| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A History of Europe

Chapter 8: THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES, PART I

1000 to 1300

This chapter is divided into two parts, which cover the following topics:

Part I

Part II

| Commerce in the High Middle Ages | |

| Population Growth and Medieval Republics | |

| The Plantagenets | |

| Centralization in France | |

| Frederick II, Il Stupor Mundi | |

| The Mongol Horde in Poland and Hungary | |

| The Embattled Empire | |

| The Magna Carta and the First Parliament | |

| Pope or Bust | |

| The Evolution of Castles | |

| Central Europe's Technological Experiment |

Basil the Bulgar-Slayer

There's no question about it; Basil II (976-1025), also known as Bulgaroctonus ("Bulgar-slayer") was the greatest Byzantine emperor after Justinian. That is why two sections of this work are devoted to him, along with the fact that the first twenty-four years of his reign came before the millennium began, so Basil's early years were covered in Chapter 7. The reason for his success was that he was quite unlike other medieval rulers. In an age known for the pomp of kings, this emperor lived like a Spartan. There was nothing glamorous about him; his speech was plain, his manner was abrupt and direct, making him appear coarse in the eyes of his court. According to one eleventh century author, Michael Psellus, "He even went so far as to scorn bodily ornaments. His neck was unadorned by collars, his head by diadems. He refused to make himself conspicuous in purple-colored cloaks and he put away superfluous rings, even clothes of different colors. On the other hand, he took great pains to ensure that the various departments of the government should be centered on himself, and that they should work, without friction." During the Empire's frequent wars, he was more likely to be marching in the field with his soldiers than giving orders from the safety of his palace, as most emperors had done. He also liked farmers, because many soldiers were ex-peasants, and passed laws to protect farms and keep their taxes low, while raising taxes on the nobles he scorned. Finally, as mentioned previously, he had incredible patience, which made him move as slow as a glacier--and against rash opponents, it made him just as unstoppable.

Basil II.

We saw in Chapter 7 that when Basil first met the Bulgars, it was a humiliating defeat (986). After that the Bulgars grew bolder, occupying nearly all the land between the Adriatic and Black Seas, and raiding in Greece all the way to Corinth. By 990 Samuel, the Bulgarian tsar, was spending so much time in the south that he moved his capital to Ochrid, in the southwest corner of present-day Macedonia. In 997, at the battle of Spercheios, one of Basil's generals, Nicephorus Uranus, inflicted a defeat so severe, that Samuel and his son Gabriel only escaped by playing dead among the Bulgarian corpses. After that the Byzantine army recovered Greece, but the Bulgars were still a threat to Constantinople. Basil knew that to eliminate the danger he would have to strike back, and to make sure it was done right, he would have to go with the army; however, he was distracted for the rest of the tenth century, mainly by Moslem attacks from the east. It took two campaigns led by Basil (995 and 998) to stop Moslem meddling and secure the eastern frontier. Fortunately the truce Basil signed with the Fatimids endured; it wasn't even broken when the Fatimids annexed Aleppo (1004), a vassal city of Byzantium, or when the Fatimids destroyed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (1009). That allowed Basil to concentrate his attention and resources on the Empire's main enemy in Europe, the Bulgars.

While preparing for the Bulgar-Byzantine rematch, a tremendous opportunity came from the west. The Holy Roman emperor, Otto III, was now old enough to marry, so he sent envoys asking for a Byzantine bride. Because the earlier marriage between the Byzantine and Russian royal houses had helped a lot, Basil accepted, and he sent his niece Zoe. However, this marriage did not take place, because Otto died before Zoe arrived. If Otto and Zoe had gotten married, any son of theirs would have become heir to both the Holy Roman and Byzantine Empires, thus uniting east and west in the way Charlemagne had tried, when he sent a marriage proposal to Empress Irene. Those readers who are interested in alternate history will enjoy speculating on how different European history would have been, if such a union had occurred.

Basil's counteroffensive against the Bulgars began in 1002. Samuel could not have been too concerned, because the last time he fought Basil, he won. But eventually he realized that Basil was not like any other opponent he had faced. I say "eventually" because instead of going forth against the enemy in an impressive cavalry charge, Basil used the same guerrilla tactics as his opponent, and subjected the army to a constant series of drills and inspections. He also pulled a diplomatic trick, by inviting Venice to invade Dalmatia and hold it for the Empire. The Venetians were glad to oblige, because they always needed more wood to build ships, and that meant Samuel would have to fight a two-front war. When the Byzantine army finally started moving, it was a slow, cautious force, but larger and better trained than anything the Bulgars had. Even bad weather did not stop the lumbering Byzantine advance; unlike most ancient and medieval commanders, Basil did not call off the campaign when winter arrived, but stayed in the field constantly, whether it was hot or cold. The Balkans are full of rugged terrain, and Samuel retreated into the mountains of Bulgaria. His best hope was to pick off isolated units, wearing the Byzantines down until they were tired of fighting, or holding out until Basil was called away by trouble on other fronts. None of these things happened, though. Basil had learned from his mistakes, and would not walk into a trap again, the way he had at the Gates of Trajan. He would have agreed with whomever said, "Revenge is a dish best served cold," and did not speed up his advance when he saw he was winning. Bit by bit, he chipped away at the Bulgarian empire. In 1005 the governor of Durazzo (modern Durres, Albania) went over to Byzantium; by 1006 Byzantine forces had returned to the Danube, and the whole eastern half of the Bulgarian empire was theirs.

The war climaxed with a terrible victory in the summer of 1014. This was the battle of Kleidon (also called Clidium, Belasitsa, or Balathista). By this time, Samuel was in serious trouble with the Bulgarian nobility, so he chose to take a stand in a narrow valley. It might have worked, had it been a set battle with one army charging the other, but as the Persians did at Thermopylae, Basil found a path around the valley and sent part of his army there, trapping the Bulgars by blocking the way out. At least 14,000 Bulgars were captured, and thousands more were massacred. Samuel himself escaped to the Macedonian city of Prilep, so Basil returned Samuel's army to him. All 14,000 prisoners were blinded, except for one man out of a hundred, who was allowed to keep one eye, and they were sent to Prilep in groups of a hundred, each led by a one-eyed man. The ghastly sight of this pitiful, eyeless army so horrified Samuel that he had a heart attack, fainted, and died two days later. It took four more years to conquer western Bulgaria and reduce the Serbs to vassalage; when the fighting finally ended in 1018, the whole Balkan peninsula was back under Byzantine rule.

To the conquered Bulgars, Basil showed none of the cruelty that he had inflicted on his enemies in wartime. Instead, he treated them like citizens in any other part of the Empire, so they did not try to revolt. On the Black Sea's shore, Basil conquered the Crimean city of Kerch (1016), eliminating Georgius Tzul, a Khazar warlord, and in the east, he conquered Vaspurakan, the nearest of the Armenian principalities (1022). These conquests don't look like much, compared with, say, what the Vikings conquered in the last chapter, so keep in mind that they were accomplished by a state that was older and more decadent than any of its rivals.

There was one thing left that Basil wanted, a victory in the west to match those in the north and east. His generals had achieved a small amount of success in southern Italy against the Normans and Lombards, so now plans were made to take back Sicily from the Moslems. However, Basil was sixty-seven years old, in an age when the life expectancy was only half as long, and he died before the expedition could take off (December 15, 1025).

Despite his long lifespan, Basil left no children. In fact, he never married, and except for a few affairs in his youth, he did not even show much interest in women. After he grew up, the lonely emperor dedicated himself totally to the task of making Byzantium stronger. Therefore he was succeeded by his brother Constantine VIII. Constantine had shared the throne with Basil for nearly five decades, and during that time he kept himself busy with what one scornful scribe called "the amusements of the Hippodrome, the table, the chase and games of hazard." Thus the Macedonian dynasty came full circle, producing an emperor who was a lot like the lazy wastrel Basil I had replaced.

