| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A General History of the Middle East

Chapter 11: SARACEN AND CRUSADER

1055 to 1212

This chapter covers the following topics:

Alp Arslan

Shortly after taking Baghdad, Tughril-Beg left to quell a cousin's revolt in the northern Iranian city of Rai. Provoked by the excesses of the undisciplined Turkish soldiers, the population of Baghdad transferred their loyalty back to the Buwayhid general, Besasiri. Besasiri declared the Abbasid caliph deposed and sent the symbols of his office, including Mohammed's sacred cloak, to the Fatimid caliph in Egypt; then a Fatimid army from Syria arrived to back him up. This was only a temporary reverse for Tughril-Beg; in 1059 he put down the Rai rebellion, fought his way back to Baghdad, killed Besasiri, and restored the Abbasid caliph to his figurehead role. In payment for his services, he demanded one of the caliph's daughters in marriage, but on the eve of the ceremony in 1063, he died of a hemorrhage, leaving no children.

At once a struggle broke out among the Seljuks to fill the power vacuum. The winner was Tughril-Beg's nephew, Alp Arslan ("Heroic Lion"), who had governed the eastern provinces since the death of his father, Chaghri-Beg, in 1061. The rivals, who had included his cousin Kutulmush and Chaghri-Beg's vizier, were duly dispatched, and Alp Arslan replaced them with a vizier so competent that people always called him by his title, Nizam al-Mulk--"the Order of the Kingdom."

Alp Arslan was a commanding figure, with mustaches so long that he had to tie them behind his long Persian cap to keep them from interfering with his archery. Moslem chroniclers hailed him as the bravest and wisest of the Seljuks, while Christian detractors called him a "drinker of blood" and a warrior of the Antichrist. He revealed his true character when Nizam al-Mulk asked the sultan why he did not have an informer to spy on factions within his court. "If I appoint an informer," the sultan replied, "those who are my sincere friends and enjoy my intimacy will not pay any attention to him nor bribe him, trusting in their fidelity, friendship and intimacy. On the other hand, my adversaries and enemies will make friends with him and give him money: it is clear that the informer will be constantly bringing me bad reports of my friends and good reports of my enemies. Good and bad words are like arrows; if several are shot, at least one hits the target; every day, my sympathy with my friends will diminish and that to my enemies increase. Within a short time, my enemies will be nearer to me than my friends and will finally take their place."

Alp Arslan had plenty of potential enemies and problems. His recently-won empire would only prosper if the Arabs and Persians who made up most of the population enjoyed peace and order. However, the Turkish army was full of steppe-born nomads who saw the cities of the Middle East as theirs to plunder, and gave their loyalty in return for booty. The original Seljuks showed some discipline, but the other Turks fought the Arabs and Persians for possession of wells and grazing lands and raided merchant caravans.

The solution Alp Arslan employed was the same one that Tughril-Beg had used: send the troublemakers to bother somebody else. The three most inviting targets were Asia Minor, Armenia (both ruled by Byzantium) and Fatimid-ruled Syria. As neither the Seljuks' appetite for war nor their rate of advance showed any signs of slackening, both the Byzantines and the Fatimids watched the Turks with growing concern. In 1064 Alp Arslan occupied the Armenian city of Ani, Byzantium's last conquest, and spent the rest of the decade capturing other border strongholds. Still, he did not plan at this stage to conquer Asia Minor permanently. Asia Minor was Christian territory, called Rum (Rome) by Moslems, and Alp Arslan had more respect for Christians than he did for the Shiite anticaliph in Egypt. Therefore, he negotiated a truce with Byzantium, and led his army against the Fatimids. In March of 1071, while he was besieging Edessa, a Byzantine diplomat visited the Turkish camp. Yet while the diplomat accompanied the sultan toward Egypt, talking peace along the way, there was an Imperial, if sluggish, response. The emperor, Romanus IV Diogenes, marched out of Constantinople with a large army, determined to take back the Armenian forts from the barbarians who had violated the majesty of New Rome.

What Romanus did not realize was that the Byzantine revival was over. The military machine that the last soldier-emperor, Basil II (976-1025), had built up, was starved of funds by a civilian administration that feared it; the bureaucrats reduced the number of regular troops until the empire's foreign mercenaries outnumbered them. Nevertheless, when news reached Romanus of the Seljuk advance on Egypt, it looked like a wonderful opportunity to end the recent series of reverses. His army, numbering between 60,000 and 100,000 troops, looked impressive on paper, but after years of neglect, it was both badly disciplined and poorly armed. The native troops of the Imperial Guard, who normally had permanent garrison duty in Constantinople, made up about half the force, and they were led by Andronicus Ducas, a bitter enemy of Romanus who was brought along because leaving him alone in the capital was too dangerous. The other troops--all mercenaries--were non-Seljuk Turks, Vikings, Armenians, Bulgars, Germans, and a group of Norman knights led by a famous mercenary captain, Roussel of Bailleul.

The units in this heterogeneous force had trouble getting along, and morale plummeted when they entered the Seljuk-devastated area; the emperor made himself a stranger to his own army by setting his camp at a distance from the troops. Alp Arslan learned they were coming in May, when he reached the Syrian town of Aleppo, and immediately turned around and headed north with only his personal guard of 4,000 men, recrossing the Euphrates with such haste that he had to abandon most of his horses and pack animals. When Romanus heard this news, he decided to continue his march; if time continued to favor him he would take the nearest forts before the sultan could raise reinforcements.

To do this, Romanus divided his forces. He sent the infantry and Roussel's Norman cavalry to capture Ahlat, on the shore of Lake Van. Then Romanus took the rest of the army to Manzikert, almost thirty miles to the north. Manzikert fell without a fight, and Romanus put a Byzantine garrison in the fort and returned to camp, confident that Alp Arslan must still be far away.

In fact, Turkish troops were less than a day's ride from Manzikert. Both Alp Arslan and his vizier, Nizam al-Mulk, were close to Lake Van, picking up additional troops wherever they could. The sultan probably reached Ahlat just before Roussel did. We don't know if the two forces fought, but the Normans and their infantry suddenly turned around and fled, hardly pausing until they reached Malatya, ninety miles to the west. They did not try to rejoin the emperor and did not even tell him they were gone. Romanus learned of the Turkish presence the next day when once of his foraging parties came under attack. Thinking it was only a single unit of Turkish archers, he sent a small force to drive it away. Word came back that the Turks were more numerous than expected, and more troops were dispatched. They fell into an ambush, and were slaughtered almost to a man. At last, Romanus knew that he was facing Alp Arslan's entire army.

Shortly after this, some diplomats (no doubt sent by Alp Arslan) came to the Byzantine camp; claiming that they were ambassadors of the caliph in Baghdad, they offered a truce. But the emperor thought he could still count on Roussel's Normans and his own infantry to get him out of a tight spot. Also, he did not want to return to a hostile court in Constantinople with only a treaty of questionable value to show for his efforts. Finally, the peace offer suggested that Alp Arslan doubted his own chances of winning. Romanus rejected the proposal.

The main battle took place on the arid plain just southeast of Manzikert, on August 19 or 26, 1071. The Byzantine army was deployed in the usual manner, along a straight front several ranks deep, with the emperor commanding the center; Andronicus Ducas brought up the rear. Since the lightly armed Turkish archers had superior mobility and range, the Byzantine strategy was to keep their forces massed, and try to engage the enemy in hand-to-hand combat immediately. The Seljuks also used their favorite formation, a crescent. Alp Arslan chose to watch from a hill on the edge of the plain, and gave command in the field to a eunuch named Tarang. The sultan was definitely pessimistic of his chances; he went into battle wearing a white robe that could double as his burial shroud if he did not come out of it alive.

At first, the battle went as planned for both sides. The Byzantines advanced en masse, apparently sweeping all before them; the Seljuk center fell back, while the flanks stood firm, shooting a rain of arrows into the enemy. Still, the open terrain favored the Turks, and the frustrated emperor pressed on until dusk without getting the decisive engagement he wanted. Now that he was miles from his undefended camp, with an army that was weary and hungry, he realized he was heading into a trap. He ordered that the Imperial standard be reversed, signaling a general retreat. The cavalry on the wings mistook the signal to mean that the emperor had fallen, and they broke ranks, spreading panic. From his vantage point, Alp Arslan saw this and ordered the men on the flanks to come together, closing the trap; he also sent in the reserves he had hidden in the ravines next to his hill. Romanus might have gotten away if the rear guard had come to the rescue, but the treacherous Andronicus fled all the way to Constantinople, letting everybody he met along the way know that the emperor had been defeated. Romanus was captured, and most of his army was cut down around him in the terrible moments that followed.

