| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 10: THE AGE WHEN EUROPE WOKE UP, PART II

1485 to 1618

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| How the White Man Got Ahead of Everybody Else | |

| The Politics of Europe at the End of the Fifteenth Century | |

| The Subjugation of Italy | |

| Artists of the High Renaissance | |

| Machiavelli | |

| The Beginning of the Spanish Century | |

| Sixteenth-Century Population and Economics |

Part II

| The Reformation | |

| The Ups and Downs of Charles V | |

| Revolts in France and the Netherlands | |

| The Spanish Armada | |

| Merrie Olde England | |

| Sweden Returns to the Stage | |

| How to Elect a King | |

| Go to Page Navigator |

The Reformation

The Church could be just as financially insolvent as the secular rulers of Europe, and here a clever entrepreneur saw an opportunity, where others saw a hopeless situation. In 1513 the archbishop of Mainz died, and Joachim, the prince of Brandenburg, immediately nominated his brother Albert for the job, because the archbishop cast one of the seven votes for the Holy Roman emperor. Albert was too young to be a bishop, but Pope Leo X was broke at the time, so he agreed to sell the title to him; in fact, he also let Albert become archbishop of Magdeburg and bishop of Hallerstadt! Then they haggled over the price. Leo asked for 12,000 ducats, one thousand for each of the Apostles, but Albert said he would only pay 7,000, since he would be dealing with the seven deadly sins; in the end they agreed to 10,000 plus the usual installment fees. In addition, Leo gave Albert permission to sell indulgences (see below) for eight years, with half of the earnings going to the Vatican and the other half being Albert's to keep.

The Archbishopric of Mainz, like most German states in the sixteenth century, was deeply in debt; Albert had to spend the Archbishopric's entire annual income to make the minimum payments on this debt. To recover what he had spent, he sent a Dominican friar, Johann Tetzel, on the most aggressive indulgence sales campaign to date. Then at the next imperial election, that of Charles V, Albert sold his vote for 90,000 ducats.

In medieval times the Church had encouraged Christians to show their devotion, usually by pilgrimages and Crusades. These didn't generate much income (unless you count the profits Italian merchants made when they followed the Crusaders), and went out of fashion before the Middle Ages ended. The church could also sell positions in its hierarchy to the highest bidders (this was the sin of Simony, the above story about the archbishop of Mainz is a fine example), but that income was limited by how many jobs could be offered and how many nobles had enough cash to make a bid. Then came two alternative ideas for making money: the sale of relics and indulgences. Relics (bones from the saints or artifacts mentioned in the Bible) were popular as long as the faithful believed they were real, but so many relics appeared that this was becoming doubtful by 1500(13); as a result, the Papacy called for more indulgence sales, without realizing that this market could become saturated, too.

The sale of indulgences wasn't anything new; the pope had legalized this practice in 1215. An "indulgence" was a spiritual pardon on a piece of paper that, when bought, gave forgiveness for all sins committed by the person whose name was written on it, whether he was living or dead; supposedly he would escape purgatory and go straight to heaven. Sales were entrusted to the most persuasive agents of the pope, who claimed that the Apostles and the saints had committed enough good deeds to get anyone past purgatory, if he will just show his faith by buying a guarantee from the Church.

Anyway, in 1517 Tetzel brought his traveling show to Saxony, the German state that was home to Martin Luther. Luther, an Augustinian monk from Wittenberg, had some serious questions concerning indulgences, since the Bible says nothing about the indulgence business. For years he had agonized over whether he had done enough to win the grace of God, and now people were coming to him for confession with certificates from Tetzel, claiming they already had forgiveness; you can imagine how he felt about this! What's more, he knew that none of the money raised would go toward the work of God; even the pope's half of it wasn't for the rebuilding of St. Peter's Cathedral, as he had claimed, but went to make payments on the Vatican's debts.

On October 31, 1517, Luther went to the door of the Wittenburg church and nailed a list of 95 theses he wanted to discuss concerning Church practices, most of them involving indulgences. This was the acceptable way to start a debate in those days--the document was written in Latin, for example--but it wasn't just theologians who paid attention. Luther acted at just the right time, and news of what he did spread like wildfire; in a matter of months copies of the theses appeared as far away as Rome and England. At this point, Luther didn't see himself as the founder of a new denomination; all he wanted to do was reform the church he had been born and raised in. Unfortunately for him, the popes of this age viewed any Christian who questioned their authority as a heretic. In 1520 Luther was excommunicated, but the princes and common folk of northern Germany turned to Luther in droves, when they saw him creating a church that was purely German and free of the practices that scandalized medieval Christianity. Protected by the Elector of Saxony, Luther was able to avoid being burned at the stake like Jan Huss. By 1534 he had completed a German translation of the Bible, and the first Protestant denomination was established on a sure footing.

Ordinary people may have been attracted to Lutheranism because it offered a simpler, less demanding theology. Heads of state, on the other hand, liked it because it gave them an excuse to confiscate much of the Church's property. In so doing, they gained the resources to pay off their debts, got rid of an uncontrollable, tax-exempt organization that sent money abroad, and replaced it with a church that was more compliant to their wishes. Thus, just as an explosion moves objects the fastest in the first second after it occurs, so Protestantism grew the fastest in the first generation of its existence. The king of Sweden became a Lutheran in 1527, and the king of Denmark did in 1536; in both cases, the people soon followed the royal example. Since Sweden ruled Finland in the sixteenth century, and Denmark ruled Norway and Iceland, that took care of Scandinavia. By the time of Luther's death in 1546, all of northeastern Germany was Lutheran; the new church had also converted most of Transylvania and Austria, and was making inroads into Poland. The Teutonic Knights dissolved their order when the grand master converted in 1525. In their place came a secular order, the Livonian Knights, which ruled Estonia and Livonia (Latvia) until 1561; in the end it submitted to Swedish and Polish rule to avoid being conquered by the Russians. In Bohemia and Moravia the Reformation gave new life to what remained of the Hussites.

The acceptance of Lutheranism as an alternative to the Catholic monopoly encouraged others to break with Rome. In Zurich, Switzerland, Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) set up a church that did away with many of the traditions the Lutherans and Catholics kept, and was more tolerant than the others. Around Germany's Black Forest, bands of peasants revolted against their lords in 1524, hoping to set up a classless, lawless society. They adopted the extremist doctrine of Conrad Grebel, one of Zwingli's followers, which predicted that the Second Coming would soon arrive, so no one should have a higher status or own more property than anyone else. Everyone who joined Grebel's church had to be rebaptised, because Grebel considered all other baptisms invalid, so they came to be known as Anabaptists, meaning "re-baptisers." Within a year they plundered many castles and monasteries, and a prophet named Thomas Münzer took command of a peasant army in Thuringia.

To Luther the Anabaptists were simply anarchists, and he became a defender of authority to keep them from undoing his accomplishments. Luther never wanted to get involved in politics; life is too short and eternity is too long, he felt, for any issues concerning social engineering or justice to be very important. He called for law and order in one of his angriest sermons, "Against the Murdering, Thieving Hordes of Peasants," and told the princes to massacre any rebels they got their hands on, while he continued to build a church that was both progressive and practical.

The princes of the ravaged territory needed no encouragement; in 1525 their disciplined armies killed more than 100,000 peasants, including Münzer. Individual Anabaptists ran around loose for some time to come, though, and in 1533 one of them, Jan Matthys, proclaimed himself the prophet Enoch, seized the town of Münster, and declared this would be the New Jerusalem, where Christ would return to redeem the earth. Both Catholic and Lutheran armies attacked Münster, and when they killed Matthys, his successor, John of Leyden, crowned himself king and restored the Old Testament practice of polygamy (this was done because of a severe shortage of men in the besieged city). In 1535 Münzer was taken and a horrible massacre of the last defenders concluded the war; more about that in the next section.

