| The Xenophile Historian |

A History of Africa

Chapter 2: VALLEY OF THE PHARAOHS, PART I

Egypt, 2781 to 664 B.C.

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| The First Intermediate Period | |

| The Middle Kingdom | |

| The Second Intermediate Period | |

| The Rise of the New Kingdom |

Part III

| Thutmose the Trendsetter | |

| The First Feminist | |

| Imperial Egypt | |

| The Amarna Revolution |

Part IV

| The Ramessid Age Begins | |

| Ramses the Great, the Ultimate Pharaoh | |

| The Latter Ramessids | |

| The Third Intermediate Period |

The Gift of the Nile

Egypt is truly "the gift of the Nile," as the ancient Greek historian Herodotus observed. Today, most of Egypt's population lives in the Nile Valley. If the Nile wasn't there, Egypt would look a lot like Libya, a country that is virtually all desert. The Nile is one of the longest rivers in the world, and it flows differently from other rivers. First, as we noted in Chapter 1, it flows from south to north. Because the prevailing winds in that region blow in the opposite direction, from north to south, transportation was easy. To go north on the Nile, all you have to do is let the current carry your boat downstream, and to go south, you can raise a sail and let the wind blow your boat the other way. This meant that instead of having the first cities bunch up near the mouth of the river, as they did in Mesopotamia, the population spread out fairly evenly from the Mediterranean to the first cataract. It also made for rapid growth; in the third and second millennia B.C. Egypt was the most densely populated country in the world.(1)

A photo of present-day Egypt, taken by satellite. Can you believe 120 million people live in the green part?

Second, the Nile begins as two major rivers. These are the White Nile, which flows from Lake Victoria in central Africa, and the Blue Nile, which originates at Lake Tana in Ethiopia. The White Nile is the longer of the two, but 80 percent of the water comes from the Blue Nile. The White and Blue Niles join at modern Khartoum, in Sudan, forming one great river that continues north to the Mediterranean Sea. Nearly 200 miles past Khartoum, the Atbara River, also called the Black Nile, joins with the main Nile, and then there are no more tributaries for the last 1,500 miles of the river's journey. From here onwards the Nile is a canal flowing through desert terrain, a fertile oasis cut out of a limestone plateau. In the land of Nubia, between Khartoum and Aswan, a series of six rapids called cataracts interrupt the flow of the Nile, so traditionally the northernmost (first) cataract was seen as the southern border of Egypt.

Nubia is a territory rich in gold and iron, and it connected Egypt with sub-Saharan Africa, but life there has always been tougher than in Egypt, so for most of history Nubia has lived in the shadow of its northern neighbor. The only area suitable for large-scale farming is the Dongola Reach, the S-curve between the third and fourth cataracts; elsewhere the area that can be cultivated is very narrow, with the desert beginning as close as a hundred yards from the riverbanks. As a result, this land could not support a large population, and it was usually behind Egypt where technological progress was concerned.

Along the last 750 miles of the river, from the first cataract to the Mediterranean, irrigation allowed agriculture in an area much wider than in Nubia, a zone two to thirty miles wide until the river got to present-day Cairo, and then the arable zone fanned out across the entire area of the Nile delta.

The last special feature of the Nile to be aware of is that it floods almost every year, and unlike the unpredictable floods of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in Mesopotamia, this flood rose and fell with unusual precision. Monsoon rains from the Indian Ocean fall on the Blue Nile and Black Nile from May to August, causing the water levels on those rivers to rise. The flood reached Egypt in late July, and crested in September; by the end of October the river was again contained by its banks. The Egyptians learned that the late summer floods were a blessing, because the Blue Nile also gave silt from the Ethiopian highlands and made the soil fertile enough to grow next year's plantings.(2)

Ancient Egyptian astronomers learned that the flood began in Egypt around the day of the year when the sun rose at the same time as Sirius, the brightest star of the night sky. They called this star SOPT or Sothis, and when astonomers first saw it at dawn, they alerted the rest of Egypt, so that the peasants living on the floodplain could head for the hills. In ancient times this critical date was July 19 on the calendar of Western nations; when those nations switched from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, the date became August 1. Appropriately, this also became the date when the Egyptian calendar began its year. So if you are reading this on or near August 1, Happy Egyptian New Year!

The Catfish King

Because it was so easy to travel around in Egypt, as mentioned above, Egypt would unite politically, long before any other nation did. We covered the first steps in the unification process in Chapter 1, as the first communities in the Nile valley became city-states, and then they came together to form two larger states: Lower (northern) Egypt in the Nile delta, and Upper (southern) Egypt along the river's main channel.(3) Since those distant times, the dense, continuous population of Lower Egypt has grown crops above the cities and battlefield(s) that must have been the scene of Egypt's first showdown. Archaeologists excavating the site of Buto, the capital of Lower Egypt, have found that in the early third millennium B.C., southern-style artifacts, especially pottery, replaced locally-made ones, and this is seen as evidence that Egypt was united when the south conquered the north, just like the Egyptians told us.

We also noted in Chapter 1 that like the cities of Mesopotamia, each prehistoric Egyptian city-state worshipped one or more gods, and the local chiefs kept their position by claiming they were in contact with those gods, and sometimes got mystical powers from them. For example, the god of the village of Naqada was Set, whom they portrayed as a fierce, long-snouted beast with square ears or horns(4), while the chieftain of Hierakonpolis claimed a falcon named Horus for his god. Abydos worshiped Osiris, a nature deity in human form who caused the ebb and flow of the Nile. These chiefs went further than their Mesopotamian counterparts, though; not content to be just a high priest for the god, they called themselves living gods. Unification brought worshipers of the different gods together, and over time they put together an elaborate mythology to explain how they were related.

The most important Egyptian myth focused on the power struggle between Osiris, Set and Horus. According to this myth Osiris was the original ruler of Egypt, until the treachery of his jealous brother Set brought him down. Set caught him by displaying a wonderfully crafted wooden box at a banquet, and offered to give it to whomever could fit inside it. One by one the gods tried out the box, and when Osiris got in it, Set and his followers rushed up, nailed the box shut, and tossed it into the sea. The wife and sister of Osiris, Isis, went looking for the box, and she found it in Lebanon, inside a giant cedar tree that sprouted up where it had drifted ashore. Fearing that Isis would revive Osiris, Set cut the body of Osiris into fourteen pieces and scattered them across the land. Isis recovered all of them except the genitals (which a fish had eaten), patched them together, and resurrected her husband, who then retired from this world to become the lord of the afterlife. The priesthood used this story to teach that Osiris was the first mummy, and that every mummified Egyptian could become like Osiris, capable of resurrection from the dead and enjoying a blessed eternal life.

Despite Osiris' missing piece, he was able to have a son before he left the world for the last time. This was Horus, who challenged Set for rulership over Egypt when he grew up. They met in a great battle, in which Horus lost an eye while Set was castrated. The gods held a meeting afterwards, and they declared Horus the winner, because Set was no longer fit to rule if he could not have children to rule after him. They exiled Set to Asia, and afterwards the Egyptian name for Asians was Setyu, because they expected them to be worshipers of Set. At home Horus became king of Egypt; each king(5) afterwards called himself the god Horus in human form, and expected to become a part of Osiris when he died.

|

|

|

|

|

Historians who came later on, like Herodotus and Manetho (see below), claimed that the name of the first pharaoh was Menes (Min or Mena in some texts). They credit Menes with uniting Egypt as one state, and founding its old capital, Memphis. However, we now believe these were the accomplishments of two kings, Narmer and Hor-Aha. The first started out as the king of Upper Egypt, and he marched into the Nile delta and conquered Lower Egypt, establishing united Egypt's first (I) dynasty. The hieroglyphs used to write his name are a serekh or rectangle, with a catfish and a chisel inside it. The ancient Egyptian words for "catfish" and "chisel" are Na'r and Mer respectively, so we call this king Narmer.

The most important artifact from archaic Egypt is the Narmer Palette, which is full of symbols showing the unification of the Nile valley. On the front side (right), we see King Narmer wearing the crown of Upper Egypt, using a mace to finish off an opponent named Wash (the king of Lower Egypt?). For thousands of years to come, the pharaohs would portray themselves in very similar poses to commemorate military victories. On the back side (left), we see Narmer with his retainers, wearing the crown of Lower Egypt and inspecting the bodies of ten decapitated enemies. The basin underneath this picture, formed by the long necks of two mythical animals, was used to grind makeup, especially eye shadow.