Alp Arslan was in a hurry to get back to fighting the Fatimids, so he released Romanus after the emperor agreed to some lenient peace terms: the return of the disputed forts to Turkish control, a large ransom, the repatriation of Moslem prisoners, the provision of Byzantine troops to fight Seljuk wars if Alp Arslan called for them, and a Byzantine princess to marry the sultan's eldest son. Yet Romanus never got a chance to fulfill the agreement. His stepson Michael Ducas proclaimed himself emperor in the aftermath of Manzikert, and had the ex-emperor arrested and blinded; Romanus died in pain and sickness a few days later.

Alp Arslan was furious when the news reached him, and he declared the treaty void. However, a rebellion on the other side of the empire required his immediate attention. He captured a rebel-held fort, and its commander was brought to him. The prisoner accused the sultan of cowardice, and Alp Arslan ordered him unbound so they could fight; the sultan's arrow missed, and the prisoner stabbed him with a concealed dagger before the guards hacked him to pieces. Four days later the victor of Manzikert died of his wounds in distant Central Asia.

A statue of Alp Arslan in Turkmenistan.

Asia Minor Becomes Turkey

Manzikert was an unmitigated disaster for Byzantium, though they realized it as such only gradually. The whole eastern half of the empire was left defenseless; into the resulting anarchy stepped individual tribes of Turks, loyal only to their own chieftains. Soon they overran all of Asia Minor's interior, and only the Bosporus saved Constantinople. The most powerful tribal chief was Sulayman, a son of the Kutulmush who had competed for the Seljuk throne with Alp Arslan in 1063. Understandably, he wanted nothing to do with the Seljuk ruling family, and in 1078 he proclaimed himself sultan of Rum, paying only lip service to the sultan of the greater Seljuk empire. During the many struggles for the Byzantine throne, Sulayman was often invited to help one or another rival faction, and while doing that he captured important cities like Nicaea (modern Iznik, 1081) and Nicomedia (Izmit, 1087); Nicaea subsequently became his capital.

The Turkish migration completely bypassed one group of Armenians living in the uninviting Taurus mountains. This community had gotten started in the tenth and early eleventh centuries when the Byzantines deported some troublesome Armenian princes, giving them estates in this region. When the Turkish raids began more Armenians moved to these safer lands. The original or Greater Armenia will be under foreign rule for most of the remaining chapters of this work, but Lesser Armenia, in southeastern Turkey, remained on maps of the Middle East until 1375.

The Seljuk Empire under Malik Shah and Nizam al-Mulk

In the Seljuk Empire, Alp Arslan was succeeded by his son, Malik Shah (1072-1092). Malik Shah's name, which combined the Arabic and Farsi words for "king," signified the Seljuk desire to unite all Moslem peoples under their rule. He preserved the Turkish custom of sending an arrow with his dispatches as a symbol of his authority, and practiced the favorite Turkish pastimes of polo, hunting, and falconry. Yet unlike his predecessors, he had been raised in the civilized world, and under him many Seljuk ways were replaced with Arabic, Persian, and Byzantine customs. What little we know about his character contrasts strongly with that of his great-uncle Tughril-Beg, who probably never slept under a fixed roof in his life, and who, when he first tried almond candy, remarked that it was delicious but they should have made it with garlic.

Since Malik Shah was only eighteen years old when he became sultan, Nizam al-Mulk managed the empire initially, and Malik Shah never completely escaped his vizier's influence. Nizam al-Mulk strengthened the throne against its unruly subjects by increasing the power of bureaucrats and palace officials. He wrote his political theories down in a book called the Siyasat-nama (Book of Government). In it, he stressed the need for kings to constantly remind the people of their authority in various ways; severity toward disloyal subjects must be balanced by justice/rewards for the loyal, and he repeated the suggestion Alp Arslan had rejected, namely that agents of the sultan should infiltrate the court. He also suggested that generals should be kept in place by holding their sons hostage from time to time, and that the army should include men from many nationalities to reduce the risk of alliances forming against their common master. The book's existence reminds us that the Seljuks were unable to provide a stable government; had they done so, this work would have been unnecessary.

Under the dual rule of Malik Shah and Nizam al-Mulk, the Seljuk empire reached its peak. The army they maintained was a very large one for that age, numbering 70,000 cavalry alone. The oft-delayed Seljuk-Fatimid war resumed, and carried to a successful conclusion; they conquered all of the Levant, including Jerusalem, by 1076. Afterwards the Hejaz, Oman, and Baluchistan also recognized Seljuk supremacy, though Seljuk troops were never sent to occupy any of those regions. In 1084 Sulayman, the sultan of Rum, advanced east to take Antioch, but two years later he was defeated and killed near Aleppo; Sulayman's son, Kilij Arslan, was captured. Malik Shah then attempted to form an alliance with Byzantium, the goal being a two-pronged invasion of Turkey, but nothing came of it. After Malik Shah's death in 1092, Kilij Arslan escaped and revived the Rum sultanate. During his captivity, however, northeastern Turkey declared independence under a rival chieftain, Danishmend of Sivas; his successors became a continual thorn in the side of the Rum Seljuks.

Finally, we should mention that Nizam al-Mulk was a great patron of education. Schools known as madrasas were built on an unprecedented scale, and they taught religion and science from a Sunni point of view. By making the best education available only to Sunni Moslems, and promoting only madrasa graduates to important positions in government, justice and religion, the Seljuks effectively checked the influence of radical Shiite propaganda, whether it came from Fatimid Egypt or from their own Shiite subjects. Umar Khayyam and al-Ghazali, whose accomplishments were described in the previous chapter, are two fine examples of the kind of student the madrasas produced.

The Order of Assassins

Nizam al-Mulk had good reason to fear the Shiites, particularly the Ismailis, as the empire's most dangerous enemy. Late in his reign a Persian named Hasan-i Sabbah (1050-1124) founded the Order of Assassins and dedicated them to advancing the Ismaili cause.

Born in Rai, Hasan had been an early Ismaili convert; at the age of 24 he was already a deputy dai or teacher under Attash, the chief dai of Iraq and western Iran. In 1078 he went to attend the principal school for Ismaili missionaries, the House of Wisdom in Cairo. Two years later he was accused of interfering in the schemes of the Mameluke general Badr al-Jamali, who was the power behind the Fatimid throne. Cast into prison, Hasan won a reprieve when the tower in which they held him collapsed for no apparent reason. Some thought Hasan had used magic, and Badr looked for another way to get rid of him. Unwilling to risk Ismaili wrath by having Hasan executed, Badr placed him on a European ship sailing out of Alexandria. An unseasonal storm blew the ship north instead of west until the captain managed to put ashore in northern Syria and disembark his unwilling passenger.

After that Hasan established a network of dais in Iran who wandered around teaching the Ismaili doctrine, making converts, and organizing subversive activities against the Seljuks and their Abbasid puppets. Since he lacked both an army and great wealth, Hasan could not fight a conventional war against his Sunni foes, but assassination had long been a political tool in the Islamic world, and Hasan had no shortage of fanatics willing to die for his cause. Consequently that became his favorite tactic, though he also frequently used trickery, bribery, and outright lies.

To use his followers to maximum effect, Hasan first had to establish a suitable base of operations. He chose a powerful fortress in northern Iran named Alamut, "the Eagle's Guidance." Perched on a six-hundred-foot-high spur of rock, with only a single gorge leading to it, this eyrie was impervious to ordinary sieges. But Hasan, as we have seen, was no ordinary man. In September 1090 Ismaili members of Alamut's garrison smuggled Hasan inside. During the next few weeks he won over the entire garrison to his cause. Early one morning Hasan showed himself to the startled commandant, handed him a check for 3,000 golden dinars (which was subsequently paid in full), and wished him a pleasant journey home.

Once Alamut was his, Hasan, now known as the Master, strengthened the existing fortifications and set up a special school to train his followers. The Master picked these followers, known as fildais, from among the hundreds of applicants who hiked to Alamut every year. The ideal recruit was no older than twelve years and possessed a strong body, mind, and character. Those chosen were taught total obedience to the Master; ordinary religious beliefs were for the masses, and only the Ismaili imam had true eternal knowledge. They also got rigorous physical exercise, followed by training in the use of various weapons, especially the dagger. Finally the fildai learned be a master of disguise so that he could approach a potential victim easily. For the same reason foreign languages were taught, with court etiquette, since the victims were likely to be in the sultan's court. Fildais were ranked according to seven levels of achievement, and took part in secret rites and oaths every time they progressed from one level to the next.