By this time, the Reformation had spread across the Channel to the British Isles. Henry VIII had been married for twenty-four years to a Spanish princess, Catherine of Aragon, but they only had one child, the future Mary Tudor. Kings marry not for love, but to produce royal heirs or to promote peace with the queen's country, and because they did not have a son, Henry wanted out. However, the Catholic Church refused to let him get a divorce, so in 1534 he formed a new church that said he could. Because it did not start over an issue of doctrine, the Church of England (also known as the Anglican or Episcopal Church) has fewer differences with the Catholic Church than other Protestant denominations have. It also looked like a compromise between Catholicism and the more radical elements of Protestantism; a lot of Englishmen weren't satisfied by it, and this would lead to more religious strife for the next century and a half.

Not long after this, radical Protestants found their spokesman. This was John Calvin (1509-64), a French scholar who moved to Switzerland after he converted to Lutheranism. Sixteenth-century France was a dangerous place for those who did not follow the same creed as the king; Francis I frequently shifted between toleration and persecution of heretics. In Basel he wrote his most important work, The Institutes of the Christian Religion. Revised by him several times after that, Institutes explained more clearly than any other book what the Reformation was all about. When he was done it left no detail of doctrine or conduct without rules governing it. It was both more logical and more somber than the writings of Luther. Whereas Luther mainly wrote about God's mercy and attacked those church practices which got between man and God, Calvin paid more attention to the Jehovah of the Old Testament, the absolute master of the universe, and talked about how the individual should behave. Calvin got his chance to put these ideas into practice in 1541, when he prepared a Bible-based law code for Geneva. It was enforced by a committee called the Consistory, or Presbytery, consisting of five pastors and twelve elders.

Calvin was never a member of the Consistory, but dominated it nonetheless. It oversaw the worship and moral conduct of every citizen in Geneva. It sent an elder to inspect each house at least once a year, and could at any time summon someone to account for his actions. Criminal offenses included missing church, laughing during services, wearing bright colors, dancing, playing cards, and swearing. Offenders were excommunicated, meaning they could not partake of the Lord's Supper and were not allowed to associate with citizens, though they were expected to listen to sermons all the same. Religious dissent brought much heavier penalties. The consistory frequently exiled offenders for blasphemy, mild heresies, adultery, or suspected witchcraft. Magistrates sometimes used torture to obtain confessions and sometimes even burned heretics, averaging more than a dozen annually in the 1540s. Michael Servetus (1511-1553), a Spanish theologian-scientist and refugee from the Catholic Inquisition, was burned for heresy because he denied the doctrine of the Trinity. The Consistory showed little sexual discrimination, punishing men and women with equal severity.

Geneva became known as the Protestant Rome, the focus of an authority even less compromising than that of the Papacy it opposed. Calvin's near-theocracy only lasted while he was alive, but during that time he gained followers all over western Europe. They went by a different name in almost every country where they established themselves: Calvinists in the Netherlands, Huguenots in France, Presbyterians in Scotland, Puritans in England, etc. Whatever their name, they only made limited headway in areas that were already Lutheran, but to those who had to fight for what they believed, Calvin, rather than Luther, was the real leader of the Reformation.

Indeed, the Protestants had to fight for everything they gained after 1545. This was because (1.) the movement was now threatening the two most powerful dynasties of Christendom, the Hapsburgs and the Valois, and (2.) the Catholic Church was now beginning to defend itself effectively. Francis I would have gained nothing by converting, because the French crown already enjoyed some control over its churches, so while individual Frenchmen converted, there was little hope of making France a Protestant country. Prospects for converting Spain were close to zero, because Cardinal Ximenes had purged corruption from the Spanish churches before Luther appeared. As for Charles V, if he had put politics before religion, he would have sided with the Lutherans, and Germany wouldn't have given him so many headaches. He didn't even get along with the Papacy very well; the pope endorsed Francis I in the imperial election. Instead, Charles couldn't see how Luther could be right, and how so many medieval theologians could be wrong, so he remained loyal to the Catholic faith.

In the middle of the century, the Catholic Church regained enough confidence to launch a "Counter-Reformation." By this time even the popes could see that they needed to clean up their act, and correct the errors pointed out by the Protestants. Pope Paul III (1534-49) attacked the indifference, the corruption, and the vested interests of the clerical organization, and was stubborn and bad-tempered enough to get his way. Under him and the next two popes, Paul IV and Pius IV, a major church council met at Trent, in northern Italy, to correct the behavior of worldly bishops and cardinals, and to explain in writing, the way Calvin did with Institutes, what the Church believed and why it did so. The Council of Trent met in three sessions between 1545 and 1563. Political turbulence in Europe, a threat of plague, and the pope's personal reform campaign caused lengthy interruptions; during the eighteen years of the Council's existence, it only actively worked for four and a half of them. Nevertheless, it was the most important Church convention between the Council of Nicaea (325) and the Second Vatican (1962).

Once the clergy was finished at Trent, the Church went to war against Protestants and other heretics. In Spain, Italy, and the Netherlands, the Inquisition, more than ever before, became the dreaded scourge of Protestants. The Church also had the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), a new order of priests who were organized along military lines, and educated enough to beat the Protestants at their own game. Although the "Counter-Reformation" failed to recover any lost countries, it effectively erased any Protestant threat to those still under Catholic rule. As a result, every country that was Catholic in the 1560s is still Catholic today. Jesuit missionaries also went overseas to the newly discovered lands in Asia and the Americas, where they converted enough natives to replace the parishioners lost at home.(14)

A Few Words About the Atrocities

We often think of the Middle Ages as a time when "man's inhumanity to man" was at its worst -- hence we use the phrase "getting medieval" as a euphemism for brutality. But in my own research, some of the most hideous torture and execution scenes took place in the sixteenth century, after the Middle Ages supposedly ended; they're bad enough to make me glad I didn't live in those days. You may have heard of some of the stories, like the life and death of Mary Queen of Scots. This was especially the case when a peasant revolt broke out. As with the Wat Tyler Rebellion in the previous chapter, the elite of any nation got really angry at those who spoke out against or fought the system they ruled. Therefore these uprisings were crushed with atrocities so horrible that you probably won't ever see them acted out, in movies or on TV; even George R. R. Martin might think the violence is uncalled for.

Speaking of gratuitous violence, a fine example broke out in Hungary in 1514. Early in that year, a cardinal returned with a Papal bull from Pope Leo X, ordering the raising of a Crusader army to march against the Ottoman Turks. György Dózsa, a veteran of previous wars with the Turks, was picked to lead this force. Not a smart idea, when you consider that the age of crusading was over; the original Crusades in the Middle East had ended two hundred years earlier, the Baltic Crusade had ended one hundred years ago with the battle of Tannenberg, and the Crusades in Spain had ended with the final defeat of the Moors in 1492. The Hungarian nobility did not want to see their peasants go off to war when they should be planting crops, and refused to assume their traditional role as the officers in this army. When the landlords ordered the peasants to return to the fields, and started to abuse their wives and families, the previously mentioned cardinal called off the Crusade, and the peasant recruits, already angry at how they had been oppressed for many years, attacked their former masters instead of the Turks. Because their revolt was unexpected, the peasants slaughtered thousands of people who held higher status than they did, and destroyed several manor houses and castles, but the surviving nobles had soldiers with more experience than the peasants, and they put down the rebellion in a few months.

Dózsa was captured, and his captors thought of a special punishment for the man who would be king. They forced Dózsa to sit on a red-hot iron chair, wear a red-hot iron crown, and hold a red-hot iron scepter. But roasting him alive wasn't enough; before he was dead, the captors tore at his body with hot pliers, and ordered nine other captive rebels to bite him on the wounds and eat his flesh. Those rebels had already been starved to put them in the mood for doing this, and the three or four who refused to obey orders were slain on the spot. Finally, the woodcut made of the execution scene shows some other victims impaled around Dózsa's "throne," and at least one individual is playing bagpipes, adding an insane musical soundtrack to the affair. Fortunately there weren't cameras or any kind of sound recording devices to give us a better idea of what happened, and I am keeping the picture of the woodcut behind this link, so you don't have to look at it if you are eating while reading this paragraph.

