| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A General History of the Middle East

Chapter 9: THE ISLAMIC EXPLOSION

570 to 750

This chapter covers the following topics:

Mohammed's Calling

The most important event in world history between the fall of Rome and the reawakening of Europe in the 15th century is the rise of Islam. In the first century of its existence Islam grew at an explosive rate (hence the above title), converting an awesome human mosaic from Spain to Pakistan. The founder of Islam was undeniably an individual who singlehandedly changed the world; for that reason we begin the story of Islam with the story of the man who started it all.

Only legends exist to tell us of Mohammed's early life. His father, a poor merchant named Abdullah, died before he was born. Fortunately for him, he had no shortage of relatives who were better off, for he came from a prosperous clan, the Hashemites; in addition, the Hashemites were members of the Quraysh tribe, which dominated Mecca. The Quraysh sent the orphaned infant out into the desert with a Bedouin family, believing that a life away from the city would be better for his health and character. A few years later he returned to Mecca, but his mother died soon after. His grandfather took care of him next, until he also died. Finally Mohammed ended up in the care of a wealthy uncle, Abu Talib, and under him he grew to adulthood.

Abu Talib was a merchant, and he taught Mohammed the important skills involved with the caravan trade. At least once he took Mohammed with him on the long journey to Syria, and here he had his first encounter with Christianity. After he grew up he was hired by another caravan leader, a business-minded widow named Khadija, to serve as his agent on the expeditions. Khadija noticed several positive qualities about Mohammed; he was intelligent and handsome, impartial in his judgments and totally reliable in all his dealings. Eventually that led to marriage; he was twenty-five at the time, she was forty. The marriage made Mohammed financially secure, and it appears to have been a happy one; while she was alive he took no other wife, though he was allowed to do so.

After the marriage he appears to have made no more long journeys. They had four daughters and two sons, one of whom they named Abd Manif, which means "the servant of the Meccan god Manif"; this suggests that in his early years Mohammed practiced the Sabaean creed of his ancestors. Only one of his children--a daughter named Fatima--lived to grow up.

Many other things troubled Mohammed as well. His own childhood poverty and tragedy made him acutely aware of injustice in the world. In Mecca the old virtues of equality, honesty, and courage were eroding, replaced by the greed of the civilized world's marketplaces. He saw the rulers of Mecca use their shrines to get as much money as possible from free-spending pilgrims. Like Solomon's Temple in the time of Jesus, the house of worship had become "a den of thieves." Drunken orgies ending in violence were commonplace, dancing girls inflamed the passions of visitors, and gambling tables stayed in business all night. The Sabaean religion provided no check against these vices. Unable to accept this way of life as "normal," Mohammed often spent his spare time meditating in a desert cave. This by itself was not unusual; many dissatisfied Arabs, known as hanifs, did the same, believing in one god and living a life of self-denial.

One night in 610, when Mohammed was forty years old, he was in the cave when he heard a tinkling of bells, followed by a majestic voice that identified itself as coming from the archangel Gabriel. "Recite!" it commanded. "What shall I recite?" asked the terrified Mohammed. "In the name of thy Lord the Creator, who created mankind from a clot of blood, recite!" The voice went on to speak of the nature of God, and Mohammed memorized and recited everything he heard. After that the voice ceased.

Deeply distressed, Mohammed hurried home to confide his strange story to Khadija. Had he gone mad? Was he possessed by an evil spirit? If either was the case, he would throw himself from a cliff. Khadija comforted him, and called in her cousin, an elderly hanif. No, the cousin declared, Mohammed was not crazy; he had experienced a true revelation like those in the Bible. God had called Mohammed to be a prophet to his people, and he must submit to His will.

Obediently, Mohammed went back to the cave for more meetings with Gabriel. Each time he learned more about God, or Allah, as he called Him. He learned that there is only one god, and all idols represent false gods. He also learned about God's nature: a lover of charity, both vengeful and compassionate, quick to punish injustice but willing to forgive anyone who repented and submitted to his commandments. On top of all this came vivid images of what life after death would be like; sinners will go to a fiery Hell, while the faithful will go to a garden called Paradise, where they enjoy unlimited food and drink, and are served by beautiful maidens (houris). Mohammed's revelations became known as Islam, meaning "submission"; a Moslem is literally "one who submits."

At first Mohammed shared what he had learned in secret, converting less than 40 people in three years. His first converts were friends and family: Khadija; Zaid, an ex-slave; Ali, the son of Abu Talib, and a wealthy merchant named Abu Bekr. Other early converts were downtrodden members of minor clans and a few ambitious young folks from the Quraysh who shared Mohammed's dislike of the way Meccan society was heading; the latter included two future Caliphs, Umar (Omar) and Uthman. Most amazing of all, he converted Umm Habiba, the daughter of Abu Sofian, the most successful merchant in the city, and she married another Moslem instead of someone from Mecca's upper class. By 613, Mohammed had enough confidence to begin preaching openly.

The growing community of Moslems began to alarm the wealthy Meccans. They took an immediate disliking toward Mohammed's social gospel, especially the zakat, a mandatory contribution of 2 1/2% of one's wealth to charity. They probably also did not like hearing that the faith they followed was a superstition, and that their ancestors were now roasting in Hell for believing in it. Finally, the Prophet's decrees against idolatry struck at Mecca's livelihood; a Moslem-ruled Mecca, they reasoned, would end the Kaaba pilgrimages and ruin business. Mecca was a holy place, and no blood could be shed within its walls, but the authorities could make life unpleasant for followers of the new teacher.

First they used verbal insults, calling Mohammed a liar and suggesting that his revelations came from nothing more than an active imagination. When that didn't work, threats followed; then the persecutions became physical. They threw dirt and filth at Mohammed and his followers during their prayers; they attacked them with sticks and stones; they threw Moslems into prison; they refused to sell things to them. An Ethiopian slave named Bilal (Islam's first black convert) was taken into the desert by his master and forced to lie shirtless on the burning sands, with a large stone placed over his chest that had these words inscribed on it: "There shalt thou remain until thou art dead or thou hast abjured Islam." As he lay dying of thirst Bilal refused to surrender, repeating the words "Ahadun, ahadun," meaning "One [God], one." Finally his master, seeing that he would never recant, sold him to a Moslem named Abu Bekr, who then set him free.

A few Moslems escaped to Ethiopia as early as 615. Mohammed stayed because his family connections protected him; nobody wanted to start a blood feud because of him. Then came a perplexing incident, which caused one historian early in this century, Sir Mark Sykes, to proclaim that it "proves him to have been an Arab of the Arabs." After all his insistence upon the oneness of God, he wavered. Perhaps like many Arab leaders today, he thought that a compromise might be better than consistency, in the short run anyway. He came into the courtyard of the Kaaba and suggested that the gods and goddesses of Mecca might be real after all, serving as saints or angels to mediate between God and man.(1)

They enthusiastically received his recantation, but when he saw the reaction he repented, and his repentance shows he really had the fear of God in him. His lapse from honesty proves he was honest the rest of the time. He did all he could to undo the damage he had done. He said that the devil had momentarily possessed his tongue, and denounced idolatry more vigorously than before. The struggle between Moslem and Sabaean started again, this time with no hope of reconciliation.

The Flight That led to Victory

Now the pressure on Mohammed steadily increased. In 619 both Khadija and Abu Talib died, depriving him of his family protection. In the same year Abu Sofian, now a bitter enemy of the Moslems (no doubt in part because they took his daughter away), became the leader of Mecca. Mohammed decided it was time to leave. At first he went to the nearby city of Taif, but Taif drove him out with stones and abuse. Then opportunity appeared in an unexpected direction. Disputes tore the city of Yathrib, some 250 miles to the north, between its two Sabaean and three Jewish tribes. Some of Yathrib's residents had converted to Islam during their pilgrimages to Mecca, and they wanted Mohammed to come and serve as a mediator between them. Mohammed sent his followers ahead of him, a few at a time, until only himself, Abu Bekr, and Ali remained.

Eventually the Quraysh elders caught wind of what was happening. The Prophet would be more dangerous than ever if he got away from them and took over a town on the main caravan route to Syria. Mohammed would have to die, blood feud or no blood feud. They decided to murder him in his bed, and to reduce the burden of guilt they elected a committee to do the job, made up of members from every clan in the city except the Hashemites. But Mohammed was already gone; when the assassins rushed into his room at night, they found Ali sleeping, or pretending to sleep, where the Prophet should have been. They tried to catch up with Mohammed and Abu Bekr, but the fugitives took a rarely-used road, and hid in a cave on the way. Their safe arrival in Yathrib marks the turning point of Mohammed's career. Moslems call this journey the hijra or hegira; the Islamic calendar begins counting years from the date when it took place (622). Yathrib also got a new name--Medinat al-Nabi, the City of the Prophet--Medina for short.