To help unify the land, Narmer married a Lower Egyptian princess named Neithhotep ("Neith is Content"). However, he continued to rule all of Egypt from the south, either at Abydos or at Thinis. Manetho said the rest of his reign was successful, and it appears he kept busy by leading his soldiers on raids, and capturing loot from neighboring lands. These raids went into the surrounding deserts, the Sinai peninsula, and possibly even Canaan. At this early date, when it came to war, the Egyptians usually won, because none of their opponents were as big, or as well organized. But Narmer's reign may have ended with the first recorded hunting accident; Manetho also claimed that he died when a hippopotamus carried him off. Mind you, hippos may look cute when you see them in a zoo or circus, but in the wild they are very aggressive animals; even today, hippos kill some Africans every year (see also footnote #27). Narmer's tomb was built at Abydos, but for reasons unclear to us, his wife Neithhotep got a large tomb in an older cemetery, at Nubt/Naqada. Some Egyptologists believe she ruled briefly, about fifteen months, either between Narmer and Hor-Aha, or between Hor-Aha and the third king, Djer. If either regency happened, it means Neithhotep was the first female pharaoh, rather than Merneith or Hatshepsut.

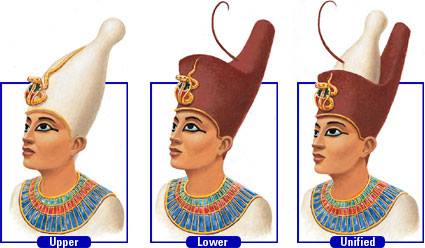

Narmer and his successors encouraged unity by adopting several Lower Egyptian symbols (the cobra, papyrus plant, and the bee) and putting them alongside Upper Egyptian counterparts (the vulture, lotus, and sut reed). Up to this point Lower Egyptian kings had worn a red scorpion-shaped crown, and Upper Egyptian monarchs had worn a white crown shaped like a bottle or bowling pin, so Menes united them to form the double crown that pharaohs commonly wore afterwards (see the above picture). From time to time, though, the pharaohs might take part in a ceremony that only involved one part of the country, and for that occasion they reverted back to wearing either the white or red crown again. Egypt never forgot that it had been two nations originally, and frequently called itself T3wy, "the Two Lands," for the rest of its ancient history.

Because we have no evidence to suggest otherwise, we believe the second king, Hor-Aha ("Horus the Fighter"), was the son of Narmer and Neithhotep. The home city of Neith, the goddess of Neithhotep, was Sais, in the western delta, so Hor-Aha built a temple to Neith there. Besides doing something nice for his mother, this move would have strengthened his control over Lower (northern) Egypt, by giving anyone at the temple a reminder of who was in charge. He also founded Shedet, a city in the Faiyum oasis (later called Crocodilopolis), and promoted the worship of the oasis god, Sobek, who is portrayed in Egyptian art as a crocodile. And he kept his soldiers busy by leading military expeditions into Nubia and Libya. But his main achievement was the founding of a more permanent capital for the country, because he felt it was time to stop treating Lower Egypt as a conquered territory. This is the city we call Memphis (see also footnote #29), and it was located at the apex of the delta, right where Upper and Lower Egypt meet. It turned out to be a superb location for a capital. Memphis was the capital of Egypt until the end of the VIII dynasty (about 2000 B.C.), and after that it was still Egypt's largest city until the founding of Alexandria, in 332 B.C. Today Cairo is built over Memphis, so archaeologists can excavate only a small part of the ancient city.

Saqqara (also spelled Sakkara), a site in the desert west of Memphis, became the cemetery for Memphis, but the kings continued to build tombs for themselves alongside those of their ancestors at Abydos, presumably to keep tradition. In the twentieth century it was believed that the oldest tombs at Saqqara also belonged to kings, but because their number exceeds the number of kings that we know of from the first two dynasties, we now believe that for the I dynasty, only officials from the court at Memphis were buried at Saqqara; the names of the earliest kings are there because they insisted on having their names carved and painted larger than the names of their ministers, even on their graves. Meanwhile at Abydos, Hor-Aha's tomb was placed next to Narmer's, and here a grim custom was introduced: also next to Hor-Aha's tomb are 35 burial pits, containing servants of the king, dwarves, women and even dogs and lions. These individuals were killed so they could serve Hor-Aha in the afterlife, and for the rest of the I dynasty, there would be a round of human sacrifices with the death of each ruler.

The Archaic or Protodynastic Era

Dynasty I

2781-2662 B.C.

Egypt was the world's foremost nation for an amazingly long time. A good case has been made for the Mesopotamian and Indus valley civilizations getting started first, but the third millennium B.C. was more than halfway over before their city-states united to form nations. Until that happened, Egypt was the only nation-state in existence, so its civilization was the most impressive. Egypt's head start on political unification, combined with the conservative rhythm of life on the Nile, convinced everyone else that it had been around forever. As a result, when outsiders managed to conquer Egypt, most of them (Hyksos, Libyans, Nubians, Assyrians and Persians) felt the need to adopt Egyptian customs, or at least respect them. Not until the arrival of a stronger culture, that of the Greeks, did Egyptian culture begin to falter, but that's a story for Chapter 4.

Another thing which made Egypt impressive was that unlike the city-states of the Middle East, it was a peaceful land. During the first two "golden ages" in Egyptian history, the Old and Middle Kingdoms, there were no invasions from outside. And at this early date, when Egyptian armies went abroad, the purpose was to raid other lands; they did not embark on wars of conquest that would consume all of the Nile valley's resources and then some. Instead, the rulers of Egypt devoted most of their resources, their wealth, and their manpower to building monuments that glorified their gods and themselves.

The history of ancient Egypt is divided into thirty dynasties, a tradition started by an Egyptian historian named Manetho, in the third century B.C. Usually a new dynasty began when the current ruling family ran out of heirs or was overthrown, and a new family took over.(6) Inbreeding may have brought down some of them, too. From a very early date they believed that the king had to have royal ancestry on both sides of his family. Occasionally, marrying foreign princesses accomplished this, but more often incest was the answer, with brothers marrying sisters regularly. If there wasn't a sister handy, the king might marry a first cousin, aunt, or even his mother (we have records of some queens outliving their husbands and being passed on to the next king)!

The first two dynasties (2822-2532 B.C., according to my chronology) are commonly called the archaic or protodynastic era, because this was the time when Egyptian culture completed its development. Very little is known about this era, because few artifacts have survived the 48 centuries between then and now. In fact, just about everything we have from before 2000 B.C. comes from the graves of Egypt.

The reason for this is that the ancient Egyptians looked upon the next life as being more important than this one, so they took special care to make sure that their tombs would last. Their houses, even royal palaces, consisted of sun-dried brick, which is practical because it hardly ever rains in Egypt, but when it did rain their buildings melted and had to be repaired or replaced. By contrast, they built most of their temples and tombs of stone, so they still stand today. Because we have learned so much of what we know about the ancient Egyptians through tomb-digging, we probably have a distorted view of what they were really like. The Egyptians were not morbid, weird people, but folks like us who saw the afterlife as being a lot like this life, only better (e.g., if you were a farmer, you would be a farmer again, but the grain would grow nine feet high with hardly any effort!). It was the Egyptians who first said at parties, "Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we may die." Look at it this way: if some archeologist comes along two thousand years from now and tries to learn about our civilization, and he has to go to our cemeteries to learn anything about us, would that give him some strange ideas about how we lived?

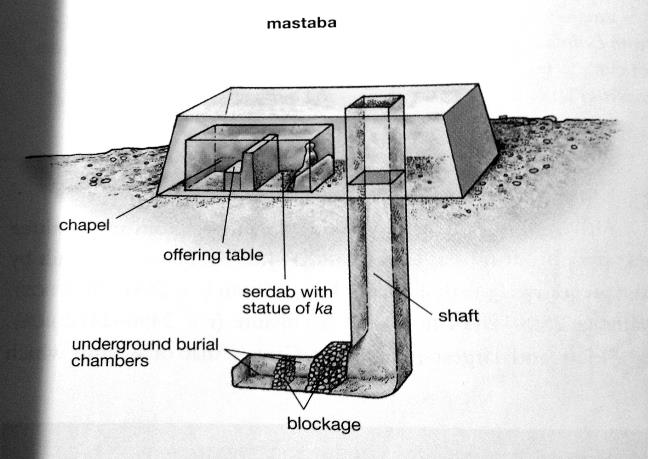

Now that the point has been made, let us go to the place where dead men do tell tales. We believe that in predynastic times, at least under the Naqada II culture, the king was put to death when he became too weak to rule. Because of the king's importance, a simple grave was not enough, so the Egyptians put the king and his belongings, plus food and drink, in one or more underground chambers, with an artificial hill of dirt piled up on the surface, and a wall around the hill. With the unification of Egypt, a one-story brick structure replaced the hill. We call this structure a mastaba (Arabic for bench), and the fanciest ones were made to look like the king's earthly house.

The layout of a typical mastaba, showing the separate shaft from the roof to the burial chamber (see below).

