showed that in New England a majority of the colonists now considered themselves Americans first and Englishmen second. Skirmishes between the British army and local militia in and around Boston grew into a full-scale war in early 1775. One year later, realizing that they had gone past the point of no return, the colonial leaders wrote the Declaration of Independence.

The war that followed was small in casualties and destruction, but awesome in its effects on future history. The American navy was limited to a few privateers like John Paul Jones, meaning that they could not stop the British from landing wherever they wished. On the other hand, the British did not have an army large enough to conquer and subjugate the whole continent. The result was a few British garrisons occupying key points like New York City and making occasional forays into the interior. The battles this caused were not expensive enough to make London seek a negotiated solution. Not until 1779 did the Redcoats come up with a consistent strategy--once an area was conquered, recruit loyalists from the local population to manage and defend it, then move on. This worked in Georgia and South Carolina, which had a larger percentage of loyalists than the north. Then in 1781 the French fleet blockaded Chesapeake Bay, allowing the American forces to trap and force the surrender of a British army at Yorktown. More than anything else, this caused the British to realize the futility of the conflict. Fighting ceased on the mainland and in 1783 a formal peace treaty was signed in Paris between France, Britain and the American republic.

The British did more poorly than one might expect, because this was the only time their "balance of power" strategy worked against them. They had done too well when they won the Seven Years War; by conquering Canada and gaining a controlling interest in India, Great Britain--and not Spain, France or anybody else--had become the richest, strongest nation in Europe. Because of that, and because King Louis XVI (1774-93) was not as threatening as previous French kings, the American Revolution saw the British fighting alone. The British were not the only ones who could play the "balance of power" game, so everyone in Europe with a grudge against the British entered the war on the American side. Three other nations (Russia, Denmark and Sweden) stayed out of the war by forming a "League of Armed Neutrality," to protect their shipping; though the British still had more ships than the League, they chose not to provoke them.

Chief among the American allies and Great Britain's opponents were, of course, the French. Animated by their total humiliation in the last war, and no longer distracted by anything back in Europe, the French mounted a more vigorous naval offensive than anyone expected. Least of all the British, who after the Seven Years War had foolishly reduced the size of their navy until it was only slightly larger than the French navy. The British failed to strike the decisive blow that they needed in their first clash with the French (the naval battle of Ushant, 1778); thereafter London fought defensively and split the fleet into squadrons to protect the British Empire in India, North America, and the Caribbean. When the French persuaded Spain (1779) and the Netherlands (1780) to join them, the British found themselves overstretched. Now they would have to lose on one front in order to free up enough men and ships to win on the other fronts; consequently the battle of Yorktown was a turning point as well as a great defeat. Once the British realized that they could not reconquer the rebellious North American colonies, they concentrated their North American forces against the French in the Caribbean. Here they showed that in a one-on-one sea battle, the British were still the best sailors; a victory in 1782 jeopardized the few gains Spain and France had made. When the war ended, the French got one Caribbean island (Tobago) and were returned one of their West African slaving posts (St. Louis)--small rewards for all their efforts. Spain got back Florida, while the Dutch got nothing at all. All things considered, the British felt they had weathered the crisis remarkably well.

The Americans won their freedom without compromising any of their principles. Even in the darkest days of the struggle they had refused to pay taxes to anyone. Paper money, devalued until it was nearly worthless, paid for the armies of the revolution.

The First French Revolution

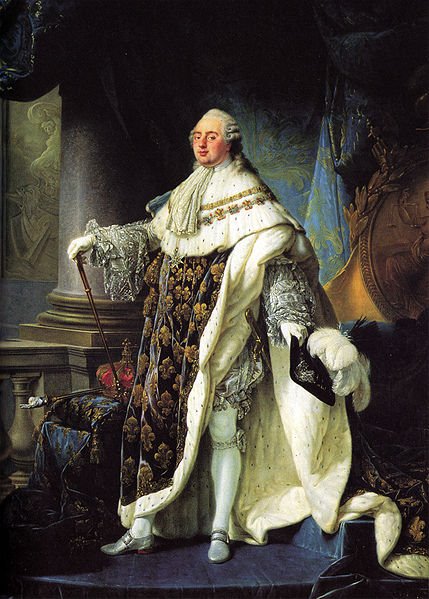

The American Revolution was a money-losing deal for France, and after it ended France slid into bankruptcy. King Louis XVI was a dull, ill-educated monarch who was more interested in eating than in managing affairs of state. To give one example of his lack of interest in his responsibilities, Louis only left Paris twice in his life. The first time was a trip to Cherbourg, on the coast of Normandy, in 1786, to inspect a massive harbor under construction, for both commercial traffic and defense of the English Channel. (The second out-of-town trip was the king's 1791 escape attempt, see below.) When the time came to make important decisions, the king had a knack for choosing the wrong course of action. In addition, he had the misfortune to be married to a silly and extravagant Austrian-born princess, Marie Antoinette. While the ministers tried to balance the budget, she encouraged the government to spend more, to re-enact the pomp and glory of the previous century, and restore all the powers and privileges the nobility and clergy enjoyed under Louis XIV. For example, commoners who had become officers were weeded out of the army and replaced by aristocrats.

It now appears that an overseas natural disaster tipped the French economy past the point of no return. A volcano in Iceland, Laki (also called Lakagígar), underwent a devastating eruption in 1783. Poisonous gasses from the eruption killed most of Iceland's sheep, and at least half the cattle and horses. It is estimated that between 20 and 25 percent of Iceland's human population was killed as well, and this happened while Iceland was trying to recover from a physical and economic slump that had lasted since the fourteenth century (see Chapter 9). And then the clouds of ash and sulfur dioxide blew across the North Atlantic to Europe. You may remember that when another Icelandic volcano, Eyjafjallajökull, erupted in 2010, a jet stream carried the clouds to Europe and disrupted air traffic for several days. Well, Laki's clouds blew over, too, but since the Laki eruption was bigger, the effects were worse. Europeans were poisoned, and the clouds blocked enough light to lower temperatures worldwide and cause many crop failures. Some areas also experienced severe hail and flooding. We believe six million people around the world died as a result, mostly from famine. In France during the mid-to-late 1780s, bread became scarce at marketplaces, and then disappeared completely. For the typical French peasant, not being able to buy baguettes every day -- and the outrageous prices when they were available -- were the first signs that trouble was on the way.