We often think that the term Assassin meant "hashish eaters," suggesting that Assassins were often high on the drug during their missions to make them impatient of this world and oblivious of the personal consequences of their acts. Marco Polo wrote that just before a fildai received his first assignment, they would drug and take him to a place designed to resemble Paradise. He would wake up in a garden filled with fruit trees, lush greenery, bubbling streams, and beautiful women, and experience pleasures of every description. Drugged again, the fildai would wake up in his own bed with a renewed dedication to the cause. Some historians have suggested that Assassin really means "followers of Hasan" and have remarked that a garden like the one described above would have been an expensive luxury in the harsh climate of Iran, and quite unnecessary, in view of the real religious fanaticism exhibited by the Assassins.

Shocked to hear of the fall of Alamut, Malik Shah gathered his army and marched against the rebels. Since a direct assault was obviously futile, Malik Shah tried to starve the Assassins out, by destroying the crops on the farms nearest the castle. The siege continued on and off for two years, without success. One night in the fall of 1092 Hasan and seventy handpicked men sneaked into the sultan's camp, and plied their daggers with speed and silence among the besiegers. When dawn came the survivors realized how much carnage had been done and hastily withdrew.

Earlier in the same year they carried out the first successful assassination, setting the pattern for all subsequent ones. Nizam al-Mulk was stabbed to death by a fildai disguised as a Sufi holy man presenting a petition. The Assassin was slain in turn when he tripped on the tent ropes while attempting to escape. In November Hasan settled another old debt by poisoning Malik Shah. After that the Assassins would strike without warning at Seljuk officials in positions of authority, and at teachers of other Moslem sects who preached against the Ismaili creed.

With the sudden deaths of both the sultan and the grand vizier, the Seljuk empire went to pieces. Malik Shah left behind too many sons, resulting in a civil war between their backers. The heir, Nasir-ud-Din Mahmud, could only maintain order in Central Asia and Iran; this diminished realm was now renamed the Sultanate of Merv. The lands farther west fell into the hands of many emirs, not all of them Turks. These emirs, known as atabegs (guardians), were the acting governors of various provinces for infant Seljuk princes, but their inability to keep their charges alive soon outpaced the fertility of the Seljuk family. As a result, the Middle East was soon deplorably congested with petty states, and that paved the way for the Crusaders' initial success when they entered the region.

"Deus Vult!"

To the occasional European watching the Middle East in the late eleventh century, all the news was bad. The Turks had restored the vitality of a heretical religion that was supposedly on the decline, and now the "Saracens" looked more dangerous than ever. Byzantium, already hard pressed by Turkic barbarians from the north (Petchenegs & Kipchaks), was now in danger of destruction at the hands of Turks from the east; Kilij Arslan, the Seljuk sultan of Rum, ruled from Nicaea, only sixty miles east of Constantinople. The transformation of Byzantine Asia Minor into Moslem Turkey meant that it was no longer safe to make pilgrimages to the Holy Land, except by sea. Even those who made it to Jerusalem were likely to be turned back at the gates, as the Turks' conversion to Islam was too recent for them to allow the toleration Christians had enjoyed under the Arabs.

The pressure of all these dangers compelled the Byzantine emperor, Michael VII, to appeal to the pope for assistance. However, Pope Gregory VII was too caught up in events at home to send anything. Fortunately the Byzantines managed to survive, because the second emperor after Michael, Alexius I Comnenus, was the shrewdest politician of his day. By playing off Seljuks against Danishmendids, he kept his enemies from uniting against him, and a mixture of bluffs, bribes, treachery, and skillfully directed force allowed him to strengthen his position on the coast of Turkey. In 1095, he wrote a letter to the next pope, Urban II, again requesting aid to drive back the Saracens.(1)

Pope Urban II acted at once to answer the Byzantine call for help--for his own reasons. He did not care too much about Byzantium's plight, but he had heard stories about the suffering of Christians in the Holy Land, and was concerned about the dangers pilgrims now faced. With Byzantium dependent on Western arms, there might also be an opportunity to reunite the Greek and Latin halves of Christendom, which had been formally divided since 1054. Finally, the pope knew all too well that knights can be dangerous when they have too much time on their hands. Medieval Europe was the kind of place where "private wars" were a dime-a-dozen, where one duke might send his knights into a village belonging to another duke he had a quarrel with, and those knights would kill, rape and rob everyone in sight. Since the tenth century, the Church had tried to curb the violence by putting rules on it (e.g., no fighting on Sundays), and telling the knights where they would go if they didn't change their ways (for good measure, they would wave the relics of dead saints at the knights when they did this), but they only succeeded part of the time. Now the pope figured that if most of the knights went away to fight the enemies of Christianity rather than each other, there would be peace at home.

The pope left Italy for his native France, and summoned a council of bishops, abbots and knights at Clermont. There, on November 27, 1095, he addressed them. We don't know exactly what he said--accounts disagree considerably on that--but judging from the results it must have been one of the greatest speeches of all time. He talked of the sufferings of the faithful in the East, and called upon the knights to end their vile private wars so that they could turn their swords on the infidels instead. Those Christians who fought to redeem the Holy Land would have all their sins forgiven if they returned alive, and would have a place in Heaven if they didn't. The assembly answered Urban with a great shout of "Deus vult!"--God wills it. With that Christendom had found an answer to the jihads of Islam.

Next on the agenda came preparations. The assembly at Clermont chose Adhemar, the bishop of neighboring Le Puy, to lead the expedition. Urban said the prayers and absolutions necessary for a military venture, and commanded that the knights sew crosses on their garments, to mark themselves as warriors of the Cross; from that came the word crusade many years later. Priests went out to summon recruits for the pope's holy war. The list of nobles who answered the call reads like a Who's Who of the late eleventh century: Bohemond the Norman, son of the Duke of Apulia (southern Italy); his nephew Tancred; Godfrey of Bouillon, the Duke of Lotharingia (Belgium); his brother Baldwin; Raymond de St. Gilles, the Count of Toulouse (southern France); Robert, Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror's son; Stephen of Blois (William's son-in-law); Hugh of Vermandois, brother of France's king Louis VI; and Robert of Flanders. Around each of these figures professional armies gathered. Reasons of piety motivated many; others had no land and sought to carve out an inheritance of their own, or looked for glory and adventure. No kings went, though, because of recent religious strife in Europe; the three strongest kings (England's William II, France's Philip I, and Germany's Henry IV) had all been excommunicated by the pope, and it would be unseemly for an enemy of the Church to lead this enterprise. Whatever their reason for participating, it was the first time that the Christian kingdoms of Europe had ever cooperated on anything.

Before the soldiers were ready, however, another kind of Crusade began. This was led by a poor knight who was appropriately named Walter the Penniless, and a popular preacher known as Peter the Hermit. Peter carried what he called a Heavenly Letter, claiming that an angel had given it to him with a command to preach the Crusade to Christ's poor, so that they could redeem the earth. Thousands of peasants listened to Peter's stirring speeches and set off for the Holy Land. They shod their oxen and crammed their families into carts, or simply slung their possessions over their shoulders and walked. The crowd had a few knights in it, but most of those participating in "The People's Crusade" had neither horses nor armor. They went forth expecting miracles to help them; stories were told about Charlemagne rising from the dead to lead the Crusade.

The first of these large and disorderly bands departed from Cologne in April 1096. Once they got going, they found a target: the Jews who lived in the cities of Germany. The newcomers had trouble distinguishing between Jews and Moslems, and tried, although the Church disapproved, to force conversions. At first the Jews used prayers and bribes to the local authorities to secure protection. Then in May, the mad count Emich of Leiningen arrived, leading a rabble too big to resist. The count massacred those Jews he met who refused baptism. This was just the first of many anti-Semitic incidents that would occur on every crusade; as a result the Jews gave their support and sympathy to the Moslems.