Mohammed's days of persecution were over, but he and his followers had no means of material support, and they could not live on handouts from their neighbors forever. To the Arabs the solution was to raid enemies for what they needed. Since the Quraysh of Mecca were the enemies of Islam, their trading caravans now became the target of Moslem raiding parties.

The first forays failed; either the Moslems failed to intercept the caravans or they were too well guarded. Nobody got killed and no booty was taken. Then in 624, a caravan of seventy merchants, one thousand camels, and 50,000 dinars' worth of trade goods, passed by Medina on the way from Gaza to Mecca. All the leading Quraysh families had invested in this venture. To ensure its safe arrival, 950 warriors left Mecca to escort it on the last leg of the journey.

314 Moslems waited for the caravan at Badr, an oasis near Medina. The caravan never arrived--Abu Sofian expected trouble and sent it on a different route--so when the Moslems launched their ambush, they found themselves attacking a force three times the size of their own. Moslem morale was greater, however, thanks to an earlier decree from the Prophet: "Not one who fights this day and bears himself with steadfast courage . . . shall meet his death without Allah bringing him to Paradise!" This promise and the element of surprise brought a complete victory. The biggest prize, the caravan itself, had gotten away, but routing the Quraysh warriors was no small accomplishment, and it provided some spoils of its own: 150 camels, 10 horses, some arms and armor, and captives to hold for ransom. Most important was the prestige gained; the battle of Badr convinced Moslems that God was on their side, and news of the battle attracted Bedouin recruits, who were more than willing to follow a successful military commander.

Despite the victory, the Moslems were still poor, so Mohammed made a Jewish tribe in Medina, the Banu Qainuqa, his next target. Mohammed's excuse was that the Jews, after hearing his teachings, had still rejected Islam. The Banu Qainuqa were surrounded, and forced to leave town; afterwards needy Moslems divided their belongings among themselves. Then came news of another Meccan caravan passing by on the way to Syria. Although it had an escort, and took a wide detour through the central Arabian (Nejd) desert to avoid Medina, the Moslems captured all of it, and brought home the richest booty yet.

This was too much for the Meccans to tolerate, so in the following year (625), Abu Sofian personally led three thousand soldiers north to deal Islam a crushing blow. He very nearly did; in the resulting battle Mohammed was wounded; he and the other surviving Moslems took refuge in a cave on the slopes of Mt. Uhud. At the end of the battle Abu Sofian advanced to the foot of Mt. Uhud and taunted the cowering Moslems with these words: "Today is in exchange for Badr. War is like a well-bucket, sometimes up and sometimes down . . . We shall meet next year again at Badr." Then the triumphant Meccans stripped the bodies of the Prophet's dead followers and rode away.(2)

Abu Sofian did not finish off Mohammed because for him, the point had been made. A victory at Uhud avenged the insult inflicted upon them at Badr and taught the Moslems to leave their caravans alone; once they achieved these goals, the war was over, at least by Meccan standards. Yet Mohammed did not regard war as a game, or commercial enterprise; he would wage it totally until one side was annihilated. By the time the Meccans realized this, it was too late.

Back in Medina, Mohammed explained the defeat by calling it a test from God to reveal whether his followers would be loyal in both good and bad times. Then he put them to work, to keep them from brooding about the disaster. They ran another Jewish tribe out of town, the Banu Nadir, after accusing it of conspiring with the Meccans against the Moslems. Outside the city, he sent raiding parties among the nearest Bedouins to recruit them into his ranks, by force if they would not join willingly. Mohammed also used political tactics that would be familiar to us today--oratory, propaganda, and a few well-placed assassinations--to bring the rest of Medina's population into line.

Uhud became a hollow victory for the Quraysh; they continued to lose face and allies to the Moslems, as if they had never won the battle. In fact, Mohammed's political campaign made no sense to them at all. So little did they understand what was at stake that they did not even bother showing up at Badr for the battle to which they had invited the Moslems one year earlier. The Moslems kept the appointment, however--and by doing so they gained even more prestige among the Bedouins.

Exasperated by the deteriorating situation, the Quraysh decided to eliminate the Islamic menace once and for all. In February 627 Abu Sofian led 10,000 men north to conquer Medina, an awesome force for that time and place. It was an entirely undisciplined force of footmen, horsemen, and camel riders. The Meccans must have thought that, because of their superiority of numbers, victory was in the bag. However, Mohammed had a Persian convert who had learned about combat engineering in his homeland; he suggested that a ditch and a wall around the city would make it more defensible. Every member of the community, including Mohammed, came out to help dig the ditch, finishing it just before the Meccans arrived.

This unexpected development completely baffled the invaders. They complained that it was dishonorable and un-Arabic. They rode around the city, shot a few arrows, and made a few halfhearted attempts to cross the ditch. Then they set up camp and simply stared at Mohammed's amazing outrage. They negotiated with the last Jewish tribe in Medina, the Banu Qurayza, in an attempt to attack the Moslems from within. Other than that nothing could be done. Mohammed would not come out; the weather turned cold and wet; life became miserable and tempers flared. After twenty days the Meccans, now demoralized and running out of supplies, went home. Their Bedouin allies dispersed into the desert and ceased to matter.

The battle of the ditch was no great military triumph, but it confirmed Mohammed's status as undisputed spiritual and political leader of Medina. Now he turned against the Banu Qurayza. This time, instead of just robbing them, he used the sword as the ultimate religious persuader. They sold every woman and child into slavery; they offered the men a final chance to convert, but none did and all were beheaded. After this, Mohammed never tolerated any opposition to his rule. He declared that never again would two religions coexist in Arabia, and that policy has been kept steadfastly to this day.(3) It also made Moslem and Jew perpetual enemies, leading to the struggles that mark Middle Eastern politics today.

From this point on, every advantage was with Mohammed. The Bedouin tribes started breaking their treaties with Mecca and made new ones with the Moslems. In the process, the Moslems gained control of more trade routes. By 628, Mohammed was strong enough to even wrest control of Yemen away from the Persians. Now he felt ready to take the offensive against Mecca. But after experiencing a dream where he saw himself making the traditional pilgrimage to Mecca unopposed, Mohammed decided to use politics rather than force to conquer the city. He headed south and ran into a Quraysh force with orders to block his progress; the two sides sat down to negotiate. In the end they agreed to let Mohammed make his pilgrimage--not this year, but the next. They really had no choice, because Mohammed was playing by their rules. If Mohammed made his visit during the holy month, he could not be opposed by force. If the Quraysh tried to break tradition by keeping him out or killing him, it would blacken the Quraysh reputation, and call into question the safety of all future pilgrims. That might end the pilgrimages altogether, and Mecca could not risk having that happen.

In 629 Mohammed and two thousand followers arrived to visit the Kaaba as agreed. To the relief of the Quraysh, the Moslems made no trouble; they entered the Kaaba, touched the Black Stone, and walked around the shrine seven times, just as pagans had been doing for centuries. True, they ignored the idols surrounding the temple, but that mattered less than the respect they gave the temple. The Meccans now thought that maybe Islam was not a threat to their income after all; maybe they could become Moslems and still have pilgrims come to their city.

Mohammed let this idea percolate in the minds of the Quraysh for a year before he came back. When he did, in 630, he led 10,000 armed men to Mecca. The overawed Quraysh submitted without a fight. Mohammed destroyed the Kaaba's 360 idols, but cleansed the Kaaba and dedicated it to Allah. The pilgrimages would continue; in fact they now became mandatory for all Moslems. A general amnesty was proclaimed, and all taxes were abolished except the zakat. Abu Sofian was even left in charge of Mecca, since by this time he had seen which way things were going, and converted. In short, the Meccans found submission to Allah to be nearly painless.

During the two years following the taking of Mecca, Mohammed's agents united the entire Arabian peninsula under Islam. Growing lusty late in life, Mohammed took nine wives (the Koran allows up to four, but they made an exception for the Prophet). His favorite among them was Aisha, the daughter of Abu Bekr. He married her when she was only eight years old and still playing with dolls; she would play a role in the shaping of Islam many years later. In 632, the 11th year of the Hegira, Mohammed fell ill and died. Yet what he started would live on; because of him the Arabs went from being a race of lean, hungry, camel-riding nomads to become one of the most influential peoples the world has ever seen.