The Ups and Downs of Charles V

Charles V won the first round against his main rival, Francis I. They started fighting almost immediately after he became emperor, and Charles defeated a French invasion of Spain near Pamplona, drove the French out of Milan, and reinstated the Sforza family there (1521-22). Then a German mercenary army invaded France, failed to take Marseilles, retreated in the face of a French counterattack, lost Milan, and was surrounded in Pavia (1524). Despite this reverse, having the fighting in Italy (rather than Germany or the Low Countries) worked in Charles' favor; Charles still had Naples firmly under his belt, Pope Clement VII supported him where Italy was concerned, and so far Spain had won every war in the peninsula. Henry VIII was also on his side; though Henry had run against him in the imperial election, the traditional English dislike for the French outweighed any differences Henry and Charles might have. Francis was still besieging Pavia in 1525 when a fresh German force caught him by surprise and wiped out his army. Francis was wounded and taken prisoner; he sent a letter to his queen stating that all was "lost but honor." Charles imposed a humiliating treaty, in which Francis had to give up his claim to Italy, surrender Artois, Burgundy and Flanders, and pay a ransom of two million ducats. Nevertheless, Francis refused to give up, and renounced the treaty as soon as he was free, meaning that even honor wasn't saved for long.

Francis initiated the second war only a year after the first one ended. This time he thought the balance of power had shifted to him, because Henry VIII and the pope, fearing that the Hapsburgs were getting too strong, withdrew their support for Charles. The shifting political kaleidoscope now produced a new alliance (the League of Cognac), this one made up of France, Milan, Florence, Venice and the Papacy. It wasn't enough to stop Charles, though; in 1527 his Spanish soldiers and German mercenaries marched on Rome and sacked it. The pope was captured, and since some of the Germans were Lutheran, they had a good time making fun of him, before accepting the ransom of 400,000 ducats that he paid. However, the commanding officer, Constable Bourbon, was killed in the battle for Rome, and the leaderless mercenaries, many of them starving and unpaid, committed many atrocities in the city. As a result of this, the Renaissance came to an abrupt end in Italy.

North of Rome, the French rallied successfully, and retook Milan in 1528. Then Charles persuaded Genoa to switch sides, depriving the French of their main base in Italy. By this time both Francis and Charles were tired of fighting, so in 1529 they agreed to "the ladies' peace of Cambrai," in which Francis again gave up all claims to Italy and Burgundy. Now the pope, realizing that Charles, and not Francis, could help him in Italian affairs, signed a treaty of alliance with Charles (the treaty of Barcelona, 1529). This treaty also ended the Guelph-Ghibelline rivalry, which had afflicted Italy for four and a half centuries.

No longer enemies, the pope and the emperor attacked Florence, which had opposed their authority; the Florentine republic could not resist both, and surrendered in 1530. Now the remaining Italian states, except for Milan, Venice and Savoy, submitted to Spanish rule. In 1530 the pope finally gave Charles a proper imperial coronation, which had been delayed for a decade by politics. Charles was the last Holy Roman emperor to be crowned by a pope; they held the ceremony at Bologna, and the pope also crowned him king of Lombardy, though Charles didn't do much with this title until he annexed Milan in 1535. Two more wars between Francis and Charles (1535-38 and 1542-44) did not change the situation in Italy.

In the chain of Hapsburg-ruled territories around France, Germany was the weakest link. Here all of Charles' enemies could (and did) make trouble. Gradually Francis realized that by pushing toward the Rhine, instead of over the Alps, he could make real gains for France; if he got enough German land, it might even be possible for a future French king to become emperor. The new Turkish sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, became an ally of the French, making it possible to attack the Empire from both west and east. This was a classic case of politics making strange bedfellows; Francis had a hard time justifying what many Christians saw as a deal with the devil. Early in his reign, Charles turned over Austria and Slovenia to his brother Ferdinand; he had enough work to do with Francis trying to break into Germany and Italy.

Matthias Corvinus, the Hungarian hero, died without leaving an heir in 1490. The Hungarian nobles elected Vladislav (Lasislas) II, the king of Bohemia, to succeed him, because he was more pliable than the other candidate, Austria's Emperor Maximilian. In 1516 Bohemia and Hungary were inherited by Vladislav's teenage son, Louis II. Louis kept peace with the Hapsburgs through two weddings; he married Mary, a sister of Charles and Ferdinand, while his sister Anne married Ferdinand.

He would have been better off negotiating with Suleiman the Magnificent. The Hapsburg territory next to Hungary was only capable of self-defense, while after a 40-year pause, the Turks were now ready to resume their advance into Europe. At this stage the Ottoman army was larger and better organized than that of any opposing state, and morale was high, especially among its elite troops, the famous Janissaries. In 1521 the Turks crossed the Danube and took Belgrade; in 1526 they won a total victory at the battle of Mohacs, slaughtering Louis and the Hungarian army.

The defense of the West now fell on Austria. Because Louis had died childless, the Hapsburgs had a good claim to his sizeable kingdom. Ferdinand moved to take it immediately, calling for unity to keep central Europe out of the hands of Islam, and offering enormous bribes to those who weren't moved by religious talk. Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia submitted to Hapsburg rule, and Poland and Venice became allies, but the Hungarians preferred to be ruled by a Hungarian prince, John Zapolya of Transylvania, even if he was pro-Turkish. Suleiman responded by chasing Ferdinand out of Hungary, and advanced all the way to the gates of Vienna (1529). Ferdinand managed to hold out in Vienna, but it was weather, rather than might of arms, that saved him; the Turks arrived too late in the campaign season to stay very long, and had to withdraw when it started snowing. The Turks tried again in 1532, but again it was autumn by the time they got to Vienna, so the second siege was a short one, too. One year later Ferdinand and Suleiman agreed to a treaty, which let Ferdinand have a small strip of Hungarian territory. Suleiman didn't bother him for the next few years, because he was busy fighting the Persians on the other side of the Ottoman empire.

The treaty also promised that the crown of Hungary would go to Ferdinand on John Zapolya's death. Instead, the Hungarians crowned Zapolya's infant son, Sigismund, in 1540. Ferdinand cried foul and marched on Buda, the Hungarian capital, and Zapolya's widow called on the Turks for help. The resulting war lasted until 1547, when troubles on the Persian front forced Suleiman to make peace again. This time central and southern Hungary came under direct Turkish administration, Sigismund became "prince" of Transylvania, and Ferdinand got to keep "Little Hungary" in return for an annual tribute.

Charles V was least successful as defender of the Catholic Church. He followed in his grandfather's footsteps with naval attacks on Tunis (1535) and Algiers (1541), but failed to keep the Turks from conquering most of North Africa. As for the Protestants, most of the 1520s went by before Charles could do anything about them, and by then Lutheranism had spread too far to be stamped out. Attempts to resolve differences through a conference at Augsburg failed, and the emperor ordered all Lutherans to return to the Catholic Church by April 15, 1531. Nine Lutheran states responded to this ultimatum by sending delegates to the small town of Schmalkalden, and formed the Schmalkaldic League, pledging that: "Whenever any one of us is attacked on account of the Word of God and the doctrine of the Gospel, the others will immediately come to his assistance." Other states and towns joined, until it included most of the Protestant states in the Empire. This put Catholics and Protestants on an equal footing in Germany, and gave the Protestants a force that could meet nearly anything the emperor could dish out against them. Charles ignored them at first, continuing to concentrate his attention on Francis and Suleiman; he even asked the Lutherans for assistance in his other wars. In 1544, fearing that the League was about to join forces with Francis, he gave it formal recognition. Then in 1546 he changed his mind and tried to destroy the League. Charles' forces were led by Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, the Third Duke of Alva, and when some League members went over to his side, he didn't have too much trouble defeating the rest; both the Elector of Saxony and the Landgrave of Hesse were captured. However, yet another war with France broke out in 1547, so Charles had to negotiate peace instead of finishing off the Protestants. Finally, in 1555 he signed the Peace of Augsburg, a treaty granting every prince the right to choose whether he and his subjects would be Catholic or Lutheran.

This was not a promise of tolerance as we would understand it. The most certain way to enjoy religious freedom was to move to a state where the local ruler shared your faith. If you were an Anabaptist or a Jew, you were still out of luck; no head of state followed those creeds. Because the agreement was so vague, more religious wars would be fought in the next century, culminating in the Thirty Years War, before a final settlement was reached.