The Kingmaker Princesses

The Macedonian dynasty continued for thirty-one more years after Basil II. Constantine VIII ruled alone for only three years (1025-28). For the next generation, he did not leave a son, but he had three daughters: Eudocia, Zoe and Theodora. Eudocia became a nun, so this is the only time we will mention her. Zoe has already been mentioned twice in this narrative, in Chapter 6 and in the first section of this chapter. After the attempted marriage between Zoe and Otto III failed, Constantine did not want to give another man a reason to see himself as the next emperor, so he did not allow his daughters to marry until he was on his deathbed. When the end approached, the man he chose for a son-in-law was Romanus III, the prefect of Constantinople and a great-grandson of Romanus I. However, Theodora refused to marry him, so Romanus was married to Zoe; at this point Romanus was sixty years old, and Zoe was fifty. Three days after the wedding, Constantine died, and the Empire passed to Romanus III and Zoe.

Realizing her mistake in not marrying Romanus, Theodora conspired against the new royal couple, until Zoe had her confined to a monastery. As emperor, Romanus wanted to be remembered as both a "philosopher king" like Marcus Aurelius, and a conquering hero like Trajan. He suffered an embarrassing defeat when fighting the Moslems near Antioch, but later succeeded in capturing the city of Edessa (1042), and he defeated a Moslem fleet in the Adriatic. However, at home he neglected Zoe and limited her spending, so Zoe seduced a handsome palace chamberlain named Michael. Their affair meant that the days of Romanus were numbered; in 1034 he was assassinated, either by poison or by drowning in a bathtub (contemporary accounts disagree on his fate). Now Michael IV became emperor and Zoe married him, to make his rise to the throne legal.

Michael IV could not be an effective ruler, because he was uneducated and suffered from epilepsy, so he had to let his brother, a eunuch named John, run most of the administration. There was also the issue of succession, because Zoe married too late in life to have any children. To solve that problem, they adopted the son of Michael's sister as their own son (the future Michael V). On the military front, Michael enjoyed some incomplete victories. In 1037 a general named George Maniaces led an expedition that recovered most of Sicily from the Moslems; he brought with him some Norman mercenaries and the celebrated Varangian Guard, led by Harald Hardrada, the future king of Norway. The Serbs and the Bulgars revolted against high taxes in 1040, and though the Serbs succeeded in breaking away, Michael led the campaign that brought the Bulgars back into line, only to drop dead soon after he returned to Constantinople (December 1041).

Michael V wanted to rule without any strings attached, so he immediately banished his uncle, John the eunuch, and four months later he also banished his stepmother Zoe. Unfortunately for him, Zoe was more popular, and a mob surrounded the palace, which did not disperse until Michael gave in to their demand, and brought back both Zoe and her sister Theodora. The next day Zoe declared Michael deposed, and though Michael fled to a monastery and took the vows of a monk, Zoe had him arrested, blinded and castrated, to make sure he would not be a threat to her again. For the next two months, the two sisters ruled jointly, until Zoe could find another husband, Constantine IX (1042-55). Constantine now became the third emperor who qualified for the crown though marriage with Zoe.

In Sicily, George Maniaces suffered defeat when other Normans (not his mercenaries) invaded the island, and all his gains were lost after he returned to Constantinople, in an unsuccessful revolt against Emperor Constantine IX (1045). To the east, Constantine conquered Ani, the last of the Armenian states, in 1045. This was not only the last conquest of Byzantium's Macedonian era, it also brought the Empire in contact with a new enemy we'll be hearing a lot from after this--the Turks.

Converted to Islam in the tenth and eleventh centuries, the Turks had a zeal for conquest which no longer existed among the Arabs. Up to this point they had not been seen away from their Central Asian home, except as slaves or employees of somebody else. Now they formed powerful military states of their own, and one of them, the Seljuk Sultanate, grew phenomenally fast. In the 1040s the Seljuk Turks conquered Iran, in 1055 Iraq. In 1048 there was a clash between the Byzantines and Turks in Armenia, followed by a truce. The Seljuk Turks were willing to keep the truce, but they had less civilized tribes under them ("Turkomans") that were unruly and did not feel bound by any agreement. When Constantine demobilized his Armenian army to save money in 1053, many Turks would see that as a green light to move west. Finally, Constantine oversaw the permanent split between the Catholic and Orthodox churches, which happened when the pope and patriarch of Constantinople excommunicated each other (1054).

Zoe died in 1050, and Constantine followed in 1055. With both of them gone, Theodora came back once more, ruling for a year and a half until she also died of old age. Like Zoe she was childless, so she picked a court favorite, a military finance minister named Michael Bringas, to succeed her as Michael VI. Because Michael was not related to Theodora by either blood or marriage, Theodora's death marks the end of the Macedonian dynasty. By this time Byzantium had squandered what strength it had on palace struggles, and as new enemies arose, namely the Normans and the Turks, the tide of Byzantine history turned--for the last time.

The Normans Go to Italy

It was in Normandy that the first important state of the second millennium A.D. arose. In Chapter 7 we saw the Vikings settle here, after making a deal with the king of France. Their descendants, the Normans, were Viking-French hybrids with extraordinary vigor in both body and mind, which made them innovative and brave. Because they had always been a minority, they were assimilated into their subjects quickly. By the eleventh century they were Christian, and nearly as French as the French themselves; now they applied their energy to make Normandy the best-run part of France.

Scandinavians had already come to southern Italy, first as old-school Viking raiders, then as members of the Varangian Guard, mercenaries in the service of the Byzantine Empire. They called southern Italy Langbarðaland, the Land of the Lombards. The first time we hear of Norman knights in the area is in 999, though they probably passed through the peninsula previously, as religious pilgrims going to and from Jerusalem. At this time Moslem raiders, attacking by sea from Spain and North Africa, were the biggest threat to Italy. The city of Salerno had bought off the Moslem raiders, also called Saracens, by promising to pay an annual tribute, but by 999 the payment was overdue, and the city was under attack by raiders demanding the payment. The prince of Salerno, Guaimar III, began to collect the tribute, and some Normans in the neighborhood called him and his subjects cowards for doing that. Then the Normans showed what should be done, by attacking and driving the Saracens away. In the process, they captured a nice load of treasure from the enemy, and a grateful Guaimar gave the Normans gifts and asked them to stay. They refused, but promised to show his gifts to their friends and relatives when they got back to Normandy, and invite them to do military service for Salerno. As a result, more Normans would come to Italy seeking their fortunes.

A number of Italian leaders wanted to recruit Norman mercenaries after they demonstrated their strength at Salerno. One was Pope Benedict VIII (1012-24), since it appeared that only the Normans could defeat the Saracens. Another was Melus of Bari, a Lombard duke. Technically Melus was a vassal of the Byzantines, and Melus thought the Normans were just the kind of force he needed to kick the Byzantines out. When Melus launched his revolt, he had his way at first, ravaging the countryside of Apulia. However, the Byzantine commander, Basil Boioannes, also had a special force, because he had requested Varangian Guards, and Emperor Basil II sent them, along with a massive number of reserve troops. The showdown between the two sides came in 1018 at Cannae, the same place where Hannibal had defeated the Romans, more than 1,200 years earlier (see Chapter 3). For the second battle of Cannae, the Normans and Lombards were routed; the Normans lost their leader, Gilbert Buatère, and Melus fled, first to the Papal State, and eventually to Germany. Still, the outcome wasn't all bad for the Normans. The Byzantines were impressed by the Normans' performance, and a year later, there was a Norman garrison stationed at the town of Troia, in the pay of the Byzantine Empire.

The next Norman to make his mark was a minor noble named Tancred d'Hauteville. In the early eleventh century, Normandy was peaceful and secure, leaving a surplus of ambitious knights, landless second sons, and other armed malcontents with little to do. Three of Tancred's sons, William, Robert and Roger, led this group to southern Italy in 1035. Here the constant skirmishes between Byzantines and Lombards offered enterprising mercenaries a great opportunity to make a fortune. As a result, the sons of Tancred would outdo their predecessors. First William served the Byzantines, in an attempt to recover Sicily from the Moslems (see above). This campaign was a failure, but William came out of it a hero; at the siege of Syracuse he spotted, charged, unhorsed and killed that city's military governor, earning for himself the nickname Bras-de-Fer (Iron Arm). Back in Italy he changed employers, and started working for the Lombards. In 1040 William seized the castle of Melfi, in the no-man's-land between the factions; two years later the Lombards rewarded him with the title Count of Apulia.