Meanwhile in the government, Marie Antoinette's finance minister, Charles-Alexandre de Calonne, did a wonderful job of raising money as if by magic--borrowing money from new banks to pay down old loans--and it magically disappeared just as quickly. Then in 1787 he ran out of tricks. He had piled loan upon loan, borrowed money at a 20% interest rate(1), and ran up the deficit until it reached the point that the interest on the national debt equaled half the state's total revenue. Normally the crown would have just raised taxes on the people, eighty percent of whom were peasants at this time. However, church tithes and obligations to their feudal lords had kept them poor, and the high price of food during the famine meant they had no money to give. Calonne declared the Grand Monarchy bankrupt; he could not raise money, pay down or restructure the debt. The only solution was a gathering of nobles to work on the problem.

Louis XVI.

When the French elite got together, Calonne proposed a tax on their property. This enraged the nobility--they never had to pay their share of the country's taxes before--and they immediately opposed the idea. The king dismissed Calonne, but his successor also suggested a property tax and likewise got nowhere. Then the nobles and king agreed to convene the Estates General, the closest thing to a Parliament or Congress that existed in France. This was a momentous decision and everyone knew it; the Estates General had not met since 1614. Inquiries were sent to the royal archives to find out how the meetings were conducted last time. Nor was there a formal meeting place; for lack of a better spot it convened in little-used parts of Versailles like orangeries and tennis courts, so it wouldn't get in the way of the royal family's social life. Nobody had any idea what would come out of such a convention, but after seeing what representative government had done to England and America, expectations were high.

It took until May 1789 to choose the delegates. The Estates General met in three bodies, representing the nobility, clergy, and middle class, symbolizing the three main social classes in French society. Since the middle class, or "Third Estate," represented the largest number of people, the king allowed them to have the most members. The total membership in each estate was as follows:

Clergy = 308

Nobility = 285

Middle Class = 621

Unfortunately the arrangement fell apart over the question of how voting would take place. The Third Estate held forth for a "one man, one vote" principle, which would have given it a slight majority over the other two. The upper classes, on the other hand, felt that each body should have only one vote, giving the nobility and clergy the power to veto any Third Estate action by a 2 to 1 majority. For six weeks the convention was deadlocked over this issue, until the Third Estate changed its name to the National Assembly and declared that it alone represented the nation; henceforth no taxation could take place without its consent. The king didn't like this turn of events and closed the hall where the National Assembly was meeting, a strong hint that it was time to go home. Instead the delegates (which included a few sympathetic members of the other two estates) got together in a covered tennis court and took the famous Tennis Court Oath, promising not to dissolve until they had passed a constitution for France. Three days later the king appeared, demanding that the members of each estate meet separately; in other words, he preferred the old arrangement of the Estates General. After he left, a royal official came to disperse the Assembly and got this reply from its spokesman, the Comte de Mirabeau: "We are here by the will of the people and . . . we shall not stir from our seats unless by force, at the point of a bayonet."

The king attempted to use force, only to find that many of his soldiers refused to act; their sympathies were with the Assembly. He gave in suddenly and allowed the Assembly to begin its program for France, while secretly gathering troops from the provinces and from foreign regiments in the French service. Word got out that the king was about to go back on his word, and Paris revolted. Acting with sudden unity, the Parisians set up a provisional city government and organized a military force of their own, the National Guard.(2)

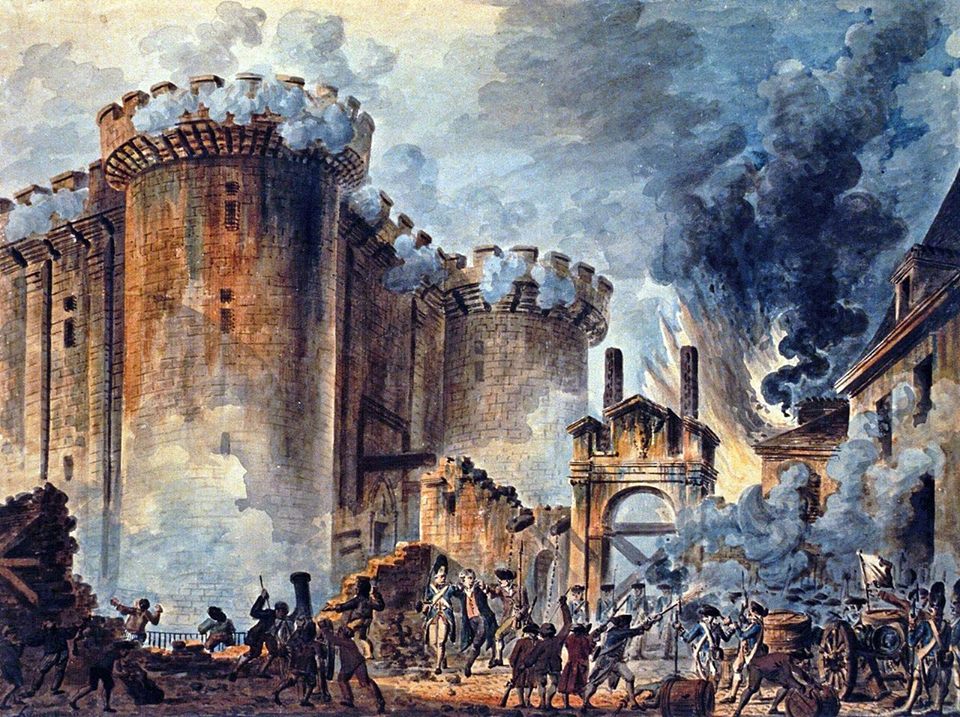

In Paris stood the Bastille, a grim fortress-turned-prison and hated symbol of the old regime, so it became the first target. On July 14, 1789, the mob of Paris stormed the Bastille and slew its defenders. There were only seven prisoners in it on that fateful day -- four counterfeiters, a drunkard and two lunatics. The Marquis de Sade, the famous sexual deviant, had also been imprisoned there recently, but was tranferred to an insane asylum ten days earlier, because he tried to get the mob to rescue him by shouting through his window: "They are massacring the prisoners; you must come and free them." Nevertheless, the Bastille's capture and destruction was ingrained so powerfully in the memory of France that the anniversary of the storming soon became a national holiday, marking the real beginning of the French Revolution. From there the insurrection spread rapidly to the rest of France. Many chateaux belonging to the nobility were burned by the peasants, who also carefully destroyed the title-deeds to the land, and the original owners were killed or driven away. The next few months saw the collapse of the Ancien Regime, as many leading aristocrats fled abroad and the National Assembly stepped in to begin a new age for France.

