| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 11: THE GAME OF PRINCES AND POLITICS, PART I

1618 to 1772

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| The War of the Spanish Succession | |

| Statistics on Population and Religion for the Early Eighteenth Century | |

| Scientific, Literary and Military Revolutions | |

| Seventeenth-Century Economics | |

| The Wars of the Quadruple Alliance and the Polish Succession | |

| The War of the Austrian Succession | |

| The Seven Years War | |

| The First Partition of Poland |

The Thirty Years War: An Overview

The most devastating conflict in European history before the twentieth century was the Thirty Years War. It started over matters of religion, and continued long after most people had forgotten the cause. Indeed, during the last thirteen years of the war (the French phase), it was really a struggle involving Spain and Austria on one side, and France and Sweden on the other, fought mostly on German soil. Nor was the fighting restricted to a line of battle--the participating armies were too small to hold a line--so they wandered all over Germany, causing destruction wherever they went. A horde of civilian camp followers traveled behind each army, looking to sell goods & services to the soldiers or to snatch something that the soldiers left behind in their looting, like remoras riding a shark in search of leftovers. Starvation and disease (from unburied bodies) claimed even more lives than the swarms of soldiers. Dead people were found with grass stuffed in their mouths, and there were reports of cannibalism. By the time the war ended Germany's population had dropped from about 21 million to 13.5 million; the survivors lived in a country so wasted that it took two centuries to recover.

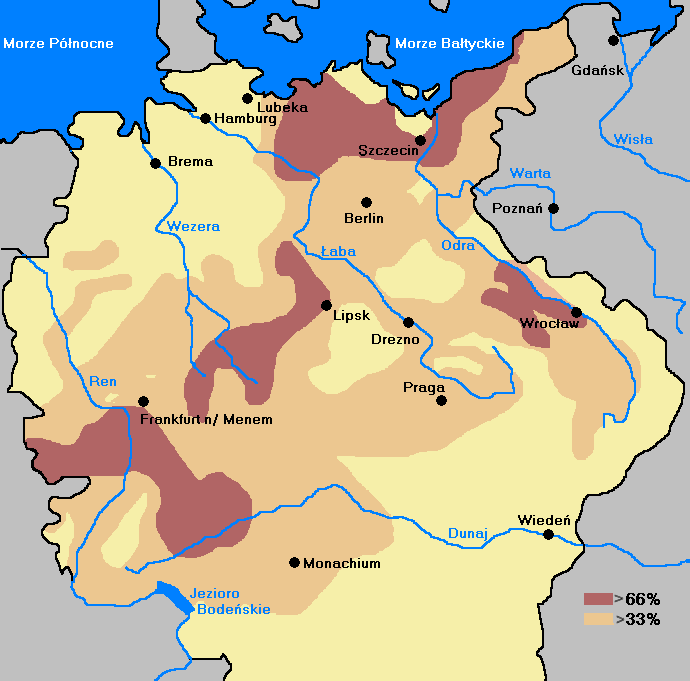

The Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Years War, showing which areas suffered the worst depopulation.

Another factor in the war's devastation was that many soldiers were mercenaries. In the sixteenth century the medieval armies of knights and peasant levies went out of fashion, because a combined unit of musketeers and pikemen could beat them. However, such a unit required considerable discipline and drilling; a five-foot-long muzzle-loading musket was not very accurate, and the pikemen had to protect the musketeers while they reloaded. Most states did not know how to train competent musketeers and pikemen, so they resorted to hiring professionals, who saw war as a business and didn't care what nation or religion they were fighting for. Often the participating states did not have the money to pay their soldiers, so looting and pillaging became commonplace around every camp, and soldiers would torture helpless civilians who could not, or would not, supply their needs. A vicious circle developed; many civilians joined the army so that in this eat-or-be-eaten society they would be the looters, not the looted. As a result, even the presence of a friendly army on a ruler's land was a nightmare to him, and much of the war's strategy centered on finding a good place for a winter campsite. It got to the point that the arrival of an army in a neighborhood was always an unwelcome sight, and small groups of soldiers who strayed from the main body were likely to be attacked by peasants wielding pitchforks and shovels, no matter what side they were on.

Nobody in 1618 expected a big war to engulf Europe, but they expected many small conflicts. The truce between Spain and the Netherlands was due to expire in 1621, and since Spain had never recognized Dutch independence, King Philip III prepared for a rematch, to avenge this blow to Spanish pride. Denmark, Sweden, Poland and Russia all had grudges against one another, but a northern war didn't appear likely to spread beyond the Baltic. To the southeast, the Balkans were quiet after the most recent Balkan war ended in 1606; the Ottoman Empire now suffered through a series of mad sultans who were only a threat to their own subjects.

In France, Louis XIII had grown up, and quarreled with his mother Marie over French policy; Marie was pro-Catholic and favored peace with Spain, while Louis saw the Hapsburgs and the Papacy as threats. The scales tipped in favor of Louis in 1624, when he got a powerful chief minister, Armand Jean du Plessis--better known as Cardinal Richelieu--who saw things the same way as he did. Richelieu dedicated himself to strengthening France, and more than anyone else is responsible for the absolutism that characterized the French monarchy after Louis XIII. Seeing the Huguenots as a threat, Richelieu ordered an attack on La Rochelle, the main Huguenot stronghold, in 1628, but afterwards continued to allow the Huguenots freedom of worship. In 1630 he succeeded in banishing the queen mother; this made him the most powerful man in the country, and under him France now resumed an active foreign policy.

The Bohemian Phase

Religious intolerance in central Europe resumed under the first Holy Roman emperor of the seventeenth century, Rudolf II (1576-1612). He destroyed many of Germany's Protestant churches, and used the Treaty of Augsburg as an excuse to tyrannize the Protestants in Hapsburg territory. Nor was he the only head of state to do so; the conversion of a prince--or the crowning of one who followed a different faith from his predecessor--had horrible consequences for the people living in that state. Protestants tried to protect themselves by creating an alliance of princes and cities called the Evangelical Union (1608), and when an anti-Protestant alliance called the Catholic League was formed in the following year, the Empire was polarized to the point that another religious war became inevitable.

The spark that set the continent ablaze was lit in Bohemia, where memories of the Hussites were still strong. If there was one man who started it all, it was Christian von Anhalt, the chief advisor to Frederick V, elector of the Palatinate. The Bohemian Protestants wanted to be ruled by one of their own, and Anhalt saw this as a way, for the first time, to elect a Protestant emperor. The Holy Roman emperor who succeeded Rudolf, Matthias, was no friend of Protestantism; among other things, he was in the habit of putting Catholic priests in charge of Protestant churches. However, Matthias was also old, unambitious, and childless, so Anhalt and the Bohemians bided their time. If they could elect a Protestant king in Bohemia, he would cast the deciding vote in the next imperial election, since among the other electors, three were Catholic archbishops and three were Protestant princes.

Anhalt's plan began to go wrong when the Hapsburg family chose a nephew of Matthias, Ferdinand II, to be the king of Bohemia, dispensing with the expected election (Matthias had been elected previously, but now he said that was a special situation that did not need to be repeated). Even worse, the Bohemians gave Ferdinand II the benefit of the doubt, choosing not to oppose him at this time. Ferdinand, however, was a pious Catholic, who had already eradicated Protestantism from the estates he had ruled in Austria, and felt compelled to show who was in charge. During the next year his repressive anti-Protestant measures did more to unite his opponents than anything they did themselves. On May 23, 1618, a mob of enraged Protestants broke into the castle in Prague, seized two of Ferdinand's ministers and their secretary, and threw them out of a third-story window. This event was called "the Defenestration of Prague," and Catholics called it a miracle because the Hapsburg agents fell seventy feet without suffering serious injury (Protestants noted that they landed in a dungheap); in effect it was Bohemia's declaration of independence from Hapsburg rule.

Within four months of the Defenestration, two Hapsburg armies, one from Spain and one from Austria, entered Bohemia to crush the rebels. To oppose this the Bohemians had a hastily recruited force of 16,000 men--quite inadequate to face this threat. The day was saved, however, by the arrival of another Protestant army, 2,000 professional soldiers sent by Frederick of the Palatinate and Charles Emanuel, the Duke of Savoy; they were led by Ernst von Mansfeld, one of the greatest mercenary commanders of the day. With the arrival of this army, the imperial forces withdrew; the Bohemian crown was now offered to and accepted by Frederick. Meanwhile in Austria, Emperor Matthias died, and things didn't look good for Ferdinand to succeed him; a Bohemian army even besieged Vienna in early 1619.