After Augsburg Charles was tired of life, so in 1556 he abdicated and withdrew to a monastery in Yuste, Spain. Here he tried to give up his responsibilities, but not the luxuries and authority of royal life; the letters he sent to his son, Philip II, were treated as official decrees. Two months before his death in 1558, he staged his own funeral, and attended it in disguise so he could see for himself what it would look like.

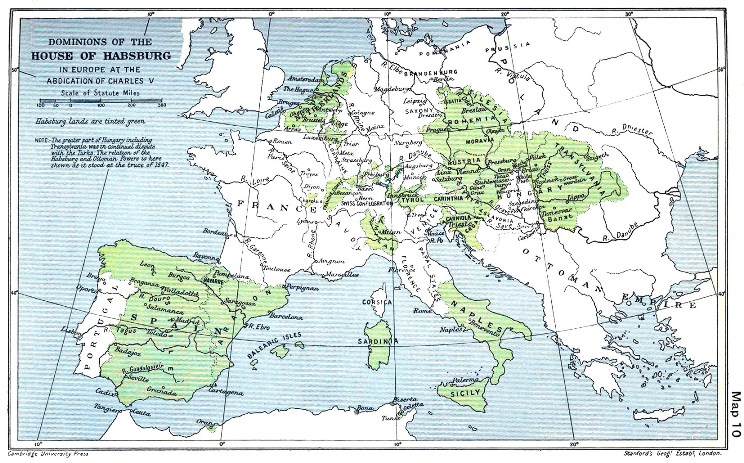

Although Charles tried to bequeath everything to Philip, the German princes were more impressed by Ferdinand's performance against the best armies of Islam, so they insisted on making Ferdinand the next emperor. What this meant was that the Hapsburg realm would now be permanently divided. Spain, her overseas colonies, Italy, Burgundy and the Low Countries would pass to Philip and his descendants (now called the Spanish Hapsburgs), but the Hapsburg lands within the central and eastern parts of the Empire, along with the imperial crown, would belong to Ferdinand and his descendants, henceforth to be known as the Austrian Hapsburgs. Both halves continued to cooperate as long as a Hapsburg monarch ruled each, and each was in pretty good shape at this point, but now they would stop trying to unite Christendom. It was probably just as well, because it is unlikely that France or England would have stood for letting so much of Europe pass into the hands of a ruler with real ability.(15)

Revolts in France and the Netherlands

The last war between Hapsburg and Valois finally came to an end in 1559, with the treaty of Cateau-Cambresis. By this time, both Francis and Charles were dead, and their countries were exhausted. According to the treaty, France won the right to put garrisons on the other side of the upper Moselle River (at Metz, Toul and Verdun). Henry II, the son of Francis, had to give up most of his claims to Italy, but got to keep Saluzzo, a territory taken from Savoy, as well as Calais, England's last port on the French side of the Channel. For the next seventy-five years, the French stayed home; they couldn't have gotten involved in foreign conflicts if they wanted to. From the 1580s to the 1640s, there were no less than 500 uprisings in France, most of them caused by religion or the poverty of the lower classes. Henry II died in a jousting match in 1559; during the next thirty years, three sickly grandsons of Francis (Francis II, Charles IX, and Henry III) sat on the throne, while the real ruler was the queen mother, Catherine di Medici. They faced opposition from the Huguenots (French Protestants), who offset their lack of numbers with their wealth and education.

Most monarchs would have either defeated the Huguenot minority, or reached an agreement with it; the kings of France did neither. Catherine de Medici tried to bring peace by marrying her daughter Margaret to Henry of Navarre, the Huguenots' champion. Instead it caused one of the bloodiest disasters in an age famous for them: the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre. When thousands of Huguenots gathered in Paris to celebrate the wedding, Catherine apparently had a change of heart; she dropped a hint to her son, Charles IX, that this would be a great opportunity to kill the Huguenot leaders, now that they were all in one place. Word of this got to the people of the city, and when church bells rang on the morning of August 24, 1572, the mobs of Paris rose up and slew every Protestant they could find. When the massacre ended, two thousand were dead in Paris, and at least ten thousand in all of France.

After the massacre, Catherine de Medici went out to see the work of the killers.

Philip II of Spain had to share his father's empire with his relatives in Austria, but if he missed the pieces they got, he did not do so for long. Six years after becoming king (1564), a squadron of Spanish ships left Mexico to conquer the islands named after him on the other side of the Pacific -- the Philippines. By 1571 his force in the Philippines had taken Manila, giving Spain an excellent base in the Far East. Then in 1580 Philip also became king of Portugal (we'll explain how Philip did that at the end of the next section). Thus, besides the vast landholdings and wealth that the Spanish Empire already gave him, he also had access to the lumber and sugar cane of Brazil, and the gold, ivory and slaves of Africa; he also had a foothold in the Spice Islands of Indonesia, and a profitable trade network that extended to India, China and Japan. Because this empire was scattered across the northern, southern, eastern and western hemispheres of the world, it was truly an empire on which the sun never set. Offsetting all these assets was Philip's talent for making enemies. Among his opponents, the most persistent -- and the most successful -- were his own subjects, in the seventeen provinces of the northern Netherlands.

In times past, the Netherlands was a part of the Holy Roman Empire that combined Low German and Latin customs. We saw in the previous chapter how changes of dynasty had caused it to end up first in Burgundian, and then in Hapsburg hands. By the sixteenth century, a Dutch language and culture had emerged, and the Dutch were starting to develop a national identity of their own; this process was speeded up when they converted to Calvinism, and the kings of Spain persecuted them for it.

Though Philip's father and grandfather had come from the Low Countries, Philip was Spanish-born and never could get along with the Dutch. He had little tolerance for either religious or political freedom, while the Dutch had come to cherish both; he also disliked Dutch capitalism, which gave few privileges to the traditional ruling class. Thus he felt it quite proper to send in the Inquisition, and raise Dutch taxes to pay for his wars. The Dutch had kept quiet about acts of intolerance from Charles V, because they viewed him as one of themselves; by contrast, all Philip seemed to offer was unenlightened rule from a distant capital. His heavy-handedness may have worked in Spain, by bringing dissident areas like Aragon back into line, but here it led to minor uprisings as early as 1562, in Flanders and Brabant.

Philip first placed the Netherlands under his half-sister, Margaret of Parma, who like her father, was a native of the region. She was an able administrator, and popular because she understood her subjects. Philip wasted this asset by ordering her to combat heresy, whereas she did not object to Protestant preaching. By 1566 there was widespread civil disobedience, from both Catholics and Calvinists. The Dutch felt strongly about their constitutional rights but Philip would not negotiate; he ignored Margaret's frantic appeals for leniency, and finally recalled her. In her place he appointed the Duke of Alva, a leader already known for his enjoyment of religious wars. The new governor marched up from Italy with 10,000 Spanish troops, a great baggage train, and 2,000 prostitutes; his orders told him to root out both heresy and the liberties of the land. Alva's reign of terror killed 18,000, but his rule of iron produced a soul of iron in the people he tried to suppress.

In 1568 the two coastal provinces of Holland and Zeeland revolted. The Dutch raised a force of guerrillas and pirates, because they did not have a conventional army to face Alva's. They won the first battle of the war at Heiligerles, but lost the second at Jemmingen. Now the rebels fled to England and Germany, and survived by attacking Spanish shipping. England's Queen Elizabeth I, under pressure from Philip, expelled the "Sea Beggars" from English ports in 1572. To everyone's surprise, they sailed home, captured the port of Brielle (1572), and succeeded in regaining control over Holland and Zeeland. A noble from Nassau named William the Silent, Prince of Orange, was elected to lead the rebellion.