The storming of the Bastille.

A lot got done during the next two years; the Assembly passed more than two thousand laws, making it the most productive legislative body to ever convene. During this time the French government acted a lot like its British counterpart, a limited monarchy. Aristocratic and clerical privileges were abolished, and the government was reorganized top to bottom, while confiscations of church-owned land gave the treasury a shot in the arm. The old provinces were completely swept away, to replaced by eighty-three territories about the same size known as "departments," each run by an elected council and defended by a unit of the National Guard.(3) A constitution was drawn up, with its main feature being a Bill of Rights known as the "Rights of Man"; appropriately, the author of the American Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson, was the United States ambassador to France at the time, and the Assembly frequently called upon him for advice.

At this point the king frequently seemed to embrace the cause of the revolution, and attracted wild support for doing so, but afterwards he always found a way to dispel the good will he had generated. In this way he showed he was just as ignorant of politics as he was of money; for the day that the Bastille was taken, all he put in his diary was "Rien" (nothing). More and more he came to be equated with France's foreign enemies, an impression reinforced by unwise communications with those who had emigrated and the constant reminder of his foreign-born queen.

There were other problems that helped to insure that the French Revolution would not be the complete success that the American Revolution had been. First of all, the United States had much of the western hemisphere to itself, where only the British actively tried to interfere. Because most of North America was still not settled, the Americans were blessed with a seemingly endless supply of undeveloped resources to pay off the national debt with. The institutions of American society were relatively weak, and generally friendly to what the founding fathers were doing. The French, on the other hand, were surrounded by aggressive neighbors with Machiavellian ideas, and it always seemed that king, court and church were out to make mischief upon the new regime. Most important of all was the background of the main participants. Nearly all of the American Revolution's founding fathers had been born and raised as Christians, and though many of them no longer believed in the teachings of traditional Christianity(4), it was still a powerful moral influence on them all. In France, however, the writer-philosopher who was all the rage at the time was Jean Jacques Rousseau, who saw any social organization as a form of oppression. To Rousseau man has the potential to be perfect, a "noble savage," but everywhere society puts chains on him. In response he declared that delinquency on debts, sexual misconduct, and the rejection of institutions like the church and schools were nothing more than displays of "natural virtue." His advocacy of personal rebellion became immensely popular among those inclined to ideas like "if it feels good do it," and by the 1790s an entire generation had grown up reading his works, making them respectable. What this meant was that the French lacked the moral backbone to tell them when to stop.

In Mirabeau the National Assembly had a real statesman, and his death in 1791 went a long way toward negating attempts to reach a compromise between royalists and republicans. Then the royal family did something that confirmed the worst suspicions of those who wanted to abolish the monarchy--they ran away. One June night after 11:00 P.M. the king, queen and their two children disguised themselves, slipped out of the Tuileries palace of Paris, walked north to the outskirts of the city, and circled to the east side of town, where a traveling carriage was waiting for them. The royal family was fleeing to Belgium (then called the Austrian Netherlands), where Marie Antoinette's countrymen were likely to give them shelter. They might have made it, but at an inn Louis followed his old habits; he took three hours for lunch, and the innkeeper recognized him when he paid the bill with a gold coin (the coin had his picture on it, of course). They were nabbed by republican troops just a few miles down the road, at Varennes. Their return was watched by a silent, hostile crowd lining the streets of Paris. The events that followed had much in common with the events leading up to the execution of Charles I in England; both kings were seen as dangerous men who loved the crown and did not care about the people, so they could not be trusted. After that Louis XVI was little more than a prisoner in the Tuileries, and in October 1791 new elections created a more radical National Assembly, one whose leaders would have been dismissed as impossible extremists in less troubled times.

Chief among the parties of the new Assembly were the Girondins, so called because they came from Gironde (the department around the city of Bordeaux), and the Jacobins, who got their name from their original meeting place, a former Jacobite monastery. The Girondins led the way when it came to abolishing the monarchy, but the Jacobins grew fastest, and turned out to be more important in the long run. The three most important Jacobins were Jean-Paul Marat, Georges-Jacques Danton, and Maximilien Robespierre. Their strength came from the fact that unlike the royalists and moderates, they were poor men, unencumbered by tradition and feeling that they have nothing to lose. Robespierre was a former lawyer and judge from Arras, who dressed impeccably and gained a reputation for being incorruptible and nearly emotionless; that and his faith in Rousseau made him the brains behind the second French Revolution. Danton was a scarcely more wealthy barrister from Paris, a big sensual man who loved women and good food, and was unmatched when it came to making bold speeches. The Swiss-born Marat was a fiery writer, and had been a successful doctor and scientist before 1789, but was equally unembarrassed by possessions. France would need all of their talents before long.