We noted in previous chapters how the German princes were obsessed with their personal freedom, but they were even more obsessed with the idea that a prince could only earn his crown legally. Thus, when Frederick took over Bohemia, no Protestant prince wanted anything to do with him; moreover, Frederick was a Calvinist, so the Evangelical Union, which was largely Lutheran, didn't even see much in common with him on religion. When imperial elections were held (August 28, 1619), the vote was unanimous for Ferdinand II. The three Catholic archbishops voted for him automatically, and Ferdinand, as elector of Bohemia, cast his vote for himself, leaving the three Protestant electors (including Frederick) no choice but to do the same if they wanted to appear loyal. The man Bohemia had rejected as king was now the emperor! Overnight Frederick went from being the champion of Protestantism to a vassal rebelling against his master.

Ferdinand only had enough soldiers to keep the peace in Austria, but he managed to get cash from the Papacy and armies from Spain, Bavaria, and Saxony. Against this Frederick had Mansfeld's army, some troops from Transylvania (used to open a second front in Hungary) and a subsidy of 50,000 florins from the Netherlands. Before any battles took place, Mansfeld deserted Frederick, because his employer could no longer pay him; that act sealed Frederick's doom. While the Saxons overran Lusatia and Silesia, and Spanish troops invaded the Palatinate, the Bavarians under Johann, Count of Tilly, conquered Bohemia (1620). Tilly won a key battle at White Mountain, and for Frederick, the sight of his troops fleeing back into Prague was enough to make him throw in the towel; he fled with his queen to the Netherlands, where he spent the rest of his life dreaming of a new Protestant league (the Evangelical Union had dissolved itself), with fruitless schemes to regain his lost lands and titles. Back in Germany, Frederick's enemies called him "the Winter King," because his reign over Bohemia had only lasted for one season.

Mansfeld took his army to the Rhine, but failed to keep the rest of the Palatinate from falling into Catholic hands. Though he claimed he was continuing the war in Frederick's name, it was really an excuse for his troops to live off the land by pillaging, and they treated German Protestants in the west almost as badly as Catholic soldiers did. By 1623, most of the fighting appeared to be over, so Ferdinand handed out big rewards to his allies for their service, giving Lusatia to Saxony, Alsace to Spain, and half of the Palatinate to Bavaria; the prince of Bavaria also became one of the Empire's seven electors, taking his vote from the Palatinate. For himself, Ferdinand kept Bohemia and Silesia, and punished the Bohemians terribly. A new constition replaced the old-style feudalism with an absolutist government, half of the land belonging to Czech nobles was confiscated, and a wave of executions and forced conversions followed, causing 150,000 to emigrate, and beginning the traditional Czech hatred of the Germans.

The Danish Phase

The expiration of the truce between Spain and the Netherlands saw them resume fighting almost immediately. What this meant for the main war was that Spain could only help Austria in the western half of the Empire, though the Spaniards eagerly did so when they got the chance. The only Spanish victory that mattered was at Breda, in 1625. After that, the Dutch slowly advanced southward, taking Hertogenbosch (1629), Maastricht (1632), and Breda (1637). The Dutch even did better at sea; in 1628 Admiral Piet Hein made one of the greatest heists in history when he captured that year's shipment of American silver for Spain, in the strait between Florida and Cuba.

To the east, the looting of Bohemia gave Ferdinand the resources he had lacked previously, and one of his dukes, Albrecht von Wallenstein, began to raise a new army which--unlike Tilly's--took orders from no one but the emperor. A clever general with great ambitions, Wallenstein looked at Mansfeld's methods, and saw in them a way to finance an army without costing the emperor a penny. Ferdinand agreed to let him try, if he thought he could raise ten thousand men that way, and Wallenstein said ten thousand was only the beginning: "If I have only ten thousand, we must accept what people choose to give us. If I have thirty thousand, we can take what we like." This strategy meant that no matter who won the war, the result wouldn't be a kinder, gentler Germany. Wherever Wallenstein's men marched, the local residents would have to pay for, feed and quarter them. If the locals were loyal, Wallenstein would take "contributions to the necessity of the empire"; if they opposed him, he would simply plunder them, with no words needed to justify his behavior. Just the promise of plunder was enough to recruit nearly fifty thousand men in the first three months.

By this time the second phase of the war, the Danish phase, was underway. Tilly advanced into northern Germany, to defeat the remaining Protestant forces, and the Protestants called for help. King Christian IV of Denmark gladly became the new Protestant champion, forming an alliance with England and the Netherlands in December 1625, before coming to the rescue. It didn't work; Tilly defeated the Danish king at Lutter, while Wallenstein defeated Mansfeld at Dessau and chased him to Hungary, where he soon died of a fever. By this time Wallenstein had 125,000 men in his force, an awesome number by early seventeenth-century standards.(1) Together Tilly and Wallenstein pushed Christian IV back into Denmark itself, defeating him again at Wolgast (September 1628), and devastating Jutland until he prayed for peace at any price. Then Wallenstein wasted the northern state of Mecklenberg, becoming the "Generalissimo of the Baltic and Ocean Seas." His only defeat came at Stralsund, in 1628; Sweden sent enough soldiers to keep that port in Protestant hands.

Christian IV avoided losing any Danish territory by signing the treaty of Lübeck (1629) and dropping out of the war. Ferdinand was now master of most of Germany, and he used his new power to strengthen Catholicism: he issued a decree ordering the return of all Church-owned lands confiscated by Protestants since the Treaty of Augsburg (the Edict of Restitution), and outlawed all Protestant denominations except Lutheranism. Wallenstein received a conquered state as his duchy, and he declared that his master should now govern Germany as a unitary state like France or Spain, with no more reliance on princely councils. All this alarmed the German princes; they had opposed Charles V when he tried to become a strong emperor, and even Catholic states like Bavaria didn't want Ferdinand to succeed where Charles had failed. Concerned about losing their "liberties," the Catholic electors met with Ferdinand at Regensburg in 1630, where they warned him that if he didn't want to run the risk of having the Hapsburgs lose the imperial crown, he would have to fire Wallenstein. Ferdinand reluctantly complied, and Wallenstein, to everyone's relief, accepted his dismissal quietly. A believer in astrology, Wallenstein said that he had seen a horoscope which predicted that evil men would get between him and his master, but they would not cause the end of his career.

The Swedish Phase

During the Danish phase of the war, Cardinal Richelieu got involved behind the scenes. He kept Germany disunited by sending his best diplomat, the Capuchin Father Joseph de Tremblay, to the meeting where the princes pressured Ferdinand for the removal of Wallenstein. Richelieu did this because he wasn't going to let the war end, even if the Germans had run out of things to fight over. As long as the conflict went on, it consumed the resources of France's rival, the Hapsburgs, so he subsidized the Dutch in their ongoing rebellion against the Spanish Hapsburgs, and the Danes against the Austrian Hapsburgs. Consequently he would spend the rest of his life backing the Protestant cause in the war, though his high position in the Catholic Church would make one expect him to work for the other side. When Denmark dropped out, he looked for someone else to fight the Austrians; he found the perfect replacement in the king of Sweden.

War was the hobby of Gustavus Adolphus, the "Lion of the North," and because he was good at it, he rushed from one campaign to the next, using the spoils of his victories to keep the Swedish treasury full. Early in his reign he enlarged the army with conscription, rather than relying on an all-volunteer force, and brought it up to date by adding two tactical innovations: a mobile field artillery and flintlock muskets. Most armies of the day used bombards, huge cannon that consumed gunpowder, metal and gunners (when they blew up) at a frightful rate, took up to half an hour to reload, and were difficult to aim at anything smaller than a fortress. By contrast Gustavus used only light cannon, mounted on carriages with trunnions; he realized that several small, well-placed shots could get better results than one big shot. The flintlocks were a vast improvement over the match-lit guns most soldiers used at this point, allowing the musketeer to reload faster and aim without worrying about the blast singeing his eyebrows. In fact, speed was the most important element in Gustavus' strategy.