For the kings, boats might be buried in separate pits, to provide transportation for his journey to the next world. On the outskirts of Abydos, one mile from the royal tombs, a chapel surrounded by a wall was constructed as well. Archaeologists call this structure a funerary palace, and one is tempted to compare it with the mortuary temples built later on, but curiously, it was destroyed shortly after it was completed, instead of being allowed to stand for the ages. Either it was only meant to be used at the time of the royal funeral, or each king was required to tear down his predecessor's funerary palace before he could build his own. Next to the funerary palace, additional human sacrifices were buried; these could include relatives of the deceased king. We already noted that 35 people and pets were buried around the tomb of the early king Hor-Aha; six more were buried at his funerary palace.

For the next king, Djer (also spelled Zer), we have a rock inscription that suggests he led a military expedition into Nubia, and advanced as far as the Second Cataract. Otherwise, we know nothing about the events of his reign, though Manetho asserted that his reign was a long one (41, 57 or 62 years, depending on which translation you're reading). When Djer died, he got the most violent funeral in Egyptian history; 318 victims were buried around the tomb, and 269 at the funerary palace. A thousand years after the I dynasty, during the Middle Kingdom, the priests of Abydos examined the plundered remains of the royal tombs, and because Djer's tomb was the largest from the I dynasty, they decided this must be the tomb of Osiris; they converted the tomb into a shrine for the god of life, and the worshipers of Osiris who went there never knew that members of the first government of united Egypt had been slain, to dedicate the original structure!

Here, the British TV show Horrible Histories acted out how the retainers for Djer's burial might have been selected.

Under Djer and his successors, Egypt grew rich, and so did the kings. They commissioned artisans to make fine jewelry and works of art for them, and when they died these were buried in the tombs, since ancient Egyptians believed more than anyone else that you can take it with you. But when the contents of the tombs became valuable enough, grave robbers went to work. To protect the king and his possessions, various methods were devised to deter robbers, like filling passages with sand and rubble, false doors, traps, etc. The tomb's security was also improved by putting the body at the bottom of a vertical shaft, which had its entrance in the roof and could go down as much as a hundred feet beneath the other chambers. This led to a second problem--when separated from the drying sands and put in a dank chamber walled with brick or stone, the royal corpse rotted. By this time Egyptians had come to believe that the dead needed not only their possessions, but also their original body, in order to have immortality.

We noted in Chapter 1 that the typical predynastic burial consisted of digging a hole in the sand and placing the body in it, along with a few possessions and pots containing food. Under desert conditions the body did not decay, but simply dried out. Thus, when the Egyptians invented mummification, they were trying to duplicate with artificial preservatives what the desert had done naturally.

At first they simply wrapped the head and hands of the dead with linen bandages; this was done to several bodies in the cemetery of Hierakonpolis, before 3000 B.C. By the beginning of the I dynasty they were wrapping the entire body, and soaking the banadages in resin; this retained the original shape of the corpse, but did nothing to keep the flesh from withering away. The oldest example of this practice, a plain wooden box containing a wrapped skeleton, was found at Saqqara in 2003; this may have been a court treasurer or vizier of Hor-Aha.(7)

The royal embalmers were not content to preserve appearances. Around the beginning of the IV dynasty, they started practicing true mummification. Now before they did the familiar bandaging they dried out the corpse in natron (a form of salt, sodium carbonate to be exact), and usually removed most of the internal organs so they could be dried separately, before decay set in. What the priestly surgeons took out was preserved with natron, in four jars called canopic jars; in their place the body cavity was packed with crushed myrrh leaves or resin-soaked linen. The heart, however, was left in the mummy, because it was thought it would be needed when the dead person appeared in judgment before the god Osiris, to testify that the soul was worthy to enter into Paradise. By contrast, the same embalmers who were careful in preserving all the other parts, thought the brain was unimportant, so if they removed it, they threw it away! The whole process took about 40 days, but they prolonged it to 70 days by reciting prayers and practicing magic every step of the way.

At first mummification was so expensive that only the rich could afford it. Later, when the embalmers developed more effective techniques, they offered the old techniques at a discount, so by the time of the New Kingdom, people of ordinary means could afford a funeral that would guarantee them a chance at the afterlife. The poor could never afford even that, though, and continued to bury their dead in the sand the way their ancestors did originally. But you could say the poor had the last laugh, for robbers never bothered their final resting places.

The last step in preparing a royal mummy--

saying the appropriate prayers.

Over the course of the I and II dynasties the tombs grew more elaborate. This was especially the case at Saqqara, where mastabas started out small, but later could be up to thirty feet high, with as many as seventy rooms inside. Eventually the upper-class dead were also buried with statues, a safety measure to give the ka (soul) a backup place to stay in should the body be destroyed. Sometimes the statue went into its own room, with a slot in the wall so it could watch the priests put offerings in an adjoining chamber. The priests could be practical as well as superstitious; they often consumed the food and drink brought in with the offerings before it had a chance to spoil.

Now let's return to the narrative about Egypt's earliest kings. Djer was succeeded by Djet (Uadji in older texts), and like Djer, we know almost nothing about his reign, except that there was extensive trade with the Middle East, and Manetho mentioned a famine, the oldest on record for Egypt. Because of Djer's long reign, we think Djet was already old when the throne passed to him, so he did not rule as long (ten years has been suggested). 174 sacrificial victims were buried around his tomb. Merneith, the widow of Djet, successfully ran Egypt until their son Den grew up; she was rewarded for her service with 41 retainers buried around her tomb.

The reign of Den (also spelled Udimu) was the busiest of the I dynasty. Writing has improved to the point that we can read about several accomplishments or "firsts" that are credited to him. Of course being first at something is easy when your civilization is getting started. Those accomplishments include the following:

- First known king to be called by the title "King of Upper and Lower Egypt."

- The establishment of many customs of royalty and the court, including the first known observance of the Heb-Sed festival. This means that by now, the practice of killing an unfit king had ended.(8) Now with the Heb-Sed, the king would undergo athletic tests, to prove he was physically fit to continue ruling. Usually the Heb-Sed would take place when the king reached the thirty-year anniversary of his reign, and once every three years afterwards.

- Military campaigns against the Bedouins of the eastern desert and the Sinai peninsula.

- The first use of hieroglyphs to represent numbers.

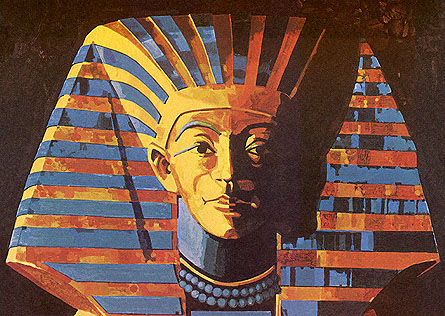

- The first artwork showing a king wearing the double crown, as well as the nemes, the headdress so often associated with Egypt.

- The first use of stone as a building material, rather than wood and bricks.

- The first recorded plague in Egypt.

Den's successor, Adjib (also spelled Anedjib or Enezib), was another ruler we know next to nothing about. His name was erased from several stone vessels, and it looks like the next king, Semerkhet, did this. Scholars see the erasures as a sign of political unrest, and that Adjib or Semerkhet, possibly both, were usurpers. Moreover, Adjib's tomb at Abydos is small, with only two rooms, and it shows signs of poor construction; this could be a sign that his reign was short, and that the king could not afford to build anything better. 64 sacrificial victims were buried around the tomb. Finally, we have pictures of Adjib's Heb-Sed festival, with the word Qesen ("calamity") written on them, but with no description of what happened; perhaps his reign ended with violence.

The bit of information we have on the next king, Semerkhet, suggests he did not fare better than Adjib. Manetho claimed that bad omens were seen during his reign, and a great calamity took place, but again, no details are given. Likewise, the Palermo Stone, a stone listing the names of the kings from the I to the V dynasty, declares that the main event during the first year of Semerkhet was the "Destruction of Egypt." This is surely an exaggeration, for the stone lists nine events for Semerkhet, one for each year of his reign, suggesting that he ruled for eight years and an unspecified number of months. Therefore whatever the calamity was, it didn't kill him, since he remained in charge for at least eight years afterwards. And Egypt wasn't destroyed; in fact, the country still exists now.

Semerkhet left a tomb at Abydos, but not at Saqqara, which could mean he did not rule long enough to build tombs in both places, or that his chief ministers, one of which would be buried in the Saqqara tomb, all outlived him. The Abydos tomb has an unusually large mastaba, at 95 x 102 feet, and the mastaba's superstructure covered all 67 of the burial pits dug for Semerkhet's servants.

