| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A General History of the Middle East

Chapter 7: IN THE SHADOW OF ROME

63 B.C. to 226 A.D.

This chapter covers the following topics:

Rome vs. Parthia

Four weak kings sat on the Parthian throne during the thirty years after the death of Mithradates II. Everything north and west of Ecbatana was lost to a former vassal, Tigranes of Armenia. When the Roman Republic went to war with Armenia, Pompey marched through Parthian territory to get at Tigranes. Like Sulla and Lucullus before him, Pompey thought Parthia was just another Hellenized kingdom, and treated it with contempt. He annexed Gordyene, a small vassal state between Armenia and Parthia, opened diplomatic relations with two other Parthian vassals (Media and Elymais), and addressed the Parthian monarch with the simple title of "king." Meanwhile, Rome continued to consolidate its control over the Mediterranean basin; we covered the first stages of its expansion, from Pergamun to Israel, in Chapter 6 of this work. In 58 B.C., Egypt gave up Cyprus as the price for continued Roman protection.

This was the situation when three men, known to us as the First Triumvirate, seized power from the Roman Senate. We met one of them, Pompey, in the previous chapter; the others were Julius Caesar and Marcus Licinius Crassus. The oldest and richest of the triumvirs, Crassus became governor of Syria in 55 B.C. Pompey had conquered the Levant and Caesar had conquered Gaul, so Crassus wanted to be a conquering hero, too. Against the protests of cooler heads in Rome, he decided that his victims would be the Parthians. First he got the money to pay for his expedition, by going to Jerusalem and confiscating everything of value he could find in the Jewish Temple. When he approached the Euphrates late in 54 B.C., the new Parthian king, Orodes II, first protested that Crassus was breaking all the treaties signed between Parthia and Rome. Then he sent an ambassador, who asked whether Crassus was marching on orders from Rome (in which case they would oppose him with everything they had), or if the invasion was his idea (in which case they would pity him for his senility). Crassus replied that he would give his answer in Seleucia. The ambassador, perhaps mindful of the first emissary who took insults from Rome, held out his hand and exclaimed, "Hair, Crassus, will grow on my palm before you see Seleucia."

Marcus Licinius Crassus.

In the spring of 53 B.C., Crassus crossed the Euphrates with 40,000 men and entered northern Mesopotamia. This move surprised Orodes; most of his army was stationed in the north, because he thought Crassus would go through Armenia first (the king of Armenia was on the side of the Romans at this point). The only force near enough to oppose Crassus was 10,000 cavalry, led by a Saka named Surenas. Instead of taking Seleucia, Crassus foolishly marched into the desert, going after Surenas. Since the Romans were mostly on foot, wearing the typical heavy Roman armor and carrying swords and spears as weapons, they never caught up with the Parthian horsemen. It was the same situation Darius I had faced when he fought the Scythians in the sixth century B.C., but the Parthians were better archers than the Scythians, the Romans were slower than the Persians, and Crassus did not realize the need to withdraw until it was too late. We dignify the resulting massacre with the name "battle of Carrhae," after the town in the east Syrian desert (ancient Haran) where Crassus made his last stand. For two days the Parthians ran circles around the Romans, decimating them with an endless rain of arrows; they made their shots even more effective by aiming at Roman arms and legs, which were unprotected by armor. 20,000 Romans were killed there, another 10,000 were captured and sold into slavery, and only one fourth of the Romans saw home again.

Crassus was killed at Carrhae, but the details are not clear. In the middle of the battle he saw a Parthian ride by, carrying the head of his son; no doubt that ruined his day. As for what happened to Crassus himself, the most popular story is that the Parthians captured him alive, and they cured his thirst for gold by pouring molten gold down his throat! Crassus did earn for himself a place in history--as the worst general the ancient world ever produced. It took a generation for Rome to get over the disaster at Carrhae.

Surenas enjoyed his triumph briefly; Orodes distrusted generals who can beat 4:1 odds and had him murdered. Now that the time looked ripe, he assigned his son Pacorus the task of depriving the Romans of Syria. However, Pacorus was an inexperienced youth at this point, and the Parthian army, despite the improvements made, was still poor at organizing long campaigns or taking fortified cities. After a raid failed, Pacorus launched a major invasion in 51 B.C., this time capturing and holding all of Syria for several months. He had to give it back, however, when he was falsely accused of treason; Orodes recalled and nearly executed his son. As Orodes quarreled with Pacorus and Caesar quarreled with Pompey, the Syrian war petered out. Armenia and two tribes in the Caucasus (the Iberians and the Albani) passed out of Roman control, but a decade passed before Parthia got a chance to invade the west again.

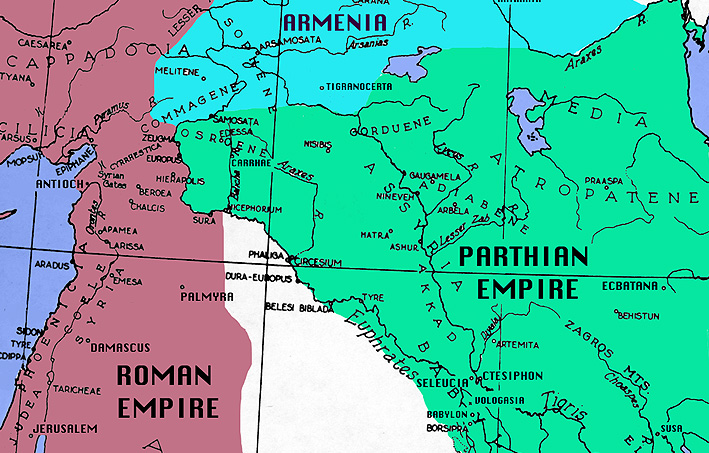

The war zone, where Rome, Parthia and Armenia met.

When Pompey was defeated by Caesar, he considered taking refuge among the Parthians, but he was killed before he could try it. Pompey's death left Caesar absolute master of the Roman world. One year later (47 B.C.) he came, saw, and conquered Pharnaces, the upstart king of Pontus. Having Pharnaces for an opponent, and not his father Mithradates VI (see Chapter 6), certainly made Caesar's job easier. Mithradates would have been eighty-five years old if he had lived long enough to fight Caesar, but to use an example from modern European history, the difference between Mithradates and Pharnaces was like the difference between Napoleon I and Napoleon III. Caesar was planning to invade Parthia and avenge the defeat of Crassus when he was assassinated in 44 B.C.

A leader in the conspiracy against Caesar was Gaius Cassius Longinus, the general who had defeated the Parthians in the first campaign of Pacorus. Cassius proclaimed himself proconsul of Syria, and put Antipater, the Idumaean noble from the previous chapter, in charge of Israel. Cassius began to raise an army to fight the new rulers of Rome, the Second Triumvirate, and Antipater was given the task of gathering the money needed for the project. Resentment against Antipater resulted in his poisoning by Malichus, a man who posed as a friend of Antipater while planning to seize the government for himself. One year later (42 B.C.), two members of the Second Triumvirate, Mark Antony and Octavian, defeated and killed Cassius in Macedonia.

Mark Antony inherited Caesar's Parthian project. Pacorus, however, acted first, by concluding an agreement with Quintus Labienus, an officer among Caesar's assassins who went over to the Parthians to avoid being arrested. In 40 B.C. they invaded Rome's Asian territories with startling success: Labienus took all of Asia Minor, while Pacorus conquered the Levant. In Judaea Antigonus, the son of Aristobulus II, deposed his uncle John Hyrcanus II, captured a son of Antipater, Phasael (who committed suicide), and proclaimed himself the newest (and last) Maccabean ruler. He had Parthian assistance, but his victory was not complete, for another son of Antipater, Herod, escaped to Rome; there he so impressed Antony and Octavian that they named him king of the Jews, though he was an Idumaean.

In two years the Parthians had nearly restored the boundaries of the old Persian Empire. However, this success was even more quickly undone. Disagreement between the two generals weakened their combined effect. In 39 B.C. a Roman counterattack killed Labienus and recovered Asia Minor. One year later Pacorus got himself killed in Syria, when he attacked a Roman camp that he had been led to believe was undefended. Herod personally led another Roman army to retake Jerusalem, capturing the holy city after a five-month siege.