The Normans faced a tough going because the pope and the Greek-speaking subjects of Byzantine Italy didn't want the Normans to have land as well as glory. In 1053, despite their serious disagreements (this was the year before the final divorce between the Catholic and Orthodox Churches), Pope Leo IX and Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX agreed to an anti-Norman alliance. The Normans had been fighting among themselves for a bit, but when faced with expulsion from the peninsula, they joined together and struck first. Robert and another Norman adventurer, Richard of Aversa, led the force that met the pope's army and slaughtered it near the city of Civitate. The pope fled to nearby Benevento, but its citizens handed him over to the victors. Now the Normans saw him once again as their spiritual leader, rather than their enemy, so they fell on their knees and begged forgiveness for their deeds. They treated their captive with great courtesy, but held him for nine months, until he agreed to recognize Robert as king of Calabria. Five weeks after his release, the pope died a broken man.

William Bras-de-Fer had died childless in 1046, so his Apulian land and title went to Robert, now called Robert Guiscard (Robert the Cunning or Robert the Weasel). Thus, Robert was now the most powerful man in both the heel and toe of the Italian "boot." In 1060 Robert and Roger began the conquest of Byzantine Italy. This time the pope was on their side; Pope Nicholas II realized that while he couldn't get the Normans out of Italy, he could make the Normans useful by directing them against enemies of the Papacy, like Byzantium and the Moslems. To encourage them in this direction, he proclaimed that Robert was, "by the Grace of God and Saint Peter, duke of Apulia and Calabria and, with their help, hereafter of Sicily." In return, Robert acknowledged the pope as his feudal overlord. The Hauteville brothers overran the rest of Calabria in a matter of months, and in 1061 they crossed the Messina Strait with 2,000 men. However, a revolt in the recently conquered areas forced Robert to return to the mainland, leaving Roger to subjugate Sicily by himself. The Byzantine port of Bari was nearly impregnable and required a three-year siege; not until it fell in 1071 could the Normans claim to be the masters of south Italy. In the meantime Gaeta and the principality of Capua had fallen to Richard of Aversa, while Robert finished off the last Lombard states, Benevento and Salerno, in 1077.

William the Conqueror

In Chapter 7 we saw the Vikings conquer half of England in the ninth century, only to be thrown out in the tenth. Afterwards, they stayed away for thirty years. During that time, they became civilized, so when the Vikings returned, the English found them more acceptable. In 991 Olaf Tryggvason, the future king of Norway, arrived with a raiding party of 93 ships, and was resisted with inefficiency, treachery and stupidity. The English king at this time, Ethelred II (978-1016, better known as Ethelred the Unready), chose to pay the Danegeld, a ransom of 10,000 pounds of silver.(1) Three years later Olaf tried his luck again, with the king of Denmark, Sveyn Forkbeard, as his partner; together they extorted 16,000 pounds of silver from the Saxons.

England paid the second ransom after making Olaf promise that he would become a Christian and stay away for good. Olaf kept his word, but Sveyn was free to make raids of his own; in the early eleveth century he demanded, and got, a total of 60,000 pounds of silver. Nothing else Ethelred tried worked; at one point he even ordered the killing of all Danes in England. This command could not be carried out, because those Danes who had been left behind when Ethelred's ancestors overran the Danelaw were now assimilated into the English population; in fact, many people in present-day northern England can claim Scandinavian ancestry, if they care to. In 1013 Sveyn came back, this time with plans to conquer England and stay. After a few months of fighting, Ethelred fled to Normandy. Sveyn died shortly after that, and a two-year war followed, in which Sveyn's son, Canute (also spelled Cnut), triumphed against both Ethelred and his son, Edmund II. As a result, from 1018 to 1035 Canute ruled both Denmark and England, and took tribute from Scotland; in 1028 he conquered Norway, too. He was one of England's best kings, and did well because he kept himself popular among the English, knowing that he didn't have the resources to hold his empire together by force.(2) This is shown in the fact that only seven years after his death, his sons lost control of England, and a pious son of Ethelred, Edward the Confessor, returned and took the crown.

In Normandy, the descendants of Rollo the Viking enlarged and strengthened their fief skillfully, for more than a hundred years. Then in 1035 a dynastic crisis undid much of their work. The heirless Duke Robert made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and died on the way back. He had no legitimate children, but he had an illegitimate son named William; Robert had decreed that William would become his successor should he not return. But William the Bastard was a child, so he had to fight doubly hard to keep the fief which now passed to him. Like Otto the Great and Pepin the Short, he found in the Church the ally he needed. He won the enthusiastic support of the clergy by promoting reforms and building new churches and monasteries, and in return they raised a body of knights and footsoldiers, to beat down the unruly vassals and man the castles located on strategic points throughout Normandy.

It took two decades for William to complete the job. Because he had worked so hard to build up his army, William would not let it wither away when he finally had peace in the realm. The question was, when and where would he use it? The answer came in 1066, when Edward the Confessor died childless. There was a distant relative eligible to be crowned, a great-grandson of Ethelred the Unready named Edgar, but he was only fifteen years years old. The Anglo-Saxon forerunner to Parliament, the Witan, simply ignored Edgar and elected one of its own, Harold Godwinson. They crowned Harold in the church Edward had built, Westminster Abbey, only hours after the dead king had been buried there.

At once others announced their claims to the English throne. One of them was William, who was also related to Edward; in fact, the Normans claimed that Edward had named William as his heir in 1051. Another was Norway's Harald Hardrada, successor to Canute's broken kingdom. A seven-foot-tall giant with a fearsome reputation, Hardrada didn't try to act like a civilized Scandinavian king; he preferred to be the last of the old-fashioned Vikings that had dominated the scene in the previous chapter. To give one example, he was a Christian, like most eleventh-century European kings, but whereas his predecessors tolerated their subjects who remained pagan, Harald pushed the creed aggressively, and killed those who didn't want to convert. To supply the Norwegian Church with clergymen, Harald brought them in from Russia and Byzantium, the countries where he had lived before becoming king, so when the Catholic and Orthodox Churches split in 1054, Norway almost went with the Orthodox Christians of the East.

The last important player was Harold's brother, Tostig, the earl of Northumbria. He had a falling-out with Harold a year earlier, when his subjects revolted and ran him off his land, and Harold did not help him. Elsewhere in this narrative we see nobles become disloyal when they don't get their way, so Tostig contacted Hardrada, asking him if he was still interested in becoming king of England.

Meanwhile to the south, William began to earn the title of "the Conqueror" around the town of St. Valery, on the French coast of the English Channel. Here in September he assembled seven hundred ships and 7,000 men. With the army came many of the men who would take over key positions in the church and government of England, feudalize the nation from top to bottom, and make it a more efficient state. To reduce the chance of some opportunistic lord invading Normandy while he was away, William invited all knights from the territories around Normandy to join him, offering them a share of the loot, land and titles if they came and the expedition succeeded; he also got the pope's blessing on the expedition. On September 27, the tide and winds turned in the invaders' favor, and they set sail for England.

Those winds helped to decide the outcome of this three-sided struggle. The steady north wind that delayed William's crossing of the Channel allowed Harald Hardrada to make the first move. The Norse crossed the North Sea with 200 longships and 1,800 men, landed in northeast England, burned the town of Scarborough, and advanced on York. King Harold immediately mobilized his forces and marched north, covering a staggering 180 miles in four days before he reached the invaders. The Vikings were at Stamford Bridge, expecting to meet negotiators who would discuss the surrender of York, so they were caught by surprise; many of them weren't wearing their armor when attacked. It was a massacre, but not a quick one; these were Vikings after all, and they fought back fiercely all day before Harold and his men finally prevailed.(3) Hardrada and Tostig were both slain, and Harold kept a promise he had made earlier in the day--he would only give the Norse king enough land for a burial plot. However, this also meant that nobody was minding the Channel; William made his crossing and landed at Pevensey without losing a single man.

Harold heard about the Norman landing quickly enough, and led his men back to the south in a series of forced marches. They arrived in Sussex on the night of October 13. The two armies were almost evenly matched; each side had 7,000 men, of which 2,000 were elite warriors in chainmail. The other five thousand in each army were an assortment of archers and footsoldiers. The Anglo-Saxons wore long hair and mustaches, but the Normans cut their hair so short that many people in Sussex thought an army of monks had invaded them. The most important difference was that the Normans had more horses, and that they had learned to fight on horseback, like French knights, while the English preferred to fight Viking-style (on foot).