We believe the eighth king, Qa'a, enjoyed a reign of 33 years, and Egypt was stable during that time. He left an elaborate tomb at Abydos, surrounded by 26 burial pits. There is another tomb with the name of Qa'a on it at Saqqara, and surrounding it are four burial pits; we don't know who got this tomb. However, when the reign of Qa'a ended, the I dynasty abruptly came to an end as well. As usual, we don't have any details on what happened. Stone and ceramic vessels have been found with the names of two rulers that cannot otherwise be placed in Egyptian chronology, "Sneferka" and "Sekhet" or "Horus Bird." Currently the most popular theory is that Qa'a outlived all his heirs, and after his death, Sneferka and Horus Bird waged a struggle for the throne.

The end of the dynasty also marked the last time human sacrifices took place with a royal funeral. The reason why this happened is a bit easier to figure out; the Egyptians have never been a bloodthirsty people. Therefore, after the II dynasty replaced the I dynasty, there were no more "satellite burials" around the tombs of the kings and queens. From now on, small statues of servants, called ushabtis, were placed in the tombs, and these were expected to magically come to life and serve the tomb's owner.

An article in the April 2005 National Geographic proposed that the servants rebelled and overthrew the I dynasty to save their skins. Because we have so little evidence to go on, we cannot say for sure if this is what happened, or if the change in custom was less dramatic. The Egyptians may have stopped burying people and animals around the mastabas because they realized that it is harder to find people willing to work for the government, if they are expected to die when the king does. Or the would-be victims may have convinced the priests that Pharaoh could wait until all his servants had died of natural causes, before they joined him in the next life.

Dynasty II

2662-2508 B.C.

Under Egypt's second ruling family, we have at least as much trouble telling the story of Egypt, as we did under the first dynasty, and it's for the same reason; we have almost nothing to go on. What we do know is that the first king of the II dynasty called himself Hotepsekhemwy, meaning, "peaceful in respect of the two powers." Obviously this wasn't his birth name, but a name he gave himself to commemorate an event; it sounds like an agreement was reached between two rival factions, either political or religious. But it doesn't tell us if Hotepsekhemwy was a new name for one of the two leaders that we think fought at the end of the I dynasty ("Sneferka" and "Horus Bird"), or if he was a third party who came along and defeated the other two. It just tells us he was the last man standing when the conflict was over.

Like the I dynasty, the II dynasty was a family that claimed their ancestors came from Thinis, a town next to Abydos in Upper Egypt. At first, Hotepsekhemwy acted like he was going to continue tradition, by overseeing the completion of Qa'a's burial at Abydos. But he didn't believe the same should be done for himself. Instead, he was buried at Saqqara, not at Abydos. This started a new tradition; now Saqqara became the cemetery preferred by II dynasty kings. Arround the tomb of each king, the tombs of the nobles who served him were arranged, like buildings in a city, with ghostly avenues between them. Unfortunately, the tombs at Saqqara were eventually destroyed to make room for building projects that came later on; all we have at Saqqara from the II dynasty are a few underground passages, with pots and jars bearing the names of II dynasty kings. From these we know the names of the dynasty's first three rulers: Hotepsekhemwy, Raneb, and Ninetjer. Because the tombs of these kings used to cover a large area, historians think the reigns of these kings were long and generally prosperous, until an economic disaster, possibly a famine, occurred at the end of Ninetjer's reign.

So what did the II dynasty kings do besides build tombs? For one thing, they looked for new resources, and exploited them as much as they could. As far back as the predynastic era, the Egyptians had mined gold in the eastern desert, the land between the Nile valley and the Red Sea. Well, now that copper had become another metal worth having, the Egyptians opened copper mines in the eastern desert, too. To the south, there had been an Egyptian community on Elephantine, an island in the Nile at Aswan, at least since Egypt was first united. This island was next to the First Cataract, the traditional border between Egypt and Nubia, and the expeditions that went forth to trade with the Nubians started their journeys here. Now Ninetjer opened a quarry here, to mine granite for use in building projects, and big new barges would be built to float the stones down the Nile.

After Ninetjer, the big picture becomes really murky. More kings left artifacts at Saqqara; they had names like Weneg, Sened, Nwbnefer, Neferkara, and Neferkaseker. Another king was called Hudjefa, but recently it was pointed out that this is not a proper name. In the ancient Egyptian language, "Hudjefa" meant "Erased" or "Missing"; apparently the scribes forgot this king's name, though they remembered he existed. Nothing from these kings has been found at Abydos. On the other hand, in the Abydos cemetery, the next king after Ninetjer was Sekhemib, and this ruler left nothing at Saqqara. W. Helck (Thinitenzeit, 1987, p.105) has suggested that under Ninetjer, the country's government grew so big that to administer it efficiently, he divided Egypt between two sons, crowning one in Memphis and one in Abydos. This is plausible--monarchs in other countries have made stranger arrangements for their heirs--but in a country where the natural geography encouraged unity, it seems odd, to say the least.

Next, it appears that a religious revolution took place. We saw in Chapter 1 that when hieroglyphics were developed, it became customary to put the hieroglyphs representing a king's name in a serekh-rectangle, topped by a falcon representing the god Horus. Now Sekhemib changed his name to Peribsen, and replaced the Horus-falcon in his name with the Set-animal; then, like Akhenaten would do in a later age, he erased his original name wherever it could be found, replacing it with the new name. He may have done this because the followers of Set enjoyed a major revival in the II dynasty. Or maybe the people living around Abydos and Nubt felt neglected, because the II dynasty did not give them as much attention as the I dynasty did. Either way, a faction in Upper Egypt grew in numbers and influence, until the king had to join them to keep them on his side. Meanwhile, Lower Egypt stuck with Horus; they would have seen the switch from a Horus-name to a Set-name as a radical change. And if the Osiris myth told earlier in this chapter had been written down by this time, everyone who didn't worship Set would have seen this god as a villain. Imagine in our own time, if a famous person that we all thought was a Christian suddenly announced that he or she was a Satanist; that's how most Egyptians would have felt.

How Peribsen wrote his name. From Wikimedia Commons. See also footnote #4.

Unlike the dynasty's previous kings, Sekhemib/Peribsen was buried at Abydos, in a tomb smaller than those of his predecessors. During or immediately after his reign, it looks like a civil war broke out. All of the royal monuments at Abydos, Nubt and Saqqara up to this point were damaged by fire, and this appears to have been done with official sanction, to destroy the afterlife of somebody's political opponents. We have the names for a couple of possible kings after Peribsen, but the next king we know anything about was Kha-sekhem. Under him, we see pictures of warfare for the first time since unification; his portraits show only Horus and the white crown, suggesting that both Lower Egypt and the Set faction were among his enemies. It also looks like Kha-sekhem moved his capital all the way to Hierakonpolis, in the far south. Artifacts with Kha-sekhem's name on them have only been found in the southernmost part of Egypt, so for a while that may have been the only territory he controlled; even Abydos appears to have been in rebel hands. One such object is a statue of the king which says on the base, "Northern enemies 47,209"; presumably this is a count of how many Lower Egyptians were killed, possibly with Libyan tribesmen as their allies. Incidentally, this is the oldest case we have found so far where hieroglyphics were used to write a complete sentence, showing how much writing has improved since they invented it.

Eventually Kha-sekhem prevailed over the north, and restored order. When the war ended he changed his name to Kha-sekhemwy, and wrote it with both the Horus-falcon and the Set-animal above the hieroglyphs, suggesting a compromise had been reached between the Horus and Set worshipers. In addition, he took two titles that suggested he was a peacemaker: "Arising in respect of the Two Powers," and "The Two Lords are at peace in him." A major upswing in prosperity followed, and Kha-sekhemwy left the largest mastaba of all at Abydos, a 230 x 59 foot-long building.

Like Narmer, Kha-sekhemwy promoted peace by marrying a northern princess, Nemathap, and she was later worshiped as the mother of the next two kings, Sanakht (also spelled Nebka) and Djoser (also spelled Zoser). She must have been a woman with a strong personality, for her title was "She who says something and it is done (for her) immediately." She also may have acted as regent after Kha-sekhemwy's death; we don't think Kha-sekhemwy lived until Sanakht and Djoser grew up, anyway. Finally, we have a picture of Nemathap kneeling at the feet of Djoser, after the latter became king. For these reasons, a mortuary cult venerating Nemathap sprang up during the III dynasty (2532-2477 B.C.), and Egyptian scribes declared Nemathap the founder of the III dynasty, though as far as we can tell, there wasn't any family break between Kha-sekhemwy and Nemathap's kids. Everything was now in place for the reunited Two Lands to begin Egypt's first golden age, the Old Kingdom, the glorious age of the pyramid builders.

Dynasty III

2508-2434 B.C.