He soon got a chance to test the new tactics and equipment. In 1617 the war between Sweden and Poland resumed, and this time the advantages were with the Swedes. Gustavus personally led the 16,000-man force that besieged and took Riga; by the end of 1621 all of Livonia and Kurland had been conquered. In 1626 he opened a new front with an amphibious assault on Prussia, which had come under Polish rule after the dissolution of the Teutonic Knights. He cleared the Poles out of Prussia with the help of reinforcements in the following year, and the war became a stalemate between the Swedish and Polish cavalry, on the Polish frontier. They agreed to a new truce in 1629; Sweden returned Prussia but gained all of modern Latvia. The Swedes also got the right to use the Prussian ports, except for Danzig, Konigsberg, and Puck (on the Vistula); the tolls collected from those ports greatly increased the Swedish government's income. Gustavus Adolphus was now the unquestioned master of the Baltic.

While fighting the Poles, Gustavus watched the situation in Germany, and grew increasingly alarmed. In 1627 he compared the Catholic advance to a rising tide: "As one wave follows another in the sea, so the Papal deluge is approaching our shores." After the treaty of Lübeck was signed, he predicted that the next war would be between the Germans and the Swedes, and did everything he could to make that happen. He cooperated with the envoys Richelieu sent to negotiate an end to the war with Poland; then he landed at Peenemünde with 4,000 men on June 6, 1630. He spent the rest of the year conquering Pomerania and recruiting Germans into his force, before he felt strong enough to strike into Germany's interior.

The discipline of the Swedish army was remarkable. Gustavus forbade his troops to attack churches, hospitals or schools, and they obeyed him. The only time they looted, raped or killed was on his command, not when they felt like it. They were loyal because of the king's personal qualities. His kingdom was the best administered in Europe, and he followed his men into every battle, sharing their hardships and infecting them with his self-confidence. One observer commented that "He thinks the ship cannot sink that carries him."

German Protestants, who now viewed Gustavus as their protector, welcomed him, but the princes felt otherwise. The emperor expected Gustavus to be no tougher than his other northern opponents, remarking that: "Another of these snow kings has come against us. He, too, will melt in our southern sun." The rulers of the two largest Protestant states in Germany, John George I of Saxony and George William of Brandenburg, weren't thrilled either. George William was particularly mad at the Swedes; he couldn't defend Prussia because of the war at home, and consequently saw Poland and Sweden fight over land and money that really belonged to him.(2) John George didn't want anything to do with an anti-Catholic crusade, though his state was the birthplace of the Reformation; he had gained Lusatia by serving the emperor. In early 1631 John George and George William presided over a conference of Protestant princes at Leipzig, and they raised an army of their own, led by Hans George von Arnim, a former officer of Wallenstein who had resigned in disgust after the Edict of Restitution.

The anti-imperial campaign was delayed for several months because it wasn't clear that the French, the Swedes and the German Protestants would be able to work together. Richelieu got the Swedes to cooperate by having Gustavus sign the treaty of Barwalde in January 1631; in return for full Swedish cooperation with French foreign policy for the next four years, France would pay 1 million French livres (about $9.4 million in today's money) a year. Then Gustavus bullied Brandenburg into joining him by marching on Berlin. As for the Saxons, Tilly made up their mind for them. In May Tilly besieged and captured Magdeburg, an important city near Saxony which Wallenstein had avoided when he marched through the area; 20,000 civilians were killed in the fires which destroyed the city. Tilly followed this up with an invasion of Saxony itself, arguing that the elector of Saxony had shown his disloyalty to the emperor, by not enforcing the Edict of Restitution in his territory, and by allowing the formation of a rebel army. Leipzig fell in September, leaving John George no choice but to join Gustavus. On September 17, Tilly's troops met the Swedes and Saxons at Breitenfeld, a suburb of Leipzig. The Saxons fled at the first charge, exposing Gustavus' left flank and nearly costing him the battle, but he regrouped his forces and demolished the imperial army with a counterattack of his own. Breitenfeld was the most brilliant Protestant victory of the war; with one stroke, Sweden had become the dominant nation of northern Europe.

Gustavus Adolphus at Breitenfeld.

After Breitenfeld the two partners separated; the Saxons invaded Bohemia and captured Prague, while Gustavus marched to the Rhineland, occupying the Lower Palatinate and the bishoprics of Mainz, Bamberg and Wurzburg. Gustavus now treated Germany as if it were part of Sweden, making Mainz his second capital and appointing his prime minister, Count Axel Oxenstierna, governor-general over all conquered German territory. Even Richelieu grew concerned about Sweden's growing power, and offered French protection to any prince who asked for it, but only the Archbishop of Trier took him up on the offer.

Gustavus spent the winter building up his forces. By the spring of 1632, he commanded seven armies totaling 80,000 men, and when he talked about recruiting 120,000 more, many felt he could do it. When Gustavus broke from winter camp, Tilly had to fall back to Bavaria; Gustavus pursued, and Tilly was mortally wounded by a cannonball, at the battle of the Lech River. As the Swedes plundered Bavaria, Ferdinand knew that Austria would be next, and that only Wallenstein could save him. Wallenstein, who had been living like a king on his Bohemian estates since we last heard from him, rejected several pleas from the desperate emperor, until he got incredible terms: He would be the second most powerful man in the Empire, and wholly independent of his former master, making war or peace without any interference from the Hapsburg family; he even received some Austrian provinces to hold as a guarantee of the emperor's good faith.

Wallenstein reconquered Bohemia in May and June, and then cautiously entered Bavaria to challenge the Swedes. In September Gustavus attacked Wallenstein's force, which had placed itself in a very strong position near Nuremberg--and suffered his first defeat. Wallenstein chased Gustavus through Franconia and Swabia for the next six weeks; Gustavus tried to draw him into a formal battle without success. Then the campaign season ended, and Wallenstein marched to Saxony so he could spend the winter on enemy territory. Gustavus followed, and on November 16th, 1632, he reached Wallenstein's campsite at Lützen, and launched an immediate attack. Timing wasn't on his side; Wallenstein wasn't surprised, and the emperor's most daring cavalry general, Gottfried Heinrich Pappenheim, was less than a day's march away with his own force. Pappenheim arrived in time to take part in the battle, and soon was killed; a heavy fog on that autumn day added to the confusion, causing the three armies to march around each other in a full circle before they realized it. Galloping in front of his army, Gustavus was knocked off his horse by a shot (it may have been a case of "friendly fire," as it came from his German allies), and then was surrounded and finished off by a band of enemy cavalry. The Swedes stayed together and charged to avenge their leader; at the end of the day the Wallensteiners fled to Bohemia.

Though the Swedes had won Lützen, the death of their king was a critical loss, and neither the Swedes or the Germans could find a charismatic leader to take his place. Gustavus was succeeded by a six-year-old daughter, Christina, and since she obviously could not lead armies, Duke Bernard of Weimar and Sweden's Count Horn took charge of the troops, while control of the government went to Prime Minister Oxenstierna(3). However, the advantage of speed and offensive power remained in the Swedish camp. The Catholic coalition had its own leadership problem--Wallenstein was no longer trustworthy. He didn't do much campaigning in 1633, preferring to negotiate with the Saxons and Swedes instead, going so far as to exchange captured Swedish generals for some fortresses in Silesia. In addition, he was ill with gout and depression, and this may have prompted him at a banquet to make his leading officers sign an oath promising to stand by him in whatever he did. Finally, there were rumors that he was about to make himself king of Bohemia, and/or begin negotiations with the French. All this looked like treason to Ferdinand, and in February 1634 he had Wallenstein murdered through a conspiracy among his officers. Then Ferdinand appointed his son, Ferdinand III, as the new commander of the Catholic forces.

The Protestants had an easier time of it in 1633; in Bavaria they captured Regensburg, which had escaped Gustavus a year earlier. However, the younger Ferdinand got along well with his Spanish relatives, and together they worked out a plan: Spain had just raised a new army in Italy to use against the Dutch, and it would assist Ferdinand on its way through Germany. In September 1634 the Spanish and Austrian armies met at the Bavarian town of Nördlingen, and the Protestant army, despite being outnumbered nearly 2 to 1, attacked, in an effort to split the Catholic force into small, easily eliminated units. Instead, it was a disaster; the Spaniards stood their ground through repeated assaults until the attackers were worn out. Then the Catholics took the offensive; Count Horn was captured, and the elite force of Gustavus was annihilated.(4)

The French Phase and the Treaty of Westphalia

The Spanish army resumed its journey to Belgium after Nördlingen, and what was left of the Swedish army (now mostly mercenaries rather than Swedish nationals) withdrew to the north. Both sides realized that sixteen years of fighting had produced one result, and a negative one at that. The only sensible thing the factions could do was settle their differences and get to work repairing the ravaged land. Accordingly, in early 1635 the German princes and the emperor met in Prague and agreed to make peace. This time Ferdinand was more willing to compromise, and won over many Protestants by voiding the Edict of Restitution. In addition, he got the secondary states to accept his increased authority by recognizing their wartime gains: Bavaria got both halves of the Palatinate, Saxony was allowed to keep Lusatia, and Brandenburg was promised Pomerania, once the Swedes were cleared out of it.