What Islam Is All About

Islam succeeded because it was a religion ordinary people, not just saints, could understand. Its rules are simple and clearly spelled out; it agrees with the desert's rules of chivalry; its emphasis on universal brotherhood makes all men equal in the eyes of God. H. G. Wells, in his Outline of History, argued that Mohammed was a being of more common clay than most prophets; he probably would have lost if pitted in a debate against Buddha or Jesus. However, in the seventh century Islam's opponents were not what they used to be. Judaism was no longer political or willing to gain converts; Christianity and Zoroastrianism were weighed down by centuries of accumulated superstition. None of them could muster the religious zeal needed to put the Arabs back in their place when Islam burst onto the world scene.

The most important rules of Islam are commonly called the "five pillars" of the faith. They are as follows:

1. A declaration of belief: "There is no god but Allah, and Mohammed is his Prophet." This confession, preceded by the words, "I testify," automatically makes one a Moslem in the eyes of other Moslems. It also means that one accepts the other beliefs of Islam: that the Koran is God's word, that the angels exist as God's servants, and that there is a final Judgment Day for all men. After the confession there can be no turning back; the punishment for renouncing Islam is death.

2. Prayer, usually done five times a day. This can be done anywhere, but at noon on Friday, they prefer that the faithful join in mosques. At these times an imam, or prayer leader, leads the congregations, and after worship comes a sermon on matters of public interest. Usually this is the only role played in Islam by the clergy; it is both less organized and less significant than its counterparts in other religions.

3. Almsgiving, starting with the zakat tax.

4. Fasting during Ramadan, the month when God first revealed himself to Mohammed. The Islamic calendar is lunar, not solar, so Ramadan can come in any season of the year. They observe fasting during daylight hours, and during this time, Moslems may not eat, drink, or have sex; at nighttime the daylight restrictions disappear and are replaced with festivities. The month ends with a three-day feast that is as popular among Moslems as Thanksgiving or Christmas is for us.

5. The hajj, or pilgrimage. Once in a lifetime every Moslem who can afford the journey must travel to Mecca. More than a million Moslems come for this purpose every year, traveling from all corners of the earth, wearing identical garments. Most come during a special pilgrimage season, two months after Ramadan. This is considered the greatest event in the life of a Moslem, and those who make the trip may add the honorable title of hajji to their names. Mecca and Medina are the main holy places of Islam, and both cities are considered so special that only Moslems are allowed in them; they will kill on the spot any non-Moslem caught in either. Over the years a few "infidels" got in by dressing as pilgrims and becoming fluent in both Arabic and Islam, but no one who is openly non-Moslem has ever succeeded.(4)

A sixth commandment calls for all able-bodied Moslem males to engage in holy war, known as jihad. All Moslems are familiar with the idea of jihad, but most sects do not rate it as importantly as the five pillars. Unlike other religions, Islam has never had any moral questions concerning warfare; an armed struggle is just when waged in self-defense or to spread the faith where it did not exist before. Moslems view the world as divided into two regions, the land of Islam (dar-al-Islam) and the land of war or nonbelievers (dar-al-harb). Moslems consider a country Moslem if its leaders are, and pay no attention to what the predominant religion happens to be. This can lead to a point of view Westerners find unusual; for example, Moslems consider Libya to have been a Christian country during the years when Europeans ruled it (1912-51), although the colonial overlords probably converted nobody during that time.

For Moslems who participate in a jihad, morale is high because it is a no-lose situation for them. Those who fight and win will receive riches in this world; those who die in battle will immediately go to Paradise. When Islam conquered new areas, non-Moslems were not exterminated outright; instead, they were required to shoulder most of the taxes, while Moslems only paid the zakat. Christians and Jews received special treatment, being called Dhimmi, or "people of the book." They may practice their creeds, but from a uniquely humbled position (e.g., a church may not have a steeple higher than the nearest mosque, etc.).

Mohammed did not consider what he taught to be completely new. He saw Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and Jesus as authentic prophets of God, with himself as the final link in God's chain of revelations. Like Mani, he said that God had given his words to the founders of Judaism and Christianity, but the original message had been corrupted over time. Now Mohammed carried the pure revelation, and this time it was the final Word of God; no prophet would come afterwards.

Mohammed thought that Jews and Christians would readily follow him, once they recognized him as a prophet. Several Judeo-Christian traditions found their way into the Koran, and Mohammed initially adopted some Jewish practices, like circumcision, a prohibition on pork, fasting on the Day of Atonement, and praying toward Jerusalem. Later, when he realized that the Dhimmi would not convert so easily, he made Islam a religion with an Arabian character. For example, instead of calling the faithful to pray with bells or rams' horns, the voice of a crier announced prayer times; Bilal was the first so-called muezzin. Ramadan replaced the fast on Yom Kippur. Instead of praying toward Jerusalem, Moslems prostrate themselves in whatever direction Mecca happens to be in.

The Koran

Mohammed never wrote down his teachings; tradition says he could not even read. After his death, Mohammed's former companions saw the need to put the Prophet's words in a permanent form. Abu Bekr ordered the collection of every word from Mohammed that his scribes had written down and that his followers had remembered. From this came the Koran, or "recitation." However, at first there were several different versions of the Moslem holy book in existence. This caused confusion and some controversy, until Uthman, Mohammed's third successor, acted decisively. Around 650, he formed a committee, headed by one of Mohammed's former scribes, and they produced a standardized Koran. This became the official Koran, the one that is read today; all other copies were then destroyed.

The Koran is organized into 114 chapters, called suras. Since nobody knew for sure what order they were written in, they organized them by length; the longest suras come first, while the shortest are in the back.(5) The entire Koran, containing some 78,000 words, is about four fifths as long as the New Testament. Some Moslems can recite the whole book from memory.

The Ulema and the Shari'a

As time went on, issues arose that the Koran had nothing to say about. Islamic theologians, known as the ulema, were called upon to answer such questions. Usually they looked to the words and actions of the Prophet for guidance, or, failing that, one of his closest associates. When they could not bring these "traditions" to bear on a case, they used analogies. If even that could not be done, they called for a consensus of the faithful, arguing that Allah would not permit the entire Islamic community to err, however faulty individual judgments might be.

Often the ulema would sit in the marketplace of a town, ready to pass judgment on matters of conscience brought to them. They were never part of the government, but served its judicial function nonetheless by interpreting God's law, and thus became an important institution of Islamic society. Ordinary people appreciated their separation from the state, feeling that the best and wisest men were in charge of the things in life that mattered the most. By comparison, the type of people who happened to run the government, collect taxes, fight wars, and enjoy the luxuries of palace life did not seem terribly important.

In the eighth and ninth centuries, the ulema formed four judicial schools, and each composed part of the body of Islamic law now known as the Shari'a. Using the same logic as before, they considered the Koran to be their primary reference source, with traditions second, analogy third, consensus fourth, and personal opinion last. However there was (and still is) disagreement on the importance of each source. Some consider anything but the Koran and the traditions as too unreliable to use; one group even questioned the authenticity of the traditions and listed the ones it considered true.

The Shari'a lays down the laws covering the entire life and conduct of a Moslem. It is so intertwined with religion that most Moslems are unwilling to change it; the governments of Moslem countries have found it easier to declare all or parts of it invalid in their quest to keep up with the rest of the world. Nevertheless, it influences the lives of Moslems everywhere, and in the Moslem states where it does not form part of the constitution or legal system (e.g., Turkey), fundamentalists want to bring it back.

Islam and Women

Finally we should say a few words about the status of women. Islam has been accused of degrading women, because they are hidden behind veils and allowed little freedom in a society where polygamy is permitted. By modern standards it is true that Moslem women are second-class citizens, but to put the matter in perspective, look at how Arabian women were treated before Mohammed came along. In the pre-Islamic age, they saw women as little more than chattel. The rules regarding marriage were so loose that marriages were barely recognizable as such. An Arab could marry as many women as he liked, treat them as he pleased, and divorce them at will. Daughters had no inheritance rights and were often killed in infancy. There was even a word in classical Arabic--wa'ada--for the practice of burying a newborn girl alive.