More trouble came when the mob left the Rhine and entered the Danube valley. The Hungarians speak a language completely unrelated to those of western Europe, and consequently the pilgrims seem to have thought they were already in the lands of the infidel. At every new city the children among them cried out, "Is this Jerusalem?" Discipline broke down altogether, and because the pilgrims did not bring much food or money, they pillaged the countryside until the local forces attacked and dispersed them. In August 30,000 pilgrims reached Constantinople, where an astonished and dismayed emperor Alexius greeted them. He gave them food and shelter--well outside the city walls--and ferried them across the Bosporus to Turkey as soon as possible. Then he prudently told them to wait until the main army of the pope arrived, because it was better equipped. Instead, they attacked Nicaea and surrounding towns; in October the Turks ambushed and massacred them. Walter the Penniless was killed in battle; some survivors saved themselves by converting to Islam; the rest were sold into slavery or used for archery practice. On the other hand, Peter the Hermit returned to Constantinople to seek the emperor's help when he saw disaster coming, so he escaped.

The First Crusade

Meanwhile, the real, armed Crusade was making its way across Europe. The first group reached Constantinople in December 1096; the last stragglers arrived in April 1097. Wearing helmets and clothed head to foot in chain mail, they were better protected than their Moslem opponents. Instead of using bows from a distance, which was the preferred Turkish tactic, the European cavalry combined man, horse, and lance to create an unstoppable projectile. A knight on horseback, they said, could charge through the walls of Babylon. As for the infantry, which made up seven eighths of the Crusader army, it fought with spears, axes, and especially crossbows, which sent bolts clean through any shield or armor the Moslems had. Moslems later reluctantly praised the cooperation between Western cavalry and infantry, each defending the other effectively against the light horsemen that made up the bulk of the Turkish forces.

The Byzantine emperor Alexius had mixed feelings about the Crusaders. No doubt he was glad to see that his appeal got an answer, but all he expected to receive was some additional mercenaries for his own army. Instead it now looked like the entire barbarian West was converging on New Rome, and the Crusaders' blend of ignorance and fanaticism made them dangerous allies. Alexius used their staggered arrival to his advantage: he kept them divided and dependent on the Empire for supplies, and made each group of Crusaders swear loyalty to Alexius and promise to return to Byzantium any territory they conquered that lay within the pre-Manzikert Imperial frontier. Then he excused himself from the conflict he was sending the Crusaders to fight in. The Crusaders found this behavior most unchivalrous, since it meant they were under the authority of a man who refused to lead them. They did not think too kindly of their supposed ally after this.

In May the Crusaders crossed the Bosporus with their Byzantine associates and marched to Nicaea, over the bones of Peter the Hermit's followers. Kilij Arslan was not there; he thought the threat from the West had ended with the slaughter of the People's Crusade and was now fighting Moslem rivals, the Danishmendids, on his eastern border. When the Crusaders arrived at Nicaea, Kilij Arslan was besieging Malatya, an eastern city. He was so confident that he could beat the Crusaders that he did not bother to remove his family or his treasury from Nicaea; that would be a critical mistake. By the time he realized the danger, at least 40,000 Crusaders were camped outside the walls of his capital, and more were on the way. Kilij Arslan rushed back with his army, covering more than 400 miles in just one week, but the Crusader army was too strong for him to take it on with just the light cavalry he had. To have a chance of winning he would need the help of others, so he called on the Turks he had just been fighting to join him, in a holy war against an enemy that was a threat to them all. The Danishmendids marched to the rescue, but they would need time to get to get to Nicaea, and now the Crusaders were besieging the city.

If the Crusaders took Nicaea, they would surely loot it. Nicaea had been a Byzantine city just a few years earlier, and Alexius wanted to retake it intact, so he pulled a fast one; his diplomat went into the city and persuaded it to surrender to the Byzantines, not to the knights outside. The terms the diplomat offered were exceptionally generous; if the Nicene Turks surrendered, not only would they be spared, but a cash reward would be given to their leaders, and most of the city's administrators would even get to keep their jobs. Some of those administrators had worked for the Byzantines in the past, and they certainly would be willing to work for a Christian boss again. The next day the Crusaders woke up to see the Byzantine banner flying over the city they had hoped to plunder. They grumbled about losing an opportunity, but finally moved on. They marched southeast across the Anatolian plateau in two divisions, one a day ahead of the other. Bohemond led the first, while Raymond of Toulouse led the second; the rearguard included the forces of Godfrey of Bouillon and Bishop Adhemar. Back in Nicaea, the Byzantines hauled the sultan's treasury, and family, to Constantinople; the wives and kids would become the emperor's hostages now.

Kilij Arslan returned, and on the first day of July he ambushed Bohemond's advance guard just after they passed through the pass of Dorylaeum, almost 100 miles from Nicaea. The Turks surrounded the Christians and started shooting arrows into the Christian camp from an astonishing range. By the rules of Turkish warfare, the battle was as good as won, but the Crusaders stood fast until the second and main part of their army arrived. Too late, Kilij Arslan realized that he was now the trapped one. Godfrey's vanguard fell on the Turks like the wrath of God, while Adhemar's troops came around the hills to attack the Turks from the rear. The Crusaders killed as many of the fleeing Turks as they could, and gave the Turkish camp an overdue pillaging.

Once done, the Crusaders continued their march to Syria. The Byzantine force accompanying the Crusaders dwindled to a mere token, as Alexius detached units to garrison the newly liberated territories. The Seljuks had been broken, but in the summer Turkey is a formidable obstacle by itself: waterless plains, salt lakes, terrible mountains and terrible heat. Here the Crusaders suffered greatly, leaving their dead and much of their armor beside the roads. Finally they crossed the Taurus and Anti-Taurus mts., and entered Lesser Armenia. The Armenians, being Christians themselves, welcomed the Crusaders and guided them through their rugged land to Antioch, the greatest city of the Levant.

While most of the Crusader army set up camp outside Antioch, Godfrey's brother Baldwin went on a useful side excursion. Taking a hundred horsemen with him eastward, he visited the Armenian communities of northern Syria. The Armenians flocked to his banner, they captured two Turkish forts on the upper Euphrates, and one Armenian prince, Thoros of Edessa, adopted Baldwin as his son. Within a month, Thoros died in a riot and the crown of Edessa went to Baldwin. The first Crusader state was thus established, occupying a strategic spot between Antioch and Mosul.

Antioch should have resisted any assault made on it. Its massive walls, topped with 400 towers, were a masterpiece of Roman engineering. The city was too big for an army to surround, the Orontes river brought an unfailing supply of water, and there was a strong Moslem garrison inside. The Crusaders, by contrast, lacked siege equipment, and had lost most of their horses in Turkey; four out of five knights were either using donkeys or walking and fighting on foot. They sat outside the walls of Antioch for half a year, and the winter rains made Syria almost as wet, cold, and muddy as northern Europe. Food ran out, Turks ambushed foraging parties, morale dropped and desertions became a problem.

In the end the Crusaders prevailed because of the division between their opponents. Different atabegs controlled the main Moslem cities in the area--Aleppo, Damascus, and Mosul--and they found it nearly impossible to cooperate for any length of time. The governor of Antioch had often switched his loyalty between Aleppo and Damascus in the past; he appealed to both for assistance, but neither wished to associate with the other. The result was that the Damascenes attacked in December 1097, and the Aleppans came in February; furious charges of the knights drove both away. Then in May came Kerbogha, the terrible ruler of Mosul. When the Crusaders learned that he was marching with a great army of Iraqis and Persians, many of them fled back to Byzantine territory. They met Alexius halfway between Antioch and Constantinople, and told a tale so depressing that the emperor decided the Crusade was a lost cause and retreated with them. Those Crusaders who stayed at Antioch saw this as a betrayal, and never gave any more territory to Byzantium after that. Alexius, however, never gave up his claim to Antioch, and that would lead to sour Byzantine-Crusader relations during the twelfth century.

Because he did not want a potential enemy in his rear, Kerbogha attacked Edessa first. For three weeks he besieged Baldwin's city before he gave up and resumed his advance on Antioch. That amount of time made all the difference for the Crusaders. Bohemond the Norman had somehow contacted an Armenian renegade within Antioch, the commander of three of the 400 towers. Keeping to a plan they agreed on, Bohemond marched the army away from the city, as if to meet Kerbogha. Then on the night of June 2, the Crusaders sneaked back, and the Armenian let them into the city. One day later, every Moslem in the city was dead.

