| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 9: TRANSITION AND TURMOIL, PART II

1300 to 1485

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

| The Hanseatic League and the Merchants of Venice | |

| Scotland vs. England | |

| The Babylonian Captivity of the Papacy | |

| The Hundred Years War: From Sluys to Crécy | |

| The Black Death | |

| The Hundred Years War: Reverses and Revolts | |

| The Rise of the Hapsburgs | |

| The Birth of Switzerland | |

| The Union of Kalmar | |

| The Great Schism | |

| Wycliffe and the Hussites |

Part II

The Failure of Greenland

Life grew increasingly difficult on Iceland and Greenland after the Vikings stopped roaming the north Atlantic. Neither colony was fully self-sufficient, and whatever they couldn't grow or make had to be imported at great expense, from merchants willing to brave the dangerous waters to visit them. The colonists paid for these goods with surplus livestock and the skins and ivory of whatever they caught from hunting.

Modern Icelanders regard the eleventh and early twelfth centuries as a golden age, because that is when they wrote down most of the Norse sagas. However, this also was a time when the central government could not enforce its authority. As a result, the local lords raised private armies and threw them at each other, in a series of dynastic wars, shifting alliances, murder and betrayal (1230-64, this is sometimes called the "Age of Stone Throwing"). Peace did not come until the chiefs of both islands submitted to the king of Norway (1262-64).

The main problem for the colonies was a deteriorating climate. Part of this trouble was man-made; on both islands the settlers cut down the trees that grew near the fjords, for firewood or building material, and grazing cattle and sheep prevented the plants from growing back. Hills eroded, sand drifted over the best pastures, and eventually the wood supply ran out, except for the pieces that drifted ashore. Bog iron was available, but without wood for charcoal, it could not be forged; one thirteenth-century knife had been sharpened and resharpened, until the blade was nothing more than a stub, because the owner could not make a replacement. Archaeological digs at Greenland revealed that the typical settlement had buildings made mostly of sod and stones. The cattle were about the size of Great Danes, kept underground in unventilated stalls, and when spring arrived they were so weak that they had to be carried out to the pastures. As the climate got worse, some farms switched from cattle and pigs to sheep and goats, which are hardier in such conditions. Bones found in garbage pits also show that after 1300 the Norse depended more on seafood, especially seals, whereas in the past they got as much as 80 percent of what they ate from farming and herding.

What the settlers could not control was the arrival of the "Little Ice Age." After 1250 the weather grew colder, pack ice made sailing even riskier and the land became less forgiving for those who misused it. At the same time came a drop in trade. The Norwegian economy declined when forced to compete with the Hanseatic League, and when the Black Death struck Norway, cargo ships stopped traveling the northern sea lanes regularly. A trickle of commerce continued with Iceland, but sailing to Greenland ended completely; without wood and iron from mainland Europe, the Greenland colonies were doomed. The last official trade voyage from Norway to Greenland took place in 1367; no bishop went to Greenland after 1378, though the Church kept appointing bishops to keep the post filled. As a result, Greenland's settlements died slowly; to most Europeans, the huge ice-covered island on the edge of the world just seemed to disappear.

In addition to the harsh weather and lack of trade, the Greenlanders faced a human enemy: the Inuit (Eskimos). The Inuit had crossed to northern Greenland from Canada around the same time that Eric the Red colonized the south. As the Inuit moved south, they met the Vikings; some friendly contacts took place, but relations soured by the mid-fourteenth century. King Magnus Eriksson of Norway made a call for a military expedition against the Greenland heathens in 1355, which nobody heeded, while Inuit folktales talk about skirmishes with the Norsemen. Apparently the Inuit had the advantage in these conflicts, for they are geniuses at survival in the Arctic. Their Norse opponents may have been larger men, but they were careful not to learn anything from the Inuit, so size didn't help in the long run. The archaeologists who examined the graves of the Greenland settlements found the dead buried in up-to-date European fashions, instead of Inuit-style parkas; that, along with their refusal to use Inuit inventions like harpoons, dog sleds, and kayaks, is a testimony to the Greenlanders' inflexibility and failure to adjust to the changing climate.

The precarious Western Settlement failed at some point in the early fourteenth century. When a Norwegian priest, Ivar Bardarson, arrived from the Eastern settlement in 1350, he found "never a man, either Christian or heathen, merely some wild cattle and sheep." Bardarson's crew loaded the animals they caught on their ship, and the priest reported that the "Skraelings" now held the settlement. What caused the colony's disappearance is not certain; the most popular theories are that the colonists froze and/or starved to death after eating all their livestock, or that the Inuit wiped out the colony. However, no bodies were found in the ruins, nor were there any crucifixes, chalices, or chandeliers lying around--things that medieval Christians would find valuable. This suggests that they didn't die suddenly. In addition, no evidence been found that the Norse "went native" and joined the Inuit. Now it looks like the last survivors buried those who died before them, and then simply packed their bags and left.

The last ship to visit the Eastern Settlement was an Icelandic one that had been blown there by a storm; its crew stayed for four years (1406-10), possibly because of heavy ice on the seas. While they were there, a wedding was performed for an Icelander and a Greenland girl, Thorstein Olafsson and Sigrid Björnsdottir. The celebration of that wedding may have been the last party in the Eastern Settlement. When the ship returned to Iceland, the young couple went with it; as with other places that offer no opportunity, the young people went away to seek jobs/fortunes elsewhere, leaving their older relatives behind. After that nobody came, and nothing was heard from the settlement. The end of the Eastern Settlement, like that of the Western Settlement, is unknown to us. In 1540 an Icelander named Jon Greenlander sailed there; he found abandoned booths and houses, and "a dead man lying face down on the ground . . . clothed in frieze cloth and sealskin." Near the body lay a rusty iron sheath knife, which tells us this man was a European, not an Inuit (the last Norseman in Greenland?). Subsequent expeditions over the next two hundred years failed to find any survivors. When the present-day rulers of Greenland, the Danes, arrived in 1721, they had to build their colonies from scratch.

Iceland survived, but its fortunes went into such a tailspin that it took until the 19th century to recover. Part of the hardship, as with Greenland, came from the Little Ice Age. For example, a document written in the early 1700s describes the Bredamörk farm as "derelict . . . a little woodland, now surrounded by glacier." The document goes on to say that as late as 1698, "there was some grass visible . . . but the glacier has since covered all except the hillock on which the farmhouse . . . stood, and that is surrounded by ice so that it is of no use even for the sheep."

Iceland's worst years began when rule over it, along with Norway, passed to Denmark in 1380. As Denmark sought to expand its shipping and commerce, it did not want the lucrative Icelandic trade to flow to England or Germany, so the Danes gradually reduced the trading activities of these nations in Iceland; by the middle of the 16th century they had virtually ceased. At the same time, the royal authority greatly increased its interference in other spheres of Icelandic life. In 1550 Lutheranism was forced on the nation, a feat accomplished by the execution without trial of the last Roman Catholic bishop, Jón Arason, and two of his sons. Half a century later, in 1602, a trade monopoly was instituted. From that time until 1787, commerce with Iceland was permitted only to licensed merchants, who bought their charters from the Danish Crown for exorbitant fees and recouped their investment from their captive customers. Consequently, prices for necessities, such as grain, lumber, and metal goods, soared, while Icelandic products--mostly fish and wool--were undervalued because their prices were established by the same merchants. In the long run, this oppressive economic system reduced the island to utter destitution.

The Hundred Years War Resolved

Henry V, who became king of England in 1413, renewed the war with France two years later. His aim was not to recover the lands lost by his predecessors, but to take the French crown for himself. The time looked right for him to do it, too. Over the past few years, the French had stirred up trouble for the English in Scotland and Wales (e.g., the rebellion of Owen Glendower); the current French king, Charles VI, was a certified lunatic; French knights were still having trouble telling the difference between tournaments and tactics.