Mohammed introduced several reforms to improve the lot of women. Infanticide was outlawed, and he required that daughters inherit half as much property as the sons. The Koran did not end polygamy, but it limited the number of wives to four, and required that husbands treat them equally (that last stipulation is so hard to keep that nowadays most Moslem men prefer to have only one wife). A woman could occasionally initiate divorce proceedings, and if her husband divorced her, she could keep everything she brought into the marriage. Sexual offenses like adultery could be punished by flogging or even stoning, but the testimony of at least four witnesses was required for a conviction, so they seldom inflicted the penalty. A major issue in the Islamic world today is whether or not they should give women the freedoms enjoyed by their Western counterparts; can the countries of the Middle East progress in technology and not in social matters too?

This digression on the nature of Islam has been a lengthy one, but necessary because Islam plays a critical role in Middle Eastern history, and a major role the histories of other regions, like Africa, India and Southeast Asia. Now it is time to return to our narrative. We will start by looking at what the major empires were doing during Mohammed's lifetime.

The Last Perso-Roman Wars

The continual success enjoyed by Persia under Khosrau I resurrected old fears in the Eastern Roman Empire. Justinian's heirs formed an alliance with the Turks, and made overtures to Ethiopia and Arabia, the ultimate goal being an encirclement of the Persians. A new round of hostilities broke out in 572, and lasted until both sides decided they had enough of it. Peace talks got underway, but Khosrau died in the same year, and his son and successor, Hormizd IV (579-590), preferred fighting to talking, so the conflict began again. This time it went on for as long as Hormizd ruled. Yet at home his popularity dropped steadily, especially among the Zoroastrian clergy, because he got along well with his Christian subjects. He fell victim to a conspiracy led by his chief general, Bahram Chubin, and Bahram used his Arsacid ancestry to claim the throne for himself. The crown prince, Khosrau II, fled to Constantinople, and the Eastern Roman emperor, Maurice, agreed to support him. In 591 Khosrau returned with an army that defeated and overthrew Bahram, and regained the throne for the Sassanids. To pay for Maurice's services, Khosrau ceded Iberia (northern Azerbaijan) and nearly all of Armenia.

In 602 Maurice was murdered; Khosrau, having learned from the Romans how to profit from dynastic strife, declared he would avenge his late benefactor. The last and biggest war began with the usual Persian raids upon Roman Mesopotamia and Syria, but before long it became an all-out attempt to conquer as much land as possible. Between 607 and 610 they reduced the fortresses of Roman Mesopotamia. Syria, Tarsus and Armenia were all overrun in 613. Jerusalem was taken in 614 by Shahrbaraz, Khosrau's best general, and the Persians hauled away the cross on which Jesus had been crucified as a war trophy.(6) Twice (608 and 615) a Persian army reached Chalcedon and stood on the Asian shore of the Bosporus, with only a mile of water separating it from Constantinople. Another talented commander, Shahin, conquered Egypt and Cyrenaica in 619. After centuries of conflict, the boundaries of the old Persian empire had been restored at last.

But only briefly. Heraclius, emperor since 610, spent more than a decade preparing his counterattack, and it began with a seaborne invasion of Asia Minor from the south in early 622. Appropriately, he landed at Issus, where Alexander had defeated the Persians almost a thousand years earlier. From there, instead of wasting his resources trying to regain ruined territories, he spent much of the year training the troops, and then struck north, scattering a Persian army led by Shahrbaraz and occupying Cappadocia. 623 and 624 saw Heraclius liberate Armenia and occupy Azerbaijan, where he captured and destroyed Canzaca (also spelled Ganzak), the site of a great fire-temple that marked the traditional birthplace of Zoroaster. Then near Lake Van, he defeated another Persian army and put King Khosrau to flight, but when he tried to invade Mesopotamia, he fell into an ambush, and only saved the day by leading a suicidal charge on a bridge over the Euphrates. Though wounded in that charge, he refused to turn back, prompting his soldiers to follow him and capture the bridge. Even Shahrbaraz admired this act of bravery, saying, "See your Emperor! He fears these arrows and spears no more than would an anvil!"

In 626 Heraclius met the Khazars, a fierce Turkic tribe, securing from them 40,000 men to back up his army. Meanwhile, Khosrau also brought in reinforcements. 50,000 men were conscripted, placed under Shahin's command and sent to get Heraclius, with a warning that failure meant death. An army of similar size was led by Shahrbaraz to take Chalcedon a third time, from which it would call in the Avars, then the dominant barbarian tribe of eastern Europe, and attack Constantinople from two directions. This put Heraclius in a sticky situation; if he pulled back to defend Constantinople, he would lose all the gains of the previous four years, but if he stayed in the east, Constantinople might fall. Characteristically, he chose a solution that would only work for him. He divided the Roman army into three parts, sending 12,000 men to Constantinople, giving another 12,000 to his brother Theodore for the job of facing Shahin's 50,000, and keeping the rest of the army (the smallest part) for himself, to use in a drive on the Persian homeland. All three divisions did their jobs; Constantinople's walls and ships wore down the Avar and Persian attacks, while a hailstorm allowed Theodore to win a smashing victory against his opponents. Knowing he was dead meat if either the Romans or his king got hold of him, Shahin committed suicide after the battle. Notorious for his cruel streak, Khosrau ordered the body of Shahin packed in salt and delivered to him; when it arrived, he had it whipped until it was unrecognizeable.

The success of the other Roman units was the signal for Heraclius to descend onto the plains of the Tigris. He was shadowed by a large Persian army, until it decided to make its stand near the ruins of ancient Nineveh (December 627). Heraclius won an eleven-hour battle here, which was largely decided by the deaths of three Persian generals, reportedly in single combat with Heraclius. Now the road to Ctesiphon was open, and the panicking Khosrau sent a letter recalling Shahrbaraz. The Romans intercepted this letter, and Heraclius cleverly replaced it with another letter that looked nearly identical, but ordered Shahrbaraz to continue the siege of Constantinople, thereby making sure that the Persians would be too busy to attack him in the rear. The next objective was Dastagird, where Khosrau I had built his grand palace, and which Khosrau II had made his headquarters when the war began. Without Shahrbaraz, the Persian king didn't even try to defend Dastagird, and withdrew to Ctesiphon to assemble a new army. Heraclius found Dastagird deserted, and ordered the destruction of everything in the palace the army could not take with it.

One would have expected Heraclius to continue on to Ctesiphon, but about fifteen miles from the city, he realized that he did not have enough men left to take the capital (the Khazars had gone home before Nineveh). Furthermore, would not have to overthrow his opponent, because the Persians were mad enough to do it for him. Shortly after he began to pull back, he intercepted another letter from Khosrau, calling for the immediate execution of Shahrbaraz because he had disobeyed the first order. This time he passed the letter on, after adding the names of four hundred other Persian officers to the list of the condemned. Thus, when the revolt against Khosrau broke out, it had the support of the army. His son Kavadh, disgusted that Khosrau had failed to defend either Canzaca or Dastagird, flung Khosrau into a former treasure-house of the king, a tower grimly called the "Tower of Darkness," and had him shot to death with arrows a few days later. Then he sued for peace; the war ended in 628 with a Persian army still outside Constantinople, and a Roman army near Ctesiphon.

The treaty signed by Heraclius and Kavadh II restored the prewar boundaries of the empires, and returned all prisoners and holy relics to where they came from. The True Cross went back to Jerusalem with Heraclius, and he replaced it with much pomp and ceremony. The whole war turned out to be fruitless and costly for both sides; nobody made any permanent gains, many people were killed, and those left alive were a quarter century older.

After the war ended, Heraclius completely overhauled the government of the empire. The changes were definitely overdue. To give one example, Latin was still an official language of the court, though Latin had passed out of everyday use in the sixth century. Since Constantinople was now the capital of a Greek empire, not a "Roman" one, historians mark the changes by calling the Eastern Roman Empire by the term "Byzantine Empire" after this, Byzantium being the original name for Constantinople.

Mohammed Announces Himself

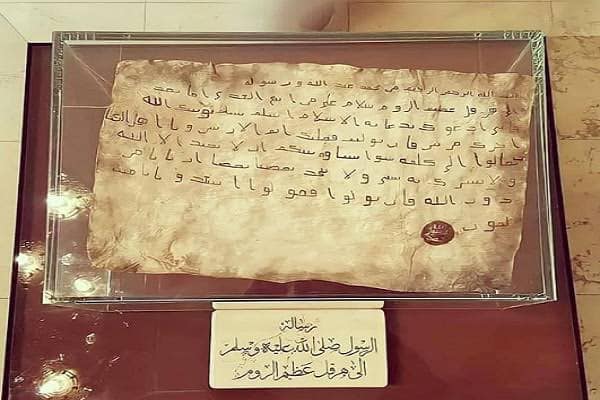

While the ink was drying on the treaty between Byzantium and Persia, a strange message came out of the Arabian desert. It was a letter written in Arabic, the obscure language spoken by the Semitic nomads on the far side of that desert. The script used was Kufic, an old version of the Arabic alphabet, which in turn was derived from the Aramaic alphabet. It was a challenge from "Mohammed the Prophet of God," calling upon the recipient to acknowledge the one true God and to serve Him. Copies of the letter went to all the foreign monarchs Mohammed had heard of. None of the original letters have survived to this day, but later on Arabic-speaking scholars made more copies of them. One of the medieval copies, of the letter sent to Heraclius, can be seen in Jordan, at the King Hussein Mosque. In 1976 a movie was made about the life of Mohammed, and it began by showing three couriers delivering those letters, so the movie was named "The Message."