Before the year was up (37 B.C.), Orodes lost his mind and abdicated in favor of a savage son, Phraates IV, who then killed his father and some thirty brothers to secure the throne. The rest of his reign was so harsh that Mark Antony believed Parthia would be an easy conquest. In the spring of 36 B.C., he led 100,000 men into the Caucasus, Armenia and Atropatene. This army may have looked unstoppable, because it was larger than anything Phraates had on the scene, but Antony committed a major blunder by dividing his force, leaving part of it in the rear to guard the baggage and siege engines. These Phraates found and successfully attacked, destroying Antony's supplies and equipment. Harassed by the Parthian cavalry, unable to forage for supplies, unable to make a truce with his enemy, and facing a tough winter, Antony had no choice but to retreat. At that point, the king of Armenia switched sides, going over to the Parthians; this meant that the only escape route for the Romans went through enemy territory. It was a death march, with men dropping from hunger, disease, and Parthian arrows. 35,000 men--more than one third of the army--were lost in that retreat. Most humiliating of all, Antony retreated without fighting a single battle with the enemy, meaning those men had died in vain. Finally the surviving legions crossed the Euphrates into Syria, and the Parthian pursuers suddenly unstrung their bows, praised the Romans for their courage, and went home. Mark Antony headed for Egypt and the soothing attentions of Queen Cleopatra.

After this fiasco the Romans finally gave their eastern rivals the respect they deserved. Mark Antony prepared to fight the Parthians again by building a fleet of 400 ships, but the rematch never took place. Because the Parthian Empire did not control any land on the Mediterranean or Black Seas, those ships would have been useless anyway; Antony used them instead in his showdown with Octavian, the battle of Actium (31 A.D.). Then the Roman Republic became the Roman Empire, with Octavian, now known as Caesar Augustus, as its first emperor. The most embarrassing bit of unfinished business left to Augustus was his adoptive father's declared intention of marching against the Parthians. Augustus saw that Parthia defended itself well but had no power to sustain an offensive. Instead of starting another war, he was satisfied with reasserting Roman authority over Armenia and the Caucasus (20 B.C.); he also persuaded Phraates to return the standards captured at Carrhae. These moves restored Roman prestige and allowed Augustus to ignore the hawks who called for a radical solution to the Parthian problem. From now on the Euphrates River and the Arabian Desert became the official boundaries between the empires.

In the East, Augustus made his priority the Romanization of the areas already conquered. Fiefs that had been the reward of loyalty in more troubled times were turned into directly-ruled provinces, now that they had become peaceful and profitable: Rome absorbed Egypt in 30 B.C., Galatia in 25, Paphlagonia in 6, and Judaea in 6 A.D. Succeeding emperors continued the process: Tiberius annexed Cappadocia, Caligula took Mauretania (modern Morocco), Claudius took Thrace and Lycia (in SW Asia Minor), and Nero added Pontus. They divided Ituraea between the province of Syria and the Herodian kingdoms. Tiberius annexed Commagene (a small buffer state on the west bank of the Euphrates), but Caligula restored it and gave it part of Cilicia.

Herod the Great

Herod attempted to win the favor of the Jews by publicly observing the Law. He made every effort to build and adorn his realm. Strato's Tower, a small town on the Mediterranean, was enlarged and renamed Caesarea in honor of Caesar Augustus. He rebuilt Samaria as Sebaste, named after the wife of Augustus.

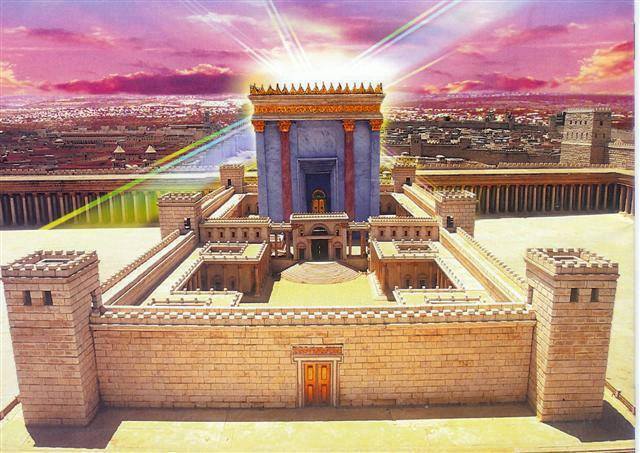

The Temple stood in Jerusalem as an empty shell for a generation after Crassus looted it. In 20 B.C. Herod began to remodel and adorn it, so that it would compare favorably with the pagan temples the Greeks & Romans had built. This project took 46 years, to be completed shortly before Jesus started teaching in there. Herod also built palaces in out-of-the-way places to hide in when life in Jerusalem looked dangerous: the Herodium, located between Bethleham and Hebron, and Machaerus and Masada, both perched on high places overlooking the Dead Sea.

The second Temple, after Herod got done enlarging it.

To make friends with the Hasmoneans, Herod married two of them: Mariamne, the granddaughter of John Hyrcanus II, and Miriam, the granddaughter of Aristobulus II. Though they had children they never got along well, probably because Antipater had killed Aristobulus, and Herod would follow in his father's footsteps before long.

Despite all he could do, Herod remained an unpopular king. His paranoia and personal cruelties outweighed his piety, and his Idumaean blood made him suspect anyway. Jews also distrusted Herod when they thought about the Temple. If King David could not build the first Temple because his hands were too bloody from military campaigns, then how clean could the hands of Herod be? When Herod set a golden eagle--the symbol of Imperial Rome--on the Temple gate, radical Jews called it proof that Herod served not God but Augustus, and tore it down at the cost of their own lives.

As he grew older, Herod grew more mentally unstable. Domestic troubles plagued him; even the crown prince, Antipater III, hated him. He murdered Mariamne, the favorite of his ten wives, her grandfather John Hyrcanus II, her brother Aristobulus, and several of his own children. The killing of the infants in Bethlehem when he heard of the birth of Jesus was only the last of many atrocities that he committed (Matt. 2:16).(1) When Augustus learned of these acts, he noted that Herod did not eat pork, in observance of Jewish law, and remarked: "It is better to be Herod's hog than to be his son!"

Although history calls him "Herod the Great," he knew that his death would bring rejoicing among the Jews. On his deathbed he actually ordered that all leaders of the Jews be executed at the time of his death so that there would be mourning throughout the land, if not for him. Happily, nobody carried out this murderous project (only Antipater III was killed), and there were few mourners when Herod died in 4 B.C.

The Tetrarchy

The Romans gained control of the Holy Land gradually, and were never completely successful at ruling it. As a result, the land saw many changes of personnel and political organization. The will of King Herod, changed at the last minute, specified that the eldest surviving son, Herod Archelaus, would become the next king, but Archelaus was very unpopular, so a delegation of fifty Jews sailed to Rome and protested, urging instead that power be shared between a religious authority (namely the Sanhedrin) and a Roman procurator (governor). Herod's sister, Salome, also went to Rome and denounced Archelaus, declaring that any one of her sons could do a better job.

Augustus chose to compromise; he crowned Archelaus, but only gave him half his father's kingdom (Judaea, Samaria, and Idumaea). The rest of the kingdom was partitioned four ways, and they called the entire political framework the Tetrarchy, suggesting (incorrectly) that Israel was divided into four equal parts. The second surviving son of Herod, Herod Antipas, received Galilee and the east bank of the Jordan, or Peraea. A third son, Herod Philip, ruled the southwestern corner of Syria (Old Testament Bashan, today's Golan Heights). An apparently unrelated prince, Lysanias, ruled the fourth part of the tetrarchy, a small district called Abilene in eastern Lebanon; this area had not been part of Herod's kingdom. Salome got three cities: Azotus (ancient Ashdod), neighboring Jamnia, and Phasaelis (a town about 15 miles north of Jericho); upon her death they passed to Livia, the wife of Augustus, and eventually to Tiberius. Augustus effectively put Archelaus on probation, stating that if he ruled his lands well Rome would later make him king over Herod the Great's entire territory.

Still, Archelaus began at once to abuse his position, taking on more royal titles than a subservient ruler should have. He suppressed dissent brutally; for example, he killed three thousand Jews in the Temple during one Passover festival. In 6 A.D. Augustus banished Archelaus to Gaul; because the Romans had not yet conquered Britain, Gaul was as far from Israel as Augustus could exile him, without leaving the Empire. The territory of Archelaus now came under the direct rule of Coponius, the first procurator. In the sixty years between Archelaus and the Jewish-Roman War, no less than fourteen procurators tried to keep the lid on Judaea; the most famous is Pontius Pilate, who governed from 26 to 36 A.D.(2)

One verse in the New Testament mentions Archelaus, and it reflects his character perfectly. When the family of Jesus came back from their refuge in Egypt, Joseph did not take the direct road to Nazareth via Jerusalem; instead he chose a roundabout route to avoid the territories of Archelaus (Matt. 2:22).

Herod Antipas was sly, ambitious, and luxury-loving, but not an able ruler like his father. At first he was married to the daughter of Aretas, the Nabataean king. Later he intrigued with and eloped with Herodias, the wife of his half-brother Philip, although both of them were married at the time. This made for an incredibly tangled family tree, since Herodias was the granddaughter of Herod the Great, sister of the future Herod Agrippa I, and both niece and wife to Herod Philip. When John the Baptist denounced this scandal, Herod imprisoned and beheaded him (Matt. 14, Mark 6, and Luke 9).