Crossing the Channel with a new army, Henry met the French at Agincourt, not far from the site of his great-grandfather's triumph at Crécy; Henry used a similar strategy and the trusty longbow to annihilate the French (1415). The French knights wore full plate armor to stop the English arrows, but they had to march through a narrow, muddy valley that slowed them down and reduced their numerical advantage to a level the English could handle. Furthermore, the French armor was so heavy that once the wearer was unhorsed, he could not get up again; the English force included cutthroats who finished off the now-helpless knights with a dagger-thrust into the visor of each helmet.(14) Henry also found a formidable ally in the count of Burgundy, who was both a relative and enemy of Charles VI. Together England and Burgundy conquered Normandy in 1419; in 1420 Charles signed the treaty of Troyes, which surrendered all of northern France, including Paris, to the allies. He guaranteed the treaty with a really odd performance: he disowned his own son, married his daughter to Henry and made him his heir.(15)

It now looked like the English would take over all of France. Much of France was devastated and depopulated; for the first time in a hundred years wolves roamed the streets of Paris. But Henry died in 1422, and Charles followed him a few months later. Henry's infant son, Henry VI, was confidently crowned king of both countries, while an uncle, the Duke of Bedford, laid siege to Orléans, an unsubdued stronghold on the Loire River.

It was here that one of history's most remarkable figures intervened to save the day for France. A seventeen-year-old peasant girl from Lorraine, Jeanne d'Arc (Joan of Arc in English), became convinced that saints were calling her to lead the army that would save the country. Making her way through enemy lines, she caught up with the Charles the Dauphin (the disinherited son of Charles VI) at Chinon and told him her story. Charles was cautious, and had some theologians examine her for signs of witchcraft; they pronounced her a virgin, meaning that the "voices" that compelled her had to be pure spirits. That convinced Charles to let her go ahead--after all, everything else had failed to this point--and sent her to Orléans with a few troops.

What happened next was both a triumph and a tragedy. Wearing armor and riding a white horse, Joan so inspired the beleaguered soldiers and people of Orléans that they rose up and defeated the English attacking their city. Once the siege was raised, Joan led the army northeast. Four months after first meeting the Dauphin, she captured Rheims, and watched as the Dauphin was crowned King Charles VII in Rheims Cathedral, the traditional place for the coronation of all French kings (July 1429). But ten months later she was captured by the Burgundians while making a sortie on Compiègne, and sold to the English. Under English pressure, a Church court found her guilty of heresy and witchcraft, while the French king she had won the crown for made no effort to save her. On May 30, 1431, Joan of Arc was burned at the stake in the marketplace of Rouen.

In 1456 the pope declared the verdict against Joan to be invalid, having been obtained by fraud and deceit; in 1920 she was formally canonized. But French patriots did not wait for the Church to clear her name. Emboldened by her example, the French recaptured Paris in 1436.(16)

So far King Henry VI had not played a part in the war, because he was not old enough yet. After he grew up, he was interested in matters of religion and education, but not in administration or military matters, meaning he had the opposite temperament of his father. When the time came for him to choose a bride, he looked at portraits of eligible noblewomen and picked Margaret of Anjou, the niece of Charles VII, because he heard she was a stunning beauty and such a marriage could be used to bring peace. Charles said he would allow the marriage under these conditions:

- France would not have to pay the dowry of 20,000 livres that England expected.

- England would pay for the wedding.

- Henry would give up the English claim to Maine and Anjou, the ancestral lands of the Plantagenet dynasty.

The fate of Bordeaux was sealed by the battle of Castillon, where French artillery fire tricked the English into attacking at the wrong time. This was the first time firearms won a field battle. The war had seen guns in use as far back as the battle of Crécy, but the first guns took too long to reload, making them good for only one volley when used tactically. They did better in sieges, because in that case the target did not move, but still it took a century of development to make cannon effective enough to replace older forms of artillery (i.e., catapults). The French had cannon at Agincourt, which were credited with killing a single English archer, and in 1431 the duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, fired 412 cannonballs into the town of Lagny, but the only casualty of the bombardment was a chicken. Joan of Arc had a talent for aiming cannon at targets that did the most damage when hit, and after Joan's campaign, French armies built more firearms and made them more efficient. By the end of the 1440s, an attacking army with cannon could reduce in a matter of weeks those castles and walled towns that used to hold out for months or even years. At Formigny, the 1450 battle that decided the fate of Normandy, the French had two culverins, breach-loading cannon on wheeled carriages, and they proved themselves equal to the English longbowmen. When the French put cannon in front of the Aquitanian fort of Bourg, it surrendered immediately (1451). You can mark 1453 as the year when guns became the most important weapon of warfare, but Castillon isn't the only reason. In the same year at Constantinople, the Turks used cannon in their more familiar role, to batter down the famous wall of two hundred towers that had withstood virtually every attack during the previous 1,100 years.

The End of the Byzantine Empire

With the recapture of Constantinople in 1261, the final phase of Byzantine history began, under its last (and longest-lived) dynasty, that of the Paleologi. The two centuries which followed produced the Empire's most brilliant art and literature, but these came from a crippled nation that shrank to the size of a city-state, while outsiders still regarded Constantinople as one of the world's greatest cities. Genoa controlled the economy completely, and the state squandered its last strength in civil wars and intrigues.(17) In 1347 the Black Death wiped out two-thirds of Constantinople's population. By 1400 the capital probably had 100,000 residents, about one sixth of what it had two centuries earlier. Most of the streets had become grassy paths, with garden plots in abandoned neighborhoods to feed the last residents. Money grew short, and the splendor of earlier times vanished. One contemporary observer wrote that "The jewels in the crowns were glass, the robes not real cloth-of-gold but tinsel, the dishes copper, while all that appeared to be rich brocade was only painted leather."

In the fourteenth century two new powers arose to take what the Empire had left. One was the Serbs, who under Stephen Dushan achieved the first empire run by the southern Slavs; this included twentieth-century Yugoslavia, Albania, Macedonia and about two-thirds of Greece. Dushan's decade of success did not produce a lasting state, though, because he failed to take Constantinople and give his realm a worthy capital. As with Guiscard, he died before he could attempt the siege (1355) and his empire split into half a dozen warring principalities.

The other newcomer finally finished off the Empire--the Ottoman Turks. When Genghis Khan's armies stormed out of Mongolia, many Turks fled west to escape the ravaging Mongol hordes. About eight Turkish tribes settled in western Turkey by 1300, and one rose to dominate the others, by virtue of its fighting skills and a good geographical location. This clan was originally led by a chief named Osman, so his name became that of the state he and his heirs founded--the Ottoman Empire.

Between 1326 and 1337 the Ottomans took the last Byzantine cities in Turkey: Brusa, Nicaea and Nicomedia. In 1354 they crossed the Dardanelles and seized the Gallipoli peninsula, giving them a foothold in Europe. From there they fanned out across the southern Balkans; Adrianople (modern Edirne) became their new capital in 1361; in 1389 they defeated the Serbs at the battle of Kosovo, and Serbia passed under Turkish rule. The Byzantines were isolated and surrounded in Constantinople, Salonika (ancient Thessalonica) and part of the Peloponnesus (Morea). Constantinople itself came under siege in 1394; the multinational force sent to rescue it was crushed at the battle of Nicopolis, in 1396. The Ottomans did not have cannon to blast through Constntinople's famous walls, or enough soldiers to take the city in an assault, so they tried starving it out, and thus surrounded the city for eight years. The Byzantine capital only survived because Timur (also called Tamerlane), the nastiest of Genghis Khan's successors, invaded Turkey in 1402 and carried off the Ottoman sultan in an oversized bird cage.(18)

The Turks spent the first decades of the fifteenth century recovering from this defeat, so they didn't attack Constantinople again until 1422. This time the siege was abandoned when the troops had to leave to put down a revolt in Asia; Constantinople had survived for the last time. Then Emperor John VIII tried to enlist western aid by reuniting the Catholic and Orthodox Churches, which had been formally divided since 1054. He went to Italy with some bishops and theologians, and in 1439 they signed a document which accepted the authority of the pope in return for Western support. But this reunion was insincere, never accepted by the people of Constantinople, and denounced by most Orthodox clergymen. Anyway, the days when the Papacy could direct the armies of the West were over; Constantinople would fight and fall in the name of the Orthodox Church. An army of Hungarians and Crusaders tried to rescue Constantinople from the inevitable result of the next Ottoman attack, only to be totally defeated at the battle of Varna (1444). Meanwhile the Turks found time to annex Salonika (1430) and Morea (1446).