Unfortunately, you can only have peace if all parties agree to it, and Richelieu didn't want anything to do with the deal the Germans had worked out. As early as 1632 he had begun moving French troops into Alsace and Lorraine; if he let the war end now, it would leave the Hapsburgs in control of most of Germany, with Ferdinand II as the first real German emperor in 400 years. The only allies remaining on his side were the Swedes and Bernard of Weimar (who commanded a German Protestant army in Alsace); if he was going to keep his enemies from winning, he would have to enter the war himself. By doing so, he transformed the war from a religious dispute into a struggle for supremacy between the Bourbon and Hapsburg royal houses. Within days of the Peace of Prague (May 1635), France declared war.

No matter what it cost, Ferdinand should have made a deal with the French and/or the Swedes. However, he didn't see it this way; he was at the peak of his career, and Nördlingen made him think that he could beat anybody who tried to disrupt his settlement. The French soldiers were inexperienced, so once the decision had been made to fight, the Hapsburgs did better; a Spanish army captured Trier and its pro-French archbishop, and successfully defended Belgium from both the French and the Dutch. The Hapsburgs also enjoyed nationalistic support from those Germans who didn't want to see any part of the Empire fall under French rule. But then things started to go wrong. A three-pronged attack on France from Belgium, Germany and Spain was thrown back before it got to Paris, and the supposedly demoralized Swedes beat a combination of Saxons and Imperials at Wittstock in Brandenburg (both events occurred in 1636). A subsequent defeat at Torgau forced the Swedes back into Pomerania, but in 1638 they broke out again and in 1639 raided Bohemia as far as the suburbs of Prague. On the western front, the French-led coalition took the offensive; in December 1638, Bernard conquered Briesach on the east bank of the Rhine. For the new emperor, Ferdinand III (Ferdinand II had died in 1637), all the news must have looked bad.

Next, an unexpected string of calamities knocked Spain flat. In October 1639 a second Spanish armada, numbering 67 ships and 20,000 soldiers, set sail for the Netherlands; the Dutch fleet, led by Admiral Maarten Tromp, destroyed it in the Strait of Dover (the battle of the Downs). Three months later, the Dutch beat a combined Spanish and Portuguese fleet in the battle of Pernambuco, near the Brazilian port of Recife. Spain itself collapsed in 1640, when Catalonia and Portugal revolted. The Spanish government tried to get the Catalonians to supply taxes and conscripts at the same rate as Castile, and Catalonia--medieval Aragon--invited the French to take over the province (Barcelona had been part of Charlemagne's Spanish March); the Catalonians and French fought side-by-side when they defeated a Castilian army outside Barcelona in January 1641. The Portuguese had a different grievance; their empire had suffered from neglect and Dutch naval attacks since the union with Spain in 1580, and they expected to lose everything if they did not regain independence. King Philip IV fired the minister responsible for the tax reform, Gaspar de Guzmán, conde de Olivares, but he was unable to put down the rebellions. Nor could he use the Spanish armies in Belgium and Italy; Richelieu would see the removal of either as a signal to conquer the territories they defended.

The army in Belgium was now under attack from two directions, but it could still help by creating a diversion big enough to draw French troops from Catalonia. That is what the local Spanish commander had in mind when he attacked Rocroi, a fort on the Franco-Belgian frontier. His French counterpart, twenty-two-year-old Louis II, Prince of Condé and Duke of Enghien, came to the rescue with 22,000 men. The Spanish force was slightly larger, at 25,000, and when they met on May 19, 1643, they drew themselves into similar formations, each putting its infantry in the center and the cavalry on the sides. The next moves were also identical, with the right cavalry wing of each side advancing. Personally leading the cavalry on the French right, Condé scattered the Spanish left, then went behind the Spanish infantry to hit the Spanish right cavalry in the rear, just in time to save the French left. Once the Spanish cavalry had fled, the entire French army surrounded the Spanish infantry. However, these foot soldiers were not mercenaries or conscripts, but the Tercios, Spain's finest force for more than a century; it took four combined assaults by cannon, cavalry and infantry to finish them off. Rocroi was more than just a tactical defeat for Spain; France had replaced Spain as the strongest nation in western Europe.

Meanwhile, the Austrian Hapsburgs were doing no better against the Swedes. The Austrians and Swedes met for a rematch at Breitenfeld in November 1642, with the same results as the first battle--a total Swedish victory. 1643 saw Denmark's Christian IV, who was envious of Sweden's success, re-enter the war, this time on the Hapsburg side. The Swedish general, Lennart Torstensson, had to call off a march on Vienna so he could beat up the Danes, but otherwise everything went in his favor. He quickly occupied Schleswig-Holstein and Jutland; by 1645 Christian was forced to sign a treaty that ceded the provinces of Jamtland and Halland to Sweden, along with the Baltic Islands of Gotland and Oesel. Back in Germany, the Swedes managed to win two more battles against imperial forces, at Jüterbogk and Magdeburg (both in 1644).

As early as 1640, at a session of the electors at Nuremberg, the opinion was expressed, that part of Pomerania should be given to the Swedes if this would satisfy them. Instead Ferdinand continued the war, so German princes began to grumble that they might have to make peace without him, since he was paying more attention to the needs of his Spanish cousins than to them. In addition, everyone agreed that the Eighty Years War was a wasteful diversion from the Thirty Years War, so in 1641, King Philip IV of Spain and the United Provinces of the Low Countries sent representatives to the German town of Münster, where they began negotiating terms that would end the Eighty Years War. Also in 1641, the elector of Brandenburg signed a neutrality agreement with the Swedes, and the other princes followed suit, before Swedish soldiers could plunder their lands. It was Rocroi that convinced Emperor Ferdinand that he could not win. When he got the bad news, he immediately called for a peace conference (the first international peace conference in history), with no preconditions. Because Richelieu had died in 1642, the French no longer tried to keep the Germans from coming to some form of agreement.

The conference lasted four years (1644-48) and was held simultaneously in two towns of Westphalia, Münster and Osnabrück. The first six months were spent haggling over matters of protocol and etiquette. The question of whether the representative of the king of France should enter a room before the representative of the king of Spain might not seem like a question worth answering in the middle of a war that was killing thousands, but in a time when memories of chivalry and feudalism were still strong, it was. The 109 participating delegations of diplomats had not practiced this form of international politics before, and ground rules had to be established before any sort of settlement was possible. That was why the conference took so long and why it had to be held in two places; because the Swedes refused to concede superiority to the French, they ended up negotiating with the Hapsburgs separately, France in Münster, Sweden in Osnabrück. Altogether it is amazing that the conference succeeded.

While negotiations took place, the war went on; every battle changed the bargaining positions of the various parties. The French suffered a bad defeat at Tuttlingen, Germany, in November 1643, but the rest of the time it was the imperial position that eroded; the Hapsburgs lost every other battle that mattered. By the end of 1643, Condé had begun to occupy Belgium, taking the provinces of Hainault and Luxembourg. The Dutch seized the mouth of the Scheldt River in 1644, while France captured most of Flanders in 1645 and Dunkirk in 1646. The combined armies of Condé and another young general, Henri de La Tour d’Auvergne, Vicomte de Turenne, defeated the Bavarians at Freiburg in 1644, and they avenged the defeat of Nördlingen by mauling an Austro-Bavarian force on the same spot (August 3, 1645). On January 30, 1648, the Spanish and Dutch ambassadors reached an agreement, and the treaty they signed, the Peace of Münster, was sent to the Hague and Madrid for approval. With this treaty, Spain recognized Dutch independence once and for all, and the Eighty Years War was ended. The following August, Condé won the last major battle in the big war, at Lens, France. Finally, on October 24, 1648, the last conflicting claims of the various belligerents were reconciled and two treaties were signed in Münster and Osnabrück on the same day; together we call these treaties the Peace of Westphalia.