To us, Sanakht, the king who officially starts the III dynasty, is a man of mystery. The lists we have of the pharaohs, from Manetho's work to the list on the wall of the temple of Osiris at Abydos, all mention Sanakht at the beginning of the III dynasty, but otherwise we aren't sure what to do with him. Because his brother Djoser almost singlehandedly transformed Egypt from a good nation into a great one, today's historians want to put Djoser at the head of both the III dynasty and the Old Kingdom. Therefore Sanakht is relegated to the second, third or even fourth king of the dynasty. However, we need to keep in mind that if these two kings were really brothers, we can't have more than a few years between them, in whatever chronology we use. Myself, I'm more comfortable keeping Sanakht at the beginning of the dynasty's list, because the tomb we have tentatively identified with Sanakht is a mastaba at Beit Khallaf, a cemetery located twelve miles downstream from the Abydos cemetery. Having him buried in a mastaba near Abydos makes sense if he lived and ruled before Djoser broke royal burial traditions. Let the record show that history does not always let us put people and events into neat groups or packages.

We do not know much about Sanakht, for the same reason that we do not know much about the I and II dynasty kings -- only a few artifacts can be associated with him. Excavated in 1901 A.D., the tomb assigned to Sanakht contained an unusually large skeleton; the owner stood 6 feet, 1 and 1/2 inches tall when he was alive. The people of that time had an average height that was almost a whole foot shorter, so they must have seen him as a giant.

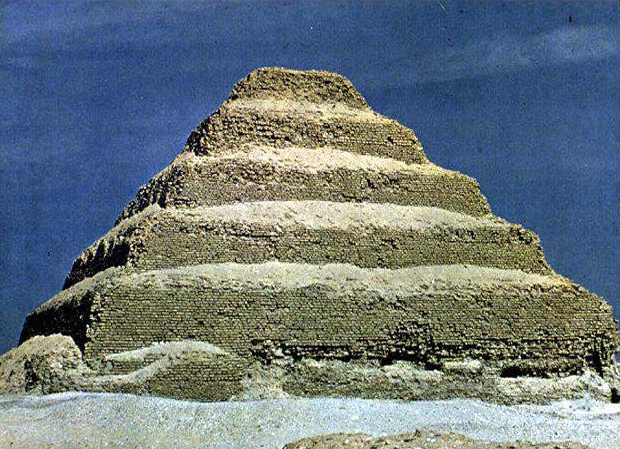

Now we come to the stars of the dynasty, Djoser and Imhotep! Under them, the royal burial place made the most dramatic transformation in Egyptian history. This happened because by the early III dynasty, the nobles had gotten so rich that they were building mastabas for themselves, too. Well, Djoser was up to meeting this challenge, because his vizier was a genius named Imhotep, a Renaissance man who was also a priest, a sculptor, a scribe, a scientist, an engineer, and a physician.(9) Like any good pharaoh, Djoser got work started on his grave as soon as possible, preferably once the festivities surrounding his coronation were finished. Thus, Djoser commissioned Imhotep to build him a majestic tomb--an eternal house that would reach to the heavens, and stand out against the tombs of the nobles around it.

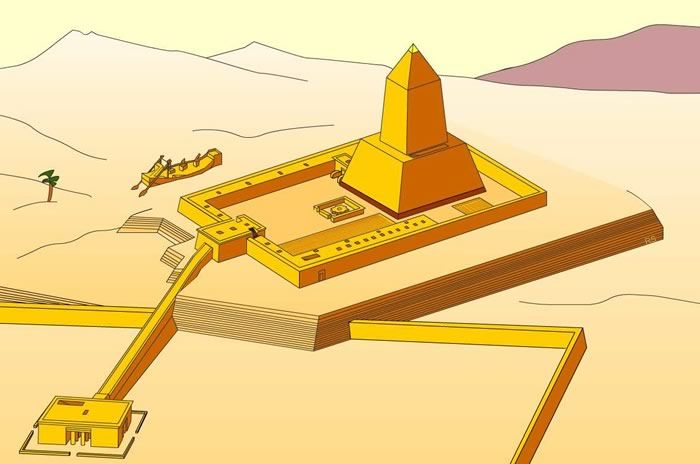

The first way this mausoleum stood out was that it was made of stone, not bricks; this would be the oldest freestanding stone structure in the world. From Aswan, at the southern border of the country, Imhotep fetched granite, basalt and quartz; for an outer coating he selected fine, white limestone, which came from the hills of Tura, just across the Nile from Saqqara. Peasants were conscripted in droves to carve the stones into blocks, transport them on barges to Saqqara, and drag them into place on wooden rollers or sleds. At first they just built an oversized mastaba, but over time Imhotep and Djoser grew more ambitious, and they changed the architectural design more than once. In the end the structure they built was six mastabas, stacked one on top of another, each one smaller than the ones below it. This was the first pyramid, a ziggurat-like tower more than 200 feet tall. Today we call it the Step Pyramid; the shape was meant to look like a "Stairway to Heaven." Around it was built a mile-long wall, enclosing an enormous courtyard. Next to the pyramid was a small rectangular building, which we believe was a chapel. In the chapel was a painted limestone statue of the king, the oldest lifesize statue ever found in Egypt. Under the pyramid was the king's burial chamber and a maze of galleries crammed with more than 40,000 stone jars, vases and cups holding funerary offerings.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser.

To those of you familiar with the treasures of Tutankhamen, the stone vessels may not sound like much, but to archaic Egyptians they represented real wealth. Each jar took weeks of labor from a skilled craftsman, to shape and decorate, so Djoser in effect had himself buried with a sizeable chunk of Egypt's gross domestic product. And not all of the jars were made during Zoser's reign; some were heirlooms from the I and II dynasties, bearing the names of earlier kings. A few even had the catfish hieroglyph of Narmer, the I dynasty's legendary founder; we don't know how Djoser got hold of these. Finally, we should remember that the pyramid was built at Saqqara; Djoser did not see the need to build his tomb at Abydos. For the rest of the Old Kingdom, all royal tombs would be built in the vicinity of Memphis.

Djoser may have considered his pyramid a great success, since it was the most impressive building Egypt had seen up to that time, and people have been talking about both it and him ever since. But such a monument also comes with a serious liability. The pyramid's main function was to protect the king's body and a large portion of his personal possessions until the end of the world, but instead it gave the grave such an obvious marker that nobody could miss it; all the tomb robbers had to do was find out where the entrance was concealed. As one might expect, the typical pyramid was robbed of all its contents--the royal mummy was usually taken out of its coffin and thrown away--but the Egyptians continued to build pyramids for nearly a millennium before they realized there must be a better way to bury their kings and queens.

The next three kings after Djoser -- Sekhemkhet, Khaba and Huni -- all tried to build pyramids of their own, but none succeeded in completing one, presumably because their reigns were too short, and after they died, their successors did not want to finish what another king had started. The most interesting of these unfinished monuments came from Sekhemkhet, who built his pyramid next to Djoser's, and tried to outdo him by making it with seven steps, not six. Imhotep's name appears on a wall surrounding this pyramid, a hint that the great architect outlived his first master and served Sekhemkhet, too. However, Sekhemkhet died after a reign of six years, and only one step of his pyramid had been completed by then. Afterwards, the pyramid was covered by sand, and forgotten until it was rediscovered in 1951 A.D.. The archaeologist who excavated the pyramid thought this was another intact burial, like the more famous one of Tutankhamen. He did not find rooms full of treasures, but he was encouraged to find several pieces of gold jewelry, a sealed alabaster sarcophagus, and the remains of a funeral bouquet on top of the sarcophagus. Instead of the lid being on top, as was usually the case, the sarcophagus had a sliding door on one end, but when it was opened, the sarcophagus turned out to be empty. Why wasn't Sekhemkhet in there? It may be that Sekhemkhet only wanted to build a cenotaph (false tomb) for himself at Saqqara. Or perhaps the tomb was robbed anyway, and the people in charge of building and guarding the place resealed the sarcophagus, to give the illusion that the royal mummy was still in it (see Hetepheres I below).

As for Imhotep, what kind of tomb did he get? Presumably it was one of the III dynasty mastabas, next to the two pyramids he worked on. Unfortunately too much time has passed to properly indentify which tomb is his. First, all of these mastabas have been looted by robbers over the ages. Some of them were reused for newer burials, and all were affected by later construction projects nearby. Therefore, Imhotep will just have to live on, in the memory of those who have heard of him (see the previous footnote). Still, can you say that about anyone else who lived 4,500 years ago, especially someone who wasn't a king?