Constantinople was now in the heart of the Ottoman Empire, and though it had been in decline for centuries, it was still the largest city in Europe, so the Turks could not ignore it forever. Accordingly, when Mohammed II (1451-81) became the sultan, he spent two years preparing for a new siege, one that would be far more thorough than any attempted before. The army he gathered included 20,000 mercenaries (both Moslem and Christian) and 80,000 regulars, the finest of which were 12,000 ex-Christian slaves, the famous Janissaries. Because Constantinople had often survived in the past by virtue of its navy, Mohammed brought in 250 ships. The Turks never had much use for gunpowder weapons previously, but this time Mohammed saw they would need them to blast through Constantinople's walls, so he hired a Hungarian engineer named Urban to construct 100 heavy cannon. Urban's largest creation was a monster with a barrel twenty-six feet long, that could reportedly hurl a 1,500-pound stone ball more than half a mile; it took a cart pulled by 60 oxen and an escort of 200 men to bring it from its foundry at Edirne. Against this, Byzantium could only muster some 7,000 troops (2,000 of them foreign mercenaries) and 26 ships.

Mohammed II and the Turkish army. The super-cannon is visible on the right.

The 23rd and ultimately successful siege of Constantinople began on April 6, 1453. For weeks a tense competition took place; by night the defenders would come out and work overtime to repair the damage inflicted on the walls; by day the Turkish cannon would blast away as much of the repair work as possible. The main harbor of the city, known as the Golden Horn, kept Turkish ships out with a large chain stretched across the entrance. To get past this defense Mohammed had seventy ships dragged overland on greased logs, entering the harbor by going around the chain. Now they could attack Constantinople from both land and sea.

After that the war of attrition continued for the rest of April and most of May. The sultan was winning because he had the numbers and the defenders were almost out of food, but he had problems of his own. The cost of keeping his huge army active was phenomenal; every direct assault on the walls had been thrown back; casualties were mounting at an alarming rate; morale was dropping among his advisors, who started talking about a negotiated peace. Accordingly, the sultan ordered a day of rest, to prepare for a colossal assault on the following day (May 29, 1453).

Even at this late date, Constantinople might have survived one more siege--if it wasn't for what may be the most important oversight in history. You won't see it in "Fetih 1453," the Turkish-language movie that was made about the siege in 2012, because what happened wasn't an exciting moment. The defenders had used a small gate, the Kerkoporta Gate, to go out and repair nearby parts of the wall, and after their last trip outside, the gate was left unlocked. Nobody opened it to let the Turks in; whoever had the keys simply forgot to lock the door. When a Turk tried that door, the city's last line of defense was penetrated. Constantine XI, the final emperor, reportedly said, "The city is fallen and I am still alive," tore off his imperial ornaments so he would look like an ordinary soldier, and led his remaining soldiers in a charge against the incoming Turks. He was killed, of course, and his body was never positively identified among the dead. Half the city's inhabitants were massacred, while the rest were enslaved.

The fall of Constantinople was long overdue, but when it happened it caused shock waves nonetheless. Like the fall of Rome in the fifth century, something that was never supposed to happen had come to pass. Western Christians were uneasily aware that they had contributed to Constantinople's fall, first by crippling it with the Fourth Crusade, and then by not giving it sufficient aid when new enemies appeared at its gates. Now they realized that they had not only lost the most important city of medieval Europe, but also the main gateway to the Orient. When the Ottoman sultan moved in, he guaranteed that Constantinople would rise again, but this time it would be Istanbul, the capital of the most formidable, best-run state in the Islamic world. Pope Pius II belately tried to rescue Constantinople enlisting Vlad Dracula (see below) in an anti-Turkish alliance; talk about making a pact with the devil! When that didn't work out, he called for a crusade in 1463. But the desire to wage holy wars overseas was gone, and no Christian head of state was interested in taking up the cause of the cross (they had the battles of Nicopolis and Varna to remind them of what could happen if they messed with the Turks!), so Pius decided to lead the crusade himself. He traveled to the Italian port of Ancona to wait for the army of knights he expected, but few showed up, and because he was already ill, the pope soon died and the whole enterprise was abandoned. Today we use the fall of Constantinople to mark both the end of the Eastern Roman Empire and the end of the Middle Ages. A generation ago high school students remembered it with this rhyme:

"Who gave Constantinople the works?

That's nobody's business but the Turks!"

Technically everything south of the Danube River had been under Turkish domination since the 1390s, but after Constantinople there were two centers of resistance, each centered around an individual: Skanderbeg in Albania and Vlad III, the original Dracula, in Wallachia (southern Romania). Skanderbeg's real name was George Kastrioti (1403?-1468), but nowadays we usually call him by the Albanian version of his Turkish nickname (Iskander Bey, meaning Alexander the Great). The son of an Albanian prince, he was sent to the Ottoman Turks as a hostage, where like the sultan's elite force of ex-Christians, the Janissaries, he was educated as a Moslem and enlisted in the army. His talent made him popular with the sultan, and he was given a command, but when he heard in 1443 that his native land was in revolt, he deserted, returned to Albania, renounced the Islam that had been forced on him, and became the leader of the Albanian chiefs. He held back the Turks so well that in 1463, with the help of the pope and the governments of Venice, Naples, and Hungary, he forced the Turks to accept a 10-year armistice. However, he broke the truce shortly after that, which meant that for the rest of his career he would have to fight without his former allies. Upon his death, Albania collapsed and was reconquered; the Albanians, who until now had been Orthodox Christians, converted to Islam without too much pressure over the course of the next century, and thus managed to secure for themselves a place as the sultan's favorite European subjects.

Today Albanians remember Skanderbeg as their greatest hero. Romanians feel much the same way about Dracula, but to others his very name became a symbol of horror. His father, Vlad II, had served as governor of Transylvania under King Sigismund of Hungary, and belonged to a secret fraternal order of anti-Turkish knights called the Order of the Dragon, so he was nicknamed Vlad Dracul, meaning "Dragon" or "Devil." However, he wasn't content with those titles, so in 1436 or 1437 Vlad killed Alexandru, a distant relative who happened to be prince of Wallachia, and took his crown for himself. The drawback to this seemingly successful coup was that it put Vlad in the camp of Hungary's enemy; now he had to pay tribute to the Ottoman Empire and send two of his sons, Vlad III and Radu, as hostages to the Turks. Vlad Dracul used his new position to sit out the 1444 war between the Hungarians and the Turks, but in 1447 he was murdered, most likely in a Hungarian plot. The Turks now let Vlad III, now known as Dracula ("son of the dragon"), return with an army to rule as the new prince of Wallachia, while Radu, who was younger and more loyal, stayed with the sultan in Adrianople.

Vlad ruled Wallachia three times, for two months in 1448, from 1456 to 1462, and for a few months in 1475-76. The first time he was ousted by a Hungarian rival, but when he regained his throne in 1456 he stopped acting pro-Turkish. During his second and longest reign, he bravely resisted both the Hungarians and Turks, but was mainly known for his extreme cruelty. It is estimated that between 40,000 and 100,000 were executed on his command; he liked impalement best, because the victims could take hours, even days, to die on the stake, so today he is sometimes called Vlad Tepes, or Vlad the Impaler.