On June 7, Kerbogha arrived, and now it was the Christians' turn to be under siege. They endured misery, hunger, and fear for three weeks, until an apparent miracle saved the day. A French pilgrim, Peter Bartholomew, declared that St. Andrew had appeared to him in a vision and told him that a most sacred relic, the spear which had pierced Jesus on the cross, lay buried under a cathedral. The Crusaders dug for a day, and sure enough, a rusty spearhead appeared. Bishop Adhemar and some skeptics (including more than a few modern historians) suspected that Peter Bartholomew had hidden the "Holy Lance" in the diggings while nobody was looking, but most of the Crusaders believed and rejoiced.(2)

Then St. Andrew spoke to Peter again, promising a victory if they attacked the Moslems. On June 28, the Crusaders held a mass, confessed their sins, and sallied forth under Bohemond's command, with the Holy Lance mounted on a pole in front of the army as a standard. Kerbogha's army had gained reinforcements, but the newcomers were from Damascus, Aleppo, and the nomad tribes of the Syrian desert, and now they were having second thoughts, wondering if a victory would benefit anybody besides the fierce lord of Mosul. The Christians had no such doubts, and the resulting victory for them was more complete than Dorylaeum had been. Antioch would be theirs for years to come; the surviving Moslems could only think of their own safety, and fled to their cities.

Hearing of the Seljuk misfortune in Syria, their archenemies, the Fatimids, now got involved, marching from Egypt to Jerusalem. After six weeks of siege, the Seljuk garrison in Jerusalem decided it had enough; the Turks accepted a sizeable sum of Egyptian silver and marched away. The Holy City was now in Shiite hands again.

Meanwhile in Antioch, a typhoid epidemic killed many, including Bishop Adhemar. Without his guidance, the lords of the Crusade did not know what to do next, and they spent the rest of 1098 in indecision. Finally the ordinary soldiers got bored and threatened to pull down every stone in Antioch if the army did not resume the march to Jerusalem. In January 1099, the army got moving again, marching down the coast of Syria and Lebanon. Here the local Arabs were happy to be free of the Turks, and offered guides and food. When they reached Jaffa, the Crusaders turned inland, and on June 7 they saw Jerusalem, knelt, and wept. They had been on their armed pilgrimage for three years now, and only one out of five had made it to the ultimate goal.

The Crusaders had to fight one more battle before they could consider their work finished. They tried a direct assault on Jerusalem, and it failed bloodily because the Crusaders lacked catapults and scaling ladders. Nor could treachery work the way it did in Antioch; the Fatimids had expected trouble from their Christian subjects and expelled them all from the city previously. The Crusaders were left baffled and thirsty, since the Fatimids had with equal foresight poisoned every well for miles.

This time they were saved by the merchants of Italy, who no doubt saw new business opportunities if they could get involved on the right side. Galleys from Genoa sailed into Jaffa and brought just what the Crusaders needed--fresh provisions and the materials to build catapults and siege towers.

Shortly after that Bishop Adhemar's spirit appeared in a Crusader's dream, promising a victory in nine days if they fasted and made a barefoot procession around the city. The Crusaders obeyed, and walked across the rocky slopes leading to Jerusalem, praying, singing, and holding crosses and relics. They were careful to stay out of bowshot of the Moslems, who watched and shouted profanities. On July 14, 1099, the siege towers were ready, and a new furious assault on the city began. This time the defenders--both Jews and Moslems--could not withstand them, and when the Crusaders broke into the city, they slaughtered everyone they met.

The first thing the triumphant Crusaders did afterwards was to march to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, where they wept with joy and gave thanks to God. The second was to decide what to do with their new conquest. At first they offered it to Raymond of Toulouse, but he piously refused, declaring that he would not be the king of Christ's kingdom. Then the crown was offered to Godfrey of Bouillon, who first declined, then changed his mind and accepted. Remembering what Raymond did, he called himself prince of Jerusalem rather than king. Raymond found even this honorific disgusting, though.

The Crusaders stayed together long enough to beat off a Fatimid counterattack before going their separate ways. Before the Crusade, Raymond had taken an oath never to return from the East, but he thought a visit to Constantinople was permissible. That left Godfrey with only 300 knights and 300 infantry to defend Jerusalem. In the following year (1100), Godfrey fell ill and died, and Bohemond, now the king of Antioch, was captured while making a raid on the Danishmendids. The new pope, Paschal, tried to rescue the situation by sending some 50,000 armed pilgrims east. They got as far as Constantinople, where Raymond joined them, only to meet with disaster once they crossed over into Turkey. Kilij Arslan had learned his lesson from the previous encounter, and chose to fight a war of attrition. Instead of engaging the Christians head on, he let the blazing heat do the dirty work, harassed them with arrows from a distance, and waited until thirst and exhaustion broke them into small bands that could be easily slaughtered. Raymond fought his way back to Constantinople, and sailed off to new adventures in the Holy Land. A few Crusaders made it through the opposition and reached Syria, but no real help got to Jerusalem by land.

Consolidation

The secret to Crusader success was Moslem disunity. To many Sunni and Shiite Moslems, the Christians were not the most obnoxious enemies. Any Moslem leader strong enough to throw the Christians back into the sea would be an even greater threat to his Moslem neighbors.

When Bohemond was captured, Baldwin of Edessa became the most important Crusader leader. He put Bohemond's nephew Tancred in charge of Antioch, gave Edessa to his own grandnephew (also named Baldwin), and went south to take command of his brother's kingdom in Jerusalem. He had none of Godfrey's modesty about declaring himself king, and ruled with skill and courage for eighteen years.

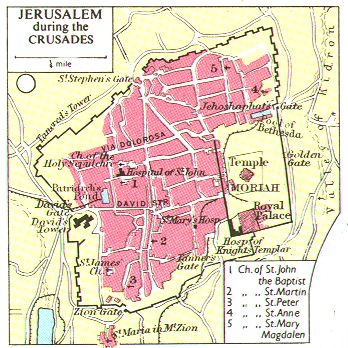

For the rest of his life Baldwin waged war against Islam, and was generally successful. One by one he captured the cities of the Holy Land that were still in Moslem hands. He gained a Red Sea port when he took Aylah--modern Eilat, and gained a more secure frontier by advancing east to the Jordan River. To the southwest, he took the nearest Fatimid fortress, Ascalon, but the Sinai peninsula remained a land of Bedouins who robbed Egyptians and Europeans impartially. He could never take Tyre; the coastal city which had withstood incredibly long sieges from Assyria, Babylon, and Alexander the Great held out until 1124. Baldwin also pushed north as far as Beirut, giving himself a kingdom about equal in size and borders to modern Israel and southern Lebanon. Everything between Beirut and Antioch went to Raymond of Toulouse, and became known as the county of Tripoli. The four Crusader states of Jerusalem, Tripoli, Antioch and Edessa together made up a fragile ribbon between the Red Sea and the Euphrates that was 600 miles long, and between 10 and 100 miles wide. Europeans came to call these kingdoms Outremer, meaning Beyond-the-Sea.

Meanwhile, Bohemond managed to buy his freedom from the Turks, and decided that his real enemy was not Islam, but the treacherous Alexius. According to an absurd tale by Anna, the daughter of Alexius, Bohemond got through Byzantine-controlled waters by spreading a rumor that he was dead; to complete the ruse, he had himself shut up in a coffin, along with a dead rooster that provided the appropriate odor! Once he reached Italy, he got off the boat and recruited volunteers for a new Crusade, this time against Byzantium. They were defeated at Durazzo in Albania in 1108, and Bohemond spent his last years in Italy disappointed.

Back in Syria Tancred flung himself enthusiastically into local politics. The Normans and the Turks soon learned that they had much in common, in courage and chivalry, and grew to respect each other. This resulted in some complicated alliances. For example, in 1108 Jawali of Mosul and Baldwin II of Edessa attacked Ridwan of Aleppo, who was in turn rescued by Tancred.

Life In Outremer

It took a steady stream of Christian immigrants from Europe to maintain the Crusader states against more numerous, if disunited, foes. Most of them came by sea, on the ships of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa. Eventually the number of Westerners settling in Outremer reached a maximum of 140,000; 2,000 of these were nobles and knights, while the rest were foot soldiers, unarmed pilgrims, and settlers (both women and men). The largest number came from France, but every Catholic country sent a contingent. Moslems, however, gave all Europeans the "Saracen" treatment, and called them al-Faranj--the Franks.

The Franks zealously built churches and sturdy castles wherever they went. They rid all holy places, including Jerusalem, of Moslems; elsewhere the native Moslems, Jews and Orthodox Christians were left undisturbed. In the coastal cities, Italians became the dominant nationality, since they controlled the ships and trade with the West.