Philip and Alva did not expect the Dutch to make an ally out of the enemy they had been fighting for centuries--the sea. Half of the Netherlands is below sea level, having been reclaimed from the North Sea in a very long-term project. Since about 1200, the Dutch had been building dikes around tracts of potential land called polders, using windmills to pump the water out. In 1573 they decided to flood the country, but first they had to get the consent of the people whose crops and livestock would be lost. A carpenter named Peter Van der Mey left Alkmaar, a town north of Haarlem, carrying a message that authorized the opening of the sluice gates. Meanwhile the Spanish army approached. Alva made this chilling promise in a letter to Philip: "If I take Alkmaar, I am resolved not to leave a single creature alive; the knife shall be put to every throat." He thought his regiments were unstoppable, but every living man in Alkmaar got on the walls to resist. For four hours they fought back every assault fiercely, with only the dead and wounded leaving their posts. When the Spaniards withdrew, they had lost 1,000 men, while the Dutch had lost only 37. One Spanish officer named Ensign Solis briefly stood on the battlements before the Dutch threw him off. By some miracle he survived, and reported that while he was up there, he looked down and saw "neither helmet nor harness" among the defenders of Alkmaar. A group of very ordinary-looking people, mostly dressed like fishermen, had defeated the veterans of Alva.

About this time, the land started getting wet; the carpenter-envoy had completed his mission. Among the messages he brought back was a promise from William of Orange to drown the Spanish army. In town he lost the dispatches, and they fell into Alva's hands. Whether or not he meant to do this, it had the desired effect; the Spaniards couldn't stop the sea's advance and immediately abandoned the territory.

Spain recalled Alva after this. The Spanish army continued to win easy victories on any formal battlefield, but could not take the last rebel strongholds. The tide turned suddenly in the rebels' favor in 1576, when the Spanish government went bankrupt, and unpaid soldiers started plundering Antwerp and Ghent, causing Flanders to join the rebellion. A more politically sensitive governor, Alexander Farnese, the Duke of Parma, took charge in 1578, and he used troops from the provinces still under his control to take part in the pacification of Ghent. Once finished, he enrolled the French-speaking, southern Catholic provinces (Wallonia) in the Union of Arras, promising not to trample on their liberties anymore. In response, seven rebel-held provinces in the north formed the Union of Utrecht, and proclaimed themselves the United Provinces (1579). Even at this point, the rebels would have accepted Philip as their king in return for guarantees of religious toleration and civil liberty, but very few people beyond the Netherlands were ready for a limited monarchy. Philip certainly wasn't, so the United Provinces declared independence in 1581. For their government they chose a republic, with William of Orange as its first stadtholder (general).

The Spanish Armada

Philip II rejected the Dutch declaration of independence, and when Parma brought up another army from Italy, the war resumed. This time the new nation suffered a series of reverses, the worst being the assassination of William of Orange by a Spanish agent in 1584. William's son, Maurice of Nassau, became the new stadtholder, while Johan Van Oldenbarnevelt took charge of the civilian government. Soon Parma had recovered Flanders and Brabant, forcing the Dutch to move their capital to The Hague. This alarmed the English; with Italy and Portugal under Spanish rule, the Dutch besieged, and the throne of France up for grabs, it was beginning to look like Spain would become the ruler of all western Europe. In 1585 Queen Elizabeth began sending the Dutch the military aid they needed. By this time, Philip had several reasons to be mad at the English. Besides the support given to the enemy, English raiders like Sir Francis Drake were harassing Spanish shipping overseas; Elizabeth had rejected a marriage offer from Philip; the pope had declared Elizabeth a heretic in 1570, giving all good Catholics permission to get rid of her. Philip now made the most fateful decision of the war; he began preparing for an invasion of England, figuring that he would have to conquer the English before he could crush the Dutch revolt. In response, Elizabeth ordered the beheading of Mary Stuart (also called Mary Queen of Scots), the highest-ranking Catholic in the British Isles, on a charge of plotting to kill Elizabeth.

Spain assembled an enormous fleet for this enterprise: 130 ships, carrying 28,000 men. The original plan called for the celebrated "Spanish Armada" to sail in 1587, but a pre-emptive raid by Sir Francis Drake on the fleet in Cadiz delayed departure for a year, giving England that much more time to prepare defenses at home. The Armada, now relocated to Lisbon, was finally ready to go in May of 1588; Parma and his force moved to the port of Dunkirk, expecting to be ferried across the Channel. The leader of the expedition, Alonzo Perez de Guzman, the Duke of Medina-Sidonia, had no naval experience, but he was confident his fleet could overcome anything. Little effort was made to keep the expedition a secret, so the English got ready by assembling 197 smaller vessels, only thirty-six of which had been in the Royal Navy previously.

Bad weather forced the Armada into the port of La Coruna on Spain's northwest coast, where it waited until late July. On July 29, the English sighted the Armada off Cornwall. For the next week, Lord Charles Howard, the English fleet commander, battled the Spanish ships off Plymouth, Portland Bill, and the Isle of Wight. The English had an easier time in their more maneuverable ships, and their gunners had better cannon and superior training, allowing them to fire as many as ten shots for every shot the Spaniards got off. Even so, the English were unable to break the Spanish formation. What happened next was best described in some letters recently found in Scotland, written by a deputy of Medina-Sidonia, Juan Martinez de Recalde. Recalde urged Medina-Sidonia to blockade the English in Plymouth harbour, because that would leave the rest of England wide open to invasion. Instead, the duke insisted on following the king's orders, by going on to pick up Parma; thus Spain's best opportunity was lost. Recalde also criticised his leader for abandoning the flagship Rosario after it was crippled in battle, an action which caused a dramatic fall in morale.

After sailing past Plymouth, the Armada again came under attack from Drake's ships. Finally it dropped anchor near Calais, where it waited for Parma. This time England had the opportunity, and Lord Howard went for it. On the night of August 7, he loaded eight unmanned ships with explosives and guns, which would go off when the heat reached them, and sent these "fire ships" into the Spanish formation. It worked; panicked Spanish captains ordered their anchors cut loose, causing them to run aground or drift away from the fleet. The remaining ships were devastated by the English in the nine-hour battle of Gravelines, fought the next day.

Battered by a fierce storm (the "Protestant wind") and the English, the Armada was swept into the North Sea. The survivors could only get home by sailing all the way around Scotland and Ireland, and they left 25 wrecks on the Irish shore. Just 67 of the original 130 ships made it back to Spain. Upon his return, Recalde sent a damning report on the expedition to Philip II, who wrote: "I have read it all, although I would rather not have done, because it hurts so much."

The story of the Spanish Armada goes down in all history books as a key event, because it marks a dramatic end to the age when Spain was supreme on the seas, although a century of competition between England, France and the Netherlands followed before anyone could take Spain's place. King Philip lived for ten more years after the debacle, but we only hear of halfhearted interventions in the affairs of France. Moreover, an unofficial ceasefire settled upon the Netherlands, broken only by a Dutch victory at Nieuwpoort (1600), and a Spanish one at Ostend, which involved a siege lasting from 1601 to 1604. In 1609 both sides agreed to a formal truce, which lasted for twelve years.

Philip failed to strike a critical blow against those he saw as heretics, but he did better against pagans, Moslems, and (ironically) other Catholics. In 1564 a squadron from Mexico sailed across the Pacific, took Guam, and began the conquest of the Philippines (1565-71), which had already been named after you-know-who. Meanwhile in the Mediterranean, the Turks took Cyprus from the Venetians (1570), and one year later a fleet of Spanish and Italian ships struck back with a fine victory at Lepanto. This battle had the same effect on the Ottoman Empire as the battle of the Armada had on Spain--it marked the beginning of a long Turkish decline. However, Philip didn't follow this up; the Turks got to keep Cyprus, and even took Tunis from Spain in 1574. This completed the Turkish conquest of North Africa, except for Morocco.

As for Morocco, Portugal's King Sebastian tried to conquer it in 1578, finishing the job the Portuguese started in the previous century. Instead, he was killed in the battle of Alcazar el Kebir. The ruling dynasty of Portugal abruptly became extinct, and since Philip was an in-law of the dead king, he claimed the Portuguese throne. Naturally the Portuguese people resented this, so Philip sent in the cruel Duke of Alva. By 1581 the whole country was firmly under Spanish control. Thus, Philip's most important accomplishments were not ones he wanted to be remembered for: the creation of an independent, Protestant Netherlands, and the crippling of both the Spanish and Portuguese empires.