Antipas was also aware of the ministry of Jesus. When he first heard about it, he wondered if John the Baptist had come back from the dead; Jesus replied by saying, "Go ye and tell that fox, behold I cast out devils" (Luke 13:32). When Jesus was put on trial in Jerusalem, Antipas had the Messiah sent to him, asked to see a miracle, and returned him to Pontius Pilate when he got no answer.

Herod Philip's territory was a non-Jewish area that he succeeded in Romanizing. He built a marble temple to Augustus above the older city of Panias, which he rebuilt under the name Caesarea Philippi. He enjoyed a peaceful reign of nearly thirty-eight years (4 B.C.-34 A.D.) and appears to have been the best of all the Herods.

Prelude to the New Testament

In the civil war between Caesar and Pompey, the Jews favored Caesar; Pompey had taken too many liberties with Judaism. Afterwards Caesar rewarded them with many favors, such as reduced taxes and autonomy in local affairs. The Jews were not required to worship the emperor as a god, the way Rome's other subjects did, though they did gratefully offer prayers & sacrifices for his well-being. Augustus, Tiberius and Claudius continued this tolerance, but less prudent emperors like Caligula and Nero insisted on being worshiped, and viewed those who did not do so as disloyal. Because many Jews never accepted the idea of being ruled by pagan foreigners, trouble turned into unrest, and Judaea got a reputation as an unruly province. Pontius Pilate, for example, attempted to introduce busts of Emperor Tiberius in Jerusalem and was forced to stop when Jews who opposed the measure started a riot (they saw the statues as pagan idols). The Romans had a justly earned reputation for cruelty, but when the alternatives are considered, Roman rule appears to have been the best realistic possibility. Radical Jews never understood this, and as a result the tragedy known as the Jewish-Roman War took place at the end of Nero's reign.

Though many Jews saw this period as an unhappy time to live in, Judaism did grow, in both numbers of followers and in diversity of sects. Estimates of the numbers of Jews living around 1 A.D. range from several hundred thousand to as many as five million. Whatever the figure was, more than half of them still lived in Iraq, as subjects of the Parthian Empire. In the west, they appear to have made up around one tenth of the Roman Empire's population. It takes more than just large families to explain how the Jewish community reached this size, and it probably came about by making converts (proselytes) from the surrounding Gentile population, especially during the Greek era covered in the previous chapter. Exact details are not available, though.

The two main Jewish sects of this time, the Pharisees and the Sadducees, split in the early second century B.C. Under Roman rule new groups, many with political goals, emerged in the Holy land. Most wanted an independent Jewish state, and all wanted a society where the Torah was observed properly. Many expected liberation under the leadership of the Messiah, who would come, pronounce the Last Judgment, resurrect the saints who had lived in the past, and turn Israel into God's invincible kingdom on earth. As a result this was a time when they wrote much apocalyptic literature, in the style of Old Testament prophets like Daniel.

One group of Jews who thought they were living in the last days were known as the Essenes. Members of this sect got away from Jerusalem and set up a hermit community at Qumran, on the shore of the Dead Sea, where they hoped to stay out of the major conflicts of the day while they prepared for the time to come. Here they owned everything in common, wore white robes instead of Greco-Roman fashions, and did their best to live virtuous lives, but they were not a true forerunner to the monastic movements that Christianity later produced; for one thing, they did allow marriage. Some scholars believe that John the Baptist may have been one of them.

The Essenes never numbered more than about 4,000, and they disappeared in the Jewish-Roman War when the Romans wiped out Qumran, on the road from Jerusalem to Masada. Before the mid-20th century, all we knew about them came from contemporary writers like Josephus, Philo, and Pliny the Elder. Then in 1947 we discovered the library of the Essenes, the famous Dead Sea scrolls, in a cave at Qumran. Written in Hebrew & Aramaic on parchment & papyrus, these texts are the oldest portions of the Bible ever found. Also found was the Manual of Discipline, a guide to the "children of light" on how to maintain righteousness in their struggle against the forces of darkness.

Contemporary with the Essenes were the Zealots, whose party was founded in 6 A.D. Unlike the Essenes, however, the Zealots got fully involved in Judaean politics. These first-century radicals refused to pay taxes to the Romans and advocated the violent overthrow of the regime, arguing that God was the only rightful master of Israel. If withholding tribute meant war, then they were fully prepared to wage it. Using tactics very similar to those of modern terrorists, they kidnaped or assassinated Roman officials and those Jews who got along with the Romans. Josephus, betraying his Roman bias, called them Sicarii (dagger men), because of their favorite weapon. Josephus and the Book of Acts both mention three Zealot-led revolts in the first century: Judas of Galilee (6 A.D.), Theudas (44), and Benjamin "the Egyptian" (60). The Romans stamped out these revolts and crucified the rebels with their famous efficiency. They may have seen the crucifixion of Jesus as the nipping of another rebellion in the bud.

A political group with more moderate views was called the Herodians. At first they apparently viewed Herod the Great as the Messiah. After Herod died, their objective became the establishment of an independent Israel with Herod's descendants ruling over it. Unlike the Zealots, however, they did not refuse to pay taxes to the Romans.

Finally mention should be made of Rabbi Hillel, the foremost Jewish scholar in the generation preceding Jesus. Born in Iraq, he came to Israel as a young man to pursue advanced studies of the Scriptures under the guidance of the Pharisees. No proper biography is available on Hillel's life and accomplishments; instead several legends have formed around what he said and taught. The most popular story tells how a young Greek came to Shammai, Hillel's chief rival, to mock the legalisms of Judaism; he dared someone to teach him the Torah while he stood on one foot. Shammai dismissed the fellow out of hand, but Hillel took up the challenge, summarizing the law as follows: "What is hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor. This is the whole Torah; the rest is commentary. Go and study." The Greek was so impressed that he converted.

Hillel's version of the golden rule echoes through his other teachings; in fact, his outlook on the Torah was that one could learn about man's relationship with God by examining his relationships with other people. His extensive searching of the Scriptures, to find out how they apply to daily life, mark him as the first of the rabbinical scholars whose writings would one day be compiled to form that collection of traditions and commentaries known as the Talmud.

or, A Long Time Ago, In a Galilee Far, Far Away . . .

The most important religious development during this era was the birth of Christianity. The only detailed account that exists of its founder, Jesus of Nazareth, is in the first four books of the New Testament. Since most readers of this work will probably come from a Christian background, or be at least familiar with the story of Jesus, most of what is in the Gospels will not be repeated here, except to explain the effects on Middle Eastern history; it is also safe to say that nobody can improve on the original story given to us by Matthew, Mark, Luke and John.

At first Christianity was a reaffirmation of the Middle Eastern view concerning the nature of the world and man. The teachings Jesus gave on salvation and the coming of the kingdom of God were a fulfillment of what the Jewish prophets had taught centuries earlier. The new faith also generated an idea that was enormously appealing--that God himself had come to earth and wanted to have a personal relationship with His people. The original twelve Apostles of Jesus also expected him to judge the world, right all wrongs, and establish Israel as an everlasting kingdom. When instead the Romans arrested and crucified Jesus on a trumped-up charge of sedition (29 A.D.), it looked like everything he did was for nothing. However, a few days later the dispirited Apostles gathered in an upstairs room and suddenly felt again the heartwarming presence of their Master. Now they were convinced that the death of Jesus on the cross was not an end but a beginning. If they doubted it before, now they knew that Jesus was the Messiah prophesied in the Old Testament, and that he would save whoever accepted him as Lord before he returned in glory on the long-awaited day of judgement. During the next seven weeks five hundred of his followers saw their resurrected teacher before he left them for the last time, giving them a final command to spread the Gospel to "Judaea and Samaria, and to the uttermost part of the earth."

The good news could not be kept a secret. On the contrary, the Apostles bubbled over with excitement and told anyone who would listen what had happened and was going to happen. Peter, for example, who had denied his master when the Romans arrested Jesus, now proclaimed him with the courage of a lion. Initially these early Christians stayed in and around Jerusalem, but when Herod Agrippa I and various Jewish leaders tried to stamp out the new movement, they moved their headquarters to Antioch in Syria, and the number of people who heard the Gospel grew exponentially.