Mohammed's letter to Heraclius.

A curious and positive response came from Taizong, the emperor of China. It took a whole year to deliver that letter. To reach the emperor, it was carried on a merchant ship across the Indian Ocean, and around Southeast Asia, to the Chinese port of Canton (modern Guangzhou); then it went more than a thousand miles overland to arrive at Changan (modern Xian), China's capital in the seventh century. Taizong thought the message was an offer to trade, and accepted on those terms. He was more receptive to foreigners and their ideas than most Chinese, but the Arabs did not follow up by sending a missionary to China for more than twenty years; by then Taizong was dead (the Arabs missed an opportunity here). At some point in the seventh century, the Chinese built a mosque in Canton for the spiritual welfare of the Arab traders who visited China. It later burned down, but a second mosque, called Huaisheng ("Remember the Sage"), was built on the same spot in 1695, and still stands today.

Another copy of the letter went to Alexandria, Egypt, for the Patriarch of the Coptic Church; apparently Mohammed thought he was a head of state. The Patriarch heard out the messenger, but he could not accept Islam, for the same reasons why today's Pope cannot convert to another religion. He politely declined, sent the messenger away with several gifts, including two women, and told his servants not to say anything about the matter.

Other rulers who received copies of the letters included those of Oman, Bahrein, and Axum (in Ethiopia). The author saw an Islamic webpage that asserted all of those rulers responded by converting to Islam. In Oman and Bahrein, the people supposedly followed the rulers' example, making an armed conquest by Mohammed's followers unnecessary. As for Ethiopia, we noted earlier that Moslem refugees fled there in the 610s and 620s, and supposedly that made the king of Axum, As-Hama, receptive to the new religion. However, the author could only find one list of Axumite kings, and it did not include a king named As-Hama. At any rate, Axum remained a Christian kingdom afterwards.

Likewise, we have no clear record of how Heraclius responded when the letter was read to him. Islamic tradition asserts that the emperor was interested in converting, but because of the Byzantine Empire's preoccupation with Christianity, his subjects talked him out of it. And it's unlikely that the emperor had heard of Mohammed previously.

However, at Ctesiphon they knew about Mohammed, because of his meddling in Yemen and other Arab-populated areas on Persia's frontier. The Persian king tore up the letter, flung the pieces at the envoy, and ordered him to leave.

The letter's author was just as angry when he learned of the Persian response. "Even so, O Lord!" Mohammed cried, "Rend thou his kingdom from him."

Finally, Mohammed sent an envoy to the Ghassanids, the Arabs on the Byzantine frontier, in 629, inviting their chief, Harith ibn Abi Shamir, to convert to Islam. Harith, who also had the title of Byzantine governor over the Syrian desert, angrily rejected the invitation, because he was already a Christian. Even worse, the envoy was killed by a local Ghassanid chieftain. Enraged at this violation of diplomatic immunity, Mohammed next sent an army of 3,000 men to punish the Ghassanids. However, according to the chronicler of the day, the Byzantines and Ghassanids had a combined total of 200,000 men to defend the frontier; whether this is an accurate figure or an exaggeration, it means the Moslems were hopelessly outnumbered. The Moslem commander was killed in the resulting battle, and then his replacement, and then the one who took the place of the first and second leaders. Finally, Khalid ibn-al-Walid (see footnote #2) was chosen to lead. By splitting small groups off from his force and cleverly maneuvering them in sight of the enemy, Khalid fooled his opponents into thinking that reinforcements had arrived, so they feared an ambush, and did not pursue when the surviving Moslems withdrew. This strategic retreat confirmed Khalid's status as the best Moslem general. The Byzantines and Ghassanids, on the other hand, saw the invasion as just another raid from desert nomads, if they bothered to remember it at all.

Jihad!

Mohammed left no will or heir, so when he died it was unclear who would succeed him. There could not be another Prophet--Mohammed had declared he was the last--but someone would have to take on his role as a secular and spiritual leader for the Islamic community. Such a person would from now on be known by the Arabic title of Kalifat rasul-Allah, the Successor to the Prophet of God. English shortens this title to one word: caliph.

There were several possible candidates for the job. Some thought that Ali should be the one, since, as the husband of Fatima, he was the Prophet's closest living relative. Others thought that leadership should go to whomever was most qualified, preferably somebody who had converted before the Hegira. The disagreement was settled in favor of the latter when Umar ibn al-Khattab, a Quraysh convert, placed his hand in that of Abu Bekr, Mohammed's most devoted follower, and said, "I offer you as Caliph." The rest of the community soon accepted this nomination, and he became the first of four caliphs who had known Mohammed personally.

Abu Bekr deserves credit for making sure that Islam would not perish with its founder. When he took over there were mass defections among the Arab tribes. Many of them had supported Islam because of the personality of Mohammed; now that he was gone, they felt that their oaths of loyalty were void. Abu Bekr, however, argued that nobody could go back to the tribal anarchy of pre-Islamic days; the old loyalty to one's tribe had been replaced by a new loyalty, to the universal tribe of Islam. Unwilling to compromise his faith, Abu Bekr sent Khalid ibn-al-Walid to bring the deserters back by force. Much of the opposition came from the neighborhood of modern-day Riyadh, where more than one tribal leader tried to imitate Mohammed by claiming to be prophets in their own right. The last and most dangerous of these false prophets was one Musaylimah the Liar (also called Muslaima or Maslamah bin Habib), who had forty thousand men against Khalid's thirteen thousand. Accounts vary as to what exactly happened when Khalid and Musaylimah met, at the battle of Yamana, but it appears that Khalid beat 3:1 odds with nothing but sheer ferocity, and Musaylimah was killed. By 634, two years after Mohammed's death, all of Arabia had been dragooned back into the ranks of Islam. Meanwhile Abu Bekr began gathering Mohammed's words into what would become the Koran a few years later.

Shortly before his death, Mohammed had expressed a desire to conquer the world. Now the Arabs were ready to do just that. They were motivated not only by missionary zeal, but by their poverty at home; furthermore, now that they could no longer make war on each other, they had to channel their aggressive instincts elsewhere. The nearest targets were the two Christian Arab states in northern Arabia, the Ghassanid and Lakhmid kingdoms, so for the first expedition, Khalid led 5,000 warriors against Hira, the Lakhmid capital. Around 602, the Persian king Khosrau II had demanded the Christian daughter of the Lakhmid king, Nu'aman III, for his harem, and when Nu'aman refused, Khosrau had him trampled to death by elephants. The Lakhmid kingdom was run ineffectively by a Persian governor after that, allowing Khalid to conquer it with a single battle. On the western front, the Ghassanids were still mad at Heraclius for cutting off the subsidy previous emperors had paid them for patrolling Byzantium's desert frontier. When the Ghassanids saw their Moslem relatives coming their way, they knew what to do; they simply switched sides, embracing Islam. The Byzantines, as expected, were tougher opponents, so Khalid was ordered to take command in the west. In a daring march he took 700 men across 500 miles of desert in 18 days. To survive the crossing without stopping at an oasis, the men brought camels, and when their water ran out, Khalid ordered them to kill the camels, cut open their stomachs, and drink the water the camels had stored in their bodies. Go ahead and say "Eewwww!" if you wish, and no doubt the water was disgusting, but the trick worked, and the men arrived in Syria just in time to surprise a Byzantine force.

At home Abu Bekr succumbed to old age, and just before the end he returned a favor by nominating Umar to be his successor. Historians often regard Umar as the best of the early caliphs because of the great conquests made during his rule (634-644) and because of his simple ascetic lifestyle; he wore old ragged clothes until they fell off, and lived in a mud-brick house in Medina. The change in caliphs caused no interruption of the Syrian campaign. Damascus fell in September 635 after a six-month siege. Byzantium sent reinforcements to deal with the Arabs, and Khalid faded into the desert until he saw an opportunity to strike. It came in August 636, on the banks of the Yarmuk River, a tributary of the Jordan just south of the Sea of Galilee. Waiting until a sandstorm blew into the enemy's faces, Khalid charged with 25,000 men and overwhelmed an army twice that size.