The Reign of Terror

No foreign government liked what was happening in France. The Austrian emperor, Leopold II, was greatly concerned for his sister, Marie Antoinette; he and Prussia's Frederick William II, egged on by refugee French aristocrats, called for a full restoration of the French monarchy. Other heads of state, whether they liked Louis XVI or not, felt that only monarchs had the right to remove other monarchs. But it was France that threw the first punch. Believing that a foreign war was just the thing they needed to unite France behind the revolution, the Girondins got themselves established as ministers in the government, and persuaded the king to issue a formal declaration of war (March-April 1792). It was a disaster at first. The French army, demoralized because two thirds of its officers were in exile, marched into the Austrian Netherlands, panicked when it saw the enemy, and scurried homeward. An Austro-Prussian army marched on Paris, and the French seemed so disorganized that nobody expected them to offer significant opposition. But at Valmy, less than 100 miles from Paris, the French got the miracle they needed. There on September 20, 1792, they managed to make a stand, and a short exchange of cannon-fire inflicted a few hundred casualties. The Austrians and Prussians realized that they were risking a major battle if they continued; this was not what they wanted so they pulled back. It was the turning point for the Revolution. The German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who watched the fighting from the Austrian camp, told this to his companions: "From this day and this place dates a new era in the history of the world. Some day you will be able to say, 'I was there.'"

At home the food shortages and inflation brought on by the war nearly wrecked the economy. Fear of the advancing invaders led to paranoia, and paranoia led to terrorism. Traitors and "enemies of the people" came to be seen everywhere. A heavily armed crowd of 20,000 broke into the Tuileries and slaughtered the king's 500-man Swiss guard, and illegal mass roundups of suspects filled the prisons. Other revolutionaries, not satisfied to see their enemies behind bars, broke in and massacred more than 1,000 prisoners during the summer of 1792. In the Vendée department (near Nantes) an outright rebellion by peasants and royalists broke out.

War abroad and anarchy at home caused the Assembly to dissolve itself. It was in session while the king's palace was attacked, but most of the conservative and many moderate deputies chose to stay away, fearful of the mob. That gave the radicals the majority they needed to vote for an end to the Assembly's deliberations. In its place they called for a new election, one which produced a Jacobin-dominated body called the National Convention. On the same day as the battle of Valmy, the National Convention held its first meeting. Two days later the monarchy was abolished, and Danton became the dictator of France.

This marked the beginning of a more complete reorganization of French society. The old money system was swept away, and the decimal metric system was invented, doing away with the confusing system of weights and measures that the Ancien Regime had used. Everything that smacked of royalty or privilege was discarded. For example, knee breeches, the short pants worn by 18th-century aristocrats, were declared unpatriotic, and replaced by long trousers called sans-culottes, which "made all legs equal by concealment." Wigs and powdered hair went out of fashion; mustaches came into style as a symbol of patriotism as well as virility. Jewelry became unpatriotic, save for brooches representing symbols of the revolution like the Bastille or the head of Marat. Titles of nobility disappeared, to be replaced by the terms "citizen" and "citizeness." New decks of playing cards showed symbols of virtues like liberty, equality, and so on, instead of kings, queens, jacks and jokers. Popular souvenirs were paperweights made from stones of the Bastille, and miniature toy guillotines for children. Men changed their names, especially if their pre-1792 name was Louis. Even the name of the queen bee was changed to "laying bee."

The old calendar was also scrapped. September 22, 1792, the date of the monarchy's abolition, became the first day of Year 1 of Liberty. The calendar of the Revolution still had twelve months, but it replaced the old weeks with "decades" of ten days each, with three decades per month. The months themselves were given poetic names recalling the prevailing weather or events in the agricultural cycle. For instance, late July-early August became the month of Thermidor, because it is the hottest time of the year, and August-September was called Fructidor, meaning the month of fruits. They even attempted to make time measurements decimal; they divided each day into 10 hours, each hour into 100 minutes, and each minute into 100 seconds.

There still remained the problem of what to do with the deposed Louis XVI, now called Citizen Capet, after his tenth-century ancestor Hugh Capet. Once again the activities of himself and Marie Antoinette decided the matter. In November a secret iron closet containing their correspondence with foreign monarchs and French aristocrats in exile was discovered in a wall of the Tuileries. The letters themselves were mostly harmless, but the fact that they were addressed to known enemies of the Revolution, and hidden as well, gave the radicals cause to accuse Citizen Capet of treason. The ex-king was put on trial and by almost unanimous vote, found guilty. The Girondins wanted to delay the next logical step until after the war, so that it wouldn't provoke the enemies of France, but the Jacobins overruled them and sentenced the king to immediate execution. On January 21, 1793, Louis was taken to the guillotine, a new beheading machine introduced five months earlier as a merciful and scientific alternative to the tortures that criminals were still frequently punished with. The grim blade did its work, and Danton explained in his leonine way that this was done to show that the Revolution would defend itself: "The kings of Europe would challenge us. We throw them the head of a king!"

The Terror had come to save the Revolution.

To meet the challenge from inside and from without, the government of the National Convention gave unlimited power to its security apparatus, the Committee of Public Safety, in early 1793. Under the committee were two subsidiary bodies, the Committee of General Security and the Revolutionary Tribunal. The task of the former was to ferret out traitors, while the latter judged and executed them at the hands of "Madame Guillotine." Soon the Committee of Public Safety became the most powerful branch of the government; the driving force behind its ruthless war against the enemies of the Revolution, Robespierre, became the real ruler of France.

In some ways Robespierre is a difficult man to judge. Timid and fastidious in his early years, he gave up being a judge because he was too squeamish to issue death sentences (He got over that quickly!). But he was more honest than just about any other ruler in French history, and he had absolute faith in the rightness of everything he did; those assets carried him over all hurdles. He dedicated himself to saving the Republic, acting as if nobody else could do the job. His dream was a "republic of virtue," a utopia in which every vice of man would be purged; to him the guillotine seemed like the quickest tool for purging. As another Jacobin put it: "What constitutes the Republic is the complete destruction of everything that is opposed to it."