Merrie Olde England

When Henry Tudor became king of England in 1485, he put on the crown of a country that had been at war for most of the previous century and a half. We don't hear as much from Henry VII as we do from his successors, because the nation needed time to recover, so while he was king (1485-1509), the English stayed home, doing just that. Avoiding wars turned out to be the easiest way to save money, too. In the two centuries since it was established, Parliament had become the branch of government in charge of raising revenue, but Henry only called Parliament seven times during his twenty-four-year reign, and then it only met for a total of ten and a half months, long enough to levy taxes, but not long enough to make trouble for the king. His main challenge came from a few pretenders who thought they could take the crown for themselves; fortunately for Henry, the army was on his side, so all he had to do was arrest and execute them. Then as a precaution, he used the power of the Church, by getting the pope to draw up a blanket bull of excommunication against any future claimants. Thus, under Henry VII, Parliament's influence was at a low ebb; to someone living back then it must have looked like England was going back to the absolute monarchy it had before the Magna Carta.

Henry's eldest son Arthur died of an unspecified illness before he did, so his second son became the next king, Henry VIII (1509-47). This Henry alternated between an anti-French and an anti-Spanish policy, but otherwise he didn't involve himself much in affairs on the Continent. Since he had inherited a poor country, he also stayed out of wars most of the time (except when Scotland attacked, which happened twice during his reign); executing opponents and confiscating their estates helped balance the budget, too.(16) Henry was able to rule autocratically because he was the first English king in a long time who came to the throne without the danger of a rebellion.

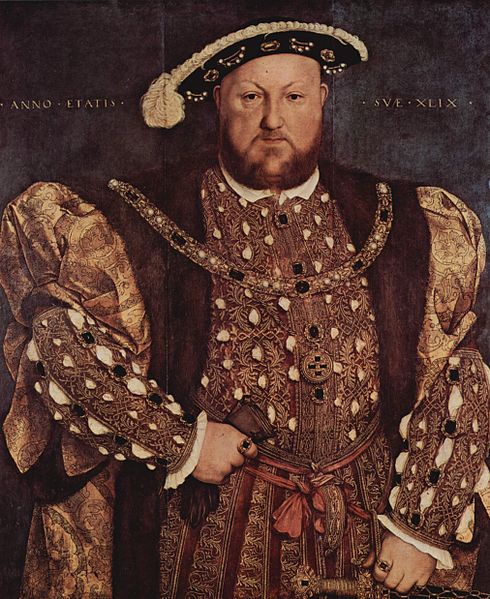

Henry VIII, painted by Hans Holbein the Younger.(17)

Besides creating the Church of England, as we noted in the section on the Reformation, Henry VIII is mainly known because he had six wives, and beheaded two of them. We already saw that his first and longest marriage, to Catherine of Aragon, ended in divorce. The next wife, Anne Boleyn, had another daughter, Elizabeth, but then Henry tired of her, and in 1536 she was executed on a charge of adultery. Wife number three, Jane Seymour, finally gave him a son, Edward, only to die of complications twelve days after Edward's birth. Next he chose a German princess, Anne of Cleves, to show his solidarity with Protestants on the Continent. It was a failure from the start; neither Henry nor Anne was fluent in each other's language, they got along badly at the first meeting, and though a treaty forced him to go ahead with the wedding, Henry began looking for a divorce immediately afterwards. He got one six months later, but the next bride, Catherine Howard, didn't last much longer; eighteen months after their wedding she was executed, also on a charge of adultery. Finally, he married Catherine Parr in 1543. This marriage was happier than the others; at least she outlived him.

Henry's will made Edward VI his heir, and stated that if Edward had no children, the crown would pass next to Mary, and then to Elizabeth. That is exactly what happened. Edward was too sickly to do much as king, and died of tuberculosis in 1553.(18) Mary was too much like her mother; not only was she a loyal Catholic, she also dragged England back into Continental entanglements by marrying Spain's Philip II. She earned the nickname "Bloody Mary" by burning 280 Protestants as heretics; 500 more went into exile to keep their faith. The rest of England officially recanted, but afterwards showed only the slightest evidence of any conversion. To prevent an organized Protestant uprising, she briefly imprisoned her Protestant sister Elizabeth, then put her under house arrest; during this tough time, Elizabeth's courage and political instincts kept her from saying anything that might have sent her to the block, so she avoided the fate of her mother. In 1558 Mary died childless, and many Englishmen saw her replacement by Elizabeth as an answer to their prayers.

Mary Tudor.

Elizabeth I (1558-1603) was the last and most successful of the Tudors. Her reign (the first in English history that involved a long-lived, competent, female ruler) saw so much prosperity and cultural achievement, that we now refer to it as the "Elizabethan Age." In the Middle Ages, English kings saw themselves as arch-rivals to the kings of France; that ended when England lost the Hundred Years War, but the early Tudors couldn't find a new role to replace the old one. It was Elizabeth who established the national policy for England, one that has been followed to this day: build an empire overseas, and don't let any nation on the Continent gain enough power to threaten the rest. Maintaining the balance of power is tougher than submission, and often the English have found themselves alone in opposing would-be world emperors, but because they didn't back down, they have saved countless lives from tyrants like Philip II, Louis XIV, Napoleon, Hitler, and the Soviet Union. Accordingly, she reversed Mary's pro-Spanish policy (Mary had supported Spain in the last Hapsburg-Valois war against France), though it meant an alliance with France and a war with Philip. It worked because the English navy, founded by Henry VIII, grew steadily under Elizabeth, and even before the defeat of the Armada, the Spanish and Portuguese empires were tempting targets for privateers. Some exploration took place while Elizabeth was queen, but the real fruits of a seagoing empire would be harvested by future monarchs; the first English colony in North America (Roanoke), for example, failed in less than five years. In 1600 she granted the English East India Company a monopoly on trade with the countries around the Indian Ocean, the first step toward economic competition with the other new naval power, the Dutch.

Elizabeth I.

Elizabeth made England's conversion to Protestantism permanent, but the Puritans were too extremist for her tastes, so like Henry VIII, she went for a middle-of-the-road church, by passing the Act of Uniformity in 1559 and the Thirty-Nine Articles in 1563. Her religious policy also solved England's problem with Scotland. We saw previously that the English and the Scots didn't get along very well; a Scottish alliance with France was often used to keep England from defeating either of those opponents. Elizabeth won the friendship of the Scots by giving her support to the Protestant movement that sprung up there, the Presbyterian Church of John Knox.(19) Ironically, her personal life worked toward this; she never married or had any children, and on her deathbed she named the king of Scotland as her heir, stating that no one but a king should succeed her. Thus England and Scotland were united under King James I (1603-24).

James I got the Stuart dynasty off to a bad start. He believed strongly in the divine right of kings, at a time when members of Parliament were starting to think otherwise. Queen Elizabeth could make Parliament think it was ruling when in fact it was doing what she wanted, but James did not have the skills or charm to do this. An early warning of his disregard for the law came right at the beginning of his reign, on his way from Edinburgh to London; a man accused of theft was brought before the king, and James ordered him hanged immediately without trial. And while he was convinced that his policies were correct, he was too weak to carry them out; he was rigid where he should have been flexible, and vice versa.

James I.

Parliament's power came from the fact that it controlled the purse strings of England; it could levy taxes and the king couldn't. This would have made a more sensible king listen closely to its grievances, for James was on a fixed income that could no longer pay his expenses; Queen Elizabeth had sold some of the crown lands to pay her debts, and inflation had reduced the value of the rest. Every time the king asked Parliament for money, Parliament wanted concessions in return, so its power increased as long as the crown was financially insolvent.

Though James gave us the King James Bible, which was considered the last word in English translations of the Scriptures for the next three hundred years, he didn't care much for Protestants who took the Scriptures seriously, like the Puritans. Insisting on his royal prerogatives as head of both Church and state, he passed laws requiring that everyone in England conform to the Church of England. "No bishop, no king" was how he explained it, viewing the Church as indispensable to enforcing his authority. In 1607 the Separatist faction of the Puritans decided they couldn't take any more of this, so they sailed to the Netherlands. Here they could practice their faith freely, since Amsterdam was the most tolerant city in Europe. However, a few years later they realized that if they stayed, their children would grow up to be Dutch, and they would have to serve in the Dutch army (we are now up to the Thirty Years War, and the Dutch were still fighting for their independence from Spain). So in 1620 they pulled up roots again, chartered an English ship, the Mayflower, and sailed across the Atlantic, becoming the Pilgrim Fathers of colonial America.