The battle of Hastings (October 14, 1066) began with Harold and his men holding a hill. Because they were on their home ground, in a good defensive position, Harold's advisors recommended avoiding a direct conflict until the men plundered the surrounding countryside, thereby keeping fresh supplies from the invaders; in a long war, they reasoned, the Normans could only get weaker. Harold proudly refused to do this, and both he and William--each for their own reasons--decided to fight immediately. William divided his force into three divisions (Bretons on the left, Normans in the center, and French and Flemish on the right); Harold chose a phalanx formation, with a shield wall in front, and his men arranged ten ranks deep. For most of the day William was unable to break through this shield wall; in fact his army nearly panicked when a false rumor spread that William had been slain already. Then William got the idea of having his knights stage a mock retreat, and the Saxons pursued them to the low ground. That was the decisive moment of the battle; on the plain the Norman knights had the mobility advantage, and were able to break up and isolate the Saxon units. William got his bowmen to help by ordering them to arch their shots, so that the arrows fell on their targets from above, instead of harmlessly hitting the Saxon shields. Harold perished, and with him went Anglo-Saxon England. Today's Britons remember 1066 as the most important date of their history. Before 1066 England was one of the most backward countries in Europe; thanks to William's reforms after the conquest, it has been one of Europe's most advanced nations since that time.

For William the most dangerous part of the conquest ended with the battle of Hastings, but another five years were required to bring all of England under his authority. First he captured the ports along England's southeast coast, allowing reinforcements to come in. Meanwhile in London, Edgar, the previously overlooked teenage prince, was crowned when news arrived of Harold's death. London was too big to take in a single charge, so William surrounded and isolated the city. In late December the local earls and the archbishops of Canterbury and York surrendered the kingdom; Edgar was exiled and William was crowned. In truth, however, he still only had the southeast quarter of England. The most serious challenge came from the northeast, where the people were still largely ethnic Scandinavians and some Danish invaders landed there, using the war as an excuse to do some pillaging. William ended up bribing the current Danish king, Sveyn II, to make Denmark stop supporting revolts in northern England.

The last resistance to William's rule came from the Isle of Ely. This was not a real island but an area in the northeast, surrounded by swamps called the Fens; like Ravenna in Dark Age Italy, Ely was easy to defend because of the wetlands. Here the local leader was one Hereward the Wake, a Saxon noble who had been in revolt against the king even before 1066. Going into exile, Hereward returned in 1069 to find his father and brother slain, and his land confiscated, so he joined the anti-Norman opposition at once. The Normans first tried to take Ely with a frontal assault, by building a mile-long wooden causeway across the Fens, but it sank under the weight of armored men and horses; archaeologists have found skeletons wearing chainmail in the Fens, showing that some knights drowned when the causeway collapsed. The Normans then tried a tactic that only made sense because this was the Middle Ages--they built a wooden tower and put a witch on it to curse Ely's defenders! When the witch got done with the black magic, she "mooned" the Saxons, and one of them took advantage of the moment to shoot an arrow at her "target"--ouch! Some more arrows were shot, and these were flaming arrows, which brought down both the tower and the witch. Finally, one of the knights bribed the monks of Ely to show them a safe path across the Fens, once the Normans agreed to spare the local abbey. Ely was captured, but Hereward escaped with a few followers. The only Norman record mentioning Hereward is the Domesday Book (see below), so it looks like he and William made peace, after William restored his land to him. Next, King Malcolm of Scotland tried his luck by invading the northernmost counties, getting as far as Jarrow before William arrived and forced him to acknowledge his supremacy in England (1070-72).

After the fighting ended, William chose to spend most of the years remaining to him in his native Normandy, leaving his administrators (mostly clergymen, of course) behind to run the day-to-day affairs of the new territory. However, he did not get to enjoy a quiet reign. He had to return to England in 1075 to put down a revolt, led by the earls of Hereford and Norfolk, and once more in 1085 to deal with a final Danish invasion. On top of that, his eldest son, Robert, staged some uprisings because he resented his father's refusal to let him take an active part in running Normandy (the Norman homeland had technically been handed over to him in 1066). This was a serious enough threat that William shipped units of the English militia, called the Fyrd, to France to fight alongside the loyalist barons and knights.

The Norman Kingdoms

The feudal system that had characterized Europe since the fall of Rome began to decline around 1000, because some regions had become wealthy enough to afford a limited return to centralized government. The two Norman kingdoms led the way, the Norman genius being assisted by the previous history of the lands they conquered. In England, the Celto-Roman residents had mostly been exterminated by the slow Anglo-Saxon advance, and the land resettled by immigrants from Germany. The result was a society much like that of primitive Germany, and though later influences from the Continent caused a superficial feudalization, it never changed everything the way it did in France (e.g., the witan remained as the king's council of advisors and a check on his power). Being few in number, once the Normans conquered England, they realized they could only hold their prize if they observed a strict military discipline. Thus, William I set up a centralized government that looked like feudalism but made him the effective authority throughout the land. Southern Italy had been Byzantine before Robert Guiscard seized it, so it was easy for him to revive the machinery of autocracy, but like William he covered it with feudal terminology.

The small size of these kingdoms made it easy for the king to personally oversee many day-to-day functions. They did not strain the simple communications of the times, and showed that, on a small scale at least, the new method of government was both economical and efficient. As the national income of the West continued to rise and money became a common part of everyday life, the defiencies of feudalism became more obvious. It became harder to bear with the personal eccentricities of each noble, to deal with problems it was too inflexible to handle, and to counter its basic lawlessness. The merchants and the peasants found an ally in the king, who, by hairsplitting insistence on his feudal rights and by reviving decayed precedent, could either cut down the power of the insubordinate landholders or drive them to a revolt in which they could be destroyed. Royal propaganda encouraged loyalty to one's nation first and loyalty to one's lord second; that appealed to the memory of Roman greatness and Roman government by law. But even at the end of the Middle Ages the size of the area that could be governed in such a way was strictly limited. France corresponded to the maximum. The German (Holy Roman) Empire was well above it and ultimately the centrifugal forces of the landholders split it into a puzzle of big and little fiefs whose histories of devouring and dividing went on until the mid-nineteenth century.

It was in William's England that the first modern-style nation-state came into being, one with a centralized administration that ran the kingdom by law rather than by custom. William began the transformation by demanding an oath of fealty from every Anglo-Saxon lord; those who refused had their lands confiscated. Then William divided those landholdings into fiefs small enough to discourage future opposition, and gave them to the Norman knights who crossed the Channel with him. On the western frontier he inherited a problem with the Welsh (Harold had fought a war with Gruffydd ap Llewellyn, king of Gwynedd, from 1062 to 1064), and though the Normans invaded Wales in 1068 and 1100, they never succeeded in conquering more than a third of the region. In the end William allowed three Welsh kingdoms to remain (Gwynedd, Powys and Deheubarth), and granted extensive powers to the nobles on the border, making them "lords of the marches," to keep the Welsh from raiding England.

To control the local clergy, he appointed Lanfranc, an Italian cleric and scholar, as Archbishop of Canterbury; despite his nationality, Lanfranc cooperated with William in keeping the English church independent of the pope. And though William allowed the existing shires (counties) to run local affairs the way they had done in Anglo-Saxon times, he set over them a central administrative council called the Curia Regis (King's Council), made his vassals and bishops members of it, and used it to carry out his decrees, keep the country's accounts and resolve any dispute that concerned the crown.

On a midwinter day in 1085, William donned his crown and called the court to a solemn assembly in which he announced that, for purposes of taxation, he would hold an inquest of all England. During the following year the king's barons, legates and justices traveled all across the kingdom to learn the extent and value of every estate in the country; they were also on the lookout for any Norman nobles who had occupied lands reserved for the king. Wherever they went sheriffs and other local authorities came forth to answer the questions of the visitors and to testify that everything they recorded was true. As one medieval chronicler put it, "So minutely did [William] cause the survey to be made, that there was not one hide nor yard of land, nor even . . . was there an ox, cow, or swine that was not set down in the writ."

It's a safe bet that the survey was accurate, because the king's men threatened the usual horrible medieval punishments (e.g., death and dismemberment, not always in that order) if anyone refused to cooperate, or if they lied about what they owned. And you thought an audit by the Internal Revenue Service was bad news! Anyway, scribes organized the data and put it all into two bulky volumes, called the Domesday (Doomsday) Book because they thought it would be the last word on census-taking. Copies still exist today, and it serves as an invaluable source of information about late 11th-century England, one that is complete almost to the last animal.

William did not see the Domesday Book in its final form. While the king rode through the burning ruins of Mantes, a French town he had attacked, his horse stepped on a burning ember and threw him against the pommel of his saddle. He died of the resulting internal injuries in Rouen on September 9, 1087.

William's court planned to bury him in St. Stephen's, an abbey he had built in the Norman town of Caen. But the funeral service was interrupted by a certain Ascelin, who laid claim to the church because William had taken from him by force the land it was built on. An inquiry was conducted, and sure enough, the land did belong to Ascelin. Since Ascelin would not allow the Conqueror to be buried on his property, the clergy purchased the land so it could proceed with William's funeral. In the next century this squabble would prompt Master Wace, an Anglo-Norman poet, to write the following: "All marveled that this great king, who had conquered so much and won so many cities and so many fine castles, could not call so much land as his body might lie in after his death."

The dispute over William's burial place was not the only humiliation he suffered after death. William had grown fat in his last years, and his body became further bloated during the time it took to transport it to Caen, until it could not fit into the stone sarcophagus meant for it. At the funeral, a group of bishops forced the body into the sarcophagus anyway, and it burst, releasing a foul stench that caused many attendants to run out of the church. What a way to end a career!

William had three sons to divide the inheritance. The eldest, Robert, became Duke of Normandy. He also wanted England, but was more interested in eating than in fighting; one contemporary observer described him with these words: "Belching from daily excess, he came hiccuping to war." England went to the ruddy and obnoxious second son, William II (also called William Rufus). The third son, Henry I (also called Henry Beauclerc), got two and a half tons of silver and had all the bad qualities of his brothers.

When Lanfranc died in 1089, William II had all churches celebrate, and waited two years to appoint a successor, collecting the archbishop's salary in the meantime. In 1091 he invaded Normandy and took Robert's land, but before the year was up, illness forced him to return to England. William got a second chance in 1096, when Robert went on the First Crusade and sold Normandy to raise funds for the expedition. However, William then died in a hunting accident (1100), so the whole kingdom went by default to the landless brother, Henry I, who seized the royal treasury and had himself crowned king at Westminster. To unite the Saxon, Scottish and Norman royal families, Henry married Matilda of Scotland, the daughter of Scotland's King Malcolm II and his Anglo-Saxon queen Margaret. Henry might have enjoyed a peaceful reign if Robert never came back from the crusade, but in 1101 Robert returned and staged an unsuccessful invasion of England. Five years later Henry struck back; at the battle of Tinchebray in France (1106), Robert was defeated and exiled to Wales; now Normandy and Calais became permanent parts of Henry's domain.

Henry I's greatest accomplishment was the development of the Curia Regis into two separate bodies: one to handle judicial matters, the other financial ones. Henry sent members of the judicial branch across the land to try disputes where they arose, rather than bring them to the king's court; these were the forerunners to the circuit judges of today. The financial branch arose because most of the barons knew little about money, were bored or baffled by record-keeping and math, and stayed away when there was paperwork to be done. Those who stayed and got the work done became a corps of professional accountants. At first they did their tallying on a checkered tablecloth, and from that we get the name of the Exchequer, England's royal treasury. To hire more competent accountants the king stopped looking for men from noble families and took whoever had the training, irregardless of their background. He paid them with coins, instead of the usual grants of land, and thus was born the first civil service the West had seen since the fall of Rome.

In Italy, Robert Guiscard went to help his brother in Sicily, once the Byzantines had been driven from the mainland. Together Robert and Roger captured Palermo, the Sicilian capital, in 1071. Then Robert got another idea to match his ambitions--could he take Constantinople itself? He decided to try it; in 1081 he crossed the Adriatic with an army, captured Corfu and Durazzo, and defeated a Byzantine force led by the emperor. Before he could proceed to the imperial capital, though, Byzantine agents launched more revolts in Apulia, forcing the Normans to go home. In 1085 Robert made one more attempt to march east, only to fall victim to the same typhoid epidemic that killed many of his men.

Robert's son, Roger Borsa, inherited Calabria and Apulia, while Robert's brother Roger became duke of Sicily. Sicily was still a Moslem emirate, so it took a long time for Roger to secure his inheritance; he took Syracuse in 1086, and Malta in 1090. Finally in 1091 he eliminated the last Moslem opposition. Once he finished, he proved to be the most diplomatic member of his family. Recognizing that he needed religious tolerance to keep his state together, he made Arabic one of the official languages of his court, left some Moslem governors in their posts, and allowed Islamic courts to remain in session. Thus Roger became known as the Great Count, one of the wisest rulers in Europe; French, German and Hungarian kings all wanted a political marriage with his family. This is all the more amazing because Robert Guiscard's eldest son, Count Bohemond, was a leader in exactly the opposite type of enterprise--the First Crusade. Bohemond captured the city of Antioch in 1098, founding a Crusader state that would last for 170 years.

Roger died in 1101. He was succeeded first by a son named Simon, then by another son named Roger II (1105-54). His reign saw the consolidation of Norman power in south Italy. He took Calabria in 1122, and when William II, the son of Roger Borsa, died in 1127, Roger II annexed Apulia; three years later he proclaimed himself a king. Then he and captured the rival Norman state of Gaeta (1137), and finished by taking the independent cities of Amalfi (1137) and Naples (1139). In 1146 he even crossed the sea and captured Tripoli, establishing the only Norman colony in Africa. His court at Palermo, with its black servants, Saracen guards, harem and pleasure-domes, became the scandal and envy of Christendom.

Thus, by the mid-twelfth century the Normans had gained for themselves a widely scattered empire, in England, Italy and Syria. As the best knights in Europe, they excelled in fighting and castle-building. However, their main role was to be the catalysts of medieval culture. They invented almost nothing on their own, but instead learned architecture, tactics and the techniques of government from others. Once they had improved on all of these things, and changed the face of Europe, they faded away. By 1200 they were no longer a distinct people, and their kingdoms were in the hands of their former students.

The Papal Investiture Controversy

In theory the Holy Roman Empire was an elective monarchy, so any duke within it could become emperor. In practice, there was an election whenever the throne became vacant, but each emperor usually came from the same family as his predecessor. Still, the emperors had to play the politicians' game to get elected, making promises and concessions to get the dukes to vote for them, which weakened their real power.

During its period as a united state, the Holy Roman Empire had three dynasties ruling it: the Saxons (962-1024), the Salians (1024-1125), and the Hohenstaufens (1125-1250). As we saw in the previous chapter, the Saxon emperors spent their time driving back the Viking and Magyar invaders, and showing their rowdy dukes who was boss.

The Salians came from the central duchy of Franconia. Their first emperor, Conrad II (1024-39), was a distant relative of the Saxons, descended from Henry the Fowler, but not from the emperors who followed him. He conquered Burgundy in 1033, so the Empire was sometimes called a trias, or tripartite state, afterwards (Germany + Italy + Burgundy). Conrad also took the offensive against the barbarians, beginning a drive to the east called the drang nach osten. During the Dark Ages, the Elbe River had marked the eastern limit of the Germans. The lands between the Elbe and the Oder, modern East Germany, were populated by still-pagan Slavic tribes, like the Sorbs and the Wends; Poland conquered the southern part of this area (Lusatia and Milzen) in the first years of the eleventh century. Conrad retook Lusatia and Milzen in 1031; his only setbacks were the surrender of his northernmost province, the March of Schleswig, to Denmark's Canute the Great (1025), and a border adjustment in Hungary's favor (1031). Henceforth the Germans would look east for living space, and the drang nach osten would be a key element of German foreign policy until their total defeat in World War II.

Charlemagne and the Holy Roman emperors were quite aware that their nation would die with them unless the conqueror became an administrator. Most medieval kings hired clerics to do administrative work, because these were the best-educated folks they could find, but the Germans did more than that; they made barons out of the bishops. When Emperor Otto II led an army into Italy in 981, 70 percent of the soldiers came from clerical vassals. In the Empire, church and state acted as one.

At the same time the emperors encouraged reform in the German Church, for the Cluniacs had shown how such a movement could make people more law-abiding. Soon the emperor and his bishops were cooperating in raising the nation from savagery, rekindling the piety of brutalized clerics, and deploring the frequent breaking of their vows. Respect for peace grew with the success of this repair, and the bishops became pillars of the new order.

The Papacy took longer to recover than the rest of the Church did. It hit bottom in 1033, when the Tuscans, a family of Italian nobles, elected a twelve-year-old to serve as pope. This pope, Benedict IX, built up an incredible track record of sin, which included bisexuality, bestiality, witchcraft and Satanism. He was so bad, in fact, that in 1044 the Crescenzio family, rivals of the Tuscans, drove him out and set up their own pope, Sylvester III. However, in the following year Benedict returned to Rome and took back his office. Before the year was over he grew tired of being pope and sold the title to his godfather, who now became Pope Gregory VI, for a thousand pounds of silver. This shameful transaction caused such an outcry that Benedict changed his mind and refused to surrender the job he had just sold. Sylvester and Gregory would not step down either, so now there were three popes.

It was the current German emperor, Henry III, who rescued the Papacy from this mess. In 1046, at the urging of the Cluniacs, he called for a synod which declared both Sylvester III and Gregory VI removed from office; a second synod deposed Benedict IX. He went on to appoint the next three popes, each time choosing a German clergyman who was both competent and pious. The third of these popes, Leo IX (1049-54), reorganized the College of Cardinals. Previously all the cardinals had been Romans, representing the corrupt ruling families of central Italy, so Leo replaced them with Cluniacs from anywhere in western Europe, thereby surrounding himself with advisors who were more trustworthy and favored reform. Then he worked to cleanse the Church of evils like simony and clerical marriage.

Unfortunately, the good relationship between the emperor and the pope cooled in the mid-eleventh century. Again they disagreed on the issue of who was Christendom's supreme leader. This had been brought up in the ninth century, but then both Empire and Papacy collapsed before they could fight over the matter. The emperor felt he had to be in charge, because the imperial crown declared him to be Christendom's champion in western Europe, though in reality the Empire was never much more than a state for Germans run by Germans. And because the Church saw itself as an international organization, it could not tie itself to any secular authority. Previously, Papal leadership had tended to be passive, acting as the ultimate court of appeal for Church matters, but making no move unless appealed to; Gregory the Great (590-604) was the classic exception to this rule. Now came several aggressive popes; under them Rome actively interfered in politics, no longer passing up any opportunity to increase the power/authority of the Church.

The first phase of this incredibly rapid rejuvenation was an 1059 decree ending lay investiture--no layman, not even a king, would be allowed to appoint bishops or popes anymore. By limiting voting rights to the cardinals, the Papacy kept its elections from being hijacked by the Roman mob. However, it also denied the Holy Roman Emperor any say in the matter, making the pope independent of the state. The author of this decree was Hildebrand, a Tuscan prelate, and he also promoted the idea that a true priest should not marry, but give his affections and loyalty to the Church alone, unencumbered by duties to either family or country. Hildebrand got away with this because Emperor Henry IV was a minor. Lack of opposition encouraged him and the current pope to try something more daring--why stop at making the Church free from state control when it could become a Church that controlled the state?

Hildebrand became Pope Gregory VII in 1073. At his first council a year later he made celibacy mandatory, forcing married priests to get divorces (many ex-wives, now abandoned and broke, subsequently committed suicide). Then he made his views on investiture the official position of the Church; to promote this, he re-publicized The Donation of Constantine (See Chapter 7). This was a claim over the whole Empire, making conflict inevitable. He had one advantage to offset his lack of an army: the Empire's government couldn't run without the German Church. If the emperor was deprived of any say in the appointment of bishops and if their allegiance was to the Papacy alone, the secular power would wither and become merely the ornament of a theocracy, with clergymen immune from taxes, laws, and all other secular obligations.

Henry IV denounced Papal imperialism when he grew up. Simony suited him fine, and he detested papal interference in the selection of those he called "his" bishops. The first round of the contest began when Henry declared Gregory VII deposed ("no longer pope, but false monk" was how he put it in a letter to a group of German bishops). The pope responded by deposing the emperor's bishops, and then by excommunicating the emperor. This was a powerful punishment, for the princes and dukes of the Empire were only inclined to support the emperor when it suited their own interests; the pope's declaration of the emperor as an enemy of the Church was a call to give the crown to somebody else. The result was a resounding Papal victory, with the emperor doing public penance, standing barefoot in the snow, wearing the garb of a humble pilgrim, for three days at the doorstep of the fortress of Canossa, waiting for the pope to let him in and forgive him (1077). Gregory kept him waiting because this was completely unexpected--he thought Henry was coming with an army--until the owner of the castle, the Countess Matilda (who also happened to be the pope's current mistress), and Hugh, the abbot of Cluny, persuaded him to pardon the contrite ruler. Ever since that time the phrase "going to Canossa" has signified total humiliation.

Henry knuckled under to the pope because the nobles of Germany had already elected an emperor of their own, Rudolf of Swabia, the first of the famous Hapsburg monarchs. Once the pope revoked the excommunication Henry went home to crush the revolt; then he took back his concessions to the Papacy, declared the pope deposed again, and carried his own candidate, the "anti-pope" Clement III, to Rome by force of arms. The real pope was surrounded in Castel Sant' Angelo (Hadrian's mausoleum, see Chapter 6, footnote #23), and he called on Robert Guiscard, who had just returned from his unsuccessful march on Constantinople, to save him. The Normans drove Henry from Rome, reducing a third of the city to ashes in the process, but because Gregory was very unpopular with the Romans, Robert took him to Monte Cassino.(4) There he died in 1085; Gregory's final words were, "I have loved righteousness and hated iniquity; therefore I die in exile."

The struggle went on for half a century, for the imperial army was too often needed elsewhere to keep a permanent garrison in Rome. The emperor couldn't afford to give way on either the leadership or the investiture issues, because the German bishops were the pillars of the Empire. The popes, swept up by Gregory VII's intoxicating ideas, found it difficult to compromise even on secular matters. The emperors regularly invaded Italy, to place their candidates on the throne of St. Peter, and the Romans just as regularly threw them out and invited the real popes back after the emperors went home. The rival emperors crowned by the popes likewise didn't last any longer than the real emperor's "anti-popes"; all they did was cause confusion. Most Europeans chose to recognize the emperor but not his puppet pope, and the pope but not his puppet emperor. Finally in 1122 Henry V (Henry IV's son), and Pope Callistus II reached a compromise; frightened by the growing lawlessness their civil war was causing, they agreed to abandon their puppets and to allow the emperor to approve the pope's appointment of the bishops before they took office. It was an uneasy peace, though, and in the long struggle of the northern Italian towns for independence, the pope found willing allies against the emperor. Because they were princes in their own right, and usually Italian, the popes had a knee-jerk reaction against a power that was secular, imperial, and foreign to the peninsula. Moreover, the Empire was weakening, even on the north side of the Alps, so the popes found that their opponent was a groggy giant. They probably knew that allowing the disintegration of the Empire could expose the Papacy to harsher winds (it happened when they broke with Constantinople a few centuries earlier), but every pope who rocked its creaking structure came out looking like an Italian patriot.

El Cid and the Reconquest

As the second millennium A.D. began, the Caliphate of Cordova never looked stronger, but it disintegrated completely in a single generation. The trouble started when Moslem Spain's conquering vizier, Muhammad ibn Abu ‘Amir al-Mansur, went forth once more, this time to subdue the Christian rebels in the county of Castile. Near Calatanazar in 1001, he encountered a Christian force that was too large for even him to handle, forcing a withdrawal. He died a year later, and his son Abdulmalik-al-Muzaffar succeeded him as vizier. However, the son only held the post for two years before he also died (1004), and a younger brother, Sanjul, went a step further than the rest of the family, coercing the caliph, Hisham II, to declare him his heir.

This was too much for the caliph's Berber mercenaries, who revolted. Hisham abdicated in 1009, and two distant relatives, Muhammad II Mahdi (Hisham's choice) and Sulayman al-Mustain (the Berbers' candidate), fought for the throne; Sanjul was murdered in the same year. With some help from Count Sancho Garces of Castile, the Berbers defeated the "Arabs," looted Cordova and installed Sulayman as caliph. Muhammad made a comeback, though; he allied himself with Barcelona's Count Ramon Borrell I, and in 1010 a second Christian-Moslem army marched on Cordova. This time the city was burned down; Abd-al-Rahman's great palace was sacked and destroyed, barely fifty years after its completion. Before the year was over, Muhammad was assassinated, and Hisham returned to rule a second time. But not for long; he was forced to abdicate again in 1013. Next Sulayman got to rule for three more years, and in the increasing chaos, the throne changed hands several times between the Umayyad and Hammudid families. Meanwhile the governors of cities like Seville, Granada, Badajoz, Valencia, Toledo, and Saragossa declared independence from what they saw as the Cordova dictatorship. In 1031 the last Ummayad, Hisham III, stepped down, and the caliphate was no more.

Two dozen petty emirs of "Arab" and Berber ancestry now divided Moslem Spain between themselves; today we call them the Reyes de Taifas ("partisan kings"). They avoided Christian conquest simply because the Christians were almost as divided as they were. The overall picture becomes very difficult to follow, with Christians serving as mercenaries in Moslem armies, Christian-Moslem alliances, Christians fighting Christians, Moslems fighting Moslems, and occasionally a proper Christian-Moslem war. It's not much clearer in the Christian states, where by 1000 the royal families of Leon, Castile and Navarre were united by marriage, with simultaneous or alternating reigns of rival cousins or in-laws. Eventually Navarre's greatest ruler, Sancho III (1000-35), rose to the top; when he died, his kingdom was split between three sons: Garcia IV in Navarre, Ramiro I in Aragon, and Ferdinand I in Castile.(5). As a result, every Christian king in Spain since 1037 has been a descendant of Sancho III.

In the increasing chaos, a Jew rose to command the army of one of the Moslem states, something that would have been unthinkable in other times. This was Samuel ibn Naghrela (993-1056), who fled Cordova when the Berbers took the city in 1013. For a while he ran a spice shop in Malaga, but eventually he moved to Granada, where he was first tax collector, then a secretary, and finally an assistant vizier to the Berber king Habbus al-Muzaffar. When Habbus died in 1038, Naghrela made sure that his son Badis succeeded him. In return, Badis made Naghrela his vizier and top general, two posts which he held for the next seventeen years. Naghrela's son Joseph inherited those jobs, but apparently it went to his head (he was only twenty years old), for he was arrogant as well as talented. Moslems accused Joseph of using his office to benefit Jewish friends, assassinated him, and launched a massacre of Granada's Jews the next day (December 31, 1066). Today's Jews remember 1066 for this, rather than for the Norman conquest of England; it was one of the first signs that the good times they enjoyed in Moslem Spain weren't going to last.

It is at this point that the most famous figure of the Reconquest enters the picture. His name was Rodrigo Diaz de Vivar, but he is better known as El Cid, after the Arabic Sayyid, meaning lord. Born to a poor noble in 1043, he was given the customary education of a warrior, and sent to King Ferdinand I of Castile and León to complete his knightly training. He fought in his first battle in 1057, when Castile defeated Saragossa and made its Moslem emir a vassal. Between wars Rodrigo acted like any good knight, and looked for acts of bravery and charity to perform. According to one story, at an uncertain date he helped a ragged leper on the road to León who turned out to be Saint Lazarus in disguise; Lazarus promised Rodrigo that in return for his charity he would win a great victory after his death.

There was a petty war between Castile and Aragon in 1063, and during the battle of Graus, Rodrigo slew Aragon's finest warrior in single combat. For this, he was promoted to commander in chief of the Castilian army and given the additional title of Campeador--Champion. Two years later Ferdinand I died (1065), and before his death he gave orders to have his realm, like that of his father, divided three ways, so that each son could have a piece: Sancho the Strong got Castile, Alfonso got León, and García got Galicia. Rodrigo found himself leading Sancho's army. Sancho conquered the Moslem city of Badajoz, but as the eldest son, he felt it would be nicer to have the inheritances of his brothers. First he teamed up with Alfonso; together they deposed García and put him in a monastery. Then Sancho turned against Alfonso, by declaring he would annex both León and Galicia, but while he was besieging Zamora, one of Alfonso's cities, he was suddenly murdered (1072). Because Sancho was childless and Alfonso was the only brother left, the latter proclaimed himself King Alfonso VI of Castile and León.

Many suspected Alfonso of ordering Sancho's assassination; Rodrigo was one of them. According to the legend of El Cid, he and twelve of his friends took Alfonso to the church of Burgos, and made him swear several times on holy relics that he had nothing to do with his brother's death. This oath convinced Rodrigo, and he pledged allegiance to the new king, but Alfonso understandably did not care to have henchmen of the late Sancho around, especially one who had just humiliated him. Therefore Alfonso demoted Rodrigo, and gave his job to a rival, Count García Ordóñez. Meanwhile Aragon annexed Navarre in 1076, so in just four years the number of Christian kingdoms in Spain was reduced from six to three (Castile-León, Aragon and Barcelona).

In 1079 Ordóñez was sent to Granada, to collect tribute owed to Castile. While there, the local emir asked for Castilian troops to join him in a campaign against Seville. The Granadans and Castilians marched together, but unfortunately for them, Rodrigo was in Seville at the time, serving as Castilian ambassador to that city. Never one to shy away from a good fight, Rodrigo took charge of Seville's army, and though the invading force was larger, he defeated it. He probably thought he was defending another vassal of Castile, but Alfonso wouldn't stand for this kind of behavior, so he exiled Rodrigo and three hundred of his followers from the kingdom.

Rodrigo and his knights spent the next few years as soldiers of fortune, looking for a ruler who would hire them. First they offered their services to the count of Barcelona, but he wasn't interested, so next they went to the emir of Saragossa, and accepted a job offer from him. They successfully defended Saragossa from both Moslem and Christian attackers, but elsewhere the confidence of Christians was growing, and that of the Moors was shrinking. By now one third of the Iberian peninsula was in Christian hands. Resuming the Reconquista, Alfonso pushed south and captured Toledo, the former Visigoth capital (1085). For the Moors this was a major loss, for three reasons:

- It was the largest city captured so far by Spanish Christians.

- Its rulers, the Dhunnunids, were the first Moslem dynasty in Spain to be deposed by Christians (until now, all Moslem rulers had been brought down by other Moslems).

- Toledo's excellent location in the center of the Iberian peninsula put all Moslem states within reach of Christian armies.

The Almoravid leader, Yusuf ibn Tashfin, invaded Spain with a Berber army and destroyed Alfonso's army at the battle of Sagrajas in 1086; Alfonso and a handful of his men barely escaped with their lives. Many Christians declared that if El Cid had been fighting on Alfonso's side the outcome would have been different, so the humbled king invited El Cid to return from exile. Meanwhile, ibn Tashfin went back to Morocco with most of his army (which was a great relief to the Spanish Moslems!), leaving behind three thousand of his dreaded "Holy Ones" to support the king of Seville. Perhaps because of this, once the kingdom was safe, Alfonso recovered his pride, and in 1089 he banished El Cid again.

Once again a mercenary, El Cid went southeast, and in various campaigns he defeated Moslem princes, the count of Barcelona and the king of Aragon; finally he became master of the Moslem city of Valencia (1094). While he was doing that, Alfonso resumed his attack on the Moors. Again the Moors called on the Holy Ones for aid, and ibn Tashfin brought another army to Spain. What was different was that this time the Almoravids came to stay; they easily brushed aside the Christians and conquered all but four of the Moslem states--one of which was El Cid's Valencia. Valencia successfully defended itself from the first Almoravid attack, and from a second attack in 1097.

A statue of El Cid in Spain.

On July 10, 1099, El Cid died peacefully in bed. Because he was the only Christian who could beat them, the Almoravids immediately launched another attack on Valencia. It look like Valencia would fall quickly, and the Holy Ones took no prisoners. The only sensible thing the people of Valencia could do was escape before the Almoravids broke through the city walls. According to legend, El Cid's wife came up with a way to do that. She ordered her husband's dead body dressed in armor and mounted on his horse, so it could lead a charge from the city. The corpse stayed upright in the saddle because it was stiff from rigor mortis, and this restored the morale of El Cid's men, who thought their master had come back to life to lead them once more. The Holy Ones, on the other hand, fled from the sally in terror; even when El Cid was dead, they did not want to fight him! Thus, the prophecy of Lazarus was fulfilled.(6)

The Almoravid arrival delayed the end of al-Andalus for four hundred years. By 1115 they had subdued the last of the other Moslem states, but then the newcomers succumbed to the luxury of life in Spain. In 1093 Henry, the son of the duke of Burgundy, came to the aid of Alfonso VI against a Moorish invasion; Alfonso rewarded him by making him count of Portucale (modern Oporto), Leon's westernmost province. When Alfonso was succeded by a daughter, Urraca, in 1109, Count Henry, and later his widow, Teresa, renounced their feudal allegiance to León. Then Henry invaded León, but all he accomplished was the securing of Portucale's independence. In 1139 Henry's son, Alfonso Henriques, declared himself the first king of Portugal, Alfonso I. Four years later, through the Treaty of Zamora, King Alfonso VII of León recognized Portugal as an independent kingdom, and so did the pope in 1179. In 1147 some Norman adventurers on their way to the Second Crusade captured Lisbon for the Portuguese; this advanced Portugal's southern frontier to the Tagus River.

Likewise, the rest of Christian Spain remained divided for some time to come. Ramon Berenguer III, the count of Barcelona, acquired Provence (the eastern half of the Riviera) from Burgundy by marrying its heiress in 1112. Navarre conquered Saragossa from the Almoravids in 1118, but then Navarre and Aragon were split between two heirs of Navarre's Alfonso I in 1134. A more permanent union came with the marriage of Barcelona's Ramon Berenguer IV with Queen Petronilla of Aragon in 1137, and later Ramon Berenguer pushed southward a bit, clearing the lower Ebro valley of Moors (1148-49). His son Alfonso II (1162-96) added some fiefs on the French side of the Pyrenees--Roussillon, Montpellier (1204), Foix, Nîmes, and Béziers--but this would have the drawback of drawing his son, Peter II, into the Albigensian Crusade (see below). To the west, Castile and León split again in 1157, this time between two sons of Alfonso VII; the Christian kingdoms apparently considered their independence as important as winning the Reconquista.

The empire of the Almoravids collapsed in 1145. They were replaced by a group of puritans called the Almohads (from the Arabic al-Muwahidin, meaning "those who proclaim the unity of God"). Under them the Reconquista took a turn for the worse. The fanatical Almohads harshly persecuted their Christian and Jewish subjects, killing many and either expelling the rest or converting them at sword point. In doing so they destroyed what had made Moslem Spain a prosperous state. Previously wars had seldom been total ones; Christians and Moslems often served in the same army, and while Moslems behaved frightfully when they captured towns containing Christians, they didn't bother their Christian subjects back home. Many Christians, and even more Jews, had risen to important positions of authority under Moslem rulers; today Jews still look back on Spain in the 8th-12th centuries as a "golden age." Christian intolerance grew to match Moslem bigotry. Many of the characteristics which marked Spaniards afterwards--melancholy temperament, black humor, lack of tolerance for non-Catholics--can be traced to the brutal nature of the religious wars that followed.

Despite Almohad efforts to clean house at home, they could not dislodge the Christians from the heartland of Spain. Their high point came with a victory at Alarcos in 1195. Subsequent Almohad advances and pleas from the current king of Castile, Alfonso VIII, persuaded Pope Innocent III to proclaim an anti-Almohad crusade. A coalition of Christian soldiers assembled and marched out of Toledo in 1212, led by three kings: Alfonso VIII, Peter II of Aragon, and Sancho VII of Navarre. France and Portugal also sent troops, so in all there were five Christian nations participating. The Almohad leader, Caliph Muhammad al-Nasir, waited for them on the high plain of Las Navas de Tolosa; he figured they would have to pass through Losa canyon to reach him, and he would have no trouble defending that canyon.. It was the same strategy that the Spartans had tried at the battle of Thermopylae (see Chapter 2), and the result was the same; a local shepherd directed the Christians along a secret path that allowed them to bypass the canyon and surprise the Moslems on the plain. At this late date Moslem cavalry still did not wear the heavy armor that was in fashion among Christian knights, which meant they were faster when the battle started, so for a while it looked like the Almohads would win anyway. They almost did, but at the last moment Alfonso ordered his reserve cavalry to charge, and that shattered the Almohad army.

Las Navas de Tolosa marked the beginning of the end of Moslem Spain. Al-Nasir died a year after the battle (1213), and his successors negotiated a series of truces with the Christian kingdoms that temporarily stopped their advance, but the Moslems never had the initiative again. These truces held until 1225, when a civil war destroyed the unity that had made the Almohads so strong, and one of the factions invited Ferdinand III of Castile (1217-52, also called Ferdinand the Saint) to get involved. In 1230 the last king of León, Alfonso IX, died and left only daughters by his first wife, so Ferdinand III marched in and took over. He had a valid claim to the throne of León because he was the son of Alfonso IX by a Castilian princess, but the people of León revolted on and off for the rest of the thirteenth century, before they accepted the idea that they were part of Castile for good (Castile and León had separate crowns and governments until 1301).

Like the Almoravids before them, the Almohads treated Spain as part of a mainly African empire; those factions that could not fight in both Morocco and Spain decided that Morocco was more important, and concentrated their forces there. When the Almohads departed, Moslem strength in Spain withered away. Behind them Portugal, León and Aragon joined Castile in raiding al-Andalus, and the Christian attacks became a flood. Moorish cities and territories fell like dominoes: Mérida and Badajoz in 1230 (to León), the Balearic Islands between 1229 and 1235 (to Aragon), Beja in 1234 (to Portugal), Córdova in 1236 (to Castile, Ferdinand turned Cordova's great mosque into a church), Valencia in 1238 (to Aragon), Niebla-Huelva in 1238 (to León), Silves in 1242 (to Portugal), Murcia in 1243 (to Castile), Jaén in 1246 (to Castile), and Alicante in 1248 (to Castile). 1248 also saw the fall of Seville, Andalusia's greatest city and the Moslem capital since 1170 (to Castile).

Portugal's King Alfonso III (1248-79) gave Portugal its present-day frontiers by clearing the Moors out of Algarve, his southernmost province, and moved his capital from Coimbra to Lisbon. Navarre, however, dropped out of the Reconquista, because the daughter of Sancho VII married a French noble, the duke of Champagne, so after 1234 the Basques were more interested in what was happening north of the Pyrenees; we won't hear from them again until Chapter 10 of this work. As for the Moors, all that was left to them was a 200-mile-long strip of land in the southeast, now ruled by the Nasrid dynasty, descendants of an Arabian tribe called the Banu Nazari. This state, called the Emirate of Granada, lasted for nearly two and a half centuries; today it is best known for its glorious palace, the Alhambra.

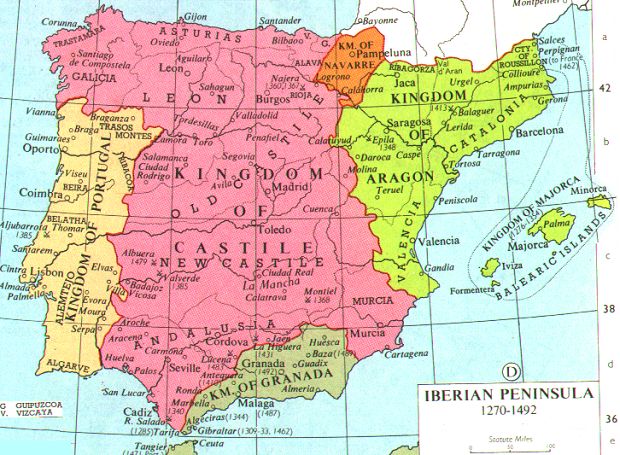

The Iberian peninsula, after the thirteenth-century Christian advance petered out. The frontiers between the five kingdoms were remarkably stable, lasting for two hundred years without a change.

Byzantium Under Siege Again