When not working overtime to crush subversion, revolutionaries experimented with creating a proper republican religion. The movement started with simple anti-Christian prejudice. Churches were closed and images destroyed; clerics earned the label "enemies of the people" if they did not take their pay and direction from Paris (instead of Rome). In November 1793 revolutionaries wearing floppy red liberty caps marched into Notre Dame Cathedral and converted it into a temple of reason, enthroning a pretty actress there to represent the goddess of reason. For Robespierre this was going too far. He was a Deist, not an atheist; he felt that atheism was a pitiful mental exercise invented by aristocrats to justify their sins. Instead he felt that an impersonal force, which he called the Supreme Being, guided the consciences of men in the direction of virtue. In June 1794 he celebrated this new creed with a festival to the Supreme Being; at the high point he ignited a paper-mache monument built to represent evil, and out of its ashes sprang a scantily clad actress representing wisdom, who invited everyone to pay homage to the "Author of Nature."

After Valmy the war news coming back to Paris was good, so at some point Robespierre should have called off the Terror and eased up the pressure he was putting on the country. Instead, the slaughter got worse every month. Suspected royalists were rounded up, given quick trials, and thrown into carts called tumbrels to be taken to the guillotine in the town square. From May 1793 to June 1794 there were 1,220 executions in Paris; the following seven weeks saw 1,376, an average of twenty-eight each day.(5) Other waves of executions took place in the countryside, where most of the victims were rebel peasants. In a few cases, rural tribunes resorted to drowning their victims or mowing them down with cannon fire, when it would take too long to guillotine them all. All in all, the Terror claimed nearly 40,000 lives. The reign of Robespierre seemed to live on blood, and needed more of it all the time, the way a drug addict needs more and more dope. Most frightening, the attitude behind the Terror could be catching. One story tells of a gentleman escorting two ladies to a theater in the town of Arras, next to where a guillotine was in action; he noticed a trickle of blood at his feet, dipped a finger in it, held it up and exclaimed, "How beautiful this is!"

The first and most obvious targets were those aristocrats who were unlucky enough to still be in the country, and generals who lost battles. Marie Antoinette was guillotined, and so was the mistress of Louis XV, Madame du Barry. Louis Philippe, the Duke of Orléans and the king's cousin, was a radical who changed his name to Philippe Égalité, and had provided the Jacobins with both money and a safe meeting place before they seized power; nevertheless, he was guillotined for being a member of the royal family, and for getting along too well with enemies of the regime. As the supply of royalist victims ran out, the Tribunal's definition of a counterrevolutionary grew vague and undiscriminating. For example, Antoine Lavoisier, the founder of modern chemistry, was guillotined because the income that paid for his research came from tax farming. Then in early 1794 the creators of the Terror found to their surprise that it could consume them as well. Antoine-Francois Momoro, a leader in the cult of reason and the fellow who coined the Revolution's chief slogan ("liberté, egalité et fraternité"), was accused of being an enemy of the Revolution and guillotined in March. Girondins were guillotined; atheists who did not believe in Robespierre's Supreme Being were guillotined; Danton was guillotined because he thought there was too much guillotine. When his turn came, Danton acted bravely to the end. "Show my head to the people," he told the executioner. "They don't see one like it every day."(6)

The Directory

On July 26--Thermidor 8, Year 2 on the revolutionary calendar--Robespierre overreached himself. Speaking to a guillotine-depleted National Convention, he announced yet another purge of its deputies, to eradicate the last enemies of the Republic. Aware that they were literally voting to save their necks, the Convention voted to arrest him the next day. A night of chaotic fighting followed in the streets of Paris, and those forces loyal to the Convention prevailed over those loyal to the Jacobins. Robespierre was shot in the jaw in one scuffle (possibly a suicide attempt), and seventeen hours later he and twenty-one followers were carted to the guillotine to which he had sent so many others, instead of the condemned appointed for that day. A few more executions of Jacobins took place during the next few days, and the Terror was finally ended.

The Jacobins were replaced by a council of five, known as the Directory. The Directors were colorless men, more interested in personal gain than in social experiments. Under the Directors was a bicameral legislature, elected by those citizens who owned property, so you can see the new government as a step back towards the old way of running things. To revolution-exhausted France, the Directory's rise to power was seen as a relief; all the Directors wanted to do was preserve the gains the Revolution had made. But they soon realized that revolutions cannot simply be turned off like a water faucet. In southern and western France a conservative "Catholic and Royal Army," composed mostly of peasants armed with weapons made from farm tools, launched a "white terror"; they used the new era as an excuse for disorganized brutality against Jacobins and other supporters of the Revolution. This rebellion was crushed in 1796, but reactionary acts of violence continued for a while beyond that. In Paris itself gangs of royalists and Jacobins roamed around, looking for a chance to start a riot; food shortages and inflation threatened to swell their ranks with the desperately poor. In 1795 the Directory issued the third constitution for France in four years, and it was so unpopular that a royalist mob attempted to take over the National Assembly. Fortunately for the government, one of the Directors, Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras, entrusted the defending artillery to a young ex-Jacobin general named Napoleon Bonaparte. Using "a whiff of grapeshot," Bonaparte dispersed the mob with a volley that left 200 dead--ensuring a future for both the Directory and himself.(7)

On the war fronts the Austrians and Prussians realized belatedly that they had stirred up a hornet's nest. Victory at Valmy inspired the National Convention to call for a grand offensive that would give France the "natural frontiers" of the Rhine and Alps. The end of 1792 saw the French surging forward to the east; one army overran Belgium, another moved north from Alsace to clear the entire west bank of the Rhine, and a third conquered most of Savoy. This onslaught by forces that had been thought incapable of defense amazed and alarmed Europe. As the French were now eager to spread their gospel of revolution to every state around them, 1793 saw the formation of an anti-French coalition that included just about everyone. The British and Dutch joined the Austrians and Prussians on the lower Rhine. Austria and most of the Italian states sent support to the Savoyards still fighting in the Alps. Spain launched an attack over the eastern Pyrenees. Far away from the action, Russia announced that it would be willing to give aid if needed. In the course of the 1793 campaign the Coalition's armies forced the French back within their prewar frontiers but the allies were too eager to pick up the spoils of victory to finish the job. The French armies were rapidly rebuilt as Minister Carnot, "the organizer of war," introduced universal conscription, calling it the levée en masse; now just about any single man was eligible to serve. The result was that he gave the army men and munitions at a truly revolutionary rate, producing a force that numbered 770,000 men. As he sent nothing but men and guns, the French had to attack constantly to keep alive; their numbers, zeal and desperation more than made up for their lack of supplies as they threw themselves repeatedly against the small professional armies of the Coalition. In late 1794 a second surge began which once again bundled the allies back across the Rhine. This time neither the river nor winter stopped the French. A cavalry charge across the frozen Scheldt River captured the icebound Dutch fleet; the Netherlands surrendered and became a puppet state called the "Batavian Republic," allied to France and paying French taxes. Spain and Prussia left the war in the spring of 1795. Almost as discouraged, the Austrians agreed to a six-month truce on the Rhine; they kept the war going in Savoy, however.