At this point the early Church made a convert who would become the greatest missionary of all. This was Saul of Tarsus, a young Pharisee who had distinguished himself by his outstanding adherence to the Law and his persecution of the first Christians. Saul chased them from Jerusalem but was converted through a vision of the risen Christ on his way to Damascus. Temporarily blinded, he found his way to a Christian named Ananias, and when cured he began to preach the Gospel vigorously. Before long his former friends made plots against his life, and Saul had to escape Damascus by being lowered over the city wall in a basket. Saul wandered in Arabia for a while and then returned to Jerusalem, but here he faced a double problem: Christians who feared his conversion was not really genuine, and Jewish leaders who now viewed him as a traitor. He went home to Tarsus and lay low for about a decade, until the Church of Antioch called him back into the ministry. From this point on we call the rabbi from Tarsus by the Greek version of his name, Paul.

Using Antioch as his starting base, Paul now went on three epic missionary journeys through Asia Minor and Greece, which dominate the second half of the Book of Acts. Wherever he went, he first found the nearest synagogue to preach in, and when the Jewish congregation would not have him, he took his message to the Gentiles outside. Previously the Apostles had converted a handful of non-Jews (e.g., Philip and the Ethiopian eunuch, Peter and the Roman centurion Cornelius), but Paul was more dedicated to this ministry than anyone else; he even brought Peter back into line when Peter slipped into his old habits and associated only with Jewish Christians (Galatians 2:11-16). It was Paul who offered the Gentiles salvation without the necessity of following the 613 commandments of the Torah (plus all the rules the Pharisees & Sadducees had tacked on more recently). Being fluent in Greek, he was also able to express the message of Jesus in terms his Greek listeners could understand. Over time, Paul's activities caused a total change in Church demographics--by the end of the first century most of its members were non-Jewish, and would remain that way to this day.(3)

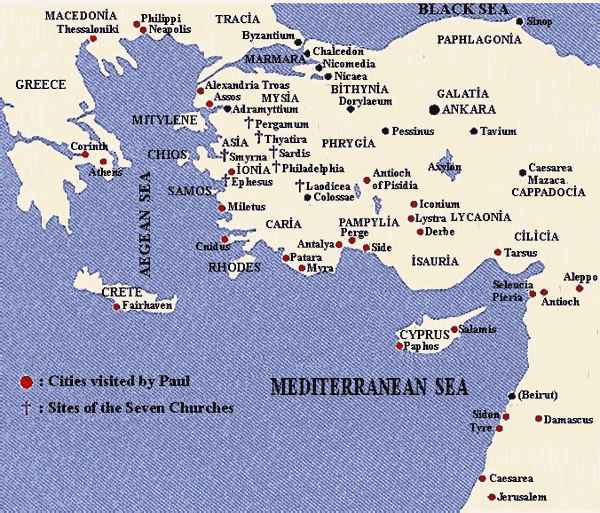

The area where Paul was active on his three missionary journeys. Not shown are Malta and Italy, where he went in the last two chapters of Acts.

Paul had special freedom of movement because he was born a Roman citizen; that opened doors for him that were closed to other Jews. He concluded his third journey in Jerusalem, bringing money he had collected for the poor Christians of the mother church. When he arrived, he was seized by a Jewish mob and would have been lynched, had not the Romans arrived just in time. Paul had to stand trial to refute the charges against him, but rather than face a biased court in Jerusalem, he appealed to the Roman Emperor Nero for justice. He was sent to Rome as a prisoner, surviving a shipwreck at Malta on the way. After spending two years in Rome (the Book of Acts ends at this point), Paul was probably released to conduct some more missionary work; Romans 15 mentions trips to Spain and Illyricum (Albania) that he planned and possibly carried out. Finally around 64 A.D. he returned to Rome and became a martyr in Nero's first persecution of the Christians. Because of his Roman citizenship he got one last privilege; he died of beheading, rather than on the cross.

The Journeys of the Apostles

Paul was not the only Church leader to travel extensively, but his travels are by far the best documented. Each of the twelve Apostles made journeys, motivated by Paul's success and by the "great commission." There are many reasons for the lack of detailed records:

1. The early Christians, except for Luke, the author of Acts, did not see a need to write a history of the Church. Most of them expected Jesus to come back within their own lifetimes, and they did not think they were creating an institution that would last for ages on this world.

2. Secular historians did not see Christianity as a significant movement--at first. Because Christianity's members came mostly from the poor/lower class elements of society, those with power and wealth ignored it for a long time. Only two non-Christian historians even bothered mentioning the name of Jesus in the first century: Josephus and Tacitus.

3. The Church did not research the stories of the Apostles until it was politically motivated to do so, in the fourth century. At this point the Church of Rome and the Eastern churches were starting to become rivals for the leadership of Christendom. Near the end of his career, the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great built the "Church of the Twelve Apostles" in Constantinople, to bury the relics (bones and other body parts) of all the Apostles inside. A search was made to find as many relics as possible; he successfully recovered most of the remains of Andrew, and those of Luke and Timothy (the latter two were not really Apostles, but close enough to use as substitutes). Rome held the bones of Peter and Paul and was not willing to part with them, so instead Constantine built a chapel over them in Rome that would one day become St. Peter's Cathedral. Then he died, and was buried in his unfinished church. Constantine's historian, Eusebius, claims that he really wanted to have his tomb surrounded by those of the Twelve, so that people would think of him as a thirteenth Apostle!

To fill the many existing gaps, we must rely on Church traditions/legends. Of course these are not the most reliable source of historical data, but where two or more separate accounts tell us the same thing (e.g., Peter died in Rome, Thomas went to India) we can guess that we are on safe ground. Also, remember that each Apostle had to go somewhere, so if only one country claims an Apostle as its missionary, he probably did go there. The rest of this section will act on those assumptions.

Simon Peter

Peter gets more attention in the New Testament than the other Apostles, and is the most interesting, since his impulsive personality, with all its strengths and failings, is clearly visible. The first twelve chapters in the Book of Acts chronicle his early missionary activities: his speech explaining the miracle at Pentecost; his denouncement of Ananias & Sapphira, who tried to deceive the Church, and of Simon the magician, who thought he could buy the power of God; his trip to Samaria to meet the church founded there by Philip; and the conversion of Cornelius. At this point Paul replaces Peter as the principal figure in Acts, but two epistles from Peter are included near the end of the New Testament.

Here the traditions take over. It is fairly certain that Peter visited Corinth shortly after Paul did, since he is mentioned in the two epistles to the Corinthians. Then he appears to have spent several years in Babylon (44-49 A.D.?); his first epistle is addressed from there. Some believe that when he said Babylon he meant Rome, as John did when he wrote the Book of Revelation, but this is unlikely, since Peter had no reason to disguise the name of Rome this early. There was a Christian community in Rome before 50 A.D. (the Emperor Claudius declared the Roman Christians a public nuisance and had them expelled--Acts 18:2), but it appears to have gotten started before any of the Apostles went there.

A few traditions suggest that Peter visited Gaul and even Britain, though these are unreliable. At the minimum he sent missionaries in that direction. Finally he ended up in Rome, and like Paul he became a martyr to Nero's persecution of the Christians. For nine months he was kept in the lower chamber of the notorious Mamertine dungeon; imagine being chained standing up against a wall in a cell so far underground that light never gets in, a place with a horrible stench because it had not been cleaned out in over a century. Despite all of this, Peter's faith remained unshaken, and he converted two of his jailers, along with 47 others. Then in 67 A.D. he was brought out and crucified in Nero's circus. He felt unworthy to die in the same manner of Jesus, and asked that he be crucified upside down. Ironically, the Romans granted this last request.

Andrew

Andrew was the first of the Twelve called by Jesus; he was a follower of John the Baptist previously. He is not mentioned in Acts after Pentecost, though surely he was active in the ministry. However, the traditions revolving around him are impressive. It appears that he accompanied his brother Peter to Antioch, then continued north by himself, reaching the Black Sea at Sinope. He traveled around the Black Sea in a counterclockwise direction, bringing Christianity to Armenia, Colchis (Georgia) and Scythia (the Ukraine); consequently the Russians made him their patron saint, almost a thousand years later. Upon his return he spent some time with John at Ephesus.

Next Andrew crossed over into Europe via Byzantium. In Greece he converted a noblewoman, Maximilla, and she promptly became estranged from her husband, a proconsul named Aegeates. The enraged governor had the Apostle scourged and crucified, on an X-shaped piece of wood that we now call "St. Andrew's cross." The generally accepted date of Andrew's martyrdom is 69 A.D.

James the Son of Zebedee

Of the three Apostles that were closest to Jesus--Peter, James and John--we know the least about James. He disappears for a time after Pentecost, and then in 44 A.D. he became the first Apostle to suffer martyrdom, executed on order of Herod Agrippa I (Acts 12:1-2). Several traditions have sprung up claiming that James ministered to the Jewish communities in Sardinia & Spain; this is unlikely, when one considers that only 15 years elapsed between the Master's death and his own, but not impossible; traveling across the Mediterranean was relatively easy during the Pax Romana.