The final score was that France and Sweden won and the German people as a whole (though not all the princes) lost. France got ten cities in Alsace, Breisach and Philippsburg on the opposite bank of the Rhine, and official recognition of the annexation of three Lorraine towns in the previous century (Verdun, Toul and Metz). This put all remaining German territory west of the Rhine in the French sphere of influence. Sweden got Hither (western) Pomerania, the port of Wismar, the bishoprics of Bremen and Verden, and a whopping cash sum worth $94 million in today's dollars.(5) The borders of the Holy Roman Empire shrank so that the Netherlands, Switzerland and north Italy were no longer within it. Brandenburg got the rest of Pomerania, the bishoprics of Halberstadt, Kammin and Minden, and the right to appoint the archbishop of Magdeburg. Saxony kept Lusatia, and Bavaria kept the Upper Palatinate and its electoral vote. The Lower Palatinate was restored to Charles Louis, the son of Frederick, and he became the Empire's eighth elector, to make up for the vote that had been transferred to Bavaria. The Hapsburgs kept Bohemia, and Upper Austria, which had been occupied by Bavaria while the French and Swedes were threatening Vienna, was returned to them. Thus, from Ferdinand's point of view, things could have been a lot worse, because the only territories he lost, Lusatia and Alsace, had already been signed away by his father. Finally, religious toleration of Calvinists, Lutherans and Catholics was promised by everyone.

England's Political Experiment

England did not do very well under the Stuart (Scottish) kings. We saw in Chapter 9 how Scotland's royal family had an awful time at home, and that bad luck followed them when they moved to London. England was delighted in 1613 when James I gave his daughter Elizabeth in marriage to Frederick of the Palatinate; we noted earlier that Frederick was a Calvinist. Then the English were outraged five years later, when James announced that his son Charles would marry Infanta, a Catholic Spanish princess. James pursued this strange proposal for years, despite the opposition of Parliament and the common people, even arranging for the execution of Sir Walter Raleigh, a notorious enemy of Spain.(6) He finally declared war on Spain in 1624--after Spain's Infanta rejected his son. All his reign he quarreled with Parliament over who should run foreign policy, dissolving it once when he could not get his way.

Some have said that James I steered the ship of state straight toward the rocks, but left his son Charles I to wreck it. Like his father, Charles believed in absolutism, and in addition was pro-Catholic in his sympathies, petty and weak willed, and totally incompetent where foreign policy was concerned (somehow he managed to get England involved in a war with France before it could get out of its hopeless war with Spain). These wars left the royal purse empty, forcing him to turn to Parliament for more money. Parliament was now largely Puritan, and in return for financing the crown, it called for the elimination of "papist" practices from the Church of England. The first three times this happened, Charles dismissed Parliament and arrested the leaders. The fourth time he asked it for money, the religious question came up again, and he tried to dismiss it, but this time the opposition physically held the Speaker of Parliament (who favored the crown) in his chair while it passed three resolutions. The first declared that anyone who tampered with England's established Protestantism was an enemy of the state; the second declared that anyone who imposed taxes without Parliament's consent was also an enemy of the state; the third said that anyone who paid illegally imposed taxes was a traitor to England. Once it finished this resounding act of defiance, Parliament voted to adjourn.

For Charles this was too much, and he decided that if he could not get along with Parliament, he would get along without it. For the next eleven years (1629-40) he ruled on his own, not allowing Parliament to convene. The only thing that kept him from being an absolute monarch was the lack of money. With no Parliament to approve new taxes, the king became very clever at finding other ways to make money. He fined citizens eligible for knighthood who did not become knights, pawned the royal jewels, sold trading monopolies in various fields of commerce, and made the entire country (not just the ports) pay the "ship money" tax, which supported the Royal Navy.

Charles might have gotten away with this indefinitely had he not insisted on imposing his religious views on everyone. The problem was that he was really king of three countries, each of which preferred a different denomination: England was Anglican, Scotland was Presbyterian, and Ireland was Catholic. For all his failings, James I had enough sense to leave the Scots and Irish alone. Not Charles. In 1637 he and the Archbishop of Canterbury decided to make everyone in Scotland join the Church of England. The Presbyterian Scots swore to resist to the death. Charles decided to raise an army against Scotland, but this would cost more than a million pounds, a sum of money that could only come from Parliament. He allowed Parliament to convene for this purpose in 1640, but it insisted on talking about eleven years of grievances, so three weeks later the king dismissed this; this was called the Short Parliament. A few months later a Scottish army invaded the northern counties of England, so Charles, now desperate, allowed Parliament to meet again. This was the beginning of the Long Parliament, which held a nearly continuous series of sessions for the next thirteen years.

The Long Parliament permanently destroyed the power of the king. It took away his right to dissolve Parliament, passed an act requiring the king to call a session of Parliament at least once every three years, and declared all taxation without its consent invalid. Ever since that time, Parliament, and not the monarchy, has been the most powerful body in the English government. The king accepted these measures, but balked when the religious question came up again; Parliament also wanted to do away with the Church of England's bishops and the Book of Common Prayer.

By 1642 relations between the king and Parliament were so bad that the king, fearing for his safety, moved the royal court from London to York. Parliament voted to raise an army, and Charles called upon his loyal followers to join him. That marked the beginning of the English Civil War. The king's followers, mostly aristocrats, were called Cavaliers because of their fancy hairstyles and clothing, and a dashing, "devil-may-care" attitude; they believed in a strong monarchy and the Church of England. Parliament's champions were called "Roundheads" because they had short hair and simple helmets; they wanted to limit or destroy the monarchy, and favored either a Presbyterian-style church running the whole country, or independent Puritan congregations.

The first two years of the war saw both sides evenly matched, with neither gaining a clear advantage over the other. By the end of 1643 the king's forces controlled three quarters of the country, but Parliament offset this in early 1644 with a treaty that brought Scottish arms to its side. The balance changed when a Puritan member of Parliament, a country gentleman named Oliver Cromwell, turned out to be a military genius. He organized and trained an army in his native East Anglia so effectively that it got the nickname "Ironsides," because as Cromwell said, it could not be "broken or divided." When this unit won a major victory (the battle of Marston Moor, July 1644), Cromwell was promoted to command all Parliamentary forces, so he could convert them into "Ironsides," too. He succeeded, and one year later the Roundheads were unstoppable.

The secret behind Cromwell's success was a remarkable combination of humility, arrogance, tolerance and firmness. He always believed he was doing the Lord's will, and that God knew it. At another battle he won, the battle of Naseby (June 1645), he showed the same kind of faith expressed by the heroes of the Old Testament. Afterwards he wrote, "I can say this of Naseby: that when I saw the enemy draw up and march in gallant order toward us, and we a company of poor, ignorant men . . . I could not . . . but smile out to God in praises, in assurance of victory, because God would, by things that are naught, bring to naught things that are. Of which I had great assurance. And God did it." His sense of divine mission forged an army that fought for a cause, rather than pay or spoils, but he never expressed to the common soldiers his own tolerance for other men's beliefs, so his army also became an army of fanatics; this would be Cromwell's great tragedy.

Oliver Cromwell.

After Naseby, King Charles surrendered, but he surrendered to the Scots, thinking that he would be treated better in the country of his ancestors. Then the Puritans started arguing; moderates in Parliament wanted a (limited) king and a national Presbyterian Church, while radicals in Cromwell's army wouldn't stand for either. Seeing his enemy divided, Charles made a deal with the Scots, promising to make England join the Scottish Presbyterian Church if they would take up his cause, but Cromwell crushed the Scottish army at the battle of Preston in August 1648. This second war only served to destroy the compromise which many still believed was possible. Now Cromwell started the country on a course which could not be halted until it had reached its conclusion. When the victorious soldiers returned to London they expelled 140 Presbyterian members from Parliament, leaving only a "Rump Parliament" of 60 Puritans. Then Parliament put Charles on trial for his life, knowing that if the king had won he would have shown no mercy toward them. They beheaded him on January 30, 1649, and he went to his execution with a dignity rarely seen in his 24 years on the throne. All was not lost for the Stuarts, though; Royalist factions held out in Ireland and Scotland.