The End of Poland--For Now

After the outrage of 1772, Poland underwent a remarkable transformation. The Polish nation acted as if it was born on the eve of its dismemberment. There was a hasty but very considerable development of education, literature, and art; historians, poets and magnificent musicians sprang up; the constitution which had made Poland impossible to govern was trashed. The free veto was abolished, the crown was made hereditary to stop the foreign intrigues that came with every election, and a British-style Parliament replaced the impotent Diet. There were, however, lovers of the old order who opposed these necessary changes, and the obstructionists were supported by Prussia and Russia, who naturally did not want to see a strong Poland on their doorstep.

Tragically the Poles did not learn how to play their enemies against each other. To stop the enemy they hated the most, the Russians, they would have needed the support of Prussia or Austria, preferably both. Instead they rejected the Prussians' price for such an alliance (the enclaves of Danzig and Thorn) and proclaimed a new constitution which amounted to an anti-Russian manifesto. The Russians and Prussians gave one another the nod, moved in and occupied the country (1793). Before they left they forced the Poles to cede half the land remaining to them. But as soon as the second partition was complete, the Poles began a fierce nationalist struggle in the Prussian-occupied area, and found a brave leader in Tadeusz Kosciusko, a veteran of the American Revolution. Kosciusko won the first battles, but the rebellion was put down anyway, and in 1795 Russia, Austria and Prussia agreed to a final division of the kingdom. Simply and without fuss, Poland was removed from the map of Europe.

At that point it must have seemed like another threat to monarchy had been eliminated. But the patriotism of the Poles grew stronger and louder, the longer they were suppressed. For more than 120 years Poland struggled like a submerged creature against the political and military net that had been made to hold her down. She would rise again after World War I.

Poland dismembered.

Enter Napoleon Bonaparte

After the Terror burnt itself out the armies of France remained as aggressive as ever. Ragged hosts of enthusiastic soldiers continued to sing their marching song, the Marseillaise, and never seemed to know for sure whether they were looting or liberating the lands they invaded. Even so, the plan that the Directory approved for the Italian front in 1796 was an extraordinarily ambitious one. In fact, it was so ambitious that the army commander took one look at his starving troops and sent it back, saying it was impossible. Let the man who dreamed it up carry it out. The Directors agreed and told Napoleon Bonaparte to take command of the optimistically named Army of Italy.

Bonaparte arrived in March to find his men creeping along the coast toward Genoa to keep themselves fed, and the Austrians beginning an attack on the leading French corps. He immediately thrust northwards, separating the Savoyards from their Italian allies, then turned upon the Savoyards and drove them back to Turin in disorder. At the end of April, Savoy surrendered to a French occupation force. Turning east, Bonaparte chased the Austrians out of Milan and by June had the remnants of their army locked up in Mantua. The minor Italian states quickly offered to buy peace from the conqueror; the terms he imposed brought tears to their eyes.

The armistice on the Rhine expired in June; Bonaparte was counting on Jean Victor Marie Moreau, the French commander on the Rhine front and conqueror of Holland, to keep the Austrians from sending reinforcements to Italy. However, Moreau moved slowly and when he did move, was defeated. Thus the exhausted Army of Italy found itself facing a fresh Austrian force, which after various excursions was also shut up in Mantua. At the end of the year Bonaparte turned back a second relieving force; in January 1797 he destroyed it at Rivoli, and in February he received the surrender of Mantua. Then he invaded Austria and was only seventy-five miles from Vienna when the despairing Austrians agreed to a truce.

Napoleon Bonaparte at Rivoli.

Except for Great Britain, every enemy of France had now been defeated. Of all the campaigns, Bonaparte's were undoubtedly the most spectacular. That his success had brought him power as well as glory became evident when he ignored the wishes of the Directory and dictated the peace treaty all by himself. Most of northern Italy now became a protectorate of France. To placate the Austrians he dismembered the Republic of Venice and gave two thirds of it (Venetia and Dalmatia) to Austria, while retaining Lombardy and the Ionian Isles for France. This showed that Bonaparte could be as aggressive in his politics as he was in his generalship. It was now Year 6 of the Revolutionary era; France possessed the sort of frontiers that her kings had always dreamed of, and gladly hailed the new Caesar.(8)

The United Irishmen's Revolt

If there was any group in the British Empire that justly felt discriminated against, it was the Irish. The six hundred years since the time of Henry II saw British rule grow overbearing, especially after the Reformation put Ireland and Britain in opposing churches. During the English Civil War, Ireland's Catholic majority sided with the Royalists; in response, Oliver Cromwell's troops inflicted a "Godly slaughter" when they arrived on the island in 1649. Afterwards, it seemed that London's main objective was to squeeze whatever it could get out of Ireland. Catholics were forced to pay tithes to support the Church of England, which they abhored. Irish commerce and industry were deliberately crushed by the English; the Irish could not export cattle or dairy products to England, and a 1699 law banned the export of Irish woolen goods anywhere. Most of the wealth was concentrated either in the hands of a few Irish Protestants (many of whom were really transplanted Scots), or went to absentee landlords in England. Because they faced government-mandated poverty if they stayed, many Irish emigrated--the Catholics to Spain and France, the Protestants to America.