In 1462, Sultan Mohammed II led a huge army of 90,000 into Wallachia; against this, Vlad had an estimated 30,000 or 40,000 troops. This wasn't enough to either defeat the Turks in battle or resist a siege, so Vlad tried a desperate raid. One night he sneaked into the sultan's camp with seven thousand picked troops who spoke Turkish, and began attacking Turks left, right and center. They slew 15,000, but their main target--the sultan--was only wounded. Eventually Vlad had to get out and he pulled his force back to Tirgoviste, his capital, with the Turks still in pursuit. Because he couldn't outfight the Turks, Dracula used psychological warfare next--he scared the Turks away with his greatest atrocity, surrounding Tirgoviste with a "forest of the impaled." Chalkondyles, a Greek historian, described the terrifying scene that the invaders beheld:

"He [the Sultan] marched on for about five kilometers when he saw his men impaled; the Sultan's army came across a field with stakes, about three kilometers long and one kilometer wide. And there were large stakes on which they could see the impaled bodies of men, women, and children, about twenty thousand of them, as they said; quite a spectacle for the Turks and the Sultan himself! The Sultan, in wonder, kept saying that he could not conquer the country of a man who could do such terrible and unnatural things, and put his power and his subjects to such use. He also used to say that this man who did such things would be worthy of more. And the other Turks, seeing so many people impaled, were scared out of their wits. There were babies clinging to their mothers on the stakes, and birds had made nests in their breasts."

The Turks didn't want any part of a country like this, and fled as fast as their feet would let them, but the sultan sent Dracula's brother Radu in his place with a new army. Vlad was forced to flee to Transylvania, and when he tried to get help from Matthias Corvinus, the new Hungarian leader, he was put under house arrest. He was allowed to leave and make another bid for the Wallachian throne after Radu died in 1475, but in the following year he was killed, though it isn't clear whether he fell in battle against the Turks or was assassinated. More than four centuries later, when Bram Stoker needed a name and role model for his legendary vampire, he would choose Dracula, though he got the facts about him and Transylvania somewhat garbled.(19)

Nice Knowing You, Burgundy

Burgundy had been around for most of the Middle Ages, but as a second-rate duchy, usually under German or French domination. In the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the Burgundians briefly became a major European power in their own right.

The old French royal family, the Capetians, held onto Burgundy for a generation after they lost control of the crown. The duchy passed to the House of Valois in 1363, when Philip the Bold, a son of the unlucky French king John II, was entrusted with it. At once Burgundian fortunes began to look upward. Philip bought a large piece of land across the German frontier, the future French province of Franche-Comté, and married the heiress of Flanders (both events took place in 1384). Like the other French dukes, Philip paid little attention to the fact that he was supposed to be a vassal of the king, so these moves made Burgundy a positive danger to the rest of France.

Some followers of the Dauphin managed to assassinate John, the next duke, in 1419, but John's successor, Philip the Good (1419-67), made even more spectacular gains. This Philip played a pivotal role in the Hundred Years War, as we saw previously, first supporting England, and later backing France. In 1430 Philip obtained Brabant and Limburg, two blocks of territory that had belonged to the Luxemburgs; in 1433 he took the Wittelsbach holdings in Holland; in 1435 he became lord over the French province of Picardy; in 1451 he got Luxembourg. Now the entire area we call the Low Countries was Burgundian, and because of the strong economy in this region, the dukes of Burgundy joined the wealthiest princes of Europe. The Burgundian court saw one of the last flowerings of medieval pageantry, and it was during this period that the realistic school of Flemish painting developed, starting with Jan Van Eyck (1386-1440) and Rogier Van Der Weyden (1400-64). All the dukes needed to do was gain control over Lorraine, the territory between Burgundy proper and the Low Countries, and they would have a solid block of land stretching from the Alps to the North Sea.

There was little the French king could do about Burgundian expansion, for of the seven tracts of land controlled by the duke--Burgundy, Artois, Picardy, Flanders, Franche-Comté, Wallonia and the Netherlands--only the first four were within the borders of France (the rest were part of the Holy Roman Empire). The next duke, Philip's son Charles (1467-77), was the most aggressive Burgundian of all; history books call him either Charles the Bold or Charles the Rash, depending on the author's point of view. Charles allied with England, Castile and Aragon to encircle his bitter enemy, King Louis XI of France. Meanwhile, the Hapsburgs offered to crown Charles as a real king, if he would promise to (1.) give his daughter Maria to the Holy Roman Emperor's son, and (2.) invade Switzerland. Charles agreed to these proposals, and moved to conquer Lorraine (1475). Then he went after the Swiss, but here he met his match; the Swiss pikemen defeated him in the battles of Grandson and Murten. In 1477 Louis sent a Swiss mercenary army into Lorraine, and this force killed Charles in a third battle, at Nancy.

Next Louis invaded the Netherlands, but the late duke's daughter refused to give up. Maria married Maximilian I, and the Hapsburg heir was strong enough to beat back Louis's armies and save the Netherlands for his wife. However, Maximilian also faced unrest; the Dutch resented losing much of their freedom when Maximilian took over, though there was a war going on. This became an outright revolt in Flanders when Maria died in 1482. Maximilian couldn't deal with this problem and fight the French at the same time, so he signed the Treaty of Arras, which was basically on France's terms: Louis got all of the former Burgundian territories except Wallonia and the Netherlands. Burgundy had been eliminated, and France now had the strong central authority she had previously lacked.

Besides solving the Burgundian problem, Louis XI (1461-83) succeeded in nearly every diplomatic venture he tried. Because of his complicated stratagems, many call him "the Spider King" and the first Machiavellian, but his intellectual abilities were strictly limited; he tended to act first and think later, and his qualities, good and bad, were really those of a peasant. His best point was tenacity, and the only modern quality of his otherwise medieval mind was the recognition that whoever has money has power, too. He taxed his subjects hard and spent the money fast. To keep England's Edward IV from invading France, in a rematch of the Hundred Years War, he gave aid to the Lancastrians, during the Wars of the Roses (see below). Then after that danger was past, he broke up the Anglo-Burgundian alliance by buying off the English, giving them a down payment of 100,000 ducats, and 10,000 a year thereafter. Louis also bought Rousillon, the bit of Aragon that lay north of the Pyrenees, for 300,000 ducats, and inherited Provence, adding both to the French royal domain.

Louis XI, "the Spider King."

The Wars of the Roses, Phase 1 (1455-65)

By the mid-fifteenth century, the situation in England and France was just the opposite of what it had been forty years earlier. Having come out of the Hundred Years War triumphant, France now had more prestige, a strong monarchy and the strongest army in western Europe. By contrast, England was exhausted, and saddled with a weak king and thousands of unemployed ex-soldiers. In 1450 there was a revolt in Kent and surrounding counties ("Jack Cade's Rebellion"), which combined soldiers who wanted the back pay owed them, with peasants and small landowners angry about high taxes and corruption. The rebels were dispersed when they reached London, but that was only a prelude. The next time tensions boiled over, they produced a thirty-year, on-and-off civil war, now called the Wars of the Roses.(20)

All three of England's Lancaster kings (1399-1461) were incompetent; Henry V was good at leading armies and nothing else, while Henry IV and VI didn't even have that much talent. Meanwhile, the noble houses struggled among themselves to gain control over both Parliament and the crown. Henry VI was mentally unstable to begin with, and suffered a complete nervous breakdown in December 1453. Richard, the duke of York and the king's cousin, used this occasion to declare himself royal protector over both Henry and his newborn son, Edward. The first thing he did after that was to dismiss the group of nobles around the king and queen called Lancastrians, who were accused of losing the Hundred Years War and were thus unpopular. Then in February 1455 Henry recovered and brought back the Lancastrians, who of course ousted Richard from his privileged position. Richard's response was to organize his own followers, henceforth known as the Yorkists, and raise an army of 3,000. This force marched on London, and met the Lancastrian troops in the town of St. Albans, where the first battle of the civil war took place (May 22, 1455). Casualties were light (about 300), but the resulting Yorkist victory was completely unexpected by the other side, and the Lancastrians withdrew. The Yorkists captured Henry and escorted him back to London, while Queen Margaret and Prince Edward got away.

Because Duke Richard had won the first round, the Yorkists were on top of it all for the next four years. But then in 1459 the Lancastrians won their first victory, the battle of Ludford Bridge. The queen declared Yorkist lives and property forfeit, and Richard fled to Ireland. However, nine months later the number two Yorkist, Richard Neville, the earl of Warwick, brought his army to London for a rematch, and one of the Lancastrians, Lord Edmund Grey of Ruthin, switched sides, allowing the Yorkists to win easily and capture King Henry again. The Queen fled to Wales, Richard returned, and after a round of negotiations, Richard persuaded Parliament to proclaim him the royal heir, instead of the king's son. Naturally the queen would not stand to see her son disinherited, and she raised a new army. The two sides met at the battle of Wakefield, near York (December 30, 1460), and this time it was a great mismatch: 18,000 Lancastrians vs. 8,000 Yorkists. Consequently, Duke Richard was killed.