In 638 Jerusalem announced that it would surrender, but only if the caliph came in person. Umar agreed and made the 600-mile journey with only one attendant; they rode camels, and the caliph's only provisions were a bag of barley, a bag of dates, a water-skin and a wooden platter. His chief officers, all wearing splendid silks and riding equally fine horses, met him outside the city. At this sight the old man was overcome with rage. He dismounted, picked up stones and dirt in his hands, threw them at the gentlemen, and started shouting. What was with the fuss and feathers? Where were his warriors? What happened to his desert-hardened elite? He would not let these dandies escort him. Umar moved on with his attendant, looked for and found Sophronius, the Patriarch of the Church in Jerusalem and the highest-ranking Byzantine official present. He got along with the Patriarch much better, and together they toured the holy places, making jokes about Umar's too-magnificent followers. When they got to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, it was prayer time, and a soldier started to spread Umar's prayer rug on the floor of the church. However, the caliph chose to do his devotions outside instead. He knew that if the Prince of the Faithful prayed in a Christian shrine, some overzealous Moslems might be moved to turn the church into a mosque. And as if to prove his point, today a small mosque marks the spot where he prayed!

Now the only Greek strongholds left in the Levant were Ascalon and Tripoli; they capitulated in 644 and 645 respectively.

The Arab victories are astonishing on the surface. Both the Byzantine and Persian empires could field armies many times larger than those of the Moslems; their soldiers wore heavy armor and had siege equipment, while the Moslems had neither. Yet neither empire was what it used to be. Both of them were exhausted from years of warfare, and morale was poor. Both were in the habit of supplementing their manpower by recruiting Arab mercenaries, a sensible tactic until now. Heraclius was as worn out as his empire and suffering from dropsy; his Middle Eastern subjects knew little about him and cared less. His Persian counterpart, the parricide Kavadh II, died after a reign of a few months, and a series of dynastic intrigues and murders made for some lively stories but weakened the country. Within four years (628-632) an estimated eleven kings claimed the Persian throne. The Sassanid family ran out of men, and two daughters of Khosrau II held the throne, something that would have been unthinkable previously. Some generals, including Shahrbaraz, were also among those who made bids for the crown, drawing their support either from the army or from Byzantium. The anarchy ended in 632 with the coronation of Yazdagird III, an eight-year-old grandson of Khosrau II; he was found hiding in Istakhr and had to be crowned in that city. By that time, however, it was too late to save the situation.(7)

Another important factor was the discontent of the peoples ruled by the empires. The Monophysite Christians in Syria and Egypt resented being treated like heretics, and the Nestorians, though better treated, felt they had more in common with Islam than with Zoroastrianism. Whatever their faith, they were tired of supplying money and men to fight wasteful foreign wars. When they compared Byzantines, Persians and Arabs, the Arabs looked politically cleaner, more just and more merciful. Wherever the Arabs went, they never encountered a hostile guerrilla movement, or anything else that we would call popular resistance. In the areas they took over, the Arabs offered three choices: Islam, pay tribute, or death. Their new subjects saw the second option as a welcome relief, since taxes were reduced and non-Moslems were exempted from military service. In the end they saw the Arabs as liberators; conversion helped Islam to expand as much as conquest did.

The eastern campaign, interrupted in 634, resumed in 637. A Persian general named Rustam assembled his army at al-Qadisiya, on the plains of Iraq. It was a composite host, a medley of levies, with thirty-three war elephants and a golden throne on a raised platform from which he surveyed the battlefield. The whole scene must have resembled the battle of Gaugamela, where Darius III had wielded a similar army. For three days the Arabs attacked, and the Persian host held its ground. Late on the third day the Persians attempted to end the stalemate by sending in the elephants. This is rarely a good idea; elsewhere in my works I point out how elephants undid Porus of India and Hannibal at crucial moments; Shapur II very nearly suffered the same fate in his first battle. The pachyderms carried all before them until one was painfully wounded; it charged up and down between the armies, and its panic spread to the other grey monsters. Soon all of them were trying to escape from the two masses of armed men that hemmed them in. The battle was decided when the elephants broke through the Persian and not the Arab ranks. The Arabs followed, not resting until they routed the enemy. The platform and the golden throne were broken down, and Rustam was found dead among heaps of Persian casualties.

Yazdagird abandoned Ctesiphon, and the desert warriors entered the capital without resistance. The naive Arabs were overwhelmed by the wealth they found. One Arab was ridiculed for selling a young noblewoman for only 1,000 silver pieces, and he answered that he had never heard of a larger number. Some did not know the value of gold, called it "yellow money," and traded it for equal amounts of "white money" (silver). Others mistook camphor for salt, and seasoned food with it. They estimated the total treasure captured in Ctesiphon at nine billion silver pieces.

The conquest of Iraq also marked the end of Khalid ibn-al-Walid's career. In four years he had single-handedly defeated two of the world's greatest empires; by conquering the Fertile Crescent he had inflicted critical blows upon both Byzantium and Persia, from which they never recovered. Whether he served Abu Sofian, Mohammed, Abu Bekr or Umar, Khalid had never lost a battle. Still, Umar recalled and dismissed him in 638. Officially it was because of an act of extravagance--Khalid had given 10,000 silver coins to his favorite poet--but no absolute ruler can trust a general who is THAT successful; Umar later said he did it because no man should be relied on to give victory, for victory can only come from Allah. Khalid went home without protest, but he did have reason to complain when he died peacefully in 642. Having lived by the sword, he expected to perish by the sword, so when "the Sword of Allah" learned he was terminally ill, he reportedly made this lamentation: "I've fought in so many battles seeking martyrdom that there is no spot in my body left without a scar or a wound made by a spear or sword. And yet here I am, dying on my bed like an old camel. May the eyes of the cowards never rest."

Another commander, Amr ibn el-As, carried Islam to a second continent. During the Syrian campaign he had recommended an invasion of Egypt to cut off Byzantium's main source of grain. At the end of 639, he gained permission from Umar to try it, and raced toward the Egyptian frontier with 4,000 horsemen. But not long after it started, Umar had second thoughts, and sent a letter. It reached Amr at Rafah, a few miles southwest of Gaza.

Amr suspected the letter's contents. He did not open it until he reached El-Arish, Egypt's easternmost town. Sure enough, the letter ordered him to return if he was still in the Holy Land, but allowed him to go on if he was already in Egypt.

As in Syria and Iraq, the natives welcomed the Arab newcomers. Most of the country went over to them without a battle, leaving Alexandria as the only stronghold to take. The Arabs surrounded the city in the summer of 642 with 20,000 men, but without siege equipment or ships. This stalemate continued until September, when the Byzantines gave up and withdrew their 50,000-man garrison. The door was now open for the conquest of all North Africa.

Amr, like the conquerors of Ctesiphon, was awestruck by the splendors of white-marbled Alexandria. He seemed at a loss for words when he wrote back to the Caliph: "I have taken a city of which I can only say that it contains 4,000 palaces, 4,000 baths, 400 theaters, 12,000 greengrocers, and 40,000 Jews!"

While the First Byzantine-Moslem War (633-642) was winding down, the Arabs completely overran Persia. Both sides raided each other on the Iranian plateau for a few years, until the battle of Nehavend (642) put an end to Sassanid hopes. In this encounter, 30,000 Arabs defeated 150,000 Persians, if the records are accurate. The Arabs feigned defeat after the first skirmish, withdrew with the Persians in pursuit, surprised them between two mountain passes, and slew about 100,000 of them. Persia broke up into smaller states that the Arabs annexed piecemeal, and Yazdagird fled again, this time to Central Asia. He tried to recruit some Turkish mercenaries to regain his empire, but the Arabs came after him first. In 650 they took southeastern Iran, in 651 they took Merv, the last Persian province. There at Merv, one of Yazdagird's subjects (a miller) killed him for what money he still had in his purse. Except for a few nobles who maintained their independence in the mountains along the Caspian Sea (Hyrcania in ancient times, now called Tabaristan), all of Persia was now under Islamic rule. Twelve hundred years of rule by Japhetic or Indo-European peoples (Iranians, Greeks, Romans, etc.) was now over; the Middle East was back in Semitic hands.