Throughout Outremer, only the testimony of a Catholic carried full weight. This effectively kept non-Catholics from rising in the hierarchy, since feudal nobles were expected to sit in court and offer their views on cases. Nevertheless, they tried to be evenhanded. While the main civil courts were entirely in Western hands, native courts were allowed to try small cases. Villages could govern themselves as they pleased, if they paid taxes to their new lords. Some Moslems admitted that they prospered more under the rule of the Franks than they did in any Moslem country.

The years passed and took away the heroes of the First Crusade. The second generation of Crusaders had lived all their lives in Outremer, and had learned to get along with their Moslem neighbors. From the Moslems they had acquired a taste for olives, grapes, white bread (dark rye bread was the most common food in northern Europe at this time), perfumes, turbans and fine loose clothing, and dancing girls. Their life may have been pleasant, but a lot was going on in the Islamic world that they never perceived. Moslem literature, science, mathematics, and philosophy were still developing with nearly as much vigor as they had in Abbasid days, but the semi-literate Europeans completely missed the real culture of the East. Admittedly the Moslems they usually dealt with were Turks, who were less civilized than the Arabs and more interested in sports and war than they were in learning.

Both Christian and Moslem benefitted from the trade that resulted when their cultures were placed so close together. The mineral resources of the Middle East had been mined out over the centuries, to the point that only Armenia and southern Iran had any metal deposits that were still worth working.(3) To make up for this lack the Islamic world now imported the metals it needed from Europe and Central Asia. The sultans also imported from the west manufactured goods, wool, timber and timber products--pitch, tar, turpentine and potash.(4) In return the East exported fruits and high-quality textiles such as silks, brocades, tapestries and carpets. Before long, however, they found that a Far Eastern import, spices, were the easiest way to pay for what they bought from the West. When Europeans developed a taste for spices the Moslems began buying up as much as they could, keeping a little for their own use and passing on the rest at a steeply marked-up price. At first the spices came by a traditional trade route: on ships from Southeast Asia to the Persian Gulf, then across Iraq and Syria to Aleppo before it crossed the border into Outremer. After 1100, though, the political turmoil of the Middle East persuaded the spice traders to take their cargo to Egypt instead. The relative strength of Egypt at the end of this chapter and in the period covered by the next may owe nearly as much to the wealth it gained from this commerce as it does to the outstanding leadership of Saladin and the Mameluke sultans.

Moslems thought the Westerners were shameless, because their women went unveiled and could talk to any man they met on the street, but they never questioned their courage. Indeed, it was their military prowess that allowed the Crusaders to survive as long as they did. Only at sea were they safe. The only Moslem fleet left in the eastern Mediterranean, that of the Fatimids, was destroyed by Venetian galleys off Ascalon in 1123; the Turks held that only lunatics trusted themselves to the waves. On land, however, there was never absolute safety. Most of Outremer's frontier was desert, and its length made it a nightmare to defend. Minor campaigns went on almost constantly. The Christian manpower came mostly from the armed immigrants mentioned previously. Armenians and the Maronites of the Lebanese mountains also made a contribution, but most native Christians did not want to fight. Urban II had been misinformed about the sufferings of Christians in the Middle East; most of them found the pope almost as alien as the caliph.(5)

Eventually two elite military orders were set up to defend the Crusader states. These were the Knights Templars and the Knights Hospitallers of Saint John, and both combined the piety and discipline of monks with the bravery of soldiers. The Templars got started when nine knights showed up in 1118, offering to protect and escort pilgrims traveling between the coast and Jerusalem; their headquarters was in a house next to what they believed was the site of Solomon's Temple. It was a small step from protecting pilgrims to protecting the kingdom; they became a full fledged fighting order in the 1130s, after the Church approved of what they were doing. The Hospitallers, as their name suggests, were originally doctors, caring for poor pilgrims when they were sick. Yet they found the militant ideology of the Templars irresistible, and adopted it as their own around 1150.(6) Knights looking for salvation came from Europe to join both orders; pious lords bequeathed riches and land to them, and helped them build castles in Outremer. They lived simply, and gave their obedience to nobody but their masters and the pope. A report from 1180 stated that there were 300 Templars and 600 Hospitallers in the Holy Land, which was probably the maximum size of their force; for both orders, their reputation as the toughest warriors in Christendom was more important than their actual numbers.(7)

The Moslems had no military order to match the knights, but one Moslem group was even more dedicated to its cause: the Assassins. They announced their presence in 1103, by stabbing the Moslem ruler of Homs on the eve of an important battle with Raymond of Toulouse. Since both Crusaders and Assassins saw Sunni Moslems as their main enemy, they became unexpected allies. The Assassins set up a stronghold in northern Syria, and their leader, who was nicknamed the Old Man of the Mountain, had extensive dealings with the Christians. In 1106 a coup delivered the city of Apamea into Assassin hands, and they gave it as a gift to Tancred. Because of the Assassins' reputation, most Christian rulers protected themselves by paying tribute. Only the Templars and Hospitallers refused; they would not give in to blackmail under any circumstances. But the elite knights did not have to pay anyway; when they inherited two tracts of land next to the Assassins' stronghold, the Assassins became concerned enough about their own safety to pay tribute to them!

The Seljuk-Assassin War

Islam's initial reaction to the First Crusade was confusion. Some Sunnis thought the "Franks" were Fatimid agents, sent from Egypt to destroy true Islam. A few years later, the kingdom of Georgia swept out of obscurity to take Tbilisi in the Caucasus (1121), and with that the Christian counterattack reached threatening proportions. It took a whole generation for Islam to revive and combine its efforts to bring Christendom's advance to a halt. Meanwhile the political kaleidoscope continued, now more chaotic than ever.

Another Christian state that benefitted from Islam's situation was Byzantium. Alexius and the emperors that followed him conducted several minor Imperial campaigns in Turkey that recovered the entire coastline. Most of the interior, however, remained under Moslem rule. Since the Byzantines made their gains at the expense of the Sultanate of Rum, the Danishmendids were comparatively strengthened. After it lost Nicaea to the First Crusade, the weakened Seljuk authority moved its capital to the ancient and less accessible city of Iconium (modern Konya).

The nastiest conflict in the Islamic world remained that between the Assassins and the Seljuk Sultanate of Merv. The Seljuks killed anyone they suspected of being an Assassin or an Assassin sympathizer. The reprisals did not affect Assassin activities, though, and their opponents continued to live in a constant state of fear. No one knew where they would strike next or who would be the target. Many of their less dangerous opponents woke up to find a dagger implanted in the pillow next to their heads, its message abundantly clear and seldom ignored.

In 1105 the sultan Ghiyath-ud-Din Mohammed Topor tried to end the Assassin threat by destroying Alamut. After heavy fighting the Assassins and their allies, four Jewish congregations that lived in the surrounding mountains, defeated him. In September of the next year Hasan-i Sabbah struck back. The vizier, Nishapur Fakhr al-Mulk (son and successor of Nizam al-Mulk), was slain by a beggar presenting a petition. The vizier's guards captured the "beggar," and under torture he revealed the names of twelve co-conspirators in his crime, all of whom were important court officials. After the officials were executed, it was discovered that they were all innocent. The Assassin died knowing that he had killed thirteen enemies of the Order of Assassins with a single dagger thrust.

In 1108 Hasan banished his wife and daughter from Alamut, never to see them again, and declared that from now on he would allow no women in the fortress. With his wife gone Hasan could choose a successor in his own way. He did not think his sons were suitable heirs and was positive they would cause trouble if somebody else was picked to succeed him. The problem was solved when a dai was mysteriously murdered in the fortress; Hasan's eldest son was charged, judged guilty though the evidence was slight, and sentenced to death. Another son was executed for simple disobedience. The third and youngest son somehow found some forbidden wine in the fortress and paid for his drunkenness with his life.

With his dynastic troubles behind him Hasan could turn his attention back to the Seljuks. Topor returned to Alamut in 1110 and tried to starve the Assassins into submission. He nearly succeeded; the fortress was on the verge of capitulation when Topor died in 1118, without the aid of the Assassins. The Seljuk realm split right down the middle; a son of Malik Shah, Mu'izz ud-Din Sanjar, seized power in Central Asia, leaving only Iran to Topor's son. Now there were three Seljuk sultanates, centered on Iconium, Hamadan, and Merv.