There isn't much to say about the next king, Khaba. He may have been an unpopular ruler, since after his reign an effort was made to erase his name from the monuments it was written or carved on. Perhaps he was a usurper, if he wasn't just incompetent. For his pyramid, it looke like he did not want to compete with his predecessors, because he opted for a smaller pyramid than those of Djoser and Sekhemkhet, and he built it at a different site, at Zawyet el-Aryan. Today the pyramid is in such bad shape that we aren't sure what happened to it. Did Khaba fail to complete it? Or did he complete it, only to have someone else try to take it apart later? We will see that after the pyramids were built, the outer layers of some of them were removed, when someone had a building project, like the city of Cairo in the tenth century A.D. (see Chapter 5), and it was easier to take the building stones they needed off the pyramids, than to carve new stones at a quarry.

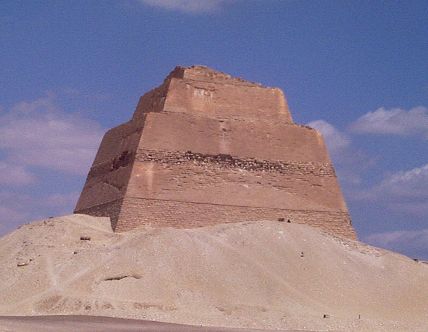

The last king of the dynasty, Huni, ruled for around 24 years, but even that wasn't enough time to finish his pyramid. Inscriptions from the reign of Djoser mention someone named Huni at Djoser's court, so if this is the same person, he was a senior citizen by the time he got to rule. Back in the twentieth century, scholars believed that the unfinished pyramid at Meidum was Huni's project. However, his name was never found on or near the pyramid, but the name of the next king, Snefru, was there. Some have suggested that both Huni and Snefru worked on this pyramid, or even that Khaba and Huni could have been the same person, because if this isn't Huni's tomb, we don't know where it was. Huni also built seven small step pyramids in other parts of the Nile valley. These weren't tombs, but we don't know for sure what they were for; our best guess is that they were places to collect offerings for Huni's cult of personality, after his death. Later in this chapter, we will see the kings build mortuary temples near their tombs for the same purpose.

Dynasty IV

2434-2364 B.C.

The next king who tried building large and succeeded was Snefru, the first king of the IV dynasty (2477-2367 B.C.). Snefru's wife, Hetepheres I, was a daughter of Huni, and because Snefru was Huni's son-in-law, rather than a son, his rise to the throne marks a break between the III and IV dynasty, though in this case, the transition appears to have been a smooth one. And keep in mind that because Egyptian kings tended to marry their relatives, Snefru could have been related to Huni and Hetepheres, but from another branch of the ruling family.

By this time, somebody had gotten the idea that a pyramid with smooth sides would look nicer than a pyramid with steps. The pyramid at Meidum, which we now believe Snefru built, started out as another step pyramid, but when it was nearly complete, the plans were changed. Now the step pyramid was covered with white limestone to get the familiar triangle shape we associate with pyramids. Unfortunately, the sandy foundation could not support this much stone, and eventually the entire outside layer fell out, leaving a core surrounded by a huge pile of rubble. We used to believe that the collapse happened during the construction, but because no skeletons have been found in the rubble, from workers caught in the disaster, it now appears more likely that the builders abandoned the project when severe structural problems were found, and the collapse of the pyramid took place some time after that. In fact, graffiti from the XIX dynasty has been found at the site, suggesting the collapse took place more than a millennium later.

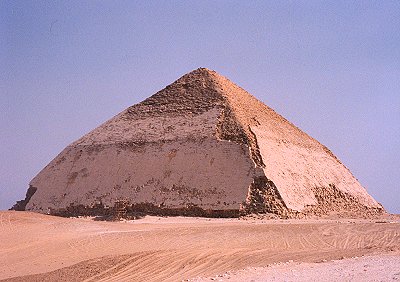

Leaving the Meidum pyramid unfinished, Snefru moved to another site, Dahshur, and started construction on another smooth pyramid here. However, the architects of the second pyramid must have feared the same stress problem would happen again, because when they were halfway done they changed the angle of the slope from 54o to 42o, a move which greatly reduced the number of stones on the top; this is the curious Bent Pyramid of Dahshur. They managed to finish this pyramid, but cracks appeared in it from a settling of the foundation, and they had to put wooden beams in the burial chamber to keep it from caving in, meaning the pyramid was unsafe to use.

Pyramid failures: the unfinished pyramid at Meidum . . .

And the Bent Pyramid at Dahshur. From Guardian's Egypt.

Snefru was not the type to give up after 29 years of activity and committed resources had failed to produce a good pyramid. We now believe he may have reigned as long as 48 years, meaning he had been blessed with a lifespan long enough to try once more. He built his third pyramid next to the "Bent" one, with a continuous angle of 42o from bottom to top, and this time the builders got everything right. This was the first true pyramid, the Red Pyramid of Dahshur.

The third time is the charm. Here is the Red Pyramid at Dahshur.

It may be that the architectural change occurred because a new god, the sun-god Ra, challenged the supremacy of Horus. Egypt was a land where the sun could be felt all year round, and the kings thought it would be good to identify themselves with this blazing power. Ra (also called Re), was represented as a hawk with a sun-disk on his head. The pyramid was now seen as a sort of sunbeam in stone, its sides reproducing the slant of the sun's rays when they broke through the clouds. The holy city of Ra was Heliopolis, located just east of Memphis; today it's a suburb of modern-day Cairo. To honor Ra, temples were built so that their entrances faced east, toward the rising sun, and the first obelisks (short and stubby compared with the obelisks raised later on), were built in their courtyards. Before long (probably in the V dynasty), the priests would invent Ra-Horakhty, a composite deity that combined characteristics of Ra and Horus.

Speaking of temples, the Bent Pyramid was the first pyramid to have a valley temple built with it, where the desert met the Nile flood plain. Like the funerary palaces of Abydos, the valley temples were a place to give offerings to the spirit of the dead king. To make it easier to bring in visitors, and building supplies like stones, a harbor was dug into the nearest part of the flood plain, allowing boats to dock almost adjacent to the valley temple. Snefru also surrounded the valley temple with a garden; a walled enclosure held trees like cypress and sycamores, in an attempt to turn a small patch of the desert green. Unfortunately, the garden soon failed -- sand does not support plants from other climates -- and that meant gardens would not be built near pyramids later on.

Though he kept the people building monuments, the ancient Egyptians considered Snefru one of their best rulers. We know it because our most complete Egyptian king list, the Turin Papyrus, has his name written in red ink instead of black; to the scribes he was a red-letter king! In addition, one of Snefru's titles was "He Who Makes Beautiful Things." They may have liked him because his other activities made the Old Kingdom a roaring success. Besides the pyramids, he was the first Old Kingdom ruler to lead military campaigns (raids into Nubia and Libya), he sent boats to Byblos in Lebanon to buy cedar wood, and he opened new copper and turquoise mines in the Sinai.

The reason why the Egyptians wanted Lebanese cedar was because it was the best quality wood in the known world. In most of Egypt, the only trees available were date palms, which are suitable for log rollers but a very poor material for carpenters. We believe that the first watercraft used by the Egyptians were woven out of papyrus reeds, though some wooden boats were found buried near the I dynasty tombs at Abydos. Once the trade with Byblos started, they could build large wooden ships; two royal barges, each about 160 feet long, were buried next to the pyramid of Khufu, the next king after Snefru. The wood for one of those ships was still in good shape when it was dug up in the 1950s; today you can see the reassembled ship at the new Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Finally, it should be mentioned that during the reign of Snefru, scribes changed the way of writing royal names. They got rid of the serekh, and from now on they would put the royal name in an oval. This oval is called a cartouche (French for "cartridge"), and we think the scribes meant it to look like a cord; in effect they were "roping off" the name from all the words around it.

A cartouche of Queen Hatshepsut, seen on an obelisk at Luxor. Source: Britannica.com.

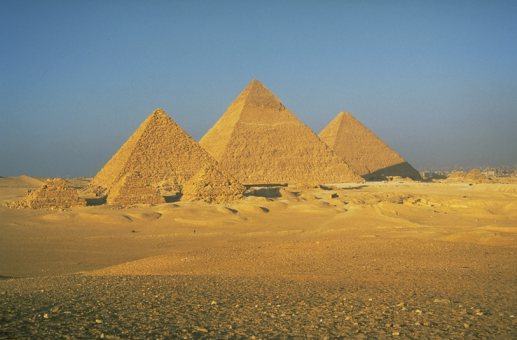

Snefru and Hetepheres were the parents of Khufu (Cheops in Greek). Under Khufu the Old Kingdom reached its peak, which he symbolized by spending his entire 23-year reign and the resources of the realm to build a giant pyramid at Giza. When completed it became not only the largest tomb ever built, but also the first of the world's seven wonders, the "Great Pyramid." It was laid out with geometric precision; the 755-foot-long sides miss forming a perfect square by less than eight inches, and the structure rises 481 feet from a base that is flat as a table. 2.3 million stone blocks, averaging half a ton each, went into the construction, and were fitted together so closely that a knife cannot be inserted between them. The result was a masterpiece that has dwarfed later, more technologically advanced civilizations, a monument that has produced endless books and speculation ever since.(10)

The Pyramids of Giza.