As in other times, Ireland was a constant problem for Cromwell. In 1641 the Catholic gentry of Ireland tried to seize control of the English government in Dublin, and get it to grant concessions to Catholics. The coup failed, and it was followed by a general rebellion of the Catholic population, against the (Protestant) English and Scottish settlers the government had supported. By the summer of 1642, two thirds of Ireland was under Catholic rule, and they established a government at Kilkenny Castle, which was called the "Catholic Confederation." However, Irish Catholics claimed they were still loyal to King Charles I, and that made Parliament their enemy. After Cromwell abolished the monarchy in England, he sent an army to Ireland to crush the rebellion. The reconquest of Ireland was a brutal campaign lasting nearly four years (1649-53). When it was done much of Ireland's population was dead (nobody agrees on how many were killed), the native Catholic land-owning class was destroyed, and more Protestant colonists took their place. Understandably, Cromwell is still hated in Ireland today.

At Charles' trial, Cromwell declared, "We will cut off the king's head with the crown on it," so for the next eleven years England had no king. Instead it was a Puritan "commonwealth," run by a military junta in which Cromwell was the dominant figure. The force that ultimately made this government fail was the intolerance of those who ran it. Determined to destroy all ungodliness, they established what they called a "rule of the saints," based on the Biblical laws of Moses. These men had no patience with checks & balances or secular laws, and put in their place a tyranny of the saints.

Cromwell did everything he could to control them. In 1653 he persuaded Parliament to adopt a constitution, called the Instrument of Government. It declared Cromwell to be the state's Lord Protector, and under him was an executive body called the Council of State. It also guaranteed religious freedom to all Christians except Anglicans and Catholics. The Puritan-run Parliament, however, refused to abide by its terms, and Cromwell had to rule as a dictator, calling himself "Lord Protector" and using military force to get things done.

Oliver Cromwell died on a stormy day in 1658. His son Richard took over, and he couldn't get along with either the army or Parliament; after eight months he resigned. Nowadays, if history books mention Richard Cromwell at all, they call him by the nicknames given to him by his enemies: "Tumbledown Dick" or "Queen Dick." By this time England was tired of revolution and Puritanism, and when Charles II, the son of the executed king, promised to rule as a limited monarch, he was invited to return from exile in France.

The Stuart Restoration

The twenty-five-year reign of Charles II (1660-85) was the most successful of the Stuart dynasty. Under him the whole tone of English life changed. Having been brought up at the French court (we are now up to the time of Louis XIV), the young king introduced to England the extravagant art and lifestyle he had seen there. The drab, serious clothes of the Puritan era gave way to elegant fashions and enormous wigs, and Charles imitated Louis by keeping a series of mistresses.(7) He went too far with this, though; Charles actually refused to share the bed of his queen, the Portuguese-born Catherine of Braganza, so he had fourteen illegitimate children, but no official heir to the throne. In a deal worked out with Parliament, Charles arranged to have his Catholic and not-too-bright brother, James, the Duke of York, become his successor.

Even the physical appearance of London changed; after two thirds of it was destroyed in the great fire of 1666, it was rebuilt fancier than before, with 52 churches, including St. Paul's Cathedral. The theaters, once banned as sinful and godless places, reopened. Occasionally there was a voice from the Puritan past (John Bunyan and John Milton wrote their great Christian novels, Pilgrim's Progress and Paradise Lost, during this time), but it was seldom heard in the constant party at the court of Charles II.

It was during the reign of Charles II that England developed the obsession with tea that has characterized the English since then. In the mid-seventeenth century, tea was available in Portugal and the Netherlands, because those countries had trade networks in Asia, but the tea that reached England was of poor quality and frightfully expensive, so hardly anybody drank it. One pound of tea could cost as much as £2, and in those days the average English worker earned £2-6 a year. In fact, tea was used for medicine more often than it was used for pleasure. Well, both Charles and Queen Catherine had acquired a taste for tea before moving to England, so because of them, tea gained a reputation in England as the drink of cultured nobility. In 1668 the English East India Company began bringing back tea from Asia, which both lowered the price and improved the quality.

On the other hand, Charles did not like coffee, which had also been introduced to England a few decades earlier. Somebody back then described coffee as a drink resembling "syrup of soot and essence of old shoes"; nevertheless, coffee houses became places where members of the middle and upper classes liked to meet. Here they would read, make business deals, debate the issues of the day, pass out newspapers and pamphlets, and make announcements that businessmen would find interesting, like upcoming sales and auctions. What bothered Charles was that unlike the customers in taverns, coffee house patrons stayed fully alert, because they consumed caffeine instead of alcohol, and often their conversations were plots against the king or the Catholic Church. In 1675 he actually decreed a ban on coffee houses and the sale by retail of coffee, chocolate, sherbet and tea. As you might expect, there was an immediate outcry in London. The Englishmen who loved coffee included the king's ministers, and they persuaded Charles to void the decree before it went into effect; Charles knew from his father's experience what can happen when a king becomes unpopular!

Charles II, like the previous Stuarts, believed in a moderate Church of England with himself in charge of it, but he also had the diplomatic and political skills the other Stuarts lacked. He succeeded where his father and grandfather had failed in doing two things: living with Parliament and living without it. He accomplished the first by making sure a bunch of men who agreed with him were always in Parliament, and organized them into the first modern political party--the Tories. Getting along without Parliament was more difficult, since it meant getting along without Parliament's money (Charles had a reputation for spending more than he should). In fact, the government defaulted on its debts in 1672, when Charles declared no payments could be made that year. Still, he found a way to get the cash he needed. Louis XIV of France wanted to see Parliament as inactive as possible, since an active Parliament full of Protestants was likely to start a war with France. In 1670 Louis and Charles signed a secret treaty which gave the English king an annual subsidy of £100,000 in return for a promise from Charles to never call Parliament to session except when required to by law. Charles also promised English non-interference in French foreign policy (Parliament wouldn't let him keep this), and to turn Catholic. Charles knew the last item would be very unpopular, so his conversion was not made public until he was on his deathbed, though there is good evidence that he considered himself a Catholic long before that time.

No wonder Charles II never had enough money. Wigs and costumes as good as these are expensive!

While Charles II was alive, rumors of his treaty with the French leaked out. And despite what the king said in the previous footnote, there was a rumor of a "Popish Plot," which asserted that Jesuits in England were planning to assassinate the king, so that James could take his place. This was completely false, but it caused a wave of anti-Catholic hysteria in England and Scotland, which lasted from 1678 to 1681. Charles had to call Parliament so it could investigate the matter. The testimony of the accusers was inconsistent, and Charles did not believe them. Still, in the panic that followed, hundreds were arrested and imprisoned, and at least twenty-two innocent men were executed, while others charged with crimes had to flee the country. Charles limited his involvement in the investigation and prosecutions, because he did not want to do anything that might cause another civil war. Fortunately for him, nobody wanted a repeat of the turmoil that shook England in the 1640s.

You can say the Popish Plot destabilized the reign of James II before it began. Now enough people were afraid of the prospect of an absolute, Catholic monarch to form England's second political party, the Whigs. The Whig platform promised both limited government and toleration of all Christians except Catholics, who were considered foreign agents. The king thought he could restrict the Whigs by allowing Parliament to meet as little as possible, but their power and influence continued to grow anyway.

The Whigs saw their worst fears realized when the next king, James II, announced that he would make England a Catholic country and run the government without Parliament's interference. However, James was in poor health, and the only children of his that lived to grow up were two daughters, both Protestant. One of them, Mary, was married to the current Dutch leader, William of Orange; the other, Anne, was married to Prince George of Denmark; either one of those husbands would be an acceptable ruler after James was gone. Thus, both Whigs and Tories figured that the reigns of James and the Catholic Church would be short.

That logic failed on June 10, 1688, when James became father to a son. The unthinkable had happened--England had a hereditary Catholic ruler! Protestant England united against this threat, and invited William of Orange to become the next king of England. William accepted, and when he arrived, the king's army and government deserted him, forcing James to flee to France. Englishmen called this event the Glorious Revolution, because they won it without firing a shot. Thus, Protestantism was saved in both England and England's North American colonies.

However, the revolution wasn't "glorious" or bloodless in Ireland. Because they were mostly Catholic, the Irish had always preferred the Stuarts, so in 1689 James II sailed to Ireland, bringing with him French money and soldiers. After going to Dublin, where he was hailed as king by an Irish parliament, James marched on the Protestant stronghold of Londonderry in the north, which had sworn allegiance to William and Mary. The city was besieged for fifteen weeks, but the invaders were not equipped to take it; for much of the time they only had one working cannon! Then in 1690 William led a relieving force to Ireland, and won a battle at the River Boyne, causing James to return to France. The rest of 1690 and 1691 were spent in a mopping up operation, before William of Orange could declare that the Irish portion of his kingdom had been pacified. Because of King William's success, Irish Protestants adopted the color orange as their symbol, and have called themselves "Orangemen" ever since.