The Seljuk squabble gave the Assassins a reprieve, but before the year was over Sanjar marched on Alamut with another army and renewed the siege. One morning he found a dagger in his pillow, with a note impaled on its blade. The note contained a single word from Hasan: "Negotiate!" Sanjar found it convenient to agree.

Not long after that the sultan's ambassadors made the long walk up the mountain to the gates of Alamut. Inside they found row after row of youths wearing red tunics and white trousers, surrounding an old man who stood erect despite his sixty-eight years. Gathering their courage, they stepped up to Hasan and announced Sanjar's generous terms: acknowledge the sultan as rightful ruler, abandon Alamut, and be thankful your life will be spared. Hasan responded by nodding slightly to a young fildai who immediately drew a knife and slit his own throat. Then Hasan turned and nodded to another fildai on the fortress wall; this one leapt into space to meet his end on the rocks more than six hundred feet below. Hasan told the shocked ambassadors that he had 60,000 followers who would obey him with as much enthusiasm as the two that had just died.

Hasan gave his own terms for peace and sent the ambassadors back to Sanjar's camp. In exchange for tribute and immediate withdrawal the Assassins would stop proselytizing in the sultan's domains and put their unparalleled intelligence service at his disposal. Sanjar agreed to those terms and hurried to the relative safety of his capital.

In 1121 the long arm and unfailing memory of Hasan reached out to slay Afdal, the Egyptian vizier who had ousted Nizar, his favorite Fatimid, twenty-six years earlier. This was the last major assassination of Hasan's lifetime. He died in 1124, after naming Buzurg Umid, one of the original Alamut garrison, to be his successor. Umid, however, broke with the will of Hasan and made his own son heir, starting a dynasty that lasted until 1256. Umid and each of the next six grand masters continued to enjoy success, but never again was the Order of Assassins led by such a capable visionary.

The Second Crusade

To destroy Outremer, the Moslems would have to unify their portion of Syria first. It was Imad-ud-Din Zangi (1127-46), the atabeg of Mosul, who did that and began the counterattack against the Christians. A religious moderate, he became Islam's champion through almost accidental circumstances. For most of his reign Damascus was the main enemy; it was only when his attempts to undermine that city failed that he turned his attentions elsewhere. In 1144 he attacked a Moslem ally of Edessa, and when the count and army of Edessa marched to the rescue, he turned to attack Edessa itself. He quickly conquered the undefended city and destroyed the most vulnerable of the Crusader states.

The loss of a whole kingdom called for a mighty counterblow. In 1146 the call went forth for a new Crusade. Two kings, Louis VII of France and Conrad III of the Holy Roman Empire (Germany), took the Crusader's oath, as did Bernard, abbot of Clairvaux and the most influential clergyman of the day.

Christendom expected much from the Second Crusade, and it was a disappointment. To begin with, many Crusaders never even left Europe. One group of Germans crossed the Elbe River and attacked the Wends, a pagan Slavic tribe living in eastern Germany. The English and Dutch Crusaders sailed as far as Portugal, disembarked there, and helped the Portuguese take Lisbon from the Moors. The pope declared both diversions legitimate Crusades afterwards, because in both cases the opponent was an enemy of Christianity. Another setback was the assumption of Crusading leadership by the kings of Europe; because they could not stay permanently in the East, they were a poor substitute for the land-hungry, nothing-to-lose lords who led the First Crusade.

The German contingent tried to cross Central Turkey in the autumn of 1147, and fell at Dorylaeum to the same kind of ambush that stopped the People's Crusade and the expedition of 1101. A few survivors managed to retreat to Nicaea. Three months later the French arrived, picked up the Germans, and marched along the Byzantine side of the frontier. The Turks attacked them as well, but the kings and many knights made it to the southern port of Antalya, where they boarded ships for Antioch.

Zangi perished before the Crusade arrived. He awoke after an evening's drinking to find his servants finishing the wine; he uttered dreadful threats, went back to sleep, and for their own safety the servants made sure he did not wake up again. His son Nureddin had no trouble riding out the attack when the pitiful remnant of Crusaders finally reached him. The Crusaders withdrew to Acre in 1148, and decided that Damascus was a richer prize to have. To the knights who grew up in Outremer, this must have seemed foolish; the Moslem ruler of Damascus had always been friendly to Christians.

The knights of the Second Crusade, joined by Jerusalem's Baldwin III, invested Damascus and began the siege. Overnight the Damascenes decided that they preferred the son of Zangi to a Frankish prince, and called for help. Nureddin had been preparing to attack Antioch, but he promptly marched to the rescue. His help wasn't needed; the Crusaders unwisely shifted their attack to a spot where the walls were weaker but water was lacking. The walls held up, and after four days the water supply ran out. The three Frankish kings quarreled at this point, took their armies home, and ended the Second Crusade. Nureddin turned around when he heard the news, but in 1154 he came back and took Damascus, completing the unification of Syria that his father had started. In Damascus he commissioned a splendid pulpit, to be installed in the al-Aqsa Mosque of Jerusalem when Allah willed its liberation.

Saladin

The fall of the Sultanate of Merv, the most powerful Seljuk state, echoes the birth of the dynasty; it crumbled into anarchy when its Turkish mercenaries revolted and Sultan Sanjar died (1153-57). Meanwhile the Sultanate of Hamadan continued to lose control of outlying areas; independent emirates were set up in Greater Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Luristan. Even the Abbasid caliph managed to regain his independence, restoring the Caliphate in central and southern Iraq (ancient Babylonia).

Egypt also fell into chaos. In 1154, a vizier's stepson murdered the young Fatimid caliph. Nearly every vizier was ousted or murdered in the chaotic years that followed. The Fatimid Caliphate was clearly dying, and outsiders watched events unfold because they knew that whoever controlled the wealth of Egypt would decide the outcome of the struggle between Cross and Crescent in the Levant. Saracen and Crusader armies got involved on opposite sides in the Fatimid struggle, first in 1164 and again in 1167. Jerusalem's King Amalric I fought in person, while a Kurdish general, Asad ad-Din Shirkuh bin Shadhi, led Nureddin's troops. The general brought his young nephew, whose name was Salah-ud-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub; we know him by his Latinized name, Saladin.

The second campaign ended when both sides agreed to make peace. Egypt was forced to pay an enormous tribute of 100,000 gold dinars a year to Amalric, and the foreign armies got out, except for a Frankish garrison in Cairo. Yet the Hospitallers, who had been expecting plunder, were not satisfied. They compelled the Franks to attack two Egyptian towns and massacre the inhabitants.(8) The Egyptians called upon Nureddin for help. A Syrian army promptly arrived, and the depleted Frankish force chose to withdraw rather than fight. The result was a disaster for the Christians; their gamble had given both victory and Egypt to Nureddin (1169).

The Syrian officers got involved in Egyptian politics immediately. They arrested the vizier, who had sided with the Crusaders, and the Fatimid caliph ordered him strangled, possibly with some prompting from the Syrians. They carried out the sentence, and Saladin's uncle became the new vizier, but the old and obese general died nine weeks later. Thirty-year-old Saladin took his place.

Saladin was now in a very questionable position. He was a devout Sunni Moslem and a servant to Nureddin, but he was also the number two man in Fatimid Egypt, a foreign and heretical power. The Abbasid caliph in Baghdad made his disapproval known, and Nureddin grew suspicious enough to confiscate Saladin's lands in Syria. Saladin in turn took tracts of Egyptian land to support his troops, and he began undermining the Fatimid government, by hiring Sunni officials to fill key posts. He finally resolved his predicament when the Fatimid caliph died in 1171. He had the name of the Abbasid caliph pronounced in Friday prayers, and the Egyptians quietly became Sunnis again. In 1173 Saladin invaded Arabia; the Hashemite Sharifs of Mecca, formerly Zaidi Shiites, acknowledged their change of masters by converting to Sunni Islam; they have remained so ever since. In 1174 Saladin conquered Yemen.

King Amalric, expecting to be the next target, played for time. He tried to make Nureddin jealous of his governor over Egypt. He also considered a closer alliance with the Assassins, who were alarmed by the fall of the Fatimids and even suggested (with no intention of following through, of course!) that they would convert to Christianity. The Templars, though, killed the Assassin envoys, choosing to forfeit the alliance rather than lose their tribute.