The Persian inheritance included cool relations with the Turks of Central Asia and with the Khazars of Russia. The Turks were in too much confusion to do more than defend their own territories and for the present the Arabs contented themselves with a northeastern frontier along the Oxus, where the Persians often had it. However, the Khazar Khanate was young and full of beans, and the Khazar expansion southward ran right into the northward drive of the Arabs. The result was a three-cornered struggle between Khazars, Arabs, and Byzantines for control of Armenia, a struggle which lasted into the early eighth century. Armenia experienced the most unhappy form of independence, as a no-man's land between three major powers.

Umar tolerated Jews and Christians, but he told his soldiers to avoid getting too friendly with the Dhimmi, lest they become a debilitating influence. He also wanted them to avoid the vices of the great cities for the same reason. Most of the Bedouins complied, since they felt lost and out of place in the alien culture of a city. New cities arose on the edge of the desert, to serve as permanent campsites for the nomads. Two of them, Kufa and Basra, were built in Iraq; the third, al-Fustat ("the tent city") would one day become a suburb of Cairo. In 670 a fourth city named Kairouan was built in southern Tunisia.

Meanwhile, the conquest of vast civilized areas presented the Arabs with an administrative problem for which they lacked both equipment and experience. There was some confusion at first, but soon Arab governors decided that the easiest solution was to occupy a few key positions and leave the rest of the pre-Islamic bureaucracy intact to manage day-to-day affairs. In effect, each governor became the head of two regimes within the same territory, a Moslem and a non-Moslem one. The governor's job now became purely secular; collecting taxes and maintaining order were his priorities, not converting the population.

The Caliphate also underwent some changes at the core because of the success on the frontiers. Government expanded from the simple informal meetings of the past into a hierarchy that was more complex than anything the Arabs had known before. Gradually the caliph looked less like a spiritual leader and more like a temporal monarch of the old-fashioned kind. His vastly enhanced wealth and power made his job a center of intrigue and violence. Old tribal hostilities and patterns of thought, temporarily suppressed by Mohammed and Abu Bekr, returned to the surface after Umar's reign. We can say that Islam's greatest failure was its inability to overcome the Arab tendency toward tribal jealousy and personal politics; much of the instability in today's Middle East stems from that.

Troubles at the Heart of the Caliphate

In 644 a disgruntled Persian slave stabbed Umar in a mosque. Umar lived just long enough to remark that he was glad the man who killed him was a Christian and not a Moslem. We can see those words as a warning of the strife that would come a few years later. The next two caliphs would also meet violent ends, which in the Middle East is a sure guarantee of popular support for an individual's cause, if not for the individual himself. The martyrdom of Uthman and Ali would permanently divide Islam.

Before his assassination Umar had appointed a committee of six to choose his successor. They settled on Uthman ibn Affan, a member of the Umayyad clan, the Quraysh faction that ruled Mecca. Uthman was also a first cousin once removed to Abu Sofian, Mohammed's former enemy. Now through him, the Umayyads became leaders of the religion they had once opposed so vigorously. Uthman, like his predecessors, was noted for his piety and faithfulness, but he was weak-willed and a lover of luxury, particularly fine clothing. He increased Umayyad power over the state by appointing relatives to fill important posts when they became vacant. One such relative was his nephew Muawiya, the son of Abu Sofian and the governor of Syria.

While he was governor, Muawiya built the first Moslem navy. He quickly realized that while Byzantium commanded the sea, any army or city on the coast was subject to attacks from Byzantine fleets. Furthermore, Byzantine coastal cities could be supported indefinitely during a siege, since supply ships were getting in unopposed. Muawiya told Umar that the Moslems should have their own fleet, but Umar vetoed the proposal, thinking it too dangerous. Then came the Second Byzantine-Moslem War (645-656). In 647 the Moslems invaded Cappadocia, occupied the key city of Caesarea (modern Kayseri), and advanced as far as Phrygia before returning home with a large haul of loot. More interesting, however, was the naval acticity at that time; a Byzantine fleet captured Alexandria and it took fourteen months for the Moslems to regain control of the Egyptian capital. The new caliph, Uthman, saw the advantages of a navy and reversed Umar's decision. He gave Muawiya permission to attack Cyprus if he took volunteers only and if his wife came on the expedition--the last condition was a way of making sure that Muawiya acted with caution.

A few Arab traders had sailed on the Red and Arabian Seas for as long as anyone could remember, but most Arabs were unfamiliar with the sea. They made up for their lack of experience quickly enough, though. In 649 the fleet was ready and it captured Cyprus without a battle; in 652 it was used to beat off another Byzantine attack on Alexandria. At this point the Arabs seem to have had a technological advantage, the triangular or lanteen sail. The Byzantines and other Mediterranean seamen employed square sails, which are efficient in catching breezes from behind but not from any other direction. Ships with lanteen sails, by contrast, handle quite well in crosswinds, and can even go into the wind by tacking in a zigzag course. The Arab vessels thus enjoyed superior maneuverability in these early encounters. In 655, a Byzantine fleet led by the emperor met the Arabs off the coast of Lycia (SW Asia Minor); that battle, now called the battle of the masts, ended in a major Arab victory that shattered Byzantine command of the sea. Muawiya wanted to follow this up with a naval assault on Constantinople, but the civil war that followed the death of his uncle Uthman forced him to make peace with Byzantium instead.

At home, Uthman's nepotism offended Moslems from lesser tribes. Ali, the Prophet's son-in-law, never accepted Uthman as caliph; he had been a candidate for over a decade now and was tired of waiting for his own chance at leadership. Uthman was unable to control those who were dissatisfied. The first of several mutinies broke out at Kufa in 655. A delegation of 500 Arabs from Egypt came to Medina in 656, demanding Uthman's resignation. He promised to consider their complaints, but instead spoke out against the rebels in a Friday sermon at the mosque. The infuriated visitors stormed the Caliph's house. A few of them eluded the guards and got in by climbing over the back wall. They found Uthman reading the Koran and killed him on the spot, spilling his blood over the book he had served better than his nation.

Ali's reign (656-661) was troubled from the start. He was a brave warrior, but a poor politician. Many contested his election; the loudest outcry came from Aisha, the Prophet's widow, who had long nursed a personal grudge against Ali. She joined forces with Talha and Zubayr, two elders from Mecca who wanted the caliphate for themselves, and the three raised up a rebel army at Basra. Ali also hurried to Iraq, picking up supporters of his own at Kufa. The two sides met outside Basra, in a clash now called the battle of the camel, because Aisha rode a camel into the fray. Any hopes she had were quickly dashed. The two ambitious elders and 13,000 other rebels were slain, and Aisha, like Zenobia four centuries earlier, retired to a home in her enemy's capital. This was the first, and not the last, battle between Moslem and Moslem.

A more serious challenge came from the Umayyads. Muawiya suspected Ali's hand in the assassination of Uthman, and complained that Ali had not brought the killers to justice. Crying vengeance, he displayed his uncle's bloody robe in the mosque of Damascus. He immediately gained public support, not only from those who sympathized with him, but also from people Ali had alienated; one of the latter was Amr ibn al-As, who had recently been fired from his post as governor of Egypt.

Ali was now forced to fight Muawiya. The inevitable confrontation came in 657 at Siffin, a ruined Roman town on the Syrian-Iraqi border. At first, it looked like Ali would win again. Then the wily Amr came up with an ingenious idea: he had his men stick pages of the Koran on their spear tips, and marched them into battle shouting, "Let God decide." Ali saw through the trick, but most of his soldiers refused to strike down God's book. The battle stopped, and against his best judgment, he had to agree to a truce. Negotiations began, dragged on for six months, and ended with a decision calling for Ali to step down in favor of Muawiya. Naturally Ali refused, but his camp was torn by discord and unable to renew the fight.

Ali had no choice but to retreat to his base at Kufa. Some of his followers were disgusted that Ali would have the will of God superseded by human arbitration. They deserted him, forming an extremist faction known as the Kharijites, or "outgoers."(8) Within months they became such a threat that Ali had to confront them too. Ali came out victorious, but too weakened to deal with Muawiya. The Syrian leader added to Ali's humiliation by using Syrian troops to raid Iraq, and even won control over Egypt. In 661, Ali fell victim to a Kharijite dagger.