Sweden at its Peak

Gustavus Adolphus left specific orders for his court to raise Christina as a boy. Consequently, after she grew up, the new queen preferred to wear men's clothing. Because she also began attending council meetings at the age of 14, one observer wrote: "She was naught of a child except in age and naught of a woman except in sex."

Rather than simply accept her Lutheran faith, Christina constantly questioned it, and eventually converted to Catholicism. This was against Swedish law, so she had to abdicate in 1654. She was succeeded by a cousin, Charles X. Christina doesn't seem to have missed the crown much; she spent the rest of her life in Italy as a swashbuckling adventurer, in the manner of the Three Musketeers and Cyrano de Bergerac.

Eastern Europe had been quiet for most of the Thirty Years War. That ended in 1648, when the Cossacks of the Dnieper River declared their independence from Poland. The Poles won the first battles, until the Cossack leader, Bogdan Khmelnitsky, transferred his allegiance to Russia, thereby bringing the Russians into the conflict (1654). The Russian Tsar Alexis invaded with more than 100,000 men, overwhelmed the smaller Polish armies, and occupied much of Lithuania; in 1655 Alexis proclaimed himself the grand duke of Lithuania, reviving a title that nobody had held for nearly a century. The same year saw Sweden declare war on Poland, for Charles X was tired of hearing the Polish king, John II Casimir, tell everyone that he was the rightful heir to the Swedish throne. Two Swedish armies quickly overran Poland; one army took Warsaw and Cracow, while the other occupied the rest of Lithuania. In response, Alexis attacked Sweden in 1656, but failed to make any headway.

Next came one of those frequent political rearrangements that characterized Europe in this era. Frederick William, the elector of Brandenburg, signed an alliance with Sweden in January 1656, but broke it in the fall of 1657, when the Polish king promised to let him have East Prussia with no strings attached and Denmark, encouraged by Austria and Holland, entered the war on Poland's side. Pulling out of Poland, Charles took the fight to Denmark; the winter of 1657-58 froze the sea around Denmark, allowing Charles to invade the island of Fyn after he occupied Jutland. Because Copenhagen was now unprotected and threatened, the Danes sued for peace. The Treaty of Roskilde gave the Swedes all Danish provinces in modern Sweden, the island of Bornholm, and central Norway (the area around Trondheim).

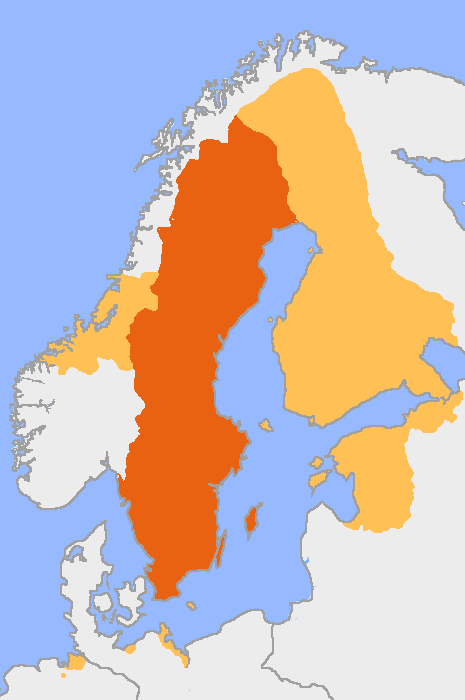

Sweden, in 1658 (light and dark orange) and today (dark orange).

Charles wanted more than this, but the Danes were unwilling to give it, so he renewed the war six months later, in August 1658. What he didn't realize was that Sweden had now reached its limits. Fifty years of aggressive behavior had made enemies of almost everybody, and now those enemies were united against further Swedish expansion. Charles didn't have to worry about most of them; the Danes and Poles needed to recover from the devastations they had suffered, the Austrians were too far away, and the Russians were still in the Middle Ages. On the other hand, the Netherlands and Brandenburg could be dangerous. Sure enough, the Dutch fleet transported an army of Danes and Brandenburgers to Copenhagen, allowing the Danish capital to successfully defend itself. Nothing else went right for the Swedes after that; the Poles drove them out of Schleswig-Holstein, a Danish-Norwegian army recovered Trondheim, and at the battle of Nyborg (November 1659), the Danes captured Sweden's best troops. Then Charles died suddenly, while trying to raise the funds for a new campaign. His son Charles XI was only four years old, so a regency government took charge and immediately made peace. The 1660 Treaty of Oliva settled most of the sources of conflict in the Baltic: the Polish and Swedish kings gave up their claims to each other's land and throne, while Swedish rule over Livonia and Brandenburg's rule over East Prussia were officially confirmed. The Swedes had to return Bornholm and Trondheim, but French diplomats at the conference made sure their old ally didn't lose anything else.

Sweden calmed down until Charles XI came of age, but Poland and Russia continued to fight for a few more years. The Poles drove the Russians out of Lithuania and Ukraine in a series of battles, until a revolt from a local noble (Lubomirski's Rebellion) disrupted the Polish government. The result was that in 1667 Russia was able to impose a favorable peace treaty that gave the Russians nearly everything east of the Dnieper River, and the cities of Smolensk and Kiev west of it. Kiev was supposed to go back to Poland after a "temporary occupation" of two years, but the Russians amended the treaty, giving back a strip of border territory instead of their ancient capital, so Kiev has been under Russian rule for most of the time since.

The Sun King

The Treaty of Westphalia did not end the war between Spain and France, and in 1648 it looked so bad for Spain that many expected France to take Belgium and Burgundy next. It didn't happen, though, because a revolt broke out unexpectly in France. The Parlement of Paris (the chief judicial body in France until the late 1780s) was opposed to the heavy taxation policies of the king's chief minister, Cardinal Jules Cardinal Mazarin,(8) and soon demanded other political reforms, intending to stop the work Sully, Richelieu and Mazarin had done over the past fifty years to centralize the government under the crown. Mazarin had to let them have their way at first, until the Treaty of Westphalia released enough royal troops; then he arrested them. However, plenty of other Parisians disliked Mazarin, so they rose up, blockaded the streets, and secured the release of those unruly Parlement members, now known as the Fronde (meaning team or political faction). A royal blockade of Paris failed in 1649, so the government promised amnesty and made concessions.

Normally that would have made for a happy ending, but now Louis II, Prince de Condé, the hero of Rocroi and Lens, switched sides because he had led the royalist forces in 1649 and not received a sufficient reward for his service. The government arrested him, but then released him after a series of provinical uprisings, and he escaped to Spain. A second Fronde, that of the princes, formed to back Condé, and in 1652 he led a mercenary army to occupy Paris, with Turenne, the other French hero of the Thirty Years War, opposing him. However, that was the high-water mark of the rebellion. The aristocrats, as always, didn't want to promote anybody's interests but their own, and the Parisian bourgeoisie ("city-dwellers") soon decided that royal autocracy was better than feudal anarchy. Before 1652 was over, Condé fled to Belgium, and the crown returned to Paris, followed the king's ministers a year later.

Once the War of the Fronde was over, France was able to take care of business with Spain; the key battle took place in 1658, when Turenne captured Dunkirk. Still, the French required some help from the English navy to win, and when the treaty ending the war was signed in 1659, Spain got off easier than expected; she lost Artois in the north and Roussillon in the south, but got to keep the rest of Belgium and Burgundy, and Catalonia was returned. Thus the Franco-Spanish frontier returned to its natural geographic line, the Pyrenees mts.(9)

Meanwhile, England was trying to find a middle ground between anarchy and absolutism, and it was not yet clear that it would succeed. A perceptive Englishman named James Harrington warned his countrymen that taking too long to find a solution could spell trouble, if a nation on the Continent worked it out first:

"Look you to it, where there is tumbling and tossing upon the bed of sickness, it must end in death, or recovery . . . If France, Italy and Spain were not all sick, all corrupted together, there would bee none of them so, for the sick would not be able to withstand the sound, nor the sound to preserve their health without curing the sick. The first of these nations (which . . . will in my minde bee France) that recovers the health of ancient Prudence, shall assuredly govern the world . . . I do not speak at randome."