Nureddin continued to reside in Mosul and never visited Egypt after he conquered it, content to leave Saladin in charge of matters there. This was a mistake, for the new tail was strong enough to wag the dog. When Nureddin died in 1174 a minor succeeded him, and Saladin staged a coup, declaring himself the child's rightful ruler. Roles were thus reversed, and the Zangids became subordinates to Saladin's dynasty, the Ayyubids. In the same year Amalric died and the crown of Jerusalem went to his son Baldwin IV, a thirteen-year-old leper.

With the Turks at Iconium, Byzantium could never rest secure. In 1174 the Danishmendid Emirate broke up, allowing the Seljuks a chance to recover their strength and prosperity. Byzantium attempted to prevent unification of the interior, but the battle of Myriocephalum (1176) was another Manzikert, and although not exploited by the Turks it left the Empire defenseless. Byzantium's involvement in the Crusades ended, except as a victim, and it drifted helplessly for the rest of the century.

At first Saladin waged war against Christians and Moslems equally. The city of Aleppo did not submit to him when the rest of Syria did, and he besieged it until it finally surrendered in 1183. He fought many campaigns in northern Iraq to enlarge the territory around Mosul, only desisting when he incurred the wrath of the caliph. He skirmished with the Christians frequently, but Baldwin IV fought back with tremendous courage, and Saladin gained little there. Finally he had some run-ins with the Assassins, who tried twice to kill him, each time penetrating his tent but not his armor. As he went along he used a buy-now, pay-later strategy; use the wealth of Egypt to conquer Syria, the wealth of Syria to conquer Greater Armenia and his native Kurdistan, and the wealth of his eastern conquests to conquer Outremer. After his death, his successors, not surprisingly, found an empty treasury.

Saladin's attention was turned back to the Crusaders by the adventures of Reginald of Chatillon, who was uncommonly ambitious even among a group of people noted for that trait. A veteran of the Second Crusade, he became prince of Antioch in 1153, by marrying the widow of that kingdom's previous ruler. Three years later he claimed that the Byzantine emperor, Manuel I, had failed to pay the money he had promised to Reginald earlier, and he raided Cyprus with Armenian support. Manuel responded with a much larger army, forcing Reginald to grovel, barefoot and shabby, before the emperor's throne for forgiveness. Then in 1160, while leading a raid into the countryside of southeastern Turkey, Reginald was captured by Moslems, taken to Aleppo, and held prisoner there until 1176, when Manuel paid an awesome ransom of 120,000 gold dinars for him.

Because Reginald had been gone for sixteen years, the other Crusaders could not give him back the throne of Antioch, so instead they put him in charge of two castles east of the Dead Sea. From there Reginald carried out his boldest scheme in 1182, launching a squadron of galleys into the Red Sea to intercept the pilgrim trade. If possible, they would land in Arabia, and even attack Mecca. The raiders did great damage before they were destroyed. This horrified Moslems everywhere; Saladin called the episode "an enormity unparalleled in the history of Islam." In 1183 he invaded the Galilee region, looking for revenge. However, no battle took place, and they agreed to a truce.

True to form, Reginald broke the truce by attacking a caravan of unarmed merchants that passed near his Jordanian lands. He refused to return the loot. An outraged Saladin began a new invasion in 1187. The brave but sickly Baldwin IV had died two years earlier, leaving nobody among the Crusaders with Saladin's skill as a general. The Crusaders mustered every man they could spare--1,200 knights and a mass of infantry--and assembled them in the hills west of the Sea of Galilee. With them came a treasured splinter of wood, said to be a piece of the True Cross.

Saladin began by attacking Tiberias on the Sea of Galilee, where Count Raymond III of Tripoli had a castle. It would take a march across 25 waterless miles for the Crusaders to reach Tiberias, and Raymond told them not to go. He argued that even if Tiberias fell, he could rebuild his castle and ransom his wife and children, but if the army was defeated, the whole kingdom would be in jeopardy. Reginald and the Templars, however, argued for action. Guy of Lusignan, the newly crowned king of Jerusalem, had already been called a coward for fighting a defensive war to this point, and the code of chivalry forbade him to abandon a vassal in danger, even if the vassal did not want his help. He ordered the army to march to Tiberias.

They never made it. The going was slower than expected, thanks to the heat and skirmishes with Saladin's troops, and the day ended with them short of their goal. The decisive battle came the next morning, when they reached a twin-peaked hill called the Horns of Hattin. A brushfire set on top of the hill blew smoke into the tired Crusader's faces, and the Moslems attacked from all sides. Most of the Crusaders went down in defeat, and the piece of the True Cross was captured(9). Raymond of Tripoli escaped in a desperate charge, and died heartbroken shortly afterwards; his county went by default to a son of Antioch's Bohemond III, thus uniting Antioch and Tripoli under one family.

Saladin ordered that Guy of Lusignan and Reginald of Chatillon be brought to his tent. He asked Reginald to justify his breaches of faith, and Reginald answered more arrogantly than ever, as if he were a king instead of a noble: "But this is how kings have always behaved. I have only followed the customary path." This response provoked Saladin. Since King Guy had done him no wrong, Saladin offered him a cup of iced water--and with it, by the rules of Eastern hospitality, Guy's life. Guy drank and passed the cup to Reginald. "It is not I who have given you drink," said Saladin, who left the tent to fetch his soldiers, returned, and beheaded Reginald with his own sword.

After that it was a cakewalk for Saladin. By the end of 1187, he had taken every city in the kingdom of Jerusalem, except Tyre. Saladin offered very merciful terms to the cities that submitted. When Jerusalem fell, he destroyed the churches with their idolatrous carvings and paintings, except for the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. However, Saladin did not allow a massacre like the one Jerusalem had seen at the end of the First Crusade; he only killed the Knights Templars, since he felt he could not trust them. The great pulpit that Nureddin had prepared in Damascus was brought to the al-Aqsa Mosque (it stayed there until it was burned by an arsonist in 1969). Only Tyre and the reduced counties of Antioch and Tripoli remained to the Crusaders, slight blemishes on the face of Saladin's empire. No doubt he would have swept them away had the pope not called for a third Crusade.

The Third Crusade

The Third Crusade was the most ambitious and romantic of all the Crusades to come after the first one. The three most powerful monarchs in Europe led the Western forces: Richard the Lionhearted of England, Philip Augustus of France, and Frederick Barbarossa of Germany. This time the Crusaders were not short on money either. Crusading had always been expensive, but in the first two campaigns religious zeal took care of all practical problems. By the 1190s, however, many European families had provided three or four generations of Crusaders, and their coffers were empty. Popes and monarchs, noticing the strains, began looking for another way to subsidize Crusaders. They found it just in time for the Third Crusade. Both Richard and Philip levied a colossal tax, 10% of all movable property, from those not going on the Crusade; this became known as the "Saladin tithe."

Saladin released King Guy before the first Crusaders arrived, possibly because he wanted the Franks to have a brave but incompetent commander. He went to Tripoli, gathered his few followers, and madly charged south to reconquer his kingdom, starting with Acre. Saladin, not expecting such a move, was completely taken by surprise. He sent troops to bolster his garrison in Acre, but the Christians got there first. The result was a curious three-sided struggle, with Christians besieging the city while they were besieged at the same time.

Byzantium thought Saladin was invincible and allied itself with the Moslems. This meant that Frederick Barbarossa, who was traveling by land, had to fight his way through Byzantine territory to reach Turkey. Once there, he slaughtered Turks by the thousands, captured Iconium, and came safely to Christian territory (Lesser Armenia). Then tragedy struck--he drowned while crossing a Cilician stream in June 1190. His death broke the morale of the German army, and only a small remnant, under Frederick of Swabia and Leopold of Austria, continued to Tyre. To the Moslems, Frederick's death seemed like an act of God. The Crusade would have to depend solely on France and England after this.

The French and the English were not ready to leave Europe until July 4, 1190. Both came by sea; Philip sailed directly to Acre, while a storm forced Richard to make a detour to Cyprus. The Cypriot governor, a Byzantine rebel, underestimated Richard's strength and attacked him. Not only did Richard defeat him, but he conquered the whole island. Then he continued to Acre, arriving there in June 1191, two months after the French. Acre finally surrendered in July, after an astonishing 683-day siege.

Richard was a great warrior but a poor politician. He quarreled with Philip and Leopold over who should rule Jerusalem, and succeeded in insulting both of them. Soon after that the French and the Germans found excuses to go home, leaving Richard in sole command of the expedition. He marched down the coast and occupied Jaffa, after skillfully defeating Saladin's army at Arsuf, ten miles to the north.