Tensions rose in the late eighteenth century, as London withdrew many soldiers to fight the French and Americans overseas, leaving only second-rate troops to garrison the Emerald Isle. Before violence broke out, however, the Irish Parliament passed the Relief Act, removing some of the most oppressive disabilities (1778). Meanwhile the Irish Protestants, under the pretext of defending the country from a potential French invasion, formed volunteer militias, which grew to a combined membership of 80,000. Because the Crown had less than 10,000 regular infantry in all of Great Britain, the militias became a bigger threat than any foreign power could be, and they saw in the American Patriots an example to follow. Soon a movement arose that demanded the right for Ireland to make its own laws, led by a lawyer named Henry Grattan. At this point the British had their hands full with the American Revolution, so in 1782 they granted legislative powers to the Irish Parliament. However, most of the parliament's members were Protestants--Presbyterians to be exact--and while they had been subject to discrimination because they weren't part of the Church of England, they had little sympathy for the Catholic majority. Thus, the Catholics saw this concession as nothing more than a changing of their masters.

The success of the American and French Revolutions encouraged Irish nationalists to demand more, and during the next few years a more radical movement arose, the Society of United Irishmen. Again most of the members were Presbyterians; Catholic nationalism wouldn't appear until after 1800. The most important leader was Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763-98), who first tried to get what he wanted peacefully, until he was forced to flee. He took refuge in France, and the French were happy to promise soldiers to his cause, which would open up a second front against the hated British. In December 1796 Wolfe Tone returned with a fleet of thirty-six French warships, carrying 15,000 men. If this force had successfully linked up with the Irish militias, it would have been all over for the British, but nature intervened to prevent it. When the fleet dropped anchor in Bantry Bay, on the southwest coast, the flagship and the commander, General Louis Lazare Hoche, were not there--terrible weather had separated them from the rest of the flotilla on the way. Thus, everyone waited for Hoche instead of disembarking; later Wolfe Tone lamented that he was close enough to shore to throw a biscuit to it from his ship. Hoche never arrived, and on the second day a strong east wind arose, keeping the ships from sailing the final few yards to shore. Some of the ships went back to sea immediately; others stayed, waiting for the wind to change; instead it grew to gale force and blew the rest of the fleet away by the seventh day.

Meanwhile, the French launched two diversionary attacks on Great Britain itself, to keep the British from sending reinforcements to Ireland. One squadron went to the important port of Newcastle, but poor weather and mutinies forced it to return to France without making landfall. The other squadron originally headed for Bristol, and the same adverse winds drove it to south Wales. There it managed to land 1,400 men, who called themselves "the Black Legion," at the town of Fishguard (February 22, 1797). These were not France's finest; only 600 of them were regular French soldiers, while the rest were prisoners sent on a punishment assignment--deserters, common criminals and royalists of dubious loyalty. This motley crew was led by an Irish-American, Colonel William Tate, whose qualifications were that he was a veteran of the American Revolution and had taken part in an unsuccessful plot to capture New Orleans for the French.

Anyway, the plan was to march across Wales to Bristol, but discipline broke down immediately. The convicts deserted, got drunk when they found wine, and looted a local church. Consequently the Welsh cooperated with England, instead of joining the French in an anti-English uprising. There was also a report of French soldiers seeing Welsh women at a distance wearing red shawls and black hats, and mistaking the traditional costume for the uniforms of British soldiers. Morale was so bad among those French who were not sick and drunk that a cobbler, Jemima Nicholas, singlehandedly captured twelve French soldiers, though she was only armed with a pitchfork. There was a skirmish when the local British militia arrived at Fishguard, and realizing that they could not succeed with both the Welsh population and the British army opposing them, Tate and the French officers surrendered. That ended the expedition, only two days after it landed in Wales; today it is sometimes called "the last invasion of Britain."

After all these failures, the French promised they would try again; in the meantime, the United Irishmen made extremely well-organized plans to contain the British army in Dublin when the revolution began. Unfortunately for them, there were also government informers at their meetings. On March 11, 1798, the police swooped down on a house in Dublin and arrested most of the United Irishmen's leaders. Then the government declared martial law, and the soldiers used their searches for hidden arms as an excuse to inflict horrifying tortures on the general population. This convinced the masses that they had nothing to lose by revolting, so a desperate, unorganized uprising erupted on May 24.

The British found themselves not only outnumbered, but facing an opponent who attacked with reckless courage, no matter how high the losses. The British viceroy, Lord Camden, thought every Irishman was against him, and declared that "The organizing of this Treason is universal." Superior discipline allowed the British to win battles, but because they had removed the head of the movement, they faced the same challenge as the Vikings had in Ireland--there was nobody left to negotiate a peaceful settlement with. In the southeastern town of Wexford the rebels proclaimed a republic; it lasted until the British crushed its militia in a decisive battle, at Vinegar Hill on June 21. Now London replaced Lord Camden with someone experienced in dealing with rebellious colonies--Lord Cornwallis. Here Cornwallis did better than he had done against George Washington; in August he offered a general amnesty, and most of the fighting petered out.

That would have been the end of the matter if the French had not returned at that moment. On August 23, 1798, 1,099 French soldiers landed in an area that had previously escaped violence, Killala in the northwest. Wolfe Tone was with them again, and 5,000 more French were expected to come later. They had arrived too late to help the revolution, but 7,000 Irish rallied to join them anyway. Together they occupied most of County Mayo and marched inland, only to fail in their first encounter with the British. The Irish were defeated at the battle of Granard; at nearby Ballinamuck, 850 French fought 5,000 British for half an hour before surrendering. The French ended up imprisoned in Dublin, while the Irish were hanged or deported to Australia (Wolfe Tone committed suicide before the British could execute him).

The British prime minister, William Pitt the Younger, thought that the legislative union of Great Britain and Ireland, combined with Roman Catholic emancipation, was the only remedy for Ireland's problems. By a lavish use of money and distribution of patronage, he induced the Irish Parliament to pass the Act of Union, and on January 1, 1801, the union was formally proclaimed. He couldn't keep his promise of emancipation for Roman Catholics, though, due to the opposition of King George III. Now Britain could turn its attention back to Napoleon Bonaparte.

This is the end of Part I. Click here to go to Part II.