Though Richard's death eliminated the main reason for the war, his followers were too angry at their enemies to call it quits. The earl of Warwick (now called "Warwick the Kingmaker") took command of the Yorkists, and the Yorkists now fought for the cause of Richard of York's son, Edward of York. This meant England now had two kings, and that wasn't a situation that could be settled peacefully. Both sides called up as many soldiers as possible, and the nobility came along to lead them, so when the two armies met again, at Towton on March 29, 1461, it was the medieval version of Armageddon.(21) The battle of Towton went on all day because of a snowstorm and the size of the armies involved, and ended with a total victory for the Yorkists. The Lancastrians were beaten so badly that they could not raise another army for the next three years, and King Henry, the queen and their son fled to Scotland. The following June, Edward of York was crowned as King Edward IV. Henry tried sneaking back into northern England in 1465, only to be captured and locked up in the Tower of London. Meanwhile, King Edward proved himself a competent ruler; he controlled the nobles, even keeping a few harmless Lancastrians at court, and won the support of the middle class. As was the case after the twelfth century civil war, everyone in England preferred one royal tyrant over many little tyrants. Because of his success, Edward's power became practically absolute, foreshadowing the strong rule of the Tudors in the future.

The Wars of the Roses, Phase 2 (1469-71)

The promise of the House of York started to fail because Edward and the earl of Warwick argued on many issues. The worst dispute involved marriage; Warwick wanted the king to marry a French princess, but instead Edward secretly wed a gorgeous commoner, Elizabeth Woodville. Because of her, the Woodville family suddenly went from rags to riches, and gained so much prestige and power that the rest of the nobility, even the York family, were marginalized. This included Edward's brother, George Duke of Clarence, and Warwick. When he couldn't take it anymore, Warwick defected and fled to France, where many of the Lancastrians were in exile (1469). In 1470 he returned with a new army, while Edward was putting down a revolt from his brother George in the north, and restored Henry VI to the throne. Now it was Edward's turn to flee to the Continent, and the Burgundians helped him raise a new army of his own. Thus, in 1471 Edward also came back, and captured the hapless Henry VI once more.

The battle of Barnet.

This time the big showdown between the armies took place at Barnet, eleven miles from London, on Easter Sunday (April 14, 1471). Whereas Towton had simply been an awful bloodbath, Barnet was a scene of confusion, where most of the archers and gunners did not know what they were shooting at, and a lot of the casualties were wasted dead, killed by "friendly fire." The night before the battle, the Lancastrians tried to decimate their opponents with an artillery bombardment, but in the dark they did not know the exact location of the Yorkists, and most of the cannon fire missed. At dawn Edward gave the order to engage the enemy, only to find that a thick fog--the first time the famous London fog was reported in history--had settled on the battlefield. Because the Lancastrian army was larger (15,000 vs. 12,000 Yorkists), its right wing scattered the left wing of the Yorkist army; however, the murky fog kept the Yorkist center and right wings from knowing it, so they continued to advance. Then came the friendly fire incident, when the Lancastrian right turned around to rejoin the rest of the army, and the fog caused it to unexpectedly run into the Lancastrian center. At this late stage in the Middle Ages, most knights wore plate armor (see footnote #14), so the only way to identify officers and nobles was by the banners they carried, or by the emblems on their shields. The soldiers on the right wing used a starburst for their identification, and the men in the center mistook the starburst for a sunburst, the emblem of King Edward, so they shot arrows at their buddies. The men on the right fled this assault with cries of treason, discipline broke down all over the Lancastrian side, Edward threw in his reserves, and the Lancastrians were routed; Warwick was killed as he was looking for his horse, in an attempt to escape.

Queen Margaret and her son arrived in England on the same day as the battle of Barnet. When she heard what happened, she tried to flee to Wales again. The Yorkists caught up with the queen and her retinue, and in the battle of Tewkesbury (May 4, 1471), the queen was captured and Prince Edward was slain. Henry VI was imprisoned in the Tower of London again, where he died a month later. This may have been a murder, but Henry was so feeble at this point that it didn't matter much anymore. The House of Lancaster became extinct, and with most of the English nobility either dead or on Edward IV's side, followers of the Lancastrians transferred their allegiance to Henry Tudor, a Welshman and 4th-generation descendant of Edward III. Henry Tudor played it safe by fleeing across the English Channel to Brittany, along with his uncle Jasper Tudor; they ended up staying in France for the next fourteen years.

The Wars of the Roses, Phase 3 (1483-85)

For the next twelve years Edward IV ruled as undisputed king. The third and last phase of the wars began when he died in April 1483, and left behind two sons, Edward and Richard, and five daughters. Most people expected the eldest boy would become the next king (we now call him Edward V for that reason), but because he was only twelve years old, Edward IV's brother, Richard Duke of Glouchester, stepped in. First he declared himself the latest royal protector, then he put the two princes in the Tower of London (for safekeeping, of course). But that wasn't all; Richard had Lord Hastings, a trusted advisor of Edward IV, executed on charges of treason, and declared the marriage of Edward IV to Elizabeth Woodville invalid--a move which not only took away the status of the Woodville clan, but also disqualified Edward IV's children for the throne. With everyone that might prevent the coronation out of the way, he crowned himself King Richard III in July. "The Princes in the Tower" were never seen after that; presumably they were murdered.

Though Richard III only ruled for two years, the common folk of England liked what he managed to get done. First, he accepted a cease-fire to end a war with Scotland that Edward IV had fought in 1482. Because he did not understand Latin, Richard kept an English-language Wycliffe Bible, and he ordered the courts to conduct trials in English, rather than in Latin. And for poor defendants who could not afford a lawyer, Richard started the practice of having the state appoint public defenders. However, in the fifteenth century history was written not only by the winners, but also by the nobility, and they didn't have to like a king just because he made life easier for his subjects. After his reign ended, only Richard's enemies were left; by the time William Shakespeare wrote the line "My kingdom for a horse!", Richard had been typecast as a villain, and that is how most have seen him in the centuries since then.(22)

Richard's position on the throne had never been secure, and because most believed that he was responsible for the deaths of his nephews, his enemies now had an easier time gathering followers than he did. The first to try a revolt was Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, and this is called Buckingham's Rebellion (October 1483). Richard put it down in a few weeks, but he couldn't stop other nobles from joining the opposition; his isolation also grew because of the death of his only son in 1484, and of his wife in early 1485. Then a rumor went around that for his second wife, Richard would marry Elizabeth of York, his own niece and Edward IV's oldest daughter; this outraged England almost as much as the deaths of the princes. Not long before that Henry Tudor had vowed to marry Elizabeth, so to stop Richard, there was no time to lose. In August 1485 Henry returned to Wales, and marched east to challenge Richard; Richard likewise rode west to engage Henry.

The two sides met at Bosworth Field, in the center of England, on August 22, 1485. We don't know the size of the armies involved, but after a century and a half of fighting in France and England, it's a safe bet that there weren't as many soldiers available as there had been previously. Current estimates put Richard's army at 10,000 men, and Henry's army at 5,000. Backing up Richard's army was a baron named Thomas Stanley, who brought another 6,000 men and his brother, Sir William Stanley; remember them! Therefore the battle started off with Richard having the advantage, which was further helped by the fact that Henry had not fought in a battle before. At one point, Henry and his bodyguards got separated from the rest of the Tudor-Lancastrian army and seeing this, Richard charged with his own guards, hoping to end the battle quickly by taking out Henry.