Whether or not James made the long trip to Spain, it appears that most of his remains did in the seventh century. Then many bones identified as his turned up in Spain, but not his head; the story was that his skull was hidden somewhere in Jerusalem to keep it out of the hands of the Persians, who invaded the Holy Land in 614, while the rest of his relics were spirited away to more permanent safekeeping in Spain. Over those bones they built a shrine that grew into a cathedral, and then a city, named Santiago de Compostela. At the height of the Middle Ages, more pilgrims visited Compostela than any other site west of Rome. Even then there was some doubt about whether the bones of St. James were authentic, but the Catholic Church still accepts them as the real thing, since no rival claim exists elsewhere.

John

The "disciple whom Jesus loved" was the only one of the Twelve who died peacefully. He is mentioned extensively in the Gospels and at the beginning of Acts, but he appears to have been the last Apostle to leave Jerusalem. Whatever the reason, we do not have any record of him going anywhere else before the Romans destroyed Jerusalem in 70 A.D. After that he turns up in Ephesus, adding his encouragement and support to the church Paul started there. During this time he probably wrote the gospel and the three epistles that now bear his name. Then the egotistical Domitian became emperor in 81. Like Nero, Domitian didn't want to wait until after his death to be worshiped as a god, and persecuted anyone who felt otherwise. John was exiled to the Aegean island of Patmos, and there he wrote the famous Book of Revelation.

When Nerva became emperor in 96, he declared a general amnesty for all of Domitian's victims. John--now in his eighties or nineties--returned to Ephesus, and became the bishop in charge over all the churches in the province of Asia. He lived until the reign of the Emperor Trajan, around 100 A.D.

Philip

This Apostle had a Greek name, meaning "lover of horses," and may have come from a Hellenized family. He appears to have been a close friend of John, because John often mentions him in his gospel; later, in the eighth chapter of Acts, we see him as a pioneering missionary to Samaria and Gaza. After that the only detail every theologian agrees on is that he concentrated his ministry in central Asia Minor--Galatia and Phrygia--and died a martyr's death in the Phrygian city of Hierapolis. Many questions exist about where else he went. One tradition sends him to Scythia. Several others link him to France, or Gaul as the ancients called it. It appears that somebody confused the names "Gaul" and "Galatia," since both have peoples of Celtic ancestry. However, as with James in Spain, having gone as far as France was possible for Philip. The excellent system of Roman roads, coupled with reliable sea transport, the use of Latin and Greek everywhere, and the near-universal peace of this era, all made transportation simple.

Bartholomew

We know little about Bartholomew, who is also called Nathaniel in the first chapter of John's Gospel. Traditions concerning him differ considerably, and have him preaching in India, an Arabian oasis, Iran, Phrygia, and Armenia. However, the source of much of these stories, the "Gospel of Bartholomew," is unreliable, and was considered a heresy as early as the sixth century. Without that, we can write a plausible biography as follows:

Bartholomew teamed up with Philip at first, and the two went to Hierapolis in Phrygia. There they healed the wife of a Roman proconsul and she became a Christian; her husband ordered the crucifixion of both missionaries. They crucified Philip, but somehow Bartholomew escaped and went east to Armenia, around 60 A.D. He spent the next eight years near the Caspian Sea, before suffering martyrdom himself, in the city of Albanopolis (modern Derbend in Azerbaijan). Traditions disagree on whether he was flayed, beheaded, crucified, or suffered more than one of those fates.

Thomas

We call Thomas "doubting Thomas" because he did not believe it when the other Apostles first told him that Jesus had risen from the dead. This is probably unfair, for how many of us would have done the same thing in a similar situation? Later Thomas himself saw his resurrected Lord and believed. Afterwards he showed his new faith and courage by traveling early, and possibly farther, than any other apostle.

The traditions concerning Thomas are impressive indeed; they unanimously agree that he went east as far as India, and many historical facts back them up. According to the Church of the East (also known as the Nestorian, Assyrian, or Chaldean Church), he first went to Babylon, staying there long enough to found a congregation. When Peter arrived to take his place (44 A.D.) Thomas moved on. He went through Iran and into the Indus valley, where he converted a local king named Gondophares and his son Gad; coins have been found mentioning Suren kings by those names. A few years later the Tokhari came out of Central Asia, overran the Indus and founded the kingdom of Kushan, so Thomas traveled south to the Malabar coast, around 52 A.D. Here he converted many Hindu families, built seven churches, and crossed over to the east coast, where an unfriendly Brahman (Hindu priest) ended his career with a lance (60 A.D.).

Before it emigrated to Israel a few years ago, there was a Jewish community in south India at Cochin. A deed to the land their synagogue was built on dates to 72 A.D. Thomas very well could have witnessed to this group. In Mylapore, a suburb of Madras, are a very old house, chapel and tomb associated with him; at least they contain first-century style bricks.

Despite the missionary zeal of Thomas, his work, like anything made by man, was subject to change, decay, and corruption. During the next few centuries a Hindu revival erased every trace of the fledgling Christian community in northern India. The same fate might have befallen the south Indian believers, but news of their plight reached the Patriarch of Syria. In the fourth century he sent missionaries, led by one Thomas of Cana, to encourage them and let them know that they were not alone. After that various leaders in the Church of the East went there from time to time, and in the modern era Western clergymen have done the same thing. The Mar Thoma Church (St. Thomas Christians) still survives today, and claims a small but significant number of Christians in modern India.

Matthew

Tradition has Matthew living in the Holy Land for about 15 years after the resurrection. Presumably during this time he wrote the gospel that bears his name. This gospel was originally meant for Jewish readers, because it contains many examples of Old Testament prophecies that Jesus fulfilled, but like the other Apostles he ran into trouble with the Jewish establishment and found the Gentiles more willing to hear what he had to say.

Traditions have him going in two directions after 44 A.D.; some send him to Persia, while others make him the missionary to Ethiopia. Of these, more writings back up the African case. He could have gone east first, but if he did so, he did not stay there for long; the traditional literature that covers his eastern trip comes from Europe, not Asia. He is credited with spending at least 23 years in Egypt and Ethiopia combined, witnessing before kings and dying in Egypt around the year 90. The stories of his death differ considerably; some say he was beheaded, while others claim a peaceful end. His body is now buried in Salerno, Italy, under an 11th-century cathedral, but nobody knows how or when it was found.

James the Son of Alphaeus

James, Matthew's brother, is often called James the Younger or James the Less to distinguish him from Zebedee's son, who we call James the Great. He is one of the Apostles we know the least about, thanks to a confusion of identities. This happened because there is a third James mentioned in the Gospels who was a younger brother of Jesus. To protect the doctrine of Mary's perpetual virginity, the Catholic and Orthodox churches asserted that James the brother of Jesus was the same as James the Less, and he was not really a blood relative of the Messiah. They tried to explain how they could call a son of Alphaeus a "brother" to the son of Mary; eventually many theologians agreed that James, like Jesus, had a mother named Mary, and that the two Marys were sisters! This violated common sense--nobody gives two or more of his children the same name--but for want of a better explanation it had to do. The result was that the traditions concerning James the brother of Jesus were wrongly attributed to James the Less. Likewise the Armenian monastery in Jerusalem houses some first-century bones identified as those of James the Less, but more likely they are relics of James the brother of Jesus.

Now that we have taken care of that point, here is what we have on the two James. James the brother of Jesus was not a believer while Jesus was alive, but after the resurrection Jesus made a special appearance to prove to James that what he said was true (1 Cor. 15:5). Although not one of the Twelve, he became leader of the Church in Jerusalem, theoretically outranking the Twelve. He is mentioned as taking part in the conference concerning the acceptance of Gentile converts (Acts 15), and at some point wrote the epistle named after him. He was martyred around 53 A.D., when a mob led by the Sanhedrin threw him off the top of the Temple.

When the legends concerning James the brother of Jesus are attributed to the right person, there is little left for James the son of Alphaeus. The only tradition left that has a ring of probability comes from the Syrian Church. It states that when the Antioch church was founded, James the Less became its first leader. Years later he returned to Jerusalem and was stoned to death by the mob. His relics went to the Church of the Twelve Apostles in Constantinople during the mid-sixth century; in 572 they were moved to the Church of the Holy Apostles in Rome.

Thaddaeus

Thaddaeus had three names; in other parts of the Gospels he is called "Lebbaeus" or "Jude." (He was not the Jude that wrote the epistle named Jude, though--that was probably another brother of Jesus, who humbly called himself no more than "the brother of James.") Luke calls him "Judas the son of James," and this may be a reference to James the Great, since the other two figures named James were probably too young to have sons while Jesus was alive on earth.