FOOTNOTES

1. The British government, by contrast, was so credit-worthy that it paid only 4% interest on its loans at this time.

You may have heard that when told the peasants had no bread, Marie Antoinette said "Let them eat cake," and went back to whatever she was doing; this is seen as evidence that the queen didn't care about her subjects. Actually she didn't say it; according to Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Confessions, an unnamed princess said this in the town of Grenoble, and it happened in 1740, fifteen years before Marie Antoinette was born.

2. The National Guard was put together and led by the Marquis de Lafayette, George Washington's French advisor during the American Revolution.

3. The provinces have been gone for more than two centuries, but the old geography is still vivid to a modern Frenchman. Ask him what part of France he is from and he may answer that he is a native of Normandy, for example, rather than mention which of Normandy's five departments he lives in.

4. Many American leaders at this time embraced Deism, which declared God to be an impersonal force that is no longer active in the universe. The model for their theory was the watch, which was created and wound up in the beginning, but has been running down without outside interference ever since.

5. Part of the reason for the number of deaths near the end was because in June Robespierre had a law passed forcing the Revolutionary Tribunals to choose between two sentences for everyone they tried under the nearly nonexistent system of justice: death or acquittal. Among those tried by the Committee of Public Safety, only one out of five was acquitted.

6. Marat probably would have also fallen victim around this time, had he lived. Instead, he was knifed in a bathtub the year before by a Girondin supporter. The scene of Marat's body leaning over the edge of the tub inspired a famous painting and the most celebrated tableau in Madame Tussaud's Waxworks; he instantly became the official martyr of the revolution.

One hero of the Revolution who should have been safe from the Terror was Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, the French army's first mulatto general and the father of another Alexandre Dumas, the famous author. In the spring of 1794 he defeated Austrian and Savoyard forces at Mont Cenis, a mountain pass high in the Alps, and this allowed the French to invade Italy in the campaigns that followed. Nevertheless, Dumas received a letter in June, that ordered him to come home and appear before the Committee of Public Safety. We don't know what he had been charged with, but it is likely that someone accused him of treason. Dumas bought time for himself by sending a reply stating that he was too busy now, and could not go to Paris before July. Then when July came, he went to Paris--very slowly. Maybe he expected the Terror would end before he got there, because that is exactly what happened. Thus, the general lived to fight another day.

Even famous foreigners who supported the Revolution were not safe; two who narrowly escaped the guillotine were Francisco de Miranda and Thomas Paine. The close call of Miranda, Venezuela's first revolutionary, is covered in Chapter 3 of my Latin American history. Paine had singlehandedly persuaded the settlers of Britain's North American colonies to declare independence, and because the American Revolution turned out so well, he went to France and tried his luck there, too. Instead, the Jacobins arrested him because he was an ally of the Girondins and he opposed the death penalty. Whereas Miranda saved his neck by successfully defending himself in court, Paine got off with dumb luck. On the hot summer night before his execution, he insisted on sleeping with his cell door open, after promising to the guard he would not try to escape. Later an official came by to mark the doors of those prisoners that would go to the guillotine the next day, and because Paine's door was open, he left his chalk mark on the inside of Paine's door. When the guards came in the morning, Paine's door was closed, so they didn't see the mark, and left Paine there while they took the other condemned away. A few days later Robespierre was overthrown, and Paine was off the hook.

7. Bonaparte showed so much promise in military school that he rose rapidly through the ranks. That, and the purging of all officers from aristocratic families, allowed him to become a general in 1793, at the tender age of twenty-four. In the same year he led an artillery attack that took back Toulon, after royalists had handed it over to the British navy. After the Thermidor reaction the Corsican was imprisoned and in danger of the guillotine for a time; fortunately for him, there wasn't enough evidence to convict him of anything.

However you feel about Napoleon Bonaparte, you have to admit that he has cast one of the largest shadows of anyone in European history; the legends promoted by his admirers, and the negative propaganda generated by his enemies, have made it difficult to separate the truth from the myths. I'll dismiss one myth right now, that he was one of the most famous short people that ever lived. Pop culture has exaggerated this to extremes; e.g., I remember one silly TV show had a midget playing Napoleon's part. The myth of the "Little Corporal" came about because even before the metric system was introduced, France and Britain had different systems of measures. According to the old French system, Napoleon stood five feet, two inches tall. When the British heard this, they reasoned that his attitude, the famous "Napoleonic complex," was an inferiority complex, overcompensation for below-average height. However, they forgot that a French inch was longer than an English inch, and when you account for that, Napoleon's height in the English system is a fraction of an inch below 5" 7'. Therefore his height was really a bit above average for those days; it isn't obvious because he doesn't look tall in the pictures of him standing with his Imperial Guards, who like the Potsdam Grenadier Guards, were chosen for their above-average height.

8. Trans-Alpine Savoy and Nice became part of France, leaving only Piedmont and Sardinia to the Savoyards. Lombardy was united with Modena and Romagna, the northernmost province of the Papal State, to form a puppet state called the "Cisalpine Republic." Genoa became the equally dependent "Ligurian Republic." The Swiss had lost Basel to France in 1793 and now their Italian-speaking Valtelline canton was detached and given to the Cisalpine Republic. When Bonaparte conquered the rest of Switzerland in 1798, he renamed it the "Helvetian Republic," detached the canton of Valais, and made it into another dependent republic.

Batavian, Cisalpine, Ligurian and Helvetian are geographical names that the ancient Romans had used; the neo-classical movement in art and literature peaked in the 1790s and Europeans couldn't get enough of anything that was Greco-Roman. In 1798 Tuscany would be renamed Etruria for the same reason. Similarly, the main result of Bonaparte's Egyptian campaign was to create a fad for Egyptian stuff at home.

Finally, another echo from classical times can be seen in the career of Bonaparte. He had become France's chief general through the patronage of a Director, just as Julius Caesar had used Crassus (see Chapter 3) to pay for his elections. But a few years later, when Bonaparte decided to become a dictator like Caesar, the vicomte de Barras, like Crassus, found that he could not control his client.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Europe

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|