Despite the derision of less committed Englishmen, and the royal measures taken against them, the Puritans were very influential. Like other Calvinists, they believed that a person can prove his fitness for salvation by being law-abiding, industrious, sober and thrifty, so they prospered in the new capitalist society of England. As they made their way into the House of Commons, their sober and responsible behavior imprinted itself on English society. These are the same qualities that would soon tame the American wilderness.

Sweden Returns to the Stage

Sweden prospered in the days of the Vikings, but more recently it was a poor backwater. During the period of the Union of Kalmar (see Chapter 9), control of the Swedish government alternated between pro-Danish and pro-German factions; the former wanted to remain under Danish rule, while the latter sought to win independence with the help of the Hanseatic League. This went on until 1520, when King Christian II of Denmark invaded Sweden to enforce his authority. While at Stockholm, he massacred so many opponents that he earned the nickname "Christian the Tyrant," and the whole country turned against him. Thus, the rebellion he tried to prevent erupted anyway, led by Gustavus Eriksson Vasa. The rebels quickly triumphed, and in 1523 Gustavus was crowned king of Sweden. Denmark, however, retained possession of the southern tip of the peninsula.

For Gustavus, the recovery of the country had to come first, but he also managed a successful foreign policy. In 1527 he announced his conversion to Lutheranism, allowing him, like the princes of northern Germany, to become leader of his country's churches and take the lands owned by the Church. This gave the treasury a needed shot in the arm, and ended Sweden's dependence on the Hanseatic League. In 1531, Jürgen Wullenweyer, the mayor of Lübeck, declared that the latest payment of Sweden's debt to the League was insufficient, and confiscated a Swedish ship. The Swedes joined Denmark in the war that broke the power of the League (1531-36); as a result the League removed and executed Wullenweyer, and the treaty ending the war canceled the huge debt Sweden had run up in the struggle for independence.

Gustavus wrote a will that declared his eldest son, Erik XIV, the next king, but left so much land to the other three sons that they couldn't resist making trouble. Erik was mentally unstable, and his brother John, the Duke of Finland, used that as an excuse to revolt in 1562. Denmark invaded, too, figuring that the Swedes had been independent long enough. The Danes did well on the battlefield, but were unable to hold any captured territory. In the east, John was able to survive the loss of his capital, Abo, and because the king of Poland was his brother-in-law, he had Polish help. In 1568 he marched on Stockholm, captured it after a siege, and imprisoned Erik. As King John III, he signed a treaty with Denmark that confirmed Swedish independence, and joined Poland in the long but successful Livonian War (1557-82), which prevented the Russians from conquering the east shore of the Baltic and won Estonia for Sweden.

John's son, Sigismund, had been elected king of Poland in 1587, five years before becoming king of Sweden, so under him the Poles and Swedes were briefly united under one crown. However, both John and Sigismund were Catholics, and their pro-Catholic policies were unpopular among their now-Protestant subjects. A Protestant revolt broke out; Sigismund was defeated at the battle of Stangebro and deposed by the Swedish parliament. He managed to keep Poland, where his branch of the Vasa dynasty provided rulers until 1668, but Sweden itself went to Charles IX (1604-11), another son of Gustavus Vasa. Charles was in turn succeeded by his son Gustavus Adolphus, the greatest king in Swedish history.

Gustavus Adolphus began his reign with some formidable challenges; he was only seventeen years old, and Sweden was at war with all three of its neighbors. A few months before his death, Charles IX had picked a fight with Denmark's Christian IV over Lapland, while in the east, Poland and Sweden had been scuffling over Livonia and Estonia since 1600, with the Poles doing most of the winning. The third opponent, Russia, was in a state of anarchy, the so-called "Time of Troubles,"(20) so strategy dictated that Gustavus beat up the Russians and make peace with the others. Poland quickly agreed to a truce, since Sigismund was busy trying to put his son Wladislaw on the the vacant throne in Moscow. In 1613 he ended the "Kalmar War" with Denmark; the Danes had won every battle that mattered, but instead of taking any Swedish territory, Christian accepted a treaty that recognized Danish rule over Finnmark (the northernmost province of present-day Norway), and promised to return the port of Alvsborg in exchange for 400,000 ducats. This ransom was twice as much as Sweden's annual revenue, but fortunately for Gustavus, he was bringing home loot from the Russian campaign, and the value of Sweden's iron and copper exports was increasing, so he managed to pay it off in four years. On the Russian front, Gustavus captured Novgorod, and continued to do well even after the Russians got a new tsar in 1613. In the treaty ending that war (Stolbovo, 1617), Sweden gave back Novgorod but gained Ingria, the land between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga. Russia was now shut out from the Baltic--at least until the time of Peter the Great. We will be hearing more from Gustavus Adolphus in the next chapter of this work.

How to Elect a King

I've said it elsewhere, but the problem with hereditary monarchies is that you have to take whatever the royal family gives you, even if the monarch is inbred.(21) A few nations, like the Holy Roman Empire, voted for kings instead, in effect making the head of state an elected president for life. The result has been that politics, rather than genetics, decided who would be the next ruler. The experience Poland went through when she first tried this may explain why royal elections don't happen very often.

The Polish royal family, the Jagiellonians, became extinct in 1572. Instead of fighting over who would rule next, the Polish nobility decided to hold an election among its members to choose a new king. Any prince in Europe was elegible to run, so several kings sent their unemployed relatives to Warsaw. Some Polish candidates also ran, but the nobility didn't trust them, so the race was dominated by five foreigners: Henri Valois, the Duke of Anjou and brother of King Charles IX of France; Archduke Ernest, the younger son of Austria's Maximilian II; Russia's Ivan the Terrible; Sweden's John III; and Prince Stephen Bathory of Transylvania.

Henry Valois, known to history books as Henry III, didn't have much in the way of character to recommend him; his main interests were entertainment and expensive fashions, and Charles may have nominated him just to get him out of France. Moreover, this was when France's religious wars were taking place, and though the Poles were devout Catholics, they didn't care for the idea of having a king from the family responsible for the St. Bartholomew Day's Massacre. However, Henry also had Jean de Montluc, the bishop of Valence, as his campaign manager. This shrewd character was just the man for the job. First he explained to the Poles that Henry wasn't really immature, and he told so many contradictory stories about the fighting in France that everyone was left confused by the whole business. To keep track of what the other princes were up to, he bribed their secretaries for inside information, all the while making sure that nobody paid his own assistants for the same knowledge about Henry. Finally, he used the printing press to his advantage, in a country that didn't have printing presses yet. While the other candidates were copying their ideas by hand, Montluc printed and gave out 1,500 copies of Henry's campaign speech, nearly fifty times as many as each opponent could produce.

In the last days of the campaign, the two leading candidates were Henry and King John of Sweden. The decisive moment came when a crowd gathered in an enormous tent to hear the Swedish ambassador give a final speech in favor of his king. Suddenly the tent collapsed in the middle of the speech. Many thought that Montluc had cut the tent ropes; whether or not he did, few Poles could take the Swedes seriously after that, and Henry won the election.

He might as well have never run. A year later Charles IX died, and Henry deserted Poland, deciding that he would rather be the king of France. Thus, the Poles needed another election already. This time they voted for Stephen Bathory the Transylvanian (1575-86), and he proved to be a better ruler; he strengthened the army by adding Cossack units, and waged three successful campaigns against Ivan the Terrible.

As for Henry III, he was the weak and wasteful ruler people expected, who dressed like a woman until he earned the nickname "the King of Sodom." The war between Catholics and Huguenots continued, and Henry could do little to stop it. Instead, he tried to straddle the fence between the two sides, first by making concessions to the Protestants, then by throwing his support behind the main Catholic army, the Holy League. Eventually the Catholics became the greatest threat to him, so the childless Henry made the Huguenot leader, Henry of Navarre, his successor. In response, the Holy League launched a revolt against the two Henrys. Henry III arranged for the assassination of the Holy League's leader, Henri de Lorraine, as well as his brother Louis de Lorraine, but one year later Henry himself was stabbed by a fanatical Dominican friar (1589).