The Armenian church claims that five of the Apostles visited Armenia during their journeys, and that Thaddaeus was the first to arrive; Armenia's long relationship with Christianity started with the pioneering church he built in the city of Edessa, about 35 A.D. Then others (Bartholomew, Andrew, Simon, and Matthias) came to Armenia, and Thaddaeus moved on. After that he made some side excursions to the east, but he always came back to Armenia, using it as a home base. Wherever he went he seems to have been in the company of another Apostle; Thomas in Iraq, Bartholomew in Armenia, and Simon in Azerbaijan. He was finally martyred with a javelin or with arrows alongside Simon, and both were buried on the spot, in a small Iranian village named Kara Kelisa, about 40 miles from Tabriz.

An attractive legend concerning Thaddaeus has come to us from Eusebius. The story tells how Abgar, the king of Edessa, heard about Jesus and asked him to come to Edessa, to escape Jewish persecution and to heal him from poor health. In an Aramaic letter that Eusebius claimed to have seen, Jesus replied that he had to stay and fulfill the prophecies, but after his resurrection he would send one of his disciples to heal the king. Sure enough, a few years later Thaddaeus preached the gospel in Edessa and healed many sick people, including the king. The story ends with Thaddaeus refusing a large gift of gold and silver from the king. A variant of this story has Abgar's messenger choose to paint a picture of Jesus to satisfy the king's longing to see what he looks like. However, the face of Jesus glowed with so much radiance that no picture could be painted, so Jesus pulled a garment over his head. A permanent image of his face formed on the cloth, and many miracles were attributed to the garment after it went back to Abgar; presumably that was the first icon. If there is any truth to this whole story, then Thaddaeus became the first Christian to witness before a Gentile king.

Simon

To distinguish him from Peter, we know this Apostle as either Simon the Canaanite (he was a native of Cana) or Simon the Zealot. Whatever the reasons for his political affiliations, he became an Apostle because he realized that the kingdom of God was worth more than any kingdom of this world. Like the others, he was expecting Jesus to defeat the Romans and restore Israel in his lifetime; he very well may have been the one who asked in Acts 1:6, "Will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?" Instead, Jesus told them to forget that issue and go into the world to make disciples until the end of the age.

The traditions concerning Simon the ex-terrorist have him almost circumnavigate the known world! First he went to Egypt, around 44 A.D. Next he worked his way along the North African coast, from Libya to Morocco, planting churches all the way. Boarding a ship, he went first to Gaul, then to Britain. A questionable English tradition has him traveling with Joseph of Arimathea at this point, and that Joseph left in Britain the cup used in the Last Supper; that inspired the famous quest for the Holy Grail.

When Simon arrived in Britain he was not able to stay long, for it was 60 A.D., and the island was engulfed in the revolt led by the British queen, Boadicea, against the Roman forces. The burning of London forced him to go back to the Continent; then he returned to Israel. On his next journey he wandered north and east, through Syria, Armenia, and Iraq. Finally he joined Thaddaeus in northern Iran, and the two were martyred together there.

Matthias

This character is a mystery. Matthias was chosen as an Apostle immediately before Pentecost, to replace Judas Iscariot. Except for that event, in the first chapter of Acts, Matthias is not mentioned anywhere in the entire Bible. Some theologians have taken that silence to mean that the Apostles were too hasty in choosing him, and that they should have waited until Paul arrived on the scene. Unfortunately, this theory ignores some important details. First, Paul was not converted until nearly a decade had passed; by the time Paul's journeys began, James the Greater was dead, and no attempt was made to replace him or any of the other Apostles. Besides, Paul could never be accepted as an original follower of Jesus, because he never met his Lord in the flesh, as Matthias had done (Acts 1:26). As for Paul's claim in 2 Cor. 11, he belongs in a special category all by himself: not one of the original Twelve, yet too important to be called anything less.

Matthias probably was one of the "seventy" sent out by Jesus in Luke 10:1. Only a few traditions exist concerning his later ministry, but they point to a path almost identical to the one taken by Andrew. First he made a beeline to Armenia, becoming yet another Apostle to witness there. Then he went to Colchis, and followed the Black Sea coastline as far as Sevastopol in the Crimea. Possibly Andrew accompanied him at this point; one wild story has Matthias captured by a tribe of cannibals, until Andrew came and rescued him. Then he returned to Jerusalem, battered from his experiences, to find a hostile reception waiting for him. The date of his final martyrdom varies from 51 to 64 A.D. His relics, like many others, were later found and moved to Europe by the zealous St. Helena, and have been enshrined in Triers, Germany, since 1127.

The Last Herods

If it seems like this chapter is preoccupied with events in the Holy Land, it is because Judaea was Rome's most troublesome province. Meanwhile the rest of the Roman Empire was enjoying two hundred years of unprecedented prosperity and stability, the era we call the Pax Romana. We pay less attention to Asia Minor and other parts of the empire because there were few (if any) wars, revolts, and other events that are newsmakers to us, and here no news is good news. In Judaea on the other hand, tensions peaked during the generation after Jesus, and the Jews got the worst of it.

Herod Agrippa I, born in 10 B.C., was the son of Bernice and Aristobulus, who was slain by his father, Herod the Great. His parents were first cousins, and if that didn't make the family tree complicated enough, he married another cousin, who was the daughter of an aunt, who again was married to an uncle! Josephus called him "Agrippa the Great," and praised him for defending Judaism, while the 12th chapter of Acts portrays him as a persecutor of the early Church. He appears to have been a kindly and likeable, if vain fellow; all of our sources credit him with extraordinary skill in oratory. In religion he followed the letter of the law but not the spirit of it, attentive to "tithe of mint and anise and cumin," while neglecting "the weightier matters of the law, judgment, mercy, and faith."

Agrippa got the Herodian throne because he got along well with a future Roman emperor, Gaius Caligula. One day the two of them were riding together in a chariot, and Agrippa confided that he wished Emperor Tiberius would hurry up and die, so that the government would pass to Caligula. The charioteer, one Eutychus, reported the remark to Tiberius, and Agrippa was thrown in prison. The story goes that he was in the palace courtyard, waiting to be locked up with some other victims of the paranoid emperor, and there happened to be an owl sitting in the tree he was leaning against. A German prisoner noticed this, asked a soldier who that man in purple was, and learned that he was a leader of the Jewish nation. The German then told Agrippa that the owl is a bird of omens, and predicted that its presence here was a sign that Agrippa would soon be released, but beware--because the next time he saw an owl, he would only have five days left to live.

True to the prophecy, Agrippa's humiliation was brief; six months later Tiberius died and Caligula became emperor. As soon as Agrippa had time to shave and put on a respectable garment, Caligula summoned him to the palace, gave him a crown, and had his iron chain replaced with a gold one of equal weight. Caligula also gave him the former tetrarchy of his uncle, Herod Philip. Agrippa hung the golden chain in the Temple as a memorial to what he had suffered, and a lesson in how God can suddenly raise up the fallen.

Most Jews were pleased to see Agrippa come back as a king, but not his uncle, Herod Antipas. While Tiberius was emperor Antipas had intrigued with Sejanus, a Roman officer who coveted the throne, and with the Parthians; he also stored away enough armor to outfit 70,000 men, in case a Roman-Parthian war involved Judaea. In 39 Caligula called Antipas to judgment. He went willingly, because he never got along well with Agrippa, was extremely jealous of him, and wanted the emperor to grant him all the lands once owned by Herod the Great. Agrippa also acted, sending his freedman Fortunatus to Rome with documents proving the accusations against Antipas. Antipas was just having his first interview when Fortunatus arrived and presented the letters to the emperor. The tetrarch could not deny the charges, so he confessed his guilt. Caligula removed him from office, banishing him to Gaul for the rest of his life; the tetrarchy of Antipas was handed over to Agrippa.

Not long after this, Caligula decreed that every man should worship him as a god. Petronius, the prefect of Syria, was ordered to place a gilded statue of the emperor in the Jerusalem Temple. An embassy of Jews, led by the author Philo, tried to talk Caligula out of it, but when the emperor saw them, he said "Begone!" Ten thousand Jews met Petronius in Acre and pleaded with him not to "violate the laws of their forefathers," but if he persisted in carrying out his mission, he would have to kill them first. Petronius was impressed with their loyalty to their faith, and announced he would wait while he sent a letter to Rome explaining the Jewish point of view. Agrippa, who was in Rome then, gave Caligula a magnificent banquet, and drank to his health until the emperor, full of wine, generously offered to grant any request that might contribute to Agrippa's happiness. Instead of taking anything for himself, he said, "This is my petition, that thou wilt no longer think of the dedication of that statue which thou hast ordered to be set up in the Jewish Temple by Petronius." Caligula rescinded the order, but because Petronius had delayed in carrying out the emperor's previous orders, he was ordered to commit suicide. Fortunately for Petronius, he did not get the order until after Caligula was assassinated, so when the order arrived, it no longer mattered.