Khufu.

A statue of Hemiunu, Khufu's nephew, vizier, and foreman in charge of building the Great Pyramid.

In front of each of the three large pyramids at Giza are smaller pyramids. We believe they were for IV dynasty queens, but no inscriptions or artifacts have been found to identify who was buried in them. However, the most interesting queen's burial was that of Khufu's mother, Hetepheres, and she was buried not in a pyramid, but in a simple shaft grave next to Khufu's monument. When discovered in 1925, the grave had the world's oldest furniture, made of gilded wood; also present was a stone chest containing the queen's internal organs, but the sarcophagus, like that of Sekhemkhet, was sealed and empty. This has led to the idea that Hetepheres was buried in a more impressive tomb originally, but it was robbed and her mummy was destroyed, so the order was given to rebury what was left in a secret location. As for the sarcophagus, it looks like the tomb guards pulled a fast one, putting an empty box in the grave while telling Khufu not to worry about anything. Since it does not look like Khufu inspected the new grave, we think they got away with their trick; no doubt the king would have been greatly dismayed to learn that his mother's body had been lost, because that meant she would be gone from the next world as well as this one.

The labor and resources consumed in building the pyramids of Giza must have bankrupted the country, for nobody after Khufu built his tomb on such an extravagant scale. His son and immediate successor, Djedefre, did not build a pyramid at Giza, where he would have been competing with the Great Pyramid. Instead, he built a much smaller pyramid at Abu Rowash, five miles to the north. Because we now believe Dejdefre only ruled for eight years, a small pyramid in a new location worked out best for him and Egypt. When the Romans ruled Egypt (see Chapter 4), his pyramid was dismantled to provide building material for other monuments, so barely a trace of it remains today. It is also worth mentioning that Djedefre added "Son of Ra" to the official titles he already had. This shows the growing preoccupation with the sun-god during the Old Kingdom. For the rest of the IV and V dynasties, most of the kings will have some form of "Ra" or "Re" in their personal names, and some in the VI dynasty will have it as well.

Djedefre was followed by his brother Khafre (Chephren), who was ambitious enough to build his pyramid next to Khufu's, but he cut corners by making it a little smaller and leaving fewer passages inside it; by putting it on a higher elevation, he created an illusion that his pyramid was the larger of the two. Khafre also gets credit for building the famous Great Sphinx nearby, a symbol of the king's power which has the body of a lion and the head of a king, but recently it has been suggested that the Sphinx is older than the pyramids, and Khafre merely put his name on somebody else's work. People who think the Sphinx has the head of a woman are mistaken.

Here is a good place to mention an aspect of ancient Egypt that did not get much attention until recently -- the climate. We now believe that during the Old Kingdom, at least in northern Egypt, the climate was wetter than it is today. Chapter 1 of this work discussed how parts of the Sahara used to be green; what happened in Egypt is part of the same weather pattern. At northern Egyptian archaeological sites like Giza, sedimentary deposits have been found from torrential downpours, and these heavy rains came every four or five years, from the late IV dynasty until the VI dynasty. There are also signs of water erosion on the Giza monuments, especially the Sphinx. The rain meant abundant crops for the farmers, and prosperity for the kingdom, but it also threatened the tombs, which we already saw are the main source of Egyptian artifacts this old. For the tombs to effectively preserve their contents, they have to be kept dry at all times. Sometimes flood waters and mud got in, even when the tombs were sealed and undisturbed by robbers. Since this happened even to monuments on the Giza plateau, we know that the waters did not come from the annual flooding of the Nile. If the waters got into a sarcopohagus, only bones embedded in mud would be left for the archaeologists to find. The Egyptians tried protecting the tombs from flash floods by putting walls in front of doors, digging wells to catch the waters, and by placing the sarcophagus on a pedestal, rather than on the floor, but since they couldn't predict how high the waters would reach, these measures didn't always work.

Khafre's son and successor, Menkaure (Mycerinus), raised the third large pyramid at Giza, but scaled it down so that it was only one third the size of the first two. He may have done this because the cost of conscripting and feeding the workers had gotten too high, but Egyptians remembered him as a kind and pious king, while they called Khufu and Khafre tyrants. Menkaure died before his pyramid was finished, and left no son to succeed him. We now believe that the most powerful person at the end of the IV dynasty was Khentkawes I, a daughter of Khafre and sister of Menkaure. Khentkawes gained her exalted status by being the mother of the next two kings, Shepseskaf and Userkaf.

Shepseskaf completed Menkaure's pyramid, but then either relative poverty or a short reign kept him from building any other great monuments. For himself, he did not even try for a small pyramid, but set up an old-fashioned mastaba at Saqqara. It has also been suggested that Shepseskaf did not build a pyramid for himself because he opposed the cult of Ra, which was now identified with the pyramids; note that there is no "Ra" or "Re" in his name. If that was his intention, he failed. Khentkawes, on the other hand, got a small step pyramid and a temple at Giza, and for many years afterwards, a full-blown funeral cult made offerings to the queen mother's spirit at the temple, making sure she would not be forgotten. Because the transition from Shepsekaf to Userkaf was not a standard father-to-son succession, it looks like Egyptians saw that event as a dynastic break, though the IV and V dynasties were really two branches of the same family, just as the III and IV may have been. The V dynasty rulers went back to smooth-sided pyramids, and added to that sun temples and obelisks, all dedicated to Ra.

Everyday Life in Ancient Egypt

The pyramids reflected a rigid society, which was organized from top to bottom in four castes: gods, king, dead, humanity. The three groups on top were supported by and had absolute control over the masses on the bottom. The economy of Egypt can be called "theocratic socialism" because the state, in the person of the divine monarch, monopolized commerce and industry and was the ultimate owner of all land (although frequent grants were made to temples and private persons).(11) Pharaohs claimed their leadership role by performing essential religious rites on holy days, and by authorizing levees and canals to control the Nile on which everybody depended. The nobility lost its independence, and everyone, from field hand to vizier, was subject to a royal summons for whatever duty he might be assigned to perform. Since there was no law code or body of precedent, the king was the ultimate source of justice, whose word was law.

For a while, at least until the end of the Old Kingdom, the "humanity" caste was subdivided into three groups: Iry-Pat (also spelled Iry-Paut), Henemmet, and Rekhyt. The Iry-Pat were the original nobility, who could trace their ancestry back to the first worshippers of Horus. It has also been suggested that like the Maori of New Zealand, the Iry-Pat traced their ancestry to the crew of a specific ship that brought them to Egypt in predynastic days. At first the king and his courtiers were Iry-Pat only; in the tombs of Old Kingdom nobles, funeral texts pointed it out if the deceased was not Iry-Pat, meaning that he had become successful through some other means besides family connections. As for the other groups, the Henemmet ("Sun People") were the indigenous population of Upper Egypt, while the Rekhyt ("Lapwings"), the original Lower Egyptians, were ranked lowest of all, because they were in the last part of the country to be conquered during unification. The Iry-Pat jealously tried to protect their power by marrying other members of the Iry-Pat group as much as possible, but with commerce and intermarriage being what they are, eventually the differences between the groups blurred until they no longer mattered.

The king could not be everywhere at once, so it became customary to delegate his duties. Thus, the day-to-day administration of the land became the responsibility of the vizier, who had a host of titles and at least thirty major functions. The vizier oversaw the royal estates, supervised public works, commanded the army and police, commissioned artisans, distributed food to the many laborers and officials who worked for the king, and (most importantly) collected the taxes. Because Egypt was called the "Two Lands," there were two viziers most of the time, one for Upper Egypt and one for Lower Egypt. Later, during the periods when Egypt ruled Asian territory, like during the XVIII dynasty, the vizier of Lower Egypt was in charge of this land, too.

To get all his tasks done, the vizier employed a large corps of specialists--administrators, priests, scribes, artists, artisans, and merchants. Whatever a person's rank, he was taught that his welfare depended on absolute fidelity to the god-king. "If you want to know what to do in life," advised Ptah-Hotep, a V dynasty vizier, "cling to the pharaoh and be loyal." As a consequence, Egyptians felt a sense of security that was rare in Mesopotamia.