This was when the Stanley brothers proved to be the wild card that decided the battle. During the Wars of the Roses, Thomas Stanley had been the ultimate opportunist, serving all three kings (Henry VI, Edward IV and Richard III), always siding with whoever happened to be winning at the time, and avoiding battles as much as possible. It was an inglorious strategy, but it allowed the Stanley family to conserve its strength, and each king rewarded them with lands and titles; that's why the Stanleys could field an army almost as big as the king's. At Bosworth Field they stayed on the sidelines, waiting to see which way the wind of fate would blow, instead of actively helping the king to get Henry. When Henry drew close to the Stanleys, and Richard charged Henry, the Stanleys made up their minds at last. Richard got close enough to kill Henry's standard bearer, and then Sir William Stanley led his men into the fight, to defend Henry. Richard's group was outnumbered, surrounded, and forced into a marsh, where Richard was unhorsed and he fought on foot until enemy soldiers killed him.

According to tradition, after the battle, Richard's crown was found in a bush and placed on the head of Henry, making him King Henry VII. Because of that event, you can say England was a medieval nation when Richard III rode to Bosworth Field, and it became a modern nation when Henry VII left the place. Henry kept his promise to marry Elizabeth of York, and because she was the last claimant to the throne from the York family, the marriage made Henry an acceptable king to everybody. With that coronation and wedding, the Wars of the Roses were over, and the age of the Tudor dynasty began.

Showdown in Spain

While the flower of England was getting slaughtered in the Wars of the Roses, Spanish Moors and Christians wrote the final chapter in their long struggle. The last Moslem state on the peninsula, the Emirate of Granada, became the vassal of Castile after the Moors lost Seville in 1248, and only sporadic fighting took place for the next two hundred years. The Christian part of the peninsula was less divided than before, but still contained four states: Portugal, Castile, Navarre and Aragon. Portugal's involvement in the Reconquista ended when Castile got the land between Portugal and Granada. Henceforth, the Portuguese would have to go to Africa to fight Moors. There was an on-and-off war between Portugal and Castile from 1369 to 1388, where the Portuguese, with English help, succeeded in defending Lisbon from Castilian attacks, though they failed to place a Portuguese prince on the Castilian throne (that was the issue that started the conflict). Navarre was a small Basque kingdom that kept to itself in the Pyrenees. That left Castile and Aragon to champion the cause of Christendom.

Of those two, Castile was the land power, holding more than half of the interior, while Aragon had the east coast, the Balearic Islands, Sardinia, Sicily, and a fleet to go between those territories. The catalyst which brought them together was one of history's most successful political marriages; King Ferdinand V of Aragon married Queen Isabella I of Castile in 1469. Unlike similar unions in the past (e.g., the ones involving the Hapsburgs and Luxemburgs in eastern Europe), this merger became permanent, guaranteeing that someday a child of Ferdinand and Isabella would inherit both kingdoms. Ferdinand seems to have had a modern attitude concerning women; the family motto was "They rule with equal rights and both excel, Isabella as much as Ferdinand, Ferdinand as much as Isabella."

The truce between Moors and Christians was broken when Muley Abul-Hassan, the second to last ruler of Granada, raided the Zahara fortress in December 1481, enslaving the Christians he captured. The marquis of Cadiz responded with his own surprise attack, taking Alhama, a town close to the city of Granada; then Ferdinand showed up with the main Christian army. After that it was a long war of attrition, with the Spanish army attacking on land, while the Spanish fleet stood offshore to prevent the Moors from receiving reinforcements from Africa, a move which would have delayed the final triumph of Christendom one more time (remember where the Almoravids came from). Queen Isabella personally took part in some of the land battles, seeing the war as a latter-day crusade.

The war could have ended in 1483 when Abul-Hassan's son, Mohammed XI Abu-Abdullah (called Boabdil by today's Spaniards), was captured; he recognized Ferdinand as lord of Granada to gain his freedom, but Abul-Hassan rejected it. Abul-Hassan died in 1485, and Boabdil inherited a kingdom that was being ground out of existence, like Carthage in the Third Punic War.

Renaissance Italy

The decline of the Holy Roman Empire left a power vaccuum in Italy that nobody could fill, for right after the Papacy won, it got entangled in the mess we described earlier, culminating with the Great Schism. After the popes moved to Avignon, towns within the Papal State like Urbino and Bologna had no central authority over them, so their mayors and dukes effectively ruled independent city-states for much of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In the absence of both pope and emperor, five kingdoms tried to rule the peninsula: Naples(23), the Papal State, Venice, Milan and Florence. Between them were weaker city-states like Genoa, Lucca, Siena, Savoy, Modena, Ferrara and Mantua; their rulers lived and died according to their political skills in an unscrupulous game of diplomacy and skullduggery, where bribery, assassination and usurpation were all likely to happen(24). A fourteenth-century observer might not have imagined Italy as a good place for the next flowering of human culture, but artists and writers can thrive in political chaos, as classical Greece showed us.

We have met most of these Italian states already; Florence was the newest player on the scene. There had been towns on the site of Florence for two thousand years--the Etruscans had one called Fiesole, the Romans had one called Florentia--but they were never very important. Medieval Florence began its rise to greatness by replacing feudalism with capitalism in 1228, and by introducing a new constitution which declared that only the guilds would govern the republic. With the "Ordinance of Justice" (1293), all of the old-style nobles were excluded from politics. In 1409 Florence annexed Pisa, a move which eliminated a rival and gave it a port for its growing commerce.

At the same time, the city government engaged in a conscious program of urban renewal, replacing the congestion of dank, flimsy tenements with more open architecture, stone-paved streets, and a new city wall by 1299. Nor did the city's rulers stop there, for they had developed a taste for art and commissioned it on a scale previously unheard of. In the first thirty years of the fourteenth century, thirty-four statues of saints and prophets went up in squares and public buildings, all carved with the kind of skill that had not been seen in a millennium. Above everything else rose a new cathedral, begun in 1296 and completed in 1436 by Filippo Brunelleschi(25). The cathedral's red dome became the symbol of Florence; Florentines traveling abroad said they suffered from "dome-sickness" when they missed their home city.

Officially Florence was a republic, which in the Middle Ages meant an oligarchy, but the people of Florence talked about their government as if it was a democracy. In practice, however, just one family ran Florence during its best years--the Medicis. This unofficial dynasty began when its first patriarch, Giovanni di Bicci de Medici (1360-1429), founded the family firm in 1397. This was a holding company which controlled a major bank, several local industries, and various trade enterprises. Of these, industry was the least important, producing just ten percent of the profits. The traders did better, especially when they handled imports from the Orient and the Papal alum monopoly, and the bank was the biggest money generator of all. This bank did not grow as large as the fourteenth century banks of the Bardi and Peruzzi families, but it had very important political connections, especially with the court of France and the Papacy. Giovanni used his wealth to make the Medicis more popular than the ruling family, the Albizzis, but unlike his successors, he did not dive completely into the political arena for control of Florence.

Giovanni's son, Cosimo de Medici (1389-1464), was the first member of the clan to dominate Florence. A shrewd businessman, Cosimo greatly enlarged the Medici family firm, building branch offices all over Italy and beyond. In politics, he risked everything more than once; Rinaldo degli Albizzi had Cosimo exiled from Florence in 1433, but one year later Cosimo returned and got the Albizzi patriarch banished. Government loans were a favorite political tool of his; both Venice and Naples suffered military defeats after Cosimo refused to loan the money they needed to fund their armies. A large portion of his company profits were plowed back into the business, but Cosimo also spent a considerable amount on political patronage, bribes--and the arts. Like many other Florentine leaders, Cosimo was a cultured man, who realized that promoting art was a good long-term investment for the city. The Platonic academy he founded in 1440 attracted humanist writers (see below) to Florence, and Cosimo gave them the same toleration he gave to the painters, sculptors and architects: "One must treat these people of extraordinary genius as if they were celestial spirits, and not like beasts of burden." True to character, and to the dismay of his enemies, he lived to a ripe old age, and died peacefully while listening to a reading from Plato.

Cosimo's son Piero (1416-69) only ran the family fortune for five years, due to the chronic poor health that earned him the nickname "Piero the Gouty." His heir, Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-92), was the family's most talented member. He never held any noble title, but ruled Florence with almost regal power; once he even got away with dipping into public funds to restore the family's credit rating. Under him Florence experienced what some call a "second Periclean age," because Lorenzo was an extravagant patron of the best artists he could find, including Sandro Botticelli and Michelangelo. When he added up what the Medicis had spent between 1434 and 1471, for commissions to artists and architects, donations to charities, and taxes, it came to the astounding total of 663,755 gold florins, causing him to remark: "I think it casts a brilliant light on our estate and it seems to me that the monies were well spent and I am very well pleased with this."