There was now no serious opposition to Muawiya, who had already proclaimed himself caliph from Jerusalem. He and the next fourteen caliphs would all come from the Umayyad family, forming a new dynasty. Ali's dismayed followers at first pledged their loyalty to Hasan, Ali's eldest son. However, Hasan was more interested in good living than in politics, and didn't need much persuasion to sell his claim to the caliphate for a sizeable pension.(9) Those who felt that Ali's family were the rightful heirs to the Prophet now pinned their hopes on Ali's second son, Hussein, and adopted the name of Shi'a, or partisans; the pro-Umayyad majority became known as Sunni, or orthodox Moslems. Thus a political dispute produced Islam's most fundamental schism; theological disagreements would come later, insuring that reconciliation would not occur. The division between conservative (Sunni) and radical (Shiite) Islam is still important today, when the Umayyads are no more than a strain on one's spelling.(10)

The Umayyad Caliphate

Muawiya made Damascus, his home and headquarters, the new capital of Islam. With this move Arabia ceased to be the political center of Islam, though it remained a spiritual center. The Moslem state also changed in other ways, becoming a true empire in the process. Muawiya ruled like a secular king, virtually ignoring the spiritual functions of his predecessors. Like a tribal sheikh, he surrounded himself with a circle of advisors who spoke frankly without fear of what his reaction might be, and like the Saudi kings of today, he kept himself accessible to his humblest subjects. He reorganized the government, making it more efficient and strengthening the caliph's power simultaneously. Muawiya ruled mainly through the power of persuasion, but later Umayyad caliphs became true Oriental monarchs, relying on the Syrian army to maintain order.

Meanwhile, a distinctive Islamic culture evolved, combining the ancient Roman and Persian heritage with Islam and the Arabic language. The use of Arabic spread widely, thanks to both the Bedouins and the Koran.(11) Gradually Arabic replaced the old languages of record-keeping: Greek, Aramaic, Coptic, and Farsi. In 696 the caliph Abd al-Malik made Arabic the only official language of the empire. Islamic money--gold dinars and silver dirhams bearing verses from the Koran--were minted to replace the Byzantine and Persian coins that were still in circulation. The caliphs undertook many public works, such as a postal system, elegant mosques and palaces, and the repair of long-neglected irrigation canals.

Islam, at least at first, brought unity and peace to a larger portion of the world than any empire had previously done, and trade flourished in such an environment. But whereas the last great commercial nation, the Roman Empire, formed a ring around the Mediterranean, the Arab empire occupied a solid land mass. Seas lapped its edges, but most merchants traveled overland. The great Roman ports of the Middle East and North Africa declined and none of the new cities the Arabs built were on the sea. So much did the Arabs ignore the classical trade routes that caravans even plied the barren Libyan desert on the way between Egypt and Tunisia. This is remarkable when one considers that sea transport is cheaper, and that the Arabs were perfectly good sailors. The outlook of the Arab, who is more comfortable on an ocean of sand, seems responsible for this. It exaggerated the tendency to trade mainly in luxury goods, which are small enough and costly enough to be transported great distances overland at a profit.

Despite his success, Muawiya was never able to please everybody, and this became evident upon his death in 680. Early in his reign Muawiya had made it clear that he wanted his son Yezid to succeed him. Yet many regarded Yezid as impious and foolish. The Shiites responded by bringing out Ali's son Hussein as a candidate for caliph. With his family and a few followers, Hussein went from Mecca to Kufa, where he expected to get enough Shiite support to march against Yezid. Before he got there, though, he was arrested by pro-Umayyad soldiers and held captive for ten days; then they killed him and sent his head to Damascus. The execution of the Prophet's grandson shocked Moslems everywhere and made more enemies for the Umayyads. He was buried in the Iraqi city of Kerbela, near Najaf, the burial place of Ali. Both of those cities are now places of pilgrimage for Shiite Moslems. On the anniversary of Hussein's death Shiites flagellate and/or cut themselves, doing penance for their ancestors who failed to defend Hussein in his hour of need. The spirit of martyrdom is thus very much alive in the minds of Shiites, wherever they are found.

After Hussein was eliminated another challenge to Umayyad rule appeared in Mecca. This time it was one Abdullah ibn al-Zubayr, the son of the Zubayr who had perished in the battle of the camel. In 682 he successfully defended Medina and Mecca against an attack from Yezid's army. Yezid died the following year, and Zubayr was recognized as caliph in Arabia, Iraq, and Egypt. However, the Umayyads proclaimed a caliph of their own, Merwan ibn al-Hakam. Merwan came out ahead after defeating Zubayr's supporters in a battle near Damascus in 684. He died in 685 and the caliphate went to his son Abd al-Malik, who now carried the war to the anti-caliph's stronghold; consequently a Moslem army ravaged Islam's holiest city. Catapults hurled stone missiles into Mecca; the Kaaba burned down; the Black Stone cracked. Nevertheless, Zubayr was killed, and the rebellions that shook Dar al-Islam were put down by 692.

In the last years of the seventh century the Ibadiyah, a moderate Kharijite sect(12), gained control of Oman & Yemen. When Ibadi converts appeared in Mecca and Medina the Umayyads reacted by suppressing the movement; in Yemen and the Hejaz they succeeded. However, they could do nothing to bring Oman back into the Sunni fold; in 751 an Ibadi imam became the Omani ruler. Fortunately for the Umayyads, Oman was (and is) so remote that it did not matter who owned it anyway. As a result, 60% of Oman's population is Ibadi today, long after the other Kharijite sects have disappeared.

Foreign Wars of the Umayyads

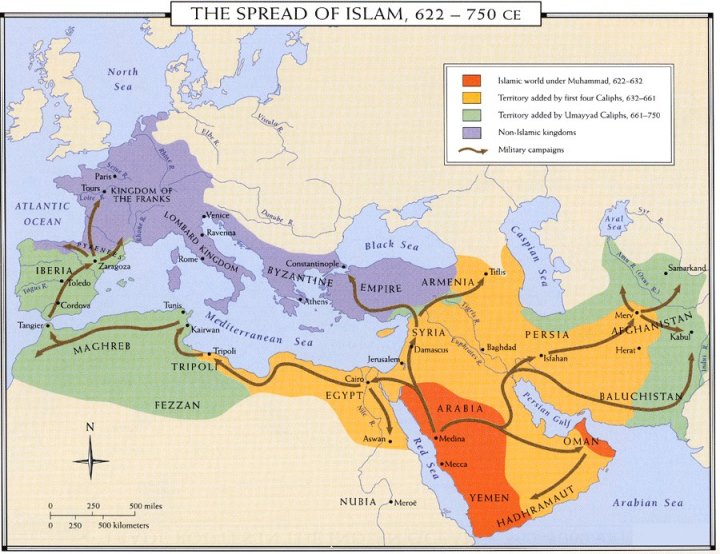

On the long and rarely peaceful frontiers the Umayyad caliphs were able military leaders, and they started a new wave of conquests that brought the size of the empire to its peak. The most spectacular victories came in the far west; all of North Africa was conquered by 700. Then they crossed into Europe and overran Spain, not stopping until they were defeated at the Battle of Tours, only 100 miles southwest of Paris (732).

On the central and eastern fronts it took a little longer for the Caliphate to get its second wind. The Arabs took until 717 to conquer Armenia and most of Georgia; then came a devastating invasion of the Khazar kingdom (737), which ended the raids from the north.(13)

The eighth century opened with the conquest/conversion of Afghanistan. In 712 the Arabs reached the Indus river, beginning a long uphill struggle to convert India that would last for centuries. Advances in Central Asia continued, but only gradually. Here the Arabs met an empire that was as strong and vigorous as theirs: China under its outward-looking Tang dynasty. China and the Caliphate competed for influence in Uzbekistan for half a century, both trying to win over the Turkish tribes. Here, as in Africa, the local emir (governor or prince), rather than the caliph, directed the campaigns. Still, the Arabs did not prevail over the Far East's champion until after the Umayyads were overthrown.

The armies of the Caliphate were least successful when trying to conquer the heart of Byzantium. When they entered Asia Minor every advantage was with the enemy. Mountains protected the land approaches, and Constantinople had the toughest fortifications of any city in Europe. The climate of the Anatolian plateau was too cold for the Arabs' liking, so they preferred seasonal sorties, making raids across the Taurus mts. in the summer and going home when the weather turned cold again. Most important, they enjoyed none of the popular support that paved the way for their previous conquests. The various peoples of Asia Minor were mostly Indo-European, not Semitic, and the Christianity they practiced was state-approved Orthodoxy. Morale went up, too; the Byzantine soldiers were no longer defending subjects who did not want to be defended, but their own homes, their religion, and their families.