The new emperor, Claudius, was also a friend of Agrippa. In the year he came to power (41) he enlarged Agrippa's domain by giving him Abilene, Judaea, and Samaria; except for Idumaea, all of Herod the Great's realm was under his control. Now at the height of his career, he began building new walls to fortify Jerusalem, but Marsus Vibius, the new prefect of Syria, ordered the construction stopped merely because it made him suspicious. Then Agrippa invited five petty kings like himself to attend a royal festival in the city of Tiberias. Marsus Vibius also came; Agrippa and the other vassal kings met him in chariots about a mile from the city, to do him honor. Yet Marsus, true to his character, thought that a meeting of monarchs would cause trouble for the Romans, and ordered everyone to leave at once.

It was after this that Herod Agrippa tried to stamp out the Church. He started arresting Christian leaders, beheaded James the brother of John, and would have done the same to Peter. However, the intervention of an angel delivered Peter from prison one night. Presumably Herod was trying to win favor with the Jewish leaders; he always thought he had to prove he was worthy of their support, because of his Idumaean roots.

One day in 44 A.D. Agrippa gave a festival at Caesarea; games were held and prayers were said for the safety and health of Emperor Claudius. The second day began when Agrippa entered the theater wearing "a garment made wholly of silver and of a texture truly wonderful." When the sun shone on this outfit it made him look radiant. The people proclaimed him a god, and he did nothing to stop their flattery. Then he looked up, saw an owl perched on a rope above his head, and remembered the second part of the German prisoner's prediction. He immediately began suffering severe pains, and died five days later. He left behind as heirs three daughters (Bernice, Mariamne, and Drusilla) and a son, 17-year-old Herod Agrippa II.

At this time Herod Agrippa II was in Rome, receiving an imperial education. Claudius decided that Agrippa was too young to receive his father's throne, and that the kingdom was too big to trust to someone whose loyalty had not yet been tested. So they partitioned Israel again: Agrippa got the lands north and east of the Jordan River, the former tetrarchies of Lysanias & Herod Philip, while the rest of the territory went back under direct Roman rule. In 53 Agrippa returned home and took charge of his ministate. Some time after this he appeared in Acts 26, and Paul made a defense of Christianity before him that many regard as one of the best speeches in the New Testament.

Herod Agrippa II, unlike his father, was never popular with his subjects. Presumably this is because his Roman connections were too obvious. Because of this he ultimately failed in what the Romans considered his most important task--keeping the people quiet. Yet in his favor we must argue that the Romans did nothing to make his job easier. The next Roman emperor, Nero, took his cult of personality seriously and insisted upon worship from all of his subjects, Jews included. This was idolatry pure and simple, and thus repugnant to any Jew. Finally there was the character of the last procurator, Gessius Florus. He was a real money-grubber, who treated the Jews with such heavy-handedness that it seems like he wanted a revolt from them. In 66 a major riot broke out between the Jews and Greeks of Caesarea, and Florus demanded a heavy fine from the Temple treasury to cover damages. Refused, he came to Jerusalem, met with a large Jewish delegation that opposed his looting, grew angry, and ended the meeting by ordering the slaying of some 3,600 Jews. In desperation the Jews turned to Agrippa and to the high priests, and asked permission to send ambassadors to argue their case against Florus before Nero. Agrippa responded with a tear-filled speech, where he pleaded that the Jews desist from acts of violence, and greatly moved the people who heard it. Still, it was not enough to stop the ticking bomb. Nor could it be stopped by the threat of reprisal from the Roman legions, or even by the actions of cooler heads within the Sanhedrin--moderate Pharisees and the pro-Roman Sadducees. When Agrippa saw that war was inevitable, he joined the Romans and made war against his abused and aggrieved subjects, though it meant the destruction of his own kingdom.

The Jewish-Roman War

The initial battles went well for the Zealots, who fought with the ferocity of the Maccabees against a larger and better equipped opponent. Their principal leaders, John of Gischala and Simon bar Giorah, were brilliant tacticians. In a surprise attack they quickly overpowered the Jerusalem garrison, gaining control of the holy city. However, using the hit-and-run tactics that had worked for Judas Maccabeus was no longer possible; the Romans had seen to that by building plenty of roads, allowing them to rapidly move reinforcements anywhere. Instead, the leaders of the rebellion captured fortresses in remote areas, like Masada, concentrated their troops there, and prepared for the long sieges that the Romans would inevitably attempt. They divided the whole country into seven military districts, of which the most vulnerable was Galilee. Command of the Galilee district went to a priest of Hasmonean descent, Joseph ben Mattathias, better known to us by the Roman name he later adopted, Flavius Josephus.

When the Romans lost 6,000 men, along with their baggage and siege engines, Nero made his best general, Vespasian, governor of Judaea. Beginning in Galilee, he besieged the fortress of Jotapata, near modern Haifa. Josephus resisted for 47 days, then escaped with forty men to a nearby cave. Each fugitive made a pledge to die by the hand of a comrade rather than let himself be captured by the Romans. Josephus arranged to be one of the last two survivors, then surrendered to the enemy, became a friend and advisor to Vespasian, and was eventually rewarded with Roman citizenship. After the war he wrote his famous history books, The Antiquities of the Jews and The Wars of the Jews. These works are invaluable in understanding the background of the New Testament, but Josephus wrote them to justify the actions of the Romans, and his own questionable behavior. Despite his efforts, Jews still regard him as a traitor today.

The Jews got a reprieve when Nero died in 68 A.D. In the chaos of the following year, three generals rose and fell from the throne. Vespasian stayed out of the civil war at first, until he realized that any general with enough force to back him up could claim the purple for himself. Soon he was making plans with a former rival, Gaius Licinius Mucianus, the governor of Syria, and the two of them secretly enlisted the support of Egypt's governor, Tiberius Julius Alexander. Neither Alexander nor Mucianus was imperial material, the former because he was a renegade Jew, the latter because he had no sons and thus could not form a dynasty. Vespasian on the other hand had two sons, Titus and Domitian, so the governors agreed to back him. Before long the legions in Asia Minor, Armenia, and Egypt went over to their side. Vespasian chose to stay in the east, where he could keep an eye on Judaea; Alexander cut off Egypt's grain supply, which was vital to Rome; Mucianus invaded Italy by way of the Danube. By the end of the year the Empire was theirs. Vespasian went to Rome to claim his prize, leaving his son Titus behind to finish the job of putting down the Jewish rebellion.

In March of 70 A.D., four Roman legions and their auxiliaries--a total of about 80,000 men, arrayed themselves outside the walls of Jerusalem, a city with perhaps 25,000 defenders inside. Unfortunately for the Zealots, they were divided into moderate and extremist factions, and fought for leadership of the rebellion until the siege began. When that happened, though, they resisted fanatically, knowing there was no hope if they surrendered (every day Titus crucified Jewish prisoners, sometimes as many as 500, in sight of the defenders). As fast as the catapults, battering rams, and siege towers could be brought up, the defenders destroyed them, but the Romans repaired them with a minimum of delay. This stalemate went on for fifteen days, until the Romans breached the outer walls. After that the battle continued, fought with even more savagery than before. Old men and women joined in defending against the Romans, dropping stones and boiling oil on those trying to scale the walls. Even the stones the Romans catapulted into the city were flung back at them. All this delayed the attackers, but it did not stop them; they continued to advance, yard by yard. Meanwhile famine gripped the city, killing many more defenders. The fortress of Antonia, which overlooked the Temple, fell in late July. In August--the Hebrew date is the 9th of Av, the same date on which Solomon's Temple had been destroyed six and a half centuries earlier--the second Temple went up in flames. Resistance continued in the upper part of the city for one more month before the siege finally ended.(4)

Like Nebuchadnezzar had done, Titus reduced Jerusalem to rubble and led the survivors into exile and slavery. The struggle had been so tough that Titus memorialized it in a famous arch that shows the Romans parading with the seven-branched menorah, trumpets, tables, and other loot from the Temple. They stamped coins that showed Titus standing in a pose of triumph under the words IUDAEA CAPTA (Judaea is captive). Of the estimated 97,000 prisoners that they took to Rome, 17,000 died on the way; in one ghastly spectacle, done to celebrate the birthday of prince Domitian, 2,500 Jewish youths were killed in a single day, fighting wild animals or each other in gladiatorial games. The Sanhedrin and the Temple priesthood were abolished, and in a move the Jews found especially galling, the half-shekel tax they had once paid to support the Temple now went to the support of pagan cults, like that of the Roman god Jupiter.