Ranked immediately beneath the vizier was a chancellor, who was followed by the nomarchs. Usually the nomarchs saw themselves as the ones who personally brought the king's righteousness to the provinces. "All the works of the king came into my hand," boasted one nomarch. "There was not the daughter of a poor man that I wronged, nor a widow that I oppressed. There was not a farmer that I chastised, not a herdsman that I drove away. There was not a pauper around me, there was not a hungry man of my time." This, however, was the ideal of government; in practice the main interest was not giving goods and mercy but to get labor and taxes from the peasants. Since it was a barter economy (money would not be invented for millennia to come), taxes were usually taken in the form of crops, and every part of the land was assessed according to its ability to pay. To make sure they did this fairly, markers called "Nilometers" were put in the Nile to measure how high it flooded every year; that way they would know to be lenient in the bad year that followed when the Nile did not rise much, or when it did not rise at all.

In Egypt, both agriculture and government relied on a three-season year. The first season, which ran from August to October, was called Akhet ("Inundation"). This was the time when the Nile flooded the land, and the peasants couldn't work their fields, so this became their vacation time. However, this was also when the king was most likely to draft them into building pyramids and other monuments, since they weren't doing anything else useful then. Then from November to February, there came a season known as Peret ("The Coming Out"), when the Nile receded, the ground was plowed and crops were planted. The third season, Shemu ("Drought"), was the dry season from March to July when the crops were harvested and the king's tax collectors descended on the land to take their share.

The households of those who worked for the king were quite elegant and comfortable. Such a house was built around an open courtyard, where the main feature was often a decorative pool filled with water lilies. The household staff included bakers, brewers, gardeners, musicians and handmaidens, who were either local-born servants or slaves captured on military expeditions to Libya, Nubia or the Holy Land. Banquets were boisterous affairs, where the main dish was a roasted goose or duck, accompanied by side dishes heaped high with bread, figs, and dates. At these affairs scantily-clad servants handled the needs of guests, while dancers and harpists provided entertainment. Beer and wine were made on the premises, and it was considered a compliment to the host if you got too drunk to get home without help.

As in other places, the government's work generated an endless supply of records, and it became necessary to employ scribes to keep up with them. For a writing medium the Egyptians used papyrus, a reed that grew all over the Nile valley. They laid flat strips of the reed's pithy center down in two layers, one perpendicular and one horizontal; then the strips were moistened, pounded smooth, and dried to form sheets of the first manufactured paper. To write on it they used reeds for pens, and scribes habitually carried a small box containing pens and dried red and black ink (like us, the Egyptian scribes used red to mark something they wanted people to notice, like a "red-letter day" or the name of a famous person). Because papyrus is so much lighter and more easily portable than the clay tablets of Mesopotamia, it would remain one of Egypt's primary exports until the introduction of modern paper-making techniques.(12)

Unlike their Sumerian counterparts, the Egyptians did not replace their decorative picture writing with abstract shapes, but went on drawing pictures of birds, people, snakes and various other objects for the rest of their ancient history, like this:

At first they simply used a different picture to represent each noun and verb, and later added other symbols for intangible things like ideas. As a matter of fact, we cannot really "read" the inscriptions that have come to us from before the Old Kingdom, but have to guess at their meaning, when all the scribes left were one or two words. The fully developed script of more than a thousand characters, which we call hieroglyphics ("priestly writing"), was used on temples, tombs and statues, for the same reason that we sometimes put Roman numerals on our buildings. However, they were difficult to learn and too cumbersome for everyday use, so early on the scribes came up with a simplified cursive script, known as Hieratic, where each symbol stood for a syllable rather than a word. This made their job easier when jotting down records that they did not expect to pass on to future generations. Eventually they also simplified Hieratic, to an alphabet known as Demotic, just before Greek and Roman scripts came in and replaced the older systems of writing completely.

It was this choice of scripts that made it possible for modern linguists to unlock the code of ancient Egyptian writing. In 1799 Napoleon Bonaparte's military expedition to Egypt uncovered an inscription dedicated to King Ptolemy V, who lived in 200 B.C.; this was the famous Rosetta Stone. The writing on the bottom third of the stone was Greek, which was already commonly known, while hieroglyphics decorated the top and Demotic filled in the middle. A young Frenchman, Jean Francis Champollion, correctly guessed that the three inscriptions all carried the same message, and reasoned that the ancient Egyptian language was Coptic, the same language used in the churches of Egypt. He also had a clue in that Ptolemy's name had already been translated by a British scholar, and it was written in an oval, called a cartouche by the French. This was a writing convention that the ancient Egyptians followed for most of their history. The oldest names of kings that we have were drawn inside a rectangle called a serekh, as if the Egyptians kept the name of their king in a box. Then in the IV dynasty, a cord laid out in an oval replaced the serekh, becoming the cartouche that was always used after that. For the Egyptians a king's name was so special that it had to be "roped off" from the other words. By applying Coptic sounds to the symbols and using the Greek translation to check his progress, Champollion eventually figured out how the ancient scribes used the enigmatic hieroglyphs, so now they are no longer a mystery.

It took twelve years of study and practice in a scribal school to master the system of writing. The student was not considered literate until he had learned 700 symbols, and discipline was tough, for teachers believed that "A boy's ears are on his back." Yet the prize was worth the pain. Those who succeeded in learning how to write could always find employment; it is estimated that less than two people along a mile-long stretch of the Nile Valley at any given time could read and write. This was the only place in Egyptian society where upward mobility was permitted; a peasant boy who did his homework could rise to become the king's personal secretary, or even his vizier. Two scribes of exceptional ability were even deified, the aforementioned Imhotep, and the XVIII dynasty's Amenhotep, son of Hapu.

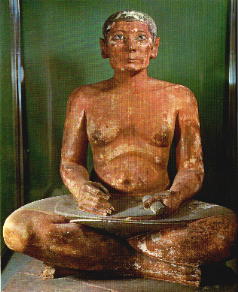

Statue of a scribe, from the V dynasty.

Compared with other ancient civilizations, Egypt gave its women extraordinary freedom. Equality of the sexes in Egypt is reflected in statues and paintings. Wives are shown standing or sitting beside their husbands, and little daughters are depicted with the same tenderness as little sons. The right of succession to the throne was based on royal descent from the mother as well as the father. Business and legal documents show that women in general had rights to own, buy and sell property without reliance on legal guardians, and to make wills and testify in court. A few became physicians, scribes and members of the administration.

As one might expect from this, the priests usually taught the scribes. There were plenty of priests around, since the Egyptian pantheon grew to house more than 2,000 gods. Besides national deities like Osiris and Horus, every town kept its own, and a few were imports from nearby non-Egyptians like the Canaanites. The myths surrounding the gods often clashed on details, like who created the universe (they gave credit for creation at various times to Ra; a deity named Tem or Atum; Ptah, the god of Memphis; and Amen, the chief god of Thebes), so Egyptian mythology is filled with an array of contradictions and inconsistencies that bewilder the non-Egyptian reader. Many of them were represented as animals, so one could say that the Egyptians worshiped anything that moves! Later they gave the gods more human forms; e.g., Horus went from being a falcon to a man with a falcon's head. During periods when certain gods were in favor, their home cities enjoyed prosperity from official patronage, pilgrims and commerce; for example, Heliopolis saw its best years as long as Ra was one of the chief gods.

The priests profited from the support of king and commoner alike. As time went on the gifts, especially those of land, made them powerful enough to act independently of the kings. The position of priest was hereditary--they regularly passed the job from father to son--but only the highest-ranking priests worked full time. Common clergymen and specialists like astrologers, scribes, readers of sacred texts, singers and musicians (the latter were usually women), lived on the temple grounds and performed their sacred duties for one month out of four. While on duty they lived ascetically; they wore white robes and animal skins, abstained from sex, washed themselves frequently, and the men shaved off all body hair, including their eyebrows. When their turn was up, they went back to being lay members for the next three months.

Egyptian Mathematics and Science

The Egyptians were less skilled in mathematics than the Mesopotamians. Their arithmetic was limited to addition and subtraction, a modified form of which served them when they needed to multiply and divide. They could cope with only simple algebra, but they did have considerable knowledge of practical geometry. The obliteration of field boundaries by the annual flooding of the Nile made land measurement a necessity. A knowledge of geometry was also essential in computing the dimensions of ramps for raising stones during the construction of pyramids. In these and other engineering projects the Egyptians were superior to their Mesopotamian contemporaries. Like other pre-Greek civilizations, the Egyptians acquired a "necessary" technology without developing a truly scientific method. Yet what has been called the oldest known scientific treatise, The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, was composed during the Old Kingdom. Its author described forty-eight cases requiring surgery, drawing conclusions solely from observation and rejecting supernatural causes and treatments. In advising the physician to "measure for the heart" that "speaks" in various parts of the body, he recognized the importance of the pulse and approached the concept of the circulation of the blood. This text remained unique, however, for in Egypt as elsewhere in the ancient Near East, doctors and scientists failed to free themselves from domination by priests and bondage to the gods. The Greeks would be the ones to accomplish this task.