Lorenzo's skill with statesmanship brought peace to Italy for most of the late fifteenth century, while his athletic and intellectual talents made him a perfect example of the "Renaissance man." His only weakness had to do with money; somehow he never learned the business education that his predecessors had, and his lavish spending on art and public spectacles drained the accumulated family fortune. Furthermore, he did not seem to have Cosimo's knack for choosing the right people to manage the Medici company's branch offices. Each office was largely autonomous, meaning that it had to be run with little or no direction from Florence, but the men Lorenzo appointed were too hesitant to function well on their own. The result was some bad business decisions. The London office, for example, agreed to bankroll the king of England; that office went bankrupt in 1472 because all hopes of repayment on the loan vanished in the Wars of the Roses. The office in Bruges suffered the same fate; despite stern warnings from Florence, it gave credit to Duke Charles of Burgundy, and we saw what happened to him! Thus, Lorenzo bequeathed a much smaller treasury to his son Piero di Lorenzo.

However, even Lorenzo had enemies. In 1478 the rival Pazzi family tried to assassinate him during a mass in Brunelleschi's cathedral; Lorenzo escaped, but his younger brother Giuliano fell victim to their daggers. Lorenzo showed no mercy in hunting down the perpetrators; within hours he had several of them hanging from the palace windows, and he commissioned Botticelli to do a picture of their dangling bodies. A few years later he had another conspirator dragged back from Constantinople, and a young artist named Leonardo da Vinci depicted that execution. The victims of Lorenzo's wrath included the entire Pazzi family, an archbishop and a teenage cardinal (the nephew of Pope Sixtus IV), resulting in a brief war with the Papacy and its ally, King Ferdinand of Naples. It was bribery, however, rather than a military victory, that decided this conflict; while the Florentine force slowly retreated to Florence, Lorenzo made a secret journey to Naples, and persuaded Ferdinand to drop out of the war with a generous gift of gold. Without his ally, the pope soon had to abandon the struggle.

Nobody in Italy had a large army at this time, so all wars were short. This was because the nature of warfare was changing rapidly, and the nations of the day had a hard time training men fast enough to keep up with it. Since the late fourth century, cavalry had been necessary for victory and usually dominated the battlefield. However, infantrymen now had weapons that allowed them to win battles without the support of knights: longbows, pikes, and (after 1500) guns. The medieval knight was nearly self-sufficient, once he had a horse, arms & armor, and training in their use; he needed only a few peasants and smiths to maintain his lifestyle. Now that feudalism was on the way out, knights were in short supply, and peasant levies were useless against a force the knights couldn't stop. The weapons that drove knights and armed peasants off the battlefield were more complicated than anything used before; they required supplies of gunpowder and shot, oxen and wagons for the movement of cannon, a camp of noncombatants to keep the equipment in good shape, and money to pay for everything. The new weapons also required more training and discipline to use properly, especially when defending against a cavalry charge. All this was too much for most nobles to handle, so they lost their ability to wage organized violence against their fellow barons and dukes. The end result of these changes was more military power concentrated in the hands of the head of state, and the same amount of resources going to support a smaller army.

In the case of Italy, it was hard to recruit soldiers when banking and trade offered more attractive ways to make a living. To fill the manpower gap, each Italian state hired bands of mercenaries, led by captains called condottieri ("contractors"). But mercenaries fight strictly for money, not for patriotism or glory. The condottieri had to be businessmen first and generals second, and they were reluctant to waste expensive men and equipment. Thus, a campaign usually saw more tactical maneuvering than battles, and was likely to end in a negotiated settlement before much bloodshed took place. Mercenaries were also a risky business because they would switch sides when somebody showed them enough gold, and a successful mercenary captain might try to overthrow his employer, as Francesco Sforza did when he seized power in Milan (1450). The most famous mercenary captain during this period was an Englishman named Sir John Hawkwood (ca. 1320-94); before 1360 he fought in the Hundred Years War, and afterwards his unit, the "White Company," did so well in northern Italy that the city of Florence hired him in 1377, so in effect the White Company became the Florentine army for the last seventeen years of Hawkwood's life.

Despite the shortcomings of this age, many Italians felt there had never been a better time to live. From their point of view, a great curtain had descended when the Roman Empire fell, and now they were the ones who were joyfully raising it up again. Matteo Palmieri echoed the feelings of many when he wrote in the mid-fifteenth century that every man should "thank God that it has been permitted to him to be born in this new age, so full of hope and promise, which already rejoices in a greater array of nobly-gifted souls than the world has seen in the thousand years which preceded it." And while we would say the political system left much to be desired, the common man had more opportunities for civic involvement in the republics than he did in any monarchy. Because Italian states were so small, the politically active citizen found it easy to keep up with the latest news, something not possible in large nations before the invention of mass media, and the variety of governments allowed political experimentation. All this activity at the end of the Middle Ages encouraged everyone to bring their talents into the open, whether for art or business--and competition sharpened those talents.

The Early Renaissance Men

Several individuals from the Renaissance era are familiar to us, but they aren't the politicians and mercenaries of the previous section. The "Renaissance men" we think of are the self-confident, multi-talented artists and writers who brought classical civilization back to life, after centuries of hibernation. Thus we mainly remember 14th-16th century Italy for individuals like Petrarch, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Raphael, and Niccolo Machiavelli.

Nowadays we put history in compartments marked by time and place, like Ming dynasty China, and the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms of Egypt. This makes learning the past more convenient for us, but we have to remember that most of the people who lived long ago did not see anything special about their lifetimes. This was especially the case during the Middle Ages, when the average peasant must have found it nearly impossible to imagine a way of life different from the one he had. The men of the Renaissance were the first to see themselves as being in a unique age. These were the inventors of the term "Dark Ages" to describe the period following the fall of Rome, and these people coined the name "Renaissance" (from Il Renascimento, meaning "rebirth") to describe their own time. They were also the first to identify a civilization by the culture it produced, instead of by its religion or system of government. However, they did not see civilization as an evolutionary process where life gradually got better, the way many people do today; rather they saw themselves as the ones who recovered the best things from ancient times. To them, the way to become "modern" was not by inventing something new, but by imitating the Romans.

Several factors worked together to ignite the Renaissance in Italy. We already mentioned the first one, wealth. The others were the re-discovery of classical literature, and memories of better times.(26) The Roman Empire may have been gone for nearly a millennium, but the Italian could still see Roman ruins wherever he went, so he knew that his people had once been great. When he read the works of Virgil or Cicero, he did not see them as the dry writings of long-dead authors, but as the voices of his own ancestors. And those writings were now becoming more available. Previously Greek and Roman literature was limited to what monks had copied and saved in monasteries, or Arabic translations from Spain. In the early fifteenth century this trickle of knowledge became a flood, as Byzantine scholars left the doomed city of Constantinople, taking their ancient Greek manuscripts with them.(27) Most of them went to Italy, because it was the nearest land under Christian rule, and those Italians who understood the manuscripts couldn't get enough of them. They also noted that the ancient authors did not blindly accept authority, but argued among themselves; that was both shocking and invigorating. And because these authors were more interested in human affairs than they were in the gods, they encouraged their readers to revive the old philosophy of humanism.

The author who bridged the gap between medieval and modern literature was a native of Florence named Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). Dante is best known for writing The Divine Comedy, a journey through hell, purgatory and heaven. Dante's subject matter was thoroughly medieval, but the dates of his lifespan place him right at the beginning of the Renaissance era. We should also note that for the first half of The Divine Comedy, Virgil was his guide, a plot element one would expect from a Renaissance author like Petrarch. Most important of all, he wrote in Italian, not Latin, thereby opening up written literature to the masses of Italy.