John of Gischala and Simon bar Giorah both survived the siege of Jerusalem, and were among the prisoners taken to Rome. After being exhibited in Titus' triumph, Simon suffered the usual fate of defeated kings; he was put to death at Rome's greatest temple to Jupiter, on the Capitoline Hill. The date and manner of John's death is unknown to us.

The Herodian royal family chose to retire in Italy. Agrippa moved to Rome, received the honorary rank of praetor, and lived until the year 100 A.D. One of his sisters, Drusilla, was killed in 79 A.D., by the famous eruption of Mt. Vesuvius that buried Pompeii.

There were a few Zealots holding out in Herod the Great's hideaway palaces that had to be dealt with before Rome could declare the war finished. The Herodium was captured quickly, while Machaerus, where John the Baptist had been killed, did not fall until its leader was captured in 71. Masada was the hardest nut to crack, perched atop a mesa a quarter mile above the shore of the Dead Sea. For three years nearly 1,000 men, women, and children held it against 15,000 Romans in eight surrounding camps. It took the construction of a huge earthen ramp up the slope of the mountain before they could breach the walls of Masada. When that happened in 73, the Romans found only two women and five children left alive inside the fortress; the rest had committed suicide, choosing death before dishonor. To modern Israelis Masada is an example of heroism against hopeless odds, remembered by them in much the same way that Texans remember the Alamo. Today's Israeli soldiers take their oath of allegiance there, swearing that "Masada will not fall again."

Parthia: The Anti-Hellenistic Period

Many historians define Parthian history by its cultural trends, dividing it into "Phil-Hellenistic" (171 B.C.-12 A.D.) and "Anti-Hellenistic" (12-162 A.D.) periods. The former was a time when Greek civilization dominated the scene; the latter saw Greek art, language, customs, etc. disappear completely, submerged in a Persian renaissance. The ruling dynasty actively encouraged this trend, to increase patriotism. However, the loyalty generated went to the kingdom, not the crown. As a result, the years covered in this section saw the Arsacid dynasty grow weak, and it only got things done when it agreed with the nobility.

At the beginning of this period the Roman Emperor Augustus and his Parthian counterpart, Phraates IV, were about as friendly as two rivals can get. Together they reached an agreement concerning Palmyra, an oasis in the east Syrian desert that had become vital to the commerce of both powers; Rome nominated a Hellenized vassal to rule it, and Phraates accepted, though Parthian public opinion didn't. Then Augustus sent a slave girl named Musa to the harem of Phraates. The wily concubine gave birth to a son, and persuaded Phraates that it would be a good idea to send the king's older sons to Rome for safekeeping; he did, thinking it was good for international relations. After the other princes were gone, she poisoned the king, had her son crowned, and married him. Thus in a few years Musa rose from royal gift to queen.

Their joint reign lasted from 2 B.C. to 6 A.D. (five years, because there is no "year zero," remember), and then Musa and her husband/son, Phraates V, were driven from the throne. Now the other princes came home from abroad. Two of them, Orodes III & Vonones, were the next kings of the realm. Both of them were short-lived, and noted for their weakness and pro-Roman sympathies; Vonones, to the disgust of his subjects, was not even interested in horses!

In 12 A.D. the barons ousted Vonones and replaced him with a ruler more to their liking. That was Artabanus III (12-38), the son of the viceroy of Hyrcania, who had royal blood on his mother's side. As it turned out, Artabanus was not an easy instrument for others to manipulate. Violently anti-Roman in character, he eagerly wanted to drive the Romans out of Asia. His attempt to place a son on the throne of Armenia failed, though, and after that he devoted the rest of his reign to internal reforms. He did this by humbling the nobles, taking away many of their hereditary privileges, and removing unreliable barons. Several satellite states in the west--Charax, Elymais, Persis, and Atropatene--received members of the Parthian royal family as rulers. The great city of Seleucia on the Tigris, however, revolted, and it took seven years to regain control there; in the east the Suren king Gondophares declared himself independent (19) and took the title "King of Kings."

The next important king was a real Iranian nationalist, Vologaeses I (51-78). Under him a genealogy was invented that purported to show the Achaemenid ancestry of the Arsacid house. The reverse side of his coins showed a Zoroastrian priest at a fire-altar, and bore letters in Pahlavi (Parthian), instead of Greek script. According to tradition the Zoroastrian holy book, the Zend Avesta, was compiled during his reign. To cut Seleucia down to size, he built a rival city named Vologasia, which soon became a commercial center in his own right.

It was not only Greek culture that withered away at this time; the ancient Mesopotamian civilization, which occupied center stage in the first four chapters of this work, had been dying slowly ever since Cyrus the Great captured Babylon. Part of this was because civilization had spread far beyond the Fertile Crescent; Iraq was no longer the busiest place in the civilized world. The Persian Royal Road, for example, passed north of Babylonia instead of through it. The Persian kings did what they could to maintain the cities, but events elsewhere, like the struggle with Greece, occupied most of their attention. Gradually, buildings crumbled, canals silted up and farms turned into deserts.

As the economy deteriorated and the local hydrographics changed, people moved away. Then other people moved in, but they were not Semites; they spoke Persian, Aramaic or Greek as their first language. To them, the cuneiform inscriptions on clay tablets were meaningless, and a nation which forgets its language loses both its past and its identity. During the Greek era cuneiform disappeared from everyday use, until only scholars and temple scribes could understand it. The last existing cuneiform text, an astronomical almanac, was written in 74 or 75 A.D. When the Roman emperor Trajan visited Babylon in 115 A.D., he did not "take the hand of Marduk," as Babylonian kings had done, but sacrificed to the spirit of Alexander the Great. In 199, Septimius Severus found the city completely deserted.

Vologaeses wanted one of his brothers, Tiridates, to become king of Armenia, but Rome opposed this move with force. The result was an inconclusive ten-year war, which ended in 66 with a compromise: Armenia could have a Parthian monarch if he submited to Roman authority. Tiridates went to Rome with his family and 3,000 nobles, and there he received his new crown from Nero. The Parthian dynasty would survive in Armenia long after it disappeared from Parthia itself, until 428.

While all these events were happening, the Parthian state began disintegrating into several smaller countries. The chronic weakness of the central government brought this on. In fact, from the Roman point of view Parthia was not one kingdom but a confederation of eighteen. In 58 Hyrcania became independent. On the eastern frontier a powerful central Asian state, Kushan, arose between Parthia and China; now somebody else could play the same middleman game that the Parthians had played with the Romans and the Chinese. In the west Rome resumed the process of absorbing vassal states that had begun a century earlier; Vespasian annexed Emesa and Commagene.

In 78 Pacorus II came to the throne, only to be thrown out a year later by Artabanus IV, who likewise lasted a year before Pacorus II returned to depose him. Pacorus now kept the throne, but not much more. Barons refused to obey the crown, and they had more control over the army and finances than the king did. Plots hatched, and Rome sometimes got involved in them to advance Roman interests. In 109 Pacorus was replaced by Osrhoes, his brother or brother-in-law.

The borders Augustus gave the Roman Empire changed little until Trajan came to the throne. An impartial administrator and a talented general, he conquered Dacia (Romania) in 106. Then he moved east, turning the Nabataean kingdom into the Roman province of Arabia (also 106). In 113 he got an excuse to attack the Parthians when they replaced the king of Armenia without Rome's consent. Trajan began his campaign in the following year, taking Edessa and Armenia with little resistance. The Armenian king put his crown at Trajan's feet, but was deposed anyway. In 115 the emperor advanced into Iraq. Adiabene, the nearest Parthian client state, became the new province of Assyria; Ctesiphon fell to the legions and Trajan carried off a daughter of Osrhoes and the Parthian throne; the Romans continued down the Tigris until they captured Charax. Before the year was up Trajan stood on the shore of the Persian Gulf, thinking aloud of Alexander. But the Iranian response was not late in coming. The loss of Ctesiphon persuaded the formerly divided princes to unite against the invader. The new provinces revolted, and the Parthians invaded Armenia and Assyria. Trajan responded by returning to Ctesiphon and crowning a vassal king there, but this attempt to disunite the Parthian chiefs failed. After he failed to take Hatra, a fortress in the northern Iraqi desert, Trajan declared the campaign over and died on his way home.

Again Parthia had thrown back a superior enemy. The next emperor, Hadrian, decided that Augustus had the right idea and promptly pulled back to the Euphrates. He returned the golden throne and the royal princess, Armenia returned to its previous role as a client kingdom, and only Edessa remained as a souvenir from Rome's easternmost expedition. When Osrhoes struggled with his successor, Vologaeses III, Hadrian stayed out of it. He even invited Osrhoes to visit Rome. The peace between them was a genuine one, lasting for more than 40 years.