Henry's death meant the extinction of the Valois dynasty. Now the Huguenots controlled one third of the country; they defeated Spain when the Duke of Parma intervened, and Henry of Navarre had the best claim to the crown. French Catholics recognized Henry's legitimacy, but they did not want a Huguenot for their king. They threatened to continue the war, with outside help if necessary, if he tried to be both king and Protestant, so in 1593 Henry settled the matter by converting. "Paris is worth a Mass," is what he supposedly said, before he rode to Paris as King Henry IV. This is not as cynical as it sounds; Henry's foremost concern was bringing peace to the country, and if that meant becoming a Catholic, so be it. He spent the next four years evicting the Spaniards, who tried to put a pretender on the Spanish throne, but he didn't forget his Huguenot comrades. When the war ended he passed the Edict of Nantes, which promised equality and complete freedom of religion for the Huguenots (1598).

Henry IV was blessed with an excellent finance minister, Maximilien de Bethune, the Duke of Sully. Sully put the government's spending in order, promoted trade, built roads and bridges, and encouraged practices which made French agriculture more efficient. When James I became king of England, Sully served briefly as ambassador, and remarked that James was "the most learned fool in Christendom." Because of all that Sully did, the country recovered quickly, and by 1610 it had the first balanced budget and treasury surplus in years. Sully opposed colonial ventures, but here Henry overruled him and had Samuel Champlain found the first permanent French colony in the Americas (Quebec, 1608).

Because of the need for recovery, Henry wasn't very active in foreign affairs, though French policy remained the same: weaken the power of Spain and Austria, and form an alliance with any nation wanting to do the same. He did fight a brief war with Savoy in 1601, taking the upper Rhone valley because Savoy had taken Saluzzo a few years earlier. If he had lived longer, he probably would have gone after a Spanish-held territory on his frontier, either Burgundy or the Spanish Netherlands (modern Belgium). It didn't happen because he was assassinated in 1610; the killer was a Catholic fanatic, and may have been a Hapsburg agent. In life Henry was called a heretic by many Frenchmen, but since his death he has been known as "good King Henry," one of the best-loved French kings. With Henry gone, the process of centralizing France stopped for many years. Sully resigned because he couldn't get along with France's bad-tempered nobility, and Henry's son, Louis XIII, was only nine years old, so his mother, Marie de Medici, ruled as regent until 1617.

This is the End of Chapter 10.

FOOTNOTES

13. When England declared itself Protestant, King Henry VIII ordered the destruction of all relics in the country's churches and monasteries. His men found enough pieces of the True Cross to fill three wagons!

14. For a more detailed description of the Reformation, read Chapter 5 of my history of Christianity.

15. It is worth remembering that just about all the Hapsburg victories achieved under Charles V were defensive ones. For example, he had France surrounded on the north, east and south, but never conquered even the smallest piece of it.

16. There was a notable episode in 1520, when Henry went to France to sign a treaty with Francis I. The participants camped in tents and staged seventeen days of medieval-style tournaments, in a festival so grand that the event was later called the Field of Cloth of Gold (the largest tent was made of gold and silk). Because England and France had been enemies quite often over the past few centuries, this party became a contest where Henry and Francis tried to outdo each other in how much food, wine and entertainment they could provide, as if this was a European potlatch; they ended up draining the treasuries of both countries. Unfortunately, it ended abruptly with no treaty to show for the expense. When Henry challenged Francis to a wrestling match and Francis beat him, an upset Henry left the party. Over the next few weeks Henry forged an alliance with Spain's Charles V, Charles declared war on Francis, and Henry was compelled by the alliance to join Charles, so one month after the Field of Cloth of Gold, all three monarchs were at war.

17. We usually think of Henry VIII as a pudding-face, so remember that the Holbein portrait was done in 1537, when he was forty-six years old, and had been king for twenty-eight of those years. During the early years of his reign he was a hunk, not a chunk; we have his armor to prove it (see below, this picture also appeared in the previous chapter). That is why, when the Showtime Network ran a TV series on Henry VIII ("The Tudors"), they could choose an actor for the lead role who did not look anything like the Holbein portrait.

18. Did I say the succession went from Edward to Mary to Elizabeth? Well, there was a brief interruption. A powerful noble at Edward's court, the Duke of Northumberland, married his son, Guildford Dudley, to the king's teenage cousin, Lady Jane Grey. When Edward was on his deathbed, he wrote a new will that gave the crown to Jane, instead of Mary. Northumberland probably persuaded him to do this, to keep the crown out of Catholic hands and to give his son a chance to become king. Upon Edward's death Jane Grey moved to the Tower of London, to await coronation, while Mary went to East Anglia to raise an army. The late king's advisors, the Privy Council, recognized Mary as the rightful heir; that and popular support allowed Mary to enter London without resistance. Thus, Jane was queen for only nine days, and because she was now a prisoner, she never left the Tower of London after entering it. Mary had Jane and her husband put on trial for high treason, and both were sentenced to death, but the sentence was suspended. Then in January 1554, a minor Protestant rebellion broke out; Jane had no part in it, but it gave Mary the excuse she needed to have Jane and her husband beheaded. You can read more about Lady Jane Grey on this factsheet from Historic Royal Palaces.

19. However, the Irish remained Catholic, giving Englishmen and Irishmen one more reason to hate each other. During the fifteenth century, the part of Ireland under English rule ("The Pale") shrank to a small area around Dublin. Henry VIII enlarged the Pale to include all of Leinster, and by the end of Elizabeth's reign, English rule had been imposed, more or less, over the whole island.

20. "The Time of Troubles" was a generation of weak rule, civil war and foreign invasion, beginning with the death of Ivan the Terrible in 1584 and ending with the crowning of Michael Romanov in 1613. For details, read Chapter 3 of my Russian history.

21. Philip II's eldest son, Don Carlos of Spain, was born before Philip became king. Today Don Carlos is mainly remembered as the hero of an opera by Verdi, but while he lived, he was an argument against government by hereditary monarchy. He was also an argument against inbreeding, because the Hapsburgs misunderstood the expression "keep it in the family." Whereas most people have eight great-grandparents, Don Carlos only had four, thanks to the Hapsburg fondness for incest. Even worse, the two female great-grandparents were sisters, and one of them was Joanna the Mad; need I say more? Finally the delivery of Don Carlos was so difficult that his mother only lived for four days after his birth.

Besides the usual defects associated with the Hapsburgs--an ugly face and low intelligence--he was a hunchback, pigeon-breasted and his right leg was shorter than his left leg. Still, he might have become king if his ailments were only physical, but he was also violent-tempered, and had a cruel, sadistic streak. Even as a baby, Don Carlos was rumored to have bitten the breasts of his wet-nurses, nearly killing three of them. Later his idea of having fun was to abuse animals, children and servants--this has prompted modern historians to call him "the prince who beat little girls." The worst incident along this line was the time when he went into the royal stables and mutilated the horses so badly that twenty had to be destroyed.

Don Carlos fell down some stairs and cracked his head open in 1562. He nearly died from this injury; a surgeon trepanned his skull, King Philip prayed over him, and the body of Father Diego de San Nicolás del Puerto, a Franciscan saint who had died ninety-nine years earlier, was brought out of his coffin and put in bed next to the prince. That night Don Carlos had a dream about Diego, and then recovered afterwards. His temperament did not improve, though. The only thing Don Carlos liked to do with females was whip them, which ruled out any chance that he might have children of his own. In January 1568 he was accused of plotting to kill his father, and Philip locked him up. There in solitary confinement, he died six months later, at the age of twenty-three. The official announcement was a brief statement that the heir to the throne had "died of his own excesses." Philip showed he hadn't learned anything from his family life, because in 1570 he married his niece, the Archduchess Anna of Austria. This was the first in a new string of incestuous marriages that eventually produced another monstrosity--King Charles II of Spain. We'll see him in the next chapter.

Support this site!

PAGE NAVIGATOR

A History of Europe

|

Other History Papers |

Beyond History

|