One of the first writers to use the classics for inspiration was Francesco Petrarca (1304-74), known to us as Petrarch. Born in the town of Arezzo, he got his education first at the Papal court in Avignon, and then at the University of Bologna. Petrarch was both a talented scholar and poet, and traveled widely. His favorite hobby was collecting ancient manuscripts, and he told those he entertained that it was time to dispel "this slumber of forgetfulness" and to "walk forward in the pure radiance of the past." He behaved accordingly when he wrote his most famous book, Letters to Ancient Authors, an anthology of the letters he had written to classical authors like Homer and Plato, as if they were still alive. Petrarch had an immense following during his lifetime, and in the fifteenth century most libraries included copies of his works.

Contemporary with Petrarch was Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375). Boccaccio is best known for a collection of short stories called the Decameron. The setting for the Decameron is northern Italy at the time of the Black Death; when the plague hit Florence, a group of young people, seven women and three men, escaped it by leaving the city, to spend ten days at a country villa. To pass the time, they had a storytelling contest; each of them told a story every day, and all of that day's stories followed a previously agreed upon theme. Some of these stories were probably composed before Boccaccio's time, but the characters were given names that any fourteenth century reader would recognize, to bring them up to date. Also, many of the stories are racy tales about love, so they leave you thinking that the youths may have been telling stories to keep out of trouble, but the ones they chose to share were more likely to get them into trouble! After meeting with Petrarch, Boccaccio also wrote the Genealogia deorum gentilium (Genealogy of the Gentile Gods), the first encyclopedia of mythology. If you have ever read pre-Christian literature, you will know that ancient authors mentioned the names of many gods constantly, so a separate work telling who the gods were and the myths involving them can definitely come in handy. Finally, we should note that Boccaccio, like Dante and Petrarch, wrote in Italian; Boccaccio's works made it possible to enjoy the classics without a college education.

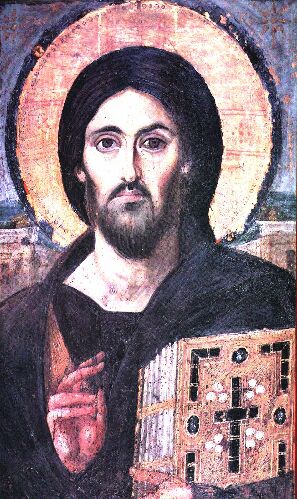

While writers tried to imitate the styles of the classics, artists ventured into new realms. The examples we have of ancient Roman painting, like the murals of Pompeii, show natural-looking figures, and we can believe real people posed for them. By contrast, most medieval painters imitated the style of the icon-makers in the Byzantine Empire, where symbolism mattered more than substance. Medieval art has a two-dimensional look; the figures are stiffly posed, and their feet do not touch the ground. They only look realistic when they cause an adult to imagine a certain scene, in the same way that a child can see people in the stick figures he draws. The artists got no respect, either; working in the shops of craft guilds, they were paid by the amount of work they put out, and had to follow strict guidelines on how paintings, armor, wooden chests, etc. should look. They couldn't even sign their creations. It would have been unthinkable for an artist to put a self-portrait in his work, the way Lorenzo Ghiberti did when he made the bronze doors for the baptistry of Florence.

As the artists' work improved, so did their social standing. Leon Batista Alberti came from an aristocratic family, Michelangelo's father was a city magistrate, and Brunelleschi and Leonardo had respectable middle-class backgrounds--but most of the rest were rank commoners, coming from families of barbers, butchers, farmers, tanners, poultry dealers and tailors. At first they didn't have much income, and they had to join a guild and follow its rules. In 1434 Brunelleschi was thrown into prison when he refused to pay the dues of his guild, and Church officials had to get him out so he could finish the cathedral of Florence. However, as their status changed from that of craftsman to that of genius, their expectations grew; some studied the classics and made it a point not to overindulge in drinking and chasing women, so that they would become still more respectable. Donatello, the great sculptor of Florence, was too embarrassed to wear the fine clothes that Cosimo de Medici gave him, but a century later, Titian, Donato Bramante and Raphael lived like princes. They also grew more confident. A goldsmith named Bernardo Cennini, for example, had no training as a printer, but designed, cut and cast the type for a superb edition of a commentary on Vergil. At the end of the book he wrote Florentinis ingeniis nihil ardui est--"nothing is beyond the powers of the Florentines." Such an attitude had not been spoken since the days of classical Greece.

The Middle Ages were still going strong when the artist who broke tradition appeared. This was Giotto di Bondone in Colle di Vespignano (1267-1337), Giotto for short. The son of a goatherd near Florence, he became an apprentice of Giovanni Cimabue, the greatest artist of the day, when he was twelve years old, but eventually the student outshone the teacher.(28) All of Giotto's paintings dealt with religious subjects; the difference was that he experimented with new techniques to portray people as realistic as possible. One legend asserts that he did this because he spent his childhood with livestock, rather than cooped up in a monastery. Thus, like the Cro-Magnon artists (see Chapter 1), he had a deep knowledge of how animals should look. Late in life, he was placed in charge of building and decorating the campanile (bell tower) of Florence; he did not live to see it completed, but it is still called Giotto's Tower in his honor.

Few of Giotto's works remain in good condition, because seven hundred years have passed since their creation. He rejected the bright, jewel-like colors and stiff poses of the Byzantine style, preferring a gradual shading of the faces and limbs of his characters, and he placed them in active, natural poses. Because nobody had discovered the techniques of perspective yet, Giotto's style still looks two-dimensional to us, but to fourteenth-century observers his work was marvelous. For example, when Pope Boniface VIII decided to employ Giotto in Rome, he sent a letter asking for a sample of his work. Giotto responded by dipping a brush in red paint, and made a perfect circle with a single stroke; he told the pope's messenger to take that, stating that someone with an eye for talent will recognize that a true master painted that circle. The pope did, and Giotto was hired.

Not much happened in Italian art for a century after that; the artists of those days mainly repeated what Giotto had done. As Leonardo da Vinci explained: "Afterwards this art declined again, because everyone imitated the pictures that were already done . . . until Masaccio showed by his perfect works how those who take for their standard anyone but nature--the mistress of all masters--weary themselves in vain." Masaccio (1401-28) did not live long, but he led the way in technical development. By adding the effects of light and shading (chiaroscuro), Masaccio successfully duplicated the effect of draping clothing and made his figures stand out from the background, which was now painted with less detail so that it would not distract the eye from the main subject. Meanwhile, Filippo Brunelleschi scientifically plotted the laws of linear perspective for the first time. Masaccio used perspective in his works right away, and other artists found the concept so interesting that they eagerly learned geometry, until even second-rate painters knew enough mathematics to draw the relative size of objects correctly. The same quest for realism also encouraged artists to study human anatomy; a few overcame their revulsion and dissected dead bodies, so that they would literally know their subjects inside and out.

The sculptors and architects had more classical-era examples to study than the painters did; their challenge was discovering how the ancients did it. Here the main pioneers were Ghiberti (1378-1455), Donatello (1386-1466, his real name was Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi) and Andrea del Verrocchio (1435-88). Ghiberti's main work was the set of bronze doors we mentioned previously; featuring twenty-eight panels decorated with New Testament scenes, this project took forty-four years to complete. Donatello, a student of Ghiberti, created the first nude statues since ancient times, and now is considered the first modern sculptor. Verrocchio was a master with both anatomy and technique, and he showed it by making a daring statue of a knight on horseback--with one of the horse's legs raised.

One reason why Florence produced so many artists was because the Florentines realized that great art could serve as propaganda. It gave their city a good press when Giotto was employed elsewhere, as far away as Naples. By the time of Lorenzo de Medici, artists were the city's cultural ambassadors. Lorenzo had that in mind when he recommended his favorite architect, Giuliano da Sangallo, to the king of Naples, and suggested that Domenico Ghirlandaio and Botticelli paint frescoes in the Sistine Chapel for Pope Sixtus IV; he probably also supported Leonardo da Vinci's application to work for the duke of Milan. The artists responded in kind; when Botticelli, for example, painted the Adoration of the Magi, he gave the Three Wise Men faces that matched his Medici patrons!

Economics at the End of the Middle Ages