Harrington was remarkably accurate; recovery for the French began in 1661, when Cardinal Mazarin died and Louis XIV began to rule on his own.(10) The recently concluded troubles put both Louis and his subjects in the mood for absolute monarchy. His efficient finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, conducted a drastic overhaul of the government, commerce and industry to make them more productive, and Louis used the new revenue for the glorification of himself, his court and his country--in that particular order.(11) To start with, he packed the government with yes-men. In the past, major posts had been staffed by nobles who came to see these jobs as theirs by hereditary right, whether or not they were loyal to the king. Now when they had their first meeting with the king (on March 9, 1661), the record declared that the king "assembled all those whom he customarily called--and dismissed them most civilly with the statement that, when he had need of their good advice, he would call them." After that he hardly called them at all; in their place he appointed advisors from middle-class backgrounds, who had no power except that which the king gave them. These were loyal because they knew that the privileges the king gave to them could just as easily be taken away.

The activities of the central government also increased dramatically. Previously many of the duties of government--like administering justice, maintaining order and collecting taxes--were not handled by the king, but by local nobles, guilds, or minor law courts. In fact, as recently as under Henry IV, the central bureaucracy was so small that it often went with the king on his travels. Now Louis increased the number of public servants at his court from 600 to 10,000. In addition a new class of royal agents, called intendants, traveled all over France, gathering information for the king and making sure his decrees were enforced. These eyes, ears and hands of the king brought a new kind of order to France.

Louis XIV.

To get away from Parisians who expressed their political opinions too loudly, the court moved to Versailles, a small castle twelve miles west of Paris which Louis XIII had built as a retreat. A vast new building program commenced and went on for the rest of the king's long reign, eventually involving as many as 30,000 laborers at a time. The palace they produced was the grandest in Europe; just providing water for the garden's 1,400 fountains was the engineering marvel of the century.(12) The industries involved in the creation of luxuries (sculpture, ceramics, painting, elegant printing, furniture manufacturing, fine cooking and wines, wood, metal and leather work) flourished. All this went to serve a strange race of "gentlemen" who wore powdered wigs, outfits made of silk and lace, high red heels and amazing canes; the women had costumes that were even less practical, with their towering hairdos and elaborate dresses made of silk and satin on a wire framework.

Here the "Sun King" moved like the star in a never-ending glorious play. Even the rising and setting of the sun was surrounded by rigid etiquette; to witness the king getting up or going to bed was viewed as a great privilege, and someone's career could be made or broken by the king's personal whim at such a time. Late in his reign all this publicity and ritual got to be too much for even the king, so he built a little palace in the gardens of the big one, the Trianon--a hideaway from the grandeur that he had created. Humorist Will Cuppy once wrote that if you find the social life of today rather demanding, at least you don't have to leave home at 7:30 AM to help Louis XIV put on his pants.

The pomp of Versailles was not simply egotism carried to extremes; it was the king's policy for keeping peace at home. His reign had begun with turbulence, and that stamped into his young impressionable mind a burning desire to make sure that nothing ever threatened the crown again. Thus he created a court that dazzled the nobility, forced them to stay around him (cut off from their estates and most of their income), and encouraged them to outdo one another in extravagance; the end result of all this was to impoverish them and make them dependent on the king's favor. And woe to the noble who was not present when the royal eye scanned the court; if the king casually remarked about such an absentee, "We have not seen him," it meant the end of a courtier's career and social life. In all this Louis succeeded. Where the king was, France was; where he was not, there could only be ruin and oblivion.

Actually life in Versailles left much to be desired, because the palace was designed for show rather than comfort. The courtiers and servants were crowded into tiny, dark, unventilated rooms, and they had to walk through miles of corridors to do a typical day's work; the kitchens were so far from the halls of state that the king's meals usually arrived on his table cold, though 498 servants were employed in preparing them. Plumbing and privies were inadequate and inconvenient; even the most fastidious resorted to urinating on the stairs. Personal cleanliness was abysmal, and since hardly anybody bathed in those days, men and women doused themselves with perfume.(13) Boredom led many to indulge in every kind of vice, like intrigue, gambling and sexual promiscuity. Men of high rank plotted to get their daughters, nieces, and even their wives into the royal bed, for the king showered all kinds of gifts and prestige on the families of his mistresses. Those who had only sons sought similar favors from the king's homosexual brother, Philippe d'Orléans.

Versailles came with a heavy price tag. It was said that out of every ten francs raised in taxes by the French government, six went to Versailles. The French were making the same mistake that the Spaniards had made in the previous century: they spent most of their wealth, instead of investing it. And since two of the three "estates" of France--the nobility and the clergy--could pass laws making them exempt from most of the taxes, the commoners were stuck with the bill. The country at large was so impoverished that France did not recover during the reigns of Louis XV and XVI, and this helped to pave the way for the French Revolution. Even while Louis XIV was alive the need for belt-tightening became apparent. For example, many districts were left high and dry because there wasn't enough water to supply both Paris and the king's fountains, and because Paris was home to the king's bankers, who were no longer willing to lend him money without hesitation, the Sun King dropped the hint of a compromise to one of his ministers. After that, Louis XIV strolled in his gardens to view the fountains only at a regular hour; the engineers opened the jets just before the king came within view of them, and shut them off right after the royal presence passed. Louis knew better than to change his schedule, or to turn around for another glance.(14)

Louis also caused an unnecessary amount of trouble in religious affairs. Since Protestants by nature tend to question authority, he tried to mend relations with the Papacy, which had been hostile to France on account of the Thirty Years War. In 1685 he revoked the Edict of Nantes, and thousands of Huguenots fled the country to escape a new round of persecution, taking arts and industries with them. (e.g., the English silk industry was founded by French Protestants) Those who chose to stay were ordered to give their children a Catholic education or none at all. They gave it, no doubt with a sneer and an air of sarcasm that destroyed all faith in it. Consequently France became the first nation of non-practicing Catholics. The next generation produced that supreme mocker of Christianity, Voltaire (1694-1778), who lived in an age when all Frenchmen conformed to the Roman Church and hardly anyone believed in it.

Abroad, Louis faced a political situation that could hardly have been better. France was growing in wealth and strength; Spain was not; the Dutch were ready to discuss a partition of Belgium. However, this was not Louis' way--no one could share his glory--so in 1667 and 1668 he sent invading armies to capture all of Belgium for himself. The Dutch forced a truce with an ultimatum that had to be taken seriously because it was backed by England and Sweden. Louis soon broke up this "triple alliance" by buying out the Swedes and the English. Then he launched his army down the Rhine and raced for Amsterdam (1672). The French army looked overwhelming, but it had to withdraw when the Dutch flooded the country. Louis never campaigned in person again, and the only really lasting result of the invasion was that the Dutch entrusted their government to William III of Orange, a man who dedicated himself to thwarting Louis. Moreover, the English, whose Protestant bias in favor of the Dutch was usually balanced by trade rivalry, came to agree that stopping France was a matter of utmost importance. Louis could buy the English king but not the English people, and soon Parliament renewed good relations with the Dutch (1674). In the same year both Austria and Brandenburg sent troops to fight on the Dutch side. Louis retaliated by setting Sweden against Brandenburg and won more often than not on the battlefield in the Low Countries. At the truce of 1678-9 he got all of Spanish Burgundy, a French protectorate over Lorraine and a bridgehead across the Rhine. His diplomatic position was strong enough to make Brandenburg disgorge most of its Pomeranian conquests (the Swedish attack there had misfired badly).

Brandenburg's involvement showed how far it had come since the Thirty Years War. It had been a minor participant previously, and did not show much promise of ever becoming a major power. It was a small realm, divided into several pieces, with a sparse population and no important natural resources (its capital, Berlin, was built in a swamp). However, under Frederick William (1640-88), the "Great Elector," Brandenburg was transformed. Whereas most kings build an army to serve the state, Frederick William built his state to serve the army, making the army the most important branch of government. By 1678 the army numbered 45,000 men, and the state had a splendid civil administration. To bring in revenue, he got involved in the wars of Louis XIV, selling his services to first Louis, then his opponents. Thus Brandenburg, soon to be renamed Prussia under Frederick William's son (Frederick III), rose to challenge Austria's supremacy over the Holy Roman Empire and became one of the most important states of Europe.