| The Xenophile Historian |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A General History of the Middle East

Chapter 8: ZOROASTRIANS, PAGANS, AND CHRISTIANS

226 to 570

(All dates are A.D. from now on.)

This chapter covers the following topics:

The Sassanian or Neo-Persian Empire

The defeat and death of Artabanus V did not eliminate opposition to Ardashir, who now held western Iran, Iraq and Kuwait. A powerful coalition formed to restore the Parthians, led by King Khosrau I of Armenia (Remember that the Armenian kings were also Parthian at this point). Khosrau opened the passes of the Caucasus to bring in barbarians from Russia, and got promises of aid from the Roman and Kushan empires. Rather than wait for all these enemies to come to his door, Ardashir acted first (227), with an extensive military campaign that conquered Seistan, Hyrcania, Afghanistan, and possibly Turkmenistan. The Kushan king sued for peace two years later, and Ardashir turned his attentions west, where the Roman occupation of northern Iraq gave him a ready-made grievance. In 230 he invaded Roman Mesopotamia, but here he faced the same tactical disabilities that the Parthians had during their last century (a vulnerable capital and a pro-Roman Armenia). The result was that the war went on for three years but Ardashir failed to win any new ground at all. Finally he went after Armenia, whose king put up a stubborn resistance until he was defeated in 237.

One reason for Ardashir's success was that he reorganized Persia, turning it into a tightly centralized state. Members of the royal family were made governors over most of the provinces, instead of local barons with dubious loyalties. Because of this Sassanian Persia became a more dangerous rival to Rome than the Parthians had ever been. The heavy cavalry, which had been an expensive afterthought to the Parthians, now became the main force in the Persian army. Armed with twelve-foot lances, these men and their horses wore chainmail, topped with a large cone-shaped helmet.(1) Most important was the reliability of the new army; the king could now recruit enough of them to defend the frontiers without worrying about them starting a civil war. The nobles also seem to have accepted their relative loss of freedom, since rebellion and assassination--now the order of the day in Rome--rarely happened in Persia.

To encourage popular support, Ardashir kept reminding the people of Persia's proud past. One result of this was the revival and reorganization of Zoroastrianism. The Parthians never had a state religion, tolerating every wind of doctrine that crossed the realm: Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Buddhism, Mithraism, Christianity, and even the pagan cults of prehistoric Iran. Ardashir used Zoroastrianism to forge an effective alliance between throne and altar almost a full century before Constantine tried the same thing with Christianity.

Zoroastrianism was unsuitable for export. Non-Persians found it unappealing, especially the practice of leaving human corpses to the vultures, to keep from polluting the three sacred elements (earth, fire, and water). However, its central doctrine, the unending conflict between good and evil, made it an appropriate creed for motivating warriors. Unfortunately it had split into some seventy sects over the ages, causing embarrassing differences from shrine to shrine; the Sassanid family, for example, worshiped two pre-Zoroastrian gods (Mithra the sun and the fertility goddess Anahita) alongside Ahura Mazda. Ardashir remedied this by ordering a standard version of the Zend Avesta, the Zoroastrian scriptures, and added suitable writings from Greek and Indian authors. Ardashir also proclaimed himself Ahura Mazda's chief representative on earth. Now when the Persian kings went to war, the Magi (clergy) followed, cleansing conquered territory of demons, dispensing justice and setting up a public administration. One of them, a priest named Tansar, eventually became Ardashir's most trusted advisor.

To enhance their mystique, Ardashir and his successors surrounded themselves with a great deal of ceremony. An elaborate crown and an imposing mace or scepter became the symbols of royal authority, which inscriptions showed as coming from Ahura Mazda himself. The Magi lit a holy fire in the Istakhr temple, and only extinguished it when the king died. They used astrologers and soothsayers to decide the best time for rekindling it, a requirement before coronations could take place; occasionally this delayed the crowning of a new king for years after he took power. The Seleucid calendar was replaced with a new one that counted years from when the first fire was lit; e.g., "five years from the sacred flame of Ardashir."

The royal obsession with strong government was also expressed in architecture. To get an awesome effect, Ardashir built his first palace on top of a breathtaking cliff. The entrance to the palace featured a startling innovation, an onion-shaped dome called an iwan. The dome has been a part of Middle Eastern architecture ever since, along with another contemporary invention, the barrel vault. Two miles south of the palace, Ardashir built a new capital named Firuzabad, with round walls to symbolize its location at the center of world power. However, it proved more practical to keep most of the administration and commerce where the Parthians already had it, in Ctesiphon. Seleucia also got a new lease on life, rebuilt under the name of Weh-Ardashir ("The Good Deed of Ardashir").

Two years before his death in 241, Ardashir gave the throne to his son Shapur I (239-272), possibly because of ill health. Shapur was an imperialist after his father's heart, enlarging the royal title to "King of Kings of Iran and Non-Iran," and to prove his point he immediately launched a two-front war against both Rome and Kushan. The eastern campaign was a complete success--Shapur destroyed the Kushan empire by 244--but his claim to have made the Oxus and Indus Rivers his frontiers seems to have been an exaggeration, reflecting influence, not authority (we know of Kushan city-states in the area as late as the fifth century). On the western front, Hatra, the city located where the Silk Road passed through Iraq, revolted in 238, and Shapur destroyed it so completely that it was never rebuilt (241). Shapur also claimed to rule the entire east coast of Arabia, from Kuwait to Oman, but we have no details on how he got that.

In the Roman empire, things went from bad to worse. The assassination of Severus Alexander in 235 eliminated the last bit of legitimacy the emperors had. During the next 50 years a bewildering series of "barracks emperors" rose and fell from power, nearly every one a usurper who assassinated the previous ruler. Meanwhile the economy deteriorated, plagues and urban decay depopulated the cities, and barbarians came across the frontiers with little opposition. Shapur thus had an excellent opportunity to make trouble, and he turned out to be the most dangerous enemy Rome had faced since Hannibal. He overran most of Syria and threatened Antioch before the current emperor arrived on the scene, the seventeen-year-old Gordian III. Gordian's lack of experience was more than made up for in a competent advisor, Gaius Furius Sabinus Aquila Timestheus, and together they drove Shapur out of the country (243). However, Timestheus fell ill and died not long after that, and Gordian was murdered, some say by his successor, Philip the Arab. Philip was in a hurry to get to Rome and stake his claim to the throne before somebody else did, so he arranged a hasty truce with Shapur. Philip reached Rome in time to celebrate the thousand-year anniversary of the city's founding, but otherwise he was as ephemeral as the emperors before and after him.

This is a good place to mention an immigrant from Central Asia whose tale is told in Edward Gibbon's work, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The story surrounding him is difficult to verify, but is so extraordinary that it deserves mention here. Gibbon called him a [sic] Scythian named "Mamgo," but he appears to have been Xiandi, the last Han emperor of China. Dethroned in 220, he wandered west with a few loyal retainers, until Ardashir gave him sanctuary in Persia. After Shapur became king, he received an unfriendly letter from China's new rulers, demanding the return of the fugitives. Instead Shapur persuaded Mamgo to retire to Armenia, and he told the Chinese ambassador: "I have expelled him from my dominions, I have banished him to the extremity of the earth, where the sun sets. I have dismissed him to certain death." Mamgo spent his last years as a faithful servant to the Armenian king.

Another confrontation with the Romans came in 256. Shapur moved west again, taking all of Roman Mesopotamia, Armenia, Cappadocia and Syria. The Roman emperor Valerian (the fourth since Philip the Arab), was sorely pressed by barbarians on other fronts, but he felt it necessary to defend his wealthy eastern provinces. He finally arrived on the scene and routed the Persians, but by the end of 259 Shapur was back. This time the Persians surrounded the plague-stricken Roman army at Edessa. Valerian tried to negotiate a peaceful solution, but he and his troops were taken prisoner and led off to Persia (One historian, Michael Grant, suggested that Valerian gave himself up to escape from his own mutinous soldiers!). Valerian remained a Persian captive for the rest of his life. I won't say that Shapur was cruel, but when Valerian died his skin was stuffed with straw and put on display in a Zoroastrian fire-temple. Valerian's capture was one of the worst moments in Roman history, and the Persians talked about it for many years afterwards.

Zenobia

All of Rome's eastern territory was now at the mercy of the Persians. They took Antioch, Tarsus, and even Caesarea in Cappadocia. The Roman general on the scene, Macrianus, inflicted a defeat that compelled Shapur to withdraw from Cilicia to the Euphrates; for a little while, anyway. In the midst of that reprieve Macrianus, who was too old to claim the throne himself, proclaimed his two sons Macrianus & Quietus joint emperors, and the Asian provinces joined their cause. Leaving Quietus behind to mind the shop in Syria, the two Macriani advanced into the Balkans, only to be killed in a battle there. In desperation Gallienus, the son and successor of Valerian, turned to Odenathus, a Romanized Arab who was the king of Palmyra, the main caravan stop in the Syrian desert. Odenathus turned out to be a very talented leader; he started by trapping Quietus in Emesa, where the would-be emperor was put to death by the townspeople.

Odenathus spent the next five years (262-267) campaigning against the Persians. The next time Shapur marched west, Odenathus defeated him so badly that he never came back. Then he recovered Armenia and Roman Mesopotamia; he tried twice to take Ctesiphon, but the Persian capital eluded him. Gallienus rewarded him with the titles of Imperator and Augustus, effectively making him emperor of the areas he now held. In 267 he and his eldest son were murdered, and the crown passed to his widow, Zenobia. Gallienus decided that it was time to put Palmyra back under Roman rule, but instead Zenobia declared her independence and took the offensive.

Odenathus had been a fine leader but his wife was even greater. Beautiful, intelligent and heroic, she quickly persuaded Asia Minor and Egypt to join her growing empire; Armenia and Arabia promised their support. Even the Persians, notorious male chauvinists then and now, were awed enough to offer aid. The new Roman emperor, Aurelian, was too busy on other fronts to deal with this challenge until 271, but when he arrived Zenobia met her match. Near Antioch his light cavalry defeated the Palmyrene archers and lancers, and then won a second victory at Emesa. When Palmyra itself came under siege (272), Zenobia escaped and fled to the Persians, but was captured on the banks of the Euphrates and brought back to Aurelian. Aurelian forgave her, but once he had returned to Europe the revolt started up again. This time he rushed east, captured and destroyed Palmyra, and took Zenobia with him to Rome. She was paraded, along with other defeated enemies, in a massive Roman triumph. After that she ended up in a villa at Tibur or Tivoli, she and her daughters married to Roman nobles. Such was the end of the heroine Gibbon hailed as the most remarkable woman in history.

Manicheism

Back in Iran, a priest named Kartir had succeeded Tansar as chief of the Magi. Despite Ardashir's sponsorship of Zoroastrianism, both he and Tansar had tolerated the kingdom's Jewish and Christian communities. Not so Kartir; he announced he would persecute as heretics all non-Zoroastrians who did not convert. Early in his reign, Shapur went along with Kartir's oppressive plan, until he realized that the growing power of the Magi was a greater threat to the king than the religious minorities could ever be. Shapur thereupon reversed his policy, declaring that, "All men of whatever religion should be left undisturbed and at peace in their belief in the several provinces of Persia."

Remarkably, Shapur's edict included a prophet whose teachings had the power to undermine the legitimacy of his rule. This was Mani (216?-276), a Persian who claimed he had God's final, universal revelation, one that would unite Christianity, Zoroastrianism, and all other creeds. Mani was brought up among Jewish Christians at Ctesiphon, but left them when he received his revelation. During the next thirty years he preached in Iraq, Persia, and India, allegedly delivering many from demons and diseases. Shapur even allowed him to speak at his court, though he did not convert.

Mani taught that there were two independent eternal principles, light and darkness, God and matter. Before the creation of the earth, light & darkness were separate; now they were intermingled; in the future they would be separated again. Jesus and all other religious leaders had been sent to release souls of light from the prison of their bodies. To Mani, all previous prophets--Moses, Buddha, Zoroaster and Jesus--had taught the truth, but their teachings had been corrupted in the centuries since. Therefore it was Mani's job to straighten out their now-confused messages. To guard against similar corruption of his own work, Mani personally wrote his message down and prohibited careless copying of his texts. This backfired; Manichean scripture always remained scarce, and what we have now is scraps and paraphrases, mostly from religious rivals. By prohibiting mistakes and vulgarizations, Mani effectively limited his followers to an elite of disciplined souls.

The Manichean community was divided between the white-robed priests, known as the elect, and the mass of laymen known as hearers. The hearers lived ordinary lives, and gave daily gifts of fruit, cucumbers and melons--which they believed contained great amounts of light--to the elect, who were ascetics and vegetarians. Only the elect could expect to go to heaven at the end of this life; the hearers would be reborn and given another chance to live a good life, coming back among the elect if they succeeded.

Despite Shapur's patronage, Mani was never popular among the Magi, who did not like being accused of corrupting the original teachings of Zoroaster. More to the point, Manicheism turned Zoroastrianism inside out; it argued that the king's support of righteousness was doing more harm than good, and redemption would only come when king and commoner alike accepted a harsh, celibate lifestyle that was the very antithesis of Persian luxury. After the death of Shapur, Kartir regained his influence. He had Mani imprisoned, and eventually executed. Throughout the reigns of the next four Persian kings, Kartir was the power behind the throne, and the power of the clergy grew to equal and even surpass the power of the nobility.

Manicheism took a lot longer to disappear. Its missionaries spread it to Africa, Europe, and even China. In 274 it was introduced to the Roman empire, and by the end of the century it had so many followers that the emperor Diocletian persecuted them, calling them Persian spies, even though they were also enemies of the Persian regime. St. Augustine was a Manichean at one point, but later refuted its teachings when he became a Christian. He and other Church leaders finally stemmed the tide, but the Manicheans continued to practice openly in the West until the sixth century. In 763 the Uygurs, a major tribe in Mongolia and northwestern China, converted, but eighty years later they proscribed it, calling it a religion for barbarians, and turned to the local form of Buddhism. There also was a Manichean revival in southern China during the 13th-14th centuries.

The heretical groups that existed in Medieval Europe and Asia Minor may have gotten some of their beliefs from the Manicheans. The Paulician movement in the Byzantine Empire rejected Manicheism, but resembled it in its views on the struggle between light and darkness. The Paulicians in turn inspired the Manichean-like Albigensian heresy in southern France during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, provoking a crusade against them by Pope Innocent III. In the 14th century the last heirs of Manicheism were suppressed by the Ming emperors in China and the Inquisition in Europe.

The Growth of the Church

Despite persecution by Jews, intellectuals, and the Roman state, Christianity grew steadily. In the first century the Christians had gained new followers by preaching openly, but that method was now very hazardous, and we seldom hear of it in the second & third centuries. In its place the early Christians used semi-private instruction, setting up classrooms to teach those who wished to become Christians, and baptizing them all at one time, usually on Easter. Personal witnessing to friends was also popular, and probably used on most occasions. Finally they resorted to a tactic long used by the Greeks--philosophic argument. This came about because of the strange rumors that went around concerning the church. Non-Christians often accused Christians of the following:

1. Antisocial behavior, because they held their worship services in secret places like underground cemeteries (catacombs), did not observe pagan Roman holidays, and denounced the gladiatorial shows.

2. Cannibalism, because the Christians referred to their holy communion as "the body and blood of Christ."

3. Atheism, because the Christians, like the Jews, worshipped no images.

4. Incest, because they openly spoke of their "love" for one another.

5. Disloyalty to the state. The Christians did not worship the emperor, and they declared Jesus would overthrow the government of the world when He returned, which was expected to happen soon. This charge caused the most trouble, because it brought the wrath of the emperors upon them.

A series of Christian writers, known to us as the Apologists, refuted these false charges, and by showing that Christianity was superior to Judaism and paganism, they hoped to win the legalization of their faith. Justin Martyr's First Apology, which he wrote directly to the emperor Antoninus Pius, is an excellent example of this literature. Later writers, such as Irenaeus, Tertullian, Cyprian and Origen, had similar ideas in mind, but they also refuted heresies such as Gnosticism which by then had crept into the movement.

The personal behavior of Christians often gained them converts. When a plague broke out in Alexandria, nearly everybody fled the city, but the Christians stayed behind to care for the sick and bury the dead. In a society where charity was rare, this made quite an impact. The personal bravery of Christians was also noticed. Even their enemies, like the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, admitted that Christian courage in the face of death was praiseworthy. The sufferings of martyrs sometimes encouraged bystanders to declare themselves Christians, even though it meant almost certain death for them too.

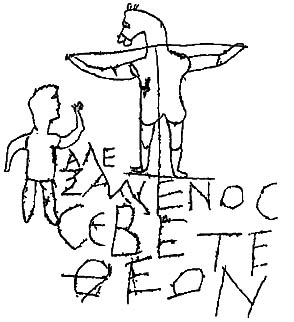

Archeologists sometimes find silent testimony to personal faithfulness. A crude piece of anti-Christian graffiti dating from the third century was found on a Roman wall, depicting a boy raising one hand reverently to a crucified figure with the head of a donkey. Beneath it are mocking words: "Alexamenos worships his god."

As church membership grew, it became necessary to set up an organization above the individual congregations, to prevent disunity over matters of doctrine. Sometimes several churches would get together and pick one of their members to be a bishop over them all. Or a church might establish a new congregation in a nearby town, and put its original leader in charge of both the old and the new church. Organization tended to follow the Roman pattern, with all the churches in a province uniting under one bishop, so that in time the Church became an empire within the empire. Usually bishops traced their authority directly to the Apostles; for example, Irenaeus, the Bishop of Lyons in the late second century, claimed to be a convert of Polycarp, who in turn was converted by the Apostle John. By 250 the Church organization was nearly complete, with four bishops (those of Rome, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem) regarded as patriarchs or leaders over the others. When Byzantium (re-named Constantinople) became the new Imperial capital early in the fourth century, its bishop was elevated to patriarchal status as well.

As the Church's membership turned predominantly Gentile, it departed from its original Jewish heritage. In its place pagan ideas crept in. Many early Christians turned to the works of Greek philosophers, using pagan intellectual exercises to strengthen their arguments. This got so popular by 200 that an exasperated Tertullian asked, "What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?" Other pagan elements may have been introduced to make conversions easier, though this may have been unintentional. The current emphasis on the Virgin Mary in the Catholic & Orthodox churches appears to be a carryover from the mother goddess that exists in almost every form of paganism (Mesopotamia's Ishtar, the Egyptian Isis, the Greek Aphrodite, etc.). Likewise, Christian holidays were placed so that they could be celebrated on or near the same days as the Roman ones. For example, the actual birthday of Jesus was unknown, so they observed it on the same day as the Mithraist birthday of the sun (December 25), just four days after the Roman Saturnalia. In the second century there was a controversy over whether Easter should be held at the same time as the Jewish Passover; those who thought so were labeled Quartodecimans, meaning "fourteenthers" (Passover falls on the fourteenth day of the Jewish month Nisan).

At the same time, Christians felt the need for a dependable record of Jesus' life on earth. Besides the books of the New Testament we are familiar with, there were a number of other gospels, epistles, and "acts" floating around. Many of these were written to satisfy curiosity about things not covered in detail by the first-century authors, like the childhood of Jesus or the life of Pontius Pilate. Others were no more than imaginative romances and novels. Many of the latter popularized the ideas of fringe groups, like the Docetists, who rejected both sex and marriage. It took a long time to decide which books were authentic scripture. The Epistles of Paul were the easiest to agree on; all churches were using them by 100. The three synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) and Acts came next, entering the New Testament before 150. John's Gospel took until 200 to win acceptance because it was a favorite among Gnostics and Montanists (more about them later). The last nine books had the same problem, especially Hebrews and Revelation. The Eastern church finally produced the New Testament in its present-day form in 367; the Western church followed suit at the Council of Carthage in 397.

Competitors to Christianity

While the Church was developing within the Roman Empire, the Romans were losing faith in the gods of their ancestors. The myths surrounding Jupiter, Mars, Minerva, etc. were now viewed as rather silly stories about oversized people acting like oversized people (remember the Greek attitude in Chapter 6). In addition, the Roman religion had long ago passed from simple ceremonies to elaborate public rituals that had little meaning for the layperson. The old gods were kept around because they symbolized the state, but as far back as the days of the Republic, Romans had begun looking for a kind of spiritual sustenance which their gods could not supply. Some turned to Greek philosophy, especially Epicureanism, Stoicism, and Neo-Platonism. Others were attracted to the emotional experiences that Middle Eastern deities offered. From this perspective one could say that the Romans viewed Christianity as the latest Eastern cult to come their way, sort of like the way we view the Hare Krishnas and the Moonies.

The cult of Asia Minor's fertility goddess, Cybele ("Diana of the Ephesians" in the Book of Acts), was first brought to Rome during the Second Punic War. The Romans let her stay because some thought she had driven away Hannibal, but many had misgivings about her. Cybele's worshipers took part in orgies where dancers went crazy and cut themselves with swords and knives; soon participation in them was forbidden to Roman citizens.

Cybele/Diana's Temple at Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world (see also Chapter 6).

Later on, the laws were relaxed and Cybele gained a new following, but she was never as popular as her Egyptian counterpart, Isis, a more gracious and gentle deity. Romans, especially Roman women, were drawn to the 10-day initiation ceremonies of Isis, where the main event was a play that acted out the story of the death & rebirth of her husband, Osiris. This miraculous resurrection, supposedly achieved by the grief and faithfulness of Isis herself, was what made her cult appealing; her followers believed that their participation in the rites gained them immortality as well.

The Eastern religion that had the highest moral tone was a Persian import, Mithraism. The origins of Mithra (also called Mithras) go back to the Indo-European nomads of the second millennium B.C. Parthian kings liked Mithraism because it was part-Greek in origin (remember, they were pro-Greek in the second and first centuries B.C.), but as we noted earlier, they did not have a state religion. By the time the Romans met Mithra he had acquired Zoroastrian overtones and was portrayed with a halo of sunbeams, like the Greek Helios. Like Ahura Mazda, Mithra was a champion of truth and light, whose followers joined him in fighting the powers of evil. It was a man's religion, with rigorous tests of initiation and a secret organization like modern Freemasonry. Its emphasis on fraternity and combat caused it to spread like wildfire when the Roman soldiers discovered it; by the third century it was the army's unofficial religion. In a superficial way it resembled Christianity; for example, there was a ceremony similar to baptism, which used bull's blood instead of water. Nevertheless, its overwhelming masculinity discouraged women from joining, whereas women played an important part in the growth of the Church. Its mystery nature also became a limiting factor; the Mithraists were so successful at keeping their doctrines secret from outsiders that no Mithraist literature exists today.

The city of Dura-Europus, on the Syrian bank of the Euphrates, provides us with a view of how diverse religious life could be in the third century. On the frontier between East and West, it changed hands several times and acquired a mixed population of Greeks, Romans, Persians and Semites. Within its walls archaeologists have found five Greek temples, a temple to Bel (a latter-day version of the Babylonian Marduk), a house that doubled as a Christian chapel, a synagogue, a Mithraeum, and several shrines to pagan deities that were composites of Greco-Roman and Near Eastern gods. There was no fire-temple, but that might have been because Shapur I destroyed the city in 256, just a generation after Zoroastrianism had been restored in its Persian homeland.(2)

The First Heresies

Besides the challenge from without, Christianity faced serious challenges from within. In Paul's first letter to the Corinthians, he criticized that church for splitting into factions centered on the personalities of human leaders, including himself. Later on disagreements on matters of doctrine and practices arose, despite attempts to maintain spiritual and physical unity. One early split, the one that created the Ebionites, was discussed in the previous chapter. Another doctrinal split created Docetism, which taught that Jesus was a pure spirit-being who only appeared to be a man, uncontaminated by this imperfect world. There were many Docetists in Asia Minor near the end of the first century, prompting John to attack their views in his first and second epistles. Ignatius did the same a few years later, writing that: "Jesus Christ was of the race of David, the child of Mary, who was truly born and ate and drank, was truly persecuted under Pontius Pilate, was truly crucified and died." In the 180s, the Church father Irenaeus listed twenty Christian sects that existed in his day. Two hundred years later, a bishop named Epiphanius estimated there were eighty sects.

A second-century challenge came from Marcion, a wealthy ship-owner, who came to Rome and began teaching a deliberately anti-Jewish brand of Christianity. Around 172 a young Christian named Montanus proclaimed himself a prophet. His followers combined prophetic enthusiasm with strict asceticism and fanaticism ("Do not hope to die in bed . . . but as martyrs.").

Similar attitudes were expressed in the third century when the question arose concerning what to do about Christians who renounced Jesus under threat of persecution. The hard-liners, led by a puritanical Italian clergyman named Novatian, formed their own congregation in 251. They soon built up a network of Novatianist churches throughout the empire, calling themselves Cathari (pure ones) to distinguish themselves from the mainstream churches, which they considered polluted because of their lenient attitude towards sinners. Christians who became Novatianists had to be re-baptized, as if they were joining the only true church. Novatianists also refused to associate with people who had been married more than once, and rejected the possibility of doing penance for any major sin after baptism.

Novatianists were treated as heretics for a while in the fourth and fifth centuries, but they were really just fanatics, and by 600 they were reabsorbed into the mainstream churches. Novatianist clergymen were allowed to retain their rank when they rejoined the moderate majority.

The most dangerous fringe groups were a variety of religious movements that we collectively call Gnosticism. Christian writers of the second century, especially Irenaeus, denounced Gnosticism as a perversion of Christianity. Gnostic beliefs varied considerably, but all relied on a Manichean-style dualism: Gnostics viewed the world as evil, created by an evil or ignorant God who was not the God of the New Testament. Sparks of divinity, however, have been encased in the bodies of men, and when provided with secret knowledge (gnosis), they can be awakened and released to reunite with God.

The other Gnostic beliefs were even more bizarre. Most of them opposed sex and marriage; the creation of woman was evil because it allowed procreation, and every time a child was born one more soul fell into bondage under the powers of darkness. Some encouraged sinful behavior, claiming that the "knowledge" made them "pearls" that could not be stained by any mud from the world. Still others maintained that Jesus was a spirit, not a real man (the Docetic view). The Cainites perversely honored Cain and the other villains of the Old Testament, while the Ophites venerated the serpent for bringing "knowledge" to Adam and Eve. Menander, who lived in Antioch late in the first century, claimed that whoever believed in him would not die; needless to say, his own death proved that he was a false prophet. His Ephesian contemporary, Cerinthus, taught that Jesus escaped from the cross and the Romans crucified Peter by mistake, thinking it was Him.(3) Irenaeus humorously tells us that the Apostle John fled from a bath-house when he learned that Cerinthus was also there!

Remarkably, there is a surviving community of Gnostics today, the Mandaeans in Iraq and Iran. They use three major texts: the Ginza, a detailed description of the Creation; the Johannesbuch, some late traditions about John the Baptist; and the Qolasta, a collection of prayers and liturgies. Most of these manuscripts were written between the 16th and 19th centuries, though individual excerpts may be older.

The Roman Response to Christianity

Like most pagans, the Romans were generally tolerant of other peoples' gods; after all, they might be Roman ones under different names! (e.g., Jupiter=Zeus=Ammon=Baal=Marduk) The only cults that were put on restriction were Judaism, Christianity, and the nature worship of the Druids. Druidism was off-limits because it practiced human sacrifice, and preferred Roman human sacrifice! Judaism and Christianity were seen as having an attitude problem: the Jews because they revolted constantly (until 135 A.D., anyway), the Christians because they denounced all other gods as demons from Hell.

At first the Romans had trouble telling the difference between Christians and Jews; in the first century they called Christians "Nazarenes" or "Jews who followed Chrestus" (Christ). As the practices of Christianity diverged from Judaism, this problem disappeared, but the Romans still did not know what to do with the unarmed revolutionaries that made up the Church; they certainly did not seem to deserve the special exemptions given to the Jews. Around 112, a perplexed Pliny the Younger, then governor of Bithynia and Pontus, wrote to Emperor Trajan about the Christians living in his area, who now made up a large part of the population. Full of misgivings about the government's standing order to execute them, Pliny wrote that instead of killing accused Christians outright, he put them to a simple test: if they offered incense to a statue of the emperor and cursed Christ, they were allowed to go, because it was said that nothing could persuade genuine Christians to perform such acts. Trajan approved and added the following: "These people are not to be sought out. If they should be denounced and convicted, they must be punished, but with this proviso: anyone who denies he is a Christian . . .shall . . .obtain pardon through his recantation. Information published anonymously should never be admitted in evidence. That constitutes a very bad precedent and is not in keeping with the spirit of our times."(4)

The persecution of Christians before 250 was ugly enough but fortunately local in nature; while the authorities in one province threw them to the lions, others would leave them alone. The number of Christians grew steadily, until even the imperial household had some; Severus Alexander is said to have kept a statue of Jesus in his private chapel, along with those of several emperors, Abraham, Orpheus, Apollonius of Tyana, Alexander the Great, and other great historical figures.

None of the emperors before 300 liked Christians much; even emperors that we call "good," like the previously mentioned Trajan and Marcus Aurelius, felt that persecuting the Church was one of their duties. The result was that the Church grew the most under the worst emperors. Commodus, for instance, is credited with starting the Roman Empire's long decline, and he was so busy pumping up his own ego that he never got around to torturing or killing any Christians. Likewise, Elagabalus was the priest of another eastern religion, so he may have seen Christianity as a potential ally against traditional Roman beliefs.

It was Decius (249-251) who first ordered an anti-Christian pogrom all across the empire. He commanded all citizens to sacrifice to the official gods of the Roman state; those who did so received certificates proving that they obeyed the order. Many Christians actually complied to save their lives, while others escaped by bribing officials into giving them certificates without performing the sacrifices. Those who were unable (or unwilling) to obtain certificates were imprisoned and executed, including the bishops of Rome, Antioch and Jerusalem. Fortunately Decius was not emperor for long, and after him the persecutions were only halfhearted efforts. Then in the 260s, Emperor Gallienus issued a decree calling for the toleration of all religions. We saw that the Empire was fighting for its life during his reign, and Gallienus needed all the prayers he could get. Consequently the Christians were left in peace for forty years.

The persecutions did not cripple the Church; they strengthened it. Members who were not willing to support God's work all the way were weeded out in the process; those who were martyred were seen as receiving a special reward in heaven. Tertullian dramatically stated that: "We multiply every time we are mowed down by you; the blood of Christians is seed." A fifth-century writer, Prudentius, transformed the stories of the early martyrs into a new body of Roman legend. However, he was occasionally carried away by his fervor: a tortured Christian utters six tirades against the heathens after his tongue has been cut out; and St. Lawrence, who was roasted on a grill, is made to say, "Turn me over; I'm done on this side."

The persecutions were the last gasp of pagan Rome; the final one, carried out by Diocletian, will be described shortly. By the beginning of the fourth century Christianity had won the empire; the last step in the process was the winning of the emperor.

The Roman Empire Transformed

Very little is known about the short reigns of the two sons of Shapur I, Hormizd I and Bahram (Varahran) I. Bahram's son and heir, Bahram II (276-293), had to fight a two-front war: the latest Roman invasion coupled with a rebellion in eastern Iran from his brother Hormizd, the viceroy of Seistan. The Roman trouble started when yet another soldier-emperor, Carus (282-283), took over. Once domestic affairs had been taken care of, he marched east, declaring that he had come to the throne to punish the Persians. He left his elder son Carinus behind to rule in his absence; the younger son, Numerian, came with him. Thanks to the Persian king's problems, Carus found the going easier than it should have been; he reoccupied Roman Mesopotamia without opposition, then captured Seleucia and finally Ctesiphon. Yet just a few nights later, Carus was found dead in his tent. There had been a violent thunderstorm, and some thought that he had been killed by lightning. Others suspected, however, that his death was the work of one Arius Aper, Numerian's father-in-law, who saw a greater future for himself once the young man's father was out of the way. The throne now passed under the joint rule of Carinus in the West and Numerian in the East.

Since the Seistan rebellion was a more serious threat to his crown, Bahram immediately made peace with the Romans so he could be free to deal with his brother. Armenia and northern Iraq returned to Roman rule, and Numerian began the long trek home. By the time he got to Bithynia, he was suffering from lack of sleep and a disease of the eyes, and was being carried in a litter. At Nicomedia on the Bosporus, the army stopped to rest; there Numerian was murdered by Aper. For the next few days the soldiers asked about the emperor's health, and Aper told them that Numerian could not leave his tent because he had to protect his weakened eyes from the wind and the sun. Before long, however, the stench of the corpse revealed what had happened. Aper tried to pass Numerian's death off as being from natural causes, so he could claim the throne for himself. The troops, however, were not of the same mind; one of their number, a general named Diocles, ordered Aper killed and was hailed as emperor under the name of Diocletian. Marching into Europe, he removed Carinus from office and took the whole empire for himself.

Bahram III reigned for a few months in 293 and was overthrown by the last son of Shapur I, Narses (293-302). He promptly went for a rematch against the Romans and took Armenia. Diocletian's "Caesar" or vice-emperor in the East, Galerius, came to the rescue with a small army, fought a see-saw struggle where both sides won battles, and finally won a crushing victory in 296, annihilating a much bigger army along the banks of the Tigris. The entire family and harem of Narses, along with much booty, fell into Roman hands. To get his family and concubines back, Narses signed a treaty that gave Rome all of the disputed territory plus five provinces on the east bank of the Tigris. This was Rome's greatest triumph against the Persians. After this the Romans were content with their success and Persia was relatively weak, so the treaty lasted for 40 years.

The rise of Diocletian brought an end to the civil war period in Roman history. He overhauled the entire government to make revolts more difficult, if not impossible, in the future. The most memorable of his successors, Constantine (306-337), finished the reorganization that Diocletian started. Together they saved the Roman Empire, but the Empire they left to their successors was very different from the one of Caesar Augustus: it was a divine-right monarchy in name as well as fact; it no longer had the city of Rome for its capital; it was Christian; it was divided more often than united; it was a little smaller and a lot poorer.

The ideas concerning divine-right monarchy came from the Persians, giving proof to the maxim that if you fight the same enemy long enough, you will come to resemble him. Diocletian lived in Oriental splendor, surrounded himself with eunuchs, wore a crown and robes of purple and gold silk, carried a scepter, and placed red silk slippers adorned with precious stones on his feet. Borrowing another Sassanid custom, he demanded that all people admitted into his presence--including his own family--prostrate themselves and kiss the hem of his robe.

Diocletian observed the pagan cult of ancient Rome, and strongly favored conformity, so he came to see the Christians as a dangerous subversive movement. There were Christians in the imperial bureaucracy and even in Diocletian's own family. One day in 298, the imperial fortunetellers looked for omens from the gods, and when they tried to read the liver of a sacrificed animal, they could not agree on what they saw. They blamed some Christians in the room, who had been frantically crossing themselves to drive away the demons. At first, Diocletian reacted mildly, but five years later, egged on by his heir Galerius, the last and most terrible attempt to eradicate the Church began. The first of his four anti-Christian edicts ordered the destruction of all churches and their holy books. Diocletian showed he meant business on the very day this edict went into effect, by having a church within sight of his palace in Nicomedia burned down. The second edict commanded Christian clergymen to sacrifice to pagan gods on pain of death; the third edict extended this order to all Christians. The fourth edict gave additional powers towards the carrying out of the other three. Thousands accused of being Christians were executed without regard for rank; among those killed were two high court officials, Gorgonius and Dorotheus, and even Diocletian's chamberlain, Peter. When the inhabitants of a small town in Phrygia declared their loyalty to Christianity, soldiers herded them into their church and set it on fire.

Diocletian retired in 305. Under Galerius, the persecutions turned even more vicious. Thousands were thrown into dungeons and executed without trials or regard for rank.(5) Six frightful years later, Galerius realized that Christianity was too widespread to stamp out and his policies were alienating even non-Christian Romans. On his deathbed, he voided Diocletian's edicts, and pleaded with Christians to pray for his salvation. In the following year (312), Constantine legalized Christianity, either from a personal conviction or from a desire to gain the upper hand against his pagan rivals. Constantine waited until the last days of his life to receive baptism, but from here on the Church had the advantage; by the end of the 4th century it was the only legal religion in the empire.

The Christianization of Rome encouraged Christians in the Middle East to favor Roman policies. Armenia had already proclaimed itself the world's first Christian nation in 303; now this strategically important land was bound even closer to Rome. In response the Persian kings felt a need to strengthen Zoroastrianism. All heresy was proscribed by the state, defection from Zoroastrianism was made a capital crime, and persecution of all other faiths, especially Christianity, began. The rivalry between East and West now took on a religious dimension.

Shapur the Great

Hormizd II (302-309), the son and successor of Narses, married a Kushan princess to maintain peace on his eastern frontier. His son Shapur II had one of the longest reigns in history (309-379), because, according to Gibbon, he was a king all of his life; his coronation took place before he was even born! In one of his most delightful anecdotes, Gibbon describes how this happened: Hormizd was childless when he died, but the queen was pregnant. The Magi did not want a violent struggle for the throne, so they said they knew for a fact that the queen was going to have a boy, and went ahead with the coronation before anyone could stop them! The ceremony was performed in the throne room with the queen on a bed, and the imperial crown was placed on her stomach.(6)

Because of the strength of Constantine's rule and Shapur's relative youth, the peace between Rome and Persia lasted while Constantine lived. By the time Shapur was old enough to rule on his own, the state had virtually become a Zoroastrian theocracy. The most fanatical of all Persian kings, Shapur found it only natural to double the taxes of Christians to support his endless wars. When they protested, he mercilessly persecuted all non-Zoroastrians within the realm.

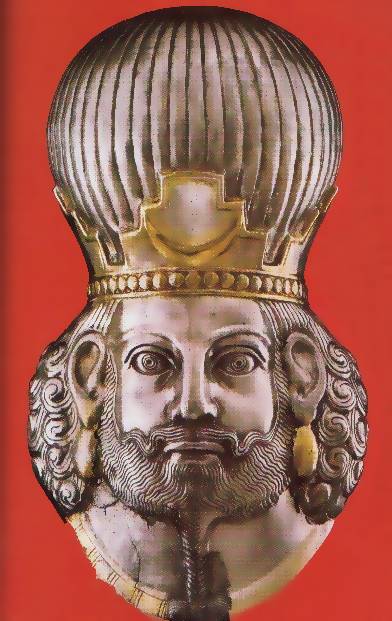

Shapur II.

Indeed, Shapur proved to be a ruthless adversary to any who opposed him. His first military campaigns were punitive expeditions directed against the Arabs and the Kushans, both of which had raided Persian territory during the long minority of the king. He won the submission of the Arabs by filling their wells with sand. After putting down a revolt at Susa, he used elephants to pulverize the ruins of that timeworn city beneath their giant feet. When he learned of the death of Constantine, his agents kidnapped and blinded the pro-Roman king of Armenia.

As might be expected, the meddling in Armenian politics provoked a new war with Rome. Shapur won nine battles in the Tigris valley, and the Roman emperor, Constantius II, turned out to be a timid commander, but the biggest prize, the city of Nisibis, remained in Roman hands. Shapur besieged it three times in a twelve-year period, and his failure to take it prevented him from following up on his victories. At this point a new enemy, the Huns, appeared on Persia's eastern frontier. Shapur was forced to put the war on hold, and he spent the next five years in a long campaign against the Huns (353-358). Returning to Mesopotamia in 359, he inflicted a sound defeat on the Romans, taking the citadels of Amida and Singara.

Both sides now took a break for a few years, during which Constantius was succeeded by his nephew Julian (also known as Julian the Apostate, for his attempts to bring back paganism). Julian renewed the war in July of 362, leading an army from Europe to Antioch. In March of 363 he marched eastward with 65,000 troops; another 30,000 soldiers marched to Armenia, where they were expected to pick up native reinforcements. Shapur was surprised by the size of the Roman army, and except for a few guerilla raids, he tried to stay out of the way. Outside the gates of Ctesiphon he assembled his own army, which included war elephants. Julian arrived in June, was disappointed to find that his Armenian allies were nowhere to be found, but charged the Persians anyway, and won a stunning victory; one eyewitness claimed the Persians suffered 2,500 casualities, while the Romans only lost seventy men. However, it would take a siege to capture the Persian capital, and when an even larger Persian army showed up, Julian briefly considered marching on into Iran, and then gave the order to retreat by way of Assyria. On the way back, the Persians practiced a scorched-earth policy, causing the Romans to run low on supplies, and they suffered from the heat and the flies. Ten days later the Persians attacked, and Julian led a charge without putting on his armor. He was mortally wounded by a Persian lance, and an uncharismatic officer, Jovian, was proclaimed emperor on the spot. In order to save his men from their now desperate plight, he signed a disgraceful treaty with the Persians. All of the Tigris valley, including Nisibis, which the Romans had defended so well, was handed over; in addition Armenia and recently Christianized Georgia had their status changed from Roman satellites to Persian ones. Shapur was probably relieved to end the war as well, for now it was essential to have peace on the frontier; barbarian tribes (the Goths and other Germans in Europe, the Huns in both Europe and Central Asia) were now becoming a major threat to both empires.

Rome and Persia managed to keep the terms of the treaty for over half a century, though they found it difficult to resist interfering in Armenia. A few years after the war Roman intrigues compelled Shapur to place Armenia under military occupation. His successors tried to solve the problem by partitioning the kingdom: one fifth of Armenia became a Roman province, while they renamed the rest "Persarmenia" (387). In 428 Persarmenia and the Arsacid dynasty were abolished completely, and Persian governors directly ruled the area afterwards.

The Empire of Caesar & Christ

When Diocletian divided the Roman empire into eastern and western halves, nobody saw it as a permanent division creating two states. Indeed, during the fourth century a strong emperor (Constantine, Constantius II, Julian, and Theodosius I) could rule the entire realm. Consequently, when Theodosius divided the empire between his two sons (395), it was seen as another temporary split. This time, however, it became permanent; the fifth-century emperors were puppets of their courts, each unable to rule more than his half of the realm (and usually less than that in the West). For the eastern empire, the division was a new lease on life, allowing it to keep its wealth at home to enlarge the armed forces or to buy off the increasingly rapacious barbarians. For much the same reason, the division insured that the less populated, poorer west would not recover from the calamities that came its way. The "fall of Rome" took place before the fifth century ended, but the eastern half, governed from Constantinople (formerly Byzantium), lasted nearly a thousand years longer, until 1453. To reflect the changed situation in Europe we shall refer to the Roman state as the "Eastern Roman Empire."

Intrigue, murder, and treachery became the order of the day among the ruling class in both east and west. Stilicho and Aetius, two generals who ably defended the West against the Visigoths and Huns respectively, were killed by their distrustful emperors. The infighting got so bad that the eastern emperor Arcadius chose Persia's King Yazdagird I to be the guardian of his son and heir, seven-year-old Theodosius II (408-450). This story is bizarre, in view of the long-standing feud between Romans and Persians (Gibbon had trouble believing it himself), but not impossible. It may have come about because Zoroastrianism rates truth as the most important virtue; at any rate it implies that the emperor's archenemy was more trustworthy than his "friends."

Now that the Church had conquered Caesar, it spent its energies in disputes over the nature of God. The first controversy, whether or not the Trinity existed, was largely settled by 400, but by that time a new storm broke over the relationship between the human and divine components of Jesus. Did Jesus have only one personality that was divine from birth (the Monophysite view)? Did he have two personalities in one body (the Nestorian view)? Or were his two natures at once separate but intermingled? The moderate view was the one the state adopted; at the councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451), Nestorianism and Monophysitism were respectively condemned as heresies.

The doctrines behind these controversies are too subtle for many people to understand today, but worth noting because of what formed around them. Before the concept of political parties was invented, a dissident religion was used by people to express political opposition. In a time when the natural order seemed to call for one government ruling most of the known world, a modern-style nationalist movement with a slogan like "Freedom for Armenia" would have been unthinkable. However, they could indirectly challenge the central power by adopting the local heresy, giving it patriotic overtones. For that reason Nestorianism survived in Syria and Monophysitism gained a passionate following in Egypt, Syria and Armenia. Likewise the emperors felt inclined to reach some compromise with the heretics, since they revealed a discontent with the state that was otherwise inexpressible. The African Donatists, however, were not subtle enough; when they opposed the appointment of a new bishop at Carthage, they crossed the indefinite line between Church and State and brought down on their heads the full weight of the government.

Though Byzantium and Persia were both quick to act against deviations from the state creed, they were more than willing to welcome each other's heresies. For that reason Manicheism was temporarily accepted in the West, enjoying good times until it challenged the Christian majority and turned popular opinion against it. Nestorianism flourished in the Persian empire because its followers were obviously not Roman agents; by 486 all Persian churches were officially Nestorian. When this happened Sassanid persecution of Christians all but stopped. Nestorian missionaries did not convert many Persians, but they enjoyed limited success in India, Central Asia, Mongolia and China. The far-reaching spread of the Nestorians enabled them to survive after they lost their Middle Eastern home to Islam.

Because Constantinople was the focal point of theological controversies, even the ordinary person in the capital became his own theologian. In 381 St. Gregory of Nyssa wrote in amusement and despair: "Every place in the city is full of theologians--the back alleys and public squares, the streets, the highways--clothes dealers, money changers, and grocers are all theologians. . .If you inquire about the value of your money, some philosopher explains wherein the Son differs from the Father. If you ask the price of bread, your answer is the Father is greater than the Son. If you should want to know whether the bath is ready, you get the pronouncement that the Son was created out of nothing!"

Persia Besieged

After three relatively weak reigns (Ardashir II, Shapur III, Bahram IV), Yazdagird I (399-420) became king of Persia. The persecution of Christians declined during this period, due to the peaceful situation on the western frontier and the personalities of the reigning kings. Yazdagird was the most tolerant yet, perhaps because he had a Jewish wife. He convened a council, allowed the installation of bishops over the Persian churches, and permitted the free movement of clergy throughout the country. But the Christians abused their new privileges, and staged violent anti-Zoroastrian demonstrations. Late in his reign, pressure from the nobility compelled Yazdagird to reverse his policy.

After his death, the nobles refused to let any of Yazdagird's sons succeed him. But one of them, Bahram, had the support of al-Mundhir, the pro-Persian prince of the Arab Lakhmid kingdom, as well as help from Mihr-Narseh, Yazdagird's last prime minister, and that gained him the throne. As King Bahram V (420-438), nicknamed Gur (Wild Ass), he became the most popular of all Sassanid rulers, winning renown as a hunter, poet, lover and musician. He was a favorite subject in Persian art and literature for centuries, even after the fall of the empire. Early in his reign the persecution of Christians angered the Romans and brought on a short war (421-422), which ended with a few minor Roman victories in Mesopotamia. In the treaty that followed the West agreed to tolerate Zoroastrianism and the East Christianity. The religious reason for waging war was about to disappear anyhow, since the recently excommunicated Nestorians were quite willing to form an Iranian Christian Church with no political ties to the West. In Central Asia Bahram was more successful, driving off the latest incursion of Huns.

Yazdagird II (438-457) started out by persecuting Jews and Christians, until another speedy Roman victory (441) reminded him of his treaty obligations. His worst problem came from the east, where the White Huns swept away the last of the Kushans (440-460). During their two centuries of decline, the Kushans had become thoroughly Persianized; with their elimination Persia lost a shield rather than an enemy. The Asiatic newcomers proved to be extremely aggressive, and Yazdagird spent most of his reign keeping them out of his eastern provinces.

Nowadays the origin and ancestry of the White Huns, also called Ephthalites, is something of a mystery; none of their civilized neighbors knew who they were or where they came from. They were probably descendants of the Xiongnu, the fearsome barbarian tribe that lived in Mongolia and harassed the Chinese until they built the Great Wall. Procopius, the sixth-century Roman historian, described them as having Caucasian features--white skins and big eyes--hence the term "White Huns." Attila's Huns, on the other hand, had typical Oriental features. They very well could have come from a single multi-racial tribe, though. Early Chinese annals described some of the Xiongnu as having "red hair, green eyes, and white faces."

Like the other tribes that came out of Eurasia's heartland, the White Huns were nomads who lived on horseback, herded animals, and moved frequently in search of fresh pastures or wild game. They slept in round tents called yurts and wore felt or skin trousers, leather boots, leather or fur upper garments, and fur caps. The men shaved their heads except for two braided pigtails behind their ears and a single tuft on top, and many of them wore long wooden earrings.

Unusual in any society, the White Huns practiced polyandry, though how many husbands a woman could have is not clear. Powerful wizards, shamans, and witch doctors guided the tribe's animist (nature-worshipping) rites. Many of their customs, such as drinking the blood of a sacrificed white horse to seal a contract, disgusted civilized peoples, and the rest of their behavior was just plain severe. To enforce their simple laws, they crushed the ankles of minor offenders and executed those guilty of major offenses. Widows slashed their cheeks when mourning the deaths of their husbands, so that blood flowed with their tears. Boys learned to fight on horseback at an early age and became warriors as soon as they could pull a full-sized bow. Enemies had a special fear of White Hun arrows, which were barbed so that when they were removed, they did as much damage coming out as they did going in.

Persia came to the brink of disaster under Peroz (457-484), whose reign was contemporary with the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Several years of famine ruined the economy, forcing the king to refund taxes and distribute grain to his hungry subjects. Religious strife remained a problem; the king continued to persecute Jews and non-Nestorian Christians. Worst of all, the White Huns broke through the Persian defenses again and again. Killing and looting wherever they went, they continued into northern India, where they destroyed one of the most culturally brilliant nations India ever produced, the Gupta Empire.

When he first tried to solve the Ephthalite problem, Peroz was defeated, captured, and forced to pay a heavy ransom to regain his freedom. He left his son Kavadh as a hostage while he gathered the funds by raising taxes, and appealed to the Romans for assistance. The Eastern Roman emperor, Zeno, paid the ransom, because a weakened Persia was useful as a buffer between Byzantium and the barbarians (encounters with Attila proved that Huns of any color were bad neighbors to have around!). Of course an ungrateful Persian king might raid the Roman portion of Iraq, but as long as Persia and the White Huns were relatively equal in strength, and fighting each other, the risk to Roman Mesopotamia was within acceptable limits. In pursuit of this policy, the Romans later encouraged the Huns to penetrate the Caucasus and attack from the north, to keep the Persians from recovering too quickly.

Several years of peace allowed Peroz to restore his financial position and raise a new army to avenge himself on the White Huns. His advisors tried to talk him out of it, but the king was adamant. When the rematch came, the White Huns won by trickery; they dug a great pit or trench, lined it with sharpened stakes, and lured the Persians until they fell into it. Peroz paid for his ill-fated enterprise with his life, and the Sassanids became tribute-paying vassals of the White Huns. A few years later the brother of Peroz, Valash (484-488), tried to drive out the nomads, only to be deposed and blinded. The crown went to Kavadh, who was viewed as a safe puppet because of the time he had spent in the White Hun camp.

Kavadh I inherited a country ravaged by war and famine; his vassals were in revolt and the nomads roamed through his lands at will. The need for gold was greater than ever, but the treasury was now empty. The people started listening to a radical priest named Mazdak, who preached an early form of "liberation theology." His creed combined a Manichean view of the universe with communist political practices; he demanded that the nobility give up their lands, possessions, and even their harems to the peasants. In better days, Mazdakism would have gotten little attention, but now it gained large numbers of followers, including, incredibly, the king. To help the movement, Kavadh introduced new laws, many improving the status of women. For this behavior, he was deposed in 496 by coalition of nobles and Magi. He fled to the White Huns, and they restored him to the throne in 499. Kavadh learned his lesson about starting class struggles: he had Mazdak murdered and purged the revolutionary's followers.

On the western frontier, a new war (502-506) began when the Eastern Roman emperor Anastasius I refused Kavadh's request for money to pay the White Huns' tribute. Kavadh invaded Roman Armenia and captured the main city there, Theodosiopolis (modern Erzerum); a second campaign destroyed Amida in Iraq. The Romans turned him back at Edessa, and a fresh incursion from the White Huns forced him to make peace, restoring the pre-war boundary between the empires. Late in his reign, however, Kavadh saw an opportunity to renew the struggle (524), sending raiders into Roman territory. Byzantium did not respond until 527, when Justinian I inherited the throne. In that year he directed his best general, Belisarius, to teach the Persians a lesson. Belisarius won a brilliant victory at Dara in 530, defeating a combined Persian-Arab army of 40,000 men by using his infantry defensively and his cavalry offensively. In the following year, however, Belisarius was defeated by a superior army at Callinicum and compelled to retire to the Euphrates, where he stood firm against further Persian attacks. He did not have to do so for long, though; in 531 Kavadh died and his son Khosrau I (also called Chosroes or Khusraw) concluded an "eternal peace" with Justinian.

Khosrau I

Khosrau I (531-579) was the greatest of all Sassanid monarchs. He started his reign by restoring property seized during the Mazdakite excesses, and carried out the reforms Kavadh planned but never had time to implement. He streamlined the government and reorganized the army. Most important was a fairer tax code, which appraised land according to its yield, situation, and type of crops grown on it. The system worked so well that it was continued by the Arab administration after the fall of the empire. He also revived the mystical majesty of his office, filling his court with luxuries that Ardashir could hardly have dreamed of. At Dastagird, seventy miles north of Ctesiphon, he built a new palace with the largest iwans ever constructed, filled it with treasures like the famous "Winter Carpet," which was designed to make him forget it was winter with its luxury and scenes of flowers and fruit, and made a golden crown that was so heavy that it had to be suspended on chains from the ceiling, to keep it from breaking the royal neck.

Khosrau's reputation as an enlightened and just ruler was great, and known in foreign lands. When Justinian closed down the philosophy school in Athens, the last Neoplatonists immigrated to Persia. They hoped to find in Khosrau a true philosopher-king, a political ideal which Confucius and Plato had unsuccessfully searched for in their day. Unfortunately the philosophers found orthodox Zoroastrianism even less to their taste than orthodox Christianity, and they decided to go back to Greece. Khosrau took pity on them by inserting a clause into a later peace treaty with Justinian, giving them the right to return and ensuring that they would not be molested for their paganism or their temporary pro-Persian behavior.

The "eternal peace" promised in the first treaty between Khosrau and Justinian only lasted for seven years, until 539. Khosrau's forces seized and sacked Antioch, won battles in Roman Mesopotamia, and advanced all the way to the Black Sea. But in Justinian the Eastern Roman Empire had a leader of equal caliber. Since most of his armed forces were busy elsewhere, Justinian chose to fight a defensive war in the Middle East, but Khosrau was never able to hold onto any Roman territory for long. Over twenty years of on-and-off fighting followed, until a fifty-year peace accord was signed in 561. In the end the only Persian conquest was one of the Georgian states, Iberia (really an annexation, it had been a Persian satellite since 364); the other Georgian state, Lazica, remained in the Roman orbit.

On other fronts Khosrau did better. Early in his reign he stopped paying tribute to the White Huns, who had recently grown too weak to enforce their will on Iran. Around 553 another warlike barbarian people, the Turks, appeared in Central Asia. Khosrau married their chief's daughter and persuaded them to join him in an attack on the White Huns. The Turks were more than happy to destroy the nomads living in the lands they wanted for themselves. Once their old enemies were gone the Persians advanced their frontier to the Oxus, loudly proclaiming the victory as their own. In 575 a naval expedition across the Arabian Sea conquered Yemen, making Persia the most influential power in Arabia.

Classical Arabia

We know very little about Arabiaís history before the seventh century A.D..† Part of the reason is because there has not been much archaeological investigation, and though we can read the numerous stone inscriptions left behind by the ancient Arabs, they help us little when no event mentioned by them can be found in the literature of other civilizations. Also, the modern Arab attitude can be a hindrance; most of them care little about their pre-Islamic history, calling it al-Jahiliyah, the age of ignorance.† We havenít discussed the Arabs since Chapter 2, but because we know so little about how they got started, it wonít take long to catch up on their early history.

Around 750 B.C. Ma'in gained a rival to the south named Saba, or the Sabaean kingdom. Saba quickly became rich and powerful because of its irrigation system; the water was collected by a quarter-mile-long dam at Marib, whose magnificent ruins are still standing. Both Ma'in and Saba built their capitals some distance from the farmlands, suggesting that trade was a more important source of wealth than agriculture.† By 400 B.C. two more states had appeared on the shore of the Gulf of Aden, named Qataban and Hadramaut; the latter also tried to rule the Dhofar district in Oman.† Since Saba was the strongest of the four, Ma'in and Qataban formed an alliance to keep Saba from overwhelming the others.

In the northwest, a tribe called the Anbat, or Nabataeans, formed a kingdom in Jordan and the Sinai peninsula.† They prospered because of a good location on the trade routes and by use of water & conservation techniques whose efficiency has only recently been appreciated. Cisterns, dams, aqueducts, and water channels were all used; they terraced hills to prevent soil erosion. Modern Israelis have applied similar techniques for living in the Negev.† The Nabataean capital, Petra, had superb natural defenses; it was in a valley with an entrance so narrow that four men standing abreast in it could hold off an invading army.† Petra is first mentioned at the end of the fourth century B.C., when Antigonus I, one of Alexander the Great's generals, made an unsuccessful attempt to conquer it. The kings of Petra carved fine tombs and other buildings out of the pink sandstone that lined the valley walls; later Bedouins believed that djinni built them.

The collapse of the Seleucid kingdom gave the Nabataeans complete control of the caravan stations as far north as Damascus.† The Nabataean kingdom peaked under its greatest king, Aretas IV (9 B.C.‑40 A.D.), and came to an end when the Roman emperor Trajan conquered it in 106 A.D., turning it into a Roman province named Arabia Petraea.

In the east, Ubar underwent major construction around 350 B.C.† This marked the beginning of at least six centuries of prosperity for the people of ĎAd, thanks to their incense and isolation. Shortly after 1 A.D., Hadramaut built a fort named Sumhuram, near the best natural port in Dhofar.† This meant ĎAd could no longer trade by sea, but this didnít really hurt them; in fact, it made Ubar more important for overland commerce than before.† Soon the ĎAd made an alliance with the Hadrami king, ĎIlíad. They probably did this protect themselves from a Roman naval invasion.† It was an early instance of the kind of love-hate relationships that still mark the Middle East: "Brother against brother, brothers against cousins, brothers and cousins against the world."

In the south, Saba absorbed Ma'in around 250 B.C.† In 115 B.C. a new state named Himyar arose right on the Arabian peninsula's corner, at the Bab-el-Mandeb.† Himyar grew to unite all of south Arabia under its rule, annexing Saba (ca. 25 B.C.), Qataban (ca. 50 A.D.), and Hadramaut (ca. 100 A.D.).† After that the Himyarites expanded their influence to central Arabia, and remained Arabia's dominant state until the sixth century A.D.

Frankincense remained the main commodity of the Arabian trade network.† The aromatic leaves of the myrrh plant found similar uses; the Egyptians, for example, stuffed mummies with them.† Most Arab traders started from Yemen, went up the west Arabian coast along a road that paralleled the Red Sea, and entered the Roman Empire at Petra or Damascus. To keep this trade flowing, the Romans ruled their Arabian province leniently. Traders also went to and from Yemen by sea, connecting it with India and East Africa. Some have even suggested that the Wise Men of the New Testament might have been Arabs rather than Persians or some other sort of Orientals, because the gifts they brought (gold, frankincense, and myrrh) could all be found in Arabia.† The trade became so lucrative that the Romans called Yemen Arabia Felix, or Happy Arabia.† In 24 B.C. Aelius Gallus, the Roman prefect of Egypt, sent an expedition to conquer Yemen; it failed, due to the rigors of the Arabian climate.

Along the Hejaz caravan route, two oases, Mecca and Yathrib (later called Medina), grew into cities. They also became an entry point for elements of Western civilization.† One such contribution was monotheism; Jews and Christians both converted many Arabs, and Judaism became dominant in Yathrib by the time of Mohammed. Mecca was blessed with two major spirit-possessed objects:† a meteorite (the famous Black Stone) and a spring (the Well of Zamzam). At some early date a cube-shaped temple called the Kaaba was built next to the spring, as a repository for the Black Stone. 360 idols were put outside the Kaaba, one for each day of the year.† Many of these idols were plain stones, called betyls, and pilgrims practiced an unusual form of idol exchange, often leaving one of their own betyls behind so they could take a Meccan stone home with them. Soon pagans from all over Arabia were making pilgrimages to Mecca, giving the city a thriving tourist industry.(7)

The tribes of Arabia were eventually drawn into the east-west struggle between the Romans and the Persians. Even Himyar and Ubar chose to pay tribute, though they were far away and had plenty of desert between them and the empires.(8) Then came an economic slump, caused by a totally unexpected foreign development:† the rise of Christianity.† This new religion taught that belief in God and a righteous lifestyle, not big offerings, brought salvation.† Moreover, Christians favored simple burials over cremation and mummification.† When Christianity became the official religion in Rome, the demand for frankincense and myrrh dropped dramatically; what little that was sold now went into rituals and cosmetics only. The kingdoms of Arabia, which Pliny had once described as "the richest nations in the world," collapsed into insignificance, starting with Himyar.

In the fourth century A.D., the two big empires started subsidizing the tribes on their desert frontiers, paying them to keep the other nomads away.† The Persian satellite, a tribe called the Banu Laikhm (the Lakhmids), came to rule a long, narrow realm, stretching along the west bank of the Euphrates and the Persian Gulf, running all the way from the modern Syrian-Iraqi border to a point past the Qatar peninsula.† We credit them with turning a cursive form of the Aramaic script into Kufic, the classical Arabic alphabet.† Their pro-Roman counterparts, the Banu Ghassan (Ghassanids), ruled the Jordanian and Syrian deserts after 500.† The two tribes were constantly at war, waging one feud after another.† Both eventually converted to Christianity, but that did not end the nastiness, because they chose opposing sects; the Ghassanids were Monophysites, while the Lakhmids became Nestorians.† A third state, Kindah, became a neutral power in central Arabia around 460, lasting until the Lakhmids overthrew it in 528.

Arabia in 530 A.D. From Spiegel Online.

The civilized empires, despite their differences, agreed that the Bedouins made unruly allies. Early in the seventh century, the Eastern Roman emperor Heraclius cut the Ghassanids' subsidy, and relations were never the same again (he may have been mad at the Ghassanids' adoption of a creed Constantinople regarded as heresy).† Persia tried to end the Lakhmids' independent behavior by annexing their territory.† The result was a major invasion by other Bedouins in 604; the Persians had to relinquish the land they grabbed to defend their homeland.

According to Arab legend, Ubar fell because it grew both wicked and rich, like Atlantis and Sodom. Four years of searing drought came after the collapse of the incense trade, but Shaddad, the king of the ĎAd, was vain and arrogant, believing himself to be a god. The Ubarites agreed, proclaiming, "Who is mightier than we?"(9)† The only dissenting voice came from Hud, a merchant of Jewish descent.

The stage was now set for one of ancient literatureís classic duels of morality: spirituality vs. materialism, God vs. gods, virtue vs. appalling customs like female infanticide.† Arab stories claim that Hud was a champion of monotheism, a forerunner to Mohammed. Whether or not this was true, Shaddad ignored the warning, and instead sent a delegation of seventy men to Mecca, as if a big offering to the Meccan idols would bring back prosperity. No such luck; when they returned Ubar was suddenly destroyed.† The legends arenít clear on what happened, except that it was a divine judgment; they make it sound like a firestorm overthrew the city. The archaeologists who rediscovered Ubar in 1992 found that half of it fell into a sinkhole, sometime between 300 and 500 A.D.††An earthquake apparently caused this, and if it happened at night, that would explain how the cataclysm killed most of the inhabitants.† The ruined city was never rebuilt, and was soon forgotten. The Mahra and Hadrami tribes fought over the site in the centuries that followed--not for the incense, but because it was a convenient stop on the way across the Rub al-Khali. By 1200 the caravan route was also abandoned.† When a Hadrami warlord, Badr ibn Tuwariq, built a new citadel on top of Ubarís old fort in the early sixteenth century, he got credit for building the whole thing from scratch.

At the end of the pre-Islamic era, south Arabia was a mixture of people from many religions: pagans, Jews, Christians of many sects, and Manicheans. From the end of the fourth century onward, the Himyarite kings were Jewish; it looks like they converted to Judaism to avoid becoming a satellite state of the Romans. One of these kings, Dhu Nuwas, was so concerned with the growing power of Christianity, that he allied himself with Persia, early in the sixth century.† Then he began to persecute the local Christians, attacking towns like Zafar and Najran, where the population was largely Christian. The Arab Christians appealed to the Christian king of Axum (Ethiopia) for protection, and he obliged by invading and conquering Himyar in 525. Dhu Nuwas, according to the chronicles, mounted his charger, "plunged into the waves of the sea